Abstract

Background

Motivating the immune system to target tumour cells plays an increasingly prominent role in the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), but challenges such as low overall response rates persist in current clinical practice. Tumour cell MHC-Class-I (MHC-I) downregulation and antigen loss are typical mechanisms of immune evasion. To this end, a dual-functional RNA-based strategy was conceived for HCC immunotherapy.

Methods

MHC-I expression on HCC and paratumour tissues from patients was assessed, and the correlations between MHC-I regulators and HCC prognosis were analyzed. Small interfering RNA (siRNA) targeting proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) and mRNA encoding tumour antigens were encapsulated in a fluorinated lipid nanoparticle (LNP), which direct nucleic acids primarily to the liver, making it ideal for HCC treatment. Anti-tumour efficacy was investigated in an orthotopic HCC model, with single-cell RNA sequencing used for in-depth analysis of the tumour microenvironment (TME).

Results

A marked downregulation of MHC-I expression was observed in HCC tumour cells from a cohort of patients, with this MHC-I suppression correlating with poor prognosis and diminished responsiveness to immunotherapy. Among the various MHC-I regulators, PCSK9 is the only one that shows a significant correlation with the prognosis of HCC patients. Knockdown of PCSK9 inhibited MHC-I degradation and thus increased the efficiency of antigen presentation by up to sixfold compared to untreated tumour cells. The hybrid RNA LNPs (h-LNP) enhanced Th1-mediated immune responses, reinvigorating and expanding anti-tumour immunity within the TME. Following treatment with h-LNPs, the TME showed a pronounced infiltration of CD8+ T cells and NK cells, coupled with a significant reduction in immune-suppressive populations, such as M2-like macrophages, in contrast to the controls. These changes in the immune landscape were accompanied by a marked inhibition of tumour growth in an orthotopic HCC model as well as melanoma, where this dual-functional RNA-regulated system outperformed the control groups.

Conclusions

The present study successfully engineered a dual-functional RNA-regulated system that augments tumour cell antigen presentation and reconfigures the immune landscape within the TME, thereby potentiating the anti-tumour efficacy of the mRNA vaccine.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12943-025-02480-x.

Keywords: Hepatocellular carcinoma, Tumour immunotherapy, Drug delivery, RNA vaccine

Background

In multiple advanced solid malignancies, such as hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), melanoma etc., the application of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI) has been recommended as a cornerstone of front-line therapy, effectively prolonging patient survival [1–7]. Meanwhile, the mRNA vaccine, emerging as an another highly promising therapeutic strategy for cancer treatment, targets personalized neoantigens or tumour-associated antigens and has been proven to elicit high-magnitude antigen-specific T cell responses. Clinical trials have demonstrated survival benefits from mRNA vaccine in part of participants [8, 9]. Nevertheless, challenges remain in immunotherapy, particularly low response rate [3, 5, 10–13]. The objective response rate (ORR) was 17% and 27.3–36% for atezolizumab monotherapy and atezolizumab with bevacizumab in advanced HCC, respectively [5, 11], and ~ 40% for nivolumab in advanced untreated melanoma [12, 13]. Likewise, the ORR for mRNA vaccine in advanced melanoma or HCC was reported as 50% in the phase I trials [8, 9]. A typically described pathway of immune evasion is the downregulation of MHC-class-I (MHC-I) protein levels [14–16]. The tumour-eradicating immunity relies chiefly upon CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) recognizing the cognate antigen-derived epitope binding MHC-I molecules [17]. Downregulation of MHC-I reduces CTL recognition sites on tumour cell surface, hindering CTL recognition and killing of tumour cells. Analysis on HLA class I (HLA-I) gene expression through immunofluorescence sections demonstrated that protein HLA-I was downregulated in HCC tumour tissues compared to the paratumoural tissues, and HLA-I expression level positively correlated with HCC patient prognosis and immunotherapy responsiveness. These data emphasize that MHC-I downregulation acts as one of crucial mechanisms in immunotherapy resistance, highlighting the need to boost tumour MHC-I expression and enhance antigen presentation to improve treatment effectiveness [18–20].

Loss of tumour antigens is another crucial mechanism of immune evasion [21, 22]. Tumour antigen-derived epitopes together with MHC-I constitute the ligand of CD8+ T cell receptors (TCRs). The loss of tumour antigens generated from genetic deletions, mutations, or epigenetic regulations disrupts antigen presentation, undermining the recognition and killing effect of the existing CTLs on tumour cells. Furthermore, immune editing caused by the selective killing of epitope-MHC-I positive tumour cells allows the antigen-negative cells to accumulate and proliferate in the tumour [23, 24], aggravating immunotherapy resistance. Specifically, neoantigen mutation burden have been proved to correlate with tumour penetration of CTLs and higher diversity of TCRs, which predicted the sensitivity of immunotherapy [25–27].

Herein, we conceived a dual-functional RNA regulated system to counteract tumour cell MHC-I downregulation and antigen loss. The system encapsulated small interfering RNA (siRNA) and mRNA within a fluorinated lipid nanoparticle (LNP) which comprises fluorine modified 1, 2-Distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-Poly(ethylene glycol)−2000 (PEG-DSPE) and has been proven to deliver nucleic acids with high efficiency and biocompatibility in our previous study [28]. Fluorinated LNPs efficiently direct nucleic acids primarily to the liver, a distinctive property that makes them well-suited for HCC treatment. In this dual-functional RNA regulated system, siRNA targets proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) and mRNA encodes tumour antigens. PCSK9, initially demonstrated to bind the low-density lipoprotein receptor and induce its degradation in hepatocytes [29], also binds to MHC-I molecules on cancer cell membrane, promoting their lysosomal degradation and subsequently impairing antigen presentation [30]. Among the various MHC-I regulators, PCSK9 is the only one that shows a significant correlation with the prognosis of HCC patients. We substantiated PCSK9 knockdown could elevate the component of MHC-I up to ~ 2.5-fold compared to the original tumour cells. This effect was selectively observed in tumour cells, rather than immune cells, due to the predominant expression of PCSK9 in the liver. The dual-functional RNA regulated system upregulated antigen presentation level up to sixfold. Intratumoural application reprogrammed tumour microenvironment (TME) toward a potentiated anti-tumour state, yielding potent therapeutic effects on both ectopic and orthotopic mouse tumour models.

Materials and methods

Patients

Individuals who received radical surgery for HCC at the First Affiliated Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine (year 2016–2019), were collected and recorded. All patients were evaluated preoperatively using imaging technologies, such as CT and MRI. Clinical diagnosis before surgery was confirmed by postoperative paraffin pathology. Patient management was guided by Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) system [31]. Patients were included into this study when the following criteria are met: (I) age between 18 and 75 years; (II) Child–Pugh score ≤ 7; (III) tumour stage A-B according to BCLC staging system; (IV) performance status of 0 or 1 based on ECOG system. Exclusion criteria for patients were: (a) postoperative paraffin pathology indicated mixed hepatocellular-cholangiocarcinoma; (b) incomplete information on clinicopathological features; (c) lost to follow-up. Finally, tumour specimens were collected from 48 patients, with follow-up information available for 44 of them. Preoperative ICI therapy was performed to patients in BCLC stage B or stage A but R0 resection was technically unachievable. Response to treatment was assessed using the RECIST 1.1 criteria (Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumours). Complete response and partial response were both classified as responder group, while those with stable disease or disease progression were categorized as non-responders [32]. Tumour and paratumoural samples were acquired from surgical specimens. The study adhered to the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki and received approval from the Clinical Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine (2022–161).

Materials

AVT (Shanghai) Pharmaceutical Tech Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China) provided the following lipids: Heptadecan-9-yl-8-((2-hydroxyethyl)[6-oxo-6-(undecyloxy) hexyl]amino) octanoate (SM-102, O02010), cholesterol (O01001), 1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DSPC, S01005). The fluorinated PEG-lipid was synthesized as previous report [28]. PCSK9 siRNA was synthesized by Suzhou Biosyntech Co., Ltd. (Suzhou, China). The sequence of PCSK9 siRNA is GmsGmsAmCmGfAmGfGfAfUmGmGmAmGmAmUmUmAmUm. eGFP (L-7601) and ovalbumin (OVA) mRNA (L-7610) were provided by TriLink Biotechnologies. Antibodies used in flow cytometry, immunohistochemical, immunofluorescence analysis and western-blotting were presented as Supplementary Table 3. The OVA257-264 (SIINFEKL) peptide was synthesized by Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co.,Ltd. (Beijing, China, CLP0705), and was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). All the reagents were used without any further purification unless another notified.

