Abstract

Vibrio vulnificus is a causative agent of serious food-borne diseases in humans related to the consumption of raw seafood. It secretes a metalloprotease that is associated with skin lesions and serious hemorrhagic complications. In this study, we purified and characterized an extracellular metalloprotease (designated as vEP) having prothrombin activation and fibrinolytic activities from V. vulnificus ATCC 29307. vEP could cleave various blood clotting-associated proteins such as prothrombin, plasminogen, fibrinogen, and factor Xa, and the cleavage could be stimulated by addition of 1 mM Mn2+ in the reaction. The cleavage of prothrombin produced active thrombin capable of converting fibrinogen to fibrin. The formation of active thrombin appeared to be transient, with further cleavage resulting in a loss of activity. The cleavage of plasminogen, however, did not produce an active plasmin. vEP could cleave all three major chains of fibrinogen without forming a clot. It could cleave fibrin polymer formed by thrombin as well as the cross-linked fibrin formed by factor XIIIa. In addition, vEP could also cleave plasma proteins such as bovine serum albumin and gamma globulin, and its broad specificity is reflected in the cleavage sites, which include Asp207-Phe208 and Thr272-Ala273 bonds in prothrombin and a Tyr80-Leu81 bond in plasminogen. Taken together, the data suggest that vEP is a broad-specificity protease that could function as a prothrombin activator and a fibrinolytic enzyme to interfere with blood homeostasis as part of the mechanism associated with the pathogenicity of V. vulnificus in humans and thereby facilitate the development of systemic infection.

Proteolytic enzymes play various physiological roles and are essential factors for homeostatic control in both eukaryotes and prokaryotes. However, the enzyme produced by pathogenic microorganisms, particularly by opportunistic pathogens, can also act as toxic factors to the host. Vibrio vulnificus is an opportunistic organism pathogenic to humans that causes wound infection and septicemia (2, 10, 38, 40). Like other Vibrio strains, this pathogen secretes a 45-kDa zinc metalloprotease that has been reported to have many biological functions. It causes the degradation of a variety of host proteins and enhancement of vascular permeability through the generation of inflammatory mediators (21, 26, 28). The only physiological inhibitor of this protease is α2-macroglobulin, which has been shown to inhibit the enzyme's activity toward casein and elastin as well as its permeability-enhancing and hemorrhagic activities, but the peptidase activity toward certain peptide substrate was not reduced (27). The protease has been purified from the culture supernatant of two V. vulnificus strains, ATCC 29307 (16) and L-180 (20). The gene encoding the protease in both strains has also been cloned (11, 37), and the enzyme from L-180 has been expressed as an active form in Escherichia coli (24).

Fibrinogen and fibrin play essential roles in blood clotting, cellular and matrix interactions, inflammation, wound healing, and neoplasia (30). During coagulation, the soluble fibrinogen is converted to insoluble fibrin, and this process is initiated by thrombin, a serine protease, which catalyzes the cleavage of fibrinopeptides A and B from Aα and Bβ chains, respectively. Upon release of the fibrinopeptides, the remaining fibrin monomers aggregate spontaneously to form ordered fibrin polymers (42). Factor XIIIa then introduces intermolecular covalent [ɛ-(γ-Glu)Lys] isopeptide bonds into these polymers, creating γ-dimers. This is followed by the formation of cross-links between complementary sites on α chains and among γ-dimers, completing the mature network structure (31). During fibrinolysis, the fibrin polymer is converted into soluble product by the action of plasmin, which is generated from plasminogen by urokinase and tissue plasminogen activator (tPA). The conversion of prothrombin to thrombin is one of the central reactions in blood clotting. Activation of prothrombin to mature thrombin in vivo occurs by the proteolytic action of the prothrombinase complex consisting of factor Xa and cofactors that include factor Va, Ca2+ ions, and phospholipids.

A number of proteases that can interfere with blood homeostasis have been purified and characterized from various sources. Some of these proteases are fibrinolytic enzymes capable of digesting fibrin and/or fibrinogen (4, 12, 15, 18, 32, 43), while others possess prothrombin-activating activities (5, 13, 14, 41, 44). Exogenous proteases with potent fibrinolytic activities are considered to be a source of new therapeutic drugs for vascular disorders. Numerous reports are available from clinical incidents with coagulation disorders accompanying bacterial infections (1, 3, 8, 19). The protease from V. vulnificus L-180 has been shown to induce hemorrhagic tissue damage (22, 25) and to interact with a variety of human plasma proteins, including fibrinogen and α1-proteinase inhibitor (23). This protease could rapidly digest the Aα chain of fibrinogen with no clot formation. Although the protease from V. vulnificus ATCC 29307 has previously been studied (16), no properties relating to prothrombin activation, fibrinolysis, enzyme stability, and cleavage sites have been reported.

In this report, we describe the properties of this protease with emphasis on its prothrombin activation and fibrinolytic activities and show that it is a broad-specificity protease that can actively cleave various blood clotting-associated proteins. We also present three cleavage sites obtained from fragments generated from the cleavage of prothrombin and plasminogen.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

V. vulnificus strain ATCC 29307 was routinely cultivated in LB broth with 0.5% NaCl. Human prothrombin and antithrombin III were obtained from CalBiochem (Darmstadt, Germany). Human factor Xa, plasminogen, and plasmin were purchased from Roche Applied Science (Indianapolis, IN). Goat polyclonal antibody raised against thrombin was obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Anti-goat peroxidase-conjugated immunoglobulin G (IgG) was obtained from Jackson ImmunoResearch (West Grove, PA). The synthetic chromogenic substrate Boc-VPR-pNA was a kind gift from T. Morita (Meiji Pharmaceutical University, Tokyo, Japan). Other chromogenic substrates were obtained from Chromogenix (Milan, Italy). Human fibrinogen, α-thrombin, factor XIIIa, bovine serum albumin (BSA), gamma globulin, and all other chemicals were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). All chromatography columns were obtained from Amersham Biosciences (Uppsala, Sweden). Polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane was purchased from Bio-Rad (Richmond, Calif.).

Purification of protease.

The culture supernatant of V. vulnificus ATCC 29307 was collected by centrifugation at 10,000 × g at 4°C for 30 min, and ammonium sulfate was added to 70% saturation. The resulting precipitate was collected by centrifugation at 16,000 × g at 4°C for 40 min. The pellet was dissolved in 25 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) and desalted on PD-10 columns (Amersham Biosciences) equilibrated with the same buffer. The desalted sample was applied to a HiPrep 16/10 QFF column (Amersham Biosciences) preequilibrated with the same buffer. The column was eluted at room temperature with a linear gradient of NaCl from 0 to 0.5 M in the same buffer. Fractions containing major protease activities were pooled, concentrated by ultrafiltration using an Amicon YM 10 membrane (Millipore, Billerica, MA), and then further fractionated on a Superdex 75 100/300 GL gel filtration column (Amersham Biosciences) at room temperature. Fractions with major protease activities were pooled, concentrated, and used as the purified enzyme. The purified enzyme will henceforth be referred to as vEP.

