Abstract

Ischemic stroke remains a leading cause of disability and mortality worldwide. Currently, there are no effective therapeutic strategies to promote post-stroke nerve repair and regeneration in clinical practice. Stem cells, characterized by self-renewal and differentiation capabilities, offer insights into the treatment of stroke. Over the past few decades, stem cell therapy has yielded promising results in preclinical and clinical studies for the treatment of ischemic stroke. However, various challenges to the clinical application of stem cell therapy remain. Herein, we review clinical trials of stem cell therapy for different stages of ischemic stroke. Based on this summary, we discussed the issues that need to be considered in future clinical trials, including determining the optimal cell types and doses, ideal transplantation routes and timing, and appropriate assessment methods. Additionally, as neuroimaging plays an increasingly critical role in humans, we elaborate on the application of advanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) techniques in clinical trials. In terms of the future outlook, we discuss technological advances, introducing machine learning in the field of stroke, and using this approach for integrating multi-omics data. These results may provide information for further development of clinical trials in this field and promote the future application of stem cell-based therapy.

Keywords: Stem cells, Ischemic stroke, Clinical trials, Magnetic resonance imaging, Regeneration

Introduction

Stroke is the principal cause of death and long-term disability worldwide [1]. Of these, approximately 87% of stroke cases are ischemic [2]. Ischemic stroke (IS) occurs when the blood supply is interrupted by the occlusion of cerebral arteries, causing symptoms of neurological deficits such as hemiparesis, speech disorders, dizziness, headache, and dysphagia. Currently, the effective treatments for IS include recanalization therapies, specifically systemic thrombolysis and mechanical thrombectomy. However, the limited time window and risk of hemorrhagic transformation restrict their clinical application. Only a small proportion of patients could benefit from it [3]. Although hundreds of neuroprotective drugs have provided promising preclinical evidence, none have been successfully converted to clinical application [4, 5]. Hence, there is an urgent need for emerging treatment strategies with a broader time frame and less invasiveness.

At present, there are no effective interventions to promote tissue repair after stroke. Regenerative approaches based on cell therapies offer opportunities to mitigate ischemic injury and facilitate functional restoration. Numerous preclinical studies have shown that stem cell therapy could improve neurological recovery in animal models of IS [6, 7]. The beneficial effects involve paracrine effects, immunomodulatory effects, angiogenesis, neurogenesis, and possibly cell replacement [8, 9]. These mechanisms help reconstruct neural circuits and improve neurological function [10]. Considering this encouraging preclinical evidence, a wave of human translation is rapidly emerging. In 2005, Bang and his colleagues transplanted autologous mesenchymal stem cells into five patients with IS for the first time. The results of the study demonstrated improved neurological function and a favorable safety profile [11]. Subsequently, numerous clinical trials have been conducted to explore the safety and efficacy of stem cell therapy for IS, using different cell types, doses, administration routes, and assessment methods at different stages of IS [12]. Although stem cell therapy is generally safe, efficacy outcomes in clinical trials have been inconsistent [13]. Moreover, many issues remain unresolved, such as the effective dose, the best route, the most suitable cell type, the appropriate time of transplantation, and accurate assessment methods. These differences in design make it difficult to assess the results of clinical trials. Therefore, well-designed research protocols are essential for randomized clinical trials to evaluate functional outcomes.

As emphasized in the Stem Cell Therapy as an Emerging Paradigm for Stroke (STEPS) II publications, there is an urgent need for biomarkers to assess the efficacy of stem cell therapy [14]. Neuroimaging has been at the forefront of human research on cell-based therapy. Currently, neuroimaging techniques are utilized in animal and human studies in the field of stem cell therapy. These studies indicated that stem cell therapy might lead to plasticity changes at the synaptic or neuronal levels, and multimodal MRI techniques help provide objective data on the efficacy and mechanisms [6, 15, 16]. Commonly used imaging sequences mainly include T1 structural imaging focusing on macroscopic morphologic changes; diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) focusing on white matter microstructural integrity; functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) focusing on functional connectivity; and magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) focusing on metabolite changes, as well as other imaging sequences [17]. These imaging modalities complement each other and play a crucial role in clinical research. In this review, we provide an overview of clinical trials on stem cell therapy for IS. Subsequently, we summarize the advanced MRI techniques applied to these clinical trials and discuss technological advances. We aim to enable researchers to fully understand the progress and challenges of current clinical trials and provide directions for future research.

Pathophysiology of ischemic stroke and potential mechanisms of stem cell therapy for ischemic stroke

Ischemic stroke occurs due to a sudden interruption of blood supply to the brain, leading to a cascade of molecular events that cause neuronal injury and death. The initial molecular events involve impaired cerebral perfusion, resulting in acute oxygen and glucose deprivation [18]. Hypoxic conditions reduce adenosine triphosphate (ATP) production, leading to ion pump dysfunction and membrane depolarization accompanied by a large influx of Ca2+ and Na+ and an efflux of K+ [18]. These phenomena may initiate a cascade of pathophysiological events, such as excitotoxicity, oxidative stress, calcium overload, mitochondrial dysfunction, and inflammation [19]. These processes interact synergistically to activate various cellular signaling pathways, ultimately resulting in neuronal necrosis and apoptosis [19]. In the acute phase, the neuroinflammation, the disruption of the blood–brain barrier, and the apoptosis of neuronal cells may affect functional outcomes. While in the subacute to chronic phase, the main damaging factors include persistent neuroinflammation, disruption of neural circuits, and formation of glial scars [20].

Many researchers have sought to elucidate the mechanisms of stem cell therapy for IS, and several summary reviews have been published [20–22]. Briefly, the beneficial effects of stem cells are mediated through various mechanisms, predominantly involving cell replacement, paracrine effects, and other aspects, such as promoting mitochondrial transfer [23]. Transplanted stem cells can not only differentiate into various cells to replace lost cells and integrate into the host neural circuit, but also secrete various bioactive molecules to regulate the inflammatory microenvironment, inhibit cell apoptosis, and promote angiogenesis and neurogenesis [24, 25]. Currently, MSCs are the most widely studied cell type for the treatment of IS. Increasing evidence suggests that the primary therapeutic benefits of MSCs lie in their paracrine actions [26]. However, these benefits decline with aging. Prolonged ex vivo cell culture of MSCs from aging donors shows a senescent phenotype, and reduced proliferation and differentiation capacity [27, 28]. Several mechanisms have been implicated in MSCs senescence, primarily including telomere shortening [29], impaired autophagy [30], and mitochondrial dysfunction [31]. A previous study has shown that the paracrine actions of MSCs are tightly regulated by the telomere-associated Rap1/NF-κB signaling pathway [32]. Deletion of Rap1 leads to impaired immunomodulatory function in MSCs. Given the potential of paracrine function, researchers consistently pursue to enhance the paracrine ability of stem cells and maximize their therapeutic advantages. In addition to the above mechanisms, MSCs can also promote neurological recovery through mitochondrial transfer. Transferring healthy mitochondria to damaged cells in ischemic regions is a promising therapeutic strategy [33]. Accumulating evidence suggests that stem cells can serve as mitochondrial donors to maintain mitochondrial balance [34]. Previous studies have shown that mitochondrial donation by MSCs not only directly repairs cellular damage but also protects injured cells by regulating macrophage function [35, 36]. Furthermore, exogenous stem cells can also promote endogenous neurogenesis. Generally, there are three actions of exogenous stem cells on endogenous stem cells [37]. First, exogenous stem cells can stimulate the proliferation of endogenous stem cells by secreting cytokines, growth factors, and exosomes, and through intercellular contacts. Second, they create a “biobridge” that recruits endogenous stem cells to the injured area. Finally, exogenous stem cells can indirectly modify the ischemic microenvironment through immunomodulation and angiogenesis, thereby promoting the survival and differentiation of endogenous stem cells. Increasing evidence suggests that the mechanisms of stem cell therapy for IS may vary depending on the stage of stroke [38]. Cell transplantation during the acute phase of stroke may promote neuroprotection owing to its ability to secrete multiple bioactive molecules through paracrine effects [39]. Conversely, the implantation of cells in the subacute and chronic phases is more concerned with neuronal repair and promotion of neuroplasticity [40].

Clinical trial of stem cell therapy for ischemic stroke

A search of the Clinical Trials databases for studies was performed using the following search terms: “stem cells” and “ischemic stroke”. Sixty-eight studies for IS have been registered on clinicalTrials.gov as of June 2, 2024, twenty-six of which have been completed and published. Meanwhile, some studies not registered on the website were completed and published on PubMed, which might provide referential results. We conducted further searches on PubMed with the key MeSH terms: “ischemic stroke” and “stem cells” or “mesenchymal stem cells” (MSCs) or “endothelial progenitor cells” (EPCs) or “neural stem cells” (NSCs) or “hematopoietic stem cells” (HSCs) or induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) or embryonic stem cells (ESCs) or “peripheral blood stem cells” (PBSCs) or “bone marrow cell transplantation”. The article type was restricted to “clinical trial”. Clinical research articles focusing on stem cell therapy for IS published in English were included. Ultimately, a total of eighteen additional articles were included. As a result, a total of forty-four published clinical trials were retrieved. Finally, details regarding the study design, cell type, dose, route, timing, and functional outcome were obtained from the full-text papers. Below, we describe the findings of stem cell therapy for IS based on different phases [41] (Table 1).

