Abstract

Though open chromatin may promote active transcription, gene expression responses may not be directly coordinated with changes in chromatin accessibility. Most existing methods for single-cell multi-omics data focus only on learning stationary, shared information among these modalities, overlooking modality-specific information delineating cellular states and dynamics resulting from causal relations among modalities. To address this, the epigenome-transcriptome relationship can be characterized in relation to time as coupled (changing dependently) or decoupled (changing independently). We propose the framework HALO, adopting a causal approach to model these temporal causal relations on two levels. On the representation level, HALO factorizes these two modalities into both coupled and decoupled latent representations, revealing their dynamic interplay. On the individual gene level, HALO matches gene-peak pairs and characterizes their changes over time. HALO discovers analogous biological functions between modalities, distinguishes epigenetic factors for lineage specification, and identifies temporal cis-regulation interactions relevant to cellular differentiation and human diseases.

Subject terms: Machine learning, Computational models, Software, Gene regulatory networks

Chromatin accessibility dynamics causally influence changes in gene expression levels, but these fluctuations may not be directly coupled over time. Here, authors develop computational causal framework HALO, examining epigenetic plasticity and gene regulation dynamics in single-cell multi-omic data.

Introduction

Single-cell multi-omics technologies have revolutionized our understanding of cellular heterogeneity and complexity, enabling the simultaneous measurement of diverse molecular layers such as transcriptomics, epigenomics, and proteomics within individual cells. These technologies provide a unique opportunity to dissect the regulatory relationships underlying cellular functions and phenotypes1. However, integration and analysis of such heterogeneous data types remain challenging, for example, in distinguishing the effects of chromatin accessibility on expression across varying cellular states and over time. To address these challenges, we developed HALO, a computational framework designed to model the causal relationships within single-cell co-profiled multi-omic data. The key hypothesis of HALO is that changes in chromatin accessibility causally influence gene expression. By leveraging measurements of transcriptomics and chromatin accessibility data from single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) and single-cell ATAC sequencing (scATAC-seq), HALO enables a comprehensive analysis of the causal interactions that dictate cell state, function, and regulatory mechanisms.

Chromatin structure plays a crucial role in regulating the ability of transcriptional machinery to access DNA and activate gene expression2. Open chromatin facilitates the binding of transcription factors, the recruitment of RNA polymerases, and the initiation of transcription. Consequently, gene expression and chromatin accessibility often correlate and exhibit similar dynamics across different cellular states or over time3. However, they do not always display the same patterns due to various biological regulatory factors4,5. For example, chromatin can be accessible, but the associated gene or regulatory region may not be immediately transcribed—a state known as chromatin priming6. This primed state allows cells to respond more quickly to environmental changes or developmental signals. In this state, cells have the potential to differentiate into various cell types and adapt to different conditions7,8. Additionally, gene expression can be controlled post-transcriptionally through mechanisms such as mRNA stability, degradation, or translation efficiency9. Meanwhile, active chromatin remodeling may occur independently of transcriptional changes, preparing the chromatin landscape for future gene activation or repression10. Previous representation learning methods for single-cell multi-omics data implicitly rely on the strict biological assumption that chromatin accessibility and active transcription are synchronized11–14, though some recent methods consider the case where chromatin opening precedes transcription initiation10,15. In contrast to these works, HALO decomposes the relations between chromatin accessibility and gene expression into coupled and decoupled cases. In the coupled case, chromatin accessibility and gene expression exhibit correlated changes over time, while in the decoupled case, they change independently over time. Due to the high dimensionality and sparsity of single-cell genomics data, HALO operates on two levels of analysis: the low-dimensional latent representation level and the individual gene level, incorporating real-time points/estimated latent time to account for temporal dynamics in cellular development. The framework is equipped with an interpretable neural network to provide biological meaning to the latent representations. Moreover, HALO employs Granger causality to assess context-specific distal cis-regulation in cases where, despite associated chromatin regions becoming more accessible, gene transcription does not increase correspondingly15. We observe that these situations frequently occur when the chromatin regions overlap with super enhancer regions.

Results

HALO: a causal machine learning framework to model the interactions between chromatin accessibility and gene expression

HALO models the co-assayed gene expression and chromatin accessibility in a low-dimensional latent space as well as on the level of individual genes and their linked peaks (open chromatin regions) through a causal lens. In our study, we establish a framework to analyze the causal relationships between jointly profiled scRNA-seq and scATAC-seq data, incorporating temporal information. We hypothesize that scATAC-seq data, which is indicative of chromatin accessibility, causally precedes scRNA-seq data due to open chromatin regions influencing gene transcription. Specifically, we distinguish between two types of causal interactions: (1) In the coupled case, gene expression and chromatin accessibility exhibit dependent changes over time, indicating they are influenced by shared unknown confounders. (2) In the decoupled case, certain gene expressions and their local peak patterns change independently over time, suggesting the presence of distinct, unknown causal factors affecting gene expressions and accessibilities. This approach extends the concept of time-lagging observed in previous studies4,10 to a broader framework, encompassing mechanisms that change independently or dependently over time; for example, chromatin open regions may become more accessible while gene expression level remains stable. This approach aims to elucidate causal relationships between gene expression and chromatin accessibility at both the levels of representations and individual genes, as depicted in Fig. 1A.

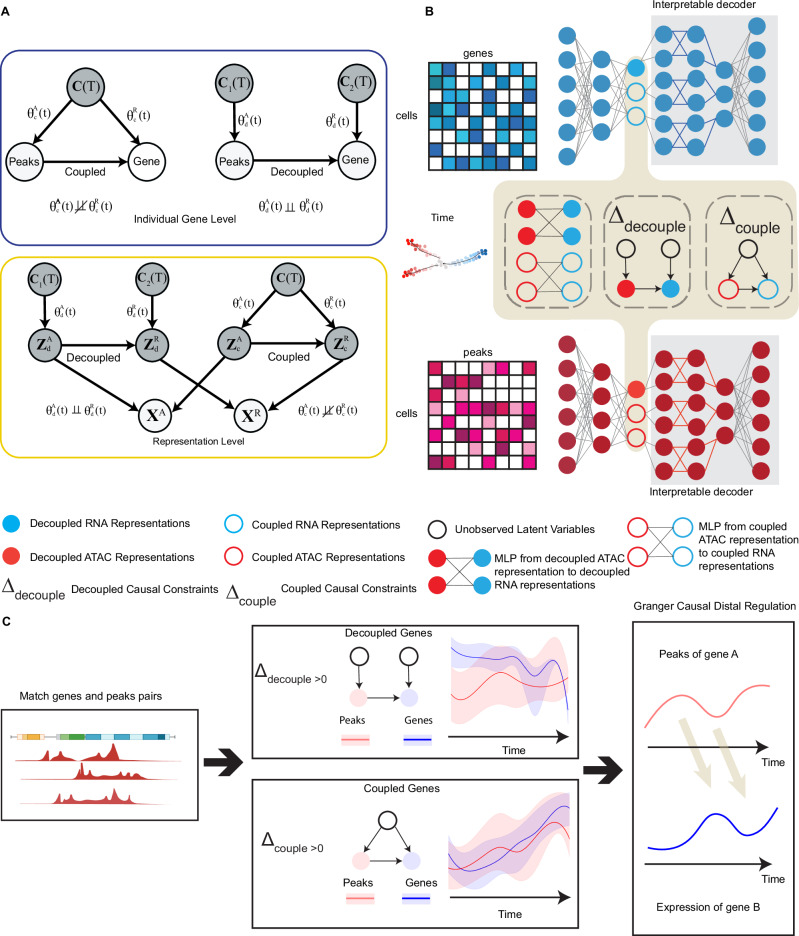

Fig. 1. The main framework of HALO.

A Top: The causal diagram of individual gene expression and its corresponding peaks, in both coupled (left) and decoupled (right) cases. Bottom: the causal diagram of relations between scRNA-seq and scATAC-seq data on the representation level, for decoupled (left) and coupled (right) cases. θ are functional parameters as a function of time for RNA (R) or ATAC (A) data, as well as coupled (c) or decoupled (d). B Architecture for representation learning within a causal regularized variational autoencoder (VAE) framework. From the jointly profiled scRNA-seq (blue) and scATAC-seq (red) data, latent representations are learned and can then be used via interpretable decoder to determine important genes and peaks. For the ATAC modality, the latent ZA is divided into , representing the decoupled and coupled latent representations, respectively. Similarly, the RNA modality’s latent representations comprise (decoupled) and (coupled). The decoupled representations and adhere to the decoupled causal constraints Δdecouple, whereas the coupled representations, conform to the coupled causal constraints Δcouple. C Illustration of the gene-peak level analysis process. Initially, genes and ATAC peaks within specified proximities are matched using non-negative binomial regression, linking gene expression to neighboring ATAC peaks. Subsequently, we compute decouple and couple scores to categorize gene-peaks as either decoupled or coupled. Finally, we employ the Granger causality test to identify distal regulatory relationships between peaks and genes, uncovering potential mechanisms of genetic regulation. Created with elements from BioRender, Jia, M. (2025) https://BioRender.com/jcqqg5n.