Protease activity assay.

Protease activity was assayed with azocasein as a substrate. Sample mixture (total 200 μl) containing enzyme, 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), and 0.25% azocasein was incubated at 37°C for 15 min. The reaction was terminated by addition of 100 μl of 10% trichloroacetic acid. After centrifugation at 13,000 × g for 10 min, 200 μl of the supernatant was withdrawn and the absorbance was measured at 440 nm. One unit of protease activity was defined as the amount of enzyme that catalyzes the proteolysis of 1 μg of azocasein per min under the conditions described. Determination of protease activity assayed with synthetic chromogenic substrates was performed in a 96-well plate reader (Molecular Devices). A reaction mixture (total 100 μl) containing enzyme, 0.4 mM chromogenic substrate, 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 0.1 mg/ml BSA, and 0.9% NaCl was incubated at 37°C, and the absorbance at 405 nm was continuously monitored over a period of 30 min. To study the effects of protease inhibitors and divalent cations on vEP activity, the enzyme was assayed with azocasein under the conditions described above, but with 1 mM of protease inhibitor or cation.

Prothrombin activation.

For the detection of prothrombin activation, 200 μl of reaction mixture containing 0.4 mg/ml prothrombin and 4 μg/ml vEP in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) was incubated at room temperature and 24-μl aliquots were withdrawn at different time intervals. The reaction was stopped by addition of 1 μl of 24 mM NiCl2. To measure the thrombin activity, 10 μl of this sample was assayed in the presence of 0.4 mM Boc-VPR-pNA in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 0.9% NaCl, 1 mM NiCl2, and 0.1 mg/ml BSA in a 100-μl reaction volume at 37°C using a 96-well plate reader. The increase in absorbance at 405 nm due to the release of pNA was recorded over a period of 10 min. For the detection of fibrin polymerization, 10 μl of the prothrombin digest was mixed with 190 μl of 25 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.5) containing 100 μg of fibrinogen and 1 mM NiCl2, and the change in turbidity was measured at 350 nm. To study the effect of antithrombin III on the activity of vEP-activated prothrombin, the prothrombin was digested with vEP for just 10 min at room temperature under the same conditions as described above, and the reaction was terminated by addition of NiCl2 to 1 mM, from which 10-μl samples were taken and assayed in a 100-μl volume containing 0.4 mM Boc-VPR-pNA with different concentrations of antithrombin III.

Fibrinolytic activity assay.

Fibrinolytic activity was measured using fibrin plates. The fibrin plate was prepared by mixing 2 ml of 1% fibrinogen in 25 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.5) with 2 ml of 1% agarose (also dissolved in the same buffer) and 70 μl of 100 U/ml thrombin. The plate was allowed to set for 2 h at room temperature. Samples were applied into the wells (3 mm in diameter) made in the plate, and the plate was incubated at room temperature for overnight. Fibrinolytic activity was also assayed by measuring the decrease in turbidity of fibrin polymer in a 96-well plate using a spectrophotometric method. Ninety microliters of 1 mg/ml fibrinogen in 25 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.5) was added to 10 μl thrombin (10 U/ml), and the fibrin polymer was allowed to form at room temperature for 1 h. Thereafter, 10 μl of vEP (0.6 μg) or plasmin (1 μg) was added to the polymer and incubated for 30 min at room temperature. The decrease in absorbance at 350 nm was then recorded with a 96-well plate reader (Molecular Devices).

Factor XIIIa-catalyzed cross-linking of fibrin.

Fifteen microliters of reaction mixture containing 10 μg of fibrinogen, 0.02 U of thrombin, 0.002 U of factor XIIIa, and 1 mM CaCl2 in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) was incubated at room temperature for 1 h. For the detection of vEP-cleaved cross-linked fibrin, 5 μl of 0.1 mg/ml vEP was added to the sample and incubated at room temperature for 30 min. The reaction was terminated by addition of an equal volume of 2× sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) sample buffer followed by heating at 100°C for 1 min and then electrophoresed on 8% SDS-polyacrylamide gel.

SDS-PAGE and Western blotting.

SDS-PAGE was performed according to the method of Laemmli (17). Samples to be analyzed were mixed with equal volumes of 2× SDS-PAGE sample buffer, heated at 100°C for 1 min, and then loaded onto the gel. After electrophoresis, protein bands were visualized by staining the gel with Coomassie blue. For Western blot analysis, protein samples were subjected to SDS-PAGE and then transferred to a PVDF membrane. The membrane was blocked at room temperature for 2 h with blocking solution (phosphate-buffered saline [PBS] containing 5% skim milk and 0.1% Tween 20) and then incubated with goat polyclonal antibody against thrombin diluted in the blocking solution (1:1,000) for 1 h. The blot was washed and incubated with a 1:5,000 dilution of peroxidase-conjugated anti-goat IgG antibody for 1 h. The blot was washed, treated with ECL Western blotting detection reagents (Amersham Biosciences), and exposed to Hyperfilm EL (Amersham Biosciences).

Protein assay.

Protein concentrations were determined with Bradford reagent (Sigma) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

N-terminal sequencing.

Protein samples were subjected to electrophoresis on 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel. After electrophoresis, proteins were transferred to PVDF membrane in 10 mM 3-(cyclohexylamino)-1-propanesulfonic acid (CAPS) buffer (pH 11) containing 10% methanol. The blot was stained with Coomassie blue, followed by destaining. Target bands were excised from the blot and subjected to N-terminal sequencing using an Applied Biosystem Precise Sequencer (Applied Biosystem) as described elsewhere.

Mass spectrometry.

The protein sample was desalted in water by column chromatography using a PD-10 column. The desalted sample was concentrated by ultrafiltration using a YM 10 membrane and then diluted 10-fold with water and further concentrated using a Microcon centrifugal unit with a YM 10 membrane (Millipore). The sample was then subjected to matrix-assisted laser desorption-ionization time of flight (MALDI-TOF) analysis as performed by the Korean Basic Research Institute (Seoul, Korea).

RESULTS

Purification of vEP.

