Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the predictive value of maternal and umbilical cord blood triglyceride-glucose (TyG) index for adverse neonatal outcomes in pregnancies complicated by preeclampsia.

Study design

This prospective case-control study included 43 pregnant women diagnosed with preeclampsia and 45 normotensive controls. Maternal and umbilical cord blood samples were collected at the time of delivery to measure glucose and triglyceride levels. TyG index was calculated for both maternal and cord blood. Neonatal outcomes including Apgar scores, NICU admission, and composite neonatal morbidity were recorded. ROC analysis was performed to assess the predictive accuracy of TyG indices.

Results

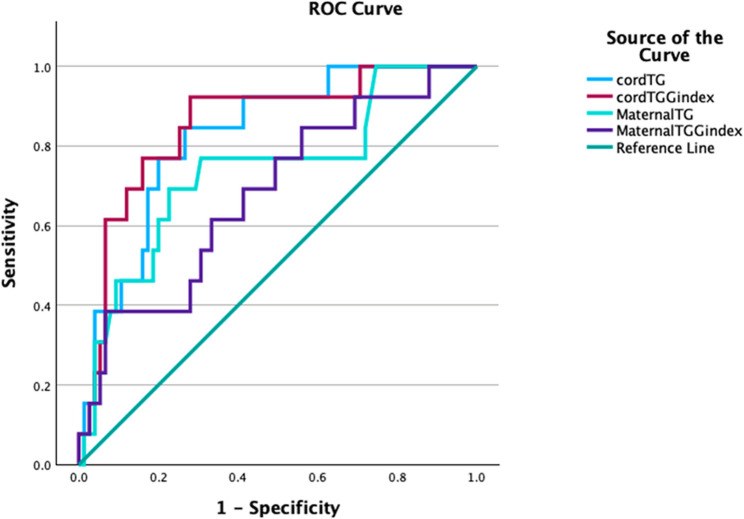

Maternal and cord blood TyG indices were significantly higher in the preeclampsia group compared to the control group (p < 0.001). ROC analysis revealed that a cord blood TyG index > 7.59 predicted composite adverse neonatal outcomes with 92% sensitivity and 72% specificity (AUC: 0.853, 95% CI: 0.74–0.96, p < 0.001). NICU admission rates and low Apgar scores were more frequent in the preeclampsia group, indicating a significant association between elevated TyG indices and adverse neonatal outcomes.

Conclusion

The TyG index, particularly when measured in umbilical cord blood, may serve as a useful predictor of adverse neonatal outcomes in pregnancies affected by preeclampsia. This easily accessible metabolic marker could support perinatal risk stratification and clinical decision-making.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12887-025-06185-4.

Keywords: Preeclampsia, TyG index, Umbilical cord blood, Neonatal outcome, NICU, Apgar score

Introduction

Preeclampsia is a complex systemic disorder characterized by new onset of hypertension and proteinuria or the new onset of hypertension plus significant end-organ dysfunction with or without proteinuria in a previously normotensive patient occurring after the 20th week of gestation [1, 2]. It is recognised as one of the leading causes of maternal and perinatal morbidity and mortality worldwide. The pathogenesis of preeclampsia likely involves both placental and maternal factors. Metabolic disorders such as insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, and endothelial dysfunction are believed to play a significant role in the development and progression of the disease [3–5]. Considering the effect of preeclampsia on the mechanisms regulating fetal growth and development, a better understanding of the pathophysiology of this disorder may enable the development of strategies for preventing fetal morbidity and mortality [6].

In recent years, there has been a growing focus on metabolic biomarkers that could serve as early indicators of adverse maternal and neonatal outcomes in preeclamptic pregnancies. The triglyceride-glucose (TyG) index is a reliable indirect marker of insulin resistance, easily calculated from fasting triglyceride and glucose levels [7]. The TyG index has attracted attention in recent years due to its association with cardiovascular risk, gestational diabetes, and hypertensive disorders in pregnancy [8, 9]. However, the predictive role of this index in preeclampsia, particularly regarding neonatal outcomes, has not yet been sufficiently investigated.

