Abstract

Recently, T cells expressing engineered T cell receptor (TCR-T cells) have become recognized as a promising tumor cell therapy for solid tumors because of their ability to selectively kill tumor cells with less destruction of other cells and their high safety when used as autologous T cells. Several studies and clinical tests have been conducted to demonstrate its potential as a novel therapy. However, previous research has mainly focused on antigens; these common targets for TCR-T are tumor-associated antigens, which exhibit expression not only in tumor cells but also in normal cells, resulting in off-target risk and not considering the heterogeneity of different patients. In contrast, neoantigens offer superior specificity as they are uniquely expressed on tumor cells due to genomic alterations. Given the frequent occurrence and notable role of genetic mutations in tumorigenesis and tumor progression, identification and targeting of neoantigens is a valuable therapeutic direction. This perspective delves into various antigen classifications, including their characteristics and advantages, as well as strategies for identifying and validating neoantigens that have emerged from numerous research studies. These insights are crucial for guiding the search for new neoantigens. We also review significant and representative studies involving TCR-T and other immunotherapies that target neoantigens to assess the therapeutic effectiveness of TCR-T therapy. Moreover, we discuss the challenges and complexities inherent in TCR-T therapy and propose potential solutions for these issues. In this perspective, we aim to provide fresh perceptions and strategies for cancer treatment by highlighting the potential of TCR-T and exploring its challenges and future directions. It also seeks to propel the development of precision medicine and personalized therapy, offering hope for more effective and targeted cancer treatments in the future.

Keywords: TCR-T, CAR-T, Immunotherapy, Neoantigen

1. Introduction

Over the past ten years, immunotherapy has brought about a paradigm shift in the therapeutic strategies employed for cancer treatment. Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), including cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen-4 (CTLA-4) and programmed cell death-1 (PD-1), have made remarkable strides in clinical applications for melanoma, non–small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC), and various other oncological conditions.1,2 Adoptive cell transfer (ACT) has risen to prominence as a pivotal platform within the realm of cancer therapeutics that extracts a patient’s cells, modifies them into specific antigen-specific cells, and transfuses them back into patient with greater endogenous response and higher security. Cellular immunotherapy, exemplified by chimeric antigen receptor T-cells (CAR-T) and T cell receptor-engineered T-cells (TCR-Ts), has attracted considerable attention in tumor therapy research because of its ability to accurately recognize and eliminate tumor cells. The number of cell immunotherapy clinical trials entered into the US Clinical Trials website increases annually. CAR-T therapy has shown notable response rates in patients with acute B-cell lymphoblastic leukemia,3 non-Hodgkin lymphoma,4 and multiple myeloma.5 Several CAR-T products targeting hematological malignancies have obtained approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). However, CAR-T therapy has limitations in solid tumors because it can only target antigens expressed on the cell surface, rather than those antigens presented by major histocompatibility complex (MHC) represent only a minor proportion of natural antigens. In addition, antigen stimulation is required for the synthetic receptor, constraining its application to solid tumors. TCR-T has emerged as a promising therapy for solid tumors because it is a natural receptor that can recognize more antigens, and less epitope density is needed for stimulation,6 which can improve tumor detection and killing.7

Selection of the appropriate antigen holds paramount importance in determining the effectiveness and safety profile of TCR-T therapy. The ideal antigen which is expressed only in tumor cells, can generate epitopes with MHC molecules on the cell surface, inducing a specific immune response to the tumor. Early studies focused on tumor-associated antigens (TAAs) that are commonly expressed, as they can be applied to various patients. However, TAAs present safety risks due to their expression in normal tissues.8 More recent studies have explored tumor-specific antigens (TSAs), alternatively termed neoantigens. These antigens are expressed exclusively in tumor cells and are associated with fewer off-target toxicities and better therapeutic windows.9,10 The identification of additional neoantigens can significantly expand the repertoire of targetable antigens for immune therapies. This perspective introduces the different types and characteristics of antigens used in targeted therapy, a common method for discovering neoantigens, and summarizes existing TCR-T studies on neoantigens and TAAs. We aimed to provide guidance for current experiments while highlighting challenges associated with neoantigens and TCR-T therapy, thus offering directions for future research.11

2. Antigen presentation and TCR recognition

2.1. Antigen presentation

The presentation of neoantigen mainly includes the following two types: The first one is through the major histocompatibility complex (MHC)-I presentation route. The neoantigen proteins inside tumor cells undergo proteasomal degradation to generate smaller peptides (typically 8–12 amino acids in length). These peptides are then transported to the endoplasmic reticulum, where they are recognized and loaded with MHC-I molecules. MHC-I is expressed on almost all nucleated cells and is mainly responsible for presenting endogenous peptides. The resulting MHC-I-peptide complexes are presented on the surface of tumor cells, where they can be recognized by CD8+ cytotoxic T cells, thereby initiating an antitumor immune response.12 The second way is through MHC-II molecules, which is generally expressed on specialized antigen-presenting cells (APCs) and can recognize both exogenous and endogenous peptides acquired through secretion and endocytosis, such as neoantigen proteins released extracellular. While MHC II molecules typically bind longer peptides (13–25 amino acids), they exhibit greater flexibility in peptide binding requirements compared to MHC class I. This structural flexibility increases the likelihood of neoantigen presentation through the MHC class II pathway, enabling recognition by CD4+ helper T cells which assume pivotal roles in orchestrating adaptive immune responses.13

APCs play a key role in training T and B cells to mature, presenting antigens, and inducing immunity. Typical APCs include dendritic cells (DCs), macrophages, and B cells. DCs primarily engage in the uptake of soluble antigens and receptor-mediated apoptotic vesicles, whereas macrophages typically ingest these via cytophagocytosis or Fc receptor-mediated uptake of immune complexes. A special class of antigen presentation occurs in lymph node-resident DCs, which specialize in presenting soluble antigens from lymphatic vessels excreted by tumor tissues or actively transferred by migrating APCs,14 mainly for training the development and maturation of T and B cells. DCs can also transport endocytosed antigens to cytoplasmic compartments for proteasomal degradation and subsequent presentation to MHC molecules, which is known as “cross-presentation,” is vital for initiating and stimulating cytotoxic CD8+ T cells with specific antigen-targeting ability.15

2.2. Classification of antigens

Over recent years, there has been a growing number of research focused on tumor-related antigens. There are many classifications of tumor antigens and we have sorted out the common classifications below.

2.2.1. Tumor associated antigens

Tumor associated antigens (TAA) are not only overexpressed in tumor cells but also in some normal tissues. TAA have been used as therapeutic targets in many previous studies because many TAAs have been identified and are widely expressed in patients.16,17 However, owing to its expression in normal tissues, it also faces the problem of off-target effects, and highly specific T cells are screened for thymic negative selection, resulting in the problem of central T cell tolerance. TAA is mainly divided into two categories: cancer germline antigens (CGA) and tumor differentiation antigens (TDA). CGA are a class of antigens that are not normally expressed or are expressed at very low levels in normal tissues. They are usually expressed in germ cells or specific tissues, such as testicles, but are reactivated in tumor cells in some cancers to regulate gene expression.18 CGAs include a variety of proteins such as NY-ESO-1, expressing in many kinds of cancer, including melanoma, lung cancer, and ovarian cancer.19 CGAs offer several advantages as immunotherapeutic targets. First, owing to their limited expression in normal tissues, immune responses against CGAs may have a low risk of toxicity.20 Secondly, CGAs are often expressed in multiple cancer types, which means that therapies targeting CGAs may have broad applicability.21 However, some researches revealed that CGAs exhibit heterogeneity expression within tumors, which may pose a limitation to their potential therapeutic effectiveness when a single CGA is targeted.22

Except for the CGA, there are other antigens like AFP and GPC3 express and play important role in fetus and gradually downregulate after birth and become undetectable in healthy adults, which is specific tumor antigens. On the basis, many research about TCR-T therapy on these target are in development. Zhu et al. constructed TCR-T cell targeted AFP which can recognize AFP+ HepG2 HCC tumor cells and generated effector cytokines without substantial toxicity to normal primary hepatocytes in vitro. Researches also found that HepG2 tumors in NOD-scid-Il2Rg null mice were effectively eradicated through the adoptive transfer of AFP-specific TCR-T cells.23 What’s more, Docta et al. used in vitro mutagenesis and screening generated a TCR that recognizes the HLA-A*02-restricted AFP158–166 peptide and evaluated peptide specific TCR-T cells by testing their activity against both normal and tumor cells. A important test is TCR-T cell’s safety test, including alanine scan to confirm its specifity, off-target test finding that only one-eighth of the pericerebrovascular cell lines and one-half of the thyroid fibroblast cell lines showed weak responses, and in autologous blood experiments, AFPc332T cells which specifically recognize AFP158–166 peptide presented by HLA*A02:01 did not induce the release of any cytokines.24

