Abstract

Background

Case-based learning (CBL), an innovative teaching approach distinct from traditional methodologies, has gained increasing popularity in pharmacy education. This study aims to conduct a systematic investigation into the effectiveness of CBL, offering evidence-based insights to inform future research and instructional practices in pharmacy education.

Methods

A comprehensive search of related literature published prior to June 2023 was performed across seven databases, including China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), Wanfang Database, VIP China Science and Technology Journal, PubMed, Cochrane Library, Embase, and Medline. Following predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria, eligible studies underwent rigorous screening. The Cochrane Risk of Bias Assessment Tool was utilized to assess methodological quality, with RevMan 5.4.1 employed for systematic review and meta-analysis.

Results

An initial retrieval yielded 2,267 studies, of which 11 studies involving 1,339 pharmacy students met the final inclusion criteria. Based on the studies included, the CBL group demonstrated significantly higher exam scores compared to the lecture-based learning (LBL) group (standardized mean difference [SMD] = 0.58, 95% confidence interval [CI] [0.39, 0.77], P < 0.05). In addition, CBL led to substantial enhancements in communication/collaboration skills (risk ratio [RR] = 2.49, 95% CI [1.17, 5.27], P < 0.05), problem-solving abilities (RR = 2.19, 95% CI [1.26, 3.80], P < 0.05), and clinical practice skills (RR = 2.39, 95% CI [1.46, 3.92], P < 0.05). Moreover, students reported higher satisfaction with CBL-based instruction compared to LBL (RR = 1.63, 95% CI [1.22, 2.18], P < 0.05).

Conclusions

CBL effectively enhances pharmacy students’ exam performance, communication and team collaboration skills, problem-solving abilities, clinical practice skills, and instructional satisfaction.

Trial registration

International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO), CRD 42,024,537,606.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12909-025-07927-9.

Keywords: Case-based learning, Lecture-based learning, Pharmacy education, Systematic review, Meta-analysis

Background

The International Pharmaceutical Federation, in collaboration with the World Health Organization and the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, established the Pharmacy Education Taskforce, which defined pharmacy education as the design of education programs across varying scope levels, aiming to cultivate a professional workforce for the pharmacy and pharmaceutical-related industries [1]. These scope levels encompass undergraduate education, graduate education, professional continuing education in pharmacy, and practical placements [1, 2]. For years, lecture-based learning (LBL), a quintessential traditional teaching approach, has been widely utilized in pharmacy education. However, with the advancement of modern education, the limitations of conventional teaching methods have become increasingly evident [3, 4]. Students often find themselves passively receiving instruction rather than actively engaging in classroom activities. As teaching reforms progress, innovative teaching methods such as interactive LBL and lecture capture technology have been introduced and implemented in pharmacy education settings, yielding promising results in enhancing learning outcomes [5, 6].

Case-based learning (CBL), a non-traditional teaching method, is a problem-oriented teaching model centered on clinical cases, requiring the application of relevant professional knowledge and clinical thinking to solve problems. Prior to class, teachers distribute prepared cases (typically adapted from real clinical scenarios) to students, who then reference literature and reading materials to analyze and address the clinical challenges during class sessions. Initially developed by Harvard Law School, CBL was gradually adopted across diverse educational fields such as medicine, business, and management science, often being integrated with other teaching approaches to enhance instructional efficacy [7–10]. In pharmacy education, CBL is widely implemented, as students need more than theoretical instruction to be equipped for clinical practice upon graduation.

Chen et al. conducted a systematic evaluation of CBL’s effectiveness in medical education, with all included studies confirming that CBL significantly enhances students’ knowledge acquisition, learning interest, professional skills, and learning abilities compared to the didactic approach [11]. Miao et al. performed a comprehensive investigation of CBL’s efficacy in nursing education. Results showed that CBL significantly outperformed traditional teaching methods in nursing education for enhancing students’ theoretical knowledge (SMD = 0.92, 95% CI [0.53, 1.31], P < 0.01) and practical skills (SMD = 0.63, 95% CI [0.44, 0.82], P < 0.01) [12]. In pharmacy education, numerous studies have applied CBL across disciplines such as pharmacognosy, pharmacy administration, management and regulations, and pharmaceutics [13–17]. However, these investigations exhibit heterogeneous methodological quality, inconsistent results, divergent assessment criteria, and a lack of definitive consensus. To date, there is a lack of high-quality systematic reviews specifically on CBL’s effectiveness in pharmacy education. Therefore, our study aimed to evaluate the impact of CBL in pharmacy education through a comprehensive literature synthesis, providing valuable insights for future research and instructional practice in this field.

Methods

This study was conducted following the criteria of the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) statement [18] (SM Table 1 in Supplementary Material) and registered in PROSPERO (CRD 42024537606). Due to the complexity and heterogeneity of the study results, we amended the outcomes section of the original protocol registered on PROSPERO (https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/view/CRD42024537606). Specifically, we consolidated similar results into five outcome categories: exam scores, communication and collaboration skills, problem-solving abilities, clinical practice skills, and class satisfaction. Correspondingly, adjustments were made to data extraction and quality assessment to align with these revised outcome categories.

Table 1.

