Abstract

The intracellular triphosphorylation and plasma pharmacokinetics of lamivudine (3TC), stavudine (d4T), and zidovudine (ZDV) were assessed in a pharmacokinetic substudy, in 56 human immunodeficiency virus-hepatitis C virus (HIV-HCV) coinfected patients receiving peginterferon alfa-2a (40KD) 180 μg/week plus either placebo or ribavirin (RBV) 800 mg/day in the AIDS PEGASYS Ribavirin International Coinfection Trial. There were no significant differences between patients treated with RBV and placebo in plasma pharmacokinetics parameters for the nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs) at steady state (weeks 8 to 12): ratios of least squares mean of area under the plasma concentration-time curve (AUC0-12 h) were 1.17 (95% confidence interval, 0.91 to 1.51) for 3TC, 1.44 (95% confidence interval, 0.58 to 3.60) for d4T and 0.85 (95% confidence interval, 0.50 to 1.45) for ZDV, and ratios of least squares mean plasma Cmax were 1.33 (95% confidence interval, 0.99 to 1.78), 1.06 (95% confidence interval, 0.68 to 1.65), and 0.84 (95% confidence interval, 0.46 to 1.53), respectively. Concentrations of NRTI triphosphate (TP) metabolites in relation to those of the triphosphates of endogenous deoxythymidine-triphosphate (dTTP) and deoxcytidine-triphosphate (dCTP) were similar in the RBV and placebo groups. Differences (RBV to placebo) in least squares mean ratios of AUC0-12 h at steady state were 0.274 (95% confidence interval, −0.37 to 0.91) for 3TC-TP:dCTP, 0.009 (95% confidence interval, −0.06 to 0.08) for d4T-TP:dTTP, and −0.081 (95% confidence interval, −0.40 to 0.24) for ZDV-TP:dTTP. RBV did not adversely affect HIV-1 replication. In summary, RBV 800 mg/day administered in combination with peginterferon alfa-2a (40KD) does not significantly affect the intracellular phosphorylation or plasma pharmacokinetics of 3TC, d4T, and ZDV in HIV-HCV-coinfected patients.

Since the introduction of potent antiretroviral therapy, the life expectancy of patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection has increased significantly. Coinfection with hepatitis C virus (HCV) in patients with HIV infection is common, and liver disease has emerged as a major cause of morbidity and mortality in HIV-HCV-coinfected patients (5, 39). It has been estimated that approximately 250,000 persons in the United States have HIV-HCV coinfection, which amounts to 10% of the total number of patients with chronic hepatitis C (2, 36), and approximately one-third of HIV-infected persons in the United States and Europe have HCV coinfection (32). Effective treatment for HCV is urgently needed in this population.

Sustained virological response rates of 52 to 63% have been obtained after 48 weeks of treatment with pegylated interferon plus ribavirin (RBV) in pivotal phase III studies in patients with HCV monoinfection (10, 14, 26, 43). As a result, this combination is recognized as the treatment of choice in this population (1, 39, 40).

RBV significantly enhances the efficacy of interferon-based therapies in the treatment of HCV. Whether RBV interferes with the pharmacokinetics of antiretroviral drugs, however, is an important and, as yet, unanswered question relevant to the treatment of HCV in HIV-infected persons. Concerns have also been raised regarding the safety of RBV in patients with HIV-HCV coinfection receiving antiretroviral therapy (39).

RBV inhibits IMP dehydrogenase and thereby alters various intracellular nucleotide pools. The drug reduces in vitro phosphorylation of certain pyrimidine analogue nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs) (15, 19, 38, 42). The antiviral activity of NRTIs relies on conversion to pharmacologically active triphosphorylated moieties that competitively inhibit reverse transcriptase. The clinical significance of altered in vitro phosphorylation of NRTIs by RBV requires clarification because combination therapy with pegylated interferon plus RBV offers the best hope of a cure for HCV in patients with HIV coinfection (39).

In the randomized, multinational AIDS PEGASYS RBV International Coinfection Trial (APRICOT), the combination of peginterferon alfa-2a (40KD) plus RBV produced an overall SVR of 40%, which was significantly greater than that achieved with peginterferon alfa-2a (40KD) monotherapy (20%, P < 0.0001) or conventional interferon plus RBV (12%, P < 0.0001) (41). A nested pharmacokinetic study was incorporated into the design of APRICOT to determine the impact of RBV on the intracellular phosphorylation and plasma pharmacokinetics of NRTIs, the results of which are reported in this paper.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Objectives.

The primary objective of the study was to examine the effect of RBV on the intracellular phosphorylation of lamivudine (3TC), stavudine (d4T), and zidovudine (ZDV) using a parallel comparison between the treatment arm and the placebo arm. Secondary objectives included examination of the plasma pharmacokinetics of 3TC, d4T, and ZDV before and after 8 to 12 weeks of study treatment and a description of the pharmacokinetics of RBV after 8 to 12 weeks of twice daily administration.

Study design.

The study design used a parallel comparison between the patients receiving peginterferon alfa-2a (40KD) plus RBV and patients receiving peginterferon alfa-2a (40KD) plus placebo. However, as it is known that the concentrations of intracellular NRTI phosphates are highly variable (4, 17, 24, 28, 31, 33, 34, 38), baseline values prior to the study or placebo administration were also collected for each of the arms (to measure the differences in the two arms at baseline). Furthermore, this design was chosen as previous data have suggested that intracellular NRTI phosphate levels change longitudinally with time (17). Hence, a parallel-controlled study design was used to avoid false positive results from such changes.

Patients.

Patients eligible for APRICOT were adults aged ≥18 years with HIV-HCV coinfection who had not received previous antiviral treatment for HCV. HCV infection was confirmed by the presence of anti-HCV antibodies and HCV RNA (>600 IU/ml; COBAS AMPLICOR HCV MONITOR Test, v2.0, Roche Diagnostics) in serum; HIV-1 infection was confirmed by detection of anti-HIV antibodies or HIV-1 RNA in serum (AMPLICOR HIV-1 MONITOR Test, v1.5). Patients were also required to have elevated serum alanine aminotransferase levels documented on ≥2 occasions within the previous 12 months, liver biopsy findings obtained within the previous 15 months consistent with a diagnosis of chronic hepatitis C, and compensated liver disease (Child Pugh grade A). Individuals with CD4+ cell counts ≥200/μl were eligible independent of their serum HIV-1 RNA level; those with CD4+ cell counts of 100 to 199 μl were eligible only if their serum HIV-1 RNA level was < 5000 copies/ml. Patients with serum creatinine >1.5 times the upper limit of normal were excluded. The complete inclusion and exclusion criteria and study design of APRICOT have been published elsewhere (41).

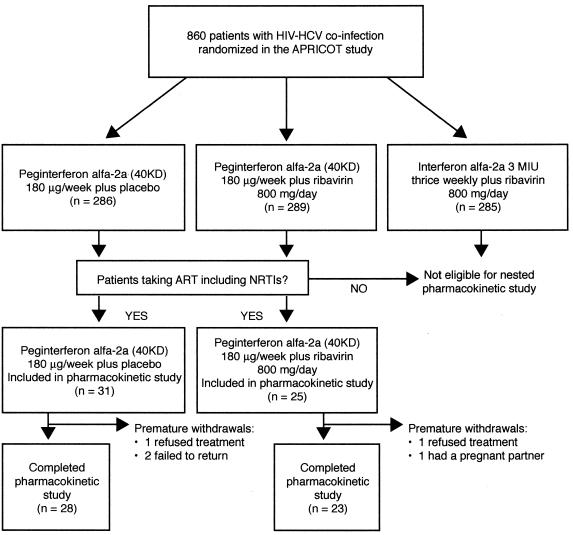

To be eligible for the pharmacokinetic substudy, patients in APRICOT had to fulfill two criteria. Firstly, they had to be randomized to peginterferon alfa-2a (40KD) (PEGASYS, Roche) 180 μg once weekly plus either oral RBV (COPEGUS, Roche) 400 mg or oral placebo twice daily. Patients and investigators were blinded to the use of placebo and RBV in these groups. Secondly, patients had to be receiving antiretroviral therapy at baseline that included lamivudine plus either zidovudine or stavudine (Fig. 1). The particular antiretroviral therapy regimen must have been at stable dosages for at least the previous 6 weeks and with no changes expected for the 12 weeks of the substudy.

