Abstract

Evidence remains inconsistent regarding the relationship between dairy products consumption and endometrial cancer (EC) risk. This study aimed to investigate the association between dairy products intake and EC risk in Iranian women. In this hospital-based case-control study, 136 patients with histologically confirmed EC and 272 age- and BMI-matched controls were included. Dietary intake was assessed by a validated 168-item food frequency questionnaire. Conditional logistic regression models were applied to estimate odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for EC risk across tertiles of energy-adjusted dairy consumption, adjusting for relevant dietary, reproductive, and lifestyle confounders. Higher intake of total dairy, low-fat dairy, and high-fat dairy was significantly associated with a lower risk of EC in fully adjusted models. The strongest inverse associations were observed at moderate intake levels. No significant association was found between butter consumption and EC risk. Sensitivity analyses among postmenopausal women confirmed consistent inverse associations for total and subtypes of dairy products. Our study indicated that higher dairy product consumption is associated with a reduced risk of EC. These findings suggest a potential protective role of dairy in EC prevention. Additional research, particularly in larger and more diverse populations, is needed to explore this further.

Keywords: Endometrial cancer, Dairy products, Case-Control

Subject terms: Cancer prevention, Nutrition

Introduction

Endometrial cancer (EC) is one of the most prevalent gynecologic malignancies, ranking as the sixth most common cancer among women worldwide, with a notable increase in incidence observed in both developed and developing regions1. According to the Global Cancer Observatory (GLOBOCAN) 2022 data, endometrial cancer accounted for approximately half a million new cases and 97,700 deaths globally, making it a significant public health concern1. While several risk factors, such as excess adiposity, metabolic disorders, hormonal imbalances, early menarche, nulliparity, late menopause, and hormone replacement therapy (HRT), have been extensively studied, the role of diet remains a topic of ongoing research2. According to the literature, it should be noted that dietary factors are estimated to contribute to 30–35% of overall cancer risk, underscoring the importance of investigating dietary components that may influence EC development3–5. Regarding EC, The World Cancer Research Fund and the American Institute for Cancer Research recommend that diet be considered a modifiable risk factor associated with the risk of developing this type of cancer6.

In recent years, dairy products, which are widely consumed as part of a balanced diet, have received particular attention due to their complex nutritional profile, which includes essential nutrients, bioactive compounds, and varying levels of saturated fatty acids (SFAs) that may influence carcinogenesis differently7–9. Dairy products are a rich source of calcium and conjugated linoleic acid (CLA), which have been significantly associated with a reduced risk of endometrial cancer10,11. Current evidence on prospective associations between dairy product intake and EC risk is limited and inconsistent. In this regard, some research indicate that dairy products may contain hormones potentially harmful to reproductive health and associated with cancer development12,13. Furthermore, consistent consumption of dairy may heighten the risk of cancer by elevating levels of insulin-like growth factor14. Whereas, the World Cancer Research Fund and the American Institute for Cancer Research states in their latest report that there is currently no conclusive evidence regarding the relationship between total dairy product consumption and the risk of EC6.Accordingly, a 2017 systematic review and meta-analysis of 18 observational studies found no significant association between total dairy intake and EC risk. However, findings from high-quality perspective studies suggested that greater overall dairy consumption, particularly from high-fat sources, might be linked to a higher EC risk15. These discrepancies underscore the necessity for additional research to gain a deeper understanding of the intricate relationships between dairy product consumption—specifically distinguishing between high-fat and low-fat options—and the associated risk of EC.

In light of these factors, this study aims to investigate the link between dairy product intake and the risk of EC among Iranian women through a case-control design. By evaluating dietary patterns, including the frequency and type of dairy products consumed, we hope to shed light on the potential impact of dairy on the development of EC in this population. Specifically, we focus on identifying whether total dairy intake, low-fat versus high-fat dairy, influences EC risk. The results of this study could offer valuable insights into enhanced dietary guidelines and public health recommendations, ultimately contributing to the prevention and management of endometrial cancer, particularly in populations with distinct dietary patterns.

Methods

Study design and population

This hospital-based case-control study was conducted among Iranian women aged 40–79 years old, from April 2023 to September 2024. The convenience sampling method was utilized to select participants from individuals referred to the general hospitals of Imam Hossein and Shohada-e-Tajrish in Tehran, Iran. To determine the minimum required sample size for our study, we employed the Schlesselman formula, considering a type I error rate of 5% and a statistical power of 90%16. In the proposed formula, based on the previous study, we assumed the following values: P1 (the probability of exposure among the control group) is 0.3, P2 (the probability of exposure among the case group) is 0.15, the case-to-control ratio is 1:216, 15% dropout. Given these assumptions, we would need approximately 140 patients in the case group and 278 patients in the control group.

The inclusion criteria for the case group, which was recruited from oncology departments, are outlined as follows: (1) The diagnosis of EC should be confirmed by an oncologist, with validation provided through histopathological analysis; (2) The diagnosis of EC must have been established within the past six months with no previous cancer at any site; (3) participants must express a willingness to be included in the study. Patients who received chemotherapy, radiotherapy, or had metastasis before the dietary assessment were excluded from the study. Participants in the control group comprised individuals referred to various hospital departments, including cancer-free outpatients referred to other departments including dermatology, Orthopedics, otolaryngology, ophthalmology, and aesthetics for routine check-ups. Participants in this group were required not to have a prior history of cancer, whether benign or malignant, as well as no inflammatory diseases, and those who had undergone a previous hysterectomy.

In addition, participants in both the case and control groups were excluded from the study under the following conditions: if they had chronic illnesses that might significantly affect dietary intake, such as chronic kidney disease, liver disease, or severe gastrointestinal disorders; if they had undergone bariatric surgery or experienced significant weight loss (10% or more in the last six months); Individuals who are currently pregnant or breastfeeding; if they had adhered to a specific diet over the last six months; if participants misreport their energy intake—whether by indicating less than 500 kcal or more than 3,500 kcal18; or if they complete less than 90% of the questionnaire forms.

