Abstract

The transient receptor potential vanilloid-1 (TRPV1) channel is a key mediator of pain perception and responds to various stimuli such as heat, low pH, and inflammation. Among TRPV1 antagonists, (R,E)-N-(2-hydroxy-2,3-dihydro-1H-inden-4-yl)-3-(2-(piperidin-1-yl)-4-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)-acrylamide (AMG8562) shows promise as a nonopioid analgesic, attenuating pain behaviors in rodent models without eliciting hyperthermic side effects commonly associated with other TRPV1 antagonists. Despite its potential, there has been limited research regarding the synthesis of AMG8562. Here, we present an asymmetric synthesis of AMG8562 featuring a lipase-catalyzed kinetic resolution of racemic 4-nitroindan-2-ol. This approach enables scalable access to enantiomerically pure material and provides a platform for the synthesis of structurally diverse AMG8562 analogues with potential for improved pharmacological properties.

Introduction

The transient receptor potential vanilloid-1 (TRPV1) channel is a polymodal cation channel involved in nociception. It is primarily expressed in the central and peripheral nervous system, and it is activated by a variety of painful stimuli, including heat (>43 °C), protons (pH < 5.3), and tissue damage, as well as by modulators, such as capsaicin, resiniferatoxin, substance P (SP), nerve growth factor (NGF), and prostaglandins. Genetic and pharmacological investigations have elucidated that TRPV1 agonists induce pain responses, , whereas mice with TRPV1 gene deletion exhibit reduced pain behaviors. − Furthermore, TRPV1 antagonists have been demonstrated to attenuate pain behaviors in rodent models of pain. , Based on this evidence, pharmacological targeting of TRPV1 has attracted particular interest, with TRPV1 antagonists becoming candidates for nonopioid pain management.

The pharmacophore of capsaicin-like TRPV1 ligands is well-defined, characterized by an aromatic “head” region, a linker “neck”, and a hydrophobic “tail” region (Figure A). However, shortly after the onset of clinical trials for such compounds, it was discovered that modulation of TRPV1 was accompanied by significant hyperthermia in both preclinical − and clinical trials. − This side-effect has been linked to TRPV1 modulation via ligand-induced conformational changes in the S4–S5 linker region, inducing hyperthermia by disrupting the tonic activation of TRPV1 by protons in the trunk. This disruption affects thermoregulatory reflexes, including thermogenesis and cutaneous vasoconstriction, leading to altered core body temperature. , Attempts to mitigate this effect have included structural modifications such as minimizing central nervous system penetration. However, these attempts have failed to eliminate hyperthermia. For example, peripherally restricted TRPV1 antagonists with low brain-to-plasma ratios still induce hyperthermia in preclinical models. Thus, when Lehto et al. reported that (R,E)-N-(2-hydroxy-2,3-dihydro-1H-inden-4-yl)-3-(2-(piperidin-1-yl)-4-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)-acrylamide (AMG8562) (1, Figure A), an N-aryl trans-cinnamide, significantly reduced pain behaviors in rodent models while not inducing hyperthermia, AMG8562 (1) garnered a significant amount of attention. It was notable that while AMG8562 (1) acted as a TRPV1 antagonist while bypassing the transient hyperthermic effect in rats, its (S)-enantiomer AMG8563 (2) showed similar antagonist capabilities but elicited a maximal increase in temperature of 1.2 °C at 40 min postadministration. This phenomenon of the two enantiomers of an TRPV1 antagonist eliciting divergent physiological responses underscores the critical role of stereochemistry in their pharmacological activity.

1.

(A) Structure of AMG8562 (1) and its (S)-enantiomer AMG8563 (2); (B) retrosynthesis of AMG8562 (1).

We were intrigued by the potential of AMG8562 (1) to provide insights on how to eliminate the on-target hyperthermic effect observed with other TRPV1 antagonists. While AMG8562 (1) is expected to have a hyperthermic effect in humans, studying its lack of such an effect in rodent models is crucial for guiding TRPV1 antagonist design to achieve similar outcomes in humans. Herein, we describe an asymmetric synthesis of AMG8562 (1) that leverages a lipase-catalyzed kinetic resolution of the head fragment, enabling access to AMG8562 (1) for further study. We found that while the head fragment follows Kazlauskas’ rule for the acylation of secondary racemic alcohols, the differences in the substituents next to the hydroxyl group are more subtle than what would be expected for the observed enantioselectivity; the enantiomeric excess (ee) achieved is significantly high compared to previously reported substrates.

Results and Discussion

The chiral (R)-4-aminoindan-2-ol ((R)-4, Figure B), the key fragment for the asymmetric synthesis of AMG8562 (1), is a reported structural motif in TRPV1 antagonists. It has previously been separated from its racemate using chiral high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). But separating desired chiral building blocks from racemic mixtures by chiral HPLC may present a challenge in the development of AMG8562 derivatives, primarily the limited scalability of chiral HPLC separation technique. Therefore, there is a need for alternative methods for the preparation of chiral secondary alcohols in high enantiomeric excess (ee). Toward this goal, we explored enzymatic chiral resolution. Figure B illustrates our approach to a convergent synthesis of AMG8562 (1) which could be realized by coupling α,β-unsaturated carboxylic acid 3 with (R)-4-aminoindan-2-ol ((R)-4). Carboxylic acid 3 is derived from the commercially available 2-fluoro-4-(trifluoromethyl)benzoic acid (5), while (R)-4-aminoindan-2-ol ((R)-4) is obtained from lipase-catalyzed kinetic resolution of racemic 4-nitroindan-2-ol (rac-6) followed by NO2 reduction.

To this end, we prepared racemic 4-nitroindan-2-ol (rac-6) for kinetic resolution and subsequent NO2 reduction (Scheme ). Starting with commercially available 4-nitroindan-1-one (7), NaBH4 reduction to the corresponding nitroindanol in 97% yield followed by elimination of benzylic alcohol in the presence of a catalytic amount of PTSA yielded nitroindene 8 (94%). Epoxidation by m-CPBA to give epoxide 9 (91%) followed by regioselective epoxide opening using NaBH3CN and ZnI2 furnished racemic 4-nitroindan-2-ol (rac-6) in 81% yield.

1. Preparation of Racemic 4-Nitroindan-2-ol (rac-6) .

a Reagents and conditions: (a) NaBH4, THF/MeOH (10:1), 25 °C, 0.5 h, 97%; (b) PTSA, benzene, reflux, 15 h, 94%; (c) m-CPBA, CH2Cl2, 0 °C, 16 h, 91%; (d) NaBH3CN, ZnI2, 1,2-dichloroethane, reflux, 1 h, 81%.

For the chiral resolution of secondary alcohols, methods such as chiral HPLC, enzymatic resolution, and diastereomeric salt formation are conventionally used in general. The chiral resolution method using HPLC requires a relatively expensive instrumental setting, and it exhibits limited scalability. The diastereomeric salt formation method requires stoichiometric or even excess amounts of a chiral resolving agent, increasing cost, especially for large-scale applications. Often, multiple recrystallizations are needed to achieve high enantiomeric purity, leading to significant material loss and time consumption. Therefore, we opted for the enzymatic kinetic resolution method to prepare (R)-4-nitroindan-2-ol ((R)-6) from rac-6.

