Abstract

Background

Civil servants encounter many psychological challenges in implementing pro-environmental behavior (PEB). However, previous research on the determinants of PEB has largely overlooked the combined impact of multiple psychological resources. Additionally, they described PEB as a behavior that individual’s own to protect the environment (PEB-self), not including the behavior to push others to do these (PEB-other).

Method

First, this study developed a new PEB scale consisting of PEB-self and PEB-other. Second, based on the conservation of resources theory, a three-wave survey was conducted on 1503 Chinese civil servants to explore the psychological mechanisms of PEB formation.

Result

The results indicate that spirituality exerts a positive influence on PEB through the mediating role of public service motivation. Notably, this influence extends beyond self-directed actions to foster spillover effects, whereby civil servants are motivated to persuade others to engage in PEB. Psychological capital significantly moderates this mediating relationship. Specifically, civil servants with higher levels of psychological capital are more likely to participate in PEB, particularly in activities aimed at promoting environmental protection.

Conclusion

This study supports the proposition that integrating multiple psychological resources effectively fosters PEB and expands understanding of PEB within the public sector. It proposes practical strategies to cultivate PEB among civil servants through tiered interventions that enhance these psychological resources via training and workshops, thereby contributing to improved environmental performance in public organizations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s40359-025-03459-5.

Keywords: Spirituality, Pro-environmental behavior, Psychological capital, Public service motivation

Introduction

The Chinese government implements a sustainable development strategy and has carried out long-term and large-scale pollution prevention and ecological environment protection nationwide [1]. As stewards of environmental public resources [2] and agents of environmental public policies [3], civil servants are pivotal in motivating the public to adopt environmental measures and in shaping the environmental performance of public organizations [4, 5]. This requires civil servants not only to lead by example in pro-environmental behavior (PEB), but also to have the courage to speak up and promptly curb the non-environmental behavior of others. PEB refers to all actions taken by individuals to reduce adverse impacts on the environment [6]. In recent years, scholars in the field of public administration have conducted research on civil servants’ PEB based on Azhar’s [7] study, which divided PEB into non-workplace PEB and workplace PEB according to the environment and location where PEB occurs. Few studies examine PEB from the perspective of the behavioral target or investigate its spillover effects, namely individuals’ interventions to influence others’ PEB.

Engaging in PEB often necessitates a substantial investment of psychological resources [8, 9]. Individuals often encounter multiple challenges when engaging in PEB, which can significantly impede its adoption. Specifically, inadequate infrastructure, high economic costs, and a lack of environmental knowledge are pervasive constraints [6]. Compared to an individual’s decision to act alone, influencing others to take action requires taking on more risks and consuming more psychological resources [10], and thereby increase the cost of promoting others’ PEB. As personal costs and situational barriers increase, an individual’s willingness to adopt PEB correspondingly declines [11, 12]. The Conservation of Resources (COR) theory explains this pattern by proposing that individuals seek to acquire, retain, and protect valued resources; threats or losses of these resources produce stress and can lead to behavioral withdrawal [13]. Within this framework, spirituality may operate as a psychological resource that meets the demands of PEB. Spirituality involves actions that stimulate an individual’s inner awareness and motivation [14], galvanizing them to engage actively in social activities aimed at protecting the environment and caring for others [15]. Thus, spirituality can provide a psychological buffer that helps individuals overcome external barriers and low self-efficacy, facilitating greater PEB.

Civil servants commonly display an intrinsic desire to serve the public and an altruistic orientation, often labeled public service motivation (PSM). PSM is defined as the beliefs and attitudes that transcend individual and organizational interests to concern the welfare of a larger political entity, motivating targeted action through interaction with the public [16]. Prior research has indicated that spirituality can encourage employees to seek deeper meaning in their work, thereby motivating them to serve the public selflessly and effectively enhancing their level of PSM [17]. Increased PSM, in turn, has been associated with greater PEB [2]. Therefore, PSM may mediate the effect of spirituality on PEB. In other words, spirituality raises PSM, and higher PSM motivates civil servants to engage in PEB.

Psychological Capital (PsyCap) denotes an individual’s positive psychological state and serves as a strategic resource for coping with adversity [9, 18]. According to COR theory, individuals rich in resources are better able to withstand the impact of resource loss [19]. Within this framework, PsyCap provides individuals with the crucial psychological resources needed to cope with challenges [20]. This implies that civil servants with higher levels of PsyCap may be more resilient to potential risks and more likely to actively adopt and practice PEB. Existing research has shown that PsyCap promotes employees’ extra-role behaviors [21]. Specifically, civil servants with high PsyCap exhibit greater confidence and resilience when facing challenges in their work and personal lives. This positive psychological state enables them to more effectively translate their intrinsic motivations (e.g., PSM) into PEB, which is recognized as a significant form of extra-role behavior [22]. Therefore, among civil servants, PsyCap may moderate the effect of PSM and enhance its capacity to promote proactive engagement in PEB. In summary, grounded in COR theory, this study investigates the following research questions:

RQ 1: How does the spirituality of civil servants influence PEB, considering its impact on both the self and others?

RQ 2: What are the underlying mechanisms through which spirituality affects PEB?

RQ 3: Which factors may moderate this influential mechanism?

China is chosen as the research context to determine how psychological resources promote PEB of civil servants. Governments and public sectors across China have abundant environmental protection practices. In recent years, while China has experienced rapid economic growth, it has also faced the challenges of resource depletion and environmental degradation. The central government gives local governments greater autonomy in environmental governance. Local governments bear the important task of environmental protection [23]. As members of local governments, civil servants therefore play a crucial role in fulfilling these responsibilities.

This study contributes to the existing literature on PEB in the public sector in several ways. First, by exploring the relationship between the spirituality and PEB of civil servants, this study enriches the current research on the impact of psychological resources on PEB. Second, grounded in COR theory, this study investigates the potential mechanisms through which spirituality influences PEB. It suggests that the adoption of PEB requires a combination of various psychological resources, offering a novel perspective on how to enhance PEB among civil servants. Third, this study extends the conceptualization of PEB by proposing a new typology: PEB-self and PEB-other. Based on this distinction, this study has developed a new measurement scale for PEB. Fourth, it offers practical strategies for promoting PEB among civil servants, which can assist public organizations in achieving their environmental performance goals.

Theoretical basis and research hypothesis

Pro-environmental behavior

There are multiple perspectives on the concept and classification of PEB. Scholars in the field of public administration mainly use the classification of PEB based on the place where the behavior occurred, dividing PEB into two dimensions: non-workplace PEB and workplace PEB [2]. In this classification, non-workplace PEB reflects a conscious effort to minimize the negative impact of one’s actions on the natural world [6]. Workplace PEB refers to environmentally friendly behaviors that employees voluntarily engage in, rather than mandatory behaviors stipulated in organizational policies [24]. From the workplace to non-workplace contexts, this classification reveals a critical continuum of action, and provides the foundation for studying PEB in the public sector, but it ignores the impact and spillover effects of individual behaviors on others, and does not explain PEB from the perspective of actors and objects. In addition, research on PEB among Chinese civil servants remains limited, with most studies focusing on Western contexts. Existing literature, often grounded in individualistic cultural settings, has examined how factors such as connectedness to nature and PSM influence PEB [24, 25]. However, in different cultural contexts, PSM may exhibit distinct cultural and institutional characteristics.

Existing PEB scales are valuable for identifying the nature of PEB and exploring its antecedents, but they also have limitations. For example, the general measure of ecological behavior developed by Kaiser [26] aggregates various types of PEB but does not account for differences in ease of implementation. In addition, existing PEB scales mainly focus on tourists [27, 28], enterprise employees [29] and other groups, but pay less attention to public employees and civil servants. In China, civil servants play an important role in environmental governance. They are expected not only to practice PEB themselves but also to guide public participation, discourage and stop environmentally damaging behaviors, and serve as supervisors and guardians of environmental protection [30].

Moreover, although existing research on PEB has recognized the existence of spillover effects, most studies have concentrated on behavioral, temporal, and contextual spillovers [31], devoting limited attention to spillover effects that occur between individuals. Civil servants’ environmental responsibilities extend beyond personal sustainable practices and they are also positioned to act as environmental advocates. Therefore, PEB should be more precisely defined and differentiated, and a dedicated measurement scale should be developed for civil servants.

