Abstract

Introduction

Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) is the leading cause of acute lower respiratory tract infection in infants. This study examined the preferences of Dutch parents and expectant parents for two RSV prevention strategies for infant protection: a maternal vaccine versus an infant monoclonal antibody (mAb) injection.

Methods

An online survey including a discrete choice experiment was conducted. Participants chose between two immunisation options for ‘a common virus among infants’ that represented RSV. These differed based on six attributes: timing and recipient of the injection, costs, recommended by a healthcare provider (HCP), included in the National Immunisation Programme (NIP), administration location, and co-administered with other injections. The main outcomes were preference weights, conditional relative attribute importance (CRAI), and willingness to be immunised.

Results

The survey was completed by 150 participants (90% female; 49% parents; 51% expectant parents; mean age 31.23 ± 5.61 years). Participants preferred an immunisation option that is administered to pregnant women [mean = 1.48 (95% confidence interval (CI) 1.18–1.82)], free of charge [mean = 1.36 (95% CI 1.10–1.67)], recommended by an HCP [mean = 0.50 (95% CI, 0.34–0.66)], and included in the NIP [mean = 0.42 (95% CI, 0.26–0.58)]. The most important attributes were timing and recipient of the injection [CRAI = 32% (95% CI, 28–35%)] and costs [CRAI = 24% (95% CI, 20–28%)]. Willingness to be immunised was higher when the maternal vaccine and infant mAb injection were in the NIP than when only the infant mAb injection was available (89% vs 74%).

Conclusions

The results suggest that most Dutch parents and expectant parents would prefer a maternal vaccine to an infant mAb injection to immunise their infants against an RSV-like virus. An NIP that incorporates both strategies may enhance uptake and protect the most infants. However, as the attributes were not exhaustively or explicitly presented in the context of RSV prevention, the results may not be completely transferable.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s40121-025-01214-2.

Keywords: Discrete choice experiment, Infant immunisation, Monoclonal antibody, Nirsevimab, Preference, Pregnancy, Respiratory syncytial virus, RSVpreF maternal vaccination, Vaccine

Key Summary Points

| Why carry out this study? |

| Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) is the leading cause of acute lower respiratory tract infection in infants. |

| Understanding the preferences of parents and expectant parents for RSV prevention strategies is crucial for guiding decisions about National Immunisation Programmes (NIPs) in the Netherlands and other countries, as these preferences are likely to impact uptake. |

| What was learned from the study? |

| Most Dutch parents and expectant parents preferred a maternal vaccine in pregnancy to an infant injection to protect their infants against a common virus that represented RSV. |

| Overall willingness to be immunised was higher in a hypothetical scenario where both RSV prevention strategies were available in the NIP than in a hypothetical scenario where only the infant injection was available. |

| An NIP incorporating both strategies may enhance uptake, protect the most infants, and improve public health outcomes. |

Introduction

Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) is the leading cause of acute lower respiratory tract infection (LRTI) in children [1, 2]. Almost all children experience an RSV infection at least once before the age of 2 years [3, 4]. Common symptoms include coughing, sneezing, and fever [5], but an RSV infection can be fatal or cause serious illnesses such as pneumonia or bronchiolitis [2, 3]. Each year in Europe, one in 56 healthy term-born infants is hospitalised with RSV in the first year of life [6]. Furthermore, approximately 60% of RSV-associated hospitalisations occur in infants younger than 3 months [6].

RSV prevention strategies include a monoclonal antibody (mAb) injection administered to infants and a vaccine administered to pregnant women [4]. These strategies provide passive immunisation of the infant in different ways. For the maternal vaccine, antibodies are produced by pregnant women and transferred to the foetus in the uterus during pregnancy, whereas for the mAb injection, manufactured antibodies are injected into the infant after birth [4]. In October 2022, the mAb nirsevimab was approved in the European Union (EU) [7]. Nirsevimab is administered as a single injection to infants up to 1 year of age to protect them during their first RSV season [7]. In an international phase 3, randomised, placebo-controlled trial conducted in 20 countries, nirsevimab reduced the risk of medically attended RSV-associated LRTI within 5 months after the injection (efficacy of 75%) [8]. In August 2023, the bivalent RSV prefusion F (RSVpreF) maternal vaccine was approved in the EU [9]. The RSVpreF maternal vaccine is administered as a single injection to pregnant women during the third trimester (between weeks 24–36 of gestation) to protect infants against RSV from birth through 6 months of age [9]. In a phase 3, randomised, placebo-controlled trial conducted in 18 countries, including the Netherlands, the maternal vaccine reduced the risk of RSV-associated medically attended LRTI in infants within 6 months after birth (efficacy of 70%) [10, 11].

Understanding the preferences of parents and expectant parents is important to help guide national healthcare decisions about which RSV prevention strategies to offer them. These preferences are likely to impact uptake and the success of National Immunisation Programmes (NIPs) that aim to protect infants from RSV [12]. In the Netherlands, as of 23 April 2025, neither RSV prevention strategy is currently available to parents through the NIP, and only the RSVpreF maternal vaccine is currently available to pregnant women at their own expense [13, 14]. The Health Council of the Netherlands intends to roll out the infant mAb injection in the NIP in autumn/winter 2025.

One Dutch survey directly compared the preferences of approximately 1000 pregnant women and their partners for an RSV maternal vaccine versus an RSV infant mAb injection and found that approximately 70% preferred an RSV maternal vaccine to an RSV infant mAb injection [15]. Few studies have quantified preferences for RSV prevention strategies using a discrete choice experiment (DCE) [16, 17], which is a more effective method for measuring preferences than surveys. In a DCE, participants choose between hypothetical product profiles that have different product features (attributes) and subcategories (levels) in a series of choice tasks [16, 18]. This provides information about the relative importance of different attributes and the trade-offs that participants make between attributes [16, 18].

Using a DCE, the current study examined preferences of Dutch parents and expectant parents (hereafter ‘parents’) for a maternal vaccine versus an infant mAb injection to immunise their infants against a common virus that represented RSV.

Methods

Study Design

This was a cross-sectional, online survey, including a DCE, administered in the Netherlands between July 10 and August 15, 2024. The study estimated the relative importance of RSV prevention strategy attributes to parents, predicted parents’ willingness for pregnant women to be vaccinated and infants to be immunised (hereafter ‘willingness to be immunised’) using hypothetical scenarios, and identified latent groups of parents with similar preferences. The study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the European Pharmaceutical Market Research Association and the Dutch Market Research Association. The study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the European Pharmaceutical Market Research Association and the Dutch Market Research Association. Ethical approval for this study was not required, in accordance with the Dutch Medical Research Involving Human Subjects Act. Participants provided informed consent to participate in the study (electronic checkbox consent) [19].

Participants

The study included pregnant women, male partners of pregnant women, and mothers and fathers of infants. Women were included if they were aged 18–49 years and were currently pregnant or had an infant aged 0–6 months. Men were included if they were aged 18–59 years, had a partner who was currently pregnant or an infant aged 0–6 months, and reported being involved in decisions (e.g., immunisation decisions) during their partner’s pregnancy. Participants were recruited through an online consumer market research panel. The recruitment target was 150 participants, which was considered feasible for the recruitment approach (online panel) and timeframe (1 month). Recruitment quotas were 45% for pregnant women, 45% for mothers of infants, and 10% for male partners of pregnant women and fathers of infants. A 9:1 female:male ratio was chosen to reflect the voices of men and women as well as the primary influence of mothers on immunisation decisions across cultures [20, 21].

