Abstract

Heat shock proteins (Hsps) are central components of the cellular stress response and serve as the first line of defense against protein misfolding and aggregation. Disruption of this proteostasis network is a hallmark of neurodegenerative diseases, including tauopathies, a class of neurodegenerative diseases characterized by intracellular tau accumulation in neuronal and glial cells. Although specific Hsps are enriched in glial cells, and some have been shown to directly bind tau and influence its aggregation, the broader interplay between Hsps and tau remains poorly understood. In particular, it is unclear whether tau expression affects the heat shock response and whether this interaction is modulated in a sex-specific fashion. Here, we used a Drosophila model of tauopathy to examine both inducible and constitutive Hsp expression in response to heat stress in the context of glial tau expression. We found that Hsp expression displays sexually dimorphic expression patterns at basal levels and in response to heat stress. Moreover, tau expression in glia disrupts the normal induction of specific heat shock proteins following heat stress. This work provides new insight into how tau interacts with the cellular stress response and highlights sex-specific differences in Hsp regulation. Understanding these molecular connections is crucial to understanding how the presence of tau in glial cells influences the stress response and potentially contributes to tauopathy pathogenesis.

1. Introduction

Neurodegenerative diseases are primarily characterized by the accumulation of misfolded protein aggregates. A critical line of defense against producing these aggregates is the heat shock response, which activates a global network of molecular chaperones. , Heat shock proteins (Hsps), originally discovered in Drosophila and named for their critical response to heat stress, − are key components of this network. These chaperones maintain essential processes including: protein transport, non-native protein degradation, protein complex assembly, , protein metabolism, , and protein aggregate disaggregation. Disruptions in heat shock protein expression and function, therefore, have been implicated in several neurodegenerative disorders. −

Tauopathies are a broad class of neurodegenerative diseases defined by the pathological intracellular accumulation of the microtubule-associated protein, tau. These diseases, which include Alzheimer’s disease (AD), feature tau aggregation in both neuronal and glial cells. Glial tau pathology is often found in brain regions with neuronal tau pathology, , and while its exact role in disease progression remains unclear, it can be used as a diagnostic hallmark in specific tauopathies. , Animal models have demonstrated that glial tau expression can impair glial cell function, − yet the molecular mechanisms linking tau accumulation and glial dysfunction remain incompletely understood.

Glial cells express Hsps, and it is not yet clear whether the formation of fibrillar glial tau inclusions reflects a failure of the Hsp network. Several studies suggest that Hsps are involved in regulating tau function and turnover, particularly in preventing the aggregation of pathologically modified tau. , In response to proteasomal stress, chaperones, such as Hsp27, Hsp70/Hsp40/Hsp110, and Hsp90, are recruited to the cytoskeleton, where they can interact with tau. ,− Moreover, Hsp27 and Hsp70 are robustly expressed in glial cells and have been observed to localize with tau inclusions in glia. ,, Astrocytic Hsp27 is particularly upregulated in brain regions where neuronal tau tangles are prominent, , and may even be secreted from astrocytes to modulate inflammation and tau aggregation in neighboring neurons. These findings suggest that glial Hsps could influence tauopathy disease progression, but the relationship between glial tau accumulation and Hsp expression remains unclear.

Hsps are synthesized at elevated levels in response to cellular stress, and emerging evidence across organisms and tissues suggests that Hsps are differentially regulated between sexes. For example, in rodents, females display elevated levels of Hsp70, and decreased levels of Hsp27 and Hsp90, in heart tissue compared to males. In Drosophila, female flies exhibit greater thermotolerance than males, though the extent to which differential Hsp expression underlies this observation remains to be determined. Notably, small Hsp expression in Drosophila is developmentally regulated in a sex-specific and tissue-specific fashion, but our understanding of sex-specific Hsp regulation remains incomplete.

While sex-specific effects on the incidence of tauopathies have been described, − and Hsp dysregulation has been implicated in aging and tauopathies, − the intersection of sex and tau expression on Hsp dynamics remains poorly defined. To address this gap, we examined the expression of eight Hsps in response to early glial tau expression and heat stress in both male and female Drosophila. Our goal of this study was to uncover potential sex-specific regulation of the heat shock response in the context of both physiological and disease-related stress.

2. Results

2.1. Basal Expression of Heat Shock Proteins Reveals Sex- and Hsp-Specific Differences in Day 10 Control and Glial Tau-Expressing Flies

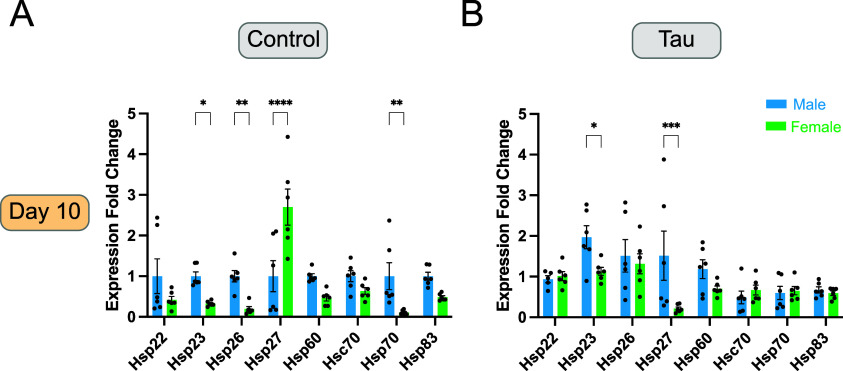

To assess basal (no heat stress) expression levels of Hsps and examine sex-specific differences, we performed qPCR gene expression analysis of eight Hsp genes in day 10 male and female control flies (Figure A). We used driver control flies (genotype: repo-GAL4, tubulin-GAL80 TS /+) for these analyses to allow for a direct comparison to the genetic background of glial tau transgenic flies (genotype: repo-GAL4, tubulin-GAL80 TS , UAS-Tau WT /+) previously established as a Drosophila model of glial tauopathy. , In control flies, females exhibited significantly reduced basal expression of several inducible Hsp genes, Hsp23, Hsp26, and Hsp70, compared to males. In contrast, Hsp27 expression was uniquely elevated in females relative to the control males (Figure A). The constitutively expressed Hsps (Hsc70 and Hsp60) showed no significant sex-dependent differences (Figure A).

1.

Basal male and female Hsp expression levels in control and tau transgenic flies at day 10. (A,B) Basal mRNA expression levels of six inducible (Hsp22, Hsp23, Hsp26, Hsp27, Hsp70, and Hsp83) and two constitutive (Hsp60 and Hsc70) heat shock proteins in male and female control and tau transgenic flies. (A) Day 10 control flies display differential expression between male and female flies for specific Hsps. (B) Day 10 tau transgenic flies display differential expression between male and female flies for specific Hsps. Female data for both control and tau flies are normalized to day 10 male control flies for each Hsp. Data are presented as mean + SEM (n = 6) and analyzed using two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons, *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001. In each bar graph, heat shock protein comparisons are made between male and female flies, male data are shown first followed by female data.

We next examined basal Hsp expression levels in glial tau transgenic flies on day 10 (Figure B). We focused our analysis on day 10 flies to capture early effects of glial tau expression, prior to the onset of significant tau pathology and neurodegeneration that occurs in this model as previously described. Similar to control flies, we found that day 10 male tau transgenic flies showed significantly higher expression of Hsp23 relative to female day 10 tau transgenic flies (Figure B). However, in contrast to the control condition, Hsp27 was elevated in male tau transgenic flies compared to females, reversing the sex-specific pattern observed in controls (Figure A,B). The ATP-dependent chaperone, Hsp70, also exhibited sexual dimorphic expression in control flies, with levels in male flies higher than those in females (Figure A). This elevated level of Hsp70 expression was not seen in tau transgenic flies, suggesting that glial tau expression disrupts normal regulation of Hsp70 expression (Figure A, B). Expression of the two constitutively expressed chaperones, Hsp60 and Hsc70, remained stable across sexes and showed no significant changes in response to glial tau expression (Figure A, B). In summary, basal heat shock protein expression reveals a trend of reduced expression in females relative to males with Hsp27 as a notable exception in control flies (Figure A). This trend for reduced expression of select Hsps in females is less pronounced but still present in glial tau transgenic flies (Figure B).