In order to ensure accurate comparisons, individuals in both the case and control groups were matched based on two key criteria: age, allowing for a variation of ± 5 years, and body mass index (BMI). The BMI categories were delineated into three subgroups: individuals classified as having normal weight (BMI of 18.5–24.9), those who are overweight (BMI of 25–29.9), as well as those with first-grade obesity (BMI of 30–34.9) and second-grade obesity (BMI of 35–40).

In this study, In-person interviews were conducted by a qualified dietitian to gather detailed information regarding dietary and non-dietary exposures. All participants voluntarily provided their written informed consent, ensuring they fully understood the nature of the study and its implications before engaging in the process. The study protocol was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration and received approval from the Research Ethics Committees of Islamic Azad University, Science and Research Branch (Approval ID: IR.IAU.SRB.REC.1403.106).

Assessment of non-dietary exposures

Characteristics and clinical information were collected through a structured questionnaire, which included questions about: age, BMI, family history of EC and other cancers (in first-degree relatives), smoking status (yes or no), educational Attainment (illiterate, low education, high education), presence of comorbidities (the co-occurence of more than one disorder in the same individual (e.g., hypertension, diabetes, cardiovascular disease)) (yes or no), employment Status (unemployed, housewife, part-time, full-time, retired), history of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) (yes or no), supplement use, encompassed vitamin D, iron, calcium, multivitamin-minerals, and herbal supplements (products derived from plants and commonly used for health-related purposes) (yes or no for each). Further details included first pregnancy age, marriage age, number of children, menarche age (the age at which the participant experienced their first menstrual cycle), history of abortion, history of breastfeeding, menopausal status (premenopausal or postmenopausal), and the history HRT and oral contraceptive pills (OCP) use (yes or no).

Anthropometric measurements were conducted by a trained nutritionist following a standard protocol. Participants were weighed while dressed in light indoor clothing and barefoot. Height measurements were taken with participants standing upright and barefoot, using a calibrated tape measure to ensure accurate results. BMI was calculated by dividing the weight in kilograms (kg) by the square of the height in meters (m²). Waist circumference (WC) was measured at the narrowest point using a non-elastic tape, ensuring that the tape was applied without exerting pressure on the skin.

To assess physical activity (PA) levels, valid Persian translation of the short form of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) was utilized19. All findings were presented in terms of Metabolic Equivalents-hours per week (MET-h/week), offering a standardized metric for comparing the activity levels of participants, effectively.

Dietary assessment

Dietary intake over the past year was assessed using a validated semi-quantitative food frequency questionnaire (FFQ) comprising 168 food items20. The FFQ included a comprehensive list of common Iranian dietary items. The average portion size of each item and the frequency of their intake were asked by an expert nutritionist. Portion sizes were subsequently converted to grams by employing standard Iranian household measures21. The energy and nutrient content was then analyzed by Nutritionist IV software, which is based on the USDA food composition table, with necessary adjustments made in accordance with the Iranian food composition Tables22,23.

The classification of dairy products in this study follows the US Food Guide Pyramid and Iranian food group classification for traditional food items20,24. Low-fat dairy consumption is defined to encompass pasteurized low-fat milk, low-fat cheese, low-fat yogurt, low-fat ice cream, doogh (a traditional beverage made by yogurt), and Kashk (a fermented dairy product). In contrast, high-fat dairy intake was determined by summing the amount of high-fat milk, high-fat cheese, high-fat ice cream, high-fat yogurt, chocolate milk, and cream consumed. In addition, since the previous studies included butter in their analysis, we conducted separate analysis on the association between butter intake and EC risk15. To control for total energy intake, the energy residual method was applied to all dairy-related variables, including total dairy, high-fat dairy, low-fat dairy, and butter intake.

Statistical analysis

Demographic and clinical characteristics of participants across cases and controls were analyzed using standard descriptive statistical methods. The normality of variable distributions was assessed using histogram charts and the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Participants’ characteristics across cases and controls were presented as mean ± SD for continuous variables and as percentages for categorical variables. To compare characteristics between case and control groups, we performed one-way ANOVA for normally distributed continuous variables, Kruskal–Wallis, and Chi-square tests for non-normally distributed continuous variables and categorical variables, respectively. For categorical variables, Chi-square and Fisher’s Exact Test was used depending on expected cell counts.

To evaluate the association between dairy intake and the risk of EC, conditional logistic regression models were employed to estimate odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) across tertiles of energy-adjusted intake for total dairy, high-fat dairy, low-fat dairy, and butter. The matched design (matched on predefined age and BMI categories) was accounted for in all regression models. Three models were constructed: (1) a crude model; (2) Model 1, adjusted for age and waist circumference (WC); and (3) Model 2, additionally adjusted for physical activity, menarche age, first pregnancy age, breastfeeding history, family history of endometrial cancer, family history of cancer, menopausal status, history of OCP use, HRT use, PCOS history, energy intake, and dietary fiber intake. Furthermore, sensitivity analyses were performed in the subgroup of postmenopausal women to assess the robustness and consistency of the observed associations. All statistical analyses were performed using STATA version 17.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA) and SPSS version 26 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA), with a significance level set at P < 0.05 for two-tailed tests.

Results

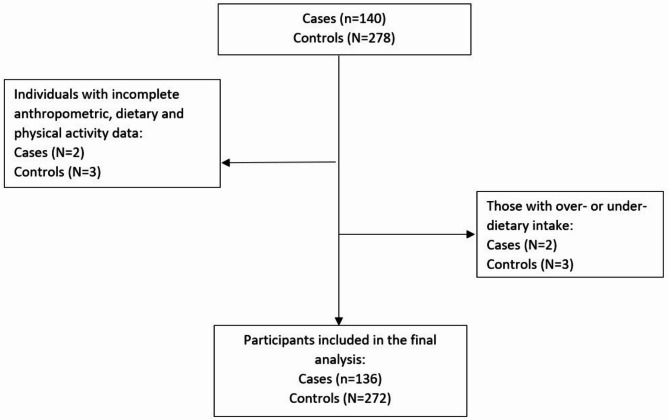

140 EC patients and 278 participants in the control group were included based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Of these, 5 participants (2 from the case and 3 from the control groups) were excluded due to incomplete anthropometric, dietary and physical activity data and an additional 5 participants (2 from the case and 3 from the control groups) were excluded for over- or under-reporting dietary data. Consequently, the final analytical sample included 136 EC patients in the case and 272 participants in the control group (Fig. 1). The demographic, anthropometric, lifestyle, and medical characteristics of participants in both the case and control groups are summarized in Table 1. No significant differences were identified between the two groups regarding age, BMI, physical activity levels, number of children, history of breastfeeding, history of abortions, smoking habits, educational attainment, family history of cancer (including endometrial cancer), menopausal status, history of PCOS, history of HRT, history of OCP usage, comorbidities, or the use of supplements (including iron, herbal products, calcium, and multivitamins). Notably, cases demonstrated significantly higher waist circumference (WC), lower age at menarche and vitamin D supplements usage, higher age at marriage, and age at first pregnancy.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of the study.

