Abstract

The anticoccidial agents clopidol is widely used in livestock production to prevent coccidiosis; however, the residues that remain in edible tissues pose a risk to human consumers. This study investigated the residue depletion and metabolism of orally administered radiolabeled [3H]-clopidol (25 mg/kg body weight) in the liver, muscle, kidney, and fat. The analytical methods employed for all tissues were subjected to rigorous validation to ensure their selectivity, linearity (r² ≥ 0.999), system suitability (0.4%), accuracy (89.5–102.5%), and precision (> 5.2%). The validated method using radio-HPLC and liquid scintillation counting indicated that the highest concentrations of clopidol residues were observed 6 h post-administration in the liver (28.81 ± 2.41 mg/kg), muscle (14.31 ± 0.77 mg/kg), kidney (29.22 ± 2.3 mg/kg), and fat (7.26 ± 0.70 mg/kg). Most clopidol levels subsequently decreased and were below the limit of quantification after 3 d in all tissues. The metabolite 3,5-dichloro-2-hydroxymethyl-6-methylpyridin-4-ol was detected in all tissues 6 h after administration using LC–MS (liver: 1.17 ± 0.29 mg/kg, muscle: 0.73 ± 0.15 mg/kg, kidney: 2.76 ± 1.03 mg/kg, and fat: 0.5 ± 0.11 mg/kg). A health risk assessment indicated that the residual concentrations in edible tissues were safe for consumption by all ages and sexes. This study provides a useful framework for monitoring clopidol residues, their depletion, and metabolism in broiler chickens and the by-products.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-025-19864-0.

Keywords: Clopidol, Depletion, Metabolite, Residue, Risk assessment

Subject terms: Small molecules, Chemical biology

Introduction

Livestock production has become an important source of nutrition. Poultry meat is a high-quality protein source rich in amino acids, vitamins, and minerals1,2. The poultry industry has greatly expanded to meet the increasing demand3,4. Coccidiosis, caused by protozoa of the genera Eimeria and Isospora, is one of the most prevalent poultry diseases and an important challenge in the industry. It negatively affects meat quality and yield, increases the risk of secondary infections, and causes economic losses exceeding $15 billion5–7.

Numerous anticoccidial agents have been developed8,9 to improve productivity/meet market demands and reduce production losses owing to morbidity and mortality in broilers10. However, the hazards of drug residues in edible tissues have prompted screening and monitoring of meat and processed products11–14, residue dissipation studies of target drugs15,16, and analysis of metabolites in numerous medicines17–19. Consequently, stringent regulations on antibiotic usage are essential to mitigate chronic exposure and the associated risks of adverse health effects20–24.

Awareness of the risks associated with antibiotic residues in meats has increased over the past decades25–27 and many countries, including those in the European Union, have implemented stringent regulations on veterinary pharmaceuticals guided by scientific evidence, established maximum residue limits (MRLs), and acceptable daily intake (ADI) levels25. Various risk assessments have been conducted leveraging the advances in molecular analytical technologies for detecting the dissipation of veterinary drug residues from livestock and processed products26,27. In residue dissipation and metabolite formation analyses, the use of radioisotopes enables the precise tracking of metabolites for accurate quantitative analysis28–30.

Among various veterinary drugs, clopidol, a widely used coccidiostat, is administered prophylactically via incorporation into feed31. According to a report by Global Clopidol Market Growth (2024)32, clopidol is anticipated to experience substantial growth in demand owing to its capacity to enhance feed efficiency and mitigate disease-related losses. Previous studies have demonstrated that clopidol exhibits low acute toxicity and is rapidly absorbed and excreted in the urine following oral administration in rats, broilers and rabbits33–38. Residue distribution analyses have shown that the highest concentrations of clopidol are typically detected in the kidney and liver tissues. Clopidol is approved in South Korea and the United State. In South Korea, it is regulated with MRLs ranging from 0.02 to 20 mg/kg for livestock, including broilers. However, international regulatory standards have not yet been established, largely due to the absence of radioisotope-based studies that can accurately quantify the levels of the parent compound, its metabolites and non-extractable residues, and propose metabolic pathways. Accordingly, comprehensive dissipation studies employing radioactive isotope are essential to ensure the safe and effective management of clopidol use in poultry production.

This study presents the first comprehensive investigation of the time-dependent depletion, metabolism, and metabolites of clopidol in broilers utilizing radiolabeled [3H]-clopidol with exceptional selectivity. Considering the food-associated health risks linked to both acute and chronic exposure to antimicrobial residues24,40, we performed a health risk assessment of clopidol accumulation in edible tissues based on Korean consumption statistics.

Results and discussion

Validation of analytical method

The precise quantification of residual concentrations in various matrices is critical for evaluating risks and establishing regulations consistent with empirical standards, such as internationally recognized guidelines41–44. These guidelines prescribe key validation parameters such as specificity, limit of detection (LOD), limit of quantification (LOQ), system suitability, linearity, accuracy, and precision to ensure the reliability of the analytical results. Data that met the validation criteria were used to determine the MRL, considering the potential risks to human health.

