Abstract

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is the most common group of metabolic disorders in the world, characterized by hyperglycemia that leads to severe short-term complications such as ketoacidosis, hyperosmolar hyperglycemic coma, and long-term microvascular complications that affect the eye, kidney, and nerves. Type 2 diabetes occurs due to resistance to insulin. AMPK (adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase) is an energy radar that controls various metabolic and physiological processes. It is dysregulated in major chronic diseases, such as diabetes. The focus of this review is on understanding the role of AMPK in type 2 diabetes mellitus, which helps ameliorate hyperglycemia and its complications. Medications for T2DM are designed to upregulate the AMPK signaling pathway to improve its microvascular and macrovascular complications. AMPK signaling interacts with PGC-1, PI3K/Akt, NOX4, NF-κB, and other molecular pathways to produce such protective effects. Thus, AMPK is emerging as one of the most auspicious targets for both the prevention and treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Hence, this review focuses on the recent evidence of the role of AMPK signaling in type 2 diabetes mellitus pathogenesis and how to circumvent its complications.

Keywords: Type 2 diabetes mellitus, AMPK signaling, Insulin resistance, Pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes mellitus, Diabetic complications

1. Introduction

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is the most common group of metabolic disorders in the world, which is characterized by the presence of chronic hyperglycemia resulting from a variety of factors, including environmental and genetic alterations [1]. According to the International Diabetes Federation (IDF) 2021, around 537 million adults (20–79 years) worldwide have diabetes. By the years 2030 and 2045, this number is expected to rise to 643 million and 783 million, respectively [2]. Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) represents a significant global public health issue, responsible for approximately 90–95 % of all cases of diabetes mellitus [3]. The common causes might be due to inappropriate lifestyle modifications, such as excessive body weight and insufficient exercise [4,5]. The chronic hyperglycemia of T2DM is associated with many severe short-term complications, including diabetic ketoacidosis, nonketotic hyperosmolar coma, or death if not treated at an early stage [6]. The long-term microvascular complications affect the eyes, kidneys, and nerves, as well as increasing the risk for cardiovascular disease (CVD) [7,8]. A clear understanding of the pathogenesis of T2DM is crucial for the successful prevention, treatment, and management of the disease and its complications [9]. Therefore, prioritizing the management and treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is essential to enhance quality of life and prevent the onset of complications and harmful effects on major organs of the body [10] (see Table 1, Table 2).

Table 1.

Summarizing some natural products that activate the AMPK pathway for T2DM treatment.

| No | Natural Products | Source/Origin | Mechanism of Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Berberine | Plants like Berberis vulgaris | Directly activates AMPK by modulating the AMP/ATP ratio and inhibits mitochondrial respiration. |

| 2 | Resveratrol | Grapes and red wine | Inhibits the mitochondrial F1 ATPase, increasing AMP levels and thereby activating AMPK. |

| 3 | Quercetin | Found in many plants | Indirectly activates AMPK by modulating cellular ADP/AMP levels and directly activates the pathway. |

| 4 | Curcumin | Curcuma longa (Turmeric) | Enhances the body's response to insulin, lowers blood sugar, and has anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties. |

| 5 | Cinnamon | Various species of the Cinnamomum genus | Promotes insulin sensitivity and helps lower blood glucose levels. |

| 6 | Bitter Melon (Momordica charantia) | Tropical vine | Contains compounds that mimic insulin and reduce blood glucose levels. |

| 7 | Ginseng (Panax ginseng) | Various species of the ginseng genus | Improves glucose metabolism and insulin sensitivity. |

Table 2.

Summarizing some of the synthetic products for AMPK activation in T2DM treatment.

| No | Compound | Mechanism of Action | Clinical Use and Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Metformin | Indirectly activates AMPK by inhibiting mitochondrial function, which increases the AMP/ATP ratio. | A first-line antidiabetic drug used to reduce hepatic glucose production and enhance peripheral insulin sensitivity. |

| 2 | Thienopyridone (A-769662) | By directly binding to the β-subunit of AMPK to allosterically activate it. | Investigated as a direct activator of AMPK. |

| 3 | Salicylates | Activate AMPK by direct binding. | Salicylate is the active breakdown product of aspirin. |

Molecular pathways play an important role in the development of T2DM and its new complications. Studies have sought to identify signaling networks and explore their potential as therapeutic targets in the treatment of T2DM [[11], [12], [13]]. Molecular pathways have given researchers fresh insight into how to treat cardiovascular illnesses and hypertension, which are common in people with type 2 diabetes mellitus [14]. According to the previous statements, it is essential to therapeutically target the molecular pathways that are primarily involved in the development of T2DM [15,16]. These include pathways related to insulin resistance, pancreatic beta-cell dysfunction, oxidative stress, and inflammation. Key pathways include those involved in glucose metabolism (such as the hexosamine pathway), insulin signaling (such as PI3K/Akt and AMPK), and those promoting oxidative stress (such as the polyol pathway and AGEs formation).

AMPK is a heterotrimeric serine/threonine protein kinase involving three α, β, and γ subunits [17]. The two subunits of catalytic AMPKα are α1 and α2. The monitoring subunits are β and γ subunits. AMPKβ has also two subunits, including β1 and β2; AMPKγ has three subunits, including γ1, γ2, and γ3 [18]. These many protein isoforms are encoded by seven separate genes, including PRKA1/2, PRKAB1/2, and PRKAG1/2/3 [19,20]. Each subunit has several isoforms, and when combined, they can form one of 12 different heterotrimer configurations with different functions under different physiological conditions [21]. The phosphorylation of Thr172 is induced by at least three upstream kinases: liver kinase B1 (LKB1), calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase kinase 2 (CaMKK2), and TGF-activated kinase 1 (TAK1) [22,23] (Fig. 1). The primary implication of AMPK signaling in T2DM is the reduction of apoptosis, inflammation, and oxidative stress [24,25]. It also promotes glucose uptake, inhibits fatty acid synthesis and promotes fatty acid oxidation, and survival of β cells, and inhibits insulin resistance [26]. The focus of the current review article is on the importance of AMP-activated protein kinases (AMPKs) in T2DM.

Fig. 1.

The structure of AMPK [27]: The structure of AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) is composed of three subunits: a catalytic α subunit and two regulatory subunits, β and γ. This heterotrimeric enzyme functions as a vigorous energy feeler in cellular metabolism. The illustration emphasizes the structural domains of each subunit and the conformational shifts triggered by AMP binding. These changes activate AMPK, enabling it to regulate key metabolic processes such as lipid metabolism and glucose homeostasis.

2. AMPK signaling pathway

The AMPK (AMP-activated protein kinase) is the principal sensor of cellular energy status in all eukaryotic cells and an essential regulator of cellular metabolism in response to metabolic stress and other regulatory signals [28]. After being phosphorylated by LKB1, active AMPK increases catabolic ATP synthesis and inhibits ATP-consuming biosynthetic pathways to replenish intracellular energy levels [29]. Mitochondrial-derived free radicals can activate AMPK via LKB1 without changing the AMP/ATP ratio. The activation of AMPK signaling is triggered by stressful situations and low energy levels [30,31].

There are two ways to activate AMPK: either by binding AMP to AMPK or by upstream kinases phosphorylating threonine 172 (Thr172) or through autocatalytic-mediated phosphorylation. In particular, when AMP binds to the γ-subunit, LKB1, CaMKKβ, or TAK1 can phosphorylate Thr172 inside the activation loop of the α-α-subunit [32]. Metabolic stress can activate AMPK signaling by raising AMP levels and decreasing ATP levels [33]. Increased amounts of AMP and ADP during metabolic stress cause AMPK to be activated by binding to the γ subunit and triggering T172 phosphorylation. The above process of AMPK signaling appears to be fascinating [34]. Protein phosphatases such as PP2A, PP2C, and Ppm1E are endogenous AMPK signaling inhibitors, which can prevent AMPK by dephosphorylating T172 [35].

AMPK signaling activation has a downstream effect that is responsible for phosphorylating a wide variety of proteins within the cell, including AS160, which, when phosphorylated, signals for GLUT4 translocation [36]. AMPK activation enhances mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation (FAO) by regulating the enzyme ACC. Additionally, it activates Carnitine palmitoyltransferase-1B (CPT1B), an enzyme found on the outer mitochondrial membrane, which facilitates the transport of long-chain fatty acyl-CoA into the mitochondria [37]. AMPK suppresses gluconeogenesis mainly by phosphorylating and inhibiting crucial enzymes in the gluconeogenic pathway, including fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase (FBPase-1) and pyruvate carboxylase. Additionally, it affects the expression of transcription factors that regulate gluconeogenesis [38] (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

AMPK signaling activation in cells [35]: The diagram illustrates the activation process of AMPK signaling. AMPK is initiated by an increased AMP/ATP ratio under metabolic stress circumstances. Additional activators of AMPK include LKB1, CaMKKβ, TAK1, and calcium ions. In contrast, the activity of AMPK is downregulated by phosphatases such as PP2A, PP2Cα, and Ppm1E. Once activated, AMPK signaling inhibits the function of mTOR, while promoting cellular processes such as autophagy and the activation of the glucose transporter GLUT4. Collectively, these effects contribute to a decrease in blood glucose concentrations.

