Abstract

Background

Accumulating evidence indicates that elevated maternal glucose concentrations during pregnancy are associated with adverse birth outcomes, but the mechanistic underpinnings remain unclear. This study aimed to evaluate the associations between maternal glucose concentrations and DNA methylation levels in genes related to the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) signaling pathway in the human placenta and explore the potential mediating role of placental DNA methylation in the relationship between maternal glucose concentrations and neonatal anthropometric measures.

Methods

Maternal glucose concentrations were obtained from medical records, and neonatal anthropometric parameters were measured in 335 mother–infant pairs. DNA methylation levels of 14 genes related to the PPAR signaling pathway were analyzed in placental samples. Multiple linear regression models and mediation analyses were used to examine the associations and potential mediation effects.

Results

Higher maternal fasting plasma glucose (FPG) concentrations were generally associated with hypomethylation of genes related to the PPAR signaling pathway, with stronger effects in male neonates. Maternal 1-h plasma glucose concentrations after the glucose challenge test exhibited weaker but consistent patterns. Mediation analyses indicated that hypomethylation of ACAA1 mediated 29.00% (Indirect effect [IE]: β = 0.07; 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.02, 0.14) and 21.75% (IE: β = 0.07; 95% CI 0.00, 0.18) of the effects of FPG concentrations on increased neonatal abdominal and back skinfold thickness, respectively, while ACADM hypomethylation mediated 15.39% (IE: β = 0.03; 95% CI 0.00, 0.08) and 17.69% (IE: β = 0.06; 95% CI 0.00, 0.13) of these effects.

Conclusions

Elevated Maternal glucose concentrations were associated with hypomethylation of genes related to the PPAR signaling pathway. Specifically, hypomethylation of ACAA1 and ACADM may partially mediate the impact of maternal glucose concentrations on increased neonatal anthropometric measures. These findings provide mechanistic insights into potential epigenetic pathways linking maternal glucose concentrations to neonatal anthropometric outcomes.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13148-025-01974-1.

Keywords: Plasma glucose, PPAR signaling pathway, DNA methylation, Placenta

Introduction

Hyperglycemia is a common medical complication of pregnancy worldwide, with its prevalence steadily increasing [1]. Maintaining glucose homeostasis during pregnancy is essential for the health of both the mother and fetus [2, 3]. Studies have shown that elevations in maternal glucose concentrations, even below the diagnostic threshold for gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM), were associated with adverse birth outcomes, such as excessive fetal growth and increased neonatal adiposity [4, 5]. These outcomes may have lasting health implications, including an increased risk of metabolic syndrome and neurodevelopmental deficits [6, 7]. However, the mechanistic underpinnings of the adverse effects of maternal glucose levels on birth outcomes remain poorly understood.

The placenta is a vital organ in pregnancy that mediates maternal–fetal interactions and plays a crucial role in regulating the growth and development of the fetus.[8] As a major epigenetic modification, DNA methylation may reflect adaptation to environmental variations, including maternal metabolic status. It has been proposed as a potential mechanism through which environmental factors influence fetal development. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs), members of the nuclear hormone receptor superfamily, act as ligand-activated transcription factors [9]. The PPAR signaling pathway, which is highly active in the placenta, plays a fundamental role in embryonic implantation and placental development by regulating processes such as lipogenesis, steroidogenesis, and glucose transport [10, 11]. Notably, dysregulation of this pathway has been associated with impaired blood glucose levels in offspring [12]. Our research group previously observed that DNA methylation in genes related to the PPAR signaling pathway tends to be associated with lower neonatal anthropometric measurements [13]. Placental DNA methylation changes in these genes may thus serve as a potential intermediary pathway, helping to elucidate how maternal hyperglycemia may influence fetal growth. Studies have shown that GDM is associated with altered mRNA and protein expressions of PPAR α (PPARA) and PPAR γ (PPARG) in human placentas [14, 15]. However, no research has examined the relationship between maternal glucose concentrations and DNA methylation in genes related to the PPAR signaling pathway in the human placenta. Furthermore, it remains unclear how DNA methylation in these genes might influence the association between maternal glucose concentrations and birth outcomes. Understanding these relationships may provide mechanistic insights into how maternal glucose concentrations could affect fetal growth and adiposity.

Therefore, this study aimed to 1) assess the associations of maternal glucose concentrations with placental DNA methylation in 14 candidate genes related to the PPAR signaling pathway and with neonatal anthropometric measurements, and 2) explore whether placental DNA methylation of these candidate genes may mediate the relationship between maternal glucose concentrations and neonatal anthropometric measures.

Methods

Study participants

The Shanghai-Minhang Birth Cohort Study (S-MBCS) is a longitudinal birth cohort study investigating the influence of prenatal and early postnatal environmental exposures on children’s health outcomes. Between April and December 2012, 1292 pregnant women who attended their first prenatal care visit at the Minhang Maternal and Child Health Center in Shanghai (between 12 and 16 weeks of gestation) and met the inclusion criteria were recruited, which had been reported in detail elsewhere [16, 17]. At enrollment, trained interviewers conducted structured interviews to collect information on parental demographics, medical histories, and lifestyle practices. Gestational age, pregnancy complications, infant birth weight, and sex were obtained from medical records.

Of the 1292 pregnant women, 1225 delivered singleton Live births. Among these, 613 women who delivered during the daytime provided placental tissue samples. Due to financial constraints, DNA methylation levels were assessed in placental tissues of 345 mother–child pairs. Ultimately, 335 mother–infant pairs with complete data on maternal glucose concentrations, placental DNA methylation levels, and neonatal anthropometric measures were included in the study (Fig. S1).

Ethics approval

All participants provided written informed consent, and the study was approved by the ethics committee of the Shanghai Institute for Biomedical and Pharmaceutical Technologies.

Glucose measurement

Maternal glucose concentrations, including fasting plasma glucose (FPG) and 1-h plasma glucose (1h-PG) concentrations following a 50-g oral glucose challenge test (OGCT), were obtained from the medical records of the prenatal care system. Venous blood samples for FPG measurement were collected after overnight fasting, typically within one week of the first antenatal visit (12–20 weeks of gestation). Additionally, participants were advised to undergo the 1 h-PG test following the OGCT between 20 and 28 weeks of gestation. An FPG concentration exceeding 5.1 mmol/L (92 mg/dL) was considered indicative of an increased risk for GDM, while a 1 h-PG concentration of ≥ 7.8 mmol/L (140 mg/dL) served as the threshold for further clinical evaluation [18].

