Abstract

Germination protease (GPR) initiates the degradation of small, acid-soluble spore proteins (SASP) during germination of spores of Bacillus and Clostridium species. The GPR amino acid sequence is not homologous to members of the major protease families, and previous work has not identified residues involved in GPR catalysis. The current work has focused on identifying catalytically essential amino acids by mutagenesis of Bacillus megaterium gpr. A residue was selected for alteration if it (i) was conserved among spore-forming bacteria, (ii) was a potential nucleophile, and (iii) had not been ruled out as inessential for catalysis. GPR variants were overexpressed in Escherichia coli, and the active form (P41) was assayed for activity against SASP and the zymogen form (P46) was assayed for the ability to autoprocess to P41. Variants inactive against SASP and unable to autoprocess were analyzed by circular dichroism spectroscopy and multiangle laser light scattering to determine whether the variant's inactivity was due to loss of secondary or quaternary structure, respectively. Variation of D127 and D193, but no other residues, resulted in inactive P46 and P41, while variants of each form were well structured and tetrameric, suggesting that D127 and D193 are essential for activity and autoprocessing. Mapping these two aspartate residues and a highly conserved lysine onto the B. megaterium P46 crystal structure revealed a striking similarity to the catalytic residues and propeptide lysine of aspartic acid proteases. These data indicate that GPR is an atypical aspartic acid protease.

During the first minutes of germination of spores of Bacillus species, 10 to 20% of the spore's total protein is degraded to amino acids (26). The majority of the degraded protein is a group of small, acid-soluble spore proteins (SASP), some of which (α/β type; SASP-A and -C in Bacillus megaterium) bind to the spore's DNA and contribute to its resistance against heat and UV radiation (14, 22, 23, 26). Another SASP subtype (γ type; SASP-B in B. megaterium) does not bind spore DNA but rather, along with the α/β type SASP, serves as an important amino acid reserve in the mature spore (4). Germination protease (GPR) initiates SASP degradation by cleaving these proteins at one or two sites, depending on the SASP subtype, thereby freeing the spore's DNA and ultimately providing amino acids for metabolism and protein synthesis in spore outgrowth (26).

GPR is a sequence-specific endoprotease that is synthesized as an inactive zymogen (P46) during sporulation at about the same time as its SASP substrates (26). Just prior to the completion of sporulation, GPR undergoes an autoprocessing reaction which removes an N-terminal propeptide of 5 to 15 amino acids, depending on the species (13, 21). This process results in an enzyme (P41) that is active in vitro but does not cleave SASP in vivo due to the relatively low water content in the core of the developing and dormant spore (7, 13, 21). In vitro, autoprocessing is triggered by pyridine-2,6-dicarboxylic acid (dipicolinic acid [DPA]) and decreases in pH and hydration level (6). The latter two conditions mimic those within the developing spore at the time of P46 autoprocessing, which also parallels the accumulation of an enormous depot of DPA by the developing spore (6-8, 19, 21). Analysis of GPR autoprocessing in various spo mutants is consistent with this DPA accumulation being essential for autoprocessing (19), while further in vitro studies showed that 50% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and a mildly acidic pH are sufficient to cause GPR zymogen autoprocessing (8), suggesting that autoprocessing requires some type of conformational change in P46.

GPR is primarily homotetrameric, both as P46 and as P41, and is only active as such (12). The only detailed structural information on GPR is from the crystal structure of B. megaterium P46 (18), and consequently the details of structural changes that occur during the P46 to P41 conversion are not known. Conversion of P46 to P41 is not accompanied by a large change in GPR's secondary structure, as the circular dichroism (CD) spectra of P46 and P41 are very similar (11) (see below). However, structural changes do take place in this conversion, as P41's sensitivity to trypsin digestion and thermal unfolding as well as the reactivity of the single cysteine residue in B. megaterium P41 are markedly higher than with P46 (8). An alternative explanation is that the removal of the propeptide directly causes increased dissociation of P41 monomers by disrupting the monomer-monomer interface. However, most of GPR's propeptide is necessary neither for the maintenance of inactivity nor for structural stability, as a B. megaterium GPR zymogen variant lacking up to 10 propeptide amino acids autoprocesses normally (16).

Although GPR is clearly an endoprotease, analysis of GPR's primary sequence by the program ScanProsite (3) indicates that this enzyme does not contain any of the consensus sequences common to serine, aspartic acid, cysteine, or metalloproteases. GPR also does not appear structurally similar to the recently established glutamate/glutamine protease family, Eqolisin (2). GPR's active site has been localized to the N-terminal two-thirds of P41, since the trypsin-mediated removal of the C-terminal one-third of the protein does not eliminate activity (15). Site-directed mutagenesis of B. megaterium gpr has also ruled out a number of residues as contributing to catalysis, including four serines and GPR's only cysteine (15). In addition, a variety of studies on the potential metal dependence of GPR have provided no evidence that it is a metalloprotease (15), although it has been suggested that a metal ion (or ions) plays a role in substrate recognition by GPR based on structural homology modeling of GPR with another protease (17).

