Abstract

Arcobacter butzleri is an emerging pathogen associated with human gastrointestinal illness. Despite its growing significance, information on the resistance of this microorganism is limited due to the lack of practical antimicrobial susceptibility testing (AST) methods and well-defined interpretive criteria. This study evaluates agar dilution as a reliable alternative to the broth microdilution method, the current reference protocol approved by the CLSI Veterinary AST (VAST) subcommittee. A total of 415 A. butzleri isolates were tested against ciprofloxacin, erythromycin, gentamicin, and tetracycline using both agar dilution and broth microdilution methods under aerobic and microaerobic conditions. Additionally, tentative epidemiological cut-off (ECOFF) values of these antimicrobials were determined by visual estimation and the statistical tool, ECOFFinder. Agreement between methods was assessed using Cohen’s kappa and Gwet’s AC1. Our results reveal that aerobic agar dilution at 24 h showed the highest agreement with the reference broth microdilution, particularly for ciprofloxacin, erythromycin, and gentamicin. The proposed tentative ECOFFs for A. butzleri against ciprofloxacin, erythromycin, gentamicin, and tetracycline were 0.5 µg/ml, 16 µg/ml, 2 µg/ml, and 16 µg/ml, respectively. The findings from this study represent a critical advancement toward establishing interpretive criteria tailored specifically for Arcobacter spp. This study underscores aerobic agar dilution as a reliable yet scalable approach for AMR surveillance of A. butzleri.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-025-16223-x.

Keywords: Agar dilution method, Antimicrobial susceptibility testing, Arcobacter butzleri, Epidemiological Cut-Off values (ECOFF)

Subject terms: Microbiology, Antimicrobial resistance

Introduction

Arcobacter spp. are Gram-negative, curved bacilli bacteria that are motile and non-spore forming. Arcobacter spp. are more aerotolerant, enabling growth in aerobic as well as microaerobic conditions typically at 37 °C1. They share several phenotypic and genotypic characteristics with Campylobacter species, which led to their initial classification within the Campylobacter genus. However, accumulating phylogenetic evidence and other molecular markers demonstrated that these species formed a distinct lineage, prompting their reclassification into the genus Arcobacter in 19912. They were again reclassified as Aliarcobacter spp. as part of a proposed taxonomic revision that divided the genus into several new genera (e.g., Aliarcobacter, Pseudarcobacter, Malaciobacter, Halarcobacter, and Poseidonibacter)3. However, a recent publication proved high genomic similarity among these genera, which led to their retention, including A. butzleri, within the genus Arcobacter to avoid clinical and epidemiological confusion4.

A. butzleri is an emerging zoonotic pathogen causing food-borne illnesses, deemed as one of the most commonly isolated bacteria in patients suffering diarrhea5. Arcobacteriosis is exhibited by symptoms such as diarrhea, vomiting, abdominal pain, fever, and even septicemia in cases involving immune-suppressed patients. The infection is usually self-limiting as symptoms may resolve without the intervention of antibiotics. However, in severe cases, the clinical signs may worsen and the use of antibiotics may become inevitable. The common choices of antibiotics for the treatment of Arcobacter infections include quinolones, tetracyclines, macrolides, and aminoglycosides6–8.

Studies on the antimicrobial susceptibility of Arcobacter spp. in the past have shown contradictory results across different studies6,7,9,10, especially when applying different antimicrobial susceptibility testing (AST) methods, such as broth microdilution, agar dilution, and disk diffusion. The discrepancies between these past findings may be due to the fact that there is yet a gold standard method for AST of Arcobacter spp., and scarce information regarding the epidemiological cut-off (ECOFF) values and clinical breakpoints of the antibiotics tested against the bacteria. Riesenberg et al. (2017)8 had published a study on a standardized protocol for the broth microdilution method, which has been approved by the Veterinary Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (VAST) Subcommittee of the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). Despite this significant advancement and its widespread use for antimicrobial susceptibility testing across various microorganisms, the broth microdilution method presents several challenges, particularly when a high number of samples must be tested manually. Although automation can help address these limitations, automated broth microdilution systems are expensive. Moreover, if specially customized microtiter plates are required, this will further increase the cost of conducting the procedure. Many laboratories, especially in low- and middle-income countries, lack the infrastructure for automation and must rely on manual preparation, which increases labor demands and reduces the feasibility of testing large sample sizes. Additionally, past practice in our lab has shown that the manual process of broth microdilution is more challenging with a tendency to be less consistent than the agar dilution method when testing for antimicrobial susceptibility of Campylobacter and Arcobacter (unpublished data). On the contrary, the agar dilution method can accommodate a greater number of samples per plate, and the use of agar provides a more stable and consistent environment for growth compared to broth media11. Better growth gives off distinct visibility on the agar surface and enhances the clarity and accuracy of result interpretation.

Considering the limitations of the broth microdilution method and the lack of a practical standard AST for Arcobacter spp., this study evaluates agar dilution as a reliable alternative approach. The primary aim of this study was to assess the level of agreement between the proposed agar dilution methods and the reference broth microdilution method for A. butzleri AST. Additionally, the study tried to suggest tentative ECOFFs for key antimicrobials, including ciprofloxacin, erythromycin, gentamicin, and tetracycline against A. butzleri, thereby contributing to the development of standardized interpretive criteria for this emerging pathogen.

Materials and methods

Sample source

The samples used in this study consisted of previously isolated Arcobacter strains from various meat sources (chicken, duck, beef and pork) across Bangkok, Thailand and archived in the stock collection of the Department of Veterinary Public Health, Faculty of Veterinary Science, Chulalongkorn University.