Placental genomic DNA extraction and bisulfite modification

Placental samples were collected at delivery following the removal of the basal and chorionic plates. Full-thickness sections were obtained from the maternal side of the placenta, approximately 2 cm from the umbilical cord-insertion site. The samples were immediately preserved at − 20 °C at the study hospital, transported to the laboratory within 12 h in liquid nitrogen, and subsequently stored at − 80 °C until DNA extraction. Detailed descriptions of the sampling procedure have been reported previously [19]. Genomic DNA was extracted using the High Pure PCR Template Preparation Kit (Roche), followed by bisulfite conversion using the EZ DNA Methylation Kit (Zymo Research, Irvine, CA, USA). This process converts unmethylated cytosine to uracil while preserving methylated cytosine.

Bisulfite amplicon sequencing for methylation analyses

To evaluate DNA methylation, bisulfite amplicon sequencing was performed at CpG sites within the promoter region of 14 candidate genes related to the PPAR signaling pathway. These genes were selected based on their biological functions and detectability in the human placenta, as identified in the National Institutes of Health genetic sequence database and the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes. The selected genes included transcription factor-related genes (retinoid X receptor γ [RXRG], RXR β [RXRB], RXR α [RXRA], PPARG, and PPARA), fatty acid oxidation-related genes (sterol carrier protein 2 [SCP2], carnitine palmitoyl transferase 2 [CPT2], carnitine palmitoyl transferase 1 A [CPT1A], acyl-CoA oxidase 1 [ACOX1], acyl-CoA dehydrogenase medium chain [ACADM], acyl-CoA dehydrogenase long chain [ACADL], and acetyl-CoA acyltransferase 1 [ACAA1]), lipid transport-related gene (phospholipid transfer protein [PLTP]), and cholesterol metabolism-related gene (nuclear receptor subfamily 1 group H member 3 [NR1H3]). Primers and target sequences were designed using MethPrimer 2.0 (Table S1). Next-generation sequencing libraries were constructed using PCR-amplified bisulfite-converted DNA. Methylation quantification was performed using Illumina MiSeq PE300 high-throughput sequencing (Illumina, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA), with quality control carried out via FastQC. Methylation levels at each CpG site were determined by calculating the percentage of methylated cytosines relative to the total cytosines (methylated and unmethylated).

Neonatal anthropometric measures

Birth weight was obtained from medical birth records. Arm and abdominal circumferences, as well as skinfold thicknesses (triceps, abdominal, and back), were measured by a trained physician using standardized protocols within 3 days of delivery. Arm circumference was measured on the right side with a tape measure positioned midway between the acromion and olecranon. Abdominal circumference was taken around the abdomen at the umbilical level after normal exhalation. Skinfold thickness was measured at three standardized sites (triceps, abdomen, and back) on the right side using a skinfold caliper, with the neonates in a relaxed state, as commonly employed in prior research.[20, 21] Birth weight was recorded to the nearest gram, and circumferences and skinfold thicknesses were measured to an accuracy of 0.1 cm and 0.1 mm, respectively.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were presented as means ± standard deviations for continuous variables and counts with percentages for categorical variables. Chi-square tests and analysis of variance were used to compare categorical and continuous variables across maternal glucose groups.

Spearman correlation coefficients were calculated for DNA methylation levels at CpG sites within each gene, with results visualized in a heatmap (Fig. S2). Linear regression models were used to evaluate associations between maternal glucose concentrations (FPG and 1 h-PG) and DNA methylation levels at each CpG site. Since the above associations within each gene generally showed consistent patterns (Table S2), the average methylation level for each gene was used in subsequent analyses. Natural logarithmic (ln) transformation was applied to methylation levels for most genes (excluding RXRA, ACOX1, CPT2, and SCP2) to achieve normality. Multiple linear regression models were employed to assess the relationships among maternal glucose concentrations, DNA methylation levels (averages), and neonatal anthropometric measures. Sex-stratified analyses were conducted to examine potential modification effects by neonatal sex. Additionally, to enhance clarity and robustness, we re-examined the relationships between maternal glucose levels and DNA methylation by treating FPG concentrations as a categorical variable, categorized by tertiles (< 3.9, 3.9–4.1, and ≥ 4.2 mmol/L).

Mediation analyses were performed to evaluate whether DNA methylation of the candidate genes in the human placenta mediated the associations between maternal glucose concentrations and neonatal anthropometric measures, providing that the relationships among maternal glucose concentrations, DNA methylation, and neonatal anthropometric measures were all significant. Due to the limited sample size, sex-specific analyses were not performed. The total effect of maternal glucose concentrations on neonatal anthropometric measures was decomposed into direct effect and indirect effect through DNA methylation. The total, direct, and indirect effects were calculated using the mediation package in R [22]. The proportion of mediation was calculated as the ratio of the indirect effect to the total effect.

Potential confounders were identified based on prior research [23, 24]. Covariates that altered coefficients of interest by > 10% were retained. Finally, the following covariates were included in all models: maternal age at delivery (≤ 25, 25–29, and ≥ 30 years), maternal pre-pregnancy body mass index (BMI) (< 18.5, 18.5–24.9 and 25–29.9 kg/m2), household income per capita (< 4000, 4000–7999, and ≥ 8000 Chinese Yuan [CNY]/month), maternal education (high school or less, college or above), maternal passive smoking before gestation (yes/no), gestational age, parity (nulliparous/parous), and infant sex (male, female). Additionally, gestational week at the time of maternal glucose measurement was included in the analysis examining the relationship between maternal glucose concentrations and both DNA methylation of the candidate genes and neonatal anthropometric measurements. Gestational weight gain (< 10.0, 10.0–19.9, and ≥ 20.0 kg) was also considered when investigating the relationships between maternal glucose and neonatal anthropometric measurements.

All statistical tests were two-sided, with the significance threshold established at 0.05. Analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC) and R version 3.5.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

Participant characteristics

Among the 335 mothers included in the study, the mean gestational age was 39.7 ± 1.1 weeks. Over half (54.6%) were aged 25–29 years at enrollment, and 54.0% delivered male infants. The majority had a pre-pregnancy BMI within the normal range (18.5–24.9 kg/m2, 75.1%), held a college degree or higher (76.0%), gained 10.0–19.9 kg during pregnancy (72.7%), and were nulliparous (87.2%). Approximately 40% reported a monthly household income per capita of 4000–7999 CNY and exposure to passive smoking before conception (Table 1). No significant differences were observed in these characteristics across maternal FPG tertiles. Mother–child pairs included in the study exhibited similar characteristics to those excluded, with slight differences in gestational weight gain and gestational age (Table S3).

