Abstract

The regulatory effect of growth hormone (GH) on its target cells is mediated via the GH receptor (GHR). GH binding to the GHR results in the formation of a GH-(GHR)2 complex and the initiation of signal transduction cascades via the activation of the tyrosine kinase JAK2. Subsequent endocytosis and transport to the lysosome of the ligand-receptor complex is regulated via the ubiquitin system and requires the presence of an intact ubiquitin-dependent endocytosis (UbE) motif in the cytosolic tail of the GHR. Recently, the model of ligand-induced receptor dimerization has been challenged. In this study, ligand-independent GHR dimerization is demonstrated in the endoplasmic reticulum and at the cell surface by coimmunoprecipitation of an epitope-tagged truncated GHR with wild-type GHR. In addition, evidence is provided that the extracellular domain of the GHR is not required to maintain this interaction. Internalization of a chimeric receptor, which fails to dimerize, is independent of an intact UbE-motif. Therefore, we postulate that dimerization of GHR molecules is required for ubiquitin system-dependent endocytosis.

Postnatal growth as well as lipid and carbohydrate metabolism is regulated by growth hormone (GH). GH effects are mediated by means of the GH receptor (GHR), a type I transmembrane glycoprotein that belongs to the cytokine receptor superfamily. In addition to GHR, this family includes the receptors for erythropoietin (Epo), prolactin, thrombopoietin, leptin, ciliary neurotrophic factor, leukemia inhibitory factor, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor, and several of the ILs (1). Although the overall homology between members is limited, some conserved motifs have been identified (reviewed in ref. 2). Their extracellular domain contains pairs of disulfide-linked cysteine residues and a WSXWS (tryptophan, serine, any amino acid, tryptophan, serine) motif, which is indirectly involved in ligand binding (3). All cytokine receptors lack intrinsic kinase activity. Instead, a conserved proline-rich domain in their cytosolic tail, box 1, functions as a binding site for members of the JAK tyrosine kinase family. In case of GHR, ligand binding results in the activation of JAK2 molecules (4), which in turn phosphorylate tyrosine residues in the receptor cytosolic tail and down-stream signaling molecules (reviewed in ref. 5). The ligand-receptor complex is internalized via clathrin-coated vesicles and subsequently transported via endosomes to lysosomes (6–8). We have shown that both endocytosis and transport to lysosomes require an active ubiquitin-conjugation system and can be inhibited by proteasome inhibitors (9–11). In particular, a 10-amino acid motif [ubiquitin-dependent endocytosis (UbE)-motif, DSWVEFIELD] in the cytosolic tail of the GHR is essential because mutations here, for instance F327A, inhibit GHR ubiquitination, internalization, and degradation (10, 12).

Based on crystallographic data of GH bound to GHR extracellular domains, it has been postulated that a single GH molecule dimerizes two GHR molecules after which signaling is initiated (3, 13). However, dimerization itself is not sufficient for signal transduction because administration of mAbs directed to the extracellular domain of the GHR resulted in dimerized GHRs but failed to induce signal transduction (14). The GHR extracellular domain contains two subdomains, which are separated by a hinge region (3). With an Ab raised against this hinge region, Mellado et al. (15) demonstrated a conformational change after ligand binding. Recognition of the GHR by this Ab improved after GH binding but not when the GH antagonist GH(G120R), with only one intact GHR binding site, was used (15). Recently, Ross et al. (16) used the mAb Mab5, which was postulated to interfere with GHR dimerization, and demonstrated an increase in the number of binding sites for GH as well as GH antagonist B2036, which also contains one defective GHR binding site. It suggests that B2036 binds to a preformed receptor dimer (16). More evidence was provided by crosslinking studies with 125I-labeled GH or GH antagonist. Complexes similar in size and corresponding to a ligand:GHR stoichiometry of 1:2 were detected for both ligands (17, 18). Taken together, these data predict the presence of preformed GHR dimers at the cell surface as was also recently proposed for the Epo receptor (EpoR) based on crystallographic data (19, 20) and Ab-mediated immunofluorescence copatching of epitope-tagged EpoRs (21).

Here, we show that GHR is dimerized in the absence of ligand in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and at the cell surface. Our data suggest that the extracellular domain of the GHR is not essential for the maintenance of this interaction. Internalization of a chimeric protein, which fails to dimerize, is independent of an intact UbE-motif, suggesting that dimerization is a prerequisite for ubiquitin system-dependent endocytosis.

Materials and Methods

Abs and Materials.

Anti-GHR rabbit antisera anti-T, -B, and -C were raised as described (9, 10). Mouse mAb Mab5 recognizing the luminal part of the GHR was from AGEN (Parsippany, NJ). Monoclonal anti-hemagglutinin (HA) Ab 16B12 was purchased from Babco (Richmond, CA) and anti-Myc (9E10) from Upstate Biotechnology (Lake Placid, NY). LipofectAMINE was from Invitrogen and carbobenzoxy-l-leucyl-l-leucyl-l-leucinal (MG-132) was from Calbiochem. Human GH was kindly provided by Eli Lilly (Indianapolis). Recombinant receptor-associated protein (RAP) was expressed and isolated as described (22).