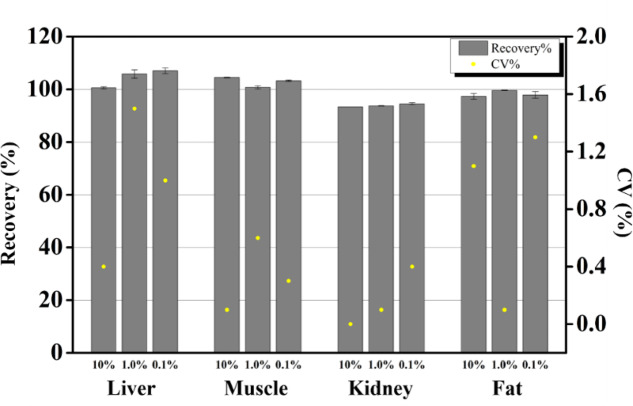

The optimal analytical conditions and sample pretreatment methods were developed and validated for various tissue matrices. Specificity assessments confirmed the absence of interfering substances, ensuring selective identification. The linearity of detection responses was verified across at least five concentrations for all tissue samples (r2 ≥ 0.999), and system suitability with repeated injection was within the coefficient of variation (CV) of 0.4%. The LOQ values of all tissue LSC and Radio-HPLC analyses ranged from 0.95 to 13.5 μg/kg and 14.26 to 285.23 μg/kg, respectively (Supplementary Table S3). The accuracy and precision were evaluated using recovery experiments and CV values. The recovery rates of clopidol across the tissue matrices treated with varying concentrations ranged from 89.5 to 102.5%, with a maximum CV of 5.2% (Fig. 1). During pretreatment, a combination of PSA, C18E, and GCB provided high recovery rates for most matrices. However, in fat samples, the inclusion of C18E and GCB led to reduced recovery, while the use of PSA alone delivered optimal performance. This discrepancy could be due to the partition factor between the sorbent and extraction solvent, acetonitrile, as Mercedes Castillo et al. (2011)45 found that more non-polar compounds in fat samples resulted in low recoveries in the C18 sorbent. Therefore, both the non-polar clopidol and lipophilic interferents in the fat sample were strongly adsorbed on the C18 or GCB sorbents, and the interferents seemed to affect the extraction efficiency of clopidol in the acetonitrile extraction system12. In the stability test, the clopidol remained stable (111.3 ± 0.3–118.9 ± 3.5) for 14 days under frozen storage of below − 20 °C in four tissues (liver, kidney, muscle, and fat). All samples were analyzed within that period (Supplementary Table S4).

Fig. 1.

Results of recovery (%) and coefficient of variation (CV, %) in extracts from each tissue with 10, 1.0, and 0.1% applied doses.

This study provides a robust framework for detecting clopidol in the kidney, muscle, liver, and fat with high reliability and compliance with international validation standards, providing essential data for risk assessment and industry management.

Detection and distribution of clopidol

To determine the persistence and distribution of clopidol administered orally to broilers, various tissue samples were collected at 6 h, 1, 3, 5, and 10 d post-dosing with radioisotopes and analyzed using validated assays.

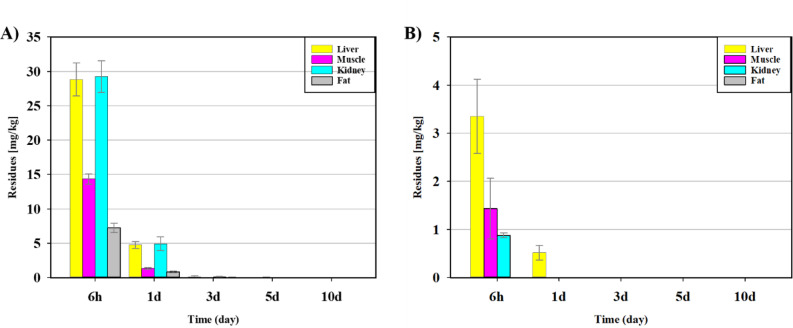

Clopidol residues in tissue samples were predominantly detected in the liver and kidneys, where the highest concentrations were detected at the beginning of the study (28.81 and 29.22 mg/kg, respectively), followed by muscle (14.33 mg/kg) and fat (7.256 mg/kg). The residue concentrations in the liver, kidney, muscle, and fat were much higher 1 d after dose administration (4.76, 4.93, 1.33, and 0.85 mg/kg, respectively) than 3 d after (0.15, 0.15, < LOQ, and 0.09 mg/kg, respectively). From day 3 onward, clopidol residues were below the LOQ in all tissues (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 2.

Concentrations of residues in liver, muscle, kidney, and fat and non-extractable residues (NERs) at 6 h, 1 d, 3 d, 5 d, and 10 d after oral administration. (A) Tissues, (B) NERs.

Major drug-excreting organs, such as the liver and kidneys, are susceptible to residues owing to their biological functions; therefore, most studies have focused on the roles of the liver and kidney in drug accumulation and depletion46. In our study, following oral administration, clopidol initially accumulated in the liver and kidney compared to other tissues, and was dramatically depleted after 1 d. These results are similar to those in a rabbit study using [14C]-clopidol, which showed more rapid absorption and elimination after oral dosing in the liver and kidney than in the muscle tissue37. Therefore, clopidol accumulates mainly in the liver and kidneys and is rapidly eliminated, consistent with the behavior of other veterinary drugs.

The NERs in the liver, muscle, and kidney were much higher at 6 h after the dose (3.35, 1.43, and 0.88 mg/kg, respectively) than at 1 d later (0.52 mg/kg, < LOQ, and < LOQ, respectively); no NERs were detected in fat (< LOQ). On day 3, the NERs remained below the LOQ in all tissues (Fig. 2B). NERs remained higher in the liver than in other tissues, retaining up to a maximum 13.4% of the total administered concentration, which decreased significantly over time. NERs pose a risk to environmental and human health47 because they allow antibiotics (and pesticides) to persist and bind to other biological materials48. This is a critical consideration when interpreting the results of residue depletion studies and establishing regulatory standards. Nevertheless, it is a highly intricate and challenging endeavor to characterize NERs because robust extraction methodologies or enzymatic preparations can destroy or form artifacts of residues that are strongly adsorbed in tissues49.Further work is needed to characterize the nature of NERs.

