Abstract

The increasing prevalence of treatment-resistant diseases has driven researchers to investigate advanced medical approaches, including stem cell-based therapies. Morphine, commonly used for pain relief, is associated with high addiction potential. It has been established that µ, δ, and κ opioid receptors are present in bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (BMSCs), suggesting that morphine may compromise the efficacy of stem cell therapy in addicted individuals. However, the impact of morphine on the biological characteristics of BMSCs remains poorly understood. Therefore, this study aims to evaluate the morphine effects on the properties of BMSCs in morphine-dependent rats and assess the potential of low-dose naloxone (LDN) in counteracting the adverse effects. Animals were randomly devided into four experimental groups (n = 7) including the morphine treatment group (10 mg/kg), LDN treatment group (10 µg/kg), Combination group (MOR + NXL) (10 mg/kg + 10 µg/kg), and the control group (normal saline). All subcutaneous administrations were every 12 h for 7 consecutive days. After chronic morphine addiction, behavioral tests were conducted to assess opioid tolerance and dependence in different groups. Rats were then euthanized, and BMSCs were isolated. Subsequently, cell survival, migration, and the expression of homing markers, including C-X-C chemokine receptor type 4 (CXCR4), matrix metalloproteinase-2 (MMP-2), and Very Late Antigen-4 (VLA4), were analyzed. Additionally, antioxidant markers and TNFα and IL-10 levels were measured in the conditioned medium. Morphine administration significantly reduced the body weight (P < 0.05). However, this weight loss was not observed in morphine co-administered with LDN. LDN also blocked morphine-induced analgesic tolerance and dependence. Afterward, isolated BMSCs from morphine-dependent rats exhibited significantly reduced cell survival, migration, and prolonged doubling time compared to other groups (P < 0.05). Additionally, levels of TNFα, IL-10, and malondialdehyde (MDA), a marker of lipid peroxidation, were significantly higher in the morphine group than in the other groups. Moreover, the protein expressions of CXCR4, VLA4, and MMP-2 were downregulated in the morphine-treated group. Notably, LDN co-treatment preserved survival, lowered doubling time, MDA, and TNFα levels, and restored the homing markers. Given the negative effects of morphine on the key properties of BMSCs, it can be concluded that individuals addicted to morphine may be suboptimal candidates for cell therapy. However, adjunctive LDN treatment could restore these effects and improve therapeutic outcomes.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-025-14606-8.

Keywords: Morphine, Naloxone, Addiction, Stem cell, Implantation, Homing, CXCR4 receptor

Subject terms: Pharmacology, Biochemistry, Neuroscience, Stem cells

Introduction

Stem cells (SCs) are defined as undifferentiated cells capable of self-renewal and differentiation into various types of cells. SCs play fundamental roles in tissue growth, homeostasis, and repair of many injured tissues1–3. For effective SC therapy, several critical factors must be considered, including migration or homing, aging, survival, proliferation, differentiation, and immune response4,5. The homing process, whereby SCs migrate to specific tissue or injury sites, is crucial for therapeutic success6. Homing is guided through a sophisticated signaling network comprising chemokines, cytokines, and adhesion molecules, which direct the SCs to the desired location7,8. The chemokine receptor C-X-C chemokine receptor type 4 (CXCR4) and stromal cell-derived factor 1 (SDF-1) as its ligand are a pivotal axis in directing SCs to the site of injury. Another important molecule is cluster of differentiation 44 (CD44), which is a cell surface glycoprotein involved in cell adhesion and migration through its interactions with hyaluronic acid and other extracellular matrix ligands, facilitating tissue-specific adhesion and migration. Critical adhesion events are further mediated by integrins, particularly very late antigen-4 (VLA-4) or α4β1 and α5β1 which establish essential interactions with vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1) and fibronectin9–11. Completing this molecular cascade, matrix metalloproteinase-2 (MMP-2) enables stem cell mobilization by remodeling extracellular matrix barriers through targeted proteolysis, thereby permitting access to damaged or inflamed tissues12.

Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (BMSCs), a subset of multipotent stromal cells residing in the bone marrow, are widely studied in regenerative medicine. Key considerations in stem cell therapy include determining the optimal dosage of MSCs, donor health condition, administration routes, the best time for transplantation, and post-injection cell fate13–16. While most studies have utilized BMSCs derived from young or healthy individuals, it remains unclear whether addicted persons with opioids are suitable candidates for stem cell therapy. Only a limited number of studies evaluated the impact of opioids on SCs. One such study confirmed the expression of the presence of µ-, δ-, and κ- opioid receptor expression in human BMSCs, which shows that morphine can alter the phenotypic characteristics and functional properties of these cells. The findings suggest that morphine adversely affects MSC functions, suggesting mechanisms by which opioids may impair tissue regeneration and healing processes17. Other studies have demonstrated that morphine and other opioids inhibit the proliferation of neural stem cells and impair neurogenesis in the hippocampus18,19. Besides, chronic morphine could disrupt angiogenesis and the activation of endothelial progenitor cells, which alters normal healing processes20. More notably, morphine negatively impacted topical opioid analgesics on wound closure and bone healing21,22. Considering the role of MSCs in the repair of tissues, it becomes crucial to consider the concerns of stem cell therapy in opioid-dependent individuals23,24.

Morphine, a phenanthrene alkaloid derived from opium, is widely used for pain relief but carries high addiction potential. Opioid addiction, which refers to compulsive drug seeking, tolerance, and physical dependence, is a global public health crisis, especially in the Middle East and Iran due to geographic proximity to opioid-producing regions25,26. Tolerance, considered by the need for increasing doses of opioids to achieve the same analgesic effect, often leads to a vicious cycle of escalating drug use27. Dependence, on the other hand, manifests as a physical and psychological reliance on opioids, making withdrawal and cessation exceedingly difficult for individuals suffering from addiction25. Current treatments like methadone, buprenorphine, and naloxone (NLX) have limitations, including side effects and high relapse rates28. NLX, a non-selective opioid receptor antagonist, is traditionally used in high doses to reverse opioid overdose. Interestingly, low-dose naloxone (LDN) acts differently by modulating opioid receptor signaling and reducing opioid tolerance and dependence while avoiding withdrawal symptoms. This unique ability to regulate receptor activity without adverse effects makes LDN a promising adjunctive therapy in opioid addiction29–31.

