Abstract

Background

Patients with primary brain tumors navigate a devastating diagnosis and cognitive and physical decline. Available educational materials should be easily comprehensible, informative, reliable, culturally sensitive, and patient oriented.

Methods

We assessed websites of major brain tumor centers in the United States and patient organizations for readability using multiple calculators, quality and reliability using DISCERN and JAMA tools, and cultural sensitivity using the Cultural Sensitivity Assessment Tool scale. We determined whether sites addressed practical, emotional, social, and spiritual needs of a patient. Brain tumor centers were categorized based on NCI-designation and fulfillment of Guiding Principles developed by the American Brain Tumor Association.

Results

Websites of 91 brain tumor centers and 8 patient organizations were examined. Fewer than 10% of brain tumor centers’ websites were readable at an eighth-grade level. There was no significant difference in readability between brain tumor centers and patient organizations. Patient organizations outperformed brain tumor centers on both quality measures, with no differences seen based on the category of centers. Only 48% of brain tumor centers and 63% of patient organizations scored at recommended levels on all cultural sensitivity scales. Most patient organizations, but few brain tumor centers, addressed practical, social, emotional, and spiritual needs.

Conclusions

Publicly available brain tumor education materials are frequently at a high reading level. Quality and cultural sensitivity can be improved by citing sources, describing treatment risks, describing outcomes without treatment, addressing quality of life during treatment, addressing myths, and visually representing more patients. Patient organizations can provide models for addressing patient needs.

Keywords: brain tumors, cultural sensitivity, patient education, quality, readability

Key Points.

Fewer than 10% of brain tumor centers’ websites are readable at an eighth-grade level.

Educational websites by patient organizations have higher quality than those of most major brain tumor centers.

The majority of patient organizations, unlike major brain tumor centers, addressed patient practical, emotional, and spiritual needs.

Importance of the Study:

Patients diagnosed with a primary tumor must navigate complicated healthcare while coping with cognitive and physical decline. Therefore, accessible patient education is critically important for this patient population. Online educational materials for cancer patients are rarely understandable at the eighth grade reading level, and vary on quality, reliability, and cultural sensitivity. To evaluate the materials for brain cancer patients, we used standardized tools on readability, quality, and cultural sensitivity on websites of major brain tumor centers and patient organizations. Our results showed major brain tumor centers to be rarely readable at an eighth-grade level, patient organizations to perform better on quality, reliability, and patient needs, and variation in cultural sensitivity. To begin improving accessibility, educational materials can use patient organizations as a model. However, all sites can address accessibility by using clear language, incorporating inclusive visuals, including more information on treatment options and on nontreatment related issues, and discussing cultural beliefs on cancer.

Eighty-five thousand people are diagnosed with primary brain tumors each year in the United States,1 and 29% of these individuals are receiving a cancer diagnosis, which carries the additional weight of involved treatment plans and an average 5-year survival of 36%.1 Patient education is a critical component of informed treatment decision-making, yet there are no standardized resources to ensure high-quality education.

Patients’ educational backgrounds, health literacy, cultural expectations, and emotional responses vary significantly, so a range of reliable materials would benefit the greatest number of patients and families.2 Additionally, patients diagnosed with brain tumors are more likely to need multiple formats of information due to sensory or cognitive challenges.3 ReFaey et al. estimated that only 22% of YouTube videos about brain cancer contain reliable, high-quality information.4 Other studies have found that publicly available brochures and online information on brain tumors are rarely understandable at the sixth-grade reading level, but one of these is from over 10 years ago and the other looked at sites based on Google searches not limiting to major brain tumor centers and organizations.5,6 Brain tumor educational materials published by major brain tumor centers perform similarly. One study, from over 5 years ago, concluded NCI designated cancer centers disperse educational materials at a grade level well above the recommended reading level, though it did not look at patient organizations or major brain tumor centers that are not NCI designated.7 Currently, the format and content of publicly available brain tumor educational materials published by major brain tumor centers varies widely. However, it is unknown whether the readability, quality, and reliability are associated with the level of cancer center accreditation. Patient organizations also publish their own publicly available resources with varying layouts and messages but have not yet been compared with major brain tumor centers.

In addition to literature gaps on the structure of publicly available material on brain tumors, there is also little information on the content of such material. A systematic analysis assessing the challenges faced by brain metastasis patients and their families revealed that there was insufficient emphasis on support services.8 Both patients and caregivers have been shown to benefit from social, emotional, and spiritual support—yet, the adequacy of educational materials and practices regarding these services have not been extensively researched.9 It is unknown how well these brain tumor centers address patient needs. If patients found these vetted websites to be readable, reliable, supportive, and culturally sensitive, they would be less likely to search for additional sources that could contain misinformation.4

The cultural sensitivity and patient needs addressed by brain cancer educational materials have not yet been addressed to our knowledge, and readability and quality analysis have never been narrowed to materials published by credible major brain tumor centers and patient organizations.2,5 Our study seeks to identify best practices and create recommendations so that publicly available resources can meet patients’ and caregivers’ needs. We not only assess the readability but also the discussion on treatment options, credibility, support services, and cultural sensitivity of both major brain tumor centers and patient organizations.

Methods

Site Selection and Categorization

We aimed to identify major brain tumor centers whose websites patients may trust for information, starting with the list of centers on the American Brain Tumor Association’s (ABTA) website, accessed on June 11, 2024.9 The ABTA identifies 7 Guiding Principles for adult CNS tumor treatment centers: Dedicated Program for CNS tumor patients, Patient Volume of at least 40 adults per year, Multidisciplinary Team, Molecular Testing, Clinical Trials, Tumor Board, and Clinical Supportive Services & Resources.10 Centers were sorted by number of Guiding Principles met, NCI designation status, and website format.9 We included all centers that met 7/7 Guiding Principles or were NCI designated. The senior author (A.L.C.) also reviewed the list and added additional centers that have national reputations for brain tumor care. Major national patient organizations were included in this study because they were referenced by major brain tumor centers’ websites (Supplementary Table S2).

