Abstract

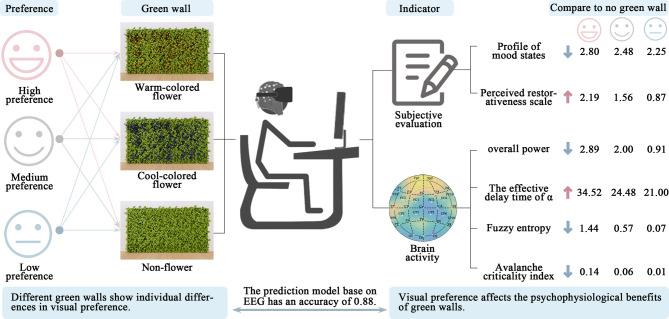

Green walls are a common biophilic design element in indoor environments, contributing to the improvement of individuals’ psychophysiological health. This study, utilizing virtual reality technology, constructed three different types of green walls: cool-colored flower, warm-colored flower, and non-flower combined green walls, with no green wall serving as the control. The visual preference vote (VPV), subjective evaluations, and electroencephalogram (EEG) of 26 young adults were measured to investigate how varying levels of preference for green walls influence restoration. The study found that green walls reduced psychophysiological stress levels; however, significant individual differences were observed in visual preferences. High-preference green walls were associated with more positive emotional responses and more stable patterns of brain activity. Compared to medium- and low-preference conditions, the changes in brain oscillatory power were 1.39–2.96 times greater, and the effective delay time of alpha rhythms was 1.49–1.68 times longer, suggesting enhanced neural stability. Exposure to high-preference green walls induced smaller and faster neural avalanche activities. The avalanche criticality index (ACI), an indicator of how close brain activity is to a critical and balanced state, decreased by up to 30.31%, reflecting enhanced stability and comfort of neural dynamics. VPV was closely related to psychophysiological indicators (p < 0.05). A prediction model of green wall preference was constructed based on four EEG features, with the random forest classifier achieving an accuracy of 0.88. Among these, ΔACI was the most important predictor of VPV (weight: 0.48). This study provides a method for predicting individual preferences for green walls, offering strong evidence for indoor green wall design.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-025-19425-5.

Keywords: Green walls, Visual preferences, EEG, Psychophysiological restoration, VR

Subject terms: Psychology, Environmental sciences

Introduction

Rapid urbanization has resulted in an increasing number of people spending significant amounts of time indoors1,2. Prolonged exposure to visually monotonous environments can exacerbate mental stress, impair attention, and lead to mental disorders and sleep disturbances. According to biophilic design theory, incorporating greenery can enhance indoor quality, benefiting human psychophysiological health and improving work performance. Green walls, which occupy minimal space, are a common biophilic design element in indoor settings3,4.

An increasing number of studies have highlighted the advantages of indoor green walls, especially in enhancing air quality and thermal comfort5,6. However, as vision is a critical sense for recognizing and processing environmental information, few studies examined how visual exposure to green walls influences users7. Yeom et al.4 and Latini et al.7 investigated the benefits of indoor green walls on psychophysiological restoration from the perspective of visible area, but the number of studies is limited, and these studies deliberately avoided colors other than green to eliminate interference. The color of green walls also plays a significant role in stress recovery. Zhang et al.8 pointed out that cool-toned flowers and green leaves can create a more relaxing plant composition, better alleviating physiological stress, while warm-toned flowers and green leaves evoke more excitement and positive emotions. Furthermore, they emphasized that regardless of the inherent properties of the color, an individual’s preference for that color is crucial for psychophysiological restoration9. Overall, research on the visual stimuli of indoor green walls for psychophysiological restoration is lacking, and investigating how green walls of varying colors influence psychophysiological restoration based on visual preference is essential.

Comprehensive assessments combining psychological and physiological indicators have proven effective for evaluating psychophysiological restoration in indoor greening studies. Psychological responses are often measured using subjective tools such as the Profile of Mood States (POMS), which reflects emotional changes in both directions and has been shown to effectively capture the emotional effects of indoor greenery10,11. Additionally, based on stress recovery theory (SRT) and attention restoration theory (ART), some scholars have proposed the Perceived Restorativeness Scale (PRS), which evaluates the impact of indoor greening on perceived restorative levels from four aspects: being away, extent, fascination, and compatibility. This scale has been widely used12,13. The dimension of being away describes how effectively an environment enables individuals to mentally distance themselves from everyday stressors, work-related tasks, or mental burdens, thereby creating a psychological sense of distance from routine life14,15. Extent reflects how rich and coherent an environment is perceived to be, indicating whether it offers sufficient cognitive scope for exploration and immersive experience. This includes the diversity of environmental content and the degree to which its elements are harmoniously integrated to form the perception of a “whole world.” Fascination describes the environment’s ability to effortlessly capture involuntary attention without requiring conscious effort from the individual. This form of attention is considered “soft,” allowing for engagement without inducing mental fatigue16. Compatibility pertains to the alignment between the environment and the individual’s personal goals, preferences, or needs, and whether the setting supports the activities the individual intends to pursue. Collectively, these four dimensions constitute the subjective perception of an environment’s restorative potential15.

Common physiological response measurements include blood pressure, heart rate variability (HRV), and electroencephalogram (EEG). The benefits of indoor greening on psychophysiological improvement manifest as lower blood pressure17, dominance of the parasympathetic nervous system, and reduced stress levels of the autonomic nervous system18. Ma et al.19 found that green walls contribute to reductions in systolic blood pressure and heart rate, thereby alleviating cognitive stress. Sedghikhanshir et al.20 reported that exposure to green walls, compared to environments without green walls, enhanced parasympathetic nervous system (PNS) activity, indicating a stress-relieving effect. This was reflected by a significant rise in RMSSD and a notable reduction in LF/HF. The brain serves as a key regulator of psychophysiological functioning. The impact of indoor green walls on brain activity deserves in-depth research. EEG signals are synchronous electrical oscillations generated by the transmission of signals among cortical neurons. While autonomic nervous system (ANS) indicators such as blood pressure and HRV primarily reflect peripheral physiological responses, EEG is particularly effective in capturing the rapid dynamic changes in cortical activity. Compared to fMRI, EEG offers superior temporal resolution. Within EEG analysis, event-related potentials (ERPs) reflect brain responses that are time-locked to stimulus onset, whereas analyses of neural oscillations capture both time-locked (evoked) and non-time-locked (induced) activity. Therefore, oscillatory measures are particularly suitable for examining non-task-dependent brain dynamics. In this study, the term “EEG” specifically refers to the analysis of neural oscillatory activity. Therefore, EEG can accurately reflect the impact of indoor green walls on physiological stress levels. Moreover, numerous studies have demonstrated strong associations between EEG and psychological responses21,22. Accordingly, this study focuses primarily on EEG to investigate how different types of green walls influence university students’ psychophysiological restoration. Among EEG frequency-domain features, the alpha band (α, 8–13 Hz) is one of the most widely used neural indicators in green wall research23. α oscillations are generally associated with relaxed wakefulness, reduced mental workload, and disengagement of attention4,19. Li et al.23 found that exposure to green walls resulted in reduced overall EEG power and elevated alpha activity, indicating a state of greater relaxation and lower stress. Ma et al.19 further reported that compared to no green wall, exposure to green walls significantly enhanced alpha oscillations, particularly in the right hemisphere, reflecting improved emotional regulation and relaxed spatial attention. In addition, Yeom et al.4 found that, compared to large green walls, small green wall exposure elicited stronger alpha activity, especially in the parietal region, indicating greater efficacy in supporting cognitive restoration. As EEG application in indoor environment research deepens, some studies have pointed out that nonlinear dynamic features can better reflect complex brain activity. Frescura et al.24 noted that the effective delay time of α (τe) is closely related to preference, emotion, and comfort. Hu et al.25 proposed that fuzzy entropy can better reflect the overall disorder of brain activity, closely linked to subjective perception. These features describe brain oscillatory activity and mainly rely on linear analyses in the frequency domain, whereas the brain also exhibits avalanche activity, which is better characterized through nonlinear dynamic analyses. Lu et al.26 and Liu et al.27 pointed out that the nonlinear dynamic features of brain avalanche activity are strongly connected to psychophysiological comfort, with avalanche size (AS), avalanche duration (AD), branching parameter (σ), and avalanche critical index (ACI) serving as effective evaluation indicators. They also suggested that the closer avalanche activity is to a stable, healthy critical state, the lower the overall power of brain oscillations, allowing the brain to better process and integrate external information. Therefore, investigating how indoor green walls influence the multidimensional characteristics of brain activity is essential. Additionally, some scholars have achieved free control of green wall elements (such as shape and size) through VR simulation, avoiding interference from irrelevant indoor environment factors4,7. They have demonstrated that EEG, VR, and laboratory environment control (LEC) can effectively explore the impact of green walls on psychophysiological restoration23,28. Real-world green wall intervention research requires post-construction studies, leading to increased research time and costs, with confounding factors such as plant decay being unavoidable. VR has been proven to achieve almost consistent perception with the real world, offering low-cost and flexible advantages, providing strong technical support for indoor green wall research29. In summary, the comprehensive psychological and physiological measurement methods used in indoor greening research provide strong support for studying the psychophysiological restoration benefits of indoor green walls. EEG signals can accurately indicate the influence of indoor green walls on psychophysiological restoration, but current research primarily focuses on the frequency domain features of brain oscillatory activity, with limited attention to avalanche activity and nonlinear dynamic features. Therefore, to better understand the neural effects of indoor green walls, a broader range of EEG indicators should be employed, and combining this with VR has become an effective means for pre-occupancy evaluation of green walls.