Emerging evidence suggests LDN may extend beyond just the modulation of opioid effects, and we hypothesized that LDN may influence the expression of key factors involved in MSC homing including CXCR-4, VLA4, VEGF, MMPs, and cytokines and these modifications could potentially enhance MSC migration to damaged tissues, thereby promoting repair and regeneration processes. Hence, this study aims to1 assess the impact of morphine on the viability, proliferation, and differentiation of BMSCs, and2 explore LDN’s dual role in mitigating opioid tolerance and dependence while increasing BMSC homing factors like SDF-1 and CXCR4, to improve the BMSC-based therapy efficiency in opioid exposure contexts.

Materials and methods

Materials

Morphine sulfate was provided by the Deputy of Food and Drug, Kerman University of Medical Sciences, Kerman, Iran. Naloxone hydrochloride was purchased from a pharmaceutical manufacturing company.

Laboratory animals, study groups, and drug administrations

This study was conducted in compliance with the Research Ethics Committee of Kerman University of Medical Sciences, Kerman, Iran (IR.KMU.REC.1398.652), and followed relevant institutional guidelines and regulations. All experimental procedures were performed in accordance with ARRIVE guidelines. Male Wistar rats (n = 28, 250–300 g) were obtained from the institutional animal facility and housed in polypropylene cages under standard conditions (12:12 h light-dark cycle, 22 ± 2 °C) with ad libitum access to food and water. Animals were randomly allocated into four experimental groups (n = 7 per group). 1- Morphine treatment group (MOR): Received subcutaneous morphine (10 mg/kg) every 12 h32. 2- LDN treatment group (NXL): Received subcutaneous naloxone (10 µg/kg) every 12 h. 3- Combination group (MOR + NXL): Morphine and naloxone were injected subcutaneously every 12 h at 10 mg/kg and 10 µg/kg, respectively. 4- The control (CTL) group received normal saline (0.9% NaCl) as the same as morphine or naloxone volume per injection via SC at the same time points to match the injection volume and schedule of the experimental groups. All treatments were for 7 consecutive days. Subcutaneous administration was chosen to ensure precise dosing and more efficient systemic absorption, avoiding first-pass metabolism associated with oral gavage, consistent with established opioid dependence models.

Tail-flick behavioral test to check the animal’s analgesic level

The tail-flick test assessed nociceptive thresholds to a painful heat stimulus using a digital analgesia meter with a projection lamp. Animals were habituated to the testing apparatus for 5–10 min daily before experiments to minimize stress responses. The heat source was aimed at the middle third of the tail, and the latency to tail removal was recorded. The heat intensity was adjusted for a 5-second baseline response, with a 10-second cutoff to prevent tissue damage. Baseline measurements were taken before drug administration, followed by tests 30 min after the morning dose on days 0, 1, 3, 5, and 733.

Testing for naloxone-induced morphine withdrawal symptoms

Following confirmation of morphine tolerance induction via the tail-flick test, the rats were subjected to a morphine dependence assessment using the naloxone challenge test. NLX (1 mg/kg) was injected intraperitoneally, and withdrawal behaviors were recorded over a 15-minute observation period. The assessed withdrawal symptoms included jumping, abdominal writhing, rearing, body and genital grooming, and wet dog shaking32.

Isolation of BMSCs and characterization

After the behavioral tests, the rats were euthanized using decapitation under ketamine 300 mg/kg and xylazine 30 mg/kg anesthesia. Bilateral femurs and tibias were isolated, and bone marrow was then extracted by flushing the marrow cavity with 10 mL of high-glucose DMEM using a 21-gauge sterile needle. The harvested bone marrow was suspended in complete high-glucose DMEM containing 15% FBS, 1% penicillin-streptomycin, and cultured in culture flasks. The cells were incubated at 37 °C in a humidified chamber with 95% air and 5% CO2. After 24 h, non-adherent cells were discarded, and the medium was replaced with fresh medium. Passage 3 cells were collected for subsequent experiments. Isolated BMSCs were characterized by flow cytometry for expression of positive markers, including CD44 and CD90, and negative markers (CD34 and CD45)34.

Evaluation of cell viability and population doubling time (PDT)

To evaluate the effect of the drugs on the BMSCs’ survival, the MTT assay (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)−2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) was used. This assay quantifies cell viability by measuring the reduction of MTT to a purple formazan product by mitochondrial enzymes in metabolically active cells. Passage 3 BMSCs were seeded at a density of 10,000 cells/well in a 96-well plate. MTT assay was performed at 24, 48, 72, and 96 h. Absorbance was measured at 570 nm using a microplate reader. All experiments were in triplicate.

PDT, a critical parameter in stem cell proliferation studies, represents the time required for a cell population to double. To calculate the PDT, BMSCs were seeded at 1 × 104 cells in a 48-well plate and cultured under standardized conditions. Over four consecutive days, cells were trypsinized, and the number of viable cells was counted using the Trypan blue exclusion assay. Cell numbers were recorded at the beginning and at subsequent time points until a sufficient number of doublings had occurred. The PDT was calculated using the formula:

PDT = (Δt × ln(2)/ln(Nt/N0)

Where, Δt represents time interval between the two cell counts (final and initial), ln indicates natural logarithm (logarithm to base e, where e ≈ 2.718), Nt is final number of cells, and N0 shows the initial number of cells.

Cell migration test

BMCSs were seeded in 6-well plates at a density of 1 × 10⁶ cells per well. Upon reaching 90% confluency, a scratch wound was made using a sterile 100 µL pipette tip. Then, 5 fields were marked and imaged at 0 and 24 h for migration capacity. The empty area was measured using the ImageJ program and expressed as a percentage closure relative to the initial empty area35.

Measurement of cytokines

The cellular supernatant was harvested and centrifuged at 4 °C for 10 min at 8000 x g. Then, the Tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα) and interleukin-10 (IL-10) were measured using the sandwich ELISA method36.

Evaluation of oxidative and antioxidant indices

To assess oxidative stress markers in BMSC-conditioned media, including malondialdehyde (MDA) and total antioxidant capacity (TAC) of BMSCs’ conditioned medium, TBARS and FRAP assays were performed, respectively. Following centrifugation of cell supernatants, the TAC and MDA levels were measured as described previously37,38.