The centers’ websites were then classified for formatting. The sites were categorized based on their general format. If a website did not match a category, a new category was created to describe the format, resulting in 5 final format types in which websites were organized. Websites were categorized as having only one page addressing both tumor types and treatment (Tumors/Treatments); having one page for tumor types and a separate page for treatment (Tumors + Treatments); having one page for tumor types, one separate page for treatments, and a separate page for diagnosis (Types/Symptoms + Diagnosis + Treatments); having a page only for treatments rather than tumor types (Treatments Only); or having individual pages with all the details on each tumor type (Divided by Cancer Type). Whether each website included videos, patient quotes, and physician quotes was also documented.

Material Assessment

Each webpage was assessed by two independent reviewers (J.N. and L.S.) for readability, quality, discussion of patient needs, and cultural sensitivity. Each scale (all 5 readability scores, DISCERN, JAMA Benchmark, and Cultural Sensitivity Assessment Tool [CSAT]) was selected based on previous literature evaluating patient education materials for cancer patients.2,5 The categorical data were discussed until both reviewers agreed, and the ordinal data (DISCERN and CSAT Likert scale scores) were reviewed by all 3 authors and independently rescored by discussion between J.N. and L.S. if their scores differed by more than 2 points. Both the ordinal and numerical (readability scores) data from both reviewers were averaged before statistical analysis.

Readability

Readability was evaluated using the following validated tools: Flesch Reading Ease Index (FRE), Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level (FKG), Gunning-Fog Score (GFS), Simple Measure of Gobbledygook (SMOG), and Coleman-Liau Index (CLI).11 An online readability calculator was used to insert randomly sampled text from each site.12 The FRE is scaled from 1 to 100—100 being the most difficult—and determines the difficulty of text by syllables per word and words per sentence. The FKG is similar but is scaled from 1 to 12 to represent the academic grade level at which the text would be comprehensible. This tool was used to determine the percentage of sites that were at a maximum reading level of eighth grade.13 The GFS also provides a grade-level score but does so by considering complex words or words with more than 3 syllables.14 The SMOG calculates a grade-level score that similarly determines complexity but uses an alternate mathematical formula.15 Lastly, the CLI determines a grade-level score using characters rather than syllables of words to calculate readability.16 Although these tools yield similar results, calculating all 5 simultaneously allowed for a comprehensive assessment of readability and has been applied to other cancer educational materials.17,18

Quality

The educational quality of each site was evaluated using the DISCERN tool and JAMA benchmark. DISCERN is a 16-question questionnaire that assesses the quality of written information on treatment choices.19,20 The first 8 questions gauge whether the information is reliable. The next set of questions aims to determine the level of detail on the treatments, such as whether the text discusses risks, benefits, uncertainty, and quality of life. The total number from the first 15 questions was averaged for each site and listed as the quantitative score, which can range from 15 to 75. The final question is the overall rating based on the rater’s judgment and preceding answers and is listed as the qualitative score. The possible answers for these DISCERN questions range from 1 to 5 on a Likert scale, with 1 being No, 2 Mostly No, 3 Neutral, 4 Mostly Yes, and 5 being Yes. The JAMA benchmark specifically assesses reliability based on the presence of the following 4 criteria: authorship, references, financial disclosures, and date of publication or review. An average value of 0–4 was determined for each site.21

Patient needs

Patient needs were divided into 4 domains: practical, emotional, social, and spiritual.9 Practical needs were defined as whether the site discussed how brain cancer affected one’s daily life. Emotional needs were defined as an acknowledgement of the difficult emotions associated with brain cancer, such as stress and grief. Social needs pertained to addressing how brain cancer impacts one’s relationships. Spiritual needs were defined as sharing support services or strategies for navigating one’s spiritual journey. Each site was assessed for either fulfilling or not fulfilling each of these domains.

Cultural sensitivity

The Cultural Sensitivity Assessment Tool assesses the cultural sensitivity, or how aware the centers were of the racial and ethnic diversity of their audience, of cancer educational materials specifically.22 This is accomplished by a questionnaire with answers as 0 (Not Applicable) or 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 4 (Strongly Agree). The questionnaire is divided into 3 categories: format, written message, and visual message. Format pertains to how well the information is organized and clear to the audience; written message considers how receptive the audience would be to the information such as by asking questions on how understandable the medical jargon is; visual message applies to how pictures and videos present on the webpage align with cultural norms and are culturally appropriate. The mean was calculated for each category and was determined as culturally acceptable if it was above the value 2.5.23 To further ascertain the extent to which sites took into consideration their diverse audience, an additional checklist was used.24 The checklist included the following 3 questions: Is a racial or ethnic group described as high-risk? Does information address cultural perceptions of cancer? Is complementary medicine presented as a potential adjunctive treatment, for example for symptoms?

Statistical Analysis

The mean and standard deviation for readability, DISCERN, JAMA, and CSAT scores were reported. One-way ANOVA tests were used to compare average scores for continuous variables across the 5 site categories. Chi-square tests were used to compare categorical variables, such as the proportions of sites with videos, patient quotes, and patient quotes. Independent samples t-test compared average scores between the brain tumor centers and patient organizations. This test was also applied to those who had a maximum eighth grade reading level, fulfilled patient needs, met a CSAT score above 2.5, and answered yes to the additional cultural sensitivity questions. For interrater reliability between the reviewers, a correlation coefficient was calculated for the readability scores and quadratic weighted Cohen’s Kappa was applied to each individual question from DISCERN, JAMA, and CSAT. Statistical significance was determined by a level of 0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 29.0.2.0.

Results

We included a total of 91 centers, and 39 centers were included for meeting all 7/7 ABTA Guiding Principles, an additional 39 centers were included for being NCI designated, and 13 additional centers were included based on reputation. The publicly available sites published by the 91 centers and 8 patient organizations were organized by format (Table 1). The majority of patient organizations’ sites were organized into a few pages, one for each of the 3 following categories: cancer types/symptoms, diagnosis, and treatment options (“Types/Symptoms + Diagnosis + Treatments”). A quarter of the major brain tumor centers’ sites had a single page addressing both tumors and treatments (“Tumors/Treatments”), while another quarter had a separate page for each tumor type (“Divided By Cancer Type”). A minority of sites had two pages: one for tumors and one for treatments (“Tumors + Treatments”).

