Abstract

In contrast to peas (Pisum sativum), where mitochondrial lipoamide dehydrogenase is encoded by a single gene and shared between the α-ketoacid dehydrogenase complexes and the Gly decarboxylase complex, Arabidopsis has two genes encoding for two mitochondrial lipoamide dehydrogenases. Northern-blot analysis revealed different levels of RNA expression for the two genes in different organs; mtLPD1 had higher RNA levels in green leaves compared with the much lower level in roots. The mRNA for mtLPD2 shows the inverse pattern. The other organs examined showed nearly equal RNA expressions for both genes. Analysis of etiolated seedlings transferred to light showed a strong induction of RNA expression for mtLPD1 but only a moderate induction of mtLPD2. Based on the organ and light-dependent expression patterns, we hypothesize that mtLPD1 encodes the protein most often associated with the Gly decarboxylase complex, and mtLPD2 encodes the protein incorporated into α-ketoacid dehydrogenase complexes. Due to the high level of sequence conservation between the two mtLPDs, we assume that the proteins, once in the mitochondrial matrix, are interchangeable among the different multienzyme complexes. If present at high levels, one mtLPD might substitute for the other. Supporting this hypothesis are results obtained with a T-DNA knockout mutant, mtlpd2, which shows no apparent phenotypic change under laboratory growth conditions. This indicates that mtLPD1 can substitute for mtLPD2 and associate with all these multienzyme complexes.

Lipoamide dehydrogenase is part of the α-ketoacid dehydrogenase complexes, the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex (PDC; Luethy et al., 1996), the α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase complex, and the branched-chain α-ketoacid dehydrogenase complex, as well as the Gly decarboxylase complex (GDC; Oliver, 1994). These multienzyme complexes consist of three to four subunits (component enzymes) that are in different stoichiometric arrangements non-covalently associated with each other. The α-ketoacid dehydrogenase complexes consist of three protein components, E1 (the actual α-ketoacid dehydrogenase), E2 (the dihyrdolipoyl transacylase), and E3 (the lipoamide dehydrogenase also called dihydrolipoyl dehydrogenase). The structural organization of PDC has been studied in mammals and Escherichia coli. In mammals, PDC exists in a dodecahedral form with 60 monomers of E2 as a core unit, surrounded by 30 E1 heterodimers (E1α and E1β) and six E3 homodimers (Reed, 1998). Yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) and mammalian PDC also contain an E3 binding protein that is implicated in stabilizing the complex (Lawson et al., 1991; Stoops et al., 1997).

The GDC consist of four subunits, namely the P protein (pyridoxal 5-phosphate-dependent Gly decarboxylase), the H protein (the hydrogen carrier with the covalent bound lipoamide cofactor), the T protein (a tetrahydrofolate transferase), and the L protein (the lipoamide dehydrogenase). This complex exists in a stoichiometric arrangement of 2 P protein homodimers, 27 H protein monomers, nine T protein monomers, and one L protein homodimer with H proteins building the center core (Oliver et al., 1990b).

In these multienzyme complexes, lipoamide dehydrogenase catalyzes the reoxidation of the covalently bound lipoamide cofactor of E2 or the H protein. As a flavoprotein disulfide oxidoreductase, the homodimeric lipoamide dehydrogenase (LPD) uses FAD as cofactor and NAD+ as final electron acceptor. The electrons flow from the dihydrolipoamide to the catalytic Cys residues of one LPD subunit, supported by the active base His and its hydrogen partner, glutamate, of the other subunit, to the cofactor FAD ending up reducing NAD+ in a ping-pong bi-bi mechanism (Williams, 1992; Vettakkorumakankav and Patel, 1996).

All these multienzyme complexes are found in the mitochondria with pyruvate dehydrogenase also occurring in plastids. Because the role of lipoamide dehydrogenase is the same in all four complexes, it is not too surprising that in pea (Pisum sativum) mitochondria only one single lipoamide dehydrogenase, encoded by a single copy gene, has been found (Bourguignon et al., 1992; Turner et al., 1992b). This finding confirmed earlier work dealing with the purification of the subunits from the GDC from pea, where a monoclonal antibody against the L protein not only inhibits GDC but also PDC activity (Walker and Oliver, 1986b). It was demonstrated more recently by mass spectrometry that in pea mitochondria, the same lipoamide dehydrogenase protein is shared between the GDC and the PDC (Bourguignon et al., 1996). Finally, there is no structural interaction between the H protein and the L protein; rather, the L protein only recognizes the lipoyl moiety bound to the H protein (Faure et al., 2000; Neuburger et al., 2000). Thus, it seems reasonable that moderate differences in protein structure will not change the effectiveness of this LPD as a subunit in the complex.

On the other hand, these multienzyme complexes all play key roles in different biochemical pathways with the PDC and α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase complex controlling carbon flow in the citric acid cycle and the GDC an essential enzyme of photorespiration. This suggests different mechanisms of regulation. The genes encoding for the subunits of GDC are strongly light induced. Being part of photorespiration, GDC occurs mainly in photosynthetically active organs such as leaves and stems. mtPDC is essential in all organs and is expressed fairly evenly throughout the plant. The branched-chain α-ketoacid dehydrogenase complex in Arabidopsis has been suggested as an alternative carbon energy source important during the degradation of branched-chain amino acids during leaf senescence and during stress-induced sugar starvation (Fujiki et al., 2000).