Table 1.

Demographic, anthropometric, lifestyle, and medical characteristics of participants in case and control groups.

| Variables | Case (n = 136) | Control (n = 272) | P-value* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years old) | 56.8 ± 6.4 | 56.4 ± 6.6 | 0.587 |

| Body mass index (Kg/m2) | 30.3 ± 5.3 | 30.2 ± 4.9 | 0.939 |

|

Age ≤ 65: Body mass index (Kg/m2) |

30.0 ± 5.3 | 30.3 ± 4.9 | 0.641 |

|

Age > 65: Body mass index (Kg/m2) |

32.5 ± 5.4 | 29.9 ± 4.7 | 0.101 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 103.6 ± 11.3 | 99.3 ± 10.9 | 0.001 |

| Physical Activity (Met.h/wk) | 14.9 ± 5.0 | 15.3 ± 4.8 | 0.439 |

| Menarche age (years old) | 13.2 ± 1.7 | 13.5 ± 1.5 | 0.034 |

| Marriage age (years old) | 19.8 ± 3.9 | 18.2 ± 4.2 | < 0.001 |

| First pregnancy age (years old) | 22.3 ± 4.7 | 19.7 ± 4.0 | < 0.001 |

| Child number | 3.0 ± 1.5 | 2.9 ± 1.6 | 0.446 |

| Breastfeeding history (n, yes) | 118 | 245 | 0.337 |

| Abortion history (n, yes) | 45 | 84 | 0.652 |

| Smoking (n, yes) | 14 | 23 | 0.543 |

| Education status (n) | |||

| Illiterate | 17 | 29 | 0.284 |

| Low education | 99 | 216 | |

| Higher education | 20 | 27 | |

| Employment status (n) | |||

| Unemployed | 1 | 3 | 0.093ᵞ |

| Housewife | 108 | 228 | |

| Part-time | 1 | 11 | |

| Recruitment | 10 | 19 | |

| Retired | 16 | 11 | |

| Family history of endometrial cancer (n, yes) | 8 | 11 | 0.407 |

| Family history of cancer (n, yes) | 35 | 59 | 0.362 |

| Post menopause (n, yes) | 105 | 200 | 0.422 |

| PCOS history (n, yes) | 29 | 50 | 0.488 |

| HRT history (n, yes) | 13 | 19 | 0.363 |

| Ever used OCP (n, yes) | 66 | 148 | 0.263 |

| Comorbidity (n, yes) | 73 | 131 | 0.295 |

| Supplement usage (n, yes) | |||

| Vitamin D | 25 | 75 | 0.033 |

| Calcium | 37 | 84 | 0.445 |

| Herbal | 19 | 29 | 0.329 |

| Iron | 22 | 49 | 0.645 |

| Multivitamin mineral | 14 | 19 | 0.249 |

All values are mean ± standard deviations unless indicated. Significant p-values are highlighted in bold

* Obtained from independent sample T-Test for continuous variables and Chi-square test of independence for categorical variables.

ᵞ P-value calculated using Fisher’s Exact Test due to small expected counts.

Abbreviations: PCOS, Polycystic ovary syndrome; HRT, Hormone-replacement therapy; OCP, oral contraceptive pills;.

Table 2 presents a comparative analysis of average energy-adjusted serving sizes for dietary and nutrient intakes between the case and control groups. In the case group, the average intake of dairy products was 2.82 ± 1.3 servings per day for total dairy consumption. This included an average of 1.43 ± 1.4 servings for high-fat dairy and 1.39 ± 0.7 servings for low-fat dairy. In comparison, the control group exhibited a mean total dairy intake of 2.97 ± 0.6 servings per day. Within this group, the average intake for high-fat dairy was 1.44 ± 0.8 servings per day, while low-fat dairy intake averaged 1.59 ± 0.6 servings per day. The control group exhibited a significantly greater mean intake of vegetables, white meat, legumes, low-fat milk, doogh, and kashk and a lower mean intake of total and high-fat yogurt. No significant differences were noted between the cases and control groups in other food groups. The case group displayed significantly lower intakes of protein, potassium, calcium, zinc and fiber, while simultaneously having significantly higher intakes of carbohydrates, fats, and saturated fats in comparison with the control group.

Table 2.

Dietary and nutrient intakes of study participants across case and control groups.

| Case (n = 136) | Control (N = 272) | P-value* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Food groups ꝉ (Servings/day) | |||