In this prospective observational study, we aimed to investigate the predictive value of the TyG index in maternal and umbilical cord blood on neonatal health in preeclamptic pregnancies. Our hypothesis was that high TyG indices, reflecting insulin resistance and metabolic stress, would be associated with adverse neonatal outcomes. This study aims to contribute to the literature by identifying metabolic markers that could be used in risk classification and early intervention in high-risk pregnancies.

Materials and methods

Study design

This study was designed as a prospective case-control study to investigate the role of the triglyceride/glucose index measured in umbilical cord and maternal blood in predicting neonatal adverse outcome. The study included pregnant women and newborns who presented to the Perinatology Unit of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology at Ankara Etlik City Hospital between 1 October 2024 and 1 May 2025. Maternal blood samples were collected during hospital admission in the third trimester, while fetal blood samples were collected during delivery. This study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Republic of Türkiye Ministry of Health, Ankara Etlik City Hospital (Ethics Committee Approval Number: AESH-BADEK-2024-829). All participants were informed about the purpose and procedures of the study and provided written informed consent prior to participation. Each participant gave their consent voluntarily and individually.

Selection of case, and selection of control

This prospective case-control study included a case group consisting of 43 patients diagnosed with preeclampsia and followed up at our clinic. To ensure homogeneity within the study population and reduce clinical variability, only cases of early onset preeclampsia, diagnosed before 34 weeks of gestation, and classified as mild in clinical presentation, were included in the preeclampsia group. The control group consisted of 45 healthy pregnant women who were examined on the same day and matched for gestational age. All participants were between 34 and 37 weeks of gestation in the third trimester.

Preeclampsia was diagnosed according to the criteria of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (ACOG) [10]. Preeclampsia was defined as blood pressure ≥ 140/90 mmHg along with proteinuria or organ dysfunction symptoms after the 20th week of pregnancy. Proteinuria was defined as a protein-creatinine ratio ≥ 0.3 in a spot urine sample or total protein ≥ 300 mg in a 24-hour urine sample. Criteria for organ dysfunction include a platelet count < 100,000/mm³, serum creatinine level ≥ 1.1 mg/dL or twice the baseline level, liver transaminase levels more than twice the upper reference value, new-onset pulmonary oedema, or severe headache and visual disturbances. Pregnant women with medical conditions such as acute or chronic inflammatory diseases, chronic kidney or liver disease, chronic hypertension, pregnancy or type 1–2 diabetes mellitus (DM), smoking, alcohol consumption or multiple pregnancies and preterm birth have been excluded from the study. Composite adverse perinatal outcomes (CAPO) include the presence of at least one of the following adverse outcomes: 5th-minute APGAR score < 7, transient tachypnea of the newborn (TTN), respiratory distress syndrome (RDS), need for continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), need for mechanical ventilation, neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) admission, neonatal hypoglycemia and need for phototherapy.

Sample collection and laboratory procedures

Maternal venous blood samples were obtained following a minimum of 8 h of overnight fasting, as per routine clinical protocol, to ensure standardization of glucose and triglyceride measurements used in the TyG index calculation. Umbilical cord blood samples were collected immediately after delivery but prior to placental separation, in accordance with standard clinical protocol. This approach was chosen to minimize metabolic alterations that may occur after placental detachment, thus ensuring the accuracy and consistency of the biochemical measurements, including the TyG index. Umbilical cord blood (10 ml) was centrifuged, and the resulting serum samples were transferred to Eppendorf tubes and stored at − 80 °C. The samples were analysed using serum samples obtained after centrifugation. Measurements were performed using a fully automated biochemical analysis device, the Cobas c702 (Roche Diagnostics, Germany). Glucose levels were measured using the hexokinase method, while triglyceride levels were measured using the enzymatic colorimetric method. Measurements were performed in accordance with the manufacturer’s recommended protocols and quality control standards. The values of maternal venous blood samples taken from the patient during hospitalization as part of routine clinical practice were included in the study Patient data were collected from medical records and the hospital’s information management system. Data on maternal age, gravidity, parity, pregestational BMI (kg/m2), gestational age at diagnosis (week), birth weight (g), 1 st and 5th minute Apgar scores and route of delivery were obtained from patients’ medical files and compared between the groups. Complete blood test and biochemical blood test were obtained for all patients in the study. TyG index calculation formula is as follows: TyG index = Ln [fasting triglyceride (mg/dl) × fasting glucose (mg/dl)/2] [11]. This is a composite indicator consisting of fasting triglyceride (TG) and fasting plasma glucose levels.