Approximately 0.5 mg of protease was obtained from 2 liters of culture supernatant. The purified vEP had a specific activity of 9,110 U/mg of protein, which represents approximately a fourfold increase over the culture supernatant. The purified protease reported by Kothary and Kreger (16) achieved less than a twofold increase in specific activity over the culture supernatant. Table 1 summarizes the results of the purification. The purified enzyme eluted as a single peak on Superdex 75 100/300 GL gel filtration column. However, on SDS-PAGE, it exhibited two bands, a minor band and a major band with apparent molecular masses of about 48-kDa and 36-kDa, respectively (Fig. 1). N-terminal sequencing showed that both bands have the same N-terminal sequence (AQADGTGPGGNSKTGRYEFGTD), and therefore they belong to the same polypeptide but have different lengths at the C termini. The N-terminal sequence reported by Kothary and Kreger (16) has an asparagine as the fourth residue instead of an aspartate. The presence of an aspartate at this position is confirmed by the DNA sequence (11). Mass spectrometry analysis by MALDI-TOF gave a mass of 34,077.37 Da (data not shown).

TABLE 1.

Summary of the purification of vEP

| Fraction | Total protein (mg) | Total activity (U)a | Sp act (U/mg) | Yield (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Supernatant | 38 | 88,900 | 2,340 | 100 |

| (NH4)2SO4 | 21 | 62,200 | 2,960 | 70 |

| Hi-Prep O | 1.2 | 8,100 | 6,750 | 9.1 |

| Superdex 75 | 0.56 | 5,100 | 9,110 | 5.7 |

One unit is defined as the amount of enzyme that catalyzes the proteolysis of 1 μg of azocasein per min.

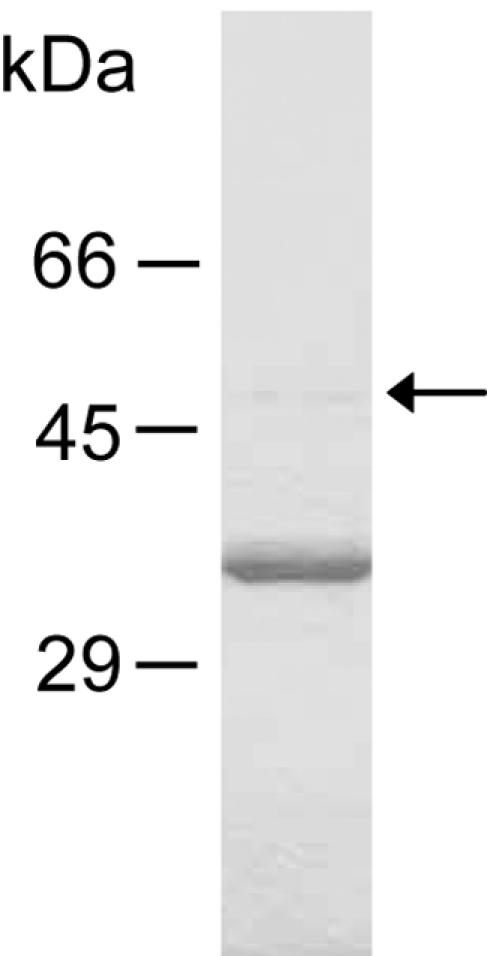

FIG. 1.

SDS-PAGE analysis of purified vEP. vEP resolved from the Superdex 75 100/300 GL column was electrophoresed on 10% gel under reducing conditions. An arrow indicates the presence of the 48-kDa band, which has the same N terminus as the 36-kDa band.

Protease activity.

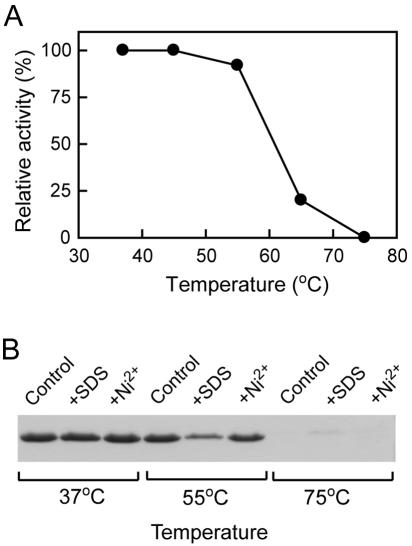

vEP exhibited an optimal activity around pH 7.5 ∼8.0, as determined with azocasein as a substrate. The enzyme underwent complete autodegradation within 10 min of incubation at 37°C at pH 4.0 (data not shown). vEP is therefore regarded as a neutral protease. The Km for azocasein was determined to be 0.49 ± 0.02 mg/ml. Assay with chromogenic substrates yielded little or no activity with all substrates tested: S-2222 (substrate for factor Xa), S-2251 (for plasmin), S-2288 (for general serine proteases), S-2444 (for urokinase), S-2586 (for chymotrypsin), S-2765 (for factor Xa and trypsin), and Boc-VPR-pNA (for thrombin). vEP exhibited a temperature-dependent loss of activity when the enzyme was incubated for 20 min at temperatures above 55°C (Fig. 2A). The loss of enzyme activity was directly related to the autodegradation of vEP at high incubation temperature (Fig. 2B). The presence of 0.5% SDS or 1 mM Ni2+ did not prevent autodegradation at 75°C. Interestingly, the presence of 0.5% SDS appeared to cause some degradation even at 55°C (Fig. 2B).

FIG. 2.

Effect of temperatures on vEP activity. (A) vEP was incubated at various temperatures for 20 min, and the residual activity toward azocasein was measured as described in Materials and Methods. Enzyme activity from each sample was expressed as a percentage relative to that of sample incubated at 37°C. (B) SDS-PAGE analysis of vEP incubated at different temperatures in the absence or presence of 0.5% SDS or 1 mM Ni2+.

Effect of inhibitors and cations on protease activity.

