Abstract

Background

Cancer-associated signaling pathways, particularly the ALK/LTK receptor tyrosine kinases and their ligand ALKAL2, have recently been implicated in chronic inflammation and myocardial remodeling. However, the relationship between ALKAL2 and coronary artery disease (CAD) pathogenesis in type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) remains undefined.

Methods

From January 2019 to December 2020, patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) undergoing coronary angiography were consecutively enrolled at Ruijin Hospital. Plasma ALKAL2 levels were measured using an ELISA assay. The association between ALKAL2 and CAD severity was assessed by Spearman correlation analysis. Logistic regression models were used to measure the association between ALKAL2 and CAD risk.

Results

275 T2DM patients with CAD and 275 age- and sex-matched T2DM patients without CAD were included in the final analysis. Plasma ALKAL2 levels were increased in T2DM patients with CAD (0.25 [0.21, 0.37] ng/mL, median [IQR] vs. 0.18 [0.14, 0.24]ng/mL) (p < 0.001) and were positively associated with CAD severity (Spearman rho = 0.53, p < 0.001). Multivariate analysis revealed that plasma ALKAL2 levels were independently associated with the incidence of CAD after adjusting for LDL-C, hsCRP, and other traditional risk factors (OR, 2.24 [95% CI, 1.79–2.85]; p < 0.001).

Conclusions

Elevated plasma ALKAL2 levels are an independent risk factor for T2DM CAD and are associated with the severity of CAD.

Keywords: ALKAL2, Type 2 diabetes, Coronary artery disease

Introduction

The global prevalence of T2DM is rising, and its macrovascular complications, especially CAD, heart failure, stroke, and peripheral artery disease (PAD), have become the most common and fatal comorbidities [1–3]. For T2DM patients, preventing ischemic events and halting atherosclerosis (AS) progression are crucial for improving quality of life and survival [4]. Although the widespread use of novel glucose-lowering agents, lipid-modifying therapies, and percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) has reduced the incidence of cardiovascular disease (CVD) in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) [4–6], their risk remains significantly higher than that of the general population [5]. Thus, preventing CAD and reducing mortality in diabetic patients remain significant clinical challenges.

Recent studies have demonstrated that gene regulatory networks, typically associated with cancer pathogenesis—such as oncogenic signaling pathways, epigenetic regulators, and cell cycle control systems—also play crucial roles in cardiovascular conditions, including atherosclerosis, myocardial fibrosis, and heart failure [6–10]. These networks may contribute to cardiovascular pathogenesis by modulating vascular smooth muscle cell (VSMC) phenotypic switching, endothelial dysfunction, and chronic inflammation through various mechanisms [11, 12]. Notably, the oncogenes anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) and leukocyte tyrosine kinase (LTK), which drive malignancies of anaplastic large-cell lymphoma or non-small cell lung cancer via pro-proliferative and anti-apoptotic pathways [13, 14], have recently been shown to regulate inflammatory responses and pathological remodeling in the cardiovascular system [15–21]. As key members of the receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) family, ALK and LTK share the same physiological ligand, ALKAL2 [22]. Recent studies report that cardiac-specific LTK activation in transgenic mice promotes cardiomyocyte proliferation and cardiac hypertrophy [23]. However, the roles of LTK and ALK in atherosclerotic plaque formation remain unclear, and whether ALKAL2 drives plaque progression in diabetes awaits elucidation.

To address this, the GADA study (Glycation of apoA-I and Diabetic Atherogenesis Cohort Study, NCT05659043) identified elevated plasma ALKAL2 as a novel risk factor for CAD progression by comparing ALKAL2 levels in diabetic patients with and without CAD.

Methods

Study population

This study was part of the GaDA study (Glycation of ApoA-I and Diabetic Atherosclerosis). A total of 1,133 patients enrolled between 2019 and 2020 were included in the present analysis from the GADA cohort, comprising individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) with CAD (n = 816) and those with T2DM without CAD (n = 317). Baseline demographic characteristics, traditional cardiovascular risk factors, and medication usage were systematically recorded. The inclusion criteria were based on established diagnostic standards for diabetes, including a glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) level of ≥ 6.5%, a confirmed fasting plasma glucose level of ≥ 7.0 mmol/L, a 2-hour plasma glucose level of ≥ 11.1 mmol/L following an oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT), or current use of antidiabetic medications. All patients underwent coronary angiography due to clinical suspicion of CAD or coronary computed tomographic angiography (CCTA) for suspected CAD or other relevant indications. The diagnoses of hypertension and dyslipidemia were defined according to the criteria of the Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (JNC 7) [24] and the Adult Treatment Panel III (ATP III) guidelines [25], respectively. To minimize potential confounding associated with systemic inflammation, lipid metabolism, or organ dysfunction, patients with the following conditions were excluded: acute coronary syndrome (n = 160), familial hypercholesterolemia (n = 16), malignancy (n = 16), end-stage renal disease requiring dialysis (n = 20), autoimmune diseases (n = 12), and rheumatic heart disease (n = 16). Ultimately, 275 T2DM patients with CAD and 275 age- and sex-matched T2DM patients without CAD were included in this study (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flow chart

