Abstract

Introduction

Learning skills in a clinical setting is one of the most desirable methods of education in medical sciences. Using a surgical preference card is an effective method in the clinical education of operating room nursing students. The aim of this study was to determine the effect of an educational intervention using a surgical preference card on anxiety and clinical competence of operating room nursing students.

Materials and methods

This randomized and parallel-group clinical trial was conducted on 60 operating room nursing students between 2023 and 2024 in Iran. Participants were selected using the available (consecutive) method and were allocated to two groups: preference card training (n = 30) and control (n = 30) using a four-block method. The intervention involved using preference cards to teach care before, during, and after common general surgeries, and it was conducted in two one-hour sessions. The primary outcome was clinical competence, and the secondary outcome was anxiety. The Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) and the Perceived Perioperative Clinical Competence Scale (PPCS-R) were used to collect data at two stages: before and two weeks after the intervention. Data were analyzed using descriptive and inferential statistics through SPSS software, version 20. Multiple linear regression, paired t-tests, and independent t-tests were used to analyze the data.

Results

At baseline, there were no significant differences between the two groups in terms of mean scores of state and trait anxiety and clinical competence (p > 0.05). The results of the multiple linear regression, which took into account the anxiety scores before the intervention and adjusted for their effects, showed a significant difference between the scores of state anxiety (p = 0.019) and trait anxiety (p = 0.005) in the intervention and control groups. Additionally, the mean clinical competence score after the intervention was 12.83 units higher in the intervention group than in the control group, which was significant compared to the pre-intervention score (p < 0.001).

Conclusion

According to the findings of the present study, educational centers and universities can use the surgical preference card as a valuable educational tool to manage students’ anxiety and enhance their proficiency in performing clinical skills in the operating room.

Keywords: Surgical preference card, Anxiety, Clinical competence, Operating room nursing, General surgeries

Introduction

Nowadays, learning skills in a clinical setting is one of the most desirable methods of teaching medical and therapeutic sciences [1, 2]. These teaching methods help students to use theoretical knowledge as a foundation for learning practical skills in interaction with the tutor and the clinical learning environment [3]. The operating room is recognized as the most important clinical training environment for operating room nursing students [4]. In this environment, students learn how to maintain patient safety, develop clinical skills related to pre-, intra-, and post-operative care, and teamwork skills in both critical and non-critical situations [5]. Training in such an environment faces numerous challenges due to the diversity of surgical procedures, environmental and occupational hazards, overcrowding, and the presence of complex technologies [6]. These challenges can affect students’ learning process and, as a result, jeopardize the scientific and practical competence of students as future workforce [7]. Researchers have identified anxiety as one of these challenges [8, 9].

Anxiety is the feeling of fear and worry that people experience when faced with a risky situation, leading to symptoms such as increased heart rate, sweating, dizziness, weakness, and indigestion [10, 11]. According to operating room nursing students, this anxiety is mainly caused by the unfamiliar environment and issues, high workload, performing sensitive care procedures for patients, and the possibility of not achieving future educational goals [9, 12, 13]. One of the most common causes of anxiety in students is the feeling of inadequate learning during their education. They feel that they have not acquired the necessary scientific and clinical competence to become a nurse as they should [9]. Researchers have also reached a similar conclusion that most graduates in this field do not have the necessary clinical skills and competence [14].

Clinical competence is defined as the integration of knowledge, skills, and attitudes necessary for effective patient care [15]. Some researchers also define clinical competence as the ability, knowledge, talent, and skill that enables nurses to make informed decisions in their clinical settings [16]. According to the Association of Perioperative Registered Nurses, clinical competence for operating room nurses means the ability to apply knowledge and skills in the operating room to care for patients before, during, and after surgery [17]. Factors such as work experience, communication, a supportive work environment, and the methods used in clinical education affect nurses’ clinical competence [15, 18]. Various methods, including simulation, peer teaching, problem-solving skills training, and virtual reality, have been used to improve the clinical education level of operating room nursing students [13, 19].

One of the educational methods in the operating room is the use of surgical preference cards (SPCs) [20]. A surgical preference card is a useful guide for operating room personnel that provides specific supplies required by the surgeon to perform procedures [21]. Information included in this card may consist of the surgical position, necessary drugs and solutions, equipment, supplies, instruments, sutures, and the preferred type of surgical dressing by the surgeon [22]. The use of this tool allows for better planning and resource allocation in the operating room, which is especially beneficial for students who are still learning the complexities of surgery and helps them avoid confusion [23]. Researchers have found that the use of surgical preference cards can significantly improve the self-efficacy of operating room nursing students [24]. However, despite the numerous advantages, preference cards are often not well-maintained, updated, or used, leading to inefficiencies in nursing care related to surgery [25].

Using surgical preference cards, similar to a roadmap, to establish a clear understanding of the various stages of surgery in the student’s mind can potentially decrease their anxiety levels and enhance their clinical efficiency. Due to the lack of research in this area, this study was conducted to determine the impact of an educational intervention utilizing surgical preference cards on the anxiety and clinical competence of operating room nursing students.

