Abstract

Objective

To systematically review the most recent scientific literature regarding modern strategies for organ preservation in the treatment of non-metastatic muscle-invasive bladder cancer.

Methods

Literature search was made using PubMed, Google Scholar, EMBASE, Wiley Library, and ClinicalTrials.gov following the recommendations of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses statement. The primary outcome was 5-year overall survival rate, which was addressed by a systematic review and meta-analysis. The risk of bias and quality of evidence were assessed according to the Cochrane Collaboration and the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation system.

Results

The evidence is consistent in showing that 5-year survival of trimodality therapy is similar to radical cystectomy in selected patients, ranging between 29% and 73%. Patients undergoing bladder-sparing therapy were found to have better outcomes in terms of quality of life and sociability than those undergoing radical cystectomy. Immunotherapy is establishing itself as a strategy for organ-preservation treatment, showing complete response rates between 42% and 100%. However, most of these results have been obtained from ongoing clinical trials. Furthermore, there are still no studies comparing the efficacy among the different available therapies.

Conclusion

Although radical cystectomy remains the gold standard treatment for muscle-invasive bladder cancer, its significant morbidity has prompted the exploration of alternative therapies. In this context, bladder preservation therapies, though supported by limited literature, emerge as a potential alternative that could offer comparable oncological outcomes in selected patients.

Keywords: Muscle-invasive bladder cancer, Trimodality therapy, Immunotherapy, Bladder-sparing

1. Introduction

Bladder cancer (BC) is the 7th most commonly diagnosed cancer in males, whilst it drops to the 10th position when both genders are considered [1]. In non-metastatic BC, approximately 75% of patients present with disease confined to the mucosa (pTa, carcinoma in situ [CIS]) or submucosa (pT1), but most of the cancer-specific mortality is associated with pT2–T4 tumors [2]. The current treatment of clinically non-metastatic muscle-invasive BC (MIBC) is associated with significant morbidity and mortality [3,4]. Since it generally affects elderly people with more comorbidities, postoperative complications are more likely to occur [5]. MIBC only reaches a 50% 5-year survival rate [5,6], despite aggressive treatment with radical cystectomy (RC) and pelvic lymph node dissection, currently being the gold-standard approach [[5], [6], [7], [8], [9], [10], [11]].

RC is related to infectious, genitourinary, gastrointestinal, and wound-related complications, occurring in up to 58% and perisurgical mortality up to 4.7% (at 90 days) of patients with MIBC [3]. Additionally, sexual function and social and/or economic aspects have a significant impact on quality of life (QoL) [12,13]. All of these complications reflect the need for bladder-sparing options for non-metastatic MIBC [3]. Several bladder-sparing therapies have been described, including chemotherapy (CMT), radiotherapy (RT), and trimodality therapy (TMT) [14]. RT alone has been shown to have worse outcomes when compared to chemoradiotherapy and TMT [14,15]. On the other hand, CMT has shown a limited role as a single or dual therapy compared to TMT [16]. While all monotherapies are less effective than RC and are not recommended as curative therapy [[14], [15], [16]], TMT has shown favorable results. In fact, TMT, which consists of maximal transurethral resection of bladder tumor (TURBT) followed by RT with concurrent radiosensitizing CMT, is currently the most common bladder preservation strategy [5].

Immunotherapy (IMT) agents such as immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) have provided new perspectives in the treatment of MIBC during the last years [17]. Among them, inhibitors of programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1), programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1), and cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 (CTLA-4) are currently available therapies with different results and indications [17].

Among the limitations of bladder-sparing strategies, the evidence is still limited and heterogeneous in the population and inclusion criteria. Additionally, cohorts are small and do not have long-term follow-up, and there are no prospective randomized studies comparing outcomes between RC and TMT. Reviews and meta-analyses published to date provide discordant results that preclude drawing concrete conclusions about therapies [[18], [19], [20]]. In addition, IMT is a developing alternative for which few published results exist and have not yet been included in reviews as a therapy alone [21]. The aim of this study was to systematically analyze the most recent scientific literature regarding organ preservation strategies in the treatment of non-metastatic MIBC, comparing oncologic and functional outcomes, and QoL between RC and TMT, in addition to results of novel IMT agents for BC. Additionally, a meta-analysis was performed to compare the 5-year overall survival (OS) outcomes between both treatments across multiple studies, enhancing the quality of the conclusions.

2. Acquisition of evidence and analyses

The literature search was conducted using PubMed (access date: August 27, 2023), Google Scholar (access date: September 3, 2023), EMBASE (access date: September 11, 2023), Wiley Library (access date: September 11, 2023), and ClinicalTrials.gov (access date: October 19, 2023). The reporting of this systematic review was guided by the standards of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement [22]. The protocol was registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO), in accordance with PRISMA guidelines (PROSPERO registration ID 574880). The search was performed by two independent reviewers using the keywords: “Radical cystectomy”, “Bladder-sparing”, “Bladder cancer”, “Bladder preservation”, “Muscle-invasive bladder cancer” or “MIBC”, “Trimodal therapy”, “Immunotherapy”, and “Chemoradiation”. We included original articles, retrospective studies, prospective studies, systematic reviews, meta-analyses, congress abstracts (meeting-driven poster or oral communication), and clinical trials between January 2012 and December 2024 involving RC, TMT, and IMT. Only articles in English were included; however, the search was not limited by language. We excluded letters, editorials, case reports, prevalence studies, study protocols, narrative reviews or qualitative studies, pre-clinical studies (non-human animal models or in vitro studies), and non-peer-reviewed articles except clinical guidelines. In addition, we excluded articles that were duplicated on different platforms or with full texts that were unable to be accessed. Finally, publications that showed unsuitable participant criteria (patients without diagnosis of MIBC or CIS, and without chemoradiotherapy, RC, TMT, or IMT [alone or concurrent]), unsuitable technical or clinical outcomes (no report of prognosis, progression, or survival), and unsuitable outcome-report format (no OS or survival curves, disease-specific survival, disease-free survival [DFS], salvage cystectomy [SC] reported at 3 years, 5 years, 10 years, or 15 years) were excluded.

After a first phase of evidence screening based on the evaluation of titles and abstracts, 107 articles were selected for independent evaluation of their full texts by the reviewers. When there were disagreements on inclusion, these were resolved by a third reviewer. According to the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 21 articles were included. The results and syntheses of each study are described in Table 1, Table 2, Table 3, Table 4 and in the main text (narrative). This systematic review process is described in the PRISMA flow chart (Fig. 1).

Table 1.

