Abstract

Oxidative stress is a key factor in the progression of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and other neurodegenerative disorders. We evaluated whether sinomenine hydrochloride (SH) exhibits antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects against cadmium chloride (CdCl2)-induced neurodegeneration and synaptic impairment in mouse brains. The mice were allowed to undergo Cd injection for two weeks. SH was administered orally for eight consecutive weeks (100 mg/kg/bw/mouse, p.o.). The heavy metal cadmium (Cd) disrupts cellular metabolism in the brain, increasing levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and lipid peroxidation (LPO), which affects glutathione (GSH) and the production of regulatory enzymes, such as glutathione reductase (GSH-R). An imbalance in this homeostatic system may lead to the downregulation of nuclear factor erythroid-2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) and the enzyme heme oxygenase 1 (HO-1) expression in the Cd-injected mouse brain. Interestingly, the levels of both Nrf2 and HO-1 increased in the Cd + SH-treated mice. Additionally, toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4), phospho-nuclear factor kappa B (p-NF-kB), and phospho-c-Jun N-terminal kinase (p-JNK) expressions were elevated in the Cd-treated group, but significantly downregulated in the Cd + SH-treated mice brains. Similarly, SH inhibits Cd-induced apoptotic markers in mouse hippocampal tissues. These results suggest that SH may mitigate Cd-induced mitochondrial oxidative stress and inflammatory responses in wild-type mice brain hippocampus by regulating the NRF-2/HO-1 signaling pathways.

Graphical Abstract

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s11481-025-10243-0.

Keywords: Cadmium, Mitochondrial oxidative stress, Apoptosis, Neuroinflammation, Sinomenine hydrochloride, Neurodegeneration

Introduction

Oxidative stress can lead to neuronal toxicity and disturbance in the equilibrium of oxidative events and antioxidant defenses, followed by loss of antioxidant enzymes or by overproduction of oxidizing species (Emir et al. 2011; Guo et al. 2013a). Glutathione reductase (GSH-R) and glutathione (GSH) play a vital role in maintaining redox homeostasis and protecting neuronal cells from oxidative stress-induced neurological disorders (Chakravorty et al. 2019; Singh et al. 2019). The GSH is the most abundant antioxidant in the central nervous system (CNS), which protects neuronal cells from oxidative damage caused by reactive oxygen species (ROS) and reactive nitrogen species (RNS). Lack of GSH contributes to oxidative damage in neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s (AD) and Parkinson’s disease (PD). Progressive oxidative stress leads to the generation and accumulation of ROS both at the level of cells and tissues (Aoyama 2021; Kim 2021). Imbalance in oxidative stress may lead to neuronal cell loss and memory dysfunction (Lin and Beal 2006).

Heavy metals like cadmium (Cd) can easily cross the Blood Brain Barrier (BBB), which is localized at the level of the brain and affects synaptic activity, neuronal communications, and normal neuronal function (Arruebarrena et al. 2023). The localized Cd in brain cells and tissues induced oxidative stress, apoptosis, neuroinflammation, and neurodegeneration (Aljelehawy 2022). Several studies have revealed that Cd-induced oxidative stress is one of the etiological factors contributing to neurodegeneration development. Similarly, oxidative stress leads to mitochondrial damage and reduced generation and release of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) (Górska et al. 2023). Other studies also reported that the localization of Cd in the brain creates reactive oxygen species (ROS) and lipid peroxidation (LPO). Overproduction of ROS and LPO may cause failure in natural anti-oxidant defense mechanisms (Ganie et al. 2016). The nuclear factor-erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) and hemeoxygenase-1 (HO-1) both act as natural endogenous antioxidants against oxidative stress. In the absence of any stress, Nrf2 is located in the cytoplasm with Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 (Keap-1) in a non-active form (Plascencia-Villa and Perry 2021). Under Stress conditions, Nrf2 dissociates from Keap-1, translocates from the cytoplasm to the nucleus, and promotes further molecular pathways. The mammal brain has a high sensitivity to elevated ROS because of high oxygen demand and lipid composition (Ferreira et al. 2015). Hence, Cd elevates the brain antioxidant system following neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration, which results in cognitive disorders (Rezaei et al. 2024).

Progress in mitochondrial stress forms ROS species and may cause neuroinflammation. Microglial cells can either induce or control neuroinflammation (Agostinho et al. 2010). Regulating the activated microglial cells plays a crucial role in minimizing neuroinflammation and providing an effective therapeutic approach for neurodegenerative diseases (Branca et al. 2020). Cd-induced neuroinflammation triggers the immune system, which is involved in the progression of further neurodegeneration. The regulation of immunological responses has gained keen interest because most neurological conditions are associated with chronic immune cell activation, such as TLR4, GFAP, Iba-1, etc. (Ali et al. 2024; Guedes et al. 2018).

Another component contributing to Cd-induced neurotoxicity is apoptotic cell death (Al Olayan et al. 2020), which is also facilitated by several mediators, including Jun-N-terminal kinase (JNK), and activation of the innate immune system, both are collectively responsible for neurodegeneration and memory impairments (Khan et al. 2019). The main biomarkers associated with synaptic dysfunction, memory impairment, and neurodegeneration include caspases and BCL2-associated X protein (Bax) (S.-I. Alam et al. 2021a, b; Ali et al. 2020).

Sinomenine hydrochloride (SH) is a highly stable hydrochloride form of sinomenine extracted from the Chinese medicinal plant Sinomenium acutum (Liao et al. 2021; Ni et al. 2024). Many studies have shown that SH has strong antioxidative, anti-inflammatory, analgesic (Jiang et al. 2020), and anticancer properties (Qin et al. 2016). This finding indicates that SH has pharmacological and therapeutic potential. In vivo and in vitro experiments showed that SH reduced acetaminophen-induced acute liver injury through antioxidative and anti-inflammatory effects (Chen et al. 2020). To our knowledge, the effect of SH on Cd-induced oxidative stress, neuroinflammation, apoptosis, and neurodegeneration has not yet been reported. Thus, this study was designed to investigate SH protective effects on oxidative stress, inflammation, and apoptotic-induced neurodegeneration in mice, aiming to provide some insights into the therapeutic intervention of Cd-induced neurotoxicity.