A kinetic resolution of rac-6 utilizing lipase from Pseudomonas fluorescens and vinyl acetate showed initial promise, , as early tests showed approximately 50% of the substrate was acetylated within the first 24 h (Table ). Conversion of rac-6 to the corresponding acetate 10 plateaued thereafter, with minimal or little additional conversion observed after 48 h. After isolating acetate 10 from remaining 4-nitroindan-2-ol, we conducted a Mosher ester analysis to determine the absolute configuration of C2-OH in the unreacted 4-nitroindan-2-ol. The Mosher ester analysis of the remaining unreacted substrate revealed the remaining substrate was the (S)-enantiomer of rac-6 with >99% ee (see the Supporting Information for details). This indicates that the lipase-catalyzed kinetic resolution of rac-6 follows Kazlauskas’ rule.

1. Preparation of Enantiopure (R)-6 by Enzymatic Kinetic Resolution of rac-6 Using Amano AK Lipase from Pseudomonas fluorescens .

| entry | time (h) | product | ee of (R)-10 | yield of (R)-10 | product | ee of (S)-6 | yield of (S)-6 | E | conversion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3 h | (R)-enriched 10 | 99% | 41% | (S)-enriched 6 | 74% | 56% | 445 | 0.43 |

| 2 | 6 h | (R)-enriched 10 | 98% | 46% | (S)-enriched 6 | 99% | 48% | 525 | 0.50 |

| 3 | 24 h | (R)-enriched 10 | 86% | 49% | (S)-enriched 6 | >99% | 46% | 69 | 0.54 |

| 4 | 48 h | (R)-enriched 10 | 82% | 52% | (S)-enriched 6 | >99% | 45% | 52 | 0.55 |

| 5 | 5 h | (R)-enriched 10 | >99% | 38% | (S)-enriched 6 | 57% | 61% | 355 | 0.37 |

Reagents and conditions: (a) Amano AK lipase from Pseudomonas fluorescens, vinyl acetate, toluene, 40 °C, 3–48 h; (b) K2CO3, MeOH, 40 °C, 1 h, 63%; (c) H2, Pd/C (10 wt %), MeOH, 25 °C, 12 h, 86% for (R)-4, 76% for (S)-4.

All reactions were performed with a 0.16 M solution of rac-6 in toluene at 40 °C, using 2 eq. of vinyl acetate and 10 wt % of Amano lipase.

The ee was determined by a chiral HPLC separation of the corresponding alcohol obtained upon hydrolysis of (R)-10.

Isolated yield.

The ee was determined by a chiral HPLC separation of (S)-6 from kinetic resolution.

Calculated according to Chen et al. using the equation: E = ln[(1 – c)(1 – ees)]/ln[(1 – c)(1 + ees)], where c (conversion) was determined from the enantiomeric excess of the recovered (S)-6 (ees) and the product (R)-10 (eep), using the formula c = ees/(ees + eep).

The reaction was performed on a 50 mg scale.

The reaction was performed on an 862 mg scale.

Various reaction times for lipase-catalyzed kinetic resolution were attempted to maximize the yield and optical purity of acetate 10 (Table ). Optical purity was measured by separation on a Chiralpak IA column, monitoring at 254 nm (see the Supporting Information for details). For each condition, the acetate product 10 and unreacted nitroindanol 6 were first separated by SiO2-column chromatography; chiral HPLC analysis was performed after hydrolysis of acetate 10 to the corresponding secondary alcohol, as well as on the remaining nitroindanol substrate. Gratifyingly, a kinetic resolution for 3 h under the conditions in Table (entry 1), followed by hydrolysis with K2CO3, gave (R)-6 in high enantiomeric excess (99% ee). Under similar conditions, a gram-scale kinetic resolution of rac-6 afforded the desired (R)-10 in 38% yield with >99% ee (entry 5). Reduction with H2 and Pd/C (10 wt %) of (R)-6 furnished (R)-4-aminoindan-2-ol ((R)-4) in 86% yield. The corresponding (S)-4-aminoindan-2-ol ((S)-4), the head fragment of AMG8563 (2, enantiomer of AMG8562), was also obtained by purification of enantiopure unreacted substrate (S)-4 afforded by the kinetic resolution, followed by reduction of the nitro group (Table ).

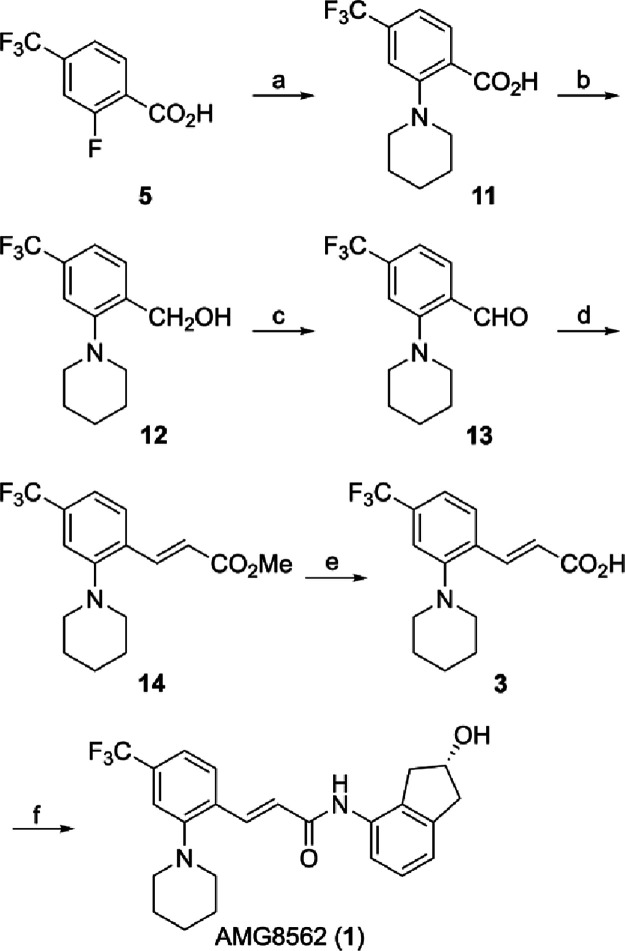

With aminoindanol (R)-4 in hand, we turned our attention to synthesizing α,β-unsaturated acid 3 for amide formation with (R)-4 (Scheme ). Starting with commercially available 2-fluoro-4-(trifluoromethyl) benzoic acid (5) in MeCN, heating with piperidine in a pressurized reaction tube yielded the substitution product 11 in 76% yield. Initially, conversion of carboxylic acid 11 to aldehyde 13 was thought to be possible through LiAlH4 reduction of a Weinreb amide intermediate, as reported by Nahm et al. However, the addition of CDI to 11, followed by N,O-dimethylhydroxylamine hydrochloride and Et3N, showed no formation of the corresponding Weinreb amide in THF or CH2Cl2. We decided to shift our efforts on a reduction to alcohol 12, followed by mild oxidation to aldehyde 13. Initial attempts in directly reducing carboxylic acid 11 to benzyl alcohol 12 with LiAlH4 resulted in poor yields (<25%) due to the formation of unidentifiable side products; to explore milder reducing conditions, we first converted carboxylic acid 11 to a mixed anhydride using ethyl chloroformate, followed by NaBH4 reduction. Gratifyingly, this method yielded alcohol 12 in 69% yield, which was oxidized by MnO2 to furnish the corresponding aldehyde 13 in 82% yield (91% BRSM).