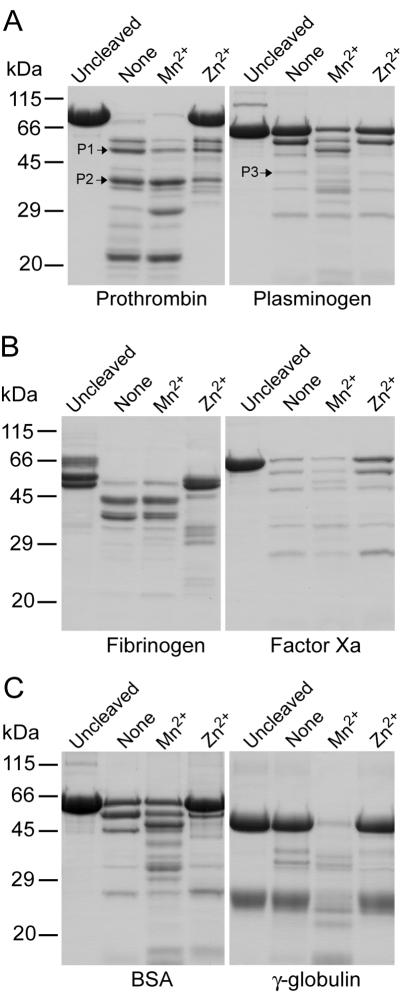

To confirm that vEP belongs to the metalloprotease class, the protease activity of vEP was assayed in the presence of various protease inhibitors. Inclusion of 1 mM 1,10-phenanthroline (metalloprotease inhibitor) in the assay completely abolished enzyme activity (Table 2). EDTA and EGTA also significantly inhibited the enzyme activity, whereas other protease inhibitors tested (aprotinin, diisopropyl fluorophosphate [DFP], leupeptin, phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride [PMSF], Nα-p-tosyl-l-lysine-chloromethyl ketone [TLCK], and N-tosyl-l-phenylalanine chloromethyl ketone [TPCK]) had no effect, thus confirming that vEP is a metalloprotease. The effect of cations on vEP activity was also studied. Addition of 1 mM Ca2+, Mg2+, or Mn2+ appeared to have no significant effects, whereas inclusion of 1 mM Cu2+, Ni2+, or Zn2+ was highly inhibitory (Table 2). However, at a low concentration (0.1 mM), Zn2+ did not inhibit vEP activity. The effects of Mn2+ and Zn2+ on vEP activity were also tested using four different blood clotting-associated proteins, prothrombin, plasminogen, fibrinogen, and factor Xa, as well as BSA and gamma globulin, which are not associated with blood clotting. Except for plasminogen, Zn2+ was inhibitory in the cleavage of all substrates tested, but the inhibition was much less in the case of factor Xa cleavage (Fig. 3). Noticeable stimulation by Mn2+ was observed for the cleavage of all substrates. The strongest stimulation relative to that of the control (no addition of metal ion) was observed for the cleavage of gamma globulin (Fig. 3C).

TABLE 2.

Effects of protease inhibitors and metal ions on vEP activity

| Additivea | Activity (%)b |

|---|---|

| Control | 100 |

| EDTA | 45 |

| EGTA | 11 |

| DTT | 27 |

| 1,10-Phenanthroline | 0 |

| Ca2+ | 107 |

| Cu2+ | 5 |

| Mg2+ | 106 |

| Mn2+ | 83 |

| Ni2+ | 11 |

| Zn2+ | 19 |

| Aprotinin | 93 |

| DFP | 100 |

| Leupeptin | 93 |

| PMSF | 100 |

| TLCK | 100 |

| TPCK | 95 |

The final concentration for each additive is 1 mM, except for aprotinin, which is 0.5 mM. DFP, diisopropyl fluorophosphate; DTT, dithiothreitol; EDTA, ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid; EGTA, ethylene glycol-bis(2-aminoethyl ether)-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid.

vEP activity was assayed with azocasein as the substrate with or without corresponding additive at 37°C for 15 min.

FIG. 3.

SDS-PAGE showing the substrate specificity of vEP. Corresponding proteins (10 μg each) as indicated were digested with 0.3 μg vEP in the presence or absence of 1 mM Mn2+ or Zn2 and then separated on 12% gel. Prothrombin (A) was digested for 5 min at room temperature. Fibrinogen (B) was digested for 20 min at room temperature. Plasminogen (A), factor Xa (B), and BSA and gamma globulin (C) were digested for 60 min at 37°C. P1, P2, and P3 indicate fragments from which the N-terminal sequences have been determined.

Three cleavage sites were determined from N-terminal sequencing of fragments generated from the cleavage of prothrombin (P1 and P2 in Fig. 3A) and plasminogen (P3 in Fig. 3A). The sequences for P1, P2, and P3 were Phe208-Asn-Ser-Ala-Val-Gln, Ala273-Thr-Ser-Glu-Tyr-Gln, and Leu81-Ser-Glu-Cys-Lys-Thr, respectively.

Prothrombin activation by vEP.

