Abstract

Background

Distal radial access (DRA) has emerged as an alternative to transradial access (TRA) in coronary procedures. However, evidence supporting its use in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) remains limited.

Objectives

The purpose of this study was to assess whether DRA is noninferior to TRA in patients undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) for STEMI.

Methods

This multicenter, open-label, randomized controlled trial was conducted at 3 centers in South Korea. Patients undergoing primary PCI for STEMI were randomly assigned to either the DRA or TRA group. The primary endpoint was the puncture success rate. A noninferiority testing with a prespecified margin of 5.65% was performed in the intention-to-treat, per-protocol, and as-treated populations (NCT03611725).

Results

From August 2018 to February 2023, 354 patients were randomized to DRA (n = 176) or TRA (n = 178). The primary endpoint, puncture success rate was 94.3% in DRA and 96.1% in TRA (difference −1.75%; 95% CI −6.20% to 2.71%) in the intention-to-treat analysis. The per-protocol analysis also failed to demonstrate noninferiority (difference −1.72%; 95% CI -5.99% to 2.54%). DRA demonstrated noninferiority to TRA in the as-treated population (difference −1.17%; 95% CI -5.56% to 3.22%). The rates of successful coronary angiography and PCI, access-site crossover, and bleeding complications were comparable between groups. One radial artery occlusion occurred in TRA group at 1-month follow-up.

Conclusions

In STEMI patients, DRA failed to demonstrate noninferiority to TRA in terms of puncture success. However, both access routes showed comparable procedural efficacy and safety. Further validation with a larger, adequately powered study is required to confirm these findings.

Key words: distal radial access, radial access, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction

Central Illustration

Selecting the optimal vascular access route is crucial for safety and procedural success in cardiac procedures.1 Traditionally, transfemoral access (TFA) and transradial access (TRA) have served as primary conduits for delivering various interventional devices to the heart. TRA has largely replaced TFA due to its association with a lower risk of vascular bleeding and mortality.2, 3, 4 However, TRA remains linked to a risk of radial artery occlusion (RAO), which can limit future available options, particularly in patients requiring repeated procedures, coronary artery bypass surgery, or arteriovenous fistula creation.5

Since the introduction of distal radial access (DRA) from the left hand, early adopters have actively explored its potential benefits.6 To date, DRA has emerged as an alternative access route that may further reduce the incidence of RAO and hematoma compared to conventional TRA.7 These advantages have led to growing interest in its application, including in patients with acute coronary syndrome.8, 9, 10, 11, 12

In ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), access-related complications can significantly impact clinical outcomes, especially given the need for potent antiplatelet and anticoagulant therapies. Therefore, current guidelines recommend TRA over TFA to decrease vascular complications, bleeding, and mortality.13,14 However, evidence supporting DRA as the primary access route in STEMI remains limited, as most available data are observational and lack randomized comparisons.11,12,15

We hypothesized that, after completing the learning curve, experienced operators may achieve comparable efficacy and safety with DRA as with TRA, even in STEMI patients. To address this knowledge gap, we aimed to assess whether DRA is noninferior to TRA in terms of successful vascular access in STEMI patients undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI).

Methods

Study design and population

The DRAMI (Comparison of distal radial access and transradial access for the successful puncture in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction) trial was an investigator-initiated, multicenter, open-label, randomized controlled trial (RCT) at 3 participating centers in South Korea (NCT03611725). The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of each participating hospital. All enrolled patients provided written informed consents. Eligible criteria for enrollment were as follows: patients aged ≥19 years who were diagnosed with STEMI and scheduled for primary PCI, and presence of palpable distal radial and radial arteries. Exclusion criteria were cardiogenic shock, prior administration of thrombolytic agent before PCI, refusal to participate in the study, presence of ipsilateral arteriovenous fistula, concurrent participation in another clinical study, pregnant or breastfeeding, and patients with a life expectancy of < 12 months. Experienced operators with at least 100 prior DRA procedures were permitted to participate in the trial. If arterial puncture was not achieved within 5 minutes, operators were advised to switch to an alternative access route.

Study procedures

STEMI patients referred for primary PCI were screened and randomly assigned (1:1) to DRA or TRA using a predesigned randomized table in the catheterization laboratory. There were no restrictions on selecting either the right or left side for vascular access. To ensure rapid crossover in emergency situations, simultaneous antiseptic skin preparation of the wrist, anatomical snuffbox area, and femoral region was recommended. Arterial puncture, preceded by subcutaneous lidocaine injection, was performed using either a venipuncture catheter needle or an open steel needle, guided by arterial pulse palpation. Ultrasound-guided arterial puncture was permitted at the operator’s preference. Antiplatelet agents, heparin, and spasmolytics were administered according to the standard protocols of each institution. Patients requiring revascularization were treated according to the routine protocol of each respective center. Following the coronary procedures, patent hemostasis was achieved as per each center’s protocol, using either adhesive tape fixation with compacted gauze, elastic bandage wrapping, or commercial compression devices. Patient care and medication prescriptions adhered to international STEMI guidelines. Clinical events, bleeding complications, and puncture site abnormalities were assessed before hospital discharge and at 1-month follow-up. Arterial occlusion was carefully evaluated by palpation.

Study endpoints and definitions

The primary endpoint was puncture success rate at the access site. Secondary endpoints included the success rate of coronary angiography (CAG) and PCI, access-site crossover rate, bleeding complications, puncture time, procedure time, fluoroscopic time, fluoroscopic dose, contrast volume, hemostasis time, access site complications at 1-month follow-up, and major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) including any death, any myocardial infarction, and any revascularization at 1-month follow-up.