Recognizing that PEB encompasses not only individual actions but also interpersonal influence [32], the present study conceptualizes PEB along two dimensions: PEB-self and PEB-other. PEB-self refers to an individual’s direct engagement in behaviors that contribute to environmental preservation, such as actively participating in tree-planting activities or turning off a faucet when not in use. PEB-other refers to behaviors aimed at encouraging, persuading, or enabling others to engage in PEBs, such as encouraging others to purchase energy-efficient appliances or stopping someone from littering. The critical distinction is that PEB-other involves the transmission of pro-environmental influence, positioning other people as the ultimate executors of PEB. Table 1 compares the PEB dimensions proposed in the present study with those identified in existing literature about PEB of civil servants.

Table 1.

Compare PEB dimensions

| Dimension name | Pro-environmental behavior-self vs. Pro-environmental behavior-other | Workplace pro-environmental behavior vs. Non-workplace pro-environmental behavior |

|---|---|---|

| Core Classification Logic | Focus on who performs the ultimate environmental action: the self or others? | Focus on the physical context in which the behavior occurs |

| Definition |

Pro-environmental behavior-self : An individual’s direct engagement in behaviors that contribute to environmental preservation, such as actively participating in tree-planting activities or turning off a faucet when not in use. Pro-environmental behavior-other : Behaviors aimed at encouraging, persuading, or enabling others to engage in pro-environmental behaviors, such as promoting the purchase of energy-efficient appliances or intervening to prevent littering. |

Workplace pro-environmental behavior : Environmentally friendly behaviors that employees voluntarily engage in, rather than mandatory behaviors stipulated in organizational policies. Non-workplace pro-environmental behavior : A conscious effort to minimize the negative impact of one’s actions on the natural world. |

| Examples |

Pro-environmental behavior-self : Actively participating in tree planting activities or turning off a faucet when it is not in use. Pro-environmental behavior-other : Encouraging others to purchase energy-efficient appliances or stopping someone from littering. |

Workplace pro-environmental behavior : Set the computer to energy-saving mode in the office; raise the temperature of the air conditioning or reduce the use of heating. Non-workplace pro-environmental behavior : Household energy conservation, water conservation, and recycling of daily waste; purchasing organic food, eco-friendly products, etc. Such behaviors often require additional expenditure. |

| Strengths | This study extends the conceptualization of pro-environmental behavior from a dyadic “individual–environment” interaction to a triadic “individual–others–environment” relationship. This shift highlights the social influence dimension of pro-environmental behavior and provides a theoretical basis for cultivating environmental advocates rather than merely environmental performers. | This classification approach categorizes based on scenarios, making measurements more aligned with real-life situations and directly guiding differentiated policies. |

| Limitations | The two types of behaviors may sometimes co-occur (e.g., planting trees while simultaneously encouraging peers), making the boundary between them prone to ambiguity. | It overlooks cross-situational psychological consistency, the social attributes of individuals in influencing others, as well as factors such as technical complexity, cultural variability, and intra-organizational heterogeneity. |

Spirituality and pro-environmental behavior

Although the academic community has not reached a consensus on the definition of spirituality, in the civil service context it does not refer to religious belief per se. Rather, it represents an intrinsic motivational force that closely links personal meaning in life with the pursuit of serving others and contributing to society [33]. To precisely delineate its unique role, it is essential to differentiate spirituality from related psychological constructs such as moral identity and values. Spirituality is rooted in a deep sense of purpose that connects personal meaning with service to others, whereas moral identity focuses more narrowly on the salience of moral traits, such as honesty and fairness, within one’s self-concept [34]. Values, in turn, represent a broader belief system, often shaped by societal or organizational contexts, that guides judgments about what is important or right [35]. Thus, while these constructs are related, they operate at different psychological levels: spirituality provides intrinsic motivation, moral identity relates to self-concept, and values offer a guiding framework [36, 37]. As such, spirituality functions as a powerful motivational resource, energizing individuals to engage in prosocial activities that promote collective well-being [38]. As a powerful motivational resource, spirituality can energize individuals and drive them to engage in prosocial activities that promote collective well-being [38]. According to the COR theory, individuals strive to accumulate and protect resources that help them cope with stress and challenges [13]. As an intrinsic belief system and value orientation, spirituality can provide civil servants with profound psychological resources, including a sense of meaning, belonging, and inner peace [39]. These resources not only mitigate the psychological depletion individuals may feel when confronting environmental issues but also provide a solid foundation for their subsequent PEB [40]. COR theory further suggests that resource gains can stimulate additional resource investment, a process known as a “resource gain spiral” [13]. Civil servants with high levels of spirituality are more inclined to invest their emotional and belief-based resources in PEB, such as voluntarily participating in energy conservation projects or promoting green office practices. Positive feedback from such investments, including enhanced self-esteem, further enriches their resource pool and sustains their engagement in environmental initiatives [41]. Empirical evidence supports that activating spirituality-related resources can significantly foster prosocial attitudes and behaviors [42]. Individuals with high spirituality often cultivate a stronger connection with the external world [43], which may heighten their concern for social and environmental issues and reinforce their commitment to environmental protection and sustainable development [44]. Therefore, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H1 Spirituality has a positive effect on PEB-self among civil servants.

H2 Spirituality has a positive effect on PEB-other among civil servants.

The mediating role of public service motivation

PSM is a personal characteristic that reflects an individual’s intrinsic desire to serve others and contribute to societal welfare [45]. Employees in public sectors often exhibit higher levels of PSM because their work inherently provides opportunities to actively engage in public service and fulfill civic duties [33]. Spirituality furnishes deep psychological resources such as a sense of meaning, belonging, and inner peace [39], which function as “key resource reservoirs” in the COR theory [13, 46]. Civil servants with higher levels of spirituality tend to align their values with the ideals of serving society and caring for the environment [47]. By enhancing value orientation and personal meaning, spirituality strengthens PSM, encouraging a commitment to selfless service [48–50]. In this way, spirituality enhances the internal motivational resource of PSM by imbuing public service goals with greater significance.

PSM itself represents a stable internal resource that increases goal clarity and behavioral persistence [51], It encourages civil servants to invest energy, time, and attention in environmental responsibilities, thereby increasing the likelihood of PEB. Empirical studies have confirmed the positive relationship between PSM and PEB [2, 24]. The COR theory explains this association through the “resource gain spiral,” whereby high PSM civil servants are more likely to participate in the design and implementation of green policies and initiate energy-saving activities [52]. The investment of their time, skills, and interpersonal resources yields gains such as organizational recognition and a sense of intrinsic achievement, creating a virtuous cycle that sustains further PEB [53, 54]. In addition, PSM heightens awareness of environmental degradation as a threat to public resources, activating a “resource protection motivation” that promotes PEB to safeguard the collective resource base. Therefore, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H3 PSM mediates the relationship between spirituality and PEB-self among civil servants.

H4 PSM mediates the relationship between spirituality and PEB-other among civil servants.

The moderating role of psychological capital

Existing research demonstrates that PsyCap influences prosocial and organizational citizenship behaviors [55, 56], and PEB can be regarded as a form of such behavior in the environmental domain [57]. In COR theory terms, high PsyCap constitutes a “resource reserve” [20] that lowers the perceived costs of PEB, such as time or financial expenditure, and thus facilitates environmentally responsible choices [19]. PEB may also be conceptualized as a “resource preservation” strategy, where actions like waste reduction and recycling serve to protect environmental resources and sustain the broader resource system that supports human survival and development [58]. Individuals with higher PsyCap, who tend to prioritize collective welfare over personal gain [59, 60], are more likely to internalize the value of such preservation and incorporate PEB into their routines.

PsyCap plays a pivotal role in sustaining motivation. The positive self-appraisals embedded in PsyCap provide a sense of agency that enables individuals to translate PSM into concrete environmental actions [61]. When PsyCap is high, the altruistic motives inherent in PSM are more readily transformed into sustained behavioral engagement, creating resource gain spirals. When PsyCap is low, resource deficits may weaken this motivational transfer, reducing the impact of PSM on PEB [62, 63]. PsyCap can interact with PSM to form “resource caravan passageways” [64], amplifying the influence of one resource through the presence of another. From a COR perspective, high-PsyCap individuals possess not only abundant resources but also strong capabilities for resource protection and recovery. Encouraging others to engage in PEB demands greater cognitive and emotional investment than practicing PEB oneself, and it carries risks such as perceived ineffectiveness or social rejection [65, 66]. Under these conditions, high PsyCap can buffer against potential resource loss, preserving the motivational link between PSM and PEB-other. In contrast, low PsyCap may lead to a “motivation–behavior decoupling” due to resource depletion [67, 68]. Thus, PsyCap is expected to exert a stronger moderating effect on PEB-other than on PEB-self. The following hypotheses are proposed:

H5 PsyCap positively moderates the mediating effect of PSM between spirituality and PEB-self among civil servants.

