Abstract

Background

This is an update of a Cochrane Review originally published in Issue 1, 2007 of The Cochrane Library.

Tinnitus is an auditory perception that can be described as the experience of sound, in the ear or in the head, in the absence of external acoustic stimulation. Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) uses relaxation, cognitive restructuring of the thoughts and exposure to exacerbating situations in order to promote habituation and may benefit tinnitus patients, as may the treatment of associated psychological conditions.

Objectives

To assess whether CBT is effective in the management of patients suffering from tinnitus.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Ear, Nose and Throat Disorders Group Trials Register; the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL); PubMed; EMBASE; CINAHL; Web of Science; BIOSIS Previews; Cambridge Scientific Abstracts; PsycINFO; ISRCTN and additional sources for published and unpublished trials. The date of the most recent search was 6 May 2010.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials in which patients with unilateral or bilateral tinnitus as their main symptom received cognitive behavioural treatment.

Data collection and analysis

One review author (PMD) assessed every report identified by the search strategy. Three authors (PMD, AW and MT) assessed the methodological quality and applied inclusion/exclusion criteria. Two authors (PMD and RP) extracted data and conducted the meta‐analysis. The four authors contributed to the final text of the review.

Main results

Eight trials comprising 468 participants were included.

For the primary outcome of subjective tinnitus loudness we found no evidence of a difference between CBT and no treatment or another intervention (yoga, education and 'minimal contact ‐ education').

In the secondary outcomes we found evidence that quality of life scores were improved in participants who had tinnitus when comparing CBT to no treatment or another intervention (education and 'minimal contact education'). We also found evidence that depression scores improved when comparing CBT to no treatment. We found no evidence of benefit in depression scores when comparing CBT to other treatments (yoga, education and 'minimal contact ‐ education').

There were no adverse/side effects reported in any trial.

Authors' conclusions

In six studies we found no evidence of a significant difference in the subjective loudness of tinnitus.

However, we found a significant improvement in depression score (in six studies) and quality of life (decrease of global tinnitus severity) in another five studies, suggesting that CBT has a positive effect on the management of tinnitus.

Keywords: Humans, Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, Cognitive Behavioral Therapy/methods, Quality of Life, Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic, Tinnitus, Tinnitus/therapy

Plain language summary

Cognitive behavioural therapy for tinnitus

Tinnitus can be described as the experience of sound in the ear or in the head. Subjective tinnitus is not heard by anyone else. At present no particular treatment for tinnitus has been found effective in all patients.

Cognitive behavioural therapy was originally developed as a treatment for depression and then also used for anxiety, insomnia and chronic pain. It is a form of psychological treatment that uses relaxation, remodelling thoughts and challenging situations to improve the patient's attitude towards tinnitus.

The objective of this review was to assess whether cognitive behavioural therapy is effective in the management of patients suffering from tinnitus.

Eight trials (468 participants) are included in this review. Data analysis did not demonstrate any significant effect in the subjective loudness of tinnitus. We found, however, a significant improvement in the depression associated with tinnitus and quality of life (decrease of global tinnitus severity), suggesting that cognitive behavioural therapy has a positive effect on the way in which people cope with tinnitus.

Further research should use a limited number of validated questionnaires in a more consistent way and with a longer follow up to assess the long‐term effect of cognitive behavioural therapy in patients with tinnitus.

Background

This is an update of a Cochrane Review originally published in Issue 1, 2007 of The Cochrane Library.

This is one of a number of tinnitus reviews produced by the Cochrane Ear, Nose & Throat Disorders Group, which use a standard Background. The following paragraphs ('Description of the condition') are based on earlier work in the following reviews and reproduced with permission: Baldo 2006; Bennett 2007; Hilton 2004; Hobson 2007; Phillips 2010.

