Abstract

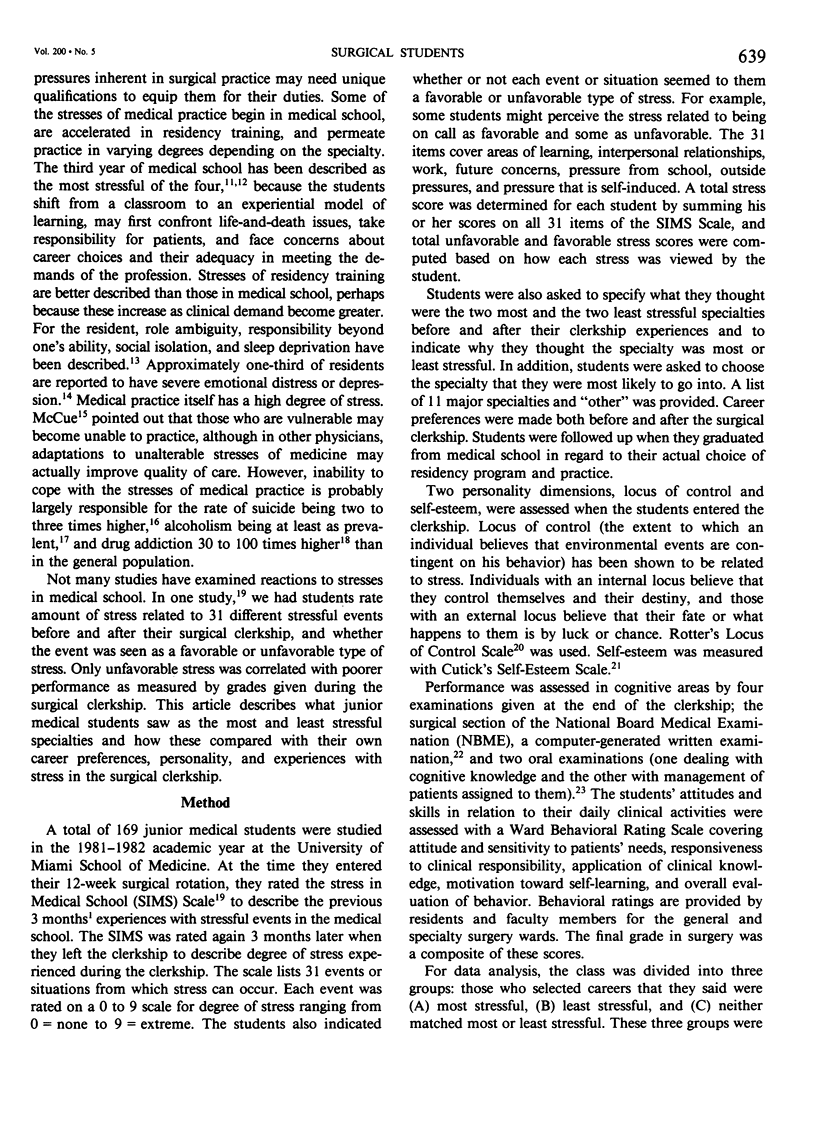

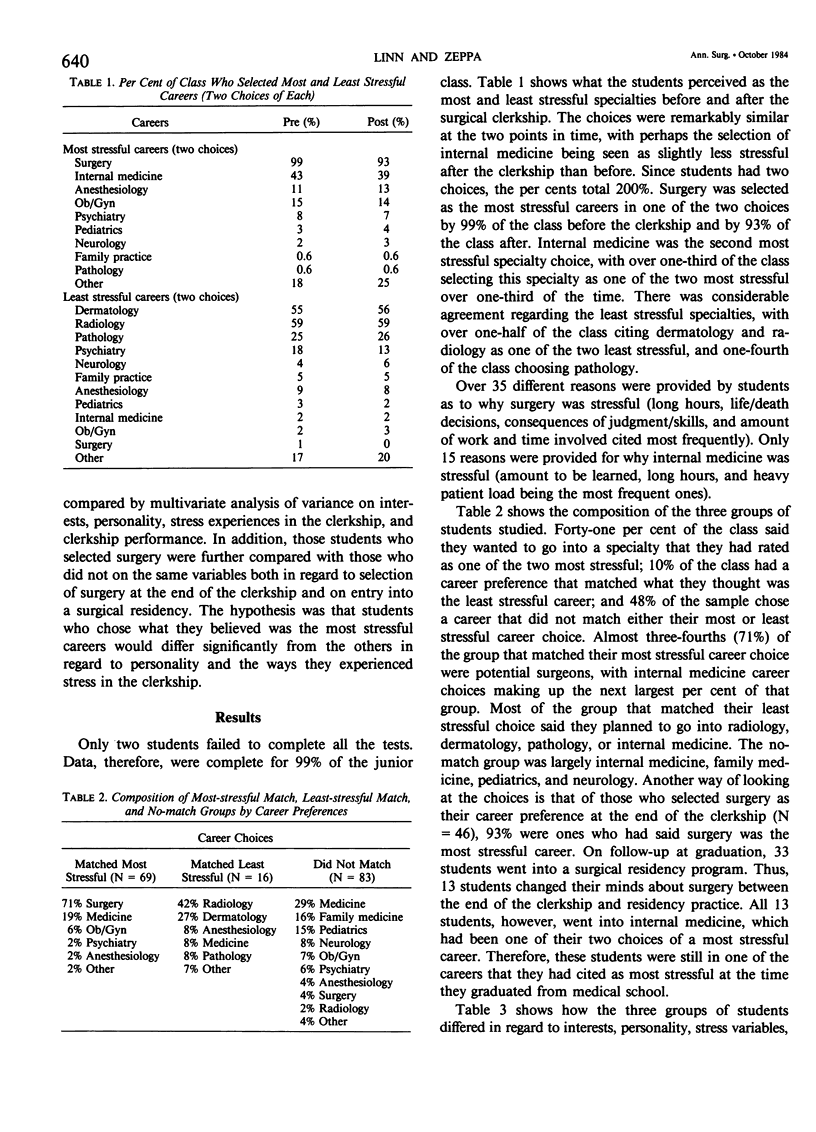

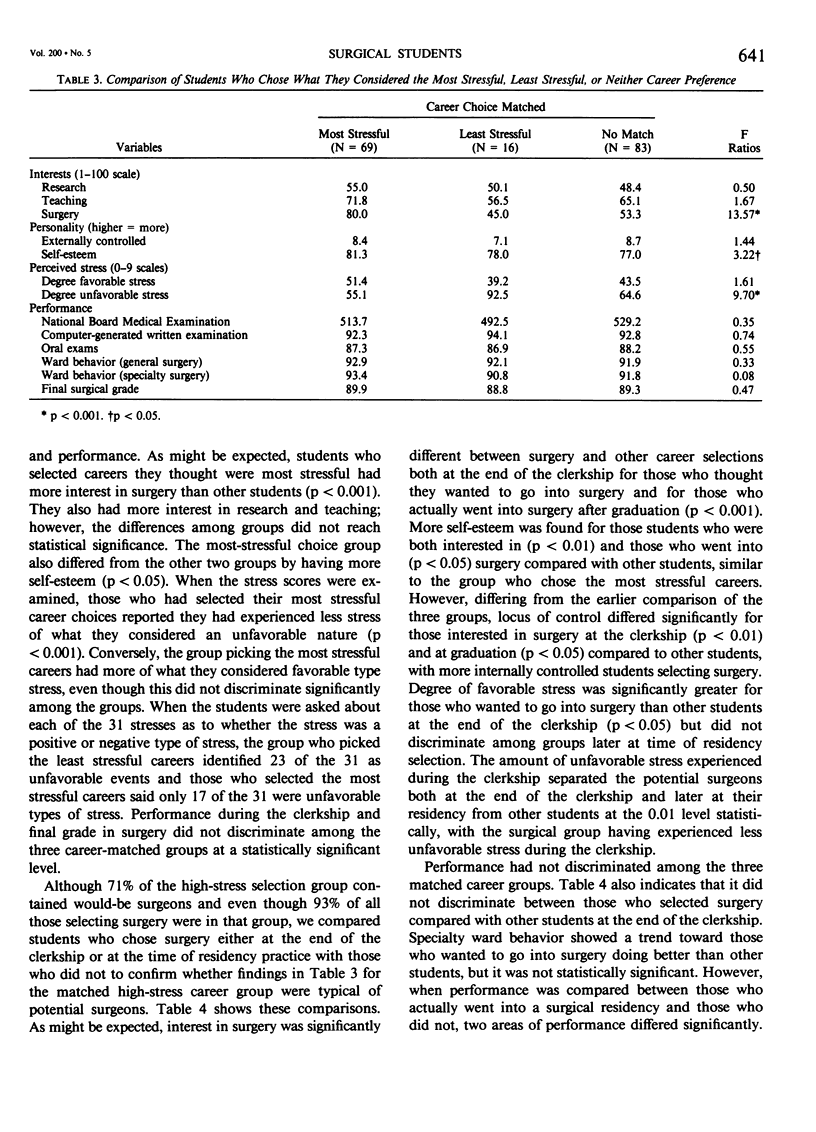

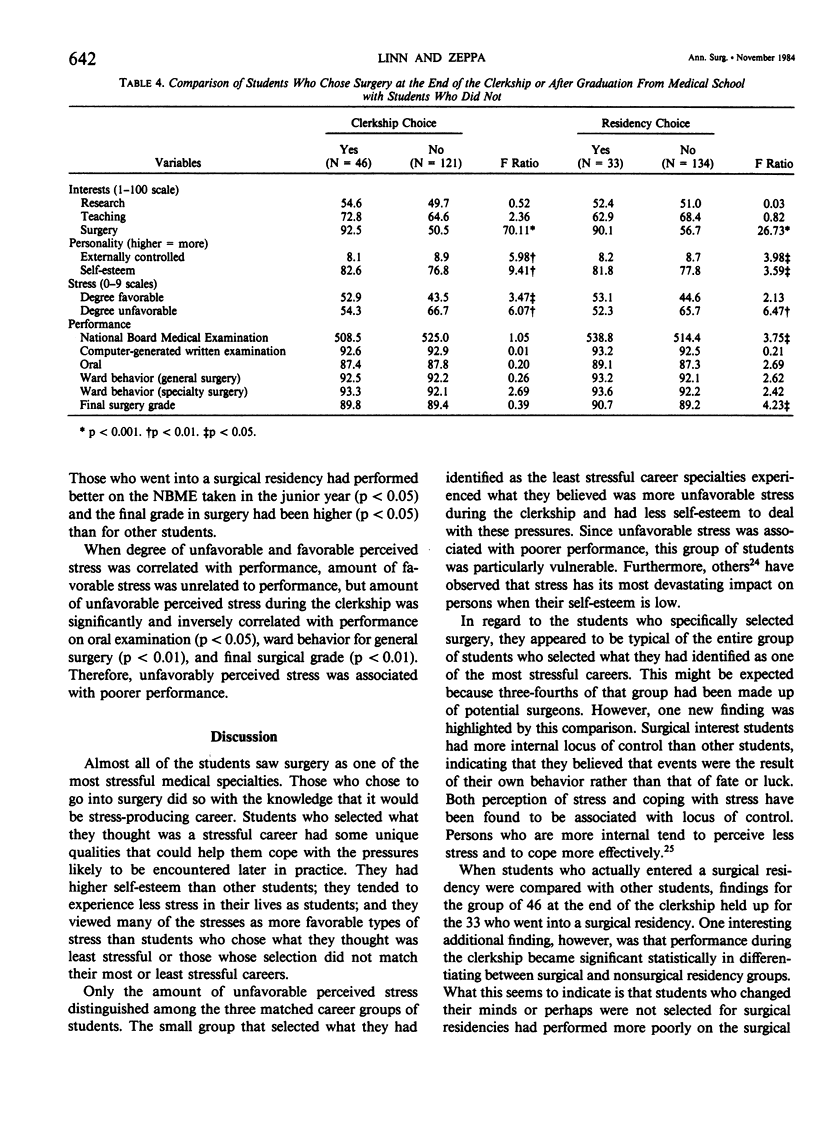

This article examines perceptions of stress and career choice. One hundred sixty-nine junior students specified what they thought were the two most and two least stressful careers, as well as their own career preferences before and after a 12-week surgical clerkship. The class was divided for analysis into three groups: those who selected careers that they said were A) most stressful (42%), B) least stressful (10%), and C) neither most nor least stressful (48%). Surgery was cited as one of the two most stressful choices by 99% of the class before and 93% after the clerkship. The next most stressful career was internal medicine, cited by 43% before and 35% after the clerkship. The two least stressful careers were dermatology and radiology, cited by approximately 50% of the class before and after the clerkship. Those who chose careers that they said were most stressful had significantly higher self-esteem (p less than 0.05), experienced less unfavorable stress themselves as measured by a 31-item stress scale before and after the clerkship (p less than 0.01), and experienced more favorable (in their view) stress (p less than 0.05) than did the other two groups. Reanalysis of data comparing those who selected surgery with those who did not confirmed findings similar to that of the matched high-stress career