Intense academic demands often confine university students to indoor environments, limiting their exposure to natural settings. Reduced exposure to natural environments has been associated with decreased academic performance and heightened risks of mental health problems, such as depression and anxiety. Investigating how various types of green walls affect psychological and physiological health offers important insights for enhancing university students’ well-being. This study utilized VR equipment to present three different types of green walls: cool-colored flower combined green wall (CFW), warm-colored flower combined green wall (WFW), and non-flower combined green wall (NFW). Participants rated their visual preference levels while EEG signals were measured and compared to data collected under no green wall (NW) conditions. The objectives of this study are: (1) To determine the effects of different types of green walls on university students’ subjective perceptions and brain activities. (2) To understand the relationship between green wall preferences and emotions as well as brain activities. (3) To explore the mechanisms linking brain activities to individual green wall preferences. The findings are intended to contribute to the theoretical understanding of indoor environmental optimization and psychophysiological recovery, and to serve as a reference for integrating green walls into interior design practices. The overall framework of the study is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Overview of the study framework. Participants viewed three green wall types and reported visual preferences. Subjective (Profile of Mood States, Perceived Restorativeness Scale) and EEG (overall power, the effective delay time of alpha oscillations, fuzzy entropy, avalanche critical index) responses were measured and compared to a no-green-wall baseline. An EEG-based model predicted preference with 0.88 accuracy, showing that visual preference influences psychophysiological outcomes.

Methods

Participants

Voluntary participants were recruited through the official website of the college at Qingdao University of Technology (QUT). They were screened by phone to ensure that they had no mental or physical health conditions and no history of traumatic brain injury. The required sample size was determined using G*Power, assuming α = 0.05, power = 0.80, and an effect size of 0.5, resulting in a minimum of 17 participants26. Considering the potential for data contamination during the experiment—such as signal distortion caused by poor electrode contact, ocular artifacts, or electromyographic interference—some EEG recordings of suboptimal quality were excluded from further analysis. As a result, a total of 26 young university students (male: 13, female: 13), aged between 18 and 28 years and with a body mass index (BMI) within the normal range (19–24.9 kg/m²), were ultimately selected to participate and complete the experiment. Table 1 presents the basic information of the participants. To obtain clean EEG data, participants were required to adhere to the following guidelines before and during the experiment: (1) On the day before the experiment, participants should not smoke, drink alcoholic or caffeinated beverages, or take neurogenic drugs, and they should ensure adequate sleep. (2) Two hours before the experiment, participants should avoid strenuous activities to ensure normal physiological indicators. (3) Ensure that the scalp is clean before the experiment. All participants had previous VR experience through VR games or other VR experiments, and none reported discomfort. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Qingdao University of Technology in January 2024 (QUT-HEC-2024150). All procedures complied with relevant ethical guidelines and regulations, including the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from all participants before the study commenced.

Table 1.

The basic information of the participants.

| N | Age | Height (cm) | Weight (kg) | BMI (kg/m²) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Mean ± SD) | |||||

| Male | 13 | 22.08 ± 2.99 | 179.92 ± 5.30 | 77.92 ± 6.12 | 24.08 ± 1.78 |

| Female | 13 | 22.15 ± 2.58 | 164.00 ± 3.21 | 51.46 ± 3.15 | 19.15 ± 1.32 |

| Total | 26 | 22.12 ± 2.73 | 171.96 ± 9.18 | 64.69 ± 14.31 | 21.62 ± 2.95 |

(SD: standard deviation)

Experimental setup

The experiment was started from March 2, 2024, to May 4, 2024, daily from 9:00 AM to 11:00 AM, in a laboratory (5 × 4 × 2.6 m) at QUT (see Fig. 2). An indoor environmental quality (IEQ) monitoring sensor was centrally positioned in the laboratory at a height of 1.0 m from the floor, following the guidelines of ASHRAE Standard 55-201730. The thermal environment of the laboratory was controlled by a split air conditioner, ensuring Predicted Mean Vote (PMV) = ± 0.5, with no noise sources and an indoor sound pressure level not exceeding 40 dBA. Specific parameter settings are detailed in Table 2. The thermal resistance of participants’ clothing was standardized at 0.5 clo, consisting of a short-sleeved shirt, cotton trousers, and socks31. Throughout the experiment, all participants remained in a seated posture without engaging in additional physical activity, resulting in an approximate metabolic rate of 1.0 met32.

Fig. 2.

Experimental setup and equipments.

Table 2.

Experimental parameter settings.

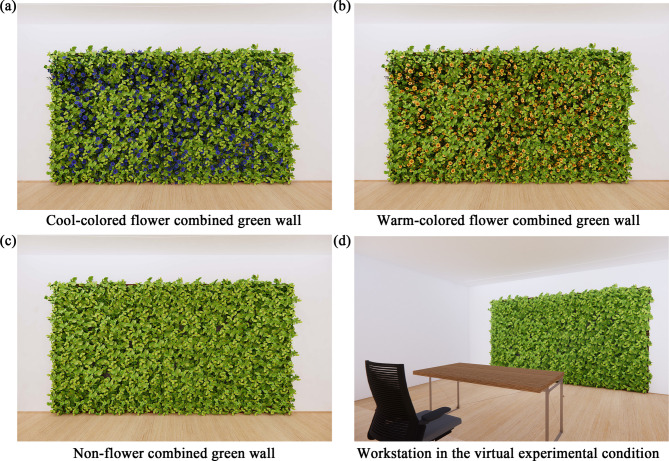

Different green walls

The green wall was virtual, constructed using the 3D design software SketchUp 2023 and rendered with the real-time visualization software Enscape 3.5.6, producing images at a resolution of 12,960 × 12,960 pixels36. All other rendering parameters were set to their default values37. Four green wall conditions were set: (a) no green wall (NW), (b) cool-colored flower combined green wall (CFW), (c) warm-colored flower combined green wall (WFW), and (d) non-flower combined green wall (NFW). A room measuring 2.7 m (H) x 6 m (W) x 4.5 m (L) was constructed for this study, containing a standard office desk and chair facing the green wall, which measured 2.2 m (H) x 4 m (W). The base color of the green wall was green, featuring pothos plants, a common indoor plant known for effectively purifying air quality. The wall was adorned with pansies, a popular flower available in a wide range of colors9. Yellow and purple pansies were selected to create the CFW and WFW, respectively, covering 50% of the plant wall area, with identical flower sizes and distribution positions except for the color. NW served as the baseline to better understand the psychophysiological responses of participants to different green walls. All other design factors, such as illumination and spatial configuration, were kept consistent (see Fig. 3). The visual observation point of the participants was 1.1 m above the ground in front of the desk, positioned 4.0 m from the green wall. To assess the realism of the virtual environment, participants completed the Igroup Presence Questionnaire (IPQ)38 after the VR exposure. The questionnaire consists of 14 items covering four dimensions: general presence, spatial presence, involvement, and experienced realism, with a total score ranging from 20 to 100. The results showed average scores of 65.32 for general presence (IPQ-D1), 65.33 for spatial presence (IPQ-D2), 59.58 for involvement (IPQ-D3), and 58.42 for experienced realism (IPQ-D4), indicating that participants generally perceived the virtual green wall environment as immersive and realistic. The slightly lower score for “experienced realism” may be explained by the fact that the current VR exposure involved only visual stimuli and lacked additional multisensory cues (e.g., scent, temperature, airflow), which are known to enhance realism. These values are also comparable to those reported in previous VR studies on indoor environments—for example, Sedghikhanshir et al.20 reported scores of 66.07 for IPQ-D1, 60.97 for IPQ-D2, 53.12 for IPQ-D3, and 54.53 for IPQ-D4. The somewhat lower IPQ-D1 score in our study compared to their findings may be attributed to the relatively simpler room scene used here, which was less enriched than the virtual environment in their study. By contrast, the scores for IPQ-D2-4 in our study were slightly higher, suggesting that participants still experienced a satisfactory level of immersion despite the simplified environment. These findings support the validity of the virtual model39.

Fig. 3.

(a-c) Different green walls and (d) virtual environment.

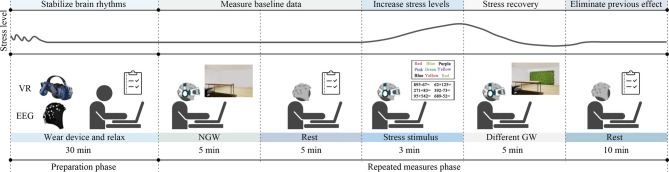

Experimental procedure

The experimental procedure includes the preparation phase and the repeated measures phase (see Fig. 4)4. During the preparation phase, each participant was given 30 min to relax and equip the EEG device. Researchers provided a brief overview to the experimental process (about 5 min) and collected the participants’ personal information. During the repeated measures phase, participants wore the VR equipment (HTC Vive Pro), a VR headset with a head-mounted display, providing a total resolution of 2880 × 1660 pixels, a refresh rate of 90 Hz, and a field of view of 110°. Participants first viewed the NW for 5 min, then removed the VR equipment to complete a subjective evaluation and rest, serving as the baseline condition. Next, participants underwent 3 min of stress stimulation, consisting of a 1-minute Stroop test and a 2-minute arithmetic test. In the Stroop test, participants were shown words representing colors and required to state the font color instead of the word itself. After the Stroop test, participants were asked to quickly solve addition and subtraction problems within 1000. Upon completing the stress stimulation, participants viewed the designated green wall for 5 min, with the order of the CFW, WFW, and NFW being randomized. Subsequently, the VR headset was removed, and participants were asked to complete a subjective evaluation. During the repeated measures phase, participants remained seated, with continuous EEG signal measurement except during rest periods. After a 10-minute rest, the next set was initiated. This procedure ensured that participants experienced each green wall condition under controlled and consistent circumstances, allowing for the collection of reliable and comparable data on their psychological and physiological responses.