BMSC homing protein markers expression

BMSCs (1 × 10⁶ cells) from each experimental group were lysed in 500 µL lysis buffer and centrifuged (10,000 × g, 10 min, 4 °C). The protein-containing supernatant was collected and stored at −80 °C. Protein concentration was measured by Bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay. Proteins were then separated by SDS-PAGE electrophoresis and transferred to a PVDF membrane. Membranes were incubated with primary antibodies of homing markers, including CXCR4, VLA4, and MMP2, and GAPDH was considered as a loading control.

Statistical analysis

Statistical comparisons between groups were performed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by related post-hoc test and Kruskal Walis test for nonparametric data. Results are presented as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM), with statistical significance defined as P < 0.05.

Results

Effects of morphine and naloxone on rat weight gain

As shown in Fig. 1, neither morphine nor naloxone administration significantly affected rat weight gain until day 4. However, on day 7, the MOR group demonstrated reduced weight gain compared to the other groups. This weight loss was significant when compared with the control, NXL, and MOR + NXL groups (P < 0.05). Importantly, there was no significant decrease in weight gain in the MOR + NXL group compared to the control.

Fig. 1.

Body weight changes measured at baseline (day 0), day 4, and day 7 across experimental groups. Statistical significance is indicated as follows: * Comparison of groups with control (CTL), and # comparison of groups with morphine-treated (MOR) group. #, * P < 0.05, ##, ** P < 0.01.

Analgesic effects using the tail-flick test

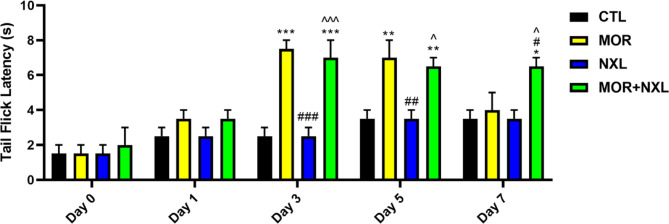

To evaluate the analgesic effects of morphine, naloxone, and the combination of morphine-naloxone, the tail-flick test was done on the rats on days 0 (baseline), 1, 3, 5, and 7. The results indicated that the MOR group showed peak analgesia on day 3, followed by a progressive decline starting at day 5. The low dose of naloxone demonstrated no analgesic effects at any time point. Notably, the MOR + NXL combination maintained the morphine-induced analgesia without increasing the morphine dose. Both MOR and MOR + NXL groups showed significant analgesia versus control from day 3 through day 5 (P < 0.05). However, on day 7, a significant analgesic effect was only seen in the MOR + NXL group compared to the other groups (P < 0.05, Fig. 2).

Behavioral outcomes for symptoms of naloxone-induced withdrawal syndrome

On day 7, rats received naloxone (1 mg/kg, i.p.) to precipitate withdrawal syndrome. As demonstrated in Fig. 3, the MOR group exhibited significantly elevated withdrawal symptoms, including jumping, abdominal writhing, rearing, and wet-dog shaking, compared to the CTL, NLX, and MOR + NXL groups (P < 0.05). However, there were no significant differences in body/genital grooming between groups. Notably, concurrent LDN and morphine administration attenuated naloxone-precipitated withdrawal symptoms. However, the MOR + NLX group still showed significantly more abdominal writhing, rearing, and wet-dog shaking compared to the control group (P < 0.05).

Fig. 2.

Analgesic effects measured by the tail-flick test at baseline (day 0), 3, 5, and 7. Statistical significance is indicated as: * Comparison of groups with control (CTL), # comparison of groups with morphine-treated (MOR) group, and ^ comparison of groups with low dose of naloxone (NXL). ^, #, * P < 0.05, ^^, ##, ** P < 0.01, ^^^, ###, *** P < 0.001.

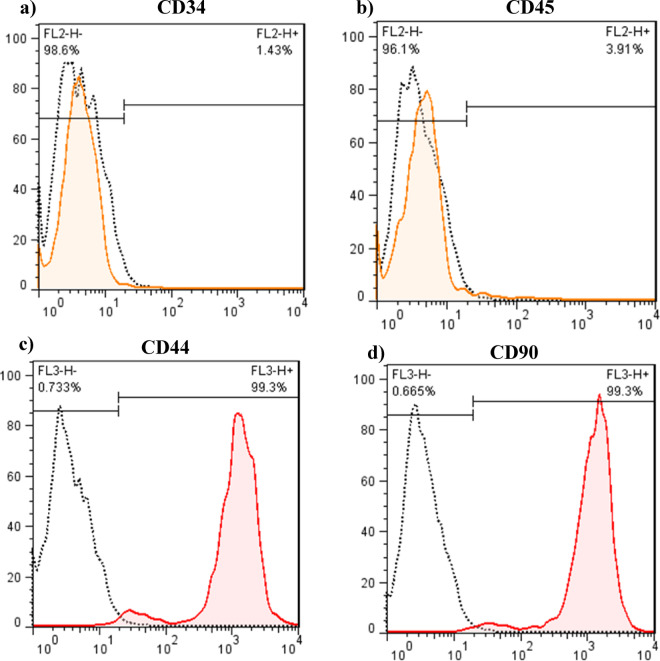

BMSCs isolation and flow cytometry results

After 3 passages of BMSCs, CD markers were measured using the flow cytometry method, and the evaluations showed that most of the adhesive cells (> 95%) were positive for CD44 and CD90 and negative for CD34 and CD45 markers (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Characterization of BMSC surface markers by flow cytometry. (a-b) Negative hematopoietic markers (CD34, CD45); (c-d) Positive mesenchymal markers (CD44, CD90). Data demonstrate > 95% purity of passage 3 BMSCs, meeting established MSC criteria.

