Evidence-based medicine rests on the shoulders of the peer-reviewed literature [1]. MEDLINE, maintained by the National Library of Medicine (NLM), is the largest and most widely used index of the medical literature [2]. As such, it contains the vast majority of the “evidence” that is the foundation for evidence-based medicine.

This study examines trends in the volume, authorship, content, and funding of MEDLINE articles between 1978 and 2001, a time of great change in medical research and medical practice. The authors examine these trends as a means of identifying opportunities and challenges for using this information to guide practice

METHODS

The current study examined data for all journal articles published from 1978 through 2001 and available in MEDLINE in 2003. These years were the earliest and latest for which all fields were available and indexing was complete. We included only full journal articles and excluded editorials and letters.

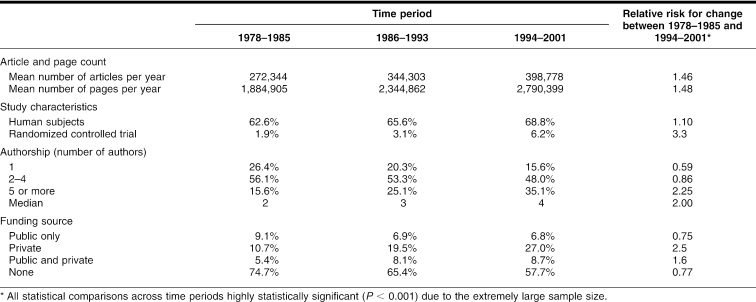

Analyses compared the number and characteristics of articles published across three 8-year eras: 1978 to 1985, 1986 to 1993, and 1994 to 2001 (Table 1). Relative risks, calculated as the ratio of each value from 1994 to 2001 divided by the corresponding number for 1978 to 1985, were used as the indicator of effect size. Because of the extremely large sample size, even minor changes were likely to be statistically significant. Therefore, a relative risk of at least 1.1 between the 1st and 3rd eras was preestablished as an effect size denoting meaningful change over time.

Table 1 Trends in MEDLINE journal articles, 1978–2001 (n = 8,123,392)

RESULTS

A total of 8.1 million journal articles were published in MEDLINE between 1978 and 2001. Between 1978 to 1985 and 1994 to 2001, the annual number of MEDLINE articles increased 46%, from an average of 272,344 to 442,756 per year, and the total number of pages increased from 1.88 million pages per year during 1978 to 1985 to 2.79 million pages per year between 1994 to 2001.

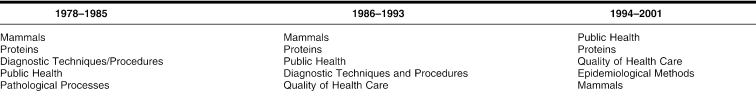

The growth in the literature was particularly concentrated in clinical research, with an increase in the proportion of studies with human subjects and a change in Medical Subject Headings, which shifted away from basic science headings toward topics related to clinical care and public health (Table 2). The proportion of randomized clinical trials tripled from 1.9% during the 1st time period to 6.2% in the final era. This combination of increasing numbers of articles and increasing proportion of randomized trials resulted in a dramatic increase in the total number of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) over the 3 eras, from 5,174 annual RCTs during the first 8 years to 24,724 RCTs per year by the final era.

Table 2 Top 5 Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

The median number of authors per publication doubled between 1978 to 1985 and 1994 to 2001, from 2 to 4, with the proportion of articles written by 5 or more authors increasing from 15.6% in the 1st era to 35.1% in the 3rd. The proportion of articles funded only through private sources increased 2.5 times from 10.7% during 1978 to 1985 to 27.0% during 1994 to 2001. This increase was accompanied by a rise in the proportion of articles funded jointly through public and private sources (RR = 1.6), a decline in articles funded only through public sources (RR = 0.75), and a decline in unfunded studies (RR = 0.77).

DISCUSSION

The study period was characterized by a major growth in the literature indexed in MEDLINE, particularly in randomized trials and other sources of information that might be used to guide evidence-based practice. At the same time, sources providing that information decentralized with an increase in the number of authors per paper and a shift from public toward private funding.

The growing number of articles, the shift toward clinical topics, and the growth of randomized trials point to an increasingly rich source of information available for guiding treatment decisions. However, this stunning growth in medical information also brings challenges and risks. While much appropriate attention has been drawn to the need for more evidence to guide practice, the sheer magnitude of that evidence can at times serve as a barrier to its effective use. Nearly 200,000 RCTs were published in MEDLINE-indexed journals between 1994 and 2001 alone.

Furthermore, MEDLINE-indexed journals represent an increasingly small portion of the broader universe of medical information. NLM estimates that currently about 14,000 biomedical journals are published and that it selects only about one-quarter of new submissions for indexing based on quality and relevance to biomedical topics [3]. These biomedical journals, in turn, represent only a small fraction of the growing array of information sources on the Web [4].