Coronary angiography and analysis

All patients underwent coronary angiography to assess the severity of CAD. Two experienced cardiologists independently interpreted the angiography results. In cases of disagreement, a third expert was consulted to provide arbitration. The findings from the coronary angiography included the number of lesions and the degree of stenosis, defined as stenosis ≥ 50%, in the main coronary arteries (left main trunk, left anterior descending artery, left circumflex artery, and right coronary artery). The Gemini score (GS) [26] was used to quantify the severity of CAD. The Gemini scoring system is a widely recognized method for comprehensively evaluating the complexity and severity of coronary artery disease CAD. It calculates the score based on three primary parameters: the severity score of the lesion, the regional multiplication factor, and the adjustment factor for collateral circulation. The severity of coronary artery lesions was categorized into three levels: mild, moderate, and severe. This classification, based on the Gensini score, was utilized for further analysis.

Biochemical evaluation

Peripheral venous blood samples were collected on the day of angiography following an overnight fast. The analysis included the measurement of plasma glucose, blood urea nitrogen, uric acid, and creatinine levels, in addition to a lipid profile comprising triglycerides, total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, and high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, all conducted using standard laboratory techniques with the HITACHI 912 analyzer (Roche Diagnostics, Germany). The glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) concentration was assessed via ion-exchange high-performance liquid chromatography, utilizing the Bio-Rad Variant Hemoglobin Assay System (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA) [27]. The estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was calculated using the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration Eqs. (28, 29). Furthermore, plasma levels of high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP) and plasma ALKAL2 protein were evaluated using the ELISA method (Biocheck Laboratories, Toledo, OH, USA; Shanghai Enzyme-linked Biotechnology Co., Ltd) [30].

Statistical analysis

Normality of continuous variables was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test, with visual assessment performed using histograms and Q-Q plots. Variables that conformed to a normal distribution were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD), and between-group comparisons were performed using the independent-samples t-test. Non-normally distributed variables were expressed as median (IQR) and compared using non-parametric tests (the Mann-Whitney U test for two-group comparisons or the Kruskal-Wallis test for multi-group comparisons). Because hsCRP exhibited a significantly skewed distribution, it was included in the analysis after undergoing a natural logarithmic transformation. Categorical variables were presented as frequencies and percentages. Since the expected frequency for each cell was greater than 5, comparisons were made using the chi-square test. The severity of coronary artery disease was quantitatively assessed using the Gensini score (GS). The Shapiro-Wilk test and graphical analysis indicated that the GS was non-normally distributed. The subjects were divided into three groups based on tertile levels: T1 (mild lesion, GS 0–19), T2 (moderate lesion, GS 20–42), and T3 (severe lesion, GS 43–156). Differences among the three groups were compared overall using the Kruskal-Wallis rank sum test. If the overall differences were statistically significant, further pairwise comparisons were performed using the Bonferroni correction. To investigate the independent association between ALKAL2 levels and the development of coronary artery disease (CAD), a multivariate logistic regression model was constructed, incorporating traditional risk factors (age, sex, BMI, smoking status, LDL-C, eGFR, hsCRP, and glycated hemoglobin). ALKAL2 levels were included in the model as a continuous variable and analyzed by tertile to assess their independent predictive value. Model goodness of fit was evaluated using the Hosmer-Lemeshow test and Brier score. Model discrimination was assessed using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves and area under the curve (AUC), and the optimal cutoff value was determined based on the Youden index. The AUCs of different models were compared using the DeLong method. Net reclassification improvement (NRI) and integrated discrimination improvement (IDI) were further calculated to quantify the benefit of ALKAL2 incorporation on risk stratification. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) and R 4.0.2 software. All tests were two-sided, and p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Baseline characteristics of the study population

A total of 550 subjects were enrolled in this study. Despite comparable distributions of age and gender between groups, individuals in the T2DM-CAD group exhibited a higher prevalence of smoking, hypertension, and dyslipidemia compared with those in the non-CAD group. Furthermore, serum hsCRP levels were modestly elevated in the T2DM-CAD cohort, suggesting the presence of a chronic inflammatory state. Notably, levels of Lp(a), blood urea nitrogen (BUN), and serum creatinine (SCr) were significantly higher in the CAD group, reflecting dyslipidemia and impaired renal function. In addition, patients with CAD had markedly elevated levels of HbA1c and fasting blood glucose (FBG), indicating suboptimal glycemic control (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics in T2DM patients with or without CAD

| Variables | T2DM nonCAD (n = 275) | TT2DM CAD (n = 275) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 65.56 ± 10.73 | 66.67 ± 9.05 | 0.1891 |

