Abstract

An oligonucleotide-based microarray analysis of 9,500 genes and expressed sequence tags (ESTs) demonstrated that the type 1 inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor (IP3R) was significantly down-regulated in Bcl-XL-expressing as compared with control cells. This result was confirmed at the mRNA and protein levels by Northern and Western blot analyses of two independent hematopoietic cell lines and murine primary T cells. Bcl-XL expression resulted in a dose-dependent decrease in IP3R protein. IP3R expression is regulated as part of a mitochondrion-to-nucleus stress-responsive pathway. The uncoupling of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation resulted in induction of binding of the transcription factor NFATc2 to the IP3R promoter and transcriptional activation of IP3R. Expression of Bcl-XL led to a decreased induction of both NFATc2 DNA binding to the IP3R promoter and IP3R expression in response to the inhibition of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation. The Bcl-XL-dependent decrease in IP3R expression also correlated with a reduced T cell antigen receptor ligation-induced Ca2+ flux in Bcl-XL transgenic murine T cells, and microsomal vesicles prepared from Bcl-XL-overexpressing cells exhibited lower IP3-mediated Ca2+ release capacity. Furthermore, reintroducing IP3R into Bcl-XL-transfected cells partially reversed Bcl-XL-dependent anti-apoptotic activity. These results suggest that even under non-apoptotic conditions, expression of Bcl-2-family proteins influences a signaling network that links changes in mitochondrial metabolism to alterations in nuclear gene expression.

Proteins of the Bcl-2 family play critical roles in the regulation of programmed cell death (1–3). In response to stimuli such as growth factor withdrawal, loss of cellular attachment, or DNA damage, cells from multicellular organisms can initiate their own death through apoptosis. Under such conditions, the expression of anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family members, including Bcl-2 and Bcl-XL, can prevent the initiation of an apoptotic response and maintain the survival and/or promote the recovery of the cell. In contrast, overexpression of pro-apoptotic family members such as Bax and Bak promotes the initiation of apoptosis in response to cytotoxic insults. These results have demonstrated that Bcl-2 proteins function to regulate the apoptotic response. However, it is less clear whether Bcl-2 proteins play roles in regulating cellular physiology under non-apoptotic conditions.

Bcl-2 and Bcl-XL are constitutively expressed and are localized to the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), perinuclear, and outer mitochondrial membranes. On the basis of their localization, Bcl-2 and Bcl-XL have been hypothesized to regulate mitochondrial physiology and/or Ca2+ metabolism (4, 5). Alternatively, these anti-apoptotic proteins may function primarily to oppose the pro-apoptotic functions of two other family members required for the initiation of programmed cell death, Bax and Bak (1–3). Both Bax and Bak exist in an inactive conformation in healthy cells, and they undergo conformational changes in response to apoptotic stimuli (6–8). These conformational changes then enable their participation in events that result in apoptosis.

To address whether the anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-XL influences cellular physiology in the absence of apoptotic stimuli, we have carried out an oligonucleotide-based microarray analysis of 9,500 murine genes and expressed sequence tags (ESTs) to identify global changes in gene expression in response to Bcl-XL expression. Highly reproducible changes in the expression of several genes involved in the metabolism of calcium and other divalent cations were identified. The most dramatic change was observed for the type 1 inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3) receptor (IP3R), an intracellular Ca2+ channel gated by the secondary messenger IP3. IP3R is responsible for the mobilization of Ca2+ from intracellular stores in response to signals from receptors on the plasma membrane (9, 10). One response to the release of Ca2+ through IP3R is enhanced coupling of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation rate to increased cellular demand as a consequence of activation of a signal transduction cascade (5, 11). We observed a dose-dependent reduction of IP3R protein in cells that overexpress Bcl-XL, which further correlated with a reduction in receptor-induced Ca2+ flux and with a reduced ability to release Ca2+ upon IP3 treatment of ER vesicles. Also, reduction of mitochondrial membrane potential increased the binding of the transcription factor NFATc2 to the IP3R promoter and IP3R expression. This effect was compromised by Bcl-XL overexpression. These data provide new insights into how intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis is affected by Bcl-XL expression. This study suggests that overexpression of Bcl-XL leads to a reduction in IP3R levels, through down-regulation of a mitochondrion-to-nucleus stress signaling pathway. Transient transfection of IP3R was able to partially reverse Bcl-XL-mediated resistance to apoptosis.

Materials and Methods

Cell Lines, Mice, and Reagents.

The FL5.12 murine pro-B cell line, the 2B4.11 murine T cell hybridoma line, and pLck-Bcl-XL transgenic mice were described (12). Pharmacological agents were myo-inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate, phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA), and ionomycin (Sigma), and Indo-1 acetoxymethyl ester and propidium iodide (Molecular Probes). Antibodies were anti-CD3 (145-2C11) (PharMingen), type 1 IP3R-specific polyclonal antibody (pAb; the kind gift of Darren Boehning and Suresh K. Joseph), type 3 IP3R-specific mAb (Transduction Laboratories, Lexington, KY), pAbs against sarcoplasmic reticulum/ER Ca2+ ATPase 2 (SERCA2) and actin and mAb against NFATc2 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), pAb against calreticulin (StressGen Biotechnologies, Victoria, Canada), goat anti-hamster pAb (Pierce), and pAb against Bcl-XL (12).

Northern and Western Blots.