Mice

C57BL/6 mice with body weight of 20 g were purchased from Hangzhou Medical College. All mice were housed in a standard and germ-free setting and acclimated for a minimum of 2 days prior to the experiments. All animal studies followed the protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at The First Affiliated Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine (2023–536). Every procedure complied the ethical regulations.

Cell lines

The B16-OVA cell line was kindly gifted by Dr. Xiao Zhao from the National Center for Nanoscience and Technology, Beijing, China. The Hepa1-6 cell line was obtained from the Cell Bank of the Chinese Academy of Sciences and was engineered with ovalbumin (OVA). Both cell lines were cultured with complete RPMI 1640 medium (the medium contains 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin–streptomycin). Cells were kept in a culture incubator (37 °C, 5% CO2, ThermoFisher Scientific).

Preparation of mRNA vaccine particles

To get the aqueous phase, mRNA/siRNA stock solution was dispersed into citrate buffer (10 mM, pH = 4) in a concentration of 0.072 μg/μL. For h-LNPs (containing both mRNA and siRNA molecules) preparation, mRNA and siRNA were pre-mixed in a specific weight ratio. Lipids were mixed in ethanol at a molar ratio of 50:10:38.5:1.5 (SM-102: DSPC: cholesterol: fluorinated PEG-lipid). The concentration of total lipids was 8 mM. Subsequently, the former phase was mixed into the latter phase by pipette. The volume ratio of aqueous and ethanol phase was 3:1. After that, the vaccine particles were washed by phosphate buffer saline (PBS, pH = 7.4) to remove ethanol. The dilution was transferred to an Amicon ultra centrifugal filter (Merck, MWCO: 10,000, UFC9010D), and then centrifuged at 2000 g per minute to concentrate the vaccine particles (30 min/cycle, 2–3 cycles). The ethanol concentration in the vaccine solution was diluted to less than 2% (v/v). Quant-IT™ RiboGreen™ RNA analysis kit was used to calculate encapsulation efficiency based on the manufacturer’s instruction. The encapsulation efficiency was maintained above 90% in each experiment. The prepared particles were stored at 4 ℃ for later use.

Evaluation of PCSK9 knockdown efficiency

Hepa1-6-OVA cells were incubated overnight in complete RPMI 1640 medium in a 12-well plate. After then, they were treated by hybrid nucleic acid LNPs or controls, each containing equal amounts of nucleic acids, for 48 to 72 h. Proteins were extracted from the treated cells by using RIPA lysis buffer supplemented with a protease inhibitor. Western-blotting was conducted to detect PCSK9 protein level. The operating steps followed the general western-blotting protocol.

Flow cytometry

To assess mRNA transfection efficiency, Hepa1-6-OVA cells were plated in 24-well plates and incubated overnight. The next day, these cells were incubated with h-LNPs or control formulations containing equal amounts of nucleic acids for 24 h. The cells were harvested. After staining with SYTOX™ Blue Nucleic Acid Stain, the percentage of eGFP-expression cells was analyzed through a flow cytometer (LSR Fortessa, BD, U.S.).

To measure the effect of PCSK9 knockdown on antigen presentation in vitro, Hepa1-6-OVA cells were co-incubated with h-LNPs or controls containing equal amounts of nucleic acids for 48–72 h. Cells were harvested and sequentially stained with CD16/32 TruStain FcX, anti-H-2Kb, anti-SIINFEKL-H-2 Kb antibody according to the manufacturer’s guideline. SYTOX™ Blue Nucleic Acid Stain reagent was used to exclude dead cells. After that, antigen presentation was analyzed through flow cytometry (LSR Fortessa, BD, U.S.).

To evaluate the immune responses induced by h-LNP or controls, spleens, tumour draining lymph nodes (TdLNs), and tumours were collected according to the in vivo study protocol. Spleens or TdLNs were pulverized in complete medium. Tumours were cut into pieces and single cell suspensions were acquired through incubating tumour pieces in digestion buffer that contained 1 mg/mL hyaluronidase and 0.5 mg/mL collagenase IV. Two million cells were co-incubated with anti-CD45, CD3, CD4, CD8, CD11b, CD11c, F4/80, and SIINFEKL-H-2 Kb antibodies based on the manufacturer’s guidelines. Dead cells were excluded by SYTOX™ Blue Nucleic Acid Stain reagent before analyzing through flow cytometry (BD Accuri C6 flow cytometer, BD Bioscience, San Jose, CA).

For intracellular IFN-γ analysis, 3 million splenocytes, TdLN-derived cells, or tumour-derived single cells were plated in 24-well plates and cultured ex vivo. These cells were incubated with OVA257-264 peptide for 12–16 h (10 μg/mL). Protein transport inhibitor cocktail was added to inhibit IFN-γ extracellular secretion. After that, cells were co-incubated with specific antibodies that recognized surface markers. After that, the cells were dealt with the Fixation/Permeabilization Solution Kit (BD) for fixation and permeabilization. Afterward, they were incubated with anti-IFN-γ antibody. Samples were analyzed using a flow cytometer (LSR Fortessa, BD, U.S.). Flow cytometry data were processed with FlowJo X software.

Animal studies

To investigate the therapeutic effectiveness of h-LNPs, ectopic HCC tumour model or melanoma tumour model was built through subcutaneous injection using Hepa1-6-OVA or B16-OVA cell lines (0.5–1 million of tumour cells per mouse in female C57BL/6 mice), respectively. h-LNPs or controls were applied to tumour bearing mice after tumour volume reaching ~ 100 mm3 through intratumoural injection. Treatments were repeated on day 4 post-primary vaccination. The therapeutic reagent for each mouse contained 10 μg nucleic acids. Tumour volume was recorded and compared among groups. The tumour size was calculated as 0.5 × length × width × width. To detect the immune responses elicited by h-LNPs, TdLNs, spleens and tumours were collected on day 4 post-second treatment. Particularly, tumours were harvested 48 h after a single treatment for antigen presentation analysis.

To assess the therapeutic efficacy of h-LNPs on orthotopic HCC model, 1 million of Hepa1-6-OVA cells were injected into mouse liver. Three days later, h-LNPs or controls containing equal amounts of nucleic acids were administrated through tail vein injection. PET-CT (SIEMENS, Inveon PET-CT, U.S.) was performed to evaluate tumour size. In brief, mice were administrated with 18F-FDG through tail vein injection after anesthesia. PET-CT scan was performed after 45 min. The survival period was recorded and compared among groups.

Immunohistochemistry and immunofluorescence

Immunohistochemistry and immunofluorescence of tumour tissues were performed in our pathology core. In brief, tumour samples were immersed in 4% paraformaldehyde overnight and subsequently embedded in paraffin. After slicing, deparaffinization and rehydration were sequentially conducted with xylene and a graded series of alcohols. The slices were heated in citrate buffer (pH 6.0) by microwave to retrieve antigens, followed by staining with primary antibodies that specifically bound to HLA-ABC, CD4, CD8, H-2Kb, or SIINFEKL-H-2Kb for immunofluorescence, or CD3 for immunohistochemistry, 4 ℃ overnight. After incubation, the slides were washed with PBS three times for 5 min each to remove excess antibody. The sections were then mounted with a mounting medium containing DAPI for nuclear staining and observed under a fluorescence microscope. For immunohistochemistry, the sections were washed with PBS and incubated with a secondary antibody conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (HRP). After additional washing, color development was achieved using a substrate (DAB), and the sections were counterstained with hematoxylin. Finally, the slides were dehydrated, cleared, and mounted for microscopic examination. Patients were categorized into HLA-ABC high and HLA-ABC low groups based on the median of fluorescence intensity. Fluorescence quantitative analysis was performed through Fiji ImageJ [33].