2.2. Glial Tau Expression and Heat Stress Differentially Influence Small Heat Shock Protein Expression in Male and Female Flies

To determine the effect of heat stress and glial tau expression on sHsp expression, we examined expression levels for four small heat shock proteins (Hsp22, Hsp23, Hsp26, and Hsp27) in male and female control and glial tau transgenic flies (Figure ). Expression levels were analyzed in the presence and absence of heat stress and are presented as fold changes relative to basal male control flies. As expected, all four sHsps were significantly up-regulated in response to heat stress across genotypes and sexes. Hsp22, a mitochondrial sHsp, exhibited robust heat-induced expression in both male (∼150-fold increase) and female flies (∼600-fold increase) (Figure A, B), and glial tau expression did not significantly alter Hsp22 induction in either sex. Hsp23 also showed strong induction following heat stress in both sexes (∼500-fold) (Figure C,D). However, glial tau expression significantly reduced Hsp23 induction (reduced to a ∼250-fold induction) in males, while females were unaffected by glial tau expression (Figure C,D). A similar pattern was observed for Hsp26. Both male and female flies exhibited robust heat-induced expression (∼600-fold for males and ∼1500-fold for females), while glial tau expression significantly decreased Hsp26 induction in males (reduced to an ∼400-fold increase) and not females (Figure E,F). Hsp27 expression increased in response to heat stress in both males (∼400-fold) and females (500-fold), and was the only sHsp where the presence of glial tau expression augmented the heat stress-induced increase in Hsp27 in females only (increased ∼1500-fold), which is an approximate 3x increase over the induction by heat alone (Figure G,H).

2.

Small Hsp (sHsps) expression varies in male and female flies in response to glial tau expression and heat stress. (A–H) Relative mRNA expression levels of sHsps (Hsp22, Hsp23, Hsp26, Hsp27) for male (A,C,E,G) and female (B,D,F,H) flies under basal and heat stress conditions, comparing control and glial tau transgenic flies. Expression values are normalized to day 10 basal male control flies for each Hsp. Data are presented as mean + SEM (n = 6) and analyzed using two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001. Within each bar graph, the data are presented in the following order: control basal, control heat shock, tau basal, and tau heat shock. Each graph contains these four data sets.

In summary, while heat stress reliably induces the upregulation of all tested sHsps, glial tau expression modulates this response in a gene- and sex-specific manner. Notably, tau suppresses Hsp23 and Hsp26 induction in male flies, and enhances Hsp27 induction in female flies.

2.3. Heat Stress and Glial Tau Expression Differentially Affect Hsp70 and Hsp83 Expression in Male and Female Flies

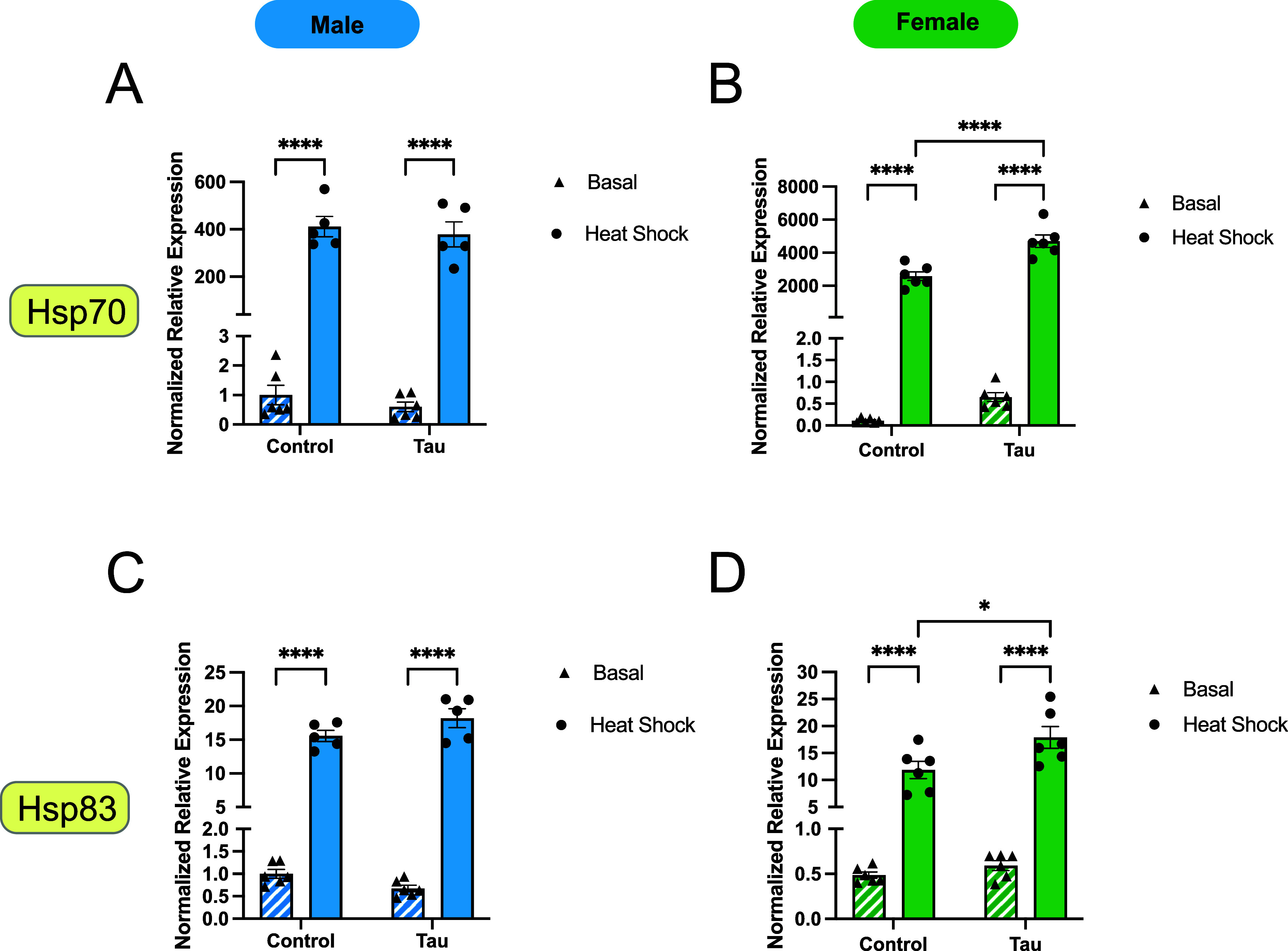

To assess the combined effects of heat stress and glial tau expression on the expression of large Hsps, we analyzed Hsp70 and Hsp83 transcript levels in male and female flies under all experimental conditions. Again, expression levels are presented as fold changes relative to those of male basal control flies (Figure ). As expected, Hsp70 was strongly induced by heat stress in both sexes (Figure A, part B). However, the magnitude of induction was markedly higher in females (>2000-fold) than in males (300-fold). Notably, in females, glial tau expression further enhanced heat-induced Hsp70 expression, while this effect was not observed in males. Hsp83 expression exhibited a similar pattern, though the fold change in response to heat stress for both sexes (<20-fold) was smaller (Figure C,D). In males, glial tau expression did not significantly alter Hsp83 induction in response to heat stress (Figure C). In contrast, females exhibited a significant increase in Hsp83 expression in response to heat stress when glial tau was present (Figure D).

3.

Large Hsp expression varies in day 10 male and female flies in response to glial tau expression and heat stress. (A–D) Relative mRNA expression levels of two large inducible heat shock proteins, Hsp70 (A,B) and Hsp83 (C,D), for male and female flies under basal and heat stress conditions, comparing control and glial tau transgenic flies. Expression values are normalized to day 10 basal male control flies for each Hsp. Data are presented as mean + SEM (n = 6) and analyzed using two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons, *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001. Within each bar graph, the data are presented in the following order: control basal, control heat shock, tau basal, tau heat shock. Each graph contains these four data sets.

Together, these results show that Hsp70 and Hsp83 are differentially regulated by glial tau expression and heat stress in a sex-dependent fashion with females showing greater responsiveness to combined heat stress and glial tau expression.