H6 PsyCap positively moderates the mediating effect of PSM between spirituality and PEB-other among civil servants.

H7 The moderating effect of PsyCap is stronger for the pathway involving PEB-other than for the pathway involving PEB-self.

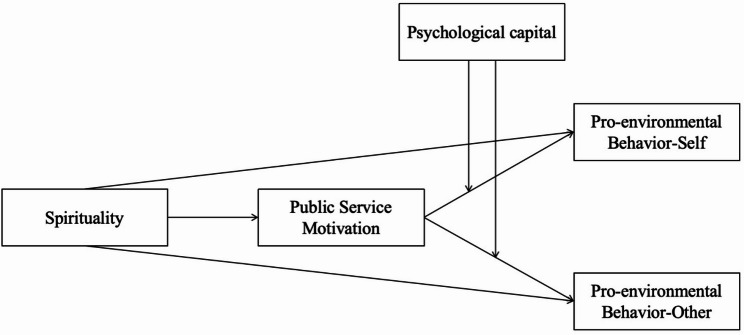

Based on H3, H4, H5 and H6, this study proposed a moderated mediation model to test the positive influence of spirituality and PEB among civil servants via PSM, as well as the moderating role of PsyCap in this process. Thus, the following hypotheses are proposed and the research model is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Theoretical model of this study

H8 PsyCap moderates the mediating role of PSM between spirituality and PEB-self among civil servants. Specifically, when the PsyCap is high, spirituality exerts a stronger influence on PEB-self among civil servants through PSM.

H9 PsyCap moderates the mediating role of PSM between spirituality and PEB-other among civil servants. Specifically, when the PsyCap is high, spirituality exerts a stronger influence on PEB-other among civil servants through PSM.

Methods

Target population and sampling frame

This study surveyed grassroots civil servants from four Chinese provinces/municipalities: Beijing, Zhejiang, Guangdong, and Sichuan. These regions represent critical geographical and socioeconomic variation across Northern, Eastern, Southern, and Western China, encompassing diverse economic development levels, environmental challenges, and governance approaches [1, 69]. Provincial selection was further justified by their documented prioritization of environmental performance alongside persistent sustainability challenges requiring civil servant-public collaboration [70–73].

Data collection procedure

To reduce common method bias, this study conducted a three-wave survey with 7–10 days intervals between waves was administered between October 2022 and January 2023. To ensure respondent anonymity while enabling longitudinal matching, participants generated unique identification codes. A convenience sampling technique was used for this study. Specifically, the survey was disseminated through municipal government general offices in the target regions, with officials forwarding invitations to colleagues and subordinate departments. Considering that Chinese civil servants generally have reservations about participating in academic research and have certain concerns about expressing their true thoughts [42], the questionnaire is anonymous and voluntary. Time 1 (T1) commenced on October 15, 2022. Data on spirituality and PSM were collected from subordinates. At T2, this study gathered data on the PsyCap. At T3, the participants were invited to complete the measures of PEB, and provide personal demographic information. From 2098 questionnaires distributed, 1682 responses were matched across all waves. After removing invalid responses (e.g., short response times, straight-lining patterns, failed attention checks), the final sample comprised 1503 questionnaires, with an initial response rate of 80.17% and valid response rate of 71.64%, were kept for statistical analysis. Sample characteristics are detailed in Table 2. The sample comprised 49.4% male and 50.6% female. The majority fell within the 31–35 age cohort (30.3%), with 30.7% reporting 6–10 years of work experience. Most participants reported married status (75.8%). Regarding educational attainment, the largest proportion held bachelor’s degrees (40.5%). In terms of job grade, staff member constituted the majority (69.5%). Regarding geographical distribution, 23.8% of the participants were from Beijing, 25.6% from Zhejiang, 26.4% from Guangdong, and 24.2% from Sichuan. Chinese government departments can generally be classified into two categories. Line departments are administrative entities responsible for macro-level decision-making, overall coordination, and ultimate accountability, such as grassroots governments. In contrast, functional departments are specialized agencies tasked with planning, organizing, and managing specific policy domains, such as finance bureaus. In our sample, 20.9% of respondents were from line departments, while 79.1% were from functional departments. This distribution aligns closely with the demographic structure of Chinese civil servants.

Table 2.

Profile of participants

| N(number) | Percentage(%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 742 | 49.4 |

| Female | 761 | 50.6 | |

| Age | 20–25 | 159 | 10.6 |

| 26–30 | 327 | 21.8 | |

| 31–35 | 455 | 30.3 | |

| 36–40 | 349 | 23.2 | |

| 41–45 | 137 | 9.1 | |

| 46–50 | 52 | 3.5 | |

| ≥ 51 | 24 | 1.6 | |

| Marital status | Unmarried | 364 | 24.2 |

| Married | 1139 | 75.8 | |

| Education | Associate or low degree | 223 | 14.8 |

| Bachelor’s degree | 608 | 40.5 | |

| Master’s degree | 521 | 34.7 | |

| Doctorate degree | 151 | 10.0 | |

| Work Experience | 1–5 years | 310 | 20.6 |

| 6–10 years | 462 | 30.7 | |

| 11-15years | 369 | 24.6 | |

| 16–20 years | 220 | 14.6 | |

| 21–25 years | 65 | 4.3 | |

| ≥ 26 years | 77 | 5.1 | |

| Job grade | Staff member | 1045 | 69.5 |

| Deputy-section-head level | 351 | 23.4 | |

| Section-head level | 75 | 5.0 | |

| Deputy-division-head level | 15 | 1.0 | |

| Division-head level | 13 | 0.9 | |

| Deputy-bureau-director level | 3 | 0.2 | |

| Bureau-director level | 1 | 0.1 | |

| Geographical distribution | Beijing | 357 | 23.8 |

| Zhejiang | 385 | 25.6 | |

| Guangdong | 398 | 26.4 | |

| Sichuan | 363 | 24.2 | |

| Types of government departments | Line departments | 314 | 20.9 |

| Functional departments | 1189 | 79.1 |

Measures

PEB

To facilitate a more precise investigation of civil servants’ PEB, this study developed a novel PEB scale. Drawing from our theoretical conceptualization, the scale assesses two distinct dimensions: PEB-self and PEB-other. To ensure the clear operationalization and accurate measurement of these constructs, the following specific guidelines were established for their distinction: PEB-self was operationally defined as behaviors where the individual is the direct and final executor of the pro-environmental action. The focus is on personal conduct and direct environmental impact, regardless of whether others are present or involved. Scale items for this dimension capture actions such as “In my daily life, I ensure that I do not waste even a single drop of water.” or “I participate in tree-planting activities.” PEB-other was defined as interpersonal behaviors aimed at encouraging, persuading, supervising, or enabling another person to perform a pro-environmental action. In this case, the civil servant acts as an influencer, advocate, or guide, while the environmental benefit is ultimately realized through the behavior of another individual. Scale items for this dimension capture actions like “I encourage others to purchase energy-efficient household appliances.” or “When I observe someone littering or discarding cigarette butts, I step in to stop them.” The primary criterion for distinguishing the two dimensions is the actor who ultimately performs the environmental action. If the action’s environmental benefit is realized directly by the civil servant’s own behavior, it was classified as PEB-self. Conversely, if the action’s primary mechanism is interpersonal communication or intervention to prompt another individual’s behavior, it was classified as PEB-other. All items in the final scale were developed and reviewed against this core principle to ensure robust discriminant validity between the two subscales.

Scale development began with semi-structured interviews conducted with civil servants from a range of government agencies (e.g., the prosecutor’s office and the legal affairs department). Interview transcripts were subjected to textual analysis to extract core behaviors and item content. Drawing on existing PEB measures [8, 74, 75], an initial pool of 28 items was generated. Item order was randomized and the pool was evaluated by a panel of domain scholars and practitioners, who classified and rated each item; items exhibiting poor consensus or substantive controversy were removed, yielding a 24-item PEB scale. Responses were collected on a five-point Likert scale (1 = “completely disagree”; 5 = “completely agree”), and the complete English version of the instrument is provided in the Supplementary Materials.