Confirmation and identification of A. butzleri

The isolates were subcultured on Columbia agar supplemented with 5% sheep blood and incubated for 48 h at 37 °C under microaerobic conditions (approximately 5% O₂, 10% CO₂, and 85% N₂). The viable colonies were identified based on morphological criteria (small and round, with translucent to beige colour) and underwent DNA extraction by the whole-cell boiling method. Confirmation and identification of A. butzleri were carried out by PCR using species-specific primers previously described by Douidah et al. (2010)12, with A. butzleri NCTC 12481 included as the positive control.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing

All 415 confirmed A. butzleri isolates were tested against four different antimicrobial agents, including ciprofloxacin, erythromycin, gentamicin, and tetracycline with the test range as follows: ciprofloxacin (0.002–32 µg/ml); erythromycin (0.06–128 µg/ml); gentamicin (0.06–16 µg/ml); and tetracycline (0.06–64 µg/ml). Antimicrobial susceptibility testing in this study was conducted by both broth microdilution and agar dilution methods. The broth microdilution method, performed under aerobic conditions at 37 °C for 24 h as suggested by Riesenberg et al. (2017)8, served as the reference method. To assess the feasibility of agar dilution as a potential alternative, this method was performed under the following conditions: (1) aerobic conditions at 37 °C for 24 h to mimic the reference method, with additional evaluations at 48 h, and (2) microaerobic conditions at 37 °C for 48 h, adapted from the CLSI standard for Campylobacter spp.13. The use of Campylobacter-based conditions is common in previous studies involving Arcobacter, due to the close phenotypic and genotypic similarities between the two genera. The incubation temperature of 37 °C for 48 h was selected instead of 42 °C for 24 h based on previous findings indicating that optimal growth of Arcobacter occurs at temperatures lower than 42 °C2,14.

Agar dilution

To successfully perform AST of A. butzleri, the addition of a growth supplement, such as blood or foetal bovine serum (FBS), to the medium is required. According to Riesenberg et al. (2017)8, no significant differences in minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) values were observed between FBS- and blood-supplemented media. However, since FBS is not currently approved for AST under current CLSI standards8, Mueller-Hinton agar supplemented with 5% defibrinated sheep blood was selected as the growth medium for the agar dilution method. Our preliminary tests also showed that blood improves colony visualization, thereby supporting consistent MIC determination. A stock solution of each antimicrobial agent was prepared and subsequently subjected to two-fold serial dilutions. Each concentration was then incorporated into individual agar plates. A. butzleri isolates were adjusted to a 0.5 McFarland standard by picking a few colonies from a fresh agar plate and inoculated onto the plates containing varying concentrations of antimicrobials. The inoculated plates were then incubated at 37 °C for 48 h under microaerobic conditions with Campylobacter jejuni ATCC 33560 as the reference strain. The same procedure was then repeated under aerobic conditions, with incubation at 37 °C for 24 and 48 h. Escherichia coli ATCC 25922 was used as the reference strain for the aerobic test.

Broth microdilution

As the protocol described by Riesenberg et al. (2017)8 has been approved by the VAST subcommittee of the CLSI, results derived from this method were used as the reference for comparison in this study. The test was conducted using Cation-adjusted Mueller Hinton Broth (CAMHB), supplemented with 5% FBS. Antibiotics, which were serially diluted in two-fold concentration steps, were added into a microtiter plate containing the aforementioned media, followed by the inoculation of the isolates that were picked from a fresh agar plate and adjusted to a 0.5 McFarland standard. The plates were then incubated at 37 °C for 24 h under aerobic conditions with E. coli ATCC 25922 and Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 29213 as the reference strains. The range of antimicrobial agents tested by the broth microdilution method was similar to that of the agar dilution method.

Determination of tentative ECOFF values

Since there are no antimicrobial resistance breakpoints for Arcobacter spp. currently available, the tentative ECOFF values for A. butzleri were determined to establish a threshold for classifying isolates as either wild type or non-wild type. Subsequently, the level of agreement between the proposed agar dilution methods and the reference broth microdilution method was assessed.

The tentative ECOFF values were obtained through both visual and statistical estimations of compiled MIC distributions from the current and previous publications5–8,15–18 that fulfilled the criteria for developing tentative ECOFFs, as outlined by EUCAST19. Visually, the ECOFF value is typically placed two-fold dilution steps higher than the mode of the wild type group20. However, this visual estimation is a simplified method that is not always accurate, and more precision is achieved by utilising statistical tools to better define the cut-off value. The statistical estimation was conducted using ECOFFinder, a tool developed by Turnidge et al. (2006)21 that applies an iterative curve-fitting approach based on a cumulative log-normal distribution to determine the ECOFF values at 99%.

Statistical analysis

The agreement between agar dilution and broth microdilution methods was assessed using categorical agreement (CA), measured by Cohen’s kappa coefficient and Gwet’s AC1 to account for paradoxically low kappa value22, and essential agreement (EA). In addition, the percentage agreement was reported to indicate raw concordance between methods. Agreement was assessed for each antimicrobial agent based on categorical classification as wild type or non-wild type. The strength of agreement for Cohen’s kappa was interpreted according to the standard nomenclature: 0–0.20 Poor; 0.21–0.40 Fair; 0.41–0.60 Moderate; 0.61–0.80 Good; 0.81–1.00 Very Good23. Although Gwet’s AC1 also measures the level of agreement between methods, it should not be interpreted using the same criteria as Cohen’s kappa. Instead, its interpretation is based on the relative agreement values observed between the methods within the given context22. Although Gwet’s AC1 does not rely on the same statistical assumptions as Cohen’s kappa, many researchers continue to apply conventional interpretive thresholds of kappa for convenience and comparative purposes. Additionally, EA was assessed based on CLSI (2015) guidelines24, which consider an EA of ≥ 90% acceptable for method comparison studies. All statistical calculations were conducted using SAS software version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