Table 1.

Overview of published clinical trials investigating stem cell-based therapy in ischemic stroke patients

| Author/Year | Study design/Phase | Cell type | Dose/single(S) or multiple(M) | Route | Timing | Enrollment (control) | Follow-up | Functional outcome indicator | Results/References | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acute phase | |||||||||||

| Hess, 2017 (MASTER) | RCT/II | MAPCs/Allo | 400, 1200 × 106/S | IV | 24–48 h | 65 (61) | 12 M | NIHSS, mRS, BI | Safe and well tolerated; No significant improvement for neurological recovery at the primary endpoint, but earlier timing (24–36 h) may be beneficial [42] | ||

| Houkin, 2024 (TREASURE) | RCT/II/Ⅲ | MAPCs/Allo | 1.2 × 108/S | IV | 18–36 h | 104 (102) | 12 M | NIHSS, mRS, BI | Safe but did not improve short-term outcomes; Specific patients with large infarct volumes or younger patients may be beneficial [43] | ||

| Laskowitz, 2018 (CoBIS) | Non-RCT/I | UCBCs/Allo | 0.83–3.34 × 107/kg/S | IV | 3–9D | 10 | 12 M | NIHSS, mRS, BI | Safe; Improvements in functional outcome were observed by 3 months postinfusion [44] | ||

| Laskowitz, 2024 (CoBIS 2) | RCT/II | UCBCs/Allo | 0.5–5 × 107/kg/S | IV | 3–10 D | 50 (27) | 3 M |

NIHSS, mRS, BI SF-36, TICS |

Safe but the primary efficacy endpoint did not demonstrate benefit [45] | ||

| De Celis-Ruiz, 2022 (AMASCIS) | RCT/IIa | ADSCs/Allo | 1 × 106/kg/S | IV | ≤ 2W | 4 (9) | 2Y |

NIHSS, mRS BDNF, VEGF |

Safe and well tolerated; the ADSCs group showed a nonsignificantly lower NIHSS score [46] | ||

| Vahidy, 2019 (SIVMAS) | Non-RCT/I | BMMNCs/Auto | 5–10 × 106/kg/S | IV | 1–3D | 25 | 2Y | NIHSS, mRS, BI, MRI | Safe and feasible [47] | ||

| Taguchi, 2015 | Non-RCT/I/IIa | BMMNCs/Auto | 2.5–3.4 × 108/S | IV | 7–10D | 12 | 6 M |

NIHSS, mRS, BI SPECT, PET |

Safe and feasible; Better neurologic recovery and improvement in cerebral blood flow and metabolism [48] | ||

| Savitz, 2011 | Non-RCT/I | BMMNCs/Auto | 4–6 × 108/S | IV | 1–3D | 10 | 6 M | NIHSS, mRS, BI | Safe and feasible; Clinical improvements [41] | ||

| Lee, 2021 | Non-RCT/I | UCB-MNCs/Allo | 0.5–5 × 107/kg/S | IV | 3–10D | 1 | 12 M | NIHSS, BI, MRI | Safe and significantly recovered within a short period [49] | ||

| Moniche, 2012 | Non-RCT/I/II | BMMNCs/Auto | 1.59 × 108/S | IA | 5–9D | 10(10) | 6 M | NIHSS, mRS, BI | Feasible and safe; No significant differences in neurological function [50] | ||

| Moniche, 2023 (IBIS) | RCT/II | BMMNCs/Auto | 2, 5 × 106/kg/S | IA | 1–7D | 39 (38) | 6 M | NIHSS, mRS, BI, MRI | Safe; No significant improvement at 180 days on the mRS [51] | ||

| Friedrich, 2012 | Non-RCT/I | BMMNCs/Auto | 5.1 × 107–6 × 108/S | IA | 3–10D | 20 | 6 M | NIHSS, mRS | Safe and feasible [52] | ||

| Banerjee, 2014 | Non-RCT/I | CD34 + stem cells/Auto | 1 × 108/S | IA | ≤ 7D | 5 | 6 M | NIHSS, mRS, MRI | Safe; Improvements in clinical scores and reductions in lesion volume [53] | ||

| Baak, 2022 (PASSIoN) | Non-RCT/I | BMSCs/Allo | 45–50 × 106/S | IN | ≤ 7 D | 10 | 3 M | MRI | Feasible and safe [54] | ||

| Subacute phase | |||||||||||

| Bang, 2005 | RCT/I/II | BMSCs/Auto | 5 × 107/M | IV | 1–2 M | 5 (25) | 12 M | NIHSS, mRS, BI | Feasible and safe; Better functional recovery [11] | ||

| Lee, 2010 (STARTING) | RCT/I/II | BMSCs/Auto | 5 × 107/M | IV | 1–2 M | 16 (36) | 5Y | Survival, mRS, MRI | Feasible and safe; Improve functional recovery [55] | ||

| Lee, 2022 (STARTING-2) | RCT/II | BMSCs/Auto | 1 × 106/kg/S | IV | ≤ 90D | 39 (15) | 3 M |

mRS, FMA, MI, FAC MEP, MRI |

Feasible and safe; Leg motor improvement was observed [56] | ||

| Jaillard, 2020 (ISIS-HERMES) | RCT/I/IIa | BMSCs/Auto | 1, 3 × 108/S | IV | 1–2 M | 16 (15) | 2Y | BI, NIHSS, mRS, FM, fMRI | Safe; Significant improvements in motor-NIHSS, motor-Fugl-Meyer scores [57] | ||

| Prasad, 2014 | RCT/II | BMSCs/Auto | 2.8 × 108/S | IV | 7–30 D | 58 (60) | 1Y |

NIHSS, mRS, BI MRI, EEG, PET |

Safe; No beneficial clinical outcome [58] | ||

| Fang, 2019 | RCT/I/IIa | EPCs,BMSCs/Auto | 2.5 × 106/kg/M | IV | 4–6W | 12 (6) | 4Y | NIHSS, mRS, BI, SSS | Feasible and safe; EPCs appear to improve long-term safety [59] | ||

| Niizuma, 2023 | RCT/II | Human Muse cells/Allo | 1.5 × 107/S | IV | 2–4W | 25 (10) | 52W | NIHSS, mRS, BI, FMMS | Safe and effective [60] | ||

| Honmou, 2011 | Non-RCT/I | BMSCs/Auto | 0.6–1.6 × 108/S | IV | 36–133D | 12 | 12 M | NIHSS, MRI | Feasible and safe [61] | ||

| Bhatia, 2018 | RCT/I/IIa | BMMNCs/Auto | 6.1 × 108/S | IA | 1W-2W | 10 (10) | 6 M | NIHSS, mRS, BI | Safe; Improved clinical outcomes [63] | ||

| Savitz, 2019 (RECOVER-Stroke) | RCT/II | BMMNCs/Auto | 1.6 × 105–7.5 × 107/S | IA | 2–3W | 29 (19) | 1Y | NIHSS, mRS, BI | Safe, but no significant differences in efficacy measures [62] | ||

| Battistella, 2011 | Non-RCT/I | BMMNCs/Auto | 1–5 × 108/S | IA | 2–3 M | 6 | 6 M |

NIHSS, mRS, BI MRI, SPECT |

Feasible and safe [64] | ||

| Jiang, 2013 | Non-RCT/I | UMSCs/Allo | 2 × 107/S | IA | 11–22D | 3 | 6 M | Muscle strength, mRS | Feasible and safe; Improved neurological function [65] | ||

| Ghali, 2016 | Non-RCT/I/IIa | BMMNCs/Auto | 1 × 106/S | IA | 1W–3 M | 21 (18) | 12 M | NIHSS, mRS, BI, MRI | Safe, but no significant functional improvement [66] | ||

| Chronic phase | |||||||||||

| Chen, 2014 | RCT/II | CD34 + PBSCs/Auto | 3–8 × 106/S | IC | 6 M–5Y | 15 (15) | 12 M |

NIHSS, ESS, mRS MRI, TMS |

Safe and feasible; Improved clinical outcomes [67] | ||

| Kalladka, 2016 (PISCES) | Non-RCT/I | Human NSCs (CTX0E03)/Allo | 2–20 × 106/S | IC | 6 M–5Y | 11 | 2Y | NIHSS,mRS, BI, Ashworth scale, MRI | Feasibility and safety; Neurological function was improved at 24 months [68] | ||

| Muir, 2020 (PISCES-2) | Non-RCT/II | Human NSCs (CTX0E03)/Allo | 2 × 107/S | IC | 2 M–13 M | 23 | 12 M | ARAT, mRS, BI, FM | Improvements in upper limb function [69] | ||

| Kondziolka, 2000 | Non-RCT/I | Human neuronal cells (NT2N)/Allo | 2, 6 × 106/M | IC | 6 M–6 | 12 | 18 M |

NIHSS, ESS, BI, SF-36 MRI, PET |

Safe and feasible; A trend toward improved scores in the group of patients who received 6 million neuronal cells [70] | ||

| Kondziolka, 2005 | RCT/II | Human neuronal cells (NT2N)/Allo | 5, 10 × 106/S | IC | 1–6Y | 14 (4) | 12 M |