2. Preparation of Carboxylic Acid 3 and Completion of the Synthesis of AMG8562 (1) .

a Reagents and conditions: (a) piperidine, MeCN, 200 °C, 6 h, 76%; (b) ClCO2Et, Et3N, THF, −10 °C, 0.5 h; NaBH4, THF, MeOH, 0 °C, 1.5 h, 69%; (c) MnO2, CH2Cl2, 0 to 25 °C, 16 h, 82% (91% BRSM); (d) methyl (triphenylphosphoranylidene)acetate, toluene, 100 °C, 16 h, 81% (E/Z = 9.8:1); (e) 1 N LiOH, THF/MeOH (2:1), 25 °C, 1 h, 93%; (f) (R)-4, DMTMM, MeOH, 25 °C, 24 h, 87%.

To install the desired α,β-unsaturated (E)-alkene, we treated the aldehyde with methyl (triphenylphosphoranylidene) acetate (Scheme ). Successful production of α,β-unsaturated methyl ester 14 (81%) was observed, with a E/Z ratio of 9.8:1, which were separated by SiO2 column chromatography. Finally, hydrolysis of 14 furnished the desired α,β-unsaturated carboxylic acid 3 in 93% yield. To achieve the formation of the desired amide 1, DCC and DMAP were added to a solution of 3 and (R)-4 in CH2Cl2 (see the Supporting Information for details). Unexpectedly, this resulted in esterification between 3 and (R)-4. The same ester product was also observed utilizing DCC without DMAP. To circumvent this side reaction, we first protected the alcohol moiety of aminoindanol (R)-4 as the corresponding TBS ether, followed by DCC/DMAP to afford the corresponding TBS-protected amide. This was followed by desilylation to complete the asymmetric synthesis of AMG8562 (1). Fortunately, it was later discovered that using the coupling agent 4-(4,6-dimethoxy-1,3,5-triazin-2-yl)-4-methylmorpholinium chloride (DMTMM) in MeOH proved to be more efficient, directly producing AMG8562 (1, 87%, 99% ee) without the need for a protecting group. The enantiomeric AMG8563 (2, 99% ee) was prepared in a similar manner.

Conclusions

In summary, the ability of AMG8562 (1) to act as a TRPV1 antagonist in rodent models without causing hyperthermia makes it a valuable tool for studying the role of TRPV1 in pain signaling and body temperature regulation. AMG8562 (1) is also a lead compound for developing nonaddictive analgesics. We highlight the asymmetric synthesis of AMG8562 (1), leveraging a lipase-catalyzed chiral resolution of the head fragment, leading to a synthetic route for its preparation on a large-scale. Specifically, this study underscores the application of lipase from Pseudomonas fluorescens with AMG8562’s head fragment, demonstrating the enzyme’s versatility in handling substrates with subtle substituent differences. We expect that this work will facilitate the in-depth study of AMG8562 (1) by providing a more straightforward and efficient synthesis, thereby making it more accessible for researchers investigating TRPV1-related mechanisms and therapeutic applications. Our synthesis will also allow a generation of a diverse set of AMG8562 (1) for structure–activity relationship (SAR) and preclinical studies. Future work should focus on further understanding the stereochemical influences on the pharmacological activity of TRPV1 antagonists.

Experimental Section

General Methods

All reactions were conducted in oven-dried glassware under nitrogen. Unless otherwise stated, all reagents were purchased from commercial suppliers (Sigma-Aldrich, VWR, TCI, or Ambeed) and used without further purification. All solvents were American Chemical Society (ACS) grade or better and used without further purification. Analytical thin layer chromatography (TLC) was performed with glass-backed silica gel (60 Å) plates with fluorescent indication (Whatman). Visualization was accomplished by UV irradiation at 254 nm and/or by staining with p-anisaldehyde solution or potassium permanganate solution followed by heating. Flash column chromatography was performed by using silica gel (particle size 230–400 mesh, 60 Å) purchased from Silicycle. All 1H NMR and 13C NMR spectra were recorded with a Bruker 500 (500 MHz) spectrometer. All NMR δ values are given in parts per million (ppm) and are referenced to the residual isotopomer solvent signals (CDCl3: δ 7.26 ppm, CD3OD: δ 3.31 ppm, (CD3)2SO: δ 2.50 ppm) for 1H NMR spectra, or the solvent signals (CDCl3: δ 77.16 ppm, CD3OD: δ 49.00 ppm, (CD3)2SO: δ 39.52 ppm) for 13C NMR spectra. Coupling constants (J) are given in Hertz (Hz) and multiplicities are indicated using the conventional abbreviation (s = singlet, d = doublet, t = triplet, q = quartet, quint = quintet, m = multiplet or overlap of nonequivalent resonances, br = broad). Electrospray ionization (ESI) mass spectrometry (MS) was recorded with an Agilent 6224 series (LC/MS–TOF) spectrometer to obtain the molecular masses of the compounds. Optical rotation values were measured with a Rudolph Research Analytical (A21102 API/1W) polarimeter. Chiral HPLC analyses were performed on a Daicel Chiralpak IA column (Daicel Chiral Technologies) under the specified conditions.

4-Nitro-2,3-dihydro-1H-inden-1-ol (S1)

To a solution of 4-nitroindan-1-one (7) (950 mg, 5.36 mmol) in THF (9.5 mL, 0.56 M) was slowly added NaBH4 (80.0 mg, 2.11 mmol) and MeOH (0.95 mL). After being stirred at 25 °C for 0.5 h, the reaction mixture was concentrated in vacuo, diluted with H2O, and extracted three times with 50% EtOAc in hexanes. The layers were separated, and the aqueous layer was extracted with EtOAc. The combined organic layers were dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, filtered, and concentrated in vacuo. The residue was purified by column chromatography (silica gel, hexanes/EtOAc, 1:1) to afford S1 (934 mg, 97%) as a clear oil: 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.13 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 7.73 (d, J = 7.4 Hz, 1H), 7.44 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 5.33 (t, J = 6.5 Hz, 1H), 3.57 (ddd, J = 18.3, 8.8, 4.5 Hz, 1H), 3.34–3.24 (m, 1H), 2.60 (dddd, J = 13.2, 8.4, 7.1, 4.5 Hz, 1H), 2.03 (dddd, J = 12.9, 8.8, 6.9, 5.7 Hz, 1H). HRMS (ESI-TOF) m/z: [M + NH4]+ Calcd for C9H13N2O3 197.0921; Found 197.0920.