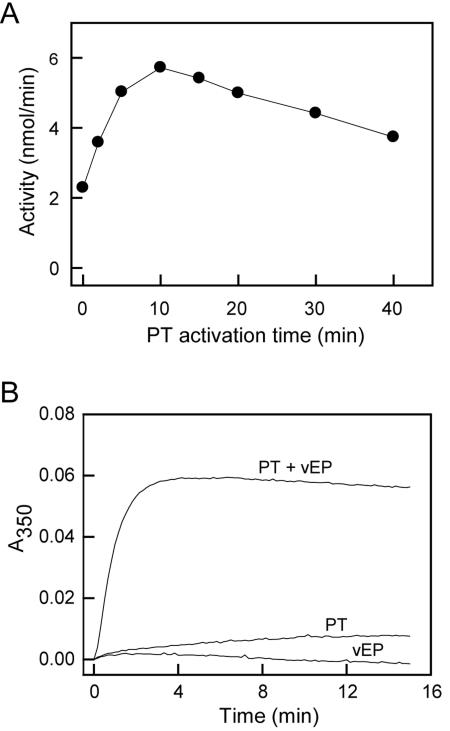

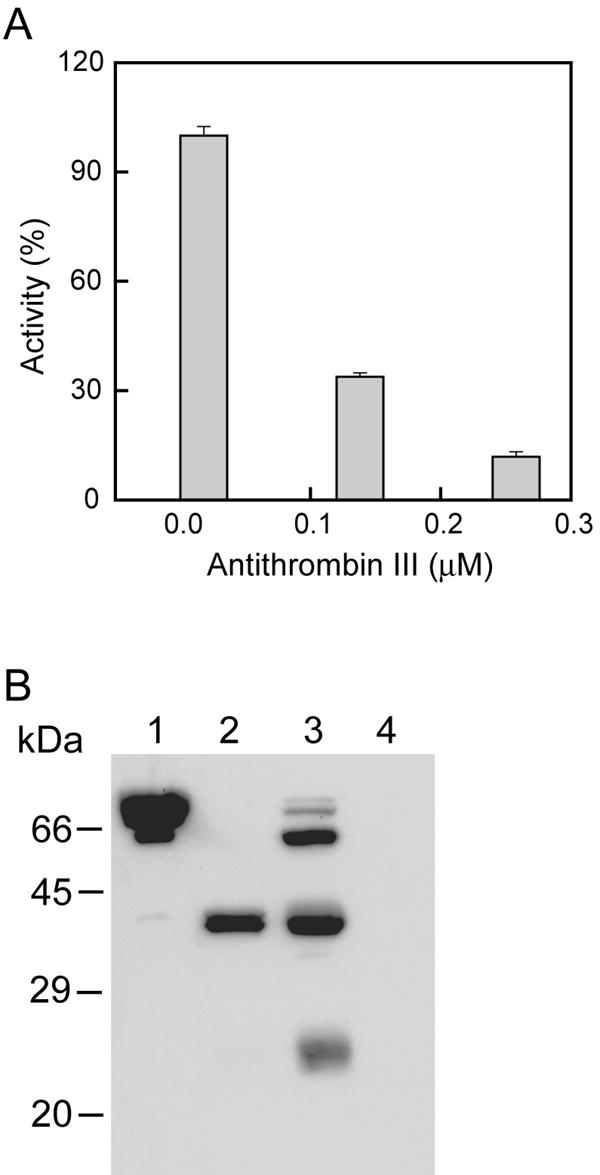

Prothrombin was a very efficient substrate for vEP, with extensive cleavage occurring at room temperature within 10 min of incubation (Fig. 3A). Activity assay for the cleavage products using the thrombin-specific chromogenic substrate Boc-VPR-pNA revealed the presence of activity that peaked at about 10 min of cleavage time under the conditions employed and then started to drop beyond that time point (Fig. 4A). No detectable activity was observed with prothrombin in the absence of vEP (data not shown). The activated enzyme could also catalyze the formation of fibrin polymer from fibrinogen as detected by an increase in turbidity at 350 nm (Fig. 4B). Production of a functional thrombin was further confirmed by inhibitor study using antithrombin III (Fig. 5A) and by Western blot analysis using antibody that was raised against an internal region of thrombin (Fig. 5B). A major band corresponds to that of thrombin was detected by the antibody.

FIG. 4.

Activation of prothrombin by vEP. (A) Thrombin activity was measured with thrombin-specific chromogenic substrate. Prothrombin (PT; 0.4 mg/ml) was activated by vEP (4 μg/ml) at room temperature, aliquots were withdrawn at different time intervals, and the reaction was stopped by the addition of NiCl2 to 1 mM. The cleavage products were assayed for thrombin activity in the presence of 1 mM NiCl2 and 0.4 mM of Boc-VPR-pNA at 37°C. (B) Thrombin activity was assayed by measuring the degree of fibrin formation. Prothrombin activated by vEP for 10 min was mixed with fibrinogen (0.5 mg/ml) in the presence of 1 mM NiCl2, and the formation of fibrin polymer was monitored as an increase in turbidity at 350 nm. For controls, the reaction mixture contained only prothrombin (20 μg/ml) or vEP (0.2 μg/ml). Representative curves from each reaction performed two times in triplicate are shown.

FIG. 5.

(A) Effect of antithrombin III on the activity of vEP-activated prothrombin. Prothrombin (0.4 mg/ml) was activated by vEP (4 μg/ml) at room temperature for 10 min, and the reaction was terminated by addition of 1 mM NiCl2. Aliquots were then assayed with Boc-VPR-pNA (0.4 mM) as a substrate in the presence or absence of antithrombin III. Data are the means ± standard errors from two separate experiments performed in triplicates. (B) Western blot analysis of vEP-activated prothrombin. vEP-activated prothrombin was subjected to SDS-PAGE under nonreducing conditions. The proteins were transferred to PVDF membrane and probed with antibody against thrombin. Lane 1, prothrombin; lane 2, thrombin; lane 3, vEP-activated prothrombin; lane 4, vEP only.

Fibrinolytic activity.

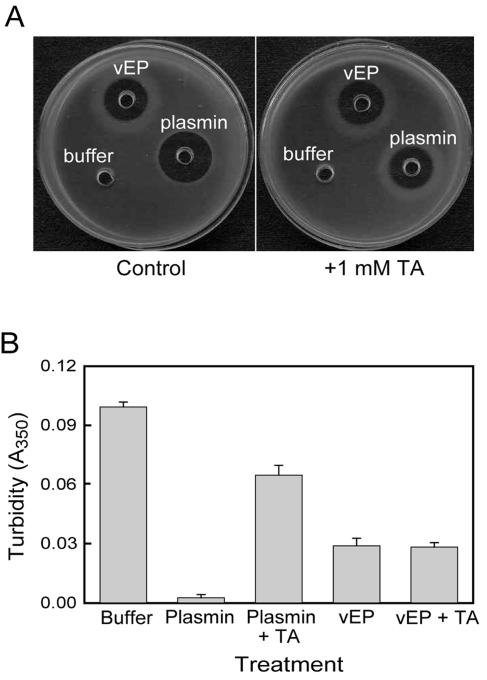

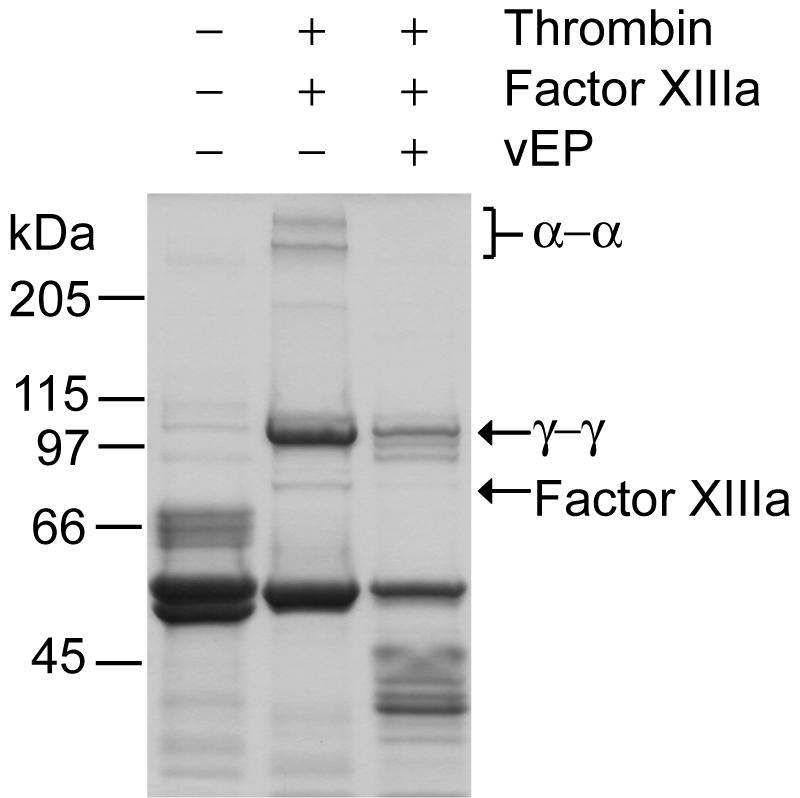

vEP cleaved all three major chains of fibrinogen, but lesser cleavage was observed for the γ chain (Fig. 3B). The fibrinolytic activity of vEP was further demonstrated by the cleavage of fibrin polymer catalyzed by thrombin (Fig. 6). The cleavage of fibrin polymer was insensitive to tranexamic acid (TA), which is a plasmin inhibitor. In addition to the cleavage of fibrin polymer, vEP could also cleave the cross-linked fibrins formed by factor XIIIa (Fig. 7). Both the α-α and γ-γ chains of fibrins were susceptible to cleavage by vEP.