| Grains | 15.60 ± 4.10 | 15.40 ± 2.90 | 0.553 |

| Fruits | 3.10 ± 1.30 | 3.20 ± 0.70 | 0.254 |

| Vegetables | 2.90 ± 1.10 | 4.00 ± 0.90 | < 0.001 |

| Total dairy | 2.82 ± 1.30 | 2.97 ± 0.60 | 0.235 |

| High-fat dairy | 1.43 ± 1.40 | 1.44 ± 0.80 | 0.960 |

| Low-fat dairy | 1.39 ± 0.70 | 1.59 ± 0.60 | 0.002 |

| White meats | 1.10 ± 0.80 | 1.30 ± 0.60 | 0.016 |

| Red meats | 1.00 ± 0.60 | 0.90 ± 0.70 | 0.970 |

| Legumes | 0.14 ± 0.12 | 0.24 ± 0.10 | < 0.001 |

| Nuts | 0.87 ± 0.75 | 0.91 ± 0.39 | 0.486 |

| Milk | 0.48 ± 0.29 | 0.49 ± 0.18 | 0.868 |

| High-fat milk | 0.18 ± 0.22 | 0.14 ± 0.21 | 0.091 |

| Low-fat milk | 0.30 ± 0.22 | 0.35 ± 0.16 | 0.038 |

| Yogurt | 0.57 ± 0.24 | 0.49 ± 0.13 | < 0.001 |

| High-fat yogurt | 0.20 ± 0.20 | 0.11 ± 0.12 | < 0.001 |

| Low-fat yogurt | 0.37 ± 0.20 | 0.38 ± 0.15 | 0.872 |

| Cheese | 1.36 ± 1.24 | 1.53 ± 0.58 | 0.133 |

| Ice cream | 0.11 ± 0.09 | 0.11 ± 0.07 | 0.800 |

| Doogh | 0.08 ± 0.06 | 0.10 ± 0.09 | 0.010 |

| Cream | 0.06 ± 0.08 | 0.06 ± 0.08 | 0.957 |

| Kashk | 0.15 ± 0.19 | 0.19 ± 0.12 | 0.046 |

| Butter (g/day) | 5.90 ± 4.78 | 5.47 ± 4.02 | 0.365 |

| Nutrients | |||

| Energy intake (kcal) | 2484 ± 408 | 2443 ± 272 | 0.289 |

| Protein (% of energy) | 12.40 ± 1.40 | 13.00 ± 1.00 | < 0.001 |

| Fat (% of energy) | 28.90 ± 5.20 | 27.30 ± 3.30 | 0.002 |

| SFA (% of energy) | 9.20 ± 2.10 | 8.50 ± 1.20 | 0.001 |

| PUFA (% of energy) | 5.00 ± 1.70 | 5.00 ± 1.00 | 0.963 |

| Carbohydrate (% of energy) | 61.60 ± 5.30 | 60.20 ± 3.50 | 0.006 |

| Sodium (mg/day)ꝉ | 3983 ± 1518 | 4008 ± 1555 | 0.880 |

| Calcium (mg/day) ꝉ | 902.4 ± 143.0 | 930.6 ± 99.6 | 0.041 |

| Potassium (mg/day) ꝉ | 3786 ± 635 | 4091 ± 391 | < 0.001 |

| Zinc (mg/day) ꝉ | 9.27 ± 1.70 | 9.85 ± 1.20 | < 0.001 |

| Dietary fiber (g/2000 kcal) | 18.00 ± 3.90 | 21.10 ± 2.60 | < 0.001 |

* Obtained from independent sample T-Test. Significant p-values are highlighted in bold.

Abbreviations: SFA, saturated fatty acid; PUFA, polyunsaturated fatty acid.

ꝉ Values are presented as energy adjusted by the residual method.

Association between dairy product intake and EC risk

Table 3 shows the estimated crude and Multivariable-adjusted odds ratios (95% CIs) for EC across tertiles of energy-adjusted total, high-fat, low-fat dairy and butter, in the overall population.

Table 3.

Multivariable-adjusted odds ratios (95% CIs) for endometrial cancer across tertiles of energy-adjusted total, high-fat, low-fat dairy and butter intake.

| T1 | T2 | T3 | P-value for trend | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total dairy | ||||

| Crude | 1.00(ref) | 0.17 (0.10–0.31) | 0.43 (0.26–0.72) | < 0.01 |

| Model 1 | 1.00 (ref) | 0.19 (0.11–0.35) | 0.50 (0.30–0.84) | < 0.01 |

| Model 2 | 1.00 (ref) | 0.14 (0.06–0.30) | 0.31 (0.16–0.61) | < 0.01 |

| High-fat dairy | ||||

| Crude | 1.00 (ref) | 0.24 (0.14–0.42) | 0.55 (0.33–0.91) | 0.01 |

| Model 1 | 1.00 (ref) | 0.25 (0.14–0.44) | 0.63 (0.38–1.06) | 0.05 |

| Model 2 | 1.00 (ref) | 0.18 (0.09–0.37) | 0.39 (0.20–0.76) | 0.01 |

| Low-fat dairy | ||||

| Crude | 1.00 (ref) | 0.39 (0.23–0.66) | 0.46 (0.27–0.77) | 0.01 |

| Model 1 | 1.00 (ref) | 0.38 (0.22–0.66) | 0.39 (0.23–0.67) | < 0.01 |

| Model 2 | 1.00 (ref) | 0.31 (0.15–0.63) | 0.37 (0.19–0.72) | < 0.01 |

| Butter | ||||

| Crude | 1.00 (ref) | 1.02 (0.61–1.77) | 1.07 (0.64–1.48) | 0.78 |

| Model 1 | 1.00 (ref) | 1.02 (0.60–1.75) | 1.08 (0.64–1.83) | 0.76 |

| Model 2 | 1.00 (ref) | 1.20 (0.63–2.28) | 0.84 (0.43–1.63) | 0.63 |

Data are presented as OR and 95% CI. Significant OR and 95% CI and corresponding p-values are highlighted in bold.

The analysis of Conditional logistic regression was used to determine the OR and 95% confidence interval.

Model 1: adjusted for age and waist circumference.

Model 2: additionally adjusted for physical activity, menarche age, first pregnancy age, breastfeeding history, family history of endometrial cancer, family history of cancer, menopausal status, oral contraceptive pills use, hormone replacement therapy use, polycystic ovary syndrome history, energy intake, and dietary fiber intake.

Higher total dairy intake was significantly associated with a reduced risk of EC. In the crude model, individuals in the second and third tertiles had substantially lower odds of EC compared to the lowest tertile (OR for T2 = 0.17; 95% CI: 0.10–0.31 and OR for T3 = 0.43; 95% CI: 0.26–0.72; P-trend < 0.01). This inverse association remained consistent after adjusting for age and WC in Model 1 (OR for T2 = 0.19; 95% CI: 0.11–0.35 and OR for T3 = 0.50; 95% CI: 0.30–0.84; P-trend < 0.01). In the fully adjusted model, the protective association was even stronger (OR for T2 = 0.14; 95% CI: 0.06–0.30 and OR for T3 = 0.31; 95% CI: 0.16–0.61; P-trend < 0.01).