2.4. Constitutive Hsps Exhibit Sexually Dimorphic Responses to Heat Stress and Glial Tau Expression

To assess how constitutively expressed Hsps respond to heat stress and glial tau expression, we examined expression levels of Hsp60 and Hsc70, reporting changes normalized to male basal control flies. Hsp60 expression remained unchanged in response to heat stress and glial tau expression in male flies (Figure A). In contrast, female flies exhibited a significant induction of Hsp60 only when both heat stress and glial tau expression were present (Figure B). Neither heat stress nor the presence of glial tau expression alone was sufficient to alter Hsp60 expression in females (Figure B), suggesting a combinatorial effect specific to females.

4.

Constitutive Hsp expression changes in male and female flies in response to glial tau expression and heat stress. (A–D) Relative mRNA expression levels of two constitutive heat shock proteins, Hsp60 (A,B) and Hsc70 (C,D) for male and female flies under basal and heat stress conditions, comparing control and glial tau transgenic flies. Expression values are normalized to day 10 basal male control flies for each Hsp. Data are presented as mean + SEM (n = 6) and analyzed using two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons, *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001. Within each bar graph, the data are presented in the following order: control basal, control heat shock, tau basal, tau heat shock. Each graph contains these four data sets.

Hsc70 expression increased significantly in response to heat stress in control male flies but not in females. Heat stress induced Hsc70 expression in both sexes of tau transgenic flies (Figure C,D) resulting in significant increases in mRNA expression (∼6-fold in males and ∼2.5-fold in females). The combined presence of heat stress and glial tau expression further enhanced Hsc70 expression in both males and females, suggesting an additive effect of these stressors on Hsc70 regulation (Figure C,D), with more substantial increases observed in males than females.

2.5. Differential Hsp Protein Expression is Observed in Response to Heat Stress and Glial Tau Expression

To determine whether the observed changes in RNA expression corresponded with changes in protein expression, we examined Hsp27 and Hsp70 protein levels by Western blot analysis. Protein expression was compared across sex, heat stress, and glial tau expression conditions. Quantified protein levels were normalized to those under male basal conditions. Under basal conditions, Hsp27 protein levels remained unchanged in both males or females (Figure A,B). Heat stress induced a ∼3-fold increase in Hsp27 expression in both sexes, regardless of glial tau expression (Figure A,B). However, a sex-specific difference emerged under heat stress in the presence of glial tau, where females expressing glial tau exhibited significantly higher Hsp27 levels than males under the same conditions (Figure A,B).

5.

Hsp27, but not Hsp70, protein levels are increased in response to heat stress in a sex-dependent fashion. (A) Representative Western blot images of Hsp27 levels and actin levels from brain lysates of male and female control and tau transgenic flies in response to heat stress. (B) Quantification of Hsp27 levels by densitometric analysis, expressed as a ratio of Hsp27 to actin. (C) Representative Western blot images of Hsp70 levels and actin levels from brain lysates of male and female control and tau transgenic flies in response to heat stress. (D) Quantification of Hsp70 levels by densitometric analysis, expressed as a ratio of Hsp70 to actin. Protein levels are normalized to day 10 basal control male flies for each Hsp. Data are presented as mean + SEM (n = 5–6) and analyzed using two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons, *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001. Data in bar graphs (B,D) are presented in the following order: Basal male, heat stress male, tau basal male, tau heat stress male, basal female, heat stress female, tau basal female, and tau heat stress female.

In contrast, Hsp70 protein expression was more variable than that of Hsp27 and did not show a consistent or significant response to heat stress or glial tau expression across sexes (Figure C,D). While Western blot analysis of individual flies suggested a possible increase in Hsp70 levels with glial tau expression in males (Figure C), this trend was not statistically significant when averaged across all biological samples (Figure D). Together, these results indicate that Hsp27 protein expression reflects both heat stress and glial tau-related regulation in a sex-dependent manner, while Hsp70 protein expression appears more variable and less responsive to these conditions.

3. Discussion

The Hsp chaperone network promotes proteostasis by fostering protein–protein interactions among member and client proteins. ,, Dysregulation of this network contributes to the development of tauopathies and other protein-misfolding diseases, although the mechanisms underlying this process remain unclear. , Furthermore, many neurodegenerative diseases exhibit distinct sexual dimorphisms in incidence and progression. ,, In this work, we examined how sex, heat stress, and early glial tau expression affect inducible (Hsp22, Hsp23, Hsp26, Hsp27, Hsp70, and Hsp83) and constitutive (Hsp60 and Hsc70) Hsp expression in the Drosophila brain. We observed noticeable differences in Hsp expression patterns across conditions and we found that, generally, females exhibit a more robust chaperone response in response to stress, particularly at the level of transcription. These results provide the first systematic determination of Hsp expression patterns in response to heat stress and glial tau expression, and provide insight into how stress-responsive pathways may contribute to sex differences in tauopathy progression. ,−

3.1. Basal Hsp Expression is Influenced by Sex and Glial Tau Expression

Under basal conditions in the absence of heat stress, sex differences in Hsp expression were evident (Figure ). In control flies, males exhibited significantly higher expression of a subset of Hsps (Hsp23, Hsp26, and Hsp70), while females expressed higher levels of Hsp27. In glial tau transgenic flies, males displayed an enhanced expression of Hsp23 and Hsp27, in contrast to the elevated levels of Hsp27 in female control flies (Figure ). This relative discrepancy in Hsp27 expression in female tau transgenic flies is notable as Hsp27 is a small heat shock protein that functions as a holdase for misfolded or aggregated proteins and serves as the first line of defense in proteostasis. − The blunted transcript expression of Hsp27 in female glial tau transgenic flies (Figure B) may reflect a sex-specific vulnerability to tau-induced proteostatic stress. Hsp27 is capable of forming a stable complex with tau, and then recruiting the Hsp70/Hsp40/Hsp90 refolding complex to prevent aggregation. ,, Analogous sex-specific patterns in Hsp27 expression have been reported in other cell types, including mammalian cardiac muscle and blood cells. − Constitutive Hsps (Hsp60 and Hsc70) did not display sex-specific basal expression patterns in control and glial tau transgenic flies (Figure ).

3.2. Inducible Hsps are Differentially Regulated by Heat Stress and Tau

As expected, heat stress robustly induced all small and large inducible heat shock protein transcripts in both sexes in control and glial tau transgenic flies (Figures and ). This upregulation was not surprising; however, females displayed greater induction, with ∼2–4-fold higher expression of Hsp22, Hsp26, Hsp27, and Hsp70 relative to males. Specific instances of sex differences in Hsp expression have been reported, with males displaying elevated Hsp72 expression after exercise and differences due to oxidative stress and aging have been monitored. Further studies have noted a female advantage in stress response , characterized by faster adaptation and greater sensitivity to some stress conditions. This has previously been linked directly and indirectly to hormone regulation, including estrogen. , Whether similar hormone-related effects underlie how sex determines Hsp expression in our studies remains to be determined.

Heat shock proteins are induced in response to a variety of stress conditions including: heat stress, hypoxia, oxidative stress, and exposure to toxins. We suggest that the presence of misfolded proteins in excess, such as expression of glial tau, is another form of stress on the proteostasis system. Since heat shock proteins serve a protective role during heat stress , in addition to a regulatory role during normal cell growth, we further examined the global induction of Hsps during heat stress by sex and ± glial tau expression. While heat shocked male and female flies exhibited some similarities in regard to induction of mRNA, striking differences emerged for both small (Hsp22, Hsp23, Hsp26, and Hsp27) and large Hsps (Hsp70 and Hsp83).