Statistical analysis

A power analysis was conducted using G*Power 3.1.9.7 software to evaluate the statistical power of the study. In the analysis, the effect size was set at moderate (d = 0.5), the significance level at 5% (α = 0.05), and the test Power at 95% (1-β = 0.95). Based on these parameters, the study aimed to achieve sufficient statistical Power. Statistical analysis was conducted using IBM Corporation SPSS version 22.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA). The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to analyze the conformity to normal distribution. Descriptive statistics for continuous variables were presented as “mean ± standard deviation” for those showing normal distribution and “median (interquartile range)” for those not showing normal distribution. Categorical variables were compared using the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test. Continuous variables were compared using the independent sample t-test and Mann-Whitney U test, depending on whether they showed a normal distribution. The Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve was applied to determine the optimal cutoff values according to the Youden index by calculating and comparing the areas under the curve (AUC). Statistical significance for all tests was defined as a P-value less than 0.05. In inter-individual correlation analyses, the Spearman rank correlation coefficient (Spearman’s rho) was used for pairs of variables with non-parametric distributions.

Results

This study included a total of 88 individuals, comprising 43 cases diagnosed with preeclampsia and 45 healthy controls. When comparing the demographic, clinical, and biochemical characteristics of the groups, no statistically significant differences were found in maternal age, gravida, primiparity rate, history of in vitro fertilisation, body mass index (BMI), weight gain during pregnancy, week of blood sample collection, smoking status, haemoglobin level, white blood cell count, platelet count, and fibrinogen levels were found to be statistically insignificant. However, serum creatinine levels were significantly higher in the preeclampsia group compared to the control group (p = 0.015). Additionally, albumin levels were significantly lower in the preeclampsia group (p < 0.001) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Comparison of maternal demographic, clinical, and laboratory characteristics between preeclampsia and control groups

| Preeclampsia n = 43 |

Control n = 45 |

p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal age (year) | 30.6 ± 6.3 | 28.7 ± 5.4 | 0.477a |

| Gravida | 2 (2) | 2 (3) | 0.932b |

| Primiparity | 1 (2) | 1 (2) | 0.979b |

| In vitro fertilization | 1 (2.3%) | 0 | 0.304c |

| BMI (kg/m 2 ) | 31.1 (7.1) | 30.6 (7.5) | 0.527b |

| Gestational weight gain (kg) | 10 (7) | 12 (5) | 0.112b |

| Gestational age at blood sampling (week) | 37 (3) | 37 (5) | 0.852b |

| Smoking | 2 (4.4%) | 0 | 0.162c |

| Hemoglobin (g/dl) | 11.5 (1.5) | 12.1 (1.6) | 0.242b |

| White blood cell count (10 9 /L) | 10 (3.9) | 10.5 (2.8) | 0.855b |

| Platelet count (10 9 /L) | 224 (59) | 231 (78) | 0.254b |

| Albumin (g/dl) | 34.1 (3.2) | 37.4 (2.9) | < 0.001 b |

| Creatinine (mg/dl) | 0.59 (0.2) | 0.52 (0.1) | 0.015 b |

| Fibrinogen (mg/dL) | 458 (109) | 477 (122) | 0.673b |

Data are expressed as mean ± SD or median (interquartile range) where appropriate

A p value of < 0.05 indicates a significant difference and statistically significant p-values are in bold

BMI Body mass index, SD Standard deviation

aStudent T-test, bMann Whitney-U test, cPearson chi-square

When metabolic parameters were evaluated, maternal triglyceride levels and maternal triglyceride/glucose index values were significantly higher in the preeclampsia group compared to the control group (p < 0.001 for both variables) (Table 2). Similarly, cord blood triglyceride levels and cord blood triglyceride/glucose index were also significantly higher in the preeclampsia group (p < 0.001 for both variables). However, no significant difference was observed between the groups in terms of maternal glucose and cord blood glucose levels (p = 0.977 and p = 0.260, respectively).