FIG. 1.

Flow of patients through the trial.

Patients randomized to conventional interferon plus RBV in APRICOT (the third arm of APRICOT) and those not on antiretroviral therapy at baseline were excluded from the pharmacokinetic study. Concomitant treatment with rifampin, rifabutin, pyrazinamide, isoniazid, ganciclovir, thalidomide, oxymetholone, immunomodulatory treatments, or systemic antiviral agents as adjuvant treatment for chronic hepatitis C was prohibited. No patient concomitantly received any agent that has been shown to influence the endogenous phosphate pool, such as hydroxyurea or mycophenolate.

The APRICOT trial protocol allowed reductions in the dose of RBV and/or peginterferon alfa-2a (40KD) for the management of adverse events, according to a predefined protocol and at the discretion of the investigator (41). Stepwise dose modifications of peginterferon alfa-2a to 135, 90, or 45 μg/week, and of RBV to 600 mg/day were allowed. A return to the initial dose was permitted if the event improved or resolved.

All patients included in the substudy had to agree prior to randomization that they were willing to participate in the substudy. If patients agreed, they were required to provide written informed consent for this substudy. The study protocol was approved by Institutional Review Boards at participating centers in the United States and Spain. The study was conducted in accord with the Declaration of Helsinki and Guidelines for Good Clinical Practice. The study was sponsored by Roche, Nutley, NJ.

Sample collection and analytical methods.

(i) Isolation of peripheral blood mononuclear cells and quantification of intracellular concentrations of triphosphorylated nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs). Serial blood samples (32 ml) for pharmacokinetic analyses were collected in CPT tubes (Becton Dickinson 36-2753) immediately before and 2, 4, 6, 8, and 12 h after the morning dose of 3TC, d4T, and/or ZDV at baseline and at steady state (Fig. 1). Baseline pharmacokinetic samples were collected prior to starting peginterferon alfa-2a (40KD) plus ribavirin treatment and steady state assessments were carried between approximately 8 and 12 weeks of treatment.

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated within two hours of blood collection. The collection tubes were centrifuged for 30 min at 1500 G. The two upper layers, the plasma layer and cell layer, contained mononuclear cells and platelets; the contents above the separation in each tube were gently mixed by inversion and poured into two 15-ml centrifuge tubes, which were spun at 600 G for 10 min. The supernatant was discarded and the pellet resuspended in 1.25 ml phosphate buffered saline. A 10-μl aliquot was removed for cell counting in a hematocytometer. The tubes were centrifuged again at 600 G for 10 min and the supernatant discarded. Phosphorylated metabolites were then isolated using previously validated double extraction methodology (22). In brief, cells were resuspended in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4) and an aliquot of 100% methanol was added and left for a minimum of two hours to extract the phosphorylated metabolites. The samples were then centrifuged at 600 G for 10 min to remove cellular debris. The methanol extracts were then dried by rotary evaporation and shipped from study sites to the University of Liverpool, where template primer extension assays were performed.

The template primer extension assays have been described in detail elsewhere (16, 18, 22, 23, 30). Briefly, the three triphosphate anabolites of interest (3TC-TP, ZDV-TP, or d4T-TP) as well as endogenous deoxythymidine-triphosphate (dTTP) and deoxcytidine triphosphate (dCTP) present in PBMCs were extracted with methanol, dried by rotary evaporation, and reextracted with perchloric acid (0.4 N; 200 μl; 4°C). These extracts were analyzed using enzymatic assays with specific template primers. To quantify the amount of NRTI triphosphate present, the enzymatic assays measure the degree to which it competitively inhibits the incorporation of known amounts of a radiolabeled form of the NRTI triphosphate (catalyzed by HIV-1 reverse transcriptase) into the primer. Concentrations of endogenous nucleoside triphosphates (dCTP and dTTP) are determined in the same way but using a different primer. By comparing the radioactivity incorporated in the extended synthetic template primers with standards of known concentration, concentrations of each triphosphate anabolite (from the NRTIs and endogenous nucleosides) were calculated.

The concentrations of the nucleoside analogue triphosphates and of the endogenous nucleoside-triphosphates were normalized to units of 106 cells. Assay validation data have been described previously (22, 35).

(ii) Quantification of nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors and RBV in plasma. Plasma concentrations of ZDV, d4T, 3TC, and RBV were determined with validated liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC/MS/MS) assays. Plasma from patient blood samples was frozen after collection and transported to the laboratory (Cedra Corporation, Austin, Texas) for analysis. Samples were allowed to thaw and then a 250 μl aliquot was withdrawn for analysis. TenμL of the internal standard solution for 3TC (zalcitabine, 2′,3′-dideoxycytidine, DDC), or for d4T and ZDV (3′-azido-2′,3′-dideoxyuridine, 3-ADU) and 1.5 ml of ammonium acetate were added. The sample was then placed on a solid phase extraction cartridge (Strata C18-E, Phenomenex), which was washed twice with water (2 × 1.0 ml) and hexane (1.0 ml) before being eluted twice with methanol (2 × 1.0 ml). Extraction recovery for the NRTIs ranged from 93.1% to 114%.

Samples were evaporated to dryness and reconstituted with acetonitrile and water (4:1 mixture). The samples were injected onto a PVA-Sil 5 micron column (4.6 by 100 mm) equipped with a SCIEX API 3000 electrospray ionization (ESI) tandem mass spectrometry system in multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) mode. The mobile phase was a mixture of acetonitrile, methanol, water and formic acid (480:10:10:5). The peak area of the mass to charge (m/z) 230→112 3TC product ion was measured against the peak area of the m/z 212→112 product ion of the internal standard (DDC), and the m/z 225→127 d4T product ion and the m/z 268→127 ZDV product ion were measured against the peak area of the m/z 254→113 product ion of the internal standard (3-ADU). The range, of quantitation was 5 to 500 ng/ml for 3TC, 50 to 5000 ng/ml for d4T and 10 to 1000 ng/ml for ZDV. Data were analyzed with MacQuan software (v. 1.6).

RBV was also quantified by LC/MS/MS. Plasma samples from heparinized blood were frozen after collection and transported to the laboratory (Huntingdon Life Sciences Inc. East Millstone, NJ) for analysis. Samples were allowed to thaw at room temperature and a 100 μl aliquot was transferred to a 2-ml Eppendorf tube. Fifty microliters of water and 50 μl of internal standard solution (RBV 13C2) and 300 μl of acetonitrile were added and the tube was centrifuged at 13000 rpm for 10 min. A total of 200 μl of supernatant was transferred to culture tubes (16 by 100 mm) and evaporated to dryness. The material was reconstituted with 200 μl of the mobile phase (75% acetonitrile, 10% methanol, 15% ammonium acetate [vol/vol]) and injected into the LC/MS/MS system (Perkin Elmer API 365 mass spectrometer with a turbo ion spray interface) equipped with a 150 × 4.6 mm Lichrosorb NH2 analytical column with the mobile phase running at a flow rate of 1 ml/min (Keystone Scientific Inc.). Sample introduction was through electrospray ionization (ESI) in the positive ion mode. The ion transitions for the peak area quantitation were 245.1→113.0 and 247.1→115.1, for RBV and RBV-13C2, respectively. The range, of detection for the assay was 5.0 to 1280 ng/ml. Data were analyzed with MassChrom software (v. 1.1.2)

Quantification was performed using linear regression least squares analyses generated from fortified plasma calibration standards (ZDV, d4T, and RBV [obtained from Sigma; ≥99% purity] and 3TC [obtained from Custom Synthesis Services; 99% purity]), prepared immediately prior to each run. Precision and accuracy of the standard curves, obtained by treating peak areas of the calibration standards as unknowns and entering them into the derived equation for least squares resulted in coefficients of variation ranging from 0.6 to 12.2% and absolute deviation from the mean from the theoretical concentration of 0.5 to 5.6%. Precision and accuracy at the lower limit of quantitation were verified by analysis of six samples at the lowest concentration. In all instances, both the coefficients of variation and the absolute deviation from the mean from the theoretical concentration were ≤12%. Short-term stability of the NRTIs in human plasma showed stability samples were within ±15% of their theoretical concentrations.

Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic assessments and data analyses: plasma and intracellular parameters.

Patients included in the pharmacokinetic analysis had received at least one dose of either study drug and completed the baseline pharmacokinetic assessments.

Plasma and intracellular pharmacokinetic parameters were estimated from individual plasma and intracellular concentration-time profiles by noncompartmental methods using WinNonLin Pro (version 4.1). Intracellular and plasma area under the concentration-time curve between 0 and 12 h after drug administration (AUC0-12 h) values at baseline and at steady state (weeks 8 to 12) were calculated using the linear trapezoidal rule. Individual plasma or intracellular concentration values and actual sampling times were used in calculations.

Intracellular metabolites of ZDV, 3TC, and d4T were expressed using the ratio of the AUC0-12 h in PBMCs of the triphosphate anabolites of the drugs to the appropriate endogenous nucleoside triphosphates (dCTP for 3TC and dTTP for d4T and ZDV). Plasma pharmacokinetic parameters assessed were the AUC0-12 h and maximum plasma concentration (Cmax) for ZDV, 3TC, d4T, and RBV. Serum HIV-1 RNA levels and CD4+ cell counts were also assessed. Geometric least squares means were used to summarize log-transformed variables (AUC0-12 h and Cmax).

Statistical analysis.

Prior to this study the intrapatient variability in the ratio of AUC0-12 h of nucleoside analogue triphosphates to the AUC0-12 h of endogenous nucleoside triphosphates was unknown; therefore, it was not possible to conduct a formal sample size calculation. However, data from two previous studies (3, 16) (with a standard deviation of approximately 50% for intracellular concentrations of ZDVTP), suggested that approximately 20 patients would give a power of 80% to detect a difference of 30% in the intracellular concentrations of drug and endogenous triphosphates. To ensure that we obtained data for each drug in approximately 20 patients, a total enrollment of approximately 60 patients was planned.

Efficacy between the two groups was assessed in the pharmacokinetic population (defined at the design of the trial as patients who received at least one dose of either study drug and had completed the baseline pharmacokinetic assessments). Analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was used to analyze the effect of RBV on primary and secondary pharmacokinetic parameters. The statistical analysis (ANCOVA) included the baseline for both placebo and treatment as covariates. Therefore the analysis tested the true treatment-related effect at steady state by adjusting the baseline and intrapatient difference in both arms. Consequently, statistical analyses of pharmacokinetic parameters were only performed for patients who had both baseline and steady-state values. The ratio of AUCs within the same time frame was considered to be critical for the assessment. All ANCOVA results were fitted using SAS PROC GLM. Statistical significance was set at a level of 0.05.

RESULTS

A total of 56 patients were enrolled in the pharmacokinetic substudy, 25 of whom were randomized (according to the APRICOT study protocol) to peginterferon alfa-2a (40KD) plus RBV and 31 to peginterferon alfa-2a (40KD) plus placebo (Fig. 1). The baseline characteristics of the patients are summarized in Table 1. At the design of the trial, the pharmacokinetic population was defined as patients who received at least one dose of either study drug and had completed the baseline pharmacokinetic assessments. Baseline pharmacokinetic assessments were obtained in all but one patient (in the peginterferon alfa-2a [40KD] plus placebo group). During the course of the study five patients withdrew prematurely for non-safety-related reasons leaving 51 patients who completed treatment including 23 recipients of peginterferon alfa-2a (40KD) plus RBV and 28 of peginterferon alfa-2a (40KD) plus placebo.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of patients at baselinea

| Parameter | Peginterferon alfa-2a (40KD) plus:

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Placebo (n = 31) | Ribavirin (n = 25) | |

| Sex, male/female (% male) | 28/3 (90) | 19/6 (76) |

| Age (yr) | 42.1 ± 7.6 | 41.2 ± 8.1 |

| Weight (kg) | 79.1 ± 13.3 | 70.8 ± 13.2 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 26.3 ± 5.1 | 24.6 ± 4.3 |

| Race, n (%) | ||

| White | 11 (35) | 14 (56) |

| Black | 8 (26) | 5 (20) |

| Hispanic | 12 (39) | 6 (24) |

| HCV genotype, n (%) | ||

| 1 | 24 (77) | 16 (64) |

| Non-1 | 7 (23) | 9 (36) |

| HCV RNA (106 IU/ml) | 6.65 ± 5.72 | 6.59 ± 6.95 |

| HIV-1 RNA (103 copies/ml)b | 2.19 ± 7.50 | 0.41 ± 1.17 |

| CD4+ cell count (cells/μl) | 441.0 ± 170.3 | 487.8 ± 224.5 |

| Antiretroviral therapy at baseline | ||

| Nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors, n (%) | ||

| 3TC | 30 (97) | 25 (100) |

| d4T | 17 (55) | 15 (60) |

| ZDV | 14 (45) | 10 (40) |

| ABC | 5 (16) | 0 |

| DDI | 1 (3) | 1 (4) |

| Specific NRTI combinations, n (%) | ||

| 3TC plus d4T | 16 (52) | 15 (60) |

| 3TC plus ZDV | 14 (45) | 10 (40) |

| d4T | 1 (3) | 0 |

| Protease inhibitors | 19 (61) | 13 (52) |

| Nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors | 10 (32) | 12 (48) |

Values are mean ± standard deviation, unless otherwise stated.

Patients with undetectable HIV-1 RNA (i.e. values less than 50 copies/ml) were included by setting values to 50 copies/ml, the limit of detection for the assay.

Baseline antiretroviral therapy was well balanced between the treatment arms and was representative of antiretroviral therapy used at the time the trial was conducted (Table 1). The most common NRTI combination was 3TC plus d4T. The range, of sampling times for the steady state was 7.3 to 14.3 weeks.

Pharmacokinetic parameters were calculated using all available measurements. In some cases, data were missing because of laboratory errors, damaged samples or samples not being taken. In some patients who completed the study, concentrations below the limit of quantitation or missing data prevented calculation of the AUC0-12 h. As these cases were randomly distributed in both baseline and steady state data, they were considered unlikely to impact the Cmax evaluations. However, as a result, the numbers of patients with evaluable data were not always the same throughout the study period or for all the parameters reported.

Plasma pharmacokinetics of 3TC, d4T, and ZDV.

Mean plasma AUC0-12 h and Cmax values of 3TC, d4T, and ZDV during the 12-hour sampling interval at baseline and steady state are presented in Table 2. Based on an analysis of covariance, there were no statistically significant differences in the steady state plasma AUC0-12 h or Cmax values for 3TC, d4T, and ZDV between patients treated with RBV and placebo: the ratios of the least squares mean AUC0-12 h values (RBV:placebo) were 1.17 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.91 to 1.51) for 3TC, 1.44 (95% CI, 0.58 to 3.60) for d4T and 0.85 (95% CI, 0.50 to 1.45) for ZDV, and the corresponding ratios for Cmax were 1.33 (95% CI, 0.99 to 1.78) for 3TC, 1.06 (95% CI, 0.68 to 1.65) for d4T, and 0.84 (95% CI, 0.46 to 1.53) for ZDV (Table 3).