The summary of results obtained for RC (n=41 776).

| Study | Patient, na | OS (%) | DSS (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cahn et al., 2017 [40] | 22 680 |

|

|

| Kulkarni et al., 2017 [41] | 56 |

|

|

| Ritch et al., 2018 [42] | 6606 |

|

|

| Vlaming et al., 2020 [29] | 431 |

|

|

| Grossmann et al., 2022 [43] | 572 |

|

|

| Pfail et al., 2020 [44] | 8288 |

|

|

| Softness et al., 2022 [33] | 1812 |

|

|

| Qiu et al., 2022 [45] | 891 |

|

|

| Zlotta et al., 2023 [34] | 440 |

|

|

OS, overall survival; DSS, disease-specific survival; yr, year; MIBC, muscle-invasive bladder cancer; primMIBC, primary MIBC; secMIBC, progressive MIBC; NAC, neoadjuvant chemotherapy; RC, radical cystectomy; AC, adjuvant chemotherapy; NA, not available.

The number of patients who underwent RC and not the full cohort.

Table 2.

The summary of results obtained for trimodality therapy (n=5582).

| Study | Pathological tumor stage | Patient, na | OS (%) | DSS (%) | SC (%b) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Efstathiou et al., 2012 [46] | T2–T4 | 348 |

|

|

|

| Zapatero et al., 2012 [47] | T2–T4 | 72 |

|

|

|

| Cahn et al., 2017 [40] | T2–T3 | 1489 |

|

|

|

| Giacalone et al., 2017 [32] | T2–T4 | 475 |

|

|

|

| Kulkarni et al., 2017 [41] | T2–T4 | 56 |

|

|

|

| Ritch et al., 2018 [42] | T2–T4 | 1733 |

|

|

|

| Softness et al., 2022 [33] | T2–T3 | 236 |

|

|

|

| Qiu et al., 2022 [45] | T2–T4 | 891 |

|

|

|

| Zlotta et al., 2023 [34] | T2–T4 | 282 |

|

|

|

OS, overall survival; DSS, disease-specific survival; SC, salvage cystectomy; yr, year; NA, not available.

The number of patients who underwent trimodality therapy and not the full cohort.

The percentage of patients who required SC at 5 years or 10 years despite treatment with TMT.

Table 3.

Summary of results obtained for non-clinical-trial publications on immunotherapy (n=123).

| Study | Pathological tumor stage | Patient, na | Drug | OS (%) | DFS (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hu et al., 2022 [52] | T2–T4 | 33 |

|

|

|

| Xu et al., 2023 [17] | T2–T3 | 25 |

|

|

|

| Dahl et al., 2024 [53] | T2–T4 | 65 |

|

|

|

OS, overall survival; DFS, disease-free survival; yr, year; PD-1, programmed cell death protein 1; HER2, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2; NA, not available.

The number of patients who underwent immunotherapy and not the full cohort.

Results for tislelizumab and toripalimab, respectively.

Table 4.

Summary of results obtained for clinical trials on immunotherapy (n=166).

| Study | Pathological tumor stage | Patient, na | Drug | CR (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vaishampayan et al., 2020 [59] | T2–T4 | 17 |

|

42 |

| Balar et al., 2021 [55] | T2–T4 | 54 |

|

83–100 |

| Garcia del Muro et al., 2021 [58] | T2–T4 | 32 |

|

81 |

| Weickhardt et al., 2022 [56] | T2–T4 | 27 |

|

88 |

| Vazquez-Estevez et al., 2022 [57] | T2–T4 | 14 |

|

100 |

| Niu et al., 2022 [60] | T2–T4 | 22 |

|

59 |

PD-1, programmed cell death protein 1; PD-L1, programmed death ligand 1; CR, complete response; CTLA-4, cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated antigen 4.

a The number of patients who underwent immunotherapy and not the full cohort.

Figure 1.

The flowchart on the stages of inclusion of studies in our systematic review according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines.

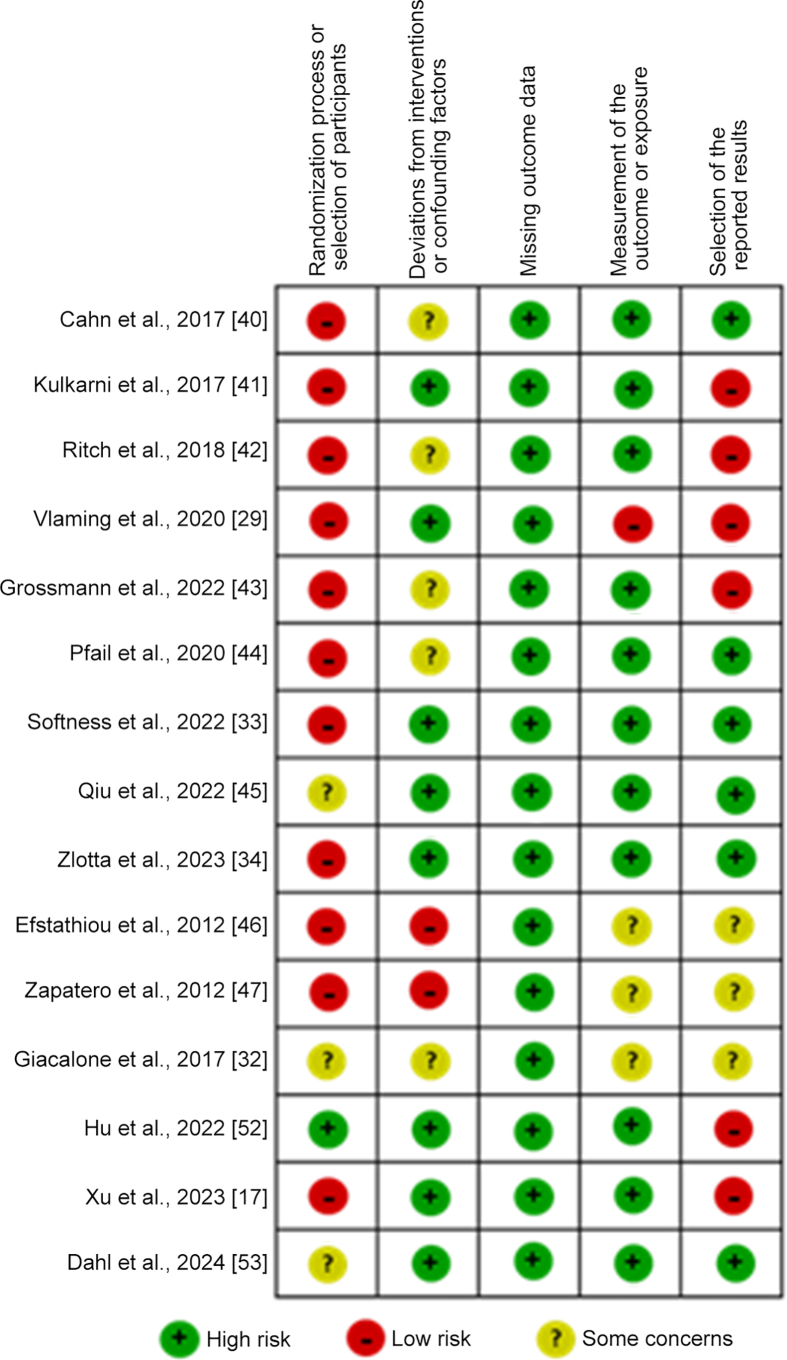

For the bias risk evaluation of the studies, the Risk of Bias 2 and the Risk Of Bias in Non-randomized Studies-of Exposure (ROBINS-E) tools for randomized and non-randomized studies according to Cochrane Collaboration were used to assess the bias risk classification of the studies [[23], [24], [25]]. The evaluation criteria domains included randomization process or selection of participants, deviations from intended interventions or confounding factors, missing outcome data, measurement of the outcome or exposure, and selection of the reported results. The studies were classified as “high-bias risk”, “low-bias risk”, and “unclear-bias risk”, or “some bias risk concerns” based on the above criteria.