Table 1:

General characteristics of the included websites based on the properties of the center and the organization of the website.

| All Centers | NCI Designated + 7 Principles | Only 7 Principles | Only NCI Designated | Neither NCI Designated Nor 7 Principles Met | Patient Organizations | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 91 | n = 23 | n = 16 | n = 39 | n = 13 | n = 8 | ||

| Types/Symptoms + Diagnosis + Treatments | 17 (18.68%) |

6 (26.09%) |

2 (12.5%) |

6 (15.38%) |

3 (23.08%) |

5 (62.50%) |

.153 |

| Tumors + Treatments | 18 (19.78%) |

5 (21.74%) |

4 (25.00%) |

6 (15.38%) |

3 (23.08%) |

0 (0.00%) |

|

| Tumors/Treatments | 23 (25.27%) |

4 (17.39%) |

4 (25.00%) |

9 (23.08%) |

6 (46.15%) |

2 (25.00%) |

|

| Treatments Only | 9 (9.89%) |

1 (4.35%) |

2 (12.5%) |

6 (15.38%) |

0 (0.00%) |

0 (0.00%) |

|

| Divided By Cancer Type | 21 (23.08%) | 7 (30.43%) |

4 (25.00%) |

10 (25.64%) |

0 (0.00%) |

1 (12.50%) |

|

| Other | 3 (3.30%) |

0 (0.00%) |

0 (0.00%) |

2 (5.13%) |

1 (7.69%) |

0 (0.00%) |

|

| % with video | 50 (54.95%) |

11 (47.83%) |

11 (68.75%) |

20 (51.28%) |

8 (61.54%) |

6 (75.00%) |

.499 |

| % with quotes from patients | 49 (53.85%) |

9 (39.13%) |

10 (62.5%) |

24 (61.54%) |

6 (46.15%) |

4 (50.00%) |

.439 |

| % with quotes from healthcare provider | 54 (59.34%) |

14 (60.87%) |

12 (75.00%) |

23 (58.97%) |

5 (38.46%) |

5 (62.50%) |

.401 |

Forty-four percent of the websites did not provide any videos. Of those who provided videos, 53% were either patient testimonials or promotional videos for services provided by a center, and 9% of sites with videos only provided educational webinars, and only 38% had patient-centered educational videos (Table 1).

On all measures of readability and quality (including CSAT, DISCERN, and JAMA benchmark), there was no statistically significant difference between the subgroups of major brain tumor centers (based on NCI designation and ABTA principles met) or between the 8 patient organizations. The individual readability, DISCERN, and JAMA benchmark scores for each subgroup are detailed in Table 2. Only 9.89% of all major brain tumor centers achieved an eighth grade reading level on their websites, and no patient organization achieved an eighth grade reading level. The correlation coefficient between reviewers was strong, ranging from 0.797 to 0.839 for each readability score, except for Coleman-Liau, which had a moderate correlation of 0.630. There was also no notable difference in the average DISCERN qualitative scores across groups. However, the DISCERN quantitative score and JAMA benchmark score were significantly higher (better) for patient organizations than for brain tumor centers, with P = .002 and P = .037, respectively (Figure 1). Cohen’s Kappa demonstrated variable interrater reliability, ranging from minimal to almost perfect agreement. However, the majority of individual questions had at most 1-point difference between raters (Supplemental Table S3).

Table 2:

Readability + Quality of all websites and websites by the properties of the center.

| All Centers | NCI Designated + 7 Principles | Only 7 Principles | Only NCI Designated | Neither NCI Designated Nor 7 Principles Met | Patient Orgs. | P-value | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 91 | n = 23 | n = 16 | n = 39 | n = 13 | n = 8 | ||||||||

| Readability Score | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| FK Reading Ease | 47.27 | 10.94 | 45.10 | 11.52 | 44.73 | 8.90 | 49.02 | 10.63 | 49.00 | 12.91 | 53.46 | 7.11 | .233 |

| FK Grade Level | 11.07 | 2.10 | 11.55 | 2.15 | 11.43 | 1.59 | 10.77 | 2.14 | 10.67 | 2.41 | 10.36 | 1.46 | .419 |

| Gunning Fog Score | 13.79 | 2.32 | 14.25 | 2.40 | 14.10 | 1.63 | 13.52 | 2.42 | 13.43 | 2.64 | 13.14 | 1.66 | .610 |

| SMOG Index | 10.10 | 1.69 | 10.39 | 1.72 | 10.39 | 1.21 | 9.90 | 1.77 | 9.83 | 1.93 | 9.50 | 1.19 | .556 |

| Coleman Liau Index | 13.90 | 1.37 | 14.07 | 1.42 | 14.24 | 1.10 | 13.65 | 1.32 | 13.91 | 1.71 | 12.66 | 1.10 | .073 |

| % with eighth grade reading level | 9.89% | 8.7% | 0% | 12.82% | 15.38% | 0% | .508 | ||||||

| Discern (qualitative) | 3.24 | 0.82 | 3.17 | 0.86 | 3.16 | 0.85 | 3.35 | 0.77 | 3.12 | 0.89 | 4.13 | 0.88 | .054 |

| Discern (quantitative) | 46.48 | 7.00 | 46.41 | 7.80 | 46.13 | 7.47 | 47.28 | 6.48 | 44.65 | 6.90 | 57.13 | 6.48 | .002* |

| JAMA Benchmark | 0.49 | 0.87 | 0.39 | 0.78 | 0.84 | 1.01 | 0.44 | 0.87 | 0.42 | 0.86 | 1.38 | 0.83 | .037* |