FIG. 6.

Fibrinolytic activity of vEP. (A) Fibrinolytic activity was assayed on fibrin plate. Samples were applied to the wells in the plate and allowed to incubate at room temperature overnight. (B) Fibrinolytic activity was measured by a decrease in the turbidity of fibrin polymer. Enzymes were applied as spots onto the fibrin polymer (catalyzed by thrombin with fibrinogen as substrate) and allowed to incubate at room temperature for 30 min. The decrease in turbidity was then measured at 350 nm. The data are the means ± standard error from two separate experiments performed in triplicate.

FIG. 7.

Cleavage of α- and γ-chain cross-links of fibrin by vEP, as analyzed by SDS-PAGE. Polymerization of fibrin was initiated by the addition of fibrinogen (1.3 mg/ml), thrombin (1.3 U/ml), and factor XIIIa (0.13 U/ml) and 1 mM CaCl2 followed by incubation at room temperature for 1 h. The cross-linked fibrin was then digested with vEP (25 μg/ml) at room temperature for 30 min followed by SDS-PAGE analysis using 8% gel.

DISCUSSION

The proteolytic activity of V. vulnificus has been characterized as elastase, collagenase, and caseinase (16, 20, 24). One distinguishing feature of this protease and a related protease from Vibrio fluvialis (29) is that the purified enzyme can present in two forms: a 45-kDa enzyme and a 35-kDa enzyme. The 35-kDa enzyme is thought to be a result of further processing of the C terminus of the 45-kDa form. The precise cleavage site within the C terminus of the 45-kDa form induced by the autocleavage action of the enzyme has not been determined for the protease from either species. Through studying the recombinant enzyme from V. vulnificus L-180 expressed in E. coli, Miyoshi and coworkers (24) reported that both the 45-kDa and 35-kDa forms have similar proteolytic activities, but the 35-kDa enzyme exhibits markedly reduced activity only toward insoluble proteins such as collagen and elastin. vEP obtained from the purification described in this study consists mainly of the smaller form, with a negligible amount of the larger form (Fig. 1). The purified enzyme described by Kothary and Kreger (16) exhibited two major bands of 50 kDa and 42 kDa, whereas the enzyme described in this study consisted of a minor band of 48 kDa and a major band of 36 kDa. We believe that these are the same bands, with the differences due probably to different experimental conditions employed.

vEP is a protease that appears to lack specificity in terms of substrates and their cleavages. The results obtained from chromogenic substrates revealed little or no activity with various peptides specific for other proteases. The cleavage sites determined from fragments derived from the cleavage of prothrombin and plasminogen showed that vEP cleaved Asp207-Phe208, Thr272-Ala273, and Tyr80-Leu81 bonds within the proteins. The cleavage points and the surrounding sequences were quite different among the three sites. This may explain the broad specificity of this enzyme and suggests that the sequences surrounding the cleavage point may be important for recognition and binding of substrates. It may also explain the lack of activity observed with the various peptide substrates specific for other proteases. For example, vEP could activate prothrombin but did not cleave S-2222, both of which are substrates for factor Xa. Plasminogen and S-2444 are substrates for urokinase, but vEP exhibited little activity toward S-2444, although it could readily cleave plasminogen. Although vEP belongs to a family of zinc-dependent metalloproteases and has the characteristic zinc-binding motif of HEXXH that is also found in other metalloproteases (28), a high concentration of Zn2+ can inhibit the enzyme activity whereas a high concentration of Mn2+ can increase its nonspecific proteolytic activity toward certain proteins. The possibility of redox active metal ion undergoing an oxidative chemical reaction to cleave the substrates can be ruled out since incubation of the substrates with only Mn2+ produced no cleavage (data not shown). The activation of enzyme activity by Mn2+ may be due to the influence of the metal ions on the substrates rather than on the enzyme, since the enhancement of proteolysis was only observed for some proteins, and of those proteins where the proteolysis was enhanced, a noticeable difference in the pattern of cleavage was also observed compare with that of the control (Fig. 3). The cause of enhancement in enzyme activity by Mn2+ remains to be elucidated by further study. The inhibition of enzyme activity by excess Zn2+ has been reported for other proteases: e.g., thermolysin (9) and carboxypeptidase (6). X-ray crystallography study has shown that the excess Zn2+ ions bind to additional sites close to the native Zn2+ in both enzymes and thereby inhibit proteolysis by exclusion of the substrate from the active site (6, 9). The same mechanism of inhibition may also apply to vEP.

The possibility of vEP's involvement in blood coagulation is demonstrated by its prothrombin activation ability, leading to cleavage of fibrinogen and formation of fibrin polymer, including cross-linked fibrins. The product of prothrombin activation was confirmed by an enzyme activity assay using a thrombin-specific peptide substrate, fibrinogen, and a thrombin inhibitor, antithrombin III, as well as Western blotting with antithrombin antibody. The decrease of thrombin activity with time showed that the formation of thrombin was transient. As vEP could also cleave thrombin (data not shown), the decrease in thrombin activity with time may be due to further degradation of thrombin by vEP after its generation from prothrombin. Activation of prothrombin by vEP was proteolysis dependent, leading to the loss of active thrombin with time. Certain microbial enzymes such as staphylocoagulase initiate blood coagulation by conformational activation of prothrombin (33). The activation of prothrombin by vEP is Ca2+ independent, whereas the activation of prothrombin by enzymes such as factor Xa and a CA-1 from snake venom (44) requires Ca2+. Recently, a metalloprotease purified from Aeromonas hydrophila was reported to have thrombin activation activity that is also Ca2+ independent (14). The activity of this protease is sensitive to Ca2+, with more than 95% inhibited by 0.5 mM Ca2+. Although Miyoshi and coworkers (23) have reported as an unpublished observation the generation of functional thrombin from prothrombin by V. vulnificus L-180 protease, the results presented in this study for vEP are the first to show in detail the activation of prothrombin by a V. vulnificus extracellular metalloprotease.