Procedures

Potential participants provided electronic checkbox consent, and then they completed a brief screening survey to determine eligibility. Those who were eligible were directed to the main survey. Participants answered questions about their awareness of and attitudes towards immunisations, completed the DCE, and answered demographic questions. The main survey took approximately 15 min to complete. Participants were reimbursed EUR (€) 5.36 for their time.

DCE Design

The study was conducted in accordance with the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research guidelines for constructing experimental designs for DCEs [22] and the Innovative Medicines Initiative-Patient Preferences in Benefit-Risk Assessments during the Drug Life Cycle project framework [23]. The DCE design was informed by a literature review and pretest interviews, following best-practice guides [24].

The results of the literature review were refined based on pretest interviews with a pregnant woman, a mother of an infant, and a father of an infant. This process included determining the duration of the survey, the relevance of the questions, the ease of answering the questions, and the possible reasons for participants’ preferences. The relevance, completeness, and accuracy of the DCE attributes and levels were evaluated. A moderator guided the three participants through a draft version of the survey, and participants were asked to verbalise their thoughts while completing this. The pretest interviews lasted 45 min, and participants were reimbursed €20. Some small adjustments were made to the DCE attributes and levels following the feedback from participants during the pretest interviews. The final DCE included six attributes: timing and recipient of the injection, costs in euros, recommended by a healthcare provider (HCP), included in the NIP, administration location, and co-administered with other injections. Each attribute had up to four levels (Table 1).

Table 1.

Attributes and levels of the discrete choice experiment

| Attribute | Level | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| Timing and recipient of the injection | To your infant within 24 h after birth, protected shortly after administration for approximately 6 months. Potential adverse events for the infant | To your infant within 2 weeks after birth, protected shortly after administration for approximately 6 months. Potential adverse events for the infant | To your infant within 1 month after birth, protected shortly after administration for approximately 6 months. Potential adverse events for the infant | To the mother during pregnancy, protected directly after birth for approximately 6 months. Potential adverse events for the mother, not for the infant |

| Costs (€) | 0 | 130 | 180 | 230 |

| Recommended by an HCP | Recommended by a doctor or nurse | Not mentioned by a doctor or nurse | ||

| Included in the NIP | Included in the NIP (you receive an invitation automatically) | Not included in the NIP (you need to request the injection yourself through your doctor or child health clinic) | ||

| Administration location | Child health clinic | At home | GP’s office | Municipal Health Services |

| Co-administered with other injections | Co-administered with other injections from the NIP (but as an additional injection) | Not co-administered with any other injections | ||

GP general practitioner, HCP healthcare provider, NIP National Immunisation Programme

Fifty versions of the DCE were designed. Each participant was randomly allocated to one of the 50 versions. Each version consisted of ten choice tasks that were generated using a balanced overlap design algorithm. The balanced overlap design selects combinations of attribute levels so that each level is shown (and shown with other levels) nearly an equal number of times [25]. It also permits some level of repetition within each choice task; sometimes the same attribute level appears for both options.

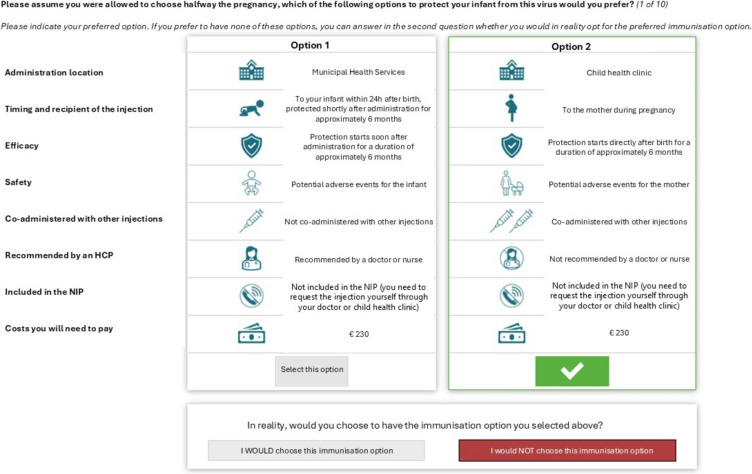

In each choice task, two hypothetical immunisation options were presented together on screen (Fig. 1). The options were framed in the context of a general common virus among infants rather than RSV specifically. Each option was characterised by assigned levels on all six attributes. To avoid confusing participants, the order of attributes within options was not randomised. The two options were assumed to be similar on other features not covered by the six attributes. Timing and recipient of the injection consisted of multiple linked aspects that were included together in this attribute. For example, safety (potential adverse events for the mother vs infant) was linked to the recipient of the injection, and efficacy (protection starts directly after birth versus soon after administration) was linked to the timing of the injection. Therefore, although the maternal vaccine and infant mAb were assumed to have similar effectiveness, in practice, effectiveness could vary based on the timing of administration (i.e., the season and the timing after birth).

Fig. 1.

Example discrete choice experiment choice task. Option 2 selected as an example. Translated from Dutch (shown to participants) to English (purpose of publication). HCP healthcare provider, NIP National Immunisation Programme

A ‘dual-response none’ approach was used to assess participants’ trade-offs between attributes and attribute levels as well as the overall strength of participants’ preferences (i.e., likelihood of taking the selected immunisation option in reality). For each task, participants were first asked, ‘Please assume you were allowed to choose halfway through the pregnancy, which of the following options to protect your infant from this virus would you prefer? (1 of 10).’ Participants were then asked to indicate their willingness to receive the preferred immunisation option or opt out (‘I would vs would not choose this immunisation option’). The first choice (option 1 vs option 2) and the second choice (preferred option vs opt out) were combined into the same model.

Data validity was assessed using standard quality checks. Participants were excluded based on duplicate responses (taking the survey more than once), random responses (assessed via the root likelihood method), and speeding (having a < 5-min survey duration).

Statistical Analyses

In the DCE, the impacts of attribute levels on choices were estimated using a choice-based conjoint (CBC) analysis fitted with a two-level hierarchical Bayesian model. R and Stan were used to estimate the CBC model [26–28]. For the lower-level model, choices were modelled using multinomial logistic regression. For the higher-level model, the distribution of participant-specific parameters (i.e., the value each participant placed on each attribute level) was modelled according to a multivariate normal distribution with a covariance matrix. This method accounts for variability between participants and correlations between parameters.

Preference Weights

Preference weights were estimated for each attribute level and were normalised so that they summed to zero. Higher (positive) preference weights for an attribute level indicated a greater preference for that level relative to other levels within the same attribute.

Conditional Relative Attribute Importance

Conditional relative attribute importance (CRAI), the importance of each attribute compared to other attributes, was calculated using preference weights obtained from the hierarchical Bayesian model. CRAI was estimated by successively calculating the difference in preference weights for the most-preferred and least-preferred levels within an attribute in 400 sequential draws, summing these differences for all attributes, and scaling the total to 100%. An average CRAI was obtained for each attribute with a corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI). Attributes with higher CRAI scores were considered more important to participants.