On the representation level, we model the lower-dimensional latent space interactions between ATAC and RNA modalities from a causal perspective. Specifically, HALO learns the representations that contain the coupled information between scATAC-seq and scRNA-seq data as well as the independent decoupled information, such that the causal relations are preserved even across time (Fig. 1B). Coupled representations encapsulate information where gene expression changes are dependent on chromatin accessibility dynamics over time, reflecting shared information across modalities. In contrast, decoupled representations extract information where gene expression changes independently of chromatin accessibility over time, emphasizing modality-specific information. The latent representations of scATAC-seq data can be decomposed to . The latent representations of scRNA-seq data ZR may be similarly decomposed: . and represent the decoupled latent representations derived from scATAC-seq and scRNA-seq data, while and denote the coupled latent representations for scATAC-seq and scRNA-seq data, respectively. These representations capture distinct aspects of information from the two modalities, each varying over time or along a latent temporal variable. Figure 1B illustrates the underlying causal relationship, wherein causes , and causes. However, and are influenced by independent causative factors, which are temporally related. Thus despite their causal linkage, and have independent causal factors, leading to independent temporal changes. In contrast to the decoupled representations, both and are influenced by common latent confounders, which also vary with time. This indicates that the changes in and are synchronized over time, reflecting their shared temporal dynamics.

To ensure the delineation of these relationships, HALO utilizes paired scRNA-seq and scATAC-seq data as its input. We employ two distinct encoders to derive the latent representations ZA and ZR. Moreover, we have formulated specific decoupled and coupled causal constraints (See “Methods” “Causal constraints of the latent representations”). A Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) is used to model the concept that causes , while a decoupled constraint enforces the independent functional relations between them. Similarly, another MLP is used to align the coupled representations to , but with a coupled constraint (See ”Methods” Section “Generative models”). Additionally, we developed a nonlinear interpretable decoder (Fig. 1B) that allows us to interpret the latent representations by decomposing the reconstruction of genes or peaks into additive contributions from individual representations (See Supplementary Methods C).

At the individual gene level, our approach begins with the use of denoised gene expressions and peaks (Fig. 1C), applying negative binomial regression to correlate local peaks with gene expression. This method allows us to match local peaks to corresponding gene expression, enabling the subsequent calculation of decouple and couple scores at the individual gene level. Specifically, the decouple score quantifies the independence of gene expression level changes in relation to local peaks over time. Conversely, the couple score evaluates the extent to which gene expression changes are dependent on local peaks throughout the time course (See “Methods” Section “Genomic matching score”). Finally, through the application of Granger causality analysis, we explore the underlying mechanisms of distal peak-gene regulatory interactions. This analytical approach allows us to elucidate instances where local peaks increase, yet corresponding gene expression remains largely unchanged.

In summary, HALO offers several key contributions to the field of multi-omics analysis, which we enumerate as follows: (1) HALO learns latent representations that are causally informed, enhancing our understanding of the interactions across different omics modalities. (2) HALO ensures that these latent representations are interpretable. (3) HALO causally characterizes the relations between gene expression and associated chromatin regions over time, unlocking insights about regulatory dynamics. (4) HALO identifies distal cis-regulation interactions between chromatin regions and nearby genes, specifically for chromatin regions overlapping with super enhancers.

HALO effectively separates coupled and decoupled representations, enhancing the analysis and interpretation of modality-shared and modality-specific information in mouse skin hair follicle data

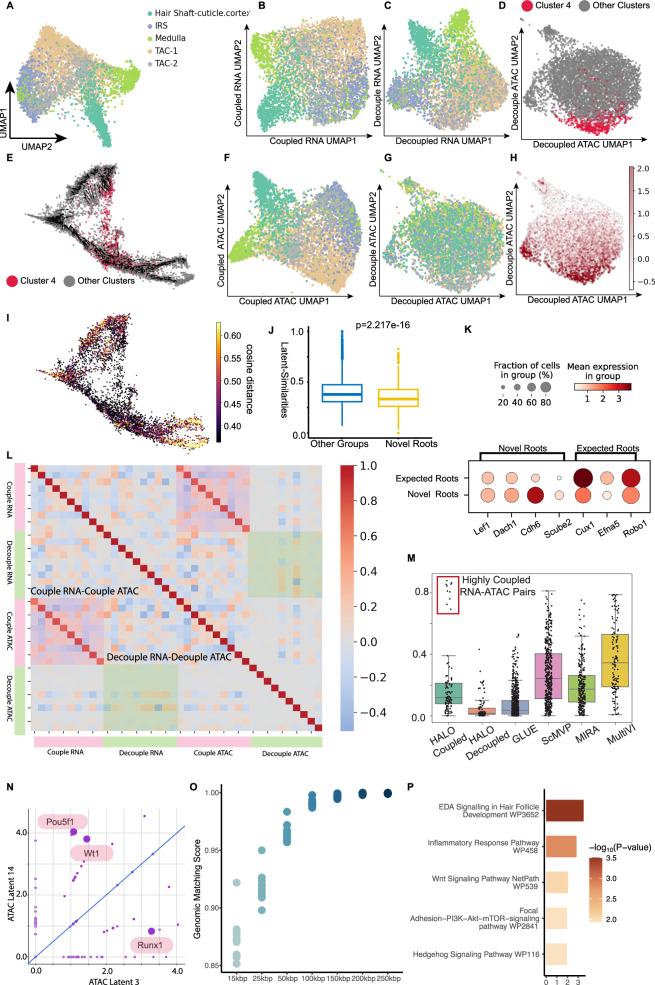

Through the integration of information from both ATAC-seq and RNA-seq modalities, HALO is able to discern cell types and capture latent temporal dynamics. The ATAC and RNA representations from HALO are concatenated and visualized according to cell type (Fig. 2A and Supplementary Figs. 1A and 2) and latent time (Supplementary Fig. 1C). Figure 2B and F display the UMAP projections constructed by the coupled RNA and ATAC representations, and , respectively. In accordance with the concept of coupled representations, and capture analogous information across the two modalities, which is reflected in the resemblance between their UMAP visualizations. However, the decoupled representations and convey different information. In particular, retains cell type information, while does not (Fig. 2C and G).

Fig. 2. The representation-level results of the SHARE-seq mouse skin hair follicle dataset.

The decoupled representations contain the chromatin potential information in the latent space. A The UMAP constructed from concatenated RNA and ATAC representations, colored by cell type. B The UMAP constructed from RNA coupled representations, colored by cell type. C The UMAP of RNA decoupled representations, colored by cell type. D The UMAP constructed from ATAC decoupled representations, colored by cluster membership (cluster 4 and the rest of the clusters). E The distribution of cluster 4 and other clusters, along with chromatin potential vector field, shown on previously published UMAP 4,75. F The UMAP constructed from ATAC coupled representations, colored by cell type. G The UMAP constructed from ATAC decoupled representations, colored by cell type. H The UMAP constructed from ATAC decoupled representations, colored by the value of ATAC decoupled latent representation 14, which mainly characterizes cluster 4 (see D). I The original UMAP of SHARE-seq data4, colored by the cosine distance between decoupled RNA and decoupled ATAC representations. J The cosine similarity between decoupled RNA and decoupled ATAC representations of cluster 4 (novel root) and rest of the cells. The boxplot shows the median (center line), interquartile range (box), and data within 1.5 × IQR from the quartiles (whiskers); points outside this range are plotted as outliers. The p-values are calculated using Welch’s two-sided t-test. K Expression levels of marker genes in the novel root and expected roots. L The Pearson’s correlations matrix of latent representations. Note the strong one-to-one mapping between coupled RNA and ATAC representations, which correspond to those in the red box ("Highly Coupled RNA-ATAC Pairs") in (M). M The Pearson’s correlations between latent representations for HALO (coupled representations), HALO (decoupled representations), GLUE, scMVP, MIRA, and MultiVI. Boxplots show the median (center line), interquartile range (box), and data within 1.5 × IQR from the quartiles (whiskers). All individual data points are overlaid on the boxplots. N The enriched transcription factors (TFs) for coupled ATAC latent representation 3 and decoupled ATAC latent representation 14. O The genomic matching score of coupled representations with different genomic distances from genes' TSS locations. Genomic matching score calculates the fraction of important ATAC representation peaks that lie within the specified genomic distance from the TSS of significant RNA representation genes. P The gene ontology (GO) enrichment of top genes from RNA coupled representation 3. Fisher’s exact test is used to calculate p-values for gene set enrichment analysis. SHARE-seq data are available at the MultiVelo website. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

To analyze the decoupled ATAC representation , we performed clustering on it. Cluster 4 (Fig. 2D) is notably characterized by the decoupled ATAC latent representation 14 (Fig. 2H). Additionally, we have mapped cluster 4 onto the original SHARE-seq UMAP projection (Fig. 2E and Supplementary Fig. 1B), revealing that cluster 4 corresponds to novel root cells4. These novel root cells were previously identified by chromatin potential, which is a quantitative measure of chromatin lineage-priming and used for cell fate prediction4. Moreover, it is also demonstrated that novel root (cluster 4) express distinct marker genes in comparison to expected root cells (Fig. 2K). To validate this novel cell state in HALO’s framework, we evaluated the decoupled ATAC and RNA representations and found that, consistent with the definition of chromatin potential4, the cosine distance between the decoupled representations is maximal within the novel root (Fig. 2I, J). By utilizing the interpretable decoder, HALO can identify the enriched transcription factors (TFs) within specific latent ATAC representations. Figure 2N shows the significantly enriched TFs in coupled representation 3 and decoupled representation 14, including Wt1 and Pou5fl. Transcription factors Wt1 and Pou5f1 are important in the Wnt/β-Catenin signaling pathway, exerting regulatory control over Lef1 and Dach116,17, which serve as marker genes for novel root cells. In coupled ATAC representation 3, the transcription factor Runx1 is enriched, which directly promotes the proliferation of hair follicle stem cells and affects hair morphogenesis and differentiation. Coupled RNA representation 3, which is highly correlated with coupled ATAC representation 3, captures Eda, Wnt, and Sonic hedgehog (Shh) signaling pathways, which are important for hair follicle morphogenesis (Fig. 2P)18.

