Abstract

Switching from use of synthetic dyes in the textile industry to ecofriendly organic dyes will be a good initiative to safeguard the environment. As an attempt to contribute to the cause, this study optimized conditions for the growth of a rhizospheric fungus Talaromyces purpureogenus PH7 (PQ281486) and production of a red dye by it, under lab conditions. Additionally, the dye produced by the strain was applied to cotton and cotton fabrics following the standard staining procedure and the dyed fabrics were subjected to washes with hot and cold water, detergents and continuous sunlight as preliminary tests for its use as a potential dye of the textile industry. Maximum growth of the strain and dye production by it were attained at 28 °C and pH7 using dextrose as source carbon in the Czapek medium. On the other hand, high concentration of sodium chloride significantly reduced growth of the strain as well as production of the red dye by it. During evaluation of color as potential textile dye, it efficiently dyed cotton and cotton fabrics that did not get faded by any of the experimental treatments including exposure to hot/cold water, detergents and sunlight. It’s appealing that the effluents generated during culturing of the strain could have an overall beneficial impact on the environment as it produces metabolites with important roles in well-being of plant, like IAA, flavonoids, phenolics, lipids, proteins and sugars, and exhibits strong antioxidant activity. In conclusion, the fungus T. purpureogenus PH7 is a promising candidate for producing a natural, biodegradable yet durable red textile-grade dye in an eco-friendly manner.

Keywords: Fermentation, Talaromyces purpureogenus, Red dye, Textile dyeing, Eco-friendly

Introduction

Globally, applying various types of dyes in different products is vital to human life [1]. Human life is highly dependent on colors in areas such as food, clothing, medications and other industrial applications [2]. Dyes or colorants are highly pigmented substances used for staining a wide range of materials [3]. These dyes enhance the quality of products by altering their original color, taste, safety texture and freshness as well as increasing its nutritional value. Dyes are also used to add color to colorless products [4]. Moreover, these dyes increase the aesthetic value of different kinds of products including food, cosmetics, medications, textiles, ink, wood, paper and other industrial materials [5]. Nearly 170 years ago, different types of dyes were extracted from various natural sources, including plant, animals, insects and minerals [6]. Mauveine, the first purple-colored synthetic dye, was discovered by an 18-year-old chemist, William Henry Perkin in 1856 during an attempt to synthesize quinine [7]. Due to rapid population growth and industrialization, the use of artificial dyes in various industries has dramatically increased over the past century [8]. To date, various kinds of synthetic colors are used for staining different products. These colorants are expensive, time-consuming, non-biodegradable, unstable and have some safety problems compared to natural dye [9].

The effluents of different industries, using synthetic dyes, especially in textile industries, pollute air, agricultural soil and various water bodies, which are not only harmful for plants and animals but human beings as well. These are enlisted as the cause of mutation, different kinds of cancer, allergies, respiratory disorders, skin disorders and cell toxicity to all forms of life [10]. Long term exposure to synthetic dyes can cause various chronic diseases [11]. Almost 10–35% of synthetic dyes are lost from industries during the process of colorization of different components. Furthermore, in the scenario of reactive dye half of the initial dyes are present in the dye bath effluent [12]. These chemical dyes contain a variety of toxic chemicals including metals, insoluble substances, wastewater and carcinogens, which become part of our environment directly or indirectly [1]. A total of 1–2 million L water is used for staining of 50,000 m of silk staining on a daily basis [13]. The toxic wastewater removed from the industries becomes part of the soil and water bodies, which is harmful to all organisms including humans [14].

Due to health problems and environmental threats to humans, the use of synthetic dyes has gradually turned the attention of people and motivated researchers towards old natural dyes [15]. To overcome this problem, there is an urgent need for non-toxic, durable, biodegradable, non-carcinogenic, non-allergic, easily available, cheaper, environmentally and health-friendly solutions in the form of natural dyes for staining of food items, textiles, and garments [16]. The awareness about environmental conservation and ecofriendly solutions, the governments now implement strict legislation to use natural products instead of synthetic chemicals [17]. Therefore, various countries and some non-government organizations (NGOs) banned the use of chemical base dyes including the use of aromatic azo for staining of different products [18, 19]. On the other hand, natural dyes not only reduce toxicity and environmental pollution but also add many bioactive contributions such as antimicrobial, therapeutic, and UV protection, as well as increasing functional benefits like texture, taste and nutritional value of food products [20, 21]. The major sources of natural dyes are plants, insects, microorganisms, and mineral ores [22]. Microbial colorants are the preferred choice due to their stability, cost-effectiveness, high yield, independence from seasonal variations, ease of extraction, and time-efficient production [23]. Among pigments produced by microbes, carotenoids, melanin, flavins, quinines, monascins and violacein are the major secretions [24]. The rhizospheric soil and most other organic mediums are common sources for the isolation of rhizospheric fungi having the potential to produce different kinds of pigments as a metabolite [25]. Various groups of fungi are identified as having the potential to produce carotenoids, which increases the interest of scientists considering them as a natural dye [26].

The species of Trichoderma and Aspergillus isolated from different soil samples having potential to produce various pigments used for staining of silk fibbers and cotton [27]. Salt and water-soluble red pigment were extracted from entomopathogenic fungi Isaria farinosa, having good results for staining of textile [28]. Furthermore, various pigments are isolated from different fungal species including Fusarium verticillioides, Isaria farinosa, Monascus purpureus, Emericella nidulans, purpureus, Isariaspp, Emericella, and Fusarium [29, 30]. Various groups of filamentous fungi and some marine microbes are identified having potential to produce water-soluble pigments, owning broad spectrum ecological importance [31]. From the last two decades, the red pigments isolated from fungi gained much attention of the scientist because of their use in different industries including food, cosmetics and pharmaceutical as well as textile industries to increase their efficiency and aesthetic value [32, 33].

