Abstract

Long-term information is crucial for enhancing our ability to predict ecosystem trajectories under adaptive management and climate change scenarios. In this study, we assessed how the systematic incorporation of information affects our predictive capacity regarding the response of a target variable, offering insights into ecosystem dynamics and highlighting the importance of long-term data. We analyzed over 20 years of aboveground net primary production (ANPP) data across three highly dynamic dryland ecosystems in a grassland-to-shrubland transition zone. Our approach, widely applicable for testing long-term observations, involved modeling probability distributions, temporal semivariograms, and copula-based dependency functions between annual precipitation and ANPP. Our results indicate non-linear trends in prediction capacity as more data are included, demonstrating emergent unexpected responses not evident in short-term observations. These dynamic and non-stationary responses pose significant challenges for prediction, even with over 20 years of data, underscoring the need for ongoing measurements. Our findings emphasize the importance of long-term temporal variability for understanding trends and resilience of ecosystem processes. Quantitative methodologies for assessing predictive capacity and identifying trends are essential for making informed decisions regarding the continuation or termination of long-term monitoring initiatives. We strongly advocate for the sustained support of long-term ecological research, as it is crucial for deepening our understanding of ecosystem responses and for guiding effective management and policy decisions.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00442-025-05807-z.

Keywords: Carbon cycle, Copula-based modeling, Forecasting, LTER, Precipitation variability

Introduction

Long-term observations and experiments are essential for understanding the intricate dynamics of ecosystems and elucidating the mechanisms that govern their responses to environmental changes (Lindenmayer et al. 2012; Vucetich et al. 2020; Brown and Collins 2023). Indeed, such studies are often required to distinguish meaningful signals from noise in complex dynamic natural systems (Sala et al. 1988). Moreover, results from long-term research could disproportionately impact policy decisions (Hughes et al. 2017). Therefore, elucidating the evolving temporal patterns, dependency relationships, and natural behaviors of key ecological variables (e.g., population dynamics, net primary production) is crucial for managing non-native species and forecasting the responses of biogeochemical cycles under different scenarios. In this context, ecologists and environmental managers acknowledge that long-term studies are essential for understanding the complex temporal and spatial dynamics of ecological processes, thereby generating the knowledge needed to manage natural resources (Callahan 1984; Likens et al. 1996).

Although many researchers recognize and value the utility of long-term observations and experiments, one challenge that is rarely discussed or evaluated is when to stop a long-term study (e.g., Rees et al. 2001, on vegetation dynamics; Lindenmayer et al. 2012, on ecology studies; Tetzlaff et al. 2017, on hydrology and water management; Magurran and McGill (2010), on biological diversity; Sullivan et al. 2018, on environmental science and policy; Rastetter et al. 2021, on ecological research networks). One of the more common arguments in support of long-term studies is that they have a greater chance of encountering rare or extreme events (e.g., Ratajczak et al. 2022). Long-term studies are the only ones that can better capture natural variability and detect trends over time scales relevant to environmental change (Parmesan and Yohe 2003; Magurran et al. 2010; Likens and Lindenmayer 2018). Therefore, long-term studies increase in value over time, as does their applicability toward understanding mechanisms, forecasting responses, and informing management and policy decisions (Lindenmayer et al. 2012; Keenan 2015; Hughes et al. 2017).

Contrasted with these advantages, programmatic support for long-term studies has declined, making it even more challenging to locate and justify funding to carry on these efforts (Kuebbing et al. 2018; Vucetich et al. 2020). In some cases, long-term datasets have been passed down from one generation of researchers to the next (Hobbie et al. 2003). In other cases, long-term projects end when an investigator retires or dies, which may or may not correspond to the current or future utility of a long-term study. Therefore, understanding when to decrease or end long-term sampling efforts is essential to justify continued funding or determine whether a study should end. These analyses and justifications are imperative as evidence shows that funds for long-term research do not keep up with inflation, and there has been a decline in funding for long-term research (Vucetich et al. 2020).

In this study, we used long-term data (over 20 years of measurements) of aboveground net primary production (ANPP) and precipitation variability from three dryland ecosystems spanning a grassland to shrubland transition zone (Rudgers et al. 2018). Drylands occupy over 30% of the Earth’s surface and are critical for regulating the variability of the global carbon budget (Poulter et al. 2014). Furthermore, dryland transition zones denote areas where ecological processes are very sensitive to climatic and land-use changes (Huang et al. 2017; Peters et al. 2019; Wu et al. 2024). Most of them experience periodic droughts, shifting precipitation patterns, and changing species composition; hence, long-term measurements are critical to understanding the dynamics of ecosystems under pervasive climate change (Smith et al. 2009).

Our overarching goal was to test how systematically adding information influences our prediction capacity, providing insights into the value of long-term measurements and evaluating whether these efforts should be continued. We embrace a holistic approach encompassing modeling probability distributions, temporal semivariograms, and copula-based dependency functions between ANPP and precipitation in three dryland ecosystems. By adopting this systematic methodology, we quantified the evolving distributions, temporal dependencies, and dependency relationships within multiple long-term datasets. This comprehensive analysis is based on geostatistical principles (Le et al. 2020; Le and Vargas 2024) and provides an understanding of the natural behavior of annual precipitation and ANPP over time, enabling us to discern trends and fluctuations that offer insights into the value of long-term monitoring efforts.

We hypothesized that modeling prediction capacity will increase as more data are included and analyzed within a time series. In other words, as more information is included, the relationships between precipitation and ANPP will become highly predictable, as long-term datasets should increasingly capture year-to-year changes in precipitation and ANPP under natural variability. It is expected that long-term datasets reveal the influence of climate variability (Hsu et al 2012; Knapp et al 2017; Felton et al. 2021), lag responses (Sala et al. 2012; Gutiérrez et al. 2020), and plant community dynamics (Heisler‐White et al. 2009; Komatsu et al. 2019; Seabloom et al. 2021) because their information is more representative of ecosystem processes rather than short-term datasets (e.g., 1–5 years). However, the modeling prediction capacity may not always increase consistently (i.e., linearly) as more data are included through long-term observations because temporal variability may influence the response variable in unexpected ways (e.g., non-linearly and non-stationarily, or through thresholds). Consequently, as more data are included, modeling prediction capacity could fluctuate, implying that long-term observations must continue to capture systematic and emergent ecosystem patterns.