Willingness to be Immunised

Simulated willingness to be immunised against a common virus among infants that represented RSV was predicted in three different scenarios. These included two hypothetical RSV prevention strategy profiles and a no-immunisation option (Table 2). One hypothetical profile represented the nirsevimab infant mAb injection, and the other hypothetical profile represented the RSVpreF maternal vaccine. For the hypothetical profile representing the infant mAb injection, ‘within 2 weeks after birth’ was the selected timing level, in line with the Health Council recommendations [29]. ‘At home or at child health clinic’ was the selected location level because the administration location has not yet been decided in the Netherlands. The other levels were ‘€0’, ‘recommended by a doctor or nurse’, ‘included in the NIP’, and ‘not co-administered with any other injections’, which were the most realistic options if the infant mAb injection was included in the NIP. For the hypothetical profile representing the maternal vaccine, ‘at child health clinic’ was the selected location level in line with the location where pregnant women receive other vaccines. Apart from the levels for timing and recipient of the injection and administration location, all other levels were the same for both hypothetical profiles. Three scenarios were evaluated: (1) only the infant mAb injection in the NIP (i.e., the present planned scenario), (2) only the maternal vaccine in the NIP, and (3) both the infant mAb injection and the maternal vaccine in the NIP. Scenario 3 was included to model shared decision making, a scenario when pregnant women make a joint decision with an HCP.

Table 2.

Hypothetical RSV prevention strategy profiles

| Hypothetical profile representing the nirsevimab infant mAb injection | Hypothetical profile representing the RSVpreF maternal vaccine | |

|---|---|---|

| Timing and recipient of the injection | To your infant within 2 weeks after birth, protected shortly after administration for approximately 6 months. Potential adverse events for the infant | To the mother during pregnancy, protected directly after birth for approximately 6 months. Potential adverse events for the mother, not for the infant |

| Costs (€) | 0 | 0 |

| Recommended by an HCP | Recommended by a doctor or nurse | Recommended by a doctor or nurse |

| Included in the NIP | Included in the NIP (you receive an invitation automatically) | Included in the NIP (you receive an invitation automatically) |

| Administration location | At home or at child health clinic | At child health clinic |

| Co-administered with other injections | Not co-administered with any other injections | Not co-administered with any other injections |

HCP healthcare provider, mAb monoclonal antibody, NIP National Immunisation Programme, RSV respiratory syncytial virus, RSVpreF respiratory syncytial virus prefusion F

The lower-level hierarchical Bayesian model was used to generate the simulation model, which examined willingness to be immunised. By summing the utilities for each attribute level of a given treatment profile for each participant, the simulation model calculated preference shares as an average across the sample.

Latent Groups

Finally, a post hoc latent class analysis was conducted to identify latent groups of participants with similar immunisation preferences and understand sample heterogeneity. Participants were grouped based on their trade-offs on timing and recipient of the injection and costs and their overall likelihood of immunisation. The CBC latent class tool within Sawtooth software was used [30]. Clustering options with two, three, or four clusters were compared. The three-cluster option was considered optimal because it demonstrated a difference in the importance of costs between latent groups. The four-cluster option was not suitable because one latent group had too few participants for a robust analysis. Personal covariates were used for descriptive analyses.

Results

Participants

The screening survey was started by 178 individuals of whom two were not eligible. Twenty-six participants did not complete the main survey. The final sample included 150 participants (n = 68 pregnant women, n = 67 mothers of infants, n = 8 male partners of pregnant women, and n = 7 fathers of infants; Table 3). On average, participants were 31.23 years of age (standard deviation = 5.61 years). Most participants were from the highest education group (higher vocational education or research-oriented higher education; n = 98, 65%) and highest income group (household annual income before tax > €45,000; n = 96, 64%). Forty-five percent of participants (n = 68) were having their first child, and 55% (n = 82) had an infant aged > 6 months. On average, pregnant participants and pregnant partners of participants were 20.84 weeks pregnant (standard deviation = 8.82 weeks).

Table 3.

Participant characteristics

| Characteristic | Result | N |

|---|---|---|

| Subsample, n (%) | 150 | |

| Pregnant woman | 68 (45) | |

| Mother of infant | 67 (45) | |

| Male partner of pregnant woman | 8 (5) | |

| Father of infant | 7 (5) | |

| Age of adult | 150 | |

| Mean age in years (SD) | 31.23 (5.61) | |

| 18–29 years, n (%) | 52 (35) | |

| 30–39 years, n (%) | 88 (59) | |

| ≥ 40 years, n (%) | 10 (7) | |

| Age of infanta | 74 | |

| Mean age in weeks (SD) | 19.12 (9.26) | |

| Having first child, n (%) | 150 | |

| Yes | 68 (45) | |

| No | 82 (55) | |

| Weeks of pregnancyb | 76 | |

| Mean weeks (SD) | 20.84 (8.82) | |

| Household annual income before tax, n (%) | 150 | |

| < €30,000 (below modal) | 12 (8) | |

| €30,000–€45,000 (modal) | 32 (21) | |

| > €45,000 (above modal) | 96 (64) | |

| Rather not say | 10 (7) | |

| Highest completed education, n (%)c | 150 | |

| Low | 5 (3) | |

| Middle | 46 (31) | |

| High | 98 (65) | |

| Rather not say | 1 (1) | |

| Religious, n (%) | 150 | |

| Yes | 67 (44) | |

| No | 79 (53) | |

| Rather not say | 4 (3) | |

| Geographical province of residence, n (%) | 150 | |

| Drenthe | 6 (4) | |

| Flevoland | 3 (2) | |

| Friesland | 6 (4) | |

| Gelderland | 18 (12) | |

| Groningen | 9 (6) | |

| Limburg | 5 (3) | |

| North Brabant | 21 (14) | |

| North Holland | 24 (16) | |

| Overijssel | 11 (7) | |

| Utrecht | 14 (9) | |

| Zeeland | 6 (4) | |

| South Holland | 27 (18) | |

| Area of residence, n (%) | 150 | |

| City | 79 (53) | |

| Village | 62 (41) | |

| Rural area | 7 (5) | |

| Rather not say | 2 (1) |

aAnswered by mothers of infants and fathers of infants. bAnswered by pregnant women and male partners of pregnant women. c‘Low’ referred to practical education, none or only primary school education, or pre-vocational secondary education. ‘Middle’ referred to senior general secondary education, pre-university education, or secondary vocational education. ‘High’ referred to higher vocational education or research-oriented higher education. SD standard deviation

Awareness of and Attitudes Towards Immunisations

In the survey, most participants (n = 141, 94%) reported being in favour of immunising their infant within 6 months (Table 4). Of these, the most noted reason that participants selected was ‘I want to protect my infant as much as possible’ (n = 102, 72%). Few participants (n = 9, 6%) reported being against immunising their infant within 6 months. Of these, the most noted reason that participants selected was ‘I’m afraid something bad will happen to my infant because of the immunisation’ (n = 3, 33%). Seventy-three percent of parents (n = 109) reported that they or their partners received or are planning to receive the recommended tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis (Tdap) vaccine at 22 weeks of gestation, whereas 19% (n = 29) reported that they or their partners received or are planning to receive the RSV maternal vaccine. A total of 144 participants reported that they were considering an immunisation option for a common virus among infants. Of these, participants reported a preference for a maternal vaccine (n = 106, 74%) for a common virus among infants, selecting it as their top-ranked option. This preference was higher compared to the infant mAb injection (n = 26, 18%). Twelve participants (8%) had no preference.

Table 4.