The central role of LPD in so many pathways raises the question of how the regulation of a single copy gene encoding this protein could fulfill all these different requirements. The aim of this paper was to address this question in Arabidopsis by cloning the cDNA, performing molecular and biochemical analysis, and investigating transgenic plants.

RESULTS

Isolation and Characterization of Two cDNAs Encoding Mitochondrial Lipoamide Dehydrogenases

Two similar, but not identical, expressed sequence tag (EST) clones for mitochondrial lipoamide dehydrogenase were identified for Arabidopsis. A full-length, 1,918-bp cDNA clone was obtained for mtLPD2 that is identical to the partial EST clone T43970 (GenBank accession no. AF228640). No full-length clone identical to the second EST 120K5T7 was obtained. Reverse transcriptase (RT)-PCR with a theoretical forward primer allowed us to obtain the missing 5′ coding information of this cDNA. This cDNA was named mtLPD1 and can be found in GenBank (accession no. AF228639). Because the chromosomal information is now available, the cDNA sequence has been confirmed and updated, containing 1,734 bp, and lacking only the 5′-untranslated region (UTR).

Comparing this 1,734-bp mtLPD1 with the 1,918-bp mtLPD2, both mtLPD cDNAs have a coding sequence of 1,524 bp with a nucleotide identity of 83%. The 3′-UTR of mtLPD1 consists of 189 bp, whereas the one from mtLPD2 is 272 bp long. The identity between the two 3′-UTR is only 12%, but has stretches with perfect matches up to 14 bp long. The cloned 5′-UTR from mtLPD2 is 80 bp long.

mtLPD1 is on chromosome 1 (BAC F21D18, GenBank accession no. AC023673) and mtLPD2 on chromosome 3 (P1 clone MGD8, GenBank accession no. AB022216). Alignments of the cDNAs with their genomic sequences revealed two introns in each gene. In both cases, the first intron is 270 bp after the start codon and consists of 186 bp (mtLPD1) and 365 bp (mtLPD2). There are short stretches of identities between the two introns of up to 9-bp perfect matches with an overall 31% identity. The second intron is 11 bp (mtLPD1) or 10 bp (mtLPD2) after the stop codon consisting of 100 and 97 bp, respectively. In this case, the overall identity is 51% with up to 11 bp of perfect matches. The identities between the two genes (including within the UTRs) clearly points to recent gene duplication.

Comparison of the Two Deduced Amino Acid Sequences from the mtLPDs with LPD from Peas and Other Species Confirms Their Identity and Strongly Suggests Mitochondrial Targeting

MtLPD1 consists of 507 amino acids with a calculated molecular mass of 53,984 D. MtLPD2 is also 507 amino acids long with a calculated molecular mass of 53,982 D. The identity between the two proteins is 92%. The two mtLPDs were 85% identical to the mitochondrial LPD from peas, 53% identical to the human protein, 55% identical to the yeast protein, and 40% identical to E3 from E. coli. All conserved domains characterizing this protein can be found in both mtLPDs from Arabidopsis. The FAD-binding domain (amino acids 37–184) with its functional motif (GxGxxG/AxxxG/A) for dinucleotide binding, in the Rossmann fold, and its disulfide active site (CL/VNxGC) are present. The NAD+-binding domain (amino acids 185–315) with the motif GxGxIGxExxxVxxxxG, followed by the central domain from amino acids 316 through 384, are also present. The interface domain (amino acids 385–507) contains the active base His and the stabilizing hydrogen bond partner Glu in the signature motif (HAHPTxxE; Williams, 1992; Vettakkorumakankav and Patel, 1996).

The GDC with its LPD has been characterized at the biochemical level in peas (Walker and Oliver, 1986a, 1986b; Oliver et al., 1990a, 1990b; Bourguignon et al., 1996; Neuburger et al., 2000). The 31-amino acids-long mitochondrial targeting sequence from peas is 70% identical to the one from Arabidopsis, suggesting a mitochondrial location for the two Arabidopsis mtLPDs. Further analysis using TargetP (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/TargetP) confirmed mitochondrial location with a score of 0.919 for mtLPD1 and 0.902 for mtLPD2 and also predicted its cleavage site to be between amino acids 36 and 37 (Phe and Ala) exactly as established in peas. This means that both mature proteins are 471 amino acids long with a calculated molecular mass of 49,918 D for mtLPD1 and 49,868 D for mtLPD2.

We recently have identified the cDNAs encoding the two plastidic lipoamide dehydrogenases from Arabidopsis and have verified their location by a chloroplast uptake assay (Lutziger and Oliver, 2000). The Arabidopsis mtLPDs showed only 33% identity to the Arabidopsis ptLPDs.