Fig. 4.

Experimental procedure.

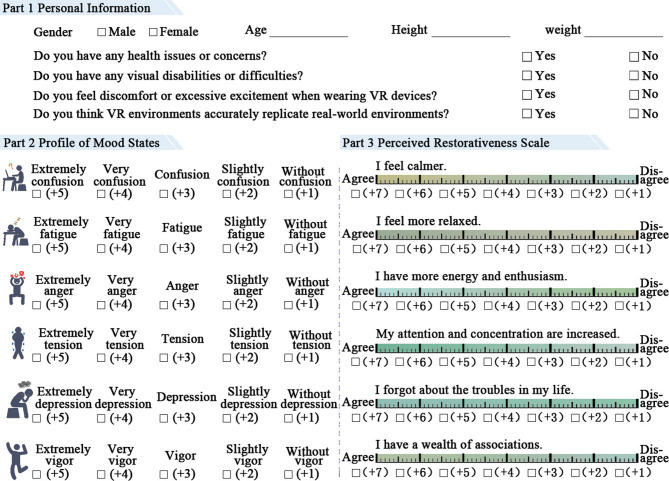

Psychological measures

The questionnaire survey in this study included three aspects: basic information, emotions, and visual preferences (see Fig. 5). Participants were required to complete a pre-experiment questionnaire collecting information on their height, weight, visual conditions, and potential sensitivity or discomfort related to VR. After each NW and different green wall exposure experiment, they completed the POMS and PRS. POMS is a method for evaluating emotional states40, using a 5-point Likert scale to assess both negative and positive emotions from six aspects: confusion (C), fatigue (F), anger (A), tension (T), depression (D), and vigor (V)41. Representative mood-related adjectives are used to facilitate the rapid assessment of an individual’s emotional state42. The emotional level was calculated as the difference between negative and positive emotion scores (see Eq. (1)). A decrease in POMS scores is indicative of improved emotional state. The PRS, grounded in restorative environment theory, includes six selected items rated by participants on a 7-point Likert scale. Calculated as the average of six individual items, the PRS score represents perceived restorative potential, with higher scores denoting stronger restorative perceptions31. After completing the three green wall exposure experiments, participants voted on their visual preferences (VPV) for CFW, WFW, and NFW. Visual preference was assessed by asking, “Which green wall do you like the most?” Participants ranked the different green walls based on their preference, with the highest rank = 3 and the lowest rank = 1.

Fig. 5.

The questionnaire survey.

|

1 |

EEG measures

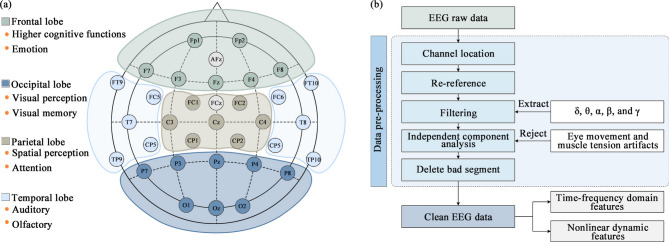

EEG were measured by the EPOC Flex Saline Sensor Kit (Emotiv Inc., USA), a portable 32-channel EEG device (sampling rate: 128 Hz, see Fig. 6(a)), with AFz and FCz serving as reference channels. Given the vulnerability of EEG signals to artifacts, preprocessing for noise reduction is essential before analysis. Figure 6(b) outlines the main steps: (1) Channel localization, matching EEG data to respective channels; (2) Re-referencing, typically using the common average reference; (3) Filtering, applying low-pass and high-pass filters to remove EEG signals outside the 1–45 Hz range; (4) Independent component analysis (ICA), to eliminate artifacts caused by eye movements, muscle tension, etc.; (5) Bad segment removal, discarding EEG signals of poor quality. If more than 50% of the EEG signal segments are of poor quality, they are excluded from subsequent analysis. The EEG signals of all 26 participants in this study met the inclusion criteria. EEG signals were segmented into epochs of 2 s with a 50% overlap. All preprocessing steps were completed using the EEGLAB toolbox in Matlab 2016b (Mathworks, USA).

Fig. 6.

(a) Channel distribution diagram of the device and (b) preprocessing framework.

Overall power

Overall power is a common frequency domain feature that reflects the intensity of brain oscillatory activity33. When the brain is stimulated by external factors, neuron interaction is activated, consuming more brain energy, which is associated with discomfort26,43. Conversely, when brain activity is in a comfortable state, the brain load is lower, and the overall power is also lower44,45. Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) was employed to convert EEG signals from the time domain to the frequency domain, the power spectral density (PSD) within the 1–45 Hz range is summed to obtain the overall power (see Eq. (2))46. Because absolute power values are typically large, a logarithmic transformation is commonly applied (see Eq. (3)).

|

2 |

|

3 |

Where, FFTn is the PSD extracted by FFT, i and j denote the minimum and maximum frequencies of EEG signal (1 and 45, respectively).

τe

The autocorrelation function (ACF) describes the degree of autocorrelation of EEG signals at different time lags, revealing patterns and periodic features in the brain activity time series47–49. ACF helps identify the intensity of specific frequency bands. α (8–13 Hz) oscillations often appear in a relaxed state, and if the α oscillatory activity contains obvious repeating patterns, the ACF will show distinct peaks at corresponding lag times24. The calculation method is shown in Eq. (4). The larger the effective delay time of α (τe), the longer the temporal correlation of the signal persists, which is associated with positive brain responses24.

|

4 |

Where, N is the length of the EEG series, x(t) is the signal value at time t,  is the mean value of the series, and τ is the time lag. The τe refers to the time it takes for the signal to decay from its peak back to the initial level.

is the mean value of the series, and τ is the time lag. The τe refers to the time it takes for the signal to decay from its peak back to the initial level.

Fuzzy entropy (FE)

Brain activity is nonlinear, and dynamic feature analysis can offer a more complete understanding. Entropy is a nonlinear metric used to quantify the level of disorder or complexity within a system. Compared to sample entropy and approximate entropy, fuzzy entropy (FE) uses a fuzzy function, making it more robust in handling complex and noisy EEG data. Studies have shown that FE can effectively reflect the probability of repeating patterns in the time series of EEG, as shown in Eqs. (5–6)25. The more stable the brain activity, the less power it consumes, which corresponds to a smaller FE50.

|

5 |

|

6 |

Where, m is the intrinsic dimension, here set as 2, r is the similarity threshold, set as 0.2-fold the SD of the original EEG data, and B represents the probability of self-similarity in m-dimensional patterns51.

Brain neural avalanche parameters

While the features mentioned above are typically used to characterize brain oscillations, the brain also demonstrates avalanche-like activity beyond these rhythmic patterns52. When the brain is subjected to stress stimuli, large-scale chaotic activities occur, whereas under positive stimuli (such as green wall interventions), high-amplitude bursts of neuronal activity help transition the brain’s disordered activity to periodic, stable activity. This pattern of neuronal activity is known as neural avalanches53. Avalanche size (AS), avalanche duration (AD), and branching parameters (σ) are commonly used to quantify the features of avalanche activity. First, it is necessary to detect whether avalanche activity occurs within a time window, defined as activity exceeding a threshold. The time window used here is 31.2 ms, which is 4-fold the temporal resolution of the EEG signal sampling rate (128 Hz). The threshold is set as the mean value of the total EEG signals plus the SD. Instances where brain activity surpasses the threshold are marked as events, and sequences of consecutive events are grouped into time bins. Subsequently, the duration of consecutive events and the total count of events within that time window are calculated, representing the avalanche duration and size, respectively. The distributions of AS and AD follow a power-law form, and their corresponding power-law exponents are denoted as λ₁ (for size) and λ₂ (for duration), respectively. These exponents were estimated using maximum likelihood estimation (MLE), as shown in Eqs. (7–8)54,55.

|

7 |

|

8 |

The branching parameter (σ) is a crucial feature describing the stability of neural avalanche activity. This measure reflects the average number of follow-up activations triggered by a preceding event within an avalanche (see Eq. (9))56,57. If σ < 1, the system tends to decay, meaning the number of subsequent events gradually decreases, and the avalanche tends to reduce or shrink. If σ = 1, the system is in a critical state, implying that the number of subsequent events remains constant, resulting in stable avalanches with balanced growth and decay rates. If σ > 1, the system is in an unstable state, where the number of subsequent events grows exponentially, causing the avalanche to expand or grow58. Stable avalanche dynamics are linked to enhanced recovery of the brain toward a comfortable or relaxed state59.

|

9 |

Where, ni is the count of events in the previous event box, ni+1 is the count of events in the following box, and N is the entire count of non-empty event boxes.

