Abstract

Background

Community-based palliative care and hospice is essential for meeting the preferences of terminally ill patients and reducing healthcare costs. However, systematic research on the decision-making factors concerning the patients and family caregivers remains limited. This study aimed to identify and categorise the factors related to the patients’ and family caregivers’ decision-making in the use of palliative care or hospice within the community.

Methods

This systematic review (PROSPERO: CRD42024612049) was conducted using the CINAHL, Cochrane Library, EMBASE, and Medline databases. Studies focusing on the patients’ and family caregivers’ decisions regarding palliative care and hospice were included, excluding the studies focusing solely on healthcare professionals. Four authors independently assessed the eligible studies and resolved discrepancies through discussion. The quality of the included studies was assessed using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool 2018. The data were qualitatively synthesised using a narrative approach and a constant comparison model. Decision-making factors were categorised based on Andersen’s behavioural model of health services use taking into consideration predisposing, enabling, and need factors.

Results

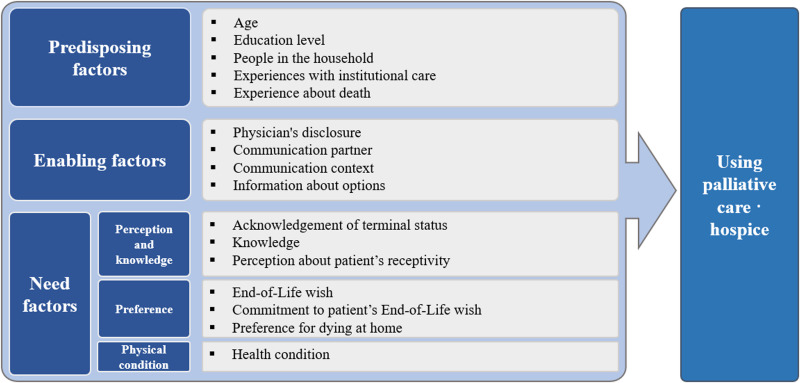

Seven studies, four quantitative and three qualitative, were included. Sixteen factors, including five predisposing factors (age, education level, people in the household, experiences with institutional care, and death experience), four enabling factors (physician’s disclosure, communication partner, communication context, and information about options), and seven need factors (acknowledgement of terminal status, knowledge, perception, end-of-life wishes, caregiver’s commitment, preference for dying at home, and health condition), were identified.

Conclusions

Patient and caregiver characteristics, personal experience, communication context, knowledge, preferences, and physical condition were the key factors related to the decision to use palliative care and hospice. This study highlights the importance of addressing these factors to support informed and patient-centred decision-making in end-of-life care.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12904-025-01793-4.

Keywords: Palliative care, Hospice, Decision making, Community health services, Systematic review

Background

The care of terminally ill patients has emerged as a pressing global issue, not only to ensure a dignified death for patients, but also to reduce social costs, particularly in the context of an aging society. As part of community-based end-of-life care, palliative care and hospice use have been proven to be effective in reducing unnecessary hospital admissions, emergency room visits, and excessive treatments. This approach is a desirable solution for reducing healthcare costs for both individuals and society [1]. Moreover, a previous systematic review including global studies reported that 59.9% of individuals expressed a preference for receiving home care services in a familiar environment and for living with their families during their final years, as their health and mobility declined [2]. However, despite these preferences, hospital mortality rates continue to rise globally, with South Korea reporting the highest hospital mortality rate (approximately 77%) among Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development countries [3]. These findings highlight the need for palliative care and hospice services within the community, including in-home settings and long-term care facilities; moreover, expansion of these services is urgently required.

Effective implementation of palliative care and hospice within the patients’ home or community is essential for enabling patients to choose their preferred setting for spending their final days. It is also crucial to first understand the decision-making factors of both the patients and their family caregivers as this understanding forms the foundation for developing a patient-centred care plan. Decisions regarding palliative care and hospice warrant a comprehensive approach taking into account the patients’ and families’ hopes, prognosis, and treatment goals. It is a complex process influenced by multiple factors including the active participation of patients, family caregivers, and healthcare providers [4, 5]. Factors such as age, sex, awareness and attitudes towards the disease, and religious beliefs of the patient and family caregiver are closely related to their decisions regarding palliative care and hospice [6–8]. Recognising these factors as early as possible, even before opting for community-based care at the end of life, is crucial for determining the appropriate timing for care and improving the quality of treatment.

The decision-making factors of palliative care and hospice serve as the starting point for care and the foundation for treatment development, which help healthcare providers support patients and family caregivers in positively perceiving palliative care and hospice within the community and home-care systems [9]. As healthcare providers play a crucial role in supporting and collaborating with patients and family caregivers in making decisions regarding palliative care and hospice [10], the identified factors can be modified or reinforced through appropriate interventions such as education or tailored support. These efforts can facilitate timely referrals to palliative care and hospice and support patients in making choices that enhance their quality of life.

Although identifying and exploring the underlying factors in making decisions regarding palliative care and hospice is an important aspect of providing patient-centred care at the end of life, few studies have organised the decision-making factors concerning patients and family caregivers. While some studies have identified individual decision-making factors, such as patient preferences, disease stage, and social environment conditions [11, 12], research that comprehensively and systematically examines the decision-making factors for the use of palliative care and hospice from both the patient and family caregiver perspectives remains limited. In addition, there is a lack of clear and systematic analysis of how these factors differ between the perspectives of patients and family caregivers. Therefore, it is necessary to systematically consolidate the decision-making factors related to palliative care and hospice from existing studies.

Given these considerations, this study adopts a broader view of community-based care by including long-term care facilities, recognising their role in delivering ongoing care outside acute care and hospital-centred settings. Certain residential options—such as assisted living or continuing care communities—serve as key components of community-based support, especially for individuals who are unable to remain at home due to complex needs [13, 14]. Based on this perspective, this review aimed to identify the factors that influence patients and family caregivers in their decisions to use palliative care and hospice within community settings, such as private homes and long-term care facilities, and to systematically organise and evaluate the elements revealed through this process.

