Abstract

G protein coupled inwardly rectifying K+ channels (GIRK/Kir3.x) are mainly activated by a direct interaction with Gβγ subunits, released upon the activation of inhibitory neurotransmitter receptors. Although Gβγ binding domains on all four subunits have been found, the relative contribution of each of these binding sites to channel gating has not yet been defined. It is also not known whether GIRK channels open once all Gβγ sites are occupied, or whether gating is a graded process. We used a tandem tetrameric approach to enable the selective elimination of specific Gβγ binding domains in the tetrameric context. Here, we show that tandem tetramers are fully operational. Tetramers with only one wild-type channel subunit showed receptor-independent high constitutive activity. The presence of two or three wild-type subunits reconstituted receptor activation gradually. Furthermore, a tetramer with no GIRK1 Gβγ binding domain displayed slower kinetics of activation. The slowdown in activation was found to be independent of regulator of G protein signaling or receptor coupling, but this slowdown could be reversed once only one Gβγ binding domain of GIRK1 was added. These results suggest that partial activation can occur under low Gβγ occupancy and that full activation can be accomplished by the interaction with three Gβγ binding subunits.

The G protein-gated K+ channels (GIRK/Kir3.x) play an important role in various physiological actions. They have been extensively studied in the heart and the brain, where they are involved in the control of heart rate upon vagal stimulation (1) and in the generation of neurotransmitter-mediated slow inhibitory postsynaptic potentials (2). The gating of these channels is mainly mediated by the direct interaction of the Gβγ subunits of the G protein (3–5), in concert with other factors such as phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate (6–8) and Na+ ions (refs. 9 and 10; for review see ref. 11).

The functional unit of the GIRK channels is a tetramer, usually composed of GIRK1 and either GIRK2 or GIRK4, in the brain and heart, respectively. The GIRK heterotetramers have been suggested to contain two subunits of each of the two gene products in alternating positions (12–14). A few cases are noted where the functional unit is a homotetramer of either GIRK2 (in the substantia nigra) or GIRK4 (in the atrium) (15, 16).

The molecular elements involved in the binding of Gβγ to the channel and the mechanism of channel activation are not well defined. However, evidence from many laboratories suggests that multiple binding domains, localized to both the N- and C-terminal cytosolic domains, are involved in this action (17–26). Huang et al. (19) identified a Gβγ binding site within amino acids 318–374 of GIRK1, with a downstream region (amino acids 390–462) acting to enhance the binding of the first segment. They identified these regions in GIRK2–GIRK4 as Gβγ binding sites as well. The proximal C-terminal binding site may be responsible for agonist-induced activation but does not affect basal activity when mutated (18), indicating separate regions responsible for basal versus muscarinic receptor-induced activation. A region of the N-terminal domain has also been shown to exhibit Gβγ binding, although with a lower affinity than the C-terminal regions (23). Furthermore, there may be synergistic enhancement between the N- and C-terminal domains of each subunit (19).

Following Gβγ binding, a conformational change, which probably involves a bending or rotation of the second transmembrane domain (TM2), opens the permeation pathway (27, 28). The stoichiometry of binding of Gβγ subunits to each channel has been variously estimated to be between one and four (29–33); however, more recent work involving chemically crosslinked GIRK tetramers and Gβγ subunits demonstrated that the number is probably four (34). Despite the probable existence of four binding sites in the channel tetramer, there is no evidence to suggest whether a complete Gβγ binding “pocket” is made of sites within the same subunit or across subunits (34, 35). Furthermore, little is known about the relative contributions of each of the sites for channel function.

Here, we used a tandem tetrameric approach to investigate the relative contributions of GIRK1 and GIRK4 to channel gating. This approach allowed us to impose constraints on the number of the Gβγ binding domains as well as to examine positional effects. We found that gating of the tetramer by receptor activation can be detected once at least two Gβγ binding domains are present. In addition, the GIRK1 Gβγ binding domain is essential for fast kinetics of activation, a process that does not dependent on receptor coupling mechanisms. We suggest that GIRK channels can fully gate by the binding of three Gβγ subunits but can be partially opened with only one site occupied.

Methods

Tetramer Construction.