MIC distribution by the reference broth microdilution and the proposed agar dilution methods

Before determining the MICs of the tested isolates, the MICs of quality control strains were assessed to ensure the accuracy and reliability of the AST procedures used in this study. The MIC values obtained for E. coli ATCC 25922, S. aureus ATCC 29213, and C. jejuni ATCC 33560 are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Most common MIC values of the QC strains obtained in the current study.

| Strains | MIC ranges for antibiotics (µg/ml) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ciprofloxacin | Erythromycin | Gentamicin | Tetracycline | |

| E. coli ATCC 25922a | 0.008–0.016 | N/A | 0.25–0.5 | 0.5–2 |

| S. aureus ATCC 29213b | 0.25–0.5 | 0.5–1 | 0.25–0.5 | 0.5–1 |

| C. jejuni ATCC 33560c | 0.125–0.25 | 1–4 | 1–2 | 0.5–1 |

aE. coli ATCC 25922 was tested under aerobic conditions at 37 °C for 24 h using both agar dilution and broth microdilution methods.

bS. aureus ATCC 29213 was tested under aerobic conditions at 37 °C for 24 h by the broth microdilution method.

cC. jejuni ATCC 33560 was tested under microaerobic conditions at 37 °C for 48 h by the agar dilution method.

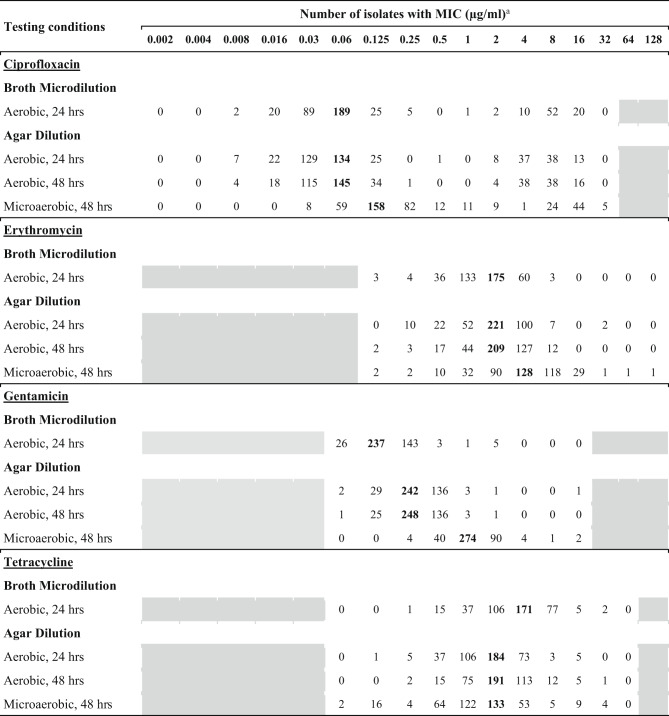

The MIC results from the reference broth microdilution and the proposed agar dilution methods for ciprofloxacin, erythromycin, and tetracycline showed the same mode of MIC, or at most a one dilution step difference, except for gentamicin. For gentamicin, the mode determined by the agar dilution method under microaerobic conditions at 37 °C for 48 h was three dilution steps higher than that obtained by the broth microdilution method. The MIC distribution observed in this study is presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

MIC distribution against ciprofloxacin, erythromycin, gentamicin, and tetracycline by the broth microdilution and different agar dilution methods

aThe number of isolates in bold indicates the most common MIC of each method. The grey areas represent concentration steps that were not included in the test panels.

Determination of tentative ECOFF values

MIC distributions for A. butzleri from the current study and previous publications5–8,15–18 that fit the standards set by EUCAST were compiled to determine the tentative ECOFF values of each antibiotic. The comparison of MIC distributions between the current study and previously published data can be found in the supplemental information (Tables S1-S4).

The visually estimated ECOFFs, defined as two dilution steps above the mode of the wild type MIC distribution, were 0.25 µg/ml for ciprofloxacin, 8 µg/ml for erythromycin, 1 µg/ml for gentamicin, and 8 µg/ml for tetracycline. These values coincided with the 95% ECOFF values calculated by ECOFFinder for all tested antibiotics. A 95% confidence interval is typically considered sufficient for routine surveillance purposes to distinguish wild type from non-wild type populations. However, a 99% confidence interval may be preferred when proposing tentative ECOFFs that require greater statistical precision25. Accordingly, the proposed tentative ECOFFs for A. butzleri generated by ECOFFinder at the 99% threshold were 0.5 µg/ml for ciprofloxacin, 16 µg/ml for erythromycin, 2 µg/ml for gentamicin, and 16 µg/ml for tetracycline. These values are presented in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Summarised MIC distributions from the current study and past publications for ciprofloxacin, erythromycin, gentamicin, and tetracycline with their respective tentative ECOFF values as demarcated by the dotted lines. The red dotted line represents the visually estimated ECOFF value, which is equal to the 95% ECOFF calculated by ECOFFinder. The green dotted line represents the proposed tentative ECOFF values of A. butzleri, which is 99% ECOFF value calculated by ECOFFinder.

