Abstract

The major facilitator superfamily (MFS) represents the largest collection of evolutionarily related members within the class of membrane ‘carrier’ proteins. OxlT, a representative example of the MFS, is an oxalate-transporting membrane protein in Oxalobacter formigenes. From an electron crystallographic analysis of two-dimensional crystals of OxlT, we have determined the projection structure of this membrane transporter. The projection map at 6 Å resolution indicates the presence of 12 transmembrane helices in each monomer of OxlT, with one set of six helices related to the other set by an approximate internal two-fold axis. The projection map reveals the existence of a central cavity, which we propose to be part of the pathway of oxalate transport. By combining information from the projection map with related biochemical data, we present probable models for the architectural arrangement of transmembrane helices in this protein superfamily.

Keywords: electron cryo-microscopy/major facilitator superfamily/membrane transporter/two-dimensional crystallization

Introduction

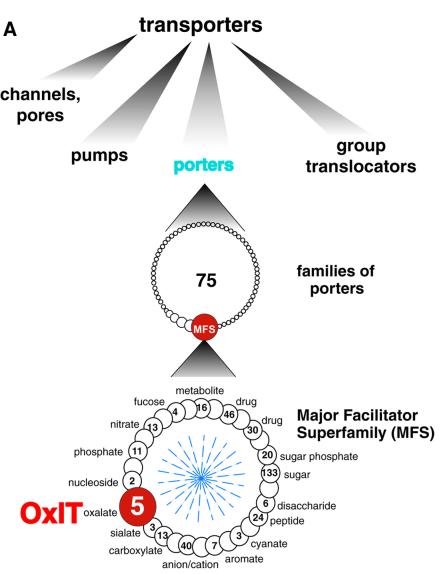

Analysis of several prokaryotic and eukaryotic genomes shows that transport proteins represent a large fraction (∼30%) of all integral membrane proteins (Paulsen et al., 1998, 2000). Of the four recognized classes of transporters, those classified as ‘facilitators’ or ‘carriers’ mediate the reactions of uniport, symport or antiport (Figure 1A), and within this class, a single group, the major facilitator superfamily (MFS), encompasses the largest number of evolutionarily related examples. Individual members of the MFS function in settings that range from the accumulation of nutrients by bacteria to the cycling of neurotransmitters across synaptic membranes in humans, but it is believed that all members share a common structural basis. Indirect arguments suggest that most MFS proteins, e.g. the lactose permease (LacY) or the glucose transporter (GLUT1), contain 12 transmembrane α-helices, a structural theme found in many other transport systems, including those within the ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter superfamily. It is also thought that in both the MFS and ABC superfamilies, which together account for about half of all known transporters, the N-terminal set of six helices is related evolutionarily to the C-terminal set of six helices, although sequence similarities in any individual example may not yet be readily apparent (Henderson and Maiden, 1990; Saurin and Dassa, 1994). Atomic resolution structures are not yet available for any of these putative 12-helix transporter proteins.

Fig. 1. Classification and secondary structure of OxlT. (A) Classification of transport systems. Proteins and peptides catalyzing transport across biological membranes are displayed using the classification by Paulsen et al. (2000) (http://www.biology.ucsd.edu/∼ipaulsen/transport/ and http://www-biology.ucsd.edu/∼msaier/transport/). Top: classes of transporters. Four classes of transporting entities are indicated. Within the class of ‘channels and pores’ there are β-barrel pores, α-helix type channels, pore-forming toxins, and non-ribosomally synthesized channels. Group translocators are represented by the bacterial phosphotransferase systems. There are five distinct kinds of pumps, including those driven by phosphate bond hydrolysis, decarboxylation, methyl transfer, oxidoreduction, and light absorption. The class of ‘porters’ includes non-ribosomally synthesized porters and the proteins, discussed here, that mediate uniport, symport and antiport. Middle: families of porters. Within the class of porters, there are 75 recognized families or superfamilies. The largest of these subdivisions is the MFS. Bottom: the MFS. The MFS gathers together 29 families, shown as circles, whose collective membership is several thousand. For families in which annotation has been reported (Paulsen et al., 2000), the number of family members is given within the circle and substrate specificity is indicated at the perimeter. Families not annotated are shown as open circles. (B) A secondary structure model for OxlT. The OxlT amino acid sequence is given using the single-letter code; the sequence also includes theC-terminal nine-residue poly-histidine tag used to facilitate affinity purification. Shaded boxes represent the approximate boundaries of the predicted transmembrane segments (1–12) (Ye et al., 2001). Blue or red highlights are used to specify positive (H, K, R) or negative (D, E) residues, respectively; polar residues are shown in open circles. Lysine-355 (transmembrane segment 11), which may reside on the path of oxalate transport (Fu and Maloney, 1998; Fu et al., 2001), is enlarged for emphasis.