3. AMPK in the pathogenesis of T2DM

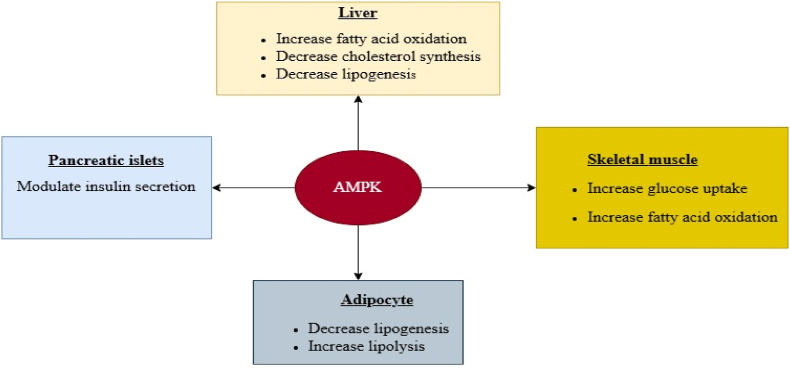

In the study of T2DM and metabolic syndrome, the regulation of AMPK is very important. This is because, increasing evidence indicates that AMPK dysregulation plays a significant role in the onset of insulin resistance (IR) and T2DM. The activation of AMPK either pharmacologically or physiologically can avoid and/or ameliorate some of the pathologies of IR and T2DM [39,40]. AMPK acts as a key regulator by integrating diverse metabolic signals and maintaining energy balance across different tissues. Its activation can positively influence metabolism, especially in the management of conditions such as type 2 diabetes (Fig. 3). There is evidence that AMPK activity is lowered in the skeletal muscle or adipose of people with T2DM. This is supported by the fact that numerous animal models with a metabolic syndrome phenotype have shown decreased AMPK activity in muscle [41,42].

Fig. 3.

Multiple effects of AMPK on the liver, adipose tissue, muscle metabolism, and pancreatic islets [43]:This figure depicts the diverse functions of AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) in controlling metabolic activities in multiple tissues, including the liver, adipose tissue, skeletal muscle, and pancreatic islets. It demonstrates how AMPK activation affects essential metabolic pathways-suppressing cholesterol synthesis in the liver, promoting lipolysis in fat tissue, enhancing glucose uptake in muscle, and modulating insulin secretion in the pancreas. These interconnected mechanisms highlight AMPK’s pivotal role as a central regulator of energy balance and its promise as a therapeutic target for treating metabolic diseases.

3.1. AMPK in obesity and inflammation

Obesity is an increased energy supply relative to the body's energy requirements [44]. The host's adipose tissue stores extra energy, which causes cell growth and functional impairment. Many biologically active chemicals known as adipokines are produced by enlarged fat cells [45]. The proinflammatory adipokine family consists of the adipokines, leptin, resistin, visfatin, retinol-binding protein 4 (RBP4), lipocalin 2, IL-18, angiopoietin 2-like protein (ANGPTL2), chemokine ligand CC2 (CCL2), and ligand chemokine CXC 5 (CXCL5) [46]. FFAs or lipid infusion can cause the proinflammatory response in macrophages and adipose tissue by binding to toll-like receptor 4, which results in IR [47]. Insulin resistance in obesity primarily results from a persistent imbalance where caloric intake surpasses caloric expenditure. In the development of insulin resistance, chronic inflammation triggered by obesity plays a decisive role. Consequently, the recruitment of macrophages to adipose tissue and the activation of pro-inflammatory factors are key mechanisms contributing to insulin resistance [48]. An increase in these factors causes the onset of chronic inflammation, disrupts glucose metabolism, and results in insulin resistance, which are the root causes of type 2 diabetes [49].

Compelling evidence has exposed a negative relationship between obesity/inflammation and AMPK. TNF, a pro-inflammatory cytokine, elevated PP2C expression in skeletal muscles while reducing AMPK phosphorylation, leading to insulin resistance [50]. A new study uncovered that the expression of LKB1 and the phosphorylation of the AMPK α1-subunit, a significant isoform of the AMPK α-subunit, were reduced by LPS, FFAs, and diet-prompted obesity. This designates that AMPK is inhibited through several mechanisms [51].

Additional research recognized that anti-inflammatory stimuli from TGFβ and IL10 activate AMPK in macrophages. Nonetheless, the upstream kinases involved in this activation have not yet been documented [52]. AMPK applies anti-inflammatory properties in immune cells by changing metabolism from glycolysis to mitochondrial oxidative metabolism, such as FAO [47]. Lymphocytes at rest rely on the mitochondria's oxidative metabolism. However, in response to stimulation, these cells switch from oxidative to glycolytic metabolism, which is linked to AMPK suppression and accelerated cell growth. This recognizes that the transition from pro-inflammatory M1 macrophages to anti-inflammatory M2 macrophages depends on AMPK and FAO. These findings suggest that AMPK plays a critical role in reducing inflammation and improving insulin sensitivity by regulating FAO [53].

3.2. AMPK and insulin resistance/sensitivity

Insulin resistance (IR) is a condition in which the body's cells, particularly those in muscles, adipocyte, and the liver become less responsive to insulin (a hormone produced by the pancreas). As cells become resistant to insulin (insulin-insensitive), the pancreatic β cells continue to produce more and more insulin, which raises the blood level of insulin (hyperinsulinemia). Insulin is rapidly secreted by pancreatic beta cells, which then gradually decline [54,55]. Insulin sensitivity refers to the body's cells' ability to respond efficiently to insulin. Higher insulin sensitivity improves glucose uptake, helps maintain lower blood sugar levels, and reduces the risk of developing type 2 diabetes. Engaging in physical activity is a highly effective method for activating AMPK. Regular exercise enhances insulin sensitivity, in part by triggering AMPK activation in skeletal muscle [56]. The main peripheral tissue that impacts glucose absorption and output is skeletal muscle. A protein termed glucose transporter 4 (GLUT4, the primary protein for glucose transport), found in skeletal muscle cells, regulates the rate at which glucose enters and utilized by the cell [57]. Prolonged exposure to superfluous nutrients is known to encourage insulin resistance in skeletal muscle. Since skeletal muscle accounts for about 80 % of insulin-mediated glucose uptake, its insulin resistance plays a vital role in the progression of type 2 diabetes.

An initial study established that mice with muscle-specific AMPKβ1β2 knockout (AMPKβ1β2 MKO) exhibited reduced glucose clearance during exercise, demonstrating that AMPK activation is necessary for enhancing glucose uptake in active skeletal muscle [58]. A recent study has revealed that melatonin improves glucose homeostasis and insulin sensitivity by mitigating inflammation and by increasing cell surface GLUT4 content through the AMPK pathway in mouse model [59].

Animal studies have demonstrated that CPT-1, the rate-limiting enzyme in fatty acid oxidation, can inhibit acetyl-CoA from entering mitochondria and reduce the oxidation of FFAs. This process prevents the uptake and utilization of glucose in skeletal muscles, leading to insulin resistance [60]. Recent research has revealed that AMPK regulates ACC content, lowers coenzyme A concentration, and inhibits CPT-1 to activate CoA decarboxylase via phosphorylation at threonine 79, increasing FFA oxidation and enhancing insulin sensitivity [61]. Likewise, intracerebroventricular berberine injection can alter Malonyl-CoA and the levels of gene expression in the course of fatty acid oxidation [62].

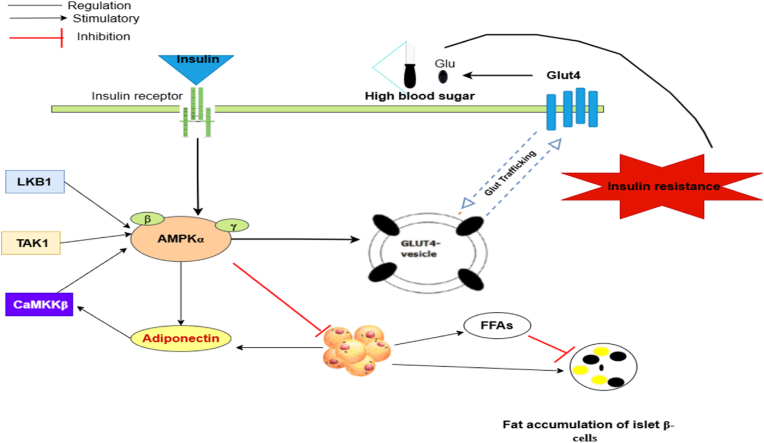

Adiponectin, an endogenous bioactive peptide or protein released by adipocytes, is essential for the development of type 2 diabetes (T2DM) and obesity. Adiponectin synthesis is also lowered when AMPK is blocked. Adiponectin and AMPK are related, and adiponectin released by adipocytes can activate AMPK in both vivo and in vitro through a process including ACC phosphorylation, fatty acid oxidation, glucose uptake, and lactate generation. Furthermore, when AMPK activation is decreased, these effects of adiponectin are suppressed. These findings imply that AMPK may be a potential mediator of adiponectin-stimulated glucose uptake and fatty acid oxidation [63] (Fig. 4). AMPK activation enhances glucose uptake, promotes fatty acid oxidation, reduces inflammation, and improves mitochondrial function, all of which contribute to increased insulin sensitivity. Overall, AMPK positively contributes to IR and relieves and prevents the symptoms of T2DM.

Fig. 4.

Relationships between AMPK and IR [64,65]:This figure demonstrates the sophisticated connections between AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) and IR. It shows that AMPK activation improves insulin sensitivity by stimulating glucose uptake in muscle and limiting excessive lipolysis in adipose tissue. Gaining insight into these interactions is essential for developing effective therapeutic approaches to treat T2DM linked to IR.