Table 2.

Comparison of maternal and umbilical cord blood biochemical parameters between preeclampsia and control groups

| Preeclampsia n = 43 |

Control n = 45 |

p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal Triglyceride (mg/dl) | 244 (100) | 189 (58) | < 0.001 |

| Maternal Glucose (mg/dl) | 76 (11) | 75 (12) | 0.977 |

| Maternal Triglyceride/Glucose index | 9.1 (0.3) | 8.8 (0.4) | < 0.001 |

| Cord Blood Triglyceride mg/dl) | 69.2 (22.3) | 33.2 (15.6) | < 0.001 |

| Cord Blood Glucose (mg/dl) | 68.7 (13.7) | 66.3 (16.2) | 0.260 |

| Cord Blood Triglyceride/Glucose index | 7.8 (0.4) | 7 (0.53) | < 0.001 |

Data are expressed as median (interquartile range). A p value of < 0.05 indicates a significant difference and statistically significant p-values are in bold

When neonatal outcomes were evaluated, there were no significant differences between the groups in terms of gestational age, birth weight, and caesarean section rates (p > 0.05). However, 1 st and 5th minute Apgar scores were significantly lower in the preeclampsia group compared to the control group (p < 0.001 for both variables). The rate of admission to the neonatal intensive care unit, the incidence of transient tachypnea, and adverse composite neonatal outcomes were significantly higher in the preeclampsia group (p = 0.003, p = 0.019, and p < 0.001, respectively) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Birth characteristics and neonatal outcomes of the newborns

| Preeclampsia n = 43 |

Control n = 45 |

p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gestational age at delivery (week) | 37 (1.3) | 37.4 (2) | 0.353b |

| Cesarean section | 17 (39.5%) | 15 (33.3%) | 0.545 c |

| Birth weight (gram) | 2925 ± 549 | 3139 ± 411 | 0.061a |

| Apgar score at 1 st minute | 7 (2) | 9 (1) | < 0.001 b |

| Apgar score at 5th minute | 9 (2) | 10 (2) | < 0.001 b |

| NICU admission | 10 (23.3%) | 1 (2.2%) | 0.003 c |

| Transient tachypnea of the newborn | 5 (11.6%) | 0 (0%) | 0.019 c |

| Neonatal sepsis | 1 (2.3%) | 0 (0%) | 0.306c |

| Fetal distress | 4 (9.3%) | 2 (4.4%) | 0.369c |

| Respiratory distress syndrome | 3 (7%) | 1 (2.2%) | 0.287c |

| Mechanical ventilation | 3 (7%) | 1 (2.2%) | 0.287c |

| Phototherapy for neonates | 2 (4.7%) | 0 (0%) | 0.146c |

| Neonatal hypoglycemia | 3 (7%) | 0 (0%) | 0.073c |

| Interventricular hemorrhage | 1 (2.3%) | 0 (0%) | 0.306c |

| Adverse composite neonatal outcomes | 12 (27.9%) | 1 (2.2%) | < 0.001 c |

Data are expressed as mean ± SD or median (interquartile range) where appropriate

A p value of < 0.05 indicates a significant difference and statistically significant p-values are in bold

NICU Neonatal intensive care unit. aStudent T-test, bMann Whitney-U test, cPearson chi-square test Adverse composite neonatal outcomes (CNO) included the presence of at least one of the following adverse outcomes: admission to the NICU, neonatal hypoglycemia, need for phototherapy, neonates with APGAR < 7 at 1 and 5 min, need for cesarean section due to fetal distress, mechanical ventilation, sepsis, respiratory distress syndrome (RDS), intra-ventricular hemorrhage (IVH)