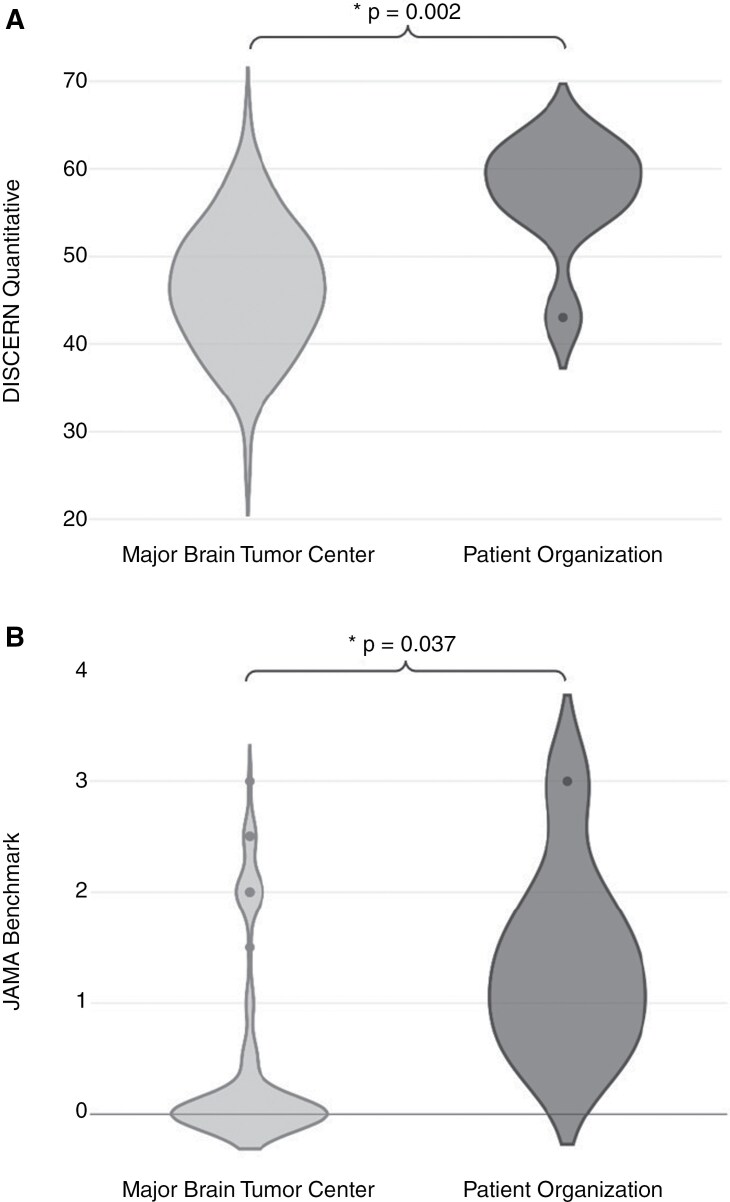

Figure 1.

(A) Violin plot showing distribution of quantitative DISCERN scores. (B) Violin plot showing distribution of JAMA benchmark scores. Both panels compare scores from major brain tumor centers (light gray, right) versus patient organizations (dark gray, left) and denote a statistically significant difference between major brain tumor centers and patient organizations with a bracket.

Specifically, the patient organizations scored statistically significantly better than the major brain tumor centers in terms of both main quality-evaluating scores: qualitative DISCERN and JAMA benchmark. Within the JAMA benchmark, the main criterion met significantly more often by the patient organizations was attribution, met by clearly citing sources and references. None of the sites achieved all 4 benchmarks. The specific DISCERN criteria met significantly more frequently by the patient organizations are detailed in Figure 2. There was a single DISCERN criterion in which the major brain tumor centers significantly outscored the patient organizations: explaining that there may be more than one available treatment choice.

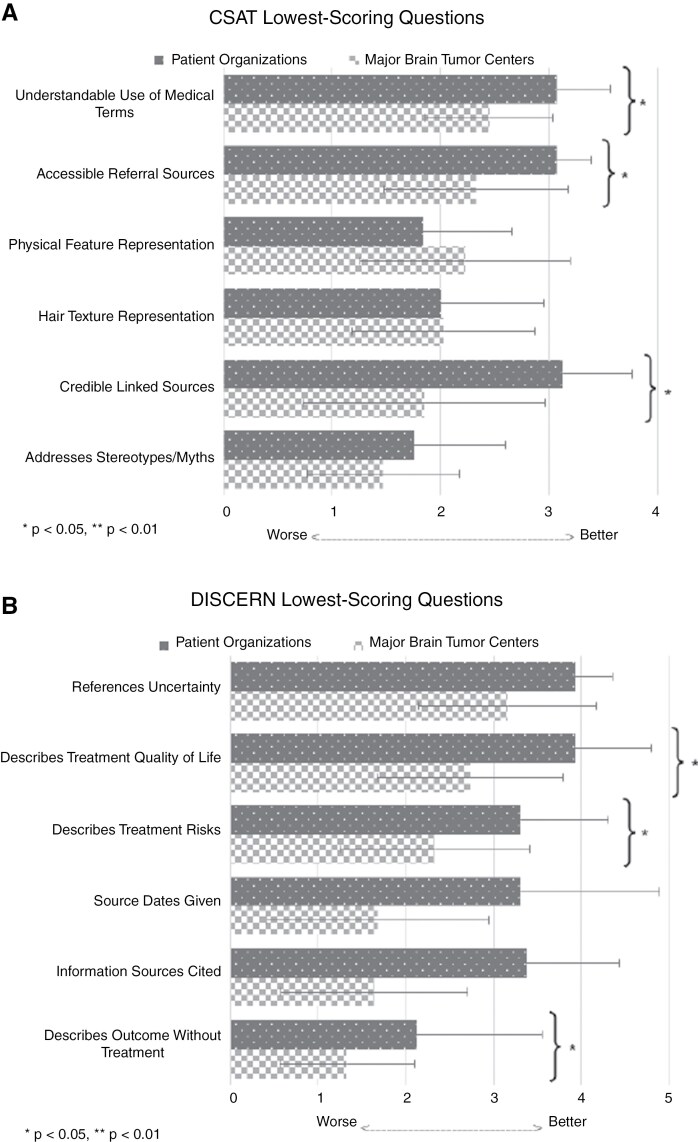

Figure 2.