Tumour scRNA-seq

HCC tumour model was established on C57BL/6 mice (6–8 weeks old). Vaccination was inoculated twice as previously described. On day 4 after the second vaccination, tumour samples from each mouse were collected, cut into small fragments using scissors, and then co-incubated into enzymatic digestion with collagenase IV (0.5 mg/mL) and hyaluronidase (1 mg/mL) to prepare a single-cell suspension. Single-cell suspensions from three mice per group were aggregated into a single pooled sample for further analysis. Approximately 10,000 viable cells from each group were subsequently loaded onto a 10X Genomics GemCode Single-cell platform to create single-cell Gel Bead-In-Emulsions (GEMs). cDNA libraries were constructed and sequenced by utilizing the Chromium Next GEM Single Cell 3' Reagent Kits v3.1. The entire workflow, including GEM generation, cDNA amplification, library preparation, and sequencing, was carried out by Gene Denovo Biotechnology.

The raw scRNA-seq expression data from 10X Genomics were processed with CellRanger software (version 7.1.0), using the GRCh38 human transcriptome as the reference genome. The output, a gene-cell matrix containing unique molecular identifiers (UMIs), was further analyzed in R (version 4.4.0) with the Seurat package (version 4.4.0). Quality control was implemented based on the following criteria: (1) cells expressing between 300 and 7,500 genes, (2) UMI counts (nCount_RNA) below 1e-5, and (3) mitochondrial gene expression less than 25%. After applying these filters, the final dataset included 12,588 cells from the PBS group, 7,427 from the m-LNP group, and 8,400 from the h-LNP group. The UMI count matrix was normalized using Seurat’s NormalizeData function, where each gene's UMI count was divided by the total UMIs per cell, scaled by 10,000, and log-transformed. Batch effects across samples were mitigated using RunHarmony to integrate the data.

For dimension reduction and unsupervised clustering, we began by selecting the top 2,000 genes with the greatest cell-to-cell variation by applying the FindVariableFeatures function with default settings to reduce noise. Initial clustering was conducted using FindNeighbors and FindClusters, with a resolution of 1.5, and the resulting clusters were annotated according to known marker genes. After identifying the major cell types, we performed an additional round of clustering within each cell type to explore functional subsets. The final clustering results were visualized using UMAP through the RunUMAP function with default parameters and a perplexity of 20.

Gene set enrichment analysis was performed to explore the functional characteristics of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between macrophage subtypes using the clusterProfiler R package (version 3.14.3). DEGs were initially identified with the FindMarkers function, applying default settings and filtering for genes having an adjusted P-value of less than 0.05 and an absolute fold change (|FC|) > 0.25. These genes were then analyzed for enrichment in biological processes. GO terms having an adjusted P-value of less than 0.05, calculated using the Benjamini–Hochberg correction, were considered significant. The analysis code is accessible on Github.

To calculate the M1 and M2 polarization scores on the population of macrophages-1 and macrophages-2, signature sets of M1 and M2 polarization were established as gmt files. The related gene sets were presented as Supplementary Table 3. The AddModuleScore function in Seurat was applied with default parameters to assign a score for each signature in every macrophage, and the mean score across all cells within each macrophage subset was calculated.

The macrophage developmental trajectory was reconstructed using Monocle2 within the R environment (version 4.4.0). Pseudotime analysis, performed with Monocle2 (version 2.32.0), was used to trace the differentiation pathway of cells. The UMI matrix was first extracted from the Seurat object, and a Monocle dataset was created using the newCellDataSet function. Genes with an average expression level above 0.1 were selected for trajectory analysis. Genes with high variability, exhibiting an average expression greater than 0.3, were selected for further analysis. Dimensionality reduction was conducted using the DDRTree algorithm, and cells were ordered along the trajectory using the orderCells function.

Gene expression profiling interactive analysis

To analyze the prognostic value of MHC-I gene expression regulators in HCC, we used the Gene Expression Profiling Interactive Analysis (GEPIA) tool. The MHC-I gene expression regulators in our analysis included PCSK9, IRF1 (interferon regulatory factor 1), IRF2, IRF3, IFN-γ (interferon-gamma), SUSD6 (surface protein sushi domain containing 6), NLRC5 (NLR family CARD domain containing 5), TMEM127 (transmembrane protein 127), STAT1, and the WWP2 (E3 ubiquitin ligase). First, we entered the gene symbols of MHC-I regulators into the search bar on the GEPIA website. After selecting the TCGA dataset for HCC, we performed survival analysis to assess the correlation between the expression levels of these genes and patient outcomes. The median was used to define high and low expression levels of the MHC-I gene expression regulators. The tool generated survival curves comparing overall survival (OS) between HCC patients with high and low expression levels.

Statistics

Mean ± s.d. was presented for all measurement data. A two-tailed Student’s t test was applied to compare two independent groups, while one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s HSD post hoc test was performed when comparing more than two groups. Kaplan–Meier analysis and logrank test were utilized to analyze survival. Statistical analysis was completed within GraphPad Prism8.0.1. P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Results

Low HLA class I expression level in tumour cells correlates with poor prognosis of HCC

HCC and paratumoural samples were collected from 48 clinical cases who received hepatectomy. The clinical characteristics of these patients, including serum tumour biomarker levels represented by alpha-fetoprotein (AFP), tumour size, and Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) stage, were summarized in Supplementary Table 1. Patients received regular postoperative follow-up and their prognosis information were recorded, including disease-free survival (DFS) as well as overall survival (OS). HLA class I (HLA-I, HLA-ABC) expression was detected through immunofluorescence and compared between tumour and paratumour tissues. HLA-ABC was downregulated in tumours compared with paratumour tissues (Fig. 1a, b). Furthermore, HLA-I expression level was positively correlated with patients DFS and OS (Fig. 1c, d). Patients were categorized into HLA-ABC high and HLA-ABC low groups based on the median HLA-ABC expression intensity, as determined by the fluorescence intensity in the immunofluorescence sections. Survival analysis was conducted to compare the prognosis of patients in HLA-ABC high and HLA-ABC low group. Kaplan–Meier survival curve revealed that the DFS for HLA-ABC high group was longer than that for HLA-ABC low group across the study period (median DFS, 20 vs. 69 months, P = 0.0451) (Fig. 1e). Patients with a high level of HLA-ABC in tumours had longer OS compared with those with low HLA-ABC expression (median OS, 34 months vs. undefined, P = 0.0048) (Fig. 1f). These results indicate HLA-I expression level of HCC tumours correlates with patient prognosis.

Fig. 1.

The correlation between MHC-I gene expression and prognosis as well as immunotherapy responsiveness. a Representative immunofluorescence exhibiting HLA-ABC in paratumoural and HCC tissue. Scale bar of 50 μm. b Fluorescence quantitative analysis on HLA-ABC in paratumoural and HCC tissues. n = 48. Paired t test was performed for statistical analysis. c, d Scatterplot showing Pearson's correlation between the integrated density of HLA-ABC immunofluorescence and DFS (c), and between integrated density and OS (d), n = 44. e, f Kaplan–Meier plots of DFS (e) and OS (f) for HLA-ABC low and high group. g The integrated density of HLA-ABC immunofluorescence in non-responders (n = 9) and responders (n = 5) who received ICI therapy. h Tumour growth curve of PBS, non-Responders and Responders group. n = 10. Subcutaneous HCC tumour model was established with Hepa1-6-OVA cells. Mice received PBS or m-LNP treatment when tumour reached ~ 100 mm3 and vaccination was repeated 4 days later. i, j Scatterplot showing Pearson's correlation between the tumour volume and H-2Kb expression (i) as well as between tumour volume and SIINFEKL-H-2Kb levels in tumour cells detected by flow cytometry (j), n = 20. k, l H-2Kb expression (k) and SIINFEKL-H-2Kb levels in tumour cells (l) were compared between non-Responders and Responders group. n = 10. Data are expressed as mean ± s.d. Statistical significance was calculated through an unpaired Student’s t-test or one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s HSD post hoc test. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ns, no significant difference

Among these 48 patients, 14 patients received ICI therapy before surgery. And 5 out of 14 responded to ICI therapy. Fluorescence quantitative analysis showed that the enhanced HLA-ABC protein level in ICI responders was demonstrated compared to that in ICI non-responders (Fig. 1g). We then conducted spatial transcriptome analysis on HCC samples from patients. The tissue slide showed the morphological feature of interwoven distribution of normal and malignant tissues (Supplementary Fig. 1a, b). The expression levels of HLA-A/B/C were downregulated in malignant tissue compared to normal tissue (Supplementary Fig. 1c). CD8+ T cells, as well as other immune cells, tended to accumulate in areas with relatively high expression levels of HLA-A/B/C (Supplementary Fig. 1 d, e). There was a positive correlation between HLA-A/B/C expression levels and immune cell infiltration, especially CD8+ T cells and macrophages (Supplementary Fig. 1f). To validate the association between MHC-I gene expression and mRNA vaccine responsiveness, Hepa1-6-OVA subcutaneous tumour model was established in mice and received OVA mRNA vaccine (m-LNP) through intratumoural injection. Partial individuals responded to mRNA vaccine treatment (Fig. 1h). The median of tumour volume was set as the cutoff value to divide mice into responders and non-responders. MHC-I expression level as well as antigen presentation efficiency of tumour cells negatively correlated with tumour growth (Fig. 1i, j). MHC-I protein levels and antigen presentation efficiency in mRNA vaccine responders were higher than those in non-responders (Fig. 1k, l). These results confirm the association between MHC-I gene expression and immunotherapy responsiveness.