TABLE 2.

Mean plasma AUC0-12 h and Cmax of lamivudine, stavudine, and zidovudine at baseline and steady state and of ribavirin at steady statea

| Parameter and drug | Peginterferon alfa-2a (40KD) 180 μg/wk plus placebo

|

Peginterferon alfa-2a (40KD) 180 μg/wk plus RBV 800 mg/day

|

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Baseline | CV | N | Steady stateb | CV | N | Baseline | CV | N | Steady stateb | CV | |

| AUC0-12 h ± SD (ng · h/ml) | ||||||||||||

| 3TC | 27 | 5,811 ± 2,772 | 48 | 24 | 5,374 ± 2,153 | 40 | 24 | 5,894 ± 2,133 | 36 | 22 | 6,836 ± 3,663 | 54 |

| D4T | 9 | 1,526 ± 535 | 35 | 4 | 1,359 ± 508 | 37 | 7 | 1,775 ± 688 | 39 | 5 | 1,967 ± 660 | 34 |

| ZDV | 10 | 1,731 ± 1,305 | 75 | 12 | 2,221 ± 1,683 | 76 | 10 | 1,550 ± 876 | 57 | 7 | 1,734 ± 1,377 | 79 |

| RBV | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 20 | 23,476 ± 9,983 | 43 | |||

| Cmax ± SD (ng/ml) | ||||||||||||

| 3TC | 27 | 1,064 ± 447 | 42 | 25 | 1,015 ± 381 | 37 | 25 | 1,193 ± 335 | 28 | 22 | 1,276 ± 625 | 49 |

| d4T | 13 | 317 ± 139 | 44 | 12 | 276 ± 111 | 40 | 15 | 317 ± 111 | 35 | 13 | 289 ± 114 | 39 |

| ZDV | 12 | 619 ± 534 | 86 | 12 | 643 ± 439 | 68 | 10 | 507 ± 265 | 52 | 8 | 735 ± 752 | 102 |

| RBV | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 21 | 2,771 ± 1,653 | 60 | |||

CV, coefficient of variation in percent; NA, not applicable; SD, standard deviation.

Sampling times ranged from 7.3 to 14.3 weeks.

TABLE 3.

Analysis of covariance of plasma AUC0-12 h and Cmax of lamivudine, stavudine, and zidovudine at steady state

| Parameter and drug | Peginterferon alfa-2a (40KD) plus: | N | Steady-state geometric LSMa | Ratio of geometric LSMb | 95% CI for the ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AUC0-12 h | |||||

| 3TC | RBV | 21 | 6,005.82 | 1.17 | 0.91, 1.51 |

| Placebo | 22 | 5,123.56 | |||

| d4T | RBV | 4 | 2,037.62 | 1.44 | 0.58, 3.60 |

| Placebo | 3 | 1,412.45 | |||

| ZDV | RBV | 7 | 1,279.84 | 0.85 | 0.50, 1.45 |

| Placebo | 10 | 1,508.17 | |||

| Cmax | |||||

| 3TC | RBV | 22 | 1,227.72 | 1.33 | 0.99, 1.78 |

| Placebo | 23 | 923.15 | |||

| d4T | RBV | 13 | 270.72 | 1.06 | 0.68, 1.65 |

| Placebo | 9 | 256.36 | |||

| ZDV | RBV | 7 | 450.31 | 0.84 | 0.46, 1.53 |

| Placebo | 10 | 534.53 |

Sampling times ranged from 7.3 to 14.3 weeks. LSM, least squares mean.

Ratio of value in the RBV-containing arm to that in the placebo-containing arm. Note: the numbers of patients included in the statistical analyses provided in the table differ from the numbers of patients with plasma AUC0-12h or Cmax values in Table 2 because the statistical analysis of the plasma AUC0-12h or Cmax values was performed only in patients who had both baseline and week 12 values.

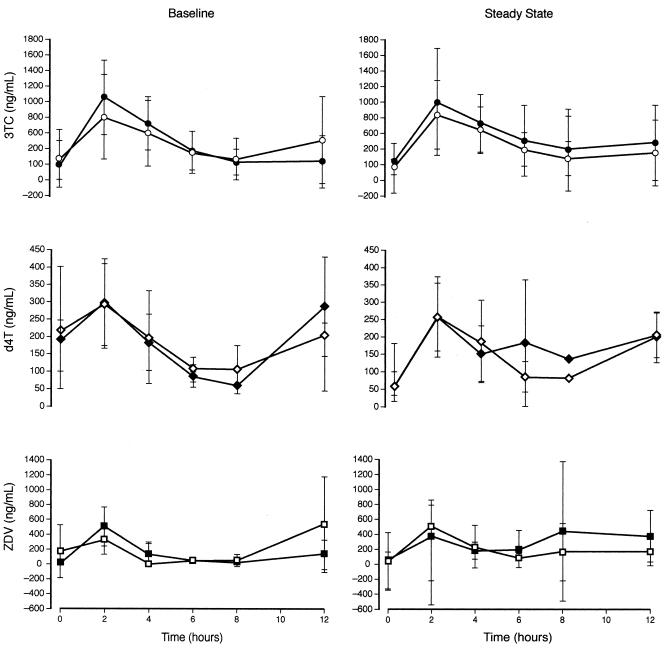

The changes in mean plasma concentration with time for 3TC, d4T, and ZDV are presented in Fig. 2. The profiles show considerable variability over the 12-h sampling time. In addition, some of the patient profiles, particularly for d4T show small increases at the end of the dosing interval. These findings were not significant and have not been noted previously and are most likely the result of the considerable variability. Importantly, the concentration-time profiles for each of the NRTIs show similar drug exposure at baseline and after 8 to 12 weeks of study treatment.

FIG. 2.

Mean plasma concentrations of lamivudine (3TC), stavudine (d4T) and zidovudine (ZDV) over the 12-hour period after dosing on the first day of the 12-week substudy and at steady state (weeks 8 to 12). Patients received peginterferon alfa-2a (40KD) plus either ribavirin (solid symbols) or placebo (open symbols) according to the APRICOT study protocol. Vertical bars represent standard deviations. Note that the vertical scales differ.

Intracellular phosphorylation of 3TC, d4T, and ZDV.

The intracellular AUC0-12 h values for the phosphorylated NRTIs and their corresponding endogenous nucleoside triphosphates are presented in Table 4. There was considerable variability in the mean AUC0-12 h values of dCTP and dTTP at baseline and steady state and there is considerable overlap of the standard deviations of the means when the mean values are compared. Moreover, there was no evidence of a significant interaction between RBV and either 3TC, d4T, or ZDV based on the ratio of the intracellular AUC0-12 h values of the respective NRTI triphosphates to the corresponding endogenous nucleoside triphosphates in PBMCs.

TABLE 4.

