Abstract

The molecular mechanisms by which plants acclimate to oxidative stress are poorly understood. To identify the processes involved in acclimation, we performed a comprehensive analysis of gene expression in Nicotiana tabacum leaves acclimated to oxidative stress. Combining mRNA differential display and cDNA array analysis, we estimated that at least 95 genes alter their expression in tobacco leaves acclimated to oxidative stress, of which 83% are induced and 17% repressed. Sequence analysis of 53 sequence tags revealed that, in addition to antioxidant genes, genes implicated in abiotic and biotic stress defenses, cellular protection and detoxification, energy and carbohydrate metabolism, de novo protein synthesis, and signal transduction showed altered expression. Expression of most of the genes was enhanced, except for genes associated with photosynthesis and light-regulated processes that were repressed. During acclimation, two distinct groups of coregulated genes (“early-” and “late-response” gene regulons) were observed, indicating the presence of at least two different gene induction pathways. These two gene regulons also showed differential expression patterns on an oxidative stress challenge. Expression of “late-response” genes was augmented in the acclimated leaf tissues, whereas expression of “early-response” genes was not. Together, our data suggest that acclimation to oxidative stress is a highly complex process associated with broad gene expression adjustments. Moreover, our data indicate that in addition to defense gene induction, sensitization of plants for potentiated gene expression might be an important factor in oxidative stress acclimation.

Exposure to sublethal biotic and abiotic stresses renders plants more tolerant to a subsequent, normally lethal, dose of the same stress, and this phenomenon is referred to as acclimation or acquired resistance (1–3). This induced stress resistance is not restricted to the same type of stress, and cross-tolerance between different stresses has been reported (4–6). Because many stress conditions provoke cellular redox imbalances, it has been suggested that oxidative stress defenses contribute to induced abiotic and biotic stress tolerance and are a central cross-tolerance-mediating component (7). This notion is also supported by the fact that plants acclimated to heat or cold as well as plants showing acquired resistance to pathogens are all more tolerant to oxidative stress (8–10). Antioxidant defense responses have long been associated mainly with enhanced antioxidant enzyme activity and increased levels of antioxidant metabolites, such as ascorbic acid, glutathione, α-tocopherol, and carotenoids (11). More recently, induction of small heat shock proteins, the cellular protection gene glutatione S-transferase (GST), and the pathogenesis-related gene PR2 have also been associated with acquisition of oxidative stress tolerance (9, 12, 13).

Acclimatory responses to various oxidants have been extensively studied in bacteria and yeast. In bacteria, at least 80 proteins are induced by sublethal oxidative stress that triggers tolerance to lethal oxidative stress (14), whereas expression of at least 900 genes is affected in yeast (15). To learn more about the underlying molecular mechanisms of acquired resistance to oxidative stress in plants, we analyzed gene expression in tobacco leaves acclimated to oxidative stress by using mRNA differential display. This study shows the high complexity of such a process and reveals genes and mechanisms that may play a role in oxidative stress tolerance development.

Materials and Methods

Plant Material, Cultivation Conditions, and Methyl Viologen (MV) Treatment.

Nicotiana tabacum (L.) cv. Petit Havana SR1 plants were grown for 5 weeks under a photosynthetic photon fluence rate of 100 μmol m−2 s−1, a 16-hr light/8-hr dark regime, 70% relative humidity, and 24°C constant temperature. Three discs (diameter 1 cm) were punched each from different plants and floated adaxial side up on 12 ml of MV solution or solely nanopure water (controls). Ion leakage from the leaf discs was measured as conductivity of the solution with a conductivity meter (Consort, Turnhout, Belgium).

RNA Extraction and RNA Gel Blot Analysis.

Total RNA was extracted by using TRIzol Reagent (Life Technologies, Paisley, U.K.) and subjected to RNA gel blot analysis. RNA quality and equal loading were checked before hybridization by methylene blue staining. Membranes were hybridized at 65°C in 50% formamide/5× SSC/0.5% SDS/10% dextran sulfate. 32P-labeled RNA probes corresponding to the cDNA fragments of the glutathione peroxidase gene (GPx; ref. 16), the cytosolic copper/zinc superoxide dismutase (SodCc; pSOD3–5′ fragment; ref. 17), and differential display cDNA fragments were generated with the Riboprobe System (Promega). Membranes were washed at 65°C for 15 min in 3× SSC, 1× SSC, and 0.1× SSC containing 0.5% SDS. Membranes were exposed to the Storage Phosphor Screen and scanned with the PhosphorImager 445 SI (Amersham Pharmacia).

Differential Display.

Total RNA was treated with DNaseI before reverse transcription–PCR. mRNA differential display was performed with the RNA map kit (Gene Hunter, Nashville, TN) using AmpliTaq DNA polymerase (Perkin–Elmer) and (33P)dATP (0.2 μl in 20 μl PCR mix of 111,000 GBq/mmol; Isotopchim, Ganagobie-Peyruis, France). Differentially expressed sequence tags larger than 200 bp were purified from the polyacrylamide gels, reamplified, and cloned into a pGEM-T vector (Promega). Each clone was assigned a number.

DNA Sequence Analysis.