Dargel et al. cloned GPC3-specific T cells and found TCR-T cells demonstrated ability to eliminate GPC3-expressing hepatoma cells in vitro and significantly inhibited the growth of HCC xenograft tumors in mice.25 Vercher et al. recognized GPC3 epitope, identified 3 GPC3-TCR and engineered TCR-T. The studies showed that TCR-T effectively recognized GPC3+ human HCC cells with effector functions and therapy efficacy in xenograft HCC models. Except for TCR-T, there are also some research found locoregional delivery of GPC3-targeted CAR-T cells through portal vein which showed better control of tumor growth and better liver function.26

HER2 is a transmembrane tyrosine kinase receptor and activated downstream signaling pathway to promote cell proliferation and survival.27 HER2 is overexpressed in breast cancers and other HER2-expressing malignancies such as gastric carcinoma and acute B lymphoblastic leukemia.28 A research selects HER2 TCR clonotypes and assess these TCR’s antitumor activity in vitro, it was found that the cytotoxicity of cells expressing the specific TCR was significantly increased.29 There is a retained cross-reactivity of HER2-reactive TCR with HER3 and HER4 which shows a wide range of recognition skills but maybe potential off-target risk.30

Another type of TAA is TDA, which are expressed in both cancer cells and their normal tissue counterparts, albeit often at lower levels in healthy tissues. These antigens are typically involved in cell differentiation and lineage-specific functions. While TDAs offer potential targets for immunotherapy, their shared expression with normal tissues raises concerns about on-target/off-tumor toxicity. Melanoma antigen recognized by T cells-1 (MART-1) is a well-characterized TDA predominantly expressed in melanocytes and >90% of melanoma cases. It plays a role in melanin synthesis and serves as a biomarker for melanoma. Early clinical trials used MART-1-specific TCR-engineered T cells, demonstrating tumor regression in metastatic melanoma patients.31

2.2.2. Tumor specific antigens

Alternatively, tumor specific antigens (TSA) exhibit specific expression on tumor cells because they are produced due to genomic alteration events such as gene mutations or viral infection in tumor cells and has good specificity.11 Therapies targeting these targets are highly safe due to thymic negative selection. T cells that exhibit high affinity and are specific to these neoantigens will avoid elimination and can be separated from patients' tumor tissues or the peripheral blood of healthy individuals. TSA are mainly divided into neoantigens and viral antigens.

The neoantigens produced by mutations are called mutation-associated neoantigens and are produced by nonsynonymous mutations associated with the initiating genetic event or overall genetic instability of the cancer. Common novel epitopes are derived from common mutational driver genes (such as TP53 and KRAS) that are shared between different patients with specific human leukocyte antigen (HLA) alleles. TCR-Ts targeting these public neoantigens are currently being tested in clinical trials, and many experiments have found that specific TCR-Ts have good cell destruction and therapeutic effects, which will be described in detail in the following section of clinical progress.32

Another significant contributor to the generation of neoantigens is alternative splicing. mRNA splicing can generate many variants and protein isoforms from one gene sequence in normal cells. However, if mutation in splicesome or other regulatory elements, selective splicing may happen and result in neoantigen appearance. Intron retention, a consequence of splicing misregulation, results in the presence of an intron within the mature mRNA transcript, which is frequently observed in tumor transcriptomes. If intron retention are translated and presented on MHC molecular, they can produce neoantigens. In hematological malignancies, frequent spliceosomal components mutations, such as SRSF2 and SF3B1 enhance the production of splicing variant mRNAs, resulting in the translation and expression of neoantigens.33 What’s more, mutated splicing patterns in SF3B1 in melanoma generate shared tumor-specific neo-epitopes.34 Another important way of production of neoantigen is abnormal sense-mediated RNA decay (NMD) function, such as mutations in the NMD factor UPF1 are commonly found in pancreatic and lung adenocarcinomas, leading to increased levels of aberrant transcription and neoantigen generation.35 A comprehensive analysis of alternative splicing in 8705 patients found that about 930 neojunctions in tumors, which can be transplanted into peptides and presented on MHC as neoantigens.36 To sum up, alternative splicing is a important source to produce neoantigen from these studies.

In addition to cancers caused by mutations, some TSA caused by viral infections are foreign proteins encoded by viruses that are not present in normal tissues, such as those induced by the human papillomavirus (HPV), hepatitis B virus (HBV), and Merkel cell polyomavirus (MCPyV). HPV is a highly prevalent and dangerous virus that can induce cervical cancer, head and neck cancer, and other malignant tumors. E6 and E7 are key oncogenes and have become relevant therapeutic targets. In the first trial using TCR-Ts targeting HPV16-E6, 17% of the patients reported a clinical response with no significant toxicity.37 Studies targeting other viral antigens are currently in progress. Recently, some TCR-T research for HBV-related hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)38 and McPyV-specific TCR-Ts for metastatic Merkel cell carcinoma,39 both showed partial responses, suggesting that TCR-T therapy targeting virus-associated neoantigens has the potential to treat virus-associated cancers; however, further research is needed to optimize and validate its effects. We have also listed the clinical trials that have been conducted for different tumor antigens in Table 1.

Table 1.

Different types of antigens tested in clinical trials and their oncology indications.

| Antigen class | Target antigen | Epitope | Cancer type | Clinical trial | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TDA | MART-1 | AAGIGILTV | Melanoma | NCT00509288 | 31 |

| EAAGIGILTV | Melanoma | NCT00910650 | 40 | ||

| Neoantigen | TP53 | HMTEVVRHC | Metastatic breast cancer | NCT03412877 | 41 |

| KRAS G12D | GADGVGKSA | Metastatic pancreatic Cancer |

IND 27501 | 9 | |

| CGA | NY-ESO-1 | SLLMWITQC | Melanoma Synovial sarcoma |

NCT00670748, NCT02070406, NCT01697527 | 42 |

| MAGE-A3 | KVAELVHFL | Melanoma | NCT01273181 | 43 | |

| Synovial sarcoma | |||||

| Esophageal cancer | |||||

| EVDPIGHLY | Melanoma | NCT01350401, NCT01352286 | 44 | ||

| MAGE-A4 | NYKRCFPVI | Esophageal cancer | UMIN000002395 | 45 | |

| GVYDGREHTV | Advanced solid tumor | NCT03132922 | 46 | ||

| MART-1 | EAAGIGILTV | Melanoma | NCT00910650 | 40 | |

| Viral antigen | HPV16-E6 | TIHDIILECV | HPV16-positive epithelial cancer | NCT02280811 | 37 |

| MCPyV | KLLEIAPNC | Merkel cell carcinoma | NCT03747484 | 47 |

Abbreviations: CGA, cancer germline antigens; HPV16-E6, human papillomavirus type 16 E6 protein; MAGE, melanoma-associated antigen; MART-1, melanoma antigen recognized by T cells-1; MCPyV, Merkel cell polyomavirus; NY-ESO-1, New York esophageal squamous cell carcinoma 1; TDA, tumor differentiation antigens.

3. Neoantigens identification, prediction, and validation

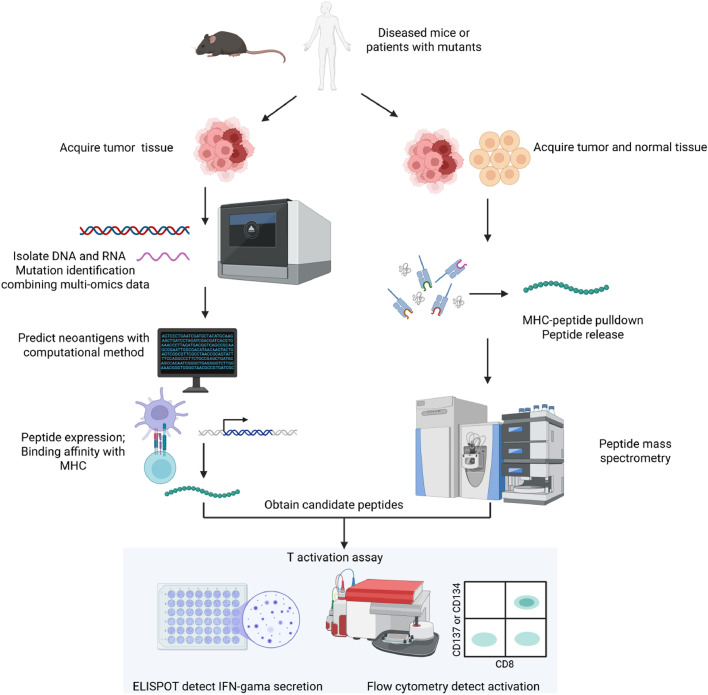

The standard workflow for neoantigen prediction comprises several sequential steps. Initially, mutations are identified. Subsequently, HLA typing is carried out. After that, a screening process is implemented. Next, neoantigens are prioritized according to their HLA-binding affinity and immunogenicity. Finally, immunogenic neoantigens undergo experimental validation through T cell response analysis (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Typical workflow of neoantigens identification and validation. Neoantigen identification and validation are typically conducted through two follwing method. The first approach involves isolating DNA and RNA from patient-derived tumor tissues and leveraging multiomics data to identify mutations. Subsequently, computational methods or artificial intelligence tools are employed to predict neoantigens. Following this, candidate peptides are synthesized and their binding affinity to MHC molecules is assessed to confirm their potential as neoantigens.The second method is based on the identification of peptides present in both tumor and normal tissues from patients. This approach utilizes HLA antibodies to pull down the peptide-MHC complex, followed by elution to release the peptides. Peptide mass spectrometry is then applied to determine the sequence of the released peptides. In the experimental validation of peptides, a robust method involves co-culturing T cells with the synthesized peptides in the presence of antigen-presenting cells. The degree of T cell activation is assessed using IFN-γ ELISPOT assays and the expression of CD137 on T cells is measured by flow cytometry. ELISPOT, enzyme-linked immunospot assay. Figure adapted from images created with BioRender.com.