In diagnostic performance analyses, when considering the area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve (AUC) values, the optimal threshold value for the cord blood triglyceride/glucose index was determined to be > 7. 59, with sensitivity of 92% and specificity of 72% (AUC: 0.853, 95% CI: 0.74–0.96; p < 0.001) (Fig. 1). Similarly, a threshold value of > 65.7 mg/dL for cord blood triglyceride levels demonstrated significant diagnostic accuracy with 76% sensitivity and 78% specificity (AUC: 0.826, p < 0.001). The optimal cut-off for maternal triglyceride levels was determined as > 233.5 mg/dL, with sensitivity of 72% and specificity of 69% at this threshold (AUC: 0.738, p < 0.001). The optimal threshold value for the maternal triglyceride/glucose index was found to be > 9.05, with a sensitivity of 62%, specificity of 61%, and diagnostic accuracy AUC = 0.679 (95% CI: 0.52–0.83, p < 0.001) (Table 4). Additionally, a moderate, positive, and statistically significant correlation was found between maternal triglyceride levels and cord blood triglyceride levels (Spearman’s rho = 0.384, p < 0.001, n = 88).

Fig. 1.

ROC curves of maternal and cord blood triglyceride and TyG indices for predicting adverse neonatal outcomes in preeclamptic pregnancies

Table 4.

ROC analysis of TyG index and triglyceride levels for neonatal risk prediction in preeclamptic pregnancies

| Cut-off* | Sensitivity | Specificity | AUC | %95 CI | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal Triglyceride (mg/dl) | > 233.5 | 72% | 69% | 0.738 | 0.58–0.89 | < 0.001 |

| Maternal Triglyceride/Glucose index | > 9.05 | 62% | 61% | 0.679 | 0.52–0.83 | < 0.001 |

| Cord Blood Triglyceride (mg/dl) | > 65.7 | 76% | 78% | 0.826 | 0.71–0.93 | < 0.001 |

| Cord Blood Triglyceride/Glucose index | > 7.59 | 92% | 72% | 0.853 | 0.74–0.96 | < 0.001 |

Cut-off values were determined using the Youden index. AUC: Area under the curve, CI: Confidence Interval. Statistically significant values are shown in bold

Discussion

In this study, we compared maternal and umbilical cord blood biochemical parameters and neonatal outcomes between preeclamptic and healthy pregnant women. Our findings indicate that triglyceride levels and the triglyceride/glucose index (TyG index) are significantly elevated in both maternal and cord blood in women diagnosed with preeclampsia. This result suggests that abnormalities in lipid and glucose metabolism may play a role in the pathophysiology of preeclampsia. Indeed, the literature reports an atherogenic dyslipidemia profile (high plasma triglyceride and low HDL-cholesterol levels) in preeclamptic pregnant women [12]. Studies have suggested that the excessive levels of physiological insulin resistance caused by hormones and cytokines secreted by the placenta, particularly progesterone, during pregnancy trigger sympathetic nervous system activation, thereby increasing vascular resistance and sodium retention. which in turn may contribute to the development of preeclampsia by causing endothelial dysfunction and hypertension [8, 13]. In their study, Zhang et al. evaluated the TyG index as a practical parameter for indirectly measuring insulin resistance and highlighted the prognostic value of this index in obstetrics [8]. In a study conducted by Song et al., it was demonstrated that women with high TyG indices in the first trimester had a significantly increased risk of developing preeclampsia [14]. Similarly, in a prospective cohort study conducted by Gurzo et al., it was reported that women with a TyG index > 8.6 in the first trimester of pregnancy had approximately twice the risk of developing preeclampsia compared to those with lower TyG values [15]. In our study, consistent with the literature, maternal and fetal TyG indices were found to be significantly higher in the preeclampsia group. Considering that the TyG index is an easy and routinely measurable value, it can be used as a useful screening tool for the early identification of pregnant women at risk of preeclampsia and for follow-up in this direction.