Methods

Study site

This research utilized over twenty years of data (1999–2022) collected from three long-term study sites at the Sevilleta National Wildlife Refuge (SNWR) in central New Mexico, USA. In the SNWR, Great Plains grassland, primarily composed of blue grama (Bouteloua gracilis), transitions into the Chihuahuan Desert shrubland, which is dominated by creosote bush (Larrea tridentata). This transition occurs along a north-to-south gradient, with a narrow ecotone of Chihuahuan Desert grassland dominated by black grama (Bouteloua eriopoda; Gosz 1993; Gosz & Gosz 1996). In each of these ecoregions, the dominant species constitute up to 80% of the total ANPP (Muldavin et al. 2008; Rudgers et al. 2018).

ANPP was assessed using a non-destructive allometric scaling method, which involved measuring the height and cover of individual plants within 40 to 80 permanently established 1 m2 quadrats at each of the three study sites during the spring (April–May) and fall (September–October) growing seasons each year (Muldavin et al. 2008). ANPP measurements in the Chihuahuan Desert grassland and shrubland started in 1999, and in 2002 in the Great Plains grassland. To estimate species-level ANPP, linear regression models based on weight-to-volume ratios were developed from reference specimens (Rudgers et al. 2019) collected in the area and reported in previous studies (Rudgers et al. 2018; Brown and Collins 2023). Annual ANPP was calculated as the sum of peak seasonal (spring or fall) ANPP for each species.

Time series analysis

We applied a toolset of geostatistical methods to examine and interpret the data gathered at regular time intervals (i.e., time series). This procedure included exploring and modeling the characteristic functions (Le 2021; Vázquez-Ramírez et al. 2023; Vargas and Le 2023; Guera et al. 2023; Le and Vargas 2023; Zapata-Norberto et al. 2024), which are univariate probability distribution functions, temporal autocorrelation functions, and dependency relationship functions of the variables in the data evolution of time series. Once these characteristic functions have been constructed through the modeling procedure, we can derive mathematical models that describe the natural behavior of the variables studied over time for each site. After that, we can compare the variation of these models over time using the inferred mathematical models. To do this, we developed a workflow consisting of five steps: (a) Input data; (b) Modeling the univariate probability distribution function, (c) Modeling the temporal semivariogram function; (d) Modeling the dependency functions between variables; and (e) Calculating the combined modeling error. This workflow was independently applied to each dataset to observe how model errors changed as more data were included in the modeling procedure for each ecosystem.

Input data

Let Sn = (X, Y) = {(x1, y1), (x2, y2), …, (xn, yn)} be the observation of two variables in a time series with the same amount of data n. Where X is the independent variable (i.e., annual precipitation) and Y is the dependent variable (i.e., ANPP). We assume that all data (Sn) of Y represent the reality of the natural phenomenon of the variable ANPP. Then, we explored the basic univariate statistical properties related to the distribution of the marginal or univariate probability distribution (e.g., mean, median, standard deviation, etc.) and the bivariate statistical properties that characterize the dependence relationship between the variables. (i.e., linear and non-linear correlation coefficients such as Pearson, Spearman, and Kendall). Next, we modeled the characteristic functions (i.e., the univariate probability distribution functions, the temporal semivariogram functions, and the dependency functions between variables) as we systematically increased the data from the first year (i = 1 year of data) to the last year (i = n years of data). Finally, we compared the parameters of the models obtained during the iterative modeling over the years (i.e., by systematically including more data where i = {1, 2, …, n − 1}) with the model parameters obtained from the full dataset (Sn). This approach allows us to examine modeling errors over the years in which the data were collected and incorporated.

-

b.

Modeling the univariate distribution function

We assumed that all data for variable Y are normally distributed owing to its simplicity, ease of interpretation, and natural behavior of the variable. Then, as the data increased over time, we fitted a Gaussian distribution to the data sets for variable Y using the fitdistr function from the “MASS” package (Venables and Ripley 2002) and the data sets were: S1 = {(x1,y1)}, S2 = {(x1, y1), (x2, y2)}, …, Sn − 1 = {(x1, y1), (x2, y2), …,(xn − 1, yn − 1)}, Sn = {(x1, y1), (x2, y2), …,(xn − 1, yn − 1), (xn, yn)}. For each data set Si, a Gaussian distribution model was fitted to the variable Y to obtain two parameters of this model: mean and standard deviation. The differences in these parameters were then compared with those of the Gaussian distribution model obtained from all the Sn data of the variable Y. This comparative analysis provided information on the changes in the parameters of the probability distribution function model as the set of data increased over time. These changes are expected to decrease as the measurements increase over the years. When these changes reach a global minimum very close to zero and oscillate around zero over time, it means that the process of change has for the most part, already been established. Then, we can obtain a more reliable and representative univariate probability distribution model of the variable studied. If not, we conclude that long-term measurements must continue to be collected in a particular experiment.

-

c.

Modeling the temporal semivariogram function

An empirical semivariogram was calculated for each dataset Si for variable Y using the variog function from the “geoR” package (Ribeiro et al. 2020) to capture the temporal variability inherent within the data. Following this, for each data set Si, a spherical semivariogram model was fitted for the variable Y using the variofit function from the “geoR” package to obtain three parameters of that model: nugget, sill, and temporal correlation range. Note that although a fixed variogram model (i.e., a spherical variogram model) was established for all datasets, the model parameters may change as more data are added. Then, the differences between these model parameters and the fitted spherical semivariogram model obtained from all data Sn of the variable Y were calculated. This comparative analysis provided information about the changes in the parameters of the temporal autocorrelation function as the dataset increases in time. Similar to the change in the probability distribution function, these changes are expected to decrease as the measurements accumulate over time. When these changes reach a global minimum of around zero and remain oscillating around zero over the years, it suggests that the process of change has stabilized. At this point, a more reliable and representative temporal semivariogram model of the variable can be obtained. Otherwise, the results suggest that further measurements will be necessary to enhance the reliability of the temporal variability model, and long-term measurements must continue to be collected in the particular experiment.

-

d.

Modeling the dependency function between variables

For each data set Si, a parametric copula function model was fitted on the pseudo-observations between the variables X and Y using the BiCopSelect function from the “VineCopula” package (Nagler et al. 2023) to obtain two parameters: the copula parameter and the value of Kendall’s tau. The pseudo-observations were generated and plotted as a scatterplot between the empirical probability distributions of variables X and Y. Then, the differences between these parameters and those of the fitted parametric copula function model obtained from all data Sn of the variables X and Y were calculated. This comparative analysis provided information about changes in the parameters of the parametric copula function as the dataset increases in time. Similar to the changes in the probability distribution function and the semivariogram function, these changes are expected to decrease as the measurements accumulate over time. When these changes reach a global minimum close to zero and remain with slight variations around zero over the years, it means that the process of changes has more or less been established. Then, we can obtain a more reliable and representative parametric copula model that accurately represents the dependency relationship between the variables under study. If this is not achieved, we conclude that long-term measurements must continue to be collected in a particular experiment.