Puncture success was defined as the successful insertion of the guidewire into the puncture needle, followed by the placement of the introducer sheath into the artery. Puncture time was measured from the moment the puncture needle made contact with the skin to the successful insertion of the mini-guidewire into the artery. Procedure time was defined as the total duration from the initiation of arterial puncture to the completion of PCI. Hemostasis time was recorded as the total time required to achieve complete hemostasis, measured from the start of compression to the removal of compressive materials. Bleeding complications were classified according to the Bleeding Academic Research Consortium (BARC) criteria,16 while hematoma formation was evaluated based on the modified EASY (Early Discharge After Transradial Stenting of Coronary Arteries Study) classification.9 Hematoma Ia was further subclassified into 4 grades based on its size: grade 1 (<2 cm), grade 2 (2-5 cm), grade 3 (>5 cm), and grade 4 (hand swelling). MACE was defined as a composite of all-cause death, any myocardial infarction, and any revascularization. The intention-to-treat (ITT) population included all randomized patients, the per-protocol (PP) population included those who received the assigned intervention without major protocol deviations, and the as-treated population included patients analyzed according to the access site actually used, regardless of randomization.

Statistical analysis

The hypothesis was that DRA would be noninferior to TRA for puncture success. The noninferiority margin was estimated using the point estimate of the indirect CI comparison, as direct constancy assumption could not be verified. Considering previous results from the STEMI-RADIAL trial (STEMI treated by radial or femoral approach) (3.7% crossover of TRA) and Kiemeneij et al (11% failed attempt of DRA),6,17 along with a conservative assumption of a 15% expected failure rate of DRA in this trial, the point estimate of indirect CI comparison was 5.65% (calculated as half of the difference between 3.7% and 15%). This estimate was not inferior to the margin of the plot study. As we could not ensure that the failure rate of DRA would be absolutely higher than that of TRA, we conservatively assumed the difference between the 2 groups to be zero. With 80% power and a 1-sided significance alpha level of 2.5%, a total of 352 patients were required. No interim analysis was planned.

All analyses were conducted according to the ITT principle, with additional PP and as-treated analyses performed for robustness. Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± SD or median (IQR), while categorical variables were presented as counts and percentages. The absolute difference between DRA and TRA was calculated using the Wald CI and the one-sided P value was obtained using the Wald test, assessing whether the lower limit of 95% CI exceeded the prespecified noninferiority margin. Comparisons of CAG success rates, PCI success rates, and bleeding complication rates between groups were performed using the chi-square test or Fisher exact test. Differences in procedure time, fluoroscopic time, and fluoroscopic dose were assessed using the t-test or Wilcoxon rank sum test depending on the results of the normality test. MACEs were analyzed using the Kaplan-Meier survival curve and compared using the log-rank test, with results reported as HRs and 95% CI. A post hoc stratified analysis of the primary endpoint was conducted based on age, sex, body surface area, and chronic kidney disease, with interaction testing performed to explore potential effect modification. These analyses were exploratory in nature and not prespecified in the original study protocol. All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc) and R version 4.3.3 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing). A P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Baseline and procedural characteristics

Between August 2018 and February 2023, 354 STEMI patients undergoing primary PCI were randomly assigned to either DRA (n = 176) or TRA group (n = 178) (Figure 1). The mean age was 63.3 ± 12.0 years, with 286 (80.8%) being male. Baseline characteristics were well-balanced between the groups (Table 1). Comorbidities included hypertension (44.9%), diabetes mellitus (27.7%), dyslipidemia (29.1), and chronic kidney disease (3.1%). Forty patients (11.3%) presented with Killip class 3 or 4, and the median left ventricular ejection fraction was 47% (IQR: 41-54).

Figure 1.

Study Flowchart

DRA = distal radial access; STEMI = ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction; TRA = transradial access.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics

| All (N = 354) | DRA (n = 176) | TRA (n = 178) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 63.3 ± 12.0 | 63.3 ± 11.8 | 63.2 ± 12.2 | 0.914 |

| Male | 286 (80.8) | 141 (80.1) | 145 (81.5) | 0.748 |

| BSA, m2 | 1.8 ± 0.2 | 1.8 ± 0.2 | 1.8 ± 0.2 | 0.854 |

| Medical history | ||||

| Hypertension | 159 (44.9) | 84 (47.7) | 75 (42.1) | 0.290 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 98 (27.7) | 55 (31.3) | 43 (24.2) | 0.136 |

| Dyslipidemia | 103 (29.1) | 55 (31.3) | 48 (27.0) | 0.375 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 11 (3.1) | 6 (3.4) | 5 (2.8) | 0.745 |

| Current smoker | 153 (43.2) | 82 (46.6) | 71 (39.9) | 0.203 |

| Prior MI | 16 (4.5) | 8 (4.5) | 8 (4.5) | 0.982 |

| Prior PCI | 28 (7.9) | 15 (8.5) | 13 (7.3) | 0.671 |

| Prior CVA | 14 (4.0) | 4 (2.3) | 10 (5.6) | 0.106 |

| Prior ICH | 6 (1.7) | 4 (2.3) | 2 (1.1) | 0.447 |

| Prior PAOD | 2 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.1) | 0.499 |

| Systolic BP, mm Hg | 135.3 ± 28.6 | 134.7 ± 27.4 | 135.8 ± 29.8 | 0.699 |

| Diastolic BP, mm Hg | 81.0 (72.0-93.0) | 81.0 (71.5-92.0) | 81.5 (72.0-95.0) | 0.419 |

| Heart rate, beats/min | 76.0 (64.0-91.0) | 80.0 (66.0-92.0) | 74.5 (62.0-87.0) | 0.051 |