Table 1.

Characteristics of mothers and infants by maternal FPG tertiles#

| Characteristics | Total (N = 335) |

Lowest tertilea (N = 101) |

Middle tertileb (n = 126) |

Highest tertilec (n = 108) |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal age, years: n (%) | 0.34 | ||||

| < 25 | 60 (17.9) | 21 (20.8) | 19 (15.1) | 20 (18.5) | |

| 25–29 | 183 (54.6) | 56 (55.4) | 75 (59.5) | 52 (48.1) | |

| ≥ 30 | 92 (27.5) | 24 (23.8) | 32 (25.4) | 36 (33.3) | |

| Pre-pregnancy BMI, kg/m2: n (%) | 0.70 | ||||

| < 18.5 | 66 (20.1) | 23 (23.5) | 25 (20.3) | 18 (16.7) | |

| 18.5–24.9 | 247 (75.1) | 71 (72.4) | 93 (75.6) | 83 (76.9) | |

| ≥ 25.0 | 16 (4.9) | 4 (4.1) | 5 (4.1) | 7 (6.5) | |

| Maternal education: n (%) | 0.54 | ||||

| High school or less | 80 (24.0) | 26 (25.7) | 26 (20.6) | 28 (26.2) | |

| College or above | 254 (76.0) | 75 (74.3) | 100 (79.4) | 79 (73.8) | |

| Household income per capita, (CNY/month): n (%) | 0.99 | ||||

| < 4000 | 71 (21.3) | 23 (23.0) | 25 (20.0) | 23 (21.3) | |

| 4000–7999 | 146 (43.8) | 43 (43.0) | 56 (44.8) | 47 (43.5) | |

| ≥ 8000 | 116 (34.8) | 34 (34.0) | 44 (35.2) | 38 (35.2) | |

| Maternal passive smoking before gestation: n (%) | 0.90 | ||||

| Yes | 139 (41.6) | 41 (40.6) | 54 (43.2) | 44 (40.7) | |

| No | 195 (58.4) | 60 (59.4) | 71 (56.8) | 64 (59.3) | |

| Gestational weight gain, kg: n (%) | 0.39 | ||||

| < 10.0 | 12 (3.6) | 3 (3.0) | 5 (4.0) | 4 (3.7) | |

| 10.0–19.9 | 242 (72.7) | 68 (68.0) | 89 (71.2) | 85 (78.7) | |

| ≥ 20.0 | 79 (23.7) | 29 (29.0) | 31 (24.8) | 19 (17.6) | |

| Parity: n (%) | 0.53 | ||||

| Nulliparous | 292 (87.2) | 90 (89.1) | 111 (88.1) | 91 (84.3) | |

| Parous | 43 (12.8) | 11 (10.9) | 15 (11.9) | 17 (15.7) | |

| Gestational age: mean (SD), weeks | 39.7 (1.1) | 39.6 (1.0) | 39.7 (1.2) | 39.8 (1.2) | 0.71 |

| Infant sex: n (%) | 0.20 | ||||

| Male | 181 (54.0) | 52 (51.5) | 63 (50.0) | 66 (61.1) | |

| Female | 154 (46.0) | 49 (48.5) | 63 (50.0) | 42 (38.9) |

FPG, fasting plasma glucose; BMI, body mass index; CNY, Chinese Yuan; SD, standard deviation

#The maternal fasting plasma glucose concentrations were divided into three groups according to the tertiles, and the cut-off points of the tertiles were 3.9 mmol/L and 4.2 mmol/L, respectively

aThere were 3 missing values in pre-pregnancy BMI, 1 missing value in household income per capita, and 1 missing value in gestational weight gain

bThere were 3 missing values in pre-pregnancy BMI, 1 missing value in household income per capita, 1 missing value in maternal passive smoking before gestation, and 1 missing value in gestational weight gain

cThere was 1 missing value in maternal education

Descriptive statistics of maternal glucose concentrations, DNA Methylation levels, and neonatal anthropometric measures

Figure S3 displays the distribution of maternal glucose concentrations. The mean FPG and 1 h-PG concentrations were 4.0 and 6.6 mmol/L, respectively. Two mothers (0.6%) had FPG concentrations exceeding 5.1 mmol/L, while 67 mothers (20.9%) had 1 h-PG concentrations of ≥ 7.8 mmol/L. Table S4 presents DNA methylation levels for 14 candidate genes, with RXRG showing the highest median methylation level (8.73%), followed by CPT1A (4.16%) and PPARG (1.97%). DNA methylation levels at individual CpG sites within each gene were found to correlate with the average methylation levels of the corresponding gene (r = 0.14–0.98, P < 0.05), except PPARA, for which the correlation coefficients varied between 0.02 and 0.82 (Table S5). Neonatal anthropometric measurements revealed mean values of 3462 ± 441 g for birth weight, 11.1 ± 2.0 cm for arm circumference, 33.6 ± 2.5 cm for abdominal circumference, 4.1 ± 1.1 mm for triceps skinfold thickness, 2.6 ± 0.7 mm for abdominal skinfold thickness, and 4.1 ± 1.0 mm for back skinfold thickness.