3.3. The role of AMPK in increased hepatic glucose synthesis (gluconeogenesis)

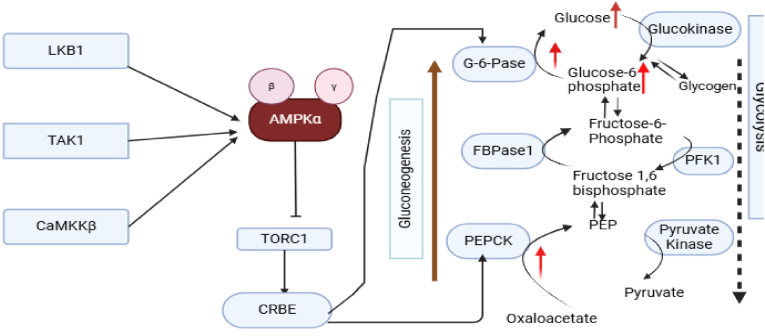

The term "gluconeogenesis" refers to the process of producing glucose or glycogen from non-sugar starting materials such as amino acids, glycerin, and lactic acid. Blood glucose levels are maintained by gluconeogenesis in the liver, and abnormal gluconeogenesis is one of the main factors of T2DM [66]. The molecular mechanism responsible for these effects might be associated with the activation of AMPKα2. AMPK activation can inhibit abnormal glucose metabolism in the liver, reducing glucose production and controlling blood glucose levels [67]. Studies have revealed that hypoglycemic medications used to treat diabetes can reduce the synthesis of glycogen and enhance skeletal muscle glucose uptake. The molecular mechanism underlying these effects may be related to the activation of AMPKα2 [68]. The activation of AMPKα2 may be the biochemical mechanism causing these effects [69]. Upstream kinases can phosphorylate AMPK and impact gluconeogenesis. LKB1 (Liver Kinase B1), a serine/threonine kinase, is out three AMPK kinases that have been revealed. According to research, berberine regulates the LKB1-AMPK-TORC2 signaling pathway, which avoids inappropriate glucose metabolism in the liver. When LKB1 is absent, AMPK activity is lost [[70], [71], [72]].

The main enzymes involved in gluconeogenesis are glucose-6-phosphatase (G-6-Pase), which hydrolyzes phosphate compounds, and phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (PEPCK), a key enzyme composed of a single peptide chain. Both G-6-Pase and PEPCK are downstream targets of AMPK. By regulating these crucial enzymes, AMPK can reduce gluconeogenesis [73]. In addition, one of the transcription factors that regulates the important enzymes G-6-Pase and PEPCK is the cAMP-response element binding protein (CREB), a eukaryotic transcription factor implicated in apoptosis regulation. Activated AMPK inhibits the phosphorylation of CREB and TORC2, thereby reducing the activity of these key gluconeogenic enzymes [74].

Muscle cells develop insulin resistance and cannot absorb glucose in diabetes mellitus. Despite this insulin resistance, rosemary extract has been found to increase glucose uptake by these cells. By encouraging AMPK activation, rosemary extract boosts glucose uptake in muscle cells. AMPK then encourages glucose absorption by increasing levels of glucose transporter 4 (GLUT4) [75]. Another upstream kinase that initiates AMPK is Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinaseβ (CaMKKβ), a serine/threonine protein kinase that is dependent on calcium and calmodulin. CaMKKβ inhibitors can prevent AMPK activation, according to experiments. K+ induction and the generation of Ca2+ influx initiate AMPK activation. Likewise, it has been proposed that CaMKKβ may influence gluconeogenesis by activating AMPK [76] (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

The role of AMPK in gluconeogenesis [78]: This figure demonstrates the central role of AMPK in controlling gluconeogenesis. It outlines how AMPK activation suppresses hepatic glucose production by downregulating crucial enzymes, including phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (PEPCK) and glucose-6-phosphatase.

Furthermore, studies have indicated that a combination of transcription factors downstream of AMPK influences the expression of critical kinases. Additionally, AMPK is reported to play a significant role in the pathogenesis of Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and toxicity to pancreatic β-cells [77]. Based on the evidence presented, AMPK agonists can lower blood sugar levels and inhibit glucose metabolism by influencing crucial kinases both upstream and downstream of the glucose metabolism pathway.

3.4. The role of AMPK and β-cell function

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is defined as the inability of the pancreatic β cell to produce enough insulin to maintain glycemic control due to increased insulin demand caused by insulin resistance. β-cell dysfunction, dedifferentiation, and reduced β-cell mass are also expected to play a key role in the progression of the disease [79]. It is widely acknowledged that hyperglycemia, hyperlipidemia, and inflammation are the three common characteristics of diabetes contribute to β-cell damage and dedifferentiation primarily by promoting endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and oxidative stress. [80]. Several pathways critical to β-cell function and survival have been altered during oxidative stress. Oxidative stress inhibits the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) and activates AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) [81].

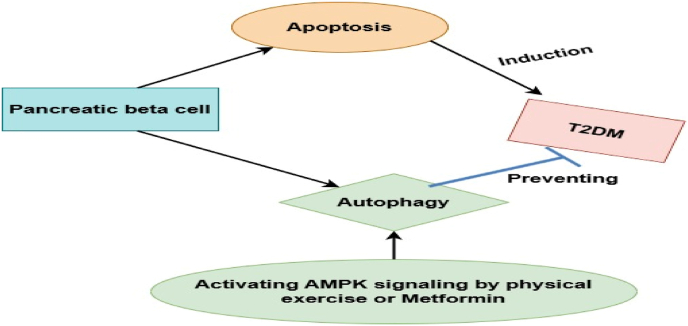

The AMPK pathway regulates insulin secretion, metabolic activities, proliferation, and survival in pancreatic cells [82]. Understanding how AMPK signaling affects cell function and apoptosis is another potential application. For example, AMPK signaling activation increases its ability to reduce lipid synthesis and inhibits apoptosis in cells [83]. Many studies indicated that elevated autophagy functions as a defense mechanism in pancreatic β-cells against oxidative stress [84,85]. Following nitric oxide (NO) exposure, AMPK encourages the functional restoration of β-cell oxidative metabolism and reduces the activation of pathways involved in cell death, such as caspase-3.

For functional maturation, it was crucial that cellular signaling in β-cells fundamentally switched from the nutritional sensor target of rapamycin (mTORC1) to the energy sensor 5′-adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK) [86]. Likewise, the metabolic profile of cells seems to depend on the shift from mTOR to AMPK signaling, and AMPK can trigger mitochondrial biogenesis in cells. The mTORC1 activation and AMPK downregulation contribute to the development of T2DM. It has been demonstrated that oxidative stress changes key pathways vital to cell survival and function. AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) is triggered by oxidative stress. In β-cells, this increased AMPK activity has both protective and harmful effects. First, ROS-mediated AMPK activation in INS-1 cells protects cells by encouraging autophagy and lowering oxidative stress [87] (Fig. 6). While pAMPK participates in mTOR inhibition, which is known to suppress autophagy, the promotion of autophagy under AMPK activation may be mediated through mTOR inhibition [88]. Second, it has been shown that INS-1 cells that lack AMPK lead to the upregulation of genes that are forbidden and are frequently expressed in dedifferentiated β-cells or other tissues, which may help to maintain the identity of mature β cells [89,90].

Fig. 6.

The role of AMPK in autophagy of beta cells [99]: This figure highlights the essential role of AMPK in regulating autophagy in pancreatic beta cells. It illustrates the signaling pathways through which AMPK activation stimulates autophagy, supporting cellular health and preserving beta cell function.

On the other hand, elevated pAMPK brought on by oxidative stress might also be harmful. An extracellular-signal-regulated kinase (p-ERK), which is known to inhibit β-cell proliferation and result in decreased cell mass, was upregulated by ROS in rat cells [91]. Lastly, activation of pAMPK has been demonstrated to have negative consequences on β-cell viability and function over the long term, even though oxidative stress-mediated overexpression of pAMPK may contribute to increase β-cell performance and survival. In a study where AMPKα-2 was persistently activated, mice β-cells displayed suppressed insulin release, decreased basal β-cell activity, and upregulated β-cell-disallowed gene expression [92]. This may indicate that oxidative stress, among other factors, causes the activation of AMPK to be upregulated early in the development of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), acting as a protective mechanism. However, chronic AMPK activation causes damage to cells and eventually leads to a decline in AMPK activation as the disease progresses [93]. Activated AMPK signaling also inhibits mTORC1 signaling. These molecular pathways result in the suppression of ER and mitochondrial stressors to prevent β-cells from apoptosis [94]. Studies supported that the awareness of activating AMPK signaling is imperative for protecting β-cells, preventing their dysfunction, and inhibiting the development of T2DM [[95], [96], [97], [98]].

4. The role of AMPK in diabetic complications

4.1. AMPK and diabetic nephropathy

Diabetic nephropathy (DN) is a common microvascular complication of chronic hyperglycemia and a primary cause of end-stage renal disease [100]. The oxidative stress created by hyperglycemia plays a substantial role in the progression of diabetic nephropathy. This excessive generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) causes mitochondrial dysfunction, significant renal damage, and renal fibrosis [101,191]. Nephropathy in type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) appears to be improved by targeting AMPK signaling. It has been demonstrated that AMPK controls the transcriptional activity of the class O forkhead box (FoxO) signaling pathway to regulate intracellular oxidative balance. The FoxO proteins are a subfamily of transcription factors that promote cell survival and the production of antioxidant enzymes in several tissues [102].

