Abstract

The sensing of Gram-negative Extracellular Vesicles (EVs) by the innate immune system has been extensively studied in the past decade. In contrast, recognition of Gram-positive EVs by innate immune cells remains poorly understood. Comparative genome-wide transcriptional analysis in human monocytes uncovered that S. pyogenes EVs induce proinflammatory signatures that are markedly distinct from those of their parental cells. Among the 209 genes exclusively upregulated by EVs, caspase-5 prompted us to study inflammasome signaling pathways in depth. We show that lipoteichoic acid (LTA), a structural component of Gram-positive bacterial membranes present on EVs from S. pyogenes and other Gram-positive species, is sensed by TLR2 which triggers the alternative inflammasome composed of NLRP3 and the inflammatory caspases-4/-5 to mount an IL-1β response without inducing cell death. For S. pyogenes, we identify TLR8 as a sensor to mediate caspase-4/-5-dependent IL-1β secretion. Notably, inflammasome activation by intact bacteria is independent of the global virulence regulator CovS in monocytes. Overall, our study highlights a new role for TLR2 and caspase-4/-5 in the recognition of Gram-positive EVs in human monocytes.

Keywords: Streptococcus pyogenes, Monocytes, Extracellular Vesicles, Caspases, Inflammasome

Subject terms: Immunology; Membranes & Trafficking; Microbiology, Virology & Host Pathogen Interaction

Synopsis

The recognition of Gram-positive EVs by innate immune cells remains poorly understood. This study identifies alternative inflammasome activation by S. pyogenes and Gram-positive EVs in human monocytes and highlights a new role for TLR2 and caspase-4/-5 in this process.

Lipoteichoic acid (LTA) as a constituent of Gram-positive EVs activates the alternative inflammasome via TLR2.

IL-1β secretion is regulated by MYD88, RIPK1, CASP8, and CASP4/5.

EVs promote monocyte survival by inhibiting caspase-3 activation.

The recognition of Gram-positive EVs by innate immune cells remains poorly understood. This study identifies alternative inflammasome activation by S. pyogenes and Gram-positive EVs in human monocytes and highlights a new role for TLR2 and caspase-4/-5 in this process.

Introduction

Streptococcus pyogenes (S. pyogenes) is a strict human pathogen that causes superficial infections (e.g., impetigo) as well as life-threatening invasive disease (e.g., Streptococcal toxic shock syndrome), with a global burden of at least 500,000 deaths annually (Carapetis et al, 2005). S. pyogenes expresses a wide array of virulence components that facilitate its survival within the host by hijacking the activity of immune cells (Graham et al, 2002; Tsatsaronis et al, 2014; Hynes and Sloan, 2016). Factors associated with bacterial virulence can be classified according to their location: membrane-bound, membrane-anchored, or cytosolic. Interestingly, several virulence mediators present in S. pyogenes extracellular vesicles (Spy EVs) do not possess a secretion signal peptide and are therefore not secreted through the canonical bacterial secretory pathway (Sec) (Lei et al, 2000; Resch et al, 2016). Since no alternative secretion mechanism has been identified in S. pyogenes, it is likely that EVs contribute to the release of components that cannot be secreted by the Sec pathway (Resch et al, 2016).

EVs are nanoparticles consisting of a lipid bilayer shell encapsulating proteins and nucleic acids derived from their parental cells. The release of EVs is conserved across all domains of life to coordinate intra- and interspecies communication via cellular components (Deatheragea et al, 2012; Yoon et al, 2014; Woith et al, 2019). In Gram-negative bacteria, the composition, biogenesis, and functions of outer membrane vesicles (OMVs) in bacterial physiology have been extensively characterized (Schwechheimer and Kuehn, 2015; Orench-Rivera and Kuehn, 2016). Numerous reports have addressed the intricate communication process that occurs between the host and OMVs of pathogens or microbiota species (Kaparakis-Liaskos and Ferrero, 2015; Ñahui Palomino et al, 2021). Similarly, over the last few decades, numerous studies have demonstrated that Gram-positive model organisms and pathogens also release EVs (Lee et al, 2009; Rivera et al, 2010; Brown et al, 2015). However, only a few of these studies have addressed the impact of Gram-positive EVs on the host (Gurung et al, 2011; Olaya-Abril et al, 2014; Wang et al, 2020).

Previously, our laboratory and others have shown that Spy EVs encapsulate virulence factors, highlighting their potential role in modulating the host-pathogen interface (Biagini et al, 2015; Resch et al, 2016; Uhlmann et al, 2016; Murase et al, 2021). Several groups have reported that enrichment and exclusion of bacterial components in EVs, a process termed cargo selectivity, commonly occurs (Haurat et al, 2011; Elhenawy et al, 2014; Veith et al, 2014). For example, Spy EVs are enriched in the Streptococcal inhibitor of the complement (Sic) and Streptolysin O (SLO) compared to their parental cells (Resch et al, 2016), which are components that have been associated with pathogenicity and virulence (Harder et al, 2009; Pence et al, 2010; Nasser et al, 2014). Due to their small size and resistance to degradation, bacterial EVs are able to diffuse and travel long distances in the human body, reaching locations that their parental cells might not access (Tulkens et al, 2020). In addition, microbial EVs can be internalized and/or recognized through pathogen recognition receptors (PRRs), which may differ from the PRRs participating in the recognition of their parental cells (Vanaja et al, 2016).

The delivery of Gram-negative bacterial components including lipopolysaccharide (LPS) to the cytosol of host cells via OMVs has been shown to promote canonical as well as non-canonical inflammasome assembly, leading to caspase-1-dependent cleavage and subsequent release of the proinflammatory cytokines IL-1α, IL-1β, and IL-18 as well as the induction of pyroptotic cell death (Cecil et al, 2017; Finethy et al, 2017; Yang et al, 2020). Activation of this large multiprotein complex requires existing or de-novo synthetized inflammasome protein components and their signal-induced oligomerization: PRR-engagement on the cell surface stimulates NFκB-dependent gene expression of inactive precursor molecules for the cytokines (priming). Subsequently, the presence of bacterial products within the cytosol is sensed by various NOD-like receptors (NLRs) triggering oligomerization and recruitment of caspase-1 (activation). However, unlike macrophages, LPS has been shown to trigger an alternative one-step inflammasome activation pathway in human monocytes, which is dependent on TLR4 signaling and does not require LPS internalization or priming (Netea et al, 2009; Gaidt et al, 2016; Gritsenko et al, 2020). In addition to TLR4, a more recent study implicated multiple TLRs to activate the alternative inflammasome in human monocytes leading to IL-1β secretion, indicating that pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) other than LPS can be recognized by this pathway (Unterberger et al, 2023). However, to date, no publication reports activation of the alternative inflammasome in response to live, Gram-positive bacteria or their secreted EVs.

In the present study, we have comparatively examined the response of primary human monocytes to Spy EVs and their parental cells. Interestingly, although both stimuli induce a significant overlap in the monocyte’s response, we identified specific signatures triggered by either stimulus. We provide evidence, that Spy EVs are sensed by TLR2 on monocytes which triggers the alternative inflammasome comprised of NLRP3 and the inflammatory caspases-4 and -5, leading to the release of IL-1β without inducing cell death. We identify lipoteichoic acid (LTA), a structural component of Gram-positive bacterial membranes, present on EVs but also in EV-depleted culture supernatant, as the ligand for TLR2. Accordingly, EVs from other Gram-positive species stimulate caspase-4/-5-dependent IL-1β secretion, underlining the conservation of this mechanism. In contrast, inflammasome activation in response to infection with S. pyogenes requires TLR8 and is characterized by ASC speck formation and GSDMD-dependent pyroptotic cell death, indicating that distinct innate immune pathways are involved in IL-1β production in response to S. pyogenes or its EVs.

Results

Transcriptome analysis reveals a unique set of genes that are upregulated upon encounter with Spy EVs

Our laboratory has previously characterized the content of Spy EVs derived from the hypervirulent clinical isolate ISS3348 by proteomic, RNA sequencing, and lipidomic analysis (Resch et al, 2016). Spy EVs and their parental cells show an asymmetrical distribution in their composition (e.g., of virulence factors) (Resch et al, 2016), supporting the idea that EVs might trigger distinct responses than S. pyogenes cells. To characterize and compare the response of innate immune cells when encountering Spy EVs or intact bacteria, we performed RNA sequencing on human primary monocytes (Dataset EV1) and B-cell Leukemia C/EBPα Estrogen Receptor clone 1 (BLaER1)-derived monocytes (Dataset EV2) after incubation with Spy EVs or infection with S. pyogenes. Spy EV purification and physiochemical characterization is summarized in Fig. EV1A,B. EV-quantification on the basis of size and concentration was initially performed using Nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA) (Fig. EV1C) and confirmed by Tunable Resistive Pulse Sensing (TRPS), both methodologies proven to be more sensitive as compared to protein-content based quantification. To rule out any potential contamination of the Spy EVs with LPS, vesicle preparations were tested using the Pro-Q™ Emerald 300 lipopolysaccharide gel stain (Fig. EV1D) and mass spectrometry (Appendix Fig. S1). We did not detect any LPS in our EV preparations. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) was used to visualize the EVs (Fig. EV1E) as previously described (Resch et al, 2016). While there are no published reports showing quantitative data on the number of EVs released by a bacterium during an in vivo infection, we found that the ratio between S. pyogenes and its EVs in THB culture is ~20 (17.7) EVs per bacterial cell. To assess a suitable dose for Spy EVs, we challenged human monocytes with increasing particle-concentrations of EVs and measured IL-1β and IL-6 in cell culture supernatants at 18 h post-stimulation (Fig. EV1F). We observed an EV-particle-dose-dependent release of both cytokines, however, secretion of IL-1β was considerably lower than that of IL-6, which explains why a dose of 7 × 108 EVs (corresponding to 7000 EVs/cell) was defined for future experiments.

Figure EV1. Purification, quantification, and characterization of bacterial EVs used in this study.