The scale was then empirically validated in a survey of 364 civil servants. For item discrimination analysis, respondents were classified into high- and low-score groups corresponding to the top 27% and bottom 27% of total scale scores. Independent-samples t-tests were performed for each item to compare these groups, and all 24 items differed significantly between the high-score and low-score groups (p < 0.05), indicating satisfactory item discrimination. The results of exploratory factor analysis (EFA) showed that the KMO and Bartlett’s spherical test value was 0.96 (p < 0.01), indicating that the PEB scale was suitable for factor analysis. Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted on the 24 retained items. A single-factor model did not meet conventional fit criteria (χ2/df = 3.66, RMSEA = 0.09, CFI = 0.86, TLI = 0.84, SRMR = 0.06). In contrast, the two-dimensional model evaluated in this study demonstrated excellent fit to the data (χ2/df = 1.28, RMSEA = 0.02, CFI = 0.99, TLI = 0.98, SRMR = 0.03), markedly outperforming the single-factor solution. Internal consistency for the scale was satisfactory (Cronbach’s α = 0.89).

Spirituality

A 28-item spirituality scale developed by Howden [76] was adopted, consisting of four dimensions: unifying interconnectedness, innerness or inner resources, purpose and meaning in life, and transcendence. This scale is well-established [77] and has been applied in studies involving Chinese participants, demonstrating its cultural adaptability within the Chinese context [78]. Sample items included, “I feel a connection to all of life.” “I have experienced moments of peace in a devastating event.” and “My life has meaning and purpose.” “My innerness or an inner resource helps me deal with uncertainty in life.” and so on. The Cronbach’s α was 0.87. CFA indicated acceptable structural validity: χ2/df = 2.63, RMSEA = 0.03, CFI = 0.98, TLI = 0.97, SRMR = 0.03.

PSM

Adopting the scale compiled by Coursey and Pandey [79] and drawing on the conclusions of empirical studies by Azhar and Yang [2], this study removed the items related to “attraction to policy making” and “sympathy”, and extracted the remaining 5-items are measured. Sample items included, “I unselfishly contribute to my community.” “Meaningful public service is very important to me.” and “I consider public service my civic duty.” The Cronbach’s α was 0.85. CFA indicated acceptable structural validity: χ2/df = 6.68, RMSEA = 0.06, CFI = 0.99, TLI = 0.99, SRMR = 0.01.

PsyCap

A short version of the 12-item PsyCap scale developed by Luthans et al. [9] based on the Chinese context was adopted, including four dimensions: confidence, hope, resilience and optimism. Sample items included, “I am confident in presenting things within my scope of work in meetings with management.” “If I find myself in a difficult situation at work, I can think of many ways to get out of it.” “I am usually comfortable with stress at work.” “I am optimistic about what will happen to my job in the future.” The Cronbach’s α was 0.87. CFA indicated acceptable structural validity: χ2/df = 4.01, RMSEA = 0.05, CFI = 0.98, TLI = 0.98, SRMR = 0.02.

Analysis strategy

This study used SPSS 26.0 and Mplus 8.0 for data analysis. Using SPSS 26.0 for descriptive statistics, correlation analysis, and regression analysis to explore the relationship between spirituality, PSM, PsyCap, and PEB. Structural equation modeling (SEM) and CFA were employed in Mplus 8.0. Specifically, CFA was used to measure the effectiveness and reliability of the model. SEM was used to test the mediating and moderating roles. Firstly, the mediating role of PSM in spirituality impact on PEB was verified. The path model was estimated using bias-corrected 95% confidence intervals (CIs) from bootstrapping method (N = 5000) to validate the mediating effect [80]. Subsequently, the moderating roles of PsyCap were verified.

Results

Common method variance (CMV) check

Harman’s one-factor analysis was used to examine CMV. The unrotated solution yielded ten factors with eigenvalues greater than 1, and the first factor explained 23.91% of the total variance that well below the conventional 40% cutoff, indicating that serious common method bias is unlikely in the present data [81]. Besides, to identify CMV, CFA was conducted to examine the fit of models (see Table 3). In addition, this study also employed the unmeasured latent method construct (ULMC) [82] to examine CMV. The results showed that the four-factor model fit our data reasonably well (χ2/df = 2.38, RMSEA = 0.03, CFI = 0.95, TLI = 0.94, SRMR = 0.03), and adding a latent CMV factor into our theoretical constructs, did not improve the model fit significantly( χ2/df = 2.17, RMSEA = 0.03, CFI = 0.96, TLI = 0.95, SRMR = 0.03). All of the aforementioned results indicated that the concern for CMV can be minimized.

Table 3.

Confirmatory factor analysis results

| Model | χ2 | df | χ2/df | CFI | TLI | RMSEA | SRMR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Four-factor model | 5379.24 | 2261 | 2.38 | 0.95 | 0.94 | 0.03 | 0.03 |

|

Three-factor model (Spirituality and PsyCap combine) |

8422.87 | 2264 | 3.72 | 0.89 | 0.89 | 0.04 | 0.16 |

|

Two-factor model (Spirituality, PsyCap and PEB combine) |

11315.41 | 2266 | 4.99 | 0.84 | 0.84 | 0.05 | 0.12 |

| Single-factor model | 36613.93 | 2277 | 16.08 | 0.40 | 0.38 | 0.10 | 0.14 |

Notes. All alternative models were compared to the hypothesized four-factor model. CFI: comparative fit index; RMSEA: root mean square error of approximation; TLI: Tucker–Lewis index; SRMR: standardized root mean square residual; PsyCap: Psychological capital; PEB: Pro-environmental behavior

Descriptive statistics and correlation analysis

The correlation analysis of the variables in this study was shown in Table 4. PEB-self was significantly positive correlated with spirituality (r = 0.32, p < 0.001) and PSM (r = 0.39, p < 0.001). PEB-other was significantly positive correlated with spirituality (r = 0.31, p < 0.001) and PSM (r = 0.37, p < 0.001). PSM was significantly positively correlated with spirituality (r = 0.27, p < 0.001).

Table 4.

Descriptive statistics and correlation analysis of variables (N = 1503)

| Variable | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.Gender | 0.51 | 0.50 | 1 | ||||||||

| 2.Age | 3.15 | 1.33 | -0.01 | 1 | |||||||

| 3.Marital status | 0.76 | 0.43 | 0.03 | 0.51*** | 1 | ||||||

| 4.Education | 2.40 | 0.86 | 0.01 | -0.02 | 0.05 | 1 | |||||

| 5.Work experience | 2.67 | 1.34 | -0.01 | 0.86*** | -0.41*** | -0.11*** | 1 | ||||

| 6.Job grade | 1.41 | 0.75 | 0.01 | 0.39*** | 0.22*** | -0.01 | 0.29*** | 1 | |||

| 7.Spirituality | 3.14 | 0.62 | -0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 1 | ||

| 8.PSM | 3.11 | 1.05 | 0.03 | -0.02 | 0.01 | 0.02 | -0.04 | 0.01 | 0.27*** | 1 | |

| 9.PsyCap | 3.39 | 0.69 | 0.02 | 0.01 | -0.01 | -0.02 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.08** | -0.03 | 1 |

| 10.PEB-self | 3.14 | 0.75 | -0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.32*** | 0.39*** | 0.04 |

| 11.PEB-other | 3.14 | 0.74 | 0.01 | -0.02 | -0.01 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.31*** | 0.37*** | 0.04 |

Note. PSM: Public service motivation; PsyCap: Psychological capital; PEB: Pro-environmental behavior

*p < 0.05. **p < 0.01. ***p < 0.001

The relationship between spirituality and PEB

To examine the relationship between spirituality and PEB, this study employed regression analysis to test H1 and H2. According to the validation results in Table 5, spirituality was positively associated with PEB-self (β = 0.39, SE = 0.03, t = 13.15, p < 0.001) and PEB-other (β = 0.37, SE = 0.03, t = 12.39, p < 0.001). Thus, H1 and H2 were supported. The effect sizes indicate that a one standard deviation increase in spirituality was associated with approximately a 0.39 SD increase in PEB-self and a 0.37 SD increase in PEB-other, suggesting that spirituality plays a moderate to strong role in shaping civil servants’ environmentally responsible behaviors.

Table 5.