| Male, n (%) | 180 (65.45) | 180 (65.45) | 1.003 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 26.98 ± 3.00 | 27.66 ± 1.65 | 0.0011 |

| Systolic Blood Pressure, mm Hg | 137.36 ± 20.98 | 135.50 ± 20.30 | 0.2921 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 75.07 ± 11.96 | 74.31 ± 10.84 | 0.4371 |

| Dyslipidemia History, n (%) | 57 (20.73) | 80 (29.09) | 0.0233 |

| Hypertension History, n (%) | 145 (52.73) | 189 (68.73) | <.0013 |

| Smoke, n (%) | 68 (24.73) | 96 (34.91) | <.0093 |

| EF, % | 61.04 ± 15.29 | 59.97 ± 14.58 | 0.4051 |

| BUN, mg/dL | 5.80 (4.90, 6.80) | 6.60 (5.30, 8.10) | <.0012 |

| SCr, mg/dL | 81.00 (66.00, 92.00) | 82.00 (70.50, 98.00) | 0.0042 |

| UA, mg/dL | 328.00 (271.00, 380.00) | 333.00 (281.50, 399.00) | 0.1952 |

| eGFR, mL/min per 1.73 m2 | 80.31 (69.45, 93.04) | 79.77 (61.74, 92.12) | 0.0512 |

| TG, mmol/L | 1.36 (1.02, 1.98) | 1.35 (0.99, 1.97) | 0.8052 |

| TC, mmol/L | 3.67 (3.04, 4.55) | 4.15 (2.25, 4.91) | 0.2572 |

| HDL-C, mmol/L | 1.05 (0.84, 1.26) | 1.03 (0.89, 1.28) | 0.2972 |

| LDL-C, mmol/L | 2.00 (1.50, 2.71) | 2.09 (1.63, 3.12) | 0.0152 |

| Lipoprotein(a), mmol/L | 0.12 (0.07, 0.25) | 0.16 (0.08, 0.36) | 0.0082 |

| FBG, mmol/L | 5.72 (4.91, 7.27) | 6.41 (5.23, 7.84) | 0.0022 |

| HbA1c, % | 6.40 (5.60, 7.15) | 7.20 (6.00, 7.84) | <.0012 |

| hsCRP, mg/L | 0.59 (0.28, 1.72) | 1.97 (0.60, 4.64) | <.0012 |

| Medication, n (%) | |||

| Statins | 192 (69.82) | 211 (76.73) | 0.0673 |

| Metformin | 101 (36.73) | 121 (44.00) | 0.0823 |

| Sulfonylureas | 99 (36.00) | 115 (41.82) | 0.1623 |

| Insulin therapy | 59 (21.45) | 106 (38.55) | <.0013 |

| ALKAL2, ng/mL | 0.18 (0.14, 0.24) | 0.25 (0.21, 0.37) | <.0012 |

Normal distribution data were expressed as mean ± SD and compared between two groups using the independent samples t-test¹. Skewed distribution data were expressed as median (25th–75th percentile) and compared using the Mann–Whitney U test². Categorical data were expressed as n (%) and compared using the chi-square test³. Differences were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05. T2DM: Type 2 diabetes mellitus; CAD-T2DM: Coronary Artery Disease with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus; EF: Ejection Fraction; BUN: Blood Urea Nitrogen; SCr: Plasma Creatinine; UA: Uric Acid; eGFR: estimated glomerular filtration rate; TG: Triglycerides; TC: Total Cholesterol; HDL: High-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol; LDL: Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol; FBG: Fasting Blood Glucose; HbA1c: Hemoglobin A1c; HsCRP: High-Sensitivity C-Reactive Protein

1: normally distributed

2: non-normally distributed

3: Chi-squared test

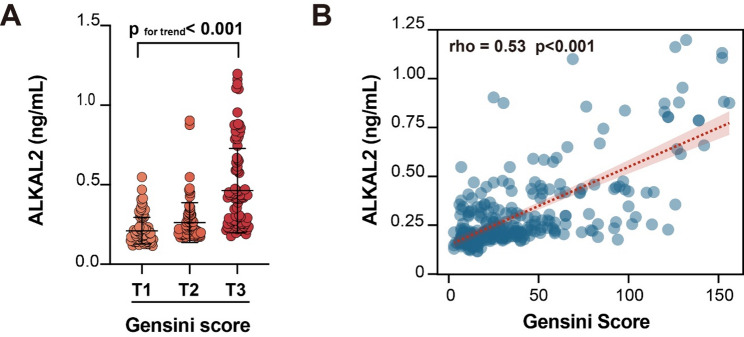

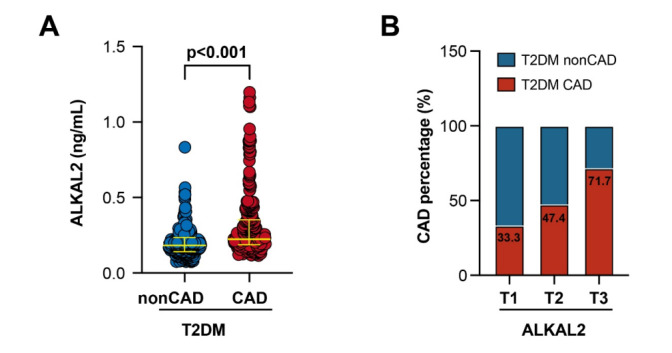

Association between coronary artery atherosclerosis severity and plasma ALKAL2 levels