7-Nitro-1H-indene (8)

To a solution of S1 (934 mg, 5.21 mmol) in benzene (21 mL, 0.25 M) was added PTSA (90.0 mg, 0.521 mmol). After stirring at reflux for 15 h, the reaction mixture was washed with saturated aqueous NaHCO3. The aqueous layer was extracted with 10% EtOAc in hexanes. The combined organic layers were dried over anhydrous Na2SO4 and concentrated in vacuo. The residue was purified by column chromatography (silica gel, hexanes/EtOAc, 20:1) to afford 8 (790 mg, 94%) as a white solid: 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.06 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 7.69 (dd, J = 7.4, 0.9 Hz, 1H), 7.46 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 6.94 (dt, J = 5.5, 1.8 Hz, 1H), 6.76 (dt, J = 5.6, 1.9 Hz, 1H), 3.94 (t, J = 1.9 Hz, 2H).

5-Nitro-1a,6a-dihydro-6H-indeno[1,2-b]oxirene (rac-9)

To a solution of 8 (790 mg, 4.90 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (25 mL, 0.20 M) was added m-CBPA (purity ≤ 77%, 2.09 g, 9.33 mmol) slowly under stirring at 0 °C. The reaction mixture was stirred at 0 °C for 16 h, diluted with 20% aqueous Na2CO3 solution, and extracted with CH2Cl2. The organic portions were dried over anhydrous Na2SO4 and concentrated in vacuo. The residue was purified by column chromatography (silica gel, hexanes/EtOAc, 9:1) to afford rac-9 (790 mg, 91%) as a white solid: 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.13 (dd, J = 8.3, 1.0 Hz, 1H), 7.80 (dd, J = 7.3, 1.0 Hz, 1H), 7.41 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 4.37 (dd, J = 2.8, 1.4 Hz, 1H), 4.24 (t, J = 2.8 Hz, 1H), 3.76 (dd, J = 19.8, 1.3 Hz, 1H), 3.42 (dd, J = 19.8, 2.9 Hz, 1H).

4-Nitro-2,3-dihydro-1H-inden-2-ol (rac-6)

To a solution of rac-9 (790 mg, 4.46 mmol) in 1,2-dichloroethane (11.6 mL, 0.38 M) was slowly added zinc iodide (2.10 g, 6.58 mmol) and sodium cyanoborohydride (2.12 g, 33.74 mmol) under stirring at 25 °C. The reaction mixture was refluxed for 1 h, then cooled to 0 °C, and diluted with 20% aqueous Na2CO3 solution to quench the excess sodium cyanoborohydride. After stirring for 0.5 h, the solution was extracted with CH2Cl2, and the organic part was dried over anhydrous Na2SO4 and concentrated in vacuo. The residue was purified by column chromatography (silica gel, hexanes/EtOAc, 4:1) to afford rac-6 (650 mg, 81%) as a yellow-white solid: 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.03 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 7.55 (d, J = 7.4 Hz, 1H), 7.36 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 4.81–4.78 (m, 1H), 3.64 (dd, J = 18.5, 5.7 Hz, 1H), 3.48 (dd, J = 18.4, 2.4 Hz, 1H), 3.28 (dd, J = 16.8, 5.9 Hz, 1H), 3.03 (dd, J = 16.8, 2.4 Hz, 1H); HRMS (ESI-TOF) m/z: [M + NH4]+ Calcd for C9H13N2O3 197.0921; Found 197.0924.

(R)-4-Nitro-2,3-dihydro-1H-inden-2-yl Acetate ((R)-10)

To a solution of rac- 6 (50 mg, 0.279 mmol) in toluene (1.7 mL, 0.16 M) was slowly added vinyl acetate (0.0514 mL, 0.558 mmol) and Amano Lipase from Pseudomonas fluorescens (5 mg, ∼ 20,000 U/g). The reaction mixture was stirred at 40 °C for 3 h and then concentrated in vacuo. The residue was purified by column chromatography (silica gel, hexanes/EtOAc, 6:1) to afford acetate (R)-10 (25.3 mg, 41%, 99% ee) as a white solid and the remaining (S)-enriched alcohol 6 (28.0 mg, 56%, 74% ee) as a yellow-white solid; [Large-Scale Kinetic Resolution] To a solution of rac- 6 (862 mg, 4.81 mmol) in toluene (30 mL, 0.16 M) was slowly added vinyl acetate (0.89 mL, 9.62 mmol) and Amano Lipase from Pseudomonas fluorescens (86.2 mg, ∼ 20,000 U/g). The reaction mixture was stirred at 40 °C for 5 h and then concentrated in vacuo. The residue was purified by column chromatography (silica gel, hexanes/EtOAc, 6:1) to afford acetate (R)-10 (398.6 mg, 38%, >99% ee) as a white solid and the remaining (S)-enriched alcohol 6 (527.4 mg, 61%, 57% ee) as a yellow-white solid.

For acetate (R)-10: 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.05 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 7.54 (d, J = 7.4 Hz, 1H), 7.38 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 5.61–5.57 (m, 1H), 3.73 (dd, J = 19.1, 6.3 Hz, 1H), 3.58 (dd, J = 19.0, 2.4 Hz, 1H), 3.40 (dd, J = 17.5, 6.4 Hz, 1H), 3.11 (dd, J = 17.5, 2.3 Hz, 1H), 2.02 (s, 3H); HRMS (ESI-TOF) m/z: [M + Na]+ Calcd for C11H11NO4Na 244.0580; Found 244.0584.

For (S)-enriched alcohol 6: 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.04 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 7.55 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 1H), 7.36 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 4.82–4.79 (m, 1H), 3.65 (dd, J = 18.5, 5.7 Hz, 1H), 3.49 (dd, J = 18.5, 2.4 Hz, 1H), 3.29 (dd, J = 16.8, 5.9 Hz, 1H), 3.04 (dd, J = 16.8, 2.4 Hz, 1H), 1.68 (s, 1H).

(R)-4-Nitro-2,3-dihydro-1H-inden-2-ol ((R)-6)

To a solution of (R)-10 (300 mg, 1.37 mmol) in MeOH (50 mL, 0.03 M) was slowly added K2CO3 (1.127 g, 8.16 mmol). The reaction mixture was stirred at 40 °C for 1 h, dried in vacuo, diluted with H2O, and extracted with CH2Cl2. The combined organic layers were dried over anhydrous Na2SO4 and concentrated in vacuo. The residue was purified by column chromatography (silica gel, hexanes/EtOAc, 4:1) to afford (R)-6 (154 mg, 63%, 99% ee) as a yellow-white solid: −133.1 (c 0.1, MeOH); 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.04 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 7.55 (d, J = 7.4 Hz, 1H), 7.36 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 4.82–4.79 (m, 1H), 3.65 (dd, J = 18.6, 5.7 Hz, 1H), 3.49 (dd, J = 18.6, 2.3 Hz, 1H), 3.29 (dd, J = 16.8, 5.9 Hz, 1H), 3.04 (dd, J = 16.9, 2.4 Hz, 1H), 1.71 (s, 1H).