3.1. Identification of mutation type

The first step in finding neoantigens is to identify the types of mutations that occur and then look for potentially viable peptide neoantigens based on the mutations. Current techniques have been further developed to combine a variety of omics data, such as whole exon sequencing (WES), high-throughput sequencing techniques, RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq), and proteomic data, to compare genetic data from tumor and normal tissues from the identical patient to identify the types of mutations that occur.48

WES is regarded as the recommended option for next-generation sequencing (NGS) data in the context of neoantigen prediction, for its capacity to achieve the highest level of mutation coverage by concentrating on the protein-coding segments of the genome.49 Moreover, combining RNA-seq data with WES data enables the determination of the expression status of mutated genes in tumors.

3.2. HLA typing

HLA molecules are a group of important molecules located on the surface of human cells. HLA molecules can be divided into three main categories: Class I, II, and III. Class I includes HLA-A, HLA-B, and HLA-C, which are expressed on the surface of almost all nucleated cells and present endogenous antigens (such as viral or tumor antigens) to CD8+ T cells, thereby activating the immune response of cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs). Class II HLA molecules include HLA-DP, HLA-DQ, and HLA-DR, which are mainly expressed on the surface of professional APCs (such as B cells, macrophages, and DCs).50 The main function of HLA Class II molecules is to present exogenous antigens (such as bacterial or parasitic antigens) to CD4+ T cells and activate the immune response of helper T (Th) cells. HLA Class III molecules include some complement components (such as C2, C4) and cytokines (such as tumor necrosis factor TNF-α), which play a role in the inflammatory response and other immune regulatory processes. Humans have more than 24,000 different alleles of HLA-I and HLA-II, resulting in diverse HLA molecules and a distinction between the peptides recognized by different HLA molecules.51 The HLA type determines the type of tumor-specific peptide that can be recognized by T cells; therefore, it is necessary to identify the type of HLA. Generally, NGS data are analyzed and HLA-I types are identified using OptiType and Polysolve.

3.3. Prediction of neoantigen expression, binding with HLA, and immunogenicity

The process by which neoantigens cause an immune response mainly includes the following steps: transcription, translation to processing, and degradation of abnormally mutated genes. These neoantigens are then presented by MHC molecules and are subsequently recognized and targeted by T cells. Therefore, the results of these important steps should also be integrated to predict and sequence neoantigens. It is worth mentioning that, as the development of artificial intelligence, deep learning-based tools have become a common and indispensable method to predict neoantigen. These methods not only can consider from one step of peptide presentation but also can integrate all steps to give comprehensive results, which show great power in predicting neoantigens.

3.3.1. Transcript expression

The transcription level of a mutated gene directly influences the abundance of its encoded peptide, which in turn determines the quantity of peptide-MHC complexes presented on the cell surface. Some studies have found that downregulation of the expression of neoantigens serves as a mechanism of immune evasion.52 Even if the affinity between the peptides and MHC molecules is low, sufficient peptide expression can compensate for this and generate sufficient peptide-MHC complexes. Consequently, numerous studies rank neoantigens based on their expression levels.53 This approach also opens the possibility of expanding potential targets by including antigens with low transcript levels.

3.3.2. MHC binding and affinity

The combination of peptides and MHC molecules is a vital step for antigen presentation. Consequently, numerous studies based on machine learning and artificial intelligence have been developed to predict binding affinity with a primary focus on MHC Class I. Notable tools include NetMHCpan,54 NetCTL, and NetCTLpan.55 These tools, trained on experimental data, such as binding affinity experiments and mass spectrometry (MS) analyses of eluted ligands, significantly improve prediction performance through computational algorithms. Recently, a benchmark study used receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC) curves to analyze the prediction of different tools and found that NetMHCpan and MHC flurry56 achieve the best areas under the ROC. Prediction tools for MHC-II are less precise for MHC-I because of the less stringent nature of MHC-II interactions with peptides, which is attributed to their broad and more flexible peptide lengths and binding motifs. A collection of computational methods aimed at forecasting epitopes that bind to major MHC-II have been formulated through the application of artificial neural networks, including NetMHCII, ProPred, MHC-Pred, and SYFPEITHI. The prediction of MHC-II is more complicated regarding peptide length, binding sequence motif, and polymorphism of the alpha and beta chains.57

In addition to binding affinity, some tools such as NetChop and NetCTL predict proteasomal cleavage and transport into the endoplasmic reticulum by the transporter associated with antigen processing protein (TAP) protein complex, which represent a crucial initial step in antigen processing before loading onto MHC molecules. However, because the approaches for predicting MHC presentation were developed based on ligand elution from MHC that have already undergone these early processing steps, the utility of integrating predictions for cleavage, transport, and binding remains debatable.

3.3.3. Prediction of immunogenicity

Even if a peptide has high expression and binding affinity for MHC, it is possible that the MHC-peptide complex cannot be recognized by T-cells or induces T-cell responses. Therefore, accurate prediction of immunogenicity is crucial. Recent tools have emerged to predict immunogenicity, such as BigMHC,58 which employs transfer learning from the BigMHC EL (presentation) domain to the BigMHC IM immunogenicity domain. BigMHC IM was evaluated using PPVn, the proportion of the top n predicted peptide-MHCs (pMHCs) that were immunogenic. It achieved a mean PPVn of 0.4375, significantly surpassing the best prior method, HLA, which ranks. This finding highlights the effectiveness of transfer learning in this context.

3.3.4. AI-driven neoantigen prediction

AI tool can also integrate all steps of peptide presentation into consideration and give more comprehensive and overall prediction. pVAtools combined mutation frequence, gene expression level and MHC affinity information, predicted neoantigens from TCGA dataset from 100 cases of each of melanoma, HCC, and lung squamous cell carcinoma and got 42% more neoantigen candidates. After screening and filtering, pVAtools obtain an average of 16 neoantigens per patient and retain the positive peptide validated in experiment.59 There have also been studies that have built a pepiline using DNA, RNA sequencing and mass spectrometry, which can easily used by researchers. For example, NeoDisc combines publicly available and in-house software for immunopeptidomics, genomics and transcriptomics for identification and prediction of neoantigens. The researchers illustrate NeoDisc prioritization on cervical adenocarcinoma and the result show that six immunogenic peptides within top ten and two confirmed immunogenic neoantigens in the cervical adenocarcinoma (CESC) tumor MS immunopeptidomic data.60

In addition, other potentially relevant biological characteristics, such as the differential agretopicity index61 and similarity between mutated and wild-type antigens, were incorporated into the algorithm to rank neoantigen candidates. These algorithms incorporate characteristics that could influence the effectiveness of the newly proposed epitope candidates in activating T cells. This is in contrast to autoantigens, which are examined for sequence homology. Additionally, these features may affect the probability of immune escape by the emergence of antigen-deficient variants. For instance, the clonality of mutations determined through DNA sequencing data analysis and driver mutations identified via database searches are considered.

3.4. Immunopeptidomics-based verification of the mutant peptide

Beyond the computational tools that predict binding affinity and immunogenicity, MS remains the most direct method to identify mutant peptides bound to cellular MHC and find true neoepitopes because it can detect the existing MHC-peptide complex in vivo. Recent advancements in MS technology have increased sensitivity, enabling the detection of neoantigens from fewer cells. Bassani-Sternberg et al. used advanced MS analysis to survey melanoma-associated immunopeptidomes and identified somatic mutation-related peptide ligands present in tumor tissue, with four out of 11 ligands inducing a T-cell response.62 In addition, MS has been integrated with NGS to enhance the detection of tumor-specific neoantigens arising from somatic mutations, noncoding RNAs and proteasome splicing. This combination addresses the limitations of traditional whole-exome or RNA sequence methods, which may miss certain neoantigens.