NIHSS, ESS, FM ARAT, SF-36, MRI |

Safe and feasible; No difference at the primary endpoint, but partial recovery in ARAT [71] | ||

| Savitz, 2005 | Non-RCT/I | Fetal porcine cells/Xeno | 2 × 107/S | IC | 1.5Y–10Y | 5 | 24 M | NIHSS, mRS, BI | Mild recovery, but 2 patients experienced adverse events (seizures and motor deficits) [73] | ||

| Steinberg, 2018 | Non-RCT/I/IIa | BMSCs (SB623)/Allo | 2.5–10 × 106/S | IC | 6 M–60 M | 18 | 2Y | ESS, NIHSS, mRS, FM | Safe and was accompanied by improvements in clinical outcomes [72] | ||

| Zhang, 2019 | Non-RCT/I | Fetal spinal cord-derived NSCs (NSI-566)/Allo | 1.2, 2.4, 7.2 × 107/S | IC | 3 M–24 M | 9 | 24 M |

NIHSS, mRS, FMMS, MRI, PET |

Safe and feasible; Improved clinical outcomes [74] | ||

| Chiu, 2022 | Non-RCT/I | ADSCs(GXNPC1)/Auto | 1 × 108/S | IC | 6 M–10Y | 3 | 6 M | NIHSS, BI, FM, SSEP, BBS | Safe and improvement for neurological measures [75] | ||

| Wang, 2013 | Non-RCT/I | CD34 + stem cells/Auto | 0.8–3.3 × 107/M | IT | 1Y–7Y | 8 | 12 M | NIHSS, BI | Safe [76] | ||

| Sharma, 2014 | Non-RCT/I | BMMNCs/Auto | 1 × 106/kg/S | IT | 4 M–144 M | 24 | 6 M–4.5Y | FIM, PET | Safe and feasible; Accelerating the functional recovery [77] | ||

| Qiao, 2014 | Non-RCT/I | NSPCs and MSCs/Allo | 0.5–6 × 106/kg/S | IV/IT | 1W–2Y | 6 | 2Y | NIHSS, mRS, BI | Safe and feasible; Improved neurological function [78] | ||

| Bhasin, 2011 | Non-RCT/I | BMSCs/Auto | 5–6 × 107/S | IV | 3 M–1Y | 6 (6) | 6 M |

FM, mBI, MRC, MRI Ashworth scale |

Safe and feasible; The FM and mBI showed a modest increase in the MSC group [79] | ||

| Bhasin, 2012 | Non-RCT/I | BMMNCs/Auto | 5.46 × 107/S | IV | 3 M–2Y | 12 (12) | 6 M | FM, mBI, MRI | Safe and feasible; Improvement in clinical and fMRI scores till 24 weeks [16] | ||

| Bhasin, 2013 | Non-RCT/I/II | BMSCs/BMMNCs/Auto | 5–6 × 107/S | IV | 3 M–2Y | 20 (20) | 6 M |

FM, mBI, MRC, MRI Ashworth scale, |

Safe and feasible; mBI showed significant improvement in the MSC group [80] | ||

| Bhasin, 2016 | RCT/I/II | BMMNCs/Auto | 6–7 × 107/S | IV | 3 M–18 M | 10 (10) | 12 M |

FM, mBI, MRC Ashworth scale |

Safe; No significant differences in neurological function [81] | ||

| Levy, 2019 | Non-RCT/I/II | BMSCs/Allo | 0.5–1.5 × 106/S | IV | ≥ 6 M | 36 | 1Y | NIHSS, BI, MMSE | Safe and behavioral gains [82] | ||

BMMNCs, bone marrow mononuclear cells; BMSCs, bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells; EPCs, endothelial progenitor cells; NSCs, neural stem cells; NPCs, neural progenitor cells; NSPCs, neural stem/progenitor cells; ADSCs, adipose tissue derived mesenchymal stem cells; MAPCs, multipotent adult progenitor cells; UCB, umbilical cord blood; UMSCs, umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells, PBSCs, peripheral blood stem cells; Muse cells, Multilineage-differentiating stress-enduring cells; Allo, allogeneic; Auto, autologous; Xeno, xenogeneic; RCT, randomized controlled trial; IV, intravenous; IA, intra-arterial; IC, intracerebral; IT, intracerebroventricular; IN, intranasal; NIHSS, National Institute of Health Stroke Scale; mRS, modified Rankin Scale; BI, Barthel Index; mBI, modified Barthel Index; ESS, European stroke scale; FMA, Fugl-Meyer assessment; MI, motricity index; FAC, functional ambulatory category; ARAT, action research arm test; FMMS, Fugl-Meyer motor total score; MRC, medical research council; BBS, berg balance test; SF-36, 36-item short form survey; FIM, functional indenpendence measure; MEP, motor evoked potential; SSEP, somatosensory evoked potential; PET, positron emission tomography; MMSE, minimum mental state examination

Overview of clinical trial in the acute phase

The acute phase is usually one week after stroke onset, and a total of fourteen published clinical studies were retrieved in this stage. Among these studies, BMMNCs were the most frequently used cell type, appearing in six studies, while multipotent adult progenitor cells (MAPCs), umbilical cord blood stem cells (UCBCs), bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells (BMSCs), and adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells (ADSCs) were also applied. The transplantation methods included intravenous administration (IV) with nine articles, intra-arterial administration (IA) with four articles, intranasal administration (IN) with one article, not involving intrathecal injection (IT), and intracerebral injection (IC). After an acute stroke, IV administration provided considerable cell counts of up to 109 cells. Eight single-arm studies with small sample sizes lacked control groups. The research results suggested that the stem cells were safe in patients with acute ischemic stroke (AIS) and showed a certain degree of functional improvement over baseline. However, due to the spontaneous recovery nature of IS, it is necessary to introduce a control group in the study design and draw valid conclusions through statistical analysis methods. After searching, a total of six studies included control groups (NCT00761982, NCT02178657, NCT01436487, NCT01678534, NCT02961504, and NCT03004976). Below, we briefly describe these representative clinical studies conducted during the acute phase.

In a phase 1/2 trial involving 20 patients (NCT00761982), 20% of patients in the BMMNC group had a favorable outcome, compared to 0% in the control group [50]. Based on this pilot study, Moniche’s research team conducted a phase 2, randomized, controlled, and multicenter trial to test the efficacy of BMMNCs in AIS patients (NCT02178657) [51]. The result suggested that intra-arterial BMMNCs did not demonstrate favorable outcomes at 180 days in the primary endpoint, but there was a possibility of improving outcomes through secondary and post hoc analyses. The MultiStem in Acute Stroke Treatment to Enhance Recovery Study (MASTERS) trial (NCT01436487) included a total of 126 patients. 65 patients received up to 1.2 billion MAPCs intravenously, and 61 patients received a placebo within 48 h after stroke onset. There was no difference in primary outcome indicators, but exploratory analysis showed that early timing (< 36 h) may be beneficial [42]. The reasons for this phenomenon remain uncertain but may be related to reducing secondary inflammatory responses and providing a better immune microenvironment for brain recovery [83–85]. MASTERS-2 (NCT03545607), a Phase Ⅲ clinical trial of MultiStem for IS with an earlier time window (< 36 h), is currently being conducted by Athersys. This study will include younger participants and a larger enrollment. The Treatment Evaluation of Acute Stroke Using Regenerative Cells (TREASURE) trial (NCT02961504), another study applying MultiStem in AIS patients, was recently published [43]. In this phase II/Ⅲ study of 206 patients, doses of 1.2 billion cells administered between 18 and 36 h after stroke onset did not improve short-term function results in either primary or secondary endpoints. Exploratory subgroup analyses showed that MultiStem therapy for IS was beneficial in specific populations, such as individuals younger than 64 years or with infarct volumes greater than 50 mL. Additionally, exploratory post hoc analyses revealed a better trend in function outcomes after one year, consistent with findings from the MASTERS trial [42]. These findings suggest that stem cell therapy differs from conventional neuroprotective treatments, as the potential repair mechanisms of stem cells involve modulation of the immune microenvironment and promotion of nerve regeneration and repair, potentially facilitating long-term functional recovery [86]. Therefore, a long-term follow-up period is essential for efficacy assessment. Two other RCTs using UCBCs and ADSCs demonstrated improvements in functional outcomes compared to baseline, but no significant difference in neurological function scores was obtained between the two groups (NCT03004976, NCT01678534) [44, 46].

In conclusion, the above findings suggest that stem cell therapy is safe and feasible for acute-phase patients. Although there is heterogeneity in clinical efficacy, the overall trend is favorable. Notably, the MASTER trial applied the highest cell dose (up to 109 cells) and the most immediate time to transplantation (< 48 h). This suggests that future clinical studies are still needed to further optimize cell dose, time, route, cell type, and subject enrollment criteria. The clinical translational considerations, including these factors, were initially discussed at the STEPS meeting to develop consensus recommendations for future study designs [14, 87]. In addition, there remains a lack of clarity regarding stem cell paracrine effects and interactions between different mechanisms. Further basic research is required for further clarification [88].

Overview of clinical trials in the subacute phase

The subacute phase is usually defined as one week to six months after stroke onset. A total of thirteen published clinical studies of stem cell therapy for subacute ischemic stroke were retrieved. Of these, autologous BMMNCs and BMSCs were the primary cell types studied. The transplantation routes were predominantly IV with eight articles, and IA with five articles. There was a notable variation in cell dosage, ranging from 1.6 × 105 to 6.1 × 108 [62, 63]. Regarding the findings, single-arm studies with small sample sizes not only confirmed safety but also showed supportive efficacy results for stem cell therapy in subacute ischemic stroke. However, randomized controlled studies with expanded sample sizes exhibited heterogeneity in efficacy.