| Killip classification | 0.982 | |||

| 1 | 292 (82.5) | 146 (83.0) | 146 (82.0) | |

| 2 | 22 (6.2) | 10 (5.7) | 12 (6.7) | |

| 3 | 26 (7.3) | 13 (7.4) | 13 (7.3) | |

| 4 | 14 (4.0) | 7 (4.0) | 7 (3.9) | |

| LV ejection fraction, % | 47.0 (41.0-54.0) | 48.0 (42.0-54.0) | 47.0 (41.0-55.0) | 0.759 |

| Procedural medications | ||||

| Aspirin loading | 345 (97.5) | 172 (97.7) | 173 (97.2) | >0.999 |

| P2Y12 inhibitor loading | 349 (98.6) | 175 (99.4) | 174 (97.8) | 0.371 |

| Clopidogrel | 64 (18.1) | 31 (17.6) | 33 (18.5) | 0.821 |

| Prasugrel | 22 (6.2) | 8 (4.5) | 14 (7.9) | 0.196 |

| Ticagrelor | 274 (77.4) | 143 (81.3) | 131 (73.6) | 0.085 |

| GP IIbIIIa inhibitor (bolus) | 68 (19.2) | 30 (17.0) | 38 (21.3) | 0.304 |

| Discharge medications | ||||

| Aspirin | 345 (97.5) | 171 (97.2) | 174 (97.8) | 0.750 |

| P2Y12 inhibitor | 338 (95.5) | 168 (95.5) | 170 (95.5) | 0.982 |

| Clopidogrel | 76 (21.5) | 40 (22.7) | 36 (20.2) | 0.566 |

| Ticagrelor | 239 (67.5) | 118 (67.0) | 121 (68.0) | 0.851 |

| Prasugrel | 29 (8.2) | 12 (6.8) | 17 (9.6) | 0.349 |

| Anticoagulant | 18 (5.1) | 12 (6.8) | 6 (3.4) | 0.140 |

| Statin | 343 (96.9) | 167 (94.9) | 176 (98.9) | 0.031 |

| Beta-blocker | 297 (83.9) | 146 (83.0) | 151 (84.8) | 0.631 |

| RAS inhibitor | 217 (61.3) | 106 (60.2) | 111 (62.4) | 0.680 |

Values are mean ± SD, median (IQR), or n (%).

BP = blood pressure; BSA = body surface area; CVA = cerebrovascular accident; DRA = distal radial access; GP = glycoprotein; ICH = intracranial hemorrhage; LV = left ventricle; MI = myocardial infarction; PAOD = peripheral arterial occlusive disease; PCI = percutaneous coronary intervention; RAS = renin-angiotensin system; TRA = transradial access.

Table 2 summarizes the procedural characteristics. Notably, left hand access was more frequent in DRA (91.5%) than TRA group (60.7%) (P < 0.001). Access-site crossover occurred in 19 patients (5.4%), primarily due to puncture failure. Crossover to the femoral artery was observed in 25% (3/12) of DRA crossovers and 57.1% (4/7) of TRA crossovers. Among crossover cases, half of the patients (9/19) were reaccessed via the ipsilateral side. The success rate of CAG was 100% in both groups, while the PCI success rates were 99.4% in the DRA group and 100% in the TRA group. One PCI failure in the DRA group occurred because the culprit lesion was too small, and the guidewire could not be successfully advanced to the lesion. No crossovers occurred during PCI. Aspiration thrombectomy and the use of intravascular ultrasonography were similar between the groups. DRA demonstrated comparable efficacy to TRA in puncture time (P = 0.151). Procedure time, fluoroscopic time and dose, and hemostasis time were also similar. DRA group used more contrast (P = 0.014).

Table 2.

Procedural Characteristics

| All (N = 354) | DRA (n = 176) | TRA (n = 178) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Puncture-related variables | ||||

| Puncture success | 337 (95.2) | 166 (94.3) | 171 (96.1) | 0.442 |

| Puncture within 5 min | 333 (94.1) | 163 (92.6) | 170 (95.5) | 0.249 |

| Initial puncture attempt | <0.001 | |||

| Left hand | 269 (76.0) | 161 (91.5) | 108 (60.7) | |

| Right hand | 85 (24.0) | 15 (8.5) | 70 (39.3) | |

| Overall crossover | 19 (5.4) | 12 (6.9) | 7 (4.0) | 0.238 |

| Reason for crossover | 0.263 | |||

| Puncture failure | 17 (4.8) | 10 (5.7) | 7 (3.9) | |

| GW passing failure | 2 (0.6) | 2 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Crossover site | 0.015 | |||

| Radial artery, left | 8 (2.3) | 8 (4.5) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Radial artery, right | 3 (0.8) | 1 (0.6) | 2 (1.1) | |

| Distal radial artery, left | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.6) | |