Constructs and Cell Lines.

Full-length rabbit GHR encoded by a pCB6 plasmid (9) or mutated GHRs encoded by pcDNA3 (Invitrogen) plasmids were used (Fig. 1). The construction of the truncation mutant GHR (1–434) was described (7). The GHR(1–434; F327A) mutant was created with the QuickChange Site-Directed Mutagenesis kit (Stratagene). In a PCR, 3′ and 5′ oligonucleotides encoding for the F327A mutation and a silent mutation deleting a ClaI restriction site were used. A triple epitope-tagged version of a truncated GHR (GHR1–369; HA-His-6-Myc) was constructed by PCR with a 5′ oligonucleotide containing an NcoI restriction site, corresponding to the NcoI site in the transmembrane domain (TMD) cDNA sequence, and a 3′ oligonucleotide that introduces an HA (YPYDVPDY), six histidine residues (His-6), a c-Myc epitope-tag (EQKLISEEDL), and a stop codon after amino acid 369. The LRP4GHR (245–434) chimer, consisting of the low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein (LRP) ligand-binding domain 4 (LRP4) fused to the GHR transmembrane and truncated cytosolic domain, was created in multiple steps. First, with mLRP4T100 in pcDNA3 (23) as template, the cDNA sequence encoding an HA epitope and the LRP4 (amino acids 3274–4399) was amplified by PCR with a 5′ oligonucleotide introducing XbaI and KpnI restriction sites and a 3′ oligonucleotide introducing an NcoI restriction site. Subsequently, with the XbaI and NcoI restriction sites, the PCR product was ligated into a pGEM plasmid encoding the carboxyl-terminal truncated GHR (1–434) mutant, thereby creating the LRP4GHR (245–434) chimer. The obtained cDNA was subcloned into the pcDNA3 vector after digestion with KpnI. The LRP4GHR(245–434; F327A) mutant was created with the QuickChange Site-Directed Mutagenesis kit as described previously for the GHR(1–434; F327A) mutant. The LRP4GHR(245–334; Myc) mutant was prepared by PCR with a 5′ oligonucleotide with a PpuMI restriction site corresponding to the site in the LRP ligand-binding domain, and a 3′ oligonucleotide introducing a c-Myc tag and a stop codon after amino acid 334 of the GHR cytosolic domain. All constructs were verified by restriction analysis, in vitro transcription/translation assays, and/or sequencing.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of wt and mutant GHRs. The GHR mutants were constructed as described in Materials and Methods. The numbers correspond to the amino acids of wtGHR. The black box indicates the GHR TMD. The numbered boxes represent conserved cytosolic domains of cytokine receptor family members. Box B1 indicates the proline-rich domain involved in signal transduction. Box B2 is a conserved region, which includes the UbE-motif (DSWVEFIELD), required for GHR ubiquitin-dependent endocytosis. Inactivation of the UbE-motif by the F327A mutation is indicated by A. The specific regions recognized by the receptor Abs anti-T and anti-C are indicated. The position of the hemagglutinin, His-6, or Myc epitope tags in the mutants is indicated. The hatched box represents the LRP4, which was constructed in place of the GHR extracellular domain.

For expression, Chinese hamster ts20 cells (24) were used. Clonal cell lines stably expressing the GHR constructs were obtained with the calcium phosphate transfection method. For transient transfections, LipofectAMINE was used according to the manufacturer's description. Cells were used for experiments 48 h after transfection. Cells were cultured at 30°C in MEMα supplemented with 10% FCS, 4.5 g/liter of glucose, 100 units/ml of penicillin, 100 μg/ml of streptomycin, and 450 μg/ml of geneticin. For experiments, cells were treated for 16 h with 10 mM butyrate to increase the GHR expression (9).

Coimmunoprecipitations and Proteinase K Treatment.

Cells were grown in 6-well plates and washed 3 times with ice-cold PBS supplemented with 0.4 mM Na3VO4. Proteinase K was performed as described (18). Cells were lysed on ice in 0.6 ml of lysis buffer containing 0.5% Triton X-100, 1 mM EDTA, 50 mM NaF, 1 mM Na3VO4, 10 μg/ml of aprotinin, 10 μg/ml of leupeptin, 1 mM PMSF, and 2 μM MG-132 in PBS. Lysates were cleared by centrifugation at 16,000 × g and supernatants subjected to immunoprecipitation with the indicated Abs. Immune complexes were isolated with Protein A (Repligen) or Protein G (Sigma) conjugated to agarose beads. The immunoprecipitates were washed twice with lysis buffer and twice with PBS. The proteins were subjected to SDS/PAGE with the Ready Gel precast gel system (Bio-Rad) and transferred to poly(vinylidene difluoride) paper. Blots were immunostained with the indicated Abs followed by peroxidase-conjugated protein A or rabbit anti-mouse IgG (Pierce). Detection was performed with enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). When indicated, blots were reprobed after stripping 2 times 30 min with 0.15 M NaCl/50 mM glycine (pH 2.2) buffer.