(A) Schematic protocol of the purification strategy used for EVs. (B) Mean size (left) and concentration (right) of Spy EVs (n = 15) characterized by nanoparticle tracker analysis (NTA). (C) Linear correlation between particles/mL (measured by NTA) and the amount of protein of the same batches (Bradford assay, n = 15). (D) LPS analysis of EV preparations separated by SDS PAGE followed by Pro-Q Emerald 300 staining. Smooth LPS standard from E. coli serotype O55:B5 with characteristic ladder pattern was used as positive control. (E) Spy EV preparation imaged by transmission electron microscopy (TEM, scale bar: 1 µm). (F) IL-1β and IL-6 released by human monocytes stimulated with increasing amounts of Spy EVs for 18 h. Bars represent the mean ± SD of six biological replicates. P < 0.0001 (for all comparisons). Data information: (F) One-way ANOVA was applied with Holm–Šídák correction for multiple comparisons. ***P ≤ 0.001, n.s. not significant.

To obtain an unbiased view on the early (4 h) transcriptional response of monocytes to Spy EVs or infections with S. pyogenes, we performed RNA sequencing as outlined in Fig. 1A. Principle component analysis (PCA) showed that samples were clearly separated and clustered by treatment, indicating that donor variability had minor impact in our experimental setting (Fig. 1B).

Figure 1. S. pyogenes EVs induce a distinct expression profile in monocytes.

(A) Schematic summary of the study design. Primary monocytes were purified through density gradient followed by magnetic negative selection. Four hours after S. pyogenes infection or challenge with its EVs, RNA from monocytes was purified and processed for RNA sequencing. (B) Principal component analysis of gene transcription colored by treatment. (C) Scatterplot comparison of Log2 fold change (FC) (treatment vs untreated control, Unt) in transcript abundance for S. pyogenes-infected (x axis) or EV-treated samples (y axis). Dashed lines mark cut-off criteria of a log2 FC > |2|. Grey dots represent transcripts commonly regulated but with an FC < |2|. Blue dots denote commonly regulated transcripts with a FC ≥ |2|. Orange and purple dots indicate differentially expressed genes for either EVs or S. pyogenes, respectively. Dashed areas indicate four distinct gene groups which meet our cut-off criteria that share (2 and 4) or display unique (1 and 3) transcription patterns for both or either stimulus, respectively. Representative genes in each group are highlighted. Wald test was applied for statistical analyses. (D) Venn diagrams summarizing unique and overlapping up- or downregulated genes with FC ≥ |2|. The top three genes for each category are displayed. (E) Heatmap of twenty representative genes from each gene group in (D). Data information: (B–E) Data are representative of eight biological replicates. (C–E) Graphs include gene transcription after 4 h upon EV or S. pyogenes stimulation compared to untreated monocytes. Genes were defined as differentially regulated when FC ≥ |2| as compared to untreated cells and the adjusted P value was <0.01 after Benjamini-Hochberg correction for multiple comparisons.

Our transcriptomic datasets showed that 1107 and 445 genes are upregulated in response to both Spy EVs and bacterial cells in monocytes and BLaER1 cells, respectively (Figs. 1C,D and EV2A,B). Since primary monocytes respond more strongly than BLaER cells, we focused on our monocyte dataset for further analyses. Accordingly, pathway analysis of primary monocytes revealed that KEGG pathways and GO terms enriched for each treatment show a high similarity (Fig. EV2C,D). Among the commonly upregulated genes (Fig. 1C–E, group 2), we found cytokines (e.g., IL1A, IL1B and IL6), chemokines (e.g., CCL3, CCL4 and CXCL8) and growth factors (e.g., CSF3). In contrast, several immune receptors (e.g., TLR1, TLR6 and CCR2) and adhesion factors (e.g., PECAM1 and VCAN) were downregulated for both stimuli (Fig. 1C–E, group 4). We then analyzed the differentially expressed genes (DEGs) belonging specifically to one of the treatments. DEGs upon challenge with Spy EVs included the metalloreductase STEAP4, components of the Wnt signaling pathway (WNT5A), and, strikingly, the immune sensor CASP5 (Fig. 1C–E, group 1). Infection with S. pyogenes specifically upregulated an additional 1107 genes (Fig. 1C–E, group 3), including interferon and interferon-related genes (IRGs, e.g., IFNG, IFNB1 and CXCL10), growth factors (e.g., CSF1), and chemokines (e.g., CCL8), indicating that the sensing of whole bacteria induces responses remarkably distinct from those of EVs. Real-time quantitative PCR (RTqPCR) was used to validate representative candidates from each gene group (Fig. EV2E–H).

Figure EV2. RNA sequencing of monocytes: pathway analysis and RTqPCR of specific genes.

(A) Scatterplot comparison of Log2 fold change (FC) (treatment vs untreated control, Unt) in transcript abundance for S. pyogenes-infected (x-axis) or EV-treated samples (y-axis) in BLaER1 cells (related to Fig. 1). Grey dots represent transcripts commonly regulated but with an FC < | 2 | . Blue dots denote commonly regulated transcripts with a FC ≥ | 2 | . Orange and purple dots indicate differentially expressed genes for either Spy EVs or S. pyogenes, respectively. (B) Venn diagrams of differentially transcribed genes in BLaER1 cells after stimulation with Spy EVs or S. pyogenes for 4 h. Numbers indicate the total amount of genes for each category. (C, D) Top ten upregulated KEGG pathways (C) or GO terms (D) are shown for Spy EV-treated versus untreated monocytes and S. pyogenes-treated versus untreated monocytes. Solid lines indicate same pathway and dashed lines indicate a related pathway. (E–H) Quantitative real time PCR of selected genes. Floating bar plots displaying the negative ΔCt values of three biological replicates. The central line represents the mean, the borders represent the minimum and the maximum values. A dotted line indicates the mean expression of the housekeeping genes (GAPDH/TUBB). (E) Genes upregulated by Spy EV treatment. (WNT5A) P = 0.0029, P = 0.0004. (CASP5) P = 0.0028. (F) Genes upregulated by S. pyogenes and Spy EV treatments. (IL1A) P = 0.0003 (for both comparisons). (CCL4) P = 0.0014 (for both comparisons). (G) Genes upregulated by S. pyogenes treatment. (IFNG) P = 0.0025. (IFNB) P = 0.0308. (H) Genes downregulated for both S. pyogenes and Spy EV treatments. (CCR2) P = 0.0055 (Spy), P = 0.0010 (EVs). (PTGRFN) P = 0.0130 (for both comparisons). Data information: (E–H) One-way ANOVA with Holm–Šídák correction for multiple comparisons was applied for statistical analyses. *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, ***P ≤ 0.001, n.s. not significant.

Spy EVs induce a proinflammatory response

During S. pyogenes infection, inflammation facilitates bacterial clearance by innate immune cells but may also promote a potentially detrimental immune response. In mouse models, this balance is orchestrated by IL-1β and type I interferon signaling, which promote and repress inflammation, respectively (Castiglia et al, 2016). Accordingly, IL-1β inhibitors used to treat patients with autoimmune diseases increase the risk of developing invasive S. pyogenes infections by 330-fold, suggesting a central role for this cytokine in controlling S. pyogenes pathogenesis in humans (LaRock et al, 2016). Interestingly, while IL-1β and other members of the IL-1 cytokine family, such as IL-1α and IL-36γ, are upregulated by both S. pyogenes and its EVs, we observed expression of IFNβ, IFNγ, and IRGs (e.g., CXCL9, CXCL10, CXCL11) predominantly during bacterial infection (Dataset EV1; Figs. 1C,E and EV4G,H). Although RNA sequencing detected both IFNβ and -γ expression also in response to Spy EVs, they were only classified among the lowest 5% or 10% of the DEGs. In contrast, infection with S. pyogenes triggered a significantly higher expression of both cytokines, with IFNβ ranked among the lowest 50% and IFNγ among the highest 50% of the DEGs, indicating that only bacterial cells induce a robust IFN response in human monocytes.

Figure EV4. Cytokine controls and cell death of monocytes and BLaER1 cells: canonical inflammasome.

(A) IL-6 in supernatants from human monocytes either left untreated or preincubated with Ac-LEVD-CHO, MCC950, VX-765, or Ac-YVAD-CMK. Cells were then left unstimulated or challenged with S. pyogenes or its EVs for 18 h. Bars represent the mean ± SD of four biological replicates. P = 0.0011. (B, C) IL-6 released from BLaER1 WT, PYCARD KO (ASC−/−), NLRP3 KO clones 1 and 2 (NLRP3−/−), Caspase-1 KO clones 1 and 2 (CASP1−/−), and non-targeted control (NTC) cells stimulated with Spy EVs or infected with S. pyogenes for 18 h. Bars represent the mean ± SD of three biological replicates. (D) Box plot showing caspase and NLRP protein levels differentially expressed in BLaER1 cells (5 biological replicates) and primary human monocytes (4 biological replicates). Each dot represents the protein level of an individual sample. The boxplot displays the distribution of the data with the box representing the interquartile range (IQR) between the 25th (Q1) and 75th (Q3) percentiles. The line inside the box indicates the median (50th percentile). Whiskers extend to the smallest and largest values within 1.5 × IQR below Q1 and above Q3, respectively. Data points outside this range are shown individually as outliers. In total, 6472 proteins were quantified in at least 3 biological replicates of BLaER1 cells, and 6092 proteins were quantified in primary monocytes. (E) Immunoblots displaying GSDMD and IL-1β in human monocytes either left untreated or challenged with Spy EVs or S. pyogenes for 18 h. Representative of four biological replicates. Data information: (A–C) Two-way ANOVA with Holm–Šídák correction for multiple comparisons was applied for statistical analyses. **P ≤ 0.01, n.s. not significant.