Total RNA from the indicated cell lines was purified by using Trizol (Life Technologies). RNA (10 μg) was resolved on formaldehyde/agarose gel and Northern blotting was performed as described (12). Whole cell extracts were prepared in RIPA buffer (0.15 M NaCl/10 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 7.2/1% Nonidet P-40/1% sodium deoxycholate/0.1% SDS) with protease inhibitors, and protein concentrations were determined by BCA protein assay (Pierce). Western blotting was performed as described (12).

Complementary RNA (cRNA) Hybridization to Oligonucleotide Microarrays and Data Analysis.

Total RNA from FL5.12 cell lines was prepared by the cesium chloride method. cRNA preparation and sequential hybridization to Affymetrix Test 2, and murine 11K sub A and sub B microarrays were performed according to the manufacturer's recommendations. The intensities of individual probe cells were determined by using GENECHIP 3.3 software (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA). Background subtraction, probe cell scaling (to normalize between arrays), and calculation of gene expression values and pairwise fold changes were performed in a manner similar to that recommended by the manufacturer. All microarray experiments were performed in triplicate.

Measurement of Primary T Cell [Ca2+]i.

Murine splenic T cells were purified as described (12). The purified T cells were resuspended in RPMI medium 1640 with 1% fetal bovine serum and loaded with 2 μM Indo-1 in the presence of either 5 or 10 μg/ml anti-CD3 Abs at 30°C for 30 min. Loaded cells were washed and resuspended in RPMI 1640. The measurement of cytosolic free Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) was performed on an LSR flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson). Briefly, after stable basal [Ca2+]i was achieved, cross-linking goat anti-hamster Ab (5 μg/ml) was added to cells, and 10 min later, 1 μg of ionomycin was added. Data analysis was performed by using FlowJo software (Tree Star, San Carlos, CA), and [Ca2+]i was calculated from the equation [Ca2+]i = K⋅(R − Rmin)/(Rmax − R), where the values of Rmin and Rmax were determined from in situ calibration.

Microsomal Vesicle Preparation and Ca2+ Uptake and Release Measurement.

Microsomal vesicles and the reaction buffer were prepared as described (13), with some modification. Free Ca2+ in the reaction buffer was calibrated to the indicated concentrations by using the Ca2+ indicator calcium green–1 and a calcium calibration kit (Molecular Probes) on a FluoroMax-2 spectrofluorimeter (Instruments S.A., Edison, NJ). Experiments were carried out at 30°C with 1 μM carbonyl cyanide p-(trifluoromethoxy)phenylhydrazone (FCCP) and 3 μCi/ml 45Ca2+ (NEN Life Science; 1 μCi = 37 kBq) in the buffer, and three aliquots containing 5 μg of microsomal vesicles were taken out at the indicated time points.

Gel Mobility-Shift Assays.

Nuclear extracts were prepared as described (14), with minor modifications. Binding reactions and electrophoretic mobility-shift assays were performed as described (14). Gel mobility-shift probes included: the murine IP3R1 NFAT binding site 2, 5′-GACACCCGGGGAAAGTTTGTGGAATGAATACGT (14), and Oct-1 consensus binding sequence, 5′-TGTCGAATGCAAATCACTAGAA (Santa Cruz Biotechnology).

Transient Transfection Death Assays.

The assays were performed as described (15). The reporter β-galactosidase (β-gal) activity was measured by using a Galacto-Light Plus kit (Tropix, Bedford, MA) on a TR717 luminometer (Tropix). Percentage of cytotoxicity was calculated with the equation: cytotoxicity (%) = 100 − (100⋅experimental β-gal/control β-gal).

Results

Type 1 IP3R mRNA Is Decreased in Bcl-XL-Expressing Cells.

Previous experiments have shown that the expression of Bcl-XL in FL5.12, an interleukin-3 (IL-3)-dependent lymphoid cell line, can confer resistance to a variety of death stimuli (12). Bcl-XL-transfected FL5.12 cells maintain equivalent viability, cell size, mitochondrial mass, growth rate, and cell cycle time as parental or vector-transfected cells when continuously grown in IL-3-containing medium (refs. 12 and 16; data not shown). Total RNA was purified from FL5.12 cells stably transfected with either a Bcl-XL-expressing plasmid or the vector control (12) 24 hr after passage into fresh IL-3-containing medium. The Bcl-XL-expressing cell line used in these analyses was chosen because Bcl-XL protein levels in this cell line were comparable to those found in mitogen-activated T cells (data not shown). Isolated RNA was then hybridized to Affymetrix murine 11K oligonucleotide microarrays representing 9,500 genes and expressed sequence tags (ESTs). Data from three independent experiments were averaged, and pairwise analysis was used to identify differentially expressed genes. The expression of 17 genes was increased significantly in Bcl-XL-overexpressing cells (Xl-4.1) versus control cells (Neo-5.3), whereas we identified 59 genes whose expression was lower in Xl-4.1 versus Neo-5.3 cells. The 10 genes whose expression differed most markedly in Bcl-XL-overexpressing versus control cells are presented in Table 1. Bcl-XL displayed the greatest increase in Xl-4.1 cells, confirming that transfection had resulted in a significant increase in Bcl-XL expression. The type 1 IP3R gene, Itpr1, was the top-ranked gene whose mRNA was decreased in Bcl-XL-overexpressing as compared with control cells. In addition to type 1 IP3R, two other subtypes of IP3R (types 2 and 3) encoded by distinct genes have been identified in mammalian cells (9, 10). The type 2 IP3R is expressed at a low level in FL5.12 cells (data not shown), whereas type 3 IP3R expression was not detectable by microarray analyses.