3.5. Validation of immunogenicity of candidate neoantigens

Neoantigens selected using computational tools must be validated through experimental methods, which can be broadly categorized into in vivo and in vitro approaches. In vivo validation often involves the transplantation of patient-derived tumor xenografts into humanized mice. This approach ensured that tumors derived directly from human samples and not cultured in vitro retained the characteristics and phenotypic traits of the original tumors.63

For in vitro methods, measuring T cell response is a direct approach to assess the immunogenicity of candidate neoantigens. After T cell stimulation by neoantigen peptides, response activity can be quantified by flow cytometry, focusing on T cell activation protein markers expressed on the cell surface, such as 4–1BB (CD137) and OX-40 (CD134). Additionally, the ELISPOT assay can be employed to detect IFN-γ secretion by T cells following stimulation. This highly sensitive method evaluates single-cell cytokine secretion by capturing cytokines with specific antibodies to form spots that reflect both the cytokine content and the immunogenicity of the neoantigen.64

T cell stimulation can be achieved through antigen-presenting cell (APC)-dependent mechanisms that are widely employed in neoantigen validation studies. A standard approach involves pulsing APCs (such as dendritic cells or B cells) with candidate peptides, followed by co-culture with T cells. Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) from patients or tumor-bearing mice are particularly valuable for such assays, as their T cell receptors (TCRs) have undergone in vivo selection and can readily recognize peptide-MHC complexes. The reactivity of antigen-specific T cells is typically evaluated using IFN-γ ELISPOT and flow cytometry to quantify activation markers (e.g., CD69, CD137) and cytokine production.65

4. TCR identification: from known epitopes to specific TCR sequence

Specific neoantigens can trigger the generation of the corresponding TCR and T-cell responses. It is crucial to identify the specific TCR sequence that recognizes antigens. However, identifying an epitope-specific T-cell receptor is highly intricate because of the vast diversity of the TCR and antigen repertoires and the intricate nature of the interactions between the TCR and pMHC. Some common technical methods for TCR identification and their associated challenges are as follows:

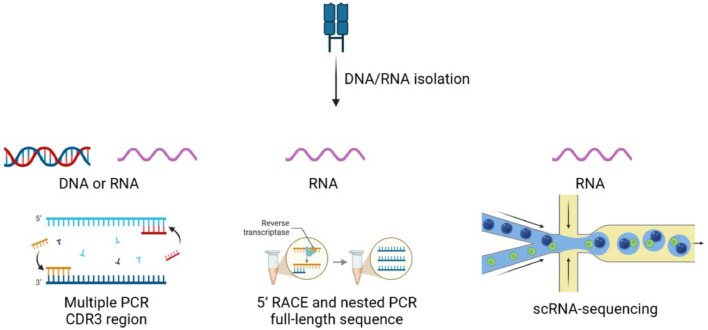

4.1. TCR sequencing

The TCR consists of two main types of receptors: the α–β chain receptor and the γ–δ chain receptor. Approximately 95% of human T lymphocytes carry the α–β chain receptor, which recognizes peptides presented by MHC molecules. The remaining 5% carry the γ–δ chain receptor, which is not restricted by MHC molecules and can recognize a broader range of molecules, including lipids and possibly other nonpeptidic antigens. Due to their prevalence and role in recognizing peptides via MHC, research typically focuses on sequencing the α–β chain receptor T cells.66

The general idea of TCR sequencing involves obtaining cDNA by reverse transcription from T cell transcription products, amplifying the α–β chain receptor regions via polymerase chain reaction (PCR), and sequencing the TCR fragments (Fig. 2). However, the VDJ rearrangement during T cell development introduces significant variability in the 5’ gene region of the TCR, complicating the amplification of the corresponding fragments. To address these challenges, new PCR techniques have been developed, with two of the most widely used methods being 5’ rapid amplification of cDNA ends (RACE) and multiplex PCR.67 5’ RACE refers to the design of primers according to sequence specificity in the case that the 5’ terminal sequence is unknown, and finally obtain the complete cDNA sequence. Multiplex PCR uses multiple pairs of primers, each of which binds to a different template region to enhance amplification specificity. One significant challenge in TCR sequencing arises from the cleavage of T cell expression products, leading to the separation of the α and β chains. This results in the mixing of TCR chains from different cells, making it difficult to pair the two chains correctly. To address this problem, several strategies have been developed.

-

(1)

Single-cell RT-PCR: Individual T cells are sorted by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) into wells containing reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) reaction buffers, and the TCRα and β chains of each cell are amplified by RT-PCR.68 This method eliminates the necessity of expanding T-cell clones following the isolation of specific T cells, consequently diminishing the time and effort needed to propagate a single T-cell clone. Nevertheless, this method does not currently allow for the analytical evaluation of the antigen specificity of the analyzed cells.

-

(2)

Single-cell RNA sequencing: It is a novel and effective platform for analyzing TCR and obtaining antigen-specific information about T cells. Recent studies have successfully utilized this technique by performing RNA-seq experiments on peptide-stimulated T cells. This approach enables researchers to pinpoint antigen-specific T cells based on elevated expression levels of effector cytokines, such as IFN-γ and TNF-α. The transcripts of the TCR α and β chains can then be obtained from these activated cells.69 Although this method is highly specific and rapid, it involves complex technical operations.

Fig. 2.

Illustration of TCR sequencing. The process begins with the extraction of DNA or RNA from biological samples. CDR3 of the TCR is amplified using multiple PCR which can be used for both DNA and RNA. This region is highly variable and is critical for TCR function as it directly interacts with pMHC. RNA samples are particularly suitable for RACE followed by nested PCR to obtain the full-length sequence of the TCR. Single-cell RNA sequencing can be also performed to get TCR sequence from RNA sample. CDR, complementary determining region; PCR, polymerase chain reactions; RACE, 5′ rapid amplification of cDNA ends; scRNA, single-cell RNA. Figure adapted from images created with BioRender.com.

4.2. Strategy for selecting specific T cell

Following the enrichment of polyclonal T cell products to achieve the desired specificities, the isolation of antigen-specific T cells from the bulk T cell population becomes a pivotal step. A widely adopted approach is predicated on T-cell functional analysis.

In this strategy, T cells are first stimulated with a specific peptide to trigger an immune response. Subsequently, antigen-responsive T cells are isolated based on the elevated expression of molecules linked to T cell activation. For instance, 4–1BB is upregulated in CD8+ T cells and OX40 in CD4+ T cells upon activation. This procedure entails antibody staining of transmembrane proteins that experience transient upregulation after T-cell stimulation. As a result, these cells can be separated using fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) or magnetic bead separation techniques. However, this method is contingent on normal T cell functionality and may not be applicable to tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) with compromised function. An alternative isolation technique focuses on the production of interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) by activated T cells.

In this approach, IFN-γ secreted by T cells is captured on the cell surface using cytokine-specific catch reagent, enabling the selective identification and isolation of actively secreting T cells via either magnetic separation or flow cytometry.70 This method can effectively identify and isolate effector T cells based on their functional responses to antigen exposure.

4.3. Observation platform

Previous method to select specific T cells and analyze their function is largely based on assessing the activity of entire cell population and single activate marker. Many deeper and individual analysis are needed urgently to understand T cells better. Berkeley Lights, Inc. developed a light-fluid system called lightning, which is capable of precisely visualize phenotype and perform functional analysis of individual cell over short periods. The system utilizes a small silicon chip to isolate and culture cells using microfluidic technology, allowing for rapid cloning, growth, analysis, and recycling of 1000 single cells simultaneously in short days, which is a significant improvement over traditional methods that can take months. This platform can load T cells alongside other cell types, which allows for the evaluation of cell-cell interactions, cell surface phenotypes, cytotoxicity, and cytokine secretion, providing a comprehensive understanding of individual cell functions. By leveraging this system, researchers can visually document experiments, observe phenotypic responses, perform functional analysis without cell’s destruction, identify target cells that exhibit reactive behaviors, and subsequently integrate this information with downstream sequencing data to identify specific TCR sequences. There are already many studies using this platform,which illustrate its effectness.71