Ligand Binding, Internalization, and Degradation.

125I-labeled human GH and 125I-labeled recombinant RAP were prepared with the chloramine T method (9). For internalization studies, cells were grown in 12-well plates and preincubated 60 min at 30°C in MEMα supplemented with 20 mM Hepes, pH 7.5/0.1% BSA. After a 6-min incubation at 30°C with 125I-labeled human GH (8 nM) or 125I-labeled recombinant RAP (5 nM), unbound radioactivity was removed and incubations were continued in medium without ligand. Acid-soluble radioactivity in the medium was determined after trichloroacetic acid precipitation (10). The acid-precipitable radioactivity determined the release of intact ligand. Membrane-associated ligand was removed from the cells with acid wash buffer (0.15 M NaCl/50 mM glycine/0.1% BSA, pH 2.2) for 2 times 5 min on ice. Internalized ligand was determined by solubilization of the acid-treated cells in 1 M NaOH. Radioactivity was measured with an LKB Compugamma counter. Nonspecific radioactivity was determined in the presence of 50 times excess unlabeled ligand and subtracted.

Results

Ligand-Independent GHR Dimerization.

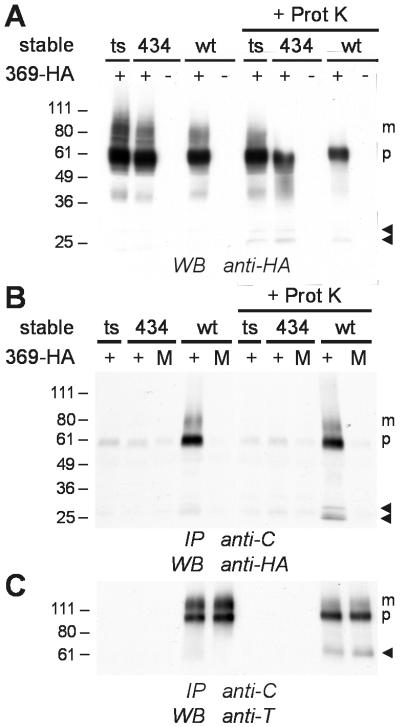

To investigate the possibility of ligand-independent interaction between GHR molecules, we performed coimmunoprecipitation experiments. Chinese hamster ts20 cells stably expressing wild-type GHR (wtGHR) or the truncation mutant GHR (1–434) were transiently transfected with an expression vector encoding the triple epitope-tagged GHR(1–369; HA-His-6-Myc). Neither the truncations nor the presence of the epitope tags in the different mutants affects the appearance of receptors at the cell surface (data not shown). Cell extracts were immunoprecipitated with anti-C, an Ab recognizing the C-terminal part of the wt but not the truncated GHR species used in this experiment (Fig. 1). Lysates and immunoprecipitates were analyzed on Western blot with an Ab directed against the HA epitope present in the GHR(1–369; HA-His-6-Myc) mutant. As demonstrated in Fig. 2A, equal amounts of high-mannose-glycosylated precursor (p) and complex-glycosylated mature (m) GHR(1–369; HA-His-6-Myc) polypeptides were expressed in the different cell lines. After immunoprecipitation of wtGHR with anti-C Ab, both the precursor and mature form of GHR(1–369; HA-His-6-Myc) coimmunoprecipitated (Fig. 2B, lane 4). Because only ternary complexes composed of one ligand and two GHR molecules have been identified in crosslinking experiments (17, 18), we postulate that the observed interaction between wtGHR and mutant GHR molecules is a result of heterodimer formation. The specificity of the immunoprecipitation was determined by transient expression of GHR(1–369; HA-His-6-Myc) into untransfected or GHR (1–434)-expressing ts20 cells. Under those conditions no HA signal was observed after anti-C immunoprecipitation (Fig. 2B, lanes 1 and 2). To exclude the possibility that the interaction between the GHRs was an artifact occurring after lysis of the cells, we mixed lysates of wtGHR-expressing cells with lysates of ts20 cells transiently expressing GHR(1–369; HA-His-6-Myc). Although similar amounts of the full-length receptor were present as was demonstrated by reprobing the same blot with anti-T, an Ab against the membrane-proximal domain of the GHR (Fig. 2C, lanes 4 and 5), the epitope-tagged GHR mutant was not coimmunoprecipitated with wtGHR (Fig. 2B, lane 5). Because the transfection efficiency is low, many cells expressed wtGHR but not the mutant receptor. Therefore, after immunoprecipitation with anti-C the amount of wtGHR is much higher than that of the coimmunoprecipitated mutant receptor. Together, these data show that GHR dimerization occurs between high-mannose-glycosylated precursor species of GHR polypeptides, presumably in the rough ER, and between complex-glycosylated species in the Golgi and at the cell surface.

Figure 2.