General characteristics of the studies included

| Study ID (author, publication year) | Country | Courses involved | Study design | Sample size (CBL/LBL) | Participants | Outcomes* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dupuis, 2008 [19] | United States | Clinical pharmacokinetics | RCT | 395 (144/251) | Pharmacy undergraduates | ①⑤ |

| Wang Y, 2010 [20] | China | Clinical pharmacotherapeutics | RCT | 58 (30/28) | Pharmacy undergraduates | ①②③④⑤ |

| Yuan, 2013 [21] | China | Pediatric clinical pharmacology | RCT | 80 (40/40) | Pharmacy undergraduates | ①⑤ |

| Song, 2014 [22] | China | Pharmacology | RCT | 122 (60/62) | Pharmacy undergraduates | ②③④⑤ |

| Nian, 2015 [23] | China | Clinical pharmacy | RCT | 90 (45/45) | Pharmacy interns | ②③④⑤ |

| Li, 2016 [24] | China | Human anatomy physiology | RCT | 45 (20/25) | Pharmacy undergraduates | ①②③⑤ |

| Meng, 2018 [25] | China | Pharmacognosy | RCT | 58 (29/29) | Pharmacy undergraduates | ①②④ |

| Wang H, 2018 [26] | China | Clinical pharmacology | RCT | 100 (50/50) | Pharmacy undergraduates | ① |

| Yang, 2020 [27] | China | Pharmacology | RCT | 160 (77/83) | Pharmacy undergraduates | ①③④⑤ |

| Alsunni, 2020 [28] | Saudi Arabia | Cardiovascular physiology | RCT | 171 (94/77) | Pharmacy undergraduates | ①④⑤ |

| Dong, 2021 [29] | China | Narcotic psychopharmacology | RCT | 60 (30/30) | Pharmacy interns | ①③⑤ |

① exam scores; ② communication and collaboration skills; ③ problem-solving abilities; ④ clinical practice skills; ⑤ class satisfaction

RCT Randomized Controlled Trial

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) participants: pharmacy students, including undergraduate students, graduate students, post-graduation students, those enrolled in continuing education or vocational education programs, and pharmacy interns; (2) intervention: CBL; (3) comparison: traditional teaching methods such as LBL; (4) outcome measures: learning outcomes including exam scores, communication and collaboration skills, problem-solving abilities, clinical practice skills, and class satisfaction; (5) study types: randomized controlled trials (RCTs).

The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) studies with no titles or abstracts; (2) studies not published in Chinese or English; (3) studies for which the full text could not be retrieved.

Search strategy

Two trained researchers (XF and MC) conducted a comprehensive literature search in PubMed, Embase, Cochrane Library, Medline, China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), VIP China Science and Technology Journal (VIP), and WanFang databases for RCTs on CBL in pharmacy education. Search terms included “case-based learning,” “CBL,” “pharmacy,” “pharmaceutical education,” and “pharmacy education” (using a combination of subject headings and free-text keywords). Studies published before June 20, 2023, were included. The reference lists of retrieved studies were also screened for additional relevant works (SM Table 2 in Supplementary Material).

Table 2.

The effect of CBL on exam scores, students’ capabilities, and class satisfaction compared to LBL

| Study ID (author, publication year) | Sample size (CBL/LBL) | Theoretical exam scores improved | Communication and collaboration skills improved | Problem-solving abilities improved | Clinical practice skills improved | Class satisfaction improved | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CBL | LBL | CBL | LBL | CBL | LBL | CBL | LBL | CBL | LBL | ||

| Dupuis, 2008 [19] | 395 (144/251) | 86.50 ± 10.50 | 82.00 ± 11.00 | N/M | N/M | N/M | N/M | N/M | N/M | * | * |

| Wang Y, 2010 [20] | 58 (30/28) | 77.30 ± 9.70 | 74.40 ± 11.30 | 27/30 | ** | 28/30 | ** | 30/30 | ** | 29/30 | ** |

| Yuan, 2013 [21] | 80 (40/40) | 93.25 ± 18.67 | 80.87 ± 20.41 | N/M | N/M | N/M | N/M | N/M | N/M | 37/40 | 23/40 |

| Song, 2014 [22] | 122 (60/62) | N/M | N/M | 49/60 | 14/62 | 48/60 | 17/62 | 54/60 | 18/62 | * | ** |

| Nian, 2015 [23] | 90 (45/45) | N/M | N/M | 43/45 | 24/45 | 41/45 | 24/45 | 44/45 | 23/45 | 43/45 | 20/45 |

| Li, 2016 [24] | 45 (25/20) | 78.00 ± 14.74 | 71.86 ± 15.40 | 20/25 | ** | 24/25 | ** | N/M | N/M | 18/25 | ** |

| Meng, 2018 [25] | 58 (29/29) | 79.45 ± 11.23 | 76.89 ± 10.24 | * | * | N/M | N/M | * | * | N/M | N/M |

| Wang H, 2018 [26] | 100 (50/50) | 78.90 ± 10.20 | 70.20 ± 14.70 | N/M | N/M | N/M | N/M | N/M | N/M | N/M | N/M |

| Yang, 2020 [27] | 160 (77/83) | 84.02 ± 14.34 | 72.45 ± 13.23 | N/M | N/M | 68/77 | ** | 69/77 | ** | 70/77 | ** |

| Alsunni, 2020 [28] | 171 (94/77) | 81.24 ± 4.82 | 79.00 ± 3.90 | N/M | N/M | N/M | N/M | 71/88*** | ** | 70/88*** | ** |

| Dong, 2021 [29] | 60 (30/30) | 90.58 ± 3.77 | 84.26 ± 5.14 | N/M | N/M | * | * | N/M | N/M | 29/30 | 22/30 |