Dual-functional RNA regulated system augments antigen presentation by tumour cells

A variety of factors have been identified as participants in regulating MHC-I gene expression, including PCSK9, IRF1 (interferon regulatory factor 1), IRF2, IRF3, IFN-γ (interferon-gamma), SUSD6 (surface protein sushi domain containing 6), NLRC5 (NLR family CARD domain containing 5), TMEM127 (transmembrane protein 127), STAT1, and the WWP2 (E3 ubiquitin ligase) [17, 20, 30]. We investigated the associations between HCC prognosis and these reported MHC-I regulators through Gene Expression Profiling Interactive Analysis and noted that high PCSK9 expression correlated with poor HCC OS. No significant correlations were found in other factors (Supplementary Fig. 2), thus positioning PCSK9 as a target for intervention in HCC immunotherapy.

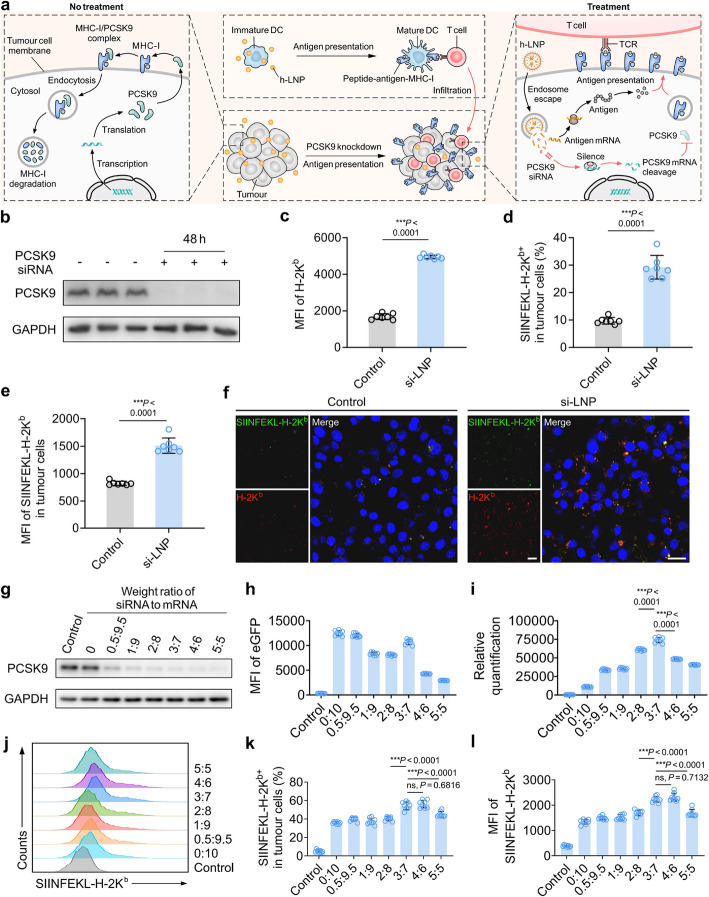

In melanoma, PCSK9 can mediate MHC-I degradation through lysosome pathway [30]. Therefore, we envisioned that downregulation of PCSK9 in HCC cells could also upregulate MHC-I level and promote their antigen presentation, thereby sensitizing HCC to mRNA vaccine treatment. PCSK9 siRNA was incorporated into antigenic mRNA LNP (m-LNP) to form a dual-functional RNA regulated system, hybrid nucleic acid LNP (h-LNP). The tumour-antigen-encoding mRNA molecules are delivered by h-LNP into antigen presentation cells (APCs), activating APCs and consequently initiating CTLs growth. In tumour cells, the RNA regulated system assists tumour cells to produce more antigens and increase MHC-I level, both of which promote tumour antigen presentation. The increased abundance of epitope-MHC-I complexes on tumour cell surface facilitates the infiltration of immune cells (Ref [34]) into TME and enhances the ability of CTLs to exert their killing effect (Fig. 2a).

Fig. 2.

Schematic and characteristics of PCSK9 knockdown to enhance MHC-I expression and epitope presentation in tumour cells. a Schematic illustrating: PCSK9 mediated MHC-I degradation, PCSK9 knockdown elevating MHC-I level and epitope presentation, antigen encoding mRNA activating antigen specific T cells and promoting T cells infiltration into tumours. b Western blotting showing PCSK9 siRNA knockdown efficiency. Hepa1-6-OVA cells were incubated with PCSK9 siRNA encapsulated in LNP (si-LNP) for 48 h. Nonsense siRNA encapsulated in LNP as control. c MFI of H-2Kb in Hepa1-6-OVA cells. n = 7. d Percent of SIINFEKL-H-2Kb+ cells in Hepa1-6-OVA cells. n = 7. e MFI of SIINFEKL-H-2Kb in Hepa1-6-OVA cells. n = 7. f Representative confocal images of Hepa1-6-OVA cells stained with anti-H-2Kb (Red) and anti-SIINFEKL-H-2Kb (Green) antibodies after PCSK9 si-LNP or nonsense si-LNP treatment. Scale bar, 20 μm. g Western blotting showing PCSK9 knockdown efficiency by hybrid nucleic acid LNP (h-LNP). Hepa1-6-OVA cells were co-incubated with h-LNP for 48 h. h-LNP encapsulated different weight ratio of PCSK9 siRNA and eGFP mRNA. h MFI of eGFP in Hepa1-6-OVA cells treated with different h-LNPs formulations. n = 8. i Ratio of eGFP MFI to PCSK9 integrated density. n = 8. j Representative plots from flow cytometry indicating SIINFEKL-H-2Kb in Hepa1-6-OVA cells. k Percent of SIINFEKL-H-2Kb+ cells in Hepa1-6-OVA cells. n = 8. l MFI of SIINFEKL-H-2Kb in Hepa1-6-OVA cells. n = 8. Data are showed as mean ± s.d. An unpaired Student’s t-test was performed for two-group comparison, while one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s HSD post hoc test was employed for comparisons among three or more groups. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. ***P < 0.001

After HCC cells were treated with PCSK9 siRNA encapsulated in LNP (si-LNP), the protein level of PCSK9 decreased by over 90% (Fig. 2b, Supplementary Fig. 3). Knocking down PCSK9 resulted in an upregulation of MHC-I level (Fig. 2c). In order to analyze the antigen presentation efficiency, ovalbumin (OVA) expressing Hepa1-6 cells (Hepa1-6-OVA) was engineered. Following treatment with si-LNP, the antigen presentation efficiency was improved, as evidenced by the ~ threefold increase in the percent of SIINFEKL-H-2Kb positive cells against the control group (Fig. 2d). The expression abundance of SIINFEKL-H-2Kb was also enhanced relative to the control group (Fig. 2e). These effects generated by PCSK9 knockdown were also proved by in vitro confocal microscopy analysis (Fig. 2f).