Metabolism of clopidol

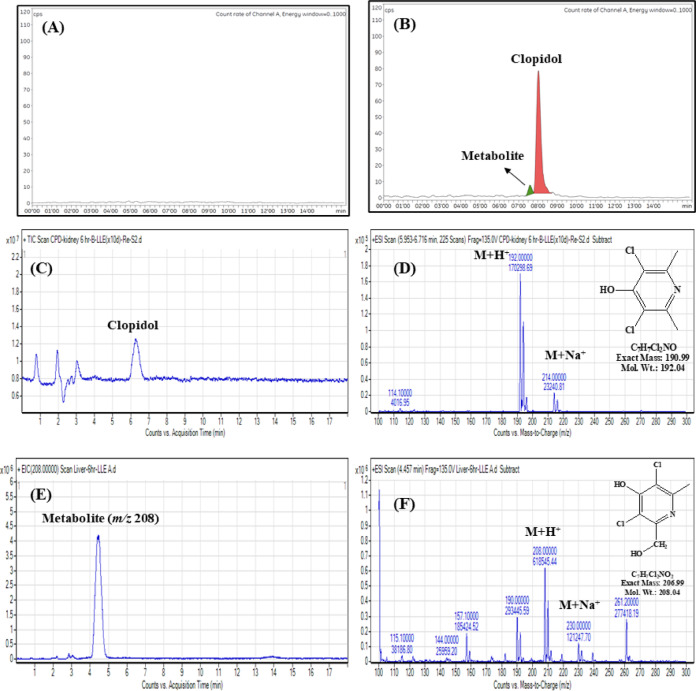

At 6 h post-dose, two compounds including the major compound detected at the same retention time as clopidol were found by radio-HPLC in extracts of all tissue samples; the metabolite was found to have the highest concentration in the kidney (2.76 mg/kg), followed by the liver (1.17 mg/kg), muscle (0.73 mg/kg), and fat (0.5 mg/kg). No metabolites were found in any tissue 1 d after dosing (Fig. 3A and B).

Fig. 3.

Representative chromatograms and mass spectra for clopidol and metabolites. (A) Blank control extract for Radio-HPLC, (B) Kidney extract for Radio-HPLC, (C, D) Clopidol in kidney extract for LC–MS, (E, F) Metabolite in kidney extract for LC–MS.

After dosing, clopidol and its metabolites were detected in the tissues using LC–MS. The ESI–MS mass spectra for the sample and authentic standard of clopidol showed the same patterns: m/z 208 detected as a protonated molecular ion (M + H+), m/z 230 as a sodium adduct molecular ion (M + Na+), and a natural abundance of the chlorine isotope (35Cl:37Cl, 3:1) (Fig. 3C and D). For the metabolite, the MS spectra at m/z 208.00 indicated the protonated molecule ion [M + H]+, m/z 230.00 the sodium adduct molecular ion [M + Na]+, and 190.10 the cleavage of hydroxyl [M-OH]+ (Fig. 3E and F). The metabolite that was potentially detected in tissue samples using the detection method established in this study was inferred to be 3,5-dichloro-2-hydroxymethyl-6-methylpyridin-4-ol (exact mass: 207 g/mol), a hydroxylated metabolite, based on the above MS analysis and a previous study analyzing the formation of clopidol metabolites in rabbits37, which identified metabolites based on hydroxyl bonds. The addition of hydroxyl groups (oxidation) to xenobiotics is common for promoting detoxification in living organisms50–52. However, metabolites formed by other reactions such as glucuronide bonding and acetylation, which also participate in the elimination of xenobiotics from the body, were not found in this study. These metabolic processes may simply be too difficult to detect because of their rapid occurrence and subsequent metabolite excretion or accumulation in insufficient amounts53–55.

Health risk assessment

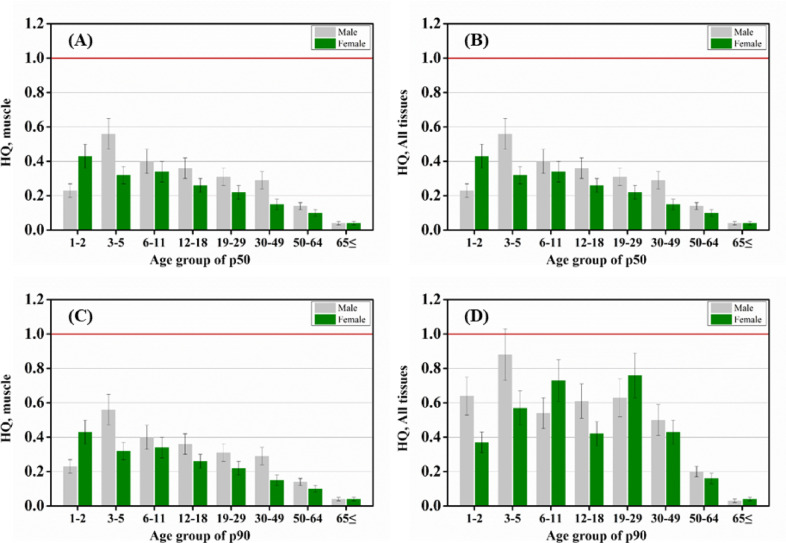

We assessed the daily intake and HQ of clopidol residues indirectly exposed to humans through broiler chickens. The average EDI values in the muscle and all tissues were similar because the daily intake of chicken byproducts was quite low. The EDI of 3–5-y-old males was the highest (22.2 μg/kg), and decreased with increasing age in both males and females of the p50 group. The EDI of the p50 group at all ages showed that the intake of chicken meat/kg body weight was higher in toddlers likely because of their lower body weight compared to adults (Fig. 4 and Table 1)56. The lowest intake of clopidol from chicken consumption was observed in adults aged ≥ 65 years, consistent with previous findings57. As expected, the EDI in the p90 group was almost double or triple as high at all ages compared with that in the p50 group. This difference is likely associated with the higher EDI of females at 6–11 and 19–29 years than those of males in the p90 group (Fig. 4 and Table 1).