Wild-type tetramers were made by tandem linking of GIRK4-GIRK1-GIRK4-GIRK1 [Tet(4-1-4-1)] channel subunits using the following linkers: linker between the first and the second subunit was TGTS(Q)6 with SpeI and AgeI sites; between the second and the third subunits, SAA(Q)7 with a NotI site; and between the third and the fourth subunits, TGTS(Q)6 with SpeI and AgeI sites. Chimeric constructs that contained the core region (TM1 through TM2) of either Ile-86 to Cys-179 of GIRK1 or Phe-93 to Cys-185 of GIRK4 and the N- and C-termini of IRK1, were made using standard PCR techniques. All constructs were verified by sequencing.

Oocyte Expression and Electrophysiology.

Xenopus oocytes were isolated as described (27) and injected with a 50-nl solution containing ≈0.2–5 ng of in vitro transcribed channel cRNA and ≈0.5–1 ng of receptor cRNA. The following receptors were used: muscarinic receptor type 2 (m2R), β2 adrenergic receptor (β2AR), or with the combination of m2R, κ opioid receptor, and metabotropic glutamate receptor type 2 (mGluR2). c-βARK was used at a concentration of ≈0.5–2 ng. cRNA concentration was estimated by formaldehyde gel. All recordings were made 3–6 days after injection.

Macroscopic currents were recorded from oocytes with a two-electrode voltage clamp by using Dagan CA1 amplifier and constant perfusion with 90 mM KCl/2 mM MgCl2/10 mM Hepes (pH 7.4 with KOH), defined as 90K solution, with or without 3 μM carbachol to activate m2R, 1 μM U69593 to activate κ opioid receptor, 30 μM K-glutamate to activate mGluR2, or 1 μM isoproterenol to activate β2AR. A small chamber (4–20 mm) with fast perfusion was used to measure kinetics of activation. Unless otherwise mentioned, all of the measurements were taken at −80 mV. Acquisition hardware and software and analysis programs used were all from Axon Instruments. Single channel recordings were performed as described (27) using 90K solutions for the bath and 90K supplemented with 50 μM GdCl3 in the pipette.

Western blotting was done according to the procedure described by Peleg et al. (36). Tet(4-1-4-1) was detected with an anti-GIRK1 antibody (Upstate Biotechnology, Lake Placid, NY) and a commercially available chemiluminescence kit (Pierce).

All data are presented as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance (P < 0.05) was tested using unpaired t test.

Results

Tandem Tetramers Gate Similarly to Wild-Type Channels.

To examine the relative contribution of each of the Gβγ binding domains to GIRK channel gating, we constructed a tandem tetramer consisting of wild-type GIRK4-GIRK1-GIRK4-GIRK1 subunits [Tet(4-1-4-1)] (Fig. 1B). To establish the validity of using this tetramer further in our study, we needed to confirm that its gating resembles the gating of the wild-type monomeric channel (GIRK1/4). We therefore measured current activation in the presence of 3 μM carbachol. Both GIRK1/4 and Tet(4-1-4-1) showed a large current induction upon receptor stimulation, which was reversible following the removal of the agonist from the external solution (Fig. 1 A and B). For GIRK1/4 and Tet(4-1-4-1), currents increased to 4.8 ± 0.5 and 3.8 ± 0.2 times the basal current levels, respectively, by m2R activation. In addition, the activation kinetics were similar between GIRK1/4 and Tet(4-1-4-1) channels. Half-maximal activation (t1/2) occurred within 0.5 ± 0.05 s for GIRK1/4 and 0.4 ± 0.04 s for Tet(4-1-4-1). On the single channel level, GIRK1/4 or Tet(4-1-4-1) coexpressed with Gβγ showed similar characteristics of fast flickery openings and short bursts (Fig. 1 A and B). We also tested the ability of Tet(4-1-4-1) to select for K+ ions and its rectification properties and found them to be similar to the GIRK1/4 channel (not shown). To verify that Tet(4-1-4-1) is translated in full and is stable in the oocyte membrane, Western blot analysis was performed. Fig. 1B (Inset) shows a specific band of ≈200 kDa in oocytes injected with Tet(4-1-4-1) but not in uninjected oocytes. From the size of this band and its integrity, we conclude that Tet(4-1-4-1) is translated in full and that the channel protein is stable in the oocyte membrane. The results provided above strongly suggest that in all respects, the Tet(4-1-4-1) channel functions in an identical manner to the GIRK1/4 channel when expressed in Xenopus oocytes.

Fig 1.