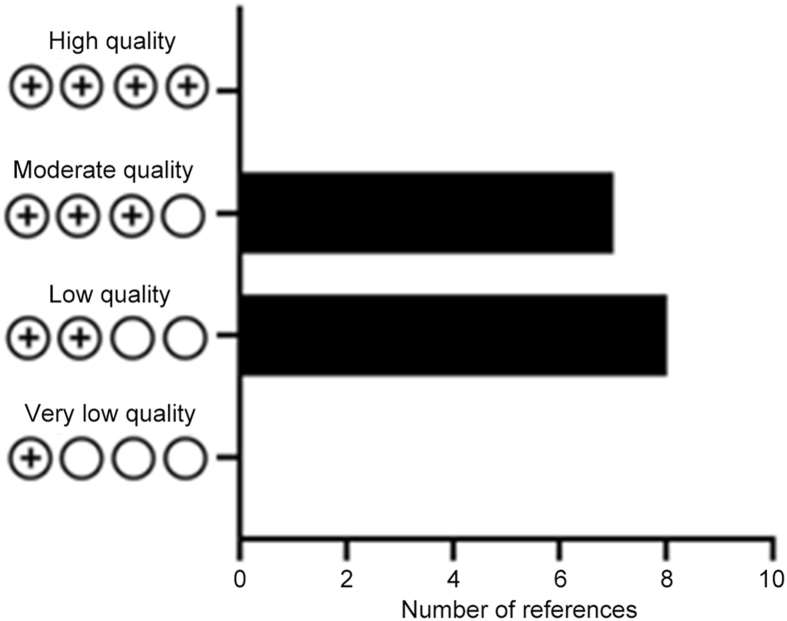

For quality evaluation of the studies included, the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) standard in the Cochrane Collaboration was used for quality classification [26]. The evaluation criteria domains included risk of bias, imprecision, inconsistency, indirectness, and publication bias, in addition to effect, dose response, and residual confounding. A study with a score of “4 plus” was considered high quality, “3 plus” moderate quality, “2 plus” low quality, and “1 plus” very low quality based on the above criteria. It should be noted that since completed randomized clinical trials on this topic are scarce, none of the studies achieved the maximum score of 4 plus.

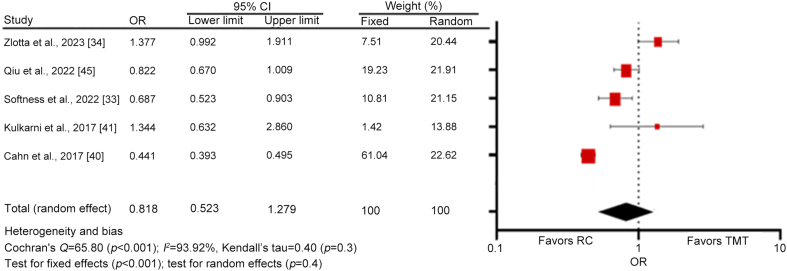

For the evaluation and comparison of the target clinical outcome, a meta-analysis including only studies that compared TMT and RC was performed. GraphPad Prism v10.2.3 (GraphPad Software, Boston, MA, USA) and MedCalc Statistical Software version 19.2.6 (MedCalc Software bv, Ostend, Belgium) were adopted for the figure drawing and statistical analysis, respectively. Proportions, odds ratios, and 95% confidence intervals were used to evaluate and compare the survival rates or OS outcomes at 5 years between TMT (intervention) and RC (control). A random-effects model was used for the meta-analysis [27].

3. Synthesis of evidence

After the search, evidence was collected from 21 articles that included a total of 47 647 patients. Summarized information for each of them can be found in Table 1, Table 2, Table 3, Table 4. Once the selection and analysis of articles were done, the risk of bias and quality assessment were performed using the Risk of Bias 2 tool, ROBINS-E tool, and GRADE classification for 15 of the 21 articles as shown in Fig. 2, Fig. 3, and Supplementary Figure 1. The remaining six articles were excluded from the analysis since they were partial result reports from clinical trials, but were discussed in the review. Overall, the risk of bias analysis showed higher risk for the “randomization process or selection of patients” and “selection of reported results” domains, but lower risk for the “missing outcome data” and “measurement of the outcome or exposure” domains (Fig. 2). Regarding the quality analysis, 53% of the articles were classified as “low quality” and 47% as “moderate quality” (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Figure 1).

Figure 2.

Risk of bias assessment of included articles.

Figure 3.

The bar chart for results based on the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation quality.

3.1. TMT

Currently, the gold standard for treating MIBC is RC with bilateral pelvic lymphadenectomy and urinary diversion. This involves removal of the bladder and its surrounding tissues, with an extended surgical time and hospital stay length, and patients requiring 3 months to 6 months to recover to baseline levels [5,16]. Nowadays, cisplatin-based neoadjuvant CMT (NAC) is a therapeutic strategy used prior to primary cystectomy in MIBC with methotrexate, vinblastine, doxorubicin and cisplatin (MVAC), gemcitabine and cisplatin, and dose-dense MVAC [28]. The reason for NAC is to treat micrometastatic disease at the time of diagnosis, when the burden of disease is the lowest [28]. Adjuvant therapy, according to American and European guidelines, lacks quality evidence to support its impact on survival to date [6].

Despite being the main treatment, RC only provides about a 49% 5-year survival [29] (Table 1). Regarding QoL after RC assessed by SF-36 and QLC-C30 questionnaires, most of the patients showed poor urinary and sexual function along with impaired body image and emotional status [30]. Furthermore, even patients suitable for RC often choose to postpone this option [5]. Currently, TMT is the most established bladder preservation strategy in non-metastatic MIBC [16]. TMT protocols vary among clinical trials and regions, but they broadly consist of maximal TURBT followed by RT with concurrent radiosensitizing CMT [16]. In case of muscle-invasive residual disease at restaging, SC should be performed [5,15,31]. Patient suitability for TMT is crucial for successful oncological management. The main selection criteria are unifocal tumors <6 cm suitable for complete macroscopic resection, cT2–cT3a tumors, absence of extensive CIS, no bilateral hydronephrosis, and good bladder function [5]. The most relevant results of TMT to date are summarized in Table 2.