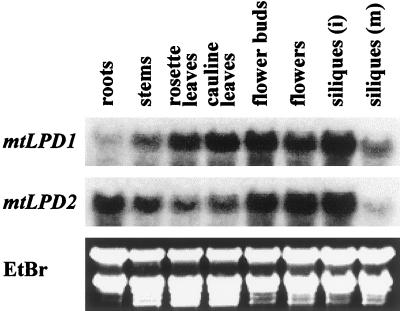

Northern Analysis of mtLPD1 and mtLPD2 Showed Differences in Organ-Specific RNA Expressions with mtLPD1 RNA Expression Being Strongly Light Induced

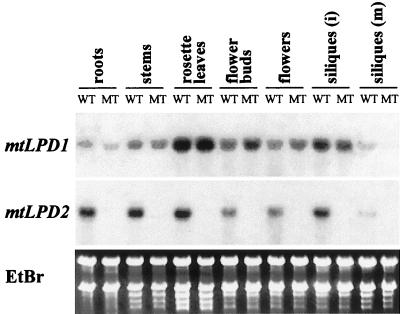

To obtain some insight into why there are two genes encoding mitochondrial lipoamide dehydrogenase, northern analyses were performed. Different organs from mature Arabidopsis plants were isolated and analyzed. Specific normalized 3′-UTR probes of each gene were used allowing direct comparison of the signals. RNA expression of mtLPD1 was much stronger in leaves compared with mtLPD2. On the other hand, much stronger RNA expression of mtLPD2 was found in roots. All other organs showed about equal RNA expressions of the two mtLPD genes (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Differential expression of mtLPD1 and mtLPD2 mRNA in organs. Northern blot representing 5 μg of RNA from different organs (i, immature; m, mature) in each lane was hybridized with the normalized specific 3′-UTR probe of each gene. Ethidium bromide staining of the gel is shown for equal loading.

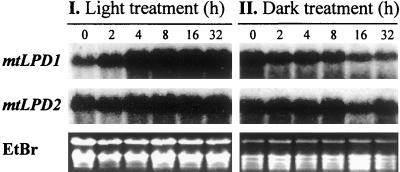

To examine the light dependence of the mRNA levels for mtLPD1 and mtLPD2, Arabidopsis plants were grown on plates either in complete darkness or under continuous light for 1 week. The plates were then transferred from the dark into light or vice versa. This transfer was set as time zero. At the time indicated after this transfer, RNA was isolated and analyzed. As can be seen in Figure 2, mtLPD1 RNA expression was strongly light induced and within 8 h reached near-maximum expression consisting of a severalfold increase. The mtLPD1 RNA expression declined rapidly in plants transferred into the dark. For comparison, there were only very slight light-dependent changes in RNA expression for mtLPD2.

Figure 2.

Light-dependent mRNA expression of mtLPD1 and mtLPD2 in Arabidopsis. Arabidopsis plants were grown in the dark for 1 week as described in “Materials and Methods” and then transferred to light (I) or grown in the light for 1 week and then transferred to the dark (II). RNA samples were taken at different times as indicated on top of each lane. Ethidium bromide staining of the gel is shown for equal loading.

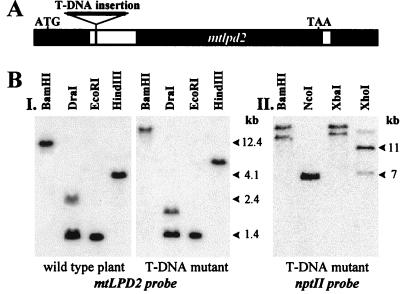

Identification of a T-DNA Knockout Mutant, mtlpd2

To determine the roles of these two mitochondrial lipoamide dehydrogenases in Arabidopsis, the Feldmann and Jack T-DNA-tagged mutant lines were screened for a line containing a T-DNA insertion into either mtLPD gene. A T-DNA-tagged mtlpd2 mutant was obtained and all further investigations were performed with a homozygous line for T-DNA-tagged mtlpd2. PCR amplification and sequencing revealed a T-DNA insertion into the first intron of mtlpd2 (Fig. 3A). A Southern blot (Fig. 3B) confirmed T-DNA insertion into mtlpd2 with a shift to increased fragment sizes, compared with wild type, with several restriction endonucleases. Southern analyses with the nptII marker gene of the T-DNA insert revealed that there were two copies of the T-DNA in mtlpd2 (Fig. 3B). It is not clear whether there are two T-DNA copies at the very same insertion site or at two different linked loci, but the two inserts never segregated through several generations.

Figure 3.

A, Schematic representation of the T-DNA insertion into mtlpd2. Black boxes represent exons and white boxes represent introns. B, Southern blot confirms T-DNA insertion into mtlpd2. Five micrograms DNA from wild-type cv Wassilewskija as well as mutant containing the T-DNA insertion in mtlpd2 were digested with the enzymes as indicated. Hybridization in I was performed with the 3′-UTR of mtLPD2. In II, 5 μg DNA was digested with different enzymes and hybridized with a nptII probe to reveal the number of T-DNA insertions.

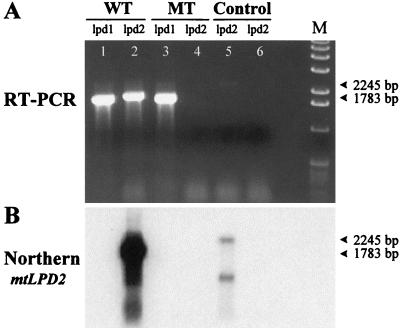

RT-PCR analysis was used to ensure the disruption of the mtlpd2 gene and complete absence of mRNA expression. As can be seen in Figure 4A, lane 4, no cDNA amplification product was visible, using mtLPD2-specific primers with the mtlpd2 mutant, but strong amplification was seen in the wild type (lane 2). As a positive control, RT-PCR was also performed with gene-specific primers for the mtLPD1 gene (lane 1 and 3). Both the wild-type plant and the mtlpd2 mutant showed the expected amplification product. Furthermore, this gel and a control gel containing a 500× more concentrated load from the RT-PCR reactions of the mtlpd2 mutant lane, were blotted on a membrane and hybridized with the gene-specific probe for mtLPD2. In both cases, strong signals could be observed in the wild-type lane (Fig. 4B), whereas no signal occurred in the mutant lanes even after exposing the blot for several days. Chromosomal contamination was visible in the control (lane 5) of the wild type only. These results strongly suggest that there is no mtLPD2 expression in this mutant.