To validate the relations between the coupled and decoupled representations of the two modalities, we calculate the Pearson’s correlations between the latent representations (Fig. 2L), which reveals a strong correlation between the ATAC and RNA coupled representations. In contrast, the decoupled representations exhibit a weaker correlation. Additionally, we assessed the correlations of latent representations between modalities using various alternative representation learning methods, including MIRA12, GLUE14, MultiVI13, and scMVP19. The comparative analysis (Fig. 2M and Supplementary Fig. 1D) indicates that HALO’s decoupled representations maintain the lowest correlations, whereas its coupled representations are highly correlated across modalities in four distinct datasets: Mouse Brain from 10× genomics, NEAT-Seq20, NeurIPS21, and systemic sclerosis-associated interstitial lung disease (SSc-ILD) pulmonary epithelium. HALO outperforms the compared methods because it explicitly models both decoupled (asynchronously changing) and coupled (synchronously changing) information between scRNA-seq and scATAC-seq, leveraging temporal causal constraints that we introduce. In contrast, multiVI and scMVP operate under the assumption that scRNA-seq and scATAC-seq share the same information entirely. We further interrogate whether the decoupled representations identified by HALO represent modality-specific batch bias or truly modality-specific biological information. To address this, we compared HALO’s performance in batch correction against that of other frameworks on the NeurIPS datasets21, which are known to contain substantial batch effects (Supplementary Fig. 1E), by evaluating silhouette score22 and Hilbert–Schmidt Independence Criterion (HSIC) (“Methods” Section “Evaluation metrics”).

HALO is particularly effective at removing batch information, thereby confirming that its decoupled representations predominantly capture modality-specific biological information.

To further examine our approach, we have developed a genomic matching score for coupled RNA and ATAC representation pairs (“Methods” Section “Evaluation metrics”) that assesses the distance between their important genes and peaks by calculating the ratio of peaks that are located within the cis-regulation regions of the genes. Figure 2O presents genomic matching scores for the coupled ATAC-RNA representation pairs in the mouse skin hair follicle dataset, which demonstrates that HALO’s coupled representations can capture regulatory interactions between peaks and gene expressions.

HALO characterizes gene-peak interactions in a temporal causal perspective

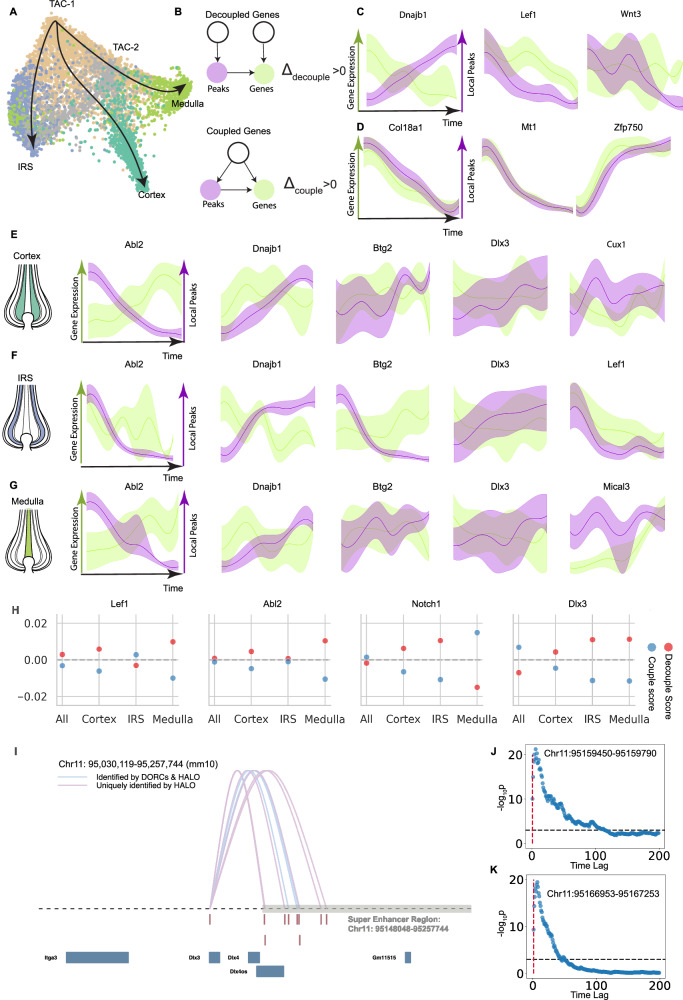

To characterize the causal temporal relations between individual genes and peaks, we categorize gene-peak pairs into coupled genes and decoupled genes (Figs. 1A, 3B, and 4). Employing negative binomial regression from denoised nearby peaks to denoised gene expression penalized by genomic distance, we align gene-peak pairs (See “Methods” Section “Gene-peak matching”). Upon aggregating these matched peaks, HALO calculates decouple and couple scores to quantitatively assess the extent of decoupledness and coupledness in gene-peak relationships, with positive scores suggesting decoupled and coupled relations, respectively. Supplementary Fig. 3 displays the simulation outcomes for the decouple scores of both decoupled and coupled simulated gene-peak pairs under different simulation conditions: gene expression distribution, number of time points, sample size, signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), and dropout rate (See Supplementary Methods G). The results indicate that increased number of time points (Supplementary Fig. 3D), sample size (Supplementary Fig. 3E), and SNR (Supplementary Fig. 3F) or conversely, lower dropout rates (Supplementary Fig. 3G) improves the ability to distinguish coupled from decoupled gene-peak pairs in terms of the decouple score.

Fig. 3. The individual gene level results of SHARE-seq mouse skin follicle hair dataset.

A The development trajectory of mouse hair follicle cells, including the branches for medulla, cortex, and inner root sheath (IRS) cells. B The causal diagrams of decoupled and coupled individual gene-peak pairs. If the decouple score Δdecouple > 0, we classify the gene-peak pair as decoupled. If the couple score Δcouple > 0, we classify the gene-peak pair as coupled. In (C–G), the curves represent the median across replicates, and shaded bands indicate the interquartile range (IQR), spanning the 25th to 75th percentiles. C Examples of gene-peak pairs that are decoupled when analyzed across all branches. D Examples of gene-peak pairs that are coupled when analyzed across all branches. E Examples of decoupled gene-peak pairs in the Cortex branch. F Examples of decoupled gene-peak pairs in the IRS branch. G Examples of decoupled gene-peak pairs in the Medulla branch. H The decouple/couple score of genes on different developmental branches. The decouple score is positive when a gene-peak pair is identified as decoupled, while the couple score is positive when the pair is identified as coupled. Lef1 predominantly exhibits decoupled behavior across most branches, with the exception of IRS. Abl2 displays decoupled behavior specifically in the Cortex and Medulla. Notch1 shows strong coupling in the Medulla but is decoupled in both the Cortex and IRS. Dlx3 is consistently decoupled across the Cortex, IRS, and Medulla. I The loops denote significant connections between peaks within super enhancer region and RNA expression of Dlx3. The connections between the expression of Dlx3 and peaks are identified by HALO's gene-peak-matching algorithm and DORC as reported by original study4. J The scatter plot visualizes significance of Granger causal relations between Itga3 gene expression and peaks in Chr11: 95159490-95159790. The X-axis is the time lag (number of cells, sorted by latent time), Y-axis is −log(p-values). Granger causality significance is evaluated by using the peaks of all previous cells [ct−n, ct) up to lag n (number of cells with index preceding time t) to determine the gene expression for cell ct, where t is determined by latent time sequential ordering of all cells. K Scatter plot of Granger causal relations between Itga3 gene expression and peaks in Chr11: 95166953-95167253. The X-axis is the time lag (number of cells sorted by latent time), Y-axis is −log(p-values). We utilize the likelihood ratio test for the Granger causality-based regulation inference for (J and K). SHARE-seq data are available at the MultiVelo website. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Fig. 4. Proportions of decoupled and coupled gene-peak pairs across four datasets.