Participant awareness of and attitudes towards immunisations

| Questions and response options | n (%) | N |

|---|---|---|

| Child/children have had all immunisations (so far) from the NIP, n (%)a | 82 | |

| Yes | 69 (84) | |

| Some of the immunisations, but not all | 10 (12) | |

| No | 2 (2) | |

| I don’t know | 1 (1) | |

| Reasons to immunise infant within 6 monthsb | 141 | |

| I want to protect my infant as much as possible | 102 (72) | |

| I know how ill an infant can get from these diseases | 75 (53) | |

| Invitation and/or advice from the obstetrician/consultant doctor | 43 (30) | |

| I have received an invitation for the immunisation | 34 (24) | |

| Invitation and/or advice from the GP | 13 (9) | |

| Reasons to not immunise infant within 6 monthsc | 9 | |

| I’m afraid something bad will happen to my infant because of the immunisation | 3 (33) | |

| I do not know enough about these diseases and/or immunisations | 2 (22) | |

| I’m afraid my infant will suffer side effects | 2 (22) | |

| Doubts about whether the immunisation protects adequately | 2 (22) | |

| I don’t see the need for immunisation | 2 (22) | |

| Vaccine women received or are planning to receive during pregnancy (self-stated) | 150 | |

| Tdap at 22 weeks of gestation | 109 (73) | |

| Influenza | 42 (28) | |

| COVID-19 | 36 (24) | |

| RSV | 29 (19) | |

| None of the above | 11 (7) | |

| Don’t know (yet) | 14 (9) | |

| Reasons to get vaccinated with the Tdap at 22 weeksd | 109 | |

| I'd rather take the vaccine myself than have my infant get it | 69 (63) | |

| Invitation and/or advice from the midwife or consulting agency | 46 (42) | |

| I am afraid my infant may become seriously ill | 41 (38) | |

| I have received an invitation for the vaccination | 29 (27) | |

| Invitation and/or advice from the gynaecologist | 20 (18) | |

| Reasons to not get vaccinated with the Tdap at 22 weekse | 41 | |

| I do not know enough about these diseases and/or the vaccination | 14 (34) | |

| Doubts about whether vaccine protects adequately | 11 (27) | |

| I'm afraid my infant will suffer side effects | 10 (24) | |

| I don't see the need for vaccination | 9 (22) | |

| I am afraid that myself / my partner will get side effects from the vaccination | 5 (12) | |

| What means of protection would you consider if it is in the NIPf | 150 | |

| Maternal vaccine | 118 (79) | |

| Infant mAb injection (3 months) | 84 (56) | |

| Infant mAb injection (1 month) | 58 (39) | |

| Infant mAb injection (2 weeks) | 37 (25) | |

| Infant mAb injection (24h) | 36 (24) | |

| None | 6 (4) | |

| What means of protection would you prefer if it is in the NIP (ranked top)f, g | 144 | |

| Maternal vaccine injection | 106 (74) | |

| Infant mAb injection (3 months) | 15 (10) | |

| Infant mAb injection (1 month) | 1 (1) | |

| Infant mAb injection (2 weeks) | 0 (0) | |

| Infant mAb injection (24h) | 10 (7) | |

| None | 12 (8) | |

| Key considerations impacting decision to get vaccinated/immunise infanth | 127 | |

| To protect my infant against the consequences of an infection | 70 (55) | |

| Included in NIP / advised by HCP | 28 (22) | |

| Because it is free | 14 (11) | |

| Only if I (mother) can take it | 14 (11) | |

| Immunisation needs to be safe | 9 (7) | |

| Immunisation is important | 9 (7) | |

| Reasons to not get vaccinated/immunise infanti | 109 | |

| I’m afraid my infant will experience side effects | 45 (41) | |

| It is too expensive/not reimbursed | 43 (39) | |

| I don’t know enough about the virus / immunisation | 39 (36) | |

| My infant is too young | 33 (30) | |

| I’m afraid something will happen to my infant due to the immunisation | 27 (25) |

aAnswered by mothers and fathers of infants who were > 6 months old. bAnswered by participants who reported they have already or were planning to let their infant have at least one of the available immunisations from the NIP. Participants could select up to five reasons. cAnswered by participants who reported they have already or were planning to let their infant have none of the available immunisations from the NIP. Participants could select up to five reasons. dAnswered by participants who reported that they received or were planning to receive or their partner received or was planning to receive the 22-week vaccine during pregnancy. Participants could select up to five reasons. eAnswered by participants who reported that they did not receive or plan to receive or their partner did not receive or plan to receive the 22-week vaccine during pregnancy. Participants could select up to five reasons. fQuestion framed in the context of a common virus among infants. gAnswered by participants who reported that they were considering an immunisation option for a common virus among infants. hAnswered by participants who reported that in some or all cases, they would consider protecting their infant from this common virus with an immunisation. i Answered by participants who selected to not immunise at least once in the DCE. Participants could select up to five reasons. COVID-19 coronavirus disease 2019, DCE discrete choice experiment, GP general practitioner, HCP healthcare provider, mAb monoclonal antibody, NIP National Immunisation Programme, RSV respiratory syncytial virus, Tdap tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis

DCE

Preference Weights

Preference weights indicated that participants preferred an immunisation option that is administered to pregnant women (mean = 1.48 [95% CI, 1.18–1.82]), free of charge (mean = 1.36 [95% CI, 1.10–1.67]), recommended by an HCP (mean = 0.50 [95% CI, 0.34–0.66]), and included in the NIP (mean = 0.42 [95% CI, 0.26–0.58]; Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Preference weights per attribute level. CI confidence interval, GP general practitioner, HCP healthcare provider, NIP National Immunisation Programme

CRAI

Overall, the most important attribute to participants was timing and recipient of the injection (CRAI = 32% [95% CI, 28–35%]; Fig. 3). The second most important attribute was costs (CRAI = 24% [95% CI, 20–28%]). Recommended by an HCP (CRAI = 13% [95% CI, 11–16%]), included in the NIP (CRAI = 13% [95% CI, 10–15%]), and administration location (CRAI = 12% [95% CI, 9–15%]) were considered similarly important to participants. Co-administered with other injections was the least important attribute (CRAI = 7% [95% CI, 5–9%]).

Fig. 3.

Conditional relative attribute importance. CI confidence interval, HCP healthcare provider, NIP National Immunisation Programme

Willingness to be Immunised

On average, willingness to be immunised was highest when both the hypothetical infant mAb injection profile and the hypothetical maternal vaccine profile were available in the NIP (scenario 3: 89%; Fig. 4). Willingness to be immunised was 15% higher when both hypothetical RSV prevention strategy profiles were available in the NIP than when only the hypothetical infant mAb injection profile was available (scenario 3: 89% vs scenario 1: 74%). Willingness to be immunised was 12% higher when only the hypothetical maternal vaccine profile was available in the NIP than when only the hypothetical infant mAb injection profile was available in the NIP (scenario 2: 86% vs scenario 1: 74%). When both hypothetical RSV prevention strategy profiles were available in the NIP (scenario 3), more participants chose the hypothetical profile representing the maternal vaccine (n = 113, 75%) than the hypothetical profile representing the infant mAb injection (n = 21, 14%) or no immunisation (n = 16, 11%).

Fig. 4.