Fig. 4.

Estimated daily intake of clopidol for average- (p50; A, B) and high-consumption groups (p90; C, D) of Korean males and females across ages.

Table 1.

Estimated daily intake of muscle (meat) and all tissues (muscle, kidney, liver, and fat) for the average (p50) and high (p90) intake groups by sex and age.

| p50 group | EDI, muscle | EDI, all tissues | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ages | Males | Females | Males | Females |

| 1-2y | 9.22 ± 1.55 | 17.08 ± 2.88 | 9.22 ± 1.55 | 17.08 ± 2.88 |

| 3-5y | 22.25 ± 3.74 | 12.78 ± 2.15 | 22.25 ± 3.74 | 12.78 ± 2.15 |

| 6-11y | 15.87 ± 2.67 | 13.51 ± 2.27 | 15.91 ± 2.69 | 13.51 ± 2.27 |

| 12-18y | 14.55 ± 2.45 | 10.22 ± 1.72 | 14.55 ± 2.45 | 10.22 ± 1.72 |

| 19-29y | 12.53 ± 2.11 | 8.72 ± 1.47 | 12.55 ± 2.12 | 8.72 ± 1.47 |

| 30-49y | 11.67 ± 1.97 | 6.00 ± 1.01 | 11.69 ± 1.98 | 6.03 ± 1.03 |

| 50-64y | 5.60 ± 0.94 | 3.82 ± 0.64 | 5.66 ± 0.97 | 3.82 ± 0.64 |

| 65y ≤ | 1.68 ± 0.28 | 1.43 ± 0.24 | 1.73 ± 0.31 | 1.45 ± 0.25 |

| p90 group | EDI, muscle | EDI, all tissues | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ages | Males | Females | Males | Females |

| 1-2y | 25.65 ± 4.32 | 14.98 ± 2.52 | 25.65 ± 4.32 | 14.98 ± 2.52 |

| 3-5y | 35.07 ± 5.90 | 22.81 ± 3.84 | 35.07 ± 5.90 | 22.81 ± 3.84 |

| 6-11y | 21.51 ± 3.62 | 29.09 ± 4.90 | 21.55 ± 3.64 | 29.09 ± 4.90 |

| 12-18y | 24.21 ± 4.08 | 16.98 ± 2.86 | 24.21 ± 4.08 | 16.98 ± 2.86 |

| 19-29y | 25.10 ± 4.23 | 30.42 ± 5.12 | 25.12 ± 4.23 | 30.42 ± 5.12 |

| 30-49y | 20.13 ± 3.39 | 17.17 ± 2.89 | 20.15 ± 3.4 | 17.20 ± 2.91 |

| 50-64y | 8.09 ± 1.36 | 6.23 ± 1.05 | 8.14 ± 1.39 | 6.23 ± 1.05 |

| 65y ≤ | 1.16 ± 0.20 | 1.52 ± 0.26 | 1.21 ± 0.22 | 1.55 ± 0.27 |

We assessed the HQ of all tissues to determine the health risks associated with clopidol (HQs < 1 indicate no adverse health effects and the amount consumed is below the ADI; HQs > 1 indicate consumption above the ADI and potential for health risks). All HQ values observed for chicken muscle and tissues were < 1 for all consumption groups, sexes, and ages. This suggests that the amount of clopidol consumed through chicken meat is not a threat to health58. However, this result should be carefully considered because the error bar is above 1, despite the safe HQ value in the high-consumption group of 3–5-y-old boys (Fig. 5 and Table 2).

Fig. 5.

Hazard quotient of clopidol for average- (p50; A, B) and high-consumption groups (p90; C, D) of Korean males and females across ages.

Table 2.

Hazard quotients of muscle (meat) and all tissues (muscle, kidney, liver, and fat) for average (p50) and high (p90) intake groups by sex and age.

| p50 group | HQ, muscle | HQ, all tissues | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ages | Males | Females | Males | Females |

| 1-2y | 0.23 ± 0.04 | 0.43 ± 0.07 | 0.23 ± 0.04 | 0.43 ± 0.07 |

| 3-5y | 0.56 ± 0.09 | 0.32 ± 0.05 | 0.56 ± 0.09 | 0.32 ± 0.05 |

| 6-11y | 0.40 ± 0.07 | 0.34 ± 0.06 | 0.40 ± 0.07 | 0.34 ± 0.06 |

| 12-18y | 0.36 ± 0.06 | 0.26 ± 0.04 | 0.36 ± 0.06 | 0.26 ± 0.04 |

| 19-29y | 0.31 ± 0.05 | 0.22 ± 0.04 | 0.31 ± 0.05 | 0.22 ± 0.04 |

| 30-49y | 0.29 ± 0.05 | 0.15 ± 0.03 | 0.29 ± 0.05 | 0.15 ± 0.03 |

| 50-64y | 0.14 ± 0.02 | 0.10 ± 0.02 | 0.14 ± 0.02 | 0.10 ± 0.02 |

| 65y ≤ | 0.04 ± 0.01 | 0.04 ± 0.01 | 0.04 ± 0.01 | 0.04 ± 0.01 |

| p90 group | HQ, muscle | HQ, all tissues | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ages | Males | Females | Males | Females |