Compared with the simple diabetes group, the plasma ALKAL2 levels were higher in the diabetes combined with coronary artery disease group (0.25 [0.21, 0.37] ng/mL, median [IQR] vs. 0.18 [0.14, 0.24] ng/mL) (p < 0.001) (Fig. 2A); The incidence of CAD increased progressively from the lowest to the highest tertile of ALKAL2 (Fig. 2B). The distribution of plasma ALKAL2 levels was observed after grouping by Gensini score. The results showed a positive correlation between plasma ALKAL2 levels and the Gensini score (p < 0.001) (Fig. 3A), which was consistent with the Spearman correlation test result (Spearman rho = 0.53, p < 0.001) (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 2.

Elevated plasma ALKAL2 levels in T2DM with CAD A Comparison of plasma ALKAL2 levels between T2DM patients with and without CAD. B Trends in the prevalence of CAD across increasing tertiles of plasma ALKAL2 levels

Fig. 3.

Positive correlation between plasma ALKAL2 levels and CAD severity A Distribution of plasma ALKAL2 levels stratified by tertiles of the Gensini score. B Spearman correlation analysis between plasma ALKAL2 levels and Gensini score

Multivariable logistic regression analysis

A logistic regression model was established, demonstrating a strong association between plasma ALKAL2 levels and the presence of coronary artery disease (CAD). In multivariate analyses, after adjustment for conventional cardiovascular risk factors (including age, sex, body mass index, hypertension, glycated hemoglobin [HbA1c], smoking status, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol [LDL-C], estimated glomerular filtration rate [eGFR], and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein [hsCRP]), ALKAL2 remained an independent risk factor for CAD in patients with type 2 diabetes (T2DM) (OR: 2.24; 95% CI: 1.79–2.85; p < 0.001) (Table 2). Stratified analyses further indicated a dose–response relationship: compared with the lowest tertile (T1), patients in the middle (T2) and highest tertiles (T3) exhibited significantly elevated risks of CAD, with odds ratios of 5.65 (95% CI: 3.39–9.43) and 7.89 (95% CI: 4.68–13.30), respectively (Table 3). Model calibration assessed by the Hosmer–Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test showed no significant lack of fit (p > 0.05). The Brier score of the ALKAL2-augmented model (0.185) was lower than that of the baseline model (0.208), reflecting reduced prediction error and enhanced model performance (Table 4). Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis confirmed the discriminatory capacity of ALKAL2 for CAD (AUC: 0.77; 95% CI: 0.73–0.81; p < 0.001; sensitivity: 86.18%; specificity: 56.00%; optimal threshold: 0.19 ng/mL) (Fig. 4A). Integration of ALKAL2 into the baseline clinical model significantly improved diagnostic accuracy (AUC: 0.69 [95% CI: 0.65–0.74] vs. 0.79 [95% CI: 0.75–0.82]; p < 0.001) (Fig. 4B), while also yielding significant improvements in reclassification, as reflected by the net reclassification index (NRI: 0.61; 95% CI: 0.45–0.76; p < 0.001) and integrated discrimination improvement (IDI: 0.12; 95% CI: 0.09–0.15; p < 0.001).

Table 2.

Multivariable logistic regression analyses results

| Variables | OR (95% CI) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Male | 1.16 (0.78–1.73) | 0.471 |

| Age | 1.01 (0.99–1.03) | 0.300 | |

| Body mass index | 1.14 (1.05–1.23) | 0.002 | |

| Hypertension | 1.72 (1.18–2.51) | 0.005 | |

| HbA1c | 1.17 (1.04–1.33) | 0.013 | |

| Smoke | 1.76 (1.16–2.67) | 0.008 | |

| LDL-C | 1.34 (1.12–1.61) | 0.002 | |

| eGFR | 0.99 (0.98–1.00) | 0.139 | |

| Log-transferred hsCRP | 1.31 (1.19–1.44) | < 0.001 | |

| Model 2 | Male | 1.42 (0.92–2.22) | 0.116 |

| Age | 1.01 (0.99–1.03) | 0.422 | |

| Body mass index | 1.09 (1.00–1.19) | 0.044 | |

| Hypertension | 1.41 (0.94–2.13) | 0.100 | |

| HbA1c | 1.20 (1.05–1.38) | 0.009 | |

| Smoke | 1.31 (0.83–2.07) | 0.252 | |

| LDL-C | 1.17 (0.95–1.45) | 0.137 | |

| eGFR | 0.99 (0.98–1.00) | 0.214 | |

| Log-transferred hsCRP | 1.29 (1.17–1.42) | < 0.001 | |

| ALKAL2(per 0.1) | 2.24 (1.79–2.85) | < 0.001 |

Model 1: adjusted for Age, Gender, BMI, Hypertension, HbA1c, Smoke, LDL-C, eGFR, and log-transformed hsCRP. Model 2: Model 1 plus ALKAL2 (continuous per 0.1 unit). P-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. OR: odds ratio; CI: confidence interval