(A) Bar graph showing average scores for each of the 6 lowest-scoring questions from CSAT. (B) Bar graph showing average scores for each of the 6 lowest-scoring questions from the DISCERN tool. Both panels compare the average scores of major brain tumor centers (checked bars) and patient organizations (dotted bars) for each question. Questions with a statistically significant difference between major brain tumor centers and patient organizations are denoted with a bracket.

On average, centers scored highest on CSAT format questions and lowest on CSAT visual message, as detailed in Table 3. No centers discussed cultural stereotypes about cancer, and 90% of centers did not address myths such as perceived associations between microwaves or cell phones and cancer. Other CSAT criteria, such as linking credible sources, representing a variety of hair textures in pictures, and accurately representing cancer patients’ physical features, were more split (standard deviations of 1.1, 1.2, and 1.3, respectively) such that most centers either accomplished the goal with an average score ≥2.5 or did not attempt to address them. All centers attempted to include accessible referral sources and use understandable medical terms because no centers scored a zero on these criteria. However, only 45% met the goal score of ≥2.5 for accessible referral sources, and 60% met the goal for use of understandable medical terms. One reason for the low scores for accessible referral sources was that many sites’ only sources were hyperlinks to other pages within their website or organization, which decreased their credibility compared with primary sources when all pages lacked citations. The main reason for low scores on understandable medical terms was the widespread use of medical jargon without available definitions. The patient organizations performed significantly better on both of these criteria than the major brain tumor centers (P < .001 for accessible sources and P = .009 for understandable terminology).

Table 3:

Cultural Sensitivity of all websites and websites by the properties of the center.

| All Centers | NCI Designated + 7 Principles | Only 7 Principles | Only NCI Designated | Neither NCI Designated Nor 7 Principles Met | Patient Orgs. | P-value | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 91 | n = 23 | n = 16 | n = 39 | n = 13 | n = 8 | ||||||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | S D | Mean | SD | ||

| CSAT Format | 3.27 | 0.25 | 3.24 | 0.33 | 3.30 | 0.23 | 3.31 | 0.20 | 3.21 | 0.25 | 3.22 | 0.21 | .646 |

| % over 2.5 | 95.74% | 95.65% | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% | .503 | ||||||

| Written Message | 2.62 | 0.25 | 2.68 | 0.24 | 2.68 | 0.31 | 2.59 | 0.26 | 2.53 | 0.17 | 2.90 | 0.14 | .009* |

| % over 2.5 | 59.34% | 69.57% | 62.50% | 53.85% | 53.85% | 100.00% | .175 | ||||||

| Visual Message | 2.19 | 1.12 | 2.22 | 1.23 | 2.18 | 1.19 | 2.12 | 1.07 | 2.34 | 1.06 | 2.79 | 0.21 | .625 |

| % over 2.5 | 62.64% | 65.22% | 62.50% | 58.97% | 69.23% | 87.50% | .887 | ||||||

| Qualitative Score | 2.68 | 0.47 | 2.67 | 0.49 | 2.75 | 0.37 | 2.64 | 0.47 | 2.73 | 0.60 | 2.81 | 0.26 | .850 |

| % over 2.5 | 48.35% | 47.83% | 50% | 48.72% | 46.15% | 62.50% | .959 | ||||||

| % describing a racial or ethnic group as high-risk | 5.49% | 4.35% | 0% | 10.26% | 0% | 25.00% | .137 | ||||||

| % addressing cultural perceptions of cancer | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | N/A | ||||||

| % presenting complementary medicine as an acceptable form of treatment |

32.97% | 13.04% | 43.75% | 38.46% | 38.46% | 62.5% | .081 | ||||||

Only 8% of centers adequately described expected patient outcomes without treatment, and only 19% cited information sources and dates clearly (as determined by an average score ≥2.5). Patient organizations were significantly better at citing information sources and dates of publication (P = .002 and P = .022, respectively). The DISCERN criteria of describing treatment risks and quality of life were widely attempted but had low average scores across all centers of 2.33 and 2.73, respectively. These low scores were primarily attributed to vague descriptions of quality of life and overemphasis of treatment benefits compared with risks. Patient organizations addressed both quality of life and treatment risks significantly more than major brain tumor centers (Figure 2B).

An additional analysis was performed to compare how readability, quality, and cultural sensitivity varied by format of the website. The JAMA, qualitative and quantitative DISCERN, and CSAT were significantly different across format types (P < .001). Upon pairwise comparison, websites that had a “Treatments Only” format had significantly lower scores compared with other formats.

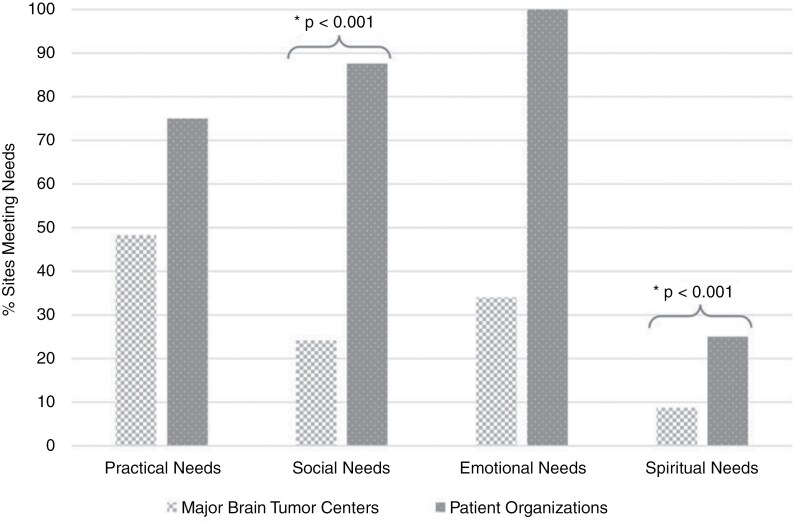

Fifty-two percent of major brain tumor centers’ sites did not address any patients’ needs, while 100% of patient organizations’ sites addressed at least 1 patient need, as shown in Figure 3 (Supplementary Table S1). Patient needs were most often addressed by advertising a center or organization’s specific programs, including support groups and palliative care offerings. Less often, it was only noted that symptoms and side effects can affect patients’ daily lives (effectively addressing practical needs) within guidebooks, symptom pages, or treatment pages.