| Femoral artery, right | 7 (2.0) | 3 (1.7) | 4 (2.2) | |

| Crossover direction | 0.082 | |||

| Ipsilateral | 9 (2.5) | 8 (4.5) | 1 (0.6) | |

| Contralateral | 3 (0.8) | 1 (0.6) | 2 (1.1) | |

| Femoral | 7 (2.0) | 3 (1.7) | 4 (2.2) | |

| CAG- and PCI-related variables | ||||

| CAG success | 354 (100.0) | 176 (100.0) | 178 (100.0) | N/A |

| PCI performed | 349 (98.6) | 175 (99.4) | 174 (97.8) | 0.371 |

| PCI success | 348 (99.7) | 174 (99.4) | 174 (100.0) | >0.999 |

| Multivessel PCI | 70 (20.1) | 38 (21.7) | 32 (18.4) | 0.438 |

| Bifurcation PCI | 90 (25.8) | 44 (25.1) | 46 (26.4) | 0.782 |

| Aspiration thrombectomy | 182 (52.1) | 90 (51.4) | 92 (52.9) | 0.787 |

| Use of IVUS | 142 (40.7) | 73 (41.7) | 69 (39.7) | 0.695 |

| Culprit lesion | 0.889 | |||

| Left main | 6 (1.7) | 4 (2.3) | 2 (1.1) | |

| Left anterior descending | 174 (49.9) | 88 (50.3) | 86 (49.4) | |

| Left circumflex | 29 (8.3) | 14 (8.0) | 15 (8.6) | |

| Right coronary artery | 140 (40.1) | 69 (39.4) | 71 (40.8) | |

| TIMI flow grade | ||||

| Pre-PCI | 0.149 | |||

| Grade 0 | 233 (66.8) | 126 (72.0) | 107 (61.5) | |

| Grade 1 | 43 (12.3) | 16 (9.1) | 27 (15.5) | |

| Grade 2 | 35 (10.0) | 17 (9.7) | 18 (10.3) | |

| Grade 3 | 38 (10.9) | 16 (9.1) | 22 (12.6) | |

| Post-PCI | 0.430 | |||

| Grade 0 | 2 (0.6) | 1 (0.6) | 1 (0.6) | |

| Grade 1 | 8 (2.3) | 6 (3.4) | 2 (1.1) | |

| Grade 2 | 39 (11.2) | 17 (9.7) | 22 (12.6) | |

| Grade 3 | 300 (86.0) | 151 (86.3) | 149 (85.6) | |

| Stent number | 1.0 (1.0-1.0) | 1.0 (1.0-1.0) | 1.0 (1.0-1.0) | 0.697 |

| Stent diameter, mm | 3.3 (3.0-3.5) | 3.3 (3.0-3.5) | 3.3 (3.0-3.5) | 0.587 |

| Stent length, mm | 28.0 (22.0-38.0) | 28.0 (22.0-38.0) | 30.0 (22.0-38.0) | 0.555 |

| Procedure-related variables | ||||

| Symptom to balloon time, min | 219.0 (146.0-377.0) | 221.0 (150.0-390.0) | 216.5 (143.0-336.0) | 0.663 |

| Door to balloon time, min | 81.0 (68.0-91.0) | 82.0 (69.0-93.0) | 79.5 (68.0-89.0) | 0.256 |

| Puncture time, min | 1.0 (1.0-2.0) | 1.0 (1.0-2.0) | 1.0 (0.8-1.8) | 0.151 |

| Total procedure time, min | 38.0 (29.0-52.0) | 40.0 (29.0-54.0) | 37.0 (29.0-50.0) | 0.121 |

| Fluoroscopic time, min | 10.8 (8.1-16.0) | 11.1 (7.8-17.0) | 10.8 (8.2-15.3) | 0.422 |

| Fluoroscopic dose, Gy·cm2 | 143.4 (103.3-217.3) | 151.0 (108.6-228.7) | 141.3 (99.4-208.8) | 0.218 |

| Contrast volume, mL | 150.0 (120.0-180.0) | 150.0 (120.0-187.5) | 140.0 (110.0-170.0) | 0.014 |

| Hemostasis time, min | 180.0 (180.0-180.0) | 180.0 (180.0-180.0) | 180.0 (180.0-180.0) | 0.375 |

Values are mean ± SD, median (IQR), or n (%).

CAG = coronary angiography; GW = guidewire; IVUS = intravascular ultrasonography; other abbreviations as in Table 1.

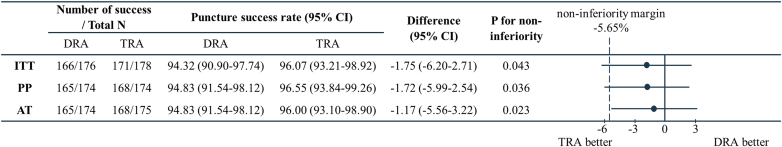

Noninferiority analyses of puncture success rate

The primary endpoint, puncture success rate was 94.32% (95% CI: 90.9%-97.74%) in the DRA group and 96.07% (95% CI: 93.21%-98.92%) in the TRA group (difference −1.75%; 95% CI: −6.2% to 2.71%; P = 0.043) in the ITT population, demonstrating that the test for noninferiority failed (Figure 2). PP analysis yielded a similar result (difference −1.72%; 95% CI: −5.99% to 2.54%; P = 0.036). However, the puncture success rate of DRA was significantly noninferior to TRA in the as-treated population (difference −1.17%; 95% CI: −5.56% to 3.22%; P = 0.023).

Figure 2.

Forest Plot of Noninferiority Analyses on the Puncture Success Rate

AT = as treated; ITT = intention-to-treat; PP = per-protocol; other abbreviations as in Figure 1.

Bleeding complications and clinical outcomes

Overall, bleeding complications occurred in 17 patients (4.8%) (Table 3). The incidence rate of access site bleeding complication was 2.8% (10 patients). No statistical differences were observed regarding overall bleeding complications, bleedings according to BARC classification, and bleeding type between the groups. One case of BARC type 3b in the DRA group was associated with gastrointestinal bleeding. During hospitalization, 3 cases (0.8%) of MACE were reported in the DRA group, including 2 cardiac deaths and one noncardiac death, none of which were associated with access site complications.

Table 3.