Materials and Methods

Chemical and Reagents

Sinomenine Hydrochloride (SH), Cd, and 2, 7-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO, United States).

Antibodies

Table 1.

Table 1.

Antibodies used in both the Western blot and immunofluorescences are:

| Antibody | Dilution (µl) | Application | Manufacturer | Ref. | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GSH-R | 1:1000 | Western Blot | Santa Cruz | sc-133,245 | Mouse |

| GSH | 1:1000 | Western Blot | Santa Cruz | sc-52,399 | Mouse` |

| Nrf2 | 1:1000/1:100 | Western Blot/Confocal | Cell Signaling, USA | 12,721 S | Rabbit |

| Histone H3 | 1:1000 | Western Blot | Santa Cruz | Sc-517,576 | Mouse |

| HO-1 | 1:1000/1:100 | Western Blot | Santa Cruz | Sc-136,961 | Mouse |

| TLR4 | 1:1000 | Western Blot/Confocal | Santa Cruz | Sc-293,072 | Mouse |

| Iba-1 | 1:1000 | Western Blot | Santa Cruz | Sc-39,840 | Mouse |

| GFAP | 1:1000/1:100 | Western Blot/Confocal | Santa Cruz | Sc-33,673 | Mouse |

| p-JNK | 1:1000 | Western Blot | Santa Cruz | Sc-6254 | Mouse |

| JNK | 1:1000 | Western Blot | Santa Cruz | Sc-7345 | Mouse |

| p-NF KB | 1:1000 | Western Blot | Santa Cruz | Sc-136,548 | Mouse |

| NF KB | 1:1000 | Western Blot | Santa Cruz | Sc-372 | Mouse |

| TNF-α | 1:1000 | Western Blot/Confocal | Santa Cruz | Sc-52,746 | Mouse |

| Bax | 1:1000/1:100 | Western Blot/Confocal | Santa Cruz | Sc-7480 | Mouse |

| Bcl-2 | 1:1000 | Western Blot | Santa Cruz | Sc-7382 | Mouse |

| PSD-95 | 1:1000/1:100 | Western Blot/Confocal | Santa Cruz | Sc-71,933 | Mouse |

| SNAP-23 | 1:1000 | Western Blot | Santa Cruz | Sc-374,215 | Mouse |

| β- Actin | 1:10000 | Western Blot | Santa Cruz | Sc-47,778 | Mouse |

Secondary antibodies were diluted with a concentrations of 1:10000 µl (v/v) in 1x TBST

Animals

Wild type eight weeks old male C57BL/6 N mice (total mice n = 32, 8 mice per group) having weight 30–32 g were acquired from Samtako Bio, Osan, South Korea. The female mice were excluded due to the estrous cycle, which may affect the behavior of female mice (Tsao et al. 2023). All the mice were handled carefully and followed the approved guideline (Approval ID: 125, Code: GNU-200331-M0020) of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of the Division of Applied Life Science, Gyeongsang National University, South Korea. The mice were acclimated for 7 days in an animal house maintaining temperature, 20 ± 2 ◦C; humidity 40% ± 10%; 12 h light/dark cycle, and fed with normal pellet food and water ad labitum.

Mice Grouping and Treatment

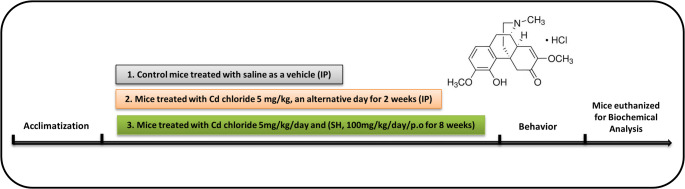

All the experimental animals were categorized into four different groups (n = 8 per group among them n = 4 for western bot and n = 4 for immunofluorescence). The normal control group (treated with I.p. 0.9% NaCl), the Cd-chloride treated group (I.p. Cd 5 mg/kg/day/bw for 2 weeks) (S.-I. Alam et al. 2021a, b), the Cd + Sinomenine hydrochloride group (Cd + SH, 100 mg/kg/day/bw) and only Sinomenine hydrochloride group (100 mg/kg/day/bw) (Li et al. 2023). SH was given orally (P.O.) for 8 weeks (two weeks along with Cd and 6 weeks post-Cd injection) through gavage (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Experimental design of Sinomenine Hydrochloride against Cd-Induced oxidative stress, neuroinflammation, and apoptosis-mediated neurodegeneration

Dissolution of Cadmium and Sinomenine Hydrochloride

The Cd and SH were dissolved separately in a small amount of normal Saline (0.9% NaCl) and then the final volume was adjusted by adding more normal saline. The dissolved drugs were then poured into an amber glass bottle and stored at 4 °C. Both drugs are ready for administration.

Behavioral Tests

Morris Water Maze

The MWM instrument consists of a circular water tank (100 cm in diameter, 40 cm in height), filled with water (23 ± 1 °C) at a depth of 15.5 cm, white ink was used which made the water opaque. The white hidden escape platform (4.5 cm in diameter, 14.5 cm in height) was placed 1 cm below the water surface and fixed in the middle of one of the quadrants. Each mouse was trained for five consecutive days to find a hidden platform in the targeted quadrant. The latency to escape from the water maze of each trial was calculated. After twenty-four hours of the 5th day, the probe test was carried out to examine memory consolidation. The hidden platform was removed and allows each mouse to swim freely for 60 s. The time spent and number of crossing in targeted quadrant (where the platform was located during hidden platform training) was measured. Time spent in the target quadrant was referred to represent the degree of memory consolidation. The video-tracking software (SMART, Panlab Harvard Apparatus; Bioscience Company, Holliston, MA, USA) recorded all the experimental data.