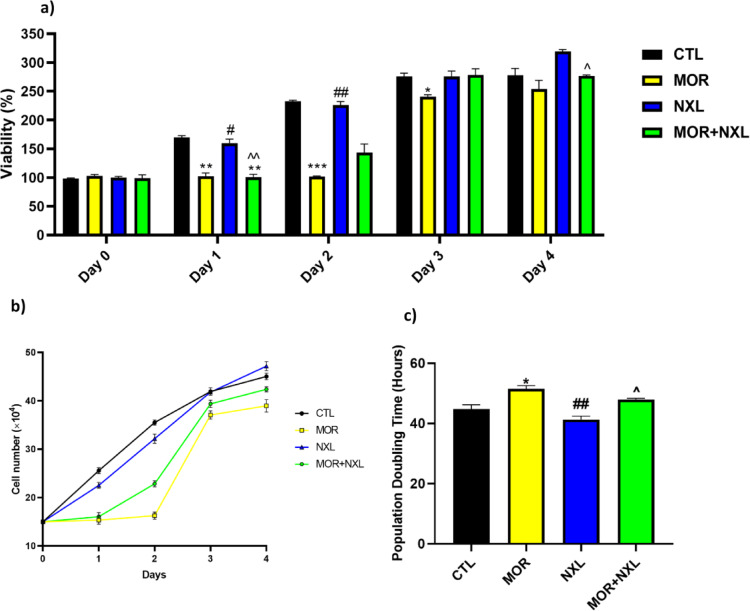

Co-administration of NLX and MOR restores survival, doubling time, and migration of BMSCs

The MTT assay results, which measure cell viability via mitochondrial activity, demonstrated that the BMSCs isolated from the control and NXL groups exhibited robust cell viability and proliferation. In contrast, the stem cells extracted from MOR-treated rats showed reduced viability at 24 h (P < 0.05). Notably, co-treatment with low-dose naloxone (MOR + NXL) attenuated this reduction (Fig. 5a). Similarly, cell counts over four days confirmed delayed growth in the MOR and MOR + NXL groups, with cell numbers increasing only from day 3 and remaining lower than CTL and NXL groups by day 4 (Fig. 5b). Consequently, PDT analysis revealed maximum doubling time in MOR group (51.92 h vs. CTL, P < 0.05) (Fig. 5c). In contrast, the lowest PDT times were for the NXL and CTL groups, respectively. The results also indicated that co-treatment with LDN could restore cell growth and proliferation, indicating naloxone’s ability to counteract morphine’s suppressive impact on stem cell survival and growth. Consistent with lowered proliferative capacity, the scratch assay showed that BMSC migration was also reduced in the MOR group (P < 0.05 vs. CTL). Conversely, NLX-only treated cells showed a non-significant increase in migration rate versus controls (P = 0.07), the MOR + NLX group demonstrated intermediate migratory ability, significantly greater than the MOR group (P < 0.05) but not statistically different than controls, implying that the morphine effects on migration were mitigated by low levels of naloxone (P < 0.05, Figs. 6a and b).

Fig. 3.

Effect of morphine (MOR), naloxone (NLX), and their combination (MOR + NLX) naloxone-precipitated withdrawal symptoms in morphine-dependent rats. (a) jumping, (b) abdominal writhing, (c) rearing, (d) wet-dog shaking, and (e) grooming behavior. Statistical significance is indicated as: * Comparison of groups with control (CTL), # comparison of groups with morphine-treated (MOR) group, and ^ comparison of groups with low dose of naloxone (NXL). ^, #, * P < 0.05, ^^, ##, ** P < 0.01, ^^^, ###, *** P < 0.001.

Measurement of cytokines and oxidative stress markers

ELISA measurements revealed significantly elevated levels of both pro-inflammatory TNF-α and anti-inflammatory IL-10 cytokines in MOR compared to the control group (Figs. 7a, b). While low-dose naloxone did not affect the modulation of the cytokine, the MOR + NLX combination substantially attenuated morphine-induced cytokine secretion in the cell supernatant. While oxidative stress analysis demonstrated that there were no significant differences between different groups in the amount of TAC in the supernatant, the values of MDA, as a lipid peroxidation marker, in the MOR group significantly increased. Notably, the MOR + NXL group reduced MDA concentrations versus MOR alone, consistent with naloxone’s protective effects against morphine-induced lipid peroxidation (Figs. 7c, d).

Fig. 5.

(a) Effects of morphine (MOR), naloxone (NXL), and their combination (MOR + NXL) on BMSC proliferation. (b) Evaluation of the number of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells over 4 days in different groups. (c) PDT calculated for each group. Statistical significance is indicated as: * Comparison of groups with control (CTL), # comparison of groups with morphine-treated (MOR) group, and ^ comparison of groups with low dose of naloxone (NXL). ^, #, * P < 0.05, ^^, ##, ** P < 0.01, ^^^, ###, *** P < 0.001.

Fig. 7.

(a) Comparison of TNFα concentrations between study groups. (b) Comparison of IL-10 concentrations across study groups. (c) Comparison of MDA values in the supernatant of cells, and (d) comparison of TAC levels of the supernatant of cells in different groups. Statistical significance is indicated as: * Comparison of groups with control (CTL), # comparison of groups with morphine-treated (MOR) group, and ^ comparison of groups with low dose of naloxone (NXL). ^, #, * P < 0.05, ^^, ##, ** P < 0.01, ^^^, ###, *** P < 0.001.