Theoretical framework

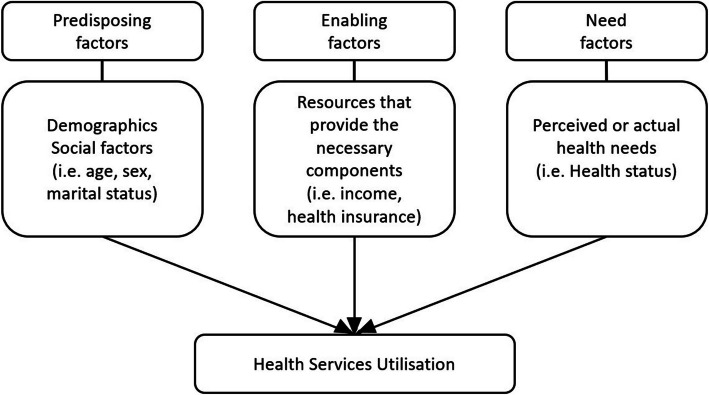

Andersen’s behavioural model of health services use (BMHSU) has been widely used to explain healthcare utilisation (Fig. 1). This model provides a theoretical framework for understanding access to and utilisation of health services, as well as recognising the factors that influence individual decisions [15, 16]. BMHSU proposes that health behaviour is influenced by the environment or care setting in addition to individual characteristics. Predisposing factors include elements, such as sociodemographics, that influence an individual’s likelihood of using healthcare services. Enabling factors refer to the resources that provide the necessary components for accessing appropriate care, such as economic resources or social support. Need factors pertain to the perceived or actual health needs driving individuals to seek care, including health status.

Fig. 1.

Andersen’s behavioural model of health services use

Building on the predisposing, enabling, and need factors from BMHSU [16], as outlined by Alkhawaldeh et al. [17], this framework was implemented for organising the decision-making factors. This study adopted BMHSU to explore the decision-making process in palliative care and hospice. The application of this model helps better understand the complex interplay between these factors in healthcare utilisation, thereby providing valuable insights into access to palliative care and hospice services. These findings can assist researchers and practitioners in improving end-of-life care outcomes in community settings.

Thus, all the factors influencing decision-making can be identified and categorised using this validated model. This approach provides high-level evidence for encouraging patients towards initiating changes, thus promoting the selection of palliative care and hospice.

Methods

Design

This review followed the recommendations of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses 2020 guidelines [18] and the protocol was prospectively registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) (CRD42024612049) on 21 November 2024. No amendments were made to the information provided at the time of protocol registration or review. This study used literature sources without identified data and was exempted from ethical approval.

Eligibility criteria

Eligible studies included quantitative, qualitative, and mixed-methods studies, in which the decision-making factor of palliative care and hospice was considered the main outcome. The outcomes should be centred on decision-making factors for palliative care or hospice use within the community, including in-home and long-term care facilities. Only original full-text articles published in English were included in the analysis. Studies including patients aged > 18 years, at the end of life, receiving palliative care or hospice in home settings or long-term care facilities, and their family caregivers were included. Studies conducted solely on healthcare professionals were excluded to focus on patient factors. Studies involving participants aged ≤ 18 years were also excluded because decision-making in paediatric palliative care or hospice usually involves parents and thus should be considered separately. Studies conducted in emergency, acute, or inpatient settings, as well as those not centred on decision-making factors for palliative care or hospice itself or not involving terminally ill or end-of-life patients, were also excluded. The eligibility criteria for our review are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria | |

|---|---|---|

| Population |

Patients aged > 18 years and their family caregivers All diseases resulting in terminally ill conditions |

Age ≤ 18 years, healthcare professionals |

| Intervention | Using palliative care or hospice | Not using palliative care or hospice |

| Outcome | Identifying the decision-making factors for using palliative care or hospice | Not focused on the decision-making factors for palliative care and hospice usage |

| Time | At the end-of-life or terminally ill | Not terminally ill or having a recoverable illness |

| Setting | In home settings and long-term care facilities | Emergency, acute, and inpatient settings |

| Study design | Quantitative, qualitative, and mixed-methods studies | Systematic review, systematic review-meta-analysis |

| Form of publication | Peer-reviewed original paper Written in English | Editorial, commentary, letter, conference abstract, and protocol |

Search strategy and study selection

To identify the studies, the following four electronic databases were searched: CINAHL, Cochrane Library, EMBASE, and Medline. The main keywords consisted of keywords, thesaurus, and free terms including 'palliative care' or 'hospice', 'decision-making', 'terminally ill', and 'community health services'. The search strategy was finalised after review by a librarian. The full search terms for each database are presented in Additional file 1, and the final search strategy for Ovid Medline is provided in Additional file 2. The final search for all the sources was completed on 24 October 2024.

EndNote and Rayyan were used to manage the data from the retrieved studies. EndNote was used to eliminate the duplicates. The remaining screening and final selection processes were performed using Rayyan (www.rayyan.ai), an online tool specifically designed to assist the screening process in a systematic review. This allowed multiple reviewers to work independently and blindly, based on each other’s decisions. The records were randomly divided into halves, and four researchers were randomly split into pairs (SC and MK, JEP, and JK). Each pair of researchers was assigned to screen half of the data. Titles and abstracts were reviewed during the initial screening. A full-text review was conducted, in which the researchers were reorganised into different pairs (SC and JEP, MK and JK) to minimise bias. Each study was reviewed by the reviewers based on the eligibility criteria, and the final list of included studies was determined. Any discrepancies or disagreements were first discussed and resolved within the pair, and group discussions involving all four researchers were conducted to manage issues that were not resolved within the pair of researchers.

Quality assessment of included studies

As the included studies had various designs (quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods), the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) 2018 version was used for quality appraisal [19]. Two researchers (MK and JK) independently assessed the quality of each selected study, after which any discrepancies or disagreements were resolved by four researchers. Quality appraisal results were reported at the individual study level.

Data extraction

For data collection, four researchers manually extracted data from the full texts independently and recorded them in predefined data extraction tables. Before commencing full data extraction, a pilot test of the data extraction form was conducted to ensure its clarity and comprehensiveness. Through this process, the researchers reached a consensus on any necessary modification to the form. Following this, the four researchers were divided into two teams (SC and JP; MK and JK). Each team was assigned a set of studies. Both researchers within each team independently extracted data from the assigned studies. After independent extraction, the researchers within each team reviewed and discussed their results to reach a consensus. The following data were extracted from each study: author, year, country, aim or objective, study design, data sources, characteristics of the target population (specifying the patients' disease conditions when applicable), time point, setting, key findings, and identified decision-making factors related to the use of hospice and palliative care as outcomes of the studies. Any discrepancies or disagreements regarding the extracted data were resolved through group discussion.