| 1-2y | 0.64 ± 0.11 | 0.37 ± 0.06 | 0.64 ± 0.11 | 0.37 ± 0.06 |

| 3-5y | 0.88 ± 0.15 | 0.57 ± 0.10 | 0.88 ± 0.15 | 0.57 ± 0.10 |

| 6-11y | 0.54 ± 0.09 | 0.73 ± 0.12 | 0.54 ± 0.09 | 0.73 ± 0.12 |

| 12-18y | 0.61 ± 0.10 | 0.42 ± 0.07 | 0.61 ± 0.10 | 0.42 ± 0.07 |

| 19-29y | 0.63 ± 0.11 | 0.76 ± 0.13 | 0.63 ± 0.11 | 0.76 ± 0.13 |

| 30-49y | 0.50 ± 0.08 | 0.43 ± 0.07 | 0.50 ± 0.09 | 0.43 ± 0.07 |

| 50-64y | 0.20 ± 0.03 | 0.16 ± 0.03 | 0.20 ± 0.03 | 0.16 ± 0.03 |

| 65y ≤ | 0.03 ± 0.01 | 0.04 ± 0.01 | 0.03 ± 0.01 | 0.04 ± 0.01 |

Conclusions

This study evaluated the residue depletion patterns and metabolic trends associated with clopidol in broilers, and assessed the potential health risks associated with its indirect intake across different age groups and sexes in Korea.

Clopidol was administered orally to broilers at 25 mg/kg and the liver, kidneys, fat, and muscles were analyzed using LSC and radio-HPLC at 6 h, 1, 3, 5, and 10 d later. Both clopidol and its metabolite were detected in all the tissue extracts, with the parent compound identified as the major form. Clopidol was mostly concentrated to the liver and kidney rather than in other tissues and was rapidly depleted in all tissues after 5 d, indicating that it was excreted in urine or faeces rapidly following oral administration. The metabolite hydroxylated clopidol (3,5-dichloro-2-hydroxymethyl-6-methylpyridin-4-ol) was detected using LC–MS at concentrations of 0.5–2.76 mg/kg during the study period. Consistent with the dissipation pattern of the parent compound, the metabolite exhibited a rapid decline, suggesting that it persists in the body only for a short duration. Nevertheless, further investigations, including toxicological evaluation and pharmacokinetics studies of the detected metabolite, are warranted to comprehensively assess its potential impacts on animal health and food safety.

The health risk assessment using statistical data for Korea indicated that the muscles of broilers were predominantly exposed to residual clopidol, a consequence of its high intake. However, the concentration was considered safe for all age groups and sexes (HQ value of < 1).

The findings presented herein are believed to be useful in supporting or establishing regulatory standards for the veterinary use of clopidol.

Materials and methods

Chemicals and reagents

Analytical-grade clopidol (99.88% purity) was purchased from Ningboshi Chingxing Bio-Technology (Ningbo, China). [3H]-Clopidol [specific activity, 4.8 Ci/mmol (178 GBq/mmol)] was synthesized by RC Tritec (Teufen, Switzerland), and its absolute purity was confirmed using radioactivity-high-performance liquid chromatography (Radio-HPLC, RAMONA Star, Agilent 1260 infinity, Elysia Raytest, Straubenhardt, Germany). Labeled clopidol was identified by comparing its retention time with that of non-radiolabeled clopidol dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) using HPLC-UVD analysis (Fig. S1). HPLC-grade acetonitrile and water were obtained from Burdick & Jackson (Morristown, NJ, USA). Analytical grade nitromethane, trifluoroacetic acid, carboxymethyl cellulose sodium salt, and cellulose were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Merck KgaA, Darmstadt, Germany). Analytical grade dimethyl sulfoxide was provided by SAMCHUN Chemicals (Seoul, Korea). We used Insta-Gel Plus, Ultima-Flo AP, and MonoPhase S (Tri-Carb® 2910TR, PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA) for liquid scintillation counting (LSC) and Soluene-350 (PerkinElmer) as a tissue solubilizer. QuEchER dSPE kits were obtained from Phenomenex (Torrance, CA, USA). Sterilized water was prepared using a tertiary distillation apparatus (MILLI-Q, Burlington, MA, USA).

Test system and conditions

This study was approved and conducted in accordance with the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (protocol number: GIACUC-R-001 for broilers) of the Korea Institute of Toxicology, Republic of Korea and the ARRIVE (Animal Research: Reporting of In Vivo Experiments) guideline. The exposure experiments were conducted under controlled conditions at the Environmental Safety Assessment Center, Korea Institute of Toxicology. The Arbor Acres broiler breed (21 d old, average body weight: 1.11 ± 0.08 kg, range: 1.01–1.26 kg) was used in this study. Six test cages were prepared with four broilers per cage (1200 (W) × 600 (D) × 400 (H) mm). They were provided water and food (~ 700 g; IMMUNITY CHOI, ECOFAM, Jincheon, Korea) once daily during the acclimatization (7 d) and test periods (10 d). Each cage was washed daily with water or methanol after removing feces. The photoperiod was maintained under a 12-h light/dark cycle using an automatic system. The temperature and humidity were maintained at 22–25 ºC and 40–60%, respectively.

Preparation of dosing solution and administration

The dosing solution (5000 mg/L) for oral administration was prepared by mixing labeled and non-labeled clopidol with 150 mL of 0.5% carboxymethylcellulose sodium salt dissolved in sterilized water. Homogeneity was confirmed at the top, middle, and bottom of the dosing solution using LSC. After measuring the weight of each broiler, the above solution was orally administered at ~ 25 mg clopidol/kg body weight in a volume of each 5.2–6.4 mL before feeding.

Sample collection, preparation, and storage

The animals were euthanized using anesthetics such as rompun and succinylcholine prior to sample collection. Liver, fat, muscle, and kidney tissues were sampled from broilers at 6 h, 1, 3, 5, and 10 d after dose administration. At each sampling point, tissues were collected from four broilers. The same number of control samples (unexposed animals, 0 h) were also collected separately for analysis. The liver, fat, and muscle samples were homogenized using a sample mixer and dry ice. Kidney samples were homogenized using a tissue grinder. The samples were stored below –20 °C until analysis.