In 2005, Bang’s research team conducted a groundbreaking clinical study on stem cell therapy for IS. The study included five experimental and twenty-five control subjects between weeks five and seven after IS, with a one-year follow-up. The preliminary data showed that intravenous administration of BMSCs was safe for subacute IS [11]. The trial was randomized and controlled and is considered a milestone in this field. In 2010, the same research group reported the results of the Stem Cell Application Researches and Trials in Neurology (STARTING) trial, a randomized, controlled, observer-blinded clinical trial that included fifty-two patients between weeks five and seven after stroke with a five-year follow-up. To our knowledge, this is one of the longest-lasting trials demonstrating the long-term safety and functional efficacy of stem cell therapy, although there is a suggestion to shorten the administration time [55]. More recently, the STARTING-2 (NCT01716481) trial showed that MSC treatment improved lower limb motor function in subacute stroke patients in the secondary efficacy endpoint with no obvious adverse effects [89]. Many factors could influence the motor recovery of stroke patients, so the research group further completed a post hoc analysis of this clinical study. The research findings indicated that the factors related to the response to MSC treatment were the time from stroke onset to treatment and the patient’s age [90]. Furthermore, the STARTING-2 trial also demonstrated for the first time that MSC treatment significantly increased circulating extracellular vesicles in IS patients, which were strongly linked to improvements in motor function and MRI parameters of plasticity [91]. In addition to the studies mentioned above, three RCT studies conducted by Bhatia, Jaillard, and Niizuma demonstrated improved clinical outcomes [57, 60, 63]. Almost no differences were seen across groups at this stage of stroke by other researchers [58, 59, 62].

In the subacute phase, it is much more difficult to draw specific conclusions due to different treatment-related parameters. The STARTING-2 series of trials indicated that MSC therapy had limitations in subacute IS, despite efforts to enhance its efficacy. The optimal timing and appropriate population for stem cell therapy in IS may be further investigated based on neuroplasticity mechanisms.

Overview of clinical trials in the chronic phase

Cell transplantation six months after stroke onset is defined as chronic phase treatment. Eleven published clinical studies were retrieved during this period. Due to the clinical stability of chronic stroke, more innovative cell types were selected, such as immortalized human neural stem cell line (CTX0E03), modified bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells (SB623), immortalized cell lines Ntera2/D1 Neuron-Like Cells (NT2N), and primary adherent human NSC line (NSI-566). These modified cell lines are characterized by high proliferative capacity and good environmental adaptation. However, issues such as genetic stability and tumorigenesis remain concerns. The transplantation routes employed in this phase predominantly included intracerebral (IC) with nine articles, as well as intrathecal (IT) with three and intravenous (IV) with five. Most studies using IC transplantation adopted an open-label design due to the challenges associated with conducting a placebo intervention. Moreover, only one of the nine studies established a control group [67]. Consequently, it is challenging to ascertain whether the observed efficacy is attributable to IC treatments, similar to other clinical trials lacking a control group. Below, I will briefly describe the clinical studies of stem cell interventions in chronic patients under different transplantation methods.

IC transplantation: Chen et al. conducted a randomized controlled trial involving thirty patients who were followed for one year. The results indicated that IC infusion of autologous CD34+ PBSCs was safe and effective in improving neurological function outcomes compared to the control group [67]. In 2016, Kalladka et al. reported the findings of the pilot investigation of stem cells in stroke (PISCES) trial (NCT01151124), demonstrating that IC transplantation of CTXE03 was safe and feasible for chronic stroke patients [68]. During the 24-month follow-up period, there were no adverse events related to cell therapy, and the comorbidities or procedure caused the adverse events. In 2020, the PISCES-2 trial further confirmed the safety and feasibility of CTX0E03 (NCT02117635). In addition, an improvement in arm motor function could be observed in those with residual movement function at baseline [69]. PISCES-3 (NCT03629275) was the continuation of PISCES-2. However, the PISCES-3 trial was forced to terminate owing to the emergence of COVID-19. Future large-scale trials are still necessary. IT transplantation: There were three open-label, single-arm studies applying the IT transplantation methods in patients with chronic-phase stroke. The published data showed that IT injection was safe and facilitated functional recovery in patients with chronic stroke [76–78]. However, the intervention cannot fully explain this phenomenon due to the absence of a control group. IV transplantation: Dr. A. Bashin is one of the authors who has been dedicated to this field. Four articles on intravenous routes for chronic stroke patients have been published. However, the results varied across trials, with some studies reporting significant results compared to controls [16, 79], while others did not [80, 81]. Recently, a meta-analysis provided the first report on functional outcomes and adverse events associated with different administration routes. Evidence suggested that IC administration demonstrated superior clinical efficacy compared to other transplantation routes, but adverse events occur more frequently due to its invasive nature [92]. Therefore, further investigations are necessary, as few original studies directly assess the safety and effectiveness of various administration routes. Additionally, due to the relatively small sample sizes and absence of control groups in chronic phase trials, randomized, controlled, large-scale clinical trials are urgently needed to obtain more reliable evidence.

In conclusion, based on the safety and efficacy data from the aforementioned clinical trials, stem cell therapy offers possibilities for patients with IS at different stages. The priority is to summarize existing studies to improve trial design and treatment-related parameters, thereby promoting the development of standardized and valuable clinical research. This will also provide high-quality evidence to support the application of stem cell therapy in clinical practice.

Issues to be considered in future clinical trials

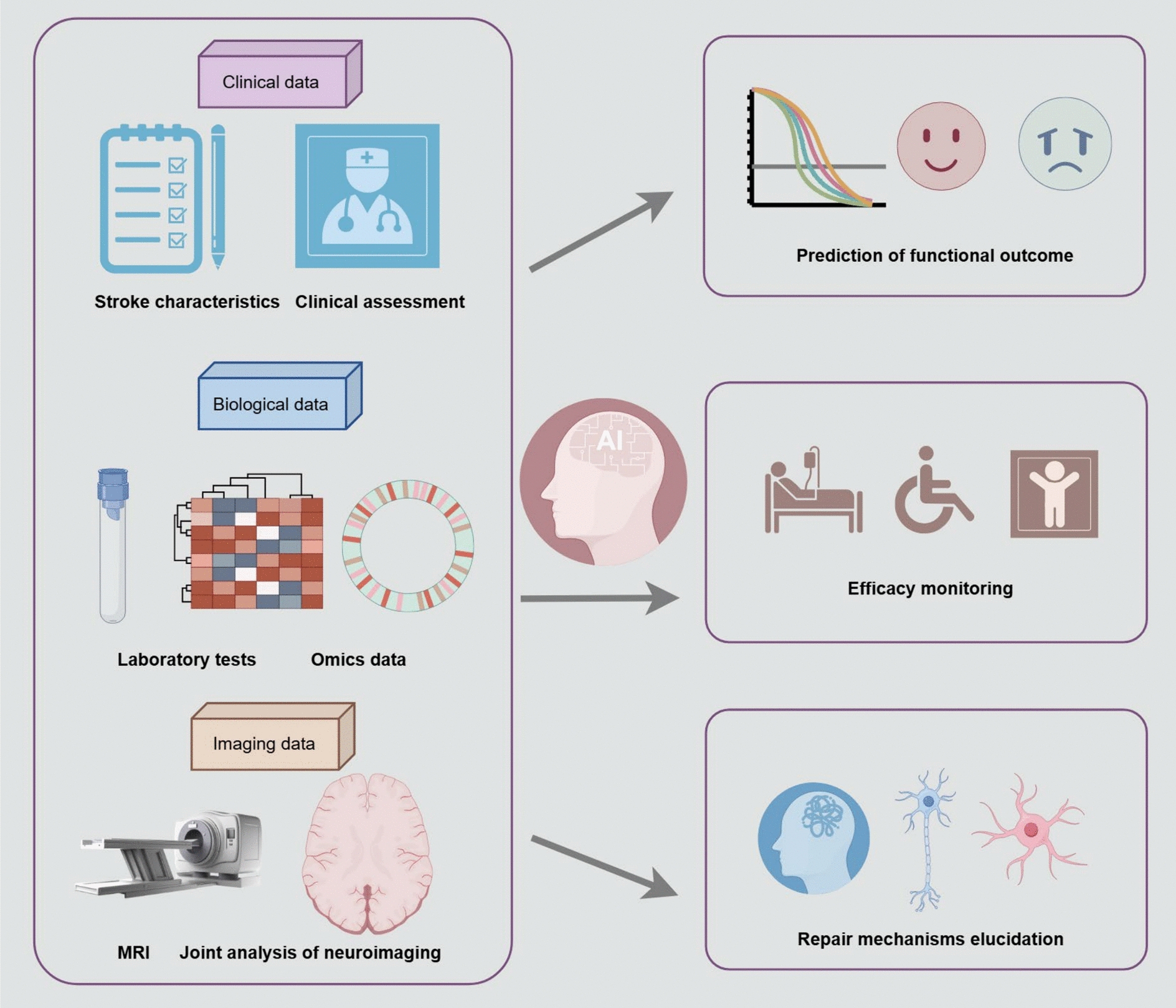

We summarized the design and results of approximately 44 human studies of stem cell therapy for IS with proven safety but heterogeneous effectiveness. Although stem cell therapy for IS has shown promising therapeutic potential, it also raises some issues that must be resolved. The published studies varied regarding cell types, dosages, time windows, routes, and follow-up time (Fig. 1). These studies also had limitations in study designs and assessment methods. These drawbacks highlight the need for more rigorous, large-scale, and multicenter trials to establish reliable, reproducible, and long-term evidence on safety and efficacy. Standardized protocols and more sensitive, objective measures of recovery will help to address these limitations and improve the clinical applicability of stem cells in the treatment of IS. Thus, future studies should comprehensively consider the above issues and summarize a set of recognized clinical trial parameters for stem cell therapy in IS to facilitate large-scale and high-quality research.