5. New clinical progress in TCR-T therapy targeting neoantigen

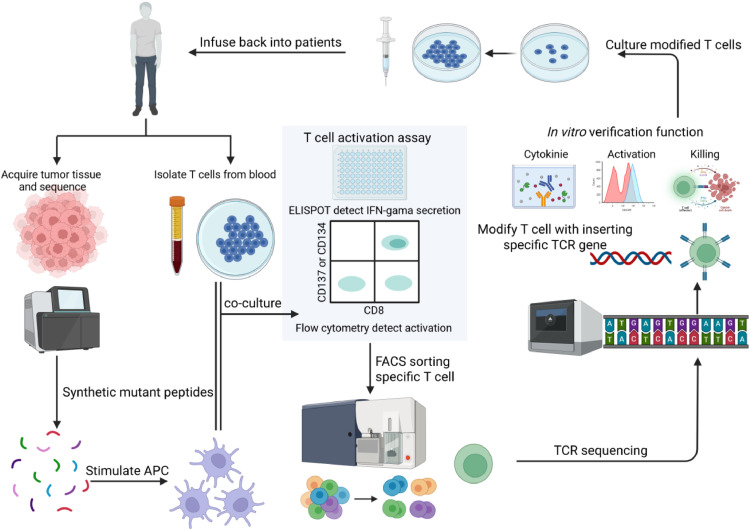

5.1. Workflow and overview of neoantigen targeting TCR-T in clinic

The individual neoantigen-specific TCR-T therapy workflow included neoantigen screening and the generation of neoantigen-specific TCR-Ts, as already described (Fig. 3). On one hand, the tumor tissues are acquired for the isolation of DNA, RNA, and other samples, which are then used to perform WES and RNA-seq. This analysis identified mutation events in the patients and generated candidate mutant peptides. As for neoantigen targets, researchers and can get the candidate antigen list with AI prediction tools and T-cell activation experiment to test its immunogenicity, so they can analyze comprehensively the result of prediction and experiment to get the best neoantigen. On the other hand, T cells are obtained from the patient’s tumor and blood, and co-cultured directly or indirectly with peptide-stimulated APCs. Next, we sorted neoantigen-responsive T cells using an assay of T cell activation markers and used single-cell TCR-seq to obtain the exact TCR sequence. For TCR selection, researchers always identify several TCR sequence from specific T cell population, then use TCR which had been reported to have a good effect in previous experiments or conduct in vitro and in vivo experiments to confirm its recognition ability, destruction and safety. On the basis, TCR plasmids were designed and inserted into T cell genes to generate TCR-Ts. TCR-Ts were cultured and expanded in vitro to an appropriate numbers. Prior to T cell infusion, patients were administered moderate intensity chemotherapy or other adjuvant therapies to enhance the therapeutic effect of TCR-Ts. Subsequently, engineered TCR-Ts were infused into patients to observe their responses and evaluate their clinical effectiveness as well as any associated adverse effects.

Fig. 3.

Preparation workflow of neoantigen specific TCR-T. The process begins with the acquisition of tumor tissue from patients, followed by sequencing to identify mutations. Synthetic mutant peptides are generated based on these mutations and used to stimulate APCs, which are then co-cultured with T cells isolated from the patient’s blood. The activation of T cells is assessed using an ELISPOT to detect IFNγ secretion and flow cytometry to measure activation marker expression on CD8+ T cells. Activated T cells are sorted using FACS to isolate specific T cell populations, and the TCRs of these cells are sequenced to identify the specific TCR genes. The identified TCR genes are inserted into T cells, enhancing their ability to target the tumor. The modified T cells are cultured and their functionality is verified in vitro by assessing cytokine production, activation level and killing capacity. Finally, the modified T cells are infused back into the patient as part of the adoptive T cell therapy, providing a personalized approach to cancer immunotherapy. APCs, antigen-presenting cells; ELISPOT, enzyme-linked immunospot; FACS, fluorescence-activated cell sorting; TCR, T cell receptor. Figure adapted from images created with BioRender.com.

5.2. Clinical exploration and trial based on neoantigens and TCR-T therapy

Many studies have tested TCR-T therapy in different cancer types, including melanoma, synovial sarcoma, rectal cancer and esophageal cancer. Some of the studies were aimed at TAA and obtained published efficacy, whereas some recently focused on neoantigens.

For abnormal expression in tumor tissues, some clinical trials focused on TAA or TSA, such as MART-1, NY-ESO-1, and MART-3, have yielded promising research results and efficacy published articles, whereas many TCR-T therapy clinical trials with different targets and patient types are currently being conducted. Johnson and his research team employed MART-1 high-affinity TCR-T cells as a therapeutic intervention for a cohort of 20 patients diagnosed with metastatic melanoma and observed a treatment response a rate of 30%.72 Rosenberg used mutated MAGE-A3 specific T cells for the treatment of patients diagnosed with cholangiocarcinoma and colorectal cancer and obtained promising results.73 In 2017, a research team conducted clinical trials targeting HLA-DPB1-restricted MAGE-A3 antigen-specific TCR-Ts and found that one patient with esophageal cancer achieved partial remission for up to four months.43 Nevertheless, some clinical trials targeting MAGE-A3 resulted in the manifestation of severe toxic effects. In a clinical trial, T cells engineered with a MAGE-A3-specific TCR exhibited cross-reactivity with MAGE-A12 present in the brain, triggering critical neurotoxicity, though they simultaneously induced a 56% objective response in nine metastatic melanoma patients. 43

In addition, several clinical trials have been conducted on different member proteins of the MAGE-A family, including MAGE-A4. In a clinical trial focused on esophageal cancer, Kageyama et al. constructed TCR-Ts targeting the MAGE-A4 antigen for therapeutic purposes in 10 patients with esophageal cancer, resulting in three patients surviving beyond 27 months without adverse effects. Seven patients exhibited disease progression during the initial two-month period following the treatment.45 Enhancing the affinity of TCR-Ts for different MAGE-A4 epitopes has recently achieved encouraging results in sarcoma treatment. During the phase 2 trial SPEARHEAD-1, the overall response rate was 39.4%, and the disease control rate reached 84.8%; two instances of complete response were noted in the trial of 37 individuals cohort.46

TCR-T testing for neoantigens is a growing and highly anticipated direction focused on the discovery of high-frequency gene mutation types and neoantigens, such as mutations in TP53, KRAS, and PIK3CA.

In a recent study, screening of neoantigens derived from TP53 mutations and the corresponding TCR in epithelial cancers identified 13 neoantigens capable of inducing T cell response and isolated nine new TCRs targeting seven different p53 neoantigens.65 Another study focused on metastatic solid cancers, which identified 21 unique T cell reactivities and constructed a library of 39 TCRs that specifically target TP53 mutations. These mutations are commonly present, being shared by 7.3% of patients diagnosed with various solid tumor types. A chemorefractory breast cancer patient was treated with TCR-T therapy targeting a p53R175H neoantigen and experienced objective tumor regression (–55%) that lasted six months. However, the disease progressed after six months due to the loss of Class I MHC expression.41

Many studies on KRAS mutations, such as KRAS G12D and G12V, are present in 60%–70% of pancreatic adenocarcinomas and 20%–30% of colorectal cancers. An experimental drug application was conducted to assess the safety profile and the degree of tolerability of KRAS G12D mutation specific TCR-Ts in individuals with pancreatic cancer.74 After six months, continuous tumor regression was observed, accompanied by an absence of reported toxic effects, and functionally active TCR-Ts remained detectable in the circulatory system. A clinical trial aimed at testing the safety and activity of mutant KRAS G12V-TCR-T was conducted in an advanced pancreatic cancer cohort expressing HLA-A*11:01 and the KRAS-G12V or G12D mutant (NCT04146298). In addition, two types of TCR-Ts show antitumor activity in preclinical models of female mice.74 Additionally, clinical trials are underway to test TCR-Ts against the KRASG12V mutation (NCT03190941).

PIK3CA is a key proto-oncogene, and the mutation of the PIK3CA causes continuous activation of the PI3K enzyme, enhances intracellular signaling, and leads to the disturbance of cell proliferation and survival signals, thus leading to the occurrence of cancer. For mutated PIK3CA shared in patients with different malignant tumors with HLA-A*03:01, a screening method was used to identify TCRs that recognize common neoantigens. In mice carrying mutant PIK3CA tumors, engineered TCR-Ts specifically targeting PIK3CA demonstrated an in vivo antitumor effect when challenged with tumors bearing the targeted mutation. However, they failed to exhibit such an effect against tumors expressing wild-type PIK3CA. These findings imply that the use of TCR-T therapy to target neoantigens in mutated cancer drivers has clinical implications.69

A new strategy using the CRISPR gene-editing technology to create personalized TCR-Ts also brings hope for personalized TCR-T therapy. TCRs against neoantigens was isolated, cloned, and validated in the blood of 16 participants. Autologous T cells were engineered by deleting endogenous TCR genes (TRA/TRB) and inserting sequences encoding the selected neoantigen-specific TCR. After receiving treatment, 11 patients had the best response in disease progression, whereas five patients experienced disease stabilization without any significant safety problems.75 This study explored a new direction for the development of more refined and tailored TCR-T therapies with enhanced safety.