Figure 4.

RT-PCR analysis of mtlpd2 RNA. RT-PCR was performed with a wild-type plant (WT) and a T-DNA mutant (MT) plant, using mtlpd2-specific primers (lpd2). As a control, mtLPD1-specific primers (lpd1) were used in lanes 1 and 3. The two controls in lane 5 (wild-type plant) and lane 6 (T-DNA mutant plant) were performed with mtLPD2-specific primers by subsidizing the RT/Taq Mix with Taq DNA polymerase. The northern blot (B) derived from A was hybridized with 3′-UTR of mtLPD2.

T-DNA-Tagged Knockout mtlpd2 Mutant Had No Apparent Morphological Phenotype

The T-DNA-tagged knockout mtlpd2 mutant was investigated for potential phenotypes. Mutant and wild-type plants were grown to maturity in a mosaic order (alternating order of wild-type and mutant plants in a tray) in a growth chamber at 21°C under continuous light. No apparent phenotype was observed at any developmental stage. The total weight of the different organs and the developmental time course were measured for a number of single plants and no significant differences were found. Because mtLPD1 was strongly light induced, the growth of the mutant plants in the dark was measured. There were no significant differences in germination or growth of the etiolated plants. Because mtLPD2 is more strongly expressed in roots than mtLPD1, root growth was analyzed in liquid shaker culture. Mutant and wild-type plants were grown in the dark in liquid culture containing one-half-strength Murashige and Skoog salts. There were no differences in growth rate or root biomass over a 4-week period.

It is possible that stronger expression of mtLPD1 in the mtlpd2 mutant than in wild-type plants could compensate for the lack of mtLPD2. mRNA levels were examined in different organs in mutant and wild-type plants (Fig. 5). The mtlpd2 mutant plants did not show elevated mRNA except for a slight increase in mRNA levels in flower buds or flowers. As a control, it can be seen that mtLPD2 mRNA is only present in wild-type plants.

Figure 5.

mtLPD RNA expression in different organs comparing wild type and T-DNA mutant, mtlpd2. Five micrograms of RNA from different organs was loaded in each lane with WT representing wild type and MT the mtlpd2 mutant. Hybridization was performed with the 3′-UTR of each gene as indicated. Ethidium bromide staining shows equal RNA loading.

Total LPD activity was measured from roots and etiolated plants of the mtlpd2 mutant and wild-type plants to see if there were any biochemical phenotypes associated with the mutation. Two-week-old roots grown in liquid culture from mtlpd2 mutants had only 38% of the LPD activity found in wild-type plants. Four- to 6-week-old liquid culture mtlpd2 mutant roots had 85% of the wild-type LPD activity. Etiolated mtlpd2 mutant plants showed 71% of the LPD activity compared with wild-type plants (Table I).

Table I.

Comparison of LPD activity in wild-type and T-DNA mtlpd2 mutant plants

| Organs | Wild-Type Arabidopsis cv Wassilewskija | mtlpd2 T-DNA Knockout Mutant | Percenta |

|---|---|---|---|

| μmol NADH mg tissue min−1 | |||

| Roots (young) | 0.0220 ± 0.0048 | 0.0083 ± 0.0012 | 38b |

| Roots (old) | 0.0143 ± 0.0044 | 0.0121 ± 0.0030 | 85 |

| Etiolated plants | 0.0202 ± 0.0028 | 0.0143 ± 0.0038 | 71b |

The data were obtained in triplicate, from flasks each containing 10 to 20 seedlings, and the whole experiment was repeated twice.

Percentages are calculated based on wild type being 100%.

Difference between wild type and mutant significant at P < 0.05.

CO2 release assays were used to see if the decrease in LPD activity measured in mtlpd2 mutants was associated with a specific multienzyme complex (Table II). With [1-14C]pyruvate as the substrate, there were no differences in 14CO2 release between wild-type and mutant plants. When [1-14C]Gly was substrate, mutant plants showed only about 75% the rate of 14CO2 release measured with wild-type plants.

Table II.

Comparison of 14CO2 release from [1-14C]pyruvate or [1-14C]glycine from wild-type and T-DNA mtlpd2 mutant plants

| Wild-Type Arabidopsis cv Wassilewskija | mtlpd2 T-DNA Knockout Mutant | Percenta | |

|---|---|---|---|

| pmole CO2 mg root h−1 | |||

| [1-14C]Pyruvate: 14CO2 release | |||

| 76.1 ± 13.1 | 77.3 ± 5.8 | 102 | |

| 59.5 ± 8.2 | 62.3 ± 3.4 | 105 | |

| 61.4 ± 7.5 | 58.8 ± 4.1 | 96 | |

| 65.6 ± 12.0 | 66.1 ± 9.3 | 101 | |

| [1-14C]Gly: 14CO2 release | |||

| 0.263 ± 0.046 | 0.207 ± 0.049 | 79 | |

| 0.212 ± 0.065 | 0.165 ± 0.031 | 78 | |

| 0.142 ± 0.079 | 0.103 ± 0.039 | 73 | |

| 0.179 ± 0.073 | 0.134 ± 0.046 | 75b | |

Each data set represents independent experiments using at least five different mutant and wild-type root samples. The roots used have the same developmental stage in each data set, but are of increasing age in the following lanes. The nos. in bold represents the average of the data from those three experiments.