Regression analysis

| Variable | PEB-self | PEB-other | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | SE | t | β | SE | t | |

| Gender | -0.01 | 0.04 | -0.31 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.48 |

| Age | -0.02 | 0.03 | -0.82 | -0.03 | 0.03 | -1.15 |

| Marital status | 0.00 | 0.05 | 0.08 | 0.00 | 0.05 | -0.06 |

| Education | 0.03 | 0.02 | 1.14 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.07 |

| Work experience | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.63 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.93 |

| Job grade | 0.05 | 0.03 | 1.94 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.51 |

| Spirituality | 0.39*** | 0.03 | 13.15 | 0.37*** | 0.03 | 12.39 |

| R 2 | 0.11 | 0.09 | ||||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.10 | 0.09 | ||||

| F | 25.77*** | 22.26*** | ||||

Note. PEB: Pro-environmental behavior

*p < 0.05. **p < 0.01. ***p < 0.001

The mediating role of PSM

To test the mediating effect, this study employed bootstrapping method. Table 6 showed that the indirect effect of spirituality on PEB-self was 0.09 [LLCI = 0.07, ULCI = 0.11], and the direct effect was 0.23 [LLCI = 0.19, ULCI = 0.28], which indicating that PSM plays a partial mediating role in spirituality and PEB-self. The indirect effect of spirituality on PEB-other was 0.22 [LLCI = 0.17, ULCI = 0.27], and the direct effect was 0.09 [LLCI = 0.07, ULCI = 0.11], which indicating that PSM plays a partial mediating role in spirituality and PEB-other. These results indicate that PSM partially mediates both relationships. However, the practical implications differ. For PEB-other, the indirect effect (0.22) was substantially larger than the direct effect (0.09), suggesting that PSM is the primary mechanism through which spirituality influences advocacy-oriented environmental behaviors. A major portion of spirituality’s impact on encouraging others is channeled through an enhanced PSM. Thus, H3 and H4 were supported.

Table 6.

The mediating role of psychological safety

| Path | Effect | SE | LLCI | ULCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spirituality — PEB-self | 0.23*** | 0.02 | 0.19 | 0.28 |

| Spirituality — PSM — PEB-self | 0.09*** | 0.01 | 0.07 | 0.11 |

| Spirituality — PEB-other | 0.22*** | 0.02 | 0.17 | 0.27 |

| Spirituality — PSM — PEB-other | 0.09*** | 0.10 | 0.07 | 0.11 |

Note. PSM: Public service motivation; PEB: Pro-environmental behavior

*p < 0.05. **p < 0.01. ***p < 0.001

The moderating role of PsyCap

In order to explore the moderating effect of PsyCap, all variables were mean centered to minimize multicollinearity [83]. Table 7 showed that the interaction term of PsyCap and PSM also had a significant positive effect on PEB-self (β = 0.06, SE = 0.02, t = 3.31, p < 0.001), indicating that PsyCap plays a significant positive moderating role in the relationship between PSM and PEB-self. Besides, the interaction term of PsyCap and PSM also had a significant positive effect on PEB-other (β = 0.08, SE = 0.02, t = 4.48, p < 0.001), indicating that PsyCap plays a significant positive moderating role in the relationship between PSM and PEB-other. Therefore, H5 and H6 were proved. The effect sizes suggest that the influence of PSM on PEB increases by 6% for PEB-self and 8% for PEB-other at higher levels of PsyCap. Meanwhile, PsyCap did not significantly predict PEB-self (β = 0.04, p >0.05) but had a small direct effect on PEB-other (β = 0.04, p = 0.03). In contrast to PEB-self, PsyCap had a more significant role in influencing PEB-other. Therefore, it can be inferred that compared to PEB-self, PEB-other requires more PsyCap, and H7 were proved.

Table 7.

Results of the moderating role of PsyCap

| Variable | PEB-self | PEB-other | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | SE | t | β | SE | t | ||

| Gender | -0.03 | 0.04 | -0.83 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.06 | |

| Age | -0.03 | 0.03 | -1.15 | -0.04 | 0.03 | -1.47 | |

| Marital status | -0.01 | 0.05 | -0.17 | -0.01 | 0.05 | -0.28 | |

| Education | 0.03 | 0.02 | 1.50 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.36 | |

| Work experience | 0.04 | 0.03 | 1.35 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 1.60 | |

| Job grade | 0.05 | 0.03 | 1.86 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.36 | |

| PSM | 0.29*** | 0.02 | 16.47 | 0.27*** | 0.02 | 15.49 | |

| PsyCap | 0.04 | 0.02 | 1.95 | 0.04* | 0.02 | 2.15 | |

| PSM × PsyCap | 0.06*** | 0.02 | 3.31 | 0.08*** | 0.02 | 4.48 | |

| R 2 | 0.17 | 0.15 | |||||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.16 | 0.15 | |||||

| F | 33.07*** | 30.21*** | |||||

Note. PSM: Public service motivation; PsyCap: Psychological capital; PEB: Pro-environmental behavior

*p < 0.05. **p < 0.01. ***p < 0.001

The mediating roles of PSM under high-low PsyCap were further tested. According to Table 8, when civil servants had low levels of PsyCap (-1SD), the mediating role of PSM between spirituality and PEB-self was 0.09 [LLCI = 0.07, ULCI = 0.12]. At high PsyCap levels (+ 1 SD), this effect increased to 0.13 [LLCI = 0.11, ULCI = 0.16], representing a 44% enhancement in the indirect effect. Similarly, for PEB-other, the mediating effect increased from 0.07 [LLCI = 0.05, ULCI = 0.10] under low PsyCap to 0.14 [LLCI = 0.11, ULCI = 0.16] under high PsyCap, which reflects a 100% amplification. These findings suggest that PsyCap substantially strengthens the role of PSM, particularly for PEB-other. Meanwhile, the mediating process from spirituality to PEB-self via PSM was statistically moderated by PsyCap (△γ = 0.04, p < 0.05), and the mediating process from spirituality to PEB-other via PSM was statistically moderated by PsyCap (△γ = 0.07, p < 0.001). This study showed that compared to PEB-self, PsyCap had a more significant moderating role on PEB-other. Thus, H7, H8 and H9 were supported.

Table 8.

Results of the mediating role of PSM under high-low PsyCap

| Type of PEB | Mediating effect | SE | LLCI | ULCI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PEB-self | Low PsyCap(-1 SD) | 0.09*** | 0.02 | 0.07 | 0.12 |

| High PsyCap(+ 1 SD) | 0.13*** | 0.02 | 0.11 | 0.16 | |

| Between-group difference (High-Low) | 0.04* | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.07 | |

| PEB-other | Low PsyCap(-1 SD) | 0.07*** | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.10 |

| High PsyCap(+ 1 SD) | 0.14*** | 0.02 | 0.11 | 0.16 | |

| Between-group difference (High-Low) | 0.07*** | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.07 |

Note. PSM: Public service motivation; PsyCap: Psychological capital; PEB: Pro-environmental behavior

*p < 0.05. **p < 0.01. ***p < 0.001

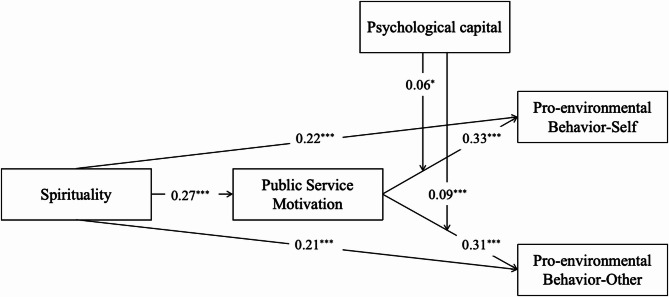

Furthermore, the proposed moderated mediation model was tested using SEM as depicted in Fig. 2. The results revealed that PsyCap significantly moderates the indirect effect of spirituality on both PEB-self and PEB-other through PSM, thus providing support for H8 and H9. Notably, a comparison of the interaction terms indicated that the moderating effect of PsyCap was substantially stronger on the path to PEB-other (β = 0.09, p < 0.001) than on the path to PEB-self (β = 0.06, p < 0.05). This finding demonstrates that PsyCap exerts a more potent positive moderating influence on PEB-other, offering robust secondary support for H7.

Fig. 2.

Moderated mediation model. Note. *p < 0.05. **p < 0.01. ***p < 0.001

Discussion

This study focuses on the PEB-self and PEB-other among civil servants, exploring the combined effects of multiple psychological resources. Results showed that PSM mediated the relationship between spirituality and PEBs, while PsyCap moderated this relationship. Specifically, PsyCap strengthened the indirect effect of the PSM on the relationship between spirituality and PEBs, and compared with PEB-self, PsyCap exerted a stronger moderating effect on PEB-other.