Description of the condition

Tinnitus can be described as the perception of sound in the absence of external acoustic stimulation. For the patient it may be trivial or it may be a debilitating condition (Luxon 1993). The quality of the perceived sound can vary enormously from simple sounds such as whistling or humming to complex sounds such as music. The patient may hear a single sound or multiple sounds. Tinnitus may be perceived in one or both ears, within the head or outside the body. The symptom may be continuous or intermittent. Tinnitus is described in most cases as subjective ‐ meaning that it cannot be heard by anyone other than the patient. While, for the patient, this perception of noise is very real, because there is no corresponding external sound it can be considered a phantom, or false, perception. Objective tinnitus is a form of tinnitus which can be detected by an examiner, either unaided or using a listening aid such as a stethoscope or microphone in the ear canal. This is much less common and usually has a definable cause, such as sound generated by blood flow in or around the ear or unusual activity of the tiny muscles within the middle ear. Tinnitus may be associated with normal hearing or any degree of hearing loss and can occur at any age.

It is important to distinguish between clinically significant and non‐significant tinnitus (Davis 2000) and several different classifications have been proposed (Dauman 1992; McCombe 2001; Stephens 1991). Dauman, for example, makes a distinction between 'normal' (lasting less than five minutes, occurring less than once a week and experienced by most people) and 'pathological' tinnitus (lasting more than five minutes, occurring more than once a week and usually experienced by people with hearing loss).

Aetiology

Almost any form of disorder involving the outer, middle or inner ear or the auditory nerve may be associated with tinnitus (Brummett 1980; Shea 1981). However, it is possible to have severe tinnitus with no evidence of any aural pathology. Conversely, tinnitus can even exist without a peripheral auditory system: unilateral tinnitus is a common presenting symptom of vestibular schwannomas (acoustic neuromas), which are rare benign tumours of the vestibulo‐cochlear nerve. When these neuromas are removed by a translabyrinthine route, the cochlear nerve can be severed. Despite the effective removal of their peripheral auditory mechanisms, 60% of these patients retain their tinnitus postoperatively (Baguley 1992). This suggests the fundamental importance of the central auditory pathways in the maintenance of the symptom, irrespective of trigger.

Many environmental factors can also cause tinnitus. The most relevant and frequently reported are:

acute acoustic trauma (AAT) (for example, explosions or gunfire) (Christiansson 1993; Chung 1980; Melinek 1976; Mrena 2002; Temmel 1999);

airbag inflation (Saunders 1998); toy pistols (Fleischer 1999);

exposure to occupational noise; 'urban noise pollution' (Alberti 1987; Axelsson 1985; Chouard 2001; Daniell 1998; Griest 1998; Kowalska 2001; McShane 1988; Neuberger 1992; Phoon 1993); and

exposure to recreational and amplified music (Becher 1996; Chouard 2001; Lee 1999; Metternich 1999)

Pathophysiology

Over 50 years ago, Heller and Bergman demonstrated that if 'normal' people (with no known cochlear disease) were placed in a quiet enough environment, the vast majority of them would experience sounds inside their head. They concluded that tinnitus‐like activity is a natural phenomenon perceived by many in a quiet enough environment (Heller 1953).

Mazurek has shown that pathologic changes in the cochlear neurotransmission, e.g. as a result of intensive noise exposure or ototoxic drugs, can be a factor in the development of tinnitus (Mazurek 2007).

In the 'neurophysiological model' of tinnitus (Jastreboff 1990; Jastreboff 2004) it is proposed that tinnitus results from the abnormal processing of a signal generated in the auditory system. This abnormal processing occurs before the signal is perceived centrally. This may result in 'feedback', whereby the annoyance created by the tinnitus causes the individual to focus increasingly on the noise, which in turn exacerbates the annoyance and so a 'vicious cycle' develops. In this model tinnitus could therefore result from continuous firing of cochlear fibres to the brain, from hyperactivity of cochlear hair cells or from permanent damage to these cells being translated neuronally into a 'phantom' sound‐like signal that the brain 'believes' it is hearing. For this reason tinnitus may be compared to chronic pain of central origin ‐ a sort of 'auditory pain' (Briner 1995; Sullivan 1994).

The relationship between the symptom of tinnitus and the activity of the prefrontal cortex and limbic system has been emphasised. The limbic system mediates emotions. It can be of great importance in understanding why the sensation of tinnitus is in many cases so distressing for the patient. It also suggests why, when symptoms are severe, tinnitus can be associated with major depression, anxiety and other psychosomatic and/or psychological disturbances, leading to a progressive deterioration of quality of life (Lockwood 1999; Sullivan 1989; Sullivan 1992; Sullivan 1993).