Accordingly, hybrid nucleic acid vaccine was designed through encapsulating PCSK9 siRNA into m-LNPs, mobilizing tumour-specific T cell responses and synergistically increasing antigen presentation by tumour cells. The weight ratio of siRNA to mRNA in LNPs for achieving optimal antigen presenting capacity was explored in vitro. PCSK9 knockdown efficiency elevated with the increase of siRNA content in the RNA regulated system, while the mRNA expression intensity was moderately crippled (Fig. 2g, h, Supplementary Fig. 4). When the weight ratio was set to 3:7, PCSK9 knockdown efficiency and the encoded protein level were balanced, evidenced by that the ratio of the encoded protein to PCSK9 protein level reached maximum (Fig. 2i). To further demonstrate the optimal weight ratio of siRNA to mRNA, eGFP mRNA was replaced by OVA mRNA for antigen presentation analysis. The optimal level of SIINFEKL-H-2Kb complex on tumour cell membrane was acquired when the ratio was set to 3:7 (Fig. 2j-l). These findings suggested that PCSK9 siRNA incorporated into m-LNP in a weight ratio of 3:7 could efficiently knock down PCSK9 in tumour cells and facilitated their antigen presentation capacity. Therefore, the 3:7 (weight ratio of PCSK9 siRNA to mRNA) was selected for the following h-LNP preparation and exploration.

Promotion efficacy of h-LNP on antigen presentation and immune responses in vivo

In vitro exploration has shown that h-LNP could enhance antigen presentation in tumour cells compared with m-LNP. Whether such effect could be acquired in vivo was investigated. Hepa1-6-OVA subcutaneous tumour model was built and then mice received h-LNPs and controls through intratumoural injection. Two days after primary treatment, the antigen presentation by tumour cells and APCs were analyzed through flow cytometry. The level of SIINFEKL-H-2Kb complex on tumour cell membrane in h-LNP treated group was ~ sixfold higher than that in untreated group and about twice as high as that in si-LNP or m-LNP treated group (Fig. 3a, b). The increased MHC-I and antigen presentation efficiency in tumour cells was substantiated through immunofluorescence (IF) sections and the corresponding quantitative analysis (Fig. 3c, Supplementary Fig. 5). Besides, h-LNP treatment induced the optimal antigen presentation in APCs against controls (Fig. 3d, e). Local and systemic immune responses were investigated through analyzing tumour draining lymph node (TdLN) and spleen. h-LNP treatment induced the proliferation of T cells and increased the percent of CD8+ T cells in the whole T cell population in both TdLN and spleen (Fig. 3f, g). Most importantly, h-LNP treatment increased IFN-γ secretion T cell levels ~ threefold in spleen and ~ 1.5-fold in TdLN compared to the m-LNP group (Fig. 3f, g).

Fig. 3.

h-LNP treatment improves MHC-I expression and antigen presentation by tumour cells and induces immune responses. a, b Flow cytometry analysis of SIINFEKL-H-2Kb+ cells on Hepa1-6-OVA tumours. The results were gated on CD45− cells. c Representative immunofluorescence (IF) sections exhibiting H-2Kb+ and SIINFEKL-H-2Kb+ cells in tumours. Scale bar, 20 μm. d, e Flow cytometry analysis of SIINFEKL-H-2Kb in macrophages and CD11c+ DCs from tumours. f, g Flow cytometry analysis of T cells in spleens and TdLNs. Data are presented as mean ± s.d. n = 5. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s HSD post hoc test was employed for comparisons among three or more groups *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. ***P < 0.001

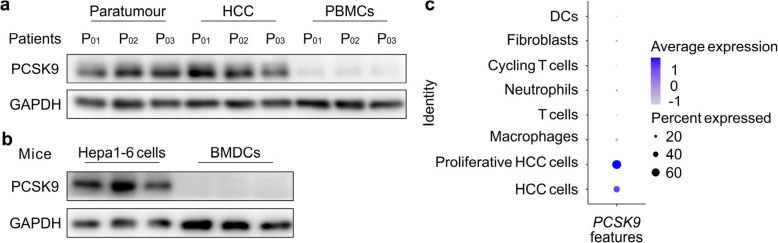

To verify whether PCSK9 knockdown can promote APC antigen presentation and the subsequent T cell priming without tumour bearing, primary dendritic cells (DCs) cultured from bone marrow (BMDCs) were treated with h-LNP or controls for 60 h. Flow cytometry analysis showed the H-2Kb level, antigen presentation efficiency and DC maturation were comparable between m-LNP and h-LNP treatment group (Supplementary Fig. 6a-d). In vivo study showed DC antigen presentation and T cell mobilization efficiency were parallel between m-LNP and h-LNP vaccination on healthy mice (Supplementary Fig. 7, 8). Since PCSK9 is primarily expressed in liver but not in immune organs or tissues, we speculate that no or low expression level of PCSK9 in APCs results in negligible effects of PCSK9 knockdown by siRNA on the DC antigen presentation and T cell priming. Consequently, PCSK9 protein levels in paratumour, tumour and peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from HCC patients were investigated through western-blotting. PCSK9 was either undetectable or present at very low levels in PBMCs, while high expression was observed in paratumoural and HCC tissues (Fig. 4a (Extended data of Fig. 1)). PCSK9 expression levels were also measured in mouse HCC cell line (Hepa1-6) and BMDCs. The result revealed that PCSK9 was not detected in BMDCs (Fig. 4b (Extended data of Fig. 1)). Furthermore, single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) analysis on subcutaneous HCC tumour samples from mice showed that PCSK9 primarily expressed in tumour cells but not in immune cells, such as neutrophils, T cells, macrophages and DCs (Fig. 4c (Extended data of Fig. 1)). These results indicate that introducing PCSK9 siRNA into mRNA vaccine could specifically improve tumour cell MHC-I level and thus promote its antigen presentation after intratumoural vaccination, which in turn enhance the efficacy of such mRNA vaccine on the priming of immune responses.

Fig. 4.

Distribution of PCSK9 expression. a PCSK9 expression in paratumour, tumour, and PBMCs from patients with HCC. b PCSK9 expression in mouse HCC cell line (Hepa1-6) and BMDCs. c PCSK9 expression profiling in tumour analyzed through sc-RNA seq (Extended data Fig. 1)

Fig. 5.

h-LNP treatment retards tumour growth. a Schematic illustrating the therapeutic strategy. b, c Kinetics of Hepa1-6-OVA tumour growth in h-LNP treatment group and controls. n = 10. d Hepa1-6-OVA tumour weight in different groups on day 13. n = 10. e Hepa1-6-OVA tumours dissected from each group after 13 days. f Kinetics of B16-OVA tumour growth in h-LNP treatment group and controls. n = 7. The P value in orange color refers to the comparison between si-LNP and m-LNP group. The P value in red color refers to the comparison between si-LNP and h-LNP group. g Kaplan–Meier plots of B16-OVA bearing mice survival for h-LNP treatment group and controls. n = 7. Data are presented as mean ± s.d. An unpaired Student’s t-test was performed for two-group comparison, while one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s HSD post hoc test was employed for comparisons among three or more groups. Survival analysis was performed via log-rank test. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. ***P < 0.001

The cooperation of PCSK9 siRNA strengthens mRNA vaccine anti-tumour therapy

To substantiate the capacity of PCSK9 siRNA in improving the anti-tumour effect of mRNA vaccine, we established an ectopic tumour model of HCC, which is known to have suppressive TME and immunotherapy resistance [35]. When tumour volume reached 100 mm3, h-LNP or controls were administrated through intratumoural injection on day 5 and day 9 (Fig. 5a). The results showed that treatment with PCSK9 siRNA or OVA mRNA mono-delivery acquired only modest inhibition effect on tumour growth. By contrast, h-LNP inhibited the tumour progress (Fig. 5b-e). The average tumour volume in si-LNP or m-LNP treatment group was threefold that of h-LNP treatment group, indicating PCSK9 siRNA in mRNA vaccine could potentiate treatment efficacy.

To gain deeper insight into the strength of the RNA regulated system over mRNA mono-delivery in cancer immunotherapy, melanoma model was developed with B16-OVA cell line. Mice were treated with h-LNPs or controls according to the same therapeutic strategy. Consistent with our and other previous studies [36, 37], mRNA vaccine could inhibit tumour growth and prolong the survival of tumour bearing mice. si-LNP also retarded tumour growth compared with PBS group. Nevertheless, h-LNP treatment achieved the most substantial inhibition compared to the controls. And 3 out of 7 mice got tumour free and survived over 60 days (Fig. 5f, g). The results indicate that the PCSK9 siRNA-assisted mRNA vaccine demonstrates enhanced therapeutic efficacy over the mRNA-only vaccine, regardless of whether it is applied to tumour types with poor immunotherapy responsiveness or those with a higher likelihood of responding to immunotherapy.