As indicated above, the available data are clearly not sufficient to allow the assignment of GPR to one of the five classes of proteases. We have undertaken site-directed mutagenesis of potential nucleophilic residues in GPR in order to identify the catalytic amino acids of this novel protease and provide insight into P46 inactivity and autoprocessing.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacteria and plasmids.

Both the full-length B. megaterium gpr gene (gpr-46) (28) and a truncated form encoding only P41 (gpr-41) (7) have been cloned and subsequently subcloned into the pET23a vector (Novagen/EMD Biosciences, Inc., San Diego, CA). All mutations in gpr-46 and gpr-41 were generated in the pET23a vector (Novagen) carrying the appropriate B. megaterium gpr gene. The pET23a plasmid was chosen for its C-terminal His6 tag that allowed a straightforward and high-yield purification of the various forms of GPR by use of Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid agarose beads (see below). Plasmids were maintained in XL1-Blue Escherichia coli cells (Stratagene, Cedar Creek, TX). BL21(DE3) pLysS E. coli cells (Stratagene) were used for overexpression of P46 and P41 variants.

Site-directed mutagenesis.

The Quickchange system (Stratagene) was used to create all mutants. The composition of PCR mutagenesis reactions run on an Applied Biosystems GeneAmp PRC system 9700 thermocycler were as follows: 5 μl of 10× Pfu Turbo polymerase buffer (Stratagene); 125 nM each of dATP, dTTP, dGTP, and dCTP; 125 ng of each primer; 10 ng plasmid pET23a carrying either gpr-46 or gpr-41; 1 μl DMSO; H2O to 49 μl; and 1 μl (2.5 U) Pfu Turbo polymerase (Stratagene). Following PCR, the reactions were incubated with 1.5 μl (9 U) of DpnI (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) for 1.5 h to selectively digest the methylated parent plasmids, and the resulting PCR products were analyzed by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis. Productive reactions were transformed into XL1-Blue competent E. coli cells with selection for resistance to ampicillin (100 μg/ml), and successful mutagenesis was confirmed by sequencing of plasmid DNA. Mutated plasmids were transformed into BL21(DE3) pLysS E. coli cells with selection for resistance to ampicillin (100 μg/ml) and chloramphenicol (20 μg/ml) for protein overexpression.

Site-directed deletion.

Deletion mutations of the putative inhibitory loop in P46 were generated by a modification of the standard Quickchange (Stratagene) procedure as described previously (29). In this modified procedure, complementary primers are constructed to contain the DNA sequence flanking the region to be deleted rather than a single base change to mediate an amino acid substitution as described above. Each primer was then added to separate reaction mixtures, and a single round of PCR was carried out. After the extension period, the reactions were pooled and the remainder of the PCR was conducted as described above.

Protein overexpression and purification.

BL21(DE3) pLysS E. coli cells carrying gpr mutants were grown overnight at 37°C in 3 ml of Luria-Bertani medium (NaCl, 5 g/liter; tryptone, 10 g/liter; yeast extract, 5 g/liter; and 1 ml 1 N NaOH) containing 100 μg/ml ampicillin and 20 μg/ml chloramphenicol, with shaking. Fifty milliliters of Luria-Bertani medium with the latter antibiotics was inoculated with the overnight culture and grown at 37°C with shaking, and GPR expression was induced at an optical density at 600 nm of 0.7 by the addition of isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside to 1 mM. After incubation for a further 1.5 h at 37°C with shaking, cultures were centrifuged (10 min; 3,220 × g), the pellet was resuspended on ice in 1.5 ml lysis buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4], 5 mM CaCl2, 10% glycerol) plus 40 mM imidazole, and cells were broken by sonication in the presence of ∼70 mg of 0.1-mm glass beads. The rest of the procedure was carried out in the cold room at ∼4°C. The broken cells were centrifuged (10 min; 3,000 × g), and the supernatant fluid was added to a 1.5-ml Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid agarose (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA) column equilibrated with lysis buffer plus 40 mM imidazole. The column was washed with 5 ml lysis buffer plus 40 mM imidazole and then eluted with 5 ml lysis buffer plus 50 mM imidazole and finally with 5 ml lysis buffer plus 150 mM imidazole. The last two eluates were combined and concentrated to 1 ml in a 15-ml Centriprep centrifugal filter unit (10 kDa molecular mass cutoff) (Millipore, Bedford, MA), and the concentrated protein was dialyzed overnight against lysis buffer without imidazole.

Activity and autoprocessing assays.

GPR activity was assayed on a mixture of SASP partially purified from B. megaterium spores by dry rupture in a dental amalgamator (Wig-L-Bug), followed by extraction of SASP with cold 1% acetic acid, dialysis against cold 1% acetic acid, and passage through a DEAE-cellulose column in 1% acetic acid as described previously (25). P41 activity was determined by incubating GPR (routinely 540 nM) with B. megaterium SASP (2.25 mg/ml) in 40 μl 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 5 mM CaCl2, 10% glycerol for 30 min at 37°C and monitoring SASP degradation by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) at low pH as described previously (24) (see Results). Activity against SASP was also assayed at higher concentrations of GPR variants to rule out low levels of residual activity. Autoprocessing of the GPR zymogen was carried out at a GPR concentration of 4 μM in 20 μl of 100 mM 2-[N-morpholino]ethanesulfonic acid (pH 6.2), 5 mM CaCl2, 10% glycerol, 50% DMSO (8). Samples were incubated at 30°C overnight, diluted in 2× sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-PAGE loading buffer (24), and analyzed by 8.5% SDS-PAGE to resolve P46 and P41 (6, 8, 21) (see Results). These conditions allowed for detection of ∼3% autoprocessing.