Prevalence

Epidemiological data reports are few. The largest single study was undertaken in the UK by the Medical Research Council Institute of Hearing Research and was published in 2000 (Davis 2000). This longitudinal study of hearing questioned 48,313 people; 10.1% described tinnitus arising spontaneously and lasting for five or more minutes at a time and 5% described it as moderately or severely annoying. However, only 0.5% reported tinnitus having a severe effect on their life. This is another of the paradoxes of tinnitus: the symptom is very common but the majority of people who experience it are not particularly concerned by it. These figures from the UK are broadly consistent with data collected by the American Tinnitus Association (ATA) which suggests that tinnitus may be experienced by around 50 million Americans, or 17% of the US population (ATA 2004). Data also exist for Japan, Europe and Australia (Sindhusake 2003), and estimates suggest that tinnitus affects a similar percentage of these populations, with 1% to 2 % experiencing debilitating tinnitus (Seidman 1998). The Oregon Tinnitus Data Archive (Oregon 1995) contains data on the characteristics of tinnitus drawn from a sample of 1630 tinnitus patients. The age groups with the greater prevalence are those between 40 and 49 years (23.9%) and between 50 and 59 years (25.6%).

Olszewski showed in his study that the risk of tinnitus increases in patients over 55 years old who suffer from metabolic conditions and cervical spondylosis (Olszewski 2008).

Diagnosis

Firstly a patient with tinnitus may undergo a basic clinical assessment. This will include the relevant otological, general and family history, and an examination focusing on the ears, teeth and neck and scalp musculature. Referral to a specialist is likely to involve a variety of other investigations including audiological tests and radiology. Persistent, unilateral tinnitus may be due to a specific disorder of the auditory pathway and imaging of the cerebellopontine angle is important to exclude, for example, a vestibular schwannoma (acoustic neuroma) ‐ a rare benign tumour of the cochleo‐vestibular nerve. Other lesions, such as glomus tumours, meningiomas, adenomas, vascular lesions or neuro‐vascular conflicts may also be detected by imaging (Marx 1999; Weissman 2000).

Treatment

At present no specific therapy for tinnitus is acknowledged to be satisfactory in all patients. Many patients who complain of tinnitus, and also have a significant hearing impairment, will benefit from a hearing aid. Not only will this help their hearing disability but the severity of their tinnitus may be reduced.

A wide range of therapies have been proposed for the treatment of tinnitus symptoms. Pharmacological interventions used include cortisone (Koester 2004), vasodilators, benzodiazepines, lidocaine and spasmolytic drugs. The use of anticonvulsants in treating tinnitus is the subject of a forthcoming Cochrane Review (Hoekstra 2009). Antidepressants are commonly prescribed for tinnitus. However, two reviews (Baldo 2006; Robinson 2007) showed that there is no indication that tricyclic antidepressants have a beneficial effect.

Although a number of studies have suggested that Ginkgo biloba may be of benefit in the treatment of tinnitus (Ernst 1999; Holger 1994; Rejali 2004), a Cochrane Review showed that there was no evidence that it is effective where tinnitus was the primary complaint (Hilton 2004).

Hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBOT) can improve oxygen supply to the inner ear which it is suggested may result in an improvement in tinnitus, however a Cochrane Review found insufficient evidence to support this (Bennett 2007).

Other options for the management of patients with tinnitus include transcranial magnetic stimulation (Meng 2009), tinnitus masking (use of 'white noise' generators) (Hobson 2007), music therapy (Argstatter 2008), reflexology, hypnotherapy and traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) including acupuncture (Li 2009).

Description of the intervention

Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) is a structured, time‐limited psychological therapy. It is usually offered on an outpatient basis with between eight and 24 weekly sessions. It involves the patient using behavioural and cognitive tasks to modify their response to thoughts and situations.

Cognitive behavioural therapy is based on the principle that core beliefs, usually developed in childhood and often arising from a specific incident, provide a pattern of assumptions. Specific mood states or events similar to the original or critical incident can set up thought patterns which reinforce the core beliefs. These patterns influence behavioural and emotional responses giving rise to symptoms, which may be cognitive, behavioural or somatic.