Three to six sequence tags originating from a single band were sequenced, and sequence data were analyzed by using the Genetics Computer Group (GCG; Madison, WI) package (version 9.1). The nucleotide sequences were compared with sequences deposited in the databases (GenBank, EMBL, DDBJ, PDB), and translated DNA sequences were compared with protein sequences in databases (GenBank CDS translations, PDB, SwissProt, PIR, and PRF) by using the blast algorithm (18). When no homology was found in the nonredundant protein or DNA databases, we looked in an expressed sequence tag (EST) database of the Solanaceae species for significant homologues (E value ≤ 10−3) that are longer toward the 5′ terminus. Solanaceae EST homologues then became the query sequences in a subsequent homology search. Two such tobacco cDNAs were replaced: sequence c2-1-10 with a Solanum tuberosum EST sequence (GenBank accession no. BG598026; 76% identity) and t7-5-4 with that of Lycopersicon esculentum (GenBank accession no. AI896496; 74% identity).

cDNA Array Analysis.

Cloned differential display fragments were reamplified and redissolved in 2× SSC, 0.2 M NaOH to a concentration ranging between 125–250 ng/μl. For each fragment, approximately 250 nl was spotted in triplicate on nylon Hybond N+ membranes (Amersham Pharmacia) by using a Biomek 2000 robot (Beckman). Dried membranes were UV-crosslinked at 150 mJ/cm2. Complex cDNA probes with a specific activity of ≈9 × 10−7 cpm were prepared from 1 μg mRNA by reverse transcription–PCR and used for hybridization essentially as described (19). After stringent washes in 0.2× SSC/0.1% SDS at 60°C, membranes were exposed to the Storage Phosphor Screen and scanned with a PhosphorImager 445 SI. Spot intensities were measured by using the IMAGEQUANT 4.1 software (Amersham Pharmacia). The value of each cell containing a spot was quantified and background value was then subtracted. The background value was calculated as an average of 64 empty cells distributed over the membrane. At places with unequal background, only background values of each region were taken into account. Each gene was spotted in triplicate, and the average was calculated. Constitutively expressed genes were used for normalization between the membranes. cluster and treeview software (ref. 20; http://rana.lbl.gov) were used to group and display genes with similar expression profiles. We used the default options of the average linkage hierarchical clustering with uncentered correlation metric. The expression levels of each gene were variance-normalized before cluster analysis by subtracting the mean expression value across all time points from each data point and then dividing the result by the standard deviation (21).

Results

Sensitivity of Tobacco to MV.

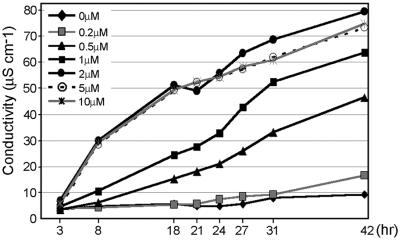

To identify genes differentially expressed in plants acclimated to oxidative stress, we developed a tobacco leaf system that expressed acquired resistance to oxidative stress. MV, a redox-active compound that enhances superoxide formation mainly in chloroplasts (22), was used to induce tolerance to oxidative stress. Although low concentrations of AOS induce defense responses (2, 12, 23–25), high concentrations of AOS induce cell death (26). To avoid expressing genes involved in cellular deterioration in our screen, we first determined sublethal MV concentrations. To this end, tobacco leaf discs were floated on solutions with different concentrations of MV, and solute conductance was monitored. Peroxidation of membrane lipids after oxidative stress results in loss of membrane integrity and increased ion leakage. Concentrations of 0.2 μM MV and lower caused only a minor increase in ion leakage compared with water-treated leaf discs, and no visible damage was observed even after 42 hr of incubation (Fig. 1; data not shown). In subsequent experiments, the above concentrations of MV were used to induce tolerance to oxidative stress. Concentrations of MV higher than 0.2 μM resulted in massive ion leakage and cell death (Fig. 1; data not shown) and were used for assessment of oxidative stress tolerance.

Fig 1.

Effect of different MV concentrations on leaf disk damage. Three leaf discs were floated on solutions with defined MV concentrations for the time periods indicated. Ion leakage was measured as conductivity of the solution. Each experiment was performed in duplicate and the values presented are the average. The conductivity of the solution was subtracted from the measured values.

Sublethal Doses of MV Acclimate Tobacco Leaves to Oxidative Stress Induced by Lethal MV Doses.

Tobacco leaf discs were floated for various time periods on MV solutions containing 0.2 μM MV or less (pretreatment) and subsequently transferred to solutions containing a lethal dose of MV for tolerance assessment (treatment). Protection against MV was most pronounced (40% decrease in solute conductance compared with controls pretreated with water) when leaf discs were pretreated with 0.1 μM MV for 17 hr (including an 8-hr dark period) and assessed for stress tolerance after an 11-hr treatment (Fig. 2A). To test whether such acclimation to MV is not just a physiological response, but involves changes in nuclear gene expression, mRNA levels of the antioxidant genes GPx and SodCc were tested by RNA gel blot analysis. Both antioxidant genes were induced in leaf discs pretreated with 0.1 μM MV, and their expression was enhanced in the acclimated samples for the entire oxidative stress treatment period (Fig. 2B). This observation demonstrated that acclimation to MV-imposed oxidative stress is not just a physiological response, but involves changes in nuclear gene expression and suggested that Gpx and SodCc play a role in enhanced tolerance.

Fig 2.