Percentages are calculated based on wild type being 100%.

Difference between wild type and mutant significant at P < 0.05.

DISCUSSION

Molecular and biochemical analyses of lipoamide dehydrogenase in peas indicated a single isozyme encoded by a nuclear single-copy gene (Walker et al., 1986a; Bourguignon et al., 1992, 1996). Because this flavoprotein is a subunit of several multienzyme complexes playing crucial roles in different metabolic pathways, we wanted to investigate the regulation of such a gene. Because transformational techniques are well established in Arabidopsis, in contrast to pea, we investigated this question in this organism.

Arabidopsis has two nuclear-encoded mitochondrial lipoamide dehydrogenase genes. The two mtLPD cDNAs are very similar and have the same intron pattern. Both mtLPDs show all the domains necessary for LPD to perform its enzymatic function (Carothers et al., 1989; Williams, 1992; Vettakkorumakankav and Patel, 1996).

The Arabidopsis mtLPDs have 85% identity to the pea mitochondrial LPD but only 33% identity to their own plastidic counterparts (Lutziger and Oliver, 2000). In plastids, the only known multienzyme complex containing LPD is the plastidic PDC. There are two nuclear-encoded single-copy genes encoding for the plastidic LPDs, ptLPD1 and ptLPD2. The plastidic E2 (Mooney et al., 1999) as well as the plastidic E1α and E1β (Johnston et al., 1997) all show approximately 30% identity with the equivalent subunit from the mitochondria but 60% identity with the commensurate cyanobacterial gene. The greater similarity of all the ptPDC subunits to those from cyanobacteria than to the mitochondrial genes with the same functions reinforces the different evolutionary origin of the mitochondrial (endosymbiosis of an ancestral proteobacteria) versus the plastidic (endosymbiosis of an ancestral cyanobacteria) lipoamide dehydrogenases in Arabidopsis.

The finding of two genes encoding lipoamide dehydrogenase in Arabidopsis instead of just one as in peas opened the possibility that mtLPD1 and mtLPD2 encode subunits for specific multienzyme complexes. Northern analysis of RNA isolated from different organs showed that the expression of mtLPD1 was favored in leaves, whereas mtLPD2 expression was higher in roots. In other organs, stems, flower buds, flowers, and siliques, only slight differences were observed. mtLDP1 expression was also much more light dependent than expression of mtLPD2.

mtLPD2 expression seems to be similar to that of the other subunits of the α-ketoacid complexes. The RNA pattern for mtLPD2 with stronger expression in roots than in leaves was also observed with the genes encoding mitochondrial E1α and E1β of PDC (Luethy et al., 1994, 1995). mtLPD1 expression is very similar to that of the P protein and H protein of the GDC with higher expression levels in leaves and strong light induction of gene transcription (Kim and Oliver, 1990; Macherel et al., 1990; Turner et al., 1992a, 1993; Vauclare et al., 1996, 1998).

In peas, the level of mRNA (Bourguignon et al., 1992; Turner et al., 1992b) and the enzyme activity (Walker and Oliver, 1986b) for the L protein showed a lower amount of light induction and organ differentiation than for the other component proteins of GDC. In Arabidopsis, mtLPD1 seems to co-express with the P protein and H protein of GDC, whereas mtLPD2 has an expression pattern more similar to the α-ketoacid dehydrogenase complexes. The combined amount of mtLPD1 and mtLPD2, however, looks like the expression of the single L protein gene in peas with lower fold changes in the light and less organ-specific expression.

To test this model that mtLPD1 mainly made L protein for GDC, whereas mtLPD2 produced E3 for the α-ketoacid dehydrogenases, a T-DNA knockout mutant, mtlpd2, was obtained. Although the T-DNA insertion occurred in the first intron of mtlpd2, no mtlpd2 RNA was detectable by RT-PCR in the T-DNA mutants. The mutation had no visible effect on the plants. The mutant plants showed normal developmental growth with no difference in the weight of mature organs. This was even true for roots and etiolated plants where the mtLPD2 expression was strongest. The only differences observed were at the biochemical level. LPD activity was decreased in the mtlpd2 mutant. Younger roots, with 38% of the LPD enzyme activity of wild-type roots, were more strongly affected than older roots with 85% of the wild-type activity. This implies that the ratio of the two mtLPDs contributing LPD activity varied at different developmental stages. mtLPD2 activity was higher in young roots than in older ones.