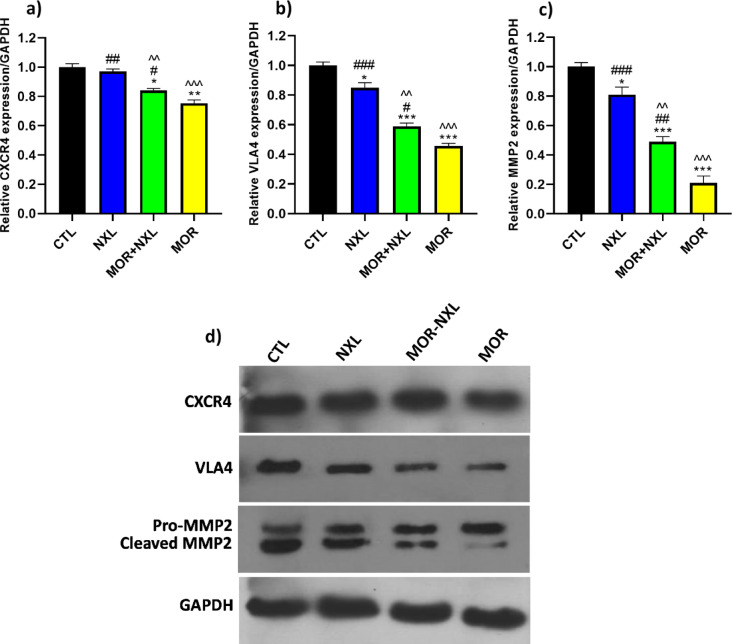

3.7. Co-administration of MOR-NLX affects homing markers expression

To evaluate the homing potential of BMSCs in different groups, CXCR4, VLA4, and cleaved/pro-MMP2 ratio protein expression were measured, and GAPDH was considered as the loading control. The data showed that MOR significantly reduced the expression of CXCR4 protein compared to other groups (P < 0.05), while low-dose naloxone alone showed comparable CXCR4 levels to CTL. Interestingly, the MOR + NXL combination augmented CXCR4 expression compared to the MOR group. This increase in CXCR4 expression in the MOR + NXL group was significantly higher than that in the MOR group (P < 0.05). Similar protein expression patterns were observed for VLA4 and cleaved/pro-MMP2. NXL treatment caused modest but significant reductions versus CTL (P < 0.05), whereas morphine profoundly suppressed both markers (P < 0.001 vs. CTL). The MOR + NXL combination therapy partially reversed these effects, restoring VLA4 (P < 0.05 vs. MOR) and cleaved/pro-MMP2 (P < 0.01 vs. MOR) toward baseline levels (Figs. 8a-d). These findings highlight LDN’s context-dependent effects on BMSC homing markers.

Fig. 6.

(a) Shows scratches in the stem cells at 0 h and 24 h post-wounding. (b) The percentage of area filled by BMSCs is shown in different groups. Statistical significance is indicated as: * Comparison of groups with control (CTL), # comparison of groups with morphine-treated (MOR) group, and ^ comparison of groups with low dose of naloxone (NXL). ^, #, * P < 0.05, ^^, ##, ** P < 0.01, ^^^, ###, *** P < 0.001.

Fig. 8.

Western blot analysis quantified by ImageJ software for the expression leveles of the (a) CXCR4, (b) VLA4, and (c) MMP2 proteins (normalized to GAPDH). (d) Representative blots. Statistical significance is indicated as: * Comparison of groups with control (CTL), # comparison of groups with morphine-treated (MOR) group, and ^ comparison of groups with low dose of naloxone (NXL). ^, #, * P < 0.05, ^^, ##, ** P < 0.01, ^^^, ###, *** P < 0.001.

Discussion

Morphine-Induced behavioral and metabolic effects

This study showed that chronic morphine administration significantly attenuated weight gain in rats compared to the control group (P < 0.05), consistent with prior reports of opioid-induced metabolic dysregulation and appetite suppression39,40. Moreover, tail-flick confirmed morphine’s characteristic analgesic profile, with peak efficacy on Day 3 followed by progressive decline. By Day 7, morphine-treated rats exhibited no significant analgesia versus controls, indicating tolerance development. Chronic opioid addiction leads to tolerance, a condition where progressively higher doses are required to achieve the same level of pain relief. This tolerance is associated, at least partially, with the internalization of mu (µ) opioid receptors on the cell surface. Upon binding of an opioid drug to µ receptor, a sequence of molecular events is initiated. As a G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR), the µ receptor undergoes a conformational change, leading to the activation of associated G proteins and downstream signaling pathways that mediate analgesia (pain relief), sedation, and other effects. However, this activation also triggers the phosphorylation of the µ receptor by G protein-coupled receptor kinases (GRKs). This phosphorylation serves as a signal for the recruitment of beta-arrestins, which bind to the phosphorylated receptors and uncouple them from G proteins, leading to desensitization and eventual internalization of the µ receptors from the cell surface. The net result is diminished cellular responsiveness to opioids, which manifests clinically as the development of tolerance41,42. Opioids exert additional effects by inhibiting the release of substance P, a neuropeptide involved in analgesia. Some mechanisms that contribute to analgesia also cause euphoric effects. This dual activity significantly enhances the abuse potential of opioids and motivates ongoing research into interventions that could maintain therapeutic analgesia while preventing misuse43.

Adverse effects of morphine on BMSC function

In recent decades, stem cell therapy has emerged as a promising approach for treating various medical conditions due to its potential to regenerate damaged tissues and organs. However, the therapeutic efficacy and safety can be influenced by underlying patient comorbidities and lifestyle factors, including diabetes, cardiovascular disease, chronic inflammatory disorders, alcohol consumption, and opioid addiction16,44,45. Despite its potential, stem cell applications in regenerative medicine face persistent challenges. In vitro maintenance of stem cells often leads to cellular senescence, impairing their differentiation capacity and self-renewal properties. Exploring molecules and strategies to overcome these limitations is an ongoing area of research46.

In this study, the morphine-treated group exhibited significantly reduced cell viability and proliferation compared to other groups, resulting in decreased migration and prolonged population doubling time. These findings were consistent with Farrokhfar et al.., who reported that the pharmacological doses of morphine increased cell doubling time and decreased cell viability47. These interconnected effects likely stem from µ-opioid receptor activation, which triggers pro-apoptotic pathways including Fas receptor upregulation, alterations in BAX and Bcl-2 expression, and other pathways of oxidative/nitrosative stress or inflammation48,49. Willner and colleagues explored the effects of the opioid morphine on proliferation, apoptosis, and differentiation in the mouse central nervous system during early prenatal development. Using neural progenitor cells (NPCs) from 14-day-old mouse embryos, the NPCs were treated with various concentrations of morphine sulfate for 24 h. To assess specific parameters, the treated NPCs were co-stained with proliferation, apoptosis, and differentiation markers. Their findings revealed that morphine reduced NPC proliferation and induced caspase-3 activity, an apoptotic enzyme, in a dose-dependent manner50. These findings are consistent with the results of the current study, demonstrating that morphine reduces stem cell proliferation and increases the doubling time.

As mentioned, activation of the µ receptor triggers a cascade of pro-inflammatory responses, including the release of TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β, and nitric oxide via calcium channel-mediated pathways51. Similar results were observed in this study, with increased TNFα levels in the morphine group. The anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 levels also increased in the current study, suggesting a compensatory feedback mechanism to counterbalance TNF-α-driven inflammation by suppressing downstream inflammatory mediators52. Morphine-induced oxidative/nitrosative stress further exacerbated cellular damage, as evidenced by significantly elevated MDA. Increased MDA levels due to morphine were also reported by Peirouvi et al.. in 202053.