Oxidative stress tolerance by preexposure to sublethal oxidative stress. (A) Leaf discs, pretreated for 17 hr with water (gray bar) or 0.1 μM MV (black bar), were exposed to a 1-μM MV solution. At regular intervals, ion leakage was measured as conductivity of the solution. Values are averages of nine independent experiments. (B) Expression of antioxidant genes, glutathione peroxidase (GPx) and cytosolic Cu/ZnSOD (SodCc), during the treatment. Total RNA was extracted from six leaf discs sampled in two independent experiments and subjected to RNA gel blot analysis. The same membrane was used for hybridization with both genes.

Genome-Wide Expression Analysis in Acclimated Tobacco Leaves.

To elucidate the molecular processes causing enhanced tolerance to oxidative stress, genome-wide expression analysis was undertaken. Tobacco leaf discs pretreated either with water or with 0.1 μM MV for 17 hr were compared by mRNA differential display. For greater differential display accuracy, mRNA from two independent experiments was used to prepare cDNA, and reverse transcription–PCR was performed in duplicate for each RNA sample. With 80 primer combinations, 243 bands larger than 150 bp that were consistently differentially expressed between acclimated and nonacclimated samples (Table 1) were identified. Sequence analysis of 146 bands revealed that 50% of the bands contained a mixture of two or more different cDNA fragments. Therefore, unique sequences that originated from these 146 bands were reamplified, arrayed on nylon membranes, and hybridized with complex cDNA probes prepared from acclimated and nonacclimated tobacco leaf discs. Hybridization signals for cDNA fragments isolated from 135 differentially expressed bands met the background criteria (i.e., gave a signal two standard deviations above the overall background in at least one of two compared values). Expression ratios between acclimated and control samples were calculated for these genes. From the 135 bands analyzed, 53 genes were induced or repressed by at least 2-fold in samples pretreated with 0.1 μM MV. When these expression data were extrapolated to all 243 bands, 95 genes were predicted to show modified expression in acclimated leaf discs. Additionally, expression of 13 induced genes was tested and reconfirmed by RNA gel blot analysis (data not shown), validating the results of the cDNA array analysis. Of 53 differentially expressed genes, 27 were significantly (E value cutoff, 10−3) similar to genes/proteins with known or predicted function and 4 were significantly similar to predicted Arabidopsis genes still without assigned function (Table 2). Among the genes with known or predicted function are genes implicated in biotic and abiotic stress defenses, cellular protection and detoxification, energy and carbohydrate metabolism, protein synthesis, and signal transduction. Expression of these genes was mainly enhanced, except for genes encoding chloroplastic proteins (AGP, Ycf3) and a DNA-binding protein implicated in light-regulated processes (pabf; ref. 27), which were repressed.

Table 1.

Overall results of differential display and cDNA array analysis

| Bands and cDNAs | Number | % |

|---|---|---|

| Differential display | ||

| Differentially expressed bands | 243 | 100 |

| Up-regulated | 202 | 83 |

| Down-regulated | 41 | 17 |

| Bands assayed by cDNA arrays | 146 | 60 |

| cDNA array analysis | ||

| Bands scored by cDNA arrays | 135 | 100 |

| Differentially expressed cDNAs | 53 | 39 |

| Up-regulated | 44 | 83 |

| Down-regulated | 9 | 17 |

See Table 2.

Table 2.

Differentially ESTs

| Accession no. | Clone | Length, bp | Gene name (tentative) | Homologue | E value | Function (putative) | Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stress defense | |||||||

| AJ344612 | t18-2-5 | 448 | PRB1-b | Basic PRB-1b (N. tabacum) emb|X66942 | 0A | Antimicrobial protein | 19.9 |

| AJ344611 | t12-2-1 | 376 | Chitinase4 | Chitinase class 4 (Vigna unguiculata) emb|CAA61281 | 2e-07 | Antimicrobial protein | 7.3 |

| AJ344578 | c15-1-4 | 517 | CBP20 | Pathogen- and wound-inducible antifungal protein CBP20 (N. tabacum) gb|S72452 | e-159A | Antimicrobial protein | 6.5 |

| Terpenoid biosynthesis | |||||||

| AJ344602 | g2-1-2 | 228 | EAS | 5-epi-aristoiochene synthase str319 gene (N. tabacum) emb|Y08847 | 9e-43A | Phytoalexins synthesis | 18.0 |

| AJ344595 | g14-2-4 | 382 | VS | Vetispiradiene synthase (S. tuberosum) gb|AAD02223 | 5e-31 | Phytoalexins synthesis | 13.4 |

| AJ344620 | t7-5-4 | 332 | MVD | Putative mevalonate diphosphate decarboxylase (Arabidopsis thaliana) gb|AAC67348 | 4e-10AB | Terpenoid biosynthesis | 7.3 |

| AJ344605 | g6-3-7 | 397 | ATPCL | ATP citrate lyase (Capsicum annuum) gb|AAK13318 | 9e-22 | Cytosolic acetyl-CoA synthesis substrate | 13.6 |

| Phenylpropanoid biosynthesis | |||||||

| AJ344572 | a9-3-4 | 280 | ISI10a | Immediate-early salicylate-induced glucosyltransferase (IS10a) (N. tabacum) gb|U32643 | e-147A | Phenylpropanoid glucosyltransferase | 5.0 |