The Y-axis represents the proportion (ranging from 0 to 1), and the X-axis shows different cell types or states. A Mouse skin follicle dataset, stratified by cell type. B Mouse brain dataset, stratified by cell type. C NEAT-seq CD4+ T cell dataset, grouped by cell state. D SSc-ILD (SSC) and normal (NOR) cell dataset, grouped by clusters (AT2: clusters 0 & 1; airway epithelial cell: cluster 2; AT1: cluster 3; TRB-SC: cluster 4). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

We further examine the SHARE-seq hair follicle data to study gene regulation or lineage-specific gene-peak interactions. This dataset represents several lineages, differentiating from transit-amplifying cells (TACs) to inner root sheath (IRS), medulla, and cuticle/cortex cells (Fig. 3A). Figure 3C, D and Supplementary Fig. 5A, B highlight the decoupled and coupled gene-peaks across all branches, with their respective couple and decouple scores (Fig. 3H and Supplementary Fig. 4A and C). Additionally, HALO takes into account distinct developmental lineages: the cortex (Fig. 3E and Supplementary Fig. 5C, D), IRS (Fig. 3F and Supplementary Fig. 5E, F), and medulla (Fig. 3G and Supplementary Fig. 5G, H). By examining the decoupled genes (Abl2, Dnajb1, Dlx3, and Btg2) across different branches or within specific lineages, it becomes apparent that these gene expression levels and corresponding peaks change independently over time. Specifically, Dlx3 exhibits decoupled behaviors on all three branches (Fig. 3H); the gene expression remains relatively stable, but the aggregated peaks keep going up with time (Fig. 3E–G). Some genes (Notch1, Dlx3) exhibit coupled expression across all cells, but show decoupled behaviors within specific lineages, highlighting that gene regulation is highly context-specific.

We address the question of why these peaks continue to increase by examining the downstream effect of the accessibility of a local chromatin region on the gene expression of potential regulation targets other than the corresponding gene. Granger causality is well suited for the task of inferring these regulatory relationships due to the time lag between changes in a local peak and target gene expression. By utilizing the Granger causality test (see “Methods” Section “Granger causal regulatory interaction inference”), we are able to identify the distal regulation relations among Dlx3’s corresponding peaks and nearby genes other than Dlx3. In Fig. 3I, the pink loops are peak-gene interactions inferred by DORC (Domains of Regulatory Chromatin)4, while the blue loops are uniquely detected by HALO. By predicting gene expression using the peaks of preceding cells with respect to ascending latent time, we find that nine local peaks within mouse skin hair follicle super enhancer region exhibit Granger causal relations with the expression of Itga3 (Fig. 3J, K and Supplementary Fig. 4B)23.

To investigate variation in regulation mechanisms under different contexts, we computed the percentages of coupled and decoupled gene-peak pairs in the top 1000 highly variable genes across cell types (and disease states when applicable) within each dataset. From these results, we observe that cells in transitional states—such as TAC, Cortex, and Medulla in the skin follicle dataset (Fig. 4A), and V-SVZ, IPC, and Ependymal cells in the brain dataset (Fig. 4B)—tend to have a higher proportion of decoupled gene-peak pairs, further showing that these cell states have high epigenetic plasticity4,7. In contrast, the NEAT-seq CD4+ T cells, which represent a more mature cell state, exhibit a relatively lower ratio of decoupled pairs (Fig. 4C). In the SSc-ILD pulmonary epithelial dataset, we observe a higher proportion of decoupled gene-peak pairs in stem-like cells (alveolar type-2 (AT2): clusters 0 and 1) and transitional cell states (terminal and respiratory bronchiole-specific secretory cell (TRB-SC): cluster 4), while terminally differentiated cells (alveolar type-1 (AT1): cluster 3) display a lower proportion (Fig. 4D). Interestingly, the proportion of decoupled pairs increases in AT2 and TRB-SC cells under SSc-ILD conditions, suggesting dynamic gene regulatory changes associated with disease progression. In summary, by analyzing gene-peak pairs at the individual gene level, HALO effectively distinguishes between coupled and decoupled interactions, as well as illustrates that local peaks of decoupled genes may contribute to expression of nearby genes.

HALO uncovers regulatory factors in primary human CD4+ effector T cells assayed by NEAT-seq

NEAT-seq profiles the intra-nuclear protein epitope abundance of a panel T cell master transcription factors (TFs), chromatin accessibility, and transcriptome in single cells20. Due to post-transcriptional regulatory mechanisms affecting the protein expression of T helper 2 (Th2) master TF GATA324, we can leverage the protein quantification of GATA3 for more cell state information than can be gleaned from using RNA expression levels alone. HALO infers latent representations utilizing nuclear protein level of GATA3 as a proxy variable for latent time (see “Methods” “Time estimation”) and constructs UMAP embedding to visualize distinct T cell subsets (Fig. 5A and Supplementary Figs. 6A–C, 7, and 8). Notably, two coupled latent representations, RNA coupled 9 and ATAC coupled 9, show negative correlations with the nuclear protein level of GATA3 (Fig. 5B, C). RNA coupled 9 captures mTORC1 signaling (Fig. 5D), which negatively regulates Th2 differentiation25. Consistently, ATAC coupled 9 is enriched in ZFX/NR4A motifs (Fig. 5E), where NR4A is known to suppress Th2 genes26,27. Conversely, T helper 17 (Th17) specific ATAC coupled representation 12 exhibits enrichment in NR2F6/ARID5A motifs (Fig. 5E and Supplementary Fig. 8), which are essential for the differentiation and function of Th17 cells28,29.

Fig. 5. HALO reveals regulatory factors of human CD4+ effector T cell dataset.

A UMAP visualization of human CD4+ effector T cells constructed from concatenated RNA and ATAC representations, colored by original cell type, as well as nuclear protein, gene accessibility, and gene expression of GATA3. B RNA coupled 9 and ATAC coupled 9 representations on UMAP embedding of concatenated RNA and ATAC representations. C Scatter plot visualization of GATA3 nuclear protein level and coupled latent representations (RNA coupled 9 and ATAC coupled 9). P-values are calculated using a two-sided Pearson’s correlation test. D Gene set enrichment for genes from latent representation RNA coupled 9. Fisher’s exact test is used to calculate p-values for gene set enrichment analysis. E Motif enrichment for ATAC coupled 9 and ATAC coupled 12 representations. F Nuclear protein levels of T-bet on UMAP embedding of RNA and ATAC representations. In (G, H) the curves represent the median across replicates, and shaded bands indicate the interquartile range (IQR), spanning the 25th to 75th percentiles. G Gene-peak pairs of GZMA in Th1 cells, sorted by T-bet nuclear protein level. H Gene-peak pairs of GZMA in Th1 cells, sorted by GATA3 nuclear protein level. I Scatter plot of Granger causal relations between GZMK gene expression and peaks in Chr5: 55061993-55104523. The X-axis is the time lag (number of cells, sorted by T-bet nuclear protein level), Y-axis is −log(p-values). J Scatter plot of Granger causal relations between GZMK gene expression and peaks in Chr5: 55061993-55104523. The X-axis is the time lag (number of cells, sorted by GATA3 nuclear protein level), Y-axis is −log(p-values). K Scatter plot of Granger causal relations between GZMK gene expression and peaks in Th1-specific T-bet super enhancer region (Chr5: 55061993-55073122). The X-axis is the time lag (number of cells, sorted by T-bet nuclear protein level), Y-axis is −log(p-values). We utilized the F-test for the Granger causality-based regulation inference for (I–K). L The loops denote significant connections between local peaks and RNA expression of GZMA. The connections between the expression of GZMA and peaks are identified by a gene-peak-linking algorithm. NEAT-seq data are available at GEO accession number GSE178707. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

GATA3 regulates the Th2 cell fate decision in CD4+ T cells, while T-bet orchestrates T helper 1 (Th1) differentiation. Both T-bet and GATA3 are co-expressed in Th1 cells, rather than being exclusively present in their respective lineages (Fig. 5F). Within Th1 cells, T-bet suppresses Th2 genes by redistributing GATA3 from Th2 gene loci to T-bet binding sites within Th1 gene regions30. Granzyme genes (GZMA, GZMB, GZMK) possess binding sites specifically targeted by both T-bet and GATA3 in Th1 cells31. To dissect the regulation mechanisms of different TFs, we calculate decouple scores for Th1 cells using protein levels of GATA3 and T-bet as temporal information. Intriguingly, expression of the GZMA gene and its local peaks exhibit decoupled dynamics in Th1 cells (Fig. 5G, H). As GATA3 protein levels rise, local peaks of GZMA become less accessible, even though GZMA gene expression is increased at high GATA3 protein levels (Fig. 5H). Consistently, CD4+ T cells co-expressing T-bet and GATA3 exhibit upregulation of GZMA gene expression, compared to cells expressing only T-bet (Supplementary Fig. 6D). Conversely, increases in nuclear T-bet levels enhance the accessibility of local GZMA regulatory genome regions, while GZMA gene expression level remains constant (Fig. 5G). Using nuclear protein levels as temporal information, Granger causality tests reveal that local peaks of GZMA mediate the gene expression of GZMK (Fig. 5I–L). Strikingly, local peaks of GZMA within the Th1-specific T-bet super enhancer region are also crucial for regulating gene expression of GZMK 32. Leveraging TF protein levels as proxies for temporal information, HALO coupled representations not only exhibit strong correlation between RNA and ATAC modalities, but also capture similar biological contexts (Supplementary Fig. 6E). HALO allows us to further investigate the regulation of a TF using Granger causality tests to determine downstream enhancers and their gene targets.