Fig. 1.

Different cell source, type, dose, route, and time window of stem cell therapy for ischemic stroke. Published clinical trials vary in terms of cell types, doses, routes, and time windows. Further studies are needed to determine the optimal parameters, including cell type, cell dose, route, and patient characteristics to enable stroke patients to benefit from stem cell therapy. MSCs, mesenchymal stem cells; MNCs, mononuclear cells; NSCs, neural stem cells; HSCs, hematopoietic stem cells; EPCs, endothelial progenitor cells

Cell type

Various cell types have been used in cell therapy for IS patients, with autologous BMMNCs being the most used cell type, followed by autologous BMMSCs. Additionally, several other cell types, such as MAPCs, EPCs, UCBCs, and NSCs, have also been employed. Current clinical studies have shown that different types of stem cells have different therapeutic efficacy, but even the same type of stem cells have different efficacy. Unfortunately, few clinical studies have applied different types of stem cells to the same patient population to compare their effectiveness and safety. Therefore, applying different stem cells in one clinical trial could provide valuable information on the therapeutic efficacy of different stem cells. In addition, pathophysiological changes after stroke are a dynamic process. It also requires the development of therapeutic strategies based on the pathophysiological changes at each stage of IS and the different characteristics of cell types [93].

MSCs remain the most used cell type due to their easy access and multiple neuroprotective mechanisms. However, clinical trials have demonstrated inconsistent outcomes even among MSCs of the same type, which is mainly attributed to factors such as donor characteristics, cell preparation methods, treatment protocols, and patient-specific differences. Among these, donor heterogeneity and batch variability are key factors affecting the efficacy of MSC therapy. MSCs can be isolated from various tissues, including bone marrow, adipose tissue, placenta, and umbilical cord. Although MSCs share similar biological characteristics, these cells from different sources exhibit functional differences [94, 95]. Accumulating evidence indicates that the donor’s gender affects proliferation, differentiation potential, secretome, and therapeutic efficacy [96]. Also, the donor’s age and health status have been shown to impact MSCs’ properties [97, 98]. Even MSCs obtained from the same donor via different separation methods or culture batches may differ in phenotype and function, thereby complicating clinical quality control [99]. Additionally, MSCs have issues like replicative senescence and limited proliferative capacity, which further exacerbate the instability of therapeutic efficacy [31, 100]. The limitations of traditional MSCs have prompted research into alternative cell sources and functional optimization strategies. Notably, human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) have emerged as a promising alternative [101]. Good Manufacturing Practices (GMP)-grade iPSC-MSCs have been successfully applied in clinical trials for the treatment of refractory graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), demonstrating clinical feasibility [102]. In future research, the clinical-grade production of MSCs must adhere to GMP to ensure the provision of safe, reproducible, and efficient “cell drug”. Rigorous quality control and standardized manufacturing procedures are critical before clinical application.

Timing

The timing of treatments such as systemic thrombolysis and mechanical thrombectomy is critical in acute stroke trials, which may also be essential for stem cell-based clinical trials in stroke patients. Determining the optimal time window for stem cell transplantation involves multiple factors, including the neuroinflammatory response, neuroplasticity potential, and the type of stem cells used. In the aforementioned clinical studies, the administration time ranged from 18 h to 10 years post-stroke [43, 75]. The acute phase, typically within a few days after stroke onset, is generally considered the optimal window for transplantation [103]. However, evidence suggests that cell therapy in the subacute or even chronic phase may also be effective [104]. A meta-analysis demonstrated that stem cells administrated in the acute phase yielded better outcomes compared with later time windows [105]. However, this issue has not been thoroughly investigated in either preclinical or clinical studies, and the optimal transplantation window remains to be determined. In current clinical protocols and practice, the timing of transplantation should be guided by a comprehensive assessment of multiple factors.

Dose

The cell doses applied in clinical trials differed widely, ranging from 105 cells (BMSCs) to 109 cells (MAPCs), as shown in Table 1 [42, 82]. Several factors influence the administered cell dose, including cell type, administration route and timing, and clinical trial protocols. Research evidence suggests that the idea of more cells transplanted being more efficacious may be incorrect [103, 106]. Furthermore, excessively high single doses may increase the risk of vascular embolism [107]. Although the dosage of stem cells should not be as great as possible, it is crucial to maintain a specific concentration of stem cells for optimal therapeutic effect. In preclinical studies, neurological function improvements were observed within a dose range of 1 × 105–5 × 106/kg, indicating that the appropriate dose may be involved [108–110]. Notably, there is no standard for the optimal transplantation dose in stem cell therapy for IS, but the concentration of stem cells for transplantation shouldn’t be either too high or too low. Therefore, future research should aim to establish precise dose–response relationships and individualized therapeutic regimens.

Route

Stroke patients enrolled in these clinical trials have a variety of administration routes available to them, including intravenous (IV), intra-arterial (IA), intracerebral (IC), intrathecal (IT), and intranasal (IN) delivery. Intravascular routes (IV and IA) typically require higher cell doses, reaching up to 1.2 × 109 cells [42]. Since the presence of the blood–brain barrier (BBB), only a small portion of stem cells can access the brain parenchyma [111]. Besides the BBB, the cells administered via the peripheral vessels may be trapped within organs due to the first-pass effect, further limiting their homing efficiency to ischemic brain regions [112, 113]. In addition, possible complications may occur, such as pulmonary embolism associated with IV administration or thrombosis and bubble formation related to IA administration [14, 114]. In contrast, IT and IC administration require fewer cells (106–7 cells) due to direct delivery to the target site [68, 69, 77]. However, these invasive methods may cause procedure-related complications, such as infection and hemorrhage [72, 73, 115]. Another promising route is IN administration. IN administration provides a non-invasive approach to bypass the BBB and deliver stem cells to the brain [116]. In animal models, this approach enabled MSCs to migrate directly into the brain within hours, with most cells accumulating in the infarction zone [117]. However, this transplantation approach has been rarely used in clinical trials, except for one study involving MSCs for perinatal arterial ischemic stroke (PAIS) [54]. Therefore, this route still requires further experimental and clinical studies to demonstrate its feasibility, safety, and efficacy.

Although few studies have directly compared the efficacy of transplantation routes across disease phases, IV administration seems to be applicable in the acute and subacute phases, where the inflammatory factors are higher than in the chronic phase [42, 89]. In contrast, IC or IT administration is generally preferred in the chronic phase, where the homing of stem cells may be weaker owing to lower levels of inflammatory signals [68, 69]. Therefore, the choice of transplantation methods may be related to the stability of the patient’s condition, stage-specific pathophysiological mechanisms of IS, as well as safety considerations.

Study design

Regarding published clinical trials, most of the studies were preliminary (phase I or II). Only a minority of trials included a control group. Furthermore, many of the aforementioned studies did not adhere to randomization and blinding criteria. Future study designs must be enhanced to ensure protocol rigor and consistency, where randomization and blinding play a vital role in reducing bias and ensuring the validity of results. Even in small-sample clinical trials, randomization reduces allocation bias, while a triple-blind design (investigators, clinicians, and patients) limits observer bias and mitigates placebo effects [118]. In RCTs, randomization allows confounding variables to be balanced across groups, thereby controlling for confounding factors. Common randomization methods include simple, block, stratified, and dynamic randomization. Additionally, statistical methods like stratified analysis and regression modeling are also crucial strategies to control confounding. Including a control group would enhance the robustness of the results and test the feasibility of the trial. Currently, the majority of published trials were carried out in a single center, except for a few studies [42, 43, 51, 62, 69], but the heterogeneity of multicenter samples helped increase the external validity of data. Specifically, multicenter design enhances external validity of clinical trial data primarily by reducing the effects of regional differences, population heterogeneity, and practice pattern variation on study outcomes. To ensure consistency across sites, standardized operational systems, rigorous researcher training, data quality control systems, and statistical analysis strategies need to be emphasized. Furthermore, most published studies were small sample cohorts (n < 60), and the wide-ranging baseline data reduced the homogeneity of the study cohort. Future protocols should expand the sample size to enhance statistical power and validity. In particular, sample size calculations based on previous trials can help to obtain convincing results. Overall, researchers are expected to design and execute multicenter, large-sample, and randomized controlled clinical trials to provide valuable clinical evidence.