| AJ344574 | c11-3-3 | 200 | CCoAOMT | Caffeoyl-CoA O-methyltransferase (N. tabacum) emb|Z56282 | 2e-52A | Lignins/lignans biosynthesis | 2.5 |

| AJ344604 | g6-2-13 | 526 | LDOX | Leucoanthocyanidin dioxygenase 2, putative (A. thaliana) gb|AAG21532 | 9e-40 | Anthycyanidins biosynthesis | 2.3 |

| Cellular protection/detoxification | |||||||

| AJ344607 | g9-2-2 | 505 | MDR | P-glycoprotein/multidrug resistance-like protein (A. thaliana) emb|CAB71875 | 2e-40 | Transporter | 21.4 |

| AJ344618 | t7-4-7 | 420 | GST | Glutathione S-transferase GST 12 (Glycine max) gb|AAG34802 | 2e-10 | Detoxification | 5.9 |

| AJ344571 | a9-1-2 | 368 | EH-1 | Epoxide hydrolase (N. tabacum) gb|U57350 | 0A | Detoxification | 4.8 |

| AJ344584 | c18-1-2 | 409 | DNAJ | DNAJ protein-like (A. thaliana) emb|CAB86070 | 7e-33 | Chaperone | 4.1 |

| Energy/carbohydrate metabolism | |||||||

| AJ344613 | t18-3-7 | 389 | PI-transporter | Mitochondrial phosphate transporter (G. max) dbj|BAA31582 | 3e-16 | Mitochondrial transporter-ATP synthesis | 12.5 |

| AJ344586 | c2-1-10 | 408 | UCP | Putative uncoupling protein 3, mitochondrial (Mus musculus) ref|NP_033490 | 2e-24AB | Protons transporter, energy dissipation | 2.3 |

| AJ344614 | t18-4-18 | 306 | AGP | ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase small subunit (S. tuberosum) emb|CAA43489 | 5e-04 | Chloroplast starch biosynthesis | 0.5 |

| AJ344615 | t2-1-3 | 397 | Ycf3 | Chloroplast genome, Ycf3 protein (N. tabacum) refNC_001879 | e-98A | Assembly of photosystem I subunits | 0.5 |

| Signal transduction | |||||||

| AJ344573 | a9-7/10 | 220 | Lox1 | Lipoxygenase Lox1 (N. tabacum) emb|X84040 | e-110A | Oxylipin metabolism | 4.5 |

| AJ344609 | g9-6-1 | 269 | Lox2 | Lipoxygenase (S. tuberosum) gb|U24232 | 5e-20 | Oxylipin metabolism | 3.7 |

| AJ344617 | t7-1-14 | 506 | MFP | Multifunctional protein of glyoxysomal fatty acid β-oxidation (Brassica napus) emb|AJ000886 | 5e-13 | Oxylipin metabolism | 3.1 |

| AJ344610 | t12-1-7 | 396 | TPK | Serine/threonine/tyrosine-specific protein kinase APK1A (A. thaliana) dbj|BAA02092 | 6e-06 | Signal transduction | 7.2§ |

| AJ344596 | g14-3-4 | 289 | HRA | Hypersensitive reaction-associated Ca2+-binding protein (Phaseolus vulgaris) gb|AAD47213 | 6e-04 | Signal transduction | 3.9§ |

| AJ344616 | t7-1-12 | 550 | CIPK | Putative CBL-interacting serine/threonine kinase (A. thaliana) gb|AAG50566 | 5e-18 | Signal transduction | 2.1 |

| AJ344598 | g17-2-13 | 553 | WRKY11 | WRKY DNA-binding protein (S. tuberosum) emb|CAB97004 | 8e-44 | Transcription factor | 7.2 |

| AJ344590 | c20-1-4 | 361 | pabf | DNA-binding protein (pabf) (N. tabacum) gb|U06712 | 0A | Transcription factor | 0.5§ |

| Protein synthesis | |||||||

| AJ344575 | c14-3-4 | 333 | 60S-L23A | 60S ribosomal protein L23A (L25) (N. tabacum) gb|L18908 | e-171A | Protein synthesis | 2.6 |

| Other/unclassified | |||||||

| AJ344580 | c15-2-8 | 445 | Putative protein (A. thaliana) emb|CAB88533 | 1e-04 | 4.8 | ||

| AJ344594 | g10-1-1 | 384 | Putative ABA-responsive gene (A. thaliana) dbj|BAB11190 | 3e-10 | 4.5 | ||

| AJ344581 | c15-3-4 | 471 | Putative protein (A. thaliana) gb|AAF63779 | 9e-18 | 2.8 | ||

| AJ344603 | g20-2-20 | 337 | Putative protein (A. thaliana) gb|AAF14679 | 3e-18 | 2.4 | ||

Cloned cDNAs fragments without homology are listed here; induced: a1-1-7 (AJ344568), a14-1-4 (AJ344569), a19-3-4 (AJ344570), c14-7-4 (AJ344576), c15-1-2 (AJ344577), c15-11-4 (AJ344579), c19-3-10 (AJ344585), c2-4-1 (AJ344588), c2-9-14 (AJ344589), c3-2-4 (AJ344591), g15-4-1 (AJ344597), g18-5-1 (AJ344599), g18-7-5 (AJ344601), g6-4-4 (AJ344606), g9-2-6 (AJ344608), t7-4-8 (AJ344619); repressed: c15-7-1 (AJ344582), c15-8-5 (AJ344583), c2-11-14 (AJ344587), c4-1-2 (AJ344592), c4-3-3 (AJ344593), g18-6-5 (AJ344600).