Materials and methods

Design and purpose

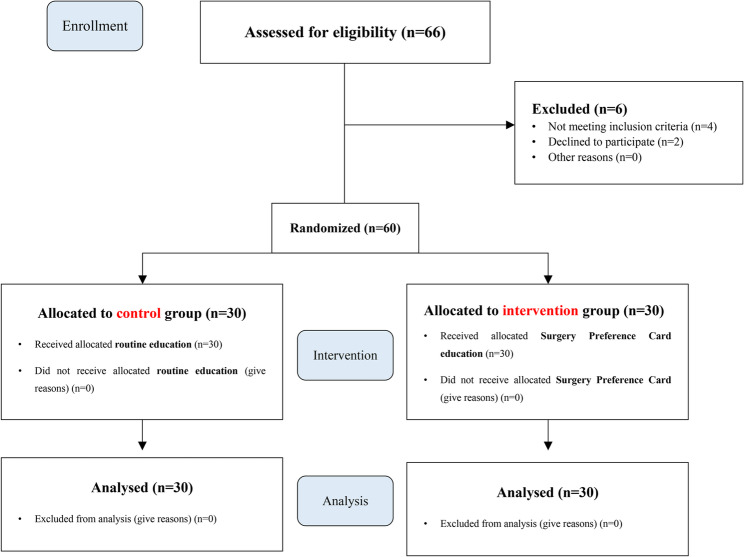

A parallel-group randomized controlled trial with a pre-test, post-test was conducted to determine the effect of an educational intervention using surgical preference cards on anxiety and clinical competence among operating room nursing students at Shahroud University of Medical Sciences in Iran. The study process is presented in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

The process of the study according to the CONSORT flow diagram (2010)

Participants

The study population included all fourth, sixth, and eighth-semester operating room nursing students at Shahroud University of Medical Sciences. A total of 66 individuals were assessed for eligibility. Among them, 4 participants were excluded because they did not meet the inclusion criteria, and 2 were unable to participate in the study. Consequently, 60 students were selected for the study between September 2023 and January 2024 using a convenience sampling method. The simplicity of implementation and the widespread use of convenience sampling in similar studies were noted as the rationale for selecting this approach [26].

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria consisted of undergraduate nursing students in the fourth, sixth, and eighth semesters of the operating room nursing program. These students had to provide full consent to participate in the study and had no previous experience working in the operating room or completing related training courses. Since second-semester operating room nursing students did not have specialized operating room internships, the study population was limited to fourth, sixth, and eighth-semester operating room nursing students.

Exclusion criteria encompassed missing training sessions and evaluations, opting out of study participation, and transferring to other faculties or universities during the study.

Sample size

The sample size was calculated using the following formula based on the mean and standard deviation of anxiety scores reported in a similar study [27] (42.36 ± 11.10 in the control group and 33.19 ± 9.22 in the intervention group). Considering a significance level of α = 0.05 and a power of 80%, the required sample size was estimated to be 24 participants per group. However, to account for potential attrition and to enhance the robustness of the study results, the sample size was increased to 30 participants per group, resulting in a total of 60 participants.

|

Intervention

After obtaining the necessary approvals from the Vice Chancellor for Research and Technology and the Research Ethics Committee of Shahroud University of Medical Sciences, the required coordination was established with the School of Allied Medical Sciences and operating rooms of two hospitals affiliated with this university. Subsequently, the researcher attended the mentioned environment and, while introducing themselves, explained the research objectives to each participant individually. Eligible individuals who verbally expressed their informed consent and completed a written consent form to participate in the study were included in the study using a convenience sampling method. They were then randomly assigned to either the intervention or control group using a block randomization of four (Fig. 1). Given the nature of the intervention, it was not possible to blind the study participants or data collectors. To blind the data analyst, the type of intervention was labeled as A and B, without revealing the specific assignment of individuals to the two groups.

In the pre-test phase, all participants were asked to complete a demographic data checklist, the Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory, and the Perceived Clinical Competence Scale – Revised (PPCS-R) at their leisure.

The educational intervention for the intervention group in this study included training on the necessary preparations for assuming the roles of scrub and circulating nurses in general surgeries using surgical preference cards. Specifically, during the students’ clinical practice hours in the operating room, the necessary preparations for participating in general surgeries (cholecystectomy, appendectomy, inguinal hernia, and laparotomy) were taught step by step in the pre-, intra-, and post-operative phases using surgical preference cards in two 1-hour training sessions. The cards were provided to the students to use the information contained therein. The preference cards included information related to patient prep and drape, patient positioning, type of surgical incision, instruments, equipment, necessary sutures, type of suturing technique, and an explanation of the surgical procedure. These items were not the same for all surgeons, as each surgeon had their own preferences in selecting these items. Therefore, before starting the interventions, the research team extracted the preferences of each surgeon through face-to-face interviews with three general surgeons stationed in the relevant hospitals. Using the available scientific resources in the operating room technology field and content validity confirmation by 12 surgeons and faculty members of the operating room and nursing department, the content of the preference cards was prepared and compiled. An example of the surgical preference card used in the study can be seen in Table 1.

Table 1.