Giacalone et al. [32] retrospectively analyzed 475 patients undergoing TMT. OS rates at 5 years, 10 years, and 15 years were 57%, 39%, and 25%, respectively, being better for cT2 (65%, 46%, and 29%, respectively) than for cT3 (42%, 26%, and 17%, respectively). SC requirement rates at 5 years and 10 years were 29% and 31%, respectively. Six deaths occurred due to treatment and one patient required cystectomy for treatment-related toxicity [32]. Softness et al. [33] included 2048 patients with cT2–cT3 cN0 cM0 MIBC in their retrospective analysis, where 1812 were treated with RC and 236 with TMT. In their study, 5-year OS rates for RC and TMT were 53% and 44%, while 10-year OS rates were 40% and 33%, respectively. However, patients treated with RC were significantly younger (64 years vs. 70 years, p<0.01) and had a lower Charlson comorbidity index than patients treated with TMT. Furthermore, RC patients were more likely to be treated in academic centers. Interestingly, when sensitivity analyses were applied to reduce confounding factors by restricting the cohort to patients between 40 years and 70 years and Charlson comorbidity index of 0 points (1104 patients undergoing RC and 166 undergoing TMT), they found a higher 5-year OS rate for TMT compared to RC, without reaching statistical significance (65% vs. 57%, respectively; p=0.35) [33]. Selection criteria for TMT have recently been updated by Zlotta et al. [34] in a multicenter retrospective analysis including 722 patients with MIBC, with solitary tumors <7 cm, clinical stage T2–T4 N0 M0, no or unilateral hydronephrosis, no CIS, and no multifocal tumors; 440 patients underwent RC and 282 TMT. Notably, unlike other studies, all patients had similar inclusion criteria, being all suitable for both therapies. Similar rates were observed for 5-year metastasis-free survival (74% for RC and 75% for TMT; p=0.95). Additionally, 5-year cancer-specific survival was 80% for RC and 82% for TMT (p=0.25), and 5-year DFS was 75% for RC and 73% for TMT (p=0.93). Remarkably, 5-year OS was significantly higher for TMT compared to RC (73% vs. 66%, respectively; p=0.01). In fact, only 38 (13%) TMT patients underwent SC, of which 37 (97%) presented muscle-invasive recurrence and there was only one (3%) treatment-related toxicity. The 5-year cancer-specific survival of patients undergoing SC was equivalent to those treated with TMT without the need for SC (85% vs. 84%) [34]. So far, this is the only study comparing RC with TMT in patients with updated and similar inclusion criteria, suitable for both therapies, which reinforces the evidence that both therapies have similar oncological outcomes when using broad inclusion criteria [34].

A meta-analysis was performed with only studies that compared the 5-year survival rates of TMT and RC which included a total of 29 308 patients. A forest plot analysis showed a high heterogeneity among studies (Cochran's Q=65.80 [p<0.001]; I2=93.92%), and no significant differences between TMT and RC (random effects; p=0.4) as shown in Fig. 4.

Figure 4.

The forest plot for the 5-year survival rate under the random-effects model. OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; RC, radical cystectomy; TMT, trimodality therapy.

Concerning QoL, one Markov model simulation study compared TMT versus RC by measuring quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) and reported a gain of 0.59 QALYs with TMT when compared to RC (7.83 vs. 7.24, respectively) [35]. Mak et al. [36] performed a cross-sectional bi-institutional study that compared the long-term QoL in MIBC patients treated with TMT versus RC. Patients with non-metastatic cT2–cT4 MIBC, suitable for RC and disease free for 2 years, were included in the study; 64 patients who received TMT and 109 patients who underwent RC answered the questionnaires 9 years and 7 years after the procedure, respectively. The results showed that both TMT and RC patients had acceptable long-term QoL, but TMT patients were associated with improved general aspects (high physical state score, role, social, emotional, and cognitive functioning, with less fatigue, pain, nausea, and vomiting), urinary (bowel function), and sexual (sexual function and body image) compared to RC ones [36]. Their study supported that TMT could be a good alternative to RC for suitable patients regarding QoL. In addition, Kool et al. [37] compared cost-effectiveness between RC and TMT using Markov model simulation, observing that life-years gained at 5 years and 10 years were slightly higher for TMT when compared to RC, with 4.1 years vs. 4 years and 6.53 life-years vs. 6.40 life-years at 5 years and 10 years, respectively. Additionally, the study analyzed QALYs at 5 years and 10 years, observing moderately higher values for TMT when compared to RC (3.63 vs. 3.35 after 5 years and 5.68 vs. 5.33 after 10 years, respectively) [37]. Regarding costs, despite being similar at 5 years, they differed at 10 years (33 286 USD vs. 40 197 USD) [25]. Meanwhile, Magee et al. [38] reported median costs for RC and TMT of 30 577 USD and 18 979 USD, respectively, being significantly higher for RC (p<0.001). However, the cost associated with follow-up and care was higher for TMT than RC (3094 USD/year vs. 1974 USD/year, respectively) with a non-significant difference (p=0.09) [38]. Finally, Huddart et al. [39] compared several outcomes of patients undergoing TMT versus RC in the Selective Bladder Preservation Against Radical Excision feasibility study, finding that patients undergoing TMT showed an improvement in mean global health status and social functioning, while they were reduced in the RC group [39].

3.2. New treatments using IMT associated with other therapies

IMT, such as ICIs, has provided new perspectives in the treatment of MIBC [17]. Current indications include TURBT and ICIs as single or combined agents, as well as standard NAC [38]. These treatment options may improve the efficacy of standard CMT and become options for cisplatin-ineligible patients [16,48]. Among bladder-sparing therapies, IMT combined with chemoradiotherapy, RT, or CMT has been assessed. These bladder-sparing therapies involving IMT are associated with TURBT, where PD-1 inhibitors such as tislelizumab or pembrolizumab, in addition to PD-L1 inhibitors such as atezolizumab and CTLA-4 inhibitors such as ipilimumab, have been the most used [17].

PD-1, PD-L1, and CTLA-4 are key proteins involved in the regulation of the immune response against tumors [49,50]. These molecules have specific mechanisms that enhance or inhibit T-cell function and their interaction with tumor cells in the tumor microenvironment [51]. In IMT, antibodies serve as inhibitors of these proteins, blocking their inhibitory signals, allowing T-cell activation, and therefore improving the ability of the immune system [49,50]. The most relevant results of IMT to date are summarized in Table 3.