Determination of the level of agreement between the AST methods

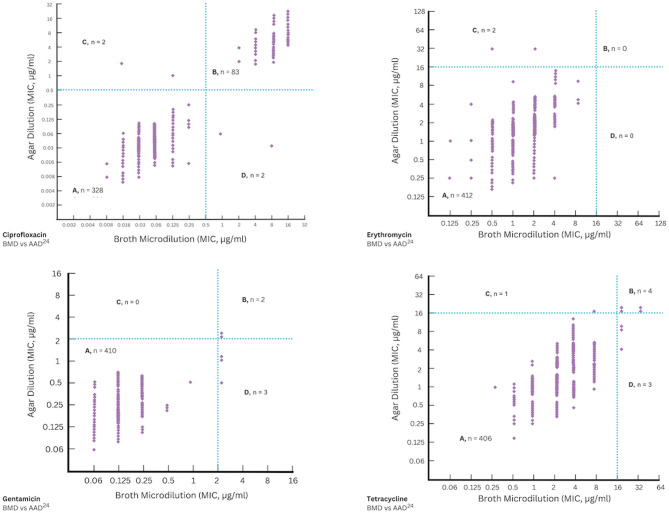

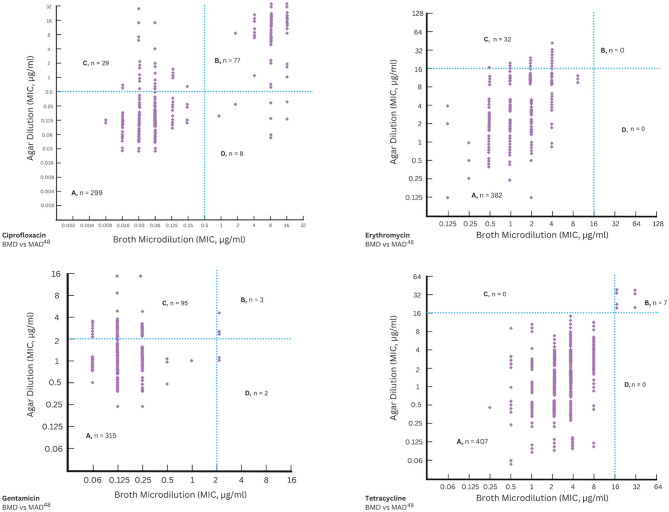

Following the determination of tentative ECOFF values for each antimicrobial agent, these cut-off values were used as thresholds to categorise the isolates as wild type or non-wild type. The level of CA was calculated using Cohen’s kappa and Gwet’s AC1 by comparing the proposed agar dilution methods under aerobic conditions for 24 and 48 hours (AAD24 and AAD48) and under microaerobic conditions for 48 hours (MAD48) to the reference broth microdilution method under aerobic conditions for 24 hours (BMD). Additionally, EA was calculated to assess the consistency of MIC values for the same isolate when tested using different methods. The proposed agar dilution methods showed varying levels of agreement with BMD, depending on the antimicrobial agent and incubation conditions. The levels of categorical and essential agreement are summarized in Tables 3 and 4, respectively. CA was also visually represented in the scatter plots shown in Figs. 2, 3, and 4.

Table 3.

Level of categorical agreement between the proposed agar dilution methods and the reference broth microdilution method.

| Antimicrobial agent | Number of isolatesa | Total no. of isolates tested by both methodsb | Total no. of isolates with agreement | % Agreement between BMD and AD | Cohen’s kappac | Gwet’s AC1d (Chance-corrected agreement) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT by both BMD and AD |

WT by BMD but NWT by AD | NWT by BMD but WT by AD | NWT by both BMD and AD |

||||||

| Ciprofloxacin | |||||||||

| Aerobic, 24hr [AAD24] | 328 | 2 | 2 | 83 | 415 | 411 | 99.03 | 0.9993 | 0.9997 |

| Aerobic, 48hr [AAD48] | 311 | 18 | 5 | 80 | 414 | 391 | 94.44 | 0.9024 | 0.9503 |

| Microaerobic, 48hr [MAD48] | 299 | 29 | 8 | 77 | 413 | 376 | 91.04 | 0.8248 | 0.9064 |

| Erythromycin | |||||||||

| Aerobic, 24hr [AAD24] | 412 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 414 | 412 | 99.52 | N/A* | 1.0000 |

| Aerobic, 48hr [AAD48] | 410 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 414 | 410 | 99.03 | N/A* | 0.9999 |

| Microaerobic, 48hr [MAD48] | 382 | 32 | 0 | 0 | 414 | 382 | 92.27 | N/A* | 0.9464 |

| Gentamicin | |||||||||

| Aerobic, 24hr [AAD24] | 410 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 415 | 412 | 99.28 | 0.9218 | 0.9998 |

| Aerobic, 48hr [AAD48] | 408 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 414 | 411 | 99.27 | 0.9575 | 0.9998 |

| Microaerobic, 48hr [MAD48] | 315 | 95 | 2 | 3 | 415 | 318 | 76.63 | 0.0881 | 0.7650 |

| Tetracycline | |||||||||

| Aerobic, 24hr [AAD24] | 406 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 414 | 410 | 99.03 | 0.9729 | 0.9998 |

| Aerobic, 48hr [AAD48] | 404 | 2 | 7 | 1 | 414 | 405 | 97.83 | 0.4806 | 0.9924 |

| Microaerobic, 48hr [MAD48] | 407 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 414 | 414 | 100.00 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 |

aWT is the isolates classified as wild type; NWT are isolates classified as non-wild type. BMD is the reference broth microdilution method; AD is the proposed agar dilution method. WT and NWT classifications were assigned according to the proposed ECOFF values: ciprofloxacin (WT ≤ 0.5 µg/ml); erythromycin (WT ≤ 16 µg/ml); gentamicin (WT ≤ 2 µg/ml); and tetracycline (WT ≤ 16 µg/ml). Isolates with MICs above these thresholds were considered NWT.

bThe total number of isolates tested was not equal due to a lack of growth after several attempts.

cInterpretation criteria of kappa are as follows: 0–0.20 Poor; 0.21–0.40 Fair; 0.41–0.60 Moderate; 0.61–0.80 Good; 0.81–1.00 Very Good24.

dGwet’s AC1 does not apply the same interpretative criteria as kappa and instead is based on the relative values scored between the methods.