HALO reveals epigenetic regulation of alveolar epithelial differentiation in SSc-ILD

Systemic sclerosis (SSc) is an autoimmune disease characterized by fibrosis in the lungs and other organs. In SSc-ILD, alveolar epithelial cells are decreased due to impaired regeneration function, while airway epithelial cells (ciliated, club, goblet, basal) increase in fibrotic lesions33. Recent scRNA-seq analysis of human distal lungs and alveoli has shown that AT2 cells acquire a unique epithelial transition state, known as AT0, during primate lung regeneration and disease34. AT0 cells have the potential to differentiate into either AT1 cells or TRB-SCs when cultured in vitro. However, in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), AT0 cells predominantly transform into terminal secretory cells within severe fibrotic areas, referred to as bronchiolized regions in IPF lungs34.

To investigate the molecular underpinnings of impaired alveolar epithelial regeneration in SSc-ILD, we analyzed alveolar epithelial and terminal secretory cells using single-cell multiome sequencing data from six SSc-ILD and seven control lungs35. Due to their distinct genomic profile, airway basal cells were excluded from downstream analysis. We identified five clusters of alveolar epithelial and terminal secretory cells based on the expression of known marker genes (Fig. 6A and Supplementary Fig. 9A–D). Two subpopulations of AT2 cells (clusters 0 and 1) exhibit similar transcriptomic profiles but differ in chromatin accessibility. Additionally, we identified AT1 cells (cluster 3) and TRB-SCs (cluster 4), which co-express SFTPB and SCGB3A2, along with club and goblet cells (cluster 2).

Fig. 6. HALO uncovers chromatin lineage-priming in AT2 cells collected from SSc-ILD lungs.

A UMAP visualization of pulmonary epithelial cells constructed from concatenated RNA and ATAC representations, colored by identified cell types. This UMAP embedding was used for later panels in this figure. B Differential abundance test using Milo to compare cluster populations in control and SSc-ILD samples. C RNA velocity analysis showing inferred differentiation trajectories of pulmonary epithelial cells to two terminal states. D UMAP visualization of pulmonary epithelial cells, colored by pseudotime. E ATAC latent representations (3, 4, 5, 14, 15) visualized on UMAP embedding. F Hypergeometric based enrichment test of cell type-specific super enhancer (alveolar epithelial or airway epithelial) for ATAC latent representations (coupled 3, 4, 5 and decoupled 14, 15). The dashed line indicates a p-value of 0.05, and above the dashed line indicates significant enrichment. G Motif enrichment for ATAC decoupled representations 14 and 15, where TFs essential for proximal and distal airway patterning during lung development are colored blue and red, respectively. P-values are calculated using hypergeometric test. H ChromVAR motif activity, local peaks, and gene expression of SOX4 in alveolar epithelial cells (clusters 0, 1, 3) from SSc and normal (NOR) lung, as well as cluster population ratio, sorted by pseudotime. I Volcano plot visualization of SSc-associated changes in gene expression and ChromVAR motif activity in cluster 3 (AT1). J Gene-peak pairs of SOX4 during AT2-to-AT1 differentiation (clusters 0, 1, 3) in alveolar epithelium, sorted by pseudotime. K Scatter plot showing Granger causal relations of CASC15 gene expression and local peaks of SOX4 in Chr6: 21478948-21597288. The X-axis is the time lag (number of cells sorted by pseudotime), Y-axis is −log(p-values). L. Scatter plot showing Granger causal relations of CASC15 gene expression and AT1-specific super enhancer region (Chr6: 21587154-21601721). The X-axis is the time lag (number of cells sorted by pseudotime), Y-axis is −log(p-values). We utilized the likelihood ratio test for the Granger causality-based regulation inference for (K and L). M The loops denote significant connections between local peaks and RNA expression of SOX4. Connections between the expression of SOX4 and peaks are identified by HALO's gene-peak-matching algorithm. N Transition probability matrix of AT2 cell (clusters 0, 1) differentiation trajectories under different conditions (NOR vs. SSc), calculated using optimal transport. The curves in (H and J) show the median across replicates, while the shaded bands indicate a custom central range, spanning the 40th to 60th percentiles. SSc-ILD related data are available at GEO accession number GSE302151. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Our analysis reveals a substantial decrease in the AT2 cell population and an increase in secretory cells in SSc-ILD samples (Fig. 6B). Additionally, AT2 cells in SSc-ILD lungs mirror the transcriptional state of AT2 cells cultured in EGF-depleted organoids (Supplementary Fig. 10A–E), where AT2 cells convert to AT0 cells and subsequently progress to TRB-SCs following EGF depletion34. Consistently, trajectory inference algorithms (scVelo36, CellRank 237, and Palantir38) applied to epithelial populations from both SSc-ILD and control samples reveal two terminal states in the AT2 differentiation trajectory. Cluster 1 progresses to secretory cells, passing through TRB-SCs, while cluster 0 differentiates into AT1 cells (Fig. 6C, D and Supplementary Fig. 9E, F).

To identify the epigenetic regulations underlying AT2 lineage specification, we applied HALO to infer latent representations utilizing Palantir pseudotime. While RNA profiles alone are insufficient to distinguish the two AT2 subpopulations, decoupled ATAC representations are informative in separating these two subpopulations (Supplementary Figs. 11 and 12A, B). Two decoupled ATAC representations (decoupled 14 and decoupled 15) characterize the transition from AT2 cells (cluster 1) to TRB-SCs (cluster 4) (Fig. 6E). With the interpretable decoder, we find that the top peaks contributing to the decoupled representations are enriched in airway epithelial-specific super enhancers and known transcription factors essential for proximal airway patterning during lung development39,40 (Fig. 6E–G). In contrast, three coupled ATAC representations describe the alveolar epithelial populations (clusters 0, 1, 3, & 4), which are enriched in alveolar epithelium-specific super enhancers (Fig. 6E, F). Consistently, ChromVAR motif activity analysis indicates that cluster 1 exhibits lower motif activity for alveolar lineage transcription factors (NKX2-1 and CEBPA) compared to cluster 0, the other AT2 cluster (Supplementary Fig. 10F). CEBPA restricts AT2 cell plasticity during development and injury-repair, while CEBPA-dependent regulation recruits alveolar epithelial lineage TF NKX2-1 to promote and maintain the AT2 program41–44. Additionally, there are increased motif activities of transcription factors for proximal airway patterning and decreased motif activity of CEBPA in AT2 cells (cluster 0 & 1) from SSc lungs (Supplementary Fig. 10G). Analysis of modality-specific decoupled representations using HALO’s interpretable framework enables us to discover the epigenetic landscape and cell fates of alveolar epithelial cells.

We further evaluate transition probabilities among these clusters using optimal transport based on RNA and ATAC representations obtained from HALO (see “Methods” Section “Optimal transport for lineage prediction”). In normal lungs, both AT2 clusters would progress to AT1. However, in SSc lungs, although cluster 0 still differentiates into AT1, cluster 1 predominantly transforms into TRB-SCs (Fig. 6N and Supplementary Fig. 9G), demonstrating that bipotent AT2 cells exhibit different cell fate decisions under SSc conditions. This suggests that HALO is able to depict a comprehensive portrait of alveolar differentiation, while defining epigenetic regulatory effectors of cell identity and pathology.

We then apply HALO to examine disease-associated decoupled genes. The epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) master regulator SOX4 plays a crucial role in AT2-to-AT1 differentiation45,46. In SSc-ILD, both the expression and local peaks of SOX4 increase (Fig. 6H, I). The dynamics of SOX4 gene expression and its local peaks become decoupled during terminal differentiation to AT1 in SSc lungs (Fig. 6J); the local peaks remain accessible while the gene expression decreases. Strikingly, these local peaks of SOX4 are significantly Granger causally related to the expression of the EMT-associated long non-coding RNA (lncRNA) CASC15 (Fig. 6K–M). Additionally, local peaks of SOX4 within AT1-specific super enhancer regions contribute to the expression of CASC15. In the SSc condition, regulatory events of SOX4’s local peaks exhibit longer time lag compared to the normal condition. A previous study has shown that CASC15 is upregulated in aberrant basaloid cells, an epithelial cell type displaying a partial EMT phenotype in ILD lungs47. Using HALO, we uncover disease-specific decoupled genes that may contribute to SSc-ILD pathogenesis.

To further characterize the dysregulated gene regulatory network of AT2 cells under SSc conditions, we infer TF-CRE-gene linkages (Supplementary Methods I). Among these, the EGR, RFX, TCF, and NFI family transcription factors (TFs) exhibit the largest positive average differences in chromVAR motif activity (Supplementary Fig. 12C and Supplementary Table 1). Notably, RFX family TFs are crucial for airway epithelial differentiation, while TCF and NFI family TFs play essential roles in alveolar epithelial differentiation, survival, and regeneration46,48,49.