TME was analyzed to substantiate whether incorporation of PCSK9 siRNA could enhance the immunoregulation effect of mRNA vaccine. More CD45+ immune cells infiltrated in tumour tissue in h-LNP treatment group compared with other controls (Fig. 6a). si-LNP or m-LNP mono-delivery treatment induced minor increases in the percent of total T cells and CD8+ T cells, while h-LNP treatment resulted in pronounced accumulation of those sub-populations (Fig. 6b-d). The number of CD4+ T cells in tumour tissues was elevated after treatment with h-LNP compared to PBS group (Supplementary Fig. 9a). The ratio of intratumoural CD8+/CD4+ T cells in h-LNP group was more than fourfold that of PBS or si-LNP group, and over threefold that of m-LNP group (Supplementary Fig. 9b). A consistent trend in tumour infiltrating CD3+ T cells and their sub-populations after h-LNP treatment were also demonstrated by immunofluorescence and immunohistochemical sections (Fig. 6e, Supplementary Fig. 10). Subsequently, IFN-γ secreting CD8+ T cells were analyzed. Both of m-LNP and h-LNP induced a high level of IFN-γ+CD8+ T cells, with the percentage of IFN-γ+CD8+ T cells after h-LNP treatment being nearly twice that observed after m-LNP treatment, while PCSK9 siRNA single delivery induced negligible IFN-γ+CD8+ T cells in tumour, (Fig. 6f). To assess the formation of tertiary lymphoid structures (TLS) or immune cell aggregation, we performed H&E staining and immunofluorescence staining. The immunofluorescence staining included antibodies against CD45, CD4, CD8, and CD19. The entire slide from each group was scanned, and we carefully examined the aggregation of immune cells across the whole slide. The phenomenon of immune cells aggregation was observed by both of H&E staining and immunofluorescence staining among all four groups. However, no B cell aggregation was detected. Distinct features of immune cell clusters were observed among the four groups. Treatment with si-LNP, m-LNP, and h-LNP resulted in an increased number of immune cell clusters compared with the PBS group, with the most prominent expansion observed in the h-LNP group. Moreover, the proportion of CD8⁺ T cells within these clusters was significantly higher in the h-LNP group than in the si-LNP and m-LNP groups (Supplementary Fig. 11,12). These results indicate that the incorporation of PCSK9 siRNA into mRNA vaccine promotes the infiltration of immune cells into the solid tumour, and enhanced the anti-tumour efficacy of the mRNA vaccine.

Fig. 6.

h-LNP treatment reprograms immune microenvironment in tumour. Hepa1-6-OVA tumour bearing mice received h-LNP or controls through intratumoural injection when tumour volume reached ~ 100 mm3. Vaccination or controls was repeated 4 days after first treatment. Tumours were dissected and analyzed 4 days after second vaccination. n = 5. a-d Quantification of CD45+ cells (a), CD3+ T cells (b) in tumour tissue, CD4+ in T cells (c), CD8+ in T cells (d). e Representative IF images showing CD4+/CD8+ cells in tumours. f Representative plots from flow cytometry and statistical result indicating IFN-γ secreting CD8+ T cells. g scRNA-seq analysis identified immune sub-populations. Dot plots showing gene expression profiles across immune cell types was presented. h UMAP plot illustrating clustering of immune cell subsets. i, Ratio of immune cell sub-populations analyzed through scRNA-seq. j, Gene expression profiles associated with proliferation and cytotoxicity in T cells and NK cells. Data are presented as mean ± s.d. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s HSD post hoc test was employed for comparisons among three or more groups. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. ***P < 0.001

Immune death of tumour cells caused by CTLs can create an antigenic reservoir, which facilitates the recruitment of APCs for antigen processing and presentation and thus promotes further T cell activation and mobilization [38]. Hence, antigen presentation efficiency of APCs in TME was evaluated. The enhancement of antigen presentation in DCs and macrophages was observed following h-LNP treatment, in comparison to m-LNP treatment (Supplementary Fig. 13a, b).

The reprograming effect of h-LNP on TME was further demonstrated through immune cell analysis based on scRNA-seq. Live cells from Hepa1-6-OVA tumours were collected on day 4 after the second vaccination. Uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) was plotted according to marker genes identification. UMAP analysis identified twelve clusters from immune cells (Fig. 6g, h). Vaccination remodeled immune cell profile in TME, characterized by increased percent of CD8+ T cells, cycling T cells, DCs as well as NK cells, and decreased ratios of monocytes, neutrophils, and monocyte like macrophages (M-macrophages) (Fig. 6i). Particularly, h-LNP vaccination induced increased density of CD8+ T cells and reduced monocyte infiltration compared to m-LNP treatment. And h-LNP treatment reprograms CD8+ T cells from a minor subset in PBS group into a predominant population within the immune cell landscape (Fig. 6i). We subsequently analyzed the gene expression profiles associated with proliferation and cytotoxicity in NK cells and T cells. In NK cells, several proliferation markers, including Mki67, Tyms, Cks1b, and Gins2, as well as cytotoxicity-associated genes such as Gzmk, Tia1, Lamp1, Slamf7, Zap70, and Cd69, exhibited moderate upregulation in the h-LNP group relative to other groups. Both proliferation and cytotoxicity-related genes were upregulated in CD8+ T cells after h-LNP treatment compared to m-LNP or PBS treatment. However, for CD4+ T cells, the expression levels of these genes were generally lower across all treatments, with only minor upregulation observed in the h-LNP group (Fig. 6j).

Furthermore, three clusters of macrophages were identified, macrophages-1 that highly express H2-Eb1, H2-Ab1, H2-Aa, macrophages-2 that highly express C1qa, C1qb, Aif1, and M-macrophages with high expression of H2-Eb1, H-2Ab1, H2-Aa, Aif1. Notably, the ratio of macrophages-2 was upregulated after m-LNP treatment, whereas downregulated in h-LNP group compared with m-LNP group (Fig. 6i). To investigate the varying functions among macrophages-1 and −2, we examined their dynamic immune states and cellular transitions by inferring and modeling the trajectories of their state evolution. Pseudotime-ordered analysis demonstrated that monocytes occupied the initial phase of the trajectory, with monocyte-like macrophages distributed along the intermediate stages, whereas macrophages-1 and −2 predominantly aggregated at the terminal state (Fig. 7a,b (Extended data of Fig. 2). These results imply divergent functional roles for macrophages-1 and macrophages-2. Differentially expressed gene analysis exhibited an enrichment in genes participating in antigen presentation, T cell mobilization and response to type II interferon within macrophages-1, and an enrichment in genes associated with leukocyte/myeloid cell mobilization within macrophages-2 (Fig. 7c (Extended data of Fig. 2)). The M1 and M2 polarization scores on the population of macrophages-1 and macrophages-2 were calculated using related gene sets (Supplementary Table 2). We observed that macrophages-1 displayed an M1 phenotype, while macrophages-2 was characterized by an M2 phenotype (Fig. 7d, e (Extended data of Fig. 2)). We then analyzed the expression profile of TREM2 in related cells. TREM2 were mainly expressed in the population of macrophage-2 (Fig. 8a (Extended data of Fig. 3)). Both m-LNP and h-LNP treatments increased the infiltration of TREM2+ macrophages compared to PBS treatment. However, the frequency of TREM2+ macrophages in h-LNP was lower than that in m-LNP group (Fig. 8b (Extended data of Fig. 3)). These results indicate that h-LNP treatment promoted the differentiation of infiltrating monocytes in the TME into the M1-like phenotype, rather than the M2-like phenotype which is typically associated with the suppression of T cell functions [39–41].

Fig. 7.

Differentiation trajectories and function analysis on the populations of macrophages-1 and macrophages-2 identified by scRNA-seq. a, b Pseudotime-ordered analysis on monocytes, monocyte-like macrophages, macrophages-1 and macrophages-2. c The differences in the functions of macrophages-1 and macrophages-2 detected by differentially expressed gene (DEG) analysis. d M1 scores for macrophages-1 and macrophages-2 cells. e M2 scores for macrophages-1 and macrophages-2 cells. Statistical significance was calculated through an unpaired student’s t test. ***P < 0.001 (Extended data of Fig. 2)

Fig. 8.