Caspase-4/-5 are required for Spy EV-induced IL-1β release

Inflammasomes in innate immune and epithelial cells play an important role in bacterial sensing (Martinon et al, 2002; Hayward et al, 2018). In monocytes, IL-1β is secreted upon activation of the canonical, non-canonical and/or alternative inflammasome (Martinon et al, 2002; Kayagaki et al, 2011; Shi et al, 2014; Gaidt et al, 2016). Notably, we observed that Spy EVs treatment induced expression of the non-canonical inflammasome component, caspase-5, compared with untreated cells (log2FC: 5.45, Dataset EV1; Figs. 1C,D and EV4E). Caspase-4 and -5 and their murine homolog, caspase-11, have been shown to recognize intracellular LPS during Gram-negative infection, and are also activated in response to the Gram-positive species Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) and Listeria monocytogenes (L. monocytogenes) (Shi et al, 2014; Casson et al, 2015; Vanaja et al, 2016; Hara et al, 2018; Krause et al, 2019). Upregulation of caspase-5 upon EV treatment in the absence of a robust interferon signature (Figs. 1 and EV4) prompted us to investigate whether IL-1β might be induced differently by Spy EVs than by their parental cells.

To determine the role of caspase-4 and -5 in Spy EV-induced IL-1β release, we used the chemical inhibitor Ac-LEVD-CHO, which blocks the action of these two caspases. Incubation of monocytes with the caspase-4/-5 inhibitor prior to the addition of Spy EVs or S. pyogenes decreased IL-1β secretion, albeit with a greater reduction in IL- 1β in response to EVs (Fig. 2A,B). In contrast, the levels of caspase-independent cytokines such as IL-6 and IL-1α remained unchanged. Activation of the non-canonical inflammasome can lead to pyroptotic cell death (Shi et al, 2015). However, cell death measured by secretion of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) did not vary upon inhibition of caspase-4/-5 (Fig. 2A,B). To validate that Ac-LEVD-CHO only impairs the function of caspase-4/-5 and does not affect the expression of its genes, we measured the mRNA levels of caspase-4 and -5 as well as IL1B and IL6 using RTqPCR. No difference in the transcript levels for each target gene between untreated vs. Ac-LEVD-CHO-treated cells could be detected (Fig. EV3A), indicating that the observed reduction in IL-1β secretion upon inhibition of caspase-4/-5 does not originate from lower caspase-5 or pro-IL1β gene expression. In addition, we analyzed the amounts of pro-IL1β by immunoblotting. While the induction of pro-IL1β in response to Spy EVs was much lower than for bacterial cells, no difference was found between untreated and Ac-LEVD-CHO-treated cells (Fig. EV3B). Consistent with the fact that LPS is a major activator of caspase-4/-5, Ac-LEVD-CHO also significantly reduced the release of IL-1beta in response to LPS (Fig. EV3C). Finally, we detected significant cleavage of the caspase-4/-5 substrate Ac-LEVD-AFC in cell culture supernatants from monocytes infected with S. pyogenes and, to a lesser extent, in response to Spy EVs as well (Fig. 2C). Collectively, our data suggest that IL-1β release in response to Spy EVs and S. pyogenes requires caspase-4/-5 without inducing cell death.

Figure 2. S. pyogenes EVs are recognized by caspase-4 and caspase-5.

(A, B) IL-1β, IL-6, IL-1α, and LDH released by monocytes after stimulation with either Spy EVs (A) or intact S. pyogenes (B) for 18 h. Monocytes were either preincubated with the caspase-4/-5 inhibitor Ac-LEVD-CHO or left untreated. The percentage of LDH released from the positive control is shown as a measure of cell death. Bars represent the mean ± standard deviation (SD) of four biological replicates. (A) P = 0.0385, (B) P = 0.0036, (C) Caspase-4/5 substrate cleavage in supernatants from monocytes after stimulation with Spy EVs or intact S. pyogenes. Bars represent the mean ± SD of six biological replicates. P = 0.0139 (EVs_3.5 × 109), P = 0.0024 (Spy MOI 5). (D) IL-1β released by BLaER1 cells after stimulation with either Spy EVs (left panel) or S. pyogenes (right panel) for 18 h. BLaER1 cell lines: wild-type (WT), Caspase-4 knock-out (KO, CASP4−/−), Caspase-5 KO (CASP5−/−, clones 1 and 2) and non-targeting control (NTC). Bars represent the mean ± SD of three biological replicates. (Left panel) P = 0.0034, P < 0.0001, P = 0.003. (Right panel) P = 0.0239, P = 0.0131, P = 0.0131. (E) Immunoblot analysis of cleavage products for caspase-1/4/5 in cell culture supernatants from human monocytes & macrophages. Cells were either left untreated or infected with S. pyogenes strains M1T1 5448, M1T1 5448 AP, ISS3348, or ISS3348 Δslo at MOI 5 (covS-: covS inactivation). Representative of four biological replicates. (F) Immunoblot, RTqPCR & ELISA analysis of IL-1β released by monocytes after stimulation with Spy EVs in the presence or absence of BafA1 (100 nM) for 2 h or 18 h. A dotted line indicates the mean expression of the housekeeping genes (GAPDH/TUBB). Representative of four biological replicates. P = 0.0254. (G) Immunoblot analysis of LC3 levels in human monocytes after stimulation with Spy EVs in the presence or absence of BafA1 (100 nM). Bars represent the mean ± SD of four biological replicates. P = 0.0132 (30’), P = 0.0151 (90’). Data information: (ABDG) Two-way ANOVA with Holm–Šídák correction for multiple comparisons was applied for statistical analyses. (C) Multiple t tests with Holm–Šídák correction for multiple comparisons. (F) One-way ANOVA with Holm–Šídák correction for multiple comparisons was applied for statistical analyses. *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, ***P ≤ 0.001, n.s. not significant. Source data are available online for this figure.

Figure EV3. BLaER1 knock-out characterization.

(A) Quantitative real time PCR of selected genes in human monocytes. Shown are mean ± SD of three biological replicates. A dotted line indicates the mean expression of the housekeeping genes (GAPDH/TUBB). (CASP5) P = 0.0013 (−), P = 0.0018 (+). (IL1B) P = 0.0006 (EVs for both comparisons), P = 0.0001 (Spy, for both comparisons). (IL6) P = 0.0001 (EVs for both comparisons), P < 0.0001 (Spy, for both comparisons). (B) Immunoblot analysis of pro-IL-1β in human monocytes. Cells were either left untreated or preincubated with the caspase-4/-5 inhibitor Ac-LEVD-CHO. Representative of three biological replicates. (C) IL-1β in response to LPS in supernatants from human monocytes either left untreated or preincubated with Ac-LEVD-CHO at 18 h. Shown are mean ± SD of three biological replicates. P < 0.0001 (D) Graphical representation of the differentiation protocol of BLaER1 cells as well as CRISPR-Cas9 mutagenesis of BLaER1 cells. The existence of frameshift mutations on each allele of the CASP4−/−, CASP5−/−, TLR2−/−, CASP1−/−, and NLRP3-/- clones was assessed using next generation sequencing. The guide RNAs used for genome editing are shown in the Reagents and Tools Table. Mass spectrometry analysis was used to confirm the absence of caspase-4 and caspase-5 from their respective KO clones compared to wild-type or non-targeted control (NTC) BLaER1 cells. (E–H) IL-6 and LDH released from BLaER1 WT, caspase-4 KO (CASP4−/−), caspase-5 KO clones 1 and 2 (CASP5−/− C1 or C2), and non-targeted cells (NTC). BLaER1 cells were left untreated or were stimulated for 18 h with either Spy EVs or S. pyogenes. The percentage of LDH released from the positive control is shown as a measure of cell death. Bars represent the mean ± SD of three biological replicates. Data information: (A, C, E–H) Two-way ANOVA with Holm–Šídák correction for multiple comparisons was applied for statistical analyses. **P ≤ 0.01, ***P ≤ 0.001, n.s. not significant.

Human monocytes are short-lived, non-replicating cells (Patel et al, 2017), which complicates loss-of-function studies using engineering tools (e.g., CRISPR/Cas9). Furthermore, commonly used monocytic cell lines, such as THP-1, have been shown to only partially mimic the functions of primary cells (Gaidt et al, 2016, 2018). To overcome these limitations, we targeted genes in BLaER1 cells, which have been described to closely recapitulate human monocytic functions such as TLR and inflammasome signaling (Rapino et al, 2013; Gaidt et al, 2016). BLaER1 is an immortalized B cell line which, upon induction of the transcription factor C/EBPα, irreversibly differentiates into monocyte-like cells (Rapino et al, 2013). We have shown that BLaER1 cells respond similarly, albeit less pronounced, to Spy EVs and bacterial cells (Fig. EV2AB). To dissect the individual contributions of caspase-4 and -5 in Spy EV-induced IL-1β release, we generated gene knock-out (KO) BLaER1 cell clones using CRISPR-Cas9 (Fig. EV3D). BLaER1 CASP4−/− cells secreted less IL-1β than their wild-type counterparts upon Spy EVs challenge, while IL-1β secretion in CASP5−/− cells was almost abolished (Fig. 2D, left panel). A slight reduction in IL-1β production was also observed upon stimulation with live S. pyogenes (Fig. 2D, right panel). Consistent with our experiments in primary monocytes, IL-6 and LDH levels were unaltered in wild-type and CASP4−/− and CASP5−/− cells (Fig. EV3E–H). Non-targeted control (NTC, electroporated with a control guide RNA) cells showed similar secretion of IL-1β, IL-6 and LDH when compared to wild-type cells (Figs. 2D and EV3E–H). Immunoblot analysis of cell culture supernatants from human monocytes infected with different M1 serotypes of S. pyogenes revealed no difference in caspase-1/-4/-5 cleavage between wild-type and covS-inactivated (covS-) strains (Fig. 2E). In contrast, when monocytes were differentiated to macrophages, cleavage products for all three caspases were only observed when cells were infected with hypervirulent S. pyogenes harboring covS inactivating mutations leading to increased production of streptolysin O (Slo) (Sumby et al, 2006). Altogether, our experiments suggest that caspase-4 and caspase-5 contribute to IL-1β release in response to Spy EVs and intact S. pyogenes, which is independent of the virulence regulator CovS in monocytes but dependent on CovS in differentiated macrophages.