Fibrinolytic enzymes have been purified from fermented food (4, 12, 43), earthworms (32), and mushrooms (15) as well as snake venom (18). These enzymes, which consist of both serine proteases and metalloproteases, have been suggested to be useful as a source of oral fibrinolytic drug or for the processing of various foods of physiological importance, especially those purified from food sources. Recently, fibrinolytic enzymes in shark cartilage extract have been characterized. The fibrinolytic activities correlated with the presence of 58-kDa and 62-kDa proteases in the extract, which exhibited sensitivity to 1,10-phenanthroline, indicating that they are metalloproteases (34). The fibrinolytic activity of vEP is different from those reported for other fibrinolytic enzymes because it is capable of digesting all three major chains (α, β, and γ) of fibrinogen as well as α-α and γ-γ fibrin chains (Fig. 7). Miyoshi and coworkers (23) reported that the protease from V. vulnificus L-180 only cleaves the Aα chain of fibrinogen. Both the Aα and Bβ chains could be cleaved by plasmin, whereas the γ chain is insensitive to both proteases. Certain fibrinolytic enzymes isolated from other sources also exhibit some degrees of specificity with respect to the cleavage of fibrinogen. For example, the enzymes isolated from viper snake venom cleave exclusively the Aα chain or Bβ chain of fibrinogen (18), while the enzyme isolated from shrimp paste cleaves the β or γ chain without affecting the Aα chain (43) or plasma proteins such as BSA, IgG, and thrombin. A metalloprotease purified from a wild mushroom, Tricholoma saponaceum, could cleave both the Aα and Bβ chains of fibrinogen but has no activity toward the γ chain or other plasma proteins, including BSA, IgG, and thrombin (15).

During bacterial infection, some bacteria or bacterial products can modulate the host response. The coagulation and fibrinolytic systems are targets for such modulation (39). The physiological significance of vEP as a prothrombin activator and fibrinolytic enzyme could be the dysfunction of the coagulation cascade system of human plasma following the bacterial infection. So far, except for α2-macroglobulin, there is no other known physiological inhibitor for this Vibrio metalloprotease (27). α2-Macroglobulin forms a complex with the protease through cleavage of the bait regions of all four α2-macroglobulin chains and elicitation of conformational change of the α2-macroglobulin molecule, which traps the protease. However, there has been no study linking the function of the secreted protease from Vibrio to its role in the systemic system during infection. In the case of intra-abdominal infections caused by E. coli and Bacteroides fragilis, it was shown that fibrinous exudates could incorporate large numbers of bacteria (35). Once the bacteria are sequestered within the fibrin deposit, they can continue to proliferate without being attacked by the host defense machinery, leading to the formation of abscesses. The prothrombin activation activity of vEP is rapid, a property that may prove useful for the invading Vibrio at the early state of infection. The activation of prothrombin would result in the cleavage of fibrinogen. The fibrin monomers generated can then become deposited in various organs, leading to microvascular and macrovascular thrombosis. The fibrin clot may also serve to entrap the bacteria and therefore protect them from host's phagocytosis—a strategy for avoiding the host defense machinery. However, in order for the bacteria to disseminate at a later stage, they need to break free of the fibrin clot, and this role might be achieved by the fibrinolytic activity of the vEP, which can dissolve the clot through proteolysis. By that time, the host defense would be greatly disrupted, and together with an increasing number of bacterial cells in the system, the infection could lead to host mortality. Furthermore, the activity of vEP toward extracellular matrix proteins such as collagen and elastin (data not shown) may facilitate the destruction of tissue during infection. The dual properties of vEP as a prothrombin activator and fibrinolytic enzyme as shown in this study emphasize the potential risk of these bacteria to interfere with the blood clotting process and use it as part of an overall strategy of the pathogenicity of V. vulnificus or other vibrios.

There is yet no direct evidence to indicate that the gene encoding vEP is expressed or repressed during infection by V. vulnificus (7). Studies employing animal models showed that when the purified protease is injected into animals, some of the pathology associated with V. vulnificus infection is reproduced (21, 26, 28). The role of this metalloprotease in virulence during infection of animals has been studied by two groups using mutants of V. vulnificus that do not produce the protease (11, 36). These investigators reported that the protease is not essential for V. vulnificus virulence in mice. However, the damage to host tissues that can be inflicted by the proteolytic activity of this enzyme may still be a significant side reaction during infection if the gene is expressed.