Complications and Clinical Outcomes

| All (N = 354) | DRA (n = 176) | TRA (n = 178) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bleeding complications | 17 (4.8) | 8 (4.5) | 9 (5.1) | 0.822 |

| Access-site-related bleeding | 10 (2.8) | 4 (2.3) | 6 (3.4) | 0.750 |

| BARC definition | 0.916 | |||

| Type 1 | 10 (2.8) | 4 (2.3) | 6 (3.4) | |

| Type 2 | 6 (1.7) | 3 (1.7) | 3 (1.7) | |

| Type 3b | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Bleeding type | 0.492 | |||

| Access site | 10 (2.8) | 4 (2.3) | 6 (3.4) | |

| Hemoptysis | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Epistaxis | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.6) | |

| Gingival bleeding | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.6) | |

| GI bleeding | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | |

| GU bleeding | 3 (0.8) | 2 (1.1) | 1 (0.6) | |

| In-hospital MACE | 3 (0.8) | 3 (1.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0.122 |

| In-hospital death | 3 (0.8) | 3 (1.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0.122 |

| Death type | ||||

| Cardiac death | 2 | 2 | 0 | |

| Noncardiac death | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| MI related to the target vessel | 0 | 0 | 0 | Not applicable |

| Target lesion revascularization | 0 | 0 | 0 | Not applicable |

| Stent thrombosis | 0 | 0 | 0 | Not applicable |

| One-month follow-up | ||||

| Follow-up at 1 month | 350 (98.9) | 173 (98.3) | 177 (99.4) | 0.370 |

| Access site complication | 5 (1.4) | 2 (1.2) | 3 (1.7) | >0.999 |

| Complication type | 0.902 | |||

| Occlusion | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.6) | |

| Neuropathy | 3 (0.9) | 1 (0.6) | 2 (1.1) | |

| Hand swelling or pain | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | |

| MACE at 1 month | 4 (1.1) | 3 (1.7) | 1 (0.6) | 0.367 |

| Cardiac death | 4 (1.1) | 3 (1.7) | 1 (0.6) | 0.367 |

| MI related to the target vessel | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0.494 |

| Target lesion revascularization | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0.494 |

| Stent thrombosis | 4 (1.1) | 3 (1.7) | 1 (0.6) | 0.367 |

| By duration | ||||

| Subacute | 4 (1.1) | 3 (1.7) | 1 (0.6) | 0.367 |

| By definition | 0.424 | |||

| Definite | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Probable | 3 (0.9) | 2 (1.2) | 1 (0.6) |

Values are mean ± SD, median (IQR), or n (%).

BARC = Bleeding Academic Research Consortium; MACE = major adverse cardiovascular events; GI = gastrointestinal; GU = genitourinary; other abbreviations as in Table 1.

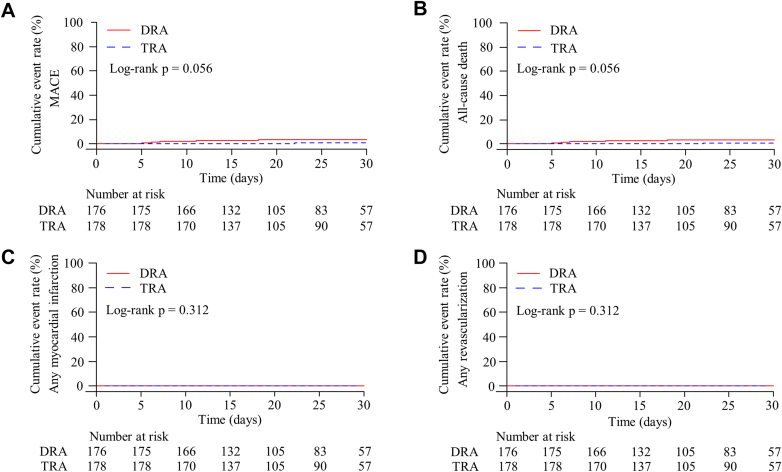

One-month follow-up after discharge was completed in 350 patients (98.9%) (Figure 3). Access site complications were rare and similar between groups (DRA 1.2% vs TRA 1.7%; P > 0.999). There was one RAO in the TRA group. Neuropathy was reported in one DRA and 2 TRA patients. During the follow-up period, 4 MACEs occurred, including 3 cardiac deaths in DRA, and one cardiac death in TRA (P = 0.367).

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier Plots of Safety Endpoints During 1-Month Follow-Up

The cumulative event rate of (A) MACE, (B) all-cause death, (C) any myocardial infarction, and (D) any revascularization. MACE = major adverse cardiovascular events; other abbreviations as in Figure 1.

Subgroup analysis for puncture success rate

No significant interactions were found for the puncture success across subgroups including age, sex, body surface area, and chronic kidney disease (Table 4).

Table 4.

Subgroup Analysis of Puncture Success Rate

| Puncture Success Rate (%) |

Absolute Difference (95% CI) | P Value | P Interaction | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DRA | TRA | ||||

| Gender | 0.441 | ||||

| Female | 32/35 (91.4) | 32/33 (97.0) | −5.54 (−16.51-5.42) | 0.322 | |

| Male | 134/141 (95.0) | 139/145 (95.9) | −0.83 (−5.66-4.01) | 0.737 | |

| Age | 0.328 | ||||

| <65 y | 96/101 (95.0) | 91/96 (94.8) | 0.26 (−5.88-6.39) | 0.934 | |

| ≥65 y | 70/75 (93.3) | 80/82 (97.6) | −4.23 (−10.79-2.33) | 0.206 | |

| BSA, m2 | 0.206 | ||||

| <1.79 (median) | 80/87 (92.0) | 85/88 (96.6) | −4.64 (−11.50-2.22) | 0.185 | |

| ≥1.79 (median) | 86/89 (96.6) | 85/89 (95.5) | 1.12 (−4.58-6.83) | 0.700 | |

| Chronic kidney disease | Not applicable | ||||

| No | 160/170 (94.1) | 166/173 (96.0) | −1.84 (−6.43-2.76) | 0.434 | |

| Yes | 6/6 (100.0) | 5/5 (100.0) | - | - | |

Values are mean ± SD, median (IQR), or n (%).

Abbreviations as in Table 1.