Mean intracellular AUC0-12 h of triphosphate metabolites of lamivudine, stavudine, and zidovudine and endogenous nucleoside triphosphates at baseline and steady state

| Drug | Peginterferon alfa-2a (40KD) 180 μg/wk plus placebo (%)

|

Peginterferon alfa-2a (40KD) 180 μg/wk plus RBV 800 mg/day

|

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Baseline AUC0-12 ha | CV (%) | N | SS AUC0-12 hab | CV (%) | N | Baseline AUC0-12 ha | CV (%) | N | SS AUC0-12 hab | CV (%) | |

| 3TC-TP | 25 | 8.29 ± 5.25 | 63 | 19 | 8.13 ± 3.44 | 42 | 21 | 9.76 ± 4.89 | 50 | 20 | 8.64 ± 4.78 | 55 |

| d4T-TP | 10 | 0.53 ± 0.33 | 62 | 8 | 0.42 ± 0.19 | 45 | 14 | 0.93 ± 0.66 | 71 | 13 | 0.81 ± 0.55 | 68 |

| ZDV-TP | 12 | 0.75 ± 0.48 | 63 | 13 | 0.60 ± 0.37 | 63 | 9 | 0.76 ± 0.61 | 81 | 7 | 0.88 ± 0.64 | 73 |

| dCTP | 24 | 6.54 ± 3.10 | 47 | 21 | 5.64 ± 1.91 | 34 | 21 | 8.13 ± 3.20 | 39 | 21 | 6.26 ± 3.30 | 53 |

| dTTP | 26 | 3.00 ± 1.89 | 63 | 21 | 2.50 ± 1.44 | 58 | 21 | 4.98 ± 3.63 | 73 | 21 | 4.44 ± 3.08 | 69 |

| 3TC-TP/dTTPc | 23 | 1.50 ± 1.09 | 73 | 18 | 1.63 ± 0.74 | 45 | 21 | 1.40 ± 0.95 | 68 | 20 | 1.72 ± 1.08 | 63 |

| d4T-TP/dTTPc | 10 | 0.18 ± 0.13 | 74 | 7 | 0.18 ± 0.09 | 49 | 12 | 0.18 ± 0.05 | 26 | 13 | 0.17 ± 0.03 | 19 |

| ZDV-TP/dCTPc | 12 | 0.25 ± 0.12 | 49 | 12 | 0.31 ± 0.31 | 101 | 8 | 0.25 ± 0.23 | 92 | 7 | 0.23 ± 0.15 | 65 |

Values are means ± SD in pmol·h/106 cells.

Sampling times ranged from 7.3 to 14.3 weeks. SS, steady state.

Ratio of AUC0-12h values for 3TC-TP, d4T-TP, and ZDV-TP to the corresponding endogenous nucleoside triphosphates.

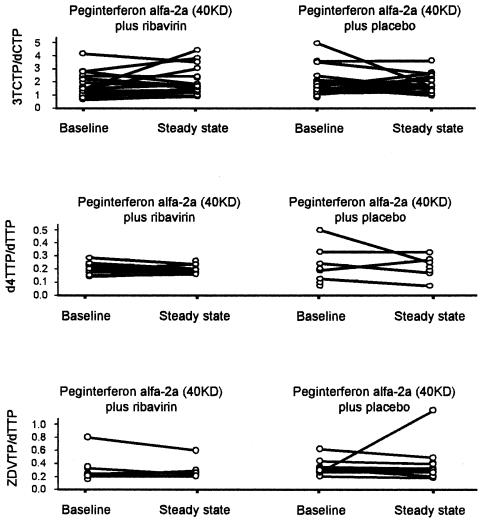

The differences at steady state between RBV and placebo in the least squares mean ratios of AUC0-12 h for each NRTI triphosphates to its corresponding endogenous nucleoside triphosphates are presented in Table 5. The differences (RBV minus placebo) were 0.274 (95% CI, −0.37 to 0.91) for 3TC-TP:dCTP, 0.009 (95% CI, −0.06 to 0.08) for d4T-TP:dTTP and −0.081 (95% CI, −0.40 to 0.24) for ZDV-TP:dTTP. The lack of any significant effect of treatment is further evidenced by the AUC ratios of intracellular NRTI triphosphates to the corresponding endogenous nucleoside triphosphates at baseline and steady state in individual patients (Fig. 3). Comparison of the ribavirin and placebo arms shows a similar pattern -considerable intrapatient variation was observed, but no trends were associated with treatment. Figure 3 also illustrates that there were no apparent changes in the AUC ratios of intracellular NRTI triphosphates to the corresponding endogenous nucleoside triphosphates between baseline and steady state in both the placebo and ribavirin treatment arms.

TABLE 5.

Least square mean ratios of the intracellular concentrations of triphosphorylated metabolites of lamivudine, stavudine, and zidovudine to those of the corresponding endogenous triphosphates in PBMCs at steady state in each treatment group

| Intracellular AUC0-12 h ratio | Peginterferon alfa-2a (40KD) plus: | N | LSM ratio at SSa | Differenceb in LSM ratios | 95% CI of the difference in LSM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3TC-TP/dCTP | RBV | 18 | 1.783 | 0.274 | −0.37, 0.91 |

| Placebo | 17 | 1.509 | |||

| d4T-TP/dTTP | RBV | 10 | 0.173 | 0.009 | −0.06, 0.08 |

| Placebo | 5 | 0.164 | |||

| ZDV-TP/dTTP | RBV | 6 | 0.235 | −0.081 | −0.40, 0.24 |

| Placebo | 10 | 0.316 | |||

| dTTP | RBV | 18 | 3.753 | 0.761 | −0.38, 1.90 |

| Placebo | 19 | 2.991 | |||

| dCTP | RBV | 18 | 5.882 | −0.119 | −1.77, 1.53 |

| Placebo | 18 | 6.001 |

Sampling times ranged from 7.3 to 14.3 weeks. SS, steady state.

Difference, ratio for RBV minus ratio for placebo.

FIG. 3.

Intrapatient variation in the AUC ratios of intracellular NRTI triphosphates to their corresponding triphosphates in patients undergoing treatment with peginterferon alfa-2a (40KD) plus either ribavirin or placebo. For both treatment arms, variation between baseline and steady state in individual patients is also illustrated (joined lines).

There were no statistically significant differences between the least squares mean AUC0-12 h values for the endogenous nucleoside triphosphates in patients treated with RBV and placebo for 8 to 12 weeks (Table 5).

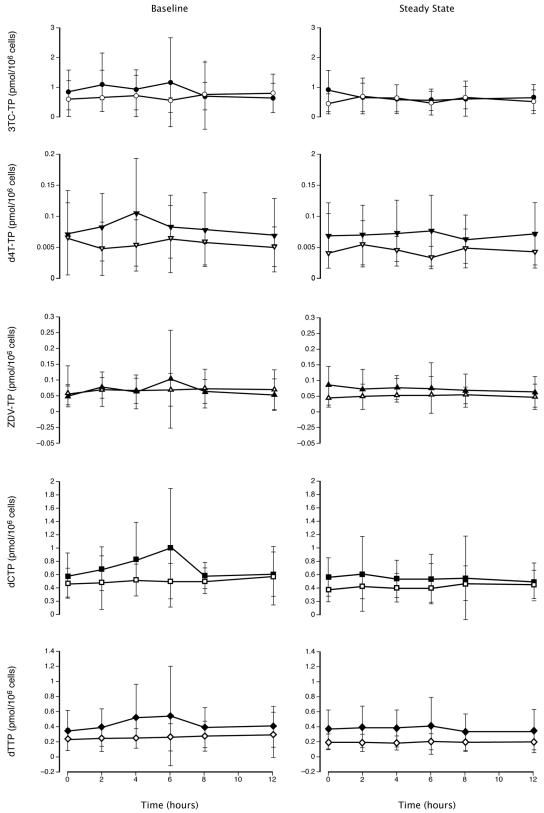

The mean intracellular concentration-time profiles for 3TC-TP, d4T-TP, ZDV-TP, dCTP and dTTP are presented in Fig. 4. The concentration-time profiles for each of these metabolites were similar at baseline and steady state with a broad overlap in the standard deviations at each time point. In agreement with previous studies (3, 31, 33), the intracellular triphosphate profiles of the NRTIs are much flatter than the plasma profiles of the parent drug.

FIG. 4.

Mean intracellular NRTI-triphosphate concentration-time profile at baseline and steady state (weeks 8 to 12). Solid symbols represent patients treated with peginterferon alfa-2a (40KD) plus ribavirin. Open symbols represent patients treated with peginterferon alfa-2a (40KD) plus placebo. Vertical bars represent standard deviations. Note that the vertical scales differ. 3TC-TP, lamivudine-triphosphate; d4T-TP, stavudine-triphosphate; dCTP, deoxycytidine triphosphate; dTTP, deoxythymidine triphosphate; ZDV-TP, zidovudine-triphosphate.