Tet(4-1-4-1) gates similarly to wild-type channels. (A) Wild-type monomers GIRK1 (gray) and GIRK4 (black) were coexpressed in Xenopus oocytes with m2R. (Left) Continuous recording of current at −80 mV. Oocytes were bathed in 90K solution, followed by application of 3 μM carbachol to activate the channels. Carbachol was washed out with 90K, and then GIRK channels were selectively blocked by the application of 1 mM barium. (Right) Single-channel currents from oocytes injected with GIRK1, GIRK4, and the Gβ1γ2 subunits under the cell-attached configuration. The holding potential was −100 mV. Channel openings are shown as downward deflections. (B) Tet(4-1-4-1) is composed of two subunits of GIRK4 alternating with two subunits of GIRK1. (Left) Currents were recorded in the same manner as in A. (Inset) Western blot for Tet(4-1-4-1) expressed in oocyte membranes shows a band at approximately 200 kDa, corresponding to the estimated size the tetramer. (Right) Single-channel currents from oocytes expressing Tet(4-1-4-1) and the Gβ1γ2 subunits. (C) Tet(0-0-0-0) is composed of GIRK1/IRK1 chimeras, where the N- and C-terminal domains of GIRK1 were replaced with the corresponding IRK domains, and GIRK4/IRK1 with similar substitution, to make a nongating tetramer (see text). Continuous recordings and single-channel currents were recorded as described above, although single-channel activity was recorded in the absence of Gβγ.

The Gβγ Binding Domains Impose Channel Closure.

Having established the validity of our tetrameric approach, we continued by constructing Tet(0-0-0-0), in which the cytoplasmic domains of GIRK1 and GIRK4 in Tet(4-1-4-1) were replaced by those of IRK1(Kir2.1), an inward rectifier that does not gate in response to Gβγ. Whereas Tet(4-1-4-1) consists of alternating subunits of GIRK4 and GIRK1, the designation Tet(0-0-0-0) indicates that each of the four subunits contains both the N- and C-terminal cytosolic domains of IRK1 (denoted as 0). In Tet(0-0-0-0) and in all tetrameric constructs made thereafter, the transmembrane and pore regions of the corresponding GIRK subunits were left intact because (i) the assembly of functional tetramers is mediated through these areas, and members of the IRK family do not assemble with those of the GIRK (13, 37), and (ii) we wanted to conserve the gates that are responsible for coupling the Gβγ-dependent gating with pore opening (27, 28). Although the cytoplasmic regions also contain residues known to be important for interaction with PIP2 and Na+ ions (6–10), we have chosen to limit our investigation to the effects of Gβγ.

In contrast to Tet(4-1-4-1), Tet(0-0-0-0) channel was no longer able to be gated by m2R stimulation (Fig. 1C), displaying high constitutive activity which was Gβγ-independent, as determined by its insensitivity to the Gβγ chelator, c-βARK (not shown) (36). Furthermore, Tet(0-0-0-0) maintained GIRK-like single channel characteristics (27), with fast openings and bursting activity, as expected when the core region of the channel is preserved (22). The Gβγ-independent high constitutive activity, and the lack of responsiveness of Tet(0-0-0-0) to receptor stimulation, suggest that Tet(0-0-0-0) is unable to close in the absence of receptor stimulation and therefore can be viewed as having all of its activation gates open. This implies that, in GIRK channels, the presence of the Gβγ-binding domains maintains the channel in its closed conformation, in the absence of receptor stimulation.