*Instead of reporting the number of students who perceived skill improvements from the teaching method, the research utilized grading scores to demonstrate significant enhancements in skills associated with CBL. **Only the results of CBL group were reported. ***In Alsunni’s study, 94 pharmacy students participated in the CBL program, though only 88 valid questionnaires were included in the final analysis

N/M Not Mentioned

Study selection and data extraction

Two trained researchers (XL and QL) independently screened literature according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria and cross-validated the results. They first reviewed titles and abstracts; studies meeting the inclusion criteria underwent full-text review. In cases of disagreements, discussions with a third researcher (JN) were conducted to reach a consensus. Authors were contacted for clarification when incomplete data were identified. Using a pre-established data extraction form, the researchers extracted details including primary author, publication year, course topics, study participants, sample size per group, and outcome measures.

Evaluation of the reporting quality

Two trained reviewers (XL and QL) independently evaluated the methodological quality of included studies using the Cochrane Risk of Bias Assessment Tool (Cochrane RoB2). Discrepancies in assessments were resolved through discussion with a third researcher (JN). The following domains were evaluated: (1) random sequence generation; (2) allocation concealment; (3) blinding of participants and personnel; (4) blinding of outcome assessment; (5) incomplete outcome data; (6) selective reporting; (7) other potential sources of bias. Risk of bias for each domain was categorized as high risk, low risk, or unclear. A risk of bias summary graph was generated using RevMan 5.4.1.

Data analysis

RevMan 5.4.1 software was used to perform quantitative meta-analysis, with the chi-squared (χ²) test employed to assess statistical heterogeneity. For dichotomous outcomes, relative risk (RR) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) were calculated. For continuous outcomes, mean differences (MD) or standardized mean differences (SMD) with 95% CIs were reported, integrating mean values and standard deviations (SDs) from intervention and control groups, including adjustments for different measurement scales when necessary. A fixed-effect model was applied for meta-analysis when heterogeneity was non-significant (P ≧ 0.05 and I2 < 50%); if significant heterogeneity was detected (P < 0.05 or I2 ≧ 50%), potential sources were explored. If heterogeneity could not be resolved, a random-effect model was used instead. Data unsuitable for quantitative synthesis underwent descriptive analysis. Sensitivity analyses will also be conducted to explore potential factors influencing the results and assess the robustness of the findings. Publication bias was assessed using a funnel plot drawn by RevMan 5.4.1 software.

Results

Results of the literature search

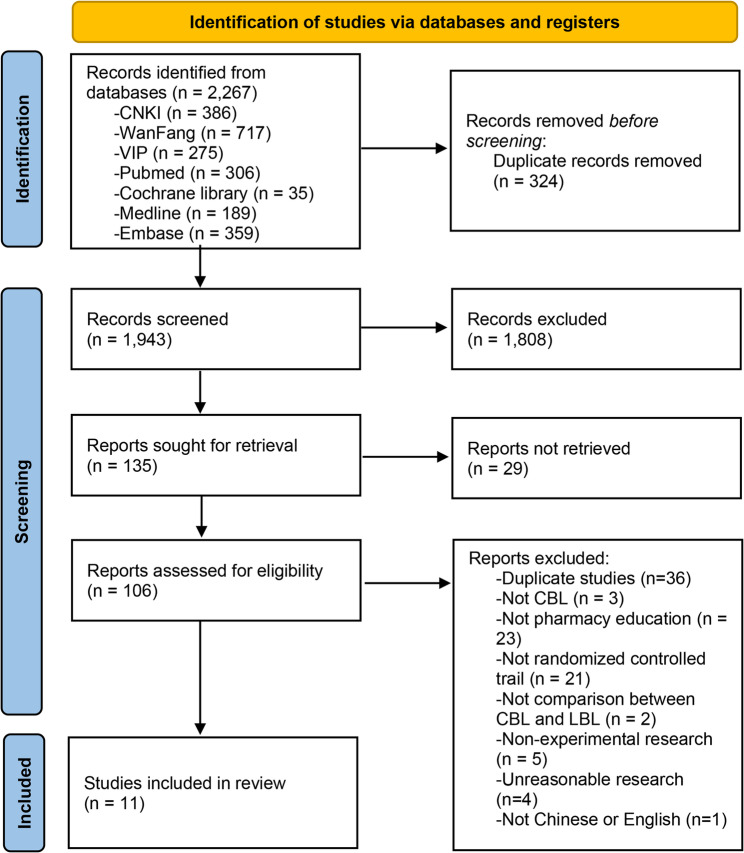

The initial Literature search yielded 2,267 studies. Following sequential screening of titles, abstracts, and full texts, 11 studies were included in the systematic review, comprising nine published in Chinese and two in English (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of literature search

General information of the studies included

A total of 1,339 pharmacy students were included across the 11 studies, of whom 619 received CBL and 720 received LBL in pharmacy education courses. The general characteristics of the included studies were summarized in Table 1.