Table 3.

Association of ALKAL2 tertiles with risk of coronary artery disease in patients with type 2 diabetes

| ALKAL2 tertiles | OR (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|

| T1 | 1.00 (reference) | |

| T2 | 5.65 (3.39–9.43) | < 0.001 |

| T3 | 7.89 (4.68–13.30) | < 0.001 |

Logistic regression analysis was performed with adjustment for Age, Gender, BMI, Hypertension, HbA1c, Smoke, LDL-C, eGFR, and log-transformed hsCRP. P-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. OR: odds ratio; CI = confidence interval

Table 4.

Multivariable logistic regression model performance

| Model | Brier Score | Hosmer-Lemeshow χ² | Hosmer-Lemeshow p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | 0.208 | 13.09 | 0.109 |

| Model 2 | 0.185 | 12.86 | 0.117 |

The Brier score reflects overall prediction error, with lower values indicating better performance. Hosmer–Lemeshow χ² and p-values assess model calibration, with p-values greater than 0.05 indicating an adequate fit

Fig. 4.

ROC curve analyses evaluating the predictive performance of plasma ALKAL2 for CAD in T2MD patients. A A univariate logistic regression model incorporating plasma ALKAL2 as the sole predictor was constructed to assess its discriminative ability for CAD. B Plasma ALKAL2 was further incorporated into a multivariate logistic regression model that included conventional cardiovascular risk factors (e.g., age, sex, BMI, smoking status, hypertension, LDL-C, eGFR, hsCRP, and HbA1c). The ROC curve derived from this model was used to evaluate the incremental predictive value of plasma ALKAL2 after adjusting for potential confounders

Multivariable stratified logistic regression was conducted to assess the impact of ALKAL2 exposure across various populations. Subgroup analysis revealed that factors like gender, age, BMI, eGFR, HbA1c, hypertension, Dyslipidemia, and smoking significantly heightened the effect of ALKAL2 in CAD’s high-risk subgroup (Fig. 5). This suggests a correlation between plasma ALKAL2 levels and disease severity. ALKAL2 shows a significant association with CAD, and clinical characteristics such as obesity, hypertension, and smoking may worsen this association. Therefore, it is essential to consider these covariates together when predicting CAD risk.

Fig. 5.

Subgroup analyses evaluating the association between plasma ALKAL2 levels and CAD across various high-risk populations. Stratified analyses were performed according to sex, age, BMI, estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), HbA1c level, hypertension status, dyslipidemia, and smoking status to assess the consistency of ALKAL2’s predictive value across clinically relevant subgroups (adjusted for Age, Gender, BMI, Hypertension, HbA1c, Smoke, LDL-C, eGFR, and log-transformed hsCRP)

Discussion

This study reveals for the first time that plasma ALKAL2 protein levels in diabetic patients show a significant positive correlation with the severity of coronary atherosclerosis. After adjusting for confounding factors, including age, sex, BMI, smoking history, Total/HDL-C ratio, hypertension, HbA1c, eGFR, and hsCRP, high plasma ALKAL2 levels remained an independent risk factor for CAD. This finding suggests that ALKAL2 may serve as a novel risk biomarker and potential pathogenic factor for diabetes-associated CAD.

The RTK family comprises approximately 20 subfamilies and 58 receptors, characterized by an extracellular ligand-binding domain, a transmembrane helix, and an intracellular kinase domain [31–33]. Beyond classical members like EGFR, VEGFR, PDGFR, and FGFR, which participate in cardiovascular diseases by regulating vascular inflammation, fibrosis, and angiogenesis [34, 35]. The ALKA/LTK subfamily (class XVI of RTK) has recently been implicated in cardiovascular homeostasis. For instance, tissue-specific LTK activation mechanisms exist in the heart, and their dysregulation can lead to myocardial hypertrophy, cardiomyocyte degeneration, and genetic reprogramming [23]. Additionally, ALK expression is significantly upregulated in the neurovascular unit following cerebral ischemia, where it induces oxidative stress and vascular inflammation by upregulating ALOX15, thereby damaging the endothelial barrier [36].