Predicted willingness to be immunised in three different scenarios involving two hypothetical RSV prevention strategy profiles. HCP healthcare provider, mAb monoclonal antibody, NIP National Immunisation Programme, RSV respiratory syncytial virus

Latent Groups

Some sample heterogeneity based on participants’ preferences was identified in the latent class analysis. Twenty-three percent (n = 35) of participants were clustered in latent group 1 (Supplementary Table S1), for whom costs were an important driver of preferences. Fourteen percent (n = 21) of participants were clustered in latent group 2. For this group, overall likelihood of immunisation was low, and they were more likely to prefer maternal vaccination or no immunisation. Sixty-three percent (n = 94) of participants were clustered in latent group 3. For this group, overall likelihood of immunisation was very high, and they were more likely to prefer maternal vaccination or infant immunisation when the infant is > 1 month of age.

Discussion

This study, conducted in the Netherlands, found that Dutch parents preferred a maternal vaccine over an infant mAb injection to immunise their infants against a common virus that represented RSV. They preferred a strategy that is administered to pregnant women, free of charge, recommended by an HCP, and included in the NIP. Of the DCE attributes tested, timing and recipient of the injection and costs were most important to parents and had the greatest impact on the choice of immunisation option. On average, predicted willingness to be immunised was highest in a hypothetical scenario when both the infant mAb injection and the maternal vaccine were available in the NIP. The preferences of approximately two-thirds (63%) of parents were mostly driven by infant protection and the preferences of approximately one-quarter (23%) of parents were mostly driven by costs. For the remainder of parents (14%), overall likelihood of immunisation was low.

Consistent with the current study, a cross-sectional survey in the Netherlands (n = 1001) found that approximately seven in ten pregnant women and their partners preferred an RSV maternal vaccine to an RSV infant mAb injection [15]. A cross-sectional survey in Canada (n = 803) also found that approximately seven in ten pregnant women preferred an RSV maternal vaccine to an RSV infant mAb injection [31]. A cross-sectional survey in the UK (n = 1620) found that approximately nine in ten parents of children < 2 years of age or pregnant women preferred an RSV maternal vaccine to an RSV infant mAb injection [32]. Another cross-sectional UK survey of pregnant women and mothers of infants < 6 months of age (n = 1061) found high acceptability of the RSV maternal vaccine (approximately 90%) and the RSV infant mAb injection (approximately 80%), with some preference for the RSV maternal vaccine [33]. Furthermore, another cross-sectional survey in Canada (n = 723) similarly found that approximately eight in ten pregnant women preferred an RSV maternal vaccine to an RSV infant mAb injection [34]. In addition, two DCEs conducted in the US also found that pregnant women preferred an RSV maternal vaccine to an RSV infant mAb injection [16, 17]. Conversely, a European study found that parental acceptance of the RSV infant mAb injection was higher (75%) than the RSV maternal vaccine (63%) [35]. However, this study did not directly compare preferences for both methods of immunisation, and these results should be interpreted with caution as the study report did not undergo peer review before publication.

Findings from the current study may help to inform upcoming prevention strategies for RSV in the Netherlands and other countries. In February 2024, the Health Council of the Netherlands recommended offering protection against RSV to all children under the age of 1 year through the Dutch NIP [29]. The Health Council considered both the infant mAb injection and maternal vaccine to offer good protection and favourable benefit-risk profiles [29]. As of February 14, 2024, the Health Council favours the infant mAb injection, which is expected to be included in the NIP in autumn/winter 2025 [14]. However, whether parents and HCPs accept the infant mAb injection at a very young age (within 2 weeks after birth) is currently unknown [29]. No preference data were available when the Health Council’s recommendation was published on 14 February 2024.

Evidence from this study and other studies [15–17, 32] suggests that parents prefer the maternal vaccine over the infant mAb injection. Furthermore, findings from this study indicated that willingness to be immunised was 15% higher in a scenario when both the maternal vaccine and infant mAb injection were available than when only the infant mAb injection was available in the NIP. When both options were available in the NIP, 75% of parents chose the maternal vaccine, 14% chose the infant mAb injection, and 11% chose no immunisation. Therefore, future adherence to an NIP is likely to be higher if both immunisation options are available. An NIP that includes both strategies may increase percentage uptake, protect more infants, and achieve greater public health impact than an NIP that only includes the infant mAb injection. This is supported by real-world evidence from Luxembourg, where an infant mAb injection-only strategy was implemented, followed by the addition of the RSV maternal vaccine a year later. Uptake increased from 81% for the infant mAb injection-only strategy to 93% for the complementary strategy [36, 37]. A recent cost-effectiveness analysis also indicated that a complementary strategy is more cost-effective than the infant mAb injection alone [38].

This study has several strengths. For example, the preferences of males and females and parents and expectant parents were considered. In addition, best-practice guides were followed. Another strength is that the study quantified preferences of Dutch parents for RSV prevention strategies using a DCE, which is a more effective way of measuring preferences than surveys. However, preferences exhibited in DCEs may differ from real-life preferences, a limitation of DCEs known as hypothetical bias [39]. Despite this, real-world data on actual uptake appear to be somewhat consistent with data from preference surveys. For example, monthly coverage data in England for the fifth month of the RSV maternal vaccination programme (January 2025) showed good acceptability of the RSV maternal vaccine with coverage increasing with programme continuity, growing awareness, and earlier notification of pregnant women [40]. Of the 37,145 women reported as having given birth in January 2025, 19,715 (53.1%) had received an RSV vaccine, and this proportion was as high as 62.7% in some regions and 75.1% in some ethnic groups [40]. This was somewhat consistent with a UK preference study conducted in 2023, which reported acceptance of the maternal vaccine against RSV by 88% of pregnant women and parents of children aged < 2 years who were surveyed [32]. However, the discrepancy between actual acceptance/uptake in the real world and reported acceptance/uptake in surveys is a general limitation of the existing literature. Further research is needed to understand the reasons for this discrepancy.

Real-world data on the percentage uptake of RSV prevention strategies varies between countries and depends on the implementation strategies used. For example, in Galicia Spain, uptake of the RSV infant mAb injection was > 90% [41, 42]. Substantial efforts were made to increase the percentage uptake via an education campaign and a hospital-based roll-out [41]. In countries with traditional implementation as part of an NIP, lower percentage uptake rates have been reported. For example, uptake of the RSV infant mAb injection was 12% in its first season in France [43], and uptake of the RSV infant mAb injection and the RSV maternal vaccine was < 20% in Wisconsin, US [44]. However, practical challenges may also explain the variability in implementation across countries. For example, France experienced shortages of the infant mAb injection during their national campaign [43], which may also partly explain the lower uptake. Furthermore, recent data from Luxembourg and the US show that while some newborns received the infant mAb injection, a substantial proportion of newborns did not [36, 37, 45]. These findings highlight the practical challenges of achieving complete and timely coverage with the infant mAb injection, even in healthcare systems where birth predominantly occurs in hospital settings.

In the Netherlands, uptake of the Tdap maternal vaccine is approximately 70% [46]. The percentage uptake of the RSV maternal vaccine is expected to be similar. In the Netherlands, the Tdap maternal vaccine is recommended from 22 weeks of gestation onwards. The RSV maternal vaccine can be co-administered with other maternal vaccines (e.g., influenza, COVID-19). Therefore, administration during the winter season would not require an additional visit. In Europe, a 2-week interval between the RSV and Tdap maternal vaccines is recommended, while in the US and Australia, co-administration with Tdap is acceptable. In the US and Australia, the RSV maternal vaccine can be co-administered with other vaccines [47, 48]. In the Netherlands, it has not yet been decided who would be responsible for administering the RSV maternal vaccine if it is included in the NIP. Currently, Youth Health Care physicians and nurses administer the Tdap and influenza maternal vaccines to pregnant women, whereas general practitioners administer the influenza maternal vaccine to pregnant women with underlying medical conditions.