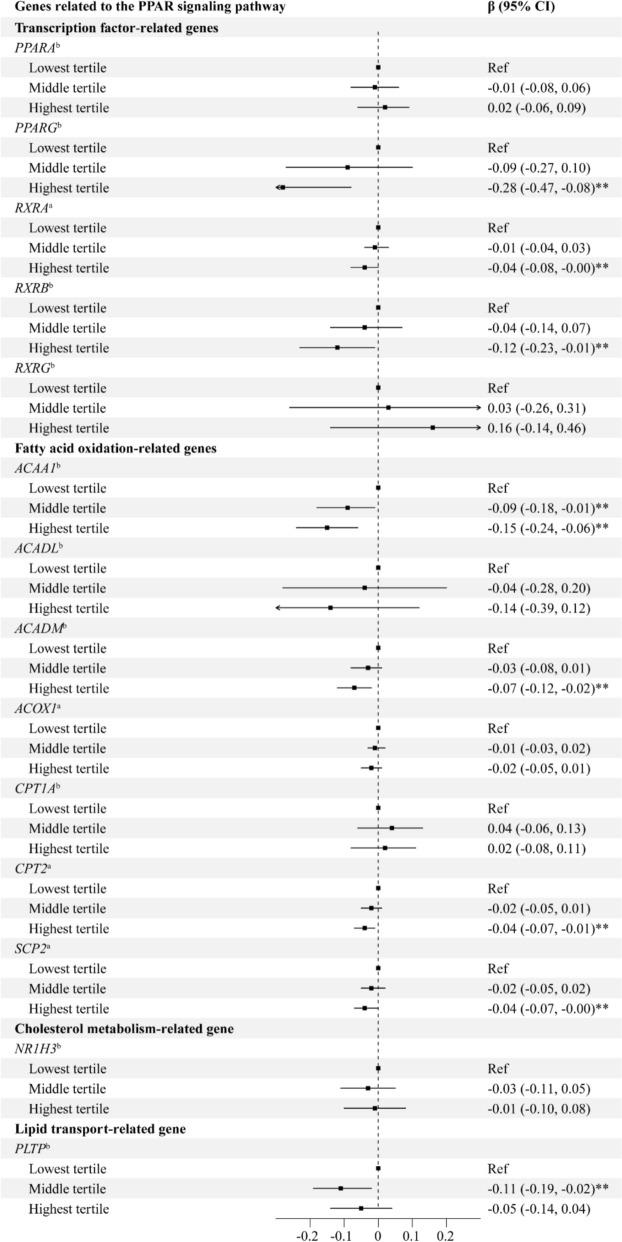

Associations between maternal glucose concentrations and DNA methylation levels of candidate genes

Associations between maternal glucose concentrations and CpG site-specific DNA methylation levels exhibited a consistent pattern (Table S2). Higher maternal FPG concentrations were generally inversely associated with DNA methylation levels of candidate genes (Table 2). Significant associations were observed for PPARG (β = − 0.31, 95% confidence interval [CI] − 0.51, − 0.11), ACAA1 (β = − 0.19, 95% CI − 0.29, − 0.10), ACADM (β = − 0.07, 95% CI − 0.12, − 0.02), and CPT2 (β = − 0.04, 95% CI − 0.07, − 0.00). Analysis of FPG tertiles showed similar patterns of inverse associations (Fig. 1), with the highest tertile associated with significantly decreased methylation levels in PPARG (β = − 0.28, 95% CI − 0.47, − 0.08), ACAA1(β = − 0.15, 95% CI − 0.24, − 0.06), RXRB (β = − 0.12, 95% CI − 0.23, − 0.01), ACADM (β = − 0.07, 95% CI − 0.12, − 0.02), RXRA (β = − 0.04, 95% CI − 0.08, − 0.00), CPT2 (β = − 0.04, 95% CI − 0.07, − 0.01), and SCP2 (β = − 0.04, 95% CI − 0.07, − 0.00) compared to the Lowest tertile. There were no associations of maternal 1 h-PG concentrations with DNA methylation, except that decreased DNA methylation levels in RXRB (β = − 0.04, 95% CI − 0.07, 0.00) and NR1H3 (β = − 0.03, 95% CI − 0.06, 0.00) with borderline statistical significance were observed (Table 2).

Table 2.

Associations between maternal glucose concentrations and DNA methylation of genes related to the PPAR signaling pathway in the human placenta#

| Genes related to the PPAR signaling pathway | β (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|

| FPG concentrations | 1 h-PG concentrations | |

| Transcription factor-related genes | ||

| PPARAb | 0.03 (− 0.05, 0.11) | 0.00 (− 0.02, 0.03) |

| PPARGb | − 0.31 (− 0.51, − 0.11)** | 0.04 (− 0.03, 0.10) |

| RXRAa | − 0.04 (− 0.08, 0.00)* | 0.01 (− 0.01, 0.02) |

| RXRBb | − 0.11 (− 0.22, 0.01)* | − 0.04 (− 0.07, 0.00)* |

| RXRGb | 0.20 (− 0.11, 0.51) | − 0.02 (− 0.12, 0.08) |

| Fatty acid oxidation-related genes | ||

| ACAA1b | − 0.19 (− 0.29, − 0.10)** | − 0.01 (− 0.04, 0.02) |

| ACADLb | − 0.06 (− 0.33, 0.21) | 0.04 (− 0.05, 0.13) |

| ACADMb | − 0.07 (− 0.12, − 0.02)** | − 0.01 (− 0.03, 0.01) |

| ACOX1a | − 0.02 (− 0.06, 0.01) | 0.01 (− 0.00, 0.02) |

| CPT1Ab | 0.01 (− 0.10, 0.11) | 0.01 (− 0.02, 0.04) |

| CPT2a | − 0.04 (− 0.07, − 0.00)** | 0.01 (− 0.00, 0.02) |

| SCP2a | − 0.02 (− 0.06, 0.01) | 0.01 (− 0.00, 0.02) |

| Cholesterol metabolism-related genes | ||

| NR1H3b | 0.00 (− 0.09, 0.09) | − 0.03 (− 0.06, 0.00)* |

| Lipid transport-related genes | ||

| PLTPb | − 0.04 (− 0.14, 0.05) | 0.01 (− 0.01, 0.04) |

PPAR, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors; FPG, fasting plasma glucose; 1h-PG, one-hour plasma glucose; CI, confidence interval

#The models were adjusted for maternal age, pre-pregnancy BMI, maternal education, household income per capita, maternal passive smoking before gestation, parity, gestational age, infant sex, and gestational week at the time of maternal glucose measurement

aThe DNA methylation levels were not ln-transformed

bThe DNA methylation levels were ln-transformed

*0.05 ≤ P < 0.1

** P < 0.05

Fig. 1.

Associations between FPG tertiles and DNA methylation of genes related to the PPAR signaling pathway in the human placenta#. Abbreviations: FPG, fasting plasma glucose; PPAR, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors; CI, confidence interval; Ref, reference. # The models were adjusted for maternal age, pre-pregnancy BMI, maternal education, household income per capita, maternal passive smoking before gestation, parity, gestational age, infant sex, and gestational week at the time of maternal glucose measurement. aThe DNA methylation levels were not ln-transformed. bThe DNA methylation levels were ln-transformed. ** P < 0.05

Although most sex interaction terms did not reach statistical significance, the associations between maternal FPG concentrations and decreased DNA methylation levels of PPAR genes appeared to be stronger in women carrying male fetuses (Table 3). Additionally, higher maternal FPG concentrations were associated with decreased RXRA methylation in male infants (β = − 0.08, 95% CI − 0.14, − 0.03).