6. Challenges of TCR-T therapy

6.1. Toxicity of TCR-T therapy

A major problem with immunotherapy is its toxicity, and TCR-T therapy is no exception. Some toxicity events related to on-target-off tumors have been reported, mostly targeting TAA, which are also expressed in normal tissues. In clinical trials utilizing TCR-T therapy against MART-1 and gp100, the observed ocular, dermal, and auditory toxicities were a result of TAA expression in melanocytes.31,40 On-target-off toxicity was analyzed based on transcriptomic, proteomic, and immunopeptidomic data to assess the T-cell recognition ability of normal cells.

Cross-reactivity is another common reason cause of toxicity, as a TCR can recognize antigens similar to those of the target antigen. Notably, the TCR-T that was engineered with the specific aim of targeting MAGE-A3 was also found to have the capacity to recognize an epitope derived from either MAGE-A12 or TITIN, resulting in fatal outcome in four patients.43 A useful method has each amino acid replaced with alanine to identify important amino acids in TCR-pMHC recognition. The peptide motifs composed of these important amino acids were compared with those of other proteins in the database to identify other proteins that may be recognized by the same TCR, so researchers can choose lowest cross-reactivity with the maximum security.

6.2. Identification of resistance mechanisms

TCR-based immunotherapy involves both primary and secondary resistance mechanisms. Primary resistance refers to low or heterogeneous expression of the target antigen in tumor cells, which results in a weak killing function. In addition, T cell expansion in vitro results in a late memory phenotype, leading to increased exhaustion and reduced persistence. Secondary resistance arose as a concern, which was attributed to the following reasons. First, the upregulation of immune checkpoint ligands on the surface of tumor cells has the capacity to disrupt the proliferation and functional integrity of adoptively transferred T cells. Through the activation of immune checkpoint receptors, ultimately resulting in T cell exhaustion. Second, MHC class I molecules on tumor cells are lost or decreased, which impedes the recognition of target epitopes by TCR-Ts. Tumor cells lacking HLA expression are selectively favored during TCR-T therapy. Notably, recent clinical trials employing TILs targeting KRAS67 mutational neoepitopes have reported the occurrence of HLA heterozygosity loss. The secondary resistance mechanism plays an important role in tumor immunology environment, for antitumor immune cells is severely inhibited because of the up-regulation of inhibitor receptors (e.g., PD-1, CTLA-4, TIM-3) and immunosuppressive cytokines (e.g., TGF-β, IL-10, VEGF).

6.3. Persistence and penetration of T cells

Many clinical events have shown that patients who do not respond to treatment fail to maintain the presence of infused tumor-specific T cells, whereas engineered T cells from patients who had a complete response or no relapse and effective tumor control showed robust proliferation and sustained long-term survival. This suggests that T cell persistence plays an important role in therapy; therefore, many studies have focused on different cytokines that have been used in therapy to ensure its durability. For example, IL-2 has been shown to boost T cell numbers and retain their functional capabilities, and some patients with advanced melanoma and kidney cancer showed lasting remissions, earning FDA approval and being integrated into CAR-T and TCR-T therapies.76 IL-12 plays a key role in potentiating effective antitumor immunity by activating cytotoxic T cell functions through the induction of cytotoxic agents such as perforin and various cytokines.77 IL-15 is recognized for its role in stimulating the production of stem cell memory T-cell, which are key for enduring T cell reactions, and together with IL-7, it prompts the formation of human memory stem T cells from immature ancestors. IL-21 belongs to the common γ-chain cytokine family. It exerts an inhibitory effect on the expansion of regulatory T cells (Tregs) by suppressing the expression of Foxp3, a process that facilitates the enrichment of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells. 78 Moreover, IL-21 enhances the maturation process and cytotoxic capacity of CD8+ T cells, and also contributes to the development of memory CD8+ T cells. Extensive research has demonstrated that IL-21 is more effective than IL-2 or IL-15 in promoting the in vitro generation of antigen-specific CD8+ CTLs. Additionally, it outperforms both IL-2 and IL-15 in vivo experiments and mouse models. These findings imply that cytokines can be utilized either individually or in combination with other cytokines to generate tumor-specific T cells with a memory phenotype. This approach can thereby enhance the durability, proliferative ability, and antitumor efficacy of adoptive cancer immunotherapy.

Although T cells can maintain long-term activity, their infiltration is also a research issue. A study found that fewer infused T cells infiltrated tumor tissue. The tumor microenvironment reduces the expression of chemokines (such as CXCL9/CXCL10) and adhesion molecules (such as ICAM-1 and VCAM-1).79 This decrease impairs the recruitment of T cells to the tumor site and prevents them from sticking and adhering effectively.80 Even when T cells reach the tumor, the abnormal and disordered structure of the tumor environment prevent the deep penetration of T cells. 81

7. Other viable immunotherapies targeting neoantigens

In addition to TCR-T therapy, other immunotherapies, such as ACT, tumor vaccines, antibody-based therapies, ICI, can also make use of the identified neoantigens.

7.1. Neoantigen vaccines

Neoantigen vaccines represent a potent strategy for eliciting T cell-mediated immune responses characterized by their notable advantages such as high feasibility, robust safety profiles, and streamlined production workflows.82 Common vaccines, including peptide and nucleic acid vaccines arising from neoantigens derived from somatic mutation83 are highly feasible and have been explored extensively. Vaccine can be designed based on one mutation and used for patients who have same mutation, greatly reducing the cost and time of design. What’s more, vaccine can express multiple antigens on their sequence alleviating immune escape.84 mRNA-4157 is an mRNA-based individualised neoantigen therapy encoding 34 neoantigens and is tailored specifically to an individual's leukocyte antigen type. Preclinical experiment showed that it could induce robust T cell response and safty profile.85 In a resected melanoma phase 2b study, mRNA-4157 combined with pembrolizumab as adjuvant therapy extended relapse-free survival in high-risk melanoma patients and demonstrated a manageable safety profile.86 A phase I trial testing neoantigen-targeted personalized cancer vaccines in clear cell renal cell carcinoma patients, none of the 9 participants had a recurrence of RCC at follow-up after surgery without observed dose-limiting toxicities.87

However, the safety of vaccines deserves attention for in many researches safety incidents happened calling for further optimization in vaccines. Adverse reactions to mRNA vaccines tend to increase and escalate with increasing dose. For example, in a Phase I trial of the modern influenza H10N8 vaccine, adverse events were observed from 400 μg. Therefore, they continued to use low doses up to 100 μg. In the Phase I trial of CV7202, 5 μg dose showed high regenicity so 1 μg is suitable dose given to the subject.88 All elements of tumor vaccines, including neoantigen targets, presentation methods, and delivery systems, are undergoing continuous refinement and enhancement. On that point, vaccines are a more viable option for widespread use but need to be improved and optimized to solve the security risks.

7.2. Therapeutic strategies targeting DC

While regular vaccines continue to be developed, a new type of vaccine using DCs pulsed with peptides or nucleic acid-targeting neoantigens89 also appears to be a promising method for efficiently ingesting, processing, and presenting TAAs to activate specific T cell responses. Furthermore, DC migrate to lymphoid and nonlymphoid tissues, regulate cytokine and chemokine gradients, and control inflammatory responses and lymphocyte homing, which are essential for systemic and long-lasting antitumor effects.90 There is also a new method of autologous DC co-culture with whole-tumor lysate to elicit a T cell immune response, because it does not take time to identify personalized antigens, while it also faces the challenge of limited abundance of nonimmunogenic autoantigens in tumor tissue.

There are some other strategies emerging to promote the DC functions and activate T cell better. Antibodies specifically target molecules on the surface of DC cells (such as CD40, DEC-205, Clec9A, etc.)91 to enhance the antigen presenting function and immune activation ability of DC cells. In addition, some small molecular drugs have been found to improve the function of DC. Tumor DNA uptake by DCs triggers the activation of the cytoplasmic DNA–sensing cGAS/STING pathway, then DC present tumor antigens and secrete cytokine to initiate antitumor T cell immunity. ADU-S100, a STING agonist, can greatly potentiate STING activation in antigen-presenting cells, induce DC to secrete IFN-α and TNF-α, and other maturation and migration.92 Other agonists like TLR were also found can promote DC maturation and cytokine secretion, so it’s widely used as vaccine adjuvants in many researches.93

7.3. Adoptive therapy of TIL

Adoptive therapy of TILs usually involves extracting TIL from patients, with or without genetic modification, amply under appropriate circumstances to increase response activity, and can be injected into patients. Specific TIL for neoantigens or selected TIL have great response activity and can achieve lasting tumor regression. Famous adoptive therapies include CAR-T and TCR-T, while the advantages of TCR-T are described above: CAR-T therapies also show several advantages over TCR-Ts in cancer treatment; in particular, they operate independently of the HLA expression and neoantigen presentation pathways that cancer cells exploit to escape immune detection and attack. Through their engineered CAR molecules, are able to recognize and bind to a variety of cell surface proteins and activate them independently of the MHC.94 In addition, CAR-Ts can integrate Boolean logic gates with other receptors, such as SNIPR,95 to improve tumor-specific recognition, killing efficiency, and precise targets. However, strategies to identify tumor-specific neoantigens offer new therapeutic hope for patients with solid tumors, and ongoing clinical trials are testing CAR-Ts targeting new neoantigens, which have been shown to be effective in controlling tumor growth in animal models. In addition, T cells preactivated by specific neoantigens can develop vehicles that broadly express antigens against the tumor, enabling full-scale attack on the tumor.