An inverse association was also observed between high-fat dairy intake and EC risk. Compared with the lowest tertile, women in the highest tertile had lower odds of EC in the crude model (OR for T3 = 0.55; 95% CI: 0.33–0.91; P-trend = 0.01). This trend remained in Model 1 (OR for T3 = 0.63; 95% CI: 0.38–1.06; P-trend = 0.05), and was statistically significant in the fully adjusted model (Model 2: OR for T2 = 0.18; 95% CI: 0.09–0.37 and OR for T3 = 0.39; 95% CI: 0.20–0.76; P-trend = 0.01).

Similarly, low-fat dairy intake was inversely associated with EC risk across all models. In the crude model, participants in T2 and T3 had significantly lower odds compared to T1 (OR for T2 = 0.39; 95% CI: 0.23–0.66 and OR for T3 = 0.46; 95% CI: 0.27–0.77; P-trend = 0.01). This association remained consistent after adjusting for covariates in Model 1 (OR for T3 = 0.39; 95% CI: 0.23–0.67; P-trend < 0.01) and Model 2 (OR for T2 = 0.31; 95% CI: 0.15–0.63 and OR for T3 = 0.37; 95% CI: 0.19–0.72; P-trend < 0.01).

No significant association was observed between butter consumption and EC risk in any of the models. The odds ratios for T2 and T3 compared to T1 remained statistically non-significant across all models (Model 2: OR for T2 = 1.20; 95% CI: 0.63–2.28 and OR for T3 = 0.84; 95% CI: 0.43–1.63; P-trend = 0.63).

Sensitivity analysis in postmenopausal women

Table 4 represents the multivariable-adjusted odds ratios (95% confidence intervals) for endometrial cancer across tertiles of energy-adjusted total dairy, high-fat dairy, low-fat dairy, and butter intake in postmenopausal women.

Table 4.

Multivariable-adjusted odds ratios (95% CIs) for endometrial cancer across tertiles of energy-adjusted total, high-fat, low-fat dairy and butter in post-menopausal women.

| T1 | T2 | T3 | P-value for trend | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total dairy | ||||

| Crude | 1.00 (ref) | 0.20 (0.10–0.40) | 0.49 (0.27–0.88) | < 0.01 |

| Model 1 | 1.00 (ref) | 0.23 (0.11–0.45) | 0.52 (0.29–0.95) | 0.02 |

| Model 2 | 1.00 (ref) | 0.16 (0.06–0.39) | 0.42 (0.20–0.91) | 0.02 |

| High-fat dairy | ||||

| Crude | 1.00 (ref) | 0.24 (0.12–0.46) | 0.53 (0.29–0.95) | 0.02 |

| Model 1 | 1.00 (ref) | 0.24 (0.12–0.47) | 0.59 (0.32–1.09) | 0.05 |

| Model 2 | 1.00 (ref) | 0.15 (0.06–0.37) | 0.45 (0.21–0.96) | 0.02 |

| Low-fat dairy | ||||

| Crude | 1.00 (ref) | 0.40 (0.21–0.76) | 0.50 (0.28–0.91) | 0.02 |

| Model 1 | 1.00 (ref) | 0.43 (0.22–0.82) | 0.43 (0.23–0.80) | 0.01 |

| Model 2 | 1.00 (ref) | 0.33 (0.14–0.76) | 0.35 (0.16–0.78) | 0.01 |

| Butter | ||||

| Crude | 1.00 (ref) | 1.01 (0.55–1.85) | 1.10 (0.61–1.97) | 0.74 |

| Model 1 | 1.00 (ref) | 0.98 (0.53–1.82) | 1.15 (0.63–2.09) | 0.65 |

| Model 2 | 1.00 (ref) | 1.08 (0.51–2.28) | 0.69 (0.32–1.50) | 0.34 |

Data are presented as OR and 95% CI. Significant OR and 95% CI and corresponding p-values are highlighted in bold.

The analysis of Conditional logistic regression was used to determine the OR and 95% confidence interval.

Model 1: adjusted for age and waist circumference.

Model 2: additionally adjusted for physical activity, menarche age, first pregnancy age, breastfeeding history, family history of endometrial cancer, family history of cancer, menopausal status, oral contraceptive pills use, hormone replacement therapy use, polycystic ovary syndrome history, energy intake, and dietary fiber intake.

In the fully adjusted model, higher intake of total dairy was significantly associated with a lower risk of endometrial cancer. Compared to women in the lowest tertile, those in the second and third tertiles had 84% and 58% lower risk of EC, respectively (OR for T2 = 0.16; 95% CI: 0.06–0.39 and OR for T3 = 0.42; 95% CI: 0.20–0.91; P-trend = 0.02). A similar inverse association was observed for high-fat dairy intake. Women in the second and third tertiles had significantly reduced risk of EC compared to the lowest tertile (OR for T2 = 0.15; 95% CI: 0.06–0.37 and OR for T3 = 0.45; 95% CI: 0.21–0.96; P-trend = 0.02). For low-fat dairy, higher intake was also associated with a significantly reduced risk. The odds of EC were lower in both T2 (OR = 0.33; 95% CI: 0.14–0.76) and T3 (OR = 0.35; 95% CI: 0.16–0.78; P-trend = 0.01). No significant associations were found for butter intake. The odds ratios for the second and third tertiles were not statistically significant compared to the reference group (OR for T2 = 1.08; 95% CI: 0.51–2.28 and OR for T3 = 0.69; 95% CI: 0.32–1.50; P-trend = 0.34).