Plants and animal-based pigments have numerous limitations including solubility in water, instability, durability, and not available year-round [34]. On the other hand, microbial dyes are of great interest because of their stability, water solubility, and availability annually [1]. Moreover, microorganisms rapidly grow and use different organic waste as a raw material, which leads to high productivity in any season and also cleans the organic waste [35]. Moreover, microbial fermentation for obtaining desired pigment has some health benefits like the production of antioxidant, antimicrobial, and anticancer compounds in culture medium [36]. The main disadvantage of these natural dyes obtained from microbial sources is small quantity of pigments is extracted from a large culture source [37]. In the present study, we have carried out a fermentation-based process using the previously isolated rhizospheric fungal strain T. purpureogenus PH7, sourced from the rhizosphere of Parthenium hysterophorus, to produce a natural red dye. Conditions for fungal growth and dye production were carefully optimized to enhance yield. Additionally, a tailored extraction method was adopted for isolating the dye and exploring its in-vitro staining of cotton and other fabrics, demonstrating its potential as a natural dye.

Materials and methods

Requisition of rhizofungal strain

The previously isolated plant growth-promoting, phosphate solubilizing and Pb-alleviating fungal strain T. purpureogenus (accession number PQ281486), was selected from our microbial stock in the Plant Microbes Interaction (PMI) laboratory, Abdul Wali Khan University Mardan. The fungal strain T. purpureogenus PH7, was previously isolated from the rhizospheric soil of Parthenium hysterophorus plant from the area of District Dir lower Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan [38].

Spectrophotometric analysis of metabolites

The strain T. purpureogenus was screened for the production of different metabolites using known protocols [39]. Furthermore, 5 mm of inoculum from T. purpureogenus was inoculated into Czapek medium and incubated in shaking incubator at 121 rpm on 28 °C for 10 days. After proper incubation the fungal filtrate and biomass was separated through Whatman No 1 filter paper. To remove cell debries the culture filtrate was centrifuged at 3780 g for 30 min. Further the supernatant was processed for quantification of different metabolites. Moreover IAA was quantified through the protocols of [40], flavonoids using as per protocol of (M El Far and H Taie [41], phenolics (EA Ainsworth and KM Gillespie [42], lipids [43], proteins [44], sugar [45], and proline [46].

Optimization of growth of T. purpureogenus

To optimize the growth of T. purpureogenus, various environmental conditions were tested, including temperature, pH, salinity, chromium concentrations, and different carbon sources.

To check the effect of temperature, the T. purpureogenus was inoculated (5 mm disc) in flasks containing 100 mL Czapek medium each at sterilized conditions [47]. For each treatment, three replicates were taken, and the inoculated flasks were transferred to shaking incubator and exposed to increasing temperatures (8,12, 16, 20, 24 28, 32, and 38 °C). 3 flasks were taken as a control having only T. purpureogenus, incubated at 121 rpm on 28 °C for 10 days. After proper incubation, the biomass of T. purpureogenus was harvested and their fresh and dry weight were recorded (g/100 mL).

To check the effect of pH, the protocols of Z Chadni, MH Rahaman, I Jerin, K Hoque and MA Reza [47], was adopted. Furthermore, a 5 mm disc of T. purpureogenus was inoculated into Czapek medium, adjusted to different pH levels (5.0, 6.0, 7.0, 8.0, 9.0, and 10.0) using sodium hydroxide (NaOH) and hydrochloric acid (HCl). After 10 days of shaking incubation of the fungi at 121 rpm and 28 °C, the fungal biomass was filtered through Whatman No 1 filter paper and fresh and dry weights (g/100 mL) were recorded.

Effect of different source of carbon in the medium was determined using, the established protocol of lee et al. [48], where the isolate was grown on Czapek medium supplemented with various carbohydrate sources such as, dextrose, glucose, starch, or sucrose (2% each). The inoculated flasks were incubated in incubator at 121 rpm and 28 °C for 10 days. After the incubation period, fresh weights of all the samples were recorded to analyze their growth.

To determine the effect of chromium (Cr), the fungal isolate was sub-cultured in Czapek medium supplemented with various concentrations (0, 100, 200, 400, 600, or 800 µg/mL) of Cr [49]. The strain T. purpureogenus was inoculated in a 250 mL flask containing 100 mL of medium per flask, followed by incubation at 28 °C and 121 rpm for 10 days. After the incubation period, the fungal biomass was separated using Whatman No. 1 filter paper, and growth was recorded.

To assess the effect of salt stress on the strain T. purpureogenus, the strain was inoculated in Czapek medium supplemented with various concentrations (0-1000 ppm) of sodium chloride (NaCl). All the samples were incubated at 28 °C and 121 rpm for 10 days. After proper incubation, the growth of the fungal strain was monitored.

Optimization of dye production

To check the production of red dye under different environmental conditions including temperature, pH, different carbohydrate sources, salinity, and increasing concentration of Cr. For that T. purpureogenus was inoculated in 250 mL flask containing 100 mL of Czapek medium and incubated at 28 ℃ and 121 rpm for 10 days [50]. After 10 days of fungal growth, the biomass was filtered through Whatman No 1 filter paper. The culture filtrate was then thoroughly collected, and its optical density (OD) was measured at 520 nm to quantitatively analyze the production of dye under different conditions.

Extraction of dye

The isolate T. purpureogenus was sub-cultured in a 250 mL flask containing 100 mL of sterilized Czapek medium in shaking incubator for 14 days at 28 °C and 121 rpm. After 14 days of fungal incubation, both the fungal biomass and filtrate were incubated in a water bath at 98 °C for 1 h, followed by filtration through Whatman No 1 filter paper. The filtrate was then centrifuged at 10,000 g for 15 min to remove debries from the mixture [51].

Staining

For the purpose of staining, the procedure of [47], was adopted. The isolated dye was used to stain unscoured cotton fabric and processed cotton, which was purchased from the local market. Furthermore, 100 mL of dye was taken and thoroughly mixed with 10% of ferrous sulphate as a fixative chemical. For dyeing, 2 g of cotton fabric and cotton was immersed in selected mixture, followed by 3 h of incubation at room temperature.