A sample surgical preference card for open cholecystectomy surgery

| Surgical position | o Supine |

|---|---|

| Prep and Drape type |

o Prep: Disinfection begins at the incision site and continues to under the breast (above), the upper half of the abdomen (below), the right side of the body (right side), and the left half of the chest (left side). o Drape: Using four small sheet, two long sheet, and one perforated sheet, we expose the right subcostal area of the patient’s body. |

| Required surgical instrument |

o Surgical sheet and gown package o Cholecystectomy set or general set |

| Type of surgical incision | o Right subcostal or Kocher surgical incision |

| Required equipment |

o Electrosurgery device o Suction device |

| Required supplies |

o Povidone iodine 10% o 0.9% sodium chloride solution for washing inside the wound o Surgical scalpel blade 10 o Monopolar electrosurgery pen with dispersive electrode o Sterile surgical gloves o Sterile suction tube o Surgicel (for control liver bleeding) o Needle-free silk suture for gallbladder ligation (Size 0) o Nylon suture for fascia (Size 1 with round needle) o Vicryl suture for subcutaneous layer (Size 2 − 0 with sharp needle) o Nylon suture (Size 3 − 0 with sharp needle) or Monocryl suture (Size 2 − 0 with sharp needle) for skin o Nelaton tube or corrugated drain for fluid drainage o Pathology specimen container |

| Type of skin suture | o Continuous subcutaneous |

| Dressing type | o Simple dressing |

| Other orders | o Preparing pathology specimen form and container |

In the control group, the training was conducted as usual in the form of lectures in two 1-hour sessions. To prevent bias, the training for both groups was conducted by the same person. Additionally, in order to prevent information leakage, training for the intervention and control groups was conducted at separate times and locations. In the post-test, two weeks after the end of the interventions, students’ anxiety and clinical competence were measured again.

Measurements

Demographic characteristics checklist

This form includes information on gender, age, marital status, Grade Point Average (GPA), concurrent employment with studies, history of specific diseases, and medication use.

State-trait anxiety inventory (STAI)

This tool, developed by Spielberger in 1970, consists of 40 questions. Questions 1–20 assess state anxiety, while questions 21–40 assess trait anxiety. State anxiety items are rated on a 4-point Likert scale, with options ranging from “not at all” to “very much.” Trait anxiety items are also rated on a 4-point Likert scale, with options ranging from “almost never” to “almost always.” The final score yields two separate scores: one for state anxiety and one for trait anxiety. Each individual can score between 20 and 80 on each type of anxiety [28–30]. To score the scale, each item is assigned a value from 1 to 4. Some items ([1, 2, 5, 8, 10, 11, 15, 16, 19–21, 23, 26, 27, 30–33 and 34]) that indicate the absence of anxiety are reverse-scored. After obtaining the anxiety score for each subscale, the interpretation is as follows: mild anxiety (scores 21–39), moderate anxiety (scores 40–59), and severe anxiety (scores 60–80) [35]. Spielberger et al. reported Cronbach’s alpha values of 0.92 for the state anxiety subscale and 0.90 for the trait anxiety subscale. The test-retest reliability was 0.62 for the state anxiety subscale and 0.68 for the trait anxiety subscale [30]. Additionally, a study found a Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.79 between the state and trait anxiety subscales. Pearson correlation coefficients ranged from 0.75 to 0.98 for individual items, and were 0.96 for state anxiety and 0.98 for trait anxiety [36]. In the Persian version of the Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory, the Cronbach’s alpha was 0.886 for trait anxiety and 0.846 for state anxiety. Test-retest reliability was 0.765 for trait anxiety and 0.62 for state anxiety. The reliability coefficient for items 1–20 (state anxiety) was 0.889, and for items 21–40 (trait anxiety) it was 0.854 [31].

The perceived perioperative competence Scale-Revised (PPCS-R)

The PPCS-R scale, developed by Gillespie and Hamlin in 2009 and revised in 2012, is designed to evaluate the clinical competence of operating room students [32, 37]. It has been translated into multiple languages, with various versions showing confirmed validity and reliability. The Persian version of the PPCS-R was translated and adapted by Mirbagher Ajorpaz et al., demonstrating satisfactory psychometric properties. The Content Validity Index (CVI) for all items exceeded 0.9, with mean scores of 0.95 for relevance, 0.93 for clarity, and 0.95 for simplicity. During exploratory factor analysis, 7 items were eliminated, and the remaining items were grouped into a 5-factor model, explaining 63.1% of the total variance. The scale was confirmed with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.86 and an Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC) of 0.85. The Persian version of the PPCS-R consists of 33 items rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The tool comprises five factors: fundamental skills and knowledge (7 items; score 7–35), leadership (9 items; score 9–45), teamwork (7 items; score 7–35), skill (4 items; score 4–20), and professional development (6 items; score 6–30). The total score ranges from 33 to 165. A higher score indicates a higher level of clinical competence, and there is no definitive cut-off score for the construct [33].

Ethical considerations

This study has been approved by the Ethics Committee of Shahroud University of Medical Sciences with the code IR.SHMU.REC.1402.096. The study protocol has also been registered in the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials (IRCT) with the code IRCT20230913059423N1. Moreover, this protocol is in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, which includes explaining the study objectives, obtaining informed consent from the study participants, emphasizing the voluntary nature of participation, ensuring the right to withdraw from the study, assuring no harm from answering questions, and providing results upon request. Additionally, the authors adhered to the principles of the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) in publishing their findings. This research was conducted following the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) guidelines.