During inflammasome activation, mature IL-1β is typically secreted through Gasdermin D (GSDMD) pores. However, Spy EV stimulation of human monocytes did not result in cell death. Alternative secretion pathways for IL-1β through secretory lysosomes (Andrei et al, 1999; Semino et al, 2018), microvesicle shedding (MacKenzie et al, 2001), or autophagy (Iula et al, 2018) have been described in LPS-activated monocytes or neutrophils. Consistent with these previous findings, we found that Bafilomycin A (BafA1), a V-ATPase inhibitor shown to stimulate lysosomal exocytosis (Tapper and Sundler, 1995), promotes an increase in EV-induced IL-1β release from human monocytes (Fig. 2F) without affecting pro-IL-1β or caspase-5 expression. Finally, we also observed an increase in LC3-II levels and autophagic flux in human monocytes upon EV treatment (Fig. 2G), suggesting an increase in the formation of autophagosomes.

EV signaling through TLR2-MyD88 are required for cytokine production

Caspase-4/-5 are cytosolic receptors that do not bind directly to any component of Gram-positive lysates (Shi et al, 2014a). Consequently, signaling through other proteins acting upstream of caspase-4 and -5 may be the trigger for IL-1β production. TLRs are the most thoroughly characterized family of PRRs involved in S. pyogenes recognition (Gratz et al, 2008; Loof et al, 2008; Eigenbrod et al, 2015; Fieber et al, 2015). In particular, TLR2 signaling via the adaptor protein MyD88 is essential for generating an inflammatory response to S. pyogenes and other Gram-positive pathogens by promoting NFκB-dependent gene expression (Underhill et al, 1999; Loof et al, 2008). Yet, conflicting results have been published on the role of TLR2 in S. pyogenes recognition (Gratz et al, 2008; Fieber et al, 2015). Since LPS-induced activation of the alternative inflammasome in human monocytes has been linked to lipid A-induced TLR4 signaling, we investigated whether the lipid and lipoteichoic acid (LTA) sensing TLR2 and its adaptor protein MyD88 might coordinate the sensing of Spy EVs. Indeed, TLR2- or MyD88-deficiency in BLaER1 cells severely impaired both IL-1β and IL-6 secretion in response to Spy EVs challenge (Fig. 3A), implying a critical role for TLR2-MyD88 signaling in Spy EVs recognition. In contrast, sensing of S. pyogenes required MyD88, but not TLR2, to induce IL-6 and IL-1β (Fig. 3B), indicating a redundant role for other MyD88-coupled TLRs such as TLR1 or TLR4-9. To address this redundancy, we used a variety of small molecule inhibitors. Treatment of monocytes with TLR2/1 (TLR-IN-C29) or TLR2/6 (Cu-CPT22) inhibitors significantly reduced the release of Spy EV-induced IL-1β, but only minor effects were observed following infection with S. pyogenes (Fig. 3C). Notably, inhibition of the Receptor-Interacting serine/threonine-Protein Kinase 1 (RIPK1), the key kinase mediating the alternative inflammasome pathway upon LPS treatment, resulted in a reduction in IL-1β secretion only in Spy EV-treated cells, but not in those treated with S. pyogenes. In support of TLR2 appearing as the major sensor of Spy EVs, a TLR2 reporter cell-line (HEK-Blue) showed a dose-dependent activity in response to Spy EVs (Fig. 3D). We further examined the potential involvement of TLR4, TLR7, TLR8, and TLR9 in the sensing of intact S. pyogenes cells by means of small molecule inhibitor treatment. We found a role for intracellular TLR8 in mediating IL-1β secretion upon live S. pyogenes infection (Fig. 3E,F). Lastly, and in accordance with previous observations for LPS-stimulated monocytes (Gaidt et al, 2016), both S. pyogenes and its EVs required caspase-8 for IL-1β release (Fig. 3G). Together, we conclude that the activation of the inflammasome in response to Spy EVs is most likely initiated at the cell surface via TLR2, whereas S. pyogenes triggers IL-1β secretion predominantly through TLR8, thereby indicating that internalization of the bacteria is required to activate the inflammasome.

Figure 3. EV-dependent cytokine release requires Toll-like receptor 2-mediated signaling.

(A) IL-1β, IL-6, and LDH in supernatants of BLaER1 WT, MYD88 KO (MYD88−/−), Toll-like receptor 2 KO (TLR2−/−) and NTC cells stimulated with Spy EVs for 18 h. Bars represent the mean ± SD of three biological replicates. (left panel, IL-1β) P < 0.0001 (MYD88−/−), P < 0.0001 (TLR2−/−). (middle panel, IL-6) P = 0.0019 (MYD88−/−), P = 0.0040 (TLR2−/−). (B) IL-1β, IL-6, and LDH released by BLaER1 WT, MYD88−/−, TLR2−/−, and NTC cells after 18 h stimulation with S. pyogenes. Bars represent the mean ± SD of three biological replicates. (left panel, IL-1β) P = 0.0017 (MYD88−/−). (Middle panel, IL-6) P = 0.0016 (MYD88−/−). (A, B) The percentage of LDH released from the positive control is shown as a measure of cell death. (C) IL-1β and IL-6 released by human monocytes that were either left untreated or preincubated with Ac-LEVD-CHO (caspase-4/5), GSK3145095 (RIPK1), TLR2-C29 (TLR2/1, TLR2/6), or CU-CPT22 (TLR2/6). Cells were then left unstimulated or challenged with Spy EVs or S. pyogenes for 18 h. Bars represent the mean ± SD of four biological replicates. (EVs, IL-1β) P = 0.0001, P = 0.0018, P = 0.0003, P = 0.0018. (EVs, IL-6) P = 0.0082. (Spy, IL-1β) P < 0.0001, P = 0.0437. (D) TLR2 activity in HEK-Blue TLR2 cells after stimulation with Spy EVs for 18 h. Baseline represents untreated cells. Bars represent the mean ± SD of four biological replicates. (7 × 108) P < 0.0001, (3.5 × 108) P < 0.0001, (7 × 107) P < 0.0001, (3.5 × 107) P = 0.0081. (E) IL-1β and IL-6 released by human monocytes that were either left untreated or preincubated with TLR inhibitors CLI-095 (TLR4), M5049 (TLR7/8, 0,1 µM = TLR7, 1 µM = TLR8), or TLR9-IN-1 (TLR9). Cells were then left unstimulated or infected with S. pyogenes for 18 h. Bars represent the mean ± SD of four biological replicates. P = 0.0048. (F) IL-1β and IL-6 released by human monocytes that were either left untreated or preincubated with the TLR8 inhibitor CU-CPT9a. Cells were then left unstimulated or infected with S. pyogenes for 18 h. Bars represent the mean ± SD of four biological replicates. P < 0.0001. (G) IL-1β and IL-6 released by human monocytes that were either left untreated or preincubated with the caspase-8 inhibitor Ac-IETD-CHO. Cells were then left unstimulated or challenged with Spy EVs, S. pyogenes, or LPS for 18 h. Bars represent the mean ± SD of four biological replicates. (EVs) P = 0.0043, (Spy) P = 0.0075, (LPS) P = 0.0043. Data information: (A–C, E–G) Two-way ANOVA was applied with Holm–Šídák correction for multiple comparisons. (D) One-way ANOVA was applied with Holm–Šídák correction for multiple comparisons. *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, ***P ≤ 0.001, n.s. not significant. Source data are available online for this figure.