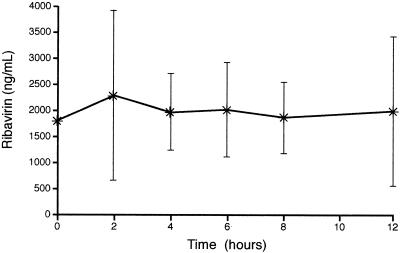

Pharmacokinetics of RBV.

The plasma AUC0-12 h and Cmax values for RBV at steady state are presented in Table 2 and the plasma concentration-time profile at steady state is presented in Fig. 5. The mean steady-state plasma Cmax was 2,771 ng/ml, and the mean AUC0-12 h was 23,476 ng · h/ml.

FIG. 5.

Mean plasma concentration-time profile for ribavirin at steady state (weeks 8 to 12). Vertical bars represent standard deviations.

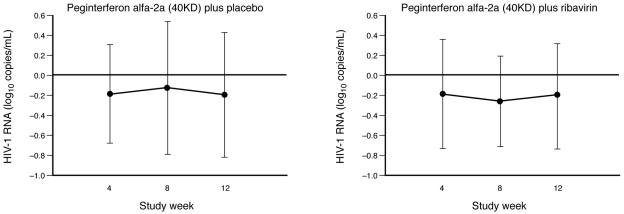

Pharmacodynamic parameters.

At baseline most patients had undetectable serum HIV-1 RNA levels. There was no significant change from baseline in the median HIV-1 RNA level at week 4, 8, or 12 in either treatment group. There was no evidence of any increase in mean HIV-1 RNA levels in patients treated with either peginterferon alfa-2a (40KD) plus placebo or peginterferon alfa-2a (40KD) plus RBV at weeks 4, 8, and 12 (Fig. 6).

FIG. 6.

Mean change from baseline in HIV-1 RNA levels at weeks 4, 8, and 12 of treatment. Vertical bars represent standard deviations.

Mean and median CD4+ cell counts decreased in both treatment groups over the 12 week study period. The median change in CD4+ count at week 12 was −72 cells/μl (range, −377 to 756 cells/μl) and −87.5 cells/μl (range, −284 to 101 cells/μl) in patients treated with placebo and RBV, respectively.

Safety.

The safety profiles of peginterferon alfa-2a (40KD) plus placebo and peginterferon alfa-2a (40KD) plus RBV in this substudy reflected that reported in APRICOT (41). Modifications in the dose of peginterferon alfa-2a (40KD) because of adverse events or laboratory abnormalities were consistent with those reported in APRICOT.

In this substudy, serious adverse events were reported in 3 (10%) patients treated with peginterferon alfa-2a (40KD) plus placebo and 2 (8%) patients treated with peginterferon alfa-2a (40KD) plus RBV. Only two serious adverse events were considered related to treatment (pancreatitis in one placebo recipient and anemia in one RBV recipient). No deaths occurred during the pharmacokinetic substudy.

DISCUSSION

Our results suggest that RBV at a dosage of 800 mg/day does not have a clinically significant effect on the plasma pharmacokinetics or intracellular phosphorylation of 3TC, d4T, or ZDV in HIV-HCV-coinfected patients. There were no statistically significant differences in the plasma AUC0-12 h or Cmax of 3TC, d4T, or ZDV between patients treated with RBV or placebo. Moreover, the intracellular AUC0-12 h ratios of the triphosphate anabolites of 3TC, d4T, and ZDV to the corresponding endogenous nucleoside triphosphates in PBMCs were not changed significantly by treatment with RBV. This is important because the triphosphorylated anabolites of NRTIs, produced by intracellular kinases, drive both the efficacy and toxicity of these agents by competitively inhibiting reverse transcriptase in HIV-infected cells.

As evidenced by the wide standard deviations and broad confidence intervals, interpatient variation in the plasma and intracellular triphosphate concentrations for the three NRTIs was large but consistent throughout the study. The 95% confidence intervals are smaller for the 3TC data than ZDV and d4T (due to more patients receiving 3TC), and the evidence for an absence of an effect is largest for 3TC and less for ZDV and d4T. Nevertheless, these findings are not unexpected and are consistent with data from other studies of the NRTIs by several research groups using different methodologies. Large interpatient variation in both intracellular phosphorylation and plasma exposure of NRTIs have been reported previously (4, 17, 24, 28, 31, 33, 34, 38). In addition, wide variation also exists in the intracellular concentrations of endogenous nucleoside triphosphates (16, 17, 24, 37).

The mean steady-state plasma Cmax (2,771 ng/ml) and AUC0-12 (23,476 ng · h/ml) values of RBV in our study are in good agreement with those obtained with the same dosage of the drug (400 mg twice daily) in HIV-infected patients in an earlier study (2,440 ng/ml and 24,546 ng · h/ml, respectively) (25).

Our findings contrast with the results of in vitro studies that suggest that RBV inhibits the phosphorylation of ZDV (19, 38, 42) and d4T (15). These studies measured the total concentration of the phosphorylated metabolites of ZDV and d4T in PBMCs and human cell lines, including the monophosphate, diphosphate and triphosphate metabolites. RBV had the greatest impact on ZDV monophosphate levels, although the ratio of dTTP:ZDV-TP also increased in the presence of RBV (38). The results suggest that RBV increases intracellular formation of dTTP, which reduces the activity of thymidine kinase through feedback inhibition. The end result is a reduction in the phosphorylation of ZDV and d4T.

There are several possible explanations for the discrepancy between the findings in our study in patients with HIV-HCV coinfection and the findings of in vitro studies. The in vivo pharmacokinetics of RBV may be responsible to some extent for the observed differences. RBV is preferentially taken up by erythrocytes in vivo, which contributes to the large interpatient variability; a 60:1 red blood cell:plasma concentration ratio at steady state has been reported in HIV-infected patients receiving 800 mg/day (25). In addition to PBMCs, human cell lines were used in these investigations, which have different properties than cells in patients with HCV-HIV coinfection.

We measured the intracellular concentrations of endogenous nucleoside triphosphates and the triphosphorylated anabolites of 3TC, d4T, and ZDV after 8 to 12 weeks of continuous exposure to RBV, which is considerably longer than the brief exposure in the in vitro experiments. The longer treatment duration, large number of patients and the inclusion of a placebo group may also be responsible for the differences between this and the in vitro studies. It is possible that, after weeks of treatment, homeostatic mechanisms corrected transient perturbations that occurred shortly after the initiation of study treatment. Finally, it should be noted that other discrepancies between in vitro and in vivo studies have been reported: hydroxyurea has been consistently shown to increase intracellular levels of NRTIs in vitro (11, 12, 21) though the magnitude of changes in vivo are minimal.

The most important evidence of the absence of a clinically significant drug interaction between RBV and the nucleoside triphosphates is provided by HIV-1 levels in the two treatment groups. HIV-1 RNA levels did not increase in either treatment group during our study. This finding was also evident in the overall APRICOT population at the end of treatment: in patients who had detectable HIV-1 RNA at baseline, HIV-1 RNA levels were lower at the end of treatment (week 48) than at baseline in those treated with peginterferon alfa-2a (40KD) plus placebo and peginterferon alfa-2a (40KD) plus RBV (41). Moreover, the decreases were of similar magnitude (−0.7 to −0.8 log10 copies/ml). Reductions in HIV-1 levels have also been reported in patients with HIV-HCV coinfection after treatment with conventional interferon plus RBV combination therapy (6, 34). The CD4+ percentage increased in patients receiving combination therapy for HCV in APRICOT and in the other studies, a further indicator of ongoing control of HIV disease (6, 34, 41). These data should allay concerns that RBV may negatively affect control of HIV replication in HIV-HCV coinfected patients receiving antiretroviral therapy.