Hu et al. [52] retrospectively evaluated neoadjuvant therapy in patients undergoing RC, comparing IMT, CMT, and immunochemotherapy in patients with MIBC. Although this was not a bladder preservation trial, it did have a subgroup of patients eventually not undergoing RC. In fact, 33 patients declined RC; therefore, TURBT was performed. Of them, 10 patients received immunochemotherapy, 15 CMT, and eight IMT. After a median follow-up of 13 months, 31 (93.94%) achieved DFS while two patients treated with immunochemotherapy and CMT did not achieve DFS [52]. In another series, Xu et al. [17] retrospectively analyzed 25 patients with MIBC unable to undergo or refusing RC. They were treated with TURBT and IMT, specifically tislelizumab (19 patients) or toripalimab (six patients) in combination with RT or CMT. For patients treated with tislelizumab, the 1-year OS and DFS were 100% and 94.7%, respectively, while for patients treated with toripalimab, both were 83.3%. Additionally, the authors mentioned that PD-L1 expression and CMT had no impact on outcomes [17]. One of the limitations of this study was that, although the number of patients who received each drug was reported, the treatment combination that each patient received was not specified. Dahl et al. [53] reported the long-term survival and toxicity results of the NRG Oncology RTOG 0524 study. Their prospective study enrolled 65 patients divided into two groups treated with daily radiation and weekly CMT (paclitaxel) with or without IMT (trastuzumab), respectively. Despite a lower 5-year OS within the IMT group versus the non-IMT group (25% vs. 37.8%, respectively), the 5-year DFS was higher for IMT patients compared to non-IMT patients (15% vs. 31.1%, respectively). There were 18 deaths in the IMT group and 33 in the non-IMT group, of which 11 and 16 were due to disease, respectively [53].

A promising study of IMT with durvalumab with or without RT in older patients with lymph node metastatic disease not undergoing complete TURBT has recently been reported by Joshi et al. [54]. Results showed a complete response of 50%, a 1-year PFS of 73%, and 1-year and 2-year OS of 83.8% and 76.8%, respectively [54].

Several clinical trials evaluating IMT in this clinical scenario are currently underway, showing only initial results so far (Table 4). One phase 2 trial, combining pembrolizumab with gemcitabine and RT in patients refusing or not being eligible for RC, estimated a 1-year DFS rate of 77% and complete response rates of 83% to 100% [55]. Another phase 2 study including 27 patients treated with pembrolizumab together with chemoradiation reported a complete response rate of 88%, a 2-year metastasis-free survival rate of 78%, and a freedom from locoregional progression rate of 87%, with a median survival of 39 months [56]. Vazquez-Estevez et al. [57] evaluated atezolizumab plus RT in 14 patients and observed a 100% complete response rate [57]. Another phase 2 trial with durvalumab plus tremelimumab combined with RT in 32 patients showed an 81% complete response with 6-month DFS and OS rates of 76% and 93%, respectively, and only two patients who went to salvage RC due to MIBC recurrence [58]. Meanwhile, the combination of nivolumab and RT showed a complete response in six out of 14 patients [59]. Finally, another study using tislelizumab associated with NAC (paclitaxel) in 22 patients showed a complete response in 13 of them and a partial response in nine [60]. Until the date of this review, there are no published studies comparing the efficacy among available ICIs.

4. Discussion

To address the knowledge gap in bladder-sparing therapies for non-metastatic MIBC, it is essential to possess up-to-date information for informed treatment decision-making. This review offers a comprehensive knowledge base on this subject, identifying best practices, evaluating the effectiveness of various therapeutic approaches, and guiding treatment strategies to meet the specific needs of each patient.

RC remains the gold standard treatment and the most studied to date [6,[8], [9], [10], [11]]. However, it is related to elevated morbidity, with a large segment of patients not being able to undergo the surgery, reflecting the need for alternatives such as TMT and IMT [13,29,40,43,44]. However, it is difficult to compare all the selected studies with each other, since there are key differences in their design: different clinical variables and demographic characteristics, mixed inclusion criteria, various outcome measurement methodologies, variability in healthcare center levels, and staff expertise, among others.

In this study, a meta-analysis was performed to assess the survival of patients undergoing RC compared to TMT. Only five articles were included in this section as they were the only ones containing data that allowed statistical measurement of both strategies. For the meta-analysis, a random-effects analysis was chosen over a fixed-effect analysis for three reasons: a) a high expectation of heterogeneity among the study results as there are main differences in terms of setting, design, populations, and patient selection, b) broader generalizability of the effects as selected studies show a sample of a larger population of studies and, c) the potential variability in true effect sizes and uncertainty across different studies due to between-study variability [27,61,62]. TMT has a 5-year OS similar to that of RC in selected patients, varying from 30%–73% to 38%–73%, respectively. Although RC seems to be slightly superior when directly comparing results of both therapies [33,40,42], they become similar when the propensity analysis is performed [33,41,45]. Notably, some articles even reported an inverse trend, favoring TMT [33,34,41].

Regarding the quality of evidence, to date there is only low and moderate quality, probably due to mainly retrospective studies on this topic and no complete clinical trials that addressed these therapies, which may be associated with the high risk of bias in patient-dependent domains, but low risk in outcome-dependent domains. Interestingly, the meta-analysis showed no significant difference between the gold-standard therapy RC and the bladder-preservation therapy TMT. Although the evidence available is heterogeneous, oncological outcomes of TMT are equivalent to those of RC for selected patients [33,34,41,45,63]. However, prospective randomized trials are still needed to draw definitive conclusions. Unfortunately, the only prospective controlled trial from the UK, the Selective Bladder Preservation Against Radical Excision trial, failed to recruit enough patients and had a premature closure [39,64]. However, given the results presented in this review, TMT is an alternative for those patients who refuse RC and a suitable strategy for bladder preservation for selected patients with MIBC [5,65]. In any case, selection of therapy should be a decision made by a multidisciplinary team, ensuring not only physical but also mental well-being, in accordance with the patient's preferences. In this topic, the literature included in this review shows a modest improvement for TMT when compared to RC with regards to QoL, which is reflected in improved body image and sexual function [30,35,37].

Regarding IMT, there is still little evidence available when it comes to bladder-sparing treatments. The information available so far comes from ongoing phase 2 trials, showing initial results with complete response rates between 42% and 100% [[55], [56], [57], [58], [59], [60]]. Although these results are promising, they may be biased due to patients' inclusion criteria, as they mostly include patients not eligible for RC because of their morbidity, which increases their associated risks [[55], [56], [57], [58], [59], [60]]. Even though there is still no confirmatory evidence for the efficacy of IMT due to the low number of patients, the lack of long-term follow-up, and the absence of clinical trials comparing it with TMT or RC, IMT is still a promising alternative for bladder preservation in MIBC patients. The medical community is currently awaiting the results of clinical trials underway to evaluate its role in this clinical scenario [[55], [56], [57], [58], [59], [60]].

Limitations of this review are that information on TMT comes from retrospective studies and in general, the cohorts have disparities, due to, in most of the studies, the patients who underwent TMT were those who were not candidates for RC due to comorbidity burden. As for IMT, the evidence is limited in bladder preservation therapy, so the trials performed so far include few patients, who are generally not candidates for other treatments, making direct comparison with other treatments impossible.

5. Future directions

Just as IMT studies have used cellular approaches considering PD-L1 and PD-1 proteins, new treatments are being developed to improve BC outcomes. For example, new strategies including biomarkers [66] or IMT agents combined with RT or CMT [67] as well as new devices [68] have shown promising results, with 3-year OS rates of up to 50%. Other studies have been considering genetic variability and the tumor microenvironment based on disparities in gene expression profiles and aggressiveness during tumor development [51]. Nowadays there is growing evidence regarding the tumor microenvironment and different therapeutic responses among patients; in vitro and in vivo studies (summarized in [51]) in murine models have elucidated the bidirectional relation between different tumor and non-tumor cell types within the microenvironment. In this context, the strategy of subdividing bladder tumors into subtypes by genetics or the microenvironment may offer a more targeted and effective therapy [69].