The only difference observed between the mtlpd2 mutant and wild-type plants was a 25% decrease in GDC activity measured as 14CO2 release from [1-14C] Gly and not the change in PDC activity predicted. This could be explained by the fact that the 92% identity between the two mtLPDs does not distinguish them once the proteins are within the mitochondria so that they can be associated with either multienzyme complexes. The subunits of the GDC are not bound together tightly and readily dissociate in vitro. There is no interaction between the H protein and the L protein; the L protein only recognizes the lipoamide moiety bound to the H protein, not the H protein itself (Faure et al., 2000). The situation is different with the PDC. In mammals, and possibly in plants (Luethy et al., 1996), the E3-binding protein is responsible for a tight association of LPD with the E2 subunit. As a result, the interactions between the different subunits in the α-ketoacid dehydrogenase complexes are more stable than those in GDC and these complexes do not dissociate as readily in vitro. This could explain why the PDC would retain activity in a mtlpd2 mutant, whereas GDC would not. The tighter interactions of the PDC subunits and the E3-binding protein would keep the mtLPDs associated to these complexes, whereas in the mtlpd2 mutant only the leftover mtLPDs not in PDC would be available to GDC. GDC activity would decrease, whereas PDC activity would be affected less.

Under normal conditions, the mtLPD1 appears to be regulated to supply L protein when GDC is being made and mtLPD2 is controlled in such a manner that it is producing E3 protein when the α-ketoacid dehydrogenases are being synthesized. The LPD proteins, however, are so similar that once they are made they can work in either multienzyme complex.

No T-DNA-tagged mtlpd1 mutants were found. This was not surprising because we assumed that a homozygous knockout mtlpd1 mutant would probably be lethal. In photosynthetically active leaves, GDC makes up 30% to 50% of the total matrix protein, thus requiring strong expression of the mtLPD genes to provide sufficient protein. If this is also the case in Arabidopsis, the low level of mtLPD2 mRNA expressed in leaves would not be able to satisfy the need for mtLPDs to sustain photorespiration, resulting in a lethal mutation.

Searching the Arabidopsis Database, we found that one gene encoding for the H protein (GDCH) as well as one gene encoding for the P protein (GDCP) are located on chromosome 2. Another GDCP gene was found on chromosome 4 and a second H protein gene on chromosome 1. The gene encoding for the T protein was located on chromosome 1. In peas, it has been shown that the GDCT and GDCL are linked together on chromosome 7, whereas GDCP and GDCH can be found on different chromosomes (Turner et al., 1993). Single-copy genes are reported for all of the subunits encoding GDC in peas. This is in contrast to Arabidopsis, where we found two genes encoding for the H, L, and P proteins and one for the T protein.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Isolation and Characterization of the cDNAs Encoding mtLPDs

The cDNA encoding the L protein from peas (Pisum sativum, GenBank accession no. X63464) was used to search for EST clones from Arabidopsis via BLAST at The Arabidopsis Information Resource (http://www.arabidopsis.org). Two partial EST clones were obtained from the Arabidopsis Biological Resource Center (ABRC, Columbus, OH; clone 120K5T7, GenBank accession no. T43970; clone 104E16T7, GenBank accession no. T22366). These partial genes were used as probes to screen a λPRL2 library using standard techniques (Sambrook et al., 1989) and one full-length clone was isolated. This cDNA was sequenced and named mtLPD2 (GenBank accession no. AF228640). The missing 5′ end of the other gene, mtLPD1 (GenBank accession no. AF228639), was obtained by RT-PCR as described previously (Lutziger and Oliver, 2000) using a forward primer starting right after the start codon designed according to mtLPD2 (5′-GCGATGGCGAGCTTAGCTAGG-3′).

Northern Analysis

Total RNA from different organs and at different developmental stages were all isolated from Arabidopsis and northern analysis performed as described previously (Lutziger and Oliver, 2000). For the light-dependent expression studies, Arabidopsis seeds were sterilized with 70% (v/v) ethanol for 15 s followed by incubation in 50% to 60% (v/v) bleach containing a few drops of 10% (w/v) SDS for 10 to 15 min and rinsed several times with sterile water. Seeds were then plated out on germination medium (one-half-strength Murashige and Skoog Salt Mixture [GibcoBRL, Carlsbad, CA], pH 5.6–5.8, and 2 g L−1 phytagel [Sigma, St. Louis]). One-week-old seedlings either grown in the dark at room temperature or in continuous light at 21°C were then transferred, set at time 0 h, either from the dark into the light or vice versa. RNA samples were then taken at different times after the transfer with a control at time zero.

T-DNA-Tagged mtlpd2 Mutant Isolation

The T-DNA pools containing DNA from about 6,000 T-DNA lines generated by Feldmann, as described in the ABRC Seed and DNA Catalog (1997), with the 3850:1003 Ti plasmid in the Wassilewskija background were obtained from the ABRC at the Ohio State University (stock number: CD5-7). PCR analysis was performed using the provided T-DNA left and right border-specific primers in combination with mtLPD gene-specific primers to search for possible T-DNA insertion in either mtLPD gene. A strong PCR band of about 500 bp was found in one pool using the left T-DNA border primer and a forward mtLPD (5′-GCGATGGCGAGCTTAGCTAGG-3′)-specific primer. The PCR fragment was isolated, sequenced, and revealed T-DNA insertion into first intron of mtlpd2. This line was isolated.

RT-PCR Analysis of mtLPD mRNA

Total RNA was isolated from individual Arabidopsis (ecotype Wassilewskija) and from individual T-DNA mtlpd2 mutants using the TRIZOL LS reagent from GibcoBRL/Life Technologies (Carlsbad, CA) according to their instructions. The SUPERSCRIPT One-Step RT-PCR System (GibcoBRL/Life Technologies) was then used to examine the presence or absence of mtLPD mRNA in the individual plants. The primers used were a common forward primer (5′-GCGATGGCGAGCTTAGCTAGG-3′) designed after the start codon of mtLPD genes and a 3′-UTR specific reverse primer with 5′-GATCAGGCTTAACACGTATCTG-3′ for mtLPD1 and 5′-CACCGATCATACCTGATTAATCAC-3′ for mtLPD2. These primers were chosen to distinguish the cDNA from the genomic DNA with its two introns.