Several studies have linked the inhibition of autophagy in podocytes and proximal tubular cells as a significant contributing factor to the pathogenesis and progression of DN; as a result, focusing on this route to increase autophagy activity may have renoprotective effects on injured renal cells [103,104]. Several lines of research have shown that glomerular epithelial cells in diabetes circumstances have decreased AMPK phosphorylation activity [105,106]. Tuberous sclerosis complex 2, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) coactivator-1 (PGC-1), and Forkhead box O3 (FOXO3) are some of the downstream targets of AMPK that, when phosphorylated by AMPK, improve cellular autophagy, antioxidant defense, and mitochondrial biogenesis in affected cells by inhibiting the mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 [107]. AMPK can phosphorylate ULK1 at Ser317 and Ser377, directly initiating autophagy. Furthermore, it can indirectly encourage autophagy by inhibiting mTORC1. This occurs through the phosphorylation of tuberous sclerosis complex 2 (TSC2) and raptor, a key mTORC1-binding subunit, ultimately releasing ULK1. This mechanism aids to dawdling the progression of DN [108].

In both human kidneys and animal models of type 2 diabetes, Sirt1 expression, and activity were markedly downregulated. A decrease in the phosphorylation of AMPK might be a factor in the process of Sirt1 reduction in the diabetes condition. Recent studies have provided evidence to support this idea, demonstrating that dapagliflozin activates Sirt1 and luteolin activates AMPK/NLRP3/TGF-β Pathway to protect the diabetic kidney through activating AMPK [109,110]. Overall, reducing diabetic nephropathy requires avoiding apoptosis and oxidative stress as well as activating protective autophagy. In diabetic animal models, geniposide reduces albuminuria, podocyte loss, glomerular and tubular damage, inflammation, and fibrosis. It stimulates AMPK signaling to greatly increase ULK1 expression, which then triggers the induction of autophagy to have these protective effects. Furthermore, in the kidneys of diabetic mice, AMPK overexpression inhibits AKT activity to avoid oxidative stress, inflammation, and fibrosis [111].

For T2DM-related obesity, oral hypoglycemic medications like metformin, an indirect AMPK activator, have been suggested as the first line of treatment. Thus, by altering the renal AMPK/ACC system, many researchers have used metformin to prevent HFD-induced renal damage [[112], [113], [114]]. Activation of AMPK regulates the phosphorylation of ACC and consequently the activity of malonyl-CoA. Studies suggested that metabolic disorders such as obesity inhibit AMPK activity, which leads to cellular hypertrophy and matrix accumulation of renal tissue [115,116]. Renal function was enhanced by vitexin therapy which increased renal AMPK activity and decreased ACC activity via the elevation of AMPK phosphorylation levels in vitro renal tubular epithelial cells [117]. Consequently, vitexin, a flavone glycoside derived from fenugreek seed, can be viewed as a promising moiety for further clinical development in the treatment of diabetic nephropathy linked to obesity [118].

4.2. AMPK and diabetic neuropathy

One of the clinical syndromes, Diabetic neuropathy (Dn), is described by discomfort and substantial morbidity predominantly due to a lesion of the somatosensory nervous system [119,120]. Distal symmetrical polyneuropathy (DPN) is the most prevalent form of diabetic neuropathy, which may affect up to 50 % of patients [121,122]. Pathogenesis of Dn is mediated by elevated ROS, amplified apoptosis, loss of insulinotropic support, neuroinflammation, and decreased autophagy [123]. According to reports, people who have had diabetes for at least 25 years are more likely to develop diabetic neuropathy. The development of Dn is caused by several reasons, including changes in metabolism, immunological responses, neurovascular problems, lifestyle choices, and nerve damage [[124], [125], [126]]. DPN is a major risk factor for diabetic foot ulceration, which remains a major cause of morbidity and is the leading cause of non-traumatic amputations [127,190].

DM harms the brain and neurons. Among the main underlying factors contributing to neuropathy in people with diabetes are oxidative stress, inflammation, and apoptosis. It can be beneficial to use therapeutic drugs that target these molecular processes to improve diabetic neuropathy [128]. Reduced AMPK signaling in dorsal root ganglia (DRG) neurons is linked to mitochondrial dysfunction and peripheral neuropathy in diabetic models. To avoid neuronal injury and neuroinflammation, BRB treatment also reinforced the endogenous antioxidant defense mechanisms facilitated by NEF-2-related factor 2 (Nrf2). Following BRB administration, these results led to increased conduction velocity, increased nerve blood flow, and decreased hyperalgesia. BRB contact improved peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1-alpha (PGC-1α) mediated mitochondrial biogenesis in neuronal cells [129].

The onset and development of DPN are significantly influenced by the loss of mitochondrial function linked to peripheral nervous system injury to the AMPK/PGC-1 signal pathway. Activating the AMPK/PGC-1α axis may be conducive to the preservation of mitochondrial function in the peripheral nervous system under hyperglycemia [130]. Hyperglycemia-mediated dysregulation of AMPK/SIRT/Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1-alpha (PGC1α) pathway in diabetic neurons was also shown to induce mitochondrial death, leading to distal axonal cell death, a hallmark feature of diabetic peripheral neuropathy [131]. In the AMPK/Nrf2 metabolic control network, AMPK can activate Nrf2 to regulate oxidative stress [132].

In the ALA experiment, a rat model of diabetic peripheral neuropathy, the expression levels of AMPK, p-AMPK, Nrf2, and p-Nrf2 were elevated in the DRGs of the ALA group, along with the expression levels of downstream molecules NQO1 and HO-1, GSH levels, and MDA levels. These findings imply that ALA may protect DRGs from oxidative stress damage by regulating AMPK and stimulating the Nrf2 endogenous antioxidant pathway that lies downstream of it [133]. The anti-inflammatory properties of AMPK on Dn Metformin-treated rats of diabetes reduced systemic inflammation by inhibiting cytokines. Then activation of AMPK signaling decreased glucose levels, attenuated inflammatory markers (such as IL-6, CRP, and TNF-), increased MNCV of the sciatic nerve, and also improved histopathological scores of sciatic nerves [134]. They also demonstrated that metformin normalized the rise in membrane-associated TRPA1 and mechanical allodynia in db/db mice via activating AMPK [135]. These findings strongly suggest that AMPK should be a target for the treatment of diabetic neuropathy.

4.3. AMPK and diabetic retinopathy

Diabetic retinopathy (DR) is one of the major causes of adult vision loss in developed countries that can affect the peripheral retina, the macula, or both. Nonetheless, the exact pathogenesis mechanism is uncertain [136]. It is divided into two phases: non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy (NPDR) and proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR). The former is primarily caused by inflammation-induced elevated vascular permeability; the latter, an advanced stage, is mainly attributed to increased neovascularization [137]. Pathological processes that occur during DR include impaired retinal blood flow, thickening of the vascular basement membrane, capillary degeneration, damage to the blood-retinal barrier, and glial dysfunction. The significance of AMPK in the pathophysiology of DR has also been confirmed in numerous papers over the past few years. There is evidence linking decreased AMPK activation to impaired intraocular homeostasis and retinal inflammation [138,139]. In several experimental diabetic models, activating AMPK was found to help prevent lipotoxicity, reduce blood flow, visual impairment brought on by inflammation, and retinal apoptosis associated with DR [140,141].

The pathogenesis of various systemic disorders, including diabetic retinopathy, is heavily influenced by inflammation. Inflammation in the diabetic eye triggers vascular hyperpermeability and retinal neovascularization, which are the defining features of DR [142]. It was shown that retinal AMPK downregulation, followed by SIRT1 deactivation and nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-B) activation, was related to retinal inflammation [143]. Inflammation makes the expression of several adhesion molecules, including Vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 (VCAM-1), during DR. Vascular permeability is caused by inflammatory cells adhering to retinal arteries and migrating to the retina as a result of increased expression of VCAM-1 [144]. Hyperglycemia is known to induce apoptosis in retinal cells of neuronal and vascular origin, leading to interruption of the nutritive blood flow, neural dysfunctions, and finally impaired vision [145]. It has been revealed that AICAR's activation of AMPK in retinal pericytes inhibits lipotoxicity-induced apoptosis. To increase retinal blood flow, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) agonists dilate the retinal arterioles, which release nitric oxide (NO) and activate the enzymes soluble guanylate cyclase (sGC) and cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP). These positive effects of the PPAR agonist were demonstrated to be mediated by the AMPK and PI3-Kinase/Akt (Protein Kinase B)/endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) signaling pathways [146].

The metabolism of energy is significantly influenced by mitochondria. The primary trigger of apoptosis in diabetic retinopathy (DR) is mitochondrial damage caused by oxidative stress. AMPK is a key player in the control of diabetes and can regulate autophagy and mitochondrial activity in cells. The structure and function of the retina are affected by altered mitochondrial function in high-glucose environments, which also increases oxidative stress and alters redox equilibrium [147,148]. In the body, normal autophagy regulates the steady-state activity of cells, whereas abnormal autophagy is harmful [149]. Many studies have revealed that abnormal autophagy is the primary pathogenic characteristic of diabetic retinopathy. Studies have shown that this effect may be due to neuronal dysfunction caused by advanced glycation end products (AGEs) [150], which can inhibit autophagy in cells [151]. Increased intraocular pressure and decreased aqueous clearance, which are the crucial steps in the development of DR, were seen in their experiments with AMPK α2 null mice [139]. Activation of the SIRT1/LKB1/AMPK pathway by metformin was shown to suppress “memory” of hyperglycemic stress in diabetic rats by downregulating NF-kB and Bcl2-associated X protein (BAX) expression. In the prevention and treatment of DR, metformin, an agonist of the AMPK pathway, could decrease RPE cell and photoreceptor cell loss [152]. Fig. 7 demonstrates the role of AMPK in diabetic complications (DN, Dn, & DR).