-

e.

Calculating the combined modeling error

We standardized the seven parameters (i.e., mean, standard deviation, nugget, sill, correlation range, copula parameter, and Kendall's tau value) of the three characteristic functions mentioned above and their corresponding errors or differences over the years. Therefore, the errors were transformed into a standardized scale ranging from 0 to 1. This standardization was done through a simple function ei = rank(ei)/(n + 1), where i = 1, 2, …, n. This approach facilitated comparative analysis because equal weight is placed on error points over the years. Next, these standardized errors were aggregated with the same weight to derive a combined modeling error (i.e., Error), where the characteristic functions have equal importance, as shown below:

where m = 7 parameters, and k = 1,2,..,m corresponds to the error of parameters: mean, standard deviation, nugget, sill, correlation range, the copula parameter, and the value of Kendall's tau, respectively. This combined modeling error was calculated for each ANPP data set separately. If this combined modeling error remains around zero and is maintained over time, it indicates that the model captures the patterns and variability of the dataset. Otherwise, the model is not accurate, and long-term measurements must continue. Moreover, for each dataset, we calculated the moving variances corresponding to a window of 5 years. For each dataset, this computation was performed using a moving window of equal value to the temporal autocorrelation range of the variable Y, thereby providing a robust measure representative of the temporal dependency of the variable Y. The algorithm is implemented using tools from RGEOSTAD (Díaz-Viera et al. 2021) and coded in R software (R Core Team 2022).

Results

Input data

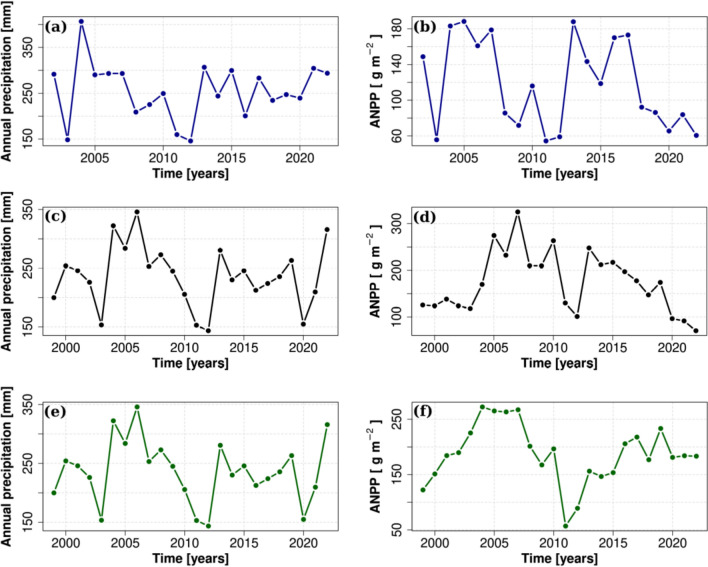

The Great Plains grassland dominated by blue grama included 21 years of ANPP data (Fig. 1a, b), with a mean of 118.25 [g m−2], a median of 115.93 [g m−2], a standard deviation of 50.21 [g m−2], and a skewness of 0.13. No outliers were observed. Mean annual precipitation at this site was 255.47 [mm], with a median of 249.40 [mm], a standard deviation of 62.07 [mm], and a skewness of 0.07. The linear and nonlinear dependence coefficients between annual precipitation and ANPP using Pearson, Spearman, and Kendall correlations were 0.63, 0.58, and 0.43, respectively, indicating a moderate positive correlation.

Fig. 1.

Annual precipitation (mm; left panels) and aboveground net primary production (ANPP, g m⁻2; right panels) for three ecosystems at the Sevilleta National Wildlife Refuge, New Mexico: Great Plains grassland (2002–2022; a, b), Chihuahuan Desert grassland (1999–2022; c, d), and Chihuahuan Desert shrubland (1999–2022; e, f). Time series highlight interannual variability and long-term trends in precipitation and ANPP

The Chihuahuan Desert grassland dominated by black grama contains information from over 24 years of annual precipitation and ANPP (Fig. 1c, d), with a mean ANPP of 174.12 [g m−2], a median of 171.97 [g m−2], a standard deviation of 65.70 [g m−2], and a skewness of 0.44. Mean annual precipitation at this site was 236.52 [mm], with a median of 240.32 [mm], a standard deviation of 53.47 [mm], and a skewness of 0.03. Also, the coefficient for linear dependence, as represented by the Pearson correlation, between annual precipitation and ANPP was computed at 0.39, indicating a low positive correlation. Moreover, nonlinear dependence coefficients, as represented by Spearman and Kendall, were calculated to be 0.42 and 0.30, respectively.

The Chihuahuan Desert shrubland dominated by creosote bush included 24 years (Fig. 1e, f), with a mean ANPP of 187.06 [g m−2], a median of 184.17 [g m−2], a standard deviation of 53.98 [g m−2], and a skewness of − 0.38. Mean annual precipitation was 236.52 [mm], with a median of 240.32 [mm], a standard deviation of 53.47 [mm], and a skewness of 0.03. Also, the linear and nonlinear dependence coefficients between annual precipitation and ANPP utilizing Pearson, Spearman, and Kendall correlations were calculated as 0.58, 0.46, and 0.31, respectively, indicating a moderate positive correlation.

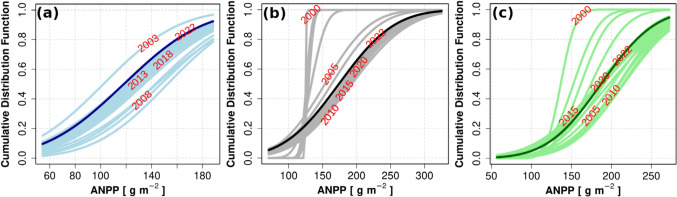

Modeling the univariate distribution function

The parameters of a normal distribution model were determined, yielding a mean and a standard deviation of 118.24 [g m−2] and 49.00 [g m−2] associated with Great Plains grassland (blue curve in Fig. 2a); a mean and a standard deviation of 174.12 [g m−2] and 64.32 [g m−2] associated with Chihuahuan Desert grassland (black curve in Fig. 2b); and a mean and a standard deviation of 187.06 [g m−2] and 52.84 [g m−2] associated with Chihuahuan Desert shrubland (green curve in Fig. 2c). For all three ecosystems, the parameters (i.e., mean and standard deviation) of the normal distribution models for individual subsets varied, as represented by the light blue, gray, and light green curves in Fig. 2a, b, c, and Figures S1, S2, and S3. For the Great Plains grassland, the differences or errors in the mean parameter ranged from 0.12 [g m−2] to 34.32 [g m−2], while those in the standard deviation parameter ranged from 0.09 [g m−2] to 4.84 [g m−2]. For the Chihuahuan Desert grassland, the differences or errors in the mean parameter ranged from 4.50 [g m−2] to 49.14 [g m−2], while those in the standard deviation parameter ranged from 0.05 [g m−2] to 63.48 [g m−2]. For the Chihuahuan Desert shrubland, the differences or errors in the mean parameter varied from 0.12 [g m−2] to 50.38 [g m−2], while those in the standard deviation parameter ranged from 0.06 [g m−2] to 38.40 [g m−2].