Analytical methods.

CD spectroscopy was done with a Jasco spectropolarimeter (J-715) at 20°C and a protein concentration of 10 μM in lysis buffer. Each spectrum was obtained by averaging three scans between 190 and 270 nm, and raw data were converted to molar ellipticity. Multiangle laser light scattering (MALLS) was detected with a TriStar MiniDAWN detector (Wyatt Technology, Santa Barbara, CA) by using the buffer system 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4)-5 mM CaCl2 and a Superdex 200 10/300 gel filtration column (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ).

RESULTS

Site-directed mutagenesis.

B. megaterium GPR was chosen for this mutagenesis study because the genes encoding both the P46 and P41 forms of this protein have been cloned (28), the purified proteins have proven amenable to in vitro studies (8), and the crystal structure of B. megaterium P46 has been solved (18). Amino acids in B. megaterium GPR were chosen for change if they fit three criteria. Each altered residue must (i) be a potential nucleophile (arginine, asparagine, aspartate, glutamate, glutamine, histidine, lysine, serine, threonine, or tyrosine), (ii) be conserved among 23 spore-forming bacteria for which there are gpr sequence data, and (iii) not be in regions of GPR whose removal does not eliminate GPR activity (Fig. 1). The latter criterion eliminated some conserved and potentially nucleophilic residues in the C-terminal one-third of the protein, as they can be removed from B. megaterium P41 without loss of activity, although the C-terminally truncated protein is unstable (15). Similarly, the first 21 amino acids of P46 can be removed without loss of P41 activity (11). Some residues that appeared to be good candidate nucleophiles were also changed even if they were not completely conserved, to protect against missing an important residue as the result of a genome sequencing error. Residues selected for variation were changed to amino acids that were expected to maintain the general shape and, where possible, the polarity of the original residue while not supporting nucleophilic attack. Multiple amino acid substitutions at a single position were employed in two cases. K223 was changed to alanine, glutamine, histidine, and methionine, while D127 was changed to alanine, glutamate, glutamine, and serine.

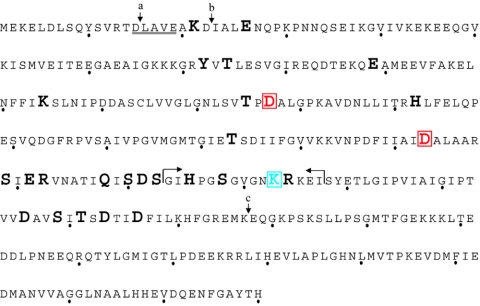

FIG. 1.

Residues changed in B. megaterium GPR. The amino acid sequence of B. megaterium P46 is shown, with every tenth position indicated by a dot below the corresponding amino acid given in the single-letter code. Altered amino acid positions are represented by large, bold letters, and the catalytically essential aspartic acid residues (D127 and D193) are highlighted and boxed in red. The putative inhibitory loop (residues 213 to 227) is surrounded by apposed arrows, and K223 is highlighted and boxed in blue. Arrow a indicates the peptide bond cleaved in the conversion of P46 to P41, and arrow b indicates the peptide bond cleaved when P41 undergoes a further autoprocessing reaction cleaving P41 to P39, which is still active against SASP. The underlined amino acids comprise GPR's autoprocessing recognition sequence. Arrow c indicates the site of trypsin cleavage that removes the C-terminal one-third of the protein while not affecting P41's activity against SASP.

The aspartate at position 127 was altered to multiple residues because the initial substitution, D127N, resulted in disruption of the variant's quaternary structure (Table 1). D127's importance in GPR's activity only became evident once D127A and D127E were generated, as these variants were well structured, unable to autoprocess as P46, and inactive against SASP as P41. Of particular note is the result that substituting a glutamic acid residue for the aspartate at position 127 resulted in a well-structured and inactive variant (Table 1), suggesting that this position is both essential for catalysis and exquisitely sensitive to structural perturbations.

TABLE 1.