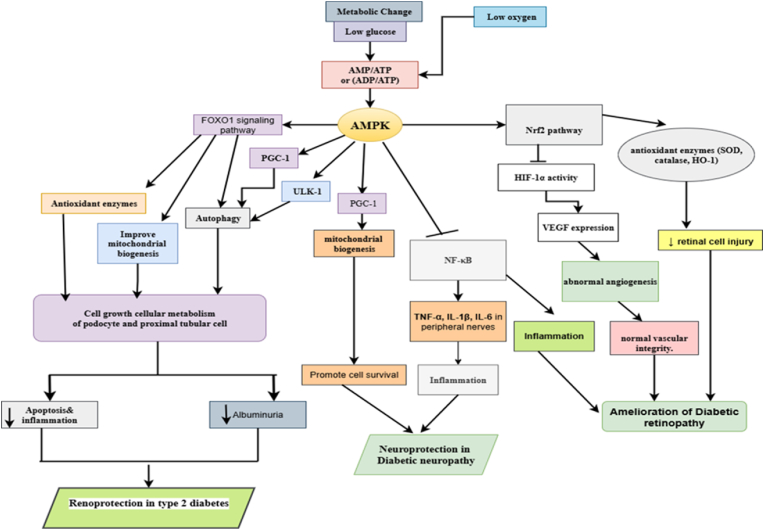

Fig. 7.

The Role of AMPK in Diabetic Complications (DN, Dn, & DR) [153,154]: AMPK acts as a key energy sensor and protective regulator against hyperglycemia-induced metabolic stress that contributes to the development of diabetic complications. In diabetic nephropathy, AMPK activation alleviates renal oxidative damage, restrains messangial cell proliferation, and prevents podocyte loss, thereby maintaining kidney integrity and function. In diabetic neuropathy, AMPK stimulates mitochondrial biogenesis, suppresses neuroinflammation via NF-κB inhibition, ultimately enhancing neuronal survival and peripheral nerve activity. In diabetic retinopathy, AMPK counteracts pathological angiogenesis by reducing VEGF expression, decreases oxidative stress in retinal cells, and improves endothelial health, thereby preserving vision.

5. The role of AMPK in diabetes related metabolic disorders

5.1. AMPK and cardiovascular diseases

Cardiovascular diseases related to diabetes are the primary cause of death in individuals with diabetes, responsible for over 50 % of fatalities [153]. The risk of developing cardiovascular diseases appears to be higher in T2DM, and several mechanisms, including oxidative stress and inflammation, among others, have been found to contribute to heart damage [154,188]. Many pathophysiological factors, including macroangiopathy, microangiopathy, anomalies of metabolism, chronic inflammation, and fibrosis, contribute to diabetic cardiovascular disease (CVD) [155]. Macrovascular complications in diabetes are brought on and exacerbated by mitochondrial dysfunction. A line of evidence suggests that endothelial dysfunction during macrovascular complications is strongly influenced by mitochondrial dynamics [156,157]. Hyperlipidemia and hyperglycemia both affect mitochondrial dynamics by shifting the balance in favor of excessive mitochondrial fission, which results in elevated levels of ROS and impaired ETC [156,158]. The aldose reductase (AR) facilitates oxidative stress and ROS overgeneration, impairing the function of endothelial cells and stimulating the Bax/Bcl-2 ratio and caspase-3 production. Mechanistically, suppressing AR causes SIRT1 to be upregulated to support AMPKα1 phosphorylation, which causes a marked reduction in mTOR phosphorylation [159].

AMPK plays a crucial role in the cardiovascular system, with significant physiological functions in heart cells similar to those in other tissues. Its importance is particularly highlighted under stress conditions such as increased hemodynamic load, myocardial ischemia, and hypoxia, where its activation becomes essential [160]. AMPK plays cardioprotective roles during ischemia by increasing glucose uptake and glucose transporter 4 (GLUT4) translocation, decreasing apoptosis, improving postischemic recovery, and limiting MI [161]. It is helpful to target AMPK signaling in T2DM to reduce cardiomyopathy and cardiac damage. During T2DM, the NLRP3 inflammasome causes injury and inflammation in the heart. Following activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome, levels of IL-1, IL-6, and IL-8 rise, which promotes inflammation [162]. The expression of Nrf2 is increased by AMPK signaling to exhibit its antioxidant action. It is noteworthy that FGF21 acts as an upstream mediator to increase Akt2 expression, which causes GSK-3 to be down-regulated. Then, Fyn expression rises to activate Nrf2 signaling, exerting antioxidant activity and protecting the heart from oxidative injury. AMPK activation by FGF21 inhibits CD36/FATP and stimulates ACC phosphorylation. To prevent lipid accumulation and an increase in fatty acid oxidation, which helps reduce cardiac apoptosis and inflammation, hypertrophy, and fibrosis in the heart [163,193].

Many anti-diabetic medications that target AMPK to affect mitochondrial dynamics may boost endothelial function. AMPK signaling is a suitable choice for treating T2DM because of its antioxidant and lipid-lowering effects. The protective effects of empagliflozin were achieved by inhibiting AMPK-dependent mitochondrial fission [164]. As a result, reducing mitochondrial fission by activating AMPK may be a promising treatment for diabetic patients' macrovascular complications.

5.2. The role of AMPK in non-alcoholic fatty liver diseases

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), a hallmark of metabolic syndromes usually linked to obesity, hyperlipidemia, and type 2 diabetes mellitus, is a rising common problem with a significant health burden in both developed and developing nations [165]. It excludes excessive drinking of alcohol and other specific causes of liver damage and is characterized by diffuse vacuolar fat becoming pathologic [166]. The association between type 2 diabetic mellitus (T2DM) and liver disease is well acknowledged. Yet, the overall prevalence is far higher than would be expected by a coincidence of two extremely common diseases. It can be categorized into three groups: 1) Liver disease linked to diabetes: either brought by diabetes (glycogenic hepatopathy and diabetic hepatosclerosis) or provoked by it (NAFLD/NASH). 2) Diabetes as a consequence of liver disease: Hepatogenous diabetes. 3) Liver disease occurring coincidentally with T2DM: Autoimmune biliary disease and chronic active autoimmune hepatitis. Up to 70–80 % of people with type 2 diabetes and 30–40 % of adults with type 1 diabetes mellitus can develop NAFLD [167,168]. Alike to other tissues, AMPK signaling activation aids in improving injuries in the liver.

Inhibiting AMPK impairs the mitochondria's capacity to oxidize free fatty acids and causes lipid buildup in hepatocytes. Meanwhile, hepatocellular apoptosis is mediated by mitochondrial dysfunction [169]. The basic way to treat hepatic fibrosis is to phosphorylate AMPK, which inhibits the proliferation of hepatic stellate cells [170]. Lipid buildup in hepatic cells is considerably reduced by the Tangshen formula (TSF). TSF averts hepatic steatosis via stimulating AMPK signaling. Then, in vitro and in vivo experiments, AMPK increases SIRT1 expression to induce autophagy and reduce hepatic steatosis in T2DM [171]. By concentrating on a distinct molecular pathway, another experiment supported the protective role of autophagy in reducing diabetic complications. Autophagy is triggered by dapagliflozin to reduce hepatic steatosis. To increase autophagy and decrease mTOR expression, dapagliflozin stimulates AMPK signaling. This decreases liver steatosis and increases hepatic steatosis [172].

Another study found that the Fufang Zhenzhu Tiaozhi formula (FTZ) dramatically increased the expression of AMPK, indicating that the protective effect of FTZ on NASH may be related to its ability to prevent liver steatosis and apoptosis by activating AMPK [173]. Fucoidan increases the activity of antioxidant enzymes such as SOD and catalase in diabetic mice to reduce hepatic oxidative stress. In addition, adiponectin is promoted as an anti-inflammatory factor and lipid peroxidation by fucoidan. Fucoidan's hepatoprotective effects in T2DM are mediated by increasing SIRT1 expression to trigger AMPK signaling, which then downregulates PGC-1 and reduces oxidative stress and inflammation [174]. In addition to reducing the hepatic buildup of triglyceride and total cholesterol in db/db mice, LMWF treatment also decreased plasma levels of alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, total cholesterol, and triglyceride.

It is important to note that T2DM and insulin resistance are risk factors for the onset of NAFLD. According to an experiment, salidroside has been shown to have a protective effect in reducing high-fat-induced NAFLD. Salidroside reduces obesity, modifies fat buildup and glucose levels, and improves insulin sensitivity. Salidroside aids T2DM patients by reducing inflammation and oxidative stress. Salidroside stimulates AMPK signaling to drastically lower the expression of TXNIP and its downstream target, the NLRP3 inflammasome, to have these protective effects [175]. As a result, the interaction of AMPK and molecular pathways and mechanisms contributes to its hepatoprotective impact in T2DM, and the majority of experiments have demonstrated the positive effects of AMPK signaling activation. Fig. 8 exhibits the role of AMPK in cardiovascular diseases and NAFLD.