Table 3.

Associations between maternal glucose concentrations and DNA methylation of genes related to the PPAR signaling pathway in the human placenta by infant sex#

| PPAR signaling pathway-related genes | FPG concentrations | 1 h-PG concentrations | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | P for interaction | Male | Female | P for interaction | |

| β (95% CI) | β (95% CI) | β (95% CI) | β (95% CI) | |||

| Transcription factor-related genes | ||||||

| PPARAb | 0.01 (− 0.10, 0.12) | 0.07 (− 0.04, 0.18) | 0.58 | 0.03 (− 0.01, 0.07) | − 0.01 (− 0.05, 0.02) | 0.04 |

| PPARGb | − 0.52 (− 0.81, − 0.24)** | − 0.05 (− 0.34, 0.23) | 0.01 | 0.02 (− 0.07, 0.11) | 0.06 (− 0.03, 0.16) | 0.73 |

| RXRAa | − 0.08 (− 0.14, − 0.03)** | − 0.00 (− 0.05, 0.05) | 0.13 | 0.01 (− 0.01, 0.03) | 0.01 (− 0.01, 0.02) | 0.84 |

| RXRBb | − 0.14 (− 0.31, 0.02)* | − 0.09 (− 0.26, 0.08) | 0.72 | − 0.05 (− 0.11, 0.00)* | − 0.03 (− 0.08, 0.03) | 0.29 |

| RXRGb | 0.42 (0.01, 0.83)* | 0.00 (− 0.50, 0.50) | 0.15 | 0.08 (− 0.07, 0.22) | − 0.12 (− 0.27, 0.04) | 0.09 |

| Fatty acid oxidation-related genes | ||||||

| ACAA1b | − 0.15 (− 0.29, − 0.01)** | − 0.26 (− 0.39, − 0.13)** | 0.14 | 0.02 (− 0.03, 0.07) | − 0.02 (− 0.07, 0.02) | 0.13 |

| ACADLb | − 0.01 (− 0.39, 0.38) | − 0.13 (− 0.52, 0.26) | 0.54 | − 0.00 (− 0.13, 0.13) | 0.06 (− 0.06, 0.19) | 0.51 |

| ACADMb | − 0.12 (− 0.19, − 0.04)** | − 0.03 (− 0.10, 0.04) | 0.13 | − 0.00 (− 0.03, 0.02) | − 0.01 (− 0.04, 0.01) | 0.55 |

| ACOX1a | − 0.03 (− 0.08, 0.01) | − 0.02 (− 0.07, 0.02) | 0.98 | 0.01 (− 0.01, 0.02) | 0.00 (− 0.01, 0.02) | 0.58 |

| CPT1Ab | −0.06 (− 0.19, 0.08) | 0.07 (− 0.10, 0.23) | 0.35 | − 0.00 (− 0.05, 0.05) | 0.02 (− 0.03, 0.07) | 0.43 |

| CPT2a | − 0.04 (− 0.08, 0.01)* | − 0.05 (− 0.10, − 0.00)** | 0.52 | 0.01 (− 0.00, 0.03) | 0.01 (− 0.01, 0.02) | 0.74 |

| SCP2a | − 0.04 (− 0.09, 0.00)* | − 0.01 (− 0.06, 0.04) | 0.27 | 0.01 (− 0.00, 0.03) | 0.01 (− 0.01, 0.02) | 0.4 |

| Cholesterol metabolism-related genes | ||||||

| NR1H3b | − 0.10 (− 0.22, 0.01)* | 0.10 (− 0.04, 0.24) | 0.09 | − 0.02 (− 0.06, 0.02) | − 0.03 (− 0.08, 0.01) | 0.72 |

| Lipid transport-related genes | ||||||

| PLTPb | − 0.10 (− 0.24, 0.04) | 0.01 (− 0.12, 0.14) | 0.32 | 0.03 (− 0.02, 0.08) | 0.00 (− 0.03, 0.03) | 0.24 |

PPAR, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors; FPG, fasting plasma glucose; 1h-PG, one-hour plasma glucose; CI, confidence interval

#The models were adjusted for maternal age, pre-pregnancy BMI, maternal education, household income per capita, maternal passive smoking before gestation, parity, gestational age, and gestational week at the time of maternal glucose measurement

aThe DNA methylation levels were not ln-transformed

bThe DNA methylation levels were ln-transformed

*0.05 ≤ P < 0.1

**P < 0.05

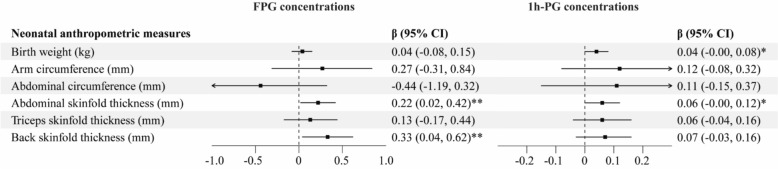

Associations between maternal glucose concentrations and neonatal anthropometric measurements, and between DNA methylation and neonatal anthropometric measurements

Higher maternal FPG concentrations were significantly associated with increased abdominal skinfold thickness (β = 0.22, 95% CI 0.02, 0.42) and back skinfold thickness (β = 0.33, 95% CI 0.04, 0.62) (Fig. 2). For 1 h-PG concentrations, borderline-significant associations were observed with higher birth weight (β = 0.04, 95% CI − 0.00, 0.08) and abdominal skinfold thickness (β = 0.06, 95% CI − 0.00, 0.12). Similar results were found in sex-stratified analyses (Table S6).

Fig. 2.

Associations between maternal glucose concentrations and neonatal anthropometric measures. Abbreviations: FPG, fasting plasma glucose; 1h-PG, 1-hour plasma glucose; CI, confidence interval. # The models were adjusted for maternal age, pre-pregnancy BMI, maternal education, household income per capita, maternal passive smoking before gestation, parity, gestational age, infant sex, gestational week at the time of maternal glucose measurement, and gestational weight gain. * 0.05 ≤ P < 0.1. ** P < 0.05

Consistent with our previous study [13], we observed that DNA methylation levels of RXRA, ACAA1, ACADM, ACOX1, CPT2, and NR1H3 were generally associated with lower neonatal anthropometric measurements. These associations remained generally consistent when stratified by infant sex (Table S7).