Activity, autoprocessing, CD spectroscopy, and MALLS analysis on GPR variantsa

| GPR | Result for:

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P41

|

P46

|

|||||

| SASP assayb | Folded by CDc | MALLS (T:D:M)d | Autoprocessinge | Folded by CD | MALLS (T:D:M) | |

| Wild type | Active | Folded | 60:0:0 | Active | Folded | 90:0:0 |

| Inactive single variants | ||||||

| D127A | Inactive | Folded | 80:0:0 | Inactive | Folded | 100:0:0 |

| D127E | Inactive | Folded | 80:0:0 | Inactive | Folded | 100:0:0 |

| D127N | Inactive | Folded | 0:40:0 | Inactive | Folded | 90:0:0 |

| D127S | Inactive | Folded | 0:20:0 | Inactive | Folded | 90:0:0 |

| D193N | Inactive | Folded | 80:0:0 | Inactive | Folded | 90:0:0 |

| Active single variants | ||||||

| Group Ag | Active | NDf | ND | Active | Folded | ND |

| Group Bh | Active | Folded | ND | Active | Folded | ND |

| S199A | Active | Folded | 10:30:10 | Inactive | Folded | 80:0:0 |

| R202Q | Active | Folded | ND | Active | Folded | 90:0:0 |

| D246N | Partially active | Folded | Aggregatedi | Inactive | Folded | Aggregated |

| S249A | Partially active | Folded | Aggregated | Inactive | Folded | Aggregated |

| Deletion variants | ||||||

| Δ223 | Active | Folded | ND | Active | Folded | ND |

| Δ213-226 | Inactive | Misfolded | Aggregated | Inactive/inactive | Misfolded | Aggregated |

| Δ213-227 | Inactive | Misfolded | Aggregated | Inactive/inactive | Misfolded | Aggregated |

| Δ214-226 | Inactive | Misfolded | ND | Inactive/inactive | Misfolded | ND |

| Δ214-227 | Inactive | Misfolded | ND | Inactive/inactive | Misfolded | ND |

Assays of activity, autoprocessing, CD spectroscopy, and MALLS on wild-type P41 and P46 and all variants were done as described in Materials and Methods.

Active, no significant difference (± 20%) in activity relative to that of wild-type P41. Inactive, at least 80-fold less active than wild-type P41. Partially active, ≈50% activity relative to that of wild-type P41.

Folded, no significant difference between a variant's CD spectrum and that of the corresponding wild-type GPR (P41 or P46) (see Fig. 3). Misfolded, significant difference between a variant's CD spectrum and that of wild-type GPR.

Data are reported as ratios of the percent tetramer (T) to dimer (D) to monomer (M). These values may not add up to 100% because most proteins did not completely give well-defined populations of homogeneous particle size. (See Fig. 4.)

Active, generation of P41 after overnight incubation under autoprocessing conditions. Inactive, no P41 generated. Wild-type P46 typically autoprocesses to 50% completion overnight, and the sensitivity of this assay allows detection of ≈3% autoprocessing. Inactive/inactive, P46 variant was unable to autoprocess to P41 and was inactive against SASP as P46.

ND, not done.

D256N, E26Q, E89Q, H215Q, K21P, Q208E, S212A, S218A, T74D, T215V, and Y72F.

D153N, D211N, D253N, E201Q, H142Q, K223A, K223E, K223H, K223M, S210A, R224Q, T125N, and T173V.

Aggregated, MALLS analysis yielded only high-molecular-weight species with no detectable tetramer, dimer, or monomer.

Activity and autoprocessing of GPR variants.

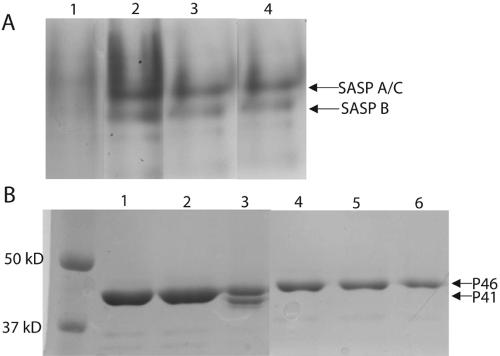

Multiple lines of evidence support the hypothesis that the processing of P46 to P41 is an autocatalytic event and that the same catalytic site mediates both autoprocessing and activity against SASP (1, 6, 7). It was, however, possible that a given variant could be active against SASP as P41 but be unable to autoprocess as P46, or vice versa. Consequently, variants were assayed for both the ability to autoprocess as P46 and for activity against SASP as P41 (Table 1; Fig. 2A and B). Note that SASP-A and SASP-C comigrate when run on a polyacrylamide gel at low pH (Fig. 2A). In Fig. 2B, more protein was loaded in lanes 1 and 2 than in lanes 3 to 6 to show that there was no autoprocessing in the absence of DMSO. Loading less protein revealed only P46 and no P41 (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

SASP activity and autoprocessing assays with GPR variants. (A) SASP activity assay. Following incubation of SASP with the indicated GPR as described in Materials and Methods, activity against SASP was assayed by subjecting the samples to PAGE at low pH; the disappearance of the SASP-A and SASP-C (which comigrate under these conditions) and SASP-B bands indicates activity. The GPR variants assayed in the various lanes are as follows: lane 1, wild-type P41; lane 2, D193N P41; lane 3, D127E P41; and lane 4, control with no P41. (B) Autoprocessing. Autoprocessing was carried out as described in Materials and Methods, and appearance of the lower-molecular-mass band (P41) by 8.5% SDS-PAGE indicates autoprocessing. The samples run in various lanes are as follows: lanes 1 to 3, wild-type P46, and lanes 4 to 6, D193N P46. Lanes 1 and 4 contain protein incubated overnight at 30°C in lysis buffer. Lanes 2 and 5 contain protein incubated overnight at 30°C in autoprocessing buffer with no DMSO. Lanes 3 and 6 contain protein incubated overnight at 30°C in autoprocessing buffer with 50% DMSO.