Table 1.

The top five increased and the top five decreased genes in Bcl-XL as compared with control FL5.12 cells

| Rank | Bcl-XL > Neo

|

Bcl-XL < Neo

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene | GenBank accession no. | Fold increase | Gene | GenBank accession no. | Fold decrease | |

| 1 | Bcl-XL | U10102 | 5.7 | IP3R1 (Itpr1) | X15373 | 4.6 |

| 2 | Calgranulin B (S100a9) | M83219 | 3.6 | Kidney-derived protease-like protein (Kdap) | AA108747 | 4.4 |

| 3 | X-linked lymphocyte-regulated 4 (Xlr4) | AA190046 | 2.4 | c-Myb | M13990 | 3.1 |

| 4 | Hemoglobin α, chain 1 (Hbaa1) | C79755 | 2.0 | Malic enzyme, supernatant (Mod1) | AA189662 | 2.6 |

| 5 | Growth factor receptor bound protein 7 (Grb7) | AA216863 | 1.8 | Selinium-binding protein 1 (Selenbp1) | M320325 | 2.5 |

RNA hybridization to oligonucleotide microarrays and data analysis were performed as described in Materials and Methods.

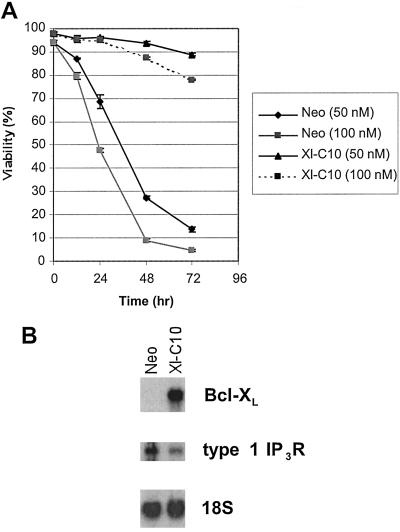

We next determined whether overexpressing Bcl-XL could also similarly affect IP3R expression in another cell line. Two stably transfected 2B4.11 T cell hybridoma lines were examined, the empty vector control (Neo) and the Bcl-XL-expressing line (Xl-C10) (12). As reported in other systems (17, 18), Bcl-XL expression protected 2B4.11 cells from apoptosis induced by treatment with the SERCA inhibitor thapsigargin. As shown in Fig. 1A, the majority of Bcl-XL-expressing cells remained viable after 48 hr in the presence of either 50 or 100 nM thapsigargin, whereas most control cells were dead at this time. Northern blot analysis revealed that the Bcl-XL-transfected 2B4.11 cells expressed significantly less type 1 IP3R than did the vector-transfected 2B4.11 cells (Fig. 1B).

Figure 1.

Bcl-XL-expressing 2B4.11 cells survive in the presence of thapsigargin and have reduced type 1 IP3R mRNA. (A) Survival was measured by propidium iodide exclusion with either 50 nM or 100 nM thapsigargin in the cell cultures at the indicated time points. Means and standard deviations of triplicate measurements are shown. (B) Northern blots of total RNA purified from 2B4.11 Neo and Xl-C10 cells. The filter was hybridized with probes for Bcl-XL, type 1 IP3R, and 18S rRNA, respectively.

IP3R Proteins Are Reduced in Bcl-XL-Expressing Cells.