Ligand-independent GHR dimerization. Untransfected ts20 cells (ts) and ts20 cells stably expressing GHR (1–434) (434) or wtGHR (wt), were used to transiently express GHR(1–369; HA-His-6-Myc) (369-HA). When indicated, a proteinase K digestion (+ Prot K) was performed on ice before cell lysis. Cells were lysed under mild conditions and the lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-C, recognizing only wtGHR. In control experiments, lysates of ts20 cells transiently expressing GHR(1–369; HA-His-6-Myc) and lysates of wtGHR- or GHR (1–434)-expressing cells were mixed (M lanes) before the immunoprecipitation. Lysates and immunoprecipitates were analyzed by SDS/PAGE (4–20% gradient gel) and Western blotting. (A) Level of GHR(1–369; HA-His-6-Myc) expression in the different cell lines. Blots of cell lysates were immunostained with anti-HA Ab. (B) Coimmunoprecipitations of GHR(1–369; HA-His-6-Myc) and wtGHR. Anti-C immunoprecipitates were analyzed by Western blot detection with anti-HA Ab. (C) Efficiency of immunoprecipitation of wtGHR as determined by reprobing the blot shown in B with anti-T Ab. m, mature receptor; p, precursor receptor; arrowheads, membrane-bound remnants of proteinase K processed receptors; IP, immunoprecipitation; WB, Western blot detection. Relative molecular weight standards (Mr × 10−3) are shown at the left.

We also investigated whether GH could stimulate the formation of GHR dimers. In that case, GH binding on ice before lysis would result in an increase in the amount of coimmunoprecipitated cell surface-localized mature GHR(1–369; HA-His-6-Myc). As a control we used the monovalent GH antagonist B2036, which has a defective GHR binding site 2. For both ligands, the amount of mature GHR(1–369; HA-His-6-Myc) coimmunoprecipitated with wtGHR did not change (data not shown).

The Extracellular Domain Is Not Essential for GHR Dimerization.

When the crystal structure of the GH-(GHR extracellular domain)2 complex was solved, several amino acids in the extracellular domain of the GHR were proposed to play a role in GHR–GHR interaction (3). To determine whether the extracellular domain is required for ligand-independent GHR dimerization, cells were treated on ice with proteinase K before coimmunoprecipitation. In this way, the extracellular domain of cell surface-localized GHRs is digested whereas the TMD and intracellular domain remain intact. These membrane-bound remnants resemble those that remain after shedding of the GHR extracellular domain, a process that occurs at the cell surface in the absence of GH (18, 25). As seen in Fig. 2A Right, proteinase K digested a great portion of the mature but not the precursor form of GHR(1–369; HA-His-6-Myc). Instead, bands corresponding to the membrane-bound remnants, indicated by the arrowheads, were detected. These remnants also coimmunoprecipitated with the anti-C Ab (Fig. 2B, lane 9). In addition, coimmunoprecipitation of the precursor and mature receptors, which were present in the biosynthetic compartments and therefore not affected by the proteinase K treatment, was observed. Because the majority of the mature wtGHR molecules were affected by proteinase K as well (Fig. 2C, lane 9), the data reveal an interaction between proteinase K-digested GHR(1–369; HA-His-6-Myc) and wtGHR species. It demonstrates that the extracellular domain is not essential to maintain the interaction between GHR molecules.

Internalization of the LRP4GHR (245–434) Chimer Is Independent of the UbE-Motif.