Predicted uptake of the RSV infant mAb injection in the Netherlands is more uncertain because of the unusually early timing of administration. Infants are expected to receive the RSV mAb injection within 2 weeks after birth, whereas currently, infants receive their first injection within 3 months after birth. Due to the higher proportion of home births (vs hospital births) in the Netherlands compared to other European countries, it was decided not to administer the RSV mAb injection immediately after birth in the hospital. The RSV mAb invitation letter for the primary group (infants born during the RSV season) is planned to be delivered to parents approximately 11–14 days after the infant’s birth [49]. If needed, a verbal reminder will be given by a Youth Health Care physician after 4 weeks during an existing appointment. Youth Health Care nurses and physicians will either visit families at home to administer the RSV infant mAb injection or parents will be asked to come to the baby clinic. The catch-up group will receive the immunisation at the baby clinic. Therefore, percentage uptake may be negatively affected by logistical barriers. Parental acceptance of neonatal injectables may also affect uptake. For example, in the Netherlands, a proposal to replace oral vitamin K drops with injectable vitamin K was met with resistance by midwives and parents, leading to a reversal of the decision and a decrease in vitamin K uptake. This example highlights the challenges of achieving high uptake of new neonatal injectables.

The study had some limitations. With 150 participants, the study was relatively small for a DCE, which may have impacted the precision of the results. However, the error margins were deemed acceptable and showed clear conclusions for most model parameters. The sample included a higher proportion of parents with a high level of education (65%) compared to the general population in the Netherlands (54%) [50]. Most of the samples were from high-income households. These sociodemographic differences may affect the generalisability of findings to the wider population as level of education can influence attitudes towards vaccines and vaccine acceptance [51–53]. However, the direction of influence is unclear; some studies suggest that higher level of education is associated with higher vaccine acceptance and lower vaccine hesitancy [51, 53], whereas others have found the opposite [52].

Choice tasks were framed in the context of immunisation against a general common virus among infants rather than against RSV, specifically. In the real world, parents’ immunisation choices may be affected by the virus that the immunisation strategy protects against. For example, in the survey, 73% of parents reported that they or their partners received or are planning to receive the recommended Tdap vaccine at 22 weeks of gestation, whereas 19% reported that they or their partners received or are planning to receive the RSV vaccine. However, context (e.g., costs) was not provided for participants during the survey. Current parental awareness of RSV is poor [54]; improving awareness of RSV and RSV prevention strategies is needed to influence uptake.

The DCE design did not account for all attributes and scenarios that may influence parental preferences. Additional clinically relevant differences exist between the two RSV prevention strategies. For example, preterm infants who are born before or shortly after maternal vaccination will be unprotected [55]. Maternal vaccination may be suboptimal for infants born outside of the RSV season, as they may no longer be protected when the RSV season begins [56]. In addition, studies of antibody levels suggest that maternal vaccination provides protection to the infant that wanes in the months following birth, whereas the infant mAb injection may provide more stable protection during the RSV season [4, 57]. Timing and recipient of the injection was an attribute in the DCE design. However, both RSV prevention strategies face challenges in terms of timely administration to achieve optimal protection. The maternal vaccine must be administered at the correct stage of pregnancy (between weeks 24 and 36 of gestation), and the infant mAb injection must be administered within 14 days after birth. In addition, the infant mAb injection has an effectiveness lag of at least 7 days after administration [58]. The timing of immunisation was therefore not fully accounted for in the survey. Clinical differences between the RSV prevention strategies related to seasonality and prematurity, and thus infant protection, could influence parental preferences in the real world.

The findings of the current study suggest that parents prefer a maternal vaccine to an infant mAb injection. However, given that the clinical attributes were not exhaustively or explicitly presented to parents in the context of RSV prevention, it is possible that results are not completely transferrable.

Finally, the preference weights and CRAI derived from this DCE are inherently sensitive to the attributes and levels selected. The inclusion or exclusion of attributes may have shaped participants’ focus, potentially over- or underestimating the importance of certain features. Similarly, the range and framing of attribute levels can influence perceived differences between options. For example, wider level ranges may inflate an attribute’s relative importance, while narrow or unrealistic levels may diminish it. Since CRAI is a relative measure, these design choices directly impact the results. In the current research, the cost range tested yielded a high CRAI score. If a narrower cost range had been tested, the resulting CRAI of this attribute would probably have been lower.

Conclusions

In conclusion, most parents in the Netherlands preferred a maternal vaccine to an infant mAb injection to immunise their infants against a common virus that represented RSV. In addition, overall willingness to be immunised was higher in a hypothetical scenario when both RSV prevention strategies were available in the NIP than in a hypothetical scenario when only the infant mAb injection was available. This evidence may help to inform policymakers in different countries when planning RSV NIPs. The complementary strategy that includes both the maternal vaccine and the infant mAb injection may protect the most infants against RSV. However, as the clinical attributes were not exhaustively or explicitly presented to parents in the context of RSV prevention, the results may not be completely transferable.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

Medical Writing, Editorial, and Other Assistance

Medical writing was provided by Maddy Dyer, PhD, at PPD clinical research business of Thermo Fisher Scientific and was funded by Pfizer. The authors thank Nicolas Krucien, PhD, (Evidera, PPD clinical research business of Thermo Fisher Scientific) for his methodological and statistical insights, which helped to inform the first draft of the manuscript. The authors also thank Sharka Dijkema, MSc, and Milan Raamstijn, MSc, for their contributions to the study design and data collection, analysis, and reporting. The authors thank the study participants for their participation in this study.

Author Contributions

Annefleur C. Langedijk: Conceptualisation, Methodology, Writing – Review & Editing, Supervision, Project Administration; Floris van den Dungen: Methodology, Writing—Review & Editing; Lisette Harteveld: Writing—Review & Editing; Lisanne van Leeuwen: Writing—Review & Editing; Lucy Smit: Writing—Review & Editing; Jennie van den Boer: Writing—Review & Editing; Diana Mendes: Conceptualisation, Methodology, Writing—Review & Editing; M. Claire Verhage: Formal Analysis, Investigation, Resources, Data Curation, Writing—Review & Editing, Visualisation; Elise Kocks: Software, Validation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Resources, Data Curation, Writing—Review & Editing, Visualisation; Marlies van Houten: Conceptualisation, Writing—Review & Editing.

Funding

The study was sponsored by Pfizer and was conducted by SKIM. The authors who were employed by Pfizer and SKIM contributed to study design, data analysis and interpretation, manuscript review, and the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. The journal’s Rapid Service fee was funded by ICON Clinical Research LLC.

Data Availability

The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are not publicly available because study participants did not give written consent for their data to be shared publicly.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

Annefleur C. Langedijk, Floris van den Dungen, and Diana Mendes are employees of Pfizer and may hold Pfizer stocks. M. Claire Verhage and Elise Kocks are employees of SKIM, an independent market research company that received financial support from Pfizer to conduct this research. Marlies van Houten reported the following disclosures: investigator-initiated studies with Pfizer, Sanofi, Moderna, and GSK, participation with Pfizer (MATISSE Study), and consultancy with Pfizer, MSD, Sanofi, Moderna, and GSK. Lisette Harteveld, Lisanne van Leeuwen, Lucy Smit, and Jennie van den Boer declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethical Approval

The study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the European Pharmaceutical Market Research Association and the Dutch Market Research Association. Ethical approval for this study was not required, in accordance with the Dutch Medical Research Involving Human Subjects Act. Participants provided informed consent to participate in the study (electronic checkbox consent).