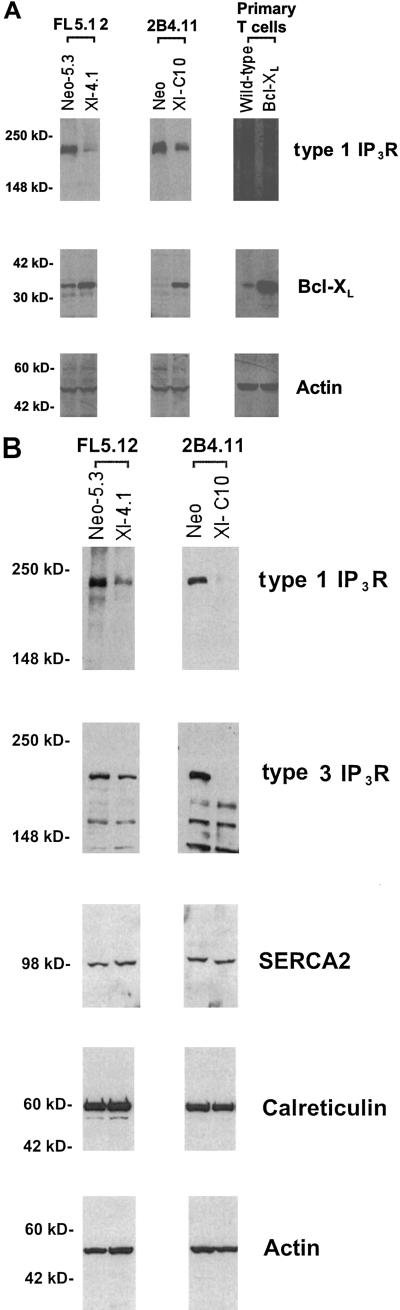

To confirm the Northern data, the link between Bcl-XL and IP3R expression was investigated by Western blot analyses. As shown in Fig. 2A, FL5.12, 2B4.11, and primary T cells that overexpressed Bcl-XL had significantly lower levels of type 1 IP3R protein as compared with controls. Anti-Bcl-XL and actin Western blots confirmed the levels of Bcl-XL and total protein in these samples (Fig. 2A). Type 2 IP3R protein could not be detected in either FL5.12 or 2B4.11 cells by Western blotting. However, as shown in Fig. 2B, the expression of type 3 IP3R was also reduced in Bcl-XL-overexpressing 2B4.11 and FL5.12 cells. In contrast, the expression of SERCA2, the major pump responsible for the transfer of Ca2+ from the cytosol to the ER, was unaffected by Bcl-XL expression (Fig. 2B). Bcl-XL overexpression also did not affect the expression of calreticulin, a Ca2+-binding protein in the ER lumen, or total intracellular Ca2+ (Fig. 2B and data not shown).

Figure 2.

IP3R proteins are down-regulated in cells expressing Bcl-XL. (A) Western blots of cell extracts made from the indicated cells. Filters were prepared as described in Materials and Methods and probed with antibodies against type 1 IP3R, Bcl-XL, and actin, respectively. The numbers at left indicate the molecular markers. (B) Immunoblot analysis of whole cell extracts from the cells indicated on the top. The filters were probed with the antibodies indicated on the right. The positions of molecular mass markers are indicated on the left.

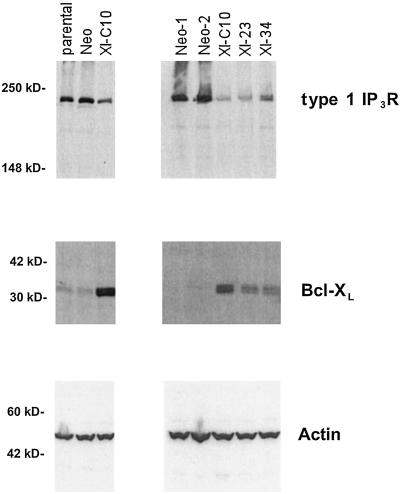

Thus, expression of Bcl-XL reduces the expression of at least two subtypes of IP3R. We next assessed whether Bcl-XL could affect IP3R expression in a dose-dependent manner. To this purpose, additional 2B4.11 cell lines expressing various amounts of Bcl-XL were made. As shown in Fig. 3, type 1 IP3R was expressed at similar levels in the parental and three Neo cell lines tested. All three Bcl-XL-expressing cell lines had considerably less type 1 IP3R compared with the parental and Neo cell lines. Among three Bcl-XL-expressing cell lines examined, the amounts of type 1 IP3R were inversely correlated with the levels of Bcl-XL. Parallel experiments using a Bcl-2 expression plasmid demonstrated that stable Bcl-2 expression also led to a comparable reduction in IP3R expression (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Bcl-XL regulates type 1 IP3R expression in a dose-dependent manner. Cell extracts from the indicated 2B4.11 cells were prepared, and the expression of type 1 IP3R was analyzed by Western blotting. Positions of molecular mass markers are shown on the left.

Expression of Bcl-XL Leads to Reduced Induction of NFAT DNA-Binding Activity and Type 1 IP3R Expression in Response to the Impairment of Mitochondrial Oxidative Phosphorylation.

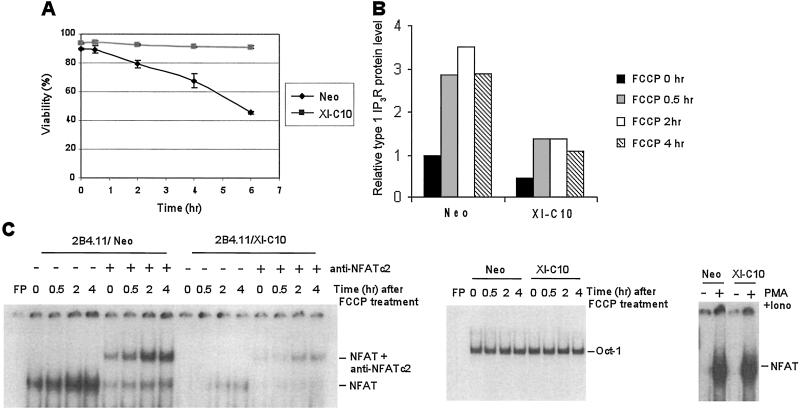

Previous studies in muscle cells have demonstrated that the inhibition of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation results in the increased expression of the myoblast counterpart of IP3R, the ryanodine receptor-1, because of activation of a mitochondrial-to-nuclear stress signaling pathway (19, 20). Bcl-XL has been reported to maintain outer mitochondrial membrane integrity by promoting the efficient coupling of electron transport to cytosolic substrates and ADP levels (16, 21). To determine whether Bcl-XL expression affects the mitochondrial-to-nuclear stress signaling pathway, we next tested IP3R expression after treatment with carbonyl cyanide p-(trifluoromethoxy)phenylhydrazone (FCCP), a potent uncoupler of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation. As shown in Fig. 4A, 2B4.11 Neo cells gradually died in the presence of 20 μM FCCP, whereas Xl-C10 cells remained viable, although FCCP depolarized the mitochondria and reduced the mitochondrial membrane potential of both Neo and Xl-C10 cells to a similar degree (data not shown). Thirty minutes after FCCP treatment, type 1 IP3R expression was significantly enhanced in both Neo and Xl-C10 cells (Fig. 4B). As in untreated cells, the level of type 1 IP3R protein in Neo cells was nearly 3 times that in Xl-C10 cells in the presence of FCCP.