Statistical analysis

Data was analyzed using SPSS version 20. Descriptive statistics, including frequency and percentage for categorical variables, and mean and standard deviation for continuous variables, were used to categorize and summarize the data. Before the intervention, the two groups were compared in terms of qualitative demographic variables (such as gender and marital status) and quantitative variables (such as age and GPA) using the Chi-square and independent-samples t-tests. Additionally, the independent-samples t-test was used to compare dependent variables (anxiety and clinical competence) between the two groups after the intervention. The paired-samples t-test was used to compare each of the dependent variables before and after the intervention. Multiple linear regression was used to examine the factors influencing the mean scores of state-trait anxiety and clinical competence of the participants. The level of significance was set at 0.05 in all tests.

Results

The present study revealed that the mean age in the intervention group was 22.33 (SD = 1.21) years, while in the control group it was 22.60 (SD = 1.22) years. Most participants in both groups were single women. There were no significant differences between the two groups in terms of demographic characteristics, indicating that the groups were homogeneous in this regard (p > 0.05). Further details are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Demographic characteristics of participants

| Variables | Groups | P-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention | Control | ||||

| n (%) | n (%) | ||||

| Gender | Male | 8 (26.7) | 11 (36.7) | 0.405a | |

| Female | 22 (73.3) | 19 (63.3) | |||

| Marital status | Married | 0 (0) | 2 (6.7) | 0.150a | |

| Single | 30 (100) | 28 (93.3) | |||

| Employment combined with education | Yes | 6 (20) | 8 (26.7) | 0.542a | |

| No | 24 (80) | 22 (73.3) | |||

| History of specific disease | Yes | 3 (10) | 1 (3.3) | 0.301a | |

| No | 27 (90) | 29 (96.7) | |||

| Taking medication | Yes | 3 (10) | 1 (3.3) | 0.301 a | |

| No | 27 (90) | 29 (96.7) | |||

| Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | ||||

| Age (year) | 22.33 ± 1.21 | 22.60 ± 1.22 | 0.399b | ||

| Grade point average | 17.03 ± 1.36 | 16.59 ± 1.34 | 0.207b | ||

n: Frequency; %: Percent; SD: Standard deviation

a: Chi-squared test

b: Independent t test

Anxiety

Based on the results presented in Table 3, there was no significant difference between the two groups in terms of mean scores of state and trait anxiety before the intervention (p = 0.709 and p = 0.797, respectively). However, after the intervention, the mean scores of state and trait anxiety in the intervention group were significantly lower than in the control group (p = 0.031 and p = 0.030, respectively). Although there was a decrease in mean state and trait anxiety scores in both groups, this decrease was statistically significant in the intervention group (p < 0.001), while the decrease in the control group was not statistically significant (p = 0.180 and p = 0.623, respectively).

Table 3.

Comparison of state and trait anxiety levels in study groups

| Variables | Groups | Intergroup test results | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention (n = 30) | Control (n = 30) | |||

| Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | |||

| State Anxiety | Pre-intervention | 49.27 ± 8.45 | 48.47 ± 8.9 | P = 0.709a, t = 0.37 |

| Post-intervention | 41.17 ± 8.27 | 46.53 ± 10.39 | P = 0.031a, t = 2.12 | |

| Mean Differences | −8.10 ± 4.94 | −1.93 ± 7.70 | P < 0.001a, t = 3.68 | |

| Intragroup test results |

P < 0.001b t = 8.97 |

P = 0.180b t = 1.37 |

||

| Trait Anxiety | Pre-intervention | 46.23 ± 8.05 | 45.67 ± 8.91 | P = 0.797a, t = 0.25 |

| Post-intervention | 40.03 ± 7.43 | 45.13 ± 10.12 | P = 0.030a, t = 2.22 | |

| Mean Differences | −6.20 ± 3.90 | −0.53 ± 5.87 | P < 0.001a, t = 4.40 | |

| Intragroup test results |

P < 0.001b t = 8.69 |

P = 0.623b t = 0.49 |

||

n: Frequency; P: P-value; SD: Standard deviation

a: Independent t test

b: Paired t-test

Clinical competence

Based on the results of the assessment of participants’ clinical competence, there was no significant difference between the two groups in terms of mean clinical competence scores before the intervention (p = 0.095). Following the surgical preference card training, although the mean clinical competence score was higher in the intervention group compared to the control group, this difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.076). In an intragroup comparison, the mean clinical competence score of the control group participants decreased very slightly after the intervention (p = 0.196). However, in the intervention group, we observed a significant increase in the mean clinical competence score after the surgical preference card training, which was statistically significant (p < 0.001). Further details can be found in Table 4.

Table 4.