Studies included in the review were published between 2008 and 2021, with nine (81.82%) conducted in China, one (9.09%) in the United States, and one (9.09%) in Saudi Arabia. The courses addressed in the studies spanned pharmacology, pharmacognosy, clinical pharmacy, clinical pharmacotherapeutics, human anatomy and physiology, clinical pharmacokinetics, and narcotic psychopharmacology. Given the variability in reported outcomes across studies, we consolidated similar measures into five secondary outcome categories: exam scores, communication and collaboration skills, problem-solving abilities, clinical practice skills, and class satisfaction (SM Table 3 in Supplementary Material). All studies administered post-class questionnaires. Specifically, nine studies [19–21, 24–29] reported on exam score outcomes, five [20, 22–25] assessed communication and collaboration skills, six [20, 22–24, 27, 29] evaluated problem-solving abilities, six [20, 22, 23, 25, 27, 28] investigated clinical practice skills, and nine [19–24, 27–29] examined class satisfaction with CBL. Detailed comparisons of exam scores, students’ capabilities, and satisfaction between CBL and LBL groups are summarized in Table 2.

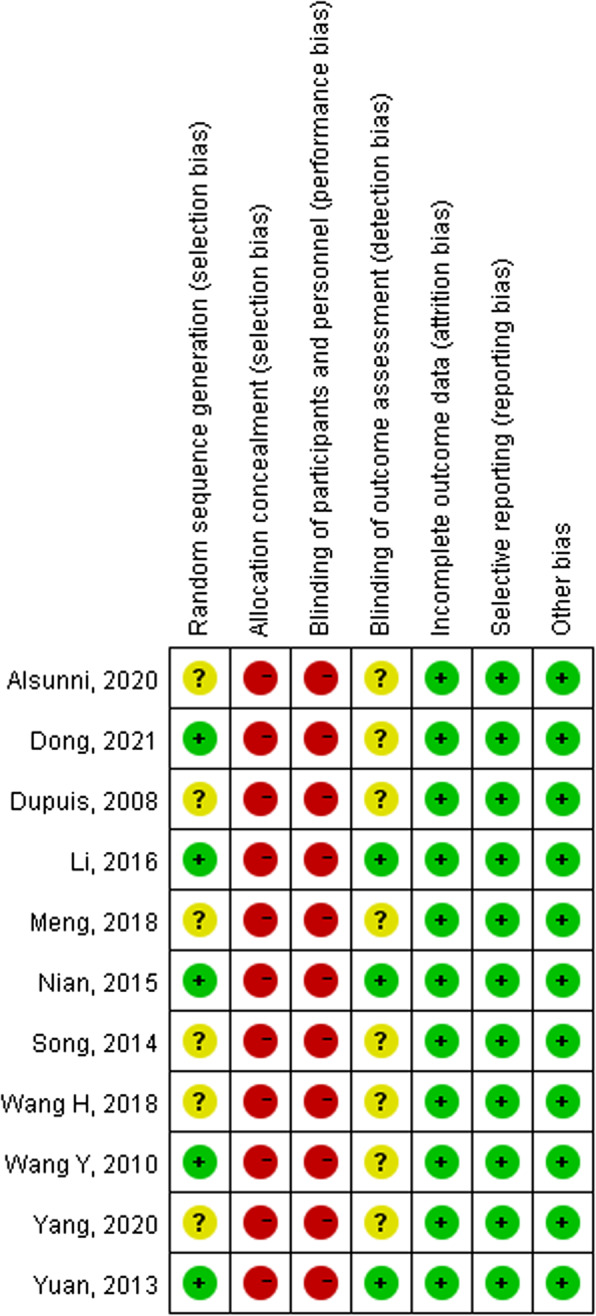

Risk of bias assessment

The methodological quality of RCTs was evaluated using the Cochrane RoB2 (2019 revised version). Five studies [20, 21, 23, 24, 29] reported adequate random sequence generation, and three studies [21, 23, 24] implemented blinding of outcome assessors. Due to the inherent differences between intervention methods (CBL vs. LBL), allocation concealment and blinding of participants/personnel were not feasible in any study. All studies provided complete reporting of outcome data, and no other sources of bias were identified (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Risk of bias assessments for studies included