group. The study suggests that some students may be able to tolerate stress better and in fact, tend to thrive in an environment that they perceive as stressful, and that such students are more likely to go into a surgical career, which they foresee as one of the most stressful that they can enter.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- BRUHN J. G., PARSONS O. A. ATTITUDES TOWARD MEDICAL SPECIALTIES: TWO FOLLOW-UP STUDIES. J Med Educ. 1965 Mar;40:273–280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BUDNER S. Intolerance of ambiguity as a personality variable. J Pers. 1962 Mar;30:29–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1962.tb02303.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ERON L. D. Effect of medical education on medical students' attitudes. J Med Educ. 1955 Oct;30(10):559–566. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huebner L. A., Royer J. A., Moore J. The assessment and remediation of dysfunctional stress in medical school. J Med Educ. 1981 Jul;56(7):547–558. doi: 10.1097/00001888-198107000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilmann P. R., Laval R., Wanlass R. L. Locus of control and perceived adjustment to life events. J Clin Psychol. 1978 Apr;34(2):512–513. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(197804)34:2<512::aid-jclp2270340255>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick D. G., Dubin W. R., Marcotte D. B. Personality, stress of the medical education process, and changes in affective mood state. Psychol Rep. 1974 Jun;34(3):1215–1223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linn B. S., Cohen J., Wirch J., Pratt T., Zeppa R. The relationship of interest in surgery to learning styles, grades and residency choice. Soc Sci Med Med Psychol Med Sociol. 1979 Nov;13A(6):597–600. doi: 10.1016/0271-7123(79)90102-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linn B. S., Schimmel R., Wirch J., Pratt T., Zeppa R. Where National Board Examinations pass and fail in evaluating knowledge of surgical clerks. J Surg Res. 1979 Feb;26(2):97–100. doi: 10.1016/0022-4804(79)90084-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linn B. S., Zeppa R. Stress in junior medical students: relationship to personality and performance. J Med Educ. 1984 Jan;59(1):7–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linn B. S., Zeppa R. Team testing: one component in evaluating surgical clerks. J Med Educ. 1976 Aug;51(8):672–674. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linn B. S., Zeppa R. Values and attitudes related to career preference and performance in the surgical clerkship. Arch Surg. 1982 Oct;117(10):1276–1280. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1982.01380340012004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MODLIN H. C., MONTES A. NARCOTICS ADDICTION IN PHYSICIANS. Am J Psychiatry. 1964 Oct;121:358–365. doi: 10.1176/ajp.121.4.358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCue J. D. The effects of stress on physicians and their medical practice. N Engl J Med. 1982 Feb 25;306(8):458–463. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198202253060805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otis G. D., Weiss J. R. Patterns of medical career preference. J Med Educ. 1973 Dec;48(12):1116–1123. doi: 10.1097/00001888-197312000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paiva R. E., Haley H. B. Intellectual, personality, and environmental factors in career specialty preferences. J Med Educ. 1971 Apr;46(4):281–289. doi: 10.1097/00001888-197104000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin L. I., Lieberman M. A., Menaghan E. G., Mullan J. T. The stress process. J Health Soc Behav. 1981 Dec;22(4):337–356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose K. D., Rosow I. Physicians who kill themselves. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1973 Dec;29(6):800–805. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1973.04200060072011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaillant G. E., Sobowale N. C., McArthur C. Some psychologic vulnerabilities of physicians. N Engl J Med. 1972 Aug 24;287(8):372–375. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197208242870802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimet C. N., Held M. L. The development of views of specialties during four years of medical school. J Med Educ. 1975 Feb;50(2):157–166. doi: 10.1097/00001888-197502000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]