Under physiological conditions and in most diseases, including cancer, inflammation, and autoimmune disorders, ALK/LTK activity is primarily regulated by its high-affinity endogenous ligand ALKAL2 (although ligand-independent constitutive activation via fusion mutations occurs in some cancers) [37, 38]. ALKAL2 binds to ALK or LTK receptors as a homodimer, inducing receptor dimerization and triggering trans-autophosphorylation of the intracellular tyrosine kinase domain. This activates downstream key signaling pathways, such as RAS/MAPK, PI3K/AKT, and JAK/STAT (32–34), which regulate cell proliferation, survival, differentiation, and function. Notably, ALKAL2 exhibits a stronger activation preference for LTK [39].

This study found that plasma ALKAL2 levels were significantly higher in diabetic CAD patients than in diabetic non-CAD patients, and ROC curve analysis demonstrated its good predictive accuracy for CAD occurrence. We propose that elevated plasma ALKAL2 may exacerbate cardiovascular complications in diabetic patients through two potential mechanisms. (1) Metabolic-Sympathetic-Vascular Pathway: ALKAL2 acts on AgRP neurons in the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus (PVN) axis, modulating sympathetic tone and adipose distribution [40]. ALKAL2-knockout mice exhibit a lean phenotype with enhanced selective lipolysis [40], highlighting its role in metabolic regulation. Aberrant ALKAL2 levels may disrupt metabolic homeostasis and amplify sympathetic activity, thereby promoting vascular pathology. (2) Pain-Neurogenic Cardiovascular Coupling Pathway: As an algogenic neuromodulator, ALKAL2 activates LTK receptors in dorsal root ganglia (DRG), thereby enhancing Nav1.7 sodium channel activity and CGRP release to mediate chronic pain signaling [41]. Chronic pain itself significantly increases cardiovascular risk by persistently activating the sympathetic-adrenal-medullary (SAM) axis and promoting systemic inflammation [42]. Thus, ALKAL2-driven chronic pain may serve as a critical bridge linking neurosensory dysfunction to cardiovascular injury.

Furthermore, fusion mutations in the ALK and LTK genes are common, ligand-independent oncogenic drivers in multiple cancers [39, 43, 44]. Although clinically used ALK/LTK inhibitors (such as lorlatinib and ensartinib) are effective, they often cause significant side effects, including cardiovascular toxicity [45, 46]. Consequently, researchers are exploring engineered ALKAL2 itself as a strategy to target and inactivate oncogenic ALK/LTK fusion proteins specifically. However, this study reveals that elevated plasma ALKAL2 may itself be an independent cardiovascular risk factor, potentially aggravating vascular injury through metabolic dysregulation, sympathetic activation, and chronic pain. Therefore, when developing engineered ALKAL2 or its analogs as targeted therapeutics, the potential anticancer benefits must be judiciously weighed against possible cardiovascular risks, mandating rigorous safety assessment.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, as a single-center, cross-sectional study, it precludes causal inference. Further prospective studies are warranted to validate the causal relationship between ALKAL2 and coronary artery disease (CAD) in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). Second, although the study population—a consecutive cohort of T2DM patients undergoing coronary angiography—aligns with the objective of investigating high-risk individuals, potential selection bias may limit the generalizability of the results. Third, CAD severity was assessed solely using the Gensini score. The lack of advanced intravascular imaging techniques, such as optical coherence tomography (OCT) or intravascular ultrasound (IVUS), may have led to an underestimation of plaque complexity. Fourth, although conventional cardiovascular risk factors were adjusted for, residual confounding from unmeasured variables—such as diabetes duration, microvascular complications, and chronic low-grade inflammation—cannot be excluded. Fifth, the limited specificity of ALKAL2 as a standalone biomarker suggests that its clinical utility may be greater within a multi-marker panel, necessitating further validation. Sixth, direct mechanistic evidence regarding the role of ALKAL2 in cardiovascular disease remains insufficient. Current functional studies have predominantly focused on oncological contexts, and further investigation is needed to elucidate its pathway in atherosclerosis development and progression. Finally, as a single-center study with a relatively homogeneous population, potential racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic differences were not accounted for. External validation in larger, multi-center, and multi-ethnic cohorts is therefore needed.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that elevated plasma ALKAL2 levels are independently associated with CAD in T2DM patients and correlate with disease severity.

Author contributions

L.L., Y.D., W.F., F.D., and Q.J. contributed to the study conception and design, F.L. and J.L. prepared material, S.C., X.W., and J.C. collected data, Y.M. and S.C. analyzed data, Y.M. and Y.D. wrote the first draft of the manuscript, and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by a grant from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82470433 and 82070358) and Ruijin Hospital Nursing Specialized Fund [RJKH(Y)−2025-018].

Data availability

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Yipaerguli Maimaiti, Minhui Wang and Shuai Chen contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Yang Dai, Email: yutongwushe@163.com.

Lin Lu, Email: rjlulin1965@163.com.