Moreover, morphine significantly downregulated the surface expression of CXCR4, VLA4, and cleaved MMP2. In a similar study, morphine inhibits CXCL12-induced CXCR4 phosphorylation in neural cells. Specifically, morphine pretreatment was shown to abolish CXCR4 phosphorylation, indicating that opioids disrupt key processes in CXCR4-mediated signaling, including receptor activation, internalization, and recycling54. Further supporting these observations, Wilson et al.. in 2011 reported that chronic morphine administration increases CXCL12 expression and decreases CXCR4 receptor expression55.

Protective role of low-dose naloxone in mitigating morphine effects

In the morphine-induced weight loss section of the current study, the co-administration of low-dose naloxone and morphine prevented the weight loss, suggesting LDN may counteract morphine’s metabolic disruptions. Next, the tail flick confirmed tolerance induced by morphine in the MOR group. While naloxone alone lacked analgesic activity, its combination with morphine (MOR + NXL) sustained stable antinociception without dose escalation. A similar finding by Chou et al.. indicated that intrathecal LDN administration with morphine in both co-infusion and post-treatment preserves the antinociceptive effect and reduced tolerance development of morphine in rat models31.

Accordingly, naloxone-precipitated withdrawal syndrome test was conducted at a dose of 1 mg/kg. The results demonstrated that morphine-treated rats displayed statistically significant withdrawal symptoms compared to other groups. Conversely, the concurrent administration of a low dose of naloxone with morphine reduced the severity of withdrawal symptoms. Align with Mannelli et al.., which showed very low-dose naltrexone mitigates withdrawal symptoms in morphine-dependent rats, potentially via reduced activation of brainstem noradrenergic neurons29. Moreover, a retrospective matched cohort study compared two naloxone dosing regimens (LDN; < 0.15 mg) and high-dose naloxone (HDN; >0.15 mg) for opioid toxicity reversal and withdrawal symptom induction. The results showed that HDN patients had more opioid withdrawal symptoms and more frequent toxicity reversal criteria versus LDN patients56. Emerging evidence indicates that low doses of opioid antagonists might paradoxically enhance morphine analgesic effects while reducing dependence on opioids. Preclinical studies suggest that microdoses of naloxone decrease the hyperactivity of opioid receptors, thereby reducing withdrawal severity29,57.

This study explored that LDN co-treatment restored BMSC viability, proliferation, and migration, with significantly improved CXCR4, VLA4, and MMP-2 expression compared to the MOR group (P < 0.05). The shorter PDT in the MOR + NXL group reflects enhanced proliferation, which likely supports improved migration capacity. Notably, the non-significant increase in migration in the NXL group (P = 0.07 vs. control) suggests a potential stimulatory effect of LDN on cell motility, warranting further investigation. LDN also reduced morphine-induced TNF-α, IL-10, and MDA levels, indicating protective effects against inflammation and oxidative stress. Hence, by enhancing proliferation, migration, and homing, LDN may improve the efficacy of BMSC therapies in opioid-exposed individuals. Several preclinical studies have consistently demonstrated that ultra-low or low-dose naloxone can preserve morphine’s analgesic efficacy while mitigating tolerance and inflammatory side effects. Tsai et al. showed that naloxone, either 15 µg/kg or 15 ng/kg, co-administered with morphine on the pertussis toxin-induced thermal hyperalgesia to preserve antinociception and inhibiting the pertussis toxin elevation of excitatory amino acids, including L-glutamate and L-aspartate, and microglia activation, accompanied by significant reductions in pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1β and IL-6 in rat spinal cord30. A cellular study by Gabr et al. confirmed that nano-tomicrogram naloxone doses suppress TLR4-mediated opioid-induced neuroinflammation58. The possible mechanism reported by Burns and Wang who repoted that ultra-low-dose naloxone/naltrexone effects occur by preventing a G protein coupling switch (Gi/o to Gs) of the µ opioid receptor that occurs briefly after acute administration or persistently after chronic administration of opioids59. In contrast, a clinical study involving 0.25–1 µg/kg/h naloxone infusion in patients with renal colic failed to reduce opioid requirements or inflammatory markers, highlighting translational limitations60. Several studies show that LDN supports maintaining morphine’s pain-relieving effects and reduces brain inflammation in lab tests, but results in human studies vary, so more research is needed to bridge this gap.

Conclusion

Besides the deleterious effects of morphine on behavioral tests including tolerance, dependence, and withdrawal symptoms, this study reveals that chronic morphine exposure could increase pro-inflammatory cytokines and oxidative stress, impair BMSC viability, proliferation, migration, and homing marker expressions (CXCR4, VLA4, MMP-2) in the in vivo and in vitro models. These findings may suggest that poor outcomes are associated with BMSC-based therapies in individuals with opioid dependence. Conversely, co-treatment with LDN restores these functions by decreasing tolerance and withdrawal symptoms and improving the microenvironment for promoting stem cell homing. These results highlight important clinical usage of LDN in BMSC therapy could pave the way for favorable regenerative intervention outcomes in opioid-dependent patients, particularly for regenerative treatments targeting tissue repair. These findings need further validation in human-derived BMSCs, alongside the development of safe clinical LDN guidelines for translational research.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors are thankful to the Physiology Research Center, Institute of Neuropharmacology Center, Kerman University of Medical Sciences, Kerman, Iran.

Author contributions

The authors confirm their contribution to the paper as follows: data collection and doing the experiments: M.MG., A.R., ME.N., M.S., S.Y., and Kh. E.B.; study conception and design: MH.N., M.M., and Z.B.; analysis and interpretation of results: MH.N.; draft manuscript preparation: M.M. and MH.N. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Herbal and Traditional Medicines Research Center, Kerman University of Medical Sciences, Kerman, Iran (grant number 98001080).

Data availability

Data will be made available upon reasonable request, and Dr. Hadi Nematollahi should be contacted if someone wants to request the data from this study.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical Statement

The protocol of this study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Kerman University of Medical Sciences, Kerman, Iran (IR.KMU.REC.1398.652).