Analogous to the dynamics described by the Ising model60, where the magnetic field reaches a balance between order and disorder at a specific temperature, achieving the highest synergy between the magnet and the external magnetic field61, the brain’s neural avalanche activity also has a balance point. When this balance point is reached, the brain can quickly organize external information, and neuronal activity self-sustains to promote communication, maintaining a comfortable and healthy state. The avalanche critical index (ACI) is commonly used to reflect this critical state. A smaller ACI indicates that the brain is closer to the critical state62. Based on the power-law exponents of avalanche size (λ1) and avalanche duration (λ2), the calculated value (λ3) and the fitted value (λ4) of the average scale power-law exponent are obtained, with the difference between them representing ACI, as shown in Eqs. (10–12)54,55.

|

10 |

|

11 |

|

12 |

Data analysis

This study initially categorized the 78 data sets—derived from three green wall conditions for each of the 26 participants—based on VPV into three groups: low-preference (LP), medium-preference (MP), and high-preference (HP). To eliminate the effects of repeated measurements and better reflect the efficiency of brain activity recovery, the ratio of the measured value (Indexafter) to the baseline value (Indexbaseline) was calculated for subsequent analysis (see Eq. (13))63. The Shapiro-Wilk test was then conducted, revealing that the data from each group followed a normal distribution. For variables that followed a normal distribution, paired-sample t-tests were used to examine whether the psychological and physiological indicators changed significantly before and after the green wall intervention (see Appendix A1 for details). To account for the repeated measures design, a linear mixed-effects model (LMM) was further employed for one-way analysis of variance. In this model, green wall preference level (LP, MP, and HP) was treated as a fixed effect, and participants were included as a random intercept. The degrees of freedom were calculated using the Satterthwaite approximation method. The model tested whether the changes in psychophysiological responses (ΔPOMS, ΔPRS, Δoverall power, Δτe, ΔFE, and ΔACI) differed significantly across preference levels (see Appendix A2). P < 0.05 was considered indicative of a significant difference. Next, Spearman correlation analysis was performed to investigate the relationships between VPV, ΔPOMS, ΔPRS, and Δoverall power, Δτe, ΔFE, and ΔACI. Correlation strength was interpreted as follows: |r| = 0.10–0.39 indicating a weak correlation, 0.40–0.69 moderate, and 0.70–1.00 strong. Above analyses were conducted using SPSS 27.0 (SPSS Inc., USA). Finally, a green wall preference prediction model was developed based on brain activity features using various machine learning classifiers. In this study, five commonly used classification models were constructed: Decision Tree (DT), K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN), Naive Bayes (NB), Artificial Neural Network (ANN), and Random Forest (RF). Prior to modeling, all feature variables (e.g., Δoverall power, ΔACI, ΔFE, Δτe) were standardized using Z-score normalization to mitigate the influence of scale differences on model performance. To reduce feature redundancy and the risk of overfitting, feature selection was performed using the LASSO regression method, retaining only the features that contributed significantly to predictive performance. Model training and evaluation were conducted using five-fold cross-validation, and all evaluation metrics—accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score—represent the average results across folds. To avoid data leakage due to repeated measures, we adopted a leave-one-subject-out cross-validation scheme, ensuring that all data from a given participant appeared exclusively in either the training or validation set. The model specifications are as follows: DT: Constructed using the CART algorithm to generate a binary tree, with the Gini index as the splitting criterion; maximum tree depth was 5, and the minimum number of samples per leaf node was 3. KNN: The number of neighbors k was set to 5, with Euclidean distance used as the distance metric. NB: Gaussian Naive Bayes was used, assuming that the input features follow a Gaussian distribution. ANN: A three-layer feedforward neural network was implemented. The input layer contained nodes equal to the number of selected features, followed by a hidden layer with 8 nodes using ReLU activation, and an output layer with Softmax activation. The model was optimized using the Adam optimizer, and the loss function was categorical cross-entropy. RF: Consisted of 100 decision trees with a maximum depth of 10. For each split, √n features were randomly selected. Model accuracy was estimated using the Out-of-Bag score. All models were implemented using the Scikit-learn library in Python 3.9. The EEG data and code are available at https://github.com/zhangnan916/Green-wall-data.git.

|

13 |

Results

Visual preference vote

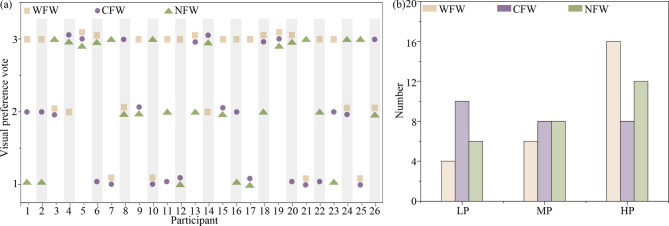

Figure 7(a) shows the results of visual preference vote (VPV). Individual differences exist in VPV for green walls with different tones. Among WFW, CFW, and NFW, 10 participants preferred WFW, 6 participants preferred NFW, 2 participants preferred CFW, and 2 participants found all three green walls to provide equally good visual perception. Interestingly, participants 4 and 14 preferred CFW and NFW, while participants 6 and 20 preferred WFW and NFW, and participants 13 and 18 had a higher preference for CFW and WFW compared to NFW. This indicates that different green walls have varying effects on individual visual perception. Based on VPV of the 26 participants for the three green walls, the 78 data sets were divided into three groups (as shown in Fig. 7(b)), namely the low-preference group (LP, VPV = 1), the medium-preference group (MP, VPV = 2), and the high-preference group (HP, VPV = 3). Most participants rated WFW and NFW highly, leading to 46.15% of the data falling into the high preference group. The LP and the MP groups included 20 and 22 data sets, respectively.

Fig. 7.

(a) Visual preference votes (VPV) for three green wall types—warm-colored flowered (WFW), cool-colored flowered (CFW), and non-flowered (NW)—by each participant. (b) Distribution of green wall types across low- (LP), medium- (MP), and high-preference (HP) groups. Results show clear individual differences in visual preference composition.

POMS and PRS

Paired t-tests indicated that positive emotions and perception recovery significantly improved after any green wall intervention compared to the baseline (p < 0.001, see Appendix A1). The HP group showed the best performance, with POMS significantly decreasing by 2.82 (p < 0.001, see Appendix A3) and PRS significantly increasing by 2.19 (p < 0.001, see Appendix A5), indicating the greatest enhancement in psychological response. Figure 8(a) presents the effect of green walls with varying preference levels on ΔPOMS After the green wall intervention, ΔPOMS was less than 0, indicating a significant improvement in overall mood compared to the NW. As green wall preference increased, the reduction in POMS also significantly increased (p < 0.001, see Appendix A2). The fixed effects explained 32% of the variance, while including individual differences increased the overall explained variance to 56%. Notably, the ΔPOMS of the HP group was 1.11–1.25 times greater than that of the other two groups (see Appendix A4). Figure 8(b) shows the impact of varying preference green walls on ΔPRS. After the green wall intervention, ΔPRS ranged from 0.37 to 0.77, indicating significant subjective stress recovery improvement compared to the NW. ΔPRS significantly increased with higher green wall preference, showing statistical differences (p < 0.001, see Appendix A2). The PRS increase in the HP group was 1.28 times that of the LP group (p = 0.006, see Appendix A6) and 2.10 times that of the MP group. Overall, WFW, CFW, and NFW all helped to eliminate negative emotions and psychological stress4, and this positive effect increased with higher green wall preference.

Fig. 8.

(a) Changes in Profile of Mood States (ΔPOMS) and (b) Perceived Restorativeness Scale (ΔPRS) across high- (HP), medium- (MP), and low-preference (LP) groups. Boxplots show that higher visual preference is associated with greater emotional improvement and perceived restoration. The effect of green wall preference on the ΔPOMS and ΔPRS was significant (p < 0.001).

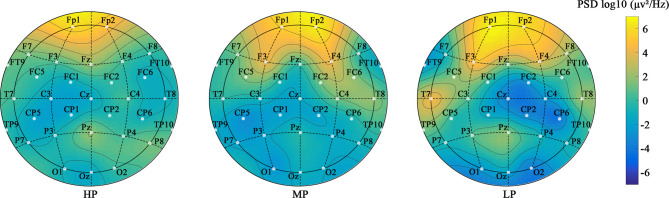

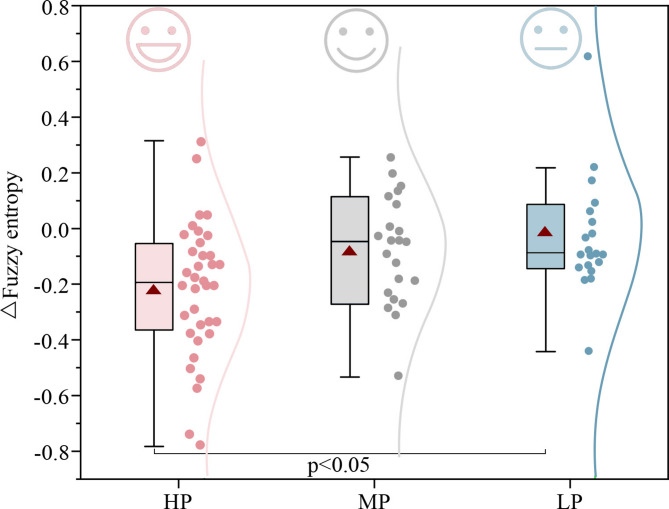

Overall power

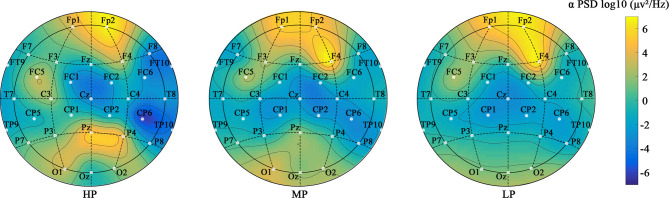

Figure 9 shows the plots of overall brain activity for different preference groups. As preferences increase, the color in the plots gradually fades, indicating a decrease in oscillatory activity. Changes in oscillatory activity are more significant in the right hemisphere, especially in the parietal lobe (area between Cz, CP2, CP6, C4, and FC2). Reduced oscillatory activity in the right hemisphere, which is associated with negative emotions, indicates a reduction in negative emotions64. The parietal lobe, related to complex thinking, shows decreased activity under high-preference green wall intervention, indicating restored top-down attention. Additionally, compared to the LP group, the HP group showed significantly reduced oscillatory activity in the T7 and F3 channels. While the temporal lobe primarily processes auditory information, it also plays a role in visual activities through a synergistic effect. Previous studies have also identified the frontal lobe as a key region reflecting emotional changes65.