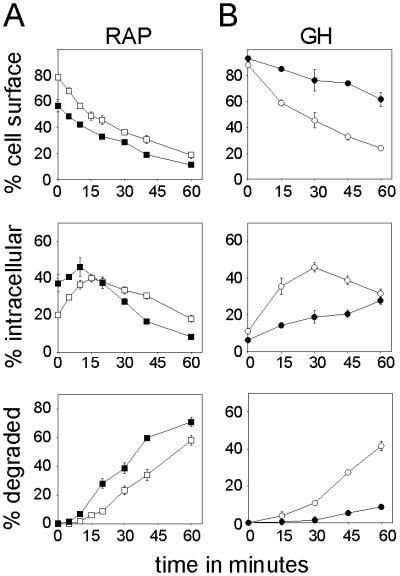

To investigate the role of the extracellular domain in GHR function further, we replaced it with the HA epitope-tagged LRP4 of the LRP. LRP is a member of the low-density lipoprotein receptor gene family of endocytic receptors (26–28). The 39-kDa RAP can be used as a ligand (23). Internalization of cell-surface bound recombinant RAP is rapid and after dissociation from the receptor in the endosomes, it is transported to the lysosome whereas the LRP recycles back to the plasma membrane (29). We used a GHR with a cytosolic tail, truncated after amino acid 434. Removal of the distal part (amino acids 435–620) of the GHR cytosolic tail has no effect on GH binding and internalization (7). Replacement of the GHR extracellular domain by the LRP4 has no effect on the appearance at the cell surface as was determined by cell surface biotinylation of cells stably expressing LRP4GHR (245–434) (data not shown). Uptake of 125I-labeled RAP in ts20 cells stably expressing LRP4GHR (245–434) chimer was performed as described in Materials and Methods. At the indicated times, the percentages of cell surface-associated, internalized, and degraded RAP were determined. Fig. 3A Top shows that after a 6-min pulse about 80% of the total cell-associated RAP was located at the cell surface. After incubation the ligand disappeared from the cell surface and accumulated intracellularly (Fig. 3A Middle). After 15 min the amount of intracellular RAP decreased with the concomitant increase of trichloroacetic acid-soluble counts appearing in the medium (Fig. 3A Bottom), indicating degradation of the ligand. The uptake and degradation of 125I-labeled RAP via LRP4GHR (245–434) was accelerated compared with the uptake of 125I-labeled GH via GHR (1–434) (Fig. 3B, open circles).

Figure 3.

Internalization of the LRP4GHR (245–434) chimer is UbE-motif-independent. After incubation for 6 min in the presence of 125I-labeled ligand, unbound radioactivity was removed and cells were chased in the absence of ligand. At the indicated times the amounts of cell surface (Top), intracellular (Middle), and degraded (Bottom) ligand were determined as described in Materials and Methods. The amount of radioactivity was expressed as percentage of total radioactivity. Each point represents the mean value of at least 2 independent experiments performed in duplicate ± SD. (A) 125I-labeled RAP uptake by ts20 cells expressing LRP4GHR (245–434) (open squares) or LRP4GHR(245–434; F327A) (closed squares). (B) 125I-labeled GH uptake by ts20 cells expressing GHR (1–434) (open circles) or GHR(1–434; F327A) (closed circles).

To investigate whether an intact UbE-motif, and therefore the ubiquitin system, is required for RAP uptake, the LRP4GHR(245–434; F327A) mutant was created. Disruption of the UbE-motif by the F327A mutation prevents GHR ubiquitination and internalization (7). As illustrated in Fig. 3A, internalization and degradation of 125I-labeled RAP by means of the LRP4GHR(245–434; F327A) receptor was accelerated rather than inhibited (Fig. 3A, closed squares). In contrast, the same mutation in GHR (1–434) clearly inhibited 125I-labeled GH uptake and degradation (Fig. 3B, closed circles). The significance of this effect was explored with proteasome inhibitors. In the presence of the proteasome-inhibitor MG-132, the internalization of RAP was barely affected, whereas the internalization of GH via GHR (1–434) was severely reduced (data not shown). Thus, opposed to GHR (1–434), the internalization of the chimeric LRP4GHR (245–434) receptor is ubiquitin system- and proteasome-independent.

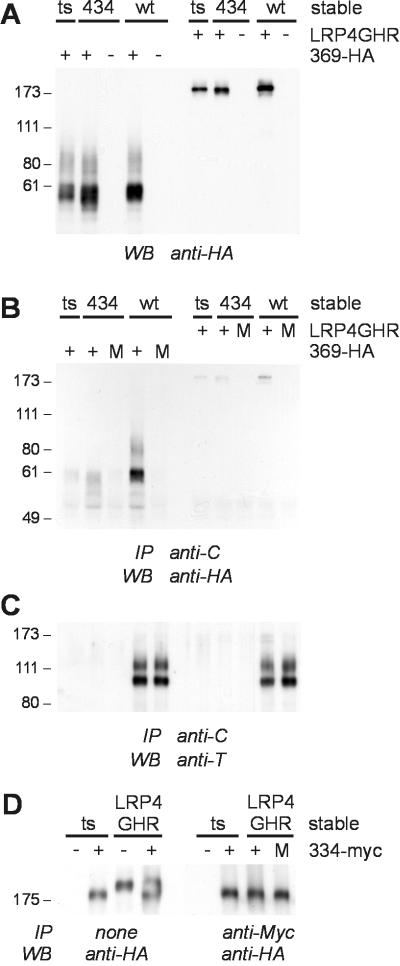

The LRP4GHR (245–434) Chimer Fails to Dimerize.

The finding that replacement of the extracellular domain of the GHR changes its internalization mode, which is mainly determined by motifs in the cytosolic tail (30), urges the question of whether this chimeric receptor is still able to form dimers. To this end a coimmunoprecipitation experiment was performed with LRP4GHR (245–434) chimer transiently expressed in ts20 cells, which stably expressed wtGHR or GHR (1–434). As a control, we used GHR(1–369; HA-His-6-Myc). Western blot detection of lysates with an Ab directed against the HA epitope present demonstrated that the expression levels of GHR(1–369; HA-His-6-Myc) in the different cell lines were comparable, as were the levels of LRP4GHR (245–434) (Fig. 4A). Unlike the GHR(1–369; HA-His-6-Myc) mutant, the LRP4GHR (245–434) chimer did not specifically coimmunoprecipitate with wtGHR (Fig. 4B). Reprobing the same blot with anti-T, an Ab directed against the membrane-proximal region of the GHR, revealed equal amounts of immunoprecipitated wtGHR (Fig. 4C).