Fig. 2.

Evolution of normal probability distributions fitted to aboveground net primary production (ANPP, g m⁻2) for a Great Plains grassland (2002–2022), b Chihuahuan Desert grassland (1999–2022), and c Chihuahuan Desert shrubland (1999–2022). Light-colored curves show how distributions shift as additional years of data are incorporated (every fifth year labeled). Dark curves represent the distribution using the full dataset, illustrating how long-term records stabilize parameter estimates compared to shorter records

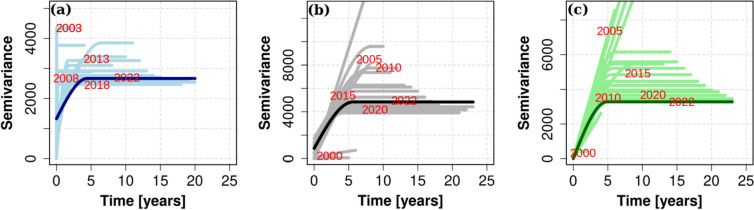

Modeling the temporal semivariogram function

The parameters from a spherical semivariogram model were determined, yielding a nugget, sill, and correlation range of 1328.90, 1339.33, and 4.44 [years] for the Great Plains grassland (blue curve in Fig. 3a); 868.02, 3967.14, and 5.59 [years] for the Chihuahuan Desert grassland (black curve in Fig. 3b); and 0, 3277.94, and 4.87 [years] for the Chihuahuan Desert shrubland (green curve in Fig. 3c). For all three ecosystems, the parameters (i.e., nugget, sill, and correlation range) of the spherical semivariogram models for individual subsets varied, as represented by the light blue, gray, and light green curves in Fig. 3a, b, c, and Figures S4, S5, and S6. For the Great Plains grassland, the differences or errors in the nugget parameter ranged from 102.73 to 1328.90, in the sill parameter from 468.03 to 3008.93, and in the correlation range parameter from 0.18 [years] to 4.44 [years]. For the Chihuahuan Desert grassland, the differences or errors in the nugget parameter ranged from 0.57 to 868.02, in the sill parameter from 352.91 to 3.43 106, and in the correlation range parameter from 0.24 [years] to 2729.55 [years]. For the Chihuahuan Desert shrubland, the differences or errors in the nugget parameter ranged from 0.00 to 0.38, in the sill parameter ranged from 82.91 to 2.91 106, and in the correlation range parameter from 0.06 [years] to 4869.93 [years].

Fig. 3.

Evolution of temporal semivariogram models of aboveground net primary production (ANPP, g m⁻2) for a Chihuahuan Desert grassland (1999–2022), b Great Plains grassland (2002–2022), and c Chihuahuan Desert shrubland (1999–2022). Light-colored curves show semivariograms recalculated as additional years of data are incorporated (every fifth year labeled), while dark curves represent the model using the full dataset. The shifting positions of the light curves relative to the dark curve indicate that estimates of temporal dependence (nugget, sill, and range) remain unstable, emphasizing the need for continued long-term monitoring

Modeling the dependency function between variables

For the Great Plains grassland, the best-fitting copula model was the Clayton copula, defined by the copula parameter of 1.60 and Kendall’s tau of 0.44 (blue curve in Fig. 4a). For the Chihuahuan Desert grassland, the best-fitting parametric copula model was the Frank copula, characterized by a copula parameter of 2.94 and Kendall’s tau of 0.30 (black curve in Fig. 4b). For the Chihuahuan Desert shrubland, the best-fitting copula model was the Survival Gumbel copula with the copula parameter of 1.45 and Kendall’s tau of 0.31 (green curve in Fig. 4c). For all three ecosystems, the parameters (i.e., copula parameter and Kendall’s tau) of the copula models for individual subsets varied, as represented by the light blue, gray, and light green curves in Figures S7, S8, and S9. For the Great Plains grassland, the differences or errors in the copula parameter ranged from 0.33 to 11.36, while those in Kendall’s tau parameter ranged from 0.05 to 0.42. For the Chihuahuan Desert grassland, the differences or errors in the copula parameter ranged from 0.06 to 3.88, while those in Kendall’s tau parameter ranged from 0.01 to 0.40. For the Chihuahuan Desert shrubland, the differences or errors in the copula parameter varied from 0.01 to 15.55, while those in Kendall’s tau parameter ranged from 0.00 to 0.63.

Fig. 4.

Best-fitted parametric copula functions between annual precipitation and aboveground net primary production (ANPP, g m⁻2) using all available years of data for a Chihuahuan Desert grassland (1999–2022), b Great Plains grassland (2002–2022), and c Chihuahuan Desert shrubland (1999–2022). A copula is a statistical function that characterizes the dependence structure between variables independently of their marginal distributions. Contour lines show levels of the copula function, with denser contours indicating stronger joint probability density (i.e., greater co-occurrence of precipitation and ANPP values). These plots highlight ecosystem-specific differences in the form and strength of precipitation–ANPP dependence. Supplementary Figures S7–S9 show the evolution of copula functions as data are incrementally incorporated. Fn(Precipitation) and Fn(ANPP) represent empirical cumulative distribution functions