Discussion

The relationship between chromatin accessibility and gene expression is complex and often asynchronous. Previous methods assume that the two are synchronized with respect to time, thus missing nuances like time-lagging effects and independent regulatory mechanisms. HALO aims to address these gaps by differentiating between coupled (dependent) and decoupled (independent) changes from a causal perspective. The framework operates at both representation and individual gene levels to learn interpretable modality-specific and shared information, as well as to characterize gene and associated peak interactions.

We conduct extensive benchmarks to evaluate the performance of HALO from different perspectives. Across several datasets, we demonstrate that HALO effectively learns highly coupled information across modalities while preserving decoupled and modality-specific information rather than reflecting batch bias. The highly coupled RNA and ATAC representation pairs, characterized by high Pearson’s correlation, capture functionally analogous biological contexts. In contrast, decoupled ATAC representations can inform our knowledge of chromatin accessibility-mediated cell fate potentials during the differentiation of mouse skin hair follicles and alveolar epithelium. Notably, we confirmed the bipotency of a subset of AT2 cells that acquire a previously reported transitional cellular state with the potential to differentiate into TRB-SCs or AT1 cells depending on niche signals34,50. We demonstrate that epigenetic information can shape this cell fate decision by conducting motif enrichment and cell type-specific super enhancer analyses on HALO’s decoupled representations. Achieving a deeper understanding of the factors underlying the diverging differentiation paths of AT2 cells opens the door to therapeutic options for a variety of lung diseases.

At the individual gene level, HALO distinguishes between coupled and decoupled gene-peak pairs. For decoupled cases where associated chromatin regions become more accessible, but gene expression remains stable or decreases, HALO employs Granger causality tests to assess distal regulatory interactions between associated peaks and nearby genes. We find that peaks overlapping with super enhancer regions often exhibit such decoupled behavior and are involved in distal regulation during cellular transition or developmental trajectories. Additionally, HALO uncovers SSc-ILD-specific regulatory mechanisms, such as the decoupling of SOX4 expression and its local peaks during AT2-to-AT1 differentiation. We show that during this differentiation under SSc conditions, chromatin regions in the intersection of SOX4 local peaks and AT1-specific super enhancers are responsible for regulation of the lncRNA CASC15.

Although a current limitation of HALO is the requirement for paired single-cell RNA-seq and ATAC-seq measurements from the same cells, recent advances in single-cell technologies are making such multi-omics data increasingly accessible. Importantly, paired profiling provides a more accurate and granular view of gene regulation by directly linking chromatin accessibility to gene expression at the single-cell level. In contrast, unpaired data necessitate computational integration across modalities, which can introduce alignment errors, particularly in the presence of rare cell types, batch effects, or continuous cellular transitions.

As multi-omics datasets become more widespread, we anticipate that the advantages of paired profiling will continue to grow, including along the axis of increased omics layers. To enhance HALO’s applicability, future work can extend the framework to include profiling of additional modalities, such as methylation and protein levels, to provide a more comprehensive understanding of gene regulation dynamics. Additionally, leveraging spatial epigenome-transcriptome co-profiling technologies could allow HALO to uncover spatiotemporal dynamics and genome-wide gene regulation mechanisms within tissue contexts51. These advancements would extend HALO’s utility as a valuable tool for understanding the functions and regulatory mechanisms of cell populations.

Methods

Causal representation learning

We employ a modified variational autoencoder framework to learn latent representations from single-cell multi-omics data, incorporating causal constraints to model temporal dependencies between modalities. The model takes as input the dataset , consisting of co-assayed scRNA-seq and scATAC-seq data, along with time information and additional batch information for the two modalities. HALO uses two separate encoders to process the scRNA-seq and scATAC-seq modalities, producing low-dimensional latent representations and , respectively. The latent representations ZA and ZR are further decomposed into coupled and decoupled components: , with , and , with . These components serve together with time information as inputs to the causal constraint module, which enforces temporal relationships between the modalities, as illustrated in Fig. 1A.

Causal constraints of the latent representations

In most biological processes, the underlying mechanisms change with time, and this displacement is referred to as distribution shift. In the setting of our framework, this corresponds to changes over time in the mechanism by which chromatin accessibility affects gene expression. It is usually assumed that the quantities that change over time can be written as functions of a time index T 52. Our goal is to characterize the changing causal mechanisms between the latent spaces of scATAC- and scRNA-seq. For the decoupled case, and have independently changing mechanisms along T within the cell lifespan, but and change dependently. Thus, we aim to enforce that and change independently, and that and change dependently. The following conditional distributions are designed to capture these dynamics for both the coupled and decoupled representations.

| 1 |

Let ϕ( ⋅ ) be the feature map for . The following kernel embeddings are derived for Eq. (1),

| 2 |

where , , and ⊙ represents point-wise product.

A score function based on the embedding is proposed to quantify the dependence between the changes in ZA and ZR, defined as follows:

| 3 |

where is the trace of a matrix and , , , and denote the Gram matrices52–54 computed for ZA, ZR, and respectively. The matrix H is used for centering, with entries defined as , where δij = 1 if i = j, and N is the number of samples. The score measures the dependence between the conditional distribution p(ZR∣ZA) and p(ZA). Similarly, measures the dependence between p(ZA∣ZR) and p(ZR). Between these two dependence measures, if the value of is smaller, we posit that p(ZR∣ZA) and p(ZA) change independently, and that the causal relation is ZA → ZR. In our case, for the decoupled representations and , should be smaller than , based on our knowledge of chromatin accessibility and transcription. On the other hand, for the coupled case, and should be similar in value and both larger than a threshold α52. Formally, the causal constraints of and are given by the constraints as follows,

| 4 |

For more details on the causal constraints, please refer to Supplementary Methods B.

Generative models

A generative model is employed to learn the low-dimensional representations , , , using input scRNA-seq XR and scATAC-seq XA data, along with modality-specific batch covariates BR and BA13,55. To model the expression value of gene g in cell i, denoted , we specify the following distributions.

| 5 |

where is the scaling factor in cell i, is the normalized composition of gene g across all genes in cell i, and is the gene dispersion. Similarly, for chromatin region j of cell i, we consider as a multinomial distribution,

| 6 |

where denotes the normalized frequency of accessibility in region j for cell i, and is the library size (scaling factor) for cell i. are modeled using log-normal distributions. The resulting vectors of library sizes across all cells are denoted as , . Mean field variational inference is employed to estimate the latent representations, using the following factorized posterior distribution:

| 7 |

The corresponding evidence lower bound (ELBO) is then formulated as follows:

| 8 |

Specifically, the following posterior distributions are defined:

| 9 |

| 10 |

| 11 |

| 12 |

where μA, μR are the means and ΣA, ΣR are the covariance matrices of ZA, ZR, respectively. Deep neural networks are used to estimate the following components:

| 13 |

| 14 |

| 15 |

| 16 |

The prior distribution is specified as the standard Gaussian distribution,

| 17 |

| 18 |

| 19 |

| 20 |

Next, the causal constraints introduced in the previous section are incorporated into the final optimization objective. Both the coupled and decoupled representations are regulated by the constraints defined in Eq. (4), leading to the formulation of the causal constraint term with a hyperparameter α,

| 21 |

To further enforce alignment between the paired coupled and decoupled representations, the model assumes that causes and causes . To implement these assumptions, the following neural layers are added:

| 22 |

where fd and fc are fully connected layers with batch normalization and leaky ReLU activations. The objective is to minimize the following term :

| 23 |

The main loss can be defined with parameters ω1, ω2 as follows:

| 24 |

Accordingly, the overall optimization objective is defined as follows:

| 25 |

The hyperparameter selection procedures and ablation study for α, ω1, ω2 are provided in “Methods” Section “Training setup and hyperparameter tuning” and Supplementary Methods J. During the representation retrieval stage, the latent representations are estimated using the reparameterization trick from the posterior distribution:

| 26 |

Note that the mean values are used in all downstream analyses. ZA, ZR can be concatenated to incorporate all the information across modalities for downstream analysis as follows:

| 27 |

The architectures of all the networks are listed in Supplementary Methods C.

Optimal transport for lineage prediction

We utilize optimal transport to further validate whether the latent coupled/decoupled representations are able to predict lineage trajectory of cells. For each cell i, with i = 1, 2, …, n, we have the (decoupled or coupled or both) latent representations Zi. The cost matrix is then constructed, where each element d(Zi, Zj) represents the distance between cell i and j. Formally, the cost matrix can be formulated as follows,

| 28 |

The optimal transport problem is solved using the Sinkhorn distance, based on the predefined cost matrix M, along with specified initial and terminal cell states. The objective is to compute the transportation matrix that aligns these states. For implementation, we use the POT library (version 0.9.3)56. In this study, squared Euclidean distance is used as the metric for constructing M.

Individual gene-peak pair analysis

In this section, we outline the procedures for individual gene-level analysis, including gene-peak matching, gene level couple and decouple scores, and Granger causality-based inference of regulatory interactions.