Y-Maze

Y-maze apparatus made up of black-painted wood consists of three equally divided arms. Each arm of the Y-maze was 50 cm long, 20 cm high and 10 cm wide at the bottom, and 10 cm wide at the top. All the mice were placed one by one in the center of the instrument and allowed to move freely through the Y-maze for 8-min duration. The number of arm entries was observed by the naked eye. The mice successful entries into the three arms in overlapping triplet sets were considered to be spontaneous alteration. The alteration behavior percentage (%) was calculated as [successive triplet sets (entries into three different arms consecutively)/total number of arm entries-2] х 100. Increases in the percentage of spontaneous alternation behavior were referred to as improved cognitive functions.

Extraction of Cytoplasmic and Nuclear NRF2 Proteins

Brain hippocampal tissues was homogenized and separated using the Active Motif nuclear extract kit (Active Motif, Carlsbad, CA, United States) as mentioned in the given protocol. Suspend the tissues with 1X hypotonic buffer, followed by centrifugation at 12,800 × g for 30 s at 4◦C. Carefully separate the supernatant (cytoplasmic extract) and transfer to a clean pre-chilled tube. The nuclear pellet at the bottom was suspended again with the given lysis buffer and incubated for 30 min in an ice-cold environment. Then centrifuged at 12,800 × g for 10 min at 4◦C. Collect the supernatant (nuclear extract) and transfer to an ice-chilled tube. Both the cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions are ready for Western blotting (Costa et al. 2022).

Western Blot Analysis

Western blot was performed as previously reported with little modification (Alam et al. 2021a, b). Briefly, the protein concentration of mouse hippocampal tissues was measured through a Bio-Rad protein assay Kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories, CA, USA) according to the given protocol of the manufacturer. An equal amount of protein samples in each well were loaded and electrophoresed on 12.5% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS-PAGE GEL) (Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) and transferred to a polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane (Immobilon-PSQ, transfer membrane, Merck Millipore, Burlington, MA, USA). Furthermore, the PVDF membranes were blocked with 5% Skim milk solution (w/v) to avoid nonspecific binding and incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4◦C. On the next day washed with 1×TBST (3 times for 10 min). Next, incubated with secondary antibodies of appropriate source (anti-rabbit/anti-mouse, diluted in 1×TBST) for 1–2 h at room temperature. Now, washed the membrane again with 1×TBST and subjected to enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) reagent (ATTO Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) to measure protein expression level. The results were quantified through Image J software (v. 1.50, NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA).

Brain Tissue Collection and Sample Preparation

First, the mice (n = 4) were anesthetized with ketamine and xylazine and perfused transcardially with 0.1 M phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and 4% neutral buffered formalin. Next, the brain samples were frozen in optimum cutting temperature (O.C.T) compound (Sakura Finetek USA, Inc., CA, USA) and cut into uniform cross-sections with a thickness of 14 μm using a microtome (Leica CM 1860 UV, Burladingen, Germany). For further immunofluorescence study, the brain tissue was stored at −70◦C.

Immunofluorescence Staining

Immunofluorescence staining was performed as described, with minor modifications (Ahmad et al. 2022). The slides were rinsed twice with 0.1 M PBS for 10 min. Apply proteinase K for 6 min and block with 5% normal goat serum (Rabbit/Mouse) for a duration of 1 h. Next, slides were incubated with the required antibodies (diluted with a 1:100 ratio) and placed at 4◦C overnight. On the next day the sections were rinsed with 0.1 M PBS and incubated with secondary tetramethylrhodamine (TRITC)/fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) labeled antibodies for 1–2 h at room temperature. Each slides were rinsed again with 0.1 M PBS for 6 min twice. Finally, apply the nuclear staining dye, DAPI (4, 6-diamidino-2-phenylindole dihydrochloride), and cover with coverslips. The fluorescence intensity of hippocampal tissues was measured and statistically analyzed by via ImageJ software (version 1.50, NIH, https://imagej.nih.gov/ij/, accessed on 5 May 2020, USA).

In Vivo Assays

Ross Oxygen Species (ROS) Assay

Reactive oxygen assay (ROS) was carried out as described previously (Vicente-Gutierrez et al. 2019). Brain hippocampal tissues (n = 4) were homogenized and diluted with ice-cold lock buffer (1:20 ratio) to make the final concentration of 2.5 mg tissue/500 µl. The hippocampal homogenate (0.2 mL), and 10 mL of DCFH-DA (5 mM) were added to the lock’s buffer (1 mL; pH 7.4) and left at room temperature for 15 min to convert DCFH-DA into fluorescent DCF. The spectrophotometer (Promega, Fitchburg, WI, USA) was used with emission at 530 nm and excitation at 484 nm to measure DCF level. Blank sample were used to avoid vehicle signals.

Lipid Peroxidation (LPO) Assay

Lipid peroxidation (LPO) assay is an indicator of oxidative stress. The specific LPO assay kit was utilized to measure the level of free malondialdehyde (MDA) in the mice brain hippocampal tissues homogenates. The assay was carried out as mentioned by the manufacturer. The hippocampal tissues was homogenized in 300 µl of the MDA lysis buffer along with 3 µl BHT and then centrifuged (13,000/10 rpm). Almost 10 mg of protein was precipitated from the homogenized hippocampal sample in 150 µl distill water + 3 µl BHT, adding 1 vol of 2 N perchloric acid, vortexing, and again centrifuge to isolate the precipitated protein. The supernatant from each sample was added to a 96-well plate and the absorbance (at 532 nm) was measured through a microplate analyzer. As a result, the total MDA valve was measured as nmol/mg of protein in each brain homogenate (Sriram et al. 1997).

Glutathione (GSH) Assay

For Glutathione (GSH) assay, hippocampal tissues of mice were homogenized and performed as described previously with minor modification (Bernotiene et al. 2012).

Cresyl Violet (Nissl) Staining

The Nissl staining was carried out as mentioned previously (Muhammad et al. 2019). Each slide was washed with 0.1 M PBS for 15 min. Blocked with 0.5% cresyl violet (Nissl) solution (cresyl violet reagent and few drops of glacial acetic acid) for 15 min at room temperature. Next, washed with distilled water and dehydrated with different grades of ethanol solution. Finally, dip in xylene and apply non-fluorescence mounting media, and cover with a coverslip. The tissues were analyzed via a light microscope and images were quantified through the ImageJ analysis program.