Mediation analyses

Based on the results above, DNA methylation levels of ACAA1, ACADM, and CPT2 were selected as potential mediators in the relationship between FPG concentrations and neonatal abdominal skinfold thickness. ACAA1 and ACADM methylation levels were also examined as mediators for the association between FPG concentrations and neonatal back skinfold thickness.

Mediation analyses showed that changes in ACAA1 methylation mediated 29.00% (Indirect effect [IE]: β = 0.07; 95% CI 0.02, 0.14) of the effect of FPG concentrations on neonatal abdominal skinfold thickness and 21.75% (IE: β = 0.07; 95% CI 0.00, 0.18) on neonatal back skinfold thickness. Similarly, changes in ACADM methylation mediated 15.39% (IE: β = 0.03; 95% CI 0.00, 0.08) and 17.69% (IE: β = 0.06; 95% CI 0.00, 0.13) of the effects of FPG concentrations on neonatal abdominal and back skinfold thickness, respectively (Table 4). Although not statistically significant (0.05 ≤ P < 0.1), changes in CPT2 methylation potentially mediate the effects of FPG concentrations on neonatal abdominal skinfold thickness, with a mediation proportion of 11.38% (IE: β = 0.03; 95% CI − 0.00, 0.07) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Mediation analysis of the estimated effect of maternal glucose concentrations and neonatal anthropometric measures mediated by DNA methylation of genes related to the PPAR signaling pathway in the human placenta#

| Analyses | Total effect | Indirect effect | Direct effect | Proportion mediated (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β (95% CI) | β (95% CI) | β (95% CI) | ||

| FPG concentrations | ||||

| Abdominal skinfold thickness | ||||

| ACAA1b | 0.23 (0.00, 0.47)* | 0.07 (0.02, 0.14)** | 0.16 (−0.07, 0.40) | 29.00 |

| ACADMb | 0.22 (0.01, 0.43)** | 0.03 (0.00, 0.08)** | 0.19 (−0.03, 0.40) | 15.39 |

| CPT2a | 0.23 (0.01, 0.46)** | 0.03 (−0.00, 0.07)* | 0.21 (−0.02, 0.43)* | 11.38 |

| Back skinfold thickness | ||||

| ACAA1b | 0.32 (0.05, 0.58)** | 0.07 (0.00, 0.18)** | 0.25 (−0.04, 0.52)* | 21.75 |

| ACADMb | 0.33 (0.03, 0.61)** | 0.06 (0.00, 0.13)** | 0.27 (−0.04, 0.55)* | 17.69 |

PPAR, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors; FPG, fasting plasma glucose; CI, confidence interval

#The models were adjusted for maternal age, pre-pregnancy BMI, maternal education, household income per capita, maternal passive smoking before gestation, parity, gestational age, infant sex, gestational week at the time of maternal glucose measurement, and gestational weight gain

aThe DNA methylation levels were not ln-transformed

bThe DNA methylation levels were ln-transformed

* 0.05 ≤ P < 0.1

** P < 0.05

Discussion

In this study, we found that elevated maternal glucose concentrations were generally associated with Lower DNA methylation levels in candidate genes, with more pronounced effects observed in male neonates. Additionally, maternal glucose concentrations were positively associated with increased neonatal anthropometric measures. Notably, approximately 29% and 22% of the effects of FPG concentrations on neonatal abdominal and back skinfold thickness, respectively, could be attributed to the mediation effect of changes in ACAA1 methylation. Similarly, about 15% and 18% of these effects were mediated by alterations in ACADM methylation.

Similar to previous studies, [25, 26], higher maternal glucose concentrations were associated with increased neonatal abdominal and back skinfold thickness. Elevated maternal glucose concentrations during pregnancy were associated with adverse birth outcomes, including excessive fetal growth and increased neonatal adiposity [4, 5, 25]. Importantly, maternal glucose concentrations below the diagnostic threshold for GDM, as defined by the American Diabetes Association, have also been associated with increased childhood adiposity [27]. This suggests that even a slight increase in maternal glycemia may have significant long-term health implications for offspring, underscoring the importance of implementing preventive measures whenever possible.

To our knowledge, this study is the first to evaluate the associations between maternal glucose concentrations and DNA methylation in genes related to the PPAR signaling pathway in the human placenta. Specifically, we found that FPG concentrations were inversely associated with PPARG DNA methylation levels. The PPARG gene encodes a member of the PPAR subfamily of nuclear receptors, playing a crucial role in placental development and regulating lipid metabolism and anti-inflammatory pathways [28]. Abnormal expression of PPARG was associated with obesity and diabetes [29]. PPARG was found to be upregulated in peripheral blood mononuclear cells of women with GDM [30], and leukocyte PPARG mRNA levels were significantly higher in women with GDM compared to healthy controls [31]. Moreover, a study on Australian women with GDM showed an increase in PPARG gene expression in their placentas [32]. Our findings suggest that PPARG may contribute to abnormal placental development under conditions of elevated maternal glucose.

In addition to PPARG, we found inverse associations between maternal FPG concentrations and DNA methylation in ACAA1, ACADM, and CPT2. These genes, activated by the PPAR-RXR heterodimer, are critical for lipid metabolism [33]. Placental lipid metabolism is essential for placental function, pregnancy outcomes, and fetal development [34]. Impaired placental lipid metabolism, including reduced fatty acid oxidation, may lead to the accumulation of cytotoxic metabolites and placental insufficiency, increasing the risk of fetal growth restriction and preterm birth [35]. Altered methylation of ACAA1, ACADM, and CPT2 could disrupt placental lipid metabolism, potentially affecting maternal and fetal health.

Previous research has shown that elevated glucose levels disrupt the metabolic partitioning of fatty acids in the human placenta, shifting fatty acid flux from oxidation to esterification and resulting in the accumulation of placental triglycerides [36]. Additionally, studies have reported alterations in placental lipid metabolism among women with diabetes [37, 38]. In our study, we found that the methylation levels of ACAA1 and ACADM partially mediated the association between maternal glucose concentrations and neonatal skinfold thickness. Hypomethylation, which typically indicates enhanced or activated gene expression, suggests that mother-neonate pairs with decreased methylation of genes related to the PPAR signaling pathway, induced by higher maternal glucose levels, may exhibit elevated lipid concentrations. These increased lipid levels could contribute to greater neonatal adiposity, offering a mechanistic explanation for the inverse relationship observed between placental DNA methylation in genes related to the PPAR signaling pathway and neonatal anthropometric measures. These findings provide mechanistic insights into the molecular mechanisms underlying fetal programming and the development of adiposity. Moreover, identifying specific pathways, such as ACAA1 methylation, that mediate these associations could inform targeted interventions to reduce the risks associated with maternal hyperglycemia.