*Cohen’s kappa values could not be calculated due to highly imbalanced datasets with zero prevalence of non-wild type isolates.

Table 4.

Essential agreement between the proposed agar dilution methods and the reference broth microdilution method.

| Antimicrobial agent | No. of isolates within ± 1 dilution of reference BMDa | No. of isolates within ± 2 dilutions of reference BMD |

Total no. of isolates testedb | Essential agreement (%) within a ± 1-dilution range |

Essential agreement (%) within a ± 2-dilution range |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ciprofloxacin | |||||

| Aerobic, 24hr [AAD24] | 392 | 403 | 415 | 94.46 | 97.11 |

| Aerobic, 48hr [AAD48] | 394 | 404 | 414 | 95.17 | 97.58 |

| Microaerobic, 48hr [MAD48] | 220 | 328 | 413 | 53.27 | 79.42 |

| Erythromycin | |||||

| Aerobic, 24hr [AAD24] | 396 | 407 | 414 | 95.65 | 98.31 |

| Aerobic, 48hr [AAD48] | 389 | 406 | 414 | 93.96 | 98.07 |

| Microaerobic, 48hr [MAD48] | 222 | 349 | 414 | 53.62 | 84.30 |

| Gentamicin | |||||

| Aerobic, 24hr [AAD24] | 344 | 406 | 415 | 82.89 | 98.31 |

| Aerobic, 48hr [AAD48] | 343 | 405 | 414 | 82.85 | 98.07 |

| Microaerobic, 48hr [MAD48] | 21 | 128 | 415 | 5.06 | 84.30 |

| Tetracycline | |||||

| Aerobic, 24hr [AAD24] | 323 | 409 | 414 | 78.02 | 98.79 |

| Aerobic, 48hr [AAD48] | 373 | 412 | 414 | 90.10 | 99.52 |

| Microaerobic, 48hr [MAD48] | 220 | 361 | 414 | 53.14 | 87.20 |

aBMD is the reference broth microdilution method.

bThe total number of isolates tested was not equal due to a lack of growth after several attempts.

Fig. 2.

Scatter plot for the reference broth microdilution method (BMD) compared to the agar dilution method under aerobic conditions for 24 hours (AAD24). A, B are the number of isolates classified as wild type (WT) or non-wild type (NWT) by both AAD24 and BMD, respectively; C is the number of isolates classified as WT by BMD and NWT by AAD24; D is the number of isolates classified as NWT by BMD and WT by AAD24.

Fig. 3.

Scatter plot for the reference broth microdilution method (BMD) compared to the agar dilution method under aerobic conditions for 48 hours (AAD48). A, B are the number of isolates classified as wild type (WT) or non-wild type (NWT) by both AAD48 and BMD, respectively; C is the number of isolates classified as WT by BMD and NWT by AAD48; D is the number of isolates classified as NWT by BMD and WT by AAD48.

Fig. 4.

Scatter plot for the reference broth microdilution method (BMD) compared to the agar dilution method under microaerobic conditions for 48 hours (MAD48). A, B are the number of isolates classified as wild type (WT) or non-wild type (NWT) by both MAD48 and BMD, respectively; C is the number of isolates classified as WT by BMD and NWT by MAD48; D is the number of isolates classified as NWT by BMD and WT by MAD48.

For most antimicrobial agents, kappa values indicated a very good agreement (k > 0.80) between the agar dilution method, especially AAD24 and AAD48, and the reference BMD method. In general, the MAD48 method showed lower agreement by kappa for most antimicrobial agents, except for tetracycline, which demonstrated perfect agreement (k = 1.000). The lowest kappa values were observed for gentamicin with MAD48 (k = 0.0881) and tetracycline with AAD48 (k = 0.4806), indicating poor to moderate agreement despite relatively high percent agreement between the methods (Table 3). Furthermore, kappa values could not be calculated for erythromycin due to highly imbalanced datasets, where the number of non-wild type isolates was 0.

In this study, Gwet’s AC1 values remained consistently high across most of the tested methods, indicating strong agreement even in cases where Cohen’s kappa suggested lower reliability (Table 3). Extremely high AC1 values (0.9997–1.0000) were observed for all antimicrobial agents tested using the AAD24 method, followed by the AAD48 method (0.9503–0.9999). Interestingly, the MAD48 method showed more variable AC1 values, ranging from 0.7650 for gentamicin to 1.0000 for tetracycline. These findings, along with the kappa values, suggest that the AAD24 method demonstrated the highest level of agreement with the reference BMD method.

In addition to CA, EA between the different agar dilution methods and the reference BMD method was also evaluated, as shown in Table 4. For ciprofloxacin and erythromycin, EA within ± 1 doubling dilution was high (over 90%) under both AAD24 and AAD48 methods, while a noticeably lower EA (around 53%) was observed under the MAD48 method. In comparison, gentamicin showed lower EA across all methods. Although EA for gentamicin was approximately 83% under both AAD24 and AAD48 methods, it dropped significantly to about 5% under the MAD48 method. For tetracycline, EA varied between methods. It was about 78% under AAD24, 90% under AAD48, and 53% under MAD48. When the variation was extended to ± 2 doubling dilutions, it was found that EA for all antimicrobial agents tested in this study increased to over 97% under AAD24 and AAD48, and to nearly 80% or higher under MAD48. Overall, EA was consistently higher under aerobic conditions and improved across all antibiotics when the ± 2-dilution margin was applied, further supporting the CA results.