Assessment methods

The outcome indicators mainly include safety and efficacy assessments. The safety evaluation indicators include clinical symptoms and sign changes, laboratory tests, and the occurrence of adverse events. The efficacy evaluation indicators include clinical scale scores and objective examinations. To date, safety indicators have been set as the primary outcome measure for most clinical trials. Only a few studies have set efficacy indicators as the primary outcome measure and demonstrated the effectiveness of the treatment. Regarding the safety outcomes, almost all published clinical trials have demonstrated the safety, except for one trial using xenogeneic fetal porcine cells and experiencing adverse consequences (seizures and motor deficits), leading to the trial’s termination [73]. Adverse events are of great concern in clinical trials. The most reported adverse events included mild fever, headache, and fatigue, which typically resolved without long-term consequences [119]. Serious adverse events, such as seizures and infections, were rare [119]. The clinical application of stem cells may raise additional safety concerns that warrant careful consideration, including immune rejection, tumor formation, and uncontrolled differentiation. For instance, allogeneic cell transplantation can lead to immune rejection [120]. Stem cells, particularly pluripotent types such as embryonic stem cells (ESCs) and induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), may carry a risk of tumorigenesis [121]. Moreover, transplanted cells could differentiate into undesirable tissues, potentially leading to cancerous mutations and stem cell death [122]. Notably, although no clinical trials reported serious complications such as immune rejection or tumor formation during follow-up, their potential severity and negative impact on patients necessitate long-term monitoring. Overall, the evidence suggests that stem cell therapy for IS is relatively safe. In spite of this, most published clinical trials are preliminary studies with small samples and limited follow-up. Multicenter, large-scale, and long-term clinical trials will provide more compelling clinical information about safety issues.

As for the functional outcome measure, although the choice of clinical scales varied in the published studies, the National Institute of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS), modified Rankin Scale (mRS), and Barthel index (BI) were widely applied. However, these scales focus on assessing overall functioning and are yet to be sensitive to some fine-grained changes. Therefore, it is recommended to include more detailed functional assessment scales in future research, such as the Fugl-Meyer Assessment (FMA), Ashworth Scale (AS), Berg Balance Scale (BBS), or cognitive function assessment scale. For example, the FMA primarily assesses post-stroke motor recovery by quantifying joint mobility, movement coordination, and reflex activity, enabling longitudinal tracking of motor function evolution. The AS grades muscle tone and spasticity severity using a 0–4 ordinal grading, providing critical data on spasticity management. The BBS employs 14 functionally anchored tasks to quantify balance maintenance during posture transitions. Cognitive assessment scales like the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) and montreal cognitive assessment (MoCA) evaluate cognitive recovery, covering memory consolidation, executive function, and visuospatial processing abilities. Collectively, these discriminating neurological scales may provide more targeted and sensitive measures of functional recovery after stroke. Nonetheless, clinical scale assessments are somewhat subjective, and errors in manual measurement are inevitable. These limitations of the clinical scales restrict their standardized assessment of efficacy across countries. Thus, researchers have attempted to assess the efficacy by employing other objective assessment modalities, such as brain MRI, motor evoked potentials (MEPs), short latency somatosensory evoked potentials (SSEPs), and positron emission tomography-CT (PET-CT) [48, 67, 75, 89]. Among them, brain MRI is an internationally recognized examination for IS and has been routinely used in clinical practice. Advanced analytical techniques based on structure–function-metabolism MRI sequences can directly measure cortical structure, white matter fiber integrity, functional connectivity, activation patterns, and metabolite levels [123]. Notably, these objective measures can reflect the efficacy of the intervention and the underlying repair mechanisms (see MRI techniques section for details), which may facilitate a better comparison of the results in different clinical trials.

Follow-up time

Long-term follow-up is crucial for evaluating the safety of stem cell therapy in stroke patients and monitoring potential long-term effects. In existing studies, follow-up time typically ranges from about 6 months to 5 years (Table 1). Importantly, safety assessments might necessitate extended follow-up periods to acquire reliable data in clinical trials. Kalladka et al. conducted a phase-1, open-label, dose-escalation trial of IC implantation of CTX0E03 hNSCs [68]. The primary endpoint was safety. Clinical and brain imaging data were collected over 2 years. Brain imaging was performed on days − 56 and − 21, as well as at months 1, 3, 12, and 24. Immunological monitoring included the analysis of HLA class I and class II antibodies against CTXE03 before treatment and at months 1, 3, 6, 12, and 24. In this trial, researchers observed no adverse events in 11 chronic stroke patients following IC implantation of CTXE03. Lee et al. completed a clinical trial with a five-year follow-up to assess the long-term safety of ex vivo cultured MSCs in stroke patients [55]. The researchers monitored long-term adverse effects and immediate reactions after MSCs treatment. Long-term adverse effects included tumor formation (physical examination, plain X-ray, and MRI), abnormal connectivity (newly diagnosed seizures and arrhythmia), and zoonoses (myoclonus, rapidly progressive dementia, or ataxia). Immediate reactions included allergic reactions, local hematoma or infection, and systemic complications (systemic infections, abnormalities in liver and kidney function). The findings indicated that the application of ex vivo cultured MSCs was safe for stroke patients during a 5-year follow-up. Jaillard et al. conducted a 2-year trial involving 31 patients with subacute ischemic stroke to assess the safety and feasibility of intravenous administration of autologous MSCs 1 month after stroke and to explore the efficacy of MSC therapy during a 2-year follow-up period [57]. For safety assessment, MRI was performed at month 24 to detect adverse events like hemorrhage, recurrent stroke, tumor, and inflammation. Consistent with Lee et al.’s findings [55] and recent meta-analysis [124, 125], no tumor formation, pro-inflammatory effects, or other adverse effects related to MSCs were observed. Overall, although early clinical trials indicate that stem cell therapy is safe and feasible for stroke patients, the long-term effects, such as tumorigenicity, immunogenicity, altered biodistribution, or unforeseen long-term complications, remain uncertain. Long-term follow-up studies, incorporating multimodal MRI, immunological evaluations, and extended clinical outcome assessments, are crucial for assessing chronic safety risks and monitoring potential therapeutic outcomes over time.

When developing a clinical trial protocol for stem cell therapy for IS, the stage of stroke, cell type, dosage, route, as well as other practical measures need to be considered (Fig. 1). In the future, large-scale clinical trials can achieve dose-response relationships through dose escalation. Long-term metabolic and structural recovery can also be assessed through multimodal MRI technology and long-term follow-up. In addition, stratified analysis based on large sample sizes can help reveal heterogeneous response mechanisms. Validating these specific aspects will expedite standardized and personalized clinical translation. Several well-protocolled, large-scale clinical trials are underway, and we also look forward to the successful completion of enrollment and publication of study results (NCT03545607, NCT04811651, NCT04093336).

The roles of imaging techniques in stem cell-mediated stroke treatment

Multimodal MRI includes various techniques with different imaging principles and observation focuses. The application of these advanced imaging techniques has expanded the understanding of post-stroke neural plasticity from the perspectives of structure, function, and metabolism. Recently, some quantitative markers have been incorporated into studies to evaluate the efficacy and specific mechanisms of stem cell therapy for IS [126, 127]. In the next section, I will describe the current application of multimodal MRI in stem cell therapy for IS (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Advanced MRI techniques in stem cell-mediated stroke treatment. MRI is an internationally recognized assessment method for ischemic stroke and has been widely used in clinical practice. Advanced MRI techniques can provide comprehensive information on neuroplasticity after stroke from the perspectives of morphology, function, and metabolism. The imaging techniques mainly include VBM focusing on macroscopic morphologic changes, DTI focusing on white matter microstructural integrity, fMRI focusing on brain activity and functional connectivity, MRS focusing on metabolite changes, ASL focusing on cerebral blood perfusion, as well as other imaging sequences. Additionally, MRI-based cell tracking enables real-time, non-invasive monitoring of cell migration, engraftment, survival, differentiation, and treatment efficacy. These imaging modalities complement each other and have proved to play an important role in clinical research. VBM, voxel-based morphological analysis; DTI, diffusion tensor imaging; fMRI, functional magnetic resonance imaging; MRS, magnetic resonance spectroscopy; ASL, arterial spin-labeled perfusion imaging; APT, amide proton transfer; SWI, susceptibility weighted imaging; Multi-NMR, multi-nuclear magnetic resonance; SPIONs, superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles

Structural MRI-T1-weighted imaging

Structural imaging for evaluation of IS is commonly performed with T1-weighted imaging. T1-weighted imaging is usually used to analyze macroscopic indicators such as gray matter volume and cortical thickness. The primary analytical methods include voxel-based morphology (VBM) and surface-based morphometry (SBM) [128]. Among these methods, VBM analysis is the most widely used, allowing for quantitative assessment of gray and white matter volume or density to detect structural changes [17]. VBM analysis may provide objective evidence for neuronal recovery and serve as a reference for investigating the neuropathological mechanisms of cell-based therapy in humans.