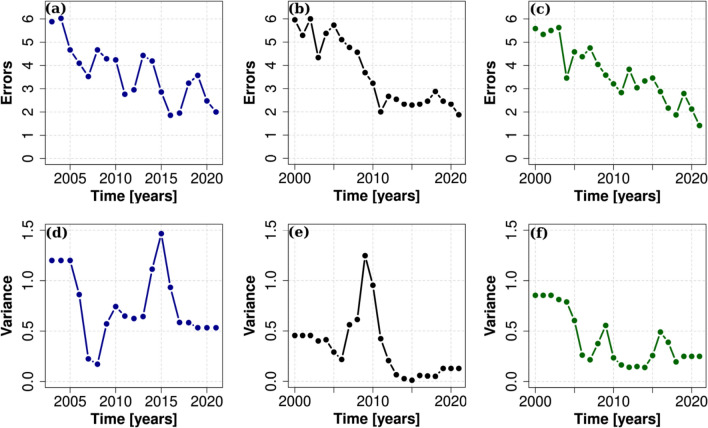

Calculating the combined modeling error

Across all three ecosystems, the overall modeling errors tended to decrease at different rates (Figs. 5a, b, c, and Figures S10–15). However, there were instances where the error initially decreased and then increased again with the addition of more data throughout the years. These behaviors were also observed in the corresponding moving variances of the errors over time (Fig. 5d, e, f). Finally, for each of the three ecosystems, the combined modeling errors did not reach zero or remain around zero over time (Fig. 5a, b, c). The overall modeling error for the Great Plains grassland ranged from 1.86 to 6.02, while the corresponding moving variances ranged from 0.17 to 1.47. For the Chihuahuan Desert grassland, the overall modeling error ranged from 1.88 to 6.00, while the corresponding moving variances ranged from 0.01 to 1.25. Finally, the overall modeling error for the Chihuahuan Desert shrubland varied from 1.42 to 5.63, while the corresponding moving variances ranged from 0.14 to 0.85 (Fig. 5a, b, c).

Fig. 5.

Evolution of overall modeling errors (a–c) and associated 5-year running variance (d–f) for a, d Chihuahuan Desert grassland (1999–2022), b, e Great Plains grassland (2002–2022), and c, f Chihuahuan Desert shrubland (1999–2022). Modeling errors quantify deviations in fitting probability distributions, semivariogram functions, and copula-based dependence between annual precipitation and ANPP. The 5-year running variance illustrates temporal fluctuations in these errors. Persistent variability and the absence of convergence toward zero emphasize the need for continued long-term observations

Discussion

This study quantitatively explores the rarely evaluated question of how the cumulative value of long-term information provides insights into deciding whether a long-term ecological study could or should be stopped. Here, we applied geostatistical methods to analyze the evolution of temporal variability in characteristic functions, such as univariate probability distribution functions (representing univariate statistical behavior), semivariogram functions (representing temporal dependence), and copula functions (describing patterns of dependence between variables) in a long-term study of aboveground net primary production (ANPP) across a dryland transition zone. Our results demonstrate the potential of using geostatistical methods to model ANPP and provide evidence supporting the importance and complexity of long-term ecological research. This approach could be implemented to test the complexity and value of long-term datasets and provide quantitative evidence in support of continuing (or ending) a long-term ecological study. In this case, our approach supports the idea that long-term measurements must continue at this study site based on evaluating parameter variability in the univariate distribution model, the temporal semivariogram model, and the copula model. Here, we discuss how our results support this conclusion.

First, the evaluation of parameter variability (i.e., mean and standard deviation) over time in the univariate distribution function modeling of ANPP for the three ecosystems revealed a decreasing trend with varying fluctuating rates; however, no stable or constant global minimum around zero was achieved for any of the long-term datasets. We highlight that the mean and standard deviation are sensitive to outliers resulting from ANPP in abnormal years (e.g., very wet or dry years). The fluctuations observed in the mean and standard deviation within the above temporal ranges suggest that external drivers, including climate variability, land management practices, and ecological disturbances, influence the distributions of ANPP at different temporal scales (Guo et al. 2012; Bradford et al. 2006; Busso et al. 2016; Haber et al. 2020). The relatively weak relationship between PPT and ANPP over time is consistent with many studies on climate variability and primary production (Sala et al. 2012), which show that slopes are smaller and temporal variability is greater than that of spatial patterns (Huxman et al. 2004; Maurer et al. 2020). This temporal variability underscores the importance of continuous measurements for accurately modeling the probability distribution of ANPP, which in turn improves forecasts of future ANPP trends and ultimately provides valuable insights into ecosystem health and resilience (Zinnert et al. 2021).

Secondly, our analysis also reveals that the parameters of the temporal semivariogram model (i.e., nugget, sill, and range) generally exhibit a declining trend over time, with fluctuations observed in all three ecosystems. However, the absence of a global minimum close to zero and oscillating around zero over the years (Figures S13, S14, S15) implies that long-term data acquisition is required to improve the strength of modeling the temporal dependence in ANPP. Notably, the semivariogram model and its parameters are also sensitive to outliers and complex temporal variability. These results add to the discussion that the ecological processes governing ANPP in drylands are highly dynamic and likely influenced by complex species interactions, lag effects, resource availability, other climate variables (e.g., VPD), extreme events, and land-use change (Smith 2011; Pachavo and Murwira 2014; Zinnert et al. 2021; Brown and Collins 2024; Wright and Collins 2024; Wang and Collins 2024; Collins et al. 2025).

Thirdly, the parameters of the copula model, which reflect the dependency relationship between annual precipitation and ANPP, decline but fluctuate without showing a stable global minimum of around zero (Figures S13, S14, S15). This indicates that dependency patterns between these variables remain highly variable over time (Thomey et al. 2011), supporting the conclusion that measurements should be continued. Notice that the copula model and its parameters are variable, which may connote non-linear and complex dependence between these variables, extreme events or outliers, and temporal heterogeneity. In this regard, the findings reveal that precipitation-ANPP relations can be nonlinear and complex (Hsu et al. 2012; Knapp et al. 2017; Collins et al. 2025), and relationships can change as species composition changes under climate change, or any other external factors (Smith et al. 2009; Parton et al. 2012; Avolio et al. 2021). Such results underscore the complexity and dynamics of ecological interactions, suggesting dependencies that must be considered within ecosystem models for more accurate forecasts of ecosystem responses to changing environmental conditions (Zinnert et al. 2021; Wang and Collins 2024; Feldman et al. 2024; Knapp et al. 2024).

Our findings emphasize that while increasing data availability often reduces errors and uncertainties in modeling, the quest for a stable global minimum close to zero for all parameters (represented by the overall modeling error and its running variance) remains elusive (Fig. 5). This high variability underscores the need for long-term monitoring programs that are better positioned to capture the full range of temporal variations and interactions in these ecosystems. Results from this study show non-linear trends in prediction capacity as more data are included, demonstrating emergent unexpected responses not evident in short-term observations.