The NLRP3 inflammasome coordinates EV-mediated secretion of IL-1β

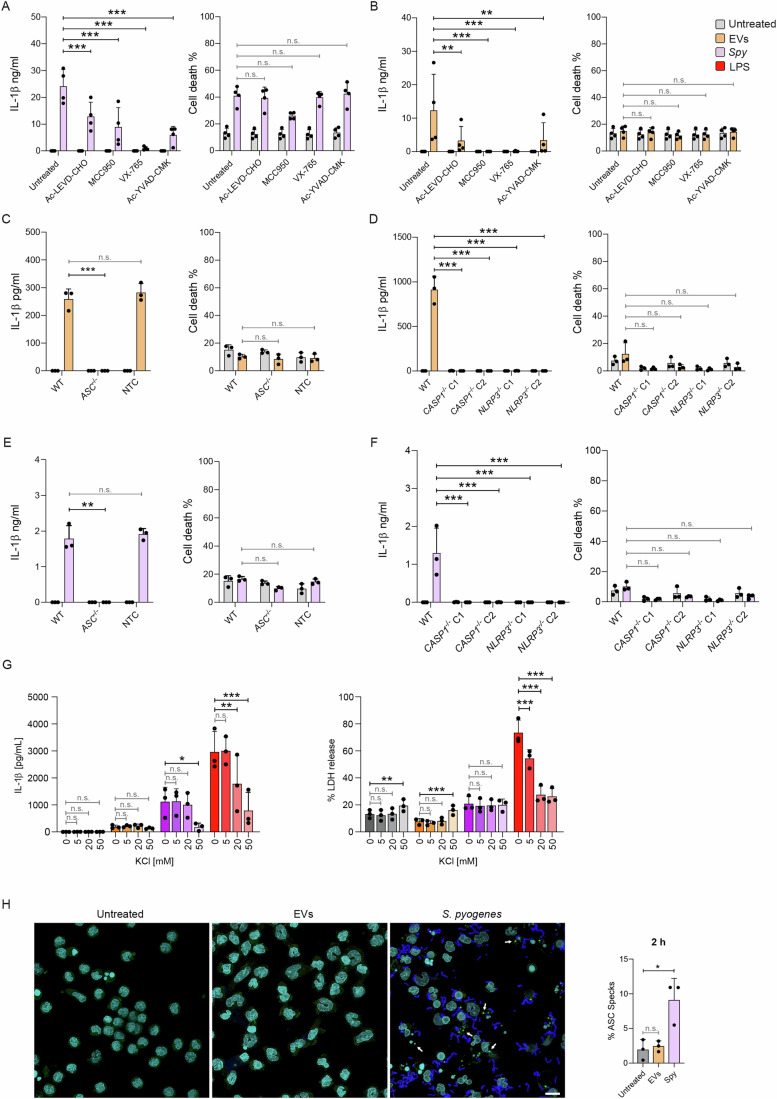

The NLRP3 inflammasome is composed of three main proteins: Nucleotide-binding domain Leucine-rich Repeat family containing a Pyrin domain 3 (NLRP3), Apoptosis-associated Speck-like containing a Caspase recruitment domain (ASC), and caspase-1 (Martinon et al, 2002; Muñoz-Planillo et al, 2013). Previous studies have shown that the NLRP3 inflammasome coordinates IL-1β secretion during S. pyogenes infection (Harder et al, 2009; Lin et al, 2015; Valderrama et al, 2017) and a recent study established that S. aureus EVs are also recognized by this system (Wang et al, 2020). We therefore investigated whether, in addition to caspase-4/-5, the NLRP3 inflammasome contributed to IL-1β release in response to Spy EVs. To this end, we left monocytes untreated or treated them with the NLRP3 inhibitor MCC950, the caspase-1 inhibitor Ac-YVAD-cmk, the caspase-4/-5 inhibitor Ac-LEVD-CHO, or the caspase-1/-4/-5 inhibitor VX-765 prior to stimulation with S. pyogenes or Spy EVs. All inhibitors significantly reduced IL-1β for both S. pyogenes and its EVs (Fig. 4A,B). Release of IL-6 and LDH were comparable for all treatments, with the exception of increased IL-6 and decreased cell death upon inhibition of NLRP3 following infection with S. pyogenes (Figs. 4A,B and EV4A).

Figure 4. The NLRP3 inflammasome contributes to IL-1β and LDH release upon recognition of S. pyogenes EVs.

(A, B) IL-1β and IL-6 released by human monocytes that were either left untreated or preincubated with Ac-LEVD-CHO, MCC950, VX-765, or Ac-YVAD-CMK. Cells were then left unstimulated or stimulated with either S. pyogenes (A) or Spy EVs (B) for 18 h. Bars represent the mean ± SD of four biological replicates. (A) P < 0.0001 (for all comparisons). (B) P = 0.0068, P = 0.0006, P = 0.0006, P = 0.0076. (C, D) IL-1β and LDH were measured in supernatants of BLaER1 WT, PYCARD KO (ASC-/-), Caspase-1 KO (CASP1−/− clone 1 and 2), NLRP3 KO (NLRP3−/− clone 1 and 2), and NTC cells after 18 h either left untreated or stimulated with Spy EVs. Bars represent the mean ± SD of three biological replicates. (C) P = 0.0010. (D) P < 0.0001 (for all comparisons). (E, F) IL-1β and LDH were measured in supernatants of BLaER1 WT, ASC−/−, CASP1−/− clone 1 and 2, NLRP3−/− clone 1 and 2, and NTC cells after 18 h either left untreated or stimulated with S. pyogenes. Bars represent the mean ± SD of three biological replicates. (E) P = 0.0016. (F) P = 0.0003 (for all comparisons). (G) IL-1β and LDH in supernatants from BLaER1 WT cells after 18 h, either left untreated or stimulated with Spy EVs, S. pyogenes, or LPS (200 ng/mL). Bars represent the mean ± SD of three biological replicates. (IL-1β) P = 0.0177 (Spy, 50 mM), P = 0.0017 (LPS, 20 mM), P < 0.0001 (LPS, 50 mM). (LDH) P = 0.0084 (Untreated, 50 mM), P = 0.0007 (EVs, 50 mM), P < 0.0001 (LPS, all comparisons). (H) Immunofluorescence staining and corresponding quantification results for ASC speck formation in human monocytes either left untreated or stimulated with Spy EVs or S. pyogenes for 2 h (scale bar: 10 µm). White arrows indicate ASC specks. Bars represent the mean ± SD of three biological replicates. P = 0.0103. Data information: (A–G) The percentage of LDH released from the positive control is shown as a measure of cell death. Two-way ANOVA was applied with Holm–Šídák correction for multiple comparisons. (H) One-way ANOVA was applied with Holm–Šídák correction for multiple comparisons. *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, ***P ≤ 0.001, n.s. not significant. Source data are available online for this figure.

To further validate these results, we used BLaER1 monocytes lacking ASC (Vierbuchen et al, 2017), caspase-1, or NLRP3. Consistent with the pharmacological inhibition, the genetic deficiency of NLRP3, ASC, or CASP1 abolished IL-1β secretion in response to S. pyogenes or Spy EVs treatment (Fig. 4C–F), while IL-6 levels remained unchanged for all cell lines and conditions tested (Fig. EV4B,C). In addition, whereas the release of LPS-induced IL-1β and LDH was strongly dependent on K+ efflux, no effect of extracellular potassium could be detected for Spy EVs (Fig. 4G). In contrast, S. pyogenes-infected monocytes showed significantly reduced IL-1β secretion in the presence of 50 mM KCl, indicating that the reduction of intracellular K+ contributes to activation of the inflammasome triggered by S. pyogenes, but not by its derived EVs. Using immunofluorescence microscopy, we further analyzed ASC speck formation in human monocytes either treated with Spy EVs or infected with S. pyogenes. In accordance with the previously reported alternative inflammasome pathway, which lacks the typical features of classical NLRP3 inflammasome activation (Gaidt et al, 2016), we observed ASC specks and cleavage of GSDMD only in S. pyogenes-infected monocytes, but not in EV-treated cells (Figs. 4H and EV4E).

Since NLRP6 and NLRP7 have been reported to recognize LTA and acetylated lipoproteins (Khare et al, 2012; Hara et al, 2018), we also attempted to generate corresponding knockout cells for these proteins to study their involvement in inflammasome activation upon Spy EVs or S. pyogenes challenge. However, we were unable to detect expression of either sensor in BLaER1 cells or in primary monocytes (Fig. EV4D). Collectively, these results indicate that Spy EVs or S. pyogenes engage the NLRP3 inflammasome as well as caspase-4 and -5, but employ distinct upstream sensors and signaling cascades for the induction and release of IL-1β in monocytes.

Caspase-4/-5-Mediated Secretion of IL-1β is Triggered by Lipoteichoic Acid

LTA is a major component of the cell membrane of Gram-positive bacteria that is sensed by TLR2 (Schwandner et al, 1999; Takeuchi et al, 1999) and has been shown to induce caspase-11-mediated secretion of IL-1β in mice (Hara et al, 2018). Since we found that Spy EVs induced secretion of IL-1β depends on TLR2, we hypothesized that LTA might be the bacterial ligand triggering caspase-4/-5 signaling. The clinical isolate used in this study is highly encapsulated due to its inactive two-component system CovRS (Resch et al, 2016). Therefore, we first examined whether LTA was available on the surface of this bacterial strain and its EVs. Using immunogold-labelling of LTA and electron microscopy, we observed that this structural acid can indeed be detected on the surface of S. pyogenes and its EVs (Fig. 5A,B, white arrows). In addition, we used immunoblotting to confirm the presence of LTA in our EV preparations (Fig. 5C).

Figure 5. Lipoteichoic acid conserved in Gram-positive EVs promotes caspase-4/-5-dependent IL-1β secretion.

(A) S. pyogenes cells imaged by Scanning Electron Microscopy and immunogold staining (SEM, scale bar = 200 nm). (B) Immunogold-labelling of surface lipoteichoic acid from purified Spy EVs (LTA clusters indicated with white arrows, scale bar = 200 nm). (C) Immunoblot analysis of LTA in Spy EVs. (D) IL-1β in supernatants from monocytes either left untreated or preincubated with Ac-LEVD-CHO prior to the addition of S. pyogenes LTA after 18 h. Bars represent the mean ± SD of four biological replicates. P = 0.0181. (E) IL-1β in supernatants from BLaER1 cells either left untreated or preincubated with Ac-LEVD-CHO prior to the addition of S. pyogenes LTA after 18 h. Bars represent the mean ± SD of three biological replicates. P = 0.0177. (F) IL-1β release at 18 h from monocytes that were left untreated or treated with S. pyogenes LTA, either directly applied (LTA) or transfected using Lipofectamine LTX (LTx:LTA). Bars represent the mean ± SD of four biological replicates. (G) TLR2 activity in HEK-Blue TLR2 cells after stimulation with Spy LTA for 18 h. Baseline represents untreated cells. Bars represent the mean ± SD of four biological replicates. (H) Immunoblot, RTqPCR & ELISA analysis of IL-1β released by monocytes after stimulation with S. pyogenes LTA in the presence or absence of BafA1 (100 nM) for 2 h or 18 h. Bars represent the mean ± SD of four biological replicates. P = 0.0067. (I) Immunoblot analysis of LC3 levels in human monocytes after stimulation with S. pyogenes LTA in the presence or absence of BafA1 (100 nM). Bars represent the mean ± SD of four biological replicates. P = 0.0412 (30’), P = 0.0143 (60’), P = 0.0002 (90’). (J) IL-1β release at 18 h from monocytes either left untreated or preincubated with Ac-LEVD-CHO before the addition of EVs from S. aureus (left), S. agalactiae (middle), or B. subtilis (right). Bars represent the mean ± SD of four biological replicates. P = 0.0164 (S. aureus), P = 0.0099 (S. agalactiae). (K) IL-1β and IL-6 in supernatants from monocytes or BLaER1 cells either left untreated or stimulated with Spy EVs isolated −/+ LtaS-IN-1771 for 18 h. Bars represent the mean ± SD of three biological replicates. (Primary, IL-1β) P = 0.0003 (both comparisons). (Primary, IL-6) P < 0.0001 (both comparisons). (BLaER1, IL-1β) P = 0.0005, P = 0.0160, P = 0.0044. (BLaER1, IL-6) P = 0.0005, P = 0.0051, P = 0.0161. Data information: (D, E, I) Two-way ANOVA was applied with Holm–Šídák correction for multiple comparisons. (F, H, K) One-way ANOVA was applied with Holm–Šídák correction for multiple comparisons. (J) Statistical significance was assessed using paired t tests. *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, ***P ≤ 0.001, n.s. not significant. Source data are available online for this figure.