TREM2 expression analyzed by scRNA-seq. a TREM2 expression levels in monocyte/macrophages. b TREM2 expression levels among different groups

Hybrid nucleic acid vaccine prolongs the survival of in-situ HCC bearing mice

To further substantiate the therapeutic promise of the RNA-regulated system in HCC, an orthotopic HCC model was established via intrahepatic injection of the Hepa1-6-OVA cell line. h-LNP or controls were intravenously injected twice on day 3 and day 7 (Fig. 9a). Positron Emission Tomography-Computed Tomography (PET-CT) scanning was randomly performed on 3 out of 10 mice bearing orthotopic HCC tumours. Both PET-CT imaging and quantitative analysis demonstrated that h-LNP treatment inhibited tumour growth (Fig. 9b, Supplementary Fig. 14a, b). Survival monitoring showed that the lifespan of mice in h-LNP treatment was prolonged compared with mice receiving m-LNP treatment or other controls (Fig. 9c). Body weight did not obviously change throughout the process of the treatments (Fig. 9d). Consistent with the findings from ectopic tumours, the antigen presentation efficiency of tumour cells derived from orthotopic tumours was enhanced following h-LNP treatment (Fig. 9e). Compared with the controls, h-LNP treatment elicited more CD8+ T cells accumulating into TME (Fig. 9f-h). Furthermore, we examined the cytotoxic CD8+ T cells in TME through flow cytometry. h-LNP treatment induced increment of IFN-γ+CD8+ T cells (Fig. 9i). We then evaluated whether si-LNP could enhance the efficacy of anti-PD-1 therapy in both melanoma mouse model (highly immunogenic tumors) and HCC mouse model (weakly immunogenic tumors). The results showed either si-LNP or anti-PD-1 antibodies could inhibit tumour growth in both melanoma and HCC mouse models. Of note, the combination therapy of si-LNP and anti-PD-1 lead to the lowest tumour growth among all four groups (Supplementary Fig. 15, 16). The data imply that intravenous injection of h-LNP can edit liver orthotopic tumour cells, promote tumour cell antigen presentation, relieve suppressive microenvironment, and enhance anti-tumour immune responses. si-LNP treatment could sensitize anti-PD-1 immunotherapy in both highly and weakly immunogenic tumours.

Fig. 9.

h-LNP treatment induces anti-tumour response and prolongs orthotopic tumour bearing mice survival. a Schematic illustrating the therapeutic strategy. b PET-CT for orthotopic tumour bearing mice in different groups 8 days after tumour inoculation. c Kaplan–Meier plots of orthotopic Hepa1-6-OVA tumour bearing mice survival for h-LNP treatment group and controls. n = 8. d Body weight of mice after treatment. n = 8. e–g Quantification of SIINFEKL-H-2Kb+ in Hepa1-6-OVA cells (e), CD4+ in T cells (f), and CD8+ in T cells (g), n = 5. h Flow cytometry analysis showing the ratio of CD8+ T cells to CD4+ T cells, n = 5. i Flow cytometry analysis showing IFN-γ+ secreting CD8+ T cells. n = 5. Data are presented as mean ± s.d. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s HSD post hoc test was employed for comparisons among three or more groups. Survival analysis was performed via log-rank test. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. ***P < 0.001

Discussion

Primary liver cancer is the third leading cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide, with common etiologies including viral infections (HBV and HCV), alcoholic liver disease, and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease [42]. It has been shown that the infiltration landscape of immune cells varies among different aetiologies [43]. More importantly, the loss of MHC-I gene expression in tumour cells is a common phenomenon accompanying tumour development [44, 45]. Data from The Cancer Genome Atlas suggest that HLA-I expression is positively correlated with patient overall survival in multiple cancer types [46, 47]. The responders to anti-PD-1 immunotherapy exhibited higher levels of HLA-I than non-responders [48]. Although pre-clinical studies have discovered other immune-mediated tumour killing pathways regarding to MHC-I negative tumours [34, 49, 50], MHC-I deficiency tends to cause the immune desertification of TME and results in faster tumour growth [34]. Antigen presentation disorder in tumour cells could lead to the resistance of mRNA vaccine therapy [34]. In this study, we investigated the expression levels of HLA-ABC in HCC tissues and paratumoural tissues. The results showed that the expression levels of HLA-ABC were significantly lower in HCC tissues compared to paratumoural tissues, although no significant differences were found among different aetiologies. We substantiated PCSK9 knockdown could elevate MHC-I level and restored antigen presentation in HCC. Hence, an RNA regulated system that contained antigen mRNA and PCSK9 siRNA molecules to simultaneously activate immune responses and upregulate tumour cell antigen presentation was designed. A self-developed fluorinated LNP was used as the delivery vehicle, efficiently directing nucleic acids primarily to the liver. This unique property makes the RNA-regulated system particularly suitable for HCC treatment. Among various MHC-I regulators, PCSK9 is the only one that significantly correlates with the prognosis of HCC patients. Moreover, PCSK9 is predominantly expressed in the liver, including in HCC tissues, which makes its regulatory effect selectively impact tumour cells rather than immune cells.

In vitro investigations showed that tumour cell antigen presentation could be maximized after treatment with h-LNP compared to controls. In vivo, intratumoural injection which has been utilized in clinical trials involving mRNA vaccines facilitates the accessibility of LNP particles to tumour cells [51–54]. Consequently, the PCSK9 siRNA molecules encapsulated within the LNPs can effectively exert their biological function, elevating the levels of epitope presented by MHC-I on tumour cell surface. The efficacy study demonstrated that h-LNP vaccine possessed more potent cancer killing activity compared with m-LNP vaccine. Besides, we performed flow cytometry and scRNA-seq to characterize the immune microenvironment following vaccination. Compared with mRNA mono-delivery, our RNA regulated system displayed better remodeling effect, such as increased percent of CD8+ T cells, improved cytotoxic gene expression and proliferative potential in NK cells and CD8+ T cells. Additionally, prior studies have indicated that M2-phenotype macrophages in TME are pro-tumour and could suppress T cell functions [40, 41, 55]. In this study, a reduced frequency of M2-phenotype macrophage infiltration was observed following h-LNP vaccination compared to m-LNP treatment. Furthermore, intravenous administration of this RNA regulated system inhibited tumour growth and prolonged survival in an orthotopic mouse HCC model. Accordingly, the results validate that synergistically downregulating PCSK9 to improve tumour cell antigen presentation contributes to receding tumour resistance to mRNA vaccine therapy, hopefully accelerating the clinical translation of mRNA vaccine.

Conclusions

This study successfully engineered a dual-functional RNA-regulated system, utilizing a fluorinated LNP as the delivery vehicle to encapsulate PCSK9 siRNA and antigen-encoding mRNA. This RNA vaccine platform enhances tumour cell antigen presentation by silencing PCSK9 and reconfigures the immune landscape within the TME towards an immune-responsive milieu, thereby potentiating the anti-tumour efficacy of the mRNA vaccine.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos 82171757, 82241215, 82201960, 82402078), the Natural Science Foundation of Zhejiang Province (LZ22H030004), the National Key R&D Program of China (2021YFA0909900), the "Pioneer" and "Leading Goose" R&D Program of Zhejiang (2024C03168), the Starry Night Science Fund at Shanghai Institute for Advanced Study of Zhejiang University (SN-ZJU-SIAS-009), and the grants from the Startup Package of Zhejiang University.

Abbreviations

- CTL

Cytotoxic T lymphocytes

- HCC

Hepatocellular carcinoma

- HLA

Human leukocyte antigen

- ICI

Immune checkpoint inhibitors

- LNP

Lipid nanoparticles

- MHC-I

MHC-class-I

- ORR

Objective response rate

- SiRNA

Small interfering RNA

- PCSK9

Proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9

- TCR

T cell receptors

- TME

Tumour microenvironment

Authors’ contributions

H.L., Q.L., C.M., and H.Z. conceived and designed the study. Q.L. and S.Z. recruited patients and provided supports for clinical investigations. C.M., H.Z., X.Y., and G.K. performed the experiments and collected and analyzed the data. X.Z, B.W., Y.X., Q.W., K.Z., and J.C. provided supports for in vivo experiments. H.Q. and C.M analyzed the scRNA seq. data. J.C. provided supports for scRNA seq. analysis. H.Z. and C.M. drew and arranged figures. C.M., H.Z., X.Y., and G.K. prepared manuscript. H.L., Q.L., Z.G., and C.M. revised the manuscript. X.L. and H.F. provided assistance with supplementary experiments, manuscript revision, and proofreading. All the authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study adhered to the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki and received approval from the Clinical Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine (2022–161). All animal studies followed the protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at The First Affiliated Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine (2023–536). Every procedure complied the ethical regulations.