Gene-peak matching

HALO correlates local scATAC-seq peaks with gene expression values, by searching within a certain distance upstream and downstream of local peaks to maximize the probability of observing gene expression values. Specifically, for gene g ∈ {1, ngenes} in cell i, as well as estimated chromatin accessibility probability at chromatin region j ∈ {1, npeaks} and its probability (see “Methods” Section “Generative models”), we have the following model:

| 29 |

where Ng is the set of peaks j in the regions upstream, downstream, and proximal to the TSS of gene g; βj ~ HalfNormal(0, 1) is the scaling factor for the influence of peaks in upstream, downstream, and proximal regions to the gene g; ηgj is the TSS distance; and δgj is the decay parameter. HALO learns these parameters {βj, ηg j, δg j} by maximizing the likelihood of estimated in the previous representation learning phase. The upstream and downstream regions span from 1.5 to 600 kbp relative to the TSS, while the proximal region is within 1.5 kbp. HALO estimates the parameters by maximizing the likelihood:

| 30 |

Following a similar approach to previous work12, HALO applies variational inference to estimate point values for each parameter, using delta distribution priors. Model optimization is performed by maximizing the ELBO using the frozen-batch L-BFGS algorithm57 and implemented in Pyro58.

Couple and decouple scores

Similarly to the representation level, we define to measure the dependence between p(X R∣XA) and p(XA), and to measure the dependence between p(XA∣X R) and p(X R),

| 31 |

where and are the Gram matrices59, H is used to center the feature with entries , and δij = 1 when i = j. Calculating and is challenging because single-cell sequencing data suffer from sparsity problems. We utilize the aggregated estimated peaks as and averaged gene expression as for all cells with time label t. Specifically,

| 32 |

| 33 |

where Ng is all matched peaks for gene g in the upstream, downstream, and proximal areas of the TSS, [T = t] is the number of samples/cells where the time label is equal to t. is the estimated parameter for peak j’s multinomial distribution. is the estimated library size for peaks (scaling factor), is the shape variable in cell i of gene g’s negative binomial distribution, and is the estimated library size for gene expression. Given this estimated and , we can further calculate gene level couple and decouple scores as follows,

| 34 |

where α is a given threshold. From the definition of decouple score and couple score, if the decouple score is positive, we can identify gene g and peaks j as decoupled; otherwise if the couple score is positive, gene g and peaks j are coupled.

Granger causal regulatory interaction inference

To identify Granger causal relationships between a peak (or an aggregated peak count), , and the expression of a nearby gene, , we compare a full model and a reduced model over the time series [1, …, t], using a time lag window d 60:

| 35 |

where are the peak value and gene expression values at time t, respectively. The Granger causality test is formulated with the following hypotheses:

| 36 |

| 37 |

Hypothesis testing is performed using both the F-test and the likelihood ratio test. For more details, please refer to Supplementary Methods F.

Time estimation

Latent time estimation

Latent time or pseudotime can be estimated using standard methods to annotate cells. For the SSc human lung epithelium dataset, we use Palantir38, and for the mouse brain and skin datasets, we use latent time inferred by MultiVelo10.

Protein-based latent time estimation

In the NEAT-seq CD4+ memory T cell dataset, we estimate latent time using normalized intra-nuclear transcription factor protein levels. Antibody-derived tag counts were normalized using nuclear pore complex (NPC) protein levels and hashtag oligos20. The NPC normalization is given by:

| 38 |

Temporal pseudobulk

We primarily perform lineage-specific analyses by grouping cells along continuous trajectories of cell state transitions, rather than discretely classifying them into distinct cell types. To reduce issues associated with sparsity in downstream analyses, we divide cells into discrete time bins based on their inferred pseudotime and average their gene expression profiles within each bin. These averaged profiles, referred to as temporal pseudobulk units, represent temporally disjoint and internally homogeneous groups of cells. This approach assumes that cells with similar pseudotemporal ordering share similar omics profiles. Here, we summarize the averaged peaks and averaged gene expression for all cells with temporal bin label t. Specifically,

| 39 |

| 40 |

where ti represents the time bin membership of cell i. [T = t] denotes the number of cells in time bin t.

Evaluation metrics

Pearson’s correlations of representations

For HALO, Pearson’s correlations are computed across all elements of the coupled and decoupled latent representations. Specifically, let and denote the i-th and j-th elements of decoupled representations and respectively. Similarly, let and represent the i-th and j-th elements of coupled representations and .

| 41 |

For the other compared methods (MIRA12, GLUE14, multiVI13, and scMVP19), we calculated the Pearson’s correlations between all scATAC-seq and scRNA-seq representations. The Pearson’s correlation coefficient between two vectors X = [X1, …, Xn] and Y = [Y1, …, Yn] is defined as:

| 42 |

Genomic matching score

To evaluate the distance between important genes and peaks from coupled RNA and ATAC representation pairs, we calculate the genomic matching score. This score assesses the fraction of important peaks within the ATAC representation that fall within the gene regulation distance (up to 250 kbp) from the transcription start site (TSS) of significant genes in the RNA representation. The genomic matching score Si of the i-th ATAC representation is given by:

| 43 |

where Ci is the set of important peaks for , and CN,i is the set of important peaks for that fall within cis-regulatory distance of important genes in the most correlated RNA representation . ∣ ⋅ ∣ is the cardinality of a set. To calculate the score, we first select pairs of coupled RNA and ATAC representations with the highest Pearson’s correlation coefficients. Next, we identify significant gene and peak features that contribute to their respective latent representations. Specifically, for the SHARE-seq dataset, we extracted the top 100 RNA features and the top 2000 peak features from the corresponding coupled representation pairs.

Silhouette score

The Silhouette width61 is used to evaluate the extent to which sample dissimilarity is minimized within a batch and maximized across batches. For a sample X, dA(X) is the average dissimilarity between X and all other data points of the batch A that X belongs to, while dC(X) is the average dissimilarity between X and the samples in batch C where C ≠ A, meaning that is the average dissimilarity for the batch that is most similar to A. Using these definitions, we have the following silhouette width s(X) of X:

| 44 |

Next, the batch silhouette score for the cell label i is defined as:

| 45 |

where Li is the set of cells with the cell label i, and ∣Li∣ denotes the number of cells in that set. The average silhouette score is then defined as:

| 46 |

where M is the number of unique cell labels. We use the implementation from kBET61 for the evaluation.

HSIC on batches

We utilize the HSIC to evaluate the independence of the latent representations from batch variables. The lower the values are, the more independent the latent representations are from batch variables. Generally, the V-statistic-based HSIC estimator53 between Y and X for n samples is defined as:

| 47 |

where Lij = ϕ(Yi, Yj) and Kij = ψ(Xi, Xj) are symmetric kernel functions; and are the corresponding Gram matrices. is the centering matrix, where In is the n × n identity matrix, 1n is an n-dimensional vector of ones, and ⊤ denotes the transpose.

Normalized mutual information (NMI)

Normalized mutual information (NMI) is a metric used to evaluate the similarity between two clustering assignments. It scales the mutual information (MI) score to a value between 0 and 1, where 1 indicates perfect agreement and 0 indicates no MI between the clusterings. The NMI between two clusterings and is defined as:

where is the MI between and . and are the entropies of and , respectively.

Adjusted rand index (ARI)

The adjusted Rand index (ARI) measures the similarity between two clusterings by considering all pairs of samples, counting pairs with the same or differing cluster assignments in the clusterings and . It adjusts the Rand index (RI) for the chance grouping of elements. The ARI is defined as:

where nij is the number of data points in both cluster i in and cluster j in ; ai = ∑j nij is the number of data points in cluster i in ; bj = ∑i nij is the number of data points in cluster j in ; n is the total number of data points; denotes the binomial coefficient, representing the number of ways to choose 2 items from n.

Training setup and hyperparameter tuning

We extract 20% of the data from each dataset for testing. The remaining data are split into training and validation sets with a 4:1 ratio. For every dataset, we conducted an exhaustive hyperparameter grid search with n_epoch = 100 on the total loss with training and validation datasets. We denote dim as the dimension of the decoupled or coupled representations and we further set . The search spaces for the hyperparameters [ω1, ω2, α, dim] are shown as follows:

| 48 |

| 49 |

| 50 |

| 51 |

HALO is optimized using the Adam optimizer with a learning rate of 0.01, a weight decay of 0.001, and a minibatch size of 1024.

Dataset details and preprocessing

SHARE-seq mouse skin (hair follicle) dataset

We obtained this processed dataset directly from the MultiVelo website10. There are a total of 6436 cells and 962 genes in the MultiVelo processed data. The number of dimensions used for each type of latent representation is 10. The Granger causality test was performed using the likelihood ratio test.

NEAT-seq dataset

The NEAT-seq dataset profiles primary human CD4+ memory T cells using a panel of master TFs that drive T cell subsets, including T-bet, GATA3, RORγT, FOXP3, and Helios20. We obtained the processed dataset from GSE178707. After filtering out low-quality droplets, the dataset comprised 3370 cells with 13,380 genes and 78,203 peaks. Each type of latent representation was set to a dimensionality of 15. Gene regulatory relationships were explored using Granger causality tests with F-tests.

Binding sites of T-bet and GATA3 for Th1 and Th2 cells were downloaded from Data S1 of 10.1038/ncomms226031. The set of Th1-specific T-bet super enhancers was downloaded from 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.05.05432.