Comparison of mean clinical competence scores in study groups

| Variables | Groups | Intergroup test results | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention (n = 30) | Control (n = 30) | |||

| Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | |||

| Clinical Competence | Pre-intervention | 115.30 ± 14.68 | 122.07 ± 16.15 | P = 0.095a, t = 1.69 |

| Post-intervention | 127.27 ± 11.77 | 120.30 ± 17.57 | P = 0.076a, t = 1.80 | |

| Mean Differences | 11.96 ± 6.59 | −1.76 ± 7.30 | P < 0.001a, t = 7.64 | |

| Intragroup test results |

P < 0.001b t = 9.94 |

P = 0.196b t = 1.32 |

||

n: Frequency; P: P-value; SD: Standard deviation

a: Independent t test

b: Paired t-test

To examine the factors influencing the mean scores of state-trait anxiety and clinical competence of the participants, multiple linear regression was used. The results of this analysis showed that the mean pre-intervention state anxiety score and the group variable significantly affected the mean post-intervention state anxiety score. Specifically, after the intervention, the mean state anxiety score in the intervention group was 0.27 units lower than the control group, which was significant after controlling for the pre-intervention score (P = 0.019). Similarly, the mean pre-intervention trait anxiety score and the group variable significantly affected the mean post-intervention trait anxiety score. Accordingly, after the intervention, the mean trait anxiety score in the intervention group was 0.25 units lower than the control group, which was significant after controlling for the pre-intervention score (P = 0.005). In addition, multiple linear regression showed that the mean pre-intervention clinical competence score and the group variable significantly affected the mean post-intervention clinical competence score. Thus, the mean clinical competence score after the intervention was 12.83 units higher in the intervention group compared to the control group, and this difference was significant after controlling for the pre-intervention score (P < 0.001). For more details, refer to Table 5.

Table 5.

The effect of training with surgical preference cards on students’ anxiety and clinical competence after eliminating the effect of pre-test mean scores

| Variables | β | SE | t | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| State Anxiety | Constant value | 0.70 | 0.26 | 2.69 | 0.009 | |

| Mean score of before intervention | 0.60 | 0.12 | 4.77 | < 0.001 | ||

| Group | Control | ref | ||||

| Intervention | −0.27 | 0.11 | 2.40 | 0.019 | ||

| Trait Anxiety | Constant value | 0.401 | 0.175 | 2.286 | 0.026 | |

| Mean score of before intervention | 0.826 | 0.095 | 8.719 | < 0.001 | ||

| Group | Control | ref | ||||

| Intervention | −0.255 | 0.087 | −2.921 | 0.005 | ||

| Clinical Competence | Constant value | 14.369 | 7.074 | 2.031 | 0.047 | |

| Mean score of before intervention | 0.868 | 0.057 | 15.204 | < 0.001 | ||

| Group | Control | ref | ||||

| Intervention | 12.839 | 1.775 | 7.232 | < 0.001 | ||

SE Standard error

Discussion

The present study aimed to determine the effect of an educational intervention using surgical preference cards on anxiety and clinical competence among operating room nursing students in general surgeries. The results of this study showed that training using surgical preference cards significantly reduced state and trait anxiety and improved clinical competence in the participants. Consistent with the present study, Zarei et al. found in their study that the use of surgical preference cards could enhance clinical self-efficacy among students [24]. The findings of the present study are also in line with the results of a similar study that confirmed the effect of simulation-based suturing training on reducing anxiety and improving students’ skills [38]. According to researchers, students’ anxiety in clinical settings is mainly due to the competitive and complex nature of clinical education [39]. Preference cards can help students out of confusion in such a situation by providing necessary information [23].

The findings of the present study indicate that the mean scores of state and trait anxiety were significantly lower in the intervention group compared to the control group after the intervention. These results are consistent with the findings of the study by Adarvishi et al., where it was shown that problem-solving skills training could significantly reduce students’ anxiety levels and increase their efficiency [34]. Additionally, Kachaturoff et al. found in their study that peer teaching could play an effective role in reducing stress and anxiety levels among nursing students [40]. According to Dalvand et al., a cognitive training program and Jacobson’s relaxation technique can be effective in reducing students’ anxiety and enhancing their resilience in the operating room [41]. Although trait anxiety is generally regarded as a relatively stable personality characteristic, the significant reduction observed in the intervention group may be attributed to multiple factors. First, the educational intervention using surgery preference cards may have increased students’ sense of preparedness, self-efficacy, and perceived control in the clinical environment, which are known to modulate anxiety levels. Second, given the close timing of the pre- and post-tests, students’ responses might have been influenced by their most recent clinical experiences rather than their enduring personality traits. Some researchers have also noted that short-term changes in trait anxiety scores can occur in specific populations under educational or psychological interventions that strongly impact perceived competence or emotional stability [42–44].

One possible explanation for the reduction in anxiety observed among students in the intervention group is the structured and predictable nature of the surgery preference cards. By clearly outlining the necessary instruments, steps, and responsibilities before, during, and after surgery, SPCs help reduce ambiguity and uncertainty, which are known contributors to anxiety in clinical environments. Providing students with a clear roadmap of surgical procedures may enhance their sense of preparedness and control, which are associated with lower levels of performance-related stress. Researchers have also emphasized that greater knowledge leads to a decrease in fear of the unknown and consequently, a reduction in anxiety [45]. Similarly, a study by Ebrahimian et al. demonstrated that training in a simulated operating room significantly reduced students’ anxiety [46]. Therefore, the findings of this study reaffirm the importance of providing targeted training to manage student anxiety.