Taking into account the information presented above, specifically the inability of Tet(0-0-0-0) to close, we were interested in determining the minimal required Gβγ binding domains that are able to close the channel, or alternatively, the minimal required components that enable channel gating by receptor stimulation. We therefore constructed new chimeras, systematically replacing both the N- and C-cytosolic domains of each channel subunit in the wild-type tetramer and in different combinations. Fig. 2 shows a schematic representation of the chimeras made and the relative efficiency by which they are activated by m2R stimulation. It is immediately apparent that the ability of m2R activation to gate the channel strongly depends on the relative amounts of Gβγ binding domains present (for simplicity, the Gβγ binding domain is defined here as consisting of both the N- and C-cytosolic domains of the same channel subunit). Interestingly, tetramers containing either one GIRK1 [Tet(0-1-0-0)] or one GIRK4 subunit [Tet(0-0-4-0)] did not respond to receptor stimulation, with 1.06 ± 0.01 and 1.06 ± 0.01-fold induction by m2R stimulation, respectively. In contrast to these channels, tetramers with two Gβγ binding domains, Tet(0-1-4-0), Tet(0-0-4-1), Tet(4-0-4-0), and Tet(0-1-0-1), were already able to close, judging by their ability to open by m2R stimulation, with 1.28 ± 0.03, 1.48 ± 0.05, 1.60 ± 0.08, and 1.32 ± 0.03-fold induction by receptor stimulation, respectively. Having three Gβγ binding domains, as seen with Tet(4-1-4-0) and Tet(0-1-4-1), also increased the ability of the channels to close, but to a lesser extent than the wild-type Tet(4-1-4-1) channel. Tet(4-1-4-0) displayed 2.0 ± 0.1-fold and Tet(0-1-4-1) displayed 1.5 ± 0.1-fold induction by receptor stimulation. These results suggest that under conditions where only one or two of the channel subunits are constitutively active, the channel displays partial activation in the absence of receptor stimulation (see Fig. 2 Inset). In addition, the unequal contribution of the different Gβγ-domain stoichiometries to channel activation may suggest that there is intersubunit cooperativity in gating the channel.

Fig 2.

A graded response of tetramers upon induction by carbachol. Currents at −80 mV were recorded in 90K solution with and without 3 μM carbachol. The average of the basal currents for each tetramer (three to five batches of oocytes, n > 6 per batch) was arbitrarily set at 100% (white bars), and the amount of agonist-induced increase in current upon the addition of 3 μM carbachol was determined (black bars). (Inset) Tetramers were grouped according to the number of constitutively active subunits they contain; Tet(4-1-4-1) contains none, Tet(4-1-4-0) and Tet(0-1-4-1) contain one, Tet(0-1-4-0), Tet(0-0-4-1), Tet(4-1-0-0), Tet(4-0-4-0), and Tet(0-1-0-1) contain two, Tet(0-1-0-0) and Tet(0-0-4-0) contain three, and Tet(0-0-0-0) contains four. The ability to gate was defined as the fold current increase above basal activity in tetramers containing specific number of constitutively active subunits, divided by the fold-induction of Tet(4-1-4-1) and expressed as a percentage.

As a control for the proper assembly of the tetramers, we constructed a dimer, Dim(4-0). Dim(4-0) was expected to couple to itself to form a functional channel identical to Tet(4-0-4-0). Dim(4-0) did indeed show similar gating characteristics to Tet(4-0-4-0), with 1.3 ± 0.1-fold, compared with 1.5 ± 0.1-fold induction (not shown). As a further control, we also constructed Tet(4-1-0-0), which, when expressed in oocytes, should fold into the same channel as the previously mentioned Tet(0-0-4-1). Tet(0-0-4-1) and Tet(4-1-0-0) displayed carbachol induction of 1.4 ± 0.1 and 1.3 ± 0.1-fold, respectively. These results confirm that a functional channel unit is mainly made of one tetramer subunit.

The Gβγ Binding Domain of GIRK1 Plays a Role in Gating Kinetics.

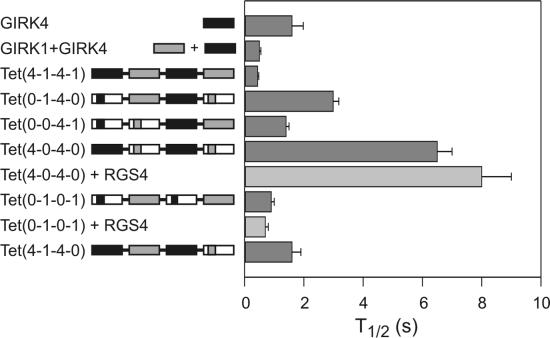

In addition to the varying extents of channel closings seen in the tetramers described above, we have also observed differences in gating kinetics. A summary of the activation kinetics, t1/2, is given in Fig. 3. It is apparent that Tet(4-0-4-0), a tetramer containing two Gβγ binding domains, both of the GIRK4 type, is the slowest to activate. This is in sharp contrast to Tet(0-1-0-1), which contains two similar Gβγ binding domains, but both of the GIRK1 type. Tet(4-0-4-0) is about seven times slower to activate than Tet(0-1-0-1), with t1/2 of 6.5 ± 0.5 s compared with 0.9 ± 0.1 s, respectively. This difference was significantly reduced once both the N- and C-cytosolic domains of one GIRK1 subunit were added to Tet(4-0-4-0) to make Tet(4-1-4-0), with t1/2 of 1.6 ± 0.3 s. This suggests that GIRK1 cytosolic domains are major determinants for fast activation kinetics and that one subunit is sufficient for this action.