Data synthesis

A constant comparison model framework [20] was employed for data synthesis. A qualitative synthesis based on a narrative textual approach was used to summarise, analyse, and assess the evidence included in this review. To facilitate analysis, data from the studies were extracted and placed in a table. The data were subsequently compared by item, and similar factors were categorised and grouped together. By following these steps, the decision-making factors were drawn and verified.

According to BMHSU [16], health service utilisation is a result of interactions among various factors. In this review, the predisposing, enabling, and need factors were categorised for explaining the decision-making process regarding the use of palliative care and hospice services in the community, among the various influencing factors.

Results

Search outcomes

A total of 3,062 studies were identified in the initial search. After eliminating 859 duplicates, the titles and abstracts of the remaining 2,203 studies were screened; 68 studies were further assessed by screening full texts for eligibility. Studies were excluded primarily for not focusing on palliative care or hospice use, not addressing decision-making factors, or not being done in community settings. As a result of these exclusions, a total of seven studies were included in the final review (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Flow diagram of study selection

Quality assessment of the selected studies

The information included in the quality assessment of the selected studies using the MMAT is shown in Table 2. Regarding the quality of quantitative studies, only two studies [21, 22] met four out of five criteria, whereas two studies [23, 24] failed to meet two or three criteria, resulting in overall low quality. In contrast, qualitative studies [10, 25, 26] generally demonstrated higher quality; with the exception of one study [26], the other two studies met all five criteria.

Table 2.

Quality Appraisal Results for Individual Studies

| Author (Year) | Category of study designs | Methodological quality criteria | Responses | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Can’t tell | |||

| All included studies | Screening questions (for all types) | S1. Are there clear research questions? | X | ||

| S2. Do the collected data allow to address the research questions? | X | ||||

| Prigerson (1991) [19] | Quantitative descriptive | 4.1. Is the sampling strategy relevant to address the research question? | X | ||

| 4.2. Is the sample representative of the target population? | X | ||||

| 4.3. Are the measurements appropriate? | X | ||||

| 4.4. Is the risk of nonresponse bias low? | X | ||||

| 4.5. Is the statistical analysis appropriate to answer the research question? | X | ||||

| Chen et al. (2003) [20] | Quantitative descriptive | 4.1. Is the sampling strategy relevant to address the research question? | X | ||

| 4.2. Is the sample representative of the target population? | X | ||||

| 4.3. Are the measurements appropriate? | X | ||||

| 4.4. Is the risk of nonresponse bias low? | X | ||||

| 4.5. Is the statistical analysis appropriate to answer the research question? | X | ||||

| Csikai (2006) [21] | Quantitative descriptive | 4.1. Is the sampling strategy relevant to address the research question? | X | ||

| 4.2. Is the sample representative of the target population? | X | ||||

| 4.3. Are the measurements appropriate? | X | ||||

| 4.4. Is the risk of nonresponse bias low? | X | ||||

| 4.5. Is the statistical analysis appropriate to answer the research question? | X | ||||

| Choi et al. (2012) [22] | Quantitative descriptive | 4.1. Is the sampling strategy relevant to address the research question? | X | ||

| 4.2. Is the sample representative of the target population? | X | ||||

| 4.3. Are the measurements appropriate? | X | ||||

| 4.4. Is the risk of nonresponse bias low? | X | ||||

| 4.5. Is the statistical analysis appropriate to answer the research question? | X | ||||

| Stajduhar & Davies (2005) [23] | Qualitative | 1.1. Is the qualitative approach appropriate to answer the research question? | X | ||

| 1.2. Are the qualitative data collection methods adequate to address the research question? | X | ||||

| 1.3. Are the findings adequately derived from the data? | X | ||||

| 1.4. Is the interpretation of results sufficiently substantiated by data? | X | ||||

| 1.5. Is there coherence between qualitative data sources, collection, analysis and interpretation? | X | ||||

| Holdsworth et al. (2011) [24] | Qualitative | 1.1. Is the qualitative approach appropriate to answer the research question? | X | ||

| 1.2. Are the qualitative data collection methods adequate to address the research question? | X | ||||

| 1.3. Are the findings adequately derived from the data? | X | ||||

| 1.4. Is the interpretation of results sufficiently substantiated by data? | X | ||||

| 1.5. Is there coherence between qualitative data sources, collection, analysis and interpretation? | X | ||||

| Ko et al. (2020) [10] | Qualitative | 1.1. Is the qualitative approach appropriate to answer the research question? | X | ||

| 1.2. Are the qualitative data collection methods adequate to address the research question? | X | ||||

| 1.3. Are the findings adequately derived from the data? | X | ||||

| 1.4. Is the interpretation of results sufficiently substantiated by data? | X | ||||

| 1.5. Is there coherence between qualitative data sources, collection, analysis and interpretation? | X | ||||

In the quantitative studies, all four studies [21–24] had the limitation of not using appropriate measurement tools. The instruments employed in these studies either lacked a clear rationale or were not validated, leading to the conclusion that the quantitative aspects of the studies were not appropriately measured. Csikai [23] had a low response rate of 37%, while Choi et al. [24] had an overall response rate of 64%; however, the response distribution was skewed, which was a significant limitation. Holdsworth and King [26] were judged to have an inappropriate research methodology as they failed to adequately explain the objectivity of the research findings and how they were related to the themes.

Some of the studies were of lower quality; however, the MMAT guidelines do not recommend excluding studies from the list based solely on low quality [19]. Additionally, the final list might not have contained a sufficient number of studies. Therefore, all the studies were included regardless of their quality.

In addition, the inclusion of data was not restricted by the publication year, as it was necessary to include as many relevant studies as possible that met the criteria owing to the limited amount of quantitative research on the topic. Although Prigerson’s study [21] was published in 1991, it was considered relevant and valuable, as it addressed decision-making factors grounded in enduring human values—such as the preferences and needs of both patients and family caregivers—rather than time-sensitive trends. Moreover, it provided a clear rationale for each outcome examined. Consequently, the study by Prigerson [21] was deemed to be of high quality and included in the final list.