All are BLASTX, except A = BLASTN; B = search result with Solanacae ESTs as a query sequence (see Materials and Methods for details).

Ratios between the values from 0.1 μM MV and water pretreated samples identified by cDNA array analysis.

§ Ratios where one of the values was less than background plus 2 times SD.

Differential Expression of Induced Genes During Oxidative Stress Treatment.

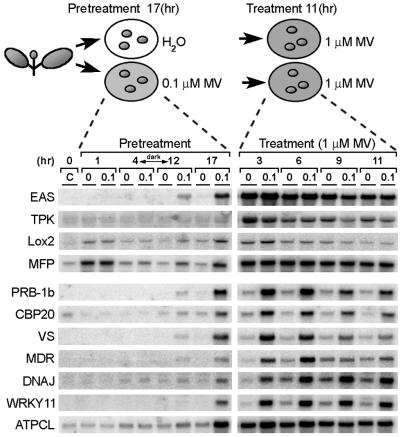

Expression of 11 selected genes was analyzed during 0.1 μM MV pretreatment (acclimation) and subsequent 1 μM MV treatment (oxidative stress; Fig. 3). During the first 4 hr of pretreatment, there was no discernible induction of gene expression, except for genes coding for the multifunctional protein (MFP) and lipoxygenase 2 (Lox2) induced in both water and samples pretreated with MV, probably as a consequence of leaf disk preparation. After 12 hr, all genes were induced in samples exposed to 0.1 μM MV. However, at this time point, induction was rather low, probably reflecting the preceding 8-hr dark period (without photosynthetic activity) required for maximal generation of superoxide by MV. As further support to this hypothesis, mRNA induction was stronger in the light during the last 5 hr of the pretreatment.

Fig 3.

Expression of genes isolated by mRNA differential display during pretreatment with 0.1 μM MV and treatment with 1 μM MV. Total RNA was extracted from nine leaf discs sampled at the indicated times before (C) and during pretreatment with 0.1 μM MV (0.1) or water (0), and after exposure of pretreated samples to 1 μM MV. Blots were prepared in quadruplicate and each membrane was reused several times.

In the subsequent 1 μM MV treatment, all genes were induced in the nonacclimated samples and (except for Lox2) further induced in the acclimated samples. Essentially, two different expression patterns were recognized. One group of genes (EAS, TPK, Lox2, and MFP) was induced rapidly by 1 μM MV (peaking between 3 and 6 hr) and to the same levels in both nontreated and pretreated samples (Fig. 3). In a second group of genes (PRB-1b, CBP20, VS, MDR, DNAJ, and WRKY11), the induction was rather slow, reaching maximum expression levels between 6 and 9 hr in nonacclimated samples and 3 and 6 hr in acclimated samples. Expression of the second group of genes was higher in the acclimated samples for at least 6 hr after treatment with 1 μM MV and was never as high in nonacclimated samples. The transcript levels of all genes tested decreased toward the end of the treatment. A similar expression pattern was observed for the antioxidant genes GPx and SodCc (Fig. 2). The kinetics of ATPCL expression was intermediate in character: expression was augmented in acclimated samples, but the induction kinetics resembled those of the first gene group.

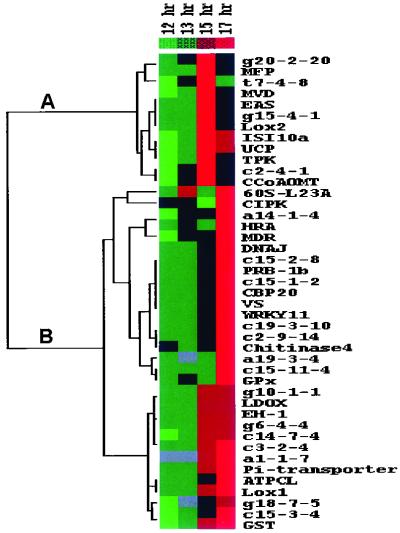

Two Major Regulons of Coexpressed Genes Defined by Cluster Analysis.

Differential expression of selected genes during oxidative stress treatment indicated that different pathways might operate in gene activation by MV. To explore this possibility, a more detailed analysis of gene expression during 0.1 μM MV pretreatment was performed. Because 0.1 μM MV had the most profound effect on gene expression during the last 5 hr of pretreatment and gene induction caused by leaf disk preparation had already been attenuated at this time (Fig. 3), leaf discs were harvested after 12, 13, 15, and 17 hr of 0.1 μM MV pretreatment. The expression of 44 induced genes and that of GPx was assessed by cDNA array analysis and the data were subjected to hierarchical clustering (20). Two genes were excluded before cluster analysis because time course analysis showed that induction observed by comparing acclimated and control samples at 17 hr resulted from decreased expression in control samples and not from induction in MV-pretreated samples (data not shown). Based on the gene expression profiles, two large clusters of coregulated genes (regulons) were identified (Fig. 4). One cluster (Fig. 4A) contained genes whose expression peaked before the end of the pretreatment at 15 hr and then decreased (early-response genes). Expression of genes of the second cluster (Fig. 4B) remained high until the end of the pretreatment (late-response genes). Interestingly, genes with augmented expression in acclimated leaf discs during oxidative stress treatment (PRB-1b, CBP20, VS, MDR, DNAJ, WRKY11, GPx, and ATPCL) all belonged to the late-response gene cluster, whereas the others (EAS, TPK, Lox2, and MFP) were a part of the early-response gene cluster. Clustering of genes suggests that they function in similar cellular processes and/or are regulated by the same signaling pathways (20). Thus, expression of genes induced in acclimated tobacco leaf discs seems regulated in an MV-dependent manner via at least two different signaling pathways, and the two groups of coregulated genes may play a differential role in oxidative stress acclimation.