Discussion

This study investigated the association between dairy product consumption and the risk of EC in a population of Iranian women using a matched case-control design. Contrary to concerns that dairy products may contribute to the development of estrogen-dependent cancers, our findings suggest a significant inverse association between total dairy intake and EC risk after adjusting for potential confounders. Women with moderate to high intake of total dairy products had substantially lower odds of EC compared to those with the lowest intake. When dairy products were examined by fat content, both low-fat and high-fat dairy intake were independently associated with reduced EC risk. These associations remained consistent in fully adjusted models, indicating that dairy intake may play a protective role. Furthermore, sensitivity analyses conducted among postmenopausal women demonstrated similar inverse associations, reinforcing the robustness of the findings in this hormonally distinct subgroup.

The inverse association observed in our study confirms results of two previous studies25–27whereases most other studies reported no significant association between dairy products intakes and risk of EC15,28,29. Although some studies confirmed that long term use of estrogen therapy is associated with increased risk of EC30there is no evidence supporting the significant relationship between higher intakes of dairy products as the main source of dietary estrogen and increase risk of EC, except one study for butter intake31. According to the latest report of American cancer society, only a high-fat diet is considered as diet-related risk factor for EC due to its impact on obesity32. Given this, a recent meta-analysis study including 18 observational studies on the association between dairy products intake and EC risk found no significant association15. Furthermore, there is lack of evidence showing the increasing effects of dairy products intake on serum levels of estrogen. A randomized intervention trial conducted by Wu et al. indicated that three weeks consumption of cow’s milk don’t increase serum estrone and estradiol levels of pre-pubertal children33. Accordingly, there is strong evidence suggesting the estrogen contents in cow’s milk are too low to cause unfavorable effects on human health34. Also, it is demonstrated that estrogen carcinogenesis follows a dose-dependent manner35. Regarding, a 26-years follow up showed that the association between total dairy intakes and EC was significant only among postmenopausal women not using estrogen-containing hormones who consumed more than or equal to 3 serving dairy per day36. In fact, recent studies show that dietary approaches such as Mediterranean diet characterized by high intake of cereals, legumes, vegetables, and fruits and low intake of meat and meat products, milk and dairy products may decrease risk of EC37. It worth mentioning that in our study, the average intake of dairy products was 2.82 ± 1.3 servings per day in case group which was lower than control group.

For the negative association observed in our study, several nutrients in dairy products have been reported to inhibit carcinogenesis such as calcium and conjugated linoleic acid (CLA). Considerable contents of calcium in dairy products may reduce EC risk via inhibiting the growth of cancer cells and promoting apoptosis in endometrial cancer cells38. Also, the role of calcium in regulation of estrogen levels can result in reducing the risk associated with excessive estrogen39. Furthermore, dairy products are rich in vitamin D acting with calcium synergistically to exert its anti-proliferative and pro-differentiation effects40. Accordingly, the protective effect of dairy consumption on EC may attribute to anti-inflammatory properties of them as the chronic inflammation is a chronic risk factors for variety of cancers41,42. CLA, plays its role as anticarcinogen through estrogen reducing effects, apoptosis induction, inhibition of cell proliferation and modulation of estrogen receptor10,43,44. However, high amount of odd-chain fatty acids in dairy products may partially explain neutral or even negative association between high-fat dairy products consumption and risk of chronic diseases observed in recent studies45,46. Furthermore, the Iranian were reported to consume more cheese between 1991 and 2021 led to higher calcium intake47which is suggested to be related with a lower risk of estrogen-dependent cancer48,49.

Our findings suggest that postmenopausal women may benefit from regular consumption of dairy products, as inverse associations between both total and subtypes of dairy intake and the risk of EC remained statistically significant in this subgroup. However, existing literature on this association remains inconclusive. For instance, a case-control study conducted in 2002 among postmenopausal Swedish women reported a non-significant inverse association between dairy consumption and EC risk, providing limited support for a protective effect50. In contrast, data from a 2012 prospective cohort study with 26 years of follow-up suggested an increased risk of EC associated with higher dairy intake, particularly among postmenopausal women not receiving hormone therapy36. Importantly, our models were adjusted for hormone replacement therapy use, minimizing potential confounding related to exogenous hormone exposure. This apparent discrepancy highlights the need to consider modifying factors such as hormonal status, type and quantity of dairy products consumed, and methodological differences across studies. Further research is warranted to clarify these associations and explore potential underlying biological mechanisms. Another important result of current study was the inverse significant association between the moderate intake of total, low-fat and high-fat dairy products (1.23–1.66 and 0.84–1.72 ser/day, respectively) and risk of EC compared to lower intakes in full adjusted model. These findings highlight the potential protective role of moderate dairy consumption in the context of hormone-related cancers51,52. Although a previous study reported a positive association between butter consumption and EC risk31our analysis found no significant association. However, the relationship between high-fat dairy products consumption and chronic disease are still under investigation and observational evidence doesn’t support the hypothesis that dairy fats contribute to endometrial cancer.

Strength and limitation

This study provides several noteworthy advantages. First, our study is the only study conducted in Iran investigating the association between dairy intakes and EC, also studies on this relationship are hardly find in Asia. Utilizing a validated semi-quantitative food frequency questionnaire (FFQ) and a strict case-control design are two strengths that allowed for a complete dietary evaluation that was especially suited to Iranian dietary conditions. However, our study has some limitations that should be considered. As dietary information was gathered retrospectively following cancer diagnosis, there is a possibility of memory bias due to the case-control design. Furthermore, because hospital-based controls may differ from the general population in terms of health-seeking behavior or other unmeasured characteristics, the findings may not be as broadly applicable. Given the use of a convenience sample drawn from hospital attendees, the possibility of selection bias cannot be excluded, and the results should be interpreted with caution; future population-based studies are needed to confirm these associations. Worth mentioning, the cross-sectional evaluation of diet makes it difficult to take into consideration how dietary practices may vary over time, which may mask the actual relationships between dietary inflammation and the risk of endometrial cancer. Smoking and alcohol consumption were recorded as binary variables; however, detailed data such as smoking intensity, duration, cessation timing, and alcohol quantity were not collected. Additionally, underreporting of alcohol use was likely due to cultural and legal restrictions. Finally, due to the limited number of participants in the premenopausal subgroup and the resulting instability of the effect sizes, we restricted our sensitivity analysis to postmenopausal women. This limitation underscores the need for future studies with larger premenopausal samples to evaluate potential age- and hormone-related differences in the association between dairy intake and EC risk. These limitations may lead to residual confounding and should be addressed in future studies.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our findings indicate that moderate consumption of dairy products, including both low-fat and high-fat varieties, may be associated with a reduced risk of EC, particularly among postmenopausal women. These associations remained significant after controlling for a wide range of confounding factors, including dietary, reproductive, and lifestyle variables. While butter intake showed no significant relationship with EC risk, the protective associations observed with other dairy subtypes underscore the potential role of dairy in the dietary prevention of hormone-related cancers. Until then, our results contribute to a growing body of evidence suggesting that moderate dairy consumption may be a beneficial component of cancer-preventive dietary patterns in women.