(R)-4-Amino-2,3-dihydro-1H-inden-2-ol ((R)-4)

To a solution of (R)-6 (154 mg, 0.859 mmol) in MeOH (3.7 mL, 0.23 M) was slowly added Pd/C (10 wt %, 37 mg) at 25 °C. The reaction mixture was evacuated then backfilled with hydrogen gas three times and attached to a hydrogen source. The reaction mixture was then stirred at 25 °C for 12 h. The catalyst was filtered over a pad of Celite, and the filtrate was concentrated in vacuo. The residue was purified by column chromatography (silica gel, hexanes/EtOAc, 2:3) to afford (R)-4 (110 mg, 86%, 99% ee) as a white crystalline solid: 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.02 (t, J = 7.7 Hz, 1H), 6.70 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H), 6.54 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 4.73 (br s, 1H), 3.58 (br s, 2H), 3.21 (dd, J = 16.5, 6.0 Hz, 1H), 3.05 (dd, J = 15.9, 6.1 Hz, 1H), 2.90 (dd, J = 16.5, 3.3 Hz, 1H), 2.73 (dd, J = 15.9, 3.1 Hz, 1H), 1.66 (br s, 1H); HRMS (ESI-TOF) m/z: [M + H]+ Calcd for C9H12NO 150.0913; Found 150.0912.

(S)-4-Amino-2,3-dihydro-1H-inden-2-ol ((S)-4)

To a solution of (S)-6 (250 mg, 1.40 mmol; +134.9, c 0.1, MeOH) in MeOH (6 mL, 0.23 M) was slowly added Pd/C (10 wt %, 60 mg) at 25 °C. The reaction mixture was evacuated then backfilled with hydrogen gas three times and attached to a hydrogen source. The reaction mixture was then stirred for 12 h at 25 °C. The catalyst was filtered over a pad of Celite and the filtrate was concentrated in vacuo. The residue was purified by column chromatography (silica gel, hexanes/EtOAc, 2:3) to afford (S)-4 (158 mg, 76%, 99% ee) as a white crystalline solid: 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.02 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 6.70 (d, J = 7.4 Hz, 1H), 6.54 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H), 4.75–4.71 (m, 1H), 3.58 (br s, 2H), 3.21 (dd, J = 16.4, 6.1 Hz, 1H), 3.05 (dd, J = 15.8, 6.1 Hz, 1H), 2.90 (dd, J = 16.4, 3.2 Hz, 1H), 2.73 (dd, J = 15.9, 3.1 Hz, 1H), 1.69 (br s, 1H).

2-(Piperidin-1-yl)-4-(trifluoromethyl)benzoic Acid (11)

In a heavy wall pressure vessel, a solution of 2-fluoro-4-(trifluoromethyl)benzoic acid (5) (940 mg, 4.52 mmol) in MeCN (7 mL, 0.65 M) was added piperidine (1.42 g 16.7 mmol). The reaction mixture was then placed in a 200 °C sand bath and stirred for 6 h. The reaction mixture was then cooled to 25 °C and dried in vacuo. The residue was purified by column chromatography (silica gel, hexanes/EtOAc, 1:1) to afford 2-(piperidin-1-yl)-4-(trifluoromethyl)benzoic acid (11, 940 mg, 76%) as a white crystalline solid: 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO) δ 8.11 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 7.99 (s, 1H), 7.68 (dd, J = 8.2, 1.7 Hz, 1H), 3.13 (t, J = 5.4 Hz, 4H), 1.75–1.70 (m, 4H), 1.63–1.59 (m, 2H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO) δ 166.25, 151.09, 132.94 (q, 2 J CF = 32.0 Hz, C4), 131.77, 128.77, 123.46 (q, 1 J CF = 271.8 Hz, CF3), 122.36, 119.43, 53.21, 25.49, 22.33; HRMS (ESI-TOF) m/z: [M + H]+ Calcd for C13H15F3NO2 274.1049; Found 274.1055.

2-(Piperidin-1-yl)-4-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)methanol (12)

To a cooled solution of 11 (920 mg, 3.367 mmol) in anhydrous THF (40 mL, 0.08 M) at –10 °C was added Et3N (1.022 g, 10.10 mmol) followed by ethyl chloroformate (731 mg, 6.734 mmol). The mixture was stirred at –10 °C for 0.5 h, then filtered through a cotton plug. The filter cake was washed with anhydrous THF (40 mL). The crude solution containing the mixed anhydride was used in immediately in the following step without further concentration or purification. To a cooled (0 °C) solution of the crude mixed anhydride in THF was added NaBH4 (1.010 g, 26.70 mmol), followed by dropwise addition of MeOH (5.0 mL). After stirring at 0 °C for 1.5 h, the reaction mixture was quenched with a saturated solution of NH4Cl (30.0 mL), and the aqueous part was extracted three times with EtOAc. The combined organic layers were dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, filtered, and concentrated in vacuo. The residue was purified by column chromatography (silica gel, hexanes/EtOAc, 6:1) to afford 12 (605 mg, 69%) as a clear oil: 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.41 (s, 1H), 7.35 (d, J = 7.4 Hz, 1H), 7.29 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H), 5.37 (br s, 1H), 4.84 (s, 2H), 2.94 (t, J = 5.2 Hz, 4H), 1.80–1.76 (m, 4H), 1.64–1.60 (m, 2H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 153.24, 139.47, 130.42 (q, 2 J CF = 32.2 Hz, C4), 128.74, 124.15 (q, 1 J CF = 272.2 Hz, CF3), 121.14 (q, 3 J CF = 4.0 Hz, C5), 117.53 (q, 3 J CF = 3.7 Hz, C3), 63.91, 53.87, 26.59, 23.90; HRMS (ESI-TOF) m/z: [M + H]+ Calcd for C13H17F3NO 260.1257; Found 260.1264.

2-(Piperidin-1-yl)-4-(trifluoromethyl)benzaldehyde (13)

To a cooled solution of 12 (600 mg, 2.31 mmol) in anhydrous CH2Cl2 (45 mL, 0.05 M) at 0 °C was slowly added activated MnO2 (2.4 g, 27.8 mmol). The mixture was allowed to warm up to 25 °C and stirred at 25 °C for 16 h. The solids were removed by vacuum filtration, and the filtrate was concentrated in vacuo. The residue was purified by column chromatography (silica gel, hexanes/EtOAc, 7:1) to afford aldehyde 13 (490 mg, 82%, 91% BRSM) as a clear yellow oil: 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 10.29 (s, 1H), 7.89 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.38 (s, 1H), 7.33 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 3.14 (t, J = 4.5 Hz, 4H), 1.85–1.80 (m, 4H), 1.67–1.62 (m, 2H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 190.67, 156.78, 135.89 (q, 2 J CF = 32.2 Hz, C4), 130.78, 130.01, 123.73 (q, 1 J CF = 273.2 Hz, CF3), 118.34 (q, 3 J CF = 3.8 Hz, C5), 116.05 (q, 3 J CF = 3.7 Hz, C3), 55.56, 26.15, 23.96; HRMS (ESI-TOF) m/z: [M + H]+ Calcd for C13H15F3NO 258.1100; Found 258.1106.