LTA mutants of Gram-positive bacteria have been reported to display severe growth defects (Schneewind and Missiakas, 2017), which is why we used purified LTA from S. pyogenes to test its role in monocyte activation. Consistent with our hypothesis, stimulation of monocytes or BLaER1 cells with S. pyogenes LTA induced IL-1β secretion, which was significantly reduced upon pretreatment with the caspase-4/-5 inhibitor peptide Ac-LEVD-CHO (Fig. 5D,E), while IL6 secretion and LDH release were not affected (Fig. EV5A,B). Moreover, the lipofectamine-mediated encapsulation and intracellular delivery of LTA into monocytes did not further increase IL-1β production (Fig. 5F) or affect IL-6 and LDH release (Fig. EV5C), suggesting that the caspase-4/-5-mediated signaling triggered by LTA most likely begins at the cell surface via TLR2, in line with the alternative inflammasome pathway described for various TLR ligands (Gaidt et al, 2016; Unterberger et al, 2023). Finally, to test whether LTA from other Gram-positive bacteria similarly induces caspase-4/5-dependent IL-1β secretion, we used LTA derived from S. aureus and, akin to S. pyogenes LTA, we observed a caspase-4/-5-dependent reduction in the release of IL-1β, but not IL-6 (Fig. EV5D). Of note, we also detected a significant upregulation of caspase-5 gene expression upon stimulation with both S. pyogenes and S. aureus LTA, whereas gene expression levels of caspase-4 remained unaffected (Fig. EV5E). In line with our previous results showing Spy EV-induced TLR2 activity in a reporter cell-line, LTA from both S. pyogenes and S. aureus induced TLR2 activity in a dose-dependent manner, albeit S. aureus LTA was considerably more potent and showed a measurable response at concentrations as low as 0.01 µg/mL (Figs. 5G and EV5F). As shown before for Spy EVs, LTA-induced IL-1β secretion is dependent on caspase-8 (Fig. EV5G). Furthermore, BafA1 increased IL-1β release in response to S. pyogenes LTA, suggesting a vesicular secretion mechanism for IL-1β as observed for Spy EVs (Fig. 5H). Since the turnover of autophagosomes was also significantly increased by S. pyogenes LTA (Fig. 5I), a positive role of autophagy during IL-1β secretion in human monocytes upon Spy EV or LTA encounter may be a plausible conclusion.

Figure EV5. Cytokine controls and cell death of monocytes and BLaER1 cells: role of LTA in EV-dependent monocyte activation.

(A) IL-6 and LDH release at 18 h from monocytes that were left untreated or incubated with Ac-LEVD-CHO before the addition of S. pyogenes LTA. Shown are mean ± SD of four biological replicates. P = 0.0069. (B) IL-6 and LDH release at 18 h from BLaER1 cells that were left untreated or incubated with Ac-LEVD-CHO prior to addition of purified S. pyogenes LTA. Shown are mean ± SD of three biological replicates. (C) IL-6 and LDH release at 18 h from monocytes that were left untreated or treated with S. pyogenes LTA, either directly applied (LTA) or transfected using Lipofectamine LTX (LTx:LTA). Shown are mean ± SD of four biological replicates. (D) IL-1β and IL-6 release at 18 h from monocytes that were left untreated or incubated with Ac-LEVD-CHO before the addition of S. aureus LTA. Shown are mean ± SD of four biological replicates. P = 0.0374. (E) Quantitative real time PCR of CASP5 and CASP4. Shown are mean ± SD of three biological replicates. A dotted line indicates the mean expression of the housekeeping genes (GAPDH/TUBB). P < 0.0001 (for all comparisons). (F) TLR2 activity in HEK-Blue TLR2 cells after stimulation with S. aureus LTA for 18 h. Baseline represents untreated cells. Bars represent the mean ± SD of four biological replicates. (G) IL-1β and IL-6 released by human monocytes that were either left untreated or preincubated with the caspase-8 inhibitor Ac-IETD-CHO. Cells were then left unstimulated or treated with S. pyogenes LTA for 18 h. Bars represent the mean ± SD of four biological replicates. P = 0.0066. (H) Mean size and particles/mL of S. pyogenes, S. aureus, B. subtilis, and S. agalactiae EVs (n = 2). (I) IL-6 and LDH release from monocytes either left untreated or preincubated with Ac-LEVD-CHO before the addition of EVs from S. aureus, S. agalactiae, or B. subtilis for 18 h. Shown are mean ± SD of four biological replicates. (J) Immunoblot analysis of LTA in bacterial pellets treated −/+ LtaS-IN-1771 and particles/mL of corresponding S. pyogenes EVs. Representative image of 2 biological replicates is shown. (K) S. pyogenes growth in the presence of LtaS-IN-1771 in THB media. Shown are mean ± SD of three biological replicates. (3 h) P = 0.0010, (4h-8h) P < 0.0001. Data information: (ABDEGK) Two-way ANOVA was applied with Holm–Šídák correction for multiple comparisons. (C) One-way ANOVA was applied with Holm–Šídák correction for multiple comparisons. (I–H) Statistical significance was assessed using paired t tests. *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, ***P ≤ 0.001, n.s. not significant.

EVs from other Gram-positive bacteria induce IL-1β through caspase-4/-5

Since the synthesis of teichoic acids is moderately conserved among Gram-positive bacteria (Reichmann and Gründling, 2011; Brown et al, 2013), we asked whether EVs derived from other Gram-positive bacteria could trigger IL-1β production through caspase-4 and -5. In fact, monocytes treated with EVs from S. aureus, Streptococcus agalactiae, or Bacillus subtilis released less IL-1β when caspase-4/-5 was inhibited, while IL-6 secretion remained unaffected (Figs. 5J and EV5H,I), demonstrating that caspase-4/-5 are also involved in IL-1β release in response to EVs derived from other Gram-positive bacteria.

LTA-depleted EVs severely attenuate the IL-1β response of human monocytes

To determine whether surface ligands other than LTA are sensed upstream of caspase-4/-5 activation, we treated S. pyogenes with compound 1771, which was shown to inhibit LTA biosynthesis in S. aureus (Richter et al, 2013; Serpi et al, 2023) to produce LTA-depleted Spy EVs (Fig. EV5J). Consistent with its reported antimicrobial properties, compound 1771 significantly delayed the growth of S. pyogenes compared with DMSO-treated control cultures (Fig. EV5K). When monocytes were treated with LTA-depleted Spy EVs, their release of both IL-1β and IL-6 was significantly decreased (Fig. 5K). To a lesser extent, this phenotype was also reproduced in BLaER1 cells, indicating that LTA on Spy EVs is the predominant factor responsible for TLR and inflammasome activation.

Free LTA in EV-depleted supernatants recapitulates monocyte activation in response to EVs

In addition to EV-bound LTA, supernatants of S. pyogenes also contain free LTA that is released during bacterial growth. To compare the effects of EV-bound vs. free LTA on monocyte activation, we first measured the amount of LTA in double-filtered S. pyogenes supernatants before and after EV isolation (Fig. 6A). The LTA concentration in the remaining supernatants was reduced by ~45% after removal of EVs using ultracentrifugation. We then determined the amounts of cytokines and LDH released by human monocytes treated either with Spy EVs or with EV-depleted supernatant (SUP) (Fig. 6B). Notably, due to the presence of Slo in the EV-depleted SUPs from WT S. pyogenes, monocytes displayed high amounts of cell death and no significant release of IL1β or IL-6 could be observed. Therefore, we additionally isolated EVs and EV-depleted SUP from an S. pyogenes slo deletion strain. Increasing volumes of Δslo EV-depleted SUP significantly induced IL-1β and IL-6 secretion without affecting cell survival. Immunoblotting confirmed comparable levels of LTA in EV-depleted supernatants from WT and Δslo S. pyogenes (Fig. 6C). Interestingly, THB alone also led to significant IL-6 secretion by human monocytes, which is most likely attributable to the presence of beef heart peptones or high salt concentrations within the concentrated media. Furthermore, protein analysis using mass spectrometry revealed an 84% overlap between EVs and EV-depleted supernatants, suggesting that a high percentage of proteins encapsulated in EVs is also released into the media (Fig. 6D). Finally, as for monocytes treated with Spy EVs, stimulation with EV-depleted SUP prevented caspase-3 activation and induced phosphorylation of the MAP kinase (MAPK) p44/42 (ERK1/2) (Fig. 6D) indicative of monocyte survival pathways being activated.

Figure 6. Spy EVs isolated using size exclusion chromatography partially recapitulate the monocyte response against conventional EV preparations.