Theory contributions

First, this study validates the effectiveness of COR theory in explaining PEB among civil servants and extends the understanding of spirituality as both an antecedent and consequence of PEB. Spirituality plays a pivotal role in fostering PEB, as civil servants with higher levels of spirituality are more inclined to contribute to society and actively engage in behaviors that benefit others, their organizations, and the environment [41, 42]. According to COR theory, individuals must invest effort and resources to engage in PEB. As a higher-order psychological resource, spirituality equips individuals with self-transcendence, external connectedness, and proactive resource acquisition, thereby supporting their capacity to undertake PEB. Furthermore, this study demonstrates a degree of cross-cultural generalizability regarding the relationship between spirituality and PEB. Although previous studies have shown that spirituality promotes PEB, most have focused on Western contexts, primarily investigating the role of personal values in shaping civil servants’ environmental actions [84]. In China, spirituality is intertwined with Confucian traditions and collectivist values, emphasizing self-discipline, modesty, and alignment with collective goals [37]. For Chinese civil servants, spirituality is institutionally embedded in norms of deliberative democracy, professional ethics, and the state’s ecological civilization strategy, transforming it from a private orientation into a motivational force [85, 86]. In this context, PEB is framed as a convergence of professional duty, moral obligation, and personal belief, thereby strengthening intrinsic motivation.

Second, this study delves into how various psychological resources shape civil servants’ PEB, highlighting the critical role of resource configurations. Spirituality acts as a resource initiator, providing a sense of meaning and value alignment with environmental issues. PSM functions as a motivational converter, transforming the value orientations derived from spirituality into concrete pro-environmental actions, consistent with prior findings [2, 17, 49]. Besides, PsyCap serves as both an amplifier and a moderator, enhancing the translation of PSM into sustained and effective behavior, particularly in the context of PEB-other. This may be because PEB-other often entails direct intervention in others’ behaviors or the environment, thereby exposing individuals to greater social risks and pressures [10]. From the perspective of COR theory, compared with PEB-self, PEB-other demands additional investments of social, emotional, and risk-related resources, such as relational capital, the capacity to manage resistance, and the potential for conflict while subsequent resource replenishment remains highly uncertain [87]. This synergistic resource framework helps explain why configurations of resources are more predictive of complex extra-role behaviors than any single resource alone [88], a view that aligns with recent developments in COR theory emphasizing the importance of resource caravan passageways, thereby advancing theoretical understanding [89].

Third, the present study proposes a novel taxonomy of PEB. By distinguishing PEB-self from PEB-other, it offers a more fine-grained account of spillover effects and thereby extends the conceptualization of PEB. Prior work has examined spillover phenomena such as the extent to which one person’s PEB influences the performance of another distinct PEB, the temporal persistence of an individual’s PEB, and the consistency of an individual’s PEB across contexts [31]. However, these phenomena are essentially intra-individual, and thus prior research has largely neglected inter-individual spillover, defined as the process by which one person’s behavior shapes the behaviors of others. Moreover, existing PEB taxonomies have typically emphasized cost, environmental context, or strategic considerations [4, 46, 90], paying limited attention to spillover dynamics and to the self-other attributes of PEB. To address these gaps, the present study advances a typology grounded in the question “who is the ultimate actor of the PEB?” explicitly incorporating inter-individual spillover by classifying PEB into PEB-self and PEB-other, and develops a two-dimensional PEB scale. This contribution supplies a more precise measurement tool for in-depth PEB research, enriches the existing research paradigm, and establishes a new theoretical basis for future inquiry.

Practical implications

This study provides practical guidance for further motivating civil servants to engage in PEB. First, spirituality form the foundation for PEB. Public organizations should adopt targeted, tiered strategies to cultivate these qualities and strengthen ideological guidance. For junior civil servants, environmental ethics should be incorporated into onboarding to foster responsibility and habitual PEB (e.g., recycling, energy conservation). For mid-level and senior civil servants, activities that increase interaction with the public can enhance perceived work meaningfulness and reinforce alignment with governmental values, thereby preparing them for more demanding environmental initiatives [91].

Second, PSM facilitates PEB. Agencies should establish comprehensive incentive systems and organizational arrangements to stimulate intrinsic motivation and support action. Honorific recognition combined with fair performance evaluations helps civil servants perceive that their contributions are rewarded, reinforcing commitment to public service [92, 93]. Equally important is fostering psychological well-being and coping capability. Mid-level civil servants should receive training to implement equitable appraisal systems that acknowledge both PEB-self and PEB-other.

Third, PsyCap underpins high-impact PEB. Because PEB-other often requires confidence, optimism, and resilience, interventions should go beyond general health programs. Organizations ought to offer PsyCap workshops that cultivate social courage, persuasive communication, and constructive advocacy within environmental contexts [94]. Training methods can include role-play scenarios where civil servants practice encouraging skeptical colleagues or proposing green initiatives to leadership. Resilience training should prepare staff for potential resistance so they can persist through setbacks and maintain optimistic expectations about advocacy outcomes.

Moreover, given distinctions between PEB-self and PEB-other, managers should apply layered interventions. For junior civil servants, the focus should be on fostering PEB-self to establish sustainable habits and internalize pro-environmental values. Within a supportive green organizational culture, efforts should aim to enhance value internalization, cultivate consistent environmental practices, and strengthen moral identification with sustainability goals [95]. Once these foundations are established, junior staff can gradually be introduced to low-risk PEB-other activities, such as team-based green initiatives, to build confidence and encourage broader engagement. Senior civil servants have the primary responsibility of reducing institutional risk associated with PEB-other. Because PEB-other often entails greater social risk, formal organizational supports are essential [96, 97]. Senior leaders can strengthen incentives and lower perceived risk by instituting green advocacy awards, peer-monitoring systems, and fail-safe policies, thereby legitimizing and institutionalizing environmental efforts [98].

Limitations and future research directions

Although this study explored the formation mechanism of PEB among civil servants from the perspective of psychological resources and developed a two-dimensional scale of localized PEB in the Chinese context, the following shortcomings still exist:

First, the samples for this study mainly come from the civil servant population in Beijing, Zhejiang Province, Guangdong Province, and Sichuan Province. Although the sample of this study can ensure the diversity and representativeness of civil servants in terms of age, gender, education, job grade, and types of government departments, and the sample size met the requirements for statistical analysis and enhances the scientificity and reliability of empirical analysis, considering the heterogeneity between regions may affect the generalizability of research conclusions. Moreover, given the cultural distinctions between East and West, Chinese traditional culture rooted in Confucian philosophy emphasizes family, collective interests, authority, and moral obligation, whereas Western culture, particularly in the United States, places greater emphasis on individualism, democratic governance, and individual rights. As a result, the notion of spirituality is interpreted differently across these cultural contexts, and public service motivation is likewise shaped by specific cultural backgrounds [26, 99]. Future research could employ random sampling to extend the sample to provinces across China, and even to cross-cultural settings, to examine how spirituality influences PEB in diverse cultural contexts.

Second, this study employed a three-wave survey design to reduce the method bias inherent in cross-sectional research and used self-reported questionnaires to provide stronger support for the research conclusions. However, due to the limitations of the research design, it lacks observation of actual behaviors and longitudinal analysis. Future studies could consider adopting experimental methods, longitudinal designs, or field observations to more rigorously examine the causal relationships among variables and to explore the actual effectiveness and sustainability of civil servants’ PEB.

Third, this study examined the influence of combined psychological resources on civil servants’ PEB. While it provides a theoretical basis for explaining such behavior, research on organizational-level factors, such as organizational structure and resource allocation, and societal-level factors, such as public opinion and legal oversight, remains limited. Future research could incorporate multilevel models to explore the interaction mechanisms between government-wide strategies and individual behaviors of civil servants. Besides, with the evolving context of public administration, new influencing factors merit attention, including green behavior in the context of digital governance and the impact of responding to public emergencies, such as pandemics, on the environmental roles of civil servants. Moreover, considering the characteristics of resource investment, future research could further examine the curvilinear relationship between psychological resources and civil servants’ PEB.

Conclusion

Psychological resources play a crucial role in shaping the PEB of civil servants. Drawing on COR theory, this study found that spirituality significantly enhances civil servants’ PEB, a relationship that is mediated by PSM and moderated by PsyCap. As a profound psychological resource, spirituality endows civil servants with a stronger sense of personal values and meaning, which in turn fosters greater engagement in PEB. Furthermore, the positive psychological state associated with high PsyCap facilitates the conversion of motivation into tangible action.