A study in patients with HIV-HCV coinfection who were randomized to conventional interferon, 3 MIU thrice weekly, plus RBV, 1,000 or 1,200 mg/day, or no treatment has also reported results contrary to those of in vitro investigations (34). RBV did not increase intracellular dTTP concentrations as predicted by in vitro studies; rather a transient decrease in dTTP concentrations was observed during the first month of RBV treatment. Serum HIV-1 RNA levels remained well controlled in both groups, similar to the findings in our study, and the combination regimen was judged to be effective and well tolerated for the treatment of HCV (34). The study reported a nonsignificant trend toward lower median peak and trough intracellular d4T-TP concentrations, a trend toward a decrease in the d4T-TP:dTTP ratio, and large intra- and interpatient variability (34). An increase in d4T-TP levels in the control group makes interpretation of the results difficult, as does the absence of a conventional interferon monotherapy control group. The overall findings are in agreement with those in our study that there is no evidence of a clinically significant interaction between RBV and d4T in patients with HIV-HCV coinfection.

Our study focused on the intracellular phosphorylation and plasma pharmacokinetics of 3TC, ZDV, and d4T and thus cannot be used to draw conclusions about the intracellular pharmacokinetics of all NRTIs in combination with RBV. Nonetheless, a broad spectrum of agents was used during the course of APRICOT, which suggests that antiretroviral therapy is compatible with peginterferon alfa-2a (40KD) plus RBV in HIV-HCV coinfected patients. The one possible exception to this generalization is didanosine (DDI), which has been associated with pancreatitis when given as monotherapy and when used in combination with RBV (29, 39). Only two patients received DDI during our nested pharmacokinetic study. An analysis of data from 14 cirrhotic patients who experienced hepatic decompensation during or after treatment in APRICOT revealed that use of DDI, among other factors, was significantly associated with this adverse event. Importantly, hepatic decompensation occurred with similar frequency in patients treated with or without RBV and thus did not appear to be exacerbated by the use of this drug. This is consistent with the absence of a pharmacokinetic interaction between these two drugs, as reported in a previous study, (20) but does not preclude an intracellular interaction. Nonetheless, there have been reports of severe mitochondrial toxicity, including fatalities, in patients receiving concurrent DDI and RBV (7-9, 13). Thus, use of DDI should be avoided in patients with HIV-HCV coinfection, particularly in those receiving RBV and those with cirrhosis (27, 39).

Conclusions.