Our data indicate that the expression of glial tau impacts both Hsp mRNA and protein expression for a subset of the chaperone network. Male flies exhibit a decrease in Hsp23 and Hsp26 mRNA in response to both heat and glial tau expression (Figure C,E), while female flies exhibit an increase in mRNA levels of Hsp27 (Figure F), Hsp70 (Figure B), Hsp83 (Figure D), and Hsp60 (Figure A) as a result of glial tau expression in the presence of heat stress. Both males and females exhibit a significant increase in mRNA levels of Hsc70 (Figure C, D) in response to heat stress in the presence of tau expression, which suggests a potential role for the constitutive heat shock protein response to multiple stress conditions. Interestingly, there are discrepancies between the observed changes in mRNA and protein expression. For example, there is a significant elevation in transcript levels of Hsp27 (Figure H) and Hsp70 (Figure A) in tau-expressing females, however, this is not observed at the protein level (Figure ). At the protein level, Hsp27 is significantly increased due to heat shock in both males and females, but the combined expression of tau and heat shock does not result in an additive effect at the protein level similar to that observed at the mRNA level. However, females exhibit a significant and small relative increase in expression of Hsp27 at the protein level compared to males with combined tau expression and heat shock (Figure ). Surprisingly, there is no observed effect on Hsp70 protein expression (Figure C, D) in response to heat shock or tau expression. Several factors may contribute to these observed results. We hypothesize that the changes observed at the mRNA level for Hsp70 would eventually be observed at the protein level as well, but our experimental time course was not long enough to capture this delayed effect. Since sHsps are known to be initial responders in the proteostasis network and Hsp70 plays a larger role in protein folding and turnover, our results are consistent with the respective roles of Hsp27 and Hsp70 in responding to the heat shock response- with Hsp27 elevation occurring first. Additionally, there is evidence that tau expression contributes to post-transcriptional changes in chromatin and RNA-binding proteins which may impact mRNA and protein processing. Future studies investigating additional time points post heat shock will better characterize the relationship between chaperone mRNA and protein expression in response to these stressors.

Tau is a known client protein for several Hsps. ,,,,− For example, Hsp70 binds to tau at a location that overlaps with a portion of the microtubule-binding site on tau, suggesting that Hsp70 binding may regulate physiological tau function and prevent aggregation. Our results show that the presence of tau in day 10 flies augments Hsp70 expression in females. The elevated levels of Hsp70 may have implications in the Hsp70-mediated control of tau aggregation. Moreover, Hsp70 levels play a critical role in general protein folding, and the higher Hsp70 levels observed in females may impair general hydrophobic collapse. , Therapeutic strategies involving inhibition of Hsp70 have been evaluated to facilitate tau clearance, , and our results will enable more refined strategies based on sexually dimorphic expression patterns.

Sex-dependent stress responses were observed for some chaperones, including Hsp27. Females generally expressed Hsp27 more robustly. Hsp27 contributes to the initial response to tau in females, as it has been previously indicated to bind to tau and prevent aggregation. ,,, The lack of an increase in male flies in response to tau expression is unexpected, although this may partially explain the previously reported differences in tau load and disease progression which are observed, and distinguish pathology between sexes. Hsp27 is secreted from astrocytes to promote neuroprotection. As noted only in female flies, our finding that glial tau expression decreases basal Hsp27 levels provides a potential mechanism by which glial tau pathology could contribute to tauopathy pathogenesis and progression. However, we see this only in females, suggesting that the sex-specific decrease in Hsp27 may be pathologically relevant.

Hsp83 is interesting in another regard as it is the Drosophila homologue to Hsp90, which is involved in hormone receptor activation, and our results indicate that Hsp83 is significantly upregulated during heat stress and glial tau expression, only in females. This suggests that the impacts of tau expression, stress, and/or sex on Hsp83 regulation may occur upstream of transcription and may be susceptible to a feedback process. We hypothesize that Hsp23 and Hsp26 may be involved in a similar feedback process but one that only occurs in male flies, further suggesting that early (day 10) tau–chaperone interactions vary across sex. For example, Hsp22 is shown to improve cognition by clearing accumulated tau, suggesting a role for sHsps during early tau expression. Our data indicate that tau–chaperone interactions are more nuanced than previously determined at a sex-specific level.

Overall, what is most striking is the lack of concerted Hsp expression in either males or females, which indicates that individual Hsps are precisely regulated in response to stress variables, consistent with reports of dysregulation of Hsps in disease models. These results demonstrate the advantage of comparing multiple Hsps under different conditions, illustrating the lack of redundancy in the chaperone network and suggesting that each Hsp is individually transcriptionally regulated. Our results distinguish key sexual dimorphisms in Hsp transcript expression, suggesting that males exhibit a more modest heat shock protein response to heat stress and tau expression compared to females. This may be due to a higher stress threshold required for Hsp activation in males compared to females. Generally, female flies present a more robust heat shock protein response to heat stress and tau expression, indicating that the threshold required for activation of the heat shock protein response in females is differentially regulated compared to males. Overall, these results contribute to our understanding of the molecular mechanisms that mediate sex differences in the neurological stress response, tauopathies, and aging-related disease.

Hsp27 and Hsp70 preferentially associate with phosphorylated tau under stress conditions and are co-immunoprecipitated with tau from AD brain homogenates. Although low-levels of Hsp27 and Hsp70 are present in neurons and glia, glia exhibit higher levels of Hsp27 and Hsp70 in astrocytes and microglia, respectively, relative to neurons. Although there is robust induction and recruitment of the Hsp27/Hsp70 pathway in glia, this machinery is ultimately insufficient to prevent tau pathogenesis. Some reports suggest that prolonged activation of the Hsp27/Hsp70 chaperone pathway may induce proteotoxicity, while other reports indicate a protective effect provided through expression/induction of Hsp27. ,,, Further evidence for Hsp27 neuroprotection suggests the mechanism may be tied to the interactions between Hsp27, tau, and microtubules. ,, In male flies, we observed no change in Hsp27/Hsp70 expression under basal conditions, whereas females exhibited a decline in Hsp27 expression as a result of tau expression.

Glial cells appear to participate in the propagation and spread of tau pathology from cell to cell and across brain regions, which may accelerate neurodegeneration. − Basal expression of Hsp23 and Hsp27 in only females is reduced due to tau expression (Figure ). The relative decrease in female flies may suggest a mechanism by which tau expression decreases the Hsp response through a sexually dimorphic mechanism. Hsp27 is further known to interact with tau and has previously been shown to rescue neural deficits due to tau expression, but it is not the only chaperone known to interact with tau. , This response at day 10 in females, but not males, may indicate that different thresholds of a particular “stress” or client protein may be required to initiate a chaperone response. In a different model of stress pathology in mice, alcoholic liver injury induced sexually dimorphic changes in Hsp27 expression, suggesting that sex-related variables or hormones can trigger sexually dimorphic stress-induced expression patterns. The presence of tau during early aging differentially impacts the male and female basal heat shock protein expression. Whether this phenomenon directly contributes to variations in disease pathologies remain unknown.

4. Conclusions

Our findings reveal an intricate and sexually dimorphic regulation of the heat shock protein response in the aging Drosophila brain, with profound implications for neurodegenerative disease. While female flies exhibit a more robust chaperone response, particularly through Hsp27 and Hsp70 compared to males, this protection is further elevated under the combined burden of stress and tau expression and observed in constitutive Hsp60 and Hsc70. The elevation of Hsp27 and Hsp70 in females expressing tau is particularly notable, as these chaperones are crucial for preventing tau aggregation. The dampened and attenuated response of Hsp23 and Hsp26 expression in males suggests a heightened vulnerability to proteotoxic stress. These sexually dimorphic responses could underlie well-documented differences in neurodegenerative disease susceptibility, emphasizing the need for sex-specific therapeutic strategies that account for the complex interplay between stress and tau pathology.

A breakdown of proteostasis is seen in human tauopathies, − indicating the early response observed in females may contribute to an overburdened proteostasis network that is impacted during aging. Future studies will evaluate the impacts of aging on this system and alterations in mRNA and protein expression due to aging, stress, and sex. Further downstream processes, specifically the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway, which demonstrates a decline in function with age, may also be evaluated. Moreover, proteins are prone to age-related damage including: cleavage, covalent modifications, oxidative lesions, glycation, cross-linking, and denaturation. As the cell ages, mitochondrial malfunction and the resulting decrease in ATP production and increase in reactive oxygen species (ROS) can lead to a greater output of misfolded proteins and more aggregation, which impacts the broader proteostasis network. Therefore, studies that characterize the impacts of aging, stress, and tau on heat shock proteins will enable a more detailed understanding of disease-related pathologies.