While all variants capable of autoprocessing as P46 were active against SASP as P41, there were some variants capable of cleaving SASP when expressed as P41 but unable to autoprocess (Table 1). Further analysis of these variants is beyond the scope of the current work, but it is likely that the amino acid substituted in each of these variants is located in a position important for the conformational changes necessary for autoprocessing and so may provide useful fodder for future study.

Of the 27 residues altered in this work, only the substitution of D127 and D193 resulted in a P41 that was inactive against SASP and a corresponding P46 that was unable to autoprocess to P41 (Table 1). These data provide further strong support for the hypothesis that GPR utilizes a single catalytic site to mediate both its autoprocessing and activity against SASP and, further, that D127 and D193 are GPR's only catalytically essential amino acids.

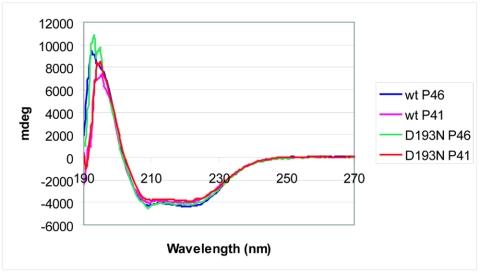

CD spectroscopy.

While the inactivity of variants resulting from the substitution of D127 and D193 suggested that these residues are essential for P46 autoprocessing and P41 activity against SASP, it was possible that these amino acid substitutions rendered the enzyme inactive by disrupting its three-dimensional structure rather than by replacing a catalytically essential residue. To address this issue, CD spectroscopy was carried out to determine the overall secondary structure of these inactive variants in comparison to that of wild-type GPR. CD spectra were also obtained for a number of active GPR variants to ensure that simply changing a noncatalytically essential residue did not alter the protein's CD spectrum (Table 1; Fig. 3). It was clear from these data that no amino acid substitution in either P46 or P41 noticeably disrupted the protein's overall secondary structure, although deletion of the putative inhibitory loop may have caused misfolding of secondary structural elements (Table 1). This analysis does not rule out local perturbations in structure or even large changes in regions of the protein lacking defined secondary structure. However, it does provide support for the hypothesis that altering D127 or D193 results in nonautoprocessing, inactive GPR variants because these are catalytically essential residues and not because they are important in folding of GPR's secondary structural elements.

FIG. 3.

CD spectra of wild-type and two inactive GPR variants, both as P46 and P41. Spectra were obtained as described in Materials and Methods.

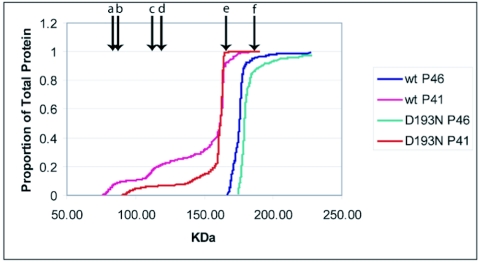

MALLS.

CD spectroscopy addressed the possibility that an amino acid substitution might effect folding of secondary structural elements of GPR, thereby resulting in an inactive variant. Another structural consideration important for GPR activity is its oligomeric state. Previous work has shown that P46 and P41 are active only as tetramers (12, 24), and so it is important to address the possibility that an amino acid substitution might cause a variant to be inactive against SASP and unable to autoprocess because of disruption of quaternary structure.

Use of gel filtration and particle size determination by MALLS showed that wild-type P46 was nearly 100% tetrameric, while P41 was largely tetrameric but also exhibited a significant percentage of lower-molecular-mass species (Table 1; Fig. 4). These results are consistent with previous data that have suggested P41 is less stable and more prone to dissociation than its zymogen precursor (8, 15). The data collected for the variants subjected to this analysis indicated that the oligomerization of GPR is sensitive to amino acid substitution, as at least one P41 variant (D127N) formed little tetramer while others (e.g., D127E and D193N) were more tetrameric than wild-type P41 (Table 1). However, the hypothesis that alteration of D127 and D193 each cause GPR inactivity by virtue of their being catalytically essential is supported by these data, since variants at both positions (D127E and D193N, both as P46 and P41) show at least as much tetramer as the corresponding wild-type enzyme (Table 1; Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

MALLS molecular mass determination data for wild-type and inactive variants. MALLS analyses were carried out as described in Materials and Methods. Labeled arrows indicate the molecular masses of the (a) P41 monomer, (b) P46 monomer, (c) P41 dimer, (d) P46 dimer, (e) P41 tetramer, and (f) P46 tetramer.

Three-dimensional analysis of D127, D193, and surrounding structures.