Figure 3.

Bar graph showing the percent of major brain tumor centers (checked bars) and patient organizations (dotted bars) meeting each of the four needs (practical, social, emotional, and spiritual). Needs with a statistically significant difference between major brain tumor centers and patient organizations are denoted with a bracket.

The CSAT Format score (min 2.5, max 3.75), which reflects the organization and clarity of information, was not statistically significant across groups; 100% of the centers and patient organizations achieved a score of 2.5 or greater. The CSAT Written Message score (min 2.11, max 3.30) was markedly varied between groups (P < .009). Patient organizations had a higher average score of 2.90 in comparison to brain tumor centers’ score of 2.62 (P < .001). All patient organizations had a minimum score of 2.5, indicating desired cultural sensitivity, whereas only 59.34% of brain tumor centers met the minimum written message score (P = .026). The CSAT Visual score (min 0, max 3.74) was not different across groups, but only 62.64% achieved a score above 2.5. The CSAT interrater reliability was similarly variable for CSAT, but the majority of answers had a maximum 1-point difference in score.

No center or patient organization addressed cultural perceptions of cancer. While 32.97% of brain tumor centers did present complementary medicine as a potential adjunctive treatment, 62.5% of patient organizations did. For all websites that included them, complementary medicine treatments were presented in the context of symptom management and not tumor directed. Only 5.49% of centers described a racial or ethnic group as a high-risk population, whereas 25% of patient organizations accomplished this (P = .039).

Discussion

Although brain tumor education websites succeed at defining clear aims and describing multiple treatment options, notable deficits remain, and 90.11% of brain cancer educational materials published by major brain tumor centers and patient organizations were not readable for eighth grade level readers. Despite minor variability among scores, all scoring systems concluded that the readability of these materials was not sufficient for the average American reader, and the average Flesch-Kincaid Reading Level for all sites was 11.5,6 The quality of educational materials published by major brain tumor centers was significantly lower than that of those published by patient organizations.20,21 Most major brain tumor centers could benefit by following the examples provided by some patient organizations in describing treatment risks, outcomes without treatment, and quality of life during treatment. However, both centers and organizations could benefit from adding more descriptions of the risks of receiving versus abstaining from treatment in more depth, citing sources, and adding update dates.

Similarly, although minimally acceptable levels of cultural sensitivity were achieved by most major brain tumor centers and patient organizations, room for improvement exists. For example, patient organizations scored significantly higher (2.90) than brain tumor centers (2.62) on the CSAT’s written message portion. In turn, patient organizations could serve as a model for centers on how to adequately clarify medical jargon and address stereotypes and myths such as all brain tumors have a poor prognosis. Given only 62.64% of sites received a score above 2.5 on the CSAT visual portion, more sites can aim to better represent the cultural and racial diversity of patients in their pictures and videos.

Our findings share similarities with published reports on educational materials on other cancers. For example, assessments of online educational material on breast cancer and prostate cancer similarly exceed the eighth grade reading level.25,26 These results are concerning because low health literacy is a recognized social determinant of health.27 By complicating reading materials that serve to help patients navigate the complex and alarming nature of cancer, cancer centers are inadvertently furthering healthcare disparities. This further emphasizes that readability must be addressed, especially in the context of cognitive limitations associated with brain cancer. The readability tools assess word and sentence length and complexity, so cancer institutions can revise their writing to be simple, short, and straightforward in an effort to be more accessible. After revision, publicly available readability calculators can be used to assess the degree of improvement.12

The quantitative DISCERN score for major brain tumor centers is comparable to other evaluations of websites with cancer educational materials. For example, laryngeal cancer sites also reported an average quantitative DISCERN score of 50,28 whereas adult kidney cancer had an average score of 42.29 Interestingly, these scores were evaluated from websites found on search engines rather than cancer center sites themselves. This similarity in scores highlights that despite the national credentials attributed to major brain tumor centers, they demonstrate similar reliability as other information found on the Internet. Moreover, the lack of differences between centers that are NCI designated, achieve 7 Principles Met, both, or neither also suggests that credentials does not imply better educational materials.

Both an assessment of online educational materials on eye cancer and thyroid cancer found that no site was able to meet all four criteria of JAMA, similar to our study.30,31 In other words, sites are not able to exhibit consistent reliability beyond credentials, and the shortcomings and variability of reliability on cancer educational materials can contribute to compromised patient trust. These findings are replicated on an international scale, with low quality and reliability of online educational materials on brain tumors in China as well.32

Given the diverse population of brain cancer patients who come from all cultural and ethnic backgrounds, culturally sensitive educational materials are necessary to reach all intended audiences. Studies on breast cancer and prostate cancer demonstrate a similar assessment of limited cultural sensitivity using CSAT.26,33 Our assessment of specific questions highlights that barely any sites describe a racial or ethnic group as high-risk. However, this was accomplished by a few sites when they addressed how gliomas are more common in White people while meningiomas are more common in Black people. No center or site addressed cultural perceptions of cancer. The stigma and shame behind cancer prevails in certain cultures, and some attribute cancer to the “evil eye” rather than to scientific reasons.34 By addressing cultural conceptions, patients can avoid isolation and seek care earlier.35

In addition to getting information about healthcare, patients must be informed about how their cancer diagnosis will affect their life such as everyday tasks, social relationships, employment, and spirituality. Like our assessment on patient needs, studies on brain metastases rarely, if ever, address these needs.9 Instead, they focus on symptoms, treatment, and prognosis. However, patients with a primary brain tumor have expressed the importance of support, whether it be through an empathetic physician, social support, and religion as they progress through cognitive decline.36,37

This study used several validated tools to simultaneously evaluate the readability, quality, and cultural sensitivity of 91 different educational websites for patients with brain cancer. Only 2 independent reviewers evaluated these sites, and many of the questions posed by the DISCERN and CSAT tools were subjective. Despite these limitations, the majority of answers between the 2 independent reviewers were within one point for each question within each tool (Supplementary Table S3). Some of the interrater reliability by Cohen’s Kappa was limited by the Kappa paradox due to the small range of numerical answers for each question. The formats of the websites evaluated for this project varied widely, especially in the number of webpages dedicated to each topic and the organization of navigation tabs to reach each page. Due to this heterogeneity in formatting, direct comparisons between pages were difficult to make, and certain pages may have been missed during website navigation, which would have negatively impacted a site’s score.