Recently, some research suggested that brain structural changes, such as cortical thickness and grey matter volume, were associated with behavior recovery after stroke [129, 130]. Miao et al. found that the gray matter volume (GMV) of the contralateral supplementary motor area significantly increased in IS patients with well-recovered [131]. In another study, they observed GMV changes in the frontal and parietal sensory-motor areas, as well as the hippocampus [132]. Ping et al. conducted an acupuncture study, revealing that acupuncture therapy induces structural reorganization in the frontal lobe and default mode network areas of IS patients, potentially explaining its effects on motor and cognitive function [133]. To date, there are no research results on stem cell therapy for IS using VBM analysis. A recent clinical trial involving cerebral palsy (CP) patients treated with NSCs reported that VBM analysis revealed significantly higher GMVs in the NSCs group compared to controls, particularly in areas associated with language, sensory, visual, social, and emotional processing [134]. Therefore, VBM analysis may be a reliable method for assessing the efficacy and potential pathophysiological mechanisms of stem cell therapy in humans, warranting further exploration in clinical trials of cell-based therapies.

Diffusion MRI-DTI

DTI is an emerging non-invasive neuroimaging technique that mainly evaluates white matter microstructure changes by measuring the Brownian motion of water molecules in brain tissues, providing insights into cellular integrity and pathophysiology [135]. The DTI scalars include fractional anisotropy (FA), mean diffusion (MD), axial diffusivity (AD), and radial diffusivity (RD). FA is a commonly used DTI scalar, serving as a hallmark of axonal integrity, and is highly sensitive to the microstructural integrity changes of fiber bundles [136]. Furthermore, post-processing software allows for the quantification of fiber bundle number and length. In recent years, various DTI post-processing methods have been used to investigate white matter microstructural changes in stroke, including region of interest (ROI) based approach, voxel-based analysis (VBA), automatic fiber quantization (AFQ), and tract-based spatial statistics (TBSS). The ROI-based method remains the most widely used approach in data analysis. With advancements in analytical methods, TBSS and AFQ can provide more information about microstructural damage [135, 137]. With the development of biomarkers in neuroimaging, structural indicators, especially those reflecting corticospinal tract (CST) injuries, emerge as promising biomarkers for post-stroke motor recovery. Regarding motor recovery, two meta-analyses have demonstrated a significant correlation between FA values and limb motor scores in both ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke [138, 139]. The decrease of FA was negatively correlated with the improvement of clinical prognosis and motor function [140]. To date, five clinical studies on stem cell therapy for IS have introduced DTI analysis designed to assess the objective effects of the intervention (Table 2).

Table 2.

The multimodal MRI findings of stem cell-based therapy in ischemic stroke patients

| Author, Year | Cell type | Methodology | MRI technique | Post-processing software | Parameter | Key MRI findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lv et al., 2023 | hNSCs | 3D-T1WI | VBM | FSL software | GMV | The VBM analysis showed a significant increase in gray matter volume in the NSC group compared to the control group [134] |

| Lee et al., 2022 | BMSCs | DTI | TBSS | FSL software | FA | The FA of the CST and PLIC did not significantly decrease in the MSC group, but significantly decreased in the control group [56] |

| Chen et al., 2014 | CD34( +) PBSCs | DTI | ROI-based methods | MedInria | Fiber numbers, FNA scores | DTI imaging analysis showed significant differences in FNA scores for CST at 6 and 12 months in the PBSC group compared with the control group [67] |

| Vahidy et al., 2019 | BMMNCs | DTI | ROI-based methods | DtiStudio software | FA, rFA | FA of CST in the ipsilesional pons was decreased between 1 and 3 months after IS. However, the mean rFA started to increase by 6 months [47] |

| Haque et al., 2019 | BMMNCs | DTI | ROI-based methods | FSL software | FA, rFA, rMD, MD | Patients in the control group had a continued decrease in rFA and an increase in rMD from 1 to 12 months, whereas patients in the MNC group had an increase in rFA and no change in rMD from 3 to 12 months [141] |

| Bhasin A et al., 2012 | BMMNCs | DTI | ROI-based methods | DtiStudio software | FA, fiber number, and length | There were no significant differences in FA ratio, fiber number ratio, and fiber length ratio between the MNC group and control group [16] |

| Bhasin A et al., 2012 | BMMNCs | Task-based fMRI | Task-based analysis | SPM2 software | Laterality index (LI), BOLD activation | The number of cluster activation in Brodmann regions BA 4 and BA 6 was increased in the MNC group compared to the control group [16] |

| Jaillard et al., 2020 | BMSCs | Task-based fMRI | Task-based analysis | SPM12 software | Task-related fMRI activity | Compared with the control group, the MSC group showed a significant increase in task-related fMRI activity in M1-4a and M1-4p [57] |

| Lee et al., 2022 | BMSCs | rs-fMRI |

Seed-based analysis Graph-based analysis |

SPM12 software |

Strength of connectivity Network efficiency and density |

The ipsilesional and interhemispheric connectivity increased significantly in the MSC group, and there was a significant difference in interhemispheric connectivity change between the two groups [56] |

| Haque et al., 2019 | BMSCs | MRS | TARQUIN analyses | TARQUIN software | NAA, Cr, Cho | They found increased NAA concentration within the lesion. More importantly, there was a significant correlation between the ipsilateral NAA level and NIHSS score at 3 M follow-up [141] |

3D-T1WI, three-dimensional T1-weighted images; DTI, diffusion tensor imaging; fMRI, functional magnetic resonance imaging; MRS, magnetic resonance spectroscopy; VBM, voxel-based morphological analysis; TBSS, tract-based spatial statistics technique; ROI-based methods, region of interest-based methods; GMV, gray matter volume; FA, fractional anisotropy; MD, mean diffusivity; rFA, relative FA; rMD, relative MD; FNA, fiber number asymmetry; BOLD, blood oxygen level-dependent; NAA, N-acetylaspartate; Cr, Creatine; Cho, Choline; CST, corticospinal tract; PLIC, posterior limb of the internal capsule

Recently, Lee et al. included neuroimaging measurements in the STARTING-2 trial, including FA values derived from DTI [56]. According to the literature, the FA of the damaged fiber bundle decreased over time owing to Wallerian degeneration [142, 143]. In this study, the FA of the CST and posterior limb of the internal capsule (PLIC) did not significantly decrease in the MSC group but significantly decreased in the control group. This evidence suggests that MSC treatment might regulate the degeneration of damaged fiber bundles caused by IS and facilitate motor recovery. Vahidy’s team demonstrated that infusion of BMMNCs was safe for AIS patients [47]. They further presented a DTI analysis in a subgroup who underwent DTI and found that FA of CST in the ipsilesional pons decreased between one and three months after IS. However, mean rFA increased by six months and was significantly higher than at one month by two years after cellular intervention. The increase in rFA might indicate improved integrity of axons and fibers, suggesting microstructural repair. However, without a control group, the observed changes in white matter microstructure cannot be definitively attributed to MNCs therapy. In another trial on patients with IS receiving CD34 (+) PBSCs, the DTI analysis also showed significant differences in fiber number asymmetry (FNA) scores for CST at six and twelve months in the PBSC group compared with the control group [67]. DTI analysis was also introduced in several other studies, with detailed methods and results presented in Table 2. In summary, DTI is a sensitive tool for evaluating white matter microstructure changes after stroke and has been widely used in clinical studies to evaluate therapeutic interventions. In clinical studies of stem cells for IS, DTI preliminarily demonstrated the regeneration and reorganization of motor pathways after interventions. These results will help us further understand the recovery mechanism of stem cell therapy, making it a valuable technique for translation research. However, DTI has limitations, including poor visualization of smaller fibers and methodological constraints in imaging and analysis, necessitating cautious interpretation of results.

Functional MRI (fMRI)

Functional MRI (fMRI) provides information about activity in brain regions based on changes in blood oxygen level-dependent (BOLD) [144]. The commonly used analysis methods for resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging (rs-fMRI) can be divided into two categories: one focuses on describing indicators of BOLD signal characteristics in the specific brain regions (Functional segregation); Another type focuses on analyzing the functional connectivity between different brain regions (functional integration). The functional segregation methods include regional homogeneity (ReHo) analysis and amplitude of low frequency fluctuation (ALFF) analysis. The functional integration assessments include the functional connectivity density analysis (FCD), seed-based analysis, independent component analysis (ICA), and graph-based analysis [123]. Currently, fMRI is commonly used to detect brain function and has been recognized as a robust marker of ischemia-induced brain injury and functional recovery in vivo, which can help guide the development of new treatments for IS [144–146].

In a 2012 human study, task-based fMRI analysis showed that the cluster activation in Brodmann regions BA 4 and BA 6 increased in the MNC group compared to the controls, indicating neural plasticity [16]. In 2020, Jaillard first measured the fMRI activity of passive wrist movement in a stem cell clinical trial. The results showed significant improvement in motor scores and a significant increase in primary motor cortex (M1) activity for 4a and 4p subregions in the treatment group compared to controls [57]. The results of motor scores and task-related fMRI activity indicate that MSCs may promote motor recovery through the sensorimotor cortex neuroplasticity after stroke. Consistent with previous research, increased M1 activity is associated with motor improvement in subacute and chronic stroke and may serve as a biomarker for motor function recovery [147–149]. In 2022, Lee et al. introduced the fMRI measurement in the STARTING-2 trial, and they found that the interhemispheric connectivity and ipsilesional connectivity increased significantly in the MSC group [56]. These findings suggest that MSC therapy might enhance macroscopic network reorganization, potentially promoting neurological recovery after IS. Collectively, these studies demonstrate that stem cell therapy can induce plasticity changes at neuronal and synaptic levels. The BOLD technique offers an objective basis for assessing efficacy and elucidating neurobiological mechanisms in stem cell-based therapy. Physiological measurements of cortical activity may be valuable biomarkers of functional recovery in future research.