Tinnitus may be conceived as a failure to adapt to a stimulus (Hallam 1984) and in that sense may be considered to be analogous to anxiety states.

Cognitive behavioural therapy involves collaborative empiricism (Beck 1979) in which patient and therapist view the patient's fearful thoughts as hypotheses to be critically examined and tested. This is achieved by (a) generating an understanding of the link between thoughts and feelings arising from an event and using this information to understand the core beliefs and (b) modifying these cognitions and the behavioural and cognitive responses by which they are normally maintained. Education, discussion of evidence for and against the beliefs, imagery modification, attentional manipulations, exposure to feared stimuli and relaxation techniques are used in the therapy. Behavioural and cognitive assignments which test beliefs are used. The potential pitfalls and obstacles are identified and achievable goals are set so that a successful and therefore therapeutic outcome is experienced.

Originally developed as a treatment for depression, there are now a wide range of psychological conditions for which cognitive behavioural therapy has an evidence‐based rationale including anxiety, insomnia and chronic pain (Hawton 1989). The use of relaxation, cognitive restructuring of the thoughts and exposure to exacerbating situations in order to promote habituation may benefit tinnitus patients, as may the treatment of associated psychological conditions.

Objectives

To assess whether cognitive behavioural therapy is effective in the management of tinnitus. As the symptoms of tinnitus are very subjective for the great majority of patients, we aimed to evaluate subjective improvement in the perception of this symptom.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials.

Types of participants

Patients with unilateral or bilateral tinnitus as main symptom, not necessarily associated with hearing loss, and with or without depression. We excluded patients with pulsatile tinnitus and other somatic sounds, delusional auditory hallucinations and patients undergoing concurrent psychotherapeutic interventions.

Types of interventions

Cognitive behavioural therapy (of variable intensity and duration, within a group or individually, by a qualified practitioner) versus no treatment or other treatments.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Subjective tinnitus loudness (measured on a numeric scale).

Secondary outcomes

Subjective and objective improvement of the symptoms of depression and mood disturbances associated (but not necessarily caused by) with tinnitus. Evaluation of quality of life for patients (Tinnitus Handicap Questionnaire or other validated assessment method). Adverse effects (i.e. worsening of symptoms, suicidal tendencies, negative thoughts).

Search methods for identification of studies

We conducted systematic searches for randomised controlled trials. There were no language, publication year or publication status restrictions. The date of the last search was 6 May 2010.

Electronic searches

We searched the following databases from their inception for published, unpublished and ongoing trials: the Cochrane Ear, Nose and Throat Disorders Group Trials Register; the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL, The Cochrane Library Issue 4, 2010); PubMed; EMBASE; CINAHL; LILACS; KoreaMed; IndMed; PakMediNet; CAB Abstracts; Web of Science; BIOSIS Previews; CNKI; ISRCTN; ClinicalTrials.gov; ICTRP and Google.

We modelled subject strategies for databases on the search strategy designed for CENTRAL. Where appropriate, we combined subject strategies with adaptations of the highly sensitive search strategy designed by the Cochrane Collaboration for identifying randomised controlled trials and controlled clinical trials (as described in The Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.0.2, Box 6.4.b. (Handbook 2009)). Search strategies for major databases including CENTRAL are provided in Appendix 1.

Searching other resources

We scanned reference lists of identified studies for further trials. We searched PubMed, TRIPdatabase, NHS Evidence ‐ ENT and Audiology, and Google to retrieve existing systematic reviews possibly relevant to this systematic review, in order to search their reference lists for additional trials. Abstracts from conference proceedings were sought via the Cochrane Ear, Nose and Throat Disorders Group Trials Register.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

One review author (PMD) assessed every report identified by the search strategy described above for relevance to this review. The criteria for selection at this stage were simple and broad, so as not to miss any relevant study, and were:

randomisation;

diagnosis of tinnitus;

comparison between cognitive behavioural therapy and other treatment or no treatment.

Four review authors, blinded to decisions made each other, decided which trials met the inclusion criteria and graded their methodological quality. Any disagreement was resolved by discussion between the review authors. We contacted authors if necessary for clarification.