One strength of this study was categorizing the formatting differences to both reduce the impact of this heterogeneity and determine whether there were broad formatting differences between the different types of publishers. The wide variations in the level of detail dedicated to different topics (such as treatment versus symptoms) were not reflected in the answers to the quality or cultural sensitivity screening questions, but we noticed a distinct difference in detail based on the different website organization styles. In contrast to the general heterogeneity among sites, two different major brain tumor centers used the NCI’s Physician Data Query as their main educational material, so they both received the same scores. The final limitation was the small sample size of 8 patient organizations compared with 91 major brain tumor centers, although we believe this ratio is relatively representative of the overall number of brain tumor centers compared with patient organizations.

While institutions may not intend to be thoroughly comprehensive, having websites with information on brain tumors has an inherently educational purpose, especially when patients and their families use this information to make informed decisions. Although institutions will vary in the depth of information presented, all patient facing information should be readable, have evidence of reliability, be culturally sensitive, and be aware of interests of patients. This study subjects the publicly available information to baseline standards of readability, accuracy, and cultural sensitivity, regardless of the level of detail. We found low levels of readability and compliance with standards of evidence of reliability across sites and variability in cultural sensitivity and patient-centeredness. In summary, brain tumor centers and patient organizations can prioritize readability by simplifying language and utilizing educational videos; improve quality by citing sources and elaborating on treatment; enhance cultural sensitivity through diverse visual representations and addressing cultural perceptions of cancer; and better meet patient needs by providing resources alongside practical guidance. To help enhance the accessibility and effectiveness of online educational materials, we have created a table with a list of specific recommendations (Table 4) for brain tumor centers and patient organizations to incorporate and ultimately provide the best support for a patient living with a brain tumor.

Table 4:

Recommendations for sites to improve readability, quality, cultural sensitivity, and address patient needs.

| Readability | • Create more patient-centered educational videos explaining pathophysiology, diagnoses, treatments, and symptom management rather than solely presenting patient testimonials or advertisements for the center. • Use publicly available readability calculators to ensure content is at an eighth grade reading level or lower (6th grade reading level is ideal). • Replace medical jargon with simple, accurate terminology (eg, use “swelling” instead of edema or “X-ray” instead of radiograph). • Use shorter sentences and bullet points for better comprehension. • Provide glossaries or hover-over definitions for necessary medical terms. |

| Quality | • Cite primary sources (eg, peer-reviewed journals, government health organizations) and include publication/update date. • Clearly describe risks and benefits of receiving vs abstaining from treatment (eg, “Abstaining from surgery may avoid risks of a brain procedure such as infection, bleeding, and damage to healthy brain tissue, but the tumor may continue to grow and worsen symptoms such as seizures, cognitive decline, and loss of motor and/or sensory function.”). • Include survival rates and potential quality of life outcomes based on evidence. • Explain potential side effects of treatments in simple language with real life examples. |

| Cultural Sensitivity | • Include images and videos that depict patients of different races, ethnicities, genders, and ages. • Address cultural perceptions (eg, in some cultures, cancer is considered to be caused by the “evil eye” or eating) and myths (eg, “brain tumors are caused by cellphones”) surrounding brain tumors. • Provide multilingual resources or easy-to-use translation features for non-English speakers. • Acknowledge health disparities (eg, minority and low-income populations are more likely to experience delays in receiving treatment). • Discuss how certain racial or ethnic groups may have different risks (eg, Gliomas are more common in White populations, while meningiomas are more common in Black populations). |

| Patient Needs | • Provide emotional and psychological support resources, including links to patient and caregiver support groups. This could also include contact information and/or meeting times for groups or links to social media communities. • Provide information on cognitive changes and how patients can adapt (eg, patients may experience difficulties with memory, concentration, or slower processing time but they can use calendars, reminder apps, structured routines and/or engage in brain stimulating activities such as puzzles and reading). • Address practical needs such as employment, transportation to treatment centers, and legal rights (eg, Family and Medical Leave Act, American with Disabilities Act). • Include patient stories that focus on practical and honest advice rather than solely focusing on inspirational testimonials. • Offer materials discussing spirituality related to illness, including faith-based coping strategies for those interested and/or description of purpose of hospital chaplain if available. |

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Joelle Nilak, School of Medicine, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, Virginia.

Lauren Spadt, School of Medicine, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, Virginia.

Adam L Cohen, Division of Oncology, Inova Schar Cancer Institute, Fairfax, Virginia.

Author contributions

J.N. and L.S. contributed to project conception, data acquisition, data analysis and interpretation, and writing and editing. A.L.C. contributed to project conception, data interpretation, and writing and editing.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

Funding

This work was funded in part by the Inova Summer Student Research Grant and the Inova Health foundation.

Data Availability

Data are available upon request.