Additionally, it is thought that lipid metabolism disorders and insulin resistance accompanying preeclampsia may also affect fetal circulation. Indeed, Stadler et al. reported significant changes in lipid profiles and HDL function in newborns born to preeclamptic mothers in their study [12]. The literature also reports that babies born to mothers with preeclampsia are at higher risk of preterm birth, lower birth weight, Apgar score, and complications such as neonatal intensive care and respiratory distress syndrome compared to babies born from healthy pregnancies [16]. In our study, consistent with the literature, 23.3% of newborns in the preeclampsia group required admission to the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) and had significantly lower Apgar scores at 1 and 5 min (p < 0.001), clearly demonstrating the adverse effects of maternal preeclampsia on neonatal morbidity. In their study, Kavurt et al. reported that the TyG index and triglyceride/HDL ratio in cord blood were positively correlated with the HOMA-IR (insulin resistance) value in newborns [17]. These findings support the notion that exposure to a hyperglycemic and hypertriglyceridemic environment during the intrauterine period affects the infant’s metabolic profile and is reflected in parameters measured at birth. In our study, we observed that a similar principle may apply in the context of preeclampsia. Although preeclampsia is frequently associated with low birth weight and placental insufficiency, the metabolic adaptation of the fetus may also be affected, particularly in cases of preeclampsia accompanied by maternal insulin resistance and lipid metabolism disorders. The elevated TyG values we measured in the cord blood may serve as an indicator that the fetus was affected by this metabolic stress environment in utero.

In our study, unlike other studies in the literature, the metabolic status of both maternal and cord blood was evaluated in pregnant women diagnosed with preeclampsia and correlated with neonatal outcomes. Triglyceride levels and TyG index in fetal umbilical cord blood were found to be significantly higher in the preeclampsia group compared to the control group (p < 0.001). The 7.59 TyG cut-off value we identified may be the first threshold defined in the literature and offers clinical applicability potential with a balance of 92% sensitivity and 72% specificity (AUC: 0.853; 95% CI: 0.74–0.96; p < 0.001). Newborns with umbilical cord blood TyG values above this threshold may be considered to constitute a higher-risk group. Further studies in different cohorts to validate this threshold value could pave the way for the TyG index to be incorporated as a prognostic biomarker in standard care. This finding suggests that the cord TyG index may not only reflect fetal metabolic status but also serve as a usable biomarker for predicting neonatal prognosis.

Based on the findings, the TyG index could serve as an easy screening tool in pregnancy monitoring due to its ease of calculation. In addition to specific biomarkers such as sFlt-1/PlGF used in preeclampsia prediction, the TyG index, as a metabolic indicator, could offer a highly applicable, low-cost alternative even within a broader healthcare system [18]. Close monitoring of cases with high TyG values in early pregnancy and, when necessary, interventions such as diet and exercise to reduce insulin resistance may theoretically improve pregnancy outcomes [19]. In preeclampsia, an increase in maternal TyG values in later weeks may be considered a sign of an increased risk of neonatal complications. In such cases, preeclamptic pregnancies with high TyG values may be managed in tertiary care centres with access to neonatal intensive care units.

Given its accessibility and low cost, the cord blood TyG index may be a useful tool in neonatal risk stratification, especially in pregnancies complicated by preeclampsia. Pregnancies identified with elevated fetal TyG values at delivery could prompt closer postnatal monitoring. Furthermore, recognizing elevated TyG levels may help guide decisions regarding the need for intensified maternal metabolic management. Integration of such biomarkers into clinical workflows could enhance personalized care strategies, particularly in tertiary centers dealing with high-risk pregnancies.