Fig. 9.

The plots of overall power for different preference groups.

Paired t-tests showed that, compared to NW, exposure to WFW, CFW, and NFW significantly reduced overall power by 2.14 µv² (p < 0.001, see Appendix A1), indicating that brain activity tended towards a comfortable state. This change was related to green wall preference, with high-preference green wall exposure significantly reducing overall power by 2.89µv² compared to the baseline condition (p < 0.001, see Appendix A7), which is 1.45–2.18 times greater than other preference green walls. As shown in Fig. 10, Δoverall power also indicated significant differences between different preference groups (p < 0.001, see Appendix A2). Individual differences increased the overall explained variance by 20%. Although the Δoverall power for different preference green walls ranged from − 0.08 to -0.24, indicating that brain activity was relaxed in all cases, the Δoverall power for the HP group was 1.39–2.96 times that of the LP and MP groups (see Appendix A8), effectively reducing unnecessary brain power consumption and more prominently promoting brain comfort. This demonstrates that green wall exposure helps reduce brain stress levels, with high-preference green walls performing better4,19.

Fig. 10.

Changes in overall EEG power (Δoverall power) across high- (HP), medium- (MP), and low-preference (LP) groups. Lower visual preference was associated with greater increases in EEG power. The effect of green wall preference on the Δoverall power was significant (p < 0.001).

τe

Figure 11 shows the plots of α oscillatory activity for different preference groups. As preferences increase, the plot’s color gradually deepens, indicating enhanced α oscillatory activity, especially in the right hemisphere. Enhanced α oscillatory activity in the right hemisphere is associated with better stress recovery66. Compared to the LP group, the HP group exhibited significantly increased α oscillatory activity in the frontal-parietal (FC1, FC2, and Cz), parietal-temporal (CP6 and TP10), frontal-temporal (F8 and FT10), and posterior parietal (Pz and P4) regions. High-preference green walls increased the connectivity of α oscillatory activity across various regions of the right hemisphere, resulting in more positive emotions.

Fig. 11.

The plots of α oscillatory activity for different preference groups.

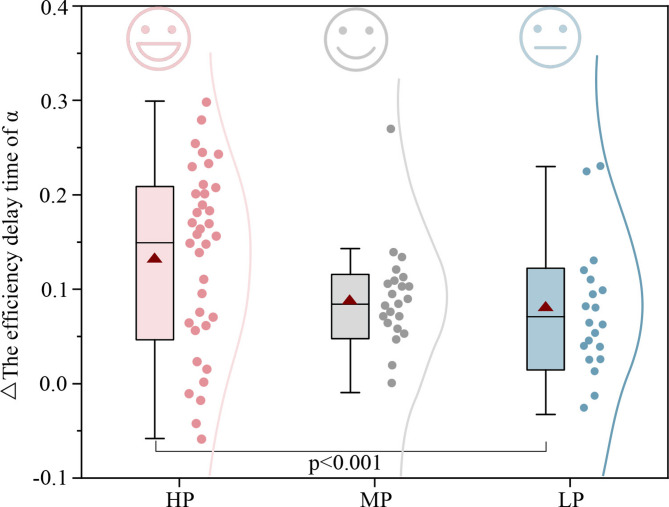

The τe significantly increased after exposure to different green walls (p < 0.001, see Appendix A1). Compared to NW, τe significantly increased by 34.52 ms, 24.48 ms, and 21.00 ms for HP, MP, and LP groups, respectively (p < 0.05, see Appendix A9). Green walls activate α oscillations. As shown in Fig. 12, the Δτe increased by 0.04–0.05 more under high-preference green wall exposure compared to low-preference and medium-preference, promoting the increase in the autocorrelation of α oscillatory activity (see Appendices 2 and 10). This indicates that high-preference green walls help improve the periodicity and intensity of α oscillatory activity4.

Fig. 12.

Changes in the effective delay time of alpha oscillations (Δτe) across high- (HP), medium- (MP), and low-preference (LP) groups. Higher visual preference was associated with longer α delay time, indicating more sustained neural processing. Group differences were significant (p < 0.001).

Fuzzy entropy (FE)

Green wall exposure helps prevent the brain from developing irrelevant new patterns, thereby reducing fuzzy entropy (FE). Compared to NW, FE significantly decreased by 0.84 after exposure to different green walls (p = 0.005, see Appendix A1), particularly in the HP group, where FE significantly decreased by 1.44 (p = 0.002, see Appendix A11). As shown in Fig. 13, green wall preference had a substantial impact on ΔFE (p = 0.027, Marginal R2 = 0.22, Conditional R2 = 0.38, see Appendix A2). Under high-preference and medium-preference green wall exposures, ΔFE was − 0.22 and − 0.09, respectively, while low-preference green wall exposure did not result in a significant change in FE (ΔFE = -0.01). The HP and LP groups showed statistically significant differences (p = 0.047, see Appendix A12). These findings indicate that the modulation of brain activity complexity by green walls is associated with individual visual preferences.

Fig. 13.

Changes in fuzzy entropy (ΔFE) across high- (HP), medium- (MP), and low-preference (LP) groups. Lower visual preference was associated with higher increases in EEG complexity. The effect of green wall preference on the ΔFE was significant (p < 0.05).

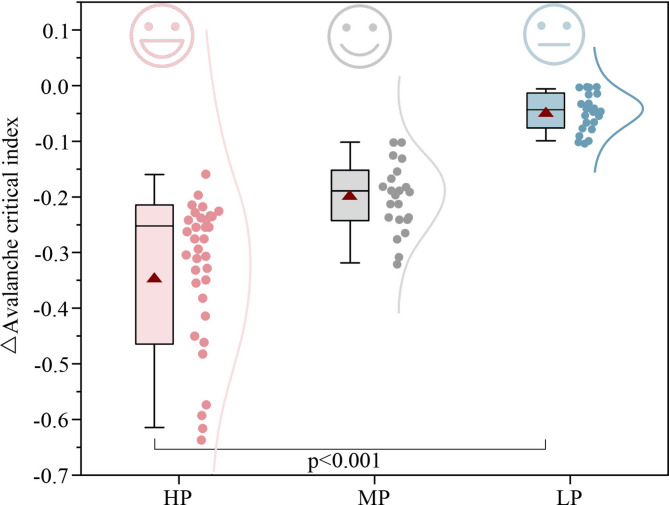

Avalanche activity

Figure 14 shows the avalanche sizes under different preference green wall exposures. Compared to low-preference green walls, high-preference and medium-preference green walls exhibited a lower probability of large-scale avalanche activities. The λ₁ values were 1.51 and 1.52, respectively, which are closer to the theoretical value of 1.5061. Smaller avalanche activities tend to propagate faster, facilitating the brain’s recovery to an optimal state67.

Fig. 14.

Power-law distributions of avalanche size (AS) for high- (HP), medium- (MP), and low-preference (LP) groups. The fitted exponents indicate reduced large-scale neural cascades in the LP group, suggesting diminished criticality under less preferred green wall exposure.

Figure 15 shows the avalanche durations under different preference green wall exposures. The probability of prolonged avalanche activities in the brain was lowest under high-preference green wall exposure (λ2 = 1.92), closest to the theoretical value of 2.061, while the probability was highest under low-preference green wall exposure (λ2 = 1.75). The smaller the time difference between the first and last activation of neurons, the higher the efficiency of slowing down brain neural dynamics, which aids in stress recovery53.

Fig. 15.

Probability distributions of avalanche duration (AD) fitted with power-law functions for the high- (HP), medium- (MP), and low-preference (LP) groups. The exponents indicate heavier-tailed distributions in the HP group, suggesting more stable and sustained neural cascades during preferred green wall exposure.

To further explore how green walls with different levels of visual preference influence brain avalanche dynamics, the study examined individual variations in the power-law exponents of AS (λ₁) and AD (λ₂), as illustrated in Fig. 16(a). The distributions of λ1 and λ2 show an approximately linear pattern on the coordinate plane. Taking the mean values from the medium-preference group (λ1 = 1.51, λ2 = 1.78) as a central reference point, the plane was divided into four quadrants. Most data points from the high-preference group are concentrated in the upper right quadrant relative to this center. This region is characterized by reduced brain resource wastage and better cognitive ability to integrate and process external information, which can be considered a low power consumption zone. In this zone, 69.44% of the HP group participants were located (as shown in Fig. 16(b)). Conversely, 50.00% of the LP group participants were concentrated in the lower left quadrant, characterized by widespread and sustained neural instability, which imposes significant metabolic demands on the nervous system. The results suggest an association between green wall exposure and avalanche dynamics under different levels of visual preference. Specifically, exposure to highly preferred green walls was associated with more energy-efficient and stable brain activity patterns, which may reflect a higher level of cortical comfort.

Fig. 16.