7.4. Immune checkpoint inhibitors

ICIs work by targeting proteins that cancer cells use to protect themselves from being attacked by the immune system, effectively releasing the “brakes” on immune cells and allowing them to recognize and attack cancer cells more effectively, has demonstrated sustained antitumor efficacy across various malignancies, such as renal cell carcinoma, NSCLC, and melanoma. However, the absence of specific T cells renders patients unresponsive to ICI and ICI target only part of the T cell response. Many clinical trials have adopted the strategy of neoantigen-based therapy combined with ICIs, as ICI can reinvigorate exhausted T cells and increase their therapeutic effect.96

8. Conclusions and envision

Neoantigens are ideal targets for many immunotherapies, including ACTs, tumor vaccines, and ICIs, owing to their specific expression in tumor cells. Therapies targeting it do not destroy normal tissues and have been verified in many clinical cases. However, to advance the development and application of neoantigen-based therapies, many technical and experimental difficulties must be overcome, including sequencing technology, antigen prediction algorithms, and the cost of personalized therapy.

In personalized cancer immunotherapy, precise identification of immunogenic neoantigens along with their matching TCR is a critical step. These neoantigens can be detected through immunogenomic techniques that construct virtual peptides based on next-generation sequencing data as well as through immunoprecipitation methods that analyze MHC-presented peptides using MS. Integrating genomic and transcriptomic data with MS maps of HLA peptides enhance the precision of neoantigen identification. With the progress made in high-capacity sequencing technologies and the application of sophisticated deep learning approaches, the cost of neoantigen therapies is decreasing; however, clinical applications still rely on efficient computational workflows and classification standards. These computational tools can also leverage big data to predict the potential of neoantigens as prognostic markers or predictors of the response to immune checkpoint blockade. To advance neoantigen therapies, it is essential to validate the accuracy of these predictive methods using immune surveillance during the initial phases of clinical studies. In addition to these computational prediction methods grounded in high-throughput data, a number of impartial strategies for uncovering T cell antigens have surfaced to pinpoint immunogenic neoantigens. The straightforwardness and adaptability of these methods for discovering T-cell ligands will facilitate the exploration of candidate neoantigens’ immunogenicity and play a role in advancing novel immunotherapies centered around neoantigens.

The high price of personalized therapy is one reason why it has not been widely used. In addition to the decrease in the cost of sequencing and each step, an ideal strategy is to target common personalized neoantigens. Common neoantigens are usually shared with patients in genes driven by hot mutations that are present with common HLA molecules. Many studies have focused on discovering common neoantigens and matching TCR sequences; therefore, a larger cohort of patients with common genetic mutations stands to gain from public and common neoantigen response TCR libraries. Moreover, the broad adoption of cancer genome sequencing alongside neoantigen prediction techniques will facilitate the alignment of patients with treatments that specifically target common neoantigens present in their tumors.69 Targeting a common neoantigen strategy is anticipated to expedite the process of neoantigen identification and T-cell cultivation, decrease the cost of constructing personalized TCR-Ts, and increase the use of neoantigen-based therapies.

The feasibility of TCR-Ts in tumors has been validated theoretically, experimentally, and in many clinical cases. Despite the problems that TCR-T therapy still encounters certain issues, we should recognize the feasibility and hope of this powerful therapy in clinical application prospects, and focus on how to overcome the challenge and advance this technology. Given the progress achieved in tumor immunology and genetic engineering, the cost of TCR-T will be reduced, and personalized TCR-T therapy will become possible. Currently, TCR-T therapy only considers the expression of antigens and MHC molecules. When the two conditions are met, the same therapy used for multiple patients, regardless of the different actual situations in the patients, varies greatly.

Research has indicated that in recent years, the creation of TCR-T cancer immunotherapies aimed at specific tumors through the utilization of intracellular antigens has emerged as a focal point of investigation. An ideal individual TCR-T strategy is designed based on the expression of TAAs or neoantigens, which can significantly improve the curative effect and safety profile of therapy. Moreover, TCR-Ts can be used in combination with ICIs to enhance their effectiveness. Thus, further exploration of different combinations of therapies should be conducted to obtain better results. In conclusion, neoantigens serve as an ideal target and will be used in many immunotherapies. TCR-T therapy is assumed a more significant position in the realm of tumor treatment, signifying a highly promising avenue and this development is anticipated to bring hope to patients with tumors.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to writing the manuscript and designed and prepared the figures and legends.

Footnotes

Given her role as Associate Editor, Zhihua Liu had no involvement in the peer-review of this article and has no access to information regarding its peer-review. Full responsibility for the editorial process for this article was delegated to Huan He.

Contributor Information

Yahui Zhao, Email: zhaoyh@cicams.ac.cn.

Zhihua Liu, Email: liuzh@cicams.ac.cn.