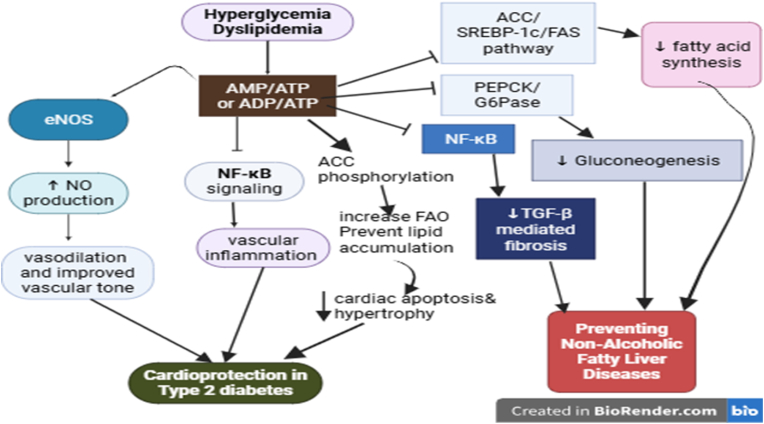

Fig. 8.

The role of AMPK in cardiovascular diseases and NAFLD [178,179]:AMPK acts as a central regulator of cellular energy homeostasis and exerts protective effects in cardiovascular and NAFLD. In cardiovascular diseases, its activation stimulates endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS), promotes vascular relaxation, reduces oxidative stress, and suppresses pro-inflammatory signaling pathways such as NF-κB. AMPK also optimizes cardiac metabolism by enhancing fatty acid oxidation, and preventing lipid accumulation, which collectively protect against cardiac hypertrophy, ischemia-reperfusion injury, and heart failure. In NAFLD, AMPK activation decreases hepatic lipogenesis by downregulating SREBP-1c and ACC, and attenuates inflammatory and fibrotic responses. Overall, AMPK re-establishes metabolic balance, supports mitochondrial health, and reduces oxidative as well as inflammatory stress, thereby slowing the progression of cardiovascular complications and fatty liver disease.

5.3. The role of AMPK in diabetic ischemic stroke

One of the most serious complications of diabetes is ischemic stroke, which has been linked to greater mortality and disability rates. According to data, type 2 diabetes mellitus affects roughly 40 % of patients with cerebral ischemia, and the incidence of ischemic stroke in diabetic patients is much higher (by 2-6-fold) than that in non-diabetic stroke patients [[176], [177], [178]]. Diabetes involves a markedly increased risk for ischemic stroke at all ages [179]. One of the key features of cerebral ischemia in diabetes is that blood vessel injury exacerbates brain damage. The primary recovery mechanisms after a stroke are angiogenesis and remodeling, which show promise for post-stroke treatment by improving oxygen and nutrient delivery to the injured tissue [180].

Many cerebral activities, including synaptic transmission, vesicle recycling, and axonal transport, depend on the proper maintenance of energy levels in brain neurons [181]. The complexity and heterogeneity of diabetic stroke pathology are related to the cellular dysfunction brought on by hyperglycemia. It has been demonstrated that hyperglycemia slows the healing of diabetic wounds by causing vascular endothelial cells to become dysfunctional [182]. It has been identified that the activation of AMPK plays a protective role in ischemic stroke [183]. Changes in AMPK activity are also important for detecting and addressing "cell stress," such as ischemia. Post-stroke treatment with metformin upsurges angiogenesis and neurogenesis and stimulates functional recovery via AMPK activation. The AMPK pathway is also involved in the effects of tPA on neuronal apoptosis and mitophagy following stroke [184]. The AMPK signaling pathway was activated by nmFGF1 therapy, which enhanced glucolipid metabolism and encouraged angiogenesis. These effects benefited, at least in part, functional recovery [185].

6. Current Druggable targets of the AMPK signaling pathway

The AMPK pathway has been recognized as responsible for metformin’s efficiency and effectiveness [187]. In recent times, there has been an immense interest in plant-derived flavonoids as natural activators of AMPK, proposing a promising complementary approach to conventional diabetes treatments [186]. Natural products, characterized by their diverse origins, multifaceted bioactivities, and relative safety, hold considerable promise in modulating the AMPK pathway [192].

To enhance glucose uptake and insulin sensitivity, products resulting from plant sources exhibit diverse mechanisms, including direct or indirect modulation of AMPK activity, (Table 1) which are helpful for managing T2DM [194].

Similarly, synthetic AMPK activators were developed in pre-clinical settings. However, taking these efforts to the clinical stage face multiple challenges due to the potential for off-target effects. Unlike, metformin which exhibits high liver specificity due to its uptake via organic cation transporters (OCTs), many novel AMPK activators demonstrate broader tissue distribution which poses a safety concern [189]. Other than metformin, despite multiple attempts, currently, there are no new drugs approved by FDA using AMPK signaling pathways.

Some synthetic compounds perform by directly binding to the AMPK enzyme or indirectly via modulating cellular energy signaling pathways, thus promoting glucose uptake and ameliorating insulin sensitivity. Those synthetic products which are used to activate the AMPK signaling pathway for the treatment of T2DM include the biguanide metformin, which indirectly activates AMPK by inhibiting mitochondrial function. Also, thienopyridone (A-769662) is a direct AMPK activator. Other synthetic compounds, (Table 2) such as salicylates, bind directly to activate AMPK [195].

Critical analysis reveals that many natural products likely activate AMPK indirectly by disrupting mitochondrial ATP production, leading to higher AMP/ADP ratios, a key trigger for AMPK activation [192].

6.1. Clinical studies

The management of T2DM in clinical course is very important and a variety of antidiabetic drugs have been utilized in this case. In this section, our objective is to provide a dialogue of AMPK signaling targeting for T2DM management in clinical development. Neurological diseases usually occur due to T2DM. The latest clinical trial conducted a test on 80 T2DM patients. These are randomly divided into two groups including metformin group and insulin group. After two weeks of treatment with metformin, neurological indexes were evaluated and it was shown that metformin improves neurological functions scores and alleviates oxidative stress. In order to understand the essential mechanisms responsible for these protective impacts of metformin in T2DM patients, rat model of diabetic patients was produced and metformin was utilized. The results exhibited that metformin stimulates AMPK signaling to reduce mTOR expression and enhances neurological indexes in diabetic rats. Therefore, AMPK/mTOR axis can be considered as underlying pathway responsible for protective effect of metformin in T2DM patients [196]. Another trial focuses on 27 patients including 14 control patients and 13 overweight/obese patients. This study reveals activation of AMPK signaling during exercise in T2DM patients as an adaptation to exercise. Nevertheless, relationship between insulin signaling, AMPK and exercise was not found. In fact, AMPK signaling is essential for adaptation to exercise [197]. Another experiment conducted investigations on 16 T2DM patients, 8 lean subjects and 8 obese patients. Based on the results of this study, T2DM patients should perform exercise in higher intensity compared to lean subjects to activate AMPK signaling [198]. Thus, if physicians are going to endorse exercise as a therapeutic strategy for T2DM patients, they must consider intensity of exercise. Additional experiment tries to reveal AMPK phosphorylation status in healthy and T2DM patients. According to the results of this study, subjects with normal glucose tolerance reveal enhanced AMPK phosphorylation, while these changes do not occur in diabetic patients [199]. Another randomized clinical trial discloses that creatine supplementation is linked with AMPKα upregulation and stimulating glucose uptake in T2DM [200]. Generally, clinical trials highpoint the fact that AMPK owns antidiabetic prospective in T2DM patients and, in near future, novel therapeutics can focus on this pathway.

7. Search strategy and selection criteria

7.1. Search strategy

This review conducted literature searches across several databases, including Scopus, Web of Science, PubMed, SpringerLink, and Science Direct, employing a combination of specific keywords and related terms. Searches were conducted using key terms such as “AMPK,” and “diabetes,” which were further combined with “type 2 diabetes,” “hyperglycemia,” “cardiovascular disease,” “nephropathy,” “neuropathy,” “complications,” and “mechanism.” The searches were limited to only literature published in the English language.

7.2. Selection criteria

References were screened based on their relevance to the topic. Initially, titles of high-value references were quickly reviewed to assess their relevance. This was followed by a title-specific search and, ultimately, a thorough reading of the entire article. Duplicate studies that did not align with the review’s focus were excluded. Criteria for inclusion were conducted in the following manner: studies should center on the AMPK mechanism, diabetes, and its complications, the research must be connected to diabetes, and the studies should explore the role of AMPK in diabetes. Exclusion criteria included: unclear methodologies, research subjects, or mechanisms of action; unreliable or low-quality publications. To ensure the reliability of the selected studies, three researchers (KHT, CDG, THE) independently screened and analyzed all the literature during the review process.

8. Limitations of the study

Due to time and financial constraints, we didn’t analyze the difference in molecular pathways and pathogenesis between T1DM and T2DM. Also, the focus of this review paper is specifically on T2DM.

9. Conclusion

Patients with Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) have high blood glucose levels, or hyperglycemia, which can cause oxidative stress and inflammation in cells and tissues, resulting in organ dysfunction. Among the diabetic complications that lower the quality of life for T2DM patients are neuropathy, nephropathy, retinopathy, and cardiovascular disorders. The activation of AMPK is associated with insulin resistance (IR), gluconeogenesis, autoimmunity of beta cell dysfunction, endoplasmic reticulum stress, and glucose metabolism. Obesity is a risk factor for chronic inflammation, which is a crucial risk factor for modern chronic diseases like insulin resistance, diabetes, and cancer.

We discussed the role of AMPK in diabetic complications to clarify the relevance of AMPK signaling in T2DM. The occurrence of nephropathy, neuropathy, retinopathy, cardiovascular illnesses, and other conditions is considerably reduced by activating AMPK signaling. According to the foregoing discussions, inducing AMPK signaling is the most effective option for lowering insulin resistance, enhancing glucose and lipid metabolism, and alleviating diabetes complications.