Methyl (E)-3-(2-(Piperidin-1-yl)-4-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)acrylate (14)

In a heavy wall cylindrical pressure vessel, a solution of 13 (490 mg, 1.90 mmol) in toluene (40 mL, 0.05 M) was added methyl (triphenylphosphoranylidene)acetate (830 mg 2.48 mmol). The reaction mixture was then placed in a 100 °C sand bath and stirred for 16 h. The reaction mixture was quenched with H2O, and the aqueous part was extracted three times with EtOAc. The combined organic layers were dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, filtered, and concentrated in vacuo. The residue was purified by column chromatography (silica gel, hexanes/EtOAc, 50:1) to afford 14 (484 mg, 81%) as a clear yellow oil, along with the (Z)-isomer (14’, 49.5 mg, 8.3%): Compound 14: 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.10 (d, J = 16.1 Hz, 1H), 7.60 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 7.35 (s, 1H), 7.31 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 6.46 (d, J = 16.1 Hz, 1H), 3.83 (s, 3H), 3.01 (t, J = 5.3 Hz, 4H), 1.88–1.83 (m, 4H), 1.66–1.60 (m, 2H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 167.51, 153.96, 141.48, 132.36 (q, 2 J CF = 32.2 Hz, C4), 131.93, 128.36, 124.10 (q, 1 J CF = 272.9 Hz, CF3), 119.13, 118.86 (q, 3 J CF = 3.8 Hz, C5), 115.82 (q, 3 J CF = 3.7 Hz, C3), 54.18, 51.82, 26.26, 24.13; HRMS (ESI-TOF) m/z: [M + H]+ Calcd for C16H19F3NO2 314.1362; Found 314.1371; Compound 14’: 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) 7.57 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 7.21 (d, J = 6.9 Hz, 1H), 7.20 (s, 1H), 7.14 (d, J = 12.3 Hz, 1H), 6.02 (d, J = 12.3 Hz, 1H), 3.70 (s, 3H), 2.95 (t, J = 5.3 Hz, 4H), 1.72–1.68 (m, 4H), 1.62–1.55 (m, 2H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 166.76, 153.11, 141.86, 132.74, 131.53 (q, 2 J CF = 32.0 Hz, C4), 131.36, 124.27 (q, 1 J CF = 270.4 Hz, CF3), 119.28, 118.04, 114.83, 53.82, 51.50, 26.46, 24.20; HRMS (ESI-TOF) m/z: [M + H]+ Calcd for C16H19F3NO2 314.1362; Found 314.1370.

(E)-3-(2-(Piperidin-1-yl)-4-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)acrylic Acid (3)

To a solution of 14 (484 mg, 1.54 mmol) in THF (40 mL, 0.04 M) was added MeOH (20 mL) and aqueous 1 N LiOH (30 mL). The reaction mixture was then stirred at 25 °C for 1 h before it was neutralized with 1 N HCl (20 mL). The resulting mixture was diluted with EtOAc and extracted three times with EtOAc. The combined organic layers were dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, filtered, and concentrated in vacuo. The residue was purified by column chromatography (silica gel, hexanes/EtOAc, 1:1) to afford 3 (431 mg, 93%) as a yellow solid: 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.20 (d, J = 16.1 Hz, 1H), 7.65 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 7.36 (s, 1H), 7.35 (d, J = 6.9 Hz, 1H), 6.47 (d, J = 16.1 Hz, 1H), 3.05 (t, J = 5.2 Hz, 4H), 1.89 (p, J = 5.6 Hz, 4H), 1.67–1.63 (m, 2H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 172.95, 154.23, 143.76, 132.81 (q, 2 J CF = 32.2 Hz, C4), 131.52, 128.67, 124.08 (q, 1 J CF = 272.2 Hz, CF3), 118.92 (q, 3 J CF = 3.7 Hz, C5), 118.66, 115.93 (q, 3 J CF = 3.7 Hz, C3), 54.34, 26.30, 24.15; HRMS (ESI-TOF) m/z: [M + H]+ Calcd for C15H17F3NO2 300.1206; Found 300.1211.

(R,E)-N-(2-Hydroxy-2,3-dihydro-1H-inden-4-yl)-3-(2-(piperidin-1-yl)-4-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)acrylamide (1, AMG8562)

To a solution of 3 (120 mg, 0.402 mmol) and (R)-4 (50.0 mg, 0.335 mmol) in MeOH (6.5 mL) was added DMTMM (139 mg, 0.503 mmol). The reaction mixture was then stirred at 25 °C for 24 h. The reaction solvent was removed in vacuo and the residue was diluted with a saturated solution of NaHCO3 (10 mL). The aqueous portion was extracted three times with EtOAc. The combined organic layers were washed five times with a saturated solution of Na2CO3, dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, filtered, and concentrated in vacuo. The residue was purified by column chromatography (silica gel, hexanes/EtOAc, 2:1) to afford AMG8562 (1, 125 mg, 87%, 99% ee) as a yellow solid: −34.5 (c 0.15, MeOH); 1H NMR (500 MHz, CD3OD) δ 8.02 (d, J = 15.8 Hz, 1H), 7.73 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 7.50 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.32 (s, 1H), 7.29 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 7.13 (t, J = 7.7 Hz, 1H), 7.04 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H), 6.96 (d, J = 15.8 Hz, 1H), 4.63–4.59 (m, 1H), 3.16 (dd, J = 16.4, 6.1 Hz, 2H), 2.95 (t, J = 5.3 Hz, 4H), 2.88 (ddd, J = 16.6, 7.3, 3.5 Hz, 2H), 1.80–1.76 (m, 4H), 1.62–1.57 (m, 2H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CD3OD) δ 166.42, 154.32, 143.86, 138.69, 135.47, 135.27, 133.94, δ 132.89 (q, 2 J CF = 31.7 Hz, C4), 129.39, 128.15, 125.43 (q, 1 J CF = 270.1 Hz, CF3), 124.08, 122.98, 122.32, 120.39, 116.79, 73.20, 55.30, 43.39, 41.24, 27.10, 24.88; HRMS (ESI-TOF) m/z: [M + H]+ Calcd for C24H26F3N2O2 431.1941; Found 431.1949.