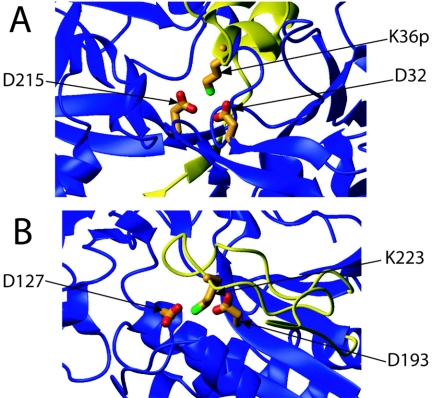

While site-directed mutagenesis identified D127 and D193 as the only two amino acids essential for GPR's autoprocessing and activity against SASP, these data needed to be checked against GPR's three-dimensional structure. D127 and D193 were, therefore, mapped onto the crystal structure of P46 and found to be in sufficiently close proximity to participate together in catalysis (Fig. 5B and Fig. 6). The argument for classification of GPR as an aspartic acid protease is further strengthened by the three-dimensional relationship of D127 and D193 with a nearby lysine (K223), since the relative orientations of these three residues are strongly reminiscent of many aspartic acid protease zymogen active sites, particularly that of pepsinogen (5). Figure 5 illustrates the relative orientations of the catalytic aspartic residues of pepsinogen (27) (Fig. 5A) and GPR (18) (Fig. 5B).

FIG. 5.

Three-dimensional comparison of catalytic residues of (A) porcine pepsinogen (propeptide is colored yellow) and (B) GPR (P46) with the putative inhibitory loop highlighted in yellow. Note the striking similarity in both amino acid identity and three-dimensional orientation of the one basic and two acidic residues in both enzymes.

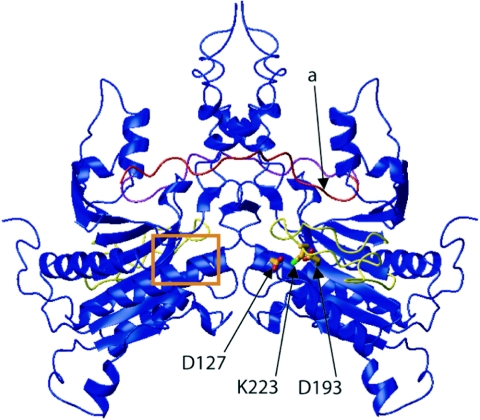

FIG. 6.

Crystallographic dimer representation of B. megaterium GPR. Monomer A is shown with its catalytic aspartic acid residues, K223, putative inhibitory loop (yellow), and propeptide (red). The autocleavage site for the conversion of P46 to P41 of monomer A is indicated by the arrow labeled “a.” Monomer B is shown, along with its propeptide (cyan), its putative inhibitory loop (yellow), and the position of its catalytic site (boxed in orange). Note that the dimer is symmetrical about the vertical axis after a rotation of 180°.

DISCUSSION

Previous work has determined that GPR is a sequence-specific tetrameric endoprotease but has failed to identify its catalytic residues. Two previous modeling studies have suggested very different residues as involved in GPR catalysis (9, 17). The first study utilized results of molecular docking simulations to suggest that three glutamic acid residues (E19, E26, and E202) take part in binding and hydrolysis of SASP (9). One of these (E19) had previously been ruled out as a residue essential for catalysis, as its removal by trypsin did not affect the activity of B. megaterium P41 (15). The current work shows that the P41 variants E26Q and E202Q also are fully active (Table 1).

Another group has suggested, based on analysis of three-dimensional homology, that aspartate residues D127 and D193 and lysine K223 contribute to substrate recognition by coordinating a divalent metal ion ostensibly provided by SASP (17). This hypothesis was consistent with the fact that D127, D193, and K223 have a similar three-dimensional relationship with the surrounding protein fold and with one another, compared with the two acidic residues and a histidine responsible for metal-mediated substrate recognition and cleavage by bacterial hydrogenase maturation protease (HybD) (17). There are, however, at least four lines of evidence inconsistent with this hypothesis. There is no evidence that SASP binds any metal (P. Setlow, unpublished data), and GPR's activity is not inhibited by metal ion chelators nor have metal ions been found associated with either P46 or P41, other than the Ca2+ used to stabilize the protein (15). Finally, altering K223 to multiple residues (alanine, glutamate, histidine, and methionine) or simply deleting it had no effect on GPR's activity against SASP or autoprocessing (Table 1).

While GPR is an aspartic acid protease by virtue of its two catalytically essential aspartates, at least four characteristics set it apart from other members of this protease class. First, GPR's primary amino acid sequence is not homologous to any known protein. Second, three-dimensional homology modeling suggests that GPR has a fold similar to HybD (17) but not to any aspartic acid protease for which there is an atomic resolution structure. Third, GPR is a homotetramer with each subunit containing a full catalytic site. This is in contrast to other aspartic acid proteases, most of which are either homodimers, where each monomer provides one catalytic aspartate, or monomers containing a single active site. Finally, and perhaps most interestingly, GPR appears to differ significantly from all known proteases in the way it maintains zymogen inactivity. While there are multiple mechanisms utilized by proteases to maintain zymogen inactivity (reviewed in reference 11), P46 appears to make use of a novel variation on at least one, and possibly two, common themes.