After 3 h of incubation, the samples were first dried in the shade, then rinsed three times with tap water, and again dried in sunlight. To record quantitive absorption of the dye for both the fabric and cotton, the optical density of the processed mixture was measured using spectrophotometer at 520 nm. For the percentage absorption of the dye, the following formula was used.

|

1 |

Antioxidant assay

DPPH free radical scavenging activity

DPPH free Radical scavenging activity was determined using the method of L Meng, W Li, S Zhang, C Wu, W Jiang and C Sha [52]. Initially, the reaction mixture was prepared containing 2 mL of fungal culture filtrate and 2 mL of DPPH stock solution (0.04 mg/mL). The mixture was then incubated in dark for 30 min and the optical density was recorded at 517 nm against a blank containing methanol.

|

2 |

Further, AS illustrates the OD of the red dye in the DPPH stock solution, while AD shows the absorbance in the DPPH solution.

ABTS activity

The ABTS activity was determined by the procedure of M Sachadyn-Król, I Budziak-Wieczorek and I Jackowska [53]. Different concentrations (0.6–100 ppm) of the red dye in the form of culture filtrate were mixed with ABTS solution, followed by a 5-minute incubation at 28 °C. The optical density of 3 mL stock solution was measured at 734 nm against blank containing ascorbic acid.

Statistical analysis

All experiments were performed in triplicate. The data were recorded as the mean along with the standard error of the mean. To determine significance among the various groups, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Duncan’s multiple range test were performed using statistical software IBM SPSS Statistics v.26.0 at p ≤ 0.05. GraphPad Prism (Version 9) was used for plotting graphs.

Results

Production of plant benefiting metabolites by the strain T.purpureogenus

The strain T. purpureogenus produced significant quantity of metabolites in its culture filtrate. Further, in the culture filtrate of T. purpureogenus under control conditions, 0.96, 2.93, 32.8, 219, 13.6, and 198 µg/g of fresh biomass of phenols, IAA, flavonoids, sugar, lipids and protein were recorded, respectively (Table 1).

Table 1.

Metabolites profiling of T purpureogenus a rhizospheric fungal strain inoculated on Czapek medium for 7 days at 28 ℃ and 121 rpm. The data are mean of three replicates, labelled with different letter show significant difference from each other at (0.05)

| Serial No. | Metabolites | Quantity µg/L |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Phenol | 0.9612 ± 0.058a |

| 2 | IAA | 2.9320 ± 0.2082a |

| 3 | Flavonoids | 32.81 ± 0.0605c |

| 4 | Lipids | 13.63 ± 2.8b |

| 5 | Sugar | 219.16 ± 0.4841e |

| 6 | Protein | 198.321 ± 0.1941d |

Optimization of growth conditions

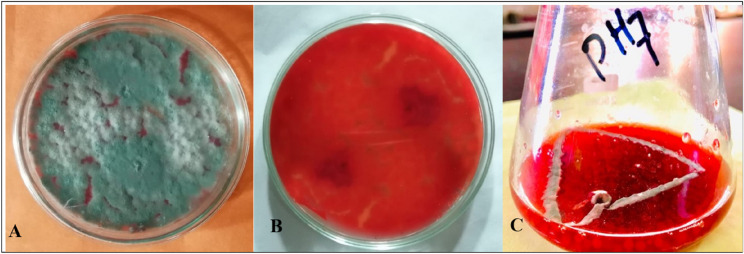

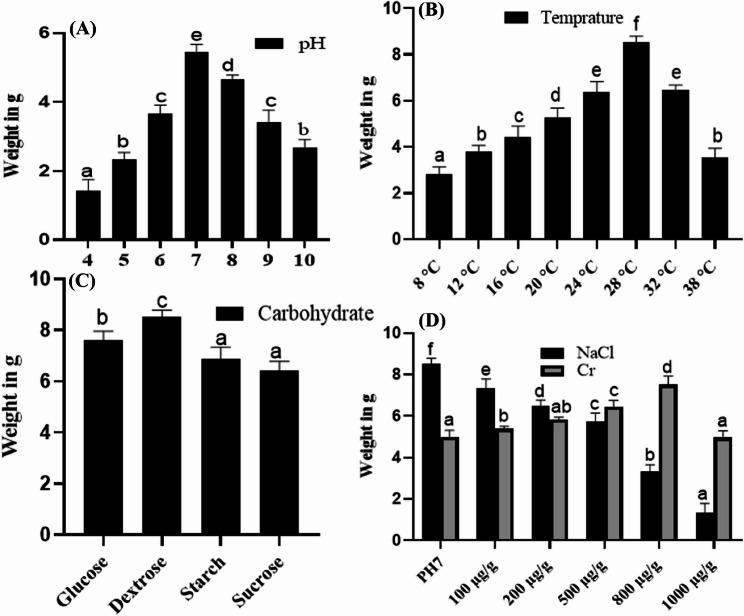

The fungal strain T. purpureogenus was refreshed from culture stock on potato dextrose agar (PDA) medium, with the topside is shown in Fig. 1A, flipside in Fig. 1B and in Czapek medium Fig. 1C, for various experimental purposes. The medium composition and various culture environments significantly (P < 0.05) increased the growth of the strain T. purpureogenus and the production of red dye. Among the physical and chemical factors, pH, temperature, NaCl concentration, metal toxicity and different carbohydrate sources significantly (P < 0.05) affected both biomass and red dye production. T. purpureogenus achieved maximum growth (5.3 g) in terms of biomass production at pH 7. It was observed that by increasing or decreasing pH from 7 the growth of fungi was significantly decreased (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 1.

The T purpureogenus grown on Potato Dextrose Agar medium is shown with upside in (A) and the flipside in (B), while fungal cultures in Czapek medium incubated for 7 days at 27 ℃ and 121 rpm are shown in (C)

Fig. 2.

The impact of various physicochemical parameters on the growth of T. purpureogenus. The effect of pH on mycelium growth is shown in (A), while the effects of temperature (B), different carbohydrate sources (C), and salt and chromium are depicted in (D). Bars represent the means of three replicates with standard errors, and different letters indicate significant differences among the groups at p ≤ 0.05

Furthermore, it was observed that T. purpureogenus growth was significantly higher at temperature of 28 °C, with the highest biomass of 8.5 g was recorded as compared to other temperature levels (Fig. 2B). Among the various tested carbohydrate sources, T. purpureogenus growth (8.5 g) on dextrose-supplemented medium was significantly higher, (Fig. 2C). Moreover, applying various concentrations of salt stress significantly inhibited the growth of T. purpureogenus.