Statistical Analysis

Data was normalized by Shapiro–Wilk normality test prior analysis. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s posthoc testing was used to plot comparisons between each group. The total data are presented as the mean ± SD and were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 8 software (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA, US). The symbol # indicates significance from the saline-injected group, while the symbol * indicates significance from the Cd-injected group. Significance: #p ≤ 0.05, ##p ≤ 0.01, and ###p ≤ 0.001; *p ≤ 0.05, **p ≤ 0.01, and ***p ≤ 0.001.

Results

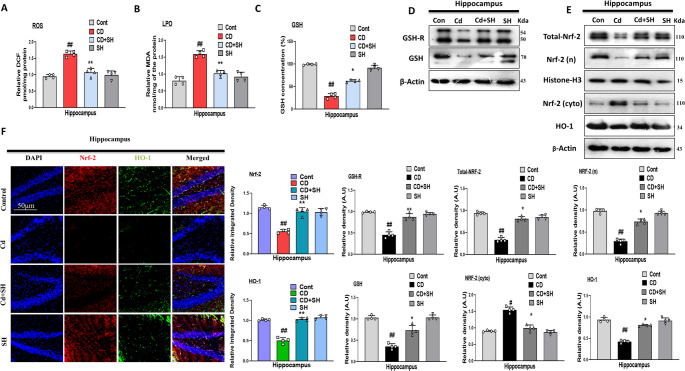

Protective Role of SH against Cd-Induced Oxidative Stress

Glutathione reductase (GSH-R) and Glutathione (GSH), are antioxidant molecules that maintain oxidation-reduction balance in mice brains. To analyze SH antioxidant activity, we measure the level of ROS, LPO, and GSH in different groups of mice hippocampal tissue homogenates. The level of the ROS and LPO were upregulated in the Cd-injected mice group while the level of GSH was downregulated in the Cd-injected mice. Interestingly, the aforementioned biomarkers’ elevated levels were reversed in the Cd-injected + SH-treated group (Fig. 2A, B, and C respectively). Similarly, the expression level of ROS regulators (i.e. GSH-R, GSH, Nrf2, and HO-1) was also evaluated. According to our result, GSH-R, GSH, Nrf2, and HO-1 levels were downregulated in the Cd-injected group, and these levels were maintained in the Cd-injected + SH-treated group. Unlikely, the level of cytoplasmic Nrf2 protein expression was increased in the Cd-injected group and downregulated in the Cd-SH co-treated group (Fig. 2D, E). Moreover, we performed co-staining of Nrf2 and HO-1 which also shown a significant reduction in fluorescence intensity in the Cd-injected mice group, but it was significantly upregulated in the Cd-injected + SH co-treated group (Fig. 2F).

Fig. 2.

Sinomenine Hydrochloride ameliorates Cd-induced oxidative stress in mouse brain; (A, B, C) Reactive oxygen species (ROS), lipid peroxidation (LPO) assay, and Glutathione (GSH) assay respectively; (D, E) Immunoblot analysis (n = 4) of GSH-R, GSH, Nrf2 and HO-1 protein expression in the mouse hippocampus; (F) Immunoflorescence analysis (n = 4) of colocalized Nrf-2 and HO-1 in the experimental group, scale bar 50 μm. All the data were measured in mean ± SD. with respective bar graphs. # Significant difference from the control group, * significant difference from the Cd-injected mouse group. Significance: # p ≤ 0.05, ## p ≤ 0.01, ### p ≤ 0.001; * p ≤ 0.05, ** p ≤ 0.01, *** p ≤ 0.001

SH Inhibits Cd-Induced Activated TLR4, Astrocytes, and Microglial Markers in Mouse Brain

Astrocytes and glial cells are responsible for neuroinflammation via surface receptors such as TLR4. Cd binds with glial surface receptors and initiates inflammatory processes. We examined the TLR4, glial fibrillary acid protein (GFAP), and ionized calcium-binding molecule 1 (Iba-1) levels in the brain’s hippocampus. The biomarkers as mentioned earlier were elevated in case of chronic inflammation followed by disease states. Our western blot result confirmed that there were enhanced expression levels of TLR4, GFAP, and Iba-1 in the Cd-treated mouse group brains, which were significantly lower in the Cd + SH co-treated group (Fig. 3A).

Fig. 3.

Effect of Sinomenine Hydrochloride against Cd-induced neuroinflammation and their downstream signaling target in mouse hippocampus. (A) Immunoblot analysis (n = 4) of TLR4, GFAP, and Iba-1 with respective bar graphs. (B) Immunoblot analysis (n = 4) of p-JNK, p-NFkB, and TNF-α with respective bar graphs. (C, D) Immunofluorescence analysis (n = 4) of GFAP and Iba-1 in mouse hippocampus. The density values are relative to those of the control group and expressed in arbitrary units (AU), magnification 10X, scale bar 50 μm. # Significant difference from the control group, * significant difference from the Cd-injected mouse group. Significance: # p ≤ 0.05, ## p ≤ 0.01, ### p ≤ 0.001; * p ≤ 0.05, ** p ≤ 0.01, *** p ≤ 0.001

SH Regulates P-JNK and its Downstream Targets in Cd-Treated Mouse Brains

To evaluate the expression of p-JNK and its downstream targets in the Cd-treated mouse brains, we performed Western blotting for phospho-c-Jun-N-terminal kinase (p-JNK), p-NF-KB, and tissue necrosis factor (TNF-α) in the brains of the experimental animal. Our results showed significant upregulation in expression levels of various stress and inflammatory biomarkers (i.e., p-JNK, p-NF-KB, and TNF-α) in the Cd-subjected group as compared to the saline-injected control group. Notably, these markers were significantly downregulated in the Cd + SH-cotreated group (Fig. 3B). In addition, we performed staining of GFAP and Iba-1, which also showed an increase in fluorescence intensity in the Cd-injected mice brain. Interestingly, this elevated level of fluorescence decreased in the Cd + SH co-treated mice brains, which showed the possible antiinflammatory activity of SH against Cd-induced inflammation (Fig. 3C and D).