The effectiveness of CBL in pharmacy education

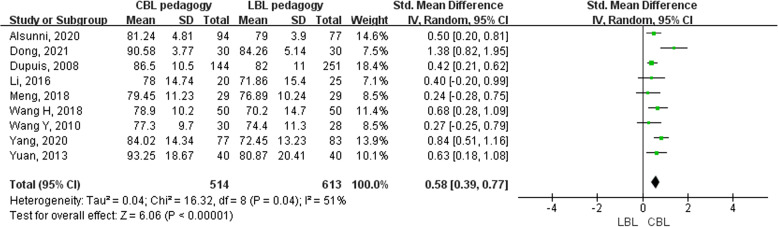

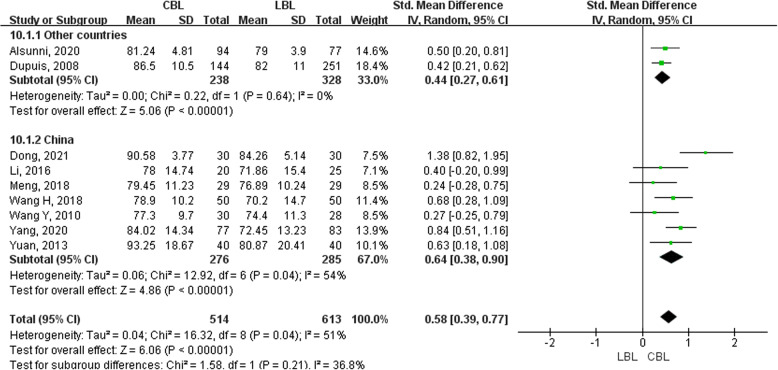

The impact of CBL on exam performance

Nine studies [19–21, 24–29] involving 1,127 pharmacy students (514 in the CBL group and 613 in the LBL group) reported outcomes on exam scores. Moderate heterogeneity was observed among studies, necessitating the use of a random-effect model for meta-analysis. The results showed that the CBL group demonstrated significantly higher exam performance compared to the LBL group (SMD = 0.58, 95% CI [0.39, 0.77], I2 = 51%, P < 0.05) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Forest plot of the impact of CBL on students’ exam performance

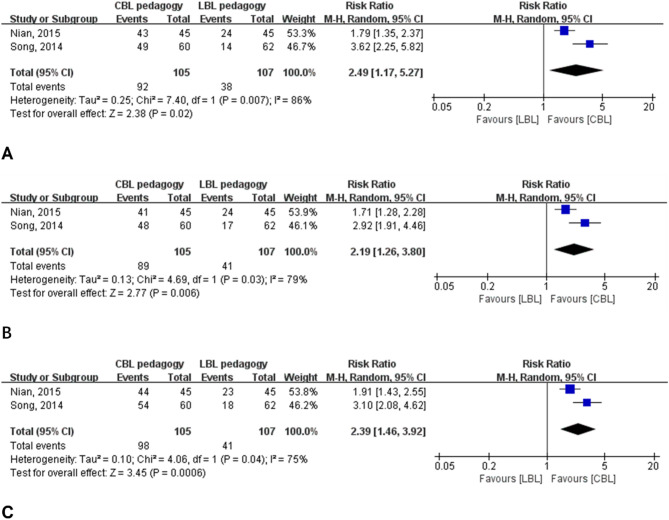

The effect of CBL on students’ capabilities

Regarding students’ capabilities, outcomes were categorized into secondary indicators: communication and collaboration skills, problem-solving abilities, and clinical practice skills. Five studies [20, 22–25] involving 373 students used questionnaire surveys to assess the impact of CBL on communication and collaboration skills. Only two of them [22, 23] quantitatively reported grading scores comparing CBL and LBL groups. Meta-analysis of these two studies revealed that CBL significantly enhanced communication and collaboration skills compared to LBL (RR = 2.49, 95% CI [1.17–5.27], I2 = 86%, P < 0.05) (Fig. 4A). One study [25] employed a scoring methodology showing CBL outperformed LBL in “student interactivity” (P < 0.05). Two studies [20, 24] reported questionnaire results exclusively for CBL groups, indicating 80%−90% of students perceived improvements in communication and collaboration skills.

Fig. 4.

Forest plot of the impact of CBL on students’ capabilities: A the impact of CBL on students’ communication and collaboration skills; B the impact of CBL on students’ problem-solving abilities; C the impact of CBL on students’ clinical practice skills

Six studies [20, 22–24, 27, 29] involving 535 pharmacy students assessed the impact of CBL on problem-solving abilities through questionnaire surveys. Meta-analysis of the two studies [22, 23] with quantitative data showed that CBL significantly improved problem-solving abilities compared to LBL (RR = 2.19, 95% CI [1.26–3.80], I2 = 79%, P < 0.05) (Fig. 4B). One study [29] used a scoring method to demonstrate that CBL outperformed LBL in “problem-solving abilities” (P < 0.05). Three studies [20, 24, 27] reported results exclusively for the CBL group, with 93%−96% of students indicating that CBL enhanced their problem-solving abilities through questionnaire responses.

Six studies [20, 22, 23, 25, 27, 28] involving 659 pharmacy students evaluated the impact of CBL on students’ clinical practice skills through questionnaire surveys. Meta-analysis of the two studies [22, 23] with quantitative data showed that CBL significantly enhanced clinical practice skills compared to LBL (RR = 2.39, 95% CI [1.46–3.92], I2 = 75%, P < 0.05) (Fig. 4C). One study [25] used a rating scale to demonstrate that CBL outperformed LBL in “improvement of practical ability” (P < 0.05). Three studies [20, 27, 28] reported results exclusively for the CBL group, with 80%−100% of students indicating through questionnaires that CBL improved their clinical practice skills.

Overall, the findings indicate that when compared with LBL, CBL significantly enhanced students’ communication and collaboration skills, problem-solving abilities, and clinical practice skills.