6. Conclusion

While RC remains the gold standard treatment for MIBC despite its high morbidity burden, bladder preservation therapies serve as an alternative that could offer equivalent oncological outcomes in selected patients with lower morbidity. This is the first study to analyze QoL between both treatments, supporting the benefit of TMT in this regard. So far, there are no high-quality data directly comparing these treatments; therefore, the decision of which strategy to use should be made by a multidisciplinary team that considers the available evidence in conjunction with patient preferences. In clinical practice, this offers an alternative to classical management, which could favor selected patients. Although IMT is increasingly being incorporated into clinical trials with promising results, there is still insufficient evidence for its routine use in clinical practice. The next steps should be prospective randomized comparative studies between the different approaches to understand which may be best for each type of patient.

Author contributions

Study concept and design: Diego Parrao, Carolina B. Lindsay, Juan Cristóbal Bravo.

Data acquisition: Diego Parrao, Nemecio Lizana, Catalina Saavedra, Valentina Fernández, Carolina B. Lindsay, Matías Larrañaga.

Data analysis: Diego Parrao, Nemecio Lizana, Catalina Saavedra, Valentina Fernández, Carolina B. Lindsay, Matías Larrañaga, Juan Cristóbal Bravo.

Drafting of manuscript: Diego Parrao, Nemecio Lizana, Catalina Saavedra, Carolina B. Lindsay, Juan Cristóbal Bravo.

Critical revision of the manuscript: Diego Parrao, Mario I. Fernández, Juan Cristóbal Bravo.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgement

We express gratitude to the Research Unit of Hospital Dr. Franco Ravera Zunino for its support in the review and validation of methodology.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Tongji University.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajur.2024.08.005.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article.

References

- 1.Ferlay J, Ervik M, Lam F, Laversanne M, Colombet M, Mery L, et al. Global Cancer observatory: cancer today. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer. https://gco.iarc.who.int/today. [Accessed 10 August 2024].

- 2.Burger M., Catto J.W.F., Dalbagni G., Grossman H.B., Herr H., Karakiewicz P., et al. Epidemiology and risk factors of urothelial bladder cancer. Eur Urol. 2013;63:234–241. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2012.07.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yang X., Zhang S., Cui Y., Li Y., Song X., Pang J. Efficacy and safety of transurethral resection of bladder tumour combined with chemotherapy and immunotherapy in bladder-sparing therapy in patients with T1 high-grade or T2 bladder cancer: a protocol for a randomized controlled trial. BMC Cancer. 2023;23:320. doi: 10.1186/s12885-023-10798-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lobo N., Afferi L., Moschini M., Mostafid H., Porten S., Psutka S.P., et al. Epidemiology, screening, and prevention of bladder cancer. Eur Urol Oncol. 2022;5:628–639. doi: 10.1016/j.euo.2022.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee H.W., Kwon W.A., Nguyen N.T., Phan D.T.T., Seo H.K. Approaches to clinical complete response after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in muscle-invasive bladder cancer: possibilities and limitations. Cancers (Basel) 2023;15:1323. doi: 10.3390/cancers15041323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alfred Witjes J., Max Bruins H., Carrión A., Cathomas R., Compérat E.M., Efstathiou J.A., et al. European Association of Urology guidelines on muscle-invasive and metastatic bladder cancer: summary of the 2023 guidelines. Eur Urol. 2024;85:17–31. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2024.03.002. Erratum in: Eur Urol 2024;85:e180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lenis A.T., Lec P.M., Chamie K., Mshs M.D. Bladder cancer. JAMA. 2020;324:1980–1991. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.17598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alfred Witjes J., Max Bruins H., Carrión A., Cathomas R., Compérat E., Efstathiou J.A., et al. European Association of Urology guidelines on muscle-invasive and metastatic bladder cancer: summary of the 2023 guidelines. Eur Urol. 2024;85:17–31. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2023.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kamat A.M., Apolo A.B., Babjuk M., Bivalacqua T.J., Black P.C., Buckley R., et al. Definitions, end points, and clinical trial designs for bladder cancer: recommendations from the Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer and the International Bladder Cancer Group. J Clin Oncol. 2023;41:5437–5447. doi: 10.1200/JCO.23.00307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Omorphos N.P., Pansaon Piedad J.C., Vasdev N. Guideline of guidelines: muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Turk J Urol. 2021;47:S71–S78. doi: 10.5152/tud.2020.20337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chang S.S., Bochner B.H., Chou R., Dreicer R., Kamat A.M., Lerner S.P., et al. Treatment of non-metastatic muscle-invasive bladder cancer: AUA/ASCO/ASTRO/SUO guideline. J Urol. 2017;198:552–559. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2017.04.086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tyson M.D., Barocas D.A. Quality of life after radical cystectomy. Urol Clin North Am. 2018;45:249–256. doi: 10.1016/j.ucl.2017.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maibom S.L., Joensen U.N., Poulsen A.M., Kehlet H., Brasso K., Røder M.A. Short-term morbidity and mortality following radical cystectomy: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2021;11 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-043266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fan X., He W., Huang J. Bladder-sparing approaches for muscle invasive bladder cancer: a narrative review of current evidence and future perspectives. Transl Androl Urol. 2023;12:802–808. doi: 10.21037/tau-23-124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hall E., Hussain S.A., Porta N., Lewis R., Crundwell M., Jenkins P., et al. Chemoradiotherapy in muscle-invasive bladder cancer: 10-yr follow-up of the phase 3 randomised controlled BC2001 trial. Eur Urol. 2022;82:273–279. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2022.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goodstein T., Wang S.J., Lee C.T. Bladder preservation in urothelial carcinoma: current trends and future directions. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 2021;15:253–259. doi: 10.1097/SPC.0000000000000579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xu C., Zou W., Zhang L., Xu R., Li Y., Feng Y., et al. Real-world retrospective study of immune checkpoint inhibitors in combination with radiotherapy or chemoradiotherapy as a bladder-sparing treatment strategy for muscle-invasive bladder urothelial cancer. Front Immunol. 2023;14 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1162580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mathes J., Rausch S., Todenhöfer T., Stenzl A. Trimodal therapy for muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2018;18:1219–1229. doi: 10.1080/14737140.2018.1535314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ruiz de Porras V., Pardo J.C., Etxaniz O., Font A. Neoadjuvant therapy for muscle-invasive bladder cancer: current clinical scenario, future perspectives, and unsolved questions. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2022;178 doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2022.103795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.National Collaborating Centre for Cancer (UK) National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE); London: 2015 Feb. Bladder cancer: diagnosis and management.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK305022/ (NICE guideline, No. 2) [Google Scholar]