Sample pretreatment and extraction

The tissue samples (kidney, muscle, fat, and liver) were extracted twice with a solvent mixture (acetonitrile:water, 8:2, v/v). The extracts were centrifuged (Z383K, HERMLE, Wehingen, Germany), purified using MgSO4, primary secondary amine (PSA), octadecylsilane (C18E, end-capped), and graphitized carbon black (GCB). Purification of fat samples was performed without C18E or GCB. The purified samples were evaporated to 0.2 mL under nitrogen gas and reconstituted to 1.0 mL with DMSO.

The sample was filtered using a syringe filter (0.22 µm PVDF®, Whatman, Maidstone, UK) prior to analysis and a 0.1-mL aliquot of filtrate was mixed with 4 mL of scintillation cocktail (Insta-Gel Plus) for radioactivity quantification by LSC. Radio-HPLC was used to analyze the metabolites and clopidol. After extraction, the remaining tissues [non-extractable residues (NERs)] were dried (KED-132A, KITURAMI, Cheongdo, Korea), thoroughly mixed, and 0.1 g of dried sample was combusted with cellulose (0.1 g) in a sample oxidizer (Oxidizer 307, PerkinElmer). Subsequently, LSC was conducted to determine the radioactivity level associated with the NER. See Figure S2 for further details.

Instrumental analysis

The radioactivity was detected with a PerkinElmer liquid scintillation counter with DPM capabilities (Tri-Carb® 2910TR). All samples were measured in duplicate for 3 min. The NERs were combusted with cellulose in the sample oxidizer (PerkinElmer) with a scintillation cocktail (Monophase S), and radioactivity was determined by LSC. Radio-HPLC and LC–MS (HPLC/LC–MS, 1260 Infinity, 6420 Triple Quad LC/MS, Agilent, Santa Clara, USA) were used to determine the radiochemical purity, stability, and composition of the analytes (clopidol and its metabolite). Separation was performed using radio-HPLC and LC–MS in gradient mode with an Eclipse XDB-C18 column. The analysis was performed using a 3H-detector and electrospray ionization (ESI) in positive ion mode, as described in Tables S1 and S2.

Validation of analytical procedures and stability

The pretreatment and methodology were validated based on linearity, system suitability, accuracy, and precision. Each tissue matrix was subject to validation of its analytical procedures. For assessing the linearity, five concentrations (0.1–10.0 ng/mL) including the limit of quantitation (LOQ) were analyzed using LSC and Radio-HPLC. System suitability was determined through six replicate analyses of a standard solution (10.0 ng/mL) in terms of injection precision. The accuracy and precision results are represented by the recovery (%) and coefficient of variation (CV, %), respectively, obtained for three different concentrations analyzed in duplicate. The accuracy and precision of the developed method were assessed for three different concentrations (0.1, 1.0, and 10.0% of total administered dose) using a dosing solution before extraction. Following the addition of the standard solutions, extraction and pretreatment were performed as described in Sect. 2.5. The storage stability of the samples was assessed by spiking a known amount (1% of total administered dose) of labeled clopidol into the untreated samples. The samples were stored under the same conditions as those used for the dosing group.

Collection and identification of metabolite and clopidol in tissues

Clopidol and its metabolites detected in the tissues using radio-HPLC were isolated by elution from the HPLC column. The eluates were extracted twice for 5 min with a mixture of 20 mL of water saturated with sodium chloride, 20 mL of dichloromethane, and 20 mL of ethyl acetate. Organic solvent extracts were collected over anhydrous sodium sulfate, concentrated using nitrogen gas, and dissolved in 50% acetonitrile in water. Following extraction, LC–MS was conducted to validate the chemical structure of the metabolite through accurate mass measurements and fragmentation patterns. Concurrently, unmetabolized clopidol was identified by comparison with an authentic standard.

Health risk assessment

The estimated daily intake (EDI)—an indicator of the daily intake of antimicrobial agents via various pathways including food, beverages, and environmental exposure36,59,60—is calculated using Eq. (1), developed by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency:

|

1 |

where C is the mean concentration (mg/kg) of the target antimicrobial agent in the tissue sample, R is the daily consumption rate (g/d) of the average (p50) and high (p90) consumption groups, and BW is the average body weight of the consumers (kg). Data on broiler and related product consumption and the average body weight of South Koreans were obtained from the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI) and Statistics Korea (KOSIS)61,62 and are based on the latest census of 2021. For health risk assessment, the hazard quotient (HQ) was calculated using Eq. (2) by comparing the EDI of clopidol with the ADI provided by the Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives63.

|

2 |

The Microsoft Excel (ver. 16.0.5478.1002) and SigmaPlot® (ver. 14.0.3.192) software was used for statistical analyses and computing of graphs, as well as to calculate the average and deviation of residual concentrations and determine the values of the EDI and HQ. The mean EDI values for the broiler muscle and four tissues were calculated using the consumption data of the average (p50) and high (p90) consumer groups.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by a Grant [22192MFDS356] from the Ministry of Food and Drug Safety (2024), Republic of Korea.

Author contributions

Seong-Hoon Jeong and Hyeong-Jin Youn wrote original draft preparation, methodology data curation, and editing. Ji-young An, Jung-Hoon Jung, Jeong-Ran Min and Jong-Su Seo validated and analysis. Sang-Hee Jeong and Jong-Hwan Kim supervised and review. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by a Grant [22192MFDS356] from the Ministry of Food and Drug Safety (2024), Republic of Korea.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Consent to participate/consent to publish

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Seong-Hoon Jeonga and Hyeong-Jin Youna have contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Sang-Hee Jeong, Email: jeongsh@hoseo.edu.