Although a significant improvement was observed in the mean clinical competence score within the intervention group after the intervention, the between-group difference did not reach statistical significance. This apparent paradox may be due to the relatively small sample size or the short duration of the intervention, which might have limited the statistical power to detect significant differences between the groups. Consistent with this study, Katebi et al. also demonstrated that the use of portfolios as a teaching tool could improve nursing students’ clinical competence from their own perspective, but this improvement was not statistically significant. However, students’ clinical competence, as perceived by their instructors, showed a significant improvement [47]. The lack of a significant difference may be due to a limited sample size or a short intervention duration. Previous research has also indicated that continuous and long-term training is necessary for a greater impact on clinical competence [48]. Mirbagher Ajorpaz et al. demonstrated in their study that the use of mentoring as a teaching technique could significantly increase the level of clinical competence among operating room nursing students [49]. Furthermore, Ghasemi et al. found in their study that the use of both task-based and team-based teaching methods could enhance the clinical competence of operating room nursing students. However, the improvement achieved in the task-based group was significantly greater than in the other group [50].

The results of the multiple linear regression analysis further highlight the importance of controlling for pre-test variables. The significant effect of the group on anxiety and clinical competence scores, after adjusting for the effects of the pre-test, indicates that the educational intervention using surgical preference cards was able to independently influence these variables, leading to a reduction in anxiety and an improvement in clinical competence among students. The results of the present study are partially consistent with those of Ghasembandi et al. [20], who reported that the use of surgical preference cards significantly improved the clinical performance of operating room nursing students. However, their study was limited to laparoscopic procedures and did not assess students’ anxiety or use standardized tools for evaluating clinical competence. In contrast, our study not only demonstrated improvements in clinical competence across a broader range of general surgeries, but also showed a significant reduction in students’ anxiety levels. These findings suggest that surgical preference cards may have both cognitive and emotional benefits in clinical education when implemented in a structured and comprehensive manner. Additionally, Zarei et al. found that the use of preference cards could significantly enhance the clinical self-efficacy of operating room nursing students [24].

Despite the positive effects of surgery preference cards on reducing anxiety and enhancing clinical competence, there are known challenges in their implementation. Previous studies, including Huntley et al.‘s study [25], have highlighted barriers such as the need for regular updates to ensure the accuracy of cards, as surgical techniques and instrument preferences may change over time. Additionally, the successful use of SPCs depends on the support and cooperation of the surgical team, particularly surgeons. In some cases, reluctance from surgeons or lack of awareness regarding the educational value of SPCs may hinder their effective use. These implementation challenges should be considered in future research and program planning to maximize the benefits of this educational tool.

As mentioned, the effects of various interventions such as simulation [38], problem-solving skills training [34], peer education [40], relaxation techniques [41], mentoring [49], and portfolio [47], on the anxiety and clinical competence of students have recently been investigated. However, there are very few studies on the use of surgical preference cards as an educational tool [20, 24], and educational interventions using this tool provide researchers with a new approach. Overall, the findings of this research indicate that the use of educational tools such as surgical preference cards can be employed as an effective strategy to reduce anxiety and enhance clinical competence among students in general surgery.

Strengths and limitations

The focus of this study was on the use of surgical preference cards for training operating room nursing students, an area that has been less explored in previous studies. Given the increasing number of surgeries worldwide and the critical role of operating room nurses in these surgeries, implementing educational interventions to enhance the clinical competence and reduce anxiety of students is of significant importance. One limitation of this study was the use of self-report measures; therefore, it is recommended that future studies use a variety of tools to assess these variables more objectively. Another limitation of this study was the short duration of the intervention; a two-session intervention may not be sufficient to induce lasting changes in students’ clinical competence and anxiety. Therefore, it is suggested that future studies use longer interventions. Additionally, concerns were raised about the potential for information leakage between groups due to the implementation of the study at the operation room. Hence, researchers attempted to minimize information leakage by conducting the intervention at separate times and locations to address this issue. Furthermore, the use of convenience sampling from a single university may limit the generalizability of the findings to broader populations of students in different academic or clinical contexts.

Conclusion

This study demonstrated that using surgical preference cards can positively enhance the skills and clinical competence of operating room nursing students while reducing their anxiety levels. Despite the positive results reported by various studies on the use of surgical preference cards, this tool has been neglected in healthcare settings. To enhance the practical application of surgical preference cards (SPCs), hospital and educational managers can play a key role in their implementation. One effective strategy could be the development of surgeon-specific SPC libraries, where preference cards are tailored to the unique needs and practices of individual surgeons. This approach not only ensures accuracy and relevance but also improves staff preparedness and coordination during surgeries. Furthermore, regular updates and collaboration between surgeons, operating room staff, and educators are essential to maintain the effectiveness of SPCs as both a clinical and educational tool.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by grant No 14020030 from Shahroud University of Medical Sciences. We would like to express our gratitude to all the students who participated in this study, as well as the support of the Student Research Committee of Shahroud University of Medical Sciences.

Clinical trial number

IRCT20230913059423N1.

Authors’ contributions

Conceptualization & study design: AA, MB. Data collection: SM, MS.; Data analysis: MHB; Study supervision: AA, MB; Manuscript writing: All authors (AA, MB, HB, MHB, SM, and MS). All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by Shahroud University of Medical Sciences.