SH May Rescue Cd-Induced Apoptotic Cell Death and Neurodegeneration

Apoptotic cell death is one of the hallmarks of neurodegeneration. To show that apoptotic cell death was reduced by SH, we evaluate the expression level of pro-apoptotic biomarker Bax and the anti-apoptotic biomarker Bcl-2. We observe that the expression level of Bax was upregulated and downregulated protein expression of Bcl-2 in the Cd-injected mice group. This expression level was reversed in the Cd + SH-treated group (Fig. 4A). These effects were further confirmed by the immunofluorescence results, which showed an enhanced expression of Bax in the hippocampus of Cd-treated mice as compared to the control group; interestingly, these biomarkers were significantly reduced in the Cd + SH-cotreated group, as shown in Figure. 4B. Furthermore, these effects were strongly supported by our Cresyl Violet (Nissl) results. The Nissl result showed remarkable shrunken, damaged and fragmentation of neurons in different regions of the hippocampal tissues in the Cd-injected group. This number of neurons shrunken, damaged, and fragmented was observed much less in the Cd + SH co-treated mice group and notably retained cell shapes and integrity. Accumulatively, our results indicated that SH effectively reduced neuronal apoptosis, memory impairment, and neurodegeneration (Fig. 4C).

Fig. 4.

Sinomenine Hydrochloride ameliorates Cd-induced apoptosis; (A) Immunoblot analysis of Bax and Bcl2 in mouse hippocampus with respective bar graphs. (B) Immunofluorescence images of Bax in the hippocampus (n = 4) with respective bar graph. (C) Nissl staining of the DG, CA1, and CA3 regions of the hippocampus of mouse hippocampus (n = 4). Scale bar = 100–50 μm # significantly different from the saline-injected group, * significantly different from the Cd-injected group. Significance: #p ≤ 0.05, ##p ≤ 0.01, and ###p ≤ 0.001; *p ≤ 0.05, **p ≤ 0.01, and ***p ≤ 0.001

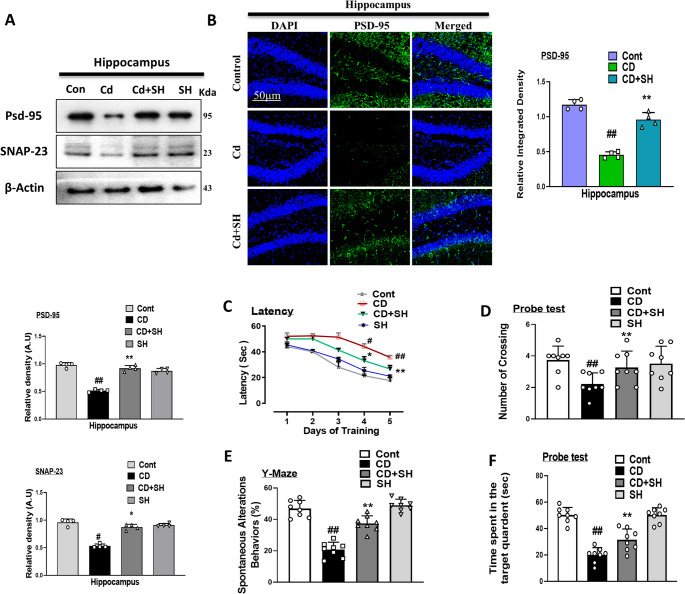

SH Regulates Synaptic and Memory Function

To analyze the effects of SH in Cd-injected mice groups, we evaluated and assessed the various synaptic proteins such as PSD-95 and SNAP-23. The immunoblot result showed a reduced expression of PSD-95 and SNAP-23 in the Cd-injected mice group compared to the control group. Interestingly, the expression of the above-mentioned biomarkers remarkably increased in the cd-injected + SH-treated mice group, showing that synaptotoxicity effects of Cd-injection was reversed (Fig. 5A). In addition, we performed immunofluorescence of PSD-95, which reduces immunofluorescence intensity in the Cd-injected group compared to the control. Notably, immunofluorescence intensity was remarkably elevated in the Cd-injected + SH co-treated mice group (Fig. 5B). Furthermore, we performed a behavioral analysis of our MWM results, which showed that the Cd-injected mice group took a longer time to reach the targeted quadrant than the control mice group. This time duration was decreased in the Cd-injected + SH co-treated mice group. Similarly, Y-MAZE tests were performed to assess the spontaneous alteration of behavior and short-term memory. The Cd-injected mice had a lower percentage of alternation compared to the treated group. Another side percentage of alternation remarkably increased in the Cd-injected + SH co-treated group, showing that SH improves short-term memory impairment in the Cd-injected mice brains (Fig. 5C, D, E, and F respectively).

Fig. 5.

Effect of Sinomenine Hydrochloride ameliorates Cd-induced synaptic damage and memory impairment; (A) Immunoblot results of PSD-95 and SNAP-23 (n = 4) in the hippocampus of mice. (B) Immunofluorescence images of PSD-95 in hippocampus (n = 4) with respective bar graph. (C) Mean time (s) taken to escape during the training days. (D) The average number of crossings at the hidden platform during the probe test of the MWM test. (E) Spontaneous alteration behavior percentage of the mice during the Y-maze test. (F) Time spent in the platform quadrant, where the hidden platform was placed during the trial session. All the data were measured in mean ± SD. (n = 8 per group of animals for behavioral study). # Significant difference from the saline-injected group, * significant difference from the Cd-injected group. Significance: #p ≤ 0.05, ##p ≤ 0.01, and ###p ≤ 0.001; *p ≤ 0.05, **p ≤ 0.01, and ***p ≤ 0.001