Data extraction and management

The authors extracted data independently onto standardised data forms. Studies that had incomplete or ambiguous reporting of data were clarified by discussion between the authors.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

The criteria for quality assessment were based on the recommendations of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, version 4.2.1, Section 6 (updated December 2003). We assessed the quality of selected studies for the following characteristics:

Adequacy of the randomisation process and of allocation concealment: A ‐ adequate (e.g. centralised randomisation by a central office); B ‐ unclear (e.g. apparently adequate concealment but without other information in trial); C ‐ inadequate (e.g. alterations in method or any allocation that could be potentially transparent).

Attrition bias: A ‐ adequate (trials where an intention‐to‐treat analysis is possible and drop‐out rate was less than 20% in all groups); B ‐ unclear (trials where drop‐out rate was more than 20% or great heterogeneity in drop‐out rate between groups was observed); C ‐ inadequate (lack of reporting on drop‐out rate and intention‐to‐treat analysis is not possible).

Detection bias: Blinding of investigators who assessed the outcomes of interventions is relevant to this research, in that the outcome measures have great subjective components (severity of tinnitus and/or associated depression). For the purpose of this review, it was also important to evaluate the adequacy, the development and the standardisation of the questionnaires used in the trials. For this reason adequacy of studies was classified as:

A ‐ adequate (trials in which blinding of investigators assessing outcomes was adequate; the utilisation of questionnaires was clearly shown; the questionnaires used were well‐known and/or standardised); B ‐ unclear (trials in which blinding of investigators is not adequately described and/or the utilisation of questionnaires was not clearly shown; the questionnaires used were not well‐known and/or not standardised); C ‐ inadequate (trials in which blinding of investigators was clearly not performed).

We graded studies A, B or C for their overall methodological quality. We used study quality in a sensitivity analysis.

Data synthesis

Data analysis was by intention‐to‐treat. For dichotomous data we calculated the odds ratio (OR) and number needed to treat (NNT). For continuous data, we calculated the standardised mean difference (SMD).

A pooled statistical analysis of treatment effects proceeded only in the absence of significant clinical or statistical heterogeneity. When obtaining the outcome of change we used the correlation obtained from Zachriat 2004 (complete data set, correlation = 0.69) to model the outcomes for those studies that reported measures at baseline and endpoint only.

The main analysis was an examination of severity (subjective loudness) of tinnitus and its effect on depression and quality of life, during and after the period of treatment.

We also planned to collect and analyse data on any adverse reactions due to treatment.

Results

Description of studies

See tables of 'Characteristics of included studies' and 'Characteristics of excluded studies'.

Twenty‐seven studies were identified following our search, from which eight studies (comprising 468 participants) met our inclusion criteria.

Most of the studies compared cognitive behavioural therapy to a waiting list control and/or other intervention/s, namely educational, yoga or other psychotherapeutic treatment, in two to four study arms. The assessment tools used in these studies varied greatly, but could be divided in three main groups:

audiological;

psychometric questionnaires and well‐being scales (such as Tinnitus Questionnaire and Tinnitus Handicap Questionnaire); and

subjective score in a tinnitus diary (loudness, tinnitus awareness and tinnitus control etc.).

Cognitive behavioural therapy treatment consisted of six to 11 group sessions (six to eight individuals) of 60 to 120 minutes duration, with a qualified psychologist or student psychologists under supervision (Rief 2005) or the use of a self‐help book and weekly therapist contact (Kaldo 2007). Self‐report questionnaires and diaries (between eight and 12) were used to measure outcomes at pre‐, post‐treatment and follow‐up periods (i.e. three, six, 12 and 18/21 months). Reporting of patients lost during treatment and follow up was good with total drop‐out varying from 4.65% to 21.66%, which would be more than adequate for these types of trials.

All studies aimed to report results at baseline (pre‐treatment), post‐treatment and at follow‐up periods that varied from three to 18 months, however after the initial treatment, the waiting list groups also received CBT thus invalidating any further follow‐up comparisons for the purpose of this review. One study (Kröner‐Herwig 2003) collected follow‐up data on the treatment group only (CBT) as their hypothesis was that the treatment effect would be maintained. In this trial, the authors claim that the improvement on the Tinnitus Questionnaire score (quality of life) was maintained at six months and deteriorated slightly but not significantly at 12 months follow up.