5. Materials and Methods

5.1. Drosophila melanogaster Stocks and Genetics

w 1118 was obtained from the Bloomington Stock Center (BL#3605), and double recombinant control flies (repo-GAL4, tubulin-GAL80 TS /TM3,Sb) and triple recombinant tau flies (repo-GAL4, tubulin-GAL80 TS , UAS-Tau WT / TM6B,Tb) were used (Scarpelli et al., 2019). Flies were maintained at 25 °C in plastic vials with standard cornmeal-based food (NutriFly) supplemented with propionic acid and tegosept. Crosses (repo-GAL4, tubulin-GAL80 TS /TM3, Sb X w 1118 and repo-GAL4, tubulin-GAL80 TS , UAS-Tau WT / TM6B, Tb X w 1118) were performed at 25 °C in incubators with humidity control and 12 h light/dark cycles. Progeny were selected against balancers and separated by sex, and aged to 10 days at 25 °C. Flies were flipped to new food every 2–3 days while aging.

5.2. Drosophila Heat Stress Conditions

Once flies were aged to 10 days, half of the vials were kept at 25 °C (no heat (NH), basal conditions), while the other half were placed at 37 °C for 1 h to induce heat stress (HS). Following the heat stress period, flies were placed back at 25 °C for a 30 min recovery period and processed for RNA extraction.

5.3. RNA Extraction and cDNA Synthesis

Ten-day old basal and heat stress control and tau transgenic flies were anesthetized with CO2 and flash-frozen in a dry ice/ethanol bath. Heads were dissected and homogenized in TRIzol. Each biological replicate contained 5–10 fly heads. RNA was extracted from these samples via chloroform/isopropanol (Life Technologies) RNA precipitation, according to standard protocols. Briefly, 0.2 volumes of chloroform were added to each TRIzol homogenate, followed by phase separation in Phase Lock Gel-Heavy 2 mL tubes after spinning at 4 °C, 12k rpm for 1 min. Isopropanol was added, and the solution was precipitated overnight at −20 °C and subsequently spun at 4 °C, 13.6k rpm for 30 min. The pellet was washed with 800 μL of 75% ethanol and spun for 10 min at 13.6k rpm. The pellet was redissolved in nuclease-free H2O and placed in a 60 °C heat block for 10 min to facilitate dissolution. RNA concentration and purity were analyzed using a NanoDrop 1000 spectrophotometer, and RNA was ≥40 ng/μL. Samples were treated with DNase (DNA-free kit; Ambion) and 250 ng of RNA was used to generate cDNA using the SuperScript First-Strand Synthesis System kit (Invitrogen).

5.4. Quantification of Hsp Expression by qPCR

qPCR was performed using SYBR Green (Applied Biosystems). Each condition represents the data from 5 to 6 biological replicates, and each composed of three technical replicates. RpL32 was used as the internal control gene, and primer efficiency for all primer pairs was determined to be between 87 and 108%. Primers used were: Hsp22: (Forward) GAT GAA CTG GAC AAG GCT CTA A, (Reverse) TAT GAT TGG CGA CTG CTT CTC; Hsp23: (Forward) GCG ATA ACA GCT AAA GCG AAA G, (Reverse) CAA GGC TCA ACA ATG GAA TA; Hsp26: (Forward) TGG ACG ACT CCA TCT T, (Reverse) TAG CCA TCG GGA ACC TTG TA; Hsp27: (Forward) GAA GTC GTG AAG GAG GAA G, (Reverse) GGC AAC ACT CCC GTT TCT; Hsp60: (Forward) AGA TGT GAT GAG AAC CGA AAC C, (Reverse) CCG ACT GCT GAT GAC TGA TAA C; Hsp70A: (Forward) GTC GTT ACC GAG GAA C, (Reverse) CAC CTT GCC ATG TTG GTA GA; Hsc70: (Forward) CCT ATG TTG CCT TCA CCG ATA C, (Reverse) TCG AAC TTG CGA CCA ATC AA; Hsp83: (Forward) CAC ATG GAG GTC GAT TAA G, (Reverse) CGG CCG TAG TAA ACT CAG TAT AAA; RpL32: (Forward) CCA GTC GGA TCG ATA TGC TAA G, (Reverse) CCG ATG TTG GGC ATC AGA TA.

5.5. Western Blotting and Protein Quantification

Western blot analysis was performed to quantify Hsp27 and Hsp70 protein expression across all conditions, including sex, genotype, and heat stress. Single heads isolated from flash frozen day 10 flies were homogenized in 2× Laemmli sample buffer (65.8 mM Tris–HCl, pH 6.8, 2.1% SDS, 26.3% (w/v) glycerol, and 1% bromophenol blue) and heat denatured for 10 min. Samples were subjected to SDS-PAGE in a 26-well polyacrylamide gel (BioRad), with one head per lane. Protein was transferred to a poly(vinylidene fluoride) (PVDF) membrane using the Trans-Blot Turbo Transfer System (Bio-Rad) and blocked in 2% milk with 0.1% Tween in TBS. Membranes were incubated overnight in primary antibodies, washed in 2% milk with 0.1% Tween in TBS (wash buffer), followed by incubation in a complementary secondary antibody. Secondary antibodies were rinsed, and ECL substrate (Bio-Rad) was utilized for imaging. The signal was detected by chemiluminescence imaging on an Azure Biosystems c600.

The following primary and secondary antibodies were used: ms α Actin (1:1000) DSHB, ms α Hsp27 (1:1000) Abcam, ms α Hsp70 (1:1000) (gifted by R.Tanguay), gt α rb IgG(HRP) (1:20,000) ThermoFisher, gt α ms IgG (HRP) (1:20,000) ThermoFisher. Protein bands in Western blot images were quantified with a densitometric analysis in ImageJ. Protein band densities were quantified relative to a corresponding actin loading control to account for loading variability. Normalized density was achieved by comparing the relative band density to the average band density of all of the basal control male samples.

5.6. Statistical Analyses

All statistical analyses were performed with GraphPad Prism 10 software. Relative expression of mRNA is determined by normalizing male or female flies to basal conditions unless otherwise indicated. All data presented are expressed as mean ± SEM. Multiple group comparisons analyzing sex, heat stress, tau expression, and aging variables were evaluated with a Two-Way ANOVA, followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons tests.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank members of the Colodner and McMenimen laboratories for feedback and constructive discussions.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- AD

Alzheimer’s disease

- Hsc

heat shock cognate

- Hsp

heat shock proteins

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.5c06686.

Western blots used to quantify protein expression of Hsp27, Hsp70, and actin are included (PDF)

Margot Whitmore: data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, and writing-review and editing. Maeve Coughlan: data curation, formal analysis, investigation, and methodology. Martha A. Kahlson: data curation, investigation, methodology, writing-review and editing, and validation. Jaasiel Alvarez: data curation, formal analysis, investigation, and methodology. Louisa Zebrowski: data curation and investigation. Kathryn A. McMenimen: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, funding acquisition, investigation, methodology, project administration, resources, supervision, validation, visualization, roles/writingoriginal draft, and writingreview and editing. Kenneth J. Colodner: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, funding acquisition, investigation, methodology, project administration, resources, supervision, validation, visualization, roles/writingoriginal draft, and writingreview and editing.

This research was funded by the National Institutes of Health (R15GM120654-01 (KAM)), Mount Holyoke College Lynk Program, the Harap Family Fund, and the Mount Holyoke College Chemistry Department, Biochemistry Program, and Neuroscience & Behavior Program.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Published as part of ACS Omega special issue “Undergraduate Research as the Stimulus for Scientific Progress in the USA”.