Acknowledgements

The authors express their appreciation to the participants of the study for their enthusiastic support and to the staff of the involved hospitals for their valuable help.

Author contributions

Overall, SAK and MG supervised the project and approved the final version of the manuscript to be submitted. EE and MG designed the research; EE gathered data; EE and AN analyzed and interpreted the data; EE drafted the initial manuscript; and SAK and MG critically revised the manuscript.

Data availability

The datasets analyzed in the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study obtained ethical approval from the Research Ethics Committees of Islamic Azad University, Science and Research Branch (Approval ID: IR.IAU.SRB.REC.1403.106). All participants voluntarily provided their written informed consent, ensuring they fully understood the nature of the study and its implications before engaging in the process.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Bray, F. et al. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. Cancer J. Clin.74, 229–263 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yasin, H. K., Taylor, A. H. & Ayakannu, T. A narrative review of the role of diet and lifestyle factors in the development and prevention of endometrial cancer. Cancers13, 2149 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clinton, S. K., Giovannucci, E. L., Hursting, S. D. & The World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research Third Expert Report on Diet. Nutrition, physical activity, and cancer: impact and future directions. J. Nutr.150, 663–671. 10.1093/jn/nxz268 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jeyaraman, M. M. et al. Dairy product consumption and development of cancer: an overview of reviews. BMJ Open.9, e023625 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ruiz, R. B. & Hernández, P. S. Diet and cancer: risk factors and epidemiological evidence. Maturitas77, 202–208 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.(WCRF/AICR). W. C. R. F. A. I. f. C. R. Diet, nutrition, physical activity and endometrial cancer, (2018). https://www.aicr.org/research/the-continuous-update-project/endometrial-cancer/

- 7.Bandera, E. V., Kushi, L. H., Moore, D. F., Gifkins, D. M. & McCullough, M. L. Consumption of animal foods and endometrial cancer risk: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Cancer Causes Control. 18, 967–988. 10.1007/s10552-007-9038-0 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Comerford, K. B. et al. Global review of dairy recommendations in Food-Based dietary guidelines. Front. Nutr.8, 671999. 10.3389/fnut.2021.671999 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xu, W. H. et al. Nutritional factors in relation to endometrial cancer: a report from a population-based case-control study in shanghai, China. Int. J. Cancer. 120, 1776–1781. 10.1002/ijc.22456 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang, J. et al. Induction of apoptosis by c9, t11-CLA in human endometrial cancer RL 95 – 2 cells via ERα-mediated pathway. Chem. Phys. Lipids. 175–176, 27–32. 10.1016/j.chemphyslip.2013.07.009 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Biel, R. K. et al. Risk of endometrial cancer in relation to individual nutrients from diet and supplements. Public. Health Nutr.14, 1948–1960. 10.1017/s1368980011001066 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Qin, L. Q., Wang, P. Y., Kaneko, T., Hoshi, K. & Sato, A. Estrogen: one of the risk factors in milk for prostate cancer. Med. Hypotheses. 62, 133–142. 10.1016/s0306-9877(03)00295-0 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maruyama, K., Oshima, T. & Ohyama, K. Exposure to exogenous Estrogen through intake of commercial milk produced from pregnant cows. Pediatr. Int.52, 33–38. 10.1111/j.1442-200X.2009.02890.x (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Renehan, A. G. et al. Insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-I, IGF binding protein-3, and cancer risk: systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Lancet363, 1346–1353. 10.1016/s0140-6736(04)16044-3 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li, X., Zhao, J., Li, P. & Gao, Y. Dairy products intake and endometrial cancer risk: A Meta-Analysis of observational studies. Nutrients1010.3390/nu10010025 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Schlesselman, J. J. Case-control Studies: Design, Conduct, AnalysisVol. 2 (Oxford University Press, 1982).

- 17.Bahadoran, Z., Karimi, Z., Houshiar-rad, A., Mirzayi, H. R. & Rashidkhani, B. Is dairy intake associated to breast cancer? A case control study of Iranian women. Nutr. Cancer. 65, 1164–1170. 10.1080/01635581.2013.828083 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Willett, W. Nutritional Epidemiology (Oxford University Press, 2012).

- 19.Moghaddam, M. B. et al. The Iranian version of international physical activity questionnaire (IPAQ) in iran: content and construct validity, factor structure, internal consistency and stability. World Appl. Sci. J.18, 1073–1080 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Esfahani, F. H., Asghari, G., Mirmiran, P. & Azizi, F. Reproducibility and relative validity of food group intake in a food frequency questionnaire developed for the Tehran lipid and glucose study. J. Epidemiol.20, 150–158 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ghaffarpour, M., Houshiar-Rad, A. & Kianfar, H. The manual for household measures, cooking yields factors and edible portion of foods. Tehran: Nashre Olume Keshavarzy. 7, 42–58 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bowman, S. A., Friday, J. E. & Moshfegh, A. J. MyPyramid Equivalents Database, 2.0 for USDA survey foods, 2003–2004: documentation and user guide. US Department of Agriculture (2008).

- 23.Azar, M. C. & Sarkisian, E. G.

- 24.Agriculture, U. S. D. o. The Food Guide Pyramid. (U.S. Department of Agriculture, (1992).