Discussion

The DRAMI trial assessed whether DRA is noninferior to TRA as the primary access in STEMI patients undergoing PCI. However, in the ITT analysis, DRA failed to demonstrate noninferiority to TRA in terms of puncture success rate. Noninferiority was only established in the as-treated analysis but not in the PP analysis. Nevertheless, DRA exhibited a high puncture success rate (94.3%), along with comparable procedural outcomes. Notably, there were no major bleeding events specifically related to DRA among 4.5% of bleeding complications (Central Illustration).

Central Illustration.

Major Findings of the DRAMI Trial

CAG = coronary angiography; DRAMI = Comparison of distal radial access and transradial access for the successful puncture in patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction; PCI = percutaneous coronary intervention; other abbreviations as in Figure 1.

Registry-based studies have reported the clinical experiences of DRA in STEMI patients. A retrospective study of 138 STEMI patients across 3 hospitals demonstrated a DRA success rate of 92.8%, with 95.3% of patients achieving successful puncture within 5 minutes.11 In that study, all patients underwent primary PCI without major bleeding events related to DRA. Similarly, the DISTRACTION (DIStal TRAnsradial access as default approach for Coronary angiography and intervenTIONs) prospective cohort registry included 849 STEMI patients (22.9% of the total 3,700 patients enrolled).18 In this cohort, access-site crossover due to failed insertion of a mini guidewire occurred in only 17 patients (2%), with no reported DRA-related bleeding or hematoma. Other studies have also supported the safety profile of DRA.15,19 A recent meta-analysis comparing DRA and TRA, based on 4 studies with 543 patients undergoing emergency CAG or PCI, suggested that DRA reduced the incidence of RAO and shortened hemostasis duration, while maintaining a comparable periprocedural complication rate to TRA.12 However, further large-scale studies directly comparing DRA with TRA or TFA are needed to confirm these findings and better define the clinical benefits of DRA in STEMI management.

In the current era when TRA is the standard access over TFA for coronary procedures, a network meta-analysis of 47 RCTs comparing 4 different access routes (DRA, TRA, TFA, and transulnar access) suggested that DRA could be considered a secondary default access route before switch to TFA.20 In this analysis, DRA ranked favorably for major bleeding, hematoma, arterial occlusion, and spasm, but less favorably for crossover, contrast volume, and fluoroscopy time. These aspects require further validation through adequately powered comparisons. In our study, bleeding complications were comparable between DRA and TRA. Additionally, no RAO cases were observed in the DRA group, with only one case of neuropathy and one case of access-site tenderness at 1-month follow-up. Given the importance of balancing the risks of both bleeding and ischemic events, the DRAMI trial contributes to bridge an important knowledge gap in STEMI patients.

This study also provided detailed insights into procedural characteristics. The rate of successful DRA puncture within 5 minutes was slightly lower than, but not significantly different from, TRA. DRA and TRA showed no significant differences in door-to-balloon time, puncture time, procedural duration, and fluoroscopic time. The median time to hemostasis (3 hours) was also similar between the 2 access routes. Aoi et al reported a mean hemostasis time of 104.7 minutes using a TR band (Terumo), with times of 120.8 minutes for PCI cases and 91.7 minutes for CAG.21 Using the dedicated pneumatic compression device, PreludeSYNC DISTAL (Merit Medical Systems, Inc), the mean hemostasis time was 161 minutes in 50 patients.22 The HEMOBOX (Optimal Hemostasis Duration for Percutaneous Coronary Intervention via Snuffbox Approach) trial, which used a cohesive elastic bandage, reported a mean 199 minutes (median 180 minutes).23 A meta-analysis of 10 RCTs including 4,911 patients suggested that a hemostasis duration of 2 hours after TRA provided the best balance between preventing RAO and minimizing bleeding risk.24 Thus, further efforts to reduce hemostasis time may enhance the benefits of DRA. Interestingly, the DRA group in our study required a slightly higher contrast volume (median 150 mL) compared to the TRA group (median 140 mL). The underlying reason for this difference remains unclear. However, the absolute contrast volume in both groups were lower than that reported in the RIVAL (RadIal Vs femorAL access for coronary intervention) trial (median 180 mL) and the STEMI-RADIAL (ST Elevation Myocardial Infarction treated by RADIAL or femoral approach) trial (mean 170 mL).17,25

It remains uncertain whether the puncture success rate of DRA requires further evaluation in a separate study. In the DRAMI trial, the actual puncture success rate in the DRA group (94.3%) exceeded the estimated 85% rate assumed in the primary noninferiority hypothesis. Paradoxically, this high success rate suggests that, once operators become proficient with DRA after completing the learning curve, additional studies focusing on puncture feasibility as a primary endpoint may no longer necessary, even in emergency situations.

Of note, an additional benefit of DRA was observed in the crossover pattern. Among the 12 crossover cases (6.9%) in the DRA group, three-quarters (9 of 12) of patients switched to TRA, while only one-quarter (3 of 12) required crossover to TFA. The crossover rate to TFA in DRAMI trial (1.7%) was less than half of that reported in the MATRIX (Minimizing Adverse Haemorrhagic Events by Transradial Access Site and Systemic Implementation of Angiox)-Access trial (4.4%).26,27 This crossover pattern aligns with findings from 2 landmark trials.9,10 In the KODRA (Korean Prospective Registry for Evaluating the Safety and Efficacy of Distal Radial Approach) study, which included 4,977 patients, access-site crossover occurred in 6.7% (n = 333), with only 1.3% (63 of 4,977) switching to TFA. Similarly, in the DISCO RADIAL (Distal vs Conventional Radial Access) trial, 7.4% (48 of 650) of patients in the DRA group required crossover, but only 1.9% (12 of 650) switched to TFA. In all these studies, most crossovers remained within the ipsilateral upper extremity. These findings support the adoption of a DRA-first strategy as a feasible approach to minimize the need for TFA and improve procedural safety.