Discussion

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is one of the forms of dementia with unknown causes and ideal therapy. Therefore, a treatment medium with significant curative effects and few side effects eagerly awaits development (Honig and Boyd 2013). Oxidative stress, neuroinflammation and apoptosis combine leads to neurodegeneration and cognitive impairment. Neurological diseases such as AD and PD may affect the life style and quality of patient by limiting self-independence, and finally lead to death of an individual. The cause and risk factors are still unknown of AD, PD and other relatable neurological diseases. Literature review reveals that some of the endogenous proteomic (Aβ1−42 and p-tau) and exogenous (cadmium, LPS, D-galactose) substances undergoes for AD-like disease. Mitochondria is powerhouse of cell and maintain cellular energy system by regulating metabolism. Natural substances such as alkaloid terpenoids and flavonoids are primary sources of preventing and curing neurological diseases (Küpeli Akkol et al. 2021). In current study, we investigated the neuroprotective effects of Sinomenine hydrochloride (SH) verses cadmium-induced oxidative stress, neuroinflammation-mediated neurodegeneration, and memory impairments in mouse brain hippocampus. SH is one of the natural alkaloids having structural similarity to narcotic analgesic morphine, isolated from Sinomenium acutum, having anti-inflammatory, immunomodulatory, hypnotic, and strong analgesic properties (Lu et al. 2013). SH may potentially treat neurodegenerative diseases by suppressing activated glial cells and traumatic brain injury (TBI) (Fu et al. 2018). However, the role of SH remains unclear in cd-induced neurodegeneration.

In the current study, a well-organized and classical animal AD model induced by intraperitoneal Cd injection induced mitochondrial oxidative stress, neuroinflammation, and memory impairments. Previous studies highlighted that mitochondrial stress is a main player in cardiovascular and neurodegenerative diseases, especially AD and PD (Elfawy and Das 2019). Chronic oral administration of SH may inhibit Cd-induced mitochondrial oxidative stress by regulating Glutathione reductase (GR) and NRF2/HO-1. Notably, our western and confocal microscopy results revealed that both the expression and intensity levels of NRF2 and HO-1 were decreased in only the Cd-injected group, which recovered in the Cd-injected + SH co-treated group.

Moreover, activated glial and immune cells are involved in phosphorylation of NF-kB and having contributed role in neuroinflammation. Therefore, the expression level of TLR4, GFAP, Iba-1 and p-NF-kB in cd-injected mice hippocampus. SH has strong anti-inflammatory activity via regulating effects against p-JNK, TLR4, p-NF-kB, and TNF release (Zhao et al. 2015). Extensive oxidative stress followed by neuroinflammation and induced apoptosis at the level of rodent’s brains (L.-L. Guo et al. 2013). Moreover, strong evidence suggests that the activation of JNK may cause the activation of inflammatory processes in vivo (Anfinogenova et al. 2020). In our results, the phosphorylation of JNK, NF-kB, and TNF-α was increased in the mouse brains; the expression levels of these proteins were markedly reduced with the administration of SH. The inhibitory effects of SH against activated JNK, p-NF-kB, and TNF followed previous studies (Wang et al. 2012). Another factor, s apoptosis also takes part in neurodegeneration (Radi et al. 2014). The apoptotic marker Bax was upregulated and the anti-apoptotic marker Bcl2 was downregulated in the Cd-treated group, which may be partly due to stress kinases, especially p-JNK activation (Ham et al. 2000). Triggering of TLR4 glial cells surface receptor leads to activation of astromicroglial cells inducing apoptosis cell death, and neurodegeneration (Ali et al. 2020; Jimenez et al. 2008). These effects were reversed by oral administration of SH. Heavy metals like Cd may also affect synaptic and memory functions (Karri et al. 2016). The MWM and Y MAZE behavioral tests were performed to explore the learning and memory activity. The mice receiving Cd + SH-injection show improvement in learning behavior and spontaneous alternation as compared to the Cd-treated group. These findings suggest that SH can ameliorate the short-term memory dysfunction in the Cd-injected mice group. The therapeutic effect of orally administered SH on synaptic and memory dysfunction was also evaluated. The expression level of synaptic biomarkers was upregulated in SH-cotreated mice brains as compared to the Cd-injected group. In addition, the cresyl violet staining result strongly supports our data, and the Cd-injected mice hippocampus showed neuronal cell shrinkage and fragmentation in DG, CA1 and CA3 regions. The aforementioned damages were limited in CD + SH co-treated mice group.

Collectively, SH may counteract Cd-induced mitochondrial oxidative stress, neuroinflammation, and neuronal apoptotic cell death to improve synaptic and memory impairment. The antioxidant effect of SH inhibits cd-induced neuroinflammation and neuronal loss. From our results, we suggested that SH exhibits a multi-targeted effect against Cd-induced neurodegeneration in mice brain.

Conclusion

In conclusion, SH exhibits strong antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and anti-apoptotic effects, and it was also shown to improve neuronal survival and memory deficits in the CD-injected mouse model. Based on current and previous studies, SH may protect mice’s brains against Cd-induced ROS and glial-cell-mediated neuronal cell loss and memory dysfunction by regulating the GSH and NRF2/HO-1 pathways. Our results may be helpful for the advancement of new therapeutic approaches for the management of AD-like conditions (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

The proposed neuroprotective mechanism of Sinomenine Hydrochloride against Cd-induced oxidative stress, neuroinflammation, apoptosis, and cognitive impairment in the mouse brain

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author Contributions

Waqar Ali: Writing – original draft, Visualization, Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation. Kyonghwan Choe: Investigation, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation. Inayat Ur Rehman: Investigation, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Data curation. Hyun Young Park: Resources, Writing – review & editing. Sihoon Jang: Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. Safi Ullah: Software, Resources, Investigation. Tae Ju Park: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition, Data curation, Conceptualization. Myeong Ok Kim: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Software, Resources, Project administration, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization.

Funding

the Bio & Medical Program of the National Research Foundation (NRF), funded by the Korean Government (MSIT) (RS-2024-00441331), supported this research.