OxlT, a representative member of the MFS, is a 44 kDa protein (Figure 1B) found in the cytoplasmic membrane of the Gram-negative anaerobic bacterium Oxalobacter formigenes. OxlT functions as an antiporter, transporting divalent oxalate into the cell in exchange for monovalent formate generated by an internal oxalyl decarboxylase. In this way, OxlT effectively operates as a proton pump to generate the proton-motive force that drives ATP synthesis (Anantharam et al., 1989). Thus, OxlT occupies a central role in the physiology of O.formigenes.

Results and discussion

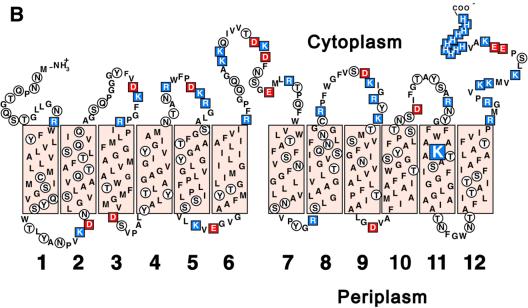

To investigate the structure of OxlT, we purified the protein (Ruan et al., 1992; Fu and Maloney, 1997) and prepared two-dimensional vesicular crystals by dialysis of lipid-detergent micelles (Figure 2A). The majority of crystals were tubular, with typical widths of ∼0.7 µm and lengths ranging from 1–4 µm. Upon deposition on a continuous carbon film, the tubes became flattened into two layers of well preserved two-dimensional crystals. Computed diffraction patterns from the best images recorded at liquid nitrogen temperatures displayed measurable reflections to 5 Å resolution (Figure 2B, Table I).

Fig. 2. Two-dimensional crystals of OxlT and their analysis. (A) Electron micrograph of OxlT crystals embedded in 1% uranyl acetate. Scale bar = 1.0 µm. (B) Image-quality-plot (IQ) of a single image recorded at liquid nitrogen temperature from a trehalose-embedded specimen. Each spot in the transform is represented by a square and a number (IQ value; Henderson et al., 1986) indicating the signal to noise ratio. Larger boxes and smaller IQ values reflect higher quality spots. The concentric circles show resolutions (20, 8 and 6 Å) at the indicated distances.

Table I. Electron crystallographic statistics.

| Two-sided plane group symmetry | p22121 |

| Unit cell dimensions | a = 100.3 ± 0.9 Å |

| b = 79.0 ± 0.6 Å | |

| γ = 90° | |

| No. of images | 4 |

| Resolution limit used | 6 Å |

| Total no. of observed reflections (IQ <6) | 823 |

| No. of unique reflections | 169 |

| Overall phase residual (random = 45°) | 14.0° |

| Resolution range (Å) | No. of unique reflections | Completeness (%) | Phase residual (random = 45°) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 110.0–15.8 | 24 | 100.0 | 8.6 |

| 15.8–11.2 | 25 | 100.0 | 4.6 |

| 11.2–9.1 | 24 | 100.0 | 9.1 |

| 9.1–7.9 | 25 | 100.0 | 10.8 |

| 7.9–7.1 | 26 | 100.0 | 15.5 |

| 7.1–6.5 | 24 | 96.0 | 29.4 |

| 6.5–6.0 | 23 | 95.8 | 20.9 |

| 6.0–5.6 | 16 | 64.0 | 32.3 |

| 5.6–5.3 | 15 | 65.2 | 46.7 |

| 5.3–5.0 | 15 | 53.6 | 46.2 |

Phase residual was determined using reflections with IQ <6.