10. Future perspective

In recent years, the identification of new drugs for the treatment of diabetes has focused heavily on the AMPK protein. AMPK appears to play a significant role in the pathogenesis of several diabetes-complication diseases. Studying actual AMPK active substances also offers a novel possibility or concept for the development of new drugs. Certain natural medicines or traditional Chinese medicine preparations have been clinically used to treat diabetes. However, their usage is constrained by a lack of adequate definitions of active ingredients, mechanisms of action, and reliable clinical trials based on evidence. New AMPK activators are being developed through research efforts. Nevertheless, some inconsistent results were found in the experiments, and more research is therefore required to better understand the mechanism of action of AMPK in pancreatic β cells under physiological conditions. Also the following points are potential research topics which should be develop in the near future.

-

•

How to reconcile AMPK's tissue-specific effects (beneficial vs detrimental).

The diverse effects of AMPK resolute from context-dependent activation levels, cellular locations, durations, and isoform specificities, which can move its role from beneficial (e.g., acute exercise, transient caloric restriction) to detrimental (e.g., chronic over-activation in Huntington's disease, severe ischemic stroke). Settling these effects involves the understanding of the precise cellular environment, the specific AMPK subunits involved, and the magnitude and persistence of the energy stress that activates it.

-

•

Potential biomarkers of AMPK activity in patients.

Potential biomarkers of AMPK activity in patients include the phosphorylation of AMPK at the Thr172 residue and the mRNA expression levels of key downstream target genes such as GPNMB, and RHOB, which can be measured in human blood cells.

-

•

Barriers to translation from preclinical findings to clinical therapies.

Barriers to translating preclinical findings into clinical therapies are wide-ranging. These includes methodological issues with preclinical models, lack of funding and human capacity, detachment between basic and clinical research cultures, and regulatory hurdles, inadequate. These factors contribute to a low success rate, with many promising therapies failing during development due to safety issues, lack of efficacy in humans, or other unforeseen problems. All the above mentioned topis should be addressed in the future research perspectives.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Kibur Hunie Tesfa: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Chernet Desalegn Gebeyehu: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Software, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Asrat Tadele Ewunetie: Writing – review & editing, Methodology. Endalkachew Gugsa: Writing – review & editing, Methodology. Amare Nigatu Zewdie: Writing – review & editing, Methodology. Gashaw Dessie: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Methodology. Hiwot Tezera Endale: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Methodology.

Ethics approval

Since the publication’s data was taken from previously published articles and not from its own investigations, ethical approval is not necessary.

Data availability

Since this is a review article, no new data was used.

Funding

This study did not receive funding from any governmental or non-governmental sources.

Conflict of interest

We have no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Kibur Hunie Tesfa, Email: kiburtesfa@gmail.com.

Chernet Desalegn Gebeyehu, Email: chernetdesalegn27@gmail.com.

Asrat Tadele Ewunetie, Email: asratt205@gmail.com.

Endalkachew Gugsa, Email: endalkgugsa@gmail.com.

Amare Nigatu Zewdie, Email: nigatuamare297@gmail.com.

Gashaw Dessie, Email: dessiegashaw@yahoo.com.

Hiwot Tezera Endale, Email: hiwottezera1@gmail.com.