Fig 4.

Clustered display of data from time course expression analysis during pretreatment with 0.1 μM MV. Expression of induced genes isolated by mRNA differential display and of GPx was analyzed during the last 5 hr of pretreatment with MV. Control expression values of samples pretreated with water were subtracted from those pretreated with MV. Data were variance-normalized and subjected to hierarchical cluster analysis (see Materials and Methods). Each gene is represented by a single row of colored boxes and each time point by a single column. Induction (or repression) with respect to mean expression over the four time points ranges from pale to saturated red (or green). Gray boxes are missing values. (A) Node of the clusterogram with the early-response genes. (B) Node of the clusterogram with late-response genes.

Discussion

To characterize molecular responses associated with oxidative stress tolerance development in plants, we performed genome-wide gene expression analysis in tobacco leaf discs acclimated to oxidative stress. When we used mRNA differential display, we found that at least 95 genes modulate their expression more than 2-fold in the acclimated leaf discs. In total, 4,712 bands were scored that should display ≈5,370 different mRNAs, as estimated by the sequencing of 146 bands (data not shown). Thus, based on the analysis of this subpopulation of genes, ≈1.8% of tobacco genes are predicted to alter their expression in acclimated leaf discs. These data are comparable with the results of Desikan et al. (28), who showed that 2.1% of the Arabidopsis genes have an 1.5-fold altered expression after exposure to H2O2. However, this comparison has to be considered with caution because of the different experimental conditions used. Arabidopsis cell suspension was exposed to H2O2 for only a short period (up to 3 hr), when predominantly early genes are expected to be induced, which is in agreement with the underrepresentation of late defense genes, such as antioxidant and pathogen defense genes, among the set of induced genes (28).

Sequence similarity to known or predicted genes was found for 27 tobacco cDNA fragments, 50% of all sequenced cDNAs. The high percentage of cDNAs without homologies in the sequence database is probably caused by the fact that the isolated cDNAs contain mainly 3′ untranslated regions, in which sequence divergence is very high. Among the isolated gene fragments, we identified genes and gene classes that have not previously been associated with acclimation to oxidative stress (Table 2). Several of them have already been shown or can be predicted to have cytoprotective or detoxifying functions, e.g., MDR that encodes an ABC transporter implicated in mammalian cells in the extrusion of amphiphilic drugs and toxic metabolites (29), DNAJ that encodes a molecular chaperone, and EH-1 that encodes an epoxide hydrolase involved in the conversion of highly reactive epoxides to less harmful diols (30). Detoxification reactions can be directed toward the oxidized cellular molecules, but also toward the MV itself and as such, acclimation of plant cells to low levels of MV may also enhance MV detoxification reactions.

Genes coding for enzymes of the phenylpropanoid pathway (ISI10a, CCoAoMT, and LDOX) and terpenoid phytoalexin pathway (MVD, EAS, and VS) are also induced in acclimated leaf discs. Although metabolites synthesized by these enzymes, namely scopolin, lignins, lignans, anthocyanins, and sesquiterpenes, have been mainly implicated in defense reactions against pathogens and UV (3, 31–33), many of them can act as antioxidants as well (34–37). Expression of genes encoding chloroplastic (Ycf3, AGP) and mitochondrial (UCP, Pi-transporter) proteins is also affected by MV pretreatment, suggesting that acclimation to oxidative stress may require physiological adaptations in these compartments. The level of Ycf3 mRNA coding for a chloroplastic protein implicated in photosystem I assembly (38) decreases, like mRNA coding for ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase (AGP), a chloroplast starch biosynthesis protein. Down-regulation of photosynthesis-related genes may reflect inhibition of the photosynthesis, which occurs under diverse stress conditions and minimizes AOS production from electron transport chains in chloroplasts (39). Down-regulation of a range of photosynthesis-related genes was observed also in Arabidopsis cells exposed to H2O2 (28). In mitochondria, which are an important source of AOS under environmental stress conditions, generation of AOS can be suppressed by means of uncoupling of the mitochondrial respiratory chain and membrane potential (40). In acclimated leaf discs, the transcript encoding a putative mitochondrial uncoupling protein (UCP) is enhanced. Together, these data suggest that the reduction of AOS formation from electron transport chains is an additional way in which plants acclimate to oxidative stress.