(a) Scatter plot of avalanche size (λ₁) and duration (λ₂) power-law exponents, divided into low and high power consumption zones. (b) Distribution of participants from high-preference (HP) and low-preference (LP) groups across the zones. HP participants were predominantly located in the low-power consumption zone, indicating more efficient neural activation.

The branching parameter (σ) reflects the propagation features of avalanches. As shown in Fig. 17, σ was greater than 1.00 under all green wall exposures, indicating that brain avalanche activity was diffusively propagated. However, compared to low-preference green walls, σ decreased by 0.04–0.05 under high-preference and medium-preference green wall exposures, bringing it closer to the theoretical value of 1.00. This suggests that brain avalanche activity had a more balanced growth and decay rate. Differences in avalanche propagation patterns were observed under green wall exposures with varying levels of preference. Under high-preference green wall exposure, the σ value was closer to the critical point, which may be associated with enhanced neural efficiency and the brain’s improved capacity for comfort-related recovery.

Fig. 17.

Branching parameter (σ) across high- (HP), medium- (MP), and low-preference (LP) groups. No significant group difference was found, although all values remained above the critical threshold (σ = 1), indicating a supercritical state of brain dynamics during green wall exposure.

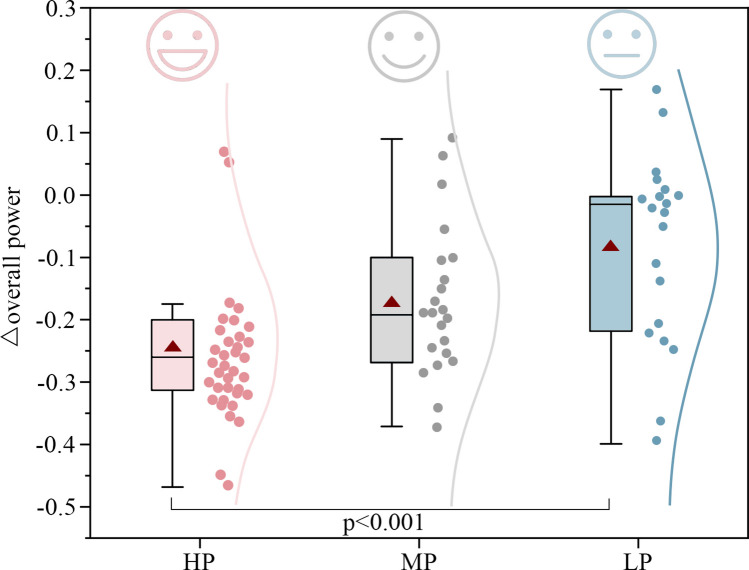

Paired t-tests indicated that, compared to NW, the ACI significantly decreased after exposure to WFW, CFW, and NFW (p < 0.001, see Appendix A1). The ACI decreased by 0.14, 0.06, and 0.01 for HP, MP, and LP groups, respectively (p < 0.01, see Appendix A13). Significant group differences in ΔACI were also observed, as shown in Fig. 18 (p < 0.001, see Appendix A2). The fixed effects explained 34% of the variance, while including individual differences increased the overall explained variance to 59%. High-preference green walls performed best, with the largest decrease in ACI (ΔACI = -0.35), and some individuals even reached around − 0.60. Compared to medium- and low-preference conditions, the high-preference green wall exposure resulted in a greater reduction in ACI (15.09–30.31%, p < 0.05, see Appendix A14). This finding suggests that high-preference exposure may be associated with brain activity patterns that are closer to the critical state. This indicates that as green wall preference increases, the decrease in ACI increases, allowing brain activity to approach a comfortable and positive critical state more quickly.

Fig. 18.

Changes in avalanche criticality index (ΔACI) across high- (HP), medium- (MP), and low-preference (LP) groups. Higher visual preference was associated with greater reductions in criticality, suggesting a more relaxed brain state. The effect of green wall preference on the ΔACI was significant (p < 0.001).

Correlation analysis

Figure 19 shows the correlation between subjective evaluations and brain activity. As VPV increases, ΔPOMS decreases, while ΔPRS increases, with r values of -0.620 and 0.905, respectively (p < 0.001). This indicates that higher green wall preferences are associated with improvements in negative emotions and stress levels. Additionally, a significant negative correlation was found between VPV and Δoverall power, ΔFE, and ΔACI (p < 0.05). Interestingly, there is also a significant positive correlation between Δoverall power and ΔACI, with an r value of 0.390 (p < 0.01). This supports previous research findings26, suggesting that approaching a critical state is associated with lower brain power consumption. Thus, subjective perception under green wall exposure is closely related to brain activity, with high-preference green walls often leading to more positive psychophysiological restoration4.

Fig. 19.

The correlation between subjective evaluations and brain activity.

Individual green wall preference prediction model based on brain activity features

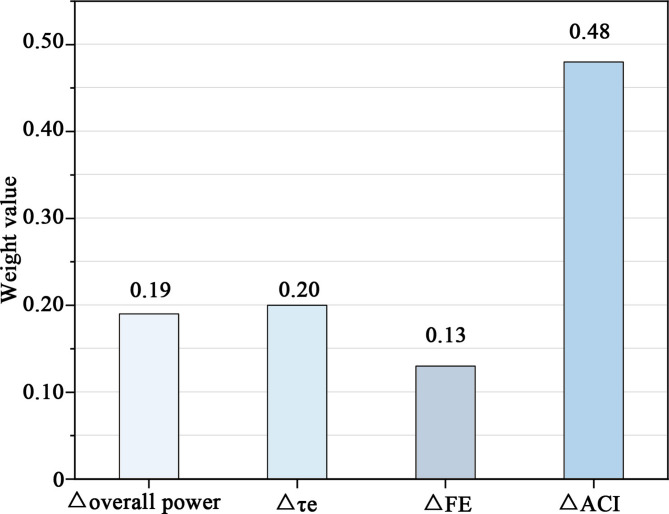

The study also evaluated the classification accuracy of various models trained on brain activity features to identify green wall preferences, as shown in Table 3. Using DT, KNN, NB, ANN, and RF classifiers, all effectively identified green wall preferences, with accuracies ranging from 0.61 to 0.88. The RF performed the best, achieving the highest accuracy of 0.88. The model parameters for the RF were set as follows: the criterion for node splitting was gini, the minimum samples for splitting a node and for leaf nodes were 2 and 1, respectively, the maximum number of features was set to auto, and bootstrapping with out-of-bag samples for testing was used. Among these brain activity features, ΔACI was the most important predictor of VPV (w = 0.48), as shown in Fig. 20. This indicates that Δoverall power, Δτe, ΔFE, and ΔACI can effectively identify green wall preferences, with the random forest classifier showing the best performance.

Table 3.

Performance of different prediction models.

| Model | Item | Accuracy | Recall rate | f1-score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DT | LP | 1.00 | 0.70 | 0.82 |

| MP | 0.67 | 1.00 | 0.80 | |

| HP | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Average | 0.91 | 0.87 | 0.87 | |

| KNN | LP | 1.00 | 0.57 | 0.73 |

| MP | 0.50 | 0.75 | 0.60 | |

| HP | 0.83 | 1.00 | 0.91 | |

| Average | 0.82 | 0.75 | 0.75 | |

| NB | LP | 1.00 | 0.71 | 0.83 |

| MP | 0.60 | 0.75 | 0.67 | |

| HP | 0.50 | 0.60 | 0.55 | |

| Average | 0.74 | 0.69 | 0.70 | |

| ANN | LP | 1.00 | 0.57 | 0.73 |

| MP | 1.00 | 0.25 | 0.40 | |

| HP | 0.45 | 1.00 | 0.63 | |

| Average | 0.83 | 0.63 | 0.61 | |

| RF | LP | 1.00 | 0.71 | 0.83 |

| MP | 0.67 | 1.00 | 0.80 | |

| HP | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Average | 0.92 | 0.88 | 0.88 |

Fig. 20.

The weight value of EEG features.

Discussion

Positive effects of indoor green wall on Psychophysiological restoration

The visual connection with indoor green walls contributes to psychophysiological restoration. Kaplan’s ART68 and Ulrich’s SRT69 support this viewpoint. According to ART70, attention can be passively restored in natural environments through subconscious cognitive mechanisms. Unlike urban environments that impose continuous stress, nature elicits relaxation and enjoyment with minimal attentional effort71. Indoor green walls foster a sense of connection to nature through bottom-up processing, which occurs without the need for directed attention and supports restorative outcomes. SRT72 suggests that nature is viewed as a low-threat environment, leading to reduced activation of stress-related physiological responses. Indoor green walls contribute to stress recovery by providing a sense of safety, structure, and an environment free from perceived threats73. The study found that compared to no green wall, POMS decreased by 2.59 and PRS increased by 1.68 after green wall exposure, significantly improving emotional disturbance and psychological stress. Physiologically, the visual stimuli from green walls contributed to brain activity indicative of relaxation and stress recovery. The brain’s limbic system, including structures such as the hippocampus and amygdala, is involved in the emotional processing of visual stimuli from indoor green walls. By eliciting naturalistic associations, these stimuli can play a role in mitigating physiological stress responses4,19. The study found that compared to no green wall, brain oscillatory activity tended towards stability and comfort after green wall exposure, with overall power decreasing by 2.14 µv², FE decreasing by 0.84, and α oscillatory activity, associated with relaxation, significantly increasing. Additionally, τe increased by 28.22 ms, and brain avalanche activities exhibited short-duration, small-scale patterns, closer to the critical state, with ACI decreasing by 0.09. In summary, the comprehensive effects of psychophysiological mechanisms make indoor green walls an effective restorative measure, providing a strong reference for improving indoor environmental quality.