References

- Finka A., Sood V., Quadroni M., Rios P. D. L., Goloubinoff P.. Quantitative proteomics of heat-treated human cells show an across-the-board mild depletion of housekeeping proteins to massively accumulate few HSPs. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2015;20:605–620. doi: 10.1007/s12192-015-0583-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finka A., Goloubinoff P.. Proteomic data from human cell cultures refine mechanisms of chaperone-mediated protein homeostasis. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2013;18:591–605. doi: 10.1007/s12192-013-0413-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter K., Haslbeck M., Buchner J.. The Heat Shock Response: Life on the Verge of Death. Mol. Cell. 2010;40:253–266. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritossa F. M.. Experimental activation of specific loci in polytene chromosomes of Drosophila. Exp. Cell Res. 1964;35:601–607. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(64)90147-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park H. G., Han S. I., Oh S. Y., Kang H. S.. Cellular responses to mild heat stress. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. CMLS. 2005;62:10–23. doi: 10.1007/s00018-004-4208-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yombo D. J. K., Mentink-Kane M. M., Wilson M. S., Wynn T. A., Madala S. K.. Heat shock protein 70 is a positive regulator of airway inflammation and goblet cell hyperplasia in a mouse model of allergic airway inflammation. J. Biol. Chem. 2019;294:15082–15094. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA119.009145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slingsby C., Wistow G. J., Clark A. R.. Evolution of crystallins for a role in the vertebrate eye lens. Protein Sci. 2013;22:367–380. doi: 10.1002/pro.2229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finka A., Sharma S. K., Goloubinoff P.. Multi-layered molecular mechanisms of polypeptide holding, unfolding and disaggregation by HSP70/HSP110 chaperones. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2015;2:29. doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2015.00029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cashikar A. G., Duennwald M., Lindquist S. L.. A Chaperone Pathway in Protein Disaggregation. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:23869–23875. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M502854200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fauvet B., Finka A., Castanié-Cornet M.-P., Cirinesi A.-M., Genevaux P., Quadroni M., Goloubinoff P.. Bacterial Hsp90 Facilitates the Degradation of Aggregation-Prone Hsp70-Hsp40 Substrates. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2021;8:653073. doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2021.653073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mogk A., Bukau B., Kampinga H. H.. Cellular Handling of Protein Aggregates by Disaggregation Machines. Mol. Cell. 2018;69:214–226. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2018.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brehme M., Voisine C., Rolland T., Wachi S., Soper J. H., Zhu Y., Orton K., Villella A., Garza D., Vidal M., Ge H., Morimoto R. I.. A Chaperome Subnetwork Safeguards Proteostasis in Aging and Neurodegenerative Disease. Cell Reports. 2014;9:1135–1150. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.09.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dulle J. E., Fort P. E.. Crystallins and neuroinflammation: The glial side of the story. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2016;1860:278. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2015.05.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haslbeck M., Vierling E.. A first line of stress defense: small heat shock proteins and their function in protein homeostasis. J. Mol. Biol. 2015;427:1537–1548. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2015.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koopman M. B., Rüdiger S. G. D.. Alzheimer Cells on Their Way to Derailment Show Selective Changes in Protein Quality Control Network. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2020;7:214. doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2020.00214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arendt T., Stieler J. T., Holzer M.. Tau and tauopathies. Brain Res. Bull. 2016;126:238–292. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2016.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrer I., López-González I., Carmona M., Arregui L., Dalfó E., Torrejón-Escribano B., Diehl R., Kovacs G. G.. Glial and Neuronal Tau Pathology in Tauopathies:Characterization of Disease-Specific Phenotypes and Tau Pathology Progression. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2014;73:81–97. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0000000000000030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrer I.. Diversity of astroglial responses across human neurodegenerative disorders and brain aging. Brain Pathol. 2017;27:645–674. doi: 10.1111/bpa.12538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feany M. B., Dickson D. W.. Neurodegenerative disorders with extensive tau pathology: A comparative study and review. Ann. Neurol. 1996;40:139–148. doi: 10.1002/ana.410400204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahlson M. A., Colodner K. J.. Glial Tau Pathology in Tauopathies: Functional Consequences. J. Exp. Neurosci. 2016;9:43–50. doi: 10.4137/JEN.S25515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colodner K. J., Feany M. B.. Glial fibrillary tangles and JAK/STAT-mediated glial and neuronal cell death in a Drosophila model of glial tauopathy. J. Neurosci.: Off. J. Soc. Neurosci. 2010;30:16102–16113. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2491-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higuchi M., Ishihara T., Zhang B., Hong M., Andreadis A., Trojanowski J. Q., Lee V. M.-Y.. Transgenic Mouse Model of Tauopathies with Glial Pathology and Nervous System Degeneration. Neuron. 2002;35:433–446. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(02)00789-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forman M. S., Lal D., Zhang B., Dabir D. V., Swanson E., Lee V. M.-Y., Trojanowski J. Q.. Transgenic Mouse Model of Tau Pathology in Astrocytes Leading to Nervous System Degeneration. J. Neurosci. 2005;25:3539–3550. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0081-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moll A., Ramirez L. M., Ninov M., Schwarz J., Urlaub H., Zweckstetter M.. Hsp multichaperone complex buffers pathologically modified Tau. Nat. Commun. 2022;13:3668. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-31396-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimura H., Miura-Shimura Y., Kosik K. S.. Binding of tau to heat shock protein 27 leads to decreased concentration of hyperphosphorylated tau and enhanced cell survival. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:17957–17962. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400351200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldbaum O., Riedel M., Stahnke T., Richter-Landsberg C.. The small heat shock protein HSP25 protects astrocytes against stress induced by proteasomal inhibition. Glia. 2009;57:1566–1577. doi: 10.1002/glia.20870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu A., Fox S. G., Cavallini A., Kerridge C., O’Neill M. J., Wolak J., Bose S., Morimoto R. I.. Tau protein aggregates inhibit the protein-folding and vesicular trafficking arms of the cellular proteostasis network. J. Biol. Chem. 2019;294:7917–7930. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA119.007527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lackie R. E., Maciejewski A., Ostapchenko V. G., Marques-Lopes J., Choy W.-Y., Duennwald M. L., Prado V. F., Prado M. A. M.. The Hsp70/Hsp90 Chaperone Machinery in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Front. Neurosci. 2017;11:254. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2017.00254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter-Landberg C., Goldbaum O.. Stress proteins in neural cells: functional roles in health and disease. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. CMLS. 2003;60:337–349. doi: 10.1007/s000180300028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz L., Vollmer G., Richter-Landsberg C.. The Small Heat Shock Protein HSP25/27 (HspB1) Is Abundant in Cultured Astrocytes and Associated with Astrocytic Pathology in Progressive Supranuclear Palsy and Corticobasal Degeneration. Int. J. Cell Biol. 2010;2010:1–10. doi: 10.1155/2010/717520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yata K., Oikawa S., Sasaki R., Shindo A., Yang R., Murata M., Kanamaru K., Tomimoto H.. Astrocytic neuroprotection through induction of cytoprotective molecules; a proteomic analysis of mutant P301S tau-transgenic mouse. Brain Res. 2011;1410:12–23. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2011.06.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dabir D. V., Trojanowski J. Q., Richter-Landsberg C., Lee V. M.-Y., Forman M. S.. Expression of the Small Heat-Shock Protein αB-Crystallin in Tauopathies with Glial Pathology. Am. J. Pathol. 2004;164:155–166. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63106-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang F., Beltran-Lobo P., Sung K., Goldrick C., Croft C. L., Nishimura A., Hedges E., Mahiddine F., Troakes C., Golde T. E., Perez-Nievas B. G., Hanger D. P., Noble W., Jimenez-Sanchez M.. Reactive astrocytes secrete the chaperone HSPB1 to mediate neuroprotection. Sci. Adv. 2024;10:eadk9884. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.adk9884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voss M. R., Stallone J. N., Li M., Cornelussen R. N. M., Knuefermann P., Knowlton A. A.. Gender differences in the expression of heat shock proteins: the effect of estrogen. Am. J. Physiol.-Hear. Circ. Physiol. 2003;285:H687–H692. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01000.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapila R., Kashyap M., Gulati A., Narasimhan A., Poddar S., Mukhopadhaya A., Prasad N. G.. Evolution of sex-specific heat stress tolerance and larval Hsp70 expression in populations of Drosophila melanogaster adapted to larval crowding. J. Evol. Biol. 2021;34:1376–1385. doi: 10.1111/jeb.13897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jagla T., Dubińska-Magiera M., Poovathumkadavil P., Daczewska M., Jagla K.. Developmental Expression and Functions of the Small Heat Shock Proteins in Drosophila. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018;19:3441. doi: 10.3390/ijms19113441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao S., Hendrie H. C., Hall K. S., Hui S.. The Relationships Between Age, Sex, and the Incidence of Dementia and Alzheimer Disease: A Meta-analysis. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 1998;55:809–815. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.9.809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder H. M., Asthana S., Bain L., Brinton R., Craft S., Dubal D. B., Espeland M. A., Gatz M., Mielke M. M., Raber J., Rapp P. R., Yaffe K., Carrillo M. C.. Sex biology contributions to vulnerability to Alzheimer’s disease: A think tank convened by the Women’s Alzheimer’s Research Initiative. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2016;12:1186–1196. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2016.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarmoun K., Lachance V., Corvec V. L., Bélanger S.-M., Beaucaire G., Kourrich S.. Comprehensive Analysis of Age- and Sex-Related Expression of the Chaperone Protein Sigma-1R in the Mouse Brain. Brain Sci. 2024;14:881. doi: 10.3390/brainsci14090881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahale R. R., Krishnan S., Divya K. P., Jisha V. T., Kishore A.. Gender differences in progressive supranuclear palsy. Acta Neurol. Belg. 2022;122:357–362. doi: 10.1007/s13760-021-01599-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gleixner A. M., Pulugulla S. H., Pant D. B., Posimo J. M., Crum T. S., Leak R. K.. Impact of aging on heat shock protein expression in the substantia nigra and striatum of the female rat. Cell Tissue Res. 2014;357:43–54. doi: 10.1007/s00441-014-1852-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balch W. E., Morimoto R. I., Dillin A., Kelly J. W.. Adapting Proteostasis for Disease Intervention. Science. 