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Heemskerk S, van Heuvel L, Asey T, Bangert M, Kramer R, Paget J, van Summeren J. Disease burden of RSV infections and bronchiolitis in young children (< 5 years) in primary care and emergency departments: A systematic literature review. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2024;18(8): e13344. 10.1111/irv.13344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li Y, Wang X, Blau DM, Caballero MT, Feikin DR, Gill CJ, et al. Global, regional, and national disease burden estimates of acute lower respiratory infections due to respiratory syncytial virus in children younger than 5 years in 2019: a systematic analysis. Lancet. 2022;399(10340):2047–64. 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00478-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Health Service: Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV). https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/respiratory-syncytial-virus-rsv/ (2024). Accessed 29 Oct 2024.

- 4.Verwey C, Madhi SA. Review and update of active and passive immunization against respiratory syncytial virus. BioDrugs. 2023;37(3):295–309. 10.1007/s40259-023-00596-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control: Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV). https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/respiratory-syncytial-virus-rsv (2024). Accessed 29 Oct 2024.

- 6.Wildenbeest JG, Billard MN, Zuurbier RP, Korsten K, Langedijk AC, van de Ven PM, et al. The burden of respiratory syncytial virus in healthy term-born infants in Europe: a prospective birth cohort study. Lancet Respir Med. 2023;11(4):341–53. 10.1016/S2213-2600(22)00414-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.European Medicines Agency. Beyfortus (nirsevimab): An overview of Beyfortus and why it is authorised in the EU. 2024.

- 8.Hammitt LL, Dagan R, Yuan Y, Baca Cots M, Bosheva M, Madhi SA, et al. Nirsevimab for prevention of RSV in healthy late-preterm and term infants. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(9):837–46. 10.1056/NEJMoa2110275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.European Medicines Agency. Abrysvo (respiratory syncytial virus vaccine (bivalent, recombinant)): An overview of Abrysvo and why it is authorised in the EU. 2023.

- 10.Simoes EAF, Pahud BA, Madhi SA, Kampmann B, Shittu E, Radley D, et al. Efficacy, Safety, and Immunogenicity of the MATISSE (Maternal Immunization Study for Safety and Efficacy) maternal respiratory syncytial virus prefusion F protein vaccine trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2025;145(2):157–67. 10.1097/AOG.0000000000005816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kampmann B, Madhi SA, Munjal I, Simoes EAF, Pahud BA, Llapur C, et al. Bivalent prefusion F vaccine in pregnancy to prevent RSV illness in infants. N Engl J Med. 2023;388(16):1451–64. 10.1056/NEJMoa2216480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Treston B, Geoghegan S. Exploring parental perspectives: maternal RSV vaccination versus infant RSV monoclonal antibody. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2024;20(1): 2341505. 10.1080/21645515.2024.2341505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.National Institute for Public Health and the Environment: Vaccination against RSV during pregnancy. https://www.rivm.nl/en/rsv/rsv-vaccination-during-pregnancy (2025). Accessed 06 Feb 2025.

- 14.National Institute for Public Health and the Environment: RSV antibody injection for babies. https://www.rivm.nl/en/rsv/rsv-antibody-injection-for-babies (2025). Accessed 06 Feb 2025.

- 15.Harteveld LM, van Leeuwen LM, Euser SM, Smit LJ, Vollebregt KC, Bogaert D, van Houten MA. Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) prevention: perception and willingness of expectant parents in the Netherlands. Vaccine. 2025;44: 126541. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2024.126541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maculaitis MC, Hauber B, Beusterien KM, Will O, Kopenhafer L, Law AW, et al. A latent class analysis of factors influencing preferences for infant respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) preventives among pregnant people in the United States. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2024;20(1): 2358566. 10.1080/21645515.2024.2358566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beusterien KM, Law AW, Maculaitis MC, Will O, Kopenhafer L, Olsen P, et al. Healthcare providers’ and pregnant people’s preferences for a preventive to protect infants from serious illness due to respiratory syncytial virus. Vaccines. 2024;12(5): 560. 10.3390/vaccines12050560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schley K, Whichello C, Hauber B, Krucien N, Cappelleri JC, Peyrani P, et al. Preferences of US adolescents and parents for vaccination against invasive meningococcal disease. Vaccine. 2024;42(25): 126264. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2024.126264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Centrale Commissie Mensgebonden Onderzoek: CCMO note Behavioural science research and the WMO: some conclusions. https://www.ccmo.nl/onderzoekers/publicaties/publicaties/2001/12/01/ccmo-notitie-gedragswetenschappelijk-onderzoek-en-de-wmo-enkele-conclusies (2001). Accessed 12 Nov 2024.

- 20.Orhierhor M, Rubincam C, Greyson D, Bettinger JA. New mothers’ key questions about child vaccinations from pregnancy through toddlerhood: evidence from a qualitative longitudinal study in Victoria, British, Columbia. SSM—Qualitative Res Health. 2023. 10.1016/j.ssmqr.2023.100229. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cooper S, Schmidt BM, Sambala EZ, Swartz A, Colvin CJ, Leon N, Wiysonge CS. Factors that influence parents’ and informal caregivers’ views and practices regarding routine childhood vaccination: a qualitative evidence synthesis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021;10(10): CD013265. 10.1002/14651858.CD013265.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johnson FR, Lancsar E, Marshall D, Kilambi V, Muhlbacher A, Regier DA, et al. Constructing experimental designs for discrete-choice experiments: report of the ISPOR conjoint analysis experimental design good research practices task force. Value Health. 2013;16(1):3–13. 10.1016/j.jval.2012.08.2223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.The PREFER consortium. PREFER Recommendations—Why, when and how to assess and use patient preferences in medical product decision-making. 2022.

- 24.Campoamor NB, Guerrini CJ, Brooks WB, Bridges JFP, Crossnohere NL. Pretesting discrete-choice experiments: a guide for researchers. Patient. 2024;17(2):109–20. 10.1007/s40271-024-00672-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sawtooth Software: CBC Tutorial and Example. https://sawtoothsoftware.com/help/lighthouse-studio/manual/cbc-tutorial.html (2025). Accessed 17 Jan 2025.

- 26.Carpenter B, Gelman A, Hoffman MD, Lee D, Goodrich B, Betancourt M, et al. Stan: A probabilistic programming language. J Stat Softw. 2017;76. 10.18637/jss.v076.i01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.R Core Team: The R Project for Statistical Computing. https://www.r-project.org/ (2024). Accessed.

- 28.Stan Development Team: Stan Reference Manual. https://mc-stan.org/docs/2_32/reference-manual/index.html (2023). Accessed 25 Nov 2024.

- 29.Health Council of the Netherlands: Immunisation against RSV in the first year of life. https://www.healthcouncil.nl/documents/advisory-reports/2024/02/14/immunisation-against-rsv-in-the-first-year-of-life (2024). Accessed 07 Nov 2024 2024.

- 30.Sawtooth Software: Choice-Based Conjoint (CBC) Analysis. https://sawtoothsoftware.com/conjoint-analysis/cbc (2024). Accessed 25 Nov 2024.