Our results indicate that the minimum duration of data collection necessary to achieve relatively small errors and low uncertainty is 16, 17, and 20 years for the Chihuahuan Desert grassland, Great Plains grassland, and Chihuahuan Desert shrubland, respectively (Fig. 5). In drylands, strong interannual variability and intermittency of precipitation, together with scale‑dependent and frequently non‑linear precipitation–productivity relationships, further increase the record length needed to characterize dynamics reliably (Wang and Collins 2024). Shorter records yield useful insights but are prone to underestimating variability and uncertainty and can misrepresent the functional form of precipitation–ANPP relationships. Consequently, such shorter-term studies should be interpreted with caution, as they might miss critical long-term dynamics that only become apparent with extended records of data.

Here, we provide a quantitative framework to offer insights into whether a long-term study should be continued. We recognize that where and when to sample represents an important but controversial topic in ecology (Hutchinson 1953; Vargas and Le 2023). Our framework tests the concept of “data saturation” by evaluating whether additional measurements yield diminishing returns or if new insights are provided by additional information, supporting the continuation of measurements. However, other factors must be considered to determine when a long-term study should be discontinued. Achievement of the study’s initial objectives is paramount, as researchers must determine whether the initial research questions have been answered and the goals met (Likens and Lindenmayer 2018). Even so, long-term measurements increase in value to address many questions, some of which may not have been part of the original study design. Changing environmental conditions (e.g., extreme events, press events) or anthropogenic factors (e.g., management practices) can impact the study's relevance, feasibility, or focus over time. In these cases, redesign, termination, or a new justification for continuing a long-term research must be considered (Nichols and Williams 2006). Embracing technological advances, including new methods and technologies may offer insights into terminating obsolete long-term monitoring efforts or modifying and adapting them to expand capabilities and ensure relevance (Allen et al. 2007; Torresan et al. 2021). Integrating new technologies might require changes in methods, but innovations can complement historical data, provide finer-scale observations, and enable the detection of patterns and processes that were previously inaccessible or unobservable (Lechner et al. 2020; Lahoz-Monfort and Magrath 2021; Van Klink et al. 2022). Lastly, resource allocation is critical, as funding, personnel, and equipment may be limited; therefore, advocacy and evaluation of investment returns are needed to support the continued relevance of long-term ecological studies.

Conclusion

Here, we present a study of three dryland ecosystems, highlighting the importance of long-term monitoring and the application of geostatistical methods to understand temporal dynamics in ANPP in response to interannual variation in precipitation. By systematically modeling probability distributions, temporal semivariograms, and copula-based dependency functions, we show that short-term datasets are less proficient in predicting ANPP responses than longer-term datasets due to their enhanced capability to capture natural variability. However, long-term information revealed non-stationary responses that made prediction challenging even with more than 20 years of data at this grassland-to-shrubland transition zone.

Our findings demonstrate the importance of continuous, long-term observations in capturing the variability of ecosystem processes (i.e., ANPP) and dependencies that control their resilience and response to environmental change. These insights are crucial for refining ecosystem models and implementing adaptive management practices, while informing policy decisions in the context of rapid climate and land-use changes. As Heraclitus famously observed, change is the only constant in nature; therefore, long-term ecological studies hold substantial, often underappreciated value in advancing knowledge to support adaptive management and the protection of environmental resources.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We thank the staff of the Sevilleta National Wildlife Refuge for permission to conduct long-term research. We thank the Sevilleta LTER Information Manager and Field Crew for ANPP data collection and curation.

Author contribution statement

VHL, RV, and SLC conceived and designed the study. VHL analyzed data, made figures, and wrote the manuscript with input from RV and SCL.

Funding

This study was supported by multiple grants to the University of New Mexico for Long-term Ecological Research, most recently DEB-1655499. SLC was supported by a Long-term Research in Environmental Biology Award DEB-2423861.

Data availability

Data are publicly available at: Baur, L., S. Collins, E. Muldavin, J.A. Rudgers, and W.T. Pockman. 2024. Core Research Site Web Seasonal Biomass and Seasonal and Annual NPP Data for the Net Primary Production Study at the Sevilleta National Wildlife Refuge, New Mexico ver 244948. Environmental Data Initiative. 10.6073/pasta/57790b2a8c9271d18a505abf6e3854ef (Accessed 2024-11-04).

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Allen MF, Vargas R, Graham EA, Swenson W, Hamilton M, Taggart M et al (2007) Soil sensor technology: life within a pixel. Bioscience 57(10):859–867 [Google Scholar]

- Avolio ML, Komatsu KJ, Collins SL, Grman E, Koerner SE, Tredennick AT et al (2021) Determinants of community compositional change are equally affected by global change. Ecol Lett 24(9):1892–1904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford JB, Lauenroth WK, Burke IC, Paruelo JM (2006) The influence of climate, soils, weather, and land use on primary production and biomass seasonality in the US Great Plains. Ecosystems 9:934–950 [Google Scholar]

- Brown RF, Collins SL (2023) As above, not so below: long-term dynamics of net primary production across a dryland transition zone. Glob Change Biol 29(14):3941–3953 [Google Scholar]

- Brown RF, Collins SL (2024) Revisiting the bucket model: Long-term effects of rainfall variability and nitrogen enrichment on net primary production in a desert grassland. J Ecol 112(3):629–641 [Google Scholar]

- Busso CA, Montenegro OA, Torres YA, Giorgetti HD, Rodriguez GD (2016) Aboveground net primary productivity and cover of vegetation exposed to various disturbances in arid Argentina. Appl Ecol Environ Res 14(3):51–75 [Google Scholar]

- Callahan JT (1984) Long-term ecological research. Bioscience 34(6):363–367 [Google Scholar]

- Collins SL, Patton MT, Brown RF (2025) Precipitation-productivity relationships in desert grassland: a test of the double asymmetry hypothesis. Ecology 106(8):e70166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Díaz-Viera MA, Hernández-Maldonado V, Méndez-Venegas J, Mendoza-Torres F, Le VH, Vázquez-Ramírez D (2021) RGEOESTAD: Un programa de código abierto para aplicaciones geoestadísticas basado en R-Project

- Feldman AF, Feng X, Felton AJ, Konings AG, Knapp AK, Biederman JA et al (2024) Plant responses to changing rainfall frequency and intensity. Nat Rev Earth Environ 1–19

- Felton AJ, Knapp AK, Smith MD (2021) Precipitation–productivity relationships and the duration of precipitation anomalies: an underappreciated dimension of climate change. Glob Change Biol 27(6):1127–1140 [Google Scholar]