The strain T. purpureogenus has also shown the ability to significantly alleviate Cr toxicity up to 800 µg/g. However, by increasing the concentration of Cr beyond 800 µg/g, the growth of the fungus decreased. A significantly higher value of 7.5 g was recorded in the fugal culture filtrate (CF) of T. purpureogenus at 800 ug/g of Cr stress. Conversely, the growth of T. purpureogenus was significantly reduced with increased concentrations of sodium chloride (NaCl) in a dose-dependent manner. The highest biomass of 8.5 g was recorded under control conditions, while the lowest value of 1.3 g was observed at 1000 µg/g of NaCl (Fig. 2D).

Optimization of dye production

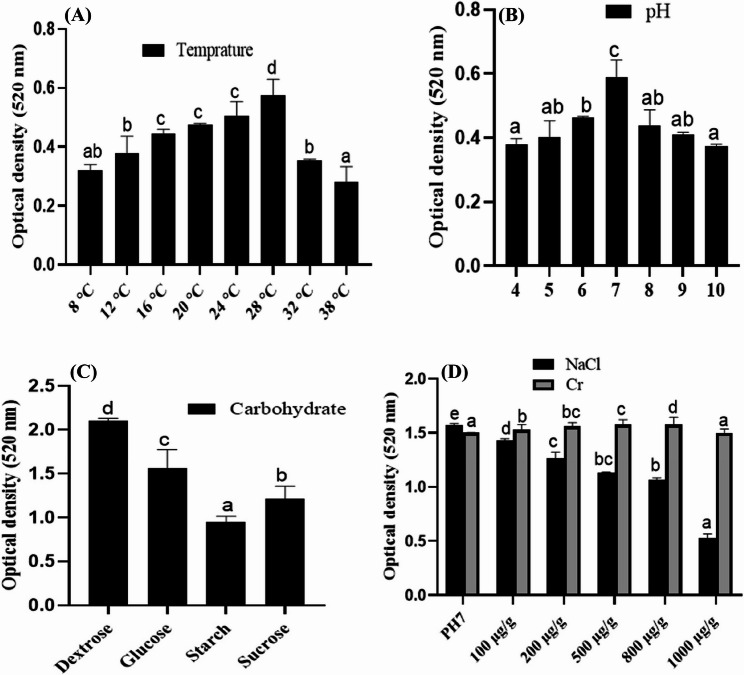

The production of red dye in Czapek medium by T. purpureogenus was analyzed at 520 nm through spectrophotometer. A significantly higher concentration of dye was found in the CF of T. purpureogenus incubated at temperature 28 °C, pH 7, in dextrose-supplemented Czapek medium having values of 0.57, 0.58 and 2.1 µg/mL, respectively (Fig. 3A-C). Furthermore, both increasing and decreasing the pH and temperature from their optimum values resulted in a significant decrease in dye production.

Fig. 3.

The effects of temperature (A), pH (B), different carbohydrate sources (C), and chromium and sodium chloride (D) on the production of red dye in the culture filtrate of T purpureogenus after sub culturing it in Czapek medium for 10 days at 28 °C and 121 rpm. Bars represent the means of three replicates with standard errors, and different letters indicate significant differences among the groups at p ≤ 0.05

In contrast, elevated concentrations of chromium (Cr) led to a significant increase in dye production in the medium, with the highest value of 1.57 µg/mL noted in the culture filtrate under maximum stress (800 µg/g). In contrast, the production of dye by T. purpureogenus significantly decreased in a dose-dependent manner with increasing concentrations of sodium chloride (NaCl). The highest value of 1.5 µg/mL was recorded under control conditions, while the lowest value of 0.5 was observed under the highest salt stress (Fig. 3D).

Staining of cotton fabrics and cotton

When the samples were dried in sunlight, it was observed that the fabrics absorbed more dye and displayed a shinier, better physical appearance compared to cotton. Furthermore, the dye absorption % for both the samples was higher, with the showing a 0.65% absorption value, compared to cotton’s 0.38% absorption (Table 2). This can be attributed to the fact that cotton retains some concentration of NaOH, which reduces the staining potential of the desired dye (Fig. 4).

Table 2.

Percentage absorption of red dye by cotton and cotton fabrics

| Treatments | Optical Density | % Absorption |

|---|---|---|

| OD of the mixture before treatment | 1.64 ± 0.020744d | - |

| OD of cotton mixture after treatment | 1.02 ± 0.5803412c | - |

| OD of fabrics mixture after treatment | 0.57 ±0.010440307ab | - |

| % Absorption by cotton | - | 0.38% ±0.10235a |

| % Absorption by fabrics | - | 0.65% ± 0.6453b |

Fig. 4.

Staining of cotton fabric and cotton was performed using the red dye extracted from T purpureogenus, which was sub cultured in Czapek medium for 10 days at 28 °C and 121 rpm

Antioxidant activity of red pigment

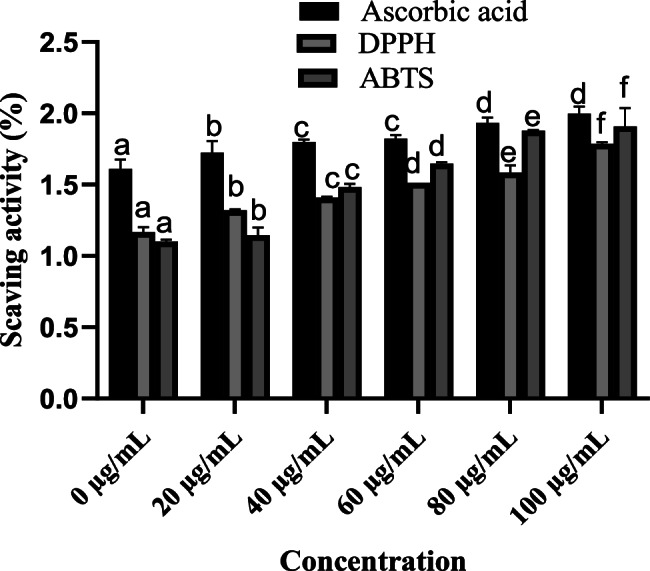

Both DPPH and ABTS assayactivity of red pigment showed that the radical scavenging activity of the red pigment was greater than that of ascorbic acid. At a concentration of 100 µg/mL, the red pigment exhibited 1.7% inhibition for DPPH and 2.0% inhibition for ABTS (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