Figure 4.

The LRP4GHR (245–434) chimer fails to dimerize. Coimmunoprecipitations were performed as described for Fig. 2. LRP4GHR (245–434) (LRP4GHR) was transiently expressed in untransfected (ts), GHR (1–434) (434), or wtGHR (wt) stably expressing ts20 cells. As a control GHR(1–369; HA-His-6-Myc) (369-HA) was expressed similarly. (A) Expression levels of GHR(1–369; HA-His-6-Myc) and LRP4GHR (245–434) in the different cell lines as determined by Western blot detection of cell lysates with anti-HA Ab. (B) Coimmunoprecipitation of GHR(1–369; HA-His-6-Myc) but not LRP4GHR (245–434) with wtGHR. Anti-C immunoprecipitates were immunoblotted with anti-HA Ab. (C) Efficiency of immunoprecipitation of wtGHR as determined by reprobing the blot shown in B with anti-T Ab. (D) LRP4GHR (245–434) and LRP4(GHR(245–334; Myc) do not dimerize. Ts20 cells stably expressing LRP4GHR (245–434) were used to transiently express LRP4GHR(245–334; Myc). Immunoprecipitations were performed with anti-Myc Ab. Blots containing lysates and immunoprecipitates were immunostained with anti-HA Ab. M, mix of lysates of ts20 cells transiently expressing GHR(1–369; HA-His-6-Myc), LRP4GHR (245–434), or LRP4GHR(245–334; Myc), and lysates of ts20 cells stably expressing GHR (1–434), wtGHR, or LRP4GHR (245–434); m, mature receptor; p, precursor receptor; IP, immunoprecipitation; WB, Western blot detection. Relative molecular weight standards (Mr × 10−3) are shown at the left.

Because the absence of heterodimerization between wtGHR and LRP4GHR (245–434) could be the result of a sterical clash between the different extracellular domains, we examined the possibility of dimerization between two LRP4-containing proteins. We transiently expressed LRP4GHR(245–334; Myc) in ts20 cells stably expressing the LRP4GHR (245–434) chimer. This truncated and Myc epitope-tagged chimer has a slightly higher mobility on SDS/PAGE as can be seen by Western blot analysis of lysates with anti-HA Ab (Fig. 4D Left). After immunoprecipitation with anti-Myc Ab and immunoblotting with anti-HA Ab, coimmunoprecipitation of LRP4GHR (245–434) was not observed (Fig. 4D Right). In contrast, in similar experiments with GHR (1–434) and GHR(1–334; Myc), the different GHRs did interact (data not shown). Thus, replacement of the GHR extracellular domain by the LRP4 creates a chimeric protein, which fails to dimerize and, at the same time, internalizes ubiquitin system- and proteasome-independently.

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrate that GHR molecules occur as complexes in the ER and at the cell surface (Fig. 2). In addition, we show that complexed GHRs enter the cells ubiquitin system-dependent, whereas monomeric receptor chimers endocytose ubiquitin system-independent (Figs. 3 and 4). The observed complexes most likely comprise receptor dimers, analogous to the EpoR (21), the epidermal growth factor (EGF) receptor (31), MHC class II α and β molecules (32), and type I and II transforming growth factor β receptors (33). The data are consistent with earlier crosslinking studies with GH or GH antagonist, revealing a large ternary protein complex of one ligand and two receptor molecules (17, 18).

Whereas the dimerization status is important for the ubiquitin system-dependent endocytosis, the actual dimerization most probably occurs in the ER. As for most multimeric protein complexes, the ER offers the best environment because of the high concentration of chaperones. In addition, during or immediately after translocation into the ER lumen, local GHR concentrations are presumably high as a single GHR mRNA-programmed polyribosome inserts multiple GHR precursors in close proximity in the ER membrane (34). Once dimerized, it is likely that GHR receptors stay associated during transport to the cell surface. The presence of GHR dimers at the plasma membrane offers an advantage for rapid signaling. First, as GH binding is thought to be sequential (13), there is no time lost in recruiting a second receptor to the GH–GHR complex. Second, low ligand concentrations might still be able to initiate receptor signaling, which is especially advantageous in cells with low GHR levels.