Discussion

This study evaluated the agar dilution method as a practical and reliable alternative to the broth microdilution method for AST of A. butzleri. Our findings support the use of agar dilution, particularly under aerobic conditions at 37 °C for 24 h, where it demonstrated very good agreement with the reference BMD method. This high level of concordance suggests that agar dilution can serve as a dependable method for generating accurate AST results while being more accessible for routine application. In addition, the tentative ECOFFs proposed in this study (0.5 µg/ml for ciprofloxacin, 16 µg/ml for erythromycin, 2 µg/ml for gentamicin, and 16 µg/ml for tetracycline) provide a valuable preliminary framework for classifying wild type and non-wild type A. butzleri isolates. Establishing such species-specific interpretive thresholds is essential for enhancing the consistency and accuracy of AST results and thereby strengthening AMR surveillance.

The tentative ECOFF values in this study were determined based on a compilation of MIC distributions found in our study and from previous publications. Our MIC distributions for ciprofloxacin and tetracycline were largely consistent with those reported in earlier studies5–8,15–18, with mode values differing by no more than a single dilution step from the most common modes, 0.125 µg/ml for ciprofloxacin and 2 µg/ml for tetracycline (refer to Tables S1, S4). Such minor variations are generally acceptable, as a one dilution step difference in MIC values is considered an inherent limitation of susceptibility testing methods8. Most of the compiled studies for erythromycin also showed comparable distributions; however, several exhibited mode values that deviated by two or more dilution steps from the most common mode (2 µg/ml) and therefore did not meet the inclusion criteria outlined by EUCAST (refer to Table S2). Whether these discrepancies arose from differences in testing methodologies or variability of isolates remains uncertain. In the case of gentamicin, a substantial number of MIC distributions, particularly those generated under microaerobic conditions (refer to Table S3), had to be excluded due to their significant deviation from the most common mode (0.25 µg/ml). Aminoglycosides require an oxygen-dependent electron transport chain for active transport into bacterial cells26. Therefore, it is no surprise that the MIC distributions of those under microaerobic conditions showed higher modes than those under aerobic conditions.

Clinical breakpoints (CBPs) and ECOFFs established for C. jejuni and C. coli have frequently been applied to assess antimicrobial resistance in Arcobacter spp. However, increasing evidence suggests that this practice may compromise the accuracy of susceptibility interpretations. Riesenberg et al. (2017)8 demonstrated significant differences in MIC distributions between Campylobacter and Arcobacter, particularly for antimicrobials such as erythromycin and tetracycline, thereby highlighting the limitations of applying Campylobacter thresholds to A. butzleri. To address this gap, the present study aimed to propose tentative ECOFF values specific to A. butzleri for use in AMR surveillance. When compared with the current breakpoints of Campylobacter spp. published in EUCAST27 and EFSA28 documents, the tentative ECOFF values determined in this study for ciprofloxacin (0.5 µg/ml) and gentamicin (2 µg/ml) aligned with the established thresholds for C. jejuni and C. coli, while substantially higher values were observed for erythromycin and tetracycline. Specifically, the proposed ECOFF for erythromycin was 16 µg/ml, which is markedly higher than the current ECOFFs and clinical breakpoints for C. jejuni (4 µg/ml) and C. coli (8 µg/ml). Similarly, the proposed ECOFF for tetracycline was established at 16 µg/ml, compared to the significantly lower values reported for Campylobacter spp. (1–2 µg/ml). Jehanne et al. (2022)29 also strongly discouraged the use of C. jejuni and C. coli cutoffs as it may lead to misclassification of wild type isolates as non-wild type, even when MIC distributions clearly show only a unimodal peak, suggesting that there is supposedly no acquired resistance among the isolates. These findings underscore the need to establish Arcobacter-specific interpretive criteria to enhance the accuracy and consistency of antimicrobial susceptibility assessments for this emerging pathogen.

Gwet’s first-order agreement coefficient, called “Gwet’s AC1”, was calculated and presented alongside Cohen’s kappa, as recommended in cases where high observed agreement may result in paradoxically low kappa values30. Unlike kappa, Gwet’s AC1 is less sensitive to imbalanced datasets, such as those encountered in this study, particularly in the case of erythromycin, for which kappa could not be calculated. In our study, Gwet’s AC1 demonstrated greater consistency with the observed percent agreement between the proposed agar dilution methods and the reference BMD method than Cohen’s kappa. However, it is important to note that Gwet’s AC1 should not be used as a substitute for kappa but rather as a complementary measure, and the interpretive criteria used for kappa also should not be applied to AC1 values31.

The strong agreement observed between the proposed agar dilution methods and the reference BMD method supports the reliability of the agar dilution method under aerobic conditions at 24 hours (AAD24). Although the agar dilution method under aerobic conditions at 48 hours (AAD48) also demonstrated relatively strong agreement with the reference BMD method, its application should be considered due to the extended incubation time, which delays result turnaround and may not be ideal for routine surveillance. Nevertheless, AAD48 may serve as a viable alternative in cases where Arcobacter spp. exhibit poor or no growth after 24 hours, as previous studies have extended the incubation period up to 72 h32. The lowest level of agreement was observed for MAD48 when testing gentamicin, followed by ciprofloxacin and erythromycin. The discrepancies, particularly in the case of gentamicin, may be attributed to reduced antimicrobial efficacy under microaerobic conditions compared to aerobic conditions, where oxygen availability influences the antibacterial activity of certain drugs. Higher oxygen concentrations have been shown to lower MIC values33. These findings are consistent with the previous study reporting increased MIC values or reduced inhibition zones for gentamicin under microaerobic conditions34. However, testing conditions (i.e., aerobic vs. microaerobic) appeared to have minimal impact on the antimicrobial activity of tetracycline compared to the other antibiotics. This may be explained by the chemical properties of tetracycline, which enter bacterial cells via passive diffusion and an energy-dependent process35, mechanisms that do not strictly depend on oxygen levels, unlike those of aminoglycosides. Despite the perfect CA for tetracycline under the MAD48 method, the EA was significantly lower compared to the AAD24 and AAD48 methods. This suggests that testing A. butzleri against tetracycline under aerobic conditions for 24 hours may be preferable to the method derived from Campylobacter AST. Additionally, Arcobacter grows optimally at 30–37 °C and may not tolerate higher temperatures such as the 42 °C used for Campylobacter, further supporting the need for tailored testing conditions for A. butzleri. The observed discrepancies indicate that AST methods developed for Campylobacter spp. may not be directly applicable to Arcobacter spp. Moreover, unlike MAD48, both AAD24 and AAD48 do not require gas packs to create microaerobic conditions, making them more cost-effective alternatives for susceptibility testing of A. butzleri.