References

- 1. Schaff LR, Mellinghoff IK.. Glioblastoma and other primary brain malignancies in adults: a review. JAMA. 2023; 329(7):574–587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Finnie RKC, Felder TM, Linder SK, Mullen PD.. Beyond reading level: a systematic review of the suitability of cancer education print and web-based materials. J Cancer Educ. 2010; 25(4):497–505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chieffo DPR, Lino F, Ferrarese D, et al. Brain tumor at diagnosis: from cognition and behavior to quality of life. diagnostics. Diagnostics (Basel, Switzerland) 2023; 13(3):541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. ReFaey K, Tripathi S, Yoon JW, et al. The reliability of YouTube videos in patients education for glioblastoma treatment. J Clin Neurosci. 2018; 55:1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ahmadi O, Louw J, Leinonen H, Gan PYC.. Glioblastoma: assessment of the readability and reliability of online information. Br J Neurosurg. 2021; 35(5):551–554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Langbecker D, Janda M.. Quality and readability of information materials for people with brain tumours and their families. J Cancer Educ Off J Am Assoc Cancer Educ 2012; 27(4):738–743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ammanuel SG, Edwards CS, Alhadi R, Hervey-Jumper SL.. Readability of online neuro-oncology-related patient education materials from tertiary-care academic centers. World Neurosurg. 2020; 134:e1108–e1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Maqbool T, Agarwal A, Sium A, et al. Informational and supportive care needs of brain metastases patients and caregivers: a systematic review. J Cancer Educ Off J Am Assoc Cancer Educ 2017; 32(4):914–923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Find a Brain Tumor Treatment Center. American Brain Tumor Association. Accessed July 20, 2024. https://www.abta.org/about-brain-tumors/treatments-side-effects/find-a-brain-tumor-center/ [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guiding Principles for Tumor Treatment Centers. Accessed January 8, 2025. https://www.abta.org/about-brain-tumors/treatments-side-effects/find-a-brain-tumor-center/guiding-principles-for-tumor-treatment-centers/ [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ley P, Florio T.. The use of readability formulas in health care. Psychol Health Med. 1996; 1(1):7–28. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Readability Test. WebFX. Accessed July 18, 2024. https://www.webfx.com/tools/read-able/ [Google Scholar]

- 13. Flesch RA. New readability yardstick. J Appl Psychol. 1948; 32(3):221–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gunning R. The Technique of Clear Writing. McGraw-Hill; 1952. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mc Laughlin GH. SMOG grading-a new readability formula. J Read. 1969; 12(8):639–646. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Coleman M, Liau TL.. A computer readability formula designed for machine scoring. J Appl Psychol. 1975; 60(2):283–284. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Choudhery S, Xi Y, Chen H, et al. Readability and quality of online patient education material on websites of breast imaging centers. J Am Coll Radiol. 2020; 17(10):1245–1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Miles RC, Baird GL, Choi P, et al. Readability of online patient educational materials related to breast lesions requiring surgery. Radiology. 2019; 291(1):112–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Charnock D, Shepperd S, Needham G, Gann R.. DISCERN. An instrument for judging the quality of written consumer health information on treatment choices. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1999; 53(2):105–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. DISCERN - Welcome to DISCERN. Accessed June 16, 2024. http://www.discern.org.uk/ [Google Scholar]

- 21. Silberg WM, Lundberg GD, Musacchio RA.. Assessing, controlling, and assuring the quality of medical information on the internet: caveant lector Et viewor—let the reader and viewer beware. JAMA. 1997; 277(15):1244–1245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Guidry JJ, Walker VD.. Assessing cultural sensitivity in printed cancer materials. Cancer Pract. 1999; 7(6):291–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cultural Sensitivity Assessment Tool Manual. Accessed June 17, 2024. https://www.texascancer.info/pcemat/contents.html [Google Scholar]

- 24. Friedman DB, Kao EK.. A comprehensive assessment of the difficulty level and cultural sensitivity of online cancer prevention resources for older minority men. Prev Chronic Dis. 2007; 5(1):A07. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Li Y, Zhou X, Zhou Y, et al. Evaluation of the quality and readability of online information about breast cancer in China. Patient Educ Couns. 2021; 104(4):858–864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Choi SK, Seel JS, Yelton B, et al. Prostate cancer information available in health-care provider offices: an analysis of content, readability, and cultural sensitivity. Am J Mens Health. 2018; 12(4):1160–1167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Pelikan JM, Ganahl K, Roethlin F.. Health literacy as a determinant, mediator and/or moderator of health: empirical models using the European health literacy survey dataset. Glob Health Promot. 2018; 25(4):57–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Narwani V, Nalamada K, Lee M, Kothari P, Lakhani R.. Readability and quality assessment of internet-based patient education materials related to laryngeal cancer. Head Neck. 2016; 38(4):601–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Alsaiari A, Joury A, Aljuaid M, Wazzan M, Pines JM.. The content and quality of health information on the internet for patients and families on adult kidney cancer. JCancer Educ Off J Am Assoc Cancer Educ 2017; 32(4):878–884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. van Ballegooie C, Wen J.. Assessment of online patient education material for eye cancers: a cross-sectional study . PLOS Glob Public Health. 2023; 3(10):e0001967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Doubleday AR, Novin S, Long KL, et al. Online information for treatment for low-risk thyroid cancer: assessment of timeliness, content, quality, and readability. J Cancer Educ. 2021; 36(4):850–857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Zhang R, Zhang Z, Jie H, et al. Analyzing dissemination, quality, and reliability of Chinese brain tumor- related short videos on TikTok and Bilibili: a cross-sectional study. Front Neurol. 2024; 15:1404038. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Gu JZ, Baird GL, Escamilla Guevara A, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of English language online patient education materials in breast cancer: is readability the only story? Breast (Edinburgh, Scotland). 2024; 75:103722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Jazieh AR, Alkaiyat M, Abuelgasim KA, Ardah H.. The trends of cancer patients’ perceptions on the causes and risk factors of cancer over time. Saudi Med J. 2022; 43(5):479–485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Daher M. Cultural beliefs and values in cancer patients. Ann Oncol. 2012; 23(Suppl 3):iii66–iii69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Cavers D, Hacking B, Erridge SE, et al. Social, psychological and existential well-being in patients with glioma and their caregivers: a qualitative study. CMAJ Can Med Assoc J. 2012; 184(7):E373–E382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Nixon A, Narayanasamy A.. The spiritual needs of neuro-oncology patients from patients’ perspective. J Clin Nurs. 2010; 19(15-16):2259–2370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon request.