Fig 3.

Kinetics of activation of the various tetramers. Half-maximal time for activation (t1/2) was calculated by determining the time it takes for currents to reach half the maximum of activated currents (difference between induced and basal levels). Holding potential was −80 mV. Light gray bars denote measurements from oocytes that also coexpress RGS4. Data were averaged over one to three batches of oocytes.

Regulators of G protein signaling (RGS) have been shown to affect activation and deactivation kinetics of GIRK channels, mainly because of the acceleration of GDP–GTP exchange of the Gα subunit and acceleration of Gα GTPase hydrolysis rate (38–42). We wanted to determine whether the slow activation kinetics in Tet(4-0-4-0) could be accelerated with RGS protein, as seen in the wild-type channel. We therefore coexpressed Tet(4-0-4-0) or Tet(0-1-0-1) and m2R with or without RGS4 and measured the activation kinetics. The activation kinetics of Tet(4-0-4-0) were unaffected by coexpressing RGS4 and were slightly speeded for Tet(0-1-0-1) (Fig. 3). This suggests that the slow activation kinetics of Tet(4-0-4-0) are not due to an effect that depends on nucleotide exchange mechanism of the Gα subunit.

It has been shown previously that Gα subunits interact with the GIRK channel cytosolic domains, and thus it was proposed that GIRK channels may exist in complexes that include receptors and G proteins to enhance efficient channel activation (22, 23). To test whether the effects seen with Tet(4-0-4-0) are the result of impaired interaction with G protein-coupled receptors and/or different Gα subunits, we coexpressed Tet(4-0-4-0) or Tet(4-1-4-1) with three types of Gi/o protein-coupled receptors, m2R, κ opioid, and mGluR2, in the same oocytes, and compared the activation kinetics following specific receptor stimulation. In addition, we coexpressed the same tetramers with β2AR and Gαs (43) as an example of a Gs linked receptor. For all receptors tested, Tet(4-0-4-0) showed slower activation kinetics compared with Tet(4-1-4-1) (Fig. 4). These results suggest that slow activation kinetics seen in Tet(4-0-4-0) may not be due to impaired interaction with a specific receptor and/or G protein type but rather be due to intrinsic properties within the channel molecule. The addition of even one set of GIRK1 cytosolic domains can speed this slow intrinsic property, as seen in Tet(4-1-4-0).

Fig 4.

Slow activation of Tet(4-0-4-0) is independent of G protein or receptor type. Tet(4-0-4-0) or Tet(4-1-4-1) were coexpressed in the same oocytes with all three Gi/o-coupled receptors: m2R, mGluR2, and κ opioid. The agonists used were carbachol, K-glutamate, and U69593, respectively. Separately, Tet(4-0-4-0) or Tet(4-1-4-1) was coexpressed with β2AR and Gαs, and currents were induced with isoproterenol at a holding potential of −80 mV. t1/2 was determined as described in the Fig. 3 legend.

Discussion

In this work, we were able to investigate the relative contribution of various GIRK channel Gβγ binding domains to receptor-mediated activation and to activation gating kinetics, using a tandem tetramer-based approach. By examining the ability of receptor stimulation to activate various tetramers containing Gβγ binding domains in different stoichiometries, we show that tetramers containing none or one Gβγ binding domains are insensitive to receptor-mediated activation and display constitutive activity. The addition of two or three Gβγ binding elements is sufficient to close the channel and hence to display receptor-mediated activation, although not as tight as is seen with four wild-type subunits. These results point toward a specific stoichiometry of Gβγ subunits for the activation of GIRK channels. Moreover, full closing of the channel is permissible only when all subunits in the tetramer are able to gate in response to the binding of Gβγ. Furthermore, we were able to demonstrate that channel activation kinetics are mainly controlled by the GIRK1-associated Gβγ binding domain, independent of the receptor type involved in this action. The relevance of these findings to channel gating and activation kinetics is discussed below.