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Maryamossadat Mirtajaddini Goki and Azadeh Rostamgohary.

Contributor Information

Mohammad Hadi Nematollahi, Email: mh.nematollahi@yahoo.com.

Mehrnaz Mehrabani, Email: mehrnaz.mehrabani@yahoo.com.

References

- 1.Abu-Dawud, R., Graffmann, N., Ferber, S., Wruck, W. & Adjaye, J. Pluripotent stem cells: induction and self-renewal. Philosophical Trans. Royal Soc. B: Biol. Sci.373 (1750), 20170213 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Klimczak, A. & Kozlowska, U. Mesenchymal stromal cells and tissue-specific progenitor cells: their role in tissue homeostasis. Stem Cells Int.2016 (1), 4285215 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Biehl, J. K. & Russell, B. Introduction to stem cell therapy. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs.24 (2), 98–103 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Naderi-Meshkin, H., Bahrami, A. R., Bidkhori, H. R., Mirahmadi, M. & Ahmadiankia, N. Strategies to improve homing of mesenchymal stem cells for greater efficacy in stem cell therapy. Cell. Biol. Int.39 (1), 23–34 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Becker, A. & Van Riet, I. Homing and migration of mesenchymal stromal cells: how to improve the efficacy of cell therapy? World J. Stem Cells. 8 (3), 73 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Lucas, B., Pérez, L. M. & Gálvez, B. G. Importance and regulation of adult stem cell migration. J. Cell. Mol. Med.22 (2), 746–754 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liesveld, J. L., Sharma, N. & Aljitawi, O. S. Stem cell homing: from physiology to therapeutics. Stem Cells. 38 (10), 1241–1253 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tao, Z., Tan, S., Chen, W. & Chen, X. Stem cell homing: a potential therapeutic strategy unproven for treatment of myocardial injury. J. Cardiovasc. Transl. Res.11, 403–411 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kholodenko, I. V., Konieva, A. A., Kholodenko, R. V. & Yarygin, K. N. Molecular mechanisms of migration and homing of intravenously transplanted mesenchymal stem cells. J. Regen Med. Tissue Eng.2 (1), 1–4 (2013).24194979 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rahimi, A. et al. Homing and mobilization of hematopoietic stem cells. Archives of Medical Laboratory Sciences.2(4).