Higher EA values observed under aerobic conditions (AAD24 and AAD48), particularly when using a ± 2-dilution range, are consistent with the overall findings of this study. While ± 1 doubling dilution is the conventional standard for determining EA, CLSI guidelines36 acknowledge that drug-organism combinations involving fastidious or infrequently isolated bacteria may require broader performance criteria in the absence of established interpretive breakpoints. Furthermore, Jorgensen et al. (2004)37 also highlighted the need for flexibility in MIC interpretation for rare organisms, supporting the evaluation of EA using a ± 2-doubling dilution range, as a ± 1-dilution range may underestimate true agreement.

Several limitations of this study may affect the interpretation and generalizability of the findings. For example, the inclusion of a reference strain of A. butzleri would have added value to the method validation, specifically tailored to this species. Additionally, the absence of molecular characterization limits the ability to define ECOFFs with greater accuracy and confidence, particularly for erythromycin, where the number of non-wild type isolates was insufficient compared to ciprofloxacin, which showed a more clearly defined non-wild type population. Furthermore, although the strain collection used in this study included A. butzleri isolates from various sources, most of the isolates were poultry-derived. Incorporating more recent isolates from a broader range of sources would enhance the representativeness and applicability of future analyses involving this microorganism.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that the agar dilution method is a practical and relatively reliable alternative to the reference BMD method for AST of A. butzleri. Its suitability for processing larger sample sizes and reduced reliance on specialized equipment make it particularly advantageous for laboratories with limited resources. The tentative ECOFF values proposed for ciprofloxacin, erythromycin, gentamicin, and tetracycline represent a significant step toward the establishment of Arcobacter-specific interpretive criteria, addressing the limitations of applying Campylobacter breakpoints to this distinct genus. Identifying testing conditions that are both effective and resource-conscious contributes to ongoing efforts to standardise AST protocols for A. butzleri, an emerging pathogen of increasing zoonotic relevance.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

This project was supported by the National Research Council of Thailand (NRCT) Project ID N42A660897. Myzatul Hanis Zahiyah Yusof is a recipient of Chulalongkorn University’s Graduate Scholarship Program for ASEAN or Non-ASEAN countries.

Author contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: T.L. and N.J.; Performed the experiments: M.H.Z.Y. and N.J.; Analyzed and interpreted the data: M.H.Z.Y., N.J., and T.L.; Wrote and revised the manuscript: M.H.Z.Y. and T.L.; Supervised and acquired funding for the project: T.L. All authors reviewed and approved the manuscript.

Funding

This project was supported by the National Research Council of Thailand (NRCT) Project ID N42A660897.

Data availability

An Excel file containing the raw MIC data of A. butzleri isolates tested in this study is provided as supplementary material.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Lameei, A., Rahimi, E., Shakerian, A. & Momtaz, H. Genotyping, antibiotic resistance and prevalence of Arcobacter species in milk and dairy products. Vet. Med. Sci.8, 1841–1849 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vandamme, P. et al. Revision of Campylobacter, Helicobacter, and Wolinella taxonomy: emendation of generic descriptions and proposal of Arcobacter gen. nov. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol.41, 88–103 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Perez-Cataluna, A. et al. Revisiting the taxonomy of the genus Arcobacter: getting order from the chaos. Front. Microbiol.9, 2077 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4., S. L. W. On, Miller, W. G., Biggs, P. J., Cornelius, A. J. & Vandamme, P. Aliarcobacter, Halarcobacter, Malaciobacter, Pseudarcobacter and Poseidonibacter are later synonyms of Arcobacter: transfer of Poseidonibacter parvus, Poseidonibacter antarcticus, ‘Halarcobacter arenosus’, and ‘Aliarcobacter vitoriensis’ to Arcobacter as Arcobacter parvus comb. nov., Arcobacter antarcticus comb. nov., Arcobacter arenosus comb. nov. and Arcobacter vitoriensis comb. nov. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol.7110.1099/ijsem.0.005133 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Van den Abeele, A. M., Vogelaers, D., Vanlaere, E. & Houf, K. Antimicrobial susceptibility testing of Arcobacter butzleri and Arcobacter cryaerophilus strains isolated from Belgian patients. J. Antimicrob. Chemother.71, 1241–1244 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Houf, K. et al. Antimicrobial susceptibility patterns of Arcobacter butzleri and Arcobacter cryaerophilus strains isolated from humans and broilers. Microb. Drug Resist.10, 243–247 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ferreira, S., Oleastro, M. & Domingues, F. C. Occurrence, genetic diversity and antibiotic resistance of Arcobacter sp. in a dairy plant. J. Appl. Microbiol.123, 1019–1026 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Riesenberg, A. et al. Antimicrobial susceptibility testing of Arcobacter butzleri: development and application of a new protocol for broth microdilution. J. Antimicrob. Chemother.72, 2769–2774 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dekker, D. et al. Fluoroquinolone-resistant Salmonella enterica, Campylobacter spp., and Arcobacter butzleri from local and imported poultry meat in Kumasi, Ghana. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 16, 352–358 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Jribi, H. et al. Occurrence and antibiotic resistance of Arcobacter species isolates from poultry in Tunisia. J. Food Prot.83, 2080–2086 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Golus, J., Sawicki, R., Widelski, J. & Ginalska, G. The agar microdilution method - a new method for antimicrobial susceptibility testing for essential oils and plant extracts. J. Appl. Microbiol.121, 1291–1299 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Douidah, L., De Zutter, L., Vandamme, P. & Houf, K. Identification of five human and mammal associated Arcobacter species by a novel multiplex-PCR assay. J. Microbiol. Methods. 80, 281–286 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing; Twenty-fifth informational supplement. CLSI document M100-S25. (2015).