Many proteases, including some aspartic acid proteases, maintain zymogen inactivity by placing their propeptide over the future active site, thereby sterically blocking substrate access and rendering the protease inactive (e.g., pepsinogen). Another common method of maintaining zymogen inactivity is to hold the active-site residues in a conformation incompatible with enzymatic activity while leaving the active site accessible (e.g., proplasmepsin [10]). The crystal structure of P46 suggests that GPR maintains inactivity by at least one, and possibly both, of these strategies. Figures 1 and 5 illustrate the relative positions of GPR's propeptide, catalytic aspartic acid residues, and the putative inhibitory loop in the primary amino acid sequence and in three-dimensional space, respectively. Consistent with previous propeptide deletion analysis (16), the crystal structure of P46 suggests that the majority of the propeptide does not interact with the rest of the protein in general or with the active site in particular. Rather, examination of the P46 structure suggests that a loop composed of residues 213 to 227 physically blocks access to GPR's catalytic aspartic acid residues. Further, K223 appears to interact closely with both putative catalytic aspartic acid residues in a manner reminiscent of pepsinogen's structure (5), and measurement of the distance between Cδ of D127 and that of D193 (4.4 Å) indicates that they may be held in an inactive conformation. However, this determination is complicated by the low resolution of the P46 crystal structure (crystals diffracted to 3.0 Å [18]). Finally, the putative inhibitory loop of GPR has a pI significantly higher than that of the protein as a whole (10.0 and 4.9, respectively) (20). These latter values are in good agreement with that of pepsinogen's propeptide compared to that of pepsinogen as a whole (pI values for the propeptide and whole protein of 10.3 and 4.2, respectively).

Given these structural considerations and similarities between GPR's putative inhibitory loop and pepsinogen's propeptide, we hypothesize that the loop formed by residues 213 to 227 functions to maintain GPR zymogen inactivity by steric occlusion. We further hypothesize that the conditions that induce P46 to autoprocess to P41 cause a conformational change such that this loop no longer fully inhibits the catalytic residues, allowing the propeptide cleavage site to swing down into the active site and thereby mediating self-cleavage. An examination of the P46 structure (Fig. 5) lends support to this hypothesis as follows: (i) the putative inhibitory loop does not contain any secondary structural elements, and so it could change conformation without altering GPR's CD spectrum; (ii) this loop's ends are in close proximity to each other, suggesting that the loop could swing away from the surface of the protein, exposing GPR's active site without disrupting structural elements in close proximity along the polypeptide backbone; and (iii) D127 and D193 are ∼15 Å from the autoprocessing cleavage site, putting them within striking distance to mediate autocleavage, as this distance is comparable to the analogous interresidue distances of pepsinogen (∼20 Å). The alternative hypothesis that one monomer's propeptide is cleaved by a neighboring monomer is unlikely, given the large distance between one monomer's active site and another monomer's propeptide cleavage site. Specifically, the active site of any monomer relative to another monomer's propeptide cleavage site is (i) spatially separated (30 to 45 Å, depending on the monomer pair examined) and (ii) structurally restrained from traversing this large distance separating them (Fig. 6). Additionally, previous work is consistent with the N terminus of GPR being able to interact with its active site, since incubation of P41 under autoprocessing conditions results in a further autocatalytic cleavage reaction that removes seven additional amino acids, producing a smaller species termed P39 (7) (Fig. 1).

An inhibitory loop such as the one hypothesized here is apparently unprecedented among aspartic acid proteases in that it is not part of the zymogen's propeptide but rather remains integral to the enzyme's polypeptide backbone following autoprocessing. If the loop were shown to maintain P46 inactivity, it would set GPR apart from all known aspartic acid proteases and, indeed, perhaps even from all known proteases in general. To investigate this possibility in more detail, variants of this putative inhibitory loop were generated as both P46 and P41 and assayed for the ability to autoprocess and for activity against SASP. However, none of these variants were found to autoprocess or to be active against SASP, most likely due to misfolding as judged by CD and MALLS (Table 1).

GPR's catalytic residues have now been identified as D127 and D193. Questions still remain, however, regarding accessory active site amino acids, residues important for autoprocessing but not activity, and the mechanistic details of GPR-mediated proteolysis of SASP and P46 autoprocessing. A full understanding of these issues will likely need to await atomic-resolution structure determination of P41 in combination with biochemical studies.

Acknowledgments

We thank Scott Robson and Glenn King for their assistance with MALLS and Dan Desrosiers and Zheng-Yu Peng for their assistance with CD. We also thank Irina Bagyan for cloning B. megaterium gpr, Michael Smith for his assistance in the early aspects of this work, and Jeff Hoch for comments on the manuscript.

This work was supported by a grant from the Army Research Office.