We have shown here the prothrombin activation and fibrinolytic activities of an extracellular metalloprotease from a clinical isolate of V. vulnificus in addition to its activity toward various plasma proteins. Although these properties of the enzyme may not represent the enzyme's true biological function, the generation of an active protease as a result of its broad-specificity action on a precursor protein is a significant event that could have important biological relevance.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Ministry of Science and Technology of Korea and the KOSEF through the Research Center for Proteineous Materials and by research funds from Chosun University, 2002.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bryant, A. E. 2003. Biology and pathogenesis of thrombosis and procoagulant activity in invasive infections caused by group A streptococci and Clostridium perfringens. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 16:451-462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chiang, S. R., and Y. C. Chuang. 2003. Vibrio vulnificus infection: clinical manifestations, pathogenesis, and antimicrobial therapy. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 36:81-88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fourrier, F., M. Jourdain, A. Tournois, C. Caron, J. Goudemand, and C. Chopin. 1995. Coagulation inhibitor substitution during sepsis. Intensive Care Med. 21(Suppl.):264-268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fujita, M., K. Nomura, K. Hong, Y. Ito, A. Asada, and S. Nishimuro. 1993. Purification and characterization of a strong fibrinolytic enzyme (nattokinase) in the vegetable cheese natto, a popular soybean fermented food in Japan. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 197:1340-1347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gao, R., R. Manjunatha Kini, and P. Gopalakrishnakone. 2002. A novel prothrombin activator from the venom of Micropechis ikaheka: isolation and characterization. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 408:87-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gomez-Ortiz, M., F. X. Gomis-Ruth, R. Huber, and F. X. Aviles. 1997. Inhibition of carboxypeptidase A by excess zinc: analysis of the structural determinants by X-ray crystallography. FEBS Lett. 400:336-340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gulig, P. A., K. L. Bourdage, and A. M. Starks. 2005. Molecular pathogenesis of Vibrio vulnificus. J. Microbiol. 43:118-131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hesselvik, J. F., M. Blomback, B. Brodin, and R. Maller. 1989. Coagulation, fibrinolysis, and kallikrein systems in sepsis: relation to outcome. Crit. Care Med. 17:724-733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Holland, D. R., A. C. Hausrath, D. Juers, and B. W. Matthews. 1995. Structural analysis of zinc substitutions in the active site of thermolysin. Protein Sci. 4:1955-1965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Janda, J. M., C. Powers, R. G. Bryant, and S. L. Abbott. 1988. Current perspectives on the epidemiology and pathogenesis of clinically significant Vibrio spp. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 1:245-267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jeong, K. C., H. S. Jeong, J. H. Rhee, S. E. Lee, S. S. Chung, A. M. Starks, G. M. Escudero, P. A. Gulig, and S. H. Choi. 2000. Construction of phenotypic evaluation of a Vibrio vulnificus vvpE mutant for elastolytic protease. Infect. Immun. 68:5096-5106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jeong, Y. K., W. S. Yang, K. H. Kim, K. T. Chung, W. H. Joo, J. H. Kim, D. E. Kim, and J. U. Park. 2004. Purification of a fibrinolytic enzyme (myulchikinase) from pickled anchovy and its cytotoxicity to the tumor cell lines. Biotechnol. Lett. 26:393-397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kaminishi, H., H. Hamatake, T. Cho, T. Tamaki, N. Suenaga, T. Fujii, Y. Hagihara, and H. Maeda. 1994. Activation of blood clotting factors by microbial proteinases. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 121:327-332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Keller, T., R. Seitz, J. Dodt, and H. Konig. 2004. A secreted metallo protease from Aeromonas hydrophila exhibits prothrombin activator activity. Blood Coagul. Fibrinolysis 15:169-178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim, J. H., and Y. S. Kim. 2001. Characterization of a metalloenzyme from a wild mushroom, Tricholoma saponaceum. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 65:356-362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kothary, M. H., and A. S. Kreger. 1987. Purification and characterization of an elastolytic protease of Vibrio vulnificus. J. Gen. Microbiol. 133:1783-1791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Laemmli, U. K. 1970. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 227:680-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leonardi, A., F. Gubensek, and I. Krizaj. 2002. Purification and characterization of two hemorrhagic metalloproteinases from the venom of the long-nosed viper, Vipera ammodytes ammodytes. Toxicon 40:55-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lorente, J. A., L. J. Garcia-Frade, L. Landin, R. de Pablo, C. Torrado, E. Renes, and A. Garcia-Avello. 1993. Time course of hemostatic abnormalities in sepsis and its relation to outcome. Chest 103:1536-1542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miyoshi, N., C. Shimizu, S. Miyoshi, and S. Shinoda. 1987. Purification and characterization of Vibrio vulnificus protease. Microbiol. Immunol. 31:13-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miyoshi, S., E. G. Oh, K. Hirata, and S. Shinoda. 1993. Exocellular toxic factors produced by Vibrio vulnificus. J. Toxicol. Toxin Rev. 12:253-288. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miyoshi, S., H. Nakazawa, K. Kawata, K.-I. Tomochika, K. Tobe, and S. Shinoda. 1998. Characterization of the hemorrhagic reaction caused by Vibrio vulnificus metalloprotease, a member of the thermolysin family. Infect. Immun. 66:4851-4855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miyoshi, S., H. Narukawa, K. Tomochika, and S. Shinoda. 1995. Actions of Vibrio vulnificus metalloprotease on human plasma proteinase-proteinase inhibitor systems: a comparative study of native protease with its derivative modified by polyethylene glycol. Microbiol. Immunol. 39:959-966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miyoshi, S., H. Wakae, K.-I. Tomochika, and S. Shinoda. 1997. Functional domains of a zinc metalloprotease from Vibrio vulnificus. J. Bacteriol. 179:7606-7609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miyoshi, S., K. Kawata, K. Tomochika, S. Shinoda, and S. Yamamoto. 2001. The C-terminal domain promotes the hemorrhagic damage caused by Vibrio vulnificus metalloprotease. Toxicon 39:1883-1886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miyoshi, S., K. Kawata, M. Hosokawa, K. Tomochika, and S. Shinoda. 2003. Histamine-releasing reaction induced by the N-terminal domain of Vibrio vulnificus metalloprotease. Life Sci. 72:2235-2242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miyoshi, S., and S. Shinoda. 1989. Inhibitory effect of alpha 2-macroglobulin on Vibrio vulnificus protease. J. Biochem. 106:299-303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miyoshi, S., and S. Shinoda. 2000. Microbial metalloproteases and pathogenesis. Microbes Infect. 2:91-98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miyoshi, S., Y. Sonoda, H. Wakiyama, M. M. Rahman, K. Tomochika, S. Shinoda, S. Yamamoto, and K. Tobe. 2002. An exocellular thermolysin-like metalloprotease produced by Vibrio fluvialis: purification, characterization, and gene cloning. Microb. Pathol. 33:127-134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mosesson, M. W. 1990. Fibrin polymerization and its regulatory role in hemostasis. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 116:8-17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mosesson, M. W., K. R. Siebenlist, D. L. Amrani, and J. P. DiOrio. 1989. Identification of covalently linked trimeric and tetrameric D domains in crosslinked fibrin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 86:1113-1117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nakajima, N., H. Mihara, and H. Sumi. 1993. Characterization of potent fibrinolytic enzymes in earthworm, Lumbricus rubellus. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 57:1726-1730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Panizzi, P., R. Friedrich, P. Fuentes-Prior, W. Bode, and P. E. Bock. 2004. The staphylocoagulase family of zymogen activator and adhesion proteins. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 61:2793-2798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ratel, D., G. Glazier, M. Provencal, D. Boivin, E. Beaulieu, D. Gingras, and R. Beliveau. 2005. Direct-acting fibrinolytic enzymes in shark cartilage extract: potential therapeutic role in vascular disorders. Thromb. Res. 115:143-162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rotstein, O. D. 1992. Role of fibrin deposition in the pathogenesis of intraabdominal infection. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 11:1064-1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shao, C.-P., and L.-I. Hor. 2000. Metalloprotease is not essential for Vibrio vulnificus virulence in mice. Infect. Immun. 68:3569-3573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shinoda, S., S. Miyoshi, H. Kakae, M. Rahman, and K. Tomochika. 1996. Bacterial proteases as pathogenic factors, with special emphasis on Vibrio proteases. J. Toxicol. Toxin Rev. 15:327-339. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tacket, C. O., F. Brenner, and P. A. Blake. 1984. Clinical features and an epidemiological study of Vibrio vulnificus infection. J. Infect. Dis. 149:558-561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tapper, H., and H. Herwald. 2000. Modulation of hemostatic mechanisms in bacterial infectious diseases. Blood 96:2329-2337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ulusarac, O., and E. Carter. 2004. Varied clinical presentations of Vibrio vulnificus infections: a report of four unusual cases and review of the literature. South. Med. J. 97:163-168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wegrzynowicz, Z., P. B. Heczko, G. R. Drapeau, J. Jeljaszewicz, and G. Pulverer. 1980. Prothrombin activation by a metalloprotease from Staphylococcus aureus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 12:138-139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Weisel, J. W., C. V. Stauffacher, E. Bullit, and C. Cohen. 1985. A model for fibrinogen: domains and sequence. Science 230:1388-1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wong, A. H., and Y. Mine. 2004. Novel fibrinolytic enzyme in fermented shrimp paste, a traditional Asian fermented seasoning. J. Agric. Food Chem. 52:980-986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yamada, D., F. Sekiya, and T. Morita. 1996. Isolation and characterization of a carinactivase, a novel prothrombin activator in Echis carinatus venom with a unique catalytic mechanism. J. Biol. Chem. 271:5200-5207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]