The antioxidant activity of T. purpureogenus was measured using DPPH and ABTS assay. The strain was sub cultured in Czapek medium for 10 days at 28 ℃ and 121 rpm. Bars represent the means of three replicates, with standard errors labelled by various letters indicating significant differences from one another at p ≤ 0.05

Discussion

Globally, there are various challenges facing modern humanity. Among these, soil and water pollution has become a significant issue, which affects all forms of biodiversity through the use of contaminated products [54]. The main sources of water and soil contamination in agricultural sites are due to industrial effluents containing natural dyes and petrochemicals, which release many toxic substances during the manufacturing and application process [15, 55, 56]. In such scenario, eco-friendly natural dyes divert the attention of the people to use in various industries, including cosmetics, textile, pharmaceuticals and food [36, 54]. Their environmentally friendly, cost-effective, therapeutic, nutritional and sustainable nature make them an appealing alternative [57, 58].

In present study, the previously isolated strain T. purpureogenus was selected for the production of natural dye from our microbial culture stock known for its ability to alleviate metal toxicity, phosphate solubilization and production of various secondary metabolites and stress-related enzymes. The present study presents a novel and sustainable approach to isolating a natural red dye from rhizospheric fungi found in Pb-contaminated sites in district Dir lower, which can be used in the textile and food industries. There have been several previous studies on dye production and optimization by various groups of fungi. However, in our investigation, we observed variations in terms of various physical and chemical factors affecting both dye production and fungal growth. Additionally, the antioxidant potential and alleviation of metal toxicity are also explored in the present study.

The chemical composition and environmental factors such as pH, temperature, light intensity, salinity, metal toxicity are crucial for the growth and pigment production of T. purpureogenus. In the present research work, it was found that T. purpureogenus exhibited maximum growth and pigment production at a pH of 7 and a temperature of 28 °C. By altering pH and temperature from optimal values, the growth of fungi and production of pigment reduced significantly. For many Monascus species, the ideal temperature range for pigment production is between 30 and 37 °C [59]. According to R Kalra, XA Conlan and M Goel [60], the growth of fungi depend on several physical environmental factors, including light, temperature, pH, aeration and the nature of the medium. Similarly, A Méndez, C Pérez, JC Montañéz, G Martínez and CN Aguilar [61], reported that both temperature and pH play crucial roles in growth and pigment production, as the metabolic activities require suitable pH and temperature. The pH and temperature of the medium are essential for the production of metabolites during microbial fermentation [62]. Many Aspergillus species have shown to reduce pigment production under alkaline conditions. Our strain has the same potential of producing red dye at neutral pH and a temperature that are almost moderate for most of the organisms. The optimal pH and temperature values for pigment production have been recorded at 5 °C and 27 °C for various groups of fungi [63].

Four different modified Czapek growth media were tested at the shake flask level to find the most suitable medium for growth and red pigment production. The biomass production and spectrophotometric analysis indicated that the Czapek medium supplemented with dextrose was the most effective, followed by those containing glucose, sucrose and starch. Our finding suggests that a complex source of carbon such as potato starch in PDB favors pigment production, which is also reported by a number of other studies [64, 65].Our result are correlated with the result of [66, 67].

In the present research, it was observed that by exposing T. purpureogenus to increasing concentrations of salt stress significantly reduced both fungal growth and red pigment production. The extraction and optimization of red pigment from Talaromyces verruculosus also decreased when exposed to increasing concentrations of NaCl [47, 68]. This reduction occurs because salinity affects the metabolic process of the host, impacting the production of various secondary metabolites [69], particularly amino acids. Furthermore, increased salinity reduced the expression of genes that encode the biosynthesis of metabolites involved in staining. On the other hand, the selected fungal strain has the ability to alleviate Cr toxicity up to 800 µg/g. Moreover, as the metal concentration increases beyond 800 µg/g, both fungal growth and red dye production was reduced significantly. These findings show similarities with the result of [39], which indicated that A. niger PH1 can alleviate Pb-toxicity up to 800 µg/g in Czapek medium by producing secondary metabolites and stress related enzymes [54].

Moreover, the T. purpureogenus strain also produced significant concentrations of plant growth-promoting metabolites, as well as increased the antioxidant level. When the fungal inoculum is discharged into agriculture soil and water bodies, will result in plant growth promotion and alleviates various biotic and abiotic stresses [70–72]. These findings support the results of I Hussain, M Irshad, A Hussain, M Qadir, A Mehmood, M urrehman and N Khan [38], which recorded plant growth promotion under Pb stress by inoculating the strain T. purpureogenus.

The production of antioxidants was quantified using DPPH and ABTS assays, with various concentrations of ascorbic acid employed as a standard. For both the DPPH and ABTS assays, the radicle scavenging activity was found to be higher as compared to standard. These findings align with the result reported in [73], which documented the antioxidant activity of red pigment in terms of ABTS and DPPH activity.

The concentrated pigment was obtained by boiling the mycelium of T. purpureogenus along with culture filtrate in a water bath at 98 ℃. These results correlate with the findings of [28, 74], which suggest that fungal pigments become more concentrated when both the biomass and filtrate are boiled before being used for staining.