How can we view the Gβγ binding domains as regulators of channel gating? We found that a tetramer that does not contain Gβγ binding domains, Tet(0-0-0-0), is unable to close, or alternatively, gate by receptor stimulation. Because the gating transduction machineries, located within the TM1 through TM2 region of the channel, were not removed in this tetramer, we can suggest that the Gβγ binding domains are not only important in the detection and transduction of signals to the core region to open the channel by bending the TM2 domain (27), but also to maintain this core gating machinery in its closed inactive state. Following this logic, tetramers that contain only one Gβγ binding domain [Tet(0-1-0-0) or Tet(0-0-4-0)], either of the GIRK1 or the GIRK4 type, can be viewed as channels with three constitutively open gates and one regulated closed gate.

By selectively adding and positioning the constitutively active domains within the tetramers, we were able to uncover the graded nature of the response to Gβγ binding. Gated channel activity of about 30% of the wild type was detected by the incorporation of one constitutively active subunit into the tetramer and decreased to about 15% once two constitutive subunits were incorporated. Interestingly, tetramers containing three constitutively active domains did not respond to receptor stimulation, suggesting that full gating of the GIRK channels can be achieved by the binding of only three Gβγ subunits (Fig. 2 Inset). The ability of only three gating subunits to fully open the channel may be suggestive of the possibility that the full open conformation can be the result of positive cooperativity between the Gβγ-activated subunits in opening of the channel. Conceptually similar graded activation behavior has been described in cyclic nucleotide gated channels, where three subconducting levels were observed due to the selective binding of cGMP to two, three, or four sites within the channel, accompanied by a gradual increase in opening probability (44). In the case of the GIRK channel, we propose that the gradual increase in channel opening is mainly due to an increase in the channel's open probability. This has been seen in recordings from single GIRK channels not stimulated by Gβγ, where the channel opens to full conductance with only apparent changes in channel mean open time and open probability (27). These results suggest that channel gating does not occur in an all-or-none fashion, and thus can be tuned according to the strength of receptor stimulation.

What is the contribution of intersubunit interaction to Gβγ-induced activation? Tetramers containing only two Gβγ binding domains activate by receptor stimulation to a similar extent, regardless of the relative locations of the Gβγ binding domains, suggesting that intersubunit cooperation between the Gβγ binding domains is not essential to control channel gating. These results suggest that the Gβγ binding domains, the N-and C- cytoplasmic regions within a subunit, form a functional unit responsible for keeping the core-associated gate closed in the absence of Gβγ binding.

In contrast to the various gating efficiencies seen with the constructed tetramers, we observed no major effect of the subunit composition on channel gating kinetics; the activation time course of most of the tetramers was within a margin that can be accounted for by the expression levels seen with the different tetramers (t1/2 from 0.5 to ≈2 s) and is comparable to what has been seen in native tissues (45–48), with the exception of Tet(4-0-4-0). The time course of activation of Tet(4-0-4-0) was 15 times slower than the wild-type Tet(4-1-4-1). Slow activation has been previously seen by Slesinger et al. (22) when measuring the gating kinetics of IRK1/GIRK1 chimeras that did not contain the N-terminal domain of GIRK1. It was then suggested that the GIRK1 N-terminal cytosolic domain may couple the receptor and the inactive G protein trimer to provide an efficient coupling during activation (22, 23). Indeed, when one set of GIRK1 Gβγ binding domains was added to Tet(4-0-4-0) to make Tet(4-1-4-0), the activation time course returned to within wild-type levels. Thus, this suggests that only one subunit of GIRK1 is required for fast activation gating.