Jong-Hwan Kim, Email: jjong@kitox.re.kr.

References

- 1.Korver, D. R. Review: Current challenges in poultry nutrition, health, and welfare. Animal17(2), 100755 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Milton, K. A hypothesis to explain the role of meat-eating in human evolution. Evol. Anthropol. Issues News Rev.8, 11–21 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mottet, A. & Tempio, G. Global poultry production: Current state and future outlook and challenges. Worlds Poult. Sci. J.73, 245–256 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Henchion, M., McCarthy, M., Resconi, V. C. & Troy, D. Meat consumption: Trends and quality matters. Meat Sci.98, 561–568 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mesa-Pineda, C., Navarro-Ruíz, J. L., López-Osorio, S., Chaparro-Gutiérrez, J. J. & Gómez-Osorio, L. M. Chicken coccidiosis: From the parasite lifecycle to control of the disease. Front. Vet. Sci.8, 787653 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sharma, M. K. & Kim, W. K. Coccidiosis in egg-laying hens and potential nutritional strategies to modulate performance, gut health, and immune response. Animals (Basel)14, 1015 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blake, D. P. et al. Re-calculating the cost of coccidiosis in chickens. Vet. Res.51, 115 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Noack, S., Chapman, H. D. & Selzer, P. M. Anticoccidial drugs of the livestock industry. Parasitol. Res.118, 2009–2026 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kant, V. et al. Anticoccidial drugs used in the poultry: An overview. Sci. Int.1, 261–265 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kadykalo, S. et al. The value of anticoccidials for sustainable global poultry production. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents51, 304–310 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Getahun, M., Abebe, R. B., Sendekie, A. K., Woldeyohanis, A. E. & Kasahun, A. E. Evaluation of antibiotics residues in milk and meat using different analytical methods. Int. J. Anal. Chem.2023, 4380261 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Matus, J. L. & Boison, J. O. A multi-residue method for 17 anticoccidial drugs and ractopamine in animal tissues by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry and time-of-flight mass spectrometry. Drug Test. Anal.8, 465–476 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hedges, S. et al. Antimicrobial residues in meat from chickens in Northeast Vietnam: Analytical validation and pilot study for sampling optimisation. J. Consum. Prot. Food Saf.19, 225–234 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sajid, A., Kashif, N., Kifayat, N. & Ahmad, S. Detection of antibiotic residues in poultry meat. Pak. J. Pharm. Sci.29, 1691–1694 (2016). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mestorino, N. et al. Residue depletion of ivermectin in broiler poultry. Food Addit. Contam. Part A Chem Anal. Control Expo. Risk Assess.34, 624–631 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gao, F. et al. Residue depletion of nifuroxazide in broiler chicken. J. Sci. Food Agric.93, 2172–2178 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li, Y. et al. Tissue deposition and residue depletion of cyadox and its three major metabolites in pigs after oral administration. J. Agric. Food Chem.61, 9510–9515 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu, Y. N. et al. Residue depletion of amoxicillin and its major metabolites in eggs. J. Vet. Pharmacol. Ther.40, 383–391 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bonassa, K. P. D. et al. Tissue depletion study of enrofloxacin and its metabolite ciprofloxacin in broiler chickens after oral administration of a new veterinary pharmaceutical formulation containing enrofloxacin. Food Chem. Toxicol.105, 8–13 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Agyare, C., Boamah, V. E., Zumbi, C. N. & Osei, F. B., (2018). Antibiotic use in poultry production and its effects on bacterial resistance in Antimicrobial Resistance—A Global Threat 33–51.

- 21.Chaturvedi, P. et al. Prevalence and hazardous impact of pharmaceutical and personal care products and antibiotics in environment: A review on emerging contaminants. Environ. Res.194, 110664 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Atta, A. H., Atta, S. A., Nasr, S. M. & Mouneir, S. M. Current perspective on veterinary drug and chemical residues in food of animal origin. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res.29, 15282–15302 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rushton, J., Ferreira, J. P. & Stärk, K. D. Antimicrobial Resistance: The Use of Antimicrobials in the Livestock Sector, (2014).

- 24.Stavroulaki, A. et al. Antibiotics in raw meat samples: Estimation of dietary exposure and risk assessment. Toxics10, 456 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Klátyik, S., Bohus, P., Darvas, B. & Székács, A. Authorization and toxicity of veterinary drugs and plant protection products: Residues of the active ingredients in food and feed and toxicity problems related to adjuvants. Front. Vet. Sci.4, 146 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Beyene, T. Veterinary drug residues in food-animal products: Its risk factors and potential effects on public health. J. Vet. Sci. Technol.7, 1–7 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rana, M. S., Lee, S. Y., Kang, H. J. & Hur, S. J. Reducing veterinary drug residues in animal products: A review. Food Sci. Anim. Resour.39, 687–703 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang, R. et al. Global stable-isotope tracing metabolomics reveals system-wide metabolic alternations in aging Drosophila. Nat. Commun.13, 3518 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim, J.-H. et al. Bioconcentration and metabolism of the new herbicide Methiozolin in ricefish (Oryzias latipes). J. Agric. Food Chem.69, 9536–9544 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xiao, X. et al. 13C-Stable isotope resolved metabolomics uncovers dynamic biochemical landscape of gut microbiome-host organ communications in mice. Microbiome12, 90 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.In Encyclopedia of Parasitology (ed. Mehlhorn, H.) 269-286 (Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2008)

- 32.Kanhere, M. Clopidol CAS 2071 90 6 Market Report 2025 (Global Edition). Report No. CMR758733, (Cognitive Market Research, 2024). Available at: https://www.cognitivemarketresearch.com/clopidol-cas-2971-90-6-market-report