Data availability

The datasets used during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki which includes explaining the study objectives, obtaining informed consent from the study participants, emphasizing the voluntary nature of participation, ensuring the right to withdraw from the study, assuring no harm from answering questions, and providing results upon request. Ethical approval was obtained from the research ethics committee of Shahroud University of Medical Sciences (code: IR.SHMU.REC.1402.096). The project was registered in the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials (registration code: IRCT20230913059423N1). Additionally, the authors adhered to the principles of the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) in publishing their findings.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Mortazavi S, Sharifirad G, Khoshgoftar Moghaddam A. Factors affecting the quality of clinical education from the perspective of teachers and learners of Saveh hospitals in 2019: a descriptive study. J Rafsanjan Univ Med Sci. 2020;19(9):909–24. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lloyd-Penza M, Rose A, Roach A. Using feedback to improve clinical education of nursing students in an academic-practice partnership. Teach Learn Nurs. 2019;14(2):125–7. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Su H, Wang J. Professional development of teacher trainers: the role of teaching skills and knowledge. Front Psychol. 2022;13:943851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jafarzadeh S. Evaluation the quality of clinical education from perspectives of perating room students, in Fasa university 2016. J Adv Biomedical Sci. 2018;8(4):1046–55. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meyer R, Van Schalkwyk SC, Prakaschandra R. The operating room as a clinical learning environment: an exploratory study. Nurse Educ Pract. 2016;18:60–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Azarabad S, Zaman S, Nouri B, Valiee S. Frequency, causes and reporting barriers of nursing errors in the operating room students. Res Med Educ. 2018;10(2):18–27. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dimitriadou M, Papastavrou E, Efstathiou G, Theodorou M. Baccalaureate nursing students’ perceptions of learning and supervision in the clinical environment. Nurs Health Sci. 2015;17(2):236–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dikmen BT, Bayraktar N. Nursing students’ experiences related to operating room practice: a qualitative study. J Perianesth Nurs. 2021;36(1):59–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roshanzadeh m, Taj A, Davoodvand S, Mohammadi S. Consequences of exposure of operating room students to clinical learning challenges. J Med Educ Dev. 2024;16(52):37–44. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rastgarian A, Esmaealpour N, Javadpour S, Sadeghi SE, Kalani N, Sepidkar AA, et al. Preoperative anxiety in hospitalized patients: A descriptive cross-sectional study in 2019. Med J Mashhad Univ Med Sci. 2020;63(1):2209–18. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alipour A, Ghadami A, Alipour Z, Abdollahzadeh H. Preliminary validation of the Corona disease anxiety scale (CDAS) in the Iranian sample. Health Psychol. 2020;8(32):163–75. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cobbett S, Snelgrove-Clarke E. Virtual versus face-to-face clinical simulation in relation to student knowledge, anxiety, and self-confidence in maternal-newborn nursing: a randomized controlled trial. Nurse Educ Today. 2016;45:179–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sargolzaei F, Omid A, Mirmohammad-Sadeghi M, Ghadami A. The effects of virtual-augmented reality training on anxiet among operating room students attending coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Nurs Midwifery Stud. 2021;10(4):229–35. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chevillotte J. Operating room nursing diploma soon to be accessible through competence validation. Revue de l’Infirmiere. 2014(199):10–. [PubMed]

- 15.Shibiru S, Aschalew Z, Kassa M, Bante A, Mersha A. Clinical competence of nurses and the associated factors in public hospitals of Gamo zone, Southern Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. Nurs Res Pract. 2023;2023(1):9656636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Notarnicola I, Duka B, Lommi M, Prendi E, Ivziku D, Rocco G, et al. editors. An observational cross-sectional analysis of the correlation between clinical competencies and clinical reasoning among Italian registered nurses. Healthcare: MDPI; 2024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kylmänen P, Spasic A. Assessing competence in technical skills of theatre nurses in India and Sweden: evaluation of an observational tool. 2010.

- 18.Yezengaw TY, Debella A, Animen S, Aklilu A, Feyisa W, Hailu M, et al. Clinical practice competence and associated factors among undergraduate midwifery and nursing sciences students at Bahir Dar city, Northwest Ethiopia. Ann Med Surg. 2024;86(2):734–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mohammadi G, Tourdeh M, Ebrahimian A. Effect of simulation-based training method on the psychological health promotion in operating room students during the educational internship. J Educ Health Promot. 2019;8(1):172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ghasembandi M, Mojdeh S. Investigating the influence of surgical preference card on clinical performance of operating room students in Isfahan’s Alzahra hospital. Educ Strateg Med Sci. 2019;11(6):41–6. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Geppert P, Daily B, Casanova S. Achieving surgical supply savings through preference card standardization. J Med Syst. 2020;44:1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Riley RG, Manias E. Governance in operating room nursing: nurses’ knowledge of individual surgeons. Soc Sci Med. 2006;62(6):1541–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bellaire LL, Nichol PF, Noonan K, Shea KG. Using preference cards to support a thoughtful, evidence-based orthopaedic surgery practice. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2024;32(7):287–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zarei MR, Bagheri S, Sedigh A, Ghasembandi M. The effect of surgical preference card on the clinical self-efficacy of operating room students. Nurs Pract Today. 2020;7(3):183–9.