- 25.Barbone, F., Austin, H. & Partridge, E. E. Diet and endometrial cancer: a case-control study. Am. J. Epidemiol.137, 393–403. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116687 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.La Vecchia, C., Decarli, A., Fasoli, M. & Gentile, A. Nutrition and diet in the etiology of endometrial cancer. Cancer57, 1248–1253. https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-0142(19860315)57:6%3C1248::aid-cncr2820570631%3E3.0.co;2-v (1986). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Plagens-Rotman, K., Żak, E. & Pieta, B. Odds ratio analysis in women with endometrial cancer. Menopausal Rev.15, 12–19. 10.5114/pm.2016.58767 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Terry, P., Harri, V., Alicja, W., Weiderpass, E. & and Dietary factors in relation to endometrial cancer: A nationwide Case-Control study in Sweden. Nutr. Cancer. 42, 25–32. 10.1207/S15327914NC421_4 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bravi, F. et al. Food groups and endometrial cancer risk: a case-control study from Italy. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol.200, 293e291–293e297. 10.1016/j.ajog.2008.09.015 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Razavi, P. et al. Long-term postmenopausal hormone therapy and endometrial cancer. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev.19, 475–483. 10.1158/1055-9965.Epi-09-0712 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Merritt, M. A. et al. Investigation of dietary factors and endometrial cancer risk using a nutrient-wide association study approach in the EPIC and nurses’ health study (NHS) and NHSII. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev.24, 466–471. 10.1158/1055-9965.Epi-14-0970 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rock, C. L. et al. American cancer society guideline for diet and physical activity for cancer prevention. Cancer J. Clin.70, 245–271. 10.3322/caac.21591 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wu, J. et al. Short-term serum and urinary changes in sex hormones of healthy pre-pubertal children after the consumption of commercially available whole milk powder: a randomized, two-level, controlled-intervention trial in China. Food Funct.13, 10823–10833. 10.1039/d2fo02321k (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Snoj, T. & Majdič, G. MECHANISMS IN ENDOCRINOLOGY: estrogens in consumer milk: is there a risk to human reproductive health? Eur. J. Endocrinol.179, R275–r286. 10.1530/eje-18-0591 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yager, J. D. Mechanisms of Estrogen carcinogenesis: the role of E2/E1–quinone metabolites suggests new approaches to preventive intervention – A review. Steroids99, 56–60. 10.1016/j.steroids.2014.08.006 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ganmaa, D., Cui, X., Feskanich, D., Hankinson, S. E. & Willett, W. C. Milk, dairy intake and risk of endometrial cancer: a 26-year follow-up. Int. J. Cancer. 130, 2664–2671. 10.1002/ijc.26265 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ricceri, F. et al. Diet and endometrial cancer: a focus on the role of fruit and vegetable intake, mediterranean diet and dietary inflammatory index in the endometrial cancer risk. BMC Cancer. 17, 757. 10.1186/s12885-017-3754-y (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xin, X. et al. The suppressive role of calcium sensing receptor in endometrial cancer. Sci. Rep.8, 1076. 10.1038/s41598-018-19286-1 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Peterlik, M., Grant, W. B., Cross, H. S. & Calcium Vitamin D and cancer. Anticancer Res.29, 3687 (2009). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McCullough, M. L., Bandera, E. V., Moore, D. F. & Kushi, L. H. Vitamin D and calcium intake in relation to risk of endometrial cancer: A systematic review of the literature. Prev. Med.46, 298–302. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2007.11.010 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nieman, K. M., Anderson, B. D. & Cifelli, C. J. The effects of dairy product and dairy protein intake on inflammation: A systematic review of the literature. J. Am. Coll. Nutr.40, 571–582. 10.1080/07315724.2020.1800532 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nishida, A. & Andoh, A. The role of inflammation in cancer: mechanisms of tumor initiation, progression, and metastasis. Cells14, 488 (2025). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bocca, C., Bozzo, F., Cannito, S., Colombatto, S. & Miglietta, A. CLA reduces breast cancer cell growth and invasion through ERalpha and PI3K/Akt pathways. Chem. Biol. Interact.183, 187–193. 10.1016/j.cbi.2009.09.022 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Benjamin, S., Prakasan, P., Sreedharan, S., Wright, A. D. & Spener, F. Pros and cons of CLA consumption: an insight from clinical evidences. Nutr. Metab. (Lond). 12, 4. 10.1186/1743-7075-12-4 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gaeini, Z., Bahadoran, Z., Mirmiran, P., Feyzi, Z. & Azizi, F. High-Fat dairy products May decrease the risk of chronic kidney disease incidence: A Long-Term prospective cohort study. J. Ren. Nutr.33, 307–315. 10.1053/j.jrn.2022.10.003 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kratz, M., Baars, T. & Guyenet, S. The relationship between high-fat dairy consumption and obesity, cardiovascular, and metabolic disease. Eur. J. Nutr.52, 1–24. 10.1007/s00394-012-0418-1 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Roustaee, R. et al. A 30-year trend of dairy consumption and its determinants among income groups in Iranian households. Front. Public. Health. 12–202410.3389/fpubh.2024.1261293 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 48.Kazemi, A. et al. Intake of various food groups and risk of breast cancer: A systematic review and Dose-Response Meta-Analysis of prospective studies. Adv. Nutr.12, 809–849. 10.1093/advances/nmaa147 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Merritt, M. A., Cramer, D. W., Vitonis, A. F., Titus, L. J. & Terry, K. L. Dairy foods and nutrients in relation to risk of ovarian cancer and major histological subtypes. Int. J. Cancer. 132, 1114–1124. 10.1002/ijc.27701 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Terry, P., Vainio, H., Wolk, A. & Weiderpass, E. Dietary factors in relation to endometrial cancer: a nationwide case-control study in Sweden. Nutr. Cancer. 42, 25–32. 10.1207/s15327914nc421_4 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.An, S., Gunathilake, M. & Kim, J. Dairy consumption is associated with breast cancer risk: a comprehensive meta-analysis stratified by hormone receptor and menopausal status, and age. Nutr. Res.138, 68–75. 10.1016/j.nutres.2025.02.003 (2025). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhao, Z. et al. The association between dairy products consumption and prostate cancer risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Nutr.129, 1714–1731. 10.1017/s0007114522002380 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets analyzed in the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.