General characteristics of the selected studies

The general characteristics of the included studies and information are summarised in Table 3. The selected studies were published between 1991 and 2020. Four studies used quantitative survey questionnaires [21–24]. The other three were qualitative and employed interviews and observations [10, 25, 26]. Four studies were conducted in the United States [10, 21–23], while the remaining studies were conducted in England [26], Canada [25], and Japan [24]. Except for one study [24], all the other studies were conducted in English-speaking countries, which is not surprising as the search was limited to English-language studies owing to language barriers. The total sample sizes of the studies ranged from 19 to 286 participants. Five studies reported the age of their sample, with the average age of the patients ranging from 69.2 to 72 years, and the average age of the family caregivers ranging from 54 to 61 years. The diseases of the patients varied across the studies, but most of the studies focused on patients with conditions, such as cancer or heart disease, specifically targeting terminally ill patients with a life expectancy ranging from at least 3 months to less than 1 year, or their family caregivers [10, 21–23, 26]. One study focused solely on patients [22], whereas four studies targeted family caregivers, including bereaved individuals [10, 23–25]. The remaining two studies included both patients and family caregivers [21, 26]. Regarding the types of services, most studies were conducted on hospice services [10, 21–23, 26], whereas only one was conducted on palliative care [25]. Except for one study conducted in a community care setting [26], all the other studies were conducted in home-based care settings [10, 21–25].

Table 3.

General Characteristics of the Included Studies

| No | Author, year | Country | Aim/objective | Study design/Data collection | Population | Disease conditions | Time point | Setting | Key findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Prigerson,1991 [19] | US | To examine the factors expected to facilitate or inhibit the utilisation of home-based hospice services | Quantitative (cross-sectional)/Survey | 76 terminally ill patients aged > 65 years, their physicians and primary informal caregivers | Terminally ill | At life expectancy ≤ 6 months | Home-based hospice | Patients who acknowledged their terminal health status, whose physicians disclosed the terminal prognosis to them and did not fear malpractice, whose primary caregivers knew about hospice and believed the patients would be receptive to enrollment in such a programme, demonstrated a relatively high probability of home health hospice utilisation |

| 2 | Chen et al.,2003 [20] | US | To identify the factors influencing advanced cancer patients'choice between hospice and hospital care | Quantitative (cross-sectional)/Interview (structured questionnaire) | 173 hospice patients from home-based hospice, 61 non-hospice patients from three hospitals | One of four cancers at an advanced stage (breast, colon, lung, or prostate) | At life expectancy ≤ 1 year | Home-based hospice and hospitals | Hospice patients were older, less educated, had more comorbidities, lower ADL scores, and larger households. They prioritised quality of life and were more realistic about their disease. Lower education and larger households were key factors in choosing hospice. Families mostly made hospice decisions (42%) |

| 3 | Csikai, 2006 [21] | US | To explore bereaved hospice caregivers'experiences of communication in deciding and transitioning to hospice care |

Quantitative (cross-sectional)/Survey |

108 bereaved hospice caregivers of patients who died after receiving home hospice services | Cancer, heart disease, and Alzheimer's dementia | 3–6 months from the time of the patient's death | Home-based hospice | Physicians initiated discussions on hospice; nurses and social workers aided the transition to home hospice; social workers were the most comfortable, knowledgeable, and available in EOL care discussions. Caregivers suggested earlier vital information and realistic discussions about death and individualised care |

| 4 | Choi et al.,2012 [22] | Japan |

To evaluate whether family members believed that the decision for home hospice had been the acceptable choice To identify the decision process and who determines the need for home hospice To identify the factors related to families accepting that the decision was appropriate |

Quantitative (cross-sectional)/Survey | 286 bereaved family members of terminal cancer patients in 14 home hospices | Terminal cancer | ≤ 6 months from the time of the patient's death | Home-based hospice | Consideration of a patient’s desire ahead of the family situation, enrollment in home hospice based on the knowledge of all the options, the identity of the person who decided in favour of home hospice, and a short duration of home hospice were positively associated with acceptance of home hospice |

| 5 | Stajduhar et al.,2005 [23] | Canada | To describe the variations in and factors influencing the family members'decisions for palliative home care | Qualitative (ethnographic methodology)/Observation and interview | 13 family members actively providing palliative care to a patient at home, 47 bereaved family members, 25 health care professionals | No restrictions: cancer, AIDS, end stage cardiac disease, ALS, other | No restrictions | Home-based palliative care |

Decisions were influenced by three factors: 1) a promise caregivers made to the dying person to care for them at home 2) the caregivers'desire to have the dying person in an environment where a'normal life'could be maintained 3) a desire to avoid institutional care |

| 6 |

Holdsworth et al., 2011[24] |

England | To identify the issues around discussing and recording preferences concerning the place of death from the perspective of hospice patients, carers, and hospice community nurse specialists | Qualitative/Interview | 6 community nurse specialists from hospices, 4 patients, 5 carers, 4 bereaved carers | Life-limiting illness | Life expectancy of less than 12 months | Community-based palliative care | Having more knowledge about what to expect of the dying process, knowing their relative’s wishes, and understanding the role of hospice and palliative care could improve the experience of events leading up to death |

| 7 |

Ko et al., 2020 [10] |

US (US-Mexico border regions) |

To explore decision-making experiences related to the utilisation of hospice care programmes | Qualitative/Interview | 23 family caregivers aged + 18, providing care for patients receiving hospice services from a large home health agency | Terminal status | At life expectancy ≤ 6 months | Home-based hospice | Initiators: home healthcare staff (39.3%) and physicians (32.1%). Challenges: communication barriers, lack of knowledge, emotional difficulties, and patient readiness. Facilitators: EOL wishes, family caregiver-physician communication, declining health, home preference |

ADL Activities of daily living, EOL End of life, AIDS Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, ALS Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

Decision-making factors

The factors identified in each study were consolidated by grouping the overlapping concepts, resulting in 16 comprehensive common elements. These factors were then classified according to BMHSU [16] as predisposing, enabling, and need factors (Fig. 3). Additional file 3 presents the detailed decision-making factors for each study.

Fig. 3.