As there were no data in the comparison group in this study and because of the reasons mentioned above for the rest of the studies there are no long‐term follow‐up results available to compare in this review.

Risk of bias in included studies

Allocation bias

Of the eight included studies, two (Henry 1996; Kröner‐Herwig 1995) did not explain the method of randomisation. Allocation concealment was adequate in most studies, only one study (Kröner‐Herwig 1995) divided the treatment group into two arms to have a more balanced four‐arm study (comparing them to yoga and waiting list control), however this was taken into account when extracting data from this study, using a combined mean and standard deviations.

The inclusion/exclusion criteria were clearly defined in all studies. The participants' demographics were comparable throughout all the studies with the exception of a male preponderance (86%) in one study (Henry 1996).

Attrition bias

An acceptable drop‐out rate was considered in this review to be no more than 20%. Two studies (Henry 1996; Kröner‐Herwig 1995) had a drop‐out just above this limit at 21.66% and 20.93%, however this was well accounted for in these trials and affected also other trial arms which were not involved in our data extraction and calculations.

Detection bias

A large number of self‐reported questionnaires and diaries (eight to 12) were used as main assessment outcomes of the treatments imparted in these trials. The adequacy and validation of some of the questionnaires use in these trials was variable, therefore we chose to use some of the more reliable (high internal consistency and test‐retest reproducibility, Baguley 2000) and commonly used questionnaires throughout these trials: the Tinnitus Questionnaire (Hallam 1988; used in Kröner‐Herwig 2003, Zachriat 2004 and Weise 2008), the Tinnitus Handicap Questionnaire (Kuk 1990; used in Henry 1996) and the Tinnitus Reaction Questionnaire (Wilson 1991; used in Andersson 2005 and Kaldo 2007) as standardised and validated instruments to measure global tinnitus severity and its effect on quality of life, and the also validated Beck Depression Inventory (Beck 1961; Beck 1988 and used in Henry 1996 and Weise 2008) and when not available a modified Centre for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES‐D, German translation ADS; Radloff 1977; used in Kröner‐Herwig 2003 ), the Depression scale ("Depressivitäts Skala"; Zerssen 1975; used in Kröner‐Herwig 1995) and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale‐depression subscale (Zigmond 1983; used in Andersson 2005 and Kaldo 2007) to provide a measure of depression of the participants before and after their intervention.

With regards to the assessment of subjective loudness experienced by the participants, this was our only primary outcome and it was reported in seven of the eight studies using numeric visual analogue scales.

Overall quality of the studies was generally good (see 'Characteristics of included studies' table). One study (Rief 2005) was of higher quality than the rest with regards to allocation concealment. All studies had adequate randomisation and ascertainment. All outcomes reported by the studies were subjective and there was no blinding to intervention, so the possibility of bias is present. However this is typical in trials with this type of intervention (CBT).

Effects of interventions

Eight trials comprising 468 participants were included in this review.

We established in our protocol that there would be a primary outcome measure: (1) subjective tinnitus loudness, and two secondary outcome measures: (2) subjective and objective improvement of the symptoms of depression and mood disturbances associated with tinnitus, and (3) evaluation of quality of life for patients (Tinnitus Handicap Questionnaire or other validated assessment method).

The selected control groups for comparison were a waiting list group (participants did not received any intervention) and/or (when available) another intervention (i.e. yoga in Kröner‐Herwig 1995, education in Henry 1996, 'minimal contact ‐ education' in Kröner‐Herwig 2003 and education in Zachriat 2004).

All the data extracted were continuous and measured using different scales and were therefore pooled using standardised mean difference (SMD), with a 95% confidence interval (CI), and visually represented in a forest plot.

The Kröner‐Herwig 1995 trial used CBT in two of the four arm trials (as explained earlier). We pooled the results (means and SD) for these two to obtain a single measure to use in our comparisons.

One trial was excluded from the pooled estimate as the number of participants in each group was not available and further attempts to obtain extra information were unsuccessful (Henry 1998).

Primary outcome

Subjective tinnitus loudness

Seven trials (445 participants) reported subjective loudness pre‐ and post‐treatment on numeric visual analogue scales (VAS), the scores ranging from 0 to 10 points (Kröner‐Herwig 1995; Kaldo 2007; Weise 2008), 0 to 4 points (Henry 1996), 1 to 7 points (Kröner‐Herwig 2003; Zachriat 2004) or 0 to 10 points (Rief 2005).