Might disruption of receptor- and/or G protein-channel coupling with the cytosolic domains in Tet(4-0-4-0) be the reason for slow gating? We addressed this issue by using two strategies. We first expressed three different Gαi/o-coupled receptors, belonging to three different families, with the idea that if a receptor-specific interaction is the cause for slow activation gating of Tet(4-0-4-0), it should not be seen with different receptor types. Our results demonstrate that slow activation gating is independent of receptor type and thus exclude the possibility of a receptor-specific mechanism. In addition, if slow activation was due to impaired Gαi/o interaction with the channel, the activation time course by Gαs-coupled receptor should not be slower in Tet(4-0-4-0) compared with the wild-type tetramer. Our results show that the time course of activation of Tet(4-0-4-0) by β2AR, which is coupled to Gαs, is still slower than the activation of the wild-type tetramer, as seen with the different receptor types. Therefore, the slower activation time course may not be due to impaired coupling with the inactive Gαi/oβγ trimer (23). Because the effects of RGS proteins oppose those seen with Tet(4-0-4-0), it may be possible that the slower activation kinetics are because of impaired interaction of Gα-RGS with the channel (49, 50). Our results show that coexpression of RGS4 did not accelerate the activation time course of Tet(4-0-4-0). This may suggest that the slow activation kinetics are not the result of differences in the rates of GDP–GTP exchange on the Gα subunit upon receptor stimulation, a mechanism responsible for the acceleration of channel activation (41). Why then do homotetramers of GIRK4, which do not contain any GIRK1 elements, have fast activation gating? It was recently shown that two critical residues in the N and the C termini of both GIRK1 and GIRK4 contribute to Gβγ-mediated activation and binding to the channels (24). However, the mutations of the same corresponding residues in GIRK1 and GIRK4 displayed different degrees of signal attenuation, with a complete attenuation in GIRK4 and partial attenuation with GIRK1. This suggests that GIRK1 and GIRK4 N and C termini have slightly different abilities to interact with Gβγ. Therefore, it may indeed be that slow gating in Tet(4-0-4-0) is because of intrinsic factors related to the efficiency of or transduction by Gβγ to open the channel.

This report demonstrates the relative contribution of the Gβγ binding domains to GIRK channel gating, their position as well as their role in controlling activation kinetics. It seems that three Gβγ subunits are sufficient to fully gate the channel; however, channel activation is already apparent when only one subunit is gated. This may be of importance for the ability of small submaximal inhibitory synaptic activity to fine-tune cellular excitability.

Acknowledgments

We thank I. Riven and S. Iwanir for reading earlier versions of the manuscript, R. Meller, E. Shalgi, and E. Wolff for excellent technical assistance, Dr. L. Y. Jan for her initial support, Dr. B. Conclin for the κ opioid receptor, Dr. H. A. Lester for the m2 receptor, and Dr. S. Nakanishi for the mGluR2 receptor. This work was supported in part by Israeli Academy of Sciences Grant 633/01 and a grant from the Minerva Stiftung Foundation (Munich) (to E.R.).