How is GHR dimerization achieved? The crystal structure of GH bound to two GHR extracellular domains has demonstrated an interaction between the membrane-proximal regions, referred to as subdomain 2, of adjacent GHRs (3). Mutation of conserved amino acids in this domain disrupts ligand-induced signal transduction presumably by preventing receptor dimerization (35). In contrast, our proteinase K experiment demonstrates that the extracellular domain of the GHR is not required to maintain GHR dimerization (Fig. 2), which implies that either the TMD or the cytosolic domain or both contain the dimerizing domain. A role for the latter seems unlikely because cotransfection of a full-length GHR and a signaling-deficient GHR truncation mutant, lacking most of the cytosolic domain, decreases the signaling capacity of the cells probably by formation of heterodimers (36). Therefore, we speculate that the dimerization of the GHR is mediated by way of the TMD, which is in accordance with recent findings that the TMD of the EpoR (21), the EGF receptor (37), the MHC class II α and β subunits (32), and glycophorin A (38) are sufficient for (ligand-independent) dimerization. The proposed model also explains why in gel filtration experiments a complex of a monovalent GH antagonist and two extracellular GH-binding domains has never been identified, whereas such a complex was observed when normal, divalent GH was used (25, 39). Although the TMD is required for dimerization, it may not be sufficient. Cytosolic and/or ER luminal proteins could facilitate the folding and positioning of the intracellular and extracellular domain such that the TMDs can dimerize. Our finding that the chimeric receptor lacking the GHR extracellular domain but containing the GHR TMD does not dimerize supports a role for the extracellular domain. Thus, the extracellular domain, albeit not involved in keeping the receptors together, might function in the assembly process.

Strikingly, dimerization is required for endocytosis via the ubiquitin-proteasome system: a chimeric, nondimerizing receptor endocytoses rapidly and ubiquitin-system independent. Apparently, the machinery involved in ubiquitin-dependent endocytosis of the GHR targets only receptor dimers. As all dimerizing GHRs tested require the ubiquitin system for their endocytosis, the observation also indicates that all of the GHRs at the cell surface are in a dimerized state (9). The mechanism of LRP4GHR (245–434) chimer internalization remains unclear. Both the chimer and the GHR (1–434) possess identical cytosolic domains. Apparently, the GHR tail contains other internalization motifs, besides the UbE-motif, which become active in monomeric GHRs. Internalization of the GHR (1–349) truncation mutant was demonstrated to be ubiquitin system-independent and mediated by means of a dileucine-based internalization motif (40). However, this dileucine motif is inactive in GHRs with longer cytosolic tails.

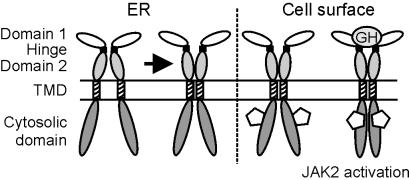

Taken together, the current model of ligand-induced GHR dimerization has to be revised. We propose that GHR dimerization occurs in the ER (Fig. 5), which might require an initial interaction between subdomain 2 of the extracellular domain, which can be facilitated by ER chaperones. Thereupon, the TMDs interact and lock the GHR in a dimeric state. The extracellular domain is then no longer required for dimerization. It is likely that the receptors remain associated during transport to the cell surface. There, GH binding to the complex induces a conformational change, which enables activation of JAK2 molecules. This model is in agreement with the findings that a monovalent GH antagonist can be found in a ternary complex with two GHR molecules but is unable to initiation signal transduction (17, 18). The observed inhibition of cellular responses at high GH levels (e.g., the bell-shaped dose-response curve) (41) is most likely the result of the formation of a signaling-incompetent (GH)2–(GHR)2 complex by the simultaneous binding of GH molecules by way of site 1 to the two GHR molecules of the complex. Because there is substantial evidence that EpoR dimerization also occurs by means of the TMD (21), the proposed dimerization mechanism might be a general scenario for other members of the cytokine receptor family.

Figure 5.

Hypothetical model of GHR dimerization. Dimerization of GHRs occurs in ER and is maintained during transport to the cell surface. The GHR extracellular domain is composed of an N-terminal GH binding domain 1 and a membrane-proximal domain 2, which can interact with domain 2 of an adjacent GHR in the GH–(GHR)2 complex. ER chaperones might facilitate this interaction. A hinge region separates the two domains. Stabilization of the dimer can be mediated by interaction between the TMD of two GHRs. At the cell surface, GH binding induces a conformational change that enables JAK2 tyrosine kinase molecules to be activated.

Acknowledgments

We thank Toine ten Broeke for preparation of the epitope-tagged truncated GHR construct and Julia Schantl and Martin Sachse for helpful suggestions. This work was supported by The Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research Grants NWO-902-23-192 and NWO-902-16-222 and by European Union Network Grant ERBFMRXCT96-0026.