To assess the transcriptional impact of T-bet and GATA3 co-expression in T cells relative to T-bet expression alone, we analyzed bulk RNA-seq data from EL4-Tbet+GATA3 and EL4-Tbet+Plum cells, available from GSE17141030.

SSc-ILD human lung epithelium dataset

We used the 10× Genomics Multiome technology for paired snRNA-seq/snATAC-seq on nuclei from 6 SSc-ILD and 7 control human lung explants (reference human genome: hg38). The data are available at GSE30215135.

4708 alveolar epithelial and terminal secretory cells, with 3000 highly variable genes and 178,316 peaks, were used as input for the HALO model. Initially, the HALO model was trained based on ELBO loss only, and then the inferred latent representations were used for clustering and UMAP embedding construction using Scanpy62. Identified clusters were annotated using previously described cell markers34. Subsequently, the HALO model was trained using Palantir pseudotime for latent coupled and decoupled representations, where the number of dimensions for each type of latent representation is set to 10. The Granger causality test was performed using the likelihood ratio test for distal regulation identification.

The spliced and unspliced RNA count matrices were generated using Cell Ranger output BAM files with Velocyto CLI (v0.17.17)63. These matrices were then processed with scVelo (v0.3.1) to compute RNA velocity using the Dynamical mode36. The RNA velocity-based cell-cell transition matrix was combined with cellular similarity to infer the initial and terminal states of cellular dynamics using CellRank (v2.0.2)37. Cells from the initial state were used as the root to compute pseudotime with Palantir (v1.3.2)38.

To assess the information captured by HALO coupled and decoupled representations, a MLP classifier (scikit-learn v1.1.3) was trained to predict pulmonary epithelial cell type annotations.

A cell-cell transition matrix was inferred from the HALO representations using entropic-regularized optimal transport with a Sinkhorn solver (package POT v0.9.3)64 and a cost matrix inferred based on squared Euclidean distance. This cell-cell transition matrix was then subsequently aggregated into a cluster-cluster transition matrix. Additionally, we performed differential abundance testing to evaluate differences in cell abundances associated with disease using Milopy (v0.1.1)65.

To identify regulatory elements, transcription factor binding motifs in top-ranked peaks were identified using the FindMotifs function from the Signac package66. Enrichment for super enhancer regions was assessed via hypergeometric testing using datasets from Data S1 of 10.1016/j.cell.2013.09.05367 and SEdb 2.040. Motif activity scores were computed using Signac’s chromVAR wrapper and JASPAR 2022 motif profiles68,69.

The scRNA-seq data of human lung organoids from GSE178360 were re-analyzed using Seurat and Harmony for normalization, batch correction, dimensionality reduction, and clustering70,71. Marker genes and module scores for AT0, AT1, AT2, and TRB-SC were used to annotate cell types34. AT2 cells (Cluster 0) were isolated for differential gene expression analysis by comparing the EGF depletion group to the control group (Supplementary Fig. 10). Differentially expressed genes (with absolute logFC > 0.5, min.pct > 0.2, and p.adj < 0.05) were used to calculate the EGF depletion module score for the SSc lung epithelium dataset.

NeurIPS dataset

The NeurIPS single-cell multi-omics dataset was collected from mobilized peripheral CD34+ hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells isolated from four human donors at five time points. Samples were prepared using a standard protocol at four sites. The dataset was designed with a nested batch layout, with some donor samples measured at multiple sites and some donors measured at a single site. The processed data were downloaded from GSE19412272. In our paper, we subset 10,952 cells (Erythroblast, HSC, MK/E progenitor, Normoblast, and Proerythroblast) with pseudotime information for downstream analysis. The dimensionality of each type of latent representation is set to 10.

Human brain dataset

We obtained this processed dataset directly from the MultiVelo website10 with 4693 cells and 919 genes after processing. The number of dimensions for each type of representation is set to 10.

10× embryonic E18 mouse brain dataset

We obtained this processed dataset directly from the MultiVelo website10. In total, it contains 3365 cells, 936 highly variable genes, and 112,656 peaks; these matrices are then used for downstream analysis. The number of dimensions for each type of latent representation is set to 10.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Source data

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr. Christina Leslie and Dr. Sneha Mitra for providing the UMAP analysis used for the mouse skin dataset. The authors also thank Dr. Harinder Singh for valuable discussions. This work was partially supported by the following grants from the National Institutes of Health (NIH): R01HL159805, R01HL127349, R01HL178032, R01HL169332 (P.V.B.); P50AR080612 (R.L.), K08HL161258 (E.V.).

Author contributions

H.M. developed HALO, designed the analyses, performed the simulation study, and analyzed the SHARE-seq dataset. M.J. co-developed HALO, contributed to analysis design, and analyzed the NEAT-seq and 10× multiome SSc-ILD epithelial datasets. M.D. designed analyses and analyzed the mouse brain and NeurIPS datasets. K.Z. contributed to the design of the HALO. E.V., X.T.C., and R.L. contributed to the design of the analyses. P.V.B. helped with analysis design and supervised the overall work. E.V. and R.L. conducted the SSc single-cell experimental investigations. H.M., M.J., M.D., and P.V.B. drafted the original manuscript. H.M. and M.J. initiated the project. All authors contributed to the review and editing of the manuscript.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Jing Li, Hao Zhu, and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Data availability

Processed data for the SHARE-seq mouse skin (hair follicle) and 10× embryonic E18 mouse brain datasets are available at the MultiVelo website [https://multivelo.readthedocs.io]10. NEAT-seq data is available at GEO accession number GSE17870720, and the corresponding validation bulk RNA-seq at GSE17141030. Paired snRNA-seq/snATAC-seq data from SSc-ILD and control human lung explants for SSc human lung epithelium analysis were obtained from GSE30215135, as well as scRNA-seq data from GSE17836034 for root cell gene comparison. The NeurIPS dataset is available at GSE19412272. The human brain dataset is available at GSE16217073. Processed datasets are available at Zenodo [10.5281/zenodo.16040738]. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

The code used to develop the model, perform the analyses and generate results in this study is publicly available and has been deposited in GitHub at https://github.com/benoslab/HALO74, under an MIT CC-BY-NC-SA 4.0. license. It is also available under 10.5281/zenodo.16882163.

Competing interests

R.L. reports past grants from Bristol Meyer Squib, Formation, Moderna, Regeneron, and Pfizer. R.L. served or serves as a consultant with Abbvie, Mediar, Bristol Meyers Squibb, Formation, Thirona Bio, Sanofi, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Merck, Genentech/Roche, EMD Serono, Morphic, Third Rock Ventures, Bain Capital, and Zag Bio. R.L. sits on an independent data safety monitoring committees for Advarra/GSK and Genentech. R.L. is president and holds stock in Modumac Therapeutics Inc. E.V. reports grants from Boehringer Ingelheim. All other authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Haiyi Mao, Minxue Jia, Marissa Di.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-025-63921-1.

References

- 1.Baysoy, A., Bai, Z., Satija, R. & Fan, R. The technological landscape and applications of single-cell multi-omics. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol.24, 695–713 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Struhl, K. Fundamentally different logic of gene regulation in eukaryotes and prokaryotes. Cell98, 1–4 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Klemm, S. L., Shipony, Z. & Greenleaf, W. J. Chromatin accessibility and the regulatory epigenome. Nat. Rev. Genet.20, 207–220 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ma, S. et al. Chromatin potential identified by shared single-cell profiling of RNA and chromatin. Cell183, 1103-1116.e20 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ameen, M. et al. Integrative single-cell analysis of cardiogenesis identifies developmental trajectories and non-coding mutations in congenital heart disease. Cell185, 4937-4953.e23 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bonifer, C. & Cockerill, P. N. Chromatin priming of genes in development: concepts, mechanisms and consequences. Exp. Hematol.49, 1–8 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burdziak, C. et al. Epigenetic plasticity cooperates with cell-cell interactions to direct pancreatic tumorigenesis. Science380, eadd5327 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hawkins, R. D. et al. Distinct epigenomic landscapes of pluripotent and lineage-committed human cells. Cell Stem Cell6, 479–491 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mata, J., Marguerat, S. & Bähler, J. Post-transcriptional control of gene expression: a genome-wide perspective. Trends Biochem. Sci.30, 506–514 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li, C., Virgilio, M. C., Collins, K. L. & Welch, J. D. Multi-omic single-cell velocity models epigenome-transcriptome interactions and improves cell fate prediction. Nat. Biotechnol.41, 387–398 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu, J. et al. Jointly defining cell types from multiple single-cell datasets using LIGER. Nat. Protoc.15, 3632–3662 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lynch, A. W. et al. MIRA: joint regulatory modeling of multimodal expression and chromatin accessibility in single cells. Nat. Methods19, 1097–1108 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ashuach, T. et al. MultiVI: deep generative model for the integration of multimodal data. Nat. Methods20, 1222–1231 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cao, Z.-J. & Gao, G. Multi-omics single-cell data integration and regulatory inference with graph-linked embedding. Nat. Biotechnol.40, 1458–1466 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Singh, R., Wu, A. P. & Berger, B. Granger causal inference on DAGs identifies genomic loci regulating transcription. The 10th International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR), on line event, Paper at https://openreview.net/pdf?id=nZOUYEN6Wvy (2022).