(A) LTA concentration in double-filtered S. pyogenes culture supernatants before and after ultracentrifugation. Bars represent the mean ± SD of four biological replicates. P = 0.0080. (B) IL-1β, IL-6, and LDH released by monocytes after 18 h stimulation with either Spy EVs, THB medium, or EV-depleted supernatants (SUP) derived from either S. pyogenes WT or Δslo mutant strains. The percentage of LDH released from the positive control is shown as a measure of cell death. Bars represent the mean ± standard deviation (SD) of four biological replicates. (IL-1β) P < 0.0001. (IL-6) P < 0.0001 (THB, all comparisons), P = 0.0020, P = 0.0002, P < 0.0001. (LDH) P < 0.0001 (all comparisons). (C) Immunoblot of Slo and LTA in EV-depleted supernatants from S. pyogenes WT (4 biological replicates) or Δslo mutant strains. THB media was used as negative control. (D) Venn diagram & immunoblots for EV-depleted supernatants. The Venn diagram shows protein expression in ultracentrifuged EV preparations (EV UC) vs. EV-depleted supernatants. Numbers indicate the total amount of proteins for each category. Immunoblots display caspase-3 cleavage and phospho-p44/42 MAPK in human monocytes after 18 h stimulation with either Spy EVs, THB medium, or EV-depleted supernatants (SUP) derived from either S. pyogenes WT or Δslo mutant strains. Representative of four biological replicates. (E) LTA and protein concentration in 28 fractions of double-filtered S. pyogenes culture supernatant fractionated using size exclusion chromatography. Bars represent the mean ± standard deviation (SD) of three biological replicates. Immunoblot shows LTA present in fractions 8–28. (F) Venn diagrams showing protein expression in ultracentrifuged EV preparations (EV UC) vs. pooled SEC fractions 8–16 (EVs) or 17–28 (soluble), respectively. (G) Concentration, size, and zeta potential of Spy EVs analyzed with the exoid instrument. Bars represent the mean ± SD of three biological replicates. (H) LTA concentration in EVs UC vs. EVs SEC (left panel). Bars represent the mean ± SD of four vs. two biological replicates. LDH (middle panel) and IL-6 (right panel) released by human monocytes treated with Spy EVs isolated using SEC for 18 h. Bars represent the mean ± SD of seven biological replicates with pooled EV fractions from 2 SECs (black circles: SEC1 F8-16; grey circles: SEC2 F8-15). P = 0.0299 (LDH), P = 0.0003 (IL-6). (I) TLR2 activity in HEK-Blue TLR2 cells after stimulation with Spy EVs isolated using SEC for 18 h. Baseline represents untreated cells. Bars represent the mean ± SD of eight biological replicates with pooled EV fractions from 2 SECs (black circles: SEC1 F8-16; grey circles: SEC2 F8-15). P = 0.0007, P = 0.0071. (J) Immunoblots displaying caspase-3 cleavage, phospho-p44/42 MAPK, and caspase-5 expression in human monocytes after 18 h stimulation with Spy EVs isolated using SEC. Representative of four biological replicates. Data information: (A, G, H) Statistical significance was assessed using unpaired t test. (B, H) Owo-way ANOVA was applied with Holm–Šídák correction for multiple comparisons. *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, ***P ≤ 0.001, n.s. not significant. Source data are available online for this figure.

Spy EVs isolated using size exclusion chromatography (SEC) confirm that LTA is as driving factor for monocyte activation

Given the growing interest in EVs, isolation methodologies are constantly evolving and refined (Welsh et al, 2024). Since our EV preparations using ultracentrifugation most likely also contain non-vesicular extracellular particles (NVEP) such as pili, phages, or proteins, we attempted to isolate Spy EVs via size exclusion chromatography (SEC) as previously described for E. coli and other bacteria (Watson et al, 2021). In parallel to SEC, we processed the culture supernatants of S. pyogenes by ultracentrifugation to directly compare the EVs obtained. Figure 6E shows the LTA and protein concentration in sequential fractions, which increase successively. Using SDS-PAGE and TRPS, we identified Spy EVs enriched within the fractions 8-16 of SEC1, 8-15 of SEC2, and 8-13 of SEC3 (Appendix Fig. S2A). Characteristic blockage traces and size/concentration histograms of EVs UC and the pooled SEC fractions are summarized in Appendix Fig. S2B. Traces from individual SEC fractions are shown in Appendix Fig. S2C. Proteomic characterization revealed a 65% and 80% overlap between EVs derived from ultracentrifugation (EV UC) and SEC fractions 8-16 (EVs) and 17–28 (soluble), respectively. Since NTA analysis was not sensitive enough to detect particles in our SEC fractions, we used TRPS to determine the number, size, and zeta potential of our comparative UC and SEC-isolated EVs (Fig. 6G). We found negligible evidence of EV-aggregation after prolonged storage in PBS, supported by a unimodal size distribution (Appendix Fig. S3A). While the size of UC- and SEC-derived Spy EVs was comparable, the concentration of SEC EVs was one order of magnitude lower than that of the EV UC batches (1010 vs. 1011 particles/mL). The zeta-potential of EVs in PBS ranged from −16 to −24 mV (UC mean: −22 ± 2.0, SEC mean: −21 ± 3.3), which is commonly observed for EVs and indicates the presence of negatively charged cell-wall teichoic acid and membrane-anchored lipoteichoic acid (Rogers et al, 2023). Stimulation of human monocytes with SEC EVs significantly increased cell viability and IL-6 secretion (Fig. 6H). In addition, SEC EVs elicited pronounced TLR2 activity in HEK-Blue TLR2 reporter cells (Fig. 6I). In line with the lower particle and LTA concentration of SEC EVs compared to EVs UC (0.171 and 0.413 µg LTA per 1.9 × 108 particles for SEC1 and SEC2, respectively), the release of IL-1β was barely measurable (Appendix Fig. S3B). In fact, a dose response experiment with Spy LTA revealed that the minimal concentration of LTA required to achieve measurable IL-1β secretion was 0,5 µg/mL (Appendix Fig. S3C). However, we also detected inhibition of caspase-3 activation as well as the induction of p44/42 (ERK1/2) MAPK phosphorylation and caspase-5 protein expression upon SEC EV treatment. Conclusively, the SEC EV data corroborate the results of EV UC, with LTA being a major driver of monocyte activation and the subsequent inflammation in response to Spy EVs.

Discussion

Murine infection models have been used primarily to understand the role of specific receptors and downstream signaling mediators recognizing the strict human pathogen S. pyogenes (Watson et al, 2016). Although these models are extremely informative and enable the study of systemic infections and therapeutic interventions, it remains challenging to assess their contributions due to the intrinsic differences between the innate immune system of mice and humans (Heil et al, 2004; Hasan et al, 2005; Khare et al, 2012; Gaidt et al, 2016).

In the present study, we explored the response of primary human monocytes as well as monocyte-like BLaER1 cells to hypervirulent S. pyogenes and its EVs and identified mediators of recognition and downstream signaling events. Strikingly, only one report using murine macrophages has so far addressed the cellular response during S. pyogenes infection on a genome-wide level (Goldmann et al, 2007), and to our knowledge, no reports on primary human monocytes or macrophages have been published to date. Our RNA sequencing results revealed that responses triggered by S. pyogenes and its EVs strongly overlap, consistent with the observation that Spy EVs contain at least half of the proteins of the total proteome of their parental cells (Resch et al, 2016). Nonetheless, S. pyogenes and its EVs regulate the expression of distinct sets of genes in monocytes, indicating that unique components of intact bacteria or EVs convey a differential immune response.

In the broad spectrum of S. pyogenes clinical manifestations, inflammation plays a critical role in preventing bacterial invasion and limiting an excessive, devastating tissue-destructive immune response. It is well-established that interferons expressed during viral infections are beneficial to the host (Isaacs and Lindenmann, 1957). Notably, interferons produced during bacterial infections have been shown to play both protective and detrimental roles, depending on the bacterial species and the site of infection (Kovarik et al, 2016). In mice, the balance between protection and damage during S. pyogenes infection is orchestrated by IL-1β levels, a key immunoregulatory and proinflammatory cytokine matured by type I interferon-regulated multiprotein complexes, the inflammasomes (Castiglia et al, 2016). Similarly, studies with IL-1β inhibitors suggest a central role of IL-1β in controlling S. pyogenes dissemination in the human body (LaRock et al, 2016).

On one side of this balance, S. pyogenes triggers an interferon-mediated signature that is distinct from its EVs, as demonstrated here by unbiased RNA-Seq profiling. These results are consistent with a report showing that biopsies from patients with necrotizing streptococcal soft tissue infection (NSTI) displayed a recognizable IFN signature that was absent in polymicrobial NSTI’s (Thänert et al, 2019). On the other side, we found that IL-1β production in response to S. pyogenes or its EVs converge at the NLRP3 inflammasome, although different sensing and signaling routes are employed. Accordingly, several studies have demonstrated that NLRP3 is a key sensor of Gram-positive bacteria and a recent report indicated that it participates in the recognition of S. aureus EVs (Mariathasan et al, 2006; Harder et al, 2009; Wang et al, 2020).

In addition to the canonical inflammasome, two other systems, the non-canonical inflammasome and the alternative inflammasome, contribute to the production of IL-1 β in human monocytes (Shi et al, 2014; Gaidt et al, 2016), although little is known about the molecular interactions and crosstalk between the components of these three systems. In this respect, an important observation of this study is the identification of the non-canonical components of the inflammasome, caspase-4/-5, as mediators of IL-1β release induced by Spy EVs and to a lesser extent, by S. pyogenes. In most tissues, basal expression of caspase-5, like murine caspase-11, is low and transcription has been shown to be induced by LPS and IFN-γ (Lin et al, 2000; Casson et al, 2015; Viganò et al, 2015) through TLR/TRIF signaling, whereas caspase-4 is typically constitutively expressed (Shi et al, 2014). Consequently, we report a significant upregulation of caspase-5, but not caspase-4 upon challenge with Spy EVs or purified LTA. Although RNA sequencing revealed a slight increase in caspase-5 transcription in response to parental S. pyogenes cells, the expression level was considerably lower than in monocytes treated with Spy EVs and could not be validated by RT-qPCR. This could be explained by the differential sensing modes identified in monocytes, TLR8 for intact bacteria and TLR2 for Spy EVs, the former sensing bacterial RNA and predominantly activating interferon responses and the latter robustly activating NF-kB target genes such as caspase 5. Furthermore, several type III secretion effector proteins from Gram-negative bacterial pathogens have been demonstrated to actively suppress inflammasome activation (Galle et al, 2008; Brodsky et al, 2010; LaRock and Cookson, 2012; Kobayashi et al, 2013). Moreover, Gram-positive Streptococcus pneumoniae as well as Streptococcus oralis have been shown to prevent inflammasome assembly by introducing oxidative stress into host cells through the production of hydrogen peroxide (Erttmann and Gekara, 2019). Therefore, future work should address whether caspase-5 gene expression is regulated in a temporal- and redox-dependent manner during infection with S. pyogenes.