Abbreviations

- AMPK

AMP-activated protein kinase

- CVD

Cardiovascular Diseases

- DM

Diabetes Mellitus

- DN

Diabetic Nephropathy

- Dn

Diabetic Neuropathy

- DR

Diabetic Retinopathy

- IR

Insulin Resistance

- NAFLD

Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease

- ROS

Reactive Oxygen Species

- T2DM

Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus

References

- 1.Organization W.H. 2019. Classification of diabetes mellitus. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Magliano D.J., Boyko E.J., Atlas I.D. tenth ed. International Diabetes Federation; 2021. What is diabetes? IDF diabetes atlas. [Internet. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ahmad E., Lim S., Lamptey R., Webb D.R., Davies M.J. Type 2 diabetes. Lancet (London, England) 2022;400:1803–1820. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01655-5. 10365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thomas N.J., Lynam A.L., Hill A.V., Weedon M.N., Shields B.M., Oram R.A., et al. Type 1 diabetes defined by severe insulin deficiency occurs after 30 years of age and is commonly treated as type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2019;62(7):1167–1172. doi: 10.1007/s00125-019-4863-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Collier A., Ghosh S., Hair M., Waugh N. Impact of socioeconomic status and gender on glycaemic control, cardiovascular risk factors and diabetes complications in type 1 and 2 diabetes: a population based analysis from a Scottish region. Diabetes Metabol. 2015;41(2):145–151. doi: 10.1016/j.diabet.2014.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fayfman M., Pasquel F.J., Umpierrez G.E. Management of hyperglycemic crises: diabetic ketoacidosis and hyperglycemic hyperosmolar state. Med Clin. 2017;101(3):587–606. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2016.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Punthakee Z., Goldenberg R., Katz P. Definition, classification and diagnosis of diabetes, prediabetes and metabolic syndrome. Can J Diabetes. 2018;42:S10–S15. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjd.2017.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Das H., Naik B., Behera H., editors. Progress in computing, analytics and networking: proceedings of ICCAN 2017. Springer; 2018. Classification of diabetes mellitus disease (DMD): a data mining (DM) approach. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lu X., Xie Q., Pan X., Zhang R., Zhang X., Peng G., et al. Type 2 diabetes mellitus in adults: pathogenesis, prevention and therapy. Signal Transduct Targeted Ther. 2024;9(1):262. doi: 10.1038/s41392-024-01951-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tan S.Y., Wong J.L.M., Sim Y.J., Wong S.S., Elhassan S.A.M., Tan S.H., et al. Type 1 and 2 diabetes mellitus: a review on current treatment approach and gene therapy as potential intervention. Diabetes Metabol Syndr: Clin Res Rev. 2019;13(1):364–372. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2018.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shati A.A., Alfaifi M.Y. Salidroside protects against diabetes mellitus‐induced kidney injury and renal fibrosis by attenuating TGF‐β1 and Wnt1/3a/β‐catenin signalling. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2020;47(10):1692–1704. doi: 10.1111/1440-1681.13355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rezaeepoor M., Hoseini-Aghdam M., Sheikh V., Eftekharian M.M., Behzad M. Evaluation of interleukin-23 and JAKs/STATs/SOCSs/ROR-γt expression in Type 2 diabetes mellitus patients treated with or without sitagliptin. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2020;40(11):515–523. doi: 10.1089/jir.2020.0113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tu C., Wang L., Tao H., Gu L., Zhu S., Chen X. Expression of miR-409-5p in gestational diabetes mellitus and its relationship with insulin resistance. Exp Ther Med. 2020;20(4):3324–3329. doi: 10.3892/etm.2020.9049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gao J.-R., Qin X.-J., Fang Z.-H., Han L.-P., Guo M.-F., Jiang N.-N. To explore the pathogenesis of vascular lesion of type 2 diabetes mellitus based on the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway. J Diabetes Res. 2019;2019 doi: 10.1155/2019/4650906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Raguraman R., Srivastava A., Munshi A., Ramesh R. Therapeutic approaches targeting molecular signaling pathways common to diabetes, lung diseases and cancer. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2021;178 doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2021.113918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Joshi T., Singh A.K., Haratipour P., Sah A.N., Pandey A.K., Naseri R., et al. Targeting AMPK signaling pathway by natural products for treatment of diabetes mellitus and its complications. J Cell Physiol. 2019;234(10):17212–17231. doi: 10.1002/jcp.28528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hardie D.G., Scott J.W., Pan D.A., Hudson E.R. Management of cellular energy by the AMP-activated protein kinase system. FEBS Lett. 2003;546(1):113–120. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)00560-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ovens A.J., Gee Y.S., Ling N.X., Yu D., Hardee J.P., Chung J.D., et al. Structure-function analysis of the AMPK activator SC4 and identification of a potent pan AMPK activator. Biochem J. 2022;479(11):1181–1204. doi: 10.1042/BCJ20220067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Juszczak F., Caron N., Mathew A.V., Declèves A.-E. Critical role for AMPK in metabolic disease-induced chronic kidney disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(21):7994. doi: 10.3390/ijms21217994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ashrafizadeh M., Mirzaei S., Hushmandi K., Rahmanian V., Zabolian A., Raei M., et al. Therapeutic potential of AMPK signaling targeting in lung cancer: advances, challenges and future prospects. Life Sci. 2021;278 doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2021.119649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hang L., Thundyil J., Lim K.L. Mitochondrial dysfunction and Parkinson disease: a Parkin–AMPK alliance in neuroprotection. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2015;1350(1):37–47. doi: 10.1111/nyas.12820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Woods A., Johnstone S.R., Dickerson K., Leiper F.C., Fryer L.G., Neumann D., et al. LKB1 is the upstream kinase in the AMP-activated protein kinase cascade. Curr Biol. 2003;13(22):2004–2008. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2003.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Momcilovic M., Hong S.-P., Carlson M. Mammalian TAK1 activates Snf1 protein kinase in yeast and phosphorylates AMP-activated protein kinase in vitro. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(35):25336–25343. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M604399200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee S.R., Kwon S.W., Lee Y.H., Kaya P., Kim J.M., Ahn C., et al. Dietary intake of genistein suppresses hepatocellular carcinoma through AMPK-mediated apoptosis and anti-inflammation. BMC Cancer. 2019;19:1–12. doi: 10.1186/s12885-018-5222-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang J., Zhang S-d, Wang P., Guo N., Wang W., Yao L-p, et al. Pinolenic acid ameliorates oleic acid-induced lipogenesis and oxidative stress via AMPK/SIRT1 signaling pathway in HepG2 cells. Eur J Pharmacol. 2019;861 doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2019.172618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ren Z., Xie Z., Cao D., Gong M., Yang L., Zhou Z., et al. C-Phycocyanin inhibits hepatic gluconeogenesis and increases glycogen synthesis via activating Akt and AMPK in insulin resistance hepatocytes. Food Funct. 2018;9(5):2829–2839. doi: 10.1039/c8fo00257f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chauhan S., Singh A.P., Rana A.C., Kumar S., Kumar R., Singh J., et al. Natural activators of AMPK signaling: potential role in the management of type-2 diabetes. J Diabetes Metab Disord. 2022:1–13. doi: 10.1007/s40200-022-01155-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Steinberg G.R., Hardie D.G. New insights into activation and function of the AMPK. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2022:1–18. doi: 10.1038/s41580-022-00547-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Willows R., Sanders M.J., Xiao B., Patel B.R., Martin S.R., Read J., et al. Phosphorylation of AMPK by upstream kinases is required for activity in mammalian cells. Biochem J. 2017;474(17):3059–3073. doi: 10.1042/BCJ20170458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Emerling B.M., Weinberg F., Snyder C., Burgess Z., Mutlu G.M., Viollet B., et al. Hypoxic activation of AMPK is dependent on mitochondrial ROS but independent of an increase in AMP/ATP ratio. Free Radic Biol Med. 2009;46(10):1386–1391. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.02.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Han Y., Wang Q., Song P., Zhu Y., Zou M.-H. Redox regulation of the AMP-activated protein kinase. PLoS One. 2010;5(11) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Anderson K.A., Ribar T.J., Lin F., Noeldner P.K., Green M.F., Muehlbauer M.J., et al. Hypothalamic CaMKK2 contributes to the regulation of energy balance. Cell Metab. 2008;7(5):377–388. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2008.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Carling D. AMPK signalling in health and disease. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2017;45:31–37. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2017.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang J., Li J., Song D., Ni J., Ding M., Huang J., et al. AMPK: implications in osteoarthritis and therapeutic targets. Am J Tourism Res. 2020;12(12):7670. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Viollet B., Horman S., Leclerc J., Lantier L., Foretz M., Billaud M., et al. AMPK inhibition in health and disease. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 2010;45(4):276–295. doi: 10.3109/10409238.2010.488215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Röckl K.S., Witczak C.A., Goodyear L.J. Signaling mechanisms in skeletal muscle: acute responses and chronic adaptations to exercise. IUBMB Life. 2008;60(3):145–153. doi: 10.1002/iub.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Okamoto S., Asgar N.F., Yokota S., Saito K., Minokoshi Y. Role of the α2 subunit of AMP-activated protein kinase and its nuclear localization in mitochondria and energy metabolism-related gene expressions in C2C12 cells. Metabolism. 2019;90:52–68. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2018.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sun W., Lou K., Chen L., Liu S., Pang S. Lipocalin-2: a role in hepatic gluconeogenesis via AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) J Endocrinol Investig. 2021:1–13. doi: 10.1007/s40618-020-01494-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Carling D., Thornton C., Woods A., Sanders M.J. AMP-activated protein kinase: new regulation, new roles? Biochem J. 2012;445(1):11–27. doi: 10.1042/BJ20120546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zuurbier C.J., Bertrand L., Beauloye C.R., Andreadou I., Ruiz‐Meana M., Jespersen N.R., et al. Cardiac metabolism as a driver and therapeutic target of myocardial infarction. J Cell Mol Med. 2020;24(11):5937–5954. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.15180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bandyopadhyay G.K., Yu J.G., Ofrecio J., Olefsky J.M. Increased malonyl-CoA levels in muscle from obese and type 2 diabetic subjects lead to decreased fatty acid oxidation and increased lipogenesis; thiazolidinedione treatment reverses these defects. Diabetes. 2006;55(8):2277–2285. doi: 10.2337/db06-0062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xu X.J., Gauthier M.-S., Hess D.T., Apovian C.M., Cacicedo J.M., Gokce N., et al. Insulin sensitive and resistant obesity in humans: AMPK activity, oxidative stress, and depot-specific changes in gene expression in adipose tissue. J Lipid Res. 2012;53(4):792–801. doi: 10.1194/jlr.P022905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Townsend L.K., Steinberg G.R. AMPK and the endocrine control of metabolism. Endocr Rev. 2023;44(5):910–933. doi: 10.1210/endrev/bnad012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Maslowski K.M., Mackay C.R. Diet, gut microbiota and immune responses. Nat Immunol. 2011;12(1):5–9. doi: 10.1038/ni0111-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wu H.-J., Wu E. The role of gut microbiota in immune homeostasis and autoimmunity. Gut Microbes. 2012;3(1):4–14. doi: 10.4161/gmic.19320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Santiago-Fernández C., Martin-Reyes F., Tome M., Ocaña-Wilhelmi L., Rivas-Becerra J., Tatzber F., et al. Oxidized LDL modify the human adipocyte phenotype to an insulin resistant, proinflamatory and proapoptotic profile. Biomolecules. 2020;10(4) doi: 10.3390/biom10040534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.O'Neill L.A., Hardie D.G. Metabolism of inflammation limited by AMPK and pseudo-starvation. Nature. 2013;493(7432):346–355. doi: 10.1038/nature11862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Xiong X.-Q., Geng Z., Zhou B., Zhang F., Han Y., Zhou Y.-B., et al. FNDC5 attenuates adipose tissue inflammation and insulin resistance via AMPK-mediated macrophage polarization in obesity. Metabolism. 2018;83:31–41. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2018.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Raucci R., Rusolo F., Sharma A., Colonna G., Castello G., Costantini S. Functional and structural features of adipokine family. Cytokine. 2013;61(1):1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2012.08.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Steinberg G.R., Michell B.J., van Denderen B.J., Watt M.J., Carey A.L., Fam B.C., et al. Tumor necrosis factor α-induced skeletal muscle insulin resistance involves suppression of AMP-kinase signaling. Cell Metab. 2006;4(6):465–474. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yang Y., Liu Y., Xue J., Yang Z., Shi Y., Shi Y., et al. MicroRNA-141 targets Sirt1 and inhibits autophagy to reduce HBV replication. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2017;41(1):310–322. doi: 10.1159/000456162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sag D., Carling D., Stout R.D., Suttles J. Adenosine 5′-monophosphate-activated protein kinase promotes macrophage polarization to an anti-inflammatory functional phenotype. J Immunol. 2008;181(12):8633–8641. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.12.8633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Galic S., Fullerton M.D., Schertzer J.D., Sikkema S., Marcinko K., Walkley C.R., et al. Hematopoietic AMPK β1 reduces mouse adipose tissue macrophage inflammation and insulin resistance in obesity. J Clin Investig. 2011;121(12):4903–4915. doi: 10.1172/JCI58577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jung T.W., Park H.S., Choi G.H., Kim D., Lee T. β-aminoisobutyric acid attenuates LPS-induced inflammation and insulin resistance in adipocytes through AMPK-mediated pathway. J Biomed Sci. 2018;25:1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12929-018-0431-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tian J., Lian F., Yang L., Tong X. Evaluation of the Chinese herbal medicine Jinlida in type 2 diabetes patients based on stratification: results of subgroup analysis from a 12-week trial. J Diabetes. 2018;10(2):112–120. doi: 10.1111/1753-0407.12559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kwon C.H., Sun J.L., Kim M.J., Abd El-Aty A., Jeong J.H., Jung T.W. Clinically confirmed DEL-1 as a myokine attenuates lipid-induced inflammation and insulin resistance in 3T3-L1 adipocytes via AMPK/HO-1-pathway. Adipocyte. 2020;9(1):576–586. doi: 10.1080/21623945.2020.1823140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Herman R., Kravos N.A., Jensterle M., Janež A., Dolžan V. Metformin and insulin resistance: a review of the underlying mechanisms behind changes in GLUT4-mediated glucose transport. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(3) doi: 10.3390/ijms23031264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.O'Neill H.M., Maarbjerg S.J., Crane J.D., Jeppesen J., Jørgensen S.B., Schertzer J.D., et al. AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) β1β2 muscle null mice reveal an essential role for AMPK in maintaining mitochondrial content and glucose uptake during exercise. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2011;108(38):16092–16097. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1105062108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hong S.H., Lee D.-B., Yoon D.-W., Kim J. Melatonin improves glucose homeostasis and insulin sensitivity by mitigating inflammation and activating AMPK signaling in a mouse model of sleep fragmentation. Cells. 2024;13(6):470. doi: 10.3390/cells13060470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rasmussen B.B., Holmbäck U.C., Volpi E., Morio-Liondore B., Paddon-Jones D., Wolfe R.R. Malonyl coenzyme A and the regulation of functional carnitine palmitoyltransferase-1 activity and fat oxidation in human skeletal muscle. J Clin Investig. 2002;110(11):1687–1693. doi: 10.1172/JCI15715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tokarska-Schlattner M., Kay L., Perret P., Isola R., Attia S., Lamarche F., et al. Role of cardiac AMP-activated protein kinase in a non-pathological setting: evidence from cardiomyocyte-specific, inducible AMP-activated protein kinase α1α2-knockout mice. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021:2903. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2021.731015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]