Data Availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

the experimental animals were handled by the Animal Ethics Committee (IACUC) guidelines issued by the Division of Applied Life Sciences, Department of Biology at Gyeongsang National University, Republic of Korea (Approval ID: 125, Code: GNU-200331-M0020). Our experiments were undertaken to reduce the mouse’s number and minimize their pain or discomfort.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Waqar Ali and Kyonghwan Choe contributed equally.

Contributor Information

Tae Ju Park, Email: taeju.park@einsteinmed.edu.

Myeong Ok Kim, Email: mokim@gnu.ac.kr.

Refrences

- Agostinho P, Cunha A, R., Oliveira C (2010) Neuroinflammation, oxidative stress and the pathogenesis of alzheimer’s disease. Curr Pharm Design 16(25):2766–2778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad R, Khan A, Rehman IU, Lee HJ, Khan I, Kim MO (2022) Lupeol treatment attenuates activation of glial cells and oxidative-stress-mediated neuropathology in mouse model of traumatic brain injury. Int J Mol Sci 23(11):6086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al Olayan EM, Aloufi AS, AlAmri OD, Ola H, Moneim AEA (2020) Protocatechuic acid mitigates cadmium-induced neurotoxicity in rats: role of oxidative stress, inflammation and apoptosis. Sci Total Environ 723:137969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alam S-I, Kim M-W, Shah FA, Saeed K, Ullah R, Kim M-O (2021a) Alpha-linolenic acid impedes cadmium-induced oxidative stress, neuroinflammation, and neurodegeneration in mouse brain. Cells 10(9):2274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alam SI, Jo MG, Park TJ, Ullah R, Ahmad S, Rehman SU, Kim MO (2021b) Quinpirole-mediated regulation of dopamine d2 receptors inhibits glial cell-induced neuroinflammation in cortex and striatum after brain injury. Biomedicines 9(1):47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali W, Ikram M, Park HY, Jo MG, Ullah R, Ahmad S, Kim MO (2020) Oral administration of alpha linoleic acid rescues Aβ-induced glia-mediated neuroinflammation and cognitive dysfunction in C57BL/6 N mice. Cells 9(3):667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali W, Choe K, Park JS, Ahmad R, Park HY, Kang MH, Kim MO (2024) Kojic acid reverses LPS-induced neuroinflammation and cognitive impairment by regulating the TLR4/NF-κB signaling pathway. Front Pharmacol 15:1443552 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aljelehawy QHA (2022) Effects of the lead, cadmium, manganese heavy metals, and magnesium oxide nanoparticles on nerve cell function in alzheimer’s and parkinson’s diseases. Cent Asian J Med Pharm Sci Innov 2:25–36 [Google Scholar]

- Anfinogenova ND, Quinn MT, Schepetkin IA, Atochin DN (2020) Alarmins and c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) signaling in neuroinflammation. Cells 9(11):2350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aoyama K (2021) Glutathione in the brain. Int J Mol Sci 22(9):5010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arruebarrena MA, Hawe CT, Lee YM, Branco RC (2023) Mechanisms of cadmium neurotoxicity. Int J Mol Sci 24(23):16558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernotiene R, Ivanoviene L, Sadauskiene I, Liekis A, Ivanov L (2012) Influence of cadmium ions on the antioxidant status and lipid peroxidation in mouse liver: protective effects of zinc and selenite ions. Trace Elem Electrolytes 29(2):137–142 [Google Scholar]