Figure 4.

Increased NFATc2 binding to type 1 IP3R promoter and type 1 IP3R expression in response to inhibition of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation is compromised by Bcl-XL expression. (A) The viability of 2B4.11 Neo and Xl-C10 cells in the presence of 20 μM FCCP was measured over time by the propidium iodide exclusion method. Means and standard deviations of triplicates are shown. (B) Whole cell extracts were prepared from the indicated 2B4.11 cells treated with FCCP. The amounts of type 1 IP3R and actin on Western blot films were determined as described in Materials and Methods. The relative type 1 IP3R protein level is the amount of IP3R protein normalized to the amount of actin protein. (C) The indicated 2B4.11 cells were treated with FCCP and nuclear extracts were prepared. Gel-shift assays were performed by using end-labeled murine type 1 IP3R NFAT binding site 2 or Oct-1 binding site. Gel-shift experiments with Oct-1 were used to normalize the quantity and quality of nuclear extracts. FP, free probe; Iono, ionomycin.

Transcriptional activation of IP3R has been reported to be dependent on activation of NFAT family of transcription factors (14, 22). To determine whether changes in mitochondrial potential correlated with changes in NFAT DNA-binding activity, we examined NFAT protein levels in 2B4.11 Neo and Xl-C10 cells. The two cell lines had comparable total NFAT protein (data not shown). However, when nuclear extracts were made, less constitutive NFAT-dependent DNA binding to the type 1 IP3R promoter was detected in the nuclear extract of Bcl-XL-expressing cells as compared with control cells (Fig. 4C). Furthermore, mitochondrial uncoupling led to a potent induction of NFATc2 DNA-binding activity, but not NFATc1 and NFATc3, two other NFAT family members found in lymphocytes as demonstrated by gel-shift assays (Fig. 4C and data not shown). The level of NFAT induction was suppressed in Bcl-XL-expressing cells. However, Bcl-XL expression did not suppress the level of NFAT DNA-binding activity induced by treatment with phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate and the calcium ionophore ionomycin.

T Cell Receptor (TCR)-Mediated Ca2+ Flux Is Reduced in Bcl-XL Transgenic Primary T Cells.

The mobilization of IP3-sensitive Ca2+ stores through IP3R plays a central role in TCR-mediated T cell activation (23, 24). Therefore, we next determined whether reduced IP3R expression in Bcl-XL-expressing transgenic T cells (Fig. 2A) had a functional impact on the mobilization of ER Ca2+ after TCR cross-linking. Ca2+ flux assays were performed on live cells by using flow cytometry. The elevation of [Ca2+]i induced by CD3 ligation was measured in purified splenic T cells from both wild-type and Bcl-XL-transgenic mice. In both wild-type and Bcl-XL-transgenic T cells, CD3 cross-linking induced a rapid elevation of [Ca2+]i, which subsequently declined. However, the amplitude of the [Ca2+]i flux in Bcl-XL-transgenic T cells was consistently lower than that in wild-type T cells (Fig. 5A). The peak [Ca2+]i elevation induced by CD3 ligation in wild-type T cells was 249.6 ± 10.2 nM (n = 3), compared with 177.4 ± 15.0 nM (n = 3; P < 0.025) in Bcl-XL T cells (Fig. 5B).

Figure 5.

TCR-mediated [Ca2+]i elevation is reduced in Bcl-XL transgenic T cells. (A) Analysis of Ca2+ flux upon CD3 ligation by flow cytometry. Purified splenic T cells were incubated with Indo-1 and anti-CD3. [Ca2+]i was measured by using flow cytometry, and Ca2+ release was induced by addition of cross-linking secondary antibodies. The [Ca2+]i was calibrated as described in Materials and Methods. Arrows represent time when indicated reagents were added. 2# Abs, secondary antibodies; Iono, ionomycin. (B) Peak values of [Ca2+]i elevation upon CD3 ligation shown in A were plotted as mean ± SEM from three independent experiments.

Microsomal Vesicles with Reduced IP3R Release Less Ca2+ upon IP3 Treatment.

To investigate whether decreased expression of IP3R in Bcl-XL-expressing cells directly affected intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis, we performed 45Ca2+ uptake and release experiments using purified microsomal vesicles. Microsomal vesicles from 2B4.11 Neo and Xl-C10 cell lines were prepared. Western blot analyses demonstrated very little mitochondrial contamination in the prepared microsomal vesicles (data not shown). As in 2B4.11 whole cell extracts, there was an inverse correlation between the amount of type 1 IP3R in purified microsomal vesicles and the level of Bcl-XL expression (Fig. 6A). With 500 nM free Ca2+ in the reaction buffer, microsomal vesicles were allowed to accumulate 45Ca2+ in the presence of MgATP for 30 min, at which point equilibrium was achieved (data not shown). As shown in Fig. 6B, the 45Ca2+-loaded microsomes were then treated with 10 μM IP3. When microsomal vesicles purified from control cells were used, IP3 addition resulted in the release of about 40% of total 45Ca2+, and this level was sustained over the remainder of the experiment. In contrast, vesicles purified from Bcl-XL-expressing Xl-C10 cells release less than 25% of total 45Ca2+ immediately after IP3 addition. Unlike those prepared from control cells, vesicles purified from Xl-C10 cells gradually reaccumulated the released 45Ca2+ so that 30 min after IP3 addition, more than 90% of originally accumulated 45Ca2+ was reaccumulated in the microsomes. Similar results were observed with buffers containing a range of concentrations of free Ca2+ (data not shown).