Although angiogenic biomarkers such as the sFlt-1/PlGF ratio have been widely validated and incorporated into clinical practice for the prediction and diagnosis of preeclampsia, they often require specialized laboratory equipment and may not be readily accessible in all healthcare settings. In contrast, the TyG index is derived from routine laboratory parameters that are inexpensive, widely available, and easy to interpret. These features make the TyG index an attractive and practical alternative, especially in low-resource environments. While our study did not include a direct comparison between TyG and angiogenic markers, the promising performance of the TyG index in predicting adverse neonatal outcomes warrants further investigation, ideally in studies that directly compare multiple biomarkers in a prospective manner. An important advantage of our study is that we evaluated cord blood samples. Cord blood accurately reflects the metabolic environment to which the fetus is exposed during the intrauterine period, and by using cord blood in our study, we have contributed to an area that has been limited in the literature. In addition, the neonatal outcomes examined are objective and clinically significant criteria. As a result, the prognostic value of the TyG index has been evaluated based on concrete clinical outcomes. In our study, an optimal cut-off value was determined using ROC analysis. This statistical approach clarifies the increase in risk when the TyG index exceeds a certain threshold and provides a valuable reference point for future studies and clinical practice. The fact that our study was conducted at a single centre and included a relatively limited number of cases is a factor that limits the generalisability of our results. One limitation of our study is that maternal and fetal TyG indices were measured only at the time of delivery. While this approach allowed us to directly correlate TyG levels with immediate neonatal outcomes, it limits the potential for early prediction or intervention during pregnancy. Measuring the TyG index at earlier stages, such as in the second trimester, might provide a valuable opportunity to identify at-risk pregnancies and implement timely clinical strategies. Future prospective studies should investigate the predictive capacity of the TyG index across different gestational periods to determine the optimal timing for its use in perinatal care. Although the sample size used in our study was statistically adequate based on the a priori Power analysis, it remains relatively limited for a case-control design. This constrained our ability to perform detailed subgroup analyses and may have reduced the statistical Power to detect less common neonatal outcomes. While our findings demonstrated significant associations within the current cohort, future multicenter studies with larger and more diverse populations are needed to enhance generalizability and to evaluate smaller effect sizes more reliably. For these reasons, the results need to be supported by prospective studies conducted in larger populations and at different time points. The proposed cut-off value of 7.59 represents a preliminary threshold derived from our specific study population. Future research involving larger, multicenter cohorts will be valuable to further assess the reproducibility and clinical applicability of this threshold in predicting adverse neonatal outcomes in preeclamptic pregnancies.

In conclusion, the TyG index, a marker of maternal and fetal metabolic status in pregnant women with preeclampsia, has emerged as a valuable parameter for predicting the clinical outcome of the newborn, especially when measured in cord blood.

Conclusion

This study demonstrated that the maternal and fetal triglyceride/glucose index in pregnant women diagnosed with preeclampsia may serve as an important biomarker for predicting neonatal outcomes. In particular, the cord blood TyG index, with a cut-off value of > 7.59, demonstrated high sensitivity and specificity in predicting adverse neonatal outcomes, highlighting the clinical potential of this parameter. It is believed that metabolic disorders in preeclampsia may affect not only maternal health but also fetal metabolism and neonatal prognosis. In this context, accessible and low-cost biomarkers such as the TyG index have been shown to serve as complementary tools in the early diagnosis and management of high-risk pregnancies.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the staff of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at Ankara Etlik City Hospital for their assistance in data collection and patient coordination.