The dyeing procedure for cotton and fabrics was chosen based on the improved performance of the dyes when used in combination with a mordant [75]. After processing the samples, we observed that the selected dye demonstrated significant efficacy in dyeing unscoured fabrics and cotton. Additionally, it was noted that these red dyes are sensitive to alkaline conditions. Our findings correlate with those of [76], who used ferrous sulfate as a fixative and reported that unscoured fabrics produced brighter colors compared to scoured fabrics. This difference is likely due to the residual sodium hydroxide and surfactants in scoured fabrics, which can alter the dye’s effectiveness.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we analyzed the potential of T. purpureogenus PH7 to produce red dye and optimized the conditions for both dye production and fungal growth. The strain T. purpureogenus PH7 demonstrated optimal growth and dye production at pH 7, a temperature of 28 ℃, and in a dextrose-supplemented Czapek medium. Additionally, the strain showed an ability to alleviate Cr toxicity up to 800 ppm, though both growth and dye production significantly decreased as the salt concentration increased. The antioxidant potential of the strain was also assessed through DPPH and ABTS assays, with significant increases observed in antioxidant activity. For further exploration and commercialization of red natural dye, additional scientific studies are required. This study presents an alternative, cost-effective, durable, long-lasting, and environmentally friendly solution compared to synthetic dyes.

Acknowledgements

We are very thankful to the Ongoing Research Funding program, (ORF-2025-191), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Abbreviations

- PH7

Parthenium hysterophorus

- Cr

Chromium

- IAA

Indole-3-Acetic Acid

- DPPH

1,1-diphenyl-2 picrylhydrazyl

- ABTS

2,2-azobis (3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonate)

- µg

Microgram

- NGOs

Non-government organizations

- NaOH

Sodium hydroxide

- HCL

Hydrochloric acid

- OD

Optical density

- ANOVA

One-way analysis of variance

- PDA

Potato Dextrose Agar

- CF

Culture filtrate

Authors’ contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, data collection and original data analysis: I.H., M.I., A.H., M.R., and M.H.; validation, data presentation, visualization, writing, reviewing and editing of manuscript: S.A., M.I., A.F.A., M.H.A., A.Q., M.H., and M.S.; funding acquisition: S.A., M.H., M.H.A. and A.F.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Data availability

Availability of dataThe datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are submitted in the GenBank repository under accession number PQ281486.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The authors certify that no experiments involving human participants or animals models conducted in this study. Consent for publication.

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Muhammad Irshad, Email: muhammad.irshad@awkum.edu.pk.

Sajid Ali, Email: drsajid@yu.ac.kr.

References

- 1.Al-Tohamy R, Ali SS, Li F, Okasha KM, Mahmoud YA-G, Elsamahy T, et al. A critical review on the treatment of dye-containing wastewater: ecotoxicological and health concerns of textile dyes and possible remediation approaches for environmental safety. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2022;231:113160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Affat SS. Classifications, advantages, disadvantages, toxicity effects of natural and synthetic dyes: a review. Univ Thi-Qar J Sci. 2021;8(1):130–5. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sarkar SL, Saha P, Sultana N, Akter S. Exploring textile dye from microorganisms, an eco-friendly alternative. Microbiol Res J Int. 2017;18(3):1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vinha AF, Rodrigues F, Nunes MA, Oliveira MBP. Natural pigments and colorants in foods and beverages. Polyphenols: properties, recovery, and applications. Elsevier.2018. pp. 363–91. 10.1016/B978-0-12-813572-3.00011-7. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Venil CK, Yusof NZ, Aruldass CA, Ahmad W-A. Application of violet pigment from chromobacterium violaceum UTM5 in textile dyeing. Biologia. 2016;71(2):121–7. [Google Scholar]

- 6.AlAshkar A, Hassabo AG. Recent use of natural animal dyes in various field. J Text Color Polym Sci. 2021;18(2):191–210. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nagendrappa G. Sir William Henry perkin: the man and his ‘mauve.’ Resonance. 2010;15(9):779–93. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ahsan R, Masood A, Sherwani R, Khushbakhat H. Extraction and application of natural dyes on natural fibers: an eco-friendly perspective. Rev Educ Adm LAW. 2020;3(1):63–75. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sen T, Barrow CJ, Deshmukh SK. Microbial pigments in the food industry—challenges and the way forward. Front Nutr. 2019;6: 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khandare RV, Govindwar SP. Phytoremediation of textile dyes and effluents: current scenario and future prospects. Biotechnol Adv. 2015;33(8):1697–714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Olas B, Białecki J, Urbańska K, Bryś M. The effects of natural and synthetic blue dyes on human health: a review of current knowledge and therapeutic perspectives. Adv Nutr. 2021;12(6):2301–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rai U, Singh N, Upadhyay A, Verma S. Chromate tolerance and accumulation in chlorella vulgaris L.: role of antioxidant enzymes and biochemical changes in detoxification of metals. Bioresour Technol. 2013;136:604–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Islam MT, Islam T, Islam T, Repon MR. Synthetic dyes for textile colouration: process, factors and environmental impact. Text Leather Rev. 2022;5:327–73. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Islam T, Repon MR, Islam T, Sarwar Z, Rahman MM. Impact of textile dyes on health and ecosystem: a review of structure, causes, and potential solutions. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2023;30(4):9207–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fried R, Oprea I, Fleck K, Rudroff F. Biogenic colourants in the textile industry–a promising and sustainable alternative to synthetic dyes. Green Chem. 2022;24(1):13–35. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saxena S, Raja A, Arputharaj A. Challenges in sustainable wet processing of textiles. Textiles and clothing sustainability: sustainable textile chemical processes. 2017;43–79. 10.1007/978-981-10-2185-5_2. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rehman A, Farooq M, Lee D-J, Siddique KH. Sustainable agricultural practices for food security and ecosystem services. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2022;29(56):84076–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jiang S, Ren D, Wang Z, Zhang S, Zhang X, Chen W. Improved stability and promoted activity of laccase by one-pot encapsulation with Cu (PABA) nanoarchitectonics and its application for removal of Azo dyes. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2022;234: 113366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Raji Y, Nadi A, Chemchame Y, Mechnou I, Bouari AE, Cherkaoui O, et al. Eco-friendly extraction of flavonoids dyes from Moroccan (Reseda luteola L.), wool dyeing, and antibacterial effectiveness. Fibers Polym. 2023;24(3):1051–65. [Google Scholar]