LPD Activity Assay

Sterilized Arabidopsis seeds were germinated in 100-mL Erlenmeyer flasks containing 40 mL liquid culture consisting of one-half-strength Murashige and Skoog salt mixture from GibcoBRL and 2.5 mm MES [2-(N-morpholino)-ethanesulfonic acid] adjusted to pH 5.8.

The forward reaction of LPD activity, increase in NADH, was measured spectrophotometrically at 320 nm using a DU 7400 (Beckman, Fullerton, CA). Dihydrolipoamide was prepared as described by Butterworth et al. (1975) and dissolved in ethanol to a final concentration of 10 mm. The enzyme was extracted from organs in 150 mm KPi (pH 8.0) and 0.5% (v/v) Triton X-100. Reaction buffer consisted of 50 mm KPi (pH 8.0), 0.25 mm NAD+, and 1.5 mm EDTA. The reaction buffer (970 μL) was mixed with 10 μL of organ extract and the reaction rate was measured for 1 min (control). Then, 20 μL dihydrolipoamide was added and the reaction rate was measured for another minute. Total protein was measured using the bicinchoninic acid protein assay by Pierce (Rockford, IL).

Radioactive CO2 Release Assay

Sterile Arabidopsis seeds were germinated as described above. After growth on a shaker for 3 to 4 weeks, roots were collected and about 100 mg was distributed into 25-mL Erlenmeyer flasks containing 2 mL of water and either plus 20 μL [1-14C]pyruvate-Na (2.9 × 105 cpm μmole−1:0.132 mCi mmol−1 measured) or 5 μL [1-14C]Gly (52.4 mCi mmol−1). After 10 min of vacuum infiltration, the Erlenmeyer flasks were closed with rubber stoppers containing plastic filter holders, in which small pieces of 3-MM paper were inserted. Immediately before capping, 20 μL of 70% (v/v) triethanolamine was added to the filter. The flasks were shaken for 2 h at room temperature, at which time the feeding experiment was stopped by adding 100 μL of 1 m sulfuric acid. After an additional hour of shaking, the filter papers were transferred into 5 mL of liquid-scintillation cocktail (Ready Safe by Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA) and radioactive CO2 release was counted in the Multi-Purpose Scintillation Counter LS 6500 by Beckman. Data were collected and analyzed with InStat Instant Biostatistics by GraphPad Software, Inc. (San Diego).

Footnotes

This research was supported by the U.S. Department of Agriculture National Research Initiative Competitive Grants Office and is a publication of the Iowa Agricultural Experiment Station.

Article, publication date, and citation information can be found at www.plantphysiol.org/cgi/doi/10.1104/pp.010321.

LITERATURE CITED

- Bourguignon J, Macherel D, Neuburger M, Douce R. Isolation, characterization, and sequence analysis of a cDNA clone encoding L-protein, the dihydrolipoamide dehydrogenase component of the glycine cleavage system from pea-leaf mitochondria. Eur J Biochem. 1992;204:865–873. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1992.tb16706.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourguignon J, Merand V, Rawsthorne S, Forest E, Douce R. Glycine decarboxylase and pyruvate dehydrogenase complexes share the same dihydrolipoamide dehydrogenase in pea leaf mitochondria: evidence from mass spectrometry and primary-structure analysis. Biochem J. 1996;313:229–234. doi: 10.1042/bj3130229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butterworth PJ, Tsai CS, Eley MH, Roche TE, Reed LJ. A kinetic study of dihydrolipoyl transacetylase from bovine kidney. J Biol Chem. 1975;250:1921–1925. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carothers DJ, Pons G, Patel MS. Dihydrolipoamide dehydrogenase: functional similarities and divergent evolution of the pyridine nucleotide-disulfide oxidoreductases. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1989;268:409–425. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(89)90309-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faure M, Bourguignon J, Neuburger M, Macherel D, Sieker L, Ober R, Kahn R, Cohen-Addad C, Douce R. Interaction between the lipoamide-containing H-protein and the lipoamide dehydrogenase (L-protein) of the glycine decarboxylase multienzyme system: 2. Crystal structures of H- and L-proteins. Eur J Biochem. 2000;267:2890–2898. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2000.01330.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujiki Y, Sato T, Ito M, Watanabe A. Isolation and characterization of cDNA clones for the E1 beta and E2 subunits of the branched-chain alpha-ketoacid dehydrogenase complex in Arabidopsis. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:6007–6013. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.8.6007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston ML, Luethy MH, Miernyk JA, Randall DD. Cloning and molecular analyses of the Arabidopsis thaliana plastid pyruvate dehydrogenase subunits. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1997;1321:200–206. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(97)00059-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y, Oliver DJ. Molecular cloning, transcriptional characterization, and sequencing of cDNA encoding the H-protein of the mitochondrial glycine decarboxylase complex in peas. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:848–853. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawson JE, Behal RH, Reed LJ. Disruption and mutagenesis of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae PDX1 gene encoding the protein X component of the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex. Biochem. 1991;30:2834–2839. doi: 10.1021/bi00225a015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luethy MH, Miernyk JA, David NR, Randall DD. Plant pyruvate dehydrogenase complexes. In: Patel MS, Roche TE, Harris RA, editors. Alpha-Keto Acid Dehydrogenase Complexes. Basel: Birkhauser Verlag; 1996. pp. 71–92. [Google Scholar]