References

- 1.Vaddepally R.K., Kharel P., Pandey R., Garje R., Chandra A.B. Review of indications of FDA-approved immune checkpoint inhibitors per NCCN guidelines with the level of evidence. Cancers (Basel) 2020;12(3):738. doi: 10.3390/cancers12030738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Twomey J.D., Zhang B. Cancer immunotherapy update: FDA-approved checkpoint inhibitors and companion diagnostics. Aaps J. 2021;23:39. doi: 10.1208/s12248-021-00574-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roddie C., Rampotas A. The present and future for CAR-T cell therapy in adult B-cell ALL. Blood. 2025;145:1485–1497. doi: 10.1182/blood.2023022922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sheykhhasan M., Ahmadieh-Yazdi A., Vicidomini R., et al. CAR T therapies in multiple myeloma: unleashing the future. Cancer Gene Ther. 2024;31:667–686. doi: 10.1038/s41417-024-00750-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cappell K.M., Kochenderfer J.N. Long-term outcomes following CAR T cell therapy: what we know so far. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2023;20:359–371. doi: 10.1038/s41571-023-00754-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chandran S.S., Klebanoff C.A. T cell receptor-based cancer immunotherapy: emerging efficacy and pathways of resistance. Immunol Rev. 2019;290:127–147. doi: 10.1111/imr.12772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pang Z., Lu M.M., Zhang Y., et al. Neoantigen-targeted TCR-engineered T cell immunotherapy: current advances and challenges. Biomark Res. 2023;11:104. doi: 10.1186/s40364-023-00534-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Peri A., Salomon N., Wolf Y., Kreiter S., Diken M., Samuels Y. The landscape of T cell antigens for cancer immunotherapy. Nature cancer. 2023;4:937–954. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2119662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leidner R., Sanjuan S.N., Huang H., et al. Neoantigen T-cell receptor gene therapy in pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med. 2022;386:2112–2119. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2119662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li J., Xiao Z., Wang D., et al. The screening, identification, design and clinical application of tumor-specific neoantigens for TCR-T cells. Mol Cancer. 2023;22:141. doi: 10.1186/s12943-023-01844-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xie N., Shen G., Gao W., Huang Z., Huang C., Fu L. Neoantigens: promising targets for cancer therapy. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2023;8:9. doi: 10.1038/s41392-022-01270-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kotsias F., Cebrian I., Alloatti A. Antigen processing and presentation. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol. 2019;348:69–121. doi: 10.1016/bs.ircmb.2019.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cattaneo C.M., Battaglia T., Urbanus J., et al. Identification of patient-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cell neoantigens through HLA-unbiased genetic screens. Nat Biotechnol. 2023;41:783–787. doi: 10.1038/s41587-022-01547-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sixt M., Kanazawa N., Selg M., et al. The conduit system transports soluble antigens from the afferent lymph to resident dendritic cells in the T cell area of the lymph node. Immunity. 2005;22:19–29. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Albert M.L., Sauter B., Bhardwaj N. Dendritic cells acquire antigen from apoptotic cells and induce class I-restricted CTLs. Nature. 1998;392:86–89. doi: 10.1038/32183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vigneron N. Human tumor antigens and cancer immunotherapy. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015 doi: 10.1155/2015/948501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ilyas S., Yang J.C. Landscape of tumor antigens in T cell immunotherapy. J Immunol. 2015;195:5117–5122. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1501657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meng X., Sun X., Liu Z., He Y. A novel era of cancer/testis antigen in cancer immunotherapy. Int Immunopharmacol. 2021;98 doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2021.107889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Das B., Senapati S. Immunological and functional aspects of MAGEA3 cancer/testis antigen. Adv Protein Chem Struct Biol. 2021;125:121–147. doi: 10.1016/bs.apcsb.2020.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhuo S., Yang S., Chen S., et al. Unveiling the significance of cancer-testis antigens and their implications for immunotherapy in glioma. Discov Oncol. 2024;15:602. doi: 10.1007/s12672-024-01449-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abd H.M., Peng Y., Dong T. Human cancer germline antigen-specific cytotoxic T cell—what can we learn from patient. Cellular & Molecular Immunology. 2020;17:684–692. doi: 10.1038/s41423-020-0468-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Scanlan M.J., Gure A.O., Jungbluth A.A., Old L.J., Chen Y.T. Cancer/testis antigens: an expanding family of targets for cancer immunotherapy. Immunol Rev. 2002;188:22–32. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065x.2002.18803.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhu W., Peng Y., Wang L., et al. Identification of α-fetoprotein-specific T-cell receptors for hepatocellular carcinoma immunotherapy. Hepatology. 2018;68:574–589. doi: 10.1002/hep.29844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Docta R.Y., Ferronha T., Sanderson J.P., et al. Tuning T-cell receptor affinity to optimize clinical risk-benefit when targeting alpha-fetoprotein–positive liver cancer. Hepatology. 2019;69:2061–2075. doi: 10.1002/hep.30477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dargel C., Bassani-Sternberg M., Hasreiter J., et al. T cells engineered to express a T-cell receptor specific for glypican-3 to recognize and kill hepatoma cells in vitro and in mice. Gastroenterology. 2015;149:1042–1052. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.05.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang J., Feng B. Abstract B035: enhanced tumor infiltration and functionality of anti-GPC3 CAR-T cells in hepatocellular carcinoma through locoregional administration. Cancer Immunol Res. 2024;12:B035. doi: 10.1158/2326-6074.Tumimm24-b035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Buhring H.J., Sures I., Jallal B., et al. The receptor tyrosine kinase p185HER2 is expressed on a subset of B-lymphoid blasts from patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia and chronic myelogenous leukemia. Blood. 1995;86:1916–1923. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Slamon D.J., Clark G.M., Wong S.G., Levin W.J., Ullrich A., McGuire W.L. Human breast cancer: correlation of relapse and survival with amplification of the HER-2/neu oncogene. Science. 1987;235:177–182. doi: 10.1126/science.3798106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alrhmoun S., Fisher M., Lopatnikova J., et al. Targeting precision in cancer immunotherapy: naturally-occurring antigen-specific TCR discovery with single-cell sequencing. Cancers. 2024;16:4020. doi: 10.3390/cancers16234020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Meyerhuber P., Conrad H., Stärck L., et al. Targeting the epidermal growth factor receptor (HER) family by T cell receptor gene-modified T lymphocytes. J Mol Med (Berl) 2010;88:1113–1121. doi: 10.1007/s00109-010-0660-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Johnson L.A., Morgan R.A., Dudley M.E., et al. Gene therapy with human and mouse T-cell receptors mediates cancer regression and targets normal tissues expressing cognate antigen. Blood. 2009;114:535–546. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-03-211714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Golikova E.A., Alshevskaya A.A., Alrhmoun S., Sivitskaya N.A., Sennikov S.V. TCR-T cell therapy: current development approaches, preclinical evaluation, and perspectives on regulatory challenges. J Transl Med. 2024;22:897. doi: 10.1186/s12967-024-05703-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Malcovati L., Stevenson K., Papaemmanuil E., et al. SF3B1-mutant MDS as a distinct disease subtype: a proposal from the International Working Group for the Prognosis of MDS. Blood. 2020;136:157–170. doi: 10.1182/blood.2020004850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bigot J., Lalanne A.I., Lucibello F., et al. Splicing patterns in SF3B1-mutated Uveal melanoma generate shared immunogenic tumor-specific neoepitopes. Cancer Discov. 2021;11:1938–1951. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-20-0555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Polaski J.T., Udy D.B., Escobar-Hoyos L.F., et al. The origins and consequences of UPF1 variants in pancreatic adenosquamous carcinoma. Elife. 2021;10 doi: 10.7554/eLife.62209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kahles A., Lehmann K.V., Toussaint N.C., et al. Comprehensive analysis of alternative splicing across tumors from 8,705 patients. Cancer Cell. 2018;34:211–224.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2018.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Doran S.L., Stevanovic S., Adhikary S., et al. T-cell receptor gene therapy for Human papillomavirus-associated epithelial cancers: a first-in-Human, phase I/II study. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37:2759–2768. doi: 10.1200/JCO.18.02424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Meng F., Zhao J., Tan A.T., et al. Immunotherapy of HBV-related advanced hepatocellular carcinoma with short-term HBV-specific TCR expressed T cells: results of dose escalation, phase I trial. Hepatol Int. 2021;15:1402–1412. doi: 10.1007/s12072-021-10250-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ursu R.G., Damian C., Porumb-Andrese E., et al. Merkel cell polyoma virus and cutaneous Human papillomavirus types in skin cancers: optimal detection assays, pathogenic mechanisms, and therapeutic vaccination. Pathogens. 2022;11:479. doi: 10.3390/pathogens11040479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chodon T., Comin-Anduix B., Chmielowski B., et al. Adoptive transfer of MART-1 T-cell receptor transgenic lymphocytes and dendritic cell vaccination in patients with metastatic melanoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20:2457–2465. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-3017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kim S.P., Vale N.R., Zacharakis N., et al. Adoptive cellular therapy with autologous tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and T-cell receptor-engineered T cells targeting common p53 neoantigens in Human solid tumors. Cancer Immunol Res. 2022;10:932–946. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-22-0040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nowicki T.S., Berent-Maoz B., Cheung-Lau G., et al. A pilot trial of the combination of transgenic NY-ESO-1-reactive adoptive cellular therapy with dendritic cell vaccination with or without Ipilimumab. Clin Cancer Res. 2019;25:2096–2108. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-3496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Morgan R.A., Chinnasamy N., Abate-Daga D., et al. Cancer regression and neurological toxicity following anti-MAGE-A3 TCR gene therapy. J Immunother. 2013;36:133–151. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e3182829903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Linette G.P., Stadtmauer E.A., Maus M.V., et al. Cardiovascular toxicity and titin cross-reactivity of affinity-enhanced T cells in myeloma and melanoma. Blood. 2013;122:863–871. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-03-490565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kageyama S., Ikeda H., Miyahara Y., et al. Adoptive transfer of MAGE-A4 T-cell receptor gene-transduced lymphocytes in patients with recurrent esophageal cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21:2268–2277. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-1559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hong D.S., Van Tine B.A., Olszanski A.J., et al. Phase I dose escalation and expansion trial to assess the safety and efficacy of ADP-A2M4 SPEAR T cells in advanced solid tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38:102. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2020.38.15_suppl.102. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Veatch J., Paulson K., Asano Y., et al. Merkel polyoma virus specific T-cell receptor transgenic T-cell therapy in PD-1 inhibitor refractory Merkel cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2022;40:9549. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2022.40.16_suppl.9549. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Setliff I., Shiakolas A.R., Pilewski K.A., et al. High-throughput mapping of B cell receptor sequences to antigen specificity. Cell. 2019;179:1636–1646.e15. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Xiao W., Ren L., Chen Z., et al. Toward best practice in cancer mutation detection with whole-genome and whole-exome sequencing. Nat Biotechnol. 2021;39:1141–1150. doi: 10.1038/s41587-021-00994-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Neefjes J., Jongsma M.L., Paul P., Bakke O. Towards a systems understanding of MHC class I and MHC class II antigen presentation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11:823–836. doi: 10.1038/nri3084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Profaizer T., Kumánovics A. Human leukocyte antigen typing by next-generation sequencing. Clin Lab Med. 2018;38:565–578. doi: 10.1016/j.cll.2018.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rosenthal R., Cadieux E.L., Salgado R., et al. Neoantigen-directed immune escape in lung cancer evolution. Nature. 2019;567:479–485. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1032-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sahin U., Derhovanessian E., Miller M., et al. Personalized RNA mutanome vaccines mobilize poly-specific therapeutic immunity against cancer. Nature. 2017;547:222–226. doi: 10.1038/nature23003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jurtz V., Paul S., Andreatta M., Marcatili P., Peters B., Nielsen M. NetMHCpan-4.0: improved peptide-MHC class I interaction predictions integrating eluted ligand and peptide binding affinity data. J Immunol. 2017;199:3360–3368. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1700893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]