- 25.Huntley JS, Howard JJ, Simpson J, Sigalet DL. Updating the surgical preference list. Cureus. 2018;10(7):e2997. 10.7759/cureus.2997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Andrade C. The inconvenient truth about convenience and purposive samples. Indian J Psychol Med. 2021;43(1):86–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hashemi N, Nazari F, Faghih A, Forughi M. Effects of blended aromatherapy using lavender and Damask Rose oils on the test anxiety of nursing students. J Educ Health Promotion. 2021;10(1):349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Barnes LL, Harp D, Jung WS. Reliability generalization of scores on the Spielberger state-trait anxiety inventory. Educ Psychol Meas. 2002;62(4):603–18. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Joshi BS, Thatte MD. Effect of providing Intra-operative status information on family members’ anxiety. Google Scholar. 2021;4(6):1–16.

- 30.Spielberger CD, Gonzalez-Reigosa F, Martinez-Urrutia A, Natalicio LF, Natalicio DS. The state-trait anxiety inventory. Revista Interamericana de Psicologia/Interamerican J Psychol. 1971;5(3 & 4).

- 31.Abdoli N, Farnia V, Salemi S, Davarinejad O, Jouybari TA, Khanegi M, et al. Reliability and validity of Persian version of state-trait anxiety inventory among high school students. East Asian Arch Psychiatry. 2020;30(2):44–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gillespie BM, Hamlin L. A synthesis of the literature on competence as it applies to perioperative nursing. AORN J. 2009;90(2):245–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ajorpaz NM, Tafreshi MZ, Mohtashami J, Zayeri F, Rahemi Z. Psychometric testing of the Persian version of the perceived perioperative competence scale–revised. J Nurs Meas. 2017;25(3):E162-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Adarvishi S, Asadi M, Mahmoodi M, Khodadadi A, Cheshmeh MGD, Farsani FA. Effect of problem-solving skill training on anxiety of operation room students. J Health Care. 2015;17(3):207–17. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Marteau TM, Bekker H. The development of a six-item short‐form of the state scale of the Spielberger State—Trait anxiety inventory (STAI). Br J Clin Psychol. 1992;31(3):301–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fountoulakis KN, Papadopoulou M, Kleanthous S, Papadopoulou A, Bizeli V, Nimatoudis I, et al. Reliability and psychometric properties of the Greek translation of the state-trait anxiety inventory form Y: preliminary data. Ann Gen Psychiatry. 2006;5:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gillespie BM, Polit DF, Hamlin L, Chaboyer W. Developing a model of competence in the operating theatre: psychometric validation of the perceived perioperative competence scale-revised. Int J Nurs Stud. 2012;49(1):90–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bahrami M, Mohammadi S, Dehghan Abnavi S, Taj A, Maraki F. The effect of suture simulation method on animal skin on skills and anxiety caused by suturing in operating room students. Payavard Salamat. 2023;17(4):290–9. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Raymond JM, Sheppard K. Effects of peer mentoring on nursing students’ perceived stress, sense of belonging, self-efficacy and loneliness. J Nurs Educ Pract. 2018;8(1):16–23. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kachaturoff M, Caboral-Stevens M, Gee M, Lan VM. Effects of peer-mentoring on stress and anxiety levels of undergraduate nursing students: an integrative review. J Prof Nurs. 2020;36(4):223–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dalvand S, Ahmadi F, Akbari A, Shirdel M. Effect of a cognitive training program and Jacobson relaxation technique on anxiety and resilience of students in the operation room: a randomized control trial. J Nurs Adv Clin Sci. 2024;2(2):57–62. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Roberts BW, Luo J, Briley DA, Chow PI, Su R, Hill PL. A systematic review of personality trait change through intervention. Psychol Bull. 2017;143(2):117–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gutiérrez-Carmona A, González-Pérez M, Ruiz-Fernández MD, Ortega-Galán AM, Henríquez D. Effectiveness of compassion training on stress and anxiety: a pre-experimental study on nursing students. Nurs Rep. 2024;14(4):3667–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Anisi E, Sharifian P, Sharifian P. The effect of an educational orientation tour on anxiety of nursing students before their first clinical training: a quasi-experimental study. BMC Nurs. 2025;24(1):522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ghamari M, Ghasemzadeh A, Hosseinian S. The effectiveness of mindfulness training on students’ anxiety and psychological well-being. Bimon Educ Strategies Med Sci. 2021;14(1):77–87. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ebrahimian A, Koohsarian F, Rezvani N. The effect of operating room simulation on students’ hidden anxiety during operating room internship. Iran J Med Educ. 2018;18:384–91. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Katebi MS, Ahmadi AA, Jahani H, Mohalli F, Rahimi M, Jafari F. The effect of portfolio training and clinical evaluation method on the clinical competence of nursing students. J Nurs Midwifery Sci. 2020;7(4):233. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zakerimoghadam m, Yazdanparast E, Hosseiny SF, Ahmadi Chenari H. A review of new methods assessment in clinical education of medical science students. Bimon Educ Strategies Med Sci. 2021;14(3):92–102. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mirbagher Ajorpaz N, Zagheri Tafreshi M, Mohtashami J, Zayeri F, Rahemi Z. The effect of mentoring on clinical perioperative competence in operating room nursing students. J Clin Nurs. 2016;25(9–10):1319–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ghasemi S, Imani B, Jafarkhani A, Hosseinefard H. Roles of two learning methods in the perceived competence of surgery and quality of teaching: a quasi-experimental study among operating room nursing students. J Adv Med Educ Prof. 2024;12(3):180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.