- 31.Gagnon D, Gubany C, Ouakki M, Malo B, Paquette M, Brousseau N, et al. Factors influencing acceptance of RSV immunization for newborns among pregnant individuals: a mixed-methods study. Vaccine. 2025;55: 127062. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2025.127062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Paulson S, Munro APS, Cathie K, Bedford H, Jones CE. Protecting against respiratory syncytial virus: an online questionnaire study exploring UK parents’ acceptability of vaccination in pregnancy or monoclonal antibody administration for infants. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2025;44(2S):S158–61. 10.1097/INF.0000000000004632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Broad J, Letley L, Adair G, Walker J, Benzaken T, Saliba V, et al. An England-wide survey on attitudes towards antenatal and infant immunisation against respiratory syncytial virus amongst pregnant and post-partum women. Vaccine. 2025;62: 127482. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2025.127482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McClymont E, Wong JMH, Forward L, Blitz S, Barrett J, Bogler T, et al. Acceptance and preference between respiratory syncytial virus vaccination during pregnancy and infant monoclonal antibody among pregnant and postpartum persons in Canada. Vaccine. 2025;50: 126818. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2025.126818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Keij S, Noorland S, Bos N: Perceptions regarding RSV and RSV immunization among (prospective) parents and older adults. https://www.nivel.nl/nl/publicatie/perceptions-regarding-rsv-and-rsv-immunization-among-prospective-parents-and-older (2024). Accessed 06 Feb 2025.

- 36.Dookhun D, Ernst C, Del Lero N, Ketchiozo G, Vergison A, Mossong J, De La Fuente Garcia I. Impact of a mixed strategy of monoclonal antibody and maternal immunisation on pediatric RSV hospitalisations in Luxembourg, 2022–2025. ESPID2025.

- 37.Ernst C, Dookhun D, Del Lero N, Ketchiozo G, Vaccaroli R, Vergison A, et al. Effectiveness of a mixed maternal and passive infant immunisation strategy to prevent RSV-related paediatric hospitalisations in Luxembourg. ESCMID2025.

- 38.Langedijk AC, van den Dungen F, Harteveld L, van den Boer J, Smit L, Averin A, et al. Cost-effectiveness of immunization strategies to protect infants against respiratory syncytial virus in the Netherlands. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2025. 10.1080/21645515.2025.2521912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Quaife M, Terris-Prestholt F, Di Tanna GL, Vickerman P. How well do discrete choice experiments predict health choices? A systematic review and meta-analysis of external validity. Eur J Health Econ. 2018;19(8):1053–66. 10.1007/s10198-018-0954-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.GOV.UK: RSV maternal vaccination coverage in England: January 2025. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/rsv-immunisation-for-older-adults-and-pregnant-women-vaccine-coverage-in-england/rsv-maternal-vaccination-coverage-in-england-january-2025 (2025). Accessed 11 June 2025.

- 41.Martinon-Torres F, Miras-Carballal S, Duran-Parrondo C. Early lessons from the implementation of universal respiratory syncytial virus prophylaxis in infants with long-acting monoclonal antibodies, Galicia, Spain, September and October 2023. Euro Surveill. 2023. 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2023.28.49.2300606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Morris T, Acevedo K, Alvarez Aldeán J, Fiscus M, Hackell J, Pérez Martín J, et al. Lessons from implementing a long-acting monoclonal antibody (nirsevimab) for RSV in France, Spain and the US. Discov Health Systems 2025;4(21).

- 43.Jabagi MJ, Cohen J, Bertrand M, Chalumeau M, Zureik M. Nirsevimab effectiveness at preventing RSV-related hospitalization in infants. N Engl J Med Evid. 2025;4(3): EVIDoa2400275. 10.1056/EVIDoa2400275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kemp M, Capriola A, Schauer S. RSV immunization uptake among infants and pregnant persons - Wisconsin, October 1, 2023-March 31, 2024. Vaccine. 2025;47: 126674. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2024.126674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Implementation and uptake of nirsevimab and maternal vaccine for infant protection from RSV. In: Immunization Services Division NCfIaRD, editor.2025.

- 46.van Lier EA, Hament JM, Knijff M, Westra M, Ernst A, Giesbers H, et al.: Vaccination coverage and annual report National Immunisation Programme Netherlands 2022. https://rivm.openrepository.com/entities/publication/e8510742-ef1d-4d4e-99ad-808828ddd032 (2023). Accessed 18 June 2025.

- 47.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: RSV Vaccine Guidance for Pregnant Women. https://www.cdc.gov/rsv/hcp/vaccine-clinical-guidance/pregnant-people.html (2024). Accessed 22 July 2025.

- 48.Department of Health and Aged Care: Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV). https://immunisationhandbook.health.gov.au/contents/vaccine-preventable-diseases/respiratory-syncytial-virus-rsv#vaccines-dosage-and-administration (2025). Accessed 22 July 2025.

- 49.Institute for Public Health and The Environment. Introduction Webinar RSV Immunisation. 2025.

- 50.StatLine: The Netherlands in figures. https://opendata.cbs.nl/statline/#/CBS/nl/ (2025). Accessed 23 Jan 2025.

- 51.Lindholt MF, Jorgensen F, Bor A, Petersen MB. Public acceptance of COVID-19 vaccines: cross-national evidence on levels and individual-level predictors using observational data. BMJ Open. 2021;11(6): e048172. 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-048172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tang S, Liu X, Jia Y, Chen H, Zheng P, Fu H, Xiao Q. Education level modifies parental hesitancy about COVID-19 vaccinations for their children. Vaccine. 2023;41(2):496–503. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2022.11.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cagnotta C, Lettera N, Cardillo M, Pirozzi D, Catalan-Matamoros D, Capuano A, Scavone C. Parental vaccine hesitancy: recent evidences support the need to implement targeted communication strategies. J Infect Public Health. 2025;18(2): 102648. 10.1016/j.jiph.2024.102648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lee Mortensen G, Harrod-Lui K. Parental knowledge about respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) and attitudes to infant immunization with monoclonal antibodies. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2022;21(10):1523–31. 10.1080/14760584.2022.2108799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Charlesworth JEG. Mind the (preterm) gap: inequality in the UK’s current RSV immunisation approach will leave many preterm babies unprotected against RSV this winter. Arch Dis Child. 2024. 10.1136/archdischild-2024-327741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Plock N, Sachs JR, Zang X, Lommerse J, Vora KA, Lee AW, et al. Efficacy of monoclonal antibodies and maternal vaccination for prophylaxis of respiratory syncytial virus disease. Commun Med. 2025;5(1): 119. 10.1038/s43856-025-00807-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fleming-Dutra KE, Jones JM, Roper LE, Prill MM, Ortega-Sanchez IR, Moulia DL, et al. Use of the Pfizer respiratory syncytial virus vaccine during pregnancy for the prevention of respiratory syncytial virus-associated lower respiratory tract disease in infants: recommendations of the advisory committee on immunization practices - United States, 2023. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023;72(41):1115–22. 10.15585/mmwr.mm7241e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Moline HL, Tannis A, Toepfer AP, Williams JV, Boom JA, Englund JA, et al. Early estimate of nirsevimab effectiveness for prevention of respiratory syncytial virus-associated hospitalization among infants entering their first respiratory syncytial virus season - New Vaccine Surveillance Network, October 2023-February 2024. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2024;73(9):209–14. 10.15585/mmwr.mm7309a4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are not publicly available because study participants did not give written consent for their data to be shared publicly.