Visual preferences make a difference in improving psychophysiological restoration with green walls

Green therapy and color therapy support the positive effects of different colored green walls on psychophysiological health, but studies indicate that individuals have varying color preferences8. Hůla and Flegr74 found that purple is more popular than yellow, whereas Zhang et al.8 concluded the opposite. Elsadek and Fujii75 found that purely green plants promote greater relaxation than those with mixed green-red or green-white foliage. Additionally, Kexiu et al.76 found that Japanese people prefer green and green-white mixed plants, while Egyptians prefer light green and yellow-green plants. These findings highlight significant individual differences in visual preferences for different colored greenery, which this study also supports. From VPV, 10 participants preferred WFW, 6 preferred NFW, 2 preferred CFW, 2 preferred both CFW and WFW, 2 preferred both CFW and NFW, 2 preferred both WFW and NFW, and 2 found all three green walls to provide equally good visual perception. Warm-colored flowers can evoke strong, uplifting emotions; thus, WFW is invigorating and stimulating, helping to combat psychological health issues9. Haviland-Jones et al.77 and Hoyle et al.78 noted that flowers attract more visual attention. Green walls with flowers may be more beneficial for mental health compared to those with only leaves. More complex green walls tend to attract longer attention and have more significant restorative effects. However, the impact can vary among individuals, potentially bringing either negative or positive effects, which still requires further exploration9.

Research generally agrees that warm colors are invigorating, while cool colors are relaxing. Zhang et al.8 found that cool-toned flowers, such as purple and blue, help with relaxation and stress recovery, while warm-toned flowers, such as yellow and red, evoke more excitement and positive emotions. Neale et al.79 found similar results in a cross-cultural study. However, Stigsdotter and Grahn80 pointed out that in the early stages of recovery, calming cool colors might be important, while later on, bright warm colors play a more significant role in improving positive emotions. Therefore, more scholars believe that regardless of the inherent properties of color, an individual’s preference for that color is decisive for psychophysiological responses. Brengman et al.81 and Manav et al.82 observed that if a person’s favorite color is warm, warm-colored flowers, despite being thought to activate exciting emotions, still promote relaxation. As noted by Kuper et al.83, emotional experiences elicited by green walls are strongly shaped by subjective color preferences. This study found that compared to the LP and MP groups, the HP group had the lowest POMS (0.47) and the highest PRS (5.35) after green wall exposure. As preference increased, the reductions in overall power and FE after green wall exposure also increased (-2.89 to -0.91, -1.44 to -0.07), and Δτe gradually increased (21.00 to 34.52 ms), indicating more positive brain oscillatory activity in the HP group. During green wall exposure in the HP group, faster avalanche propagation and a power-law exponent (λ₂ = 1.92) closer to the theoretical critical value were observed, along with the lowest ACI (0.19). These results suggest that brain activity under this condition may be closer to the critical state, which is considered optimal for comfort and healthy functioning. Environmental preference is the emotional expression of an individual’s innate preference for a particular type of environment, influenced by individual differences. Kaplan et al. believed that environmental preference has a significant positive impact on environmental restorative evaluation16,70 because environments that individuals prefer are more likely to meet their needs, fostering a strong desire to immerse themselves in them. Experiences with preferred green walls are more likely to develop a strong emotional connection with the individual, enhancing identification and leading to restorative and pleasant experiences. Berto et al.84 pointed out that less attention is consumed in highly preferred environments compared to less preferred ones. When individuals interact with a biophilic environment that matches their natural affinity, they perceive the environment’s restorative quality as higher85,86. The results showed significant correlations between VPV and both ΔPOMS (r = -0.620) and ΔPRS (r = 0.905) at the p < 0.001 level. Additionally, VPV was negatively associated with Δoverall power, ΔFE, and ΔACI (p < 0.05). Overall, higher preference for indoor green walls leads to more positive psychophysiological responses.

The relationship between individual preferences for green walls and their psychophysiological impacts is complex87. On one hand, personality and emotions are essential components of individual features; while personality is generally stable, emotions are cyclical and can influence personal preferences88. On the other hand, the psychophysiological effects of green walls are complex, with the size and color of the green wall playing crucial roles in this process. Visual perception complexity is an important factor affecting preference; if the perceived complexity is too high, individuals may feel overwhelmed, whereas if it is too low, they may feel monotony. Solely relying on subjective evaluations to assess green wall preferences can be inaccurate and inefficient. To better evaluate green wall preferences, this study proposed a machine learning model based on brain activity features (Δoverall power, Δτe, ΔFE, and ΔACI). Comparing five classifiers—DT, KNN, NB, ANN, and RF—it was found that RF performed the best, achieving the highest accuracy (0.88), providing strong support for the personalized design of indoor green walls. In summary, green walls that are highly preferred exert a greater positive effect on psychophysiological well-being. Interior designers should offer opportunities for individuals to engage with green walls of different colors based on personal preferences to meet emotional needs at different times and cater to various individual preferences.

Limitations and future directions

This study provides a method combining EEG, VR, and LEC to investigate how green walls affect psychophysiological health. It confirms the potential of immersive virtual environments combined with green walls in psychophysiological stress recovery. Future research can extend this approach to indoor environments beyond offices, such as hospitals, classrooms, and underground spaces. The study also demonstrates that preferences influence the restorative benefits of green walls, independent of the inherent properties of the green wall colors. Therefore, it is necessary to provide personalized green wall interventions tailored to individual preferences in future applications.

However, this study has some limitations. The focus on university students, who spend long periods indoors and sedentary, may result in different psychophysiological responses compared to other populations (varying in age, occupation, etc.). Future research should explore brain activity features under green wall exposure in diverse populations to enhance the generalizability of the findings. Although we accounted for gender differences by setting a 1:1 gender ratio, the differences in visual preferences and brain activity between males and females were not further discussed, which warrants further investigation. In this study, a simplified version of the POMS was used for emotional assessment, wherein only a subset of representative mood adjectives was selected for subjective rating. This approach aimed to reduce participant burden during the experiment and minimize potential interference with continuous physiological measurements. However, this simplification may have limited the comprehensive characterization of emotional changes, particularly in dimensions such as tension, anger, and depression. Future studies are encouraged to employ the full version of the POMS to enhance the comprehensiveness and reliability of emotional assessments. This study primarily focused on three types of green walls; however, in everyday life, plants exhibit diverse colors, aromatic properties, and visual features. Future studies should measure the impact of a wider variety of colors, scents, and plant forms on visual preferences and brain activity. Although the IPQ questionnaire confirmed the immersive quality and perceived realism of the VR environment, the virtual green wall setting cannot fully replicate real-world conditions. In practice, the restorative effects of green walls may also be influenced by additional multisensory factors such as scent, temperature, humidity, and air movement. Therefore, psychophysiological responses in VR may differ from those in actual green wall environments, warranting further investigation through on-site studies. This study offers novel perspectives on the link between visual preference and neural activity. However, as the research was correlational in nature, it does not allow for definitive conclusions regarding the causal effects of preference level on brain function. Future research should consider experimental or longitudinal designs to further examine the mechanistic impact of preference shifts on neural recovery efficiency. In addition, it should be noted that avalanche-based EEG measures, while offering valuable insights into the nonlinear dynamics of brain activity, are still relatively novel and complex. Therefore, their interpretation should be made with caution, and further replication studies are warranted to validate these findings.

Conclusion

This study recruited 26 young university students to explore the effects of cool-colored flower combined green wall (CFW), warm-colored flower combined green wall (WFW), and non-flower combined green wall (NFW) on subjective perception and brain activity. Previous research has indicated that the psychophysiological responses to plant colors are related to individual preferences. This study also found significant individual differences in visual preferences for WFW, CFW, and NFW. To further investigate the mechanisms by which green wall preferences influence psychophysiological restoration, all data were grouped according to visual preference vote (VPV) scores into high preference (HP), medium preference (MP), and low preference (LP) groups. The study utilized frequency domain and nonlinear dynamic features of electroencephalogram (EEG) signals to highlight variations in brain activity under exposure to green walls with different visual preferences and constructed a prediction model. The key conclusions are as follows:

After any green wall intervention, positive emotions and perception recovery significantly improved. The HP group showed the best performance, with profile of mood states (POMS) significantly decreasing by 2.82 (p < 0.001) and perceived restorativeness scale (PRS) significantly increasing by 2.19 (p < 0.001). The ΔPOMS and ΔPRS were 1.11–1.25 times and 1.28–2.10 times greater, respectively, compared to the LP and MP groups.

Compared to NW, green wall exposure significantly reduced overall power by 2.14 µv² (p < 0.001), indicating a decrease in brain stress levels. The Δoverall power in the HP group was 1.39–2.96 times greater than in the LP and MP groups, showing stronger regularity in brain oscillatory activity. Green wall exposure also contributed to an increase in the effective delay time of α (τe, 21.00-34.52 ms). The Δτe in the HP group increased by 0.04–0.05 more than in the LP and MP groups, better activating the α oscillatory activity associated with relaxation. During this period, fuzzy entropy (FE) significantly decreased by 1.44 compared to NW (p = 0.002), with ΔFE at -0.22, indicating that brain activity tended towards stability, comfort, and health.