Decision-making factors for use of palliative and hospice care based on BMHSU

Predisposing factors

Personal characteristics influencing the use of palliative care and hospice services included demographics, social aspects, and past experiences, which served as predisposing factors that determined the likelihood of utilising these services (Table 4).

Table 4.

Predisposing Factors for Using Palliative Care and Hospice

| Component | Decision-making factor (Direction of factor influence) |

Study number |

|---|---|---|

| Predisposing factor | Personal experience about death (↑) | #1 |

| Age (↑) | #2 | |

| Education level (↓) | #2 | |

| Number of people in the household (↑) | #2 | |

| Previous negative experiences with institutional care (↑) | #5 |

Family caregivers with prior death experience were more likely sensitive to the pain associated with dying and were reluctant to recommend life-extending treatments for terminal patients, which resulted in better understanding of the benefits of palliative care [21]. Elderly patients in the terminal stages of cancer were more willing to opt for hospice care, whereas younger patients were more likely to opt for aggressive treatment interventions [22]. Additionally, individuals with lower education levels tended to prefer less aggressive treatment with impending death [22]. The presence of a caregiver, which has long been a criterion for hospice admission, was found to influence the decision to opt for hospice care, with a higher number of people living with the patient at home serving as a determining factor [22]. The negative experiences of family caregivers with institutional care contributed to decreased trust in hospital-based service providers. These experiences motivated family caregivers to 'fight' for high-quality medical care for the patient and seek home care for prompt and adequate pain management [25].

Enabling factors

The factors providing practical support for the utilisation of palliative care and hospice services are presented in Table 5. This category included resources or conditions, such as financial resources, accessibility to the healthcare system, and social support networks, which enabled access to healthcare services. Several factors related to communication were classified as enabling factors. The initial Andersen Health Behaviour Model [15] did not include the aspects of social relationships. Communication was classified as an enabling factor based on BMHSU [16] and other studies [17].

Table 5.

Enabling Factors for Using Palliative Care and Hospice

| Component | Decision-making factor (Direction of factor influence) |

Study number |

|---|---|---|

| Enabling factor | Physician’s disclosure (↑) | #1 |

| Communication partner (↑) |

Patient-family caregiver-nurse-social worker #3 Patient-family caregiver #4 Patient-professionals #6 Family caregiver-professionals #7 |

|

| Early realistic communication (↑) | #3 | |

| Providing information about options (↑) | #4 |

Physicians’ access and communication of important information significantly influence the likelihood of a patient's utilisation of hospice services. Disclosing the terminal prognosis to patients itself has a highly positive impact on a patient's decision to receive hospice care [21]. Communication within the social support network was classified based on whether it was more related to the communication counterpart or to the nature and content of the communication itself. Effective communication regarding care and patient preferences is essential between family caregivers and healthcare professionals [10], patients and family caregivers [24], and patients, family caregivers, nurses, and social workers [23]. This communication is closely related to the patients’ decisions, and discussion of end-of-life preferences with palliative care professionals [26] has been emphasised as an important foundation of patient care. Regarding the aspect of context, communication related to end-of-life matters should include honest and realistic discussions about the reality of death at an early stage [23]. Furthermore, enrolment in home hospice care should be based on the comprehensive understanding of all available treatment options, as this has been shown to be positively associated with the acceptance of home hospice care. It is essential to provide patients with information on all the potential treatment options [24].

Need factors

Individuals’ needs and desires play a crucial role on the behaviour or decisions. Need factors focused on the themes related to severity of health issues and health conditions or symptoms that compelled individuals to utilise healthcare services. These themes were further divided into three subthemes: perception and knowledge, preference, and physical condition (Table 6).

Table 6.

Need Factors for Using Palliative Care and Hospice

| Component | Decision-making factor | Study number | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (Direction of factor influence) | |||

| Need factor | Perception and knowledge | Acknowledgement of their terminal status (↑) | #1 |

| Knowledge (↑) | Of hospice #1 | ||

| About the dying process #6 | |||

| Understanding of the effect of palliative care and hospice #6 | |||

| Perception about the patient’s receptivity (↑) | #1 | ||

| Preference | End-of-Life wish (↑) | Patient’s wish #6, 7 | |

| Patient’s desire #4 | |||

| Patient's and caregiver's wish to maintain normalcy #5 | |||

| Commitment to patient’s end-of-life wish (↑) | #5 | ||

| Preference for dying at home (↑) | #7 | ||

| Physical condition | Health condition (↓) | Deteriorating #7 | |

| Comorbid condition #2 | |||

| Activities of Daily Living #2 | |||

Elements of perception and knowledge, including acknowledgement, knowledge, and perception, can be defined from a cognitive perspective and characterised based on self-assessed subjective evaluation. This includes the patient’s acknowledgment of their disease state [21] and the family caregiver’s perception of the patient’s willingness to accept care [21]. Knowledge is interconnected across various subjects and ultimately refers to the information formed based on the family caregiver’s understanding of hospice care [21], its effects [26], and the process of death [26].

Individuals’ treatment preferences are significant factors in determining the utilisation of healthcare services that fulfil these preferences. Specifically, patients’ end-of-life wishes and their goals of care [10, 24, 26], which aim to maintain dignity at the end-of-life, as well as the wishes of the patient and caregiver to preserve normalcy [25], have become key facilitators in opting against aggressive treatments. Choosing palliative care or hospice at home for end-of-life care supports the patients’ wish to die in the place where they reside [10]. Ultimately, the caregivers’ efforts and promise to commit to fulfilling the various end-of-life wishes of patients [25] can meet patients’ needs which, in turn, become a key factor in the utilisation of palliative care and hospice services in a community setting.

Physical aspects include health conditions that are typically professionally assessed. Worsening health status [10], the presence of additional comorbidities [22], and a decline in the activities of daily living (ADL) [22] reportedly facilitate the increased utilisation of palliative care or hospice, as they are linked to the loss of autonomy in daily life.

Discussion

This study systematically reviewed studies exploring the factors that influence the decisions of patients and family caregivers in the community concerning the utilisation of palliative care and hospice services using BMHSU as a framework [16]. This study identified 16 decision-making factors, the demographic characteristics of users, available supportive resources and their needs, thus providing evidence on strengthening of the support elements for increasing the use of palliative care and hospice services.