2008;319:916–919. doi: 10.1126/science.1141448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sørensen J. G., Sarup P., Kristensen T. N., Loeschcke V.. Mild Stress and Healthy Aging. Applying Hormesis in Aging Research and Interventions. 2008:65. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4020-6869-0_5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Scarpelli E. M., Trinh V. Y., Tashnim Z., Krans J. L., Keller L. C., Colodner K. J.. Developmental expression of human tau in Drosophila melanogaster glial cells induces motor deficits and disrupts maintenance of PNS axonal integrity, without affecting synapse formation. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0226380. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0226380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadizadeh Esfahani A., Sverchkova A., Saez-Rodriguez J., Schuppert A. A., Brehme M.. A systematic atlas of chaperome deregulation topologies across the human cancer landscape. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2018;14:e1005890. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodina A., Wang T., Yan P., Gomes E. D., Dunphy M. P. S., Pillarsetty N., Koren J., Gerecitano J. F., Taldone T., Zong H., Caldas-Lopes E., Alpaugh M., Corben A., Riolo M., Beattie B., Pressl C., Peter R. I., Xu C., Trondl R., Patel H. J., Shimizu F., Bolaender A., Yang C., Panchal P., Farooq M. F., Kishinevsky S., Modi S., Lin O., Chu F., Patil S., Erdjument-Bromage H., Zanzonico P., Hudis C., Studer L., Roboz G. J., Cesarman E., Cerchietti L., Levine R., Melnick A., Larson S. M., Lewis J. S., Guzman M. L., Chiosis G.. The epichaperome is an integrated chaperome network that facilitates tumour survival. Nature. 2016;538:397–401. doi: 10.1038/nature19807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryder B. D., Wydorski P. M., Hou Z., Joachimiak L. A.. Chaperoning shape-shifting tau in disease. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2022;47:301–313. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2021.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koopman M. B., Ferrari L., Rüdiger S. G. D.. How do protein aggregates escape quality control in neurodegeneration? Trends Neurosci. 2022;45:257–271. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2022.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins E. C., Shah N., Gomez M., Casalena G., Zhao D., Kenny T. C., Guariglia S. R., Manfredi G., Germain D.. Proteasome mapping reveals sexual dimorphism in tissue-specific sensitivity to protein aggregations. EMBO Rep. 2020;21:EMBR201948978. doi: 10.15252/embr.201948978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi J., Zhang M., Hu Y., Liu J., Li K., Sun X., Chen S., Liu J., Ye L., Fan J., Jia J.. Differences in transcriptome characteristics and drug repositioning of Alzheimer’s disease according to sex. Neurobiol. Dis. 2025;210:106909. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2025.106909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hipp M. S., Kasturi P., Hartl F. U.. The proteostasis network and its decline in ageing. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2019;29:421. doi: 10.1038/s41580-019-0101-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampathkumar N. K., Bravo J. I., Chen Y., Danthi P. S., Donahue E. K., Lai R. W., Lu R., Randall L. T., Vinson N., Benayoun B. A.. Widespread sex dimorphism in aging and age-related diseases. Hum. Genet. 2020;139:333–356. doi: 10.1007/s00439-019-02082-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doust Y. V., King A. E., Ziebell J. M.. Implications for microglial sex differences in tau-related neurodegenerative diseases. Neurobiol. Aging. 2021;105:340–348. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2021.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arrigo A.-P., Simon S., Gibert B., Kretz-Remy C., Nivon M., Czekalla A., Guillet D., Moulin M., Diaz-Latoud C., Vicart P.. Hsp27 (HspB1) and αB-Crystallin (HspB5) as therapeutic targets. FEBS Lett. 2007;581:3665–3674. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.04.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stetler R. A., Gao Y., Signore A. P., Cao G., Chen J.. HSP27: mechanisms of cellular protection against neuronal injury. Curr. Mol. Med. 2009;9:863–872. doi: 10.2174/156652409789105561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baughman H. E. R., Clouser A. F., Klevit R. E., Nath A.. HspB1 and Hsc70 chaperones engage distinct tau species and have different inhibitory effects on amyloid formation. J. Biol. Chem. 2018;293:2687–2700. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M117.803411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baughman H. E. R., Pham T.-H. T., Adams C. S., Nath A., Klevit R. E.. Release of a disordered domain enhances HspB1 chaperone activity toward tau. Proc. National Acad. Sci. 2020;117:2923–2929. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1915099117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filipcik P., Cente M., Zilka N., Smolek T., Hanes J., Kucerak J., Opattova A., Kovacech B., Novak M.. Intraneuronal accumulation of misfolded tau protein induces overexpression of Hsp27 in activated astrocytes. Biochim. Biophys. acta. 2015;1852:1219–1229. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2015.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S., Zhu Y., Lu J., Liu Z., Lobato A. G., Zeng W., Liu J., Qiang J., Zeng S., Zhang Y., Liu C., Liu J., He Z., Zhai R. G., Li D.. Specific binding of Hsp27 and phosphorylated Tau mitigates abnormal Tau aggregation-induced pathology. eLife. 2022;11:e79898. doi: 10.7554/elife.79898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irwin R., Faust O., Petrovic I., Wolf S. G., Hofmann H., Rosenzweig R.. Hsp40s play complementary roles in the prevention of tau amyloid formation. eLife. 2021;10:e69601. doi: 10.7554/elife.69601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mee J. A., Gibson O. R., Tuttle J. A., Taylor L., Watt P. W., Doust J., Maxwell N. S.. Leukocyte Hsp72 mRNA transcription does not differ between males and females during heat acclimation. Temperature. 2016;3:549–556. doi: 10.1080/23328940.2016.1214336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fekete A., Vannay A., Vér A., Rusai K., Müller V., Reusz G., Tulassay T., Szabó A. J.. Sex differences in heat shock protein 72 expression and localization in rats following renal ischemia-reperfusion injury. Am. J. Physiol.-Ren. Physiol. 2006;291:F806–F811. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00080.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillum T., Kuennen M., Gourley C., Dokladny K., Schneider S., Moseley P.. Sex Differences in Heat Shock Protein 72 Expression in Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells to Acute Exercise in the Heat. Int. J. Endocrinol. Metab. 2013;11:e8739. doi: 10.5812/ijem.8739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tower J., Pomatto L. C. D., Davies K. J. A.. Sex differences in the response to oxidative and proteolytic stress. Redox Biol. 2020;31:101488. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2020.101488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarulli V., Barthold Jones J. A., Oksuzyan A., Lindahl-Jacobsen R., Christensen K., Vaupel J. W.. Women live longer than men even during severe famines and epidemics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2018;115:E832–E840. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1701535115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Périard J. D., Racinais S., Sawka M. N.. Adaptations and mechanisms of human heat acclimation: Applications for competitive athletes and sports. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports. 2015;25:20–38. doi: 10.1111/sms.12408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stice J. P., Chen L., Kim S.-C., Jung J. S., Tran A. L., Liu T. T., Knowlton A. A.. 17β-Estradiol, Aging, Inflammation, and the Stress Response in the Female Heart. Endocrinology. 2011;152:1589–1598. doi: 10.1210/en.2010-0627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bukau B., Nillegoda N., Wentink A., Ungelenk S., Ho C.-T., Mogk A.. A versatile chaperone network promoting the aggregation and disaggregation of misfolded proteins. FASEB J. 2017;31:526.2. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.31.1_supplement.526.2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Montalbano M., Jaworski E., Garcia S., Ellsworth A., McAllen S., Routh A., Kayed R.. Tau Modulates mRNA Transcription, Alternative Polyadenylation Profiles of hnRNPs, Chromatin Remodeling and Spliceosome Complexes. FASEB J. 2021;14:742790. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2021.742790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jinwal U. K., O’Leary J. C., Borysov S. I., Jones J. R., Li Q., Koren J., Abisambra J. F., Vestal G. D., Lawson L. Y., Johnson A. G., Blair L. J., Jin Y., Miyata Y., Gestwicki J. E., Dickey C. A.. Hsc70 rapidly engages tau after microtubule destabilization. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:16798–16805. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.113753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jinwal U. K., Akoury E., Abisambra J. F., O’Leary J. C., Thompson A. D., Blair L. J., Jin Y., Bacon J., Nordhues B. A., Cockman M., Zhang J., Li P., Zhang B., Borysov S., Uversky V. N., Biernat J., Mandelkow E., Gestwicki J. E., Zweckstetter M., Dickey C. A.. Imbalance of Hsp70 family variants fosters tau accumulation. FASEB J. 2013;27:1450–1459. doi: 10.1096/fj.12-220889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis A., Zhang H., Lau M., Chakraborty S., Morishima Y., Lieberman A., Osawa Y.. Activation of Heat Shock Protein 70 as a Potential Therapeutic Strategy for the Treatment of Protein Folding Disease. FASEB J. 2019;33:15–501. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.2019.33.1_supplement.501.15. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mandelkow E.-M., Mandelkow E.. Biochemistry and Cell Biology of Tau Protein in Neurofibrillary Degeneration. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2012;2:a006247. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a006247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luengo T. M., Mayer M. P., Rüdiger S. G. D.. The Hsp70-Hsp90 Chaperone Cascade in Protein Folding. Trends Cell Biol. 2019;29:164–177. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2018.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eyles S. J., Gierasch L. M.. Nature’s molecular sponges: Small heat shock proteins grow into their chaperone roles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2010;107:2727–2728. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0915160107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Straten A., Rommel C., Dickson B., Hafen E.. The heat shock protein 83 (Hsp83) is required for Raf-mediated signalling in Drosophila. EMBO J. 1997;16:1961–1969. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.8.1961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ospina S. R., Blazier D. M., Criado-Marrero M., Gould L. A., Gebru N. T., Beaulieu-Abdelahad D., Wang X., Remily-Wood E., Chaput D., Stevens S., Uversky V. N., Bickford P. C., Dickey C. A., Blair L. J.. Small Heat Shock Protein 22 Improves Cognition and Learning in the Tauopathic Brain. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022;23:851. doi: 10.3390/ijms23020851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rickner H. D., Jiang L., Hong R., O’Neill N. K., Mojica C. A., Snyder B. J., Zhang L., Shaw D., Medalla M., Wolozin B., Cheng C. S.. Single cell transcriptomic profiling of a neuron-astrocyte assembloid tauopathy model. Nat. Commun. 2022;13:6275. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-34005-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimada Y., Shimura H., Tanaka R., Yamashiro K., Koike M., Uchiyama Y., Urabe T., Hattori N.. Phosphorylated recombinant HSP27 protects the brain and attenuates blood-brain barrier disruption following stroke in mice receiving intravenous tissue-plasminogen activator. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0198039. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0198039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voegeli, T. S. ; Wintink, A. J. ; Currie, R. W. . In Heat Shock Proteins and the Brain: Implications for Neurodegenerative Diseases and Neuroprotection; Heat Shock Proteins; Springer Dordrecht, 2008; pp 159–177. [Google Scholar]