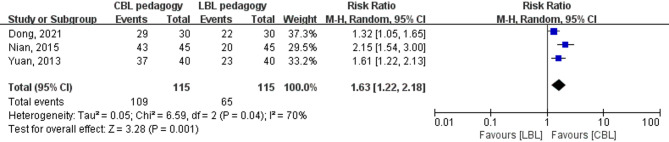

The impact of CBL on class satisfaction

Nine studies [19–24, 27–29] involving 1,181 students evaluated students’ class satisfaction through questionnaire surveys. Meta-analysis of the three studies [21, 23, 29] with quantitative data on class satisfaction revealed that students in the CBL group reported significantly higher class satisfaction than those in the LBL group (RR = 1.63, 95% CI [1.22–2.18], I2 = 70%, P < 0.05) (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Forest plot of the impact of CBL on class satisfaction

Sensitivity analysis and publication bias assessment

There was some moderate heterogeneity in the outcome measure of the impact of CBL on exam performance, so we conducted sensitivity analyses for different countries. Results were consistently significant, with higher exam scores in the CBL group compared to the LBL group, indicating region was not a primary source of heterogeneity (Fig. 6). Between the studies in China, the pooled effect size remained statistically significant across all iterations when leave-one-out approach (SMD = 0.52–0.62, all P < 0.05). Thus, the overall effect remained stable and statistically significant, validating the robustness of the meta-analytic conclusions.

Fig. 6.

Forest plot of the impact of CBL on students’ exam performance by subgroup analysis

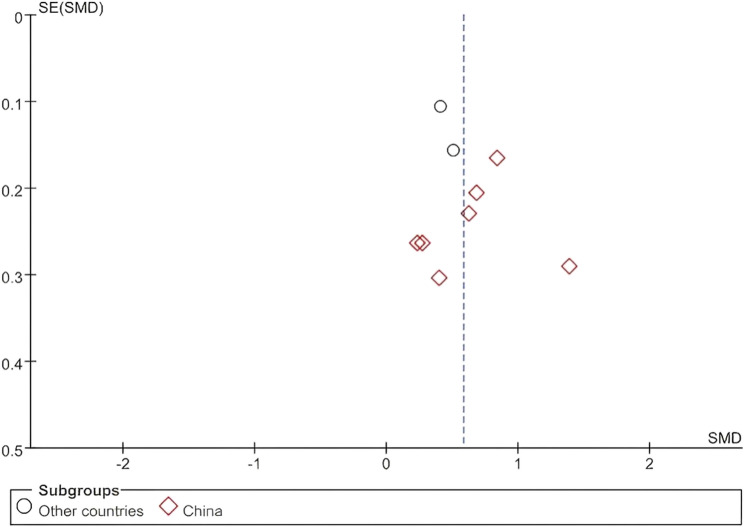

Assessment of publication bias using funnel plots typically requires inclusion of a certain number of articles, usually more than 10. In this study, the vast majority of outcome indicators were evaluated in a limited number of articles. We used a funnel plot to evaluate publication bias for the exam performance outcome indicator, which included 9 studies. The results showed that the distribution of studies on both sides of the funnel was asymmetric, suggesting potential publication bias, which might be attributed to the small number of included studies (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Funnel plot of the impact of CBL on students’ exam performance

Discussion

With the advancement of modern education, innovative pedagogical approaches such as CBL, problem-based learning (PBL), team-based learning (TBL), and interprofessional education (IPE) have gained substantial attention in healthcare education. Systematic reviews by Galvao et al. and Lang et al. demonstrated that methods like PBL and TBL significantly enhanced academic performance among pharmacy students compared to traditional LBL [30, 31]. CBL, in particular, has emerged as a prominent method due to its integration of real-world clinical cases into classroom instruction, prompting educators to explore its adaptive potentials. For example, Huang et al. successfully combined CBL with TBL in pharmacology teaching to achieve superior learning outcomes [32].

Zainal et al. and Tsekhmister et al. explored the effectiveness of CBL through systematic reviews [33, 34]. Zainal et al. noted that CBL enhanced students’ average test scores and was well-suited for case-intensive disciplines such as clinical/primary care. Notably, students generally preferred courses redesigned with CBL, while educators recognized its utility in strengthening learning outcomes for case-oriented subjects like therapeutics and clinical pharmacy [33]. Unlike Zainal et al.’s review, which included 12 observational studies, our research incorporated RCTs. Tsekhmister et al. found that CBL improved academic performance and case analysis skills among medical and pharmacy undergraduates, though their studies primarily focused on academic outcomes and participants’ satisfaction [34]. In contrast, our research emphasized broader impacts, such as communication and teamwork skills. Additionally, while Tsekhmister et al.’s review included 21 RCTs, only two of these involved pharmacy students. Our study aligns with their findings regarding CBL’s superiority but offers a more specific focus on pharmacy education, highlighting its unique applications in this context.

While CBL offers notable educational benefits, its effectiveness is context-dependent and may be compromised by scenarios such as students lacking foundational knowledge or prerequisite skills for independent case analysis, leading to cognitive overload or superficial engagement; poorly designed cases that are either too simplistic to foster critical thinking or overly complex without clear objectives; facilitators lacking clinical expertise or pedagogical training, resulting in unstructured debates or misdirected problem-solving; insufficient time allocation forcing rushed conclusions and sacrificing collaborative processes; assessment strategies misaligning with CBL goals by relying on traditional exams and neglecting applied skills; or students resisting active learning due to ingrained passive habits; however, crucial considerations to maximize CBL’s potential include ensuring student preparation through baseline knowledge provision and orientation to active learning norms via pre-class materials and formative assessments, designing authentic clinically relevant cases that unfold progressively to mirror real-world reasoning and align with curricular objectives [26], equipping instructors with dual competence in content mastery and facilitation to guide discussions without dominance while linking case insights to theory [24], allocating adequate time for pre-class preparation and in-class discussion while calibrating with evaluators for consistent pacing, developing assessments that evaluate both process (collaboration, reasoning) and outcomes (solutions, reflections) using standardized rubrics and validated tools to mitigate subjectivity, and addressing student resistance through clear goal communication, gradual exposure to interactive formats, and incorporating feedback to bridge the gap from passive LBL cultures by highlighting CBL’s value in enhancing learning outcomes [23].