- Branca JJ, Fiorillo C, Carrino D, Paternostro F, Taddei N, Gulisano M, Becatti M (2020) Cadmium-induced oxidative stress: focus on the central nervous system. Antioxidants 9(6):492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakravorty A, Jetto CT, Manjithaya R (2019) Dysfunctional mitochondria and mitophagy as drivers of Alzheimer’s disease pathogenesis. Front Aging Neurosci 11:311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Wang Y, Jiao F-Z, Yang F, Li X, Wang L-W (2020) Sinomenine attenuates acetaminophen-induced acute liver injury by decreasing oxidative stress and inflammatory response via regulating TGF-β/Smad pathway in vitro and in vivo. Drug Des Devel Ther. 10.2147/DDDT.S248823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa RM, Alves-Lopes R, Alves JV, Servian CP, Mestriner FL, Carneiro FS, Tostes RC (2022) Testosterone contributes to vascular dysfunction in young mice fed a high fat diet by promoting nuclear factor E2–related factor 2 downregulation and oxidative stress. Front Physiol 13:837603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elfawy HA, Das B (2019) Crosstalk between mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress, and age related neurodegenerative disease: etiologies and therapeutic strategies. Life Sci 218:165–184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emir UE, Raatz S, McPherson S, Hodges JS, Torkelson C, Tawfik P, Terpstra M (2011) Noninvasive quantification of ascorbate and glutathione concentration in the elderly human brain. NMR Biomed 24(7):888–894 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira MES, de Vasconcelos AS, da Costa Vilhena T, da Silva TL, da Silva Barbosa A, Gomes ARQ, Percário S (2015) Oxidative stress in Alzheimer’s disease: should we keep trying antioxidant therapies? Cell Mol Neurobiol 35:595–614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu C, Wang Q, Zhai X, Gao J (2018) Sinomenine reduces neuronal cell apoptosis in mice after traumatic brain injury via its effect on mitochondrial pathway. Drug Des Devel Ther. 10.2147/DDDT.S154391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganie SA, Dar TA, Bhat AH, Dar KB, Anees S, Zargar MA, Masood A (2016) Melatonin: a potential anti-oxidant therapeutic agent for mitochondrial dysfunctions and related disorders. Rejuven Res 19(1):21–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Górska A, Markiewicz-Gospodarek A, Markiewicz R, Chilimoniuk Z, Borowski B, Trubalski M, Czarnek K (2023) Distribution of iron, copper, zinc and cadmium in glia, their influence on glial cells and relationship with neurodegenerative diseases. Brain Sci 13(6):911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guedes JR, Lao T, Cardoso AL, Khoury E, J (2018) Roles of microglial and monocyte chemokines and their receptors in regulating alzheimer’s disease-associated amyloid-β and Tau pathologies. Front Neurol 9:549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo C, Sun L, Chen X, Zhang D (2013a) Oxidative stress, mitochondrial damage and neurodegenerative diseases. Neural Regen Res 8(21):2003–2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo L-L, Guan Z-Z, Huang Y, Wang Y-L, Shi J-S (2013b) The neurotoxicity of β-amyloid peptide toward rat brain is associated with enhanced oxidative stress, inflammation and apoptosis, all of which can be attenuated by scutellarin. Exp Toxicol Pathol 65(5):579–584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ham J, Eilers A, Whitfield J, Neame SJ, Shah B (2000) C-Jun and the transcriptional control of neuronal apoptosis. Biochem Pharmacol 60(8):1015–1021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honig LS, Boyd CD (2013) Treatment of Alzheimer’s disease: current management and experimental therapeutics. Curr Translational Geriatr Experimental Gerontol Rep 2:174–181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang W, Fan W, Gao T, Li T, Yin Z, Guo H, Jiang J-D (2020) Analgesic mechanism of Sinomenine against chronic pain. Pain Res Manage 2020(1):1876862 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez S, Baglietto-Vargas D, Caballero C, Moreno-Gonzalez I, Torres M, Sanchez-Varo R, Vitorica J (2008) Inflammatory response in the hippocampus of PS1M146L/APP751SL mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease: age-dependent switch in the microglial phenotype from alternative to classic. J Neurosci 28(45):11650–11661 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karri V, Schuhmacher M, Kumar V (2016) Heavy metals (Pb, cd, as and MeHg) as risk factors for cognitive dysfunction: a general review of metal mixture mechanism in brain. Environ Toxicol Pharmacol 48:203–213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan A, Ikram M, Muhammad T, Park J, Kim MO (2019) Caffeine modulates cadmium-induced oxidative stress, neuroinflammation, and cognitive impairments by regulating Nrf-2/HO-1 in vivo and in vitro. J Clin Med 8(5):680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim K (2021) Glutathione in the nervous system as a potential therapeutic target to control the development and progression of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Antioxidants 10(7):1011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Küpeli Akkol E, Tatlı Çankaya I, Şeker Karatoprak G, Carpar E, Sobarzo-Sánchez E, Capasso R (2021) Natural compounds as medical strategies in the prevention and treatment of psychiatric disorders seen in neurological diseases. Front Pharmacol 12:669638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Cai W, Ai Z, Xue C, Cao R, Dong N (2023) Protective effects of Sinomenine hydrochloride on lead-induced oxidative stress, inflammation, and apoptosis in mouse liver. Environ Sci Pollut Res 30(3):7510–7521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao K, Su X, Lei K, Liu Z, Lu L, Wu Q, Wang M (2021) Sinomenine protects bone from destruction to ameliorate arthritis via activating p62Thr269/Ser272-Keap1-Nrf2 feedback loop. Biomed Pharmacother 135:111195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin MT, Beal MF (2006) Mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress in neurodegenerative diseases. Nature 443(7113):787–795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu X-L, Zeng J, Chen Y-L, He P-M, Wen M-X, Ren M-D, He S-Χ (2013) Sinomenine hydrochloride inhibits human hepatocellular carcinoma cell growth in vitro and in vivo: involvement of cell cycle arrest and apoptosis induction. Int J Oncol 42(1):229–238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muhammad T, Ikram M, Ullah R, Rehman SU, Kim MO (2019) Hesperetin, a citrus flavonoid, attenuates LPS-induced neuroinflammation, apoptosis and memory impairments by modulating TLR4/NF-κB signaling. Nutrients 11(3):648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni H, Liu M, Cao M, Zhang L, Zhao Y, Yi L, Du Q (2024) Sinomenine regulates the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway to inhibit TLR4/NF-κB pathway and protect the homeostasis in brain and gut in scopolamine-induced Alzheimer’s disease mice. Biomed Pharmacother 171:116190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plascencia-Villa G, Perry G (2021) Preventive and therapeutic strategies in Alzheimer’s disease: focus on oxidative stress, redox metals, and ferroptosis. Antioxid Redox Signal 34(8):591–610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin T, Yin S, Yang J, Zhang Q, Liu Y, Huang F, Cao W (2016) Sinomenine attenuates renal fibrosis through Nrf2-mediated inhibition of oxidative stress and TGFβ signaling. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 304:1–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radi E, Formichi P, Battisti C, Federico A (2014) Apoptosis and oxidative stress in neurodegenerative diseases. J Alzheimers Dis 42(s3):S125–S152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rezaei K, Mastali G, Abbasgholinejad E, Bafrani MA, Shahmohammadi A, Sadri Z, Zahed MA (2024) Cadmium neurotoxicity: insights into behavioral effect and neurodegenerative diseases. Chemosphere. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2024.143180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh A, Kukreti R, Saso L, Kukreti S (2019) Oxidative stress: a key modulator in neurodegenerative diseases. Molecules 24(8):1583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sriram K, Pai KS, Boyd MR, Ravindranath V (1997) Evidence for generation of oxidative stress in brain by MPTP: in vitro and in vivo studies in mice. Brain Res 749(1):44–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsao C-H, Wu K-Y, Su NC, Edwards A, Huang G-J (2023) The influence of sex difference on behavior and adult hippocampal neurogenesis in C57BL/6 mice. Sci Rep 13(1):17297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vicente-Gutierrez C, Bonora N, Bobo-Jimenez V, Jimenez-Blasco D, Lopez-Fabuel I, Fernandez E, Almeida A (2019) Astrocytic mitochondrial ROS modulate brain metabolism and mouse behaviour. Nat Metab 1(2):201–211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L-W, Tu Y-F, Huang C-C, Ho C-J (2012) JNK signaling is the shared pathway linking neuroinflammation, blood–brain barrier disruption, and oligodendroglial apoptosis in the white matter injury of the immature brain. J Neuroinflamm 9:1–17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Z, Xiao J, Wang J, Dong W, Peng Z, An D (2015) Anti-inflammatory effects of novel Sinomenine derivatives. Int Immunopharmacol 29(2):354–360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.