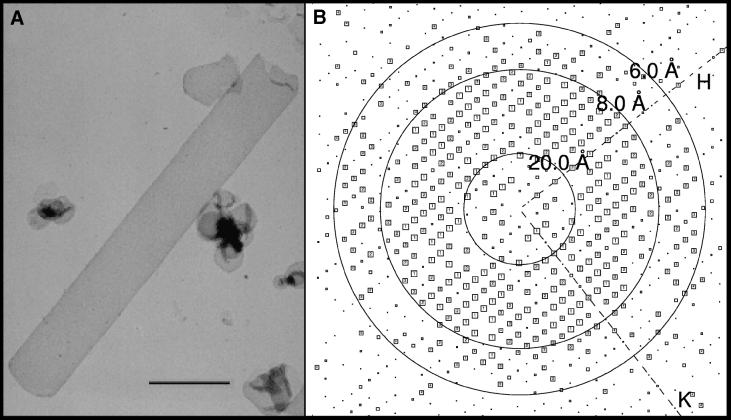

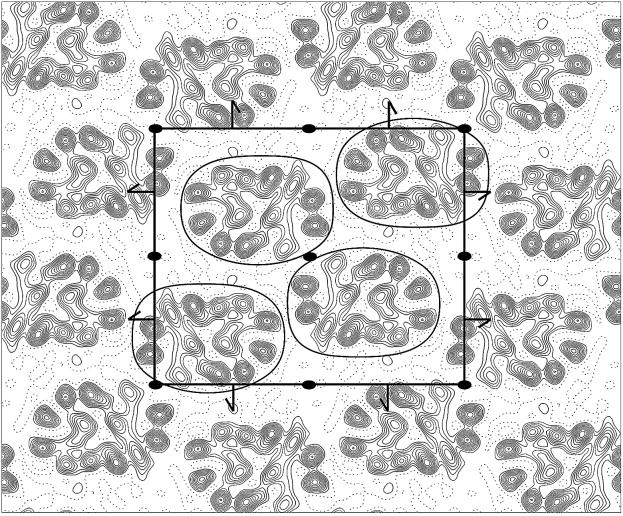

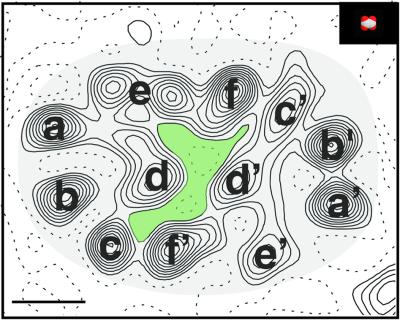

A projection density map of OxlT, calculated by merging the data from four images, is shown in Figure 3. The unit cell, which contains four molecules of OxlT, has dimensions of 100.3 × 79 Å and displays p22121 planar symmetry. The overall shape of the monomer is oval, with approximate projection dimensions of 48 Å and 32 Å. The molecule displays a central cavity, which we believe must be associated with the pathway of substrate transport. We have annotated the density map by assigning 12 features labeled a–f and a′–f′ (Figure 4). This assignment takes into account the striking presence of an approximate internal two-fold axis at the center of each molecule, relating regions marked a–f with corresponding regions a′–f′, respectively. The choice of letters is arbitrary. We propose that regions a, a′, b, b′ and c, which are the most clearly resolved features in the map, represent transmembrane α-helices that are nearly perpendicular to the plane of the membrane. The density in region c′ is elongated in one direction, consistent with that expected from a transmembrane α-helix that is tilted in the direction of the elongation. In contrast, the densities in regions marked d, e and f, and the corresponding set of d′, e′ and f′ are not well separated. An initial inspection of the d, e and f region suggests the presence of four peaks. However, careful examination of the intensities, spacing and area covered by these four peaks suggests that they are more likely to correspond to the densities arising from three, rather than four transmembrane α-helices. Similarly, we conclude that the densities in the regions marked d′, e′ and f′ also represent the contributions of three transmembrane α-helices.

Fig. 3. Projection density map of OxlT at 6 Å resolution. The contour map was calculated using merged data collected from four crystals (two frozen-hydrated and two trehalose-embedded specimens), and with p22121 symmetry imposed. These four images were averaged together because no significant differences in phase residuals were observed between images recorded from either frozen-hydrated or trehalose-embedded specimens. The boxed area represents a unit cell with dimensions of 100.3 × 79 Å. The two-fold axes perpendicular to the membrane plane and the screw axes parallel to the membrane plane are indicated. Negative and positive contours are shown as solid and dotted lines, respectively. Each unit cell contains four molecules of OxlT monomers; the approximate molecular boundary of each monomer is highlighted. The average area per transmembrane segment in these crystals is ∼165 Å2. This compares favorably with the corresponding value of 161 Å2 observed in the closely packed hexagonal lattice of two-dimensional crystals of bacteriorhodopsin (Henderson et al., 1986).