Several signal transduction genes are up-regulated in acclimated leaf discs and may be essential for establishment of oxidative stress tolerance (Table 2), for example, CIPK, which encodes a homologue of the calcineurin B-like calcium sensor (CBL)-interacting protein kinases. Complexes formed between different CBL and CIPK proteins may recognize distinct calcium signals and translate them into specific responses (41). H2O2 transiently increases cytosolic Ca2+ levels (42) and, as such, can employ a CBL–CIPK pathway for induction of oxidative stress defense genes. Several transcription factors that control oxidative stress regulons in bacteria and yeast have been identified (14, 15). However, plant transcription factors involved in oxidative stress still await their discovery. WRKY11 encodes a WRKY-like DNA-binding protein (43), and its expression correlates with enhanced tolerance to oxidative stress in acclimated samples. Therefore, WRKY11 may be a candidate for the transcription factor that regulates expression of oxidative stress defense genes. Alternatively, WRKY11 may regulate expression of pathogen defense genes, as shown for several other members of this gene superfamily (43). Antimicrobial genes (PRB1b, CBP20, and Chitinase4) are induced in acclimated tobacco leaf discs, similarly as observed previously for Arabidopsis plants acclimated to photooxidative stress (13). H2O2 originating from the oxidative burst is a signal for induction of these genes on pathogen recognition (23, 24) and can explain why they are induced in acclimated tobacco leaf tissues. Acquired tolerance to biotic and abiotic stresses is generally thought to result from physiological adaptation as well as induction of defense genes and proteins in acclimated tissues. Most genes, including antioxidant and cellular protection genes, are not only induced in acclimated leaf discs but also show enhanced expression in acclimated leaf discs during exposure to severe oxidative stress. Such expression levels are never reached in nonacclimated leaf discs, even after prolonged exposure to MV, showing that pretreatment with a sublethal dose of oxidative stress sensitizes plants to much stronger gene induction during oxidative stress. Potentiation of the expression of a few defense genes has been observed on prior stress exposure or stress hormone pretreatment and has usually been correlated with the establishment of tolerance against biotic and abiotic stresses in such pretreated plants (44–47). Here, we have shown that acclimation to oxidative stress involves concerted potentiation of different sets of defense genes. Together these results suggest that sensitization of stress-regulated pathways for rapid and high gene expression may be one of the essential elements in stress acclimation. Salicylic acid has been mainly implicated in potentiation of gene expression (44), although other signal molecules, such as jasmonic acid, systemin, ethylene, and β-aminobutyric acid, have been shown to play a similar role (46–48). Here we show that pretreatment with sublethal levels of MV sensitized plants for higher gene expression, thus indicating that AOS can play a role in potentiation of gene expression as well. Genes with a potentiated expression during oxidative stress also have a different expression pattern during MV pretreatment (acclimation) compared with other genes, suggesting that their expression is regulated by MV via a distinct signaling pathway. Another group of coregulated genes (early-response genes) does not show augmented pattern of expression during the oxidative stress. Preinduction of these genes may provide some advantages to acclimated samples, but the transient nature of their induction suggests that they may be rather involved in immediate defense responses or may have other functions, such as generation of secondary signals for triggering inducible defense responses.

In conclusion, we have partially characterized the transcriptome associated with establishment of oxidative stress tolerance in plants. This comprehensive analysis has indicated that acclimation to oxidative stress is a complex process, involving concerted induction of functionally different groups of genes. In addition, our data strongly suggest that potentiation of defense gene expression may be essential for acclimation. Furthermore, based on our results, a previously uncharacterized role for AOS in stress defense responses can be proposed that is, in addition to defense gene induction (2, 12, 23–25, 28), also orchestration of their potentiated expression in acclimated tissues.

Acknowledgments

We thank S. Morsa, I. Gadjev, S. Rombauts, K. Vandepoele, and the sequencing group for technical assistance and help with the sequence analysis, H. Tuominen and J. Kangasjärvi (Institute of Biotechnology, University of Helsinki, Finland) for introducing us to the cDNA array protocol, F. Van Breusegem for critically reading the manuscript and providing many helpful suggestions, and M. De Cock and R. Verbanck for helping to prepare it. This work was supported by the European Union BIOTECH Program (Grant ERB-BIO4-CT96-0101).