References

- 1.Arnold SV, Bhatt DL, Barsness GW, Beatty AL, Deedwania PC, Inzucchi SE, et al. Clinical management of stable coronary artery disease in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A scientific statement from the American heart association. Circulation. 2020;141(19):e779–806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Danaei G, Lawes CM, Vander Hoorn S, Murray CJ, Ezzati M. Global and regional mortality from ischaemic heart disease and stroke attributable to higher-than-optimum blood glucose concentration: comparative risk assessment. Lancet. 2006;368(9548):1651–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wong ND, Budoff MJ, Ferdinand K, Graham IM, Michos ED, Reddy T, et al. Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk assessment: an American society for preventive cardiology clinical practice statement. Am J Prev Cardiol. 2022;10:100335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.10. Cardiovascular disease and risk management: standards of medical care in Diabetes-2019. Diabetes Care. 2019;42(Suppl 1):S103–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Avdic T, Carlsen HK, Isaksson R, Gudbjörnsdottir S, Mandalenakis Z, Franzén S, et al. Risk factors for and risk of peripheral artery disease in Swedish individuals with type 2 diabetes: a nationwide register-based study. Diabetes Care. 2024;47(1):109–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ordovás JM, Smith CE. Epigenetics and cardiovascular disease. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2010;7(9):510–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wołowiec A, Wołowiec Ł, Grześk G, Jaśniak A, Osiak J, Husejko J, et al. The role of selected epigenetic pathways in cardiovascular diseases as a potential therapeutic target. Int J Mol Sci. 2023. 10.3390/ijms241813723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Felisbino MB, McKinsey TA. Epigenetics in cardiac fibrosis: emphasis on inflammation and fibroblast activation. JACC Basic Transl Sci. 2018;3(5):704–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ghazal R, Wang M, Liu D, Tschumperlin DJ, Pereira NL. Cardiac fibrosis in the multi-omics era: implications for heart failure. Circ Res. 2025;136(7):773–802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pepe G, Appierdo R, Ausiello G, Helmer-Citterich M, Gherardini PF. A meta-analysis approach to gene regulatory network inference identifies key regulators of cardiovascular diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 2024. 10.3390/ijms25084224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pan H, Ho SE, Xue C, Cui J, Johanson QS, Sachs N, et al. Atherosclerosis is a smooth muscle cell-driven tumor-like disease. Circulation. 2024;149(24):1885–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Basatemur GL, Jørgensen HF, Clarke MCH, Bennett MR, Mallat Z. Vascular smooth muscle cells in atherosclerosis. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2019;16(12):727–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marzec M, Kasprzycka M, Ptasznik A, Wlodarski P, Zhang Q, Odum N, et al. Inhibition of ALK enzymatic activity in T-cell lymphoma cells induces apoptosis and suppresses proliferation and STAT3 phosphorylation independently of Jak3. Lab Invest. 2005;85(12):1544–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Greenland C, Touriol C, Chevillard G, Morris SW, Bai R, Duyster J, et al. Expression of the oncogenic NPM-ALK chimeric protein in human lymphoid T-cells inhibits drug-induced, but not Fas-induced apoptosis. Oncogene. 2001;20(50):7386–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wu N, Li J, Li L, Yang L, Dong L, Shen C, et al. MerTK(+) macrophages promote melanoma progression and immunotherapy resistance through AhR-ALKAL1 activation. Sci Adv. 2024;10(40):eado8366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang B, Wei W, Qiu J. ALK is required for NLRP3 inflammasome activation in macrophages. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2018;501(1):246–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xu Z, Pan Z, Jin Y, Gao Z, Jiang F, Fu H, et al. Inhibition of PRKAA/AMPK (Ser485/491) phosphorylation by crizotinib induces cardiotoxicity via perturbing autophagosome-lysosome fusion. Autophagy. 2024;20(2):416–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Davis LE, Nusser KD, Przybyl J, Pittsenbarger J, Hofmann NE, Varma S, et al. Discovery and characterization of recurrent, targetable ALK fusions in leiomyosarcoma. Mol Cancer Res. 2019;17(3):676–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu C, Zhou C, Xia W, Zhou Y, Qiu Y, Weng J, et al. Targeting ALK averts ribonuclease 1-induced immunosuppression and enhances antitumor immunity in hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Commun. 2024;15(1):1009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Feng X, Lu J, Cheng W, Zhao P, Chang X, Wu J. LTK deficiency induces macrophage M2 polarization and ameliorates Sjogren’s syndrome by reducing chemokine CXCL13. Cytokine. 2025;190:156905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arslan S, Şahin N, Bayyurt B, Berkan Ö, Yılmaz MB, Aşam M, et al. Role of lncRNAs in remodeling of the coronary artery plaques in patients with atherosclerosis. Mol Diagn Ther. 2023;27(5):601–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reshetnyak AV, Murray PB, Shi X, Mo ES, Mohanty J, Tome F, et al. Augmentor α and β (FAM150) are ligands of the receptor tyrosine kinases ALK and LTK: hierarchy and specificity of ligand-receptor interactions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112(52):15862–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Honda H, Harada K, Komuro I, Terasaki F, Ueno H, Tanaka Y, et al. Heart-specific activation of LTK results in cardiac hypertrophy, cardiomyocyte degeneration and gene reprogramming in transgenic mice. Oncogene. 