An unexpected finding of this study was the difference in the selection of the initial access side. Left TRA was significantly more common in the DRA group (91.5%) compared to the TRA group (60.7%). Historically, when Lucien Campeau introduced TRA in 1989, the left radial artery was used for cardiac catheterization.28 However, improved ergonomic setup and patient positioning favored the widespread adoption of right TRA. For instance, data from the British Cardiovascular Intervention Society, comprising 342,806 cases between 2007 and 2014, demonstrated a strong preference for right TRA (96%). Although Babunashvili introduced left TRA, and Kiemeneij later promoted left DRA by positioning the left upper arm across the body over the right groin,6,29 a similar preference for right DRA has been observed.7, 8, 9,30 This preference pattern for right-sided access is unlikely to change, unless RCTs provide concrete evidence comparing clinical outcomes between left and right access.

From a practical standpoint, the smaller diameter of the distal radial artery may affect puncture success and procedural outcomes. An ultrasonographic assessment of 1,162 consecutive Korean patients showed that the distal radial artery is, on average, 20% smaller than that the conventional radial artery.31 Approximately half of the patients in that study had arteries unsuitable for a 5-F introducer sheath (2.3 mm outer diameter), with smaller vessel size being associated with female sex, low body surface area, and low body mass index. Step-by-step ultrasound-guided DRA can be especially helpful during the learning curve, providing essential anatomical information and preventing unforeseen complications.32, 33, 34, 35

Study limitations

Several limitations of this study need to be acknowledged. First, the noninferiority margin based on absolute differences in event rates is more susceptible to heterogeneity across different study settings compared to margin based on relative risk differences. Second, operators performed punctures mainly by pulse palpation without ultrasonography. Given the procedural advantages of ultrasound-guided puncture, a more unbiased comparison could have been achieved with wider adoption of this technique for the new access route. Third, the COVID-19 pandemic caused unexpected delays in the study and hindered consecutive patient enrollment. Although, we made efforts to minimize bias in patient enrollment and randomization in line with hospital and government policies, we cannot rule out the possibility of unreported cases during screening.

Conclusions

In STEMI patients, DRA failed to meet predefined noninferiority criteria compared to TRA for puncture success. However, both DRA and TRA showed comparable procedural feasibility and safety. Based on these findings, a larger, well-powered study is warranted to confirm the role of DRA in the emergency setting.

Declaration of Generative AI and AI-Assisted Technologies in the Writing Process

During the preparation of this work, the author(s) used ChatGPT (OpenAI) to assist with improving the clarity and quality of English language in the manuscript. After using this tool/service, the author(s) reviewed and edited the content as needed and take(s) full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Perspectives.

COMPETENCY IN MEDICAL KNOWLEDGE: DRA has provided an alternative to TRA in routine coronary procedures. However, evidence supporting its use in STEMI patients undergoing primary PCI remains limited.

In the DRAMI trial, DRA demonstrated a comparable and high success rate for arterial puncture, as well as for CAG and PCI, with low bleeding complications. However, DRA failed to demonstrate noninferiority to TRA regarding puncture success.

TRANSLATIONAL OUTLOOK: The highly acceptable safety and efficacy of DRA compared to TRA suggest the need for further studies to validate its potential as an alternative access route in STEMI.

Funding support and author disclosures

This work was supported by Hanmi Pharmaceutical Co, Ltd (grant numbers IIT-ROBE-009) to Dr Jun-Won Lee. All other authors have reported that they have no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the patients who participated in this study, coinvestigators, coordinators, research nurses, and statisticians.

Footnotes

The authors attest they are in compliance with human studies committees and animal welfare regulations of the authors’ institutions and Food and Drug Administration guidelines, including patient consent where appropriate. For more information, visit the Author Center.