Regarding predisposing factors, characteristics such as older age, larger household size, caregivers’ personal death experiences, and prior negative experiences with institutional care were identified as having a positive influence on the decision to accept hospice palliative care or hospice, whereas a higher education level demonstrated a negative influence [21, 22, 25]. In studies focusing on hospital-based settings, factors affecting end-of-life decision-making included older age, female sex, White race, higher median income, and characteristics of the primary hospital provider, such as the presence of a hospice unit [27, 28]. While previous studies have emphasised the importance of patient-related characteristics in end-of-life decision-making in hospital-based settings, our findings revealed that caregiver-related factors also play a crucial role in influencing end-of-life decisions in community settings. These findings suggest the need for careful consideration of both patient and caregiver characteristics when making hospice or palliative care referrals and providing information about these services. In contrast, although not explicitly stated in the included studies, it is known from the literature that there are ethnic differences, including cultural differences, in end-of-life care. For instance, while Western approaches tend to prioritise patient-centred decision-making, the involvement of family members is particularly emphasised in Asian cultures. Moreover, religious beliefs may also play a role [29, 30]. Thus, development of sensitive treatment approaches considering these differences is warranted, and future research should include comparative studies that reflect different cultural backgrounds.

The enabling factors were primarily related to key aspects of communication involving participants such as patients, caregivers, and healthcare professionals, as well as the context, both of which significantly influenced hospice care decisions. Regarding communication with participants, interactions among primary stakeholders (i.e. patients, caregivers, and healthcare professionals) and discussions with others outside the decision-making process helped patients in making the decisions. Open discussion of challenging topics, such as death and hospice care, likely helped clarify the participants' thoughts and empower decision-making [26]. Support groups fostering such discussions could further facilitate hospice care decisions [31]. Notably, one study highlighted the effectiveness of social workers, but this was mostly attributed to the establishment of a stronger rapport with patients than with other healthcare professionals [23]. This finding suggests that the context and quality of communication may be more important than the specific individuals involved. Considering the context of communication, providing comprehensive and realistic information at an early stage was found to be crucial, which is consistent with the findings of previous studies [32]. However, direct communication may not always be ideal. One study noted that forcing discussions on unprepared patients and caregivers could result in resistance [26], whereas other studies emphasised that some forms of 'direct' communication may feel insensitive or disrespectful, thereby negatively affecting hospice care decisions [10, 23]. These findings underscore the importance of healthcare professionals carefully assessing the needs and readiness of patients and caregivers and tailoring their communication to provide appropriate and timely information.

The need factors identified in this study provide valuable insights into the factors that should be assessed. Specifically, the types of need factors included perception and knowledge, preferences, and physical conditions. Factors related to perception and knowledge included the patients’ and caregivers’ knowledge about hospice care and the dying process, as well as the caregivers’ perception of the patient’s acceptance of hospice care [21, 26]. These findings align with those of previous studies emphasising that a lack of patient awareness is a key factor associated with not utilising hospice and palliative care [33]. The process of recognising and accepting a patient’s terminal condition is essential for both patients and caregivers, thus facilitating better acceptance and preparation for death. Therefore, providing accurate information about the patient’s terminal status and dying process, along with educational programmes aimed at enhancing the understanding of hospice and palliative care, is crucial. Particularly in the context of palliative care, where patients and their families are considered a unit of care, and family caregivers actively participate in decision-making regarding palliative interventions [34], educational initiatives should target both patients and their family caregivers. Another key approach to addressing these needs is strengthening the capabilities of healthcare providers. By enhancing their knowledge and skills in palliative care, providers can better identify and respond to the needs of both patients and their families in a timely manner [35]. Therefore, educational programmes should also focus on equipping healthcare providers with the necessary competencies to deliver appropriate palliative care.

Among the need factors, patient and caregiver preferences such as general end-of-life wishes [10, 24–26] and preferences for dying at home [10], were of significant importance. These findings are consistent with prior research emphasising the critical role of the patient's and caregiver's preferences in end-of-life care decisions [36]. This evidence highlights that values and preferences as perceived by patients and family caregivers are crucial concerning decisions regarding palliative care and hospice services. Standardised tools, such as the Integrated Palliative Outcome Scale, Palliative Care Outcome Scale, and Quality of Life at the End of Life, can be employed, which offer a practical approach to quantifying preferences and improving care alignment in community settings [37]. While many studies underscore the importance of patient preferences, one study suggested that caregiver preferences may have a greater impact [21]. Recent studies reinforcing the importance of family caregivers' preferences for support in patient-centred end-of-life care [38] highlight that despite the evolving social and healthcare environments since Prigerson's study [21], the key factors influencing decision-making have not fundamentally changed. Preference for the place of death also played a key role. One study found that the preference of home as the place of death influenced the decision concerning enrolment in hospice services [10], supporting previous studies that highlighted the importance of location preferences in shaping end-of-life care strategies [39]. Community nurses should actively elicit and clarify these preferences, provide realistic guidance, and integrate them into palliative care and hospice referrals.

In terms of physical conditions categorised as need factors, deteriorating health status [10], multiple comorbidities, and lower ADL levels [22] have been identified as key factors influencing palliative care and hospice decisions. These findings indicate that patients with declining health and physical capabilities are more likely to be referred for palliative care and hospice services. However, patients referred after significant health deterioration may not receive adequate care. A previous study involving patients from 23 countries reported that the median duration from the initiation of palliative care until death was only 18.9 days [40]. Given that the primary objectives of palliative care and hospice extend beyond preparation for death to emphasise patient comfort and quality of life, early screening and timely referrals are essential for ensuring complete patient benefit from the use of these services [41]. Nurses can play a major role in assessing the patients’ health status, coordinating with healthcare providers and families, and ensuring the provision of appropriate care in a timely manner [42]. To support these efforts, standardised tools should be employed to accurately assess the patients’ physical conditions in community settings and identify those in need of palliative care and hospice services. Currently, tools such as the Supportive and Palliative Care Indicators Tool (SPICT) and Necesidades Paliativas (NECPAL) have been employed for assessing clinical indicators [36]. However, these measurement tools focus less on the usage, research frequency, and importance in community settings than in clinical settings [43, 44]. Therefore, an ongoing evaluation of their reliability and validity in community settings is warranted to ensure their continued development and effectiveness. Thus, the findings of these evaluations could be utilised in the future to develop patient-screening tools suitable for community settings.