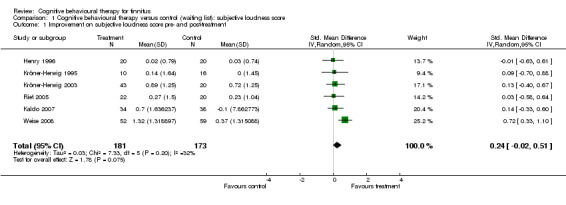

Six studies (354 participants) compared CBT to a waiting list control group. After pooling these studies we found no significant difference in reduction of subjective tinnitus loudness between treatment (cognitive behavioural therapy) and a waiting list control group (SMD 0.24; 95% CI ‐0.02 to 0.51; I2 = 32%).

Four studies (164 participants) compared CBT to another intervention (yoga in Kröner‐Herwig 1995, education in Henry 1996, 'minimal contact ‐ education' in Kröner‐Herwig 2003 and education in Zachriat 2004). After pooling these studies we found no significant difference in reduction of subjective tinnitus loudness between treatment (cognitive behavioural therapy) and other intervention control group (SMD 0.1; 95% CI ‐0.22 to 0.42; I2 = 0%).

Secondary outcomes

Depression

Six trials (379 participants) assessed changes in depression scores pre‐ and post‐treatment on itemised scales ranging from 0 to 100 points ("Depressivitäts Skala": Kröner‐Herwig 1995), 0 to 63 points (Beck Depression Inventory: Henry 1996; Weise 2008), 0 to 60 points (ADS‐German version of the CES‐D; Kröner‐Herwig 2003) and 0 to 21 points (Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale‐depression: Andersson 2005; Kaldo 2007).

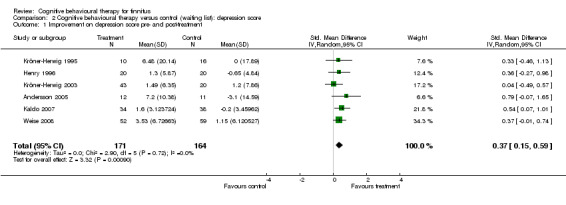

Six studies (335 participants) compared CBT to a waiting list control group, using a depression scale ("Depressivitäts Skala": Kröner‐Herwig 1995), the Beck Depression Inventory (Henry 1996; Weise 2008), the ADS (German version of the CES‐D: Kröner‐Herwig 2003) and the HADS‐depression scale (Andersson 2005, Kaldo 2007). After analysing these studies together, we found a significant difference in reduction of depression score in favour of the treatment group (cognitive behavioural therapy) versus the waiting list control group (SMD 0.37; 95% CI 0.15 to 0.59; I2 = 0%).

Three studies (117 participants), compared CBT to another intervention (yoga in Kröner‐Herwig 1995, education in Henry 1996, and 'minimal contact ‐ education' in Kröner‐Herwig 2003). We found no significant difference in reduction of depression score between treatment (cognitive behavioural therapy) and the other intervention control group (SMD 0.01; 95% CI ‐0.43 to 0.45; I2 = 21%).

Quality of life

This was assessed in six trials (402 participants) using the Tinnitus Handicap Questionnaire (THQ) in one of them (Henry 1996), the Tinnitus Questionnaire (TQ) in three (Kröner‐Herwig 2003; Weise 2008; Zachriat 2004), and the Tinnitus Reaction Questionnaire in the final two (Andersson 2005; Kaldo 2007).

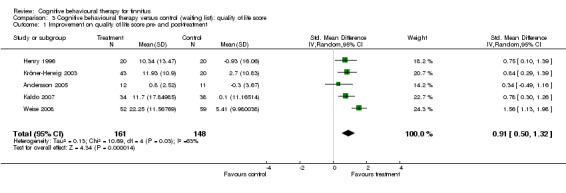

Five studies (309 participants) compared CBT to a waiting list control group. After pooling these studies, data analysis supports a significant difference in favour of the treatment group (CBT) versus the waiting list group (SMD