References

- 1.Byrne R.A., Cassese S., Linhardt M., Kastrati A. Vascular access and closure in coronary angiography and percutaneous intervention. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2013;10:27–40. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2012.160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Doll J.A., Beaver K., Naranjo D., et al. Trends in arterial access site selection and bleeding outcomes following coronary procedures, 2011-2018. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2022;15 doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.121.008359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Neumann F.J., Sousa-Uva M., Ahlsson A., et al. 2018 ESC/EACTS Guidelines on myocardial revascularization. Eur Heart J. 2019;40:87–165. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Writing Committee M., Lawton J.S., Tamis-Holland J.E., et al. 2021 ACC/AHA/SCAI guideline for coronary artery revascularization: a report of the American college of cardiology/American heart association joint committee on clinical practice guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022;79:e21–e129. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2021.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rashid M., Kwok C.S., Pancholy S., et al. Radial artery occlusion after transradial interventions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5 doi: 10.1161/JAHA.115.002686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kiemeneij F. Left distal transradial access in the anatomical snuffbox for coronary angiography (ldTRA) and interventions (ldTRI) EuroIntervention. 2017;13:851–857. doi: 10.4244/EIJ-D-17-00079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ferrante G., Condello F., Rao S.V., et al. Distal vs conventional radial access for coronary angiography and/or intervention: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2022;15:2297–2311. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2022.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee J.W., Park S.W., Son J.W., Ahn S.G., Lee S.H. Real-world experience of the left distal transradial approach for coronary angiography and percutaneous coronary intervention: a prospective observational study (LeDRA) EuroIntervention. 2018;14:e995–e1003. doi: 10.4244/EIJ-D-18-00635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee J.W., Kim Y., Lee B.K., et al. Distal radial access for coronary procedures in a large prospective multicenter registry: the KODRA trial. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2024;17:329–340. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2023.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aminian A., Sgueglia G.A., Wiemer M., et al. Distal versus conventional radial access for coronary angiography and intervention: the DISCO RADIAL trial. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2022;15:1191–1201. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2022.04.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim Y., Lee J.W., Lee S.Y., et al. Feasibility of primary percutaneous coronary intervention via the distal radial approach in patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Korean J Intern Med. 2021;36:S53–S61. doi: 10.3904/kjim.2019.420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bittar V., Trevisan T., Clemente M.R.C., Pontes G., Felix N., Gomes W.F. Distal versus traditional radial access in patients undergoing emergency coronary angiography or percutaneous coronary intervention: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Coron Artery Dis. 2025;36:18–27. doi: 10.1097/MCA.0000000000001411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Byrne R.A., Rossello X., Coughlan J.J., et al. 2023 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes. Eur Heart J. 2023;44:3720–3826. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehad191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rao S.V., O'Donoghue M.L., Ruel M., et al. 2025 ACC/AHA/ACEP/NAEMSP/SCAI guideline for the management of patients with acute coronary syndromes: a report of the American college of Cardiology/American heart association joint committee on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation. 2025 doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000001309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee O.H., Kim Y., Son N.H., et al. Comparison of distal radial, proximal radial, and femoral access in patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction. J Clin Med. 2021;10:3438. doi: 10.3390/jcm10153438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mehran R., Rao S.V., Bhatt D.L., et al. Standardized bleeding definitions for cardiovascular clinical trials: a consensus report from the Bleeding Academic Research Consortium. Circulation. 2011;123:2736–2747. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.009449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bernat I., Horak D., Stasek J., et al. ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction treated by radial or femoral approach in a multicenter randomized clinical trial: the STEMI-RADIAL trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63:964–972. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.08.1651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oliveira M.D., Caixeta A. Distal transradial access for primary PCI in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2022;15:794–795. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2022.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yamada T., Matsubara Y., Washimi S., et al. Vascular complications of percutaneous coronary intervention via distal radial artery approach in patients with acute myocardial infarction with and without ST-segment elevation. J Invasive Cardiol. 2022;34:E259–E265. doi: 10.25270/jic/20.00411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maqsood M.H., Yong C.M., Rao S.V., Cohen M.G., Pancholy S., Bangalore S. Procedural outcomes with femoral, radial, distal radial, and ulnar access for coronary angiography: a network meta-analysis. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2024;17 doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.124.014186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aoi S., Htun W.W., Freeo S., et al. Distal transradial artery access in the anatomical snuffbox for coronary angiography as an alternative access site for faster hemostasis. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2019;94:651–657. doi: 10.1002/ccd.28155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kawamura Y., Yoshimachi F., Nakamura N., Yamamoto Y., Kudo T., Ikari Y. Impact of dedicated hemostasis device for distal radial arterial access with an adequate hemostasis protocol on radial arterial observation by ultrasound. Cardiovasc Interv Ther. 2021;36:104–110. doi: 10.1007/s12928-020-00656-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Roh J.W., Kim Y., Takahata M., et al. Optimal hemostasis duration for percutaneous coronary intervention via the snuffbox approach: a prospective, multi-center, observational study (HEMOBOX) Int J Cardiol. 2021;338:79–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2021.06.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maqsood M.H., Pancholy S., Tuozzo K.A., Moskowitz N., Rao S.V., Bangalore S. Optimal hemostatic band duration after transradial angiography or intervention: insights from a mixed treatment comparison meta-analysis of randomized trials. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2023;16 doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.122.012781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jolly S.S., Yusuf S., Cairns J., et al. Radial versus femoral access for coronary angiography and intervention in patients with acute coronary syndromes (RIVAL): a randomised, parallel group, multicentre trial. Lancet. 2011;377:1409–1420. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60404-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gragnano F., Branca M., Frigoli E., et al. Access-site crossover in patients with acute coronary syndrome undergoing invasive management. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2021;14:361–373. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2020.11.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Valgimigli M., Frigoli E., Leonardi S., et al. Radial versus femoral access and bivalirudin versus unfractionated heparin in invasively managed patients with acute coronary syndrome (MATRIX): final 1-year results of a multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2018;392:835–848. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31714-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Campeau L. Percutaneous radial artery approach for coronary angiography. Cathet Cardiovasc Diagn. 1989;16:3–7. doi: 10.1002/ccd.1810160103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Babunashvili A., Dundua D. Recanalization and reuse of early occluded radial artery within 6 days after previous transradial diagnostic procedure. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2011;77:530–536. doi: 10.1002/ccd.22846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oliveira M.D., Navarro E.C., Caixeta A. Distal transradial access for coronary procedures: a prospective cohort of 3,683 all-comers patients from the DISTRACTION registry. Cardiovasc Diagn Ther. 2022;12:208–219. doi: 10.21037/cdt-21-542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee J.W., Son J.W., Go T.H., et al. Reference diameter and characteristics of the distal radial artery based on ultrasonographic assessment. Korean J Intern Med. 2022;37:109–118. doi: 10.3904/kjim.2020.685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hadjivassiliou A., Kiemeneij F., Nathan S., Klass D. Ultrasound-guided access to the distal radial artery at the anatomical snuffbox for catheter-based vascular interventions: a technical guide. EuroIntervention. 2021;16:1342–1348. doi: 10.4244/EIJ-D-19-00555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sgueglia G.A., Lee B.K., Cho B.R., et al. Distal radial access: consensus report of the first korea-Europe transradial intervention meeting. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2021;14:892–906. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2021.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jeon H.S.L.J., Son J.W., Youn Y.J., Ahn S.G., Lee J.W. Step by step instructions for distal radial access. J Cardiovasc Interv. 2024;3:23–28. doi: 10.54912/jci.2023.0017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen T., Yu X., Song R., Li L., Cai G. Application of ultrasound in cardiovascular intervention via the distal radial artery approach: new wine in old bottles? Front Cardiovasc Med. 2022;9 doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2022.1019053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]