This study found that CBL was widely researched and applied in healthcare education. Based on available evidence, our findings confirm that CBL significantly enhances pharmacy students’ learning outcomes, providing robust evidence for its integration into pharmacy education curricula.

Included studies show that courses in pharmacy education suitable for CBL (rather than LBL) share key characteristics: they require more than rote memorization, requiring students to integrate theoretical knowledge with practical application, navigate complex, context-dependent scenarios, and develop problem-solving and clinical reasoning skills. Such courses including Clinical Pharmacokinetics, Pharmacognosy, Clinical Pharmacology, and clinical pharmacy practicums all emphasize the application of knowledge to real or simulated patient cases, whether focusing on foundational drug mechanisms, organ system functions, specialized therapeutic areas, or direct patient care. Their focus on bridging theory and practice, analyzing multifaceted problems, and fostering collaborative decision-making aligns with CBL’s strengths in contextualized, interactive learning, making them better suited to this approach than LBL. Implementing CBL in these courses not only enhances theoretical mastery but also cultivates communication, teamwork, and critical thinking competencies essential for pharmacy practice.

Several limitations should be acknowledged. Firstly, although this systematic review included eleven studies, only five reported using lottery methods for random sequence generation, while the remaining studies did not specify their randomization procedures. Due to the inherent differences between the two teaching approaches (CBL vs. LBL), neither allocation concealment nor double-blinding of researchers and participants was feasible in any study. This high risk of bias in allocation concealment and blinding across all included studies may have systematically influenced the study outcomes. For instance, researchers or participants aware of the intervention assignment might have unconsciously exaggerated the perceived benefits of CBL, introducing overestimation bias into the results. Additionally, the small sample sizes in most studies may have compromised the reliability of the results. The impact of CBL on learning outcomes was primarily assessed through questionnaire surveys, which may have introduced subjectivity bias influenced by students’ personal perceptions. Notably, significant heterogeneity was observed across studies in case scenario design, course selection, and combined teaching methods. This high heterogeneity could undermine the robustness of meta-analysis results, as the pooled effect sizes may mask true differences between studies or overemphasize consistencies where variability actually dominates, reducing the credibility of the synthesized findings.

Moreover, outcome assessment methods lacked standardization: varied questionnaire items across studies necessitated categorizing similar questions into five secondary outcome indicators, which may have introduced inaccuracies or ambiguities. This diversity in outcome measures not only hindered direct comparability between studies but also increased the complexity of meta-analysis, as aggregating heterogeneous outcomes could dilute the precision of pooled results. Therefore, future research is recommended to adopt standardized outcome measures, such as developing unified questionnaires for evaluating learning outcomes. Notably, since most included studies were conducted in China, these findings may have limited generalizability to diverse educational contexts worldwide, requiring validation in more geographically and culturally diverse settings.

Conclusions

Based on available evidence, this study demonstrates that CBL has yielded promising outcomes in pharmacy education over the past decade. CBL enhances pharmacy students’ exam performance, communication and collaboration skills, problem-solving abilities, clinical practice skills, and class satisfaction. Future research should prioritize studies with high methodological quality and standardized outcome measures to strengthen evidence synthesis.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgments

This study was registered in PROSPERO (CRD 42024537606). The review protocol can be accessed at https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/view/CRD42024537606.

Abbreviations

- CBL

Case-based Learning

- CNKI

China National Knowledge Infrastructure

- VIP

VIP China Science and Technology Journal

- LBL

Lecture-based Learning

- PRISMA

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

- RCTs

Randomized Controlled Trials

- Cochrane RoB 2

Cochrane Risk of Bias Assessment Tool 2

- N/M

Not Mentioned

- RR

Relative Risk

- 95% CI

95% Confidence Interval

- SMD

Standardized Mean Difference

- SD

Standard Deviation

- MD

Mean Difference

- PBL

Problem-based Learning

- TBL

Team-based Learning

- IPE

Interprofessional Education

Authors’ contributions

MC and JN conceived and devised the study methodology. XL and QL conducted the literature research, screening, data extraction, and quality assessment. XF, YL, JZ, and YL conducted the statistical analysis and interpretation of the results. XL, MC, and JN completed the manuscript draft. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (YJ202339), the Sichuan Science and Technology Program (2025JDKP0108), the Sichuan University Research Funds for Graduate Education and Teaching Reform (GSSCU2023120), and the Sichuan University Research Funds for Basic Medicine Research.