- 21.Singh A., Osbourne A.S., Koshkin V.S. Perioperative immunotherapy in muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2023;24:1213–1230. doi: 10.1007/s11864-023-01113-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liberati A., Altman D.G., Tetzlaff J., Mulrow C., Gotzsche P.C., Ioannidis J.P.A., et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 2009;339 doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sterne J.A.C., Savović J., Page M.J., Elbers R.G., Blencowe N.S., Boutron I., et al. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2019;366:l4898. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l4898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chandler J., Clarke M., McKenzie J., Boutron I., Welch V., editors. 2016. Cochrane methods. (Cochrane database of systematic reviews). 10 (Suppl 1). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Higgins J.P.T., Morgan R.L., Rooney A.A., Taylor K.W., Thayer K.A., Silva R.A., et al. A tool to assess risk of bias in non-randomized follow-up studies of exposure effects (ROBINS-E) Environ Int. 2024;186 doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2024.108602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aguayo-Albasini J.L., Flores-Pastor B., Soria-Aledo V. [GRADE system: classification of quality of evidence and strength of recommendation] Cir Esp. 2014;92:82–88. doi: 10.1016/j.ciresp.2013.08.002. [Article in Spanish] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dettori J.R., Norvell D.C., Chapman J.R. Fixed-effect vs. random-effects models for meta-analysis: 3 points to consider. Global Spine J. 2022;12:1624–1626. doi: 10.1177/21925682221110527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hamid A.R.A.H., Ridwan F.R., Parikesit D., Widia F., Mochtar C.A., Umbas R. Meta-analysis of neoadjuvant chemotherapy compared to radical cystectomy alone in improving overall survival of muscle-invasive bladder cancer patients. BMC Urol. 2020;20:158. doi: 10.1186/s12894-020-00733-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vlaming M., Kiemeney L.A.L.M., van der Heijden A.G. Survival after radical cystectomy: progressive versus de novo muscle invasive bladder cancer. Cancer Treat Res Commun. 2020;25 doi: 10.1016/j.ctarc.2020.100264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yang L.S., Shan B.L., Shan L.L., Chin P., Murray S., Ahmadi N., et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of quality of life outcomes after radical cystectomy for bladder cancer. Surg Oncol. 2016;25:281–297. doi: 10.1016/j.suronc.2016.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.James N.D., Hussain S.A., Hall E., Jenkins P., Tremlett J., Rawlings C., et al. Radiotherapy with or without chemotherapy in muscle-invasive bladder cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1477–1488. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1106106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Giacalone N.J., Shipley W.U., Clayman R.H., Niemierko A., Drumm M., Heney N.M., et al. Long-term outcomes after bladder-preserving tri-modality therapy for patients with muscle-invasive bladder cancer: an updated analysis of the Massachusetts general hospital experience. Eur Urol. 2017;71:952–960. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2016.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Softness K., Kaul S., Fleishman A., Efstathiou J., Bellmunt J., Kim S.P., et al. Radical cystectomy versus trimodality therapy for muscle-invasive urothelial carcinoma of the bladder. Urol Oncol. 2022;40:272.e1–272.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2021.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zlotta A.R., Ballas L.K., Niemierko A., Lajkosz K., Kuk C., Miranda G., et al. Radical cystectomy versus trimodality therapy for muscle-invasive bladder cancer: a multi-institutional propensity score matched and weighted analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2023;24:669–681. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(23)00170-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Royce T.J., Feldman A.S., Mossanen M., Yang J.C., Shipley W.U., Pandharipande P.V., et al. Comparative effectiveness of bladder-preserving tri-modality therapy versus radical cystectomy for muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2019;17:23–31.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.clgc.2018.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mak K.S., Smith A.B., Eidelman A., Clayman R., Niemierko A., Cheng J.S., et al. Quality of life in long-term survivors of muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2016;96:1028–1036. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2016.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kool R., Yanev I., Hijal T., Vanhuyse M., Cury F.L., Souhami L., et al. Trimodal therapy vs. radical cystectomy for muscle-invasive bladder cancer: a Canadian cost-effectiveness analysis. Can Urol Assoc J. 2022;16:189–198. doi: 10.5489/cuaj.7430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Magee D.E., Cheung D.C., Hird A.E., Chung P., Warde P., Catton C., et al. Cost of bladder cancer care: a single-center comparison of radical cystectomy and trimodal therapy. Urol Pract. 2023;10:293–299. doi: 10.1097/UPJ.0000000000000403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Huddart R.A., Hall E., Lewis R., Birtle A. Life and death of SPARE (Selective Bladder Preservation Against Radical Excision): reflections on why the SPARE trial closed. BJU Int. 2010;106:753–755. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2010.09537.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cahn D.B., Handorf E.A., Ghiraldi E.M., Ristau B.T., Geynisman D.M., Churilla T.M., et al. Contemporary use trends and survival outcomes in patients undergoing radical cystectomy or bladder-preservation therapy for muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Cancer. 2017;123:4337–4345. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kulkarni G.S., Hermanns T., Wei Y., Bhindi B., Satkunasivam R., Athanasopoulos P., et al. Propensity score analysis of radical cystectomy versus bladder-sparing trimodal therapy in the setting of a multidisciplinary bladder cancer clinic. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:2299–2305. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.69.2327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ritch C.R., Balise R., Prakash N.S., Alonzo D., Almengo K., Alameddine M., et al. Propensity matched comparative analysis of survival following chemoradiation or radical cystectomy for muscle-invasive bladder cancer. BJU Int. 2018;121:745–751. doi: 10.1111/bju.14109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Grossmann N.C., Rajwa P., Quhal F., König F., Mostafaei H., Laukhtina E., et al. Comparative outcomes of primary versus recurrent high-risk non-muscle-invasive and primary versus secondary muscle-invasive bladder cancer after radical cystectomy: results from a retrospective multicenter study. Eur Urol Open Sci. 2022;39:14–21. doi: 10.1016/j.euros.2022.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pfail J.L., Audenet F., Martini A., Tomer N., Paranjpe I., Daza J., et al. Survival of patients with muscle-invasive urothelial cancer of the bladder with residual disease at time of cystectomy: a comparative survival analysis of treatment modalities in the national cancer database. Bladder Cancer. 2020;6:265–276. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Qiu J., Zhang H., Xu D., Li L., Xu L., Jiang Y., et al. Comparing long-term survival outcomes for muscle-invasive bladder cancer patients who underwent with radical cystectomy and bladder-sparing trimodality therapy: a multicentre cohort analysis. J Oncol. 2022;2022:1–11. doi: 10.1155/2022/7306198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Efstathiou J.A., Spiegel D.Y., Shipley W.U., Heney N.M., Kaufman D.S., Niemierko A., et al. Long-term outcomes of selective bladder preservation by combined-modality therapy for invasive bladder cancer: the MGH experience. Eur Urol. 2012;61:705–711. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2011.