- 14.Collado, L. & Figueras, M. J. Taxonomy, epidemiology, and clinical relevance of the genus Arcobacter. Clin. Microbiol. Rev.24, 174–192 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bruckner, V. et al. Prevalence and antimicrobial susceptibility of Arcobacter species in human stool samples derived from out- and inpatients: the prospective German Arcobacter prevalence study arcopath. Gut Pathog. 12, 21 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Uljanovas, D. et al. Prevalence, antimicrobial susceptibility and virulence gene profiles of Arcobacter species isolated from human stool samples, foods of animal origin, ready-to-eat salad mixes and environmental water. Gut Pathog. 13, 76 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Phasipol, P. Occurence, antibiotic resistance, and genetic profiles of Arcobacter isolated from chicken carcasses in Bangkok. MSc Thesis. Chulalongkorn University (2012).

- 18.Ma, Y. et al. Genetic characteristics, antimicrobial resistance, and prevalence of Arcobacter spp. isolated from various sources in Shenzhen, China. Front. Microbiol.13, 1004224 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST). MIC distributions and epidemiological cut-off value (ECOFF) setting. EUCAST SOP 10.0; (2017). http://www.eucast.org/

- 20.Delma, F. Z., Melchers, W. J. G., Verweij, P. E. & Buil, J. B. Wild-type MIC distributions and epidemiological cutoff values for 5-flucytosine and Candida species as determined by EUCAST broth microdilution. JAC Antimicrob. Resist.6, dlae153 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Turnidge, J., Kalhmeter, G. & Kronvall, G. Statistical characterisation of bacterial wild-type MIC value distributions and the determination of epidemiological cut-off values. Clin. Microbiol. Infect.12, 418–425 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gwet, K. L. Computing inter-rater reliability and its variance in the presence of high agreement. Br. J. Math. Stat. Psychol.61, 29–48 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Landis, J. R. & Koch, G. G. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics33, 159–174 (1977). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). Methods for Antimicrobial Dilution and Disk Susceptibility Testing of Infrequently Isolated or Fastidious Bacteria; Approved Guideline—Third Edition. CLSI document M45-A3. (2016).

- 25.Kahlmeter, G. & Turnidge, J. How to: ECOFFs-the why, the how, and the don’ts of EUCAST epidemiological cutoff values. Clin. Microbiol. Infect.28, 952–954 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chaves, B. J. & Tadi, P. StatPearls; (2025). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK557550/

- 27.European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST). Breakpoint tables for interpretation of MICs and zone diameters. Version 15.0. (2025).

- 28.European Food Safety Authority (EFSA). Technical specifications on harmonised monitoring of antimicrobial resistance in zoonotic and indicator bacteria from food-producing animals and food. EFSA J.17, e05709 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jehanne, Q., Benejat, L., Ducournau, A., Bessede, E. & Lehours, P. Molecular cut-off values for Aliarcobacter butzleri susceptibility testing. Microbiol. Spectr.10, e0100322 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wongpakaran, N., Wongpakaran, T., Wedding, D. & Gwet, K. L. A comparison of cohen’s kappa and gwet’s AC1 when calculating inter-rater reliability coefficients: a study conducted with personality disorder samples. BMC Med. Res. Methodol.13, 61 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tan, K. S., Yeh, Y. C., Adusumilli, P. S. & Travis, W. D. Quantifying interrater agreement and reliability between thoracic pathologists: Paradoxical behavior of cohen’s kappa in the presence of a high prevalence of the histopathologic feature in lung cancer. JTO Clin. Res. Rep.5, 100618 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fanelli, F. et al. Genomic characterization of Arcobacter butzleri isolated from shellfish: Novel insight into antibiotic resistance and virulence determinants. Front. Microbiol.10, 670 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Goswami, M., Mangoli, S. H. & Jawali, N. Involvement of reactive oxygen species in the action of ciprofloxacin against Escherichia coli. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother.50, 949–954 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reynolds, A. V., Hamilton-Miller, J. M. & Brumfitt, W. Diminished effect of gentamicin under anaerobic or hypercapnic conditions. Lancet1, 447–449 (1976). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Smith, M. C. & Chopra, I. Energetics of tetracycline transport into Escherichia coli. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother.25, 446–449 (1984). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). Development of In Vitro Susceptibility Testing Criteria and Quality Control Parameters; Approved Guideline—Fourth Edition. CLSI document M23-A4. (2015).

- 37.Jorgensen, J. H., Hindler, J. F., Reller, L. B. & Weinstein, M. P. New consensus guidelines from the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute for antimicrobial susceptibility testing of infrequently isolated or fastidious bacteria. Clin. Infect. Dis.44, 280–286 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

An Excel file containing the raw MIC data of A. butzleri isolates tested in this study is provided as supplementary material.