The importance of community-based palliative care and hospice services increases with aging of the population. To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review to examine the factors influencing the use of these services in community settings. Future research should focus on high-quality studies exploring diverse populations and the dynamic factors that shape decision-making. Additionally, systematic evaluations of the usage and effectiveness of the tools currently employed for screening patients in need of referral for palliative care and hospice services within community settings are warranted. This should be accompanied by concrete discussions and consideration of intervention strategies for improving the transition process towards hospice and palliative care.

Limitations

Although this review provides important insights into decision-making factors in palliative and hospice care, it has certain limitations. Studies providing useful findings may have been excluded. Owing to our research objective of examining settings outside hospitals, long-term care facilities were in the inclusion criteria. However, there may be perspectives that do not view long-term care facilities as community-based. Additionally, regional differences in defining community-based care may limit the applicability of results. While this review highlights decision-making factors from the perspectives of patients and family caregivers, it may underrepresent structural or systemic influences that are less amenable to individual control but, nonetheless, play a critical role in palliative and hospice care utilisation. Three of the seven studies included in the analysis were qualitative, which limited the quantitative synthesis due to the heterogeneity and non-comparability of the data. Consequently, this study focused on identifying and systematically categorising influencing factors. Publication biases, including language and national biases, may have existed because the search was limited to literature published in English and excluded grey literature. The number of included studies was small and the overall quality of the research was low, with some outdated studies.

Conclusion

This systematic review based on a validated theoretical framework highlights the multifaceted factors influencing the use of palliative care and hospice services in community settings. Our review revealed that various factors, including the patient’s and family caregiver’s characteristics, personal experience, communication context, knowledge, preferences, and physical condition, were associated with the utilisation of palliative care and hospice services. By synthesising diverse evidence, this review provides a deeper understanding of end-of-life care decision making. Healthcare professionals should consider these factors for educating and supporting patients in making decisions that preserve their quality of life at the end-of-life.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1. Table. Full Search Terms for Databases.

Additional file 2. Table. The Example of Search Strategy in Ovid Medline.

Additional file 3.Table. Factors Influencing the Using Palliative Care and Hospice in Included Studies.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable

Abbreviations

- ADL

Activities of daily living

- AIDS

Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome

- ALS

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

- BMHSU

Behavioural model of health services use

- EOL

End of life

- MMAT

Mixed methods appraisal tool

Authors’ contributions

SC, MK, JEP, JK, and KW conceptualised and designed the study. Search strategy and data search were performed by SC, MK, JEP, and JK after discussion with KW. Records screening and data extraction were completed by SC, MK, JEP, and JK, and discussed with KW. SC, MK, JEP, and JK drafted the manuscript, and KW reviewed and edited it. KW provided supervision. All the authors contributed to data interpretation, revised the manuscript, and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This research was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (No.RS-2024–00334672) and by the BK21 four project (Center for World-leading Human-care Nurse Leaders for the Future) funded by the Ministry of Education (MOE, Korea).

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Planning and implementing palliative care services: a guide for programme managers. World Health Organization. 2016. https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/250584. Accessed 10 Dec 2025.

- 2.Nilsson J, Blomberg C, Holgersson G, Carlsson T, Bergqvist M, Bergström S. End-of-life care: where do cancer patients want to die? A systematic review. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol. 2017;13(6):356–64. 10.1111/ajco.12678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. End-of-life care, health at a glance 2021: OECD indicators. 2021. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/social-issues-migration-health/health-at-a-glance-2021_906d56e2-en. Accessed 10 Dec 2025.