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zapatero A., Martin De Vidales C., Arellano R., Ibañez Y., Bocardo G., Perez M., et al. Long-term results of two prospective bladder-sparing trimodality approaches for invasive bladder cancer: neoadjuvant chemotherapy and concurrent radio-chemotherapy. Urology. 2012;80:1056–1062. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2012.07.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kaur N., Figueiredo S., Bouchard V., Moriello C., Mayo N. Where have all the pilot studies gone? A follow-up on 30 years of pilot studies in clinical rehabilitation. Clin Rehabil. 2017;31:1238–1248. doi: 10.1177/0269215517692129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tang Q., Chen Y., Li X., Long S., Shi Y., Yu Y., et al. The role of PD-1/PD-L1 and application of immune-checkpoint inhibitors in human cancers. Front Immunol. 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.964442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hosseini A., Gharibi T., Marofi F., Babaloo Z., Baradaran B. CTLA-4: from mechanism to autoimmune therapy. Int Immunopharmacol. 2020;80 doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2020.106221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Patwardhan M.V., Mahendran R. The bladder tumor microenvironment components that modulate the tumor and impact therapy. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24 doi: 10.3390/ijms241512311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hu J., Chen J., Ou Z., Chen H., Liu Z., Chen M., et al. Neoadjuvant immunotherapy, chemotherapy, and combination therapy in muscle-invasive bladder cancer: a multi-center real-world retrospective study. Cell Rep Med. 2022;3 doi: 10.1016/j.xcrm.2022.100785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dahl D.M., Karrison T.G., Michaelson M.D., Pham H.T., Wu C., Swanson G.P., et al. Long-term outcomes of chemoradiation for muscle-invasive bladder cancer in noncystectomy candidates. Final results of NRG Oncology RTOG 0524—a phase 1/2 trial of paclitaxel + trastuzumab with daily radiation or paclitaxel alone with daily irradiation. Eur Urol Oncol. 2024;7:83–90. doi: 10.1016/j.euo.2023.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Joshi M., Tuanquin L., Zhu J., Walter V., Schell T., Kaag M., et al. Concurrent durvalumab and radiation therapy (DUART) followed by adjuvant durvalumab in patients with localized urothelial cancer of bladder: results from phase II study, BTCRC-GU15-023. J Immunother Cancer. 2023;11 doi: 10.1136/jitc-2022-006551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Balar A.V., Milowsky M.I., O'Donnell P.H., Alva A.S., Kollmeier M., Rose T.L., et al. Pembrolizumab (pembro) in combination with gemcitabine (Gem) and concurrent hypofractionated radiation therapy (RT) as bladder sparing treatment for muscle-invasive urothelial cancer of the bladder (MIBC): a multicenter phase 2 trial. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39 doi: 10.1200/JCO.2021.39.15_suppl.4504. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Weickhardt A.J., Foroudi F., Xie J., Kanojia K., Sidhom M., Pal A., et al. 1739P Pembrolizumab with chemoradiotherapy as treatment for muscle invasive bladder cancer: analysis of safety and efficacy of the PCR-MIB phase II clinical trial (ANZUP 1502) Ann Oncol. 2022;33:S1332. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2022.07.1817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vazquez-Estevez S., Fernandez-Calvo O., Bonfill-Abella T., Sequero S., Martínez-Madueño F., Romero-Laorden N., et al. Efficacy and safety of atezolizumab concurrent with radiotherapy in patients with muscle-invasive bladder cancer: an interim analysis of the ATEZOBLADDERPRESERVE phase II trial (SOGUG-2017-A-IEC(VEJ)-4) J Clin Oncol. 2022;40 doi: 10.1200/JCO.2022.40.16_suppl.4588. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Garcia del Muro X., Valderrama B.P., Medina A., Cuellar M.A., Etxaniz O., Gironés Sarrió R., et al. Phase II trial of durvalumab plus tremelimumab with concurrent radiotherapy (RT) in patients (pts) with localized muscle invasive bladder cancer (MIBC) treated with a selective bladder preservation approach: IMMUNOPRESERVE-SOGUG trial. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39:4505. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2021.39.15_suppl.4505. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Vaishampayan U.N., Heilbrun L.K., Vaishampayan N., Li C., Shi D., Frazier A., et al. 776P phase II trial of concurrent nivolumab in urothelial bladder cancer with radiation therapy in localized/locally advanced disease for chemotherapy ineligible patients [NUTRA trial] Ann Oncol. 2020;31:S596. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2020.08.848. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Niu Y., Hu H., Wang H., Tian D., Zhao G., Shen C., et al. Phase II clinical study of tislelizumab combined with nab-paclitaxel (TRUCE-01) for muscle-invasive urothelial bladder carcinoma: bladder preservation subgroup analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2022;40:4589. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2022.40.16_suppl.4589. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Shah A., Jones M.P., Holtmann G.J. Basics of meta-analysis. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2020;39:503–513. doi: 10.1007/s12664-020-01107-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lehrer E.J., Wang M., Sun Y., Zaorsky N.G. An introduction to meta-analysis. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2023;115:564–571. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2022.07.1831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ran S., Yang J., Hu J., Fang L., He W. Identifying optimal candidates for trimodality therapy among nonmetastatic muscle-invasive bladder cancer Patients. Curr Oncol. 2023;30:10166–10178. doi: 10.3390/curroncol30120740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Huddart R.A., Birtle A., Maynard L., Beresford M., Blazeby J., Donovan J., et al. Clinical and patient-reported outcomes of SPARE—a randomised feasibility study of selective bladder preservation versus radical cystectomy. BJU Int. 2017;120:639–650. doi: 10.1111/bju.13900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ploussard G., Daneshmand S., Efstathiou J.A., Herr H.W., James N.D., Rödel C.M., et al. Critical analysis of bladder sparing with trimodal therapy in muscle-invasive bladder cancer: a systematic review. Eur Urol. 2014;66:120–137. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2014.02.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Geynisman D.M., Abbosh P., Ross E.A., Zibelman M.R., Ghatalia P., Anari F., et al. A phase II trial of risk-enabled therapy after initiating neoadjuvant chemotherapy for bladder cancer (RETAIN) J Clin Oncol. 2023;41:438. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2023.41.6_suppl.438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Singh P., Efstathiou J.A., Plets M., Jhavar S.G., Delacroix S., Tripathi A., et al. INTACT (S/N1806): phase III randomized trial of concurrent chemoradiotherapy with or without atezolizumab in localized muscle invasive bladder cancer—toxicity update on first 213 patients. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2022;114:S76–S77. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2022.07.475. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tyson M.D., Morris D., Palou J., Rodriguez O., Mir M.C., Dickstein R.J., et al. Safety, tolerability, and preliminary efficacy of TAR-200 in patients with muscle-invasive bladder cancer who refused or were unfit for curative-intent therapy: a phase 1 study. J Urol. 2023;209:890–900. doi: 10.1097/JU.0000000000003195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Meeks J.J., Al-Ahmadie H., Faltas B.M., Taylor J.A., Flaig T.W., DeGraff D.J., et al. Genomic heterogeneity in bladder cancer: challenges and possible solutions to improve outcomes. Nat Rev Urol. 2020;17:259–270. doi: 10.1038/s41585-020-0304-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.