Therefore, public sector organizations should recognize the importance of these psychological attributes. By nurturing multiple psychological resources, they can effectively promote PEB and, consequently, improve the environmental performance of the public sector. This research holds significant implications for both theory and practice, highlighting the utility of COR theory in understanding the behavior of public sector employees and underscoring the need for further investigation in this area.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge the support provided by the participants in this research and the funding.

Abbreviations

- PEB

Pro-environmental behavior

- PSM

Public service motivation

- PsyCap

Psychological capital

- COR

Conservation of resources

- EFA

Exploratory factor analysis

- CFA

Confirmatory factor analysis

- SEM

Structural equation modeling

- CIs

Confidence intervals

- CMV

Common method variance

- ULMC

Unmeasured latent method construct

Biographies

Jianglin Ke

Jianglin Ke is a professor and head of Human Resources Management of Public Sector at School of Government, Beijing Normal University. His research interests include public management, organizational behavior, leadership, public service motivation, workplace spirituality, inclusive climate.

Renbin sun

Renbin Sun is a graduate student who graduated from School of Government, Beijing Normal University. His research interests include human resource management, public administration.

Lidan Liu

Lidan Liu is a PhD student major in Human Resources Management of Public Sector at School of Government, Beijing Normal University. She is interested in public administration, organizational behavior, proactive behavior.

Yufei Zhang

Yufei Zhang is a PhD student major in Human Resources Management of Public Sector at School of Government, Beijing Normal University. She is interested in public administration, inclusive climate in public sector.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the conception and design of the study. Jianglin Ke contributed to conceptualization, supervision, and funding acquisition. Renbin Sun contributed to conceptualization, data curation, and writing of the original draft. Lidan Liu contributed to conceptualization, data curation, writing of the original draft, and review and editing. Yufei Zhang contributed to review and editing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant No. 72174027.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, Liu, upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Our study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. We submitted an application to the Research Ethics Committee of the School of Government at Beijing Normal University. This committee reviewed our protocol and determined that, under Article 32 of the Measures for Ethical Review of Life Sciences and Medical Research Involving Human Beings, formal ethical approval was not required because our study met the criteria for non-interventional research and utilized anonymous data. Researchers obtained informed consent from voluntary participants prior to their involvement in the study for the collection and processing of data.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Fan W, Yan L, Chen B, Ding W, Wang P. Environmental governance effects of local environmental protection expenditure in China. Resour Policy. 2022;77:102760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Azhar A, Yang K. Workplace and non-workplace pro-environmental behaviors: empirical evidence from Florida City governments. Public Adm Rev. 2019;79(3):399–410. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hepburn C. Environmental policy, government, and the market. Oxf Rev Econ Policy. 2010;26(4):734–734. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Azhar A, Yang K. Examining the influence of transformational leadership and green culture on pro-environmental behaviors: empirical evidence from Florida City governments. Rev Public Personnel Adm. 2022;42(4):738–59. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sharpe EJ, Perlaviciute G, Steg L. Pro-environmental behaviour and support for environmental policy as expressions of pro-environmental motivation. J Environ Psychol. 2021;76:101650. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kollmuss A, Agyeman J. Mind the gap: why do people act environmentally and what are the barriers to pro-environmental behavior? Environ Educ Res. 2002;8(3):239–60. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Azhar A. Pro-environmental behavior in public organizations: empirical evidence from Florida City governments. The Florida State University; 2012.

- 8.Gatersleben B, Steg L, Vlek C. Measurement and determinants of environmentally significant consumer behavior. Environ Behav. 2016;34(3):335–62. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Luthans F, Avey JB, Clapp-Smith R, Li W. More evidence on the value of Chinese workers’ psychological capital: A potentially unlimited competitive resource? Int J Hum Resource Manage. 2008;19(5):818–27. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim H. What makes consumers take risks in self–other purchase decision making? The roles of impression management and self-construal. Social Behav Personality: Int J. 2022;50(2):1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wyss AM, Knoch D, Berger S. When and how pro-environmental attitudes turn into behavior: the role of costs, benefits, and self-control. J Environ Psychol. 2022;79:101748. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Niu N, Fan W, Ren M, Li M, Zhong Y. The role of social norms and personal costs on pro-environmental behavior: the mediating role of personal norms. Psychol Res Behav Manage. 2023; 16: 2059–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Hobfoll SE. Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. Am Psychol. 1989;44:513–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dehler GE, Welsh MA. Spirituality and organizational transformation: implications for the new management paradigm. J Managerial Psychol. 1994;9(6):17–26. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Omoyajowo K, Danjin M, Omoyajowo K, et al. Exploring the interplay of environmental conservation within spirituality and multicultural perspective: insights from a cross-sectional study. Environ Dev Sustain. 2024;26(7):16957–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vandenabeele W. Toward a public administration theory of public service motivation: an institutional approach. Public Manage Rev. 2007;9(4):545–56. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hassan S, Ansari N, Rehman A, Moazzam A. Understanding public service motivation, workplace spirituality and employee well-being in the public sector. Int J Ethics Syst. 2022;38(1):147–72. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ardichvili A. Invited reaction: meta-analysis of the impact of psychological capital on employee attitudes, behaviors, and performance. Hum Res Dev Q. 2011;22(2):153–6. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hobfoll SE. Stress, culture, and community: the psychology and physiology of stress. New York: Plenum; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Firoz M, Chaudhary R. The impact of workplace loneliness on employee outcomes: what role does psychological capital play? Personnel Rev. 2022;51(4):1221–47. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jin M, Zhang Y, Wang F, et al. A cross sectional study of the impact of psychological capital on organisational citizenship behaviour among nurses: mediating effect of work engagement. J Nurs Adm Manag. 2022;30(5):1263–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Islam T, Khan MM, Ahmed I, Mahmood K. Promoting in-role and extra-role green behavior through ethical leadership: mediating role of green HRM and moderating role of individual green values. Int J Manpow. 2021;42(6):1102–23. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wierzbicki J, Zawadzka AM. The effects of the activation of money and credit card vs. that of activation of spirituality – Which one prompts pro-social behaviors? Curr Psychol. 2016;35(3):344–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stritch JM, Christensen RK. Looking at a job’s social impact through PSM-tinted lenses: probing the motivation–perception relationship. Public Adm. 2014;92(4):826–42. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ahmad AB, Esteve M, Kempen R. Public service motivation and pro-environmental behaviors: A survey experiment. Int Public Manage J. 2025;1–18. 10.1080/10967494.2025.2489397

- 26.Kaiser FG. A general measure of ecological behavior. J Appl Soc Psychol. 1998;28(5):395–422. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Halpenny EA. Environmental behaviour, place attachment and park visitation: A case study of visitors to point Pelee National park. Waterloo: University of Waterloo; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Su L, Huang S, Pearce J. Toward a model of destination resident–environment relationship: the case of Gulangyu, China. J Travel Tourism Mark. 2019;36(4):469–83. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bissing-Olson MJ, Iyer A, Fielding KS, Zacher H. Relationships between daily affect and pro-environmental behavior at work: the moderating role of pro-environmental attitude. J Organizational Behav. 2013;34(2):156–75. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Peng YC. Environmental behavior of the public and its cultivation. J Soc Issues. 2011;11:47–52. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Behn O, Wichmann J, Leyer M, Schilling A. Spillover effects in environmental behaviors: a scoping review about its antecedents, behaviors, and consequences. Curr Psychol. 2025;44(5):3665–89. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Berger IE, Corbin RM. Perceived consumer effectiveness and faith in others as moderators of environmentally responsible behaviors. J Public Policy Mark. 1992;11(2):79–89. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Houston D, Cartwright K. Spirituality and public service. Public Adm Rev. 2007;67(1):88–102. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aquino K, Reed AI, I. The self importance of moral identity. J Personal Soc Psychol. 2002;83(6):1423–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schwartz SH. Universals in the content and structure of values: theoretical advances and empirical tests in 20 countries. Advances in experimental social psychology. Acad Press. 1992;25:1–65. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chaudhary R, Singh A, Srivastava S. Does workplace spirituality promote ethical voice: examining the mediating effect of psychological ownership and moderating influence of moral identity. J Bus Ethics. 2024;195(3):779–97. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ongaro E, Tantardini M. Religion, spirituality, faith and public administration: A literature review and outlook. Public Policy Adm. 2023;39(4):531–55. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moss B. Spirituality and social care: contributing to personal and community well-being. Br J Social Work. 2003;33(4):578–80. [Google Scholar]