Figure 6.

Reduced amount of IP3R in microsomal vesicles is associated with reduced IP3-responsive Ca2+ release, and expressing IP3R partially reverses Bcl-XL anti-apoptotic activity. (A) Western blots of cell extracts and microsomal vesicles prepared from the indicated 2B4.11 cell lines. The filters were probed with the indicated antibodies. The Positions of molecular mass markers are shown on the left. (B) Microsomal vesicles shown in A were used in 45Ca2+ uptake and release experiments as described in Materials and Methods. After 45Ca2+ content in microsomal vesicles reached equilibrium, 10 μM IP3 was added to reactions. The microsomal 45Ca2+ contents were measured 1, 5, 10, 15, 20, and 30 min after addition of IP3. The amount of microsomal 45Ca2+ is represented as percentage of the value at equilibrium. Means and standard deviations of triplicate measurements are shown. The data are representative of three independent experiments. (C) 2B4.11 Neo and Xl-C10 cells were transfected with 3 μg of pCMV-β-gal and 15 μg of the indicated expression plasmids. The cells were cultured in the absence or presence of 200 nM thapsigargin and analyzed for cytotoxicity 20 hr later as described in Materials and Methods. Mean and standard deviations of triplicate measurements are shown, and the data are representative of three independent experiments.

Transfection of IP3R Partially Reverses Bcl-XL Anti-apoptotic Activity.

To determine whether reduced IP3R expression would account for any of the anti-apoptotic activity of Bcl-XL-expressing cells, the ability of IP3R expression to reverse Bcl-XL resistance to apoptosis was examined. Both 2B4.11 Neo and Xl-C10 cells were transiently transfected with either an IP3R-expressing plasmid or a control vector, and the susceptibility to cell death upon thapsigargin treatment was examined. IP3R expression led to a consistent but partial reduction in the ability of Bcl-XL to promote cell survival (Fig. 6C). IP3R expression had marginal effects on cell survival of control cells.

Discussion

To study whether anti-apoptotic proteins can affect gene expression under non-apoptotic conditions, we examined gene expression by microarray analysis in stable cell lines expressing high levels of the anti-apoptotic Bcl-2-related protein Bcl-XL. The type 1 IP3R was found to be the most markedly decreased transcript in Bcl-XL-overexpressing cells. The reduction of IP3R was confirmed at both the mRNA and protein levels in several hematopoietic cell types. Depolarization of mitochondria increased both NFAT binding to the IP3R promoter and the expression of IP3R, both of which were compromised by Bcl-XL overexpression. Reduced expression of IP3R correlated with a reduction in receptor-coupled Ca2+ release and a decrease in IP3-responsive Ca2+ release from microsomal vesicles prepared from Bcl-XL-expressing cells. Expression of IP3R partially compromised Bcl-XL's function to promote cell survival. Together, these data provide molecular evidence that Bcl-XL expression affects intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis through modulation of the expression of a well-established Ca2+ channel, IP3R.

The expression of Bcl-2-related proteins has been reported to affect intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis (17, 25–31), although the molecular basis of these effects has remained unclear. The compensatory reduction in IP3R expression in response to increase in expression of an anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 protein reported here may account for many of the effects previously noted. For example, expression of Bcl-2 has been previously reported to be associated with an altered distribution of intracellular Ca2+ (25), an increased mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake capacity (26), an enhanced ability of the ER to sequester Ca2+ (17, 27), a decreased total Ca2+ release in response to Ca2+-mobilizing signals (30, 31), and a reduced ability of Bcl-2-transfected cells to initiate NFAT-dependent changes in gene expression (32). The Bcl-XL-dependent reduction in IP3R expression could result in a greater sequestration of Ca2+ in the ER, lower levels of total Ca2+ release in response to IP3-dependent signal transduction, and a reduction in the Ca2+ found in the low-affinity/high-capacity mitochondrial storage pool. Finally, the ability of intracellular Ca2+ to induce NFAT-dependent transcription has been shown to be dependent on both the magnitude and duration of intracellular Ca2+ release (24). As we show here, reduction in the expression of IP3R results in a decrease in both the magnitude and duration of Ca2+ release in response to TCR signal transduction.