- 20.El-Zawahry M, Shokry G, El-Khatib HS, Rashad HG. Eco-friendly dyeing using hematoxylin natural dye for pretreated cotton fabric to enhance its functional properties. Egypt J Chem. 2021;64(12):7135–45. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shafiq F, Siddique A, Pervez MN, Hassan MM, Naddeo V, Cai Y, et al. Extraction of natural dye from aerial parts of argy wormwood based on optimized Taguchi approach and functional finishing of cotton fabric. Materials. 2021;14(19):5850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bishal A, Ali KA, Ghosh S, Parua P, Bandyopadhyay B, Mondal S, et al. Natural dyes: its origin, categories and application on textile fabrics in brief. Eur Chem Bull. 2023;12(8):9780–802. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Salauddin Mia R, Haque MA, Shamim AM. Review on extraction and application of natural dyes. Text Leather Rev. 2021;4(4):218–33. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rizvi SF, Izhar SK, Habiba U, Bajpai A. Potential Microbial pigments. Microbial pigments. CRC. 2024. pp. 1–18. 10.1201/9781003353980. [Google Scholar]

- 25.dos Reis Celestino J, de Carvalho LE, da Paz Lima M, Lima AM, Ogusku MM, de Souza JVB. Bioprospecting of Amazon soil fungi with the potential for pigment production. Process Biochem. 2014;49(4):569–75. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lopes FC. Sources and industrial applications of fungal pigments. Fungal biotechnology. CRC. 2022. pp. 44–53. 10.1201/9781003248316. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Devi A, Archana KM, Bhavya PK, Anu-Appaiah KA. Non‐anthocyanin polyphenolic transformation by native yeast and bacteria co‐inoculation strategy during vinification. J Sci Food Agric. 2018;98(3):1162–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Velmurugan P, Kamala-Kannan S, Balachandar V, Lakshmanaperumalsamy P, Chae J-C, Oh B-T. Natural pigment extraction from five filamentous fungi for industrial applications and dyeing of leather. Carbohydr Polym. 2010;79(2):262–8. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Velmurugan R, Swaminathan M. An efficient nanostructured ZnO for dye sensitized degradation of reactive red 120 dye under solar light. Sol Energy Mater Sol Cells. 2011;95(3):942–50. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Indumathy K, Kannan K. Eco-benign fungal colorants: sources and applications in textiles. J Textile Inst. 2020. 10.1080/00405000.2019.1634973. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mishra RC, Kalra R, Dilawari R, Deshmukh SK, Barrow CJ, Goel M. Characterization of an endophytic strain talaromyces assiutensis, CPEF04 with evaluation of production medium for extracellular red pigments having antimicrobial and anticancer properties. Front Microbiol. 2021;12:665702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lagashetti AC, Dufossé L, Singh SK, Singh PN. Fungal pigments and their prospects in different industries. Microorganisms. 2019;7(12):604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Venil CK, Velmurugan P, Dufossé L, Renuka Devi P, Veera Ravi A. Fungal pigments: potential coloring compounds for wide ranging applications in textile dyeing. J Fungi. 2020;6(2): 68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gunasekaran S, Poorniammal R. Optimization of fermentation conditions for red pigment production from penicillium sp. under submerged cultivation. Afr J Biotechnol. 2008;7(12). 10.5897/AJB2008.000-5037. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Khalid A, Arshad M, Anjum M, Mahmood T, Dawson L. The anaerobic digestion of solid organic waste. Waste Manag. 2011;31(8):1737–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Di Salvo E, Lo Vecchio G, De Pasquale R, De Maria L, Tardugno R, Vadalà R, et al. Natural pigments production and their application in food, health and other industries. Nutrients. 2023;15(8):1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mansour R. Natural dyes and pigments: extraction and applications. Handb Renew Mater Color Finish. 2018;9:75–102. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hussain I, Irshad M, Hussain A, Qadir M, Mehmood A, urrehman M, et al. Enhancing phosphorus uptake and mitigating lead stress in maize using the rhizospheric fungus talaromyces purpureogenus PH7. CLEAN-Soil Air Water. 2025;53(2): e70006. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hussain I, Irshad M, Hussain A, Qadir M, Mehmood A, Rahman M, et al. Phosphate solubilizing Aspergillus niger PH1 ameliorates growth and alleviates lead stress in maize through improved photosynthetic and antioxidant response. BMC Plant Biol. 2024;24(1):642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mehmood A, Khan N, Irshad M, Hamayun M, Husna I, Javed A, et al. IAA producing endopytic fungus Fusariun oxysporum Wlw colonize maize roots and promoted maize growth under hydroponic condition. Eur J Exp Biol. 2018. 10.21767/2248-9215.100065. [Google Scholar]