Abbreviations

- GH

growth hormone

- GHR

GH receptor

- TMD

transmembrane domain

- ER

endoplasmic reticulum

- HA

hemagglutinin

- LRP

low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein

- RAP

receptor-associated protein

- Epo

erythropoietin

- EpoR

Epo receptor

- wt

wild type

- UbE

ubiquitin-dependent endocytosis

- LRP4

LRP ligand-binding domain 4

References

- 1.Bazan J F. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:6934–6938. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.18.6934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carter-Su C, Schwartz J, Smit L S. Annu Rev Physiol. 1996;58:187–207. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.58.030196.001155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Vos A M, Ultsch M, Kossiakoff A A. Science. 1992;255:306–312. doi: 10.1126/science.1549776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Argetsinger L S, Campbell G S, Yang X, Witthuhn B A, Silvennoinen O, Ihle J N, Carter-Su C. Cell. 1993;74:237–244. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90415-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Herrington J, Carter-Su C. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2001;12:252–257. doi: 10.1016/s1043-2760(01)00423-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Murphy L J, Lazarus L. Endocrinology. 1984;115:1625–1632. doi: 10.1210/endo-115-4-1625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Govers R, van Kerkhof P, Schwartz A L, Strous G J. EMBO J. 1997;16:4851–4858. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.16.4851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sachse M, van Kerkhof P, Strous G J, Klumperman J. J Cell Sci. 2001;114:3943–3952. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.21.3943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Strous G J, van Kerkhof P, Govers R, Ciechanover A, Schwartz A L. EMBO J. 1996;15:3806–3812. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van Kerkhof P, Govers R, Alves dos Santos C M, Strous G J. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:1575–1580. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.3.1575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van Kerkhof P, Alves dos Santos C M, Sachse M, Klumperman J, Bu G, Strous G J. Mol Biol Cell. 2001;12:2556–2566. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.8.2556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Govers R, ten Broeke T, van Kerkhof P, Schwartz A L, Strous G J. EMBO J. 1999;18:28–36. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.1.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cunningham B C, Ultsch M, De Vos A M, Mulkerrin M G, Clauser K R, Wells J A. Science. 1991;254:821–825. doi: 10.1126/science.1948064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rowlinson S W, Behncken S N, Rowland J E, Clarkson R W, Strasburger C J, Wu Z, Baumbach W, Waters M J. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:5307–5314. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.9.5307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mellado M, Rodriguez-Frade J M, Kremer L, von Kobbe C, de Ana A M, Merida I, Martinez A C. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:9189–9196. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.14.9189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ross R J, Leung K C, Maamra M, Bennett W, Doyle N, Waters M J, Ho K K. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:1716–1723. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.4.7403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harding P A, Wang X, Okada S, Chen W Y, Wan W, Kopchick J J. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:6708–6712. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.12.6708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van Kerkhof P, Smeets M, Strous G J. Endocrinology. 2002;143:1243–1252. doi: 10.1210/endo.143.4.8755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Livnah O, Stura E A, Middleton S A, Johnson D L, Jolliffe L K, Wilson I A. Science. 1999;283:987–990. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5404.987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Remy I, Wilson I A, Michnick S W. Science. 1999;283:990–993. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5404.990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Constantinescu S N, Keren T, Socolovsky M, Nam H, Henis Y I, Lodish H F. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:4379–4384. doi: 10.1073/pnas.081069198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bu G, Maksymovitch E A, Schwartz A L. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:13002–13009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bu G, Rennke S. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:22218–22224. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.36.22218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kulka R G, Raboy B, Schuster R, Parag H A, Diamond G, Ciechanover A, Marcus M. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:15726–15731. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baumann G, Stolar M W, Amburn K, Barsano C P, DeVries B C. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1986;62:134–141. doi: 10.1210/jcem-62-1-134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Herz J, Hamann U, Rogne S, Myklebost O, Gausepohl H, Stanley K K. EMBO J. 1988;7:4119–4127. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb03306.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Herz J, Strickland D K. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:779–784. doi: 10.1172/JCI13992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li Y, Marzolo M P, van Kerkhof P, Strous G J, Bu G. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:17187–17194. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M000490200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Iadonato S P, Bu G, Maksymovitch E A, Schwartz A L. Biochem J. 1993;296:867–875. doi: 10.1042/bj2960867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Strous G J, Govers R. J Cell Sci. 1999;112:1417–1423. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112.10.1417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moriki T, Maruyama H, Maruyama I N. J Mol Biol. 2001;311:1011–1026. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cosson P, Bonifacino J S. Science. 1992;258:659–662. doi: 10.1126/science.1329208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wells R G, Gilboa L, Sun Y, Liu X, Henis Y I, Lodish H F. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:5716–5722. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.9.5716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Palade G. Science. 1975;189:347–358. doi: 10.1126/science.1096303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen C, Brinkworth R, Waters M J. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:5133–5140. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.8.5133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ross R J, Esposito N, Shen X Y, Von Laue S, Chew S L, Dobson P R, Postel-Vinay M C, Finidori J. Mol Endocrinol. 1997;11:265–273. doi: 10.1210/mend.11.3.9901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mendrola J M, Berger M B, King M C, Lemmon M A. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:4704–4712. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108681200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lemmon M A, Flanagan J M, Hunt J F, Adair B D, Bormann B J, Dempsey C E, Engelman D M. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:7683–7689. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Roswall E C, Mukku V R, Chen A B, Hoff E H, Chu H, McKay P A, Olson K C, Battersby J E, Gehant R L, Meunier A, Garnick R L. Biologicals. 1996;24:25–39. doi: 10.1006/biol.1996.0003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Govers R, van Kerkhof P, Schwartz A L, Strous G J. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:16426–16433. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.26.16426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fuh G, Cunningham B C, Fukunaga R, Nagata S, Goeddel D V, Wells J A. Science. 1992;256:1677–1680. doi: 10.1126/science.256.5064.1677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]