- 39.De Klerk JJ, Boshoff AB, Van Wyk R. Spirituality in practice: relationships between meaning in life, commitment and motivation. J Manage Spiritual Relig. 2006;3(4):319–47. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wei XN, Yu F, Peng KP, Zhong N. Psychological richness increases behavioral intention to protect the environment. Acta Physiol Sinica. 2023;55(8):1330–43. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang B, Yang L, Cheng X, Chen F. How does employee green behavior impact employee well-being? An empirical analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(4):1669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wen B, Tang SY, Lo CWH. Changing levels of job satisfaction among local environmental enforcement officials in China. China Q. 2020;241:112–43. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jean GS, Edward WS. Building spiritual capabilities to sustain sustainability-based competitive advantages. J Manage Spiritual Relig. 2014;11(2):143–58. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Iqbal J, Aukhoon MA, Aman-Ullah A et al. Workplace spirituality and pro-environmental behavior: psychological green climate and ethical leadership. Manag Decis, 2025. 10.1108/MD-09-2024-1998

- 45.Perry JL, Hondeghem A. Motivation in public management: the call of public service. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hobfoll S. Social and psychological resources and adaptation. Rev Gen Psychol. 2002;6(4):307–24. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hansla A. Value orientation, awareness of consequences, and environmental concern. Department of Psychology; Psykologiska institutionen; 2011.

- 48.Benefiel M, Fry LW, Geigle D. Spirituality and religion in the workplace: History, theory, and research. Psychol Relig Spiritual. 2014;6(3):175–87. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hassan S, Ansari N, Rehman A. An exploratory study of workplace spirituality and employee well-being affecting public service motivation: an institutional perspective. Qualitative Res J. 2021;22(2):209–35. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hassan S, Ansari N, Rehman A. Public service motivation, workplace spirituality and employee well-being: a holistic approach. J Economic Administrative Sci. 2023;39(4):1027–43. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cuevas Gutierrez C, Gonzalez-Bustamante B, Calderon-Orellana M. Barria Traverso, D. Motivation for public service in Chilean civil servants. Revista Del CLAD Reforma Y Democracia. 2021;81:105–38. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Qiao H, Chen S, Dong X, Dong K. Has china’s coal consumption actually reached its peak? National and regional analysis considering cross-sectional dependence and heterogeneity. Energy Econ. 2019;84:104509. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Peng X, Lee S, Lu Z. Employees’ perceived job performance, organizational identification, and pro-environmental behaviors in the hotel industry. Int J Hospitality Manage. 2020;90:102632. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhang Y, Dong Y, Wang R, Jiang J. Can organizations shape eco-friendly employees? Organizational support improves pro-environmental behaviors at work. J Environ Psychol. 2024;93:102200. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Aydin Sünbül Z, Aslan Gördesli M. Psychological capital and job satisfaction in public-school teachers: the mediating role of prosocial behaviours. J Educ Teach. 2021;47(2):147–62. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zahra M, Kee DMH, Teh SS, et al. Psychological capital impact on extra role behaviour via work engagement: evidence from the Pakistani banking sector. Int J Bank Finance. 2022;17(1):27–52. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Otto S, Pensini P, Zabel S, Diaz-Siefer P, Burnham E, Navarro-Villarroel C, Neaman A. The prosocial origin of sustainable behavior: A case study in the ecological domain. Glob Environ Change. 2021;69:102312. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Koval VV, Havrychenko D, Filipishyna L, Udovychenko I, Prystupa L, Mikhno I. Behavioral economic model of environmental conservation in human resource management. Intellect Econ. 2023;17(2):435–56. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dilulio JD. Principled agents: the cultural bases of behavior in a federal government bureaucracy. J Public Adm Res Theor. 1994;4(3):277–318. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Perry JL, Wise LR. The motivational bases of public service. Public Adm Rev. 1990;50(3):367–73. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Steg L. Values, norms, and intrinsic motivation to act proenvironmentally. Annu Rev Environ Resour. 2016;41(1):277–92. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yang Y, Wen B, Song Y. A moderated mediation model on the relationship among public service motivation (PSM), self-efficacy, job satisfaction, and readiness for change. Rev Public Personnel Adm. 2024.Advance online publication. 10.1177/0734371X241281750.

- 63.Mangos PM, Steele-Johnson D. The role of subjective task complexity in goal orientation, self-efficacy, and performance relations. Hum Perform. 2001;14(2):169–85. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Khliefat A, Chen H, Ayoun B, et al. The impact of the challenge and hindrance stress on hotel employees interpersonal citizenship behaviors: psychological capital as a moderator. Int J Hospitality Manage. 2021;94:102886. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bohns VK, editor. (Mis) Understanding our influence over others: A review of the underestimation-of-compliance effect. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2016; 25(2): 119–123.

- 66.Martínez-Íñigo D, Poerio GL, Totterdell P. The association between controlled interpersonal affect regulation and resource depletion. Appl Psychology: Health Well-Being. 2013;5(2):248–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Feng X, Tao K, Chen S, Tian H, Xing Z. Why do challenge stressors support and then desert us? The moderating and mediating role of psychological capital. Social Behav Personality: Int J. 2022;50(7):1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Xi Y, Xu Y, Wang Y. Too-much-of-a-good-thing effect of external resource investment—A study on the moderating effect of psychological capital on the contribution of social support to work engagement. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(2):437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gan L, Yang X, Chen L, Lev B, Lv Y. Optimization path of economy-society-ecology system orienting industrial structure adjustment: evidence from Sichuan Province in China. Ecol Ind. 2022;144:109479. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Huang L, Zhang Y, Xu X. Spatial-temporal pattern and influencing factors of ecological efficiency in Zhejiang—Based on super-SBM method. Environ Model Assess. 2023;28(2):227–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wang C, Wang F, Zhang X, Deng H. Analysis of influence mechanism of energy-related carbon emissions in guangdong: evidence from regional China based on the input-output and structural decomposition analysis. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2017;24:25190–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zhang H, Wang S, Hao J, Wang X, Wang S, Chai F, Li M. Air pollution and control action in Beijing. J Clean Prod. 2016;112:1519–27. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wu H, Li Y, Hao Y, Ren S, Zhang P. Environmental decentralization, local government competition, and regional green development: evidence from China. Sci Total Environ. 2020;708:135085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Maloney MP, Ward MP, Ecology. Let’s hear from the people: an objective scale for the measurement of ecological attitudes and knowledge. Am Psychol. 1973;28(7):583–6. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Otto S, Kaiser FG, Arnold O. The critical challenge of climate change for psychology. Eur Psychol. 2014;19(2):96–106. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Howden JW. Development and psychometric characteristics of the spirituality assessment scale. Texas Woman’s University; 1992.

- 77.Anderson SE, Burchell JM. The effects of spirituality and moral intensity on ethical business decisions: A cross-sectional study. J Bus Ethics. 2021;168(1):137–49. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Peng H. Infusing positive psychology with spirituality in a strength-based group career counseling to evaluate college students’ state anxiety. Int J Psychol Stud. 2015;7(1):75–84. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Coursey DH, Pandey SK. Public service motivation measurement: testing an abridged version of perry’s proposed scale. Adm Soc. 2007;39(5):547–68. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hayes AF. Beyond Baron and kenny: statistical mediation analysis in the new millennium. Communication Monogr. 2009;76(4):408–20. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Lee JY, Podsakoff NP. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J Appl Psychol. 2003;88(5):879–903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Richardson HA, Simmering MJ, Sturman MC. A Tale of three perspectives: examining post hoc statistical techniques for detection and correction of common method variance. Organizational Res Methods. 2009;12(4):762–800. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Aiken LS, West SG, Reno RR. Multiple regression: testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Rezapouraghdam H, Alipour H, Darvishmotevali M. Employee workplace spirituality and pro-environmental behavior in the hotel industry. J Sustainable Tourism. 2018;26(5):740–58. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ke J, Zhang J, Zheng L. Inclusive leadership, workplace spirituality, and job performance in the public sector: A multi-level double-moderated mediation model of leader-member exchange and perceived dissimilarity. Public Perform Manage Rev. 2022;45(3):672–705. [Google Scholar]