- Gosz JR (1993) Ecotone hierarchies. Ecol Appl 3(3):369–376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gosz RJ, Gosz JR (1996) Species interactions on the biome transition zone in New Mexico: response of blue grama (Bouteloua gracilis) and black grama (Bouteloua eripoda) to fire and herbivory. J Arid Environ 34(1):101–114 [Google Scholar]

- Guera OGM, Castrejón-Ayala F, Robledo N, Jiménez-Pérez A, Le VH, Díaz-Viera MA et al (2023) Geostatistical analysis of fall armyworm damage and edaphoclimatic conditions of a mosaic of agroecosystems predominated by push-pull systems. Chilean J Agric Res 83(1):14–30 [Google Scholar]

- Guo Q, Hu Z, Li S, Li X, Sun X, Yu G (2012) Spatial variations in aboveground net primary productivity along a climate gradient in Eurasian temperate grassland: effects of mean annual precipitation and its seasonal distribution. Glob Change Biol 18(12):3624–3631 [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez F, Gallego F, Paruelo JM, Rodríguez C (2020) Damping and lag effects of precipitation variability across trophic levels in Uruguayan rangelands. Agric Syst 185:102956 [Google Scholar]

- Haber LT, Fahey RT, Wales SB, Correa Pascuas N, Currie WS, Hardiman BS et al (2020) Forest structure, diversity, and primary production in relation to disturbance severity. Ecol Evol 10(10):4419–4430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heisler-White JL, Blair JM, Kelly EF, Harmoney K, Knapp AK (2009) Contingent productivity responses to more extreme rainfall regimes across a grassland biome. Glob Change Biol 15(12):2894–2904 [Google Scholar]

- Hobbie JE, Carpenter SR, Grimm NB, Gosz JR, Seastedt TR (2003) The US long term ecological research program. Bioscience 53(1):21–32 [Google Scholar]

- Hsu JS, Powell J, Adler PB (2012) Sensitivity of mean annual primary production to precipitation. Glob Change Biol 18(7):2246–2255 [Google Scholar]

- Huang J, Li Y, Fu C, Chen F, Fu Q, Dai A et al (2017) Dryland climate change: recent progress and challenges. Rev Geophys 55(3):719–778 [Google Scholar]

- Hughes BB, Beas-Luna R, Barner AK, Brewitt K, Brumbaugh DR, Cerny-Chipman EB et al (2017) Long-term studies contribute disproportionately to ecology and policy. Bioscience 67(3):271–281 [Google Scholar]

- Hutchinson GE (1953) The concept of pattern in ecology. Proc Acad Natl Sci Phila 105:1–12 [Google Scholar]

- Huxman TE, Smith MD, Fay PA, Knapp AK, Shaw MR, Loik ME et al (2004) Convergence across biomes to a common rain-use efficiency. Nature 429(6992):651–654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keenan RJ (2015) Climate change impacts and adaptation in forest management: a review. Ann for Sci 72:145–167 [Google Scholar]

- Knapp AK, Ciais P, Smith MD (2017) Reconciling inconsistencies in precipitation–productivity relationships: implications for climate change. New Phytol 214(1):41–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knapp AK, Condon KV, Folks CC, Sturchio MA, Griffin-Nolan RJ, Kannenberg SA et al (2024) Field experiments have enhanced our understanding of drought impacts on terrestrial ecosystems—but where do we go from here? Funct Ecol 38(1):76–97 [Google Scholar]

- Komatsu KJ, Avolio ML, Lemoine NP, Isbell F, Grman E, Houseman GR et al (2019) Global change effects on plant communities are magnified by time and the number of global change factors imposed. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 116(36):17867–17873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuebbing SE, Reimer AP, Rosenthal SA, Feinberg G, Leiserowitz A, Lau JA et al (2018) Long-term research in ecology and evolution: a survey of challenges and opportunities. Ecol Monogr 88(2):245–258 [Google Scholar]

- Lahoz-Monfort JJ, Magrath MJ (2021) A comprehensive overview of technologies for species and habitat monitoring and conservation. Bioscience 71(10):1038–1062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le VH, Díaz-Viera MA, Vázquez-Ramírez D, del Valle-García R, Erdely A, Grana D (2020) Bernstein copula-based spatial cosimulation for petrophysical property prediction conditioned to elastic attributes. J Pet Sci Eng 193:107382 [Google Scholar]

- Le VH (2021) Copula-based modeling for petrophysical property prediction using seismic attributes as secondary variables. PhD dissertation, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Mexico City, Mexico

- Le VH, Vargas R (2023) Beyond a deterministic representation of the temperature dependence of soil respiration. Sci Total Environ 912:169391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le VH, Vargas R (2024) An autocorrelated conditioned Latin hypercube method for temporal or spatial sampling and predictions. Comput Geosci 184:105539 [Google Scholar]

- Lechner AM, Foody GM, Boyd DS (2020) Applications in remote sensing to forest ecology and management. One Earth 2(5):405–412 [Google Scholar]

- Lindenmayer DB, Likens GE, Andersen A, Bowman D, Bull CM, Burns E et al (2012) Value of long-term ecological studies. Austral Ecol 37(7):745–757 [Google Scholar]

- Likens GE, Driscoll CT, Buso DC (1996) Long-term effects of acid rain: response and recovery of a forest ecosystem. Science 272(5259):244–246 [Google Scholar]

- Likens G, Lindenmayer D (2018) Effective ecological monitoring. CSIRO publishing, pp 4–12 [Google Scholar]

- Magurran AE, McGill BJ (eds) (2010) Biological diversity: frontiers in measurement and assessment. OUP Oxford, pp 85–93 [Google Scholar]

- Magurran AE, Baillie SR, Buckland ST, Dick JM, Elston DA, Scott EM et al (2010) Long-term datasets in biodiversity research and monitoring: assessing change in ecological communities through time. Trends Ecol Evol 25(10):574–582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maurer GE, Hallmark AJ, Brown RF, Sala OE, Collins SL (2020) Sensitivity of primary production to precipitation across the United States. Ecol Lett 23(3):527–536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muldavin EH, Moore DI, Collins SL, Wetherill KR, Lightfoot DC (2008) Aboveground net primary production dynamics in a northern Chihuahuan Desert ecosystem. Oecologia 155:123–132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagler T, Schepsmeier U, Stoeber J, Brechmann E, Graeler B, Erhardt T (2023) VineCopula: Statistical Inference of Vine Copulas. R package version 2.5.0

- Nichols JD, Williams BK (2006) Monitoring for conservation. Trends Ecol Evol 21(12):668–673 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pachavo G, Murwira A (2014) Land-use and land tenure explain spatial and temporal patterns in terrestrial net primary productivity (NPP) in southern Africa. Geocarto Int 29(6):671–687 [Google Scholar]