Fig. 4. Annotation of OxlT density map. A monomer of OxlT is shown, with the approximate molecular boundary highlighted. Regions labeled a–f and a′–f′ each indicate densities likely to correspond to six transmembrane α-helices of OxlT (see text). The scale bar is equivalent to 10 Å. The inset shows a space-filling representation of the divalent oxalate anion on the same scale. The projection map suggests the existence of a central cavity, colored in light green, located at the boundary between two sets of six helices.

Based on the above arguments we therefore propose that OxlT contains 12 transmembrane α-helices. Some of these α-helices (regions a, a′, b, b′ and c) seem to be closely aligned to the membrane normal. Those in regions marked c′ and d′ appear to be significantly tilted. The projection densities corresponding to the remaining five α-helices are less well separated and could originate from the presence of tilted or kinked α-helices. It is also possible that ordered extramembranous loops contribute to the projection density. We note that our assignment of 12 membrane-spanning α-helices for OxlT is consistent with the finding of an approximate two-fold symmetry axis in the molecule, which argues against the presence of an odd number of helices. Furthermore, topological studies with OxlT based on identifying the locations of engineered cysteine residues (Ye et al., 2001) also independently suggest the presence of 12 transmembrane helices. Our helix assignment implies that residues contributed from seven helices line the substrate transport pathway (Figure 4).

A question of central interest is whether transmembrane segments identified in the secondary structure of OxlT (Figure 1B) can be mapped onto the densities found in the projection map in order to derive a structural model for MFS proteins. Because this correlation cannot be deduced from the projection map alone, we have addressed the issue by combining this information with the extensive body of biochemical data on proteins in the MFS. Two kinds of constraints were imposed. First, we used results from a sequence analysis of proteins within the MFS, which shows there is homology between the first six and last six helices (Henderson and Maiden, 1990). This idea is strongly supported by the internal two-fold symmetry observed in the projection map of the OxlT monomer. Secondly, relying mainly on the extensive work of Kaback and co-workers on LacY, another member of the MFS, we constructed a database listing all pairs of transmembrane α-helices proposed to be neighbors. In doing so, we reasoned that helix associations deduced on the basis of engineered disulfide cross-links were likely to be the most stringent, and therefore used only these findings in our analysis. These helix pairs are: 1 and 7 (Wu and Kaback, 1996); 1 and 11 (Wang and Kaback, 1999b); 7 and 10 (King et al., 1991); 2 and 7 (Wu and Kaback, 1996); 2 and 11 (Wu et al., 1998); 4 and 5 (Wolin and Kaback, 2000); 3 and 7 (Wang and Kaback, 1999a); and 1 and 12 (Wang and Kaback, 1999b).

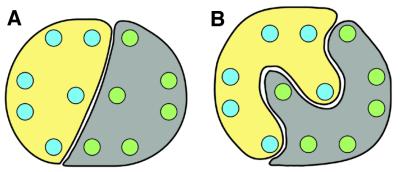

If we assume that the tertiary structures of LacY and OxlT are similar (Paulsen et al., 2000), it follows that helices 1 and 7 must be represented in the two densities marked d and d′ in Figure 4, since these are the only two regions in the map that are both related by two-fold symmetry and close enough to form an engineered disulfide bond. This line of reasoning significantly reduces the range of possible architectures for OxlT. Two representative classes of model consistent with these findings are shown in Figure 5. In the model in Figure 5A, the two halves of OxlT interact via a smooth interface, while in Figure 5B, the two halves of the protein interact as interlocking C-shaped entities. Other models involving either straight or interdigitated interfaces can be envisioned, but further structural data are required to unambiguously distinguish these possibilities.

Fig. 5. Two arrangements for the architecture of OxlT. The interface between the two halves of the protein is either flat, as in (A), or interdigitated, as in (B). These arrangements are obtained by constraining the two symmetry-related central regions (marked d and d′ in Figure 4) such that they belong to separate halves of the protein (see text). The filled circles are intended to represent idealized transmembrane α-helices. The location of the helices reflects a putative two-fold symmetry solely for the purpose of illustrating possible models of the overall architecture.