- Miyata Y., Koren J., Kiray J., Dickey C. A., Gestwicki J. E.. Molecular chaperones and regulation of tau quality control: strategies for drug discovery in tauopathies. Futur. Med. Chem. 2011;3:1523–1537. doi: 10.4155/fmc.11.88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Björkdahl C., Sjögren M. J., Zhou X., Concha H., Avila J., Winblad B., Pei J.. Small heat shock proteins Hsp27 or αB-Crystallin and the protein components of neurofibrillary tangles: Tau and neurofilaments. J. Neurosci. Res. 2008;86:1343–1352. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandelkow E.. F5-02-05: Mechanisms of tau toxicity in cell and mouse models. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2011;7:S809–S810. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.05.2335. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wyss-Coray T., Mucke L.. Inflammation in Neurodegenerative DiseaseA Double-Edged Sword. Neuron. 2002;35:419–432. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(02)00794-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asai H., Ikezu S., Tsunoda S., Medalla M., Luebke J., Haydar T., Wolozin B., Butovsky O., Kügler S., Ikezu T.. Depletion of microglia and inhibition of exosome synthesis halt tau propagation. Nat. Neurosci. 2015;18:1584–1593. doi: 10.1038/nn.4132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perea J. R., Llorens-Martín M., Ávila J., Bolós M.. The Role of Microglia in the Spread of Tau: Relevance for Tauopathies. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2018;12:172. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2018.00172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter-Landsberg C., Bauer N. G.. Tau-inclusion body formation in oligodendroglia: the role of stress proteins and proteasome inhibition. Int. J. Dev. Neurosci. 2004;22:443–451. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2004.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López-González I., Carmona M., Arregui L., Kovacs G. G., Ferrer I.. αB-Crystallin and HSP27 in glial cells in tauopathies. Neuropathology. 2014;34:517–526. doi: 10.1111/neup.12134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S.-Q., Wang P., Wang D.-M., Lu H.-J., Li R.-F., Duan L.-X., Zhu S., Wang S.-L., Zhang Y.-Y., Wang Y.-L.. Molecular mechanism for the influence of gender dimorphism on alcoholic liver injury in mice. Hum. Exp. Toxicol. 2019;38:65–81. doi: 10.1177/0960327118777869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filareti M., Luotti S., Pasetto L., Pignataro M., Paolella K., Messina P., Pupillo E., Filosto M., Lunetta C., Mandrioli J., Fuda G., Calvo A., Chiò A., Corbo M., Bendotti C., Beghi E., Bonetto V.. Decreased Levels of Foldase and Chaperone Proteins Are Associated with an Early-Onset Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2017;10:99. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2017.00099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tedesco B., Cristofani R., Ferrari V., Cozzi M., Rusmini P., Casarotto E., Chierichetti M., Mina F., Galbiati M., Piccolella M., Crippa V., Poletti A.. Insights on Human Small Heat Shock Proteins and Their Alterations in Diseases. Frontiers Mol. Biosci. 2022;9:842149. doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2022.842149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klaips C. L., Jayaraj G. G., Hartl F. U.. Pathways of cellular proteostasis in aging and disease. J. Cell Biol. 2018;217:51–63. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201709072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gandhi J., Antonelli A. C., Afridi A., Vatsia S., Joshi G., Romanov V., Murray I. V. J., Khan S. A.. Protein misfolding and aggregation in neurodegenerative diseases: a review of pathogeneses, novel detection strategies, and potential therapeutics. Rev. Neurosci. 2019;30:339–358. doi: 10.1515/revneuro-2016-0035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brehme M., Sverchkova A., Voisine C.. Proteostasis network deregulation signatures as biomarkers for pharmacological disease intervention. Curr. Opin. Syst. Biol. 2019;15:74–81. doi: 10.1016/j.coisb.2019.03.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rio D. C., Ares M., Hannon G. J., Nilsen T. W.. Purification of RNA Using TRIzol (TRI Reagent) Cold Spring Harb. Protoc. 2010;2010:prot5439. doi: 10.1101/pdb.prot5439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanguay R. M., Wu Y., Khandjian E. W.. Tissue-specific expression of heat shock proteins of the mouse in the absence of stress. Dev. Genet. 1993;14:112–118. doi: 10.1002/dvg.1020140205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.