Abbreviations

GIRK, G protein-coupled K+ channels

TM, transmembrane

RGS, regulator of G protein signaling

References

- 1.Wickman K., Nemec, J., Gendler, S. J. & Clapham, D. E. (1998) Neuron 20, 103-114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Luscher C., Jan, L. Y., Stoffel, M., Malenka, R. C. & Nicoll, R. A. (1997) Neuron 19, 687-695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reuveny E., Slesinger, P. A., Inglese, J., Morales, J. M., Iniguez-Lluhi, J. A., Lefkowitz, R. J., Bourne, H. R., Jan, Y. N. & Jan, L. Y. (1994) Nature (London) 370, 143-146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wickman K. D., Iniguez-Lluhl, J. A., Davenport, P. A., Taussig, R., Krapivinsky, G. B., Linder, M. E., Gilman, A. G. & Clapham, D. E. (1994) Nature (London) 368, 255-257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Logothetis D. E., Kurachi, Y., Galper, J., Neer, E. J. & Clapham, D. E. (1987) Nature (London) 325, 321-326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Logothetis D. E. & Zhang, H. (1999) J. Physiol. 520, 630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huang C. L., Feng, S. & Hilgemann, D. W. (1998) Nature (London) 391, 803-806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sui J. L., Petit-Jacques, J. & Logothetis, D. E. (1998) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95, 1307-1312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sui J. L., Chan, K. W. & Logothetis, D. E. (1996) J. Gen. Physiol. 108, 381-391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Petit-Jacques J., Sui, J. L. & Logothetis, D. E. (1999) J. Gen. Physiol. 114, 673-684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mark M. D. & Herlitze, S. (2000) Eur. J. Biochem. 267, 5830-5836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Silverman S. K., Lester, H. A. & Dougherty, D. A. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271, 30524-30528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tucker S. J., Pessia, M. & Adelman, J. P. (1996) Am. J. Physiol. 271, H379-H385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Corey S., Krapivinsky, G., Krapivinsky, L. & Clapham, D. E. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 5271-5278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Inanobe A., Yoshimoto, Y., Horio, Y., Morishige, K. I., Hibino, H., Matsumoto, S., Tokunaga, Y., Maeda, T., Hata, Y., Takai, Y. & Kurachi, Y. (1999) J. Neurosci. 19, 1006-1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Corey S. & Clapham, D. E. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 27499-27504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Krapivinsky G., Kennedy, M. E., Nemec, J., Medina, I., Krapivinsky, L. & Clapham, D. E. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 16946-16952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.He C., Zhang, H., Mirshahi, T. & Logothetis, D. E. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 12517-12524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huang C. L., Jan, Y. N. & Jan, L. Y. (1997) FEBS Lett. 405, 291-298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kunkel M. T. & Peralta, E. G. (1995) Cell 83, 443-449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Inanobe A., Morishige, K. I., Takahashi, N., Ito, H., Yamada, M., Takumi, T., Nishina, H., Takahashi, K., Kanaho, Y., Katada, T., et al. (1995) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 212, 1022-1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Slesinger P. A., Reuveny, E., Jan, Y. N. & Jan, L. Y. (1995) Neuron 15, 1145-1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huang C. L., Slesinger, P. A., Casey, P. J., Jan, Y. N. & Jan, L. Y. (1995) Neuron 15, 1133-1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.He C., Yan, X., Zhang, H., Mirshahi, T., Jin, T., Huang, A. & Logothetis, D. E. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 6088-6096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yan K. & Gautam, N. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271, 17597-17600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Takao K., Yoshii, M., Kanda, A., Kokubun, S. & Nukada, T. (1994) Neuron 13, 747-755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sadja R., Smadja, K., Alagem, N. & Reuveny, E. (2001) Neuron 29, 669-680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yi B. A., Lin, Y. F., Jan, Y. N. & Jan, L. Y. (2001) Neuron 29, 657-667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Krapivinsky G., Krapivinsky, L., Wickman, K. & Clapham, D. E. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270, 29059-29062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ito H., Sugimoto, T., Kobayashi, I., Takahashi, K., Katada, T., Ui, M. & Kurachi, Y. (1991) J. Gen. Physiol. 98, 517-533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kurachi Y., Ito, H. & Sugimoto, T. (1990) Pflugers Arch. 416, 216-218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kurachi Y., Tung, R. T., Ito, H. & Nakajima, T. (1992) Prog. Neurobiol. 39, 229-246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ito H., Tung, R. T., Sugimoto, T., Kobayashi, I., Takahashi, K., Katada, T., Ui, M. & Kurachi, Y. (1992) J. Gen. Physiol. 99, 961-983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Corey S. & Clapham, D. E. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 11409-11413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dascal N. (2001) Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 12, 391-398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Peleg S., Varon, D., Ivanina, T., Dessauer, C. W. & Dascal, N. (2002) Neuron 33, 87-99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tinker A., Jan, Y. N. & Jan, L. Y. (1996) Cell 87, 857-868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Doupnik C., Davidson, N., Lester, H. & Kofuji, P. (1997) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94, 10461-10466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Saitoh O., Kubo, Y., Miyatani, Y., Asano, T. & Nakata, H. (1997) Nature (London) 390, 525-529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bunemann M. & Hosey, M. M. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 31186-31190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chuang H. H., Yu, M., Jan, Y. N. & Jan, L. Y. (1998) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95, 11727-11732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Saitoh O., Kubo, Y., Odagiri, M., Ichikawa, M., Yamagata, K. & Sekine, T. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 9899-9904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lim N. F., Dascal, N., Labarca, C., Davidson, N. & Lester, H. A. (1995) J. Gen. Physiol. 105, 421-439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ruiz M. L. & Karpen, J. W. (1997) Nature (London) 389, 389-392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sodickson D. L. & Bean, B. P. (1996) J. Neurosci. 16, 6374-6385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Surprenant A. & North, R. A. (1988) Proc. R. Soc. London B Biol. Sci. 234, 85-114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Inomata N., Ishihara, T. & Akaike, N. (1989) Am. J. Physiol. 257, C646-C650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Breitwieser G. E. & Szabo, G. (1988) J. Gen. Physiol. 91, 469-493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Inanobe A., Fujita, S., Makino, Y., Matsushita, K., Ishii, M., Chachin, M. & Kurachi, Y. (2001) J. Physiol. 535, 133-143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fujita S., Inanobe, A., Chachin, M., Aizawa, Y. & Kurachi, Y. (2000) J. Physiol. 526, 341-347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]