- Parmesan C, Yohe G (2003) A globally coherent fingerprint of climate change impacts across natural systems. Nature 421(6918):37–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parton W, Morgan J, Smith D, Del Grosso S, Prihodko L, LeCain D et al (2012) Impact of precipitation dynamics on net ecosystem productivity. Glob Change Biol 18(3):915–927 [Google Scholar]

- Peters MK, Hemp A, Appelhans T, Becker JN, Behler C, Classen A et al (2019) Climate–land-use interactions shape tropical mountain biodiversity and ecosystem functions. Nature 568(7750):88–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poulter B, Frank D, Ciais P, Myneni RB, Andela N, Bi J et al (2014) Contribution of semi-arid ecosystems to interannual variability of the global carbon cycle. Nature 509(7502):600–603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team (2022) R: A language and environment for statistical computing. In: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria

- Rastetter EB, Ohman MD, Elliott KJ, Rehage JS, Rivera-Monroy VH, Boucek RE et al (2021) Time lags: insights from the US long term ecological research network. Ecosphere 12(5):e03431 [Google Scholar]

- Ratajczak Z, Collins SL, Blair JM, Koerner SE, Louthan AM, Smith MD et al (2022) Reintroducing bison results in long-running and resilient increases in grassland diversity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 119(36):e2210433119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rees M, Condit R, Crawley M, Pacala S, Tilman D (2001) Long-term studies of vegetation dynamics. Science 293(5530):650–655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro PJ Jr, Diggle PJ, Christensen O, Schlather M, Bivand R, Ripley B et al (2020) Package ‘geoR.’ R Package Version 1(8):1 [Google Scholar]

- Rudgers JA, Chung YA, Maurer GE, Moore DI, Muldavin EH, Litvak ME et al (2018) Climate sensitivity functions and net primary production: a framework for incorporating climate mean and variability. Ecology 99(3):576–582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudgers JA, Hallmark A, Baker SR, Baur L, Hall KM, Litvak ME et al (2019) Sensitivity of dryland plant allometry to climate. Funct Ecol 33(12):2290–2303 [Google Scholar]

- Sala OE, Biondini ME, Lauenroth WK (1988) Bias in estimates of primary production: an analytical solution. Ecol Modell 44(1–2):43–55 [Google Scholar]

- Sala OE, Gherardi LA, Reichmann L, Jobbágy E, Peters D (2012) Legacies of precipitation fluctuations on primary production: theory and data synthesis. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 367(1606):3135–3144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seabloom EW, Adler PB, Alberti J, Biederman L, Buckley YM, Cadotte MW et al (2021) Increasing effects of chronic nutrient enrichment on plant diversity loss and ecosystem productivity over time. Ecology 102(2):e03218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith MD (2011) An ecological perspective on extreme climatic events: a synthetic definition and framework to guide future research. J Ecol 99(3):656–663 [Google Scholar]

- Smith MD, Knapp AK, Collins SL (2009) A framework for assessing ecosystem dynamics in response to chronic resource alterations induced by global change. Ecology 90(12):3279–3289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan TJ, Driscoll CT, Beier CM, Burtraw D, Fernandez IJ, Galloway JN et al (2018) Air pollution success stories in the United States: the value of long-term observations. Environ Sci Policy 84:69–73 [Google Scholar]

- Tetzlaff D, Carey SK, McNamara JP, Laudon H, Soulsby C (2017) The essential value of long-term experimental data for hydrology and water management. Water Resour Res 53(4):2598–2604 [Google Scholar]

- Thomey ML, Collins SL, Vargas R, Johnson JE, Brown RF, Natvig DO et al (2011) Effect of precipitation variability on net primary production and soil respiration in a Chihuahuan Desert grassland. Glob Change Biol 17(4):1505–1515 [Google Scholar]

- Torresan C, Benito Garzón M, O’grady M, Robson TM, Picchi G, Panzacchi P et al (2021) A new generation of sensors and monitoring tools to support climate-smart forestry practices. Can J for Res 51(12):1751–1765 [Google Scholar]

- Van Klink R, August T, Bas Y, Bodesheim P, Bonn A, Fossøy F et al (2022) Emerging technologies revolutionise insect ecology and monitoring. Trends Ecol Evol 37(10):872–885 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vargas R, Le VH (2023) The paradox of assessing greenhouse gases from soils for nature-based solutions. Biogeosci Discuss 2022:1–44 [Google Scholar]

- Vázquez-Ramírez D, Le VH, Díaz-Viera MA, del Valle-García R, Erdely A (2023) Joint stochastic simulation of petrophysical properties with elastic attributes based on parametric copula models. Geofis Int 62(2):487–506 [Google Scholar]

- Venables WN, Ripley BD (2002) Modern Applied Statistics with S, Fourth edition. Springer, New York. ISBN 0-387-95457-0

- Vucetich JA, Nelson MP, Bruskotter JT (2020) What drives declining support for long-term ecological research? Bioscience 70(2):168–173 [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Collins SL (2024) The complex relationship between precipitation and productivity in drylands. Cambr Prisms Drylands 1:e1 [Google Scholar]

- Wright AJ, Collins SL (2024) Drought experiments need to incorporate atmospheric drying to better simulate climate change. Bioscience 74(1):65–71 [Google Scholar]

- Wu B, Smith WK, Zeng H (2024) Dryland dynamics and driving forces. Dryland social-ecological systems in changing environments. Springer Nature Singapore, Singapore, pp 23–68 [Google Scholar]

- Zapata-Norberto B, Morales-Casique E, Le VH, Díaz-Viera M (2024) Effect of cross-correlated hydraulic conductivity and compression index on nonlinear consolidation in randomly heterogeneous highly compressible aquitards. J South Am Earth Sci 147:105109 [Google Scholar]

- Zinnert JC, Nippert JB, Rudgers JA, Pennings SC, González G, Alber M et al (2021) State changes: insights from the US long term ecological research network. Ecosphere 12(5):e03433 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data are publicly available at: Baur, L., S. Collins, E. Muldavin, J.A. Rudgers, and W.T. Pockman. 2024. Core Research Site Web Seasonal Biomass and Seasonal and Annual NPP Data for the Net Primary Production Study at the Sevilleta National Wildlife Refuge, New Mexico ver 244948. Environmental Data Initiative. 10.6073/pasta/57790b2a8c9271d18a505abf6e3854ef (Accessed 2024-11-04).