Bcl-XL is likely to influence IP3R mRNA and protein levels indirectly. There is currently no evidence to suggest that Bcl-XL or related Bcl-2 family members have direct effects on either transcription or translation. IP3R expression has been reported to depend on NFAT-dependent transcription (14, 22). Bcl-XL-transfected cells have lower levels of nuclear NFAT-binding activity for the IP3R promoter. This is not due to lower total NFAT levels because Bcl-XL transfectants have levels of NFAT comparable to those of controls as assayed by Western blotting and were able to induce comparable NFAT DNA-binding activity in response to phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate and ionomycin. Bcl-XL has been reported to maintain more efficient ADP-coupling of oxidative phosphorylation (16, 21); this would account for its ability to decrease both basal NFAT DNA-binding activity and the magnitude of the induction of NFAT DNA binding in response to mitochondrial uncoupling. Mitochondrial metabolic inhibitors have been reported to activate a mitochondrion-to-nucleus stress signaling network that leads to alterations in gene expression that then affect a wide variety of cellular processes (19, 20). In muscle cells, the gene with the greatest increase in response to activation of this pathway is the ryanodine receptor-1 (RYR-1) (20). The effect of this increased RYR-1 expression is to potentiate Ca2+ release and to enhance the activation of Ca2+-responsive factors, including the Ca2+-dependent NFAT. The results of the present study may therefore be accounted for by Bcl-XL modulation of a mitochondrial stress signaling pathway that in turn regulates the sensitivity of cytosolic Ca2+ signaling pathways to changes in mitochondrial metabolic function. Thus, expression of anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family members results in the decreased expression of IP3R-related ER Ca2+ release channels, leading to a reduction in the Ca2+ release in response to IP3 and a reduction in the activity of Ca2+-responsive transcription factors. In contrast, agents that impair mitochondrial electron transport and ATP production may cause reciprocal changes in these pathways, leading to an elevation in the expression of IP3-gated channels, the potentiation of Ca2+-dependent signal transduction, and enhanced activity of Ca2+-dependent transcription factors such as NFAT (19, 20).

Ca2+ plays a regulatory role in mitochondrial ATP production by enhancing the efficiency of enzymes involved in the tricarboxylic acid cycle and electron transport (5, 11). It has been reported that close contacts between the mitochondria and ER Ca2+-release channels enable high concentrations of Ca2+ in microdomains to be generated upon IP3-mediated Ca2+ release from the ER, and that these high local concentrations stimulate mitochondrial respiration in response to intracellular Ca2+ signaling (33). This respiratory control pathway is negatively regulated by ATP. When ATP levels are low, the ability of Ca2+-ATPases to sequester released Ca2+ into the ER is compromised, which could lead to a prolonged Ca2+-induced respiratory burst, and increased Ca2+-dependent signal transduction and transcription. Bcl-XL has been proposed to maintain metabolic homeostasis and ATP production by providing more efficient coupling of oxidative phosphorylation (16, 21). Enhanced cellular ATP production supported by Bcl-2 proteins would be expected to have an inhibitory effect on Ca2+-dependent signal transduction by promoting more rapid ATP-dependent Ca2+ reuptake.

Previous studies have also suggested that IP3R is directly involved in apoptosis. For example, type 1 IP3R-deficient Jurkat T cells are defective in IP3-induced Ca2+ mobilization and are resistant to apoptosis induced by a variety of death stimuli (34). However, T cells of type 1 IP3R-deficient mice demonstrated Ca2+ mobilization in response to TCR stimulation (35). This could be the result of compensatory function of other IP3R family members. Type 3 IP3R is selectively increased at both the mRNA and protein levels during apoptosis, and apoptosis is blocked by expression of type 3 IP3R antisense RNA (36, 37). Similarly, apoptosis induced by B cell receptor cross-linking is inhibited in cells lacking all three subtypes of IP3R (38). Some evidence suggests that an IP3-dependent intracellular Ca2+ signal may induce apoptosis by modulating the activity of the phosphatase calcineurin (39). Thus, one possible mechanism by which Bcl-XL may enhance the resistance to apoptosis is through its ability to reduce IP3R expression. Consistent with the possibility, reintroduction of type 1 IP3R by an expression plasmid was found to partially reverse the ability of Bcl-XL to protect cells form death. However, it is unlikely that Bcl-XL's effects on IP3R expression account for all of Bcl-XL anti-apoptotic activities, particularly those involved in opposing of the pro-apoptotic activities of Bax and Bak. Current evidence suggests that Bcl-2-related proteins may protect cells from apoptosis by multiple mechanisms. Recent studies have shed light on the issue of why reduced IP3R levels may promote cell survival. IP3-mediated Ca2+ spikes induce the opening of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore, and thereby trigger cytochrome c release that initiates apoptosis (40). One intriguing possibility is that the reduced levels of IP3R in cells expressing Bcl-XL release insufficient Ca2+ to trigger the mitochondrial permeability transition in the presence of death stimuli. The down-regulation of IP3R in response to Bcl-XL expression provides another mechanism by which anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 proteins contribute to the apoptotic resistance of a cell.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to D. Bohening and S. K. Joseph for help with microsomal vesicle experiments, to K. Foskett and S. K. Joseph for reviewing the manuscript, and to J. L. Hartman and the Chodosh laboratory for help with microarray experiments. This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health and the Abramson Family Cancer Research Institute. C.L. was also supported by National Institutes of Health Training Grant T32 CA09140.