There is no obvious resemblance between the structure of OxlT and the structures, also derived from electron crystallographic studies, reported for NhaA, the sodium proton antiporter (Williams, 2000), and EmrE, a bacterial multidrug antiporter (Tate et al., 2001). Neither of these proteins belongs to the MFS. Although NhaA does have 12 transmembrane helices, the structural analysis shows no evidence of the internal two-fold axis observed in OxlT. Three-dimensional or projection structures at resolutions sufficient to discern transmembrane segments are not yet available for any member of the ABC transporter superfamily, although a 22 Å projection map has been reported recently (Rosenberg et al., 2001). In this superfamily, as in the MFS, there is strong evidence for homology between the first six and last six transmembrane segments (Saurin and Dassa, 1994). An interesting possibility is that the helix packing arrangements in the MFS and ABC transporters may share common themes, and this should become clearer when atomic resolution models are available for these proteins.

Materials and methods

Overexpression and purification

OxlT expressed in Escherichia coli as a C-terminally His9-tagged polypeptide (Figure 1B) was solubilized and adsorbed to Ni2+-NTA (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) at 4°C for 12 h (Ruan et al., 1992, Fu and Maloney, 1997). The column was washed at 23°C with 100 volumes of a buffer (pH 7) containing 200 mM NaF, 50 mM imidazole, 20 mM MOPS/K, 10 mM potassium oxalate, 6 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 20% glycerol and 1% 1,2-diheptanoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DHPC) (Avanti Polar Lipids, Alabaster, AL). Purified (≥95%) OxlT was eluted at 23°C at ∼1–2 mg/ml on addition of a solution containing 100 mM potassium oxalate, 50 mM potassium acetate, 6 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 20% glycerol and 0.25% DHPC pH 4.5.

Two-dimensional crystallization of OxlT

OxlT was crystallized by dialysis from solutions containing purified protein (above), 0.3% n-cyclohexyl-heptyl-β-d-maltoside (Anatrace, Maumee, OH) and 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (Avanti Polar Lipids), at lipid-to-protein ratios of 0.2–0.4 (w/w). ‘Slide-a-lyzers’ (Pierce, Rockford, IL) were loaded with 100 µl aliquots of this mixture and dialyzed for 3 days (with three buffer changes) at 27°C against a solution containing 50 mM potassium acetate, 100 mM potassium oxalate, 20% glycerol and 6 mM β-mercaptoethanol pH 4.5.

Electron microscopy and image processing

Crystals deposited on continuous carbon film-containing grids were prepared for microscopy by negative staining with 1% uranyl acetate or by embedding in 3.5% trehalose (Hirai et al., 1999), or as frozen-hydrated specimens. Images were recorded using a Tecnai12 electron microscope (FEI Corp., OR) operating at 120 kV, equipped with a tungsten filament and a 626 single-tilt cryo-transfer system (Gatan, Pleasanton, CA), at a magnification of 52 000× and with measured specimen temperatures between –173 and –175°C. Specimens were imaged under low-dose conditions (∼10 electrons per Å2) using SO-163 electron image film (Eastman Kodak, Rochester, NY). The exposed films were developed for 12 min in full-strength D19 developer. The best images were selected by optical diffraction. Well ordered areas (∼1.4 µm2) were scanned and digitized using a Zeiss SCAI scanner (Z/I Imaging, Huntsville, AL). The MRC image processing package (Crowther et al., 1996) was used to process the digitized images and to construct a projection density map. The plane group symmetry was determined using ALLSPACE (Valpuesta et al., 1994), and image amplitudes were scaled with SCALIMAMP3D (Schertler et al., 1993) using bacteriorhodopsin electron diffraction amplitudes as a reference.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge many helpful discussions with Drs M.Kessel and P.Zhang. This work was supported by grants from the NCI intramural program (to S.S.) and Grant 9986617 from the National Science Foundation (to P.C.M.).

References

- Anantharam V., Allison,M.J. and Maloney,P.C. (1989) Oxalate:formate exchange. The basis for energy coupling in Oxalobacter. J. Biol. Chem., 264, 7244–7250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowther R.A., Henderson,R. and Smith,J.M. (1996) MRC image processing programs. J. Struct. Biol., 116, 9–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu D. and Maloney,P.C. (1997) Evaluation of secondary structure of OxlT, the oxalate transporter of Oxalobacter formigenes, by circular dichroism spectroscopy. J. Biol. Chem., 272, 2129–2135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu D. and Maloney,P.C. (1998) Structure–function relationships in OxlT, the oxalate/formate transporter of Oxalobacter formigenes. Topological features of transmembrane helix 11 as visualized by site-directed fluorescent labeling. J. Biol. Chem., 273, 17962–17967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu D., Sarker,R.I., Abe,K., Bolton,E. and Maloney,P.C. (2001) Structure/function relationships in OxlT, the oxalate-formate transporter of Oxalobacter formigenes. Assignment of transmembrane helix 11 to the translocation pathway. J. Biol. Chem., 276, 8753–8760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson P.J. and Maiden,M.C. (1990) Homologous sugar transport proteins in Escherichia coli and their relatives in both prokaryotes and eukaryotes. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci., 326, 391–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson R.H., Baldwin,J.H., Downing,K.H., Lepault,J. and Zemlin,F. (1986) Structure of purple membrane from Halobacterium halobium: recording, measurement and evaluation of electron micrographs at 3.5 Å resolution. Ultramicroscopy, 19, 147–178. [Google Scholar]