In patients with HIV-HCV coinfection who are receiving stable antiretroviral therapy, peginterferon alfa-2a (40KD) 180 μg/week plus RBV 800 mg/day does not perturb intracellular levels of the triphosphate anabolites of 3TC, d4T, or ZDV. RBV does not modify the plasma concentration-time profile of these NRTIs and control of HIV-1 RNA replication is not adversely affected. When the results of this pharmacokinetic analysis are considered together with the overall outcome of APRICOT, it is clear that combination therapy with peginterferon alfa-2a (40KD) plus RBV is both effective and safe and can be recommended for patients with HIV-HCV coinfection and compensated liver disease.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to S. Kewn for expert performance of phosphorylation assays.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alter, M. J., D. Kruszon-Moran, O. V. Nainan, G. M. McQuillan, F. Gao, L. A. Moyer, R. A. Kaslow, and H. S. Margolis. 1999. The prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection in the United States, 1988 through 1994. N. Engl. J. Med. 341:556-562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Anonymous. 2002. National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Conference Statement: management of hepatitis C, June 10-12, 2002. Hepatology 36:S3-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barry, M., M. Wild, G. Veal, D. Back, A. Breckenridge, R. Fox, N. Beeching, F. Nye, P. Carey, and D. Timmins. 1994. Zidovudine phosphorylation in HIV-infected patients and seronegative volunteers. AIDS 8:F1-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barry, M. G., S. H. Khoo, G. J. Veal, P. G. Hoggard, S. E. Gibbons, E. G. Wilkins, O. Williams, A. M. Breckenridge, and D. J. Back. 1996. The effect of zidovudine dose on the formation of intracellular phosphorylated metabolites. AIDS 10:1361-1367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brau, N. 2003. Update on chronic hepatitis C in HIV/HCV-coinfected patients: viral interactions and therapy. AIDS 17:2279-2290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brau, N., M. Rodriguez-Torres, D. Prokupek, M. Bonacini, C. A. Giffen, J. J. Smith, K. R. Frost, and J. R. Kostman. 2004. Treatment of chronic hepatitis C in HIV/HCV-coinfection with interferon alpha-2b+ full-course vs. 16-week delayed ribavirin. Hepatology 39:989-998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bruno, R., P. Sacchi, and G. Filice. 2003. Didanosine-ribavirin combination: synergistic combination in vitro, but high potential risk of toxicity in vivo. AIDS 17:2674-2675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Butt, A. A. 2003. Fatal lactic acidosis and pancreatitis associated with ribavirin and didanosine therapy. AIDS Read. 13:344-348. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fleischer, R., D. Boxwell, and K. E. Sherman. 2004. Nucleoside analogues and mitochondrial toxicity. Clin. Infect. Dis. 38:79-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fried, M. W., M. L. Shiffman, K. R. Reddy, C. Smith, G. Marinos, F. L. Goncales, Jr., D. Haussinger, M. Diago, G. Carosi, D. Dhumeaux, A. Craxi, A. Lin, J. Hoffman, and J. Yu. 2002. Peginterferon alfa-2a plus ribavirin for chronic hepatitis C virus infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 347:975-982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gao, W. Y., A. Cara, R. C. Gallo, and F. Lori. 1993. Low levels of deoxynucleotides in peripheral blood lymphocytes: a strategy to inhibit human immunodeficiency virus type 1 replication. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90:8925-8928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gao, W. Y., D. G. Johns, and H. Mitsuya. 1994. Anti-human immunodeficiency virus type 1 activity of hydroxyurea in combination with 2′,3′-dideoxynucleosides. Mol. Pharmacol. 46:767-772. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Glesby, M. J., and J. G. Gerber. 2003. Editorial comment: drug-drug interactions, hepatitis C, and mitochondrial toxicity. AIDS Read. 13:346-347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hadziyannis, S. J., H. Sette, Jr., T. R. Morgan, V. Balan, M. Diago, P. Marcellin, G. Ramadori, H. Bodenheimer, Jr., D. Bernstein, M. Rizzetto, S. Zeuzem, P. J. Pockros, A. Lin, and A. M. Ackrill. 2004. Peginterferon-alpha2a and ribavirin combination therapy in chronic hepatitis C: a randomized study of treatment duration and ribavirin dose. Ann. Intern. Med. 140:346-355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hoggard, P. G., S. Kewn, M. G. Barry, S. H. Khoo, and D. J. Back. 1997. Effects of drugs on 2′,3′-dideoxy-2′,3′-didehydrothymidine phosphorylation in vitro. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41:1231-1236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoggard, P. G., S. Kewn, A. Maherbe, R. Wood, L. M. Almond, S. D. Sales, J. Gould, Y. Lou, C. De Vries, D. J. Back, and S. H. Khoo. 2002. Time-dependent changes in HIV nucleoside analogue phosphorylation and the effect of hydroxyurea. AIDS 16:2439-2446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hoggard, P. G., J. Lloyd, S. H. Khoo, M. G. Barry, L. Dann, S. E. Gibbons, E. G. Wilkins, C. Loveday, and D. J. Back. 2001. Zidovudine phosphorylation determined sequentially over 12 months in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients with or without previous exposure to antiretroviral agents. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:976-980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hoggard, P. G., S. D. Sales, D. Phiboonbanakit, J. Lloyd, B. A. Maher, S. H. Khoo, E. Wilkins, P. Carey, C. A. Hart, and D. J. Back. 2001. Influence of prior exposure to zidovudine on stavudine phosphorylation in vivo and ex vivo. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:577-582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hoggard, P. G., G. J. Veal, M. J. Wild, M. G. Barry, and D. J. Back. 1995. Drug interactions with zidovudine phosphorylation in vitro. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 39:1376-1378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Japour, A. J., J. J. Lertora, P. M. Meehan, A. Erice, J. D. Connor, B. P. Griffith, P. A. Clax, J. Holden-Wiltse, S. Hussey, M. Walesky, E. Cooney, R. Pollard, J. Timpone, C. McLaren, N. Johanneson, K. Wood, D. Booth, Y. Bassiakos, and C. S. Crumpacker. 1996. A phase-I study of the safety, pharmacokinetics, and antiviral activity of combination didanosine and ribavirin in patients with HIV-1 disease. AIDS Clinical Trials Group 231 Protocol Team. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. Hum. Retrovirol. 13:235-246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kewn, S., P. G. Hoggard, S. D. Sales, M. A. Johnson, and D. J. Back. 2000. The intracellular activation of lamivudine (3TC) and determination of 2′-deoxycytidine-5′-triphosphate (dCTP) pools in the presence and absence of various drugs in HepG2 cells. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 50:597-604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kewn, S., P. G. Hoggard, S. D. Sales, K. Jones, B. Maher, S. H. Khoo, and D. J. Back. 2002. Development of enzymatic assays for quantification of intracellular lamivudine and carbovir triphosphate levels in peripheral blood mononuclear cells from human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:135-143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kewn, S., G. J. Veal, P. G. Hoggard, M. G. Barry, and D. J. Back. 1997. Lamivudine (3TC) phosphorylation and drug interactions in vitro. Biochem. Pharmacol. 54:589-595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kewn, S., L. H. Wang, P. G. Hoggard, F. Rousseau, R. Hart, J. P. MacNeela, S. H. Khoo, and D. J. Back. 2003. Enzymatic assay for measurement of intracellular DXG triphosphate concentrations in peripheral blood mononuclear cells from human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected patients. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:255-261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lertora, J. J., A. B. Rege, J. T. Lacour, N. Ferencz, W. J. George, R. B. VanDyke, K. C. Agrawal, and N. E. Hyslop, Jr. 1991. Pharmacokinetics and long-term tolerance to ribavirin in asymptomatic patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 50:442-449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Manns, M. P., J. G. McHutchison, S. C. Gordon, V. K. Rustgi, M. Shiffman, R. Reindollar, Z. D. Goodman, K. Koury, M. Ling, and J. K. Albrecht. 2001. Peginterferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin compared with interferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin for initial treatment of chronic hepatitis C: a randomised trial. Lancet 358:958-965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mauss, S., W. Valenti, J. DePamphilis, F. Duff, L. Cupelli, S. Passe, J. Solsky, F. J. Torriani, D. Dieterich, and D. Larrey. Risk factors for hepatic decompensation in patients with HIV/HCV coinfection and liver cirrhosis during interferon-based therapy. AIDS, in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Moore, J. D., G. Valette, A. Darque, X. J. Zhou, and J. P. Sommadossi. 2000. Simultaneous quantitation of the 5′-triphosphate metabolites of zidovudine, lamivudine, and stavudine in peripheral mononuclear blood cells of HIV infected patients by high-performance liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 11:1134-1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moreno, A., C. Quereda, L. Moreno, M. J. Perez-Elias, A. Muriel, J. L. Casado, A. Antela, F. Dronda, E. Navas, R. Barcena, and S. Moreno. 2004. High rate of didanosine-related mitochondrial toxicity in HIV/HCV-coinfected patients receiving ribavirin. Antivir. Ther. 9:133-138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Robbins, B. L., J. Rodman, C. McDonald, R. V. Srinivas, P. M. Flynn, and A. Fridland. 1994. Enzymatic assay for measurement of zidovudine triphosphate in peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 38:115-121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Robbins, B. L., T. T. Tran, F. H. Pinkerton, Jr., F. Akeb, R. Guedj, J. Grassi, D. Lancaster, and A. Fridland. 1998. Development of a new cartridge radioimmunoassay for determination of intracellular levels of lamivudine triphosphate in the peripheral blood mononuclear cells of human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:2656-2660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rockstroh, J. K., and U. Spengler. 2004. HIV and hepatitis C virus coinfection. Lancet Infect. Dis. 4:437-444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rodriguez, J. F., J. L. Rodriguez, J. Santana, H. Garcia, and O. Rosario. 2000. Simultaneous quantitation of intracellular zidovudine and lamivudine triphosphates in human immunodeficiency virus-infected individuals. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:3097-3100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Salmon-Ceron, D., R. Lassalle, A. Pruvost, H. Benech, M. Bouvier-Alias, C. Payan, C. Goujard, E. Bonnet, F. Zoulim, P. Morlat, P. Sogni, S. Perusat, J. M. Treluyer, and G. Chene. 2003. Interferon-ribavirin in association with stavudine has no impact on plasma human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) type 1 level in patients coinfected with HIV and hepatitis C virus: a CORIST-ANRS HC1 trial. Clin. Infect. Dis. 36:1295-1304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sankatsing, S. U., P. G. Hoggard, A. D. Huitema, R. W. Sparidans, S. Kewn, K. M. Crommentuyn, J. M. Lange, J. H. Beijnen, D. J. Back, and J. M. Prins. 2004. Effect of mycophenolate mofetil on the pharmacokinetics of antiretroviral drugs and on intracellular nucleoside triphosphate pools. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 43:823-832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sherman, K. E., S. D. Rouster, R. T. Chung, and N. Rajicic. 2002. Hepatitis C Virus prevalence among patients infected with Hum. Immunodeficiency Virus: a cross-sectional analysis of the US adult AIDS Clinical Trials Group. Clin. Infect. Dis. 34:831-837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sherman, P. A., and J. A. Fyfe. 1989. Enzymatic assay for deoxyribonucleoside triphosphates using synthetic oligonucleotides as template primers. Anal. Biochem. 180:222-226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sim, S. M., P. G. Hoggard, S. D. Sales, D. Phiboonbanakit, C. A. Hart, and D. J. Back. 1998. Effect of ribavirin on zidovudine efficacy and toxicity in vitro: a concentration-dependent interaction. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 14:1661-1667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Soriano, V., M. Puoti, M. Sulkowski, S. Mauss, P. Cacoub, A. Cargnel, D. Dieterich, A. Hatzakis, and J. Rockstroh. 2004. Care of patients with hepatitis C and HIV coinfection. AIDS 18:1-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Strader, D. B., T. Wright, D. L. Thomas, and L. B. Seeff. 2004. Diagnosis, management, and treatment of hepatitis C. Hepatology 39:1147-1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Torriani, F. J., M. Rodriguez-Torres, J. K. Rockstroh, E. Lissen, J. Gonzalez-Garcia, A. Lazzarin, G. Carosi, J. Sasadeusz, C. Katlama, J. Montaner, H. Sette, Jr., S. Passe, J. De Pamphilis, F. Duff, U. M. Schrenk, and D. T. Dieterich. 2004. Peginterferon alfa-2a plus ribavirin for chronic hepatitis C virus infection in HIV-infected patients. N. Engl. J. Med. 351:438-450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vogt, M. W., K. L. Hartshorn, P. A. Furman, T. C. Chou, J. A. Fyfe, L. A. Coleman, C. Crumpacker, R. T. Schooley, and M. S. Hirsch. 1987. Ribavirin antagonizes the effect of azidothymidine on HIV replication. Science 235:1376-1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zeuzem, S., M. Diago, E. Gane, K. R. Reddy, P. Pockros, D. Prati, M. Shiffman, P. Farci, N. Gitlin, C. B. O'Brien, F. Lamour, and P. Lardelli. 2004. Peginterferon alfa-2a (40 kilodaltons) and ribavirin in patients with chronic hepatitis C and normal aminotransferase levels. Gastroenterology 127:1724-1732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]