- 11.Cui, Y. & Madeddu, P. The role of chemokines, cytokines and adhesion molecules in stem cell trafficking and homing. Curr. Pharm. Design. 17 (30), 3271–3279 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ries, C. et al. MMP-2, MT1-MMP, and TIMP-2 are essential for the invasive capacity of human mesenchymal stem cells: differential regulation by inflammatory cytokines. Blood109 (9), 4055–4063 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Karp, J. M. & Teo, G. S. L. Mesenchymal stem cell homing: the devil is in the details. Cell. Stem Cell.4 (3), 206–216 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kurtz, A. Mesenchymal stem cell delivery routes and fate. Int. J. Stem Cells. 1 (1), 1–7 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yavagal, D. R. et al. Efficacy and dose-dependent safety of intra-arterial delivery of mesenchymal stem cells in a rodent stroke model. PloS One. 9 (5), e93735 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jin, P. et al. (eds) Streptozotocin-induced diabetic rat–derived bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells have impaired abilities in proliferation, paracrine, antiapoptosis, and myogenic differentiation. Transplantation proceedings; : Elsevier. (2010). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Holan, V. et al. The impact of morphine on the characteristics and function properties of human mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cell. Reviews Rep.14, 801–811 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abdyazdani, N. et al. The role of morphine on rat neural stem cells viability, neuro-angiogenesis and neuro-steroidgenesis properties (636,205, 2017). Neurosci. Lett.801, 137158 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Feizy, N. et al. Morphine inhibited the rat neural stem cell proliferation rate by increasing neuro steroid genesis. Neurochem. Res.41, 1410–1419 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lam, C-F. et al. Prolonged use of high-dose morphine impairs angiogenesis and mobilization of endothelial progenitor cells in mice. Anesth. Analgesia. 107 (2), 686–692 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rook, J. M., Hasan, W. & McCarson, K. E. Morphine-induced early delays in wound closure: involvement of sensory neuropeptides and modification of neurokinin receptor expression. Biochem. Pharmacol.77 (11), 1747–1755 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chrastil, J., Sampson, C., Jones, K. B. & Higgins, T. F. Postoperative opioid administration inhibits bone healing in an animal model. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Research®. 471, 4076–4081 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guillamat-Prats, R. The role of MSC in wound healing, scarring and regeneration. Cells10 (7), 1729 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Balaji, S., Keswani, S. G. & Crombleholme, T. M. The role of mesenchymal stem cells in the regenerative wound healing phenotype. Adv. Wound Care. 1 (4), 159–165 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ballantyne, J. C. & LaForge, K. S. Opioid dependence and addiction during opioid treatment of chronic pain. Pain129 (3), 235–255 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Single, E. Estimating the costs of substance abuse: implications to the Estimation of the costs and benefits of gambling. J. Gambl. Stud.19, 215–233 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mercadante, S., Arcuri, E. & Santoni, A. Opioid-induced tolerance and hyperalgesia. CNS Drugs. 33 (10), 943–955 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van Dorp, E. L., Yassen, A. & Dahan, A. Naloxone treatment in opioid addiction: the risks and benefits. Exp. Opin. Drug Saf.6 (2), 125–132 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mannelli, P., Gottheil, E., Peoples, J. F., Oropeza, V. C. & Van Bockstaele, E. J. Chronic very low dose Naltrexone administration attenuates opioid withdrawal expression. Biol. Psychiatry. 56 (4), 261–268 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tsai, R-Y. et al. Ultra-low-dose Naloxone restores the antinociceptive effect of morphine and suppresses spinal neuroinflammation in PTX-treated rats. Neuropsychopharmacology33 (11), 2772–2782 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chou, K-Y. et al. Ultra-low dose (+)-naloxone restores the thermal threshold of morphine tolerant rats. J. Formos. Med. Assoc.112 (12), 795–800 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ahmadianmoghadam, M. A. et al. Effect of an herbal formulation containing peganum Harmala L. and fraxinus excelsior L. on oxidative stress, memory impairment and withdrawal syndrome induced by morphine. Int. J. Neurosci.134 (6), 570–583 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang, H-Y., Friedman, E., Olmstead, M. & Burns, L. Ultra-low-dose Naloxone suppresses opioid tolerance, dependence and associated changes in mu opioid receptor–G protein coupling and Gβγ signaling. Neuroscience135 (1), 247–261 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang, L., Kahn, C.J., Chen, H.Q., Tran, N. & Wang, X. Effect of uniaxial stretching on rat bone mesenchymal stem cell: orientation and expressions of collagen types I and III and tenascin‑C. Cell Biol. Int.32(3), 344–352 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sargazi, M. L. et al. Naringenin attenuates cell viability and migration of C6 glioblastoma cell line: A possible role of Hedgehog signaling pathway. Mol. Biol. Rep.48 (9), 6413–6421 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Asadikaram, G. et al. The study of the serum level of IL-4, TGF‐β, IFN‐γ, and IL‐6 in overweight patients with and without diabetes mellitus and hypertension. J. Cell. Biochem.120 (3), 4147–4157 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mehrabani, M. et al. Protective effect of hydralazine on a cellular model of parkinson’s disease: a possible role of hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-1α. Biochem. Cell Biol.98 (3), 405–414 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ahmadi, Z., Moradabadi, A., Abdollahdokht, D., Mehrabani, M. & Nematollahi, M. H. Association of environmental exposure with hematological and oxidative stress alteration in gasoline station attendants. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res.26, 20411–20417 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Houshyar, H., Gomez, F., Manalo, S., Bhargava, A. & Dallman, M. F. Intermittent morphine administration induces dependence and is a chronic stressor in rats. Neuropsychopharmacology28 (11), 1960–1972 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li, X., Yeh, C-Y. & Bello, N. T. High-fat diet attenuates morphine withdrawal effects on sensory-evoked locus coeruleus norepinephrine neural activity in male obese rats. Nutr. Neurosci.25 (11), 2369–2378 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Allouche, S., Noble, F. & Marie, N. Opioid receptor desensitization: mechanisms and its link to tolerance. Front. Pharmacol.5, 280 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhou, J. et al. Molecular mechanisms of opioid tolerance: from opioid receptors to inflammatory mediators. Experimental Therapeutic Med.22 (3), 1–8 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.BRODIN, E., GAZELIUS, B. & PANOPOULOS, P. Morphine inhibits substance P release from peripheral sensory nerve endings. Acta Physiol. Scand.117 (4), 567–570 (1983). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Crews, F. T. & Nixon, K. Alcohol, neural stem cells, and adult neurogenesis. Alcohol Res. Health. 27 (2), 197 (2003). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Abdyazdani, N. et al. The role of morphine on rat neural stem cells viability, neuro-angiogenesis and neuro-steroidogenesis properties (636,205, 2017). Neurosci. Lett. 801, 137158 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhou, X., Hong, Y., Zhang, H. & Li, X. Mesenchymal stem cell senescence and rejuvenation: current status and challenges. Front. Cell. Dev. Biology. 8, 364 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Farrokhfar, S., Tiraihi, T., Movahedin, M. & Azizi, H. Morphine induces differential gene expression in transdifferentiated Neuron-Like cells from Adipose-Derived stem cells. Biology Bull.49 (Suppl 1), S149–S58 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chhabra, N. & Aks, S. E. Treatment of acute naloxone-precipitated opioid withdrawal with buprenorphine. Am. J. Emerg. Med.38 (3), 691 (2020). e3-. e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Osmanlıoğlu, H. Ö., Yıldırım, M. K., Akyuva, Y., Yıldızhan, K. & Nazıroğlu, M. Morphine induces apoptosis, inflammation, and mitochondrial oxidative stress via activation of TRPM2 channel and nitric oxide signaling pathways in the hippocampus. Mol. Neurobiol.57 (8), 3376–3389 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Willner, D. et al. Short term morphine exposure in vitro alters proliferation and differentiation of neural progenitor cells and promotes apoptosis via mu receptors. PloS One. 9 (7), e103043 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jan, W-C., Chen, C-H., Hsu, K., Tsai, P-S. & Huang, C-J. L-type calcium channels and µ-opioid receptors are involved in mediating the anti-inflammatory effects of Naloxone. J. Surg. Res.167 (2), e263–e72 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shmarina, G. V. et al. Tumor necrosis factor-α/interleukin‐10 balance in normal and cystic fibrosis children. Mediat. Inflamm.10 (4), 191–197 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Peirouvi, T., Mirbaha, Y., Fathi-Azarbayjani, A. & Jalali, A. S. Co-Administration of morphine and naloxone: histopathological and biochemical changes in the rat liver. Int. J. High. Risk Behav. Addict.9(3), e100594 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sengupta, R. et al. Morphine increases brain levels of ferritin heavy chain leading to Inhibition of CXCR4-mediated survival signaling in neurons. J. Neurosci.29 (8), 2534–2544 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wilson, N. M., Jung, H., Ripsch, M. S., Miller, R. J. & White, F. A. CXCR4 signaling mediates morphine-induced tactile hyperalgesia. Brain. Behav. Immun.25 (3), 565–573 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Purssell, R. et al. Comparison of rates of opioid withdrawal symptoms and reversal of opioid toxicity in patients treated with two Naloxone dosing regimens: a retrospective cohort study. Clin. Toxicol.59 (1), 38–46 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Powell, K. J. et al. Paradoxical effects of the opioid antagonist Naltrexone on morphine analgesia, tolerance, and reward in rats. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther.300 (2), 588–596 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gabr, M. M. et al. Interaction of opioids with TLR4—mechanisms and ramifications. Cancers13 (21), 5274 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Burns, L. H. & Wang, H-Y. Ultra-low-dose Naloxone or Naltrexone to improve opioid analgesia: the history, the mystery and a novel approach. Clin. Med. Insights: Ther.2, CMT (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hosseininejad, S. M. et al. Does co-treatment with ultra-low-dose Naloxone and morphine provide better analgesia in renal colic patients? Am. J. Emerg. Med.37 (6), 1025–1032 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available upon reasonable request, and Dr. Hadi Nematollahi should be contacted if someone wants to request the data from this study.