Consent for publication

All authors consent to the publication.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Chaoyang Meng, Huipeng Zhang, Xuewen Yi, Gangcheng Kong contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Hongjun Li, Email: hongjun@zju.edu.cn.

Qi Ling, Email: lingqi@zju.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Khan AA, Liu ZK, Xu X. Recent advances in immunotherapy for hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2021;20:511–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reig M, et al. BCLC strategy for prognosis prediction and treatment recommendation: the 2022 update. J Hepatol. 2022;76:681–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li Z, et al. Analysis of efficacy and safety for the combination of regorafenib and PD-1 inhibitor in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a real-world clinical study. iLIVER. 2024;3:100092. 10.1016/j.iliver.2024.100092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lyon AR, Yousaf N, Battisti NML, Moslehi J, Larkin J. Immune checkpoint inhibitors and cardiovascular toxicity. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19:e447–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee MS, et al. Atezolizumab with or without bevacizumab in unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma (GO30140): an open-label, multicentre, phase 1b study. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:808–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Butterfield LH, Najjar YG. Immunotherapy combination approaches: mechanisms, biomarkers and clinical observations. Nat Rev Immunol. 2024;24:399–416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pinter M, Scheiner B, Pinato DJ. Immune checkpoint inhibitors in hepatocellular carcinoma: emerging challenges in clinical practice. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;8:760–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sahin U, et al. An RNA vaccine drives immunity in checkpoint-inhibitor-treated melanoma. Nature. 2020;585:107–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rojas LA, et al. Personalized RNA neoantigen vaccines stimulate T cells in pancreatic cancer. Nature. 2023;618:144–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haslam A, Gill J, Prasad V. Estimation of the percentage of US patients with cancer who are eligible for immune checkpoint inhibitor drugs. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e200423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Finn RS, et al. Atezolizumab plus bevacizumab in unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1894–905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Robert C, et al. Nivolumab in previously untreated melanoma without BRAF mutation. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:320–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.D’Angelo SP, et al. Efficacy and safety of Nivolumab alone or in combination with Ipilimumab in patients with mucosal melanoma: a pooled analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:226–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Patel SJ, et al. Identification of essential genes for cancer immunotherapy. Nature. 2017;548:537–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu D, et al. Integrative molecular and clinical modeling of clinical outcomes to PD1 blockade in patients with metastatic melanoma. Nat Med. 2019;25:1916–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garrido F, Aptsiauri N, Doorduijn EM, Garcia Lora AM, van Hall T. The urgent need to recover MHC class I in cancers for effective immunotherapy. Curr Opin Immunol. 2016;39:44–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wu X, et al. Targeting MHC-I molecules for cancer: function, mechanism, and therapeutic prospects. Mol Cancer. 2023;22:194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Deng Y, et al. Glucocorticoid receptor regulates PD-L1 and MHC-I in pancreatic cancer cells to promote immune evasion and immunotherapy resistance. Nat Commun. 2021;12:7041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gu SS, et al. Therapeutically increasing MHC-I expression potentiates immune checkpoint blockade. Cancer Discov. 2021;11:1524–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen X, et al. A membrane-associated MHC-I inhibitory axis for cancer immune evasion. Cell. 2023;186:3903-3920 e3921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sharma P, Hu-Lieskovan S, Wargo JA, Ribas A. Primary, adaptive, and acquired resistance to cancer immunotherapy. Cell. 2017;168:707–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vesely MD, Zhang T, Chen L. Resistance mechanisms to anti-PD cancer immunotherapy. Annu Rev Immunol. 2022;40:45–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rosenthal R, et al. Neoantigen-directed immune escape in lung cancer evolution. Nature. 2019;567:479–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Anagnostou V, et al. Evolution of neoantigen landscape during immune checkpoint blockade in non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Discov. 2017;7:264–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Samstein RM, et al. Tumor mutational load predicts survival after immunotherapy across multiple cancer types. Nat Genet. 2019;51:202–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rizvi NA, et al. Cancer immunology. Mutational landscape determines sensitivity to PD-1 blockade in non-small cell lung cancer. Science. 2015;348:124–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McGranahan N, et al. Clonal neoantigens elicit T cell immunoreactivity and sensitivity to immune checkpoint blockade. Science. 2016;351:1463–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang H, et al. Fluorinated lipid nanoparticles for enhancing mRNA delivery efficiency. ACS Nano. 2024;18:7825–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Seidah NG, Prat A. The multifaceted biology of PCSK9. Endocr Rev. 2022;43:558–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu X, et al. Inhibition of PCSK9 potentiates immune checkpoint therapy for cancer. Nature. 2020;588:693–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bruix J, Reig M, Sherman M. Evidence-based diagnosis, staging, and treatment of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:835–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Eisenhauer EA, et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:228–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schindelin J, et al. Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat Methods. 2012;9:676–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Beck JD, et al. Long-lasting mRNA-encoded interleukin-2 restores CD8(+) T cell neoantigen immunity in MHC class I-deficient cancers. Cancer Cell. 2024;42:568-582 e511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Llovet JM, et al. Immunotherapies for hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2022;19:151–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Meng C, et al. Virus-mimic mrna vaccine for cancer treatment. Adv Ther. 2021;4:2100144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Miao L, et al. Delivery of mRNA vaccines with heterocyclic lipids increases anti-tumor efficacy by STING-mediated immune cell activation. Nat Biotechnol. 2019;37:1174–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jhunjhunwala S, Hammer C, Delamarre L. Antigen presentation in cancer: insights into tumour immunogenicity and immune evasion. Nat Rev Cancer. 2021;21:298–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gao J, Liu W-R, Tang Z, Fan J, Shi Y-H. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells in cancer. iLIVER. 2022;1:81–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Noy R, Pollard JW. Tumor-associated macrophages: from mechanisms to therapy. Immunity. 2014;41:49–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen S, et al. Macrophages in immunoregulation and therapeutics. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2023;8:207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines on the management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2025;82:315–374. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 43.Li M, et al. Spatial proteomics of immune microenvironment in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis-associated hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2024;79:560–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Aptsiauri N, Ruiz-Cabello F, Garrido F. The transition from HLA-I positive to HLA-I negative primary tumors: the road to escape from T-cell responses. Curr Opin Immunol. 2018;51:123–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dong LQ, et al. Heterogeneous immunogenomic features and distinct escape mechanisms in multifocal hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2020;72:896–908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schaafsma E, Fugle CM, Wang X, Cheng C. Pan-cancer association of HLA gene expression with cancer prognosis and immunotherapy efficacy. Br J Cancer. 2021;125:422–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fang S, et al. Multiple immunomodulatory strategies based on targeted regulation of proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 and immune homeostasis against hepatocellular carcinoma. ACS Nano. 2024;18:8811–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hong JY, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma patients with high circulating cytotoxic T cells and intra-tumoral immune signature benefit from pembrolizumab: results from a single-arm phase 2 trial. Genome Med. 2022;14:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Badrinath S, et al. A vaccine targeting resistant tumours by dual T cell plus NK cell attack. Nature. 2022;606:992–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lerner EC, et al. CD8(+) T cells maintain killing of MHC-I-negative tumor cells through the NKG2D-NKG2DL axis. Nat Cancer. 2023;4:1258–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Miao L, Zhang Y, Huang L. mRNA vaccine for cancer immunotherapy. Mol Cancer. 2021;20:41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kon E, Ad-El N, Hazan-Halevy I, Stotsky-Oterin L, Peer D. Targeting cancer with mRNA-lipid nanoparticles: key considerations and future prospects. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2023;20:739–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shi L, Yang J, Nie Y, Huang Y, Gu H. Hybrid mRNA nano vaccine potentiates antigenic peptide presentation and dendritic cell maturation for effective cancer vaccine therapy and enhances response to immune checkpoint blockade. Adv Healthc Mater. 2023;12:e2301261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bitounis D, Jacquinet E, Rogers MA, Amiji MM. Strategies to reduce the risks of mRNA drug and vaccine toxicity. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2024;23:281–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhu Y, Qin LX. Strategies for improving the efficacy of immunotherapy in hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2022;21:420–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.