Arterial spin-labeled perfusion imaging (ASL)

Arterial spin labeling (ASL) is a non-invasive MRI technique for assessing cerebral perfusion by labeling the proton spins in inflowing blood [150]. Based on different labeling schemes, ASL can be mainly divided into continuous ASL (cASL), pulsed arterial spin labeling (pASL), and pseudo-continuous ASL (pCASL) [151]. ASL can not only generate perfusion images for qualitative judgment but also quantitatively calculate cerebral blood flow (CBF), a characteristic parameter reflecting cerebral perfusion. Since CBF is closely related to neuronal function and metabolism, it is considered a marker associated with clinical prognosis [152, 153]. Kohno et al. showed that ASL imaging could detect diffusion-perfusion mismatched lesions in AIS patients and help to the treatment selection [154]. ASL with multiple post-labeling delays (PLDs) provided a better assessment of collateral circulation in AIS compared to a single PLD. Lou et al. found that higher leptomeningeal collateral perfusion scores obtained by ASL were a valuable biomarker of clinical prognosis in AIS patients after endovascular therapy [155]. Huang et al. found that the maximum CBF of hyperperfusion could predict hemorrhagic transformation, thereby guiding interventions to prevent bleeding events [156]. A study provided imaging evidence of plasticity in stroke patients with good recovery, involving increases in gray matter volume and perfusion in specified regions of the brain, including cognitive, emotional, and visual areas [157]. Recently, a basic study showed that BMSCs increased collateral circulation and improved prognosis after stroke [158]. Subsequent clinical studies incorporating the ASL sequence will help validate this phenomenon in humans. In recent years, several studies have combined fMRI and ASL to utilize the advantages of both techniques to better explore the neurovascular mechanisms of diseases [159, 160]. Thus, the integration of ASL with other imaging techniques will also become an important research direction.

Amide proton transfer (APT)

Amide proton transfer (APT), an innovative pH-sensitive imaging technique based on chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST), enables noninvasive detection of pH changes in post-stroke tissues [161]. The pH environment of the brain after stroke is closely related to cell survival, so it is important to monitor the pH changes to understand the metabolism and disease states during IS. This imaging approach holds promise for refining the existing clinical imaging protocols for IS. Several studies have demonstrated the role of APT imaging in IS, including identifying the ischemic penumbra, foreseeing clinical prognosis, and serving as a biomarker for treatment monitoring [162–164]. Song et al. found that the APT technique could reflect different pathophysiological stages of AIS, and APT weighted (APTw) signal intensities increased over time from stroke onset, while APTw max–min decreased [165]. Yu et al. observed APTw signal changes in AIS patients with supportive treatment and found that APTw signal was higher in patients with effective treatment and lower in patients with exacerbated symptoms, suggesting that APTw signal can be adopted as a neuroimaging marker to assess the therapeutic efficacy [166]. Lin et al. reported that ∆APTw had a significant correlation with the NIHSS and mRS scores. Both APTwipsi (ischemic area) and ∆APTw in the poor prognosis patients were significantly lower than those with good prognosis, and the APTwmax-min was significantly higher in the poor prognosis patients. These findings suggest that APTw parameters can be used to assess the severity of the patient’s condition and predict their prognosis [167]. Momosaka et al. showed that the APTw signal was lower in poor prognosis patients compared to those with good prognosis [168], consistent with Lin’s findings [167]. In summary, APT imaging, a noninvasive MRI technique operating at the cellular and molecular level, provides critical information during IS. In the future, APT imaging is expected to contribute to stem cell research, facilitating molecular-level exploration of the efficacy and mechanisms of cell-based therapies.

Susceptibility-weighted imaging (SWI)

Susceptibility-weighted imaging (SWI) is a novel MRI technique with high sensitivity to paramagnetic substances to assess cerebral hemodynamics after AIS [169]. This sequence is an effective imaging modality for detecting hemorrhagic transformation, microbleeds, and small draining veins [170]. Recently, the relationship between the asymmetrical prominent veins sign (APVS), susceptibility vessel sign (SVS), and patient’s clinical prognosis has become a hot research topic. Asymmetrical prominent veins sign (APVS) is a sign of asymmetrical dilated vessel-like signal loss in the SWI sequence. As an alternative way to evaluate collateral circulation, APVS can indirectly demonstrate an increase in the oxygen extraction fraction (OEF) [171, 172]. Several studies have explored the correlation between APVS signs and clinical prognosis, suggesting that patients with APVS might have a worse prognosis compared to those without this sign [173, 174]. The susceptibility vessel sign (SVS) primarily demonstrates a low signal in the artery on SWI. This sign can provide information about the morphology, size, and length of the intra-arterial thrombus [175]. Lee et al. reported that thrombus length was an independent predictor of recanalization failure after mechanical retrieval, and excessive thrombus length was associated with reduced recanalization success [176]. A meta-analysis showed that SVS-positive patients who received mechanical thrombectomy were more likely to have a favorable prognosis, while those receiving only intravenous thrombolysis or no reperfusion therapy tended to have a poor prognosis [177]. This suggested that SVS-positive AIS patients eligible for reperfusion therapy should be prioritized for mechanical thrombectomy in clinical practice. Notably, exploratory studies of these imaging markers can contribute to the development of individualized therapeutic methods and improve the prediction of clinical functions. Additionally, SWI can also be applied to the study of neuroplasticity after stroke by measuring angiogenesis [178]. This property holds significant potential for future stem cell clinical research.

Magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS)

During the development of ischemic stroke, metabolic changes often precede changes in morphology and function. Proton nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy (1H MRS) is considered the only non-invasive and non-radiative technique for evaluating metabolic changes in the human body. Moreover, 1H MRS does not require specialized equipment and is easily integrated into clinical applications.

Previous MRS studies showed an increase in lactate (Lac), and a decrease in N-acetylaspartate (NAA), creatine (Cr), and Choline (Cho) concentration after IS [179–181]. The recovery of these brain metabolite concentrations contributed to evaluating the restoration [182]. Among these metabolites, NAA is considered one of the most important parameters. NAA is mainly found in neurons and plays a crucial role in energy production and lipid synthesis in the brain. A decrease in NAA levels may indicate neuron loss or death [183]. These metabolites have been widely applied as alternative markers of neuronal activity (NAA), oxidative stress (Lac), cellular energy (Cr), and membrane integrity (Cho) [184–186]. In animal models, 1H MRS was used to measure NAA/Cho and NAA/Cr ratios in the lesion as a marker of cortical neurochemical activity, which significantly increased following BMSCs transplantation compared to the sham group [187, 188]. In a clinical trial, Haque et al. monitored metabolite changes in IS patients treated with autologous BMMNCs using non-invasive MRS [141]. They observed an increase in NAA concentration within the lesion. Notably, at the 3-month follow-up, ipsilateral NAA levels were significantly correlated with NIHSS scores. These findings support the use of MRS as a novel approach to evaluate therapeutic efficacy and underlying mechanisms by quantifying lesion metabolites. This is consistent with findings reported by Brazzini et al., who also observed increased NAA concentrations in the basal ganglia of Parkinson’s disease patients treated with autologous BMMNCs [189]. In addition, Spinal cord injection of BMSCs in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) also demonstrated metabolic improvement with prolonged survival and reduced disability [190]. In summary, the above evidence suggests that MRS is a potential technique for evaluating stem cell therapy in clinical trials. These preliminary findings encourage the initiation of large-scale clinical trials to further validate the results.

Multi-nuclear magnetic resonance (multi-NMR)

With the development of imaging techniques and the optimization of MRI equipment and sequences, MRI is evolving from traditional structural imaging (T1-weighted imaging) and functional imaging (DTI, fMRI, ASL) to molecular imaging (1H MRS, multi-NMR). The main limitation of 1H MRS is the potential masking of metabolite signals by water and lipid proton signals in vivo. Consequently, only a limited number of molecules, such as choline, creatine, NAA, and lactate, can be detected. Multi-NMR is based on a variety of nuclides (23Na, 31P, 13C, 129Xe, 17O, 7Li, 19F, 3H, 2H) and can obtain information on a wide range of metabolites in the human body [191]. With the rapid development of MRI hardware and software systems, the multi-NMR provides the possibility of real-time in vivo visualization of the metabolic changes in various diseases, including oncology, cardiovascular diseases, and neurological diseases. Several clinical trials utilizing multi-NMR are currently underway [192]. A recent study on stem cell therapy for IS introduced the evaluation of 23Na MRI, demonstrating restoration of sodium homeostasis, reduction of infarcted lesions in specimens transplanted with hMSC, and a decrease in lactate levels as shown by 1H MRS. The results of the behavioral assessment also further confirmed the MR findings [193]. Therefore, these MRI indicators may be critical for early efficacy assessment in stroke patients. The application of multi-NMR in stem cell clinical research holds promise. In neurological diseases, it is expected to be combined with fMRI and diffusion MRI to realize new ideas of metabolic-structural–functional analysis. Despite progress, much remains to be accomplished, such as standardization and quantification of results, and the exploration of new probes. Furthermore, the involvement of more clinical experts as well as the impetus of prospective multicenter trials may further advance the clinical translation of multi-NMR technology.

MRI-based cell tracking