REFERENCES

- 1.Carrillo-Martinez, Y., and P. Setlow. 1994. Properties of Bacillus subtilis small, acid-soluble spore proteins with changes in the sequence recognized by their specific protease. J. Bacteriol. 176:5357-5363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fujinaga, M., M. M. Cherney, H. Oyama, K. Oda, and M. N. James. 2004. The molecular structure and catalytic mechanism of a novel carboxyl peptidase from Scytalidium lignicolum. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101:3364-3369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gattiker, A., E. Gasteiger, and A. Bairoch. 2002. ScanProsite: a reference implementation of a PROSITE scanning tool. Appl. Bioinformatics 1:107-108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hackett, R. H., and P. Setlow. 1988. Properties of spores of Bacillus subtilis strains which lack the major small, acid-soluble protein. J. Bacteriol. 170:1403-1404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hartsuck, J. A., G. Koelsch, and S. J. Remington. 1992. The high-resolution crystal structure of porcine pepsinogen. Proteins 13:1-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Illades-Aguiar, B., and P. Setlow. 1994. Autoprocessing of the protease that degrades small, acid-soluble proteins of spores of Bacillus species is triggered by low pH, dehydration, and dipicolinic acid. J. Bacteriol. 176:7032-7037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Illades-Aguiar, B., and P. Setlow. 1994. Studies of the processing of the protease which initiates degradation of small, acid-soluble proteins during germination of spores of Bacillus species. J. Bacteriol. 176:2788-2795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Illades-Aguiar, B., and P. Setlow. 1994. The zymogen of the protease that degrades small, acid-soluble proteins of spores of Bacillus species can rapidly autoprocess to the active enzyme in vitro. J. Bacteriol. 176:5571-5573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jedrzejas, M. J. 2002. Three-dimensional structure and molecular mechanism of novel enzymes of spore-forming bacteria. Med. Sci. Monit. 8:RA183-RA190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khazanovich-Bernstein, N., and M. N. James. 1999. Novel ways to prevent proteolysis—prophytepsin and proplasmepsin II. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 9:684-689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lazure, C. 2002. The peptidase zymogen proregions: nature's way of preventing undesired activation and proteolysis. Curr. Pharm. Des. 8:511-531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Loshon, C. A., and P. Setlow. 1982. Bacillus megaterium spore protease: purification, radioimmunoassay, and analysis of antigen level and localization during growth, sporulation, and spore germination. J. Bacteriol. 150:303-311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Loshon, C. A., B. M. Swerdlow, and P. Setlow. 1982. Bacillus megaterium spore protease. Synthesis and processing of precursor forms during sporulation and germination. J. Biol. Chem. 257:10838-10845. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mason, J. M., and P. Setlow. 1986. Essential role of small, acid-soluble spore proteins in resistance of Bacillus subtilis spores to UV light. J. Bacteriol. 167:174-178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nessi, C., M. J. Jedrzejas, and P. Setlow. 1998. Structure and mechanism of action of the protease that degrades small, acid-soluble spore proteins during germination of spores of Bacillus species. J. Bacteriol. 180:5077-5084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pedersen, L. B., C. Nessi, and P. Setlow. 1997. Most of the propeptide is dispensable for stability and autoprocessing of the zymogen of the germination protease of spores of Bacillus species. J. Bacteriol. 179:1824-1827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pei, J., and N. V. Grishin. 2002. Breaking the singleton of germination protease. Protein Sci. 11:691-697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ponnuraj, K., S. Rowland, C. Nessi, P. Setlow, and M. J. Jedrzejas. 2000. Crystal structure of a novel germination protease from spores of Bacillus megaterium: structural arrangement and zymogen activation. J. Mol. Biol. 300:1-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Powell, J. F. 1953. Isolation of dipicolinic acid (pyridine-2:6-dicarboxylic acid) from spores of Bacillus megatherium. Biochem. J. 54:210-211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Putnam, C. 1999. Protein calculator. http://www.scripps.edu/∼cdputnam/protcalc.html.

- 21.Sanchez-Salas, J. L., and P. Setlow. 1993. Proteolytic processing of the protease which initiates degradation of small, acid-soluble proteins during germination of Bacillus subtilis spores. J. Bacteriol. 175:2568-2577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Setlow, B., and P. Setlow. 1993. Binding of small, acid-soluble spore proteins to DNA plays a significant role in the resistance of Bacillus subtilis spores to hydrogen peroxide. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 59:3418-3423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Setlow, P. 1992. I will survive: protecting and repairing spore DNA. J. Bacteriol. 174:2737-2741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Setlow, P. 1976. Purification and properties of a specific proteolytic enzyme present in spores of Bacillus megaterium. J. Biol. Chem. 251:7853-7862. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Setlow, P. 1975. Purification and properties of some unique low molecular weight basic proteins degraded during germination of Bacillus megaterium spores. J. Biol. Chem. 250:8168-8173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Setlow, P. 1988. Small, acid-soluble spore proteins of Bacillus species: structure, synthesis, genetics, function, and degradation. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 42:319-338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sielecki, A. R., M. Fujinaga, R. J. Read, and M. N. James. 1991. Refined structure of porcine pepsinogen at 1.8 A resolution. J. Mol. Biol. 219:671-692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sussman, M. D., and P. Setlow. 1991. Cloning, nucleotide sequence, and regulation of the Bacillus subtilis gpr gene, which codes for the protease that initiates degradation of small, acid-soluble proteins during spore germination. J. Bacteriol. 173:291-300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang, W., and B. A. Malcolm. 1999. Two-stage PCR protocol allowing introduction of multiple mutations, deletions and insertions using QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis. BioTechniques 26:680-682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]