(S,E)-N-(2-Hydroxy-2,3-dihydro-1H-inden-4-yl)-3-(2-(piperidin-1-yl)-4-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)acrylamide (2, AMG8563)

To a solution of 3 (145 mg, 0.484 mmol) and (S)-4 (60.0 mg, 0.402 mmol) in MeOH (6.0 mL) was added DMTMM (189 mg, 0.683 mmol). The reaction mixture was then stirred at 25 °C for 24 h. The reaction solvent was removed in vacuo and the residue was diluted with a saturated solution of NaHCO3 (10 mL). The aqueous portion was extracted three times with EtOAc, then the combined organic layers were washed five times with a saturated solution of Na2CO3, dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, filtered, and concentrated in vacuo. The residue was purified by column chromatography (silica gel, hexanes/EtOAc, 2:1) to afford AMG8563 (2, 163 mg, 94%, 99% ee) as a yellow solid: +37.1 (c 0.15, MeOH); 1H NMR (500 MHz, CD3OD) δ 8.02 (d, J = 15.8 Hz, 1H), 7.73 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.50 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H), 7.30 (s, 1H), 7.28 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 7.14 (t, J = 7.7 Hz, 1H), 7.05 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H), 6.94 (d, J = 15.8 Hz, 1H), 4.63–4.59 (m, 1H), 3.16 (ddd, J = 16.5, 6.2, 3.4 Hz, 2H), 2.97–2.84 (m, 6H), 1.80–1.75 (m, 4H), 1.62–1.57 (m, 2H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CD3OD) δ 166.52, 154.72, 143.94, 138.89, 135.61, 135.32, 134.07, 132.95 (q, 2 J CF = 31.9 Hz, C4), 129.38, 128.21, 125.51 (q, 1 J CF = 270.0 Hz, CF3), 123.95, 123.06, 122.41, 120.28, 116.81, 73.26, 55.30, 43.44, 41.29, 27.21, 25.00; HRMS (ESI-TOF) m/z: [M + H]+ Calcd for C24H26F3N2O2 431.1941; Found 431.1947.

Determination of Enantiomeric Excess of 1 and 2 by Chiral HPLC

Enantiomeric excess (ee) was determined by chiral HPLC analysis on a Daicel Chiralpak IA column (250 × 4.6 mm ID, particle size 3 μm, Daicel Chiral Technologies) using a Shimadzu LC-20 series HPLC system equipped with a UV/vis detector set at 254 nm. The mobile phase consisted of hexanes/EtOAc (65:35 v/v) prepared using HPLC-grade solvents obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. Flow rate was maintained at 1.5 mL/min. Samples were prepared by dissolving approximately 0.3 to 0.4 mg of the compound in 10 mL of hexanes/EtOAc (65:35 v/v), filtering through a 0.22 μm PTFE syringe filter, and injecting 40 μL into the column. The column temperature was maintained at 25 °C. The retention times were 10.3 min for AMG8562 (1) and 17.2 min for AMG8563 (2). Peak areas were integrated for each sample. All data were processed using Shimadzu LabSolutions software.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the grants from the National Eye Institute (NIH 5R01EY031698-06) and Duke Undergraduate Research Support (URS) Independent Study Grants. We would like to acknowledge the Duke Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy Center (DMRSC) for providing NMR support and thank Dr. Peter Silinski for assistance with HRMS data collection and analysis.

The data underlying this study are available in the published article and its online Supporting Information.

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.5c08033.