The growth of information was accompanied by a broad pattern of decentralization, both in sources of funding and in authorship. While the funding source category in MEDLINE does not distinguish between for-profit and not-for-profit private funders, industry support is by far the largest and fastest-growing source of nongovernmental funding in medical research [5] and likely the primary driver of the sharp growth in privately funded articles seen in the current study.

The rising number of authors, which supports and expands on earlier research noting this trend in particular journals [6, 7], also highlights potential tensions between increased diversity and reduced accountability. In part, the increase in multiple authorship represents a shift in the research paradigm toward multidisciplinary research teams and multicenter trials. However, editors and researchers have expressed growing concern that, as the number of authors rises, identifying contributions of and assigning responsibility to each of the contributors becomes increasingly difficult [8, 9].

How are clinicians, researchers, and librarians to make sense of this growing quantity and range of sources of clinical information? The study's findings suggest the importance of three related approaches. First, it is critical for all users of the literature to develop active reading skills that allow them to efficiently search this enormous body of literature, to identify potential biases, and to sort the wheat from the chaff [1].

Second, as the size and scope of information continues to grow, “prefiltered” sources such as reviews, clinical guidelines, and the Cochrane Library are becoming increasingly indispensable for clinicians and researchers seeking to synthesize the literature. As these sources become increasingly important, it will be essential to ensure their continued accessibility, integrity, and quality [10].

Finally, ensuring the accountability and impartiality of the articles published in the peer-reviewed literature is essential. The growth of multiple authorship highlights the importance of supporting and expanding collaborative editorial efforts to ensure explicit role definition and responsibility among contributors [11]. The expansion of privately funded research underlines the importance of transparent and full disclosure of competing financial interests [12].

This study's findings should be interpreted in the light of at least two limitations. First, while MEDLINE is the largest index of biomedical literature, it is, by design, a peer-reviewed subset of the universe of biomedical information. The main study findings, including both the increasing quantity and decentralization, would be expected to be substantially more pronounced in that broader environment. Second, most of the fields in MEDLINE rely on authors and/or indexers for accurate coding. This reliance might lead to underreporting certain fields, such as funding sources for journal articles.

The study's findings at once present challenges and opportunities for evidence-based medicine. The growth of published clinical research during the past quarter century suggests an enormous potential for using that information to improve care. However, transforming this information into useful evidence will require vigilance on the part of the researchers who produce it, the clinicians who use it, and the editors and medical librarians who serve as translators between research and clinical practice.

Contributor Information

Benjamin G. Druss, Email: bdruss@emory.edu.

Steven C. Marcus, Email: marcuss@ssw.upenn.edu.

REFERENCES

- Guyatt G, Rennie D. Users' guides to the medical literature: a manual for evidence-based clinical practice. Chicago, IL: AMA Press, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Lacroix EM, Mehnert R. The US National Library of Medicine in the 21st century: expanding collections, nontraditional formats, new audiences. Health Info Libr J. 2002 Sep; 19(3):126–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Library of Medicine. Response to inquiries about journal selection for indexing at NLM. [Web document]. The Library. [cited Dec 2004]. <http://www.nlm.nih.gov/pubs/factsheets/j_sel_faq.html>. [Google Scholar]

- Eysenbach G, Powell J, Kuss O, and Sa ER. Empirical studies assessing the quality of health information for consumers on the World Wide Web: a systematic review. JAMA. 2002 May 22–29; 287(20):2691–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Science Foundation. Science and engineering indicators. Arlington, VA: The Foundation, 2004 (NSB 04–01). [Google Scholar]

- Epstein RJ. Six authors in search of a citation: villains or victims of the Vancouver convention? BMJ. 1993 Mar 20; 306(6880):765–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drenth JP. Multiple authorship: the contribution of senior authors. JAMA. 1998 Jul 15; 280(3):219–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro DW, Wenger NS, and Shapiro MF. The contributions of authors to multiauthored biomedical research papers. JAMA. 1994 Feb 9; 271(6):438–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flanagin A, Carey LA, Fontanarosa PB, Phillips SG, Pace BP, Lundberg GD, and Rennie D. Prevalence of articles with honorary authors and ghost authors in peer-reviewed medical journals. JAMA. 1998 Jul 15; 280(3):222–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen O, Middleton P, Ezzo J, Gotzsche PC, Hadhazy V, Herxheimer A, Kleijnen J, and McIntosh H. Quality of Cochrane reviews: assessment of sample from 1998. BMJ. 2001 Oct 13; 323(7317):829–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rennie D, Yank V, and Emanuel L. When authorship fails. a proposal to make contributors accountable. JAMA. 1997 Aug 20; 278(7):579–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross CP, Gupta AR, and Krumholz HM. Disclosure of financial competing interests in randomised controlled trials: cross sectional review. BMJ. 2003 Mar 8; 326(7388):526–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]