During Gram-negative bacterial infection, binding of LPS to caspase-4/-5/-11 results in Gasdermin D cleavage, cytosolic leakage, and pyroptotic cell death (Shi et al, 2015). In contrast, the activation of caspase-4/-5/-11 leading to IL-1β production by Gram-positive bacteria does not always result in cell death (Hara et al, 2018; Krause et al, 2019), which is in agreement with our findings as we did not observe a reduction in S. pyogenes-induced cytotoxicity when caspase-4/-5 were inhibited. Interestingly, a recent report demonstrates that S. pyogenes infection induces caspase-4 expression in human neutrophils, indicating that this system participates in S. pyogenes-induced IL-1β production in other cell types as well (Williams et al, 2021).

Although TLR2 has traditionally been linked to the recognition of Gram-positive bacteria (Schwandner et al, 1999; Takeuchi et al, 1999; Underhill et al, 1999), S. pyogenes infection of mice lacking TLR2 results in variable susceptibility compared to wild-type mice (Gratz et al, 2008; Fieber et al, 2015). Furthermore, TLR2 contributes to the sensing of bacterial EVs (Prados-Rosales et al, 2011; Kim et al, 2012; Shen et al, 2012; Choi et al, 2018) and mediates priming of the NLRP3 inflammasome during infection with S. aureus or S. pneumoniae in macrophages (Witzenrath et al, 2011; Wang et al, 2020). In monocytes, however, priming is not required for NLRP3 inflammasome activation, allowing direct release of IL-1β/IL-18 in response to TLR stimulation via the alternative inflammasome pathway (Netea et al, 2009; Viganò et al, 2015; Gaidt et al, 2016; Gritsenko et al, 2020). Here, we show that TLR2 is differentially involved in the sensing of Spy EVs and S. pyogenes: whereas EVs induced IL-6 and IL-1β via this receptor, TLR2 contributed only slightly to IL-1β secretion during bacterial infection. In fact, our results confirm previous findings that endolysosomal TLR8 is the primary receptor for S. pyogenes in human monocytes (Eigenbrod et al, 2015) that activates inflammatory responses.

We provide evidence that LTA, decorating the surface of S. pyogenes and its EVs, modulates caspase-4/-5-dependent responses. Noteworthily, S. pyogenes-derived LTA has already been described to prime the NLRP3 inflammasome in macrophages (Richter et al, 2021). Furthermore, we have shown that caspase-4/-5-dependent IL-1β released in response to EVs is conserved for a variety of Gram-positive species. Nevertheless, in contrast to LPS, it has been demonstrated that caspase-4/-5/-11 do not bind directly to any component present in lysates of several Gram-positive species (Shi et al, 2014), suggesting that other sensors act upstream of these enzymes. In line with this hypothesis, caspase-11 coordinates the sensing of cytosolic LTA from L. monocytogenes as a component of the NLRP6 inflammasome in mice (Hara et al, 2018). In addition, a newly identified sensor (NLRP7) that recognizes acylated Gram-positive lipoproteins, has been described in humans (Khare et al, 2012). Since we were unable to detect the expression of NLRP6 nor NLRP7 in monocytes, it remains to be elucidated whether any other cytosolic sensor acts upstream of caspase-4/-5 during encounters with Gram-positive bacteria. However, given that in our experimental set up, the cytosolic presence of LTA was not required to trigger caspase-4/-5 dependent IL-1β production, we believe that the upstream receptor(s) of this cascade are located on the cell surface. Since LPS stimulation of human monocytes has been reported to activate an alternative TLR4-linked and calcium-flux-dependent, one-step inflammasome pathway, it seems plausible that a similar mechanism might exist for TLR2 and LTA that potentially also involves caspase-4/-5. Indeed, TLR2 agonists have been implicated in the activation of the alternative inflammasome involving TRAF6, TAK1, and IKKβ in monocytes (Chen et al, 2023). Here, we found a dependence on TLR2 and the previously described alternative inflammasome component RIPK1 for IL-1β secretion solely for Spy EVs, indicating that inflammasome activation by intact S. pyogenes can be triggered by various sensor proteins. Consistent with these results, a previous report demonstrated that Spy EVs from a lgt mutant strain, characterized by a defect in lipoprotein modification, did not activate a TLR2-reporter cell line (Biagini et al, 2015). Furthermore, contrary to monocytes infected with S. pyogenes, monocytes stimulated with Spy EVs display hallmarks of the alternative inflammasome pathway (Gaidt et al, 2016) by lacking ASC speck formation or cleavage of GSDMD, and the resulting IL-1β secretion was also independent of potassium efflux. Similarly, previous research suggests that ASC specks are not required for caspase-1 activation in all instances (Nagar et al, 2021). While monocytes infected with S. pyogenes partially exhibit characteristics of the classical NLRP3 inflammasome, we found a comparable induction of caspase cleavage in both WT and a slo deletion strain, although Slo has been proven to be essential for inflammasome engagement in macrophages in providing signal 2 (Harder et al, 2009; Richter et al, 2021). In monocytes, however, signal 2 is dispensable and a TLR8 mediated one-step inflammasome activation process appears to take place. Moreover, both S. pyogenes and its EVs rely on caspase-4/-5 and -8 activities to facilitate IL-1β secretion. Caspase-4/-5 have been identified to facilitate LPS-induced IL-1β release in monocytes (Viganò et al, 2015), but how they fit into the alternative inflammasome pathway described by Gaidt et al, 2016 is currently unknown. Of note, we were unable to find evidence of caspase cleavage in response to Spy EVs. Given that the EV-induced IL-1β response is significantly weaker than that induced by S. pyogenes, this could be due to a sensitivity issue that prevents us from detecting caspase cleavage products. However, caspase activity does not always result in cleavage (Stennicke et al, 1999; Guey et al, 2014; Krause et al, 2018). In fact, initiator caspases (Muzio et al, 1998; Boatright et al, 2003; Pop et al, 2006), but also caspase-1 (Conos et al, 2016), have been reported to be activated by dimerization, with cleavage serving either to stabilize the dimer or to terminate protease activity (Boucher et al, 2018). In line with the aforementioned missing signs for classical inflammasome activation, it is plausible to assume that Spy EV induced-caspase activation is mild and does not necessarily result in cleavage. Finally, the discovery of additional players such as the tyrosine-protein kinase SYK as well as the adaptor protein SCIMP mediating inflammasome activation through TLR2/4 (Zewinger et al, 2020), suggests that there might not be a unique signaling pathway for the alternative inflammasome. Instead, some degree of exchangeability between signaling molecules might ensure the proper transmission of danger signals depending on their origin. Future studies are necessary to determine the exact sequence and molecules involved in caspase-1 activation and subsequent IL-1β release in response to S. pyogenes or its derived EVs.

The leaderless cytokine IL-1β is generally released during pyroptosis, requiring GSDMD-dependent pore formation (Evavold et al, 2018; Heilig et al, 2018). However, the absence of cell death in response to Spy EVs points towards a GSDMD-independent route of secretion. Notably, secretory lysosomes have been described to serve as non-classical pathway for IL-1β release upon LPS-induced alternative inflammasome activation in human monocytes (Andrei et al, 1999). Likewise, we observed elevated IL-1β levels in monocytes stimulated with BafA1 to excrete lysosomes. In addition, we noticed increased autophagosome formation and turn over in response to Spy EVs and LTA, indicating the induction of autophagic processes. Accordingly, autophagy has been shown to be important for monocyte survival and differentiation (Zhang et al, 2012). Since increased autophagy has also been reported to promote unconventional IL-1β secretion (Dupont et al, 2011), further studies should evaluate the molecular composition of the monocytes soluble and vesicular proteome following Spy EV treatment.

In this study, we titrated and evaluated a biologically relevant Spy EV dosage based on particle count (and not on protein content, as mostly reported in bacterial EV-host-cell-response experiments) to avoid excessive over-dosing. Moreover, because EV isolation techniques are continuously evolving, we set out to refine our EV-isolation procedures with the aim to localize LTA (being the primary agent for monocyte activation) to vesicular and non-vesicular/soluble entities. To this end, monocytes were incubated with EV-depleted supernatants as well as Spy EVs isolated using SEC, presumably depleted from potential non-vesicular secreted entities to a higher extend as compared to EVs UC. Nonetheless, the monocyte´s responses to SEC EVs were comparable to EVs UC. We conclude that the additional sample preparation steps are informative but increase the risk of contamination. Decent EV amounts are hardly feasible to obtain for encapsulated, non-hypervesiculating S. pyogenes strains and may not cover the entire size spectrum of EVs present in culture supernatants, as is the case with ultracentrifugation.

Monocytes are usually short-lived cells, that rapidly undergo apoptosis through caspase-3 activation in the absence of adequate survival signals (Fahy et al, 1999; Goyal et al, 2002). We provide evidence that cleavage of caspase-3 is abrogated when monocytes are stimulated with LTA derived from either Spy EVs (UC and SEC) or EV-depleted supernatants. In addition, we found phosphorylation of the MAP kinase p44/42 (ERK1/2), previously shown to promote monocyte survival and differentiation (Bianchi et al, 2007; Farzam-Kia et al, 2023). Interestingly, TLR2 has been demonstrated to induce selective autophagy in an ERK1/2-dependent manner (Anand et al, 2011; Chang et al, 2013; Lu et al, 2017). These reports are consistent with our findings of increased LC3-II turn over upon Spy EV and LTA treatment. Lastly, we observe that IL-6 and particularly IL-1β secretion in response to Spy EVs highly correlates with the LTA content in our EV preparations. Overall, we find free and vesicular Spy LTA promoting IL-1β release while inhibiting apoptotic and pyroptotic cell death mechanisms. Since LTA has been demonstrated to induce antibody secretion and memory B cells (Yi et al, 2024) as well as dendritic cell maturation (Wesa and Galy, 2001; Luft et al, 2002), we speculate that vesicular LTA may serve as a “booster” to establish a humoral immune response. As we have previously shown IgG-immune reactive epitopes on Spy EV components (Resch et al, 2016), LTA-deficient S. pyogenes may be useful for follow-up experiments to investigate whether other factors within Spy EVs exhibit immunomodulatory properties.