Abbreviations

AOS, active oxygen species

EST, expressed sequence tag

MV, methyl viologen

References

- 1.Vierling E. (1991) Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol. 42 579-620. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Prasad T. K., Anderson, M. D., Martin, B. A. & Stewart, C. R. (1994) Plant Cell 6 65-74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sticher L., Mauch-Mani, B. & Métraux, J. P. (1997) Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 35 235-270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Orzech K. A & Burke, J. J. (1998) Plant, Cell Environ. 11 711-714. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Keller E. & Steffen, K. L. (1995) Physiol. Plant. 93 519-525. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cloutier Y. & Andrews, C. J. (1984) Plant Physiol. 76 595-598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bowler C. & Fluhr, R. (2000) Trends Plant Sci. 5 241-246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Strobel N. E. & Kuć, J. A. (1995) Phytopathology 85 1306-1310. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Banzet N., Richaud, C., Deveaux, Y., Kazmaizer, M., Gagnon, J. & Triantaphylidès, C. (1998) Plant J. 13 519-527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Seppänen M. M., Majaharju, M., Somersalo, M. & Pehu, E. (1998) Physiol. Plant. 102 454-460. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Inzé D. & Van Montagu, M. (1995) Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 6 153-158. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Karpinski S., Reynolds, H., Karpinska, B., Wingsle, G., Creissen, G. & Mullineaux, P. (1999) Science 284 654-657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mullineaux P., Ball, L., Escobar, C., Karpinska, B., Creissen, G. & Karpinski, S. (2000) Phil. Trans. R. Soc. London B 355 1531-1540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Demple B. (1991) Annu. Rev. Genet. 25 315-337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gasch A. P., Spellman, P. T., Kao, C. M., Carmel-Harel, O., Eisen, M. B., Storz, G., Botstein, D. & Brown, P. O. (2000) Mol. Biol. Cell 11 4241-4257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Criqui M. C., Jamet, E., Parmentier, Y., Marbach, J., Durr, A. & Fleck, J. (1992) Plant Mol. Biol. 18 623-627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tsang E. W. T., Bowler, C., Hérouart, D., Van Camp, W., Villarroel, R., Genetello, C., Van Montagu, M. & Inzé, D. (1991) Plant Cell 3 783-792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Altschul S. F., Madden, T. L., Schäffer, A. A., Zhang, J., Zhang, Z., Miller, W. & Lipman, D. J. (1997) Nucleic Acids Res. 25 3389-3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Overmyer K., Tuominen, H., Kettunen, R., Betz, C., Langebartels, C., Sandermann, H., Jr. & Kangasjärvi, J. (2000) Plant Cell 12 1849-1862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eisen M. B., Spellman, P. T., Brown, P. O. & Botstein, D. (1998) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95 14863-14868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tavazoie S., Hughes, J. D., Campbell, M. J., Cho, R. J. & Church, G. M. (1999) Nat. Genet. 22 281-285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Halliwell B. & Gutteridge, J. M. C., (1989) Free Radicals in Biology and Medicine (Clarendon, Oxford).

- 23.Wu G., Shortt, B. J., Lawrence, E. B., León, J., Fitzsimmons, K. C., Levine, E. B., Raskin, I. & Shah, D. M. (1997) Plant Physiol. 115 427-435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alvarez M. E., Pennell, R. I., Meijer, P.-J., Ishikawa, A., Dixon, R. A. & Lamb, C. (1998) Cell 92 773-784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lopez-Delgado H., Dat, J. F., Foyer, C. H. & Scott, I. M. (1998) J. Exp. Bot. 49 713-720. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Levine A., Tenhaken, R., Dixon, R. & Lamb, C. (1994) Cell 79 583-593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tjaden G. & Coruzzi, G. M. (1994) Plant Cell 6 107-118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Desikan R., A.-H.-, Mackerness, S., Hancock, J. T. & Neill, S. J. (2001) Plant Physiol. 127 159-172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Coleman J. O. D., Blake-Kalff, M. M. A. & Davies, T. G. E. (1997) Trends Plant Sci. 2 144-151. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guo A., Durner, J. & Klessig, D. F. (1998) Plant J. 15 647-656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ahl Goy P., Signer, H., Reist, R., Aichholz, R., Blum, W., Schmidt, E. & Kessmann, H. (1993) Planta 191 200-206. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stapleton A. E. (1992) Plant Cell 4 1353-1358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Keller H., Czernic, P., Ponchet, M., Ducrot, P. H., Back, K., Chappell, J., Ricci, P. & Marco, Y. (1998) Planta 205 467-476. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lamb C. & Dixon, R. A. (1997) Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol. 48 251-275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rice-Evans C. A., Miller, N. J. & Paganga, G. (1997) Trends Plant Sci. 2 152-159. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chong J., Baltz, R., Fritig, B. & Saindrenan, P. (1999) FEBS Lett. 458 204-208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Haraguchi H., Ishikawa, H., Sanchez, Y., Ogura, T., Kubo, Y. & Kubo, I. (1997) Bioorg. Med. Chem. 5 865-871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Naver H., Boudreau, E. & Rochaix, J.-D. (2001) Plant Cell 13 2731-2745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Krause G. H. (1994) in Causes of Photooxidative Stress and Amelioration of Defense Systems in Plants, eds. Foyer, C. H. & Mullineaux, P. M. (CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL), pp. 43–76.

- 40.Kowaltowski A. J., Costa, A. D. T. & Vercesi, A. E. (1998) FEBS Lett. 425 213-216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Albrecht V., Ritz, O., Linder, S., Harter, K. & Kudla, J. (2001) EMBO J. 20 1051-1063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Price A. H., Taylor, A., Ripley, S. J., Griffiths, A., Trewavas, A. J. & Knight, M. R. (1994) Plant Cell 6 1301-1310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Eulgem T., Rushton, P. J., Robatzek, S. & Somssich, I. E. (2000) Trends Plant Sci. 5 199-206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mur L. A. J., Naylor, G., Warner, S. A. J., Sugars, J. M., White, R. F. & Draper, J. (1996) Plant J. 9 559-571. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Knight H., Brandt, S. & Knight, M. R. (1998) Plant J. 16 681-687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zimmerli L., Jakab, G., Métraux, J.-P. & Mauch-Mani, B. (2000) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97 12920-12925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Conrath U., Thulke, O., Katz, V., Schwindling, S. & Kohler, A. (2001) Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 107 113-119. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lawton K. A., Potter, S. L., Uknes, S. & Ryals, J. (1994) Plant Cell 6 581-588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]