- 4.Lovell A, Yates P. Advance care planning in palliative care: a systematic literature review of the contextual factors influencing its uptake 2008–2012. Palliat Med. 2014;28(8):1026–35. 10.1177/0269216314531313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mahon MM. Clinical decision making in palliative care and end of life care. Nurs Clin North Am. 2010;45(3):345–62. 10.1016/j.cnur.2010.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tang ST, Huang EW, Liu TW, Wang HM, Chen JS. A population-based study on the determinants of hospice utilization in the last year of life for Taiwanese cancer decedents, 2001–2006. Psycho-Oncol. 2010;19(11):1213–20. 10.1002/pon.1690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.An AR, Lee JK, Yun YH, Heo DS. Terminal cancer patients’ and their primary caregivers’ attitudes toward hospice/palliative care and their effects on actual utilization: a prospective cohort study. Palliat Med. 2014;28(7):976–85. 10.1177/0269216314531312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.An AR, Yun YH, Lee WJ, Jung KH, Do YR, Kim S, et al. Do the preferences of patients with terminal cancer or their family caregivers and end-of-life care discussions influence utilization of hospice-palliative care? J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(15_suppl):9041. 10.1200/jco.2011.29.15_suppl.9041. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shalev A, Phongtankuel V, Kozlov E, Shen MJ, Adelman RD, Reid MC. Awareness and misperceptions of hospice and palliative care: a population-based survey study. Am J Hosp Palliat Med. 2018;35(3):431–9. 10.1177/1049909117715215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ko E, Fuentes D, Singh-Carlson S, Nedjat-Haiem F. Challenges and facilitators of hospice decision-making: a retrospective review of family caregivers of home hospice patients in a rural US–Mexico border region—a qualitative study. BMJ Open. 2020;10(7):E035634. 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-035634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McLouth LE, Borger T, Bursac V, Hoerger M, McFarlin J, Shelton S, et al. Palliative care use and utilization determinants among patients treated for advanced stage lung cancer care in the community and academic medical setting. Support Care Cancer. 2023;31(3):190. 10.1007/s00520-023-07649-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sharma K, Prathipati RP, Agrawal A, Shah K. A review on determinants and barriers affecting the transition from curative care to palliative care in patients suffering from terminal cancer. Int J Res Med Sci. 2023;11(6):2333–7. 10.18203/2320-6012.ijrms20231667. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Denham AC, Kistler CE. Home- and community-based care. In: Daaleman TP, Helton MR, editors. Chronic illness care. Cham: Springer; 2023. p. 269–83. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Williams AP, Challis D, Deber R, Watkins J, Kuluski K, Lum JM, Daub S. Healthc Q. 2009;12(2):95–105. 10.12927/hcq.2009.3974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Andersen R, Newman JF. Societal and individual determinants of medical care utilization in the United States. Milbank Q. 1973;51(1):95–124. 10.2307/3349613. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Andersen RM. Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: does it matter? J Health Soc Behav. 1995;36(1):1–10. 10.2307/2137284. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alkhawaldeh A, ALBashtawy M, Rayan A, Abdalrahim A, Musa A, Eshah N, et al. Application and use of Andersen’s behavioral model as theoretical framework: a systematic literature review from 2012–2021. Iran J Public Health. 2023;52(7):1346–54. 10.18502/ijph.v52i7.13236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372: n71. 10.1136/bmj.n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hong QN, Fàbregues S, Bartlett G, Boardman F, Cargo M, Dagenais P, et al. The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) version 2018 for information professionals and researchers. Educ Inf. 2018;34(4):285–91. 10.3233/efi-180221. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Whittemore R, Knafl K. The integrative review: updated methodology. J Adv Nurs. 2005;52(5):546–53. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03621.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Prigerson HG. Determinants of hospice utilization among terminally ill geriatric patients. Home Health Care Serv Q. 1991;12(4):81–112. 10.1300/J027v12n04_07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen H, Haley WE, Robinson BE, Schonwetter RS. Decisions for hospice care in patients with advanced cancer. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(6):789–97. 10.1046/j.1365-2389.2003.51252.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Csikai EL. Bereaved hospice caregivers’ perceptions of the end-of-life care communication process and the involvement of health care professionals. J Palliat Med. 2006;9(6):1300–9. 10.1089/jpm.2006.9.1300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Choi JE, Miyashita M, Hirai K, Sato K, Morita T, Tsuneto S, et al. Making the decision for home hospice: Perspectives of bereaved Japanese families who had loved ones in home hospice. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2012;42(6):498–505. 10.1093/jjco/hys036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stajduhar KI, Davies B. Variations in and factors influencing family members’ decisions for palliative home care. Palliat Med. 2005;19(1):21–32. 10.1191/0269216305pm963oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Holdsworth L, King A. Preferences for end of life: views of hospice patients, family carers, and community nurse specialists. Int J Palliat Nurs. 2011;17(5):251–5. 10.12968/ijpn.2011.17.5.251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen HC, Wu CY, Hsieh HY, He JS, Hwang SJ, Hsieh HM. Predictors and assessment of hospice use for end-stage renal disease patients in Taiwan. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;19(1):85. 10.3390/ijerph19010085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Obermeyer Z, Powers BW, Makar M, Keating NL, Cutler DM. Physician characteristics strongly predict patient enrollment in hospice. Health Aff (Millwood). 2015;34(6):993–1000. 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.1055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vincent JL. Cultural differences in end-of-life care. Crit Care Med. 2001;29(2):N52–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fang ML, Sixsmith J, Sinclair S, Horst G. A knowledge synthesis of culturally-and spiritually-sensitive end-of-life care: findings from a scoping review. BMC Geriatr. 2016;16:1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bradley N, Lloyd-Williams M, Dowrick C. Effectiveness of palliative care interventions offering social support to people with life-limiting illness-A systematic review. Eur J Cancer Care. 2018;27(3): e12837. 10.1111/ecc.12837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Olsson MM, Windsor C, Chambers S, Green TL. A Scoping review of end-of-life communication in international palliative care guidelines for acute care settings. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2021;62(2):425-37.e2. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.11.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Masoud B, Imane B, Naiire S. Patient awareness of palliative care: systematic review. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2023;13(2):136–42. 10.1136/bmjspcare-2021-003072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sherman DW. A review of the complex role of family caregivers as health team members and second-order patients. Healthcare(Basel). 2019;7(2):63. 10.3390/healthcare7020063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Buss MK, Rock LK, McCarthy EP. Understanding Palliative Care and Hospice: A review for primary care providers. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92(2):280–6. 10.1016/j.mayocp.2016.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Waller A, Sanson-Fisher R, Nair BR, Evans T. Preferences for end-of-life care and decision making among older and seriously ill inpatients: a cross-sectional study. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2020;59(2):187–96. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2019.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ament SM, Couwenberg IM, Boyne JJ, Kleijnen J, Stoffers HE, van den Beuken MH, et al. Tools to help healthcare professionals recognize palliative care needs in patients with advanced heart failure: a systematic review. Palliat Med. 2021;35(1):45–58. 10.1177/0269216320963941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nysaeter T, Olsson C, Sandsdalen T, Hov R, Larsson M. Family caregivers’ preferences for support when caring for a family member with cancer in late palliative phase who wish to die at home–a grounded theory study. BMC Palliat Care. 2024;23(1):15. 10.1186/s12904-024-01350-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pinto S, Lopes S, de Sousa AB, Delalibera M, Gomes B. Patient and family preferences about place of end-of-life care and death: an umbrella review. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2024;67(5):e439–52. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2024.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jordan RI, Allsop MJ, ElMokhallalati Y, Jackson CE, Edwards HL, Chapman EJ, et al. Duration of palliative care before death in international routine practice: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med. 2020;18(1):1–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hui D, Heung Y, Bruera E. Timely palliative care: personalizing the process of referral. Cancers. 2022;14(4):1047. 10.1186/s12916-020-01829-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Karam M, Chouinard MC, Poitras ME, Couturier Y, Vedel I, Grgurevic N, et al. Nursing care coordination for patients with complex needs in primary healthcare: a scoping review. Int J Integr Care. 2021;21(1):16. 10.5334/ijic.5518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lüthi FT, MacDonald I, Amoussou JR, Bernard M, Borasio GD, Ramelet AS. Instruments for the identification of patients in need of palliative care in the hospital setting: a systematic review of measurement properties. JBI Evid Synth. 2022;20(3):761–87. 10.11124/JBIES-20-00555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mahura M, Karle B, Sayers L, Dick-Smith F, Elliott R. Use of the supportive and palliative care indicators tool (SPICT™) for end-of-life discussions: a scoping review. BMC Palliat Care. 2024;23(1):119. 10.1186/s12904-024-01445-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1. Table. Full Search Terms for Databases.

Additional file 2. Table. The Example of Search Strategy in Ovid Medline.

Additional file 3.Table. Factors Influencing the Using Palliative Care and Hospice in Included Studies.

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.