Our findings suggested that the relationship between maternal glucose concentrations and DNA methylation in candidate genes may differ by infant sex. Previous research has reported sex-specific DNA methylation patterns in the PGC1A promoter of placentas from mothers with diabetes (including GDM and pregestational type 2 diabetes).[39] Although the underlying mechanisms remain unclear, sex-specific differences in placental structure, function, and responses to environmental stress may provide plausible explanations.[40] Further research is warranted to elucidate the phenomenon and uncover the mechanisms involved.

Strengths and limitations

This study is the first to establish an association between maternal glucose concentrations and placental DNA methylation of genes related to the PPAR signaling pathway. The prospective cohort design and abundant covariate information enhance the credibility of our findings. However, several limitations must be acknowledged. First, the study population consisted of a subset of the participants from the S-MBCS, which could introduce selection bias. Nonetheless, the included participants were comparable to those excluded concerning key characteristics such as age, pre-pregnancy BMI, household income, education, household income, passive smoking before gestation, parity and infant sex. Therefore, a substantial selection bias was not anticipated. Second, neonatal anthropometric measurements were performed only once by a physician. Although previous research has demonstrated high reliability for these measurements [41], a single measurement may introduce error and bias the associations toward the null. Third, the potential variance arising from the placenta’s heterogeneous structure cannot be ignored. To minimize this variability, we established a standardized process for sampling and analysis, which included consistent sampling locations (distance from the cord and biopsy depth from the surface) and time from placental delivery to sampling. While our measures likely mitigated technical noise, they cannot fully eliminate biological variance inherent to placental research. Future studies should incorporate spatial transcriptomics or laser-capture microdissection to resolve compartment-specific effects. Additionally, the study population consisted of relatively healthy participants, with only two mothers (0.6%) exhibiting FPG concentrations above 5.1 mmol/L. This limited variability may affect the generalizability of our findings. Finally, the relatively small sample size may have limited the statistical power to detect associations and reduced the precision of our estimates. More high-quality evidence is needed to confirm and expand upon our results.

Conclusions

Maternal glucose concentrations were generally associated with decreased placental DNA methylation of genes related to the PPAR signaling pathway. Furthermore, changes in the methylation of ACAA1 and ACADM were identified as potential mediators in the relationship between maternal FPG concentrations and increased neonatal anthropometrics. These findings provide additional insight into the mechanisms through which maternal glucose concentrations may influence neonatal adiposity.

Supplementary Information

Author contributions

L.L. and L.Z. contributed equally to this study. L.L., L.Z., M.L., H.J. and M.M.: conceived and designed the study. L.L., L.Z., M.L. and H.J.: obtained data, performed analyses and interpretation, and drafted the manuscript. Y.C., F.Y., X.S., H.L., W.Y., and M.M.: provided professional and statistical support, and made critical revisions. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. M.L. and H.J. acted as the guarantor of this work.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Numbers: 22406132, 22276125, and 82404275), the Innovation Promotion Program of NHC and Shanghai Key Labs, SIBPT (Grant Number: RC2024-05), the three-year action plan for strengthening the construction of the public health system in Shanghai (Grant Number: GWVI-11.2-YQ24) and the Shanghai Sixth People’s Hospital Grant Award (Grant Number: ynqn202425).

Availability of data and materials

The data used for this study will be made available upon request.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study has been approved by the ethics committee of the Shanghai Institute for Biomedical and Pharmaceutical Technologies. All participants provided written informed consent before enrolment. The Declaration of Helsinki has been followed throughout the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Honglei Ji, Email: hongleijish@163.com.