- Luethy MH, Miernyk JA, Randall DD. The nucleotide and deduced amino acid sequences of a cDNA encoding the E1 beta-subunit of the Arabidopsis thaliana mitochondrial pyruvate dehydrogenase complex. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1994;1187:95–98. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(94)90171-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luethy MH, Miernyk JA, Randall DD. The mitochondrial pyruvate dehydrogenase complex: nucleotide and deduced amino-acid sequences of a cDNA encoding the Arabidopsis thaliana E1 alpha-subunit. Gene. 1995;164:251–254. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00465-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutziger I, Oliver DJ. Molecular evidence of a unique lipoamide dehydrogenase in plastids: analysis of plastidic lipoamide dehydrogenase from Arabidopsis thaliana. FEBS Lett. 2000;484:12–16. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)02116-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macherel D, Lebrun M, Gagnon J, Neuburger M, Douce R. cDNA cloning, primary structure and gene expression for H-protein, a component of the glycine-cleavage system (glycine decarboxylase) of pea (Pisum sativum) leaf mitochondria. Biochem J. 1990;268:783–789. doi: 10.1042/bj2680783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mooney BP, Miernyk JA, Randall DD. Cloning and characterization of the dihydrolipoamide S-acetyltransferase subunit of the plastid pyruvate dehydrogenase complex (E2) from Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 1999;120:443–452. doi: 10.1104/pp.120.2.443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuburger M, Polidori AM, Pietre E, Faure M, Jourdain A, Bourguignon J, Pucci B, Douce R. Interaction between the lipoamide-containing H-protein and the lipoamide dehydrogenase (L-protein) of the glycine decarboxylase multienzyme system: 1. Biochemical studies. Eur J Biochem. 2000;267:2882–2889. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2000.01301.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver DJ. The glycine decarboxylase complex from plant mitochondria. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 1994;45:323–337. [Google Scholar]

- Oliver DJ, Neuburger M, Bourguignon J, Douce R. Glycine metabolism by plant mitochondria. Physiol Plant. 1990a;80:487–491. [Google Scholar]

- Oliver DJ, Neuburger M, Bourguignon J, Douce R. Interaction between the component enzymes of the glycine decarboxylase multienzyme complex. Plant Physiol. 1990b;94:833–839. doi: 10.1104/pp.94.2.833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed LJ. From lipoic acid to multi-enzyme complexes. Protein Sci. 1998;7:220–224. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560070125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J, Fritsch E, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: A Laboratory Approach. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Stoops JK, Cheng RH, Yazdi MA, Maeng CY, Schroeter JP, Klueppelberg U, Kolodziej SJ, Baker TS, Reed LJ. On the unique structural organization of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae pyruvate dehydrogenase complex. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:5757–5764. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.9.5757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner SR, Hellens R, Ireland R, Ellis N, Rawsthorne S. The organisation and expression of the genes encoding the mitochondrial glycine decarboxylase complex and serine hydroxymethyltransferase in pea (Pisum sativum) Mol Gen Genet. 1993;236:402–408. doi: 10.1007/BF00277140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner SR, Ireland R, Rawsthorne S. Cloning and characterization of the P subunit of glycine decarboxylase from pea (Pisum sativum) J Biol Chem. 1992a;267:5355–5360. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner SR, Ireland R, Rawsthorne S. Purification and primary amino acid sequence of the L subunit of glycine decarboxylase: evidence for a single lipoamide dehydrogenase in plant mitochondria. J Biol Chem. 1992b;267:7745–7750. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vauclare P, Diallo N, Bourguignon J, Macherel D, Douce R. Regulation of the expression of the glycine decarboxylase complex during pea leaf development. Plant Physiol. 1996;112:1523–1530. doi: 10.1104/pp.112.4.1523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vauclare P, Macherel D, Douce R, Bourguignon J. The gene encoding T protein of the glycine decarboxylase complex involved in the mitochondrial step of the photorespiratory pathway in plants exhibits features of light-induced genes. Plant Mol Biol. 1998;37:309–318. doi: 10.1023/a:1005954200042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vettakkorumakankav N, Patel MS. Dihydrolipoamide dehydrogenase: structural and mechanistic aspects. Indian J Biochem Biophys. 1996;33:168–176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker JL, Oliver DJ. Glycine decarboxylase multienzyme complex. Purification and partial characterization from pea leaf mitochondria. J Biol Chem. 1986a;261:2214–2221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker JL, Oliver DJ. Light-induced increases in the glycine decarboxylase multienzyme complex from pea leaf mitochondria. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1986b;248:626–638. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(86)90517-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams CH., Jr . Lipoamide dehydrogenase, glutathione reductase, thioredoxin reductase, and mercuric ion reductase: a family of flavoenzyme transhydrogenases. In: Mueller F, editor. Chemistry and Biochemistry of Flavoenzymes. Vol. 3. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 1992. pp. 121–211. [Google Scholar]