Preparation of AMG8562 (1) by DCC/DMAP coupling, Mosher ester analysis of (S)-6, lipase-catalyzed kinetic resolution of rac-6, and copy of 1H NMR spectra, 13C NMR spectra, and chiral HPLC chromatograms (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- Julius D.. TRP Channels and Pain. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2013;29:355–384. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-101011-155833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones N. G., Slater R., Cadiou H., McNaughton P., McMahon S. B.. Acid-Induced Pain and Its Modulation in Humans. J. Neurosci. 2004;24:10974–10979. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2619-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szallasi A., Blumberg P. M.. Vanilloid (Capsaicin) Receptors and Mechanisms. Pharmacol. Rev. 1999;51:159–211. doi: 10.1016/S0031-6997(24)01403-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caterina M. J., Leffler A., Malmberg A. B., Martin W. J., Trafton J., Petersen-Zeitz K. R., Koltzenburg M., Basbaum A. I., Julius D.. Impaired Nociception and Pain Sensation in Mice Lacking the Capsaicin Receptor. Science. 2000;288:306–313. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5464.306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis J. B., Gray J., Gunthorpe M. J., Hatcher J. P., Davey P. T., Overend P., Harries M. H., Latcham J., Clapham C., Atkinson K., Hughes S. A., Rance K., Grau E., Harper A. J., Pugh P. L., Rogers D. C., Bingham S., Randall A., Sheardown S. A.. Vanilloid Receptor-1 Is Essential for Inflammatory Thermal Hyperalgesia. Nature. 2000;405:183–187. doi: 10.1038/35012076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keeble J., Russell F., Curtis B., Starr A., Pinter E., Brain S. D.. Involvement of Transient Receptor Potential Vanilloid 1 in the Vascular and Hyperalgesic Components of Joint Inflammation. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:3248–3256. doi: 10.1002/art.21297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gavva N. R., Tamir R., Qu Y., Klionsky L., Zhang T. J., Immke D., Wang J., Zhu D., Vanderah T. W., Porreca F., Doherty E. M., Norman M. H., Wild K. D., Bannon A. W., Louis J.-C., Treanor J. J. S.. AMG 9810 [(E)-3-(4-t-Butylphenyl)-N-(2,3-Dihydrobenzo[B][1,4] Dioxin-6-Yl)Acrylamide], a Novel Vanilloid Receptor 1 (TRPV1) Antagonist with Antihyperalgesic Properties. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2005;313:474–484. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.079855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehto S. G.. et al. Antihyperalgesic Effects of (R, E)-N-(2-Hydroxy-2,3-Dihydro-1H-Inden-4-Yl)-3-(2-(Piperidin-1-Yl)-4-(Trifluoromethyl)Phenyl)-Acrylamide (AMG8562), a Novel Transient Receptor Potential Vanilloid Type 1 Modulator That Does Not Cause Hyperthermia in Rats. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2008;326:218–229. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.132233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kym P. R., Kort M. E., Hutchins C. W.. Analgesic Potential of TRPV1 Antagonists. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2009;78:211–216. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2009.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang F., Zheng J.. Understand Spiciness: Mechanism of TRPV1 Channel Activation by Capsaicin. Protein Cell. 2017;8:169–177. doi: 10.1007/s13238-016-0353-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson D. M., Dubin A. E., Shah C., Nasser N., Chang L., Dax S. L., Jetter M., Breitenbucher J. G., Liu C., Mazur C., Lord B., Gonzales L., Hoey K., Rizzolio M., Bogenstaetter M., Codd E. E., Lee D. H., Zhang S.-P., Chaplan S. R., Carruthers N. I.. Identification and Biological Evaluation of 4-(3-Trifluoromethylpyridin-2-yl)piperazine-1-carboxylic Acid (5-Trifluoromethylpyridin-2-yl)amide, a High Affinity TRPV1 (VR1) Vanilloid Receptor Antagonist. J. Med. Chem. 2005;48:1857–1872. doi: 10.1021/jm0495071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gavva N. R., Bannon A. W., Surapaneni S., Hovland D. N. Jr., Lehto S. G., Gore A., Juan T., Deng H., Han B., Klionsky L., Kuang R., Le A., Tamir R., Wang J., Youngblood B., Zhu D., Norman M. H., Magal E., Treanor J. J. S., Louis J.-C.. The Vanilloid Receptor TRPV1 Is Tonically Activated In Vivo and Involved in Body Temperature Regulation. J. Neurosci. 2007;27:3366–3374. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4833-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steiner A. A., Turek V. F., Almeida M. C., Burmeister J. J., Oliveira D. L., Roberts J. L., Bannon A. W., Norman M. H., Louis J.-C., Treanor J. J. S., Gavva N. R., Romanovsky A. A.. Nonthermal Activation of Transient Receptor Potential Vanilloid-1 Channels in Abdominal Viscera Tonically Inhibits Autonomic Cold-Defense Effectors. J. Neurosci. 2007;27:7459–7468. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1483-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang S. M., Lee H., Chung M.-K., Park U., Yu Y. Y., Bradshaw H. B., Coulombe P. A., Walker J. M., Caterina M. J.. Overexpressed Transient Receptor Potential Vanilloid 3 Ion Channels in Skin Keratinocytes Modulate Pain Sensitivity via Prostaglandin E2 . J. Neurosci. 2008;28:13727–13737. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5741-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gavva N. R., Treanor J. J. S., Garami A., Fang L., Surapaneni S., Akrami A., Alvarez F., Bak A., Darling M., Gore A., Jang G. R., Kesslak J. P., Ni L., Norman M. H., Palluconi G., Rose M. J., Salfi M., Tan E., Romanovsky A. A., Banfield C., Davar G.. Pharmacological Blockade of the Vanilloid Receptor TRPV1 Elicits Marked Hyperthermia in Humans. Pain. 2008;136:202–210. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2008.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Round P., Priestley A., Robinson J.. An investigation of the safety and pharmacokinetics of the novel TRPV1 antagonist XEN-D0501 in healthy subjects. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2011;72:921–931. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2011.04040.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowbotham M. C., Nothaft W., Duan R. W., Wang Y., Faltynek C., McGaraughty S., Chu K. L., Svensson P.. Oral and Cutaneous Thermosensory Profile of Selective TRPV1 Inhibition by ABT-102 in a Randomized Healthy Volunteer Trial. Pain. 2011;152:1192–1200. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2011.01.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Othman A. A., Nothaft W., Awni W. M., Dutta S.. Effects of the TRPV1 Antagonist ABT-102 on Body Temperature in Healthy Volunteers: Pharmacokinetic/Pharmacodynamic Analysis of Three Phase 1 Trials. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2013;75:1029–1040. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2012.04405.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manitpisitkul P., Brandt M., Flores C. M., Kenigs V., Moyer J. A., Romano G., Shalayda K., Mayorga A. J.. TRPV1 Antagonist JNJ-39439335 (Mavatrep) Demonstrates Proof of Pharmacology in Healthy Men: A First-in-Human, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Randomized. Sequential Group Study. Pain Rep. 2016;1:e576. doi: 10.1097/PR9.0000000000000576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garami A., Shimansky Y. P., Rumbus Z., Vizin R. C. L., Farkas N., Hegyi J., Szakacs Z., Solymar M., Csenkey A., Chiche D. A., Kapil R., Kyle D. J., Van Horn W. D., Hegyi P., Romanovsky A. A.. Hyperthermia Induced by Transient Receptor Potential Vanilloid-1 (TRPV1) Antagonists in Human Clinical Trials: Insights from Mathematical Modeling and Meta-Analysis. Pharmacol. Ther. 2020;208:107474. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2020.107474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y.-Z., Ma J.-X., Bian Y.-J., Bai Q.-R., Gao Y.-H., Di S.-K., Lei Y.-T., Yang H., Yang X.-N., Shao C.-Y., Wang W.-H., Cao P., Li C.-Z., Zhu M. X., Sun M.-Y., Yu Y.. TRPV1 Analgesics Disturb Core Body Temperature via a Biased Allosteric Mechanism Involving Conformations Distinct from That for Nociception. Neuron. 2024;112:1815–1831. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2024.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamayo N., Liao H., Stec M.. et al. Design and Synthesis of Peripherally Restricted Transient Receptor Potential Vanilloid 1 (TRPV1) Antagonists. J. Med. Chem. 2008;51:2744–2757. doi: 10.1021/jm7014638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazlauskas R. J., Weissfloch A. N. E., Rappaport A. T., Cuccia L. A.. A Rule to Predict Which Enantiomer of a Secondary Alcohol Reacts Faster in Reactions Catalyzed by Cholesterol Esterase, Lipase from Pseudomonas cepacia, and Lipase from Candida rugosa . J. Org. Chem. 1991;56:2656–2665. doi: 10.1021/jo00008a016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gomtsyan, A. ; Daanen, J. F. ; Gfesser, G. A. ; Kort, M. E. ; Lee, C.-H. ; McDonald, H. A. ; Puttfarcken, P. S. ; Voight, E. A. ; Kym, P. R. . TRPV1 Antagonists. US20120245163A1, 2012.

- Chen B.-S., de Souza F. Z. R.. Enzymatic Synthesis of Enantiopure Alcohols: Current State and Perspectives. RSC Adv. 2019;9:2102–2115. doi: 10.1039/C8RA09004A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank, R. ; Bahrenberg, G. ; Christoph, T. ; Schiene, K. ; De Vry, J. ; Damann, N. ; Frormann, S. ; Lesch, B. ; Lee, J. ; Kim, Y.-S. ; Kim, M.-S. . Substituted Aromatic Carboxamide and Urea Derivatives as Vanilloid Receptor Ligands. WO2010127855A1, 2010.

- Takano S., Suzuki M., Ogasawara K.. Enantiocomplementary preparation of optically pure 2-trimethylsilylethynyl-2-cyclopentenol by homochiralization of racemic precursors: a new route to the key intermediate of 1,25-dihydroxycholecalciferol and vincamine. Tetrahedron Asymmetry. 1993;4:1043–1046. doi: 10.1016/S0957-4166(00)80151-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X., De Clercq P. J., Gawronski J.. Synthesis of enantiomerically pure (R)- and (S)-3-methyl-2-cyclopenten-1-ol. Tetrahedron Asymmetry. 1995;6:1551–1552. doi: 10.1016/0957-4166(95)00196-V. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hoye T. R., Jeffrey C. S., Shao F.. Mosher Ester Analysis for the Determination of Absolute Configuration of Stereogenic (Chiral) Carbinol Carbons. Nat. Protoc. 2007;2:2451–2458. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C. S., Fujimoto Y., Girdaukas G., Sih C. J.. Quantitative analyses of biochemical kinetic resolutions of enantiomers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1982;104:7294–7299. doi: 10.1021/ja00389a064. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nahm S., Weinreb S. M.. N-Methoxy-N-Methylamides as Effective Acylating Agents. Tetrahedron Lett. 1981;22:3815–3818. doi: 10.1016/S0040-4039(01)91316-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kunishima M., Kawachi C., Hioki K., Terao K., Tani S.. Formation of carboxamides by direct condensation of carboxylic acids and amines in alcohols using a new alcohol- and water-soluble condensing agent: DMT-MM. Tetrahedron. 2001;57:1551–1558. doi: 10.1016/S0040-4020(00)01137-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this study are available in the published article and its online Supporting Information.