Data availability

The datasets used or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Anderson C, Bates I, Beck D, The WHO UNESCO FIP pharmacy education taskforce, et al. The WHO UNESCO FIP Pharmacy Education Taskforce. Hum Resour Health. 2009. 10.1186/1478-4491-7-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Arakawa C. Pharmacy education development. Pharmacy (Basel). 2021. 10.3390/pharmacy9040168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Poirier TI. Is lecturing obsolete?? Advocating for high value transformative lecturing. Am J Pharm Educ. 2017;81(5):83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Short F, Martin J. Presentation vs performance: effects of lecturing style in higher education on student preference and student learning. Psy Teach Rev. 2011;17(2):71–82. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yaser Al-Worafi. Lecture-Based/Interactive Lecture- Based Learning in Pharmacy Education. A Guide to Online Pharmacy Education. 1st Edition. 2022:5.

- 6.Fina Paul. Lecture capture is the new standard of practice in pharmacy education. Am J Pharm Educ. 2023;87(2):ajpe8997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thistlethwaite JE, Davies D, Ekeocha S, et al. The effectiveness of case-based learning in health professional education. A BEME systematic review: BEME guide 23. Med Teach. 2012;34(6):e421–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu J, Lu H. Research into origin characteristics and application of Case-based teaching method. J Nanjing Inst Technology(Social Sci Edition). 2011;11(01):60–4. (Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jin G, Gao Y, Bi Y, et al. Combined application of Case-based learning and problem-based learning in internal medicine course. Chin J Gen Pract. 2016;14(04):672–5. (Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang S, Li P. Application of CBL combined with TBL in pathological experiment teaching. Basic Med Educ. 2014;16(12):1050–2. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen J, Li Y, Tang Y, et al . Case-based learning in education of traditional Chinese medicine: a systematic review. J Tradit Chin Med. 2013;33(5):692–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miao Y. A systematic review of the application effect of the CBL in nursing teaching. Health Vocat Educ. 2017;35(15):49–52. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang Y, Liu S. Preliminary study on applying CBL in pharmacognosy teaching. NORTHWESTMED EDU. 2013;21(5):984–6. (Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang X, Ci W, Wan X. Application of CBL in the teaching of the discipline of pharmacy administration. J Bran Camp First Mil Med Univ. 2005;28(1):16–7. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yu L, Sun W, Su J, et al . Application of CBL in pharmaceutics. Heilongjiang Med Pharm. 2012;35(06):102. (Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Han W, Yang R. Application and effect of CBL in pharmaceutical administration and regulation course. J Shanxi Med Coll Continuing Educ. 2016;26(3):78. (Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pan C, Zhou X. Evaluation of the effect of the CBL of clinical medicine summary in higher vocational pharmacy major. J Ezhou Univ. 2014(6):92–3,96 (Chinese).

- 18.Matthew J, Page JE, McKenzie PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2021;134:178–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dupuis RE, Persky AM. Use of case-based learning in a clinical pharmacokinetics course. Am J Pharm Educ. 2008;72(2):29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang Y, Wang Q, Li Z, et al. An attempt to open CBL in teaching clinical pharmacotherapeutics. Chin J Pharmacoepidemiology. 2010;19(1):53–5. (Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yuan Y, Gu R, Ran S. Experience of CBL in pediatric clinical Pharmacology teaching. Chongqing Med. 2013;42(21):2557–8. (Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Song H, Xue X, Liu D. Research on applying CBL in pharmacy professional pharmacology teaching. Sci Technol Inform. 2014;(12):348–9 (Chinese).

- 23.Nian H, Ma M, Gu X, et al. Exploration of Teaching Quality and Effect of Case-based Learning on Clinical Pharmacy in Integrated Traditional Chinese and Western Medicine Hospital. China Pharmacist. 2015;(9):1593–5 (Chinese).

- 24.Li H. CBL practice of human anatomy and physiology in the pharmacy profession. Basic Med Educ. 2016;18(10):778–81. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meng L, Li J, Wang J, et al. Discussion on improving the teaching quality of pharmacognosy by applying the case teaching method. Stud Trace Elem Health. 2018;35(1):38–40. (Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang H, Chen M, Zhang F, et al. Application of CBL in clinical pharmacology teaching. China High Med Educ. 2018;(10):113–4 (Chinese).

- 27.Yang H, Du X, Cong H, et al. Using research-oriented case study in pharmacology. China High Med Educ. 2020;(09):115–6 (Chinese).

- 28.Alsunni AA, Rafique N. Effectiveness of case-based teaching of cardiovascular physiology in clinical pharmacy students. J Taibah Univ Med Sci. 2020;16(1):22–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dong L, Qu X, Lyu C. Application of case analysis method in the teaching of narcotic psychotropic drugs. China Continuing Med Educ. 2021;13(21):27–31. (Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Galvao TF, Silva MT, Neiva CS, et al . Problem-based learning in pharmaceutical education: a systematic review and meta-analysis. ScientificWorldJournal. 2014;2014:578382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lang B, Zhang L, Lin Y, et al. Team-based learning pedagogy enhances the quality of Chinese pharmacy education: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med Educ. 2019;19:286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huang N, Wu J, Luo H, et al. The practice of english case teaching in Pharmacology teaching. J Kunming Med Univ. 2015;36(5):171–3. (Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zainal Z, Jee L, Hakeem W. A systematic review on the effectiveness of case-based learning (CBL) in the undergraduate pharmacy programme. Pharm Educ. 2024;24(1):478–89. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tsekhmister Y. Effectiveness of case-based learning in medical and pharmacy education: A meta-analysis. Electron J Gen Med. 2023;20(5):em. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.