Abbreviations

- ACOG

American college of obstetricians and gynecologists

- AUC

Area under the curve

- BMI

Body mass index

- CAPO

Composite adverse perinatal outcomes

- CPAP

Continuous positive airway pressure

- DM

Diabetes mellitus

- GDM

Gestational diabetes mellitus

- HDL

High density lipoprotein

- NICU

Neonatal intensive care unit

- PE

Preeclampsia

- RDS

Respiratory distress syndrome

- ROC

Receiver operating characteristic

- TG

Triglyceride

- TTN

Transient tachypnea of the newborn

- TyG index

Triglyceride/glucose index

Authors’ contributions

Design: DDB, SK, MB, ZVYPlanning: DDB, RD, MB, ZVYData Acquisition: DDB, MAÖ, ZŞ, GK, EBS, ZVYData analysis: DDB, EBS, SK, ZŞ Manuscript writing: DDB, RD, MAÖ, ZŞ, GK, ZVYFinal Approval: GK, ZVY.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for this article’s research, authorship, and publication.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was conducted in accordance with the principles stated in the Declaration of Helsinki and ethical approval was obtained from Ankara Etlik City Hospital Ethics Committee (approval number: AESH-BADEK-2024-829). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to their inclusion in the study.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent for publication of anonymized data was obtained from all participants prior to inclusion in the study.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Sotiriadis A, Hernandez-Andrade E, da Silva Costa F, Ghi T, Glanc P, Khalil A et al. ISUOG Practice Guidelines: role of ultrasound in screening for and follow-up of pre-eclampsia. Ultrasound in Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2019;53(1):7–22. Available from: 10.1002/uog.20105. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/ [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Gestational Hypertension and Preeclampsia. ACOG practice bulletin, number 222. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;135(6):e237–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Powe CE, Levine RJ, Karumanchi SA. Preeclampsia, a disease of the maternal endothelium: the role of antiangiogenic factors and implications for later cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 2011;123(24):2856–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wolf M, Sandler L, Munoz K, Hsu K, Ecker J, Thadhani R. First trimester insulin resistance and subsequent preeclampsia: a prospective study. J Clin Endocrinol Metabolism [Internet]. 2002;87 4:1563–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.LaMarca B. Endothelial dysfunction; an important mediator in the Pathophysiology of Hypertension during Preeclampsia. Minerva Ginecol. 2012 ;64(4):309–20. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3796355/ [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Backes CH, Markham K, Moorehead P, Cordero L, Nankervis CA, Giannone PJ. Maternal Preeclampsia and Neonatal Outcomes. J Pregnancy. 2011 ;2011:214365. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3087144/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Kim JA, Kim J, Roh E, Hong S, hyeon, Lee YB, Baik SH et al. Triglyceride and glucose index and the risk of gestational diabetes mellitus: a nationwide population-based cohort study. Diabetes research and clinical practice. 2020. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Zhang J, Yin B, Xi Y, Bai Y. Triglyceride-glucose index: A promising biomarker for predicting risks of adverse pregnancy outcomes in hangzhou, China. Prev Med Rep. 2024;41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Zhang J, Fang X, Song Z, Guo X, ke, Lin D, mei, Jiang F et al. na,. Positive association of triglyceride glucose index and gestational diabetes mellitus: a retrospective cohort study. Frontiers in Endocrinology. 2025;15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 202: gestational hypertension and preeclampsia. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133(1):1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ramdas Nayak VK, Satheesh P, Shenoy MT, Kalra S. Triglyceride glucose (TyG) index: A surrogate biomarker of insulin resistance. J Pak Med Assoc. 2022;72(5):986–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stadler JT, Scharnagl H, Wadsack C, Marsche G. Preeclampsia Affects Lipid Metabolism and HDL Function in Mothers and Their Offspring. Antioxidants. 2023;12(4):795. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2076-3921/12/4/795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Vejrazkova D, Vcelak J, Vankova M, Lukasova P, Bradnova O, Halkova T, et al. Steroids and insulin resistance in pregnancy. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2014;139:122–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Song S, Luo Q, Zhong X, Huang M, Zhu J. An elevated triglyceride-glucose index in the first-trimester predicts adverse pregnancy outcomes: a retrospective cohort study. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2025;311(3):915–27. Available from: 10.1007/s00404-025-07973-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Gurza G, Martínez-Cruz N, Lizano-Jubert I, Arce-Sánchez L, Suárez-Rico BV, Estrada-Gutierrez G et al. Association of the Triglyceride–Glucose Index During the First Trimester of Pregnancy with Adverse Perinatal Outcomes. Diagnostics. 202;15(9):1129. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2075-4418/15/9/1129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Socol FG, Bernad E, Craina M, Abu-Awwad SA, Bernad BC, Socol ID et al. Health Impacts of Pre-eclampsia: A Comprehensive Analysis of Maternal and Neonatal Outcomes. Medicina. 2024;60(9):1486. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/1648-9144/60/9/1486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Kavurt S, Uzlu SE, Bas AY, Tosun M, Çelen Ş, Üstün YE, et al. Can the triglyceride-glucose index predict insulin resistance in LGA newborns? J Perinatol. 2023;43(9):1119–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kluivers ACM, Neuman RI, Saleh L, Russcher H, Brussé IA, Cornette JMJ, et al. PRERISK study: A randomized controlled trial evaluating a sFlt-1/PlGF-Based calculator for preeclampsia hospitalization. Hypertension. 2025;82(5):827–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Venkatasamy VV, Pericherla S, Manthuruthil S, Mishra S, Hanno R. Effect of Physical activity on Insulin Resistance, Inflammation and Oxidative Stress in Diabetes Mellitus. J Clin Diagn Res. 2013;7(8):1764–6. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3782965/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.