- 33.Leroy Bjerke, E. & Herman, J. L. Collaborative study of clopidol in chicken tissues and eggs, using gas-liquid chromatography. J. Assoc. Off. Anal. Chem.57, 914–918 (1974). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fang, B., Su, Y., Ding, H., Zhang, J. & He, L. Determination of residual clopidol in chicken muscle by capillary gas chromatography-negative chemical ionization-mass spectrometry. Anal. Sci.25, 1203–1206 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pang, G. F. et al. Determination of clopidol residues in chicken tissues by high-performance liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. A882, 85–88 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang, W. et al. Insights into tissue accumulation, depletion, and health risk assessment of clopidol in poultry. Food Addit. Contam. Part A Chem Anal. Control Expo. Risk Assess.41, 771–781 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cameron, B. D., Chasseaud, L. F. & Hawkins, D. R. Metabolic fate of clopidol after repeated oral administration to rabbits. J. Agric. Food Chem.23, 269–274 (1975). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bonarriva, J. & Carlson, D. Global Economic Impacts of Missing and Low Pesticide Maximum Residue Levels, (2019).

- 39.Okunola, A., Dennis, E. & Beghin, J. Are veterinary drug maximum residue limits protectionist? Int. Evid. (2024).

- 40.Rahman, S. & Hollis, A. The effect of antibiotic usage on resistance in humans and food-producing animals: A longitudinal, One Health analysis using European data. Front. Public Health11, 1170426 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Alimentarius, C. CAC/GL 71–2009. Guidelines for the design and implementation of national regulatory food safety assurance programme associated with the use of veterinary drugs in food producing animals (Codex, Rome, 2009) Secretariat. Adopted.

- 42.Pihlström, T. et al. Analytical quality control and method validation procedures for pesticide residues analysis in food and feed SANTE 11312/2021. Sante11312, v2 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 43.OECD. OECD Guidelines for the Testing of Chemicals (OECD, 1994).

- 44.EMEA. Guidelines for the validation of analytical methods used in residue depletion studies in Vet.Med. InsP (Eur. Med. Agency, 2009).

- 45.Castillo, M. et al. An evaluation method for determination of non-polar pesticide residues in animal fat samples by using dispersive solid-phase extraction clean-up and GC-MS. Anal. Bioanal. Chem.400, 1315–1328 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bari, M. L. & Yeasmin, S. in Food Safety and Preservation (ed. Grumezescu, A. M. & Holban, A. M.) 195-229 (Acad. Press, 2018

- 47.Schäffer, A., Kästner, M. & Trapp, S. A unified approach for including non-extractable residues (NER) of chemicals and pesticides in the assessment of persistence. Environ. Sci. Eur.30, 51 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.World Health Organization evaluation of certain veterinary drug residues in food. World Health Organ. Tech. Rep. S., 1–134 (2009). [PubMed]

- 49.GL46, E. V. Studies to Evaluate the Metabolism and Residue Kinetics of Veterinary Drugs in Food-Producing Animals: Metabolism Study to Determine the Quantity and Identify the Nature of Residues (European Medicines Agency, 2011). Available at : https://www.fda.gov/media/78339

- 50.Marcacci, S., Raventon, M., Ravanel, P. & Schwitzguébel, J.-P. The possible role of hydroxylation in the detoxification of atrazine in mature vetiver (Chrysopogon zizanioides Nash) grown in hydroponics. Z. Naturforsch. C J. Biosci.60, 427–434. (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Surendradoss, J., Varghese, A. & Deb, S. in Biologically Active Small Molecules 287-332 (Apple (Acad. Press, 2023)).

- 52.Chiang, J. Liver Physiology: Metabolism and Detoxification, (2014).

- 53.Prakash, C. & Vaz, A. D. Drug Metabolism: Significance and Challenges (Wiley, 2009). [Google Scholar]

- 54.Martins, F. S., Schaller, S. & Franco, L. D. J. in The Art and Science of Physiologically-Based Pharmacokinetics Modeling 118–130 (CRC Press).

- 55.Pang, G. F., Cao, Y. Z., Fan, C. L., Zhang, J. J. & Li, X. M. Determination of clopidol residues in chicken tissues by liquid chromatography: part II. Distribution and depletion of clopidol in chicken tissues. J. AOAC Int.84, 1343–1346 (2001). [PubMed]

- 56.Lee, S., Choo, G., Ekpe, O. D., Kim, J. & Oh, J.-E. Short-chain chlorinated paraffins in various foods from Republic of Korea: Levels, congener patterns, and human dietary exposure. Environ. Pollut.263, 114520 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Habumugisha, T. et al. Older adults’ perceptions about meat consumption: A qualitative study in Gasabo district, Kigali. Rwanda. BMC Public Health24, 1515 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fei, Z. et al. Antibiotic residues in chicken meat in China: Occurrence and cumulative health risk assessment. J. Food Compos. Anal.116, 105082 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kamaly, H. F. & Sharkawy, A. A. Health risk assessment of metals in chicken meat and liver in Egypt. Environ. Monit. Assess.195, 802 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hossain, E., Nesha, M., Chowdhury, M. A. Z. & Rahman, S. H. Human health risk assessment of edible body parts of chicken through heavy metals and trace elements quantitative analysis. PLoS ONE18, e0279043 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.KHIDI. Korean Health Industry Development Institue and the National Survey of Exposure Factors, (2021).

- 62.KOSIS. Distribution of Average Weight by Province, Age, and Gender, (2022).

- 63.JECFA. Safety Evaluation of Certain Veterinary Drug Residues (JECFA/98/SC), (2024).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information.