- 41.El Far M, Taie H. Antioxidant activities, total anthocyanins, phenolics and flavonoids contents of some Sweetpotato genotypes under stress of different concentrations of sucrose and sorbitol. Aust J Basic Appl Sci. 2009;3(4):3609–16. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ainsworth EA, Gillespie KM. Estimation of total phenolic content and other oxidation substrates in plant tissues using folin–ciocalteu reagent. Nat Protoc. 2007;2(4):875–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lewis T, Nichols PD, McMeekin TA. Evaluation of extraction methods for recovery of fatty acids from lipid-producing microheterotrophs. J Microbiol Methods. 2000. 10.1016/S0167-7012(00)00217-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lowry OH, Rosebrough NJ, Farr AL, Randall RJ. Protein measurement with the folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem. 1951;193(1):265–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.DuBois M, Gilles KA, Hamilton JK, Rebers PA, Smith F. Colorimetric method for determination of sugars and related substances. Anal Chem. 1956;28(3):350–6. 10.1021/ac60111a017. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bates LS, Waldren RP, Teare ID. Rapid determination of free proline for water-stress studies. Plant Soil. 1973;39(1):205–7. 10.1007/BF00018060. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chadni Z, Rahaman MH, Jerin I, Hoque K, Reza MA. Extraction and optimisation of red pigment production as secondary metabolites from talaromyces verruculosus and its potential use in textile industries. Mycology. 2017;8(1):48–57. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lee M-H, Chao C-H, Lu M-K. Effect of carbohydrate-based media on the biomass, polysaccharides molecular weight distribution and sugar composition from Pycnoporus sanguineus. Biomass Bioenergy. 2012;47:37–43. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Valix M, Loon L. Adaptive tolerance behaviour of fungi in heavy metals. Miner Eng. 2003;16(3):193–8. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bouhri Y, Askun T, Tunca B, Deniz G, Aksoy SA, Mutlu M. The orange-red pigment from penicillium mallochii: pigment production, optimization, and pigment efficacy against glioblastoma cell lines. Biocatal Agric Biotechnol. 2020;23: 101451. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Keekan KK, Hallur S, Modi PK, Shastry RP. Antioxidant activity and role of culture condition in the optimization of red pigment production by talaromyces purpureogenus KKP through response surface methodology. Curr Microbiol. 2020;77(8):1780–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Meng L, Li W, Zhang S, Wu C, Jiang W, Sha C. Effect of different extra carbon sources on nitrogen loss control and the change of bacterial populations in sewage sludge composting. Ecol Eng. 2016;94:238–43. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sachadyn-Król M, Budziak-Wieczorek I, Jackowska I. The visibility of changes in the antioxidant compound profiles of strawberry and raspberry fruits subjected to different storage conditions using ATR-FTIR and chemometrics. Antioxidants. 2023;12(9):1719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Qadir M, Hussain A, Hamayun M, Shah M, Iqbal A, Murad W. Phytohormones producing rhizobacterium alleviates chromium toxicity in Helianthus annuus L. by reducing chromate uptake and strengthening antioxidant system. Chemosphere. 2020;258:127386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fang W, Zhou Y, Cheng M, Zhang L, Zhou T, Cen Q, et al. A review on modified red mud-based materials in removing organic dyes from wastewater: application, mechanisms and perspectives. J Mol Liq. 2024. 10.1016/j.molliq.2024.125171. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Herlihy JH, Long TA, McDowell JM. Iron homeostasis and plant immune responses: recent insights and translational implications. J Biol Chem. 2020;295(39):13444–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Adeel S, Anjum F, Zuber M, Hussaan M, Amin N, Ozomay M. Sustainable extraction of colourant from harmal seeds (Peganum harmala) for dyeing of bio-mordanted wool fabric. Sustainability. 2022;14(19):12226. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ahmed MA, Mohamed AA. A systematic review of layered double hydroxide-based materials for environmental remediation of heavy metals and dye pollutants. Inorg Chem Commun. 2023;148: 110325. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Agboyibor C, Kong W-B, Chen D, Zhang A-M, Niu S-Q. Monascus pigments production, composition, bioactivity and its application: a review. Biocatal Agric Biotechnol. 2018;16:433–47. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kalra R, Conlan XA, Goel M. Fungi as a potential source of pigments: harnessing filamentous fungi. Front Chem. 2020;8: 369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Méndez A, Pérez C, Montañéz JC, Martínez G, Aguilar CN. Red pigment production by Penicillium purpurogenum GH2 is influenced by pH and temperature. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B. 2011;12(12):961–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kumar M, Prakash S, Radha, Kumari N, Pundir A, Punia S, et al. Beneficial role of antioxidant secondary metabolites from medicinal plants in maintaining oral health. Antioxidants. 2021;10(7):1061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Akilandeswari P, Pradeep B. Aspergillus terreus kmbf1501 a potential pigment producer under submerged fermentation. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2017;9:38–43. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lebeau J, Venkatachalam M, Fouillaud M, Petit T, Vinale F, Dufossé L, et al. Production and new extraction method of polyketide red pigments produced by ascomycetous fungi from terrestrial and marine habitats. J Fungi. 2017;3(3): 34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Thiyam G, Dufossé L, Sharma AK. Characterization of talaromyces purpureogenus strain F extrolites and development of production medium for extracellular pigments enriched with antioxidant properties. Food Bioprod Process. 2020;124:143–58. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Arumugam G, Manjula P, Paari N. A review: anti diabetic medicinal plants used for diabetes mellitus. J Acute Dis. 2013;2(3):196–200. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Alam S, Abbas HK, Sulyok M, Khambhati VH, Okunowo WO, Shier WT. Pigment produced by Glycine-stimulated macrophomina phaseolina is a (–)-Botryodiplodin reaction product and the basis for an in-culture assay for (–)-Botryodiplodin production. Pathogens. 2022;11(3):280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Khan MA, Asaf S, Khan AL, Ullah I, Ali S, Kang S-M, et al. Alleviation of salt stress response in soybean plants with the endophytic bacterial isolate curtobacterium sp. SAK1. Ann Microbiol. 2019;69:797–808. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sunita K, Mishra I, Mishra J, Prakash J, Arora NK. Secondary metabolites from halotolerant plant growth promoting rhizobacteria for ameliorating salinity stress in plants. Front Microbiol. 2020;11:567768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zahoor M, Irshad M, Rahman H, Qasim M, Afridi SG, Qadir M, et al. Alleviation of heavy metal toxicity and phytostimulation of brassica Campestris L. by endophytic mucor sp. MHR-7. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2017;142:139–49. 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2017.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Qadir M, Iqbal A, Hussain A, Hussain A, Shah F, Yun B-W, et al. Exploring plant–bacterial symbiosis for eco-friendly agriculture and enhanced resilience. Int J Mol Sci. 2024. 10.3390/ijms252212198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Qadir M, Hussain A, Iqbal A, Shah F, Wu W, Cai H. Microbial utilization to nurture robust agroecosystems for food security. Agron. 2024;14(9):1891. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hulikere MM, Joshi CG, Ananda D, Poyya J, Nivya T. Antiangiogenic, wound healing and antioxidant activity of cladosporium cladosporioides (endophytic fungus) isolated from seaweed (sargassum wightii). Mycology. 2016;7(4):203–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kumar SNA, Ritesh SK, Sharmila G, Muthukumaran C. Extraction optimization and characterization of water soluble red purple pigment from floral bracts of Bougainvillea glabra. Arab J Chem. 2017;10:S2145–50. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Rosyida A, Masykuri M. Minimisation of pollution in the cotton fabric dyeing process with natural dyes by the selection of mordant type. Res J Text Appar. 2022;26(1):41–56. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Choudhury AKR. Fabric dyeing and printing. Textile and clothing design technology. CRC. 2017. pp. 281–332.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Availability of dataThe datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are submitted in the GenBank repository under accession number PQ281486.