High-preference green wall exposure induced smaller and faster avalanche activities, with λ1 and λ2 values of 1.52 and 1.92, respectively. During this time, branching parameter (σ) was closer to 1.00 (1.13), indicating more stable avalanche activity. This may be associated with the brain’s more efficient integration of information and its progression toward a stress recovery state. Compared to the MP group, 69.44% of participants in the HP group experienced reduced brain resource wastage and higher brain comfort. Under high-preference green wall exposure, the ACI exhibited a greater range of change (15.09–30.31%), which may reflect brain activity approaching the critical state between order and disorder.

Visual preferences significantly affect psychophysiological responses before and after green wall exposure. VPV was moderately negatively correlated with ΔPOMS (r = -0.620, p < 0.001) and strongly positively correlated with ΔPRS (r = 0.905, p < 0.001). VPV was also significantly negatively correlated with Δoverall power, ΔFE, and ΔACI (p < 0.05). High-preference green walls tend to bring about more positive psychophysiological responses.

Training Decision Tree (DT), K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN), Naive Bayes (NB), Artificial Neural Network (ANN), and Random Forest (RF) classifiers using the frequency domain and nonlinear dynamic features of EEG signals can effectively identify green wall preferences, with accuracies ranging from 0.61 to 0.88. Among these, the RF performed the best, with ΔACI being the most important predictor of VPV (w = 0.48).

This study provides strong evidence from the perspective of neuroarchitecture for the practice of indoor biophilic design, offering a reference for enhancing indoor environmental quality and improving human well-being.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by Innovation Institute for Sustainable Maritime Architecture Research and Technology. We also glad to give our special thanks to all participants.

Abbreviations

- ACF

Autocorrelation function

- AD

Avalanche duration

- AS

Avalanche size

- CFW

Cool-colored Flower Combined Green Wall

- EEG

Electroencephalogram

- FFT

Fast Fourier Transform

- KNN

K-Nearest Neighbors

- LP

Low- Preference

- NB

Naïve Bayes

- NW

Non-green Wall

- PRS

Perceived Restorativeness Scale

- RF

Random Forest

- SVM

Support vector machine

- VPV

Visual preference vote

- WFW

Warm-colored Flower Combined Green Wall

- σ

Branching parameter

- ACI

Avalanche criticality index

- ANN

Artificial neural network

- ART

Attention restoration theory

- DT

Decision tree

- FE

Fuzzy entropy

- HP

High-preference

- LEC

Laboratory environment control

- MP

Medium-preference

- NFW

Non-flower Combined Green Wall

- POMS

Profile of mood states

- PSD

Power spectral density

- SD

Standard deviation

- SRT

Stress recovery theory

- VR

Virtual reality

- α

Alpha brainwave (8–13 Hz) is linked to relaxation

- τe

The effective delay time of α

Author contributions

Conceptualization, M.M.W., N.Z. and L.Y.; methodology, L.Y.; software, N.Z.; validation, N.Z. and L.Y.; formal analysis, N.Z.; investigation, N.Z.; resources, N.Z.; data curation, N.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, N.Z.; writing—revise, review and editing, M.M.W.; visualization, N.Z.; supervision, M.M.W.; project administration, W.J.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Data availability

The data and code are available at https://github.com/zhangnan916/Green-wall-data.git.

Code Availability

The data and code are available at https://github.com/zhangnan916/Green-wall-data.git.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Informed consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the participant for the publication of the image in this online open access article.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Zhong, T. & Meng, X. Effect of air temperature in indoor transition spaces on the thermal response of occupant during summer. Sci. Rep.15, 919 (2025). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wen, J., Sun, J. & Meng, X. Effect of window orientation on the thermal performance of electrochromic glass. Case Stud. Therm. Eng69, 563 (2025).

- 3.Yin, J. et al. Effects of biophilic indoor environment on stress and anxiety recovery: a between-subjects experiment in virtual reality. Environ. Int.136, 105427 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yeom, S., Kim, H. & Hong, T. Psychological and physiological effects of a green wall on occupants: a cross-over study in virtual reality. Build. Environ.2021 204 (2021).

- 5.Paull, N. J., Irga, P. J. & Torpy, F. R. Active green wall plant health tolerance to diesel smoke exposure. Environ. Pollut. 240, 448–456 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pettit, T., Irga, P. J., Abdo, P. & Torpy, F. R. Do the plants in functional green walls contribute to their ability to filter particulate matter? Build. Environ.125, 299–307 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Latini, A. et al. Effects of biophilic design interventions on university students’ cognitive performance: an audio-visual experimental study in an immersive virtual office environment. Build. Environ.2024, 250 (2024).

- 8.Zhang, L., Dempsey, N. & Cameron, R. Flowers – sunshine for the soul! How does floral colour influence preference, feelings of relaxation and positive up-lift? Urban Urban Green2023, 79 (2023).

- 9.Zhang, L., Dempsey, N. & Cameron, R. ‘Blossom buddies’ – how do flower colour combinations affect emotional response and influence therapeutic landscape design? Landsc. Urban Plan.2024, 248 (2024).

- 10.Berger, B. G. & Motl, R. W. Exercise and mood: a selective review and synthesis of research employing the profile of mood States. J. Appl. Sport Psychol.12, 69–92 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rogerson, M., Gladwell, V. F., Gallagher, D. J. & Barton, J. L. Influences of green outdoors versus indoors environmental settings on psychological and social outcomes of controlled exercise. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 13, 363 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rhee, J. H., Schermer, B. & Lee, K. H. Effects of the nature connectedness on restoration in simulated indoor natural environments. Build. Environ.2024, 258 (2024).

- 13.Rhee, J. H., Schermer, B. & Cha, S. H. Effects of indoor vegetation density on human well-being for a healthy built environment. Dev. Built Environ.14, 100172 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Berman, M. G., Jonides, J. & Kaplan, S. The cognitive benefits of interacting with nature. Psychol. Sci.19, 1207–1212 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Basu, A., Duvall, J. & Kaplan, R. S. W. Attention restoration theory: exploring the role of soft fascination and mental bandwidth. Environ. Behav.51, 1055–1081 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaplan Mintz, K., Ayalon, O., Eshet, T. & Nathan, O. The influence of social context and activity on the emotional well-being of forest visitors: a field study. J. Environ. Psychol.94, 256 (2024).

- 17.Lohr, V. I., Pearson-Mims, C. H. & Goodwin, G. K. Interior plants May improve worker productivity and reduce stress in a windowless environment. J. Environ. Hortic.14, 97–100 (1996). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ikei, H., Song, C., Igarashi, M., Namekawa, T. & Miyazaki, Y. Physiological and psychological relaxing effects of visual stimulation with foliage plants in high school students. Adv. Hortic. Sci.28, 111–116 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ma, X., Du, M., Deng, P., Zhou, T. & Hong, B. Effects of green walls on thermal perception and cognitive performance: an indoor study. Build. Environ.2024 250 (2024).

- 20.Sedghikhanshir, A., Zhu, Y., Beck, M. R. & Jafari, A. Exploring the impact of green wall and its size on restoration effect and stress recovery using immersive virtual environments. Build. Environ.2024, 262 (2024).

- 21.Zhang, N. et al. A comprehensive review of research on indoor cognitive performance using electroencephalogram technology. Build.Environ.2024, 257 (2024).

- 22.Shi, J. et al. A review of applications of electroencephalogram in thermal environment: comfort, performance, and sleep quality. J. Build. Eng (2024).

- 23.Li, J., Wu, W., Jin, Y., Zhao, R. & Bian, W. Research on environmental comfort and cognitive performance based on EEG + VR + LEC evaluation method in underground space. Build. Environ.2021, 198 (2021).

- 24.Frescura, A., Lee, P. J., Jeong, J. H. & Soeta, Y. EEG alpha wave responses to sounds from neighbours in high-rise wood residential buildings. Build. Environ.2023, 242 (2023).

- 25.Hu, S. et al. Correlation between the visual evoked potential and subjective perception at different illumination levels based on entropy analysis. Build. Environ.2021, 194 (2021).

- 26.Lu, M. et al. Critical dynamic characteristics of brain activity in thermal comfort state. Build. Environ.2023, 243 (2023).

- 27.Liu, C. et al. Correlation between brain activity and comfort at different illuminances based on electroencephalogram signals during reading. Build. Environ.2024, 111694 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li, J., Jin, Y., Zhao, R., Han, Y. & Habert, G. Using the EEG + VR + LEC evaluation method to explore the combined influence of temperature and Spatial openness on the physiological recovery of post-disaster populations. Build. Environ.2023, 243 (2023).

- 29.Yin, J., Zhu, S., MacNaughton, P., Allen, J. G. & Spengler, J. D. Physiological and cognitive performance of exposure to biophilic indoor environment. Build. Environ.132, 255–262 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 30.ANSI/ASHRAE. Standard (2023).

- 31.ASHRAE. ASHRAE standard 55: thermal environmental conditions for human occupancy. Am. Soc. Heat. Refrig. Air-Cond Eng. (2017).

- 32.International Organization for Standardization (ISO). Standardization Guidelines (ISO, 2004).

- 33.Tong, L. et al. Research on the preferred illuminance in office environments based on EEG. Buildings13, 859 (2023).

- 34.ASHRAE. Ventilation for Acceptable Indoor Air Quality: ANSI/ASHRAE Standard 62.1–2013 (American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers, 2013).

- 35.Wotton, E. The IESNA lighting handbook and office lighting. Lighting14, 526 (2000).

- 36.Gao, X. et al. Evaluating the impact of Spatial openness on stress recovery: a virtual reality experiment study with psychological and physiological measurements. Build. Environ.269, 112434 (2025). [Google Scholar]