Min Luan, Email: min.luan@sjtu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Shah NS, Wang MC, Freaney PM, Perak AM, Carnethon MR, Kandula NR, et al. Trends in gestational diabetes at first live birth by race and ethnicity in the US, 2011–2019. JAMA. 2021;326(7):660–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Skyler JS, O’Sullivan MJ, Robertson EG, Skyler DL, Holsinger KK, Lasky IA, et al. Blood glucose control during pregnancy. Diabetes Care. 1980;3(1):69–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li M, Hinkle SN, Grantz KL, Kim S, Grewal J, Grobman WA, et al. Glycaemic status during pregnancy and longitudinal measures of fetal growth in a multi-racial US population: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020;8(4):292–300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Group HSCR, Metzger BE, Lowe LP, Dyer AR, Trimble ER, Chaovarindr U, et al. Hyperglycemia and adverse pregnancy outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(19):1991–2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Catalano PM, McIntyre HD, Cruickshank JK, McCance DR, Dyer AR, Metzger BE, et al. The hyperglycemia and adverse pregnancy outcome study: associations of GDM and obesity with pregnancy outcomes. Diabetes Care. 2012;35(4):780–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jerome ML, Valcarce V, Lach L, Itriago E, Salas AA. Infant body composition: a comprehensive overview of assessment techniques, nutrition factors, and health outcomes. Nutr Clin Pract. 2023;38(Suppl 2(Suppl 2)):S7-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Feig DS, Artani A, Asaf A, Li P, Booth GL, Shah BR. Long-term neurobehavioral and metabolic outcomes in offspring of mothers with diabetes during pregnancy: a large, population-based cohort study in Ontario, Canada. Diabetes Care. 2024;47(9):1568–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Robins JC, Marsit CJ, Padbury JF, Sharma SS. Endocrine disruptors, environmental oxygen, epigenetics and pregnancy. Front Biosci (Elite Ed). 2011;3(2):690–700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dubois V, Eeckhoute J, Lefebvre P, Staels B. Distinct but complementary contributions of PPAR isotypes to energy homeostasis. J Clin Invest. 2017;127(4):1202–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fournier T, Tsatsaris V, Handschuh K, Evain-Brion D. Ppars and the placenta. Placenta. 2007;28(2–3):65–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Murthi P, Kalionis B, Cocquebert M, Rajaraman G, Chui A, Keogh RJ, et al. Homeobox genes and down-stream transcription factor PPARgamma in normal and pathological human placental development. Placenta. 2013;34(4):299–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhao Q, Yang D, Gao L, Zhao M, He X, Zhu M, et al. Downregulation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma in the placenta correlates to hyperglycemia in offspring at young adulthood after exposure to gestational diabetes mellitus. J Diabetes Investig. 2019;10(2):499–512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen Y, Huang B, Liang H, Ji H, Wang Z, Song X, et al. Gestational organophosphate esters (OPEs) exposure in association with placental DNA methylation levels of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs) signaling pathway-related genes. Sci Total Environ. 2024;947:174569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Balachandiran M, Bobby Z, Dorairajan G, Jacob SE, Gladwin V, Vinayagam V, et al. Placental accumulation of triacylglycerols in gestational diabetes mellitus and its association with altered fetal growth are related to the differential expressions of proteins of lipid metabolism. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 2021;129(11):803–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gao Y, She R, Sha W. Gestational diabetes mellitus is associated with decreased adipose and placenta peroxisome proliferator-activator receptor gamma expression in a Chinese population. Oncotarget. 2017;8(69):113928–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ji H, Liang H, Wang Z, Miao M, Wang X, Zhang X, et al. Associations of prenatal exposures to low levels of Polybrominated Diphenyl Ether (PBDE) with thyroid hormones in cord plasma and neurobehavioral development in children at 2 and 4 years. Environ Int. 2019;131:105010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sun X, Liu C, Liang H, Miao M, Wang Z, Ji H, et al. Prenatal exposure to residential PM(2.5) and its chemical constituents and weight in preschool children: a longitudinal study from Shanghai, China. Environ Int. 2021;154:106580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jagannathan R, Neves JS, Dorcely B, Chung ST, Tamura K, Rhee M, et al. The oral glucose tolerance test: 100 years later. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2020;13:3787–805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xie Z, Sun S, Ji H, Miao M, He W, Song X, et al. Prenatal exposure to per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances and DNA methylation in the placenta: a prospective cohort study. J Hazard Mater. 2024;463:132845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Olutekunbi OA, Solarin AU, Senbanjo IO, Disu EA, Njokanma OF. Skinfold thickness measurement in term Nigerian neonates: establishing reference values. Int J Pediatr. 2018;2018:3624548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang B, Yuan Y, Sun L, Zhang L, Zhang Z, Fu L, et al. Optimal cutoff of the abdominal skinfold thickness (AST) to predict hypertension among Chinese children and adolescents. J Hum Hypertens. 2022;36(9):860–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tingley D, Yamamoto T, Hirose K, Keele L, Imai K. Mediation: R package for causal mediation analysis. J Stat Softw. 2014;59(5):1–38.26917999 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Joubert BR, Felix JF, Yousefi P, Bakulski KM, Just AC, Breton C, et al. DNA methylation in newborns and maternal smoking in pregnancy: genome-wide consortium meta-analysis. Am J Hum Genet. 2016;98(4):680–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lowe LP, Metzger BE, Dyer AR, Lowe J, McCance DR, Lappin TR, et al. Hyperglycemia and adverse pregnancy outcome (HAPO) study: associations of maternal A1C and glucose with pregnancy outcomes. Diabetes Care. 2012;35(3):574–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Group HSCR. Hyperglycemia and adverse pregnancy outcome (HAPO) study: associations with neonatal anthropometrics. Diabetes. 2009;58(2):453–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kale SD, Kulkarni SR, Lubree HG, Meenakumari K, Deshpande VU, Rege SS, et al. Characteristics of gestational diabetic mothers and their babies in an Indian diabetes clinic. J Assoc Physicians India. 2005;53:857–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Deierlein AL, Siega-Riz AM, Chantala K, Herring AH. The association between maternal glucose concentration and child BMI at age 3 years. Diabetes Care. 2011;34(2):480–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barak Y, Sadovsky Y, Shalom-Barak T. PPAR signaling in placental development and function. PPAR Res. 2008;2008:142082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Landgraf K, Kloting N, Gericke M, Maixner N, Guiu-Jurado E, Scholz M, et al. The obesity-susceptibility gene TMEM18 promotes adipogenesis through activation of PPARG. Cell Rep. 2020;33(3):108295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jamilian M, Samimi M, Mirhosseini N, Afshar Ebrahimi F, Aghadavod E, Taghizadeh M, et al. A randomized double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial investigating the effect of fish oil supplementation on gene expression related to insulin action, blood lipids, and inflammation in gestational diabetes mellitus-fish oil supplementation and gestational diabetes. Nutrients. 2018. 10.3390/nu10020163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wojcik M, Mac-Marcjanek K, Nadel I, Wozniak L, Cypryk K. Gestational diabetes mellitus is associated with increased leukocyte peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma expression. Arch Med Sci. 2015;11(4):779–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fisher JJ, Vanderpeet CL, Bartho LA, McKeating DR, Cuffe JSM, Holland OJ, et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction in placental trophoblast cells experiencing gestational diabetes mellitus. J Physiol. 2021;599(4):1291–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Latruffe N, Vamecq J. Peroxisome proliferators and peroxisome proliferator activated receptors (PPARs) as regulators of lipid metabolism. Biochimie. 1997;79(2–3):81–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Myatt L, Maloyan A. Obesity and placental function. Semin Reprod Med. 2016;34(1):42–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shekhawat P, Bennett MJ, Sadovsky Y, Nelson DM, Rakheja D, Strauss AW. Human placenta metabolizes fatty acids: implications for fetal fatty acid oxidation disorders and maternal liver diseases. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2003;284(6):E1098-1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Visiedo F, Bugatto F, Sanchez V, Cozar-Castellano I, Bartha JL, Perdomo G. High glucose levels reduce fatty acid oxidation and increase triglyceride accumulation in human placenta. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2013;305(2):E205-212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gauster M, Hiden U, van Poppel M, Frank S, Wadsack C, Hauguel-de Mouzon S, et al. Dysregulation of placental endothelial lipase in obese women with gestational diabetes mellitus. Diabetes. 2011;60(10):2457–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Radaelli T, Lepercq J, Varastehpour A, Basu S, Catalano PM, Hauguel-De Mouzon S. Differential regulation of genes for fetoplacental lipid pathways in pregnancy with gestational and type 1 diabetes mellitus. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;201(2):e201–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jiang S, Teague AM, Tryggestad JB, Jensen ME, Chernausek SD. Role of metformin in epigenetic regulation of placental mitochondrial biogenesis in maternal diabetes. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):8314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rosenfeld CS. Sex-specific placental responses in fetal development. Endocrinology. 2015;156(10):3422–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sebo P, Beer-Borst S, Haller DM, Bovier PA. Reliability of doctors’ anthropometric measurements to detect obesity. Prev Med. 2008;47(4):389–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data used for this study will be made available upon request.