- Hirai T., Murata,K., Mitsuoka,K., Kimura,Y. and Fujiyoshi,Y. (1999) Trehalose embedding technique for high-resolution electron crystallography: application to structural study on bacteriorhodopsin. J. Electron Microsc., 48, 653–658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King S.C., Hansen,C.L. and Wilson,T.H. (1991) The interaction between aspartic acid 237 and lysine 358 in the lactose carrier of Escherichia coli. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 1062, 177–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulsen I.T., Sliwinski,M.K. and Saier,M.H.,Jr (1998) Microbial genome analyses: global comparisons of transport capabilities based on phylogenies, bioenergetics and substrate specificities. J. Mol. Biol., 277, 573–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulsen I.T., Nguyen,L., Sliwinski,M.K., Rabus,R. and Saier,M.H. (2000) Microbial genome analyses: comparative transport capabilities in eighteen prokaryotes. J. Mol. Biol., 301, 75–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg M.F., Mao,Q., Holzenburg,A., Ford,R.C., Deeley,R.G. and Cole,S.P.C. (2001) The structure of the multidrug resistance protein 1 (MRP1/ABCC1). Crystallization and single particle analysis. J. Biol. Chem., 276, 16076–16082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruan Z.-S., Anantharam,V., Crawford,I.T., Ambudkar,S.V., Rhee,S.-Y., Allison,M.J. and Maloney,P.C. (1992) Identification, purification and reconstitution of OxlT, the oxalate:formate antiport protein of Oxalobacter formigenes. J. Biol. Chem., 267, 10537–10543. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saurin W. and Dassa,E. (1994) Sequence relationships between integral membrane proteins of binding protein-dependent transport systems: evolution by recurrent gene duplications. Protein Sci., 3, 325–344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schertler G.F., Villa,C. and Henderson,R. (1993) Projection structure of rhodopsin. Nature, 362, 770–772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tate C.G., Kunji,E.R., Lebendiker,M. and Schuldiner,S. (2001) The projection structure of EmrE, a proton-linked multidrug transporter from Escherichia coli, at 7 Å resolution. EMBO J., 20, 77–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valpuesta J.M., Carrascosa,J.L. and Henderson,R. (1994) Analysis of electron microscope images and electron diffraction patterns of thin crystals of phi 29 connectors in ice. J. Mol. Biol., 240, 281–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q. and Kaback,H.R. (1999a) Location of helix III in the lactose permease of Escherichia coli as determined by site-directed thiol cross-linking. Biochemistry, 38, 16777–16782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q. and Kaback,H.R. (1999b) Proximity relationships between helices I and XI or XII in the lactose permease of Escherichia coli determined by site-directed thiol cross-linking. J. Mol. Biol., 291, 683–692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams K.A. (2000) Three-dimensional structure of the ion-coupled transport protein NhaA. Nature, 403, 112–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolin C.D. and Kaback,H.R. (2000) Thiol cross-linking of transmembrane domains IV and V in the lactose permease of Escherichia coli. Biochemistry, 39, 6130–6135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J. and Kaback,H.R. (1996) A general method for determining helix packing in membrane proteins in situ: helices I and II are close to helix VII in the lactose permease of Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 93, 14498–14502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J., Hardy,D. and Kaback,H.R. (1998) Transmembrane helix tilting and ligand-induced conformational changes in the lactose permease determined by site-directed chemical crosslinking in situ. J. Mol. Biol., 282, 959–967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye L., Jia,Z., Jung,T. and Maloney,P.C. (2001) Topology of OxlT, the oxalate transporter of Oxalobacter formigenes, determined by site-directed fluorescence labeling. J. Bacteriol., 183, 2490–2496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]