Abbreviations

- IP3

inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate

- IP3R

IP3 receptor

- ER

endoplasmic reticulum

- SERCA

sarcoplasmic reticulum/ER Ca2+ ATPase

- NFAT

nuclear factor of activated T cells

- [Ca2+]i

cytosolic free Ca2+ concentration

- FCCP

carbonyl cyanide p-(trifluoromethoxy)phenylhydrazone

- TCR

T cell receptor

Footnotes

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

References

- 1.Adams J M, Cory S. Science. 1998;281:1322–1326. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5381.1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reed J C. Oncogene. 1998;17:3225–3236. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gross A, McDonnell J M, Korsmeyer S J. Genes Dev. 1999;13:1899–1911. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.15.1899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vander Heiden M G, Thompson C B. Nat Cell Biol. 1999;1:E209–E216. doi: 10.1038/70237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hajnóczky G, Csordas G, Madesh M, Pacher P. Cell Calcium. 2000;28:349–363. doi: 10.1054/ceca.2000.0169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gross A, Jockel J, Wei M C, Korsmeyer S J. EMBO J. 1998;17:3878–3885. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.14.3878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nechushtan A, Smith C L, Hsu Y T, Youle R J. EMBO J. 1999;18:2330–2341. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.9.2330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wei M C, Lindsten T, Mootha V K, Weiler S, Gross A, Ashiya M, Thompson C B, Korsmeyer S J. Genes Dev. 2000;14:2060–2071. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Taylor C W, Genazzani A A, Morris S A. Cell Calcium. 1999;26:237–251. doi: 10.1054/ceca.1999.0090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Patel S, Joseph S K, Thomas A P. Cell Calcium. 1999;25:247–264. doi: 10.1054/ceca.1999.0021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Duchen M R. J Physiol. 2000;529:57–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00057.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rathmell J C, Vander Heiden M G, Harris M H, Frauwirth K A, Thompson C B. Mol Cell. 2000;6:683–692. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)00066-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boehning D, Joseph S K. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:21492–21499. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001724200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Graef I A, Mermelstein P G, Stankunas K, Neilson J R, Deisseroth K, Tsien R W, Crabtree G R. Nature (London) 1999;401:703–708. doi: 10.1038/44378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Memon S A, Moreno M B, Petrak D, Zacharchuk C M. J Immunol. 1995;155:4644–4652. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vander Heiden M G, Chandel N S, Schumacker P T, Thompson C B. Mol Cell. 1999;3:159–167. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80307-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lam M, Dubyak G, Chen L, Nuñez G, Miesfeld R L, Distelhorst C W. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:6569–6573. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.14.6569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wei H, Wei W, Bredesen D E, Perry D C. J Neurochem. 1998;70:2305–2314. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1998.70062305.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Biswas G, Adebanjo O A, Freedman B D, Anandatheerthavarada H K, Vijayasarathy C, Zaidi M, Kotlikoff M, Avadhani N G. EMBO J. 1999;18:522–533. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.3.522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Amuthan G, Biswas G, Zhang S, Klein-Szanto A, Vijayasarathy C, Avadhani N G. EMBO J. 2001;20:1910–1920. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.8.1910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vander Heiden M G, Chandel N S, Li X X, Schumacker P T, Colombini M, Thompson C B. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:4666–4671. doi: 10.1073/pnas.090082297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Genazzani A A, Carafoli E, Guerini D. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;97:5797–5801. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.10.5797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Acuto O, Cantrell D. Annu Rev Immunol. 2000;18:165–184. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.18.1.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lewis R S. Annu Rev Immunol. 2001;19:497–521. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.19.1.497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baffy G, Miyashita T, Williamson J R, Reed J C. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:6511–6519. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Murphy A N, Bredesen D E, Cortopassi G, Wang E, Fiskum G. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:9893–9898. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.18.9893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.He H, Lam M, McCormick T S, Distelhorst C W. J Cell Biol. 1997;138:1219–1228. doi: 10.1083/jcb.138.6.1219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ichimiya M, Chang S H, Liu H, Berezesky I K, Trump B F, Amstad P A. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:C832–C839. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1998.275.3.C832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhu L, Ling S, Yu X, Venkatesh L K, Subramanian T, Chinnadurai G, Kuo T H. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:33267–33273. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.47.33267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Foyouzi-Youssefi R, Arnaudeau S, Borner C, Kelley W L, Tschopp J, Lew D P, Demaurex N, Krause K. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:5723–5728. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.11.5723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pinton P, Ferrari D, Magalhaes P, Schulze-Osthoff K, Di Virgilio F, Pozzan T, Rizzuto R. J Cell Biol. 2000;148:857–862. doi: 10.1083/jcb.148.5.857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Linette G P, Li Y, Roth K, Korsmeyer S J. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:9545–9552. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.18.9545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rizzuto R, Pinton P, Carrington W, Fay F S, Fogarty K E, Lifshitz L M, Tuft R A, Pozzan T. Science. 1998;280:1763–1766. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5370.1763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jayaraman T, Marks A R. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:3005–3012. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.6.3005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hirota J, Baba M, Matsumoto M, Furuichi T, Takatsu K, Mikoshiba K. Biochem J. 1998;333:615–619. doi: 10.1042/bj3330615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Khan A A, Soloski M J, Sharp A H, Schilling G, Sabatini D M, Li S H, Ross C A, Snyder S H. Science. 1996;273:503–507. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5274.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Blackshaw S, Sawa A, Sharp A H, Ross C A, Snyder S H, Khan A A. FASEB J. 2000;14:1375–1379. doi: 10.1096/fj.14.10.1375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sugawara H, Kurosaki M, Takata M, Kurosaki T. EMBO J. 1997;16:3078–3088. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.11.3078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang H, Pathan N, Ethell I M, Krajewski S, Yamaguchi Y, Shibasaki F, McKeon F, Bobo T, Franke T F, Reed J C. Science. 1999;284:339–343. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5412.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Szalai G, Krishnamurthy R, Hajnóczky G. EMBO J. 1999;18:6349–6361. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.22.6349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]