1999;18(26):3821–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, Cushman WC, Green LA, Izzo JL Jr., et al. Seventh report of the joint National committee on prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure. Hypertension. 2003;42(6):1206–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP). Expert panel on Detection, Evaluation, and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults (Adult treatment panel III) final report. Circulation. 2002;106(25):3143–421. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rampidis GP, Benetos G, Benz DC, Giannopoulos AA, Buechel RR. A guide for Gensini score calculation. Atherosclerosis. 2019;287:181–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu J, Chen Q, Lu L, Jin Q, Bao Y, Ling T, et al. Association of circulating IgE and CML levels with in-stent restenosis in type 2 diabetic patients with stable coronary artery disease. J Cardiovasc Dev Dis. 2022. 10.3390/jcdd9050157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen S, Li LY, Wu ZM, Liu Y, Li FF, Huang K, et al. SerpinG1: a novel biomarker associated with poor coronary collateral in patients with stable coronary disease and chronic total occlusion. J Am Heart Assoc. 2022;11(24):e027614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, Zhang YL, Castro AF 3rd, Feldman HI, et al. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150(9):604–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Pu LJ, Lu L, Xu XW, Zhang RY, Zhang Q, Zhang JS, et al. Value of serum glycated albumin and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein levels in the prediction of presence of coronary artery disease in patients with type 2 diabetes. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2006;5:27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Paul MD, Hristova K. The RTK interactome: overview and perspective on RTK heterointeractions. Chem Rev. 2019;119(9):5881–921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen MK, Hung MC. Proteolytic cleavage, trafficking, and functions of nuclear receptor tyrosine kinases. FEBS J. 2015;282(19):3693–721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang N, Li Y. Receptor tyrosine kinases: biological functions and anticancer targeted therapy. MedComm (2020). 2023;4(6):e446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mohammed KAK, Madeddu P, Avolio E. MEK inhibitors: a promising targeted therapy for cardiovascular disease. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2024;11:1404253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jeltsch M, Leppänen VM, Saharinen P, Alitalo K. Receptor tyrosine kinase-mediated angiogenesis. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2013. 10.1101/cshperspect.a009183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lei B, Wu H, You G, Wan X, Chen S, Chen L, et al. Silencing of ALOX15 reduces ferroptosis and inflammation induced by cerebral ischemia-reperfusion by regulating PHD2/HIF2α signaling pathway. Biotechnol Genet Eng Rev. 2024;40(4):4341–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang L, Lui VWY. Emerging roles of ALK in immunity and insights for immunotherapy. Cancers (Basel). 2020. 10.3390/cancers12020426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Andraos E, Dignac J, Meggetto F, NPM-ALK. A driver of lymphoma pathogenesis and a therapeutic target. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Katic L, Priscan A. Multifaceted roles of ALK family receptors and augmentor ligands in health and disease: a comprehensive review. Biomolecules. 2023. 10.3390/biom13101490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ahmed M, Kaur N, Cheng Q, Shanabrough M, Tretiakov EO, Harkany T, et al. A hypothalamic pathway for augmentor α-controlled body weight regulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2022;119(16):e2200476119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Defaye M, Iftinca MC, Gadotti VM, Basso L, Abdullah NS, Cuménal M, et al. The neuronal tyrosine kinase receptor ligand ALKAL2 mediates persistent pain. J Clin Invest. 2022. 10.1172/JCI154317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Reynolds CA, Minic Z. Chronic pain-associated cardiovascular disease: the role of sympathetic nerve activity. Int J Mol Sci. 2023. 10.3390/ijms24065378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ducray SP, Natarajan K, Garland GD, Turner SD, Egger G. The transcriptional roles of ALK fusion proteins in tumorigenesis. Cancers (Basel). 2019;11:8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hallberg B, Palmer RH. Mechanistic insight into ALK receptor tyrosine kinase in human cancer biology. Nat Rev Cancer. 2013;13(10):685–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liu Y, Chen C, Rong C, He X, Chen L. Anaplastic lymphoma kinase tyrosine kinase inhibitor-associated cardiotoxicity: a recent five-year pharmacovigilance study. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:858279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Luo Y, Zhang Z, Guo X, Tang X, Li S, Gong G, et al. Comparative safety of anaplastic lymphoma kinase tyrosine kinase inhibitors in advanced anaplastic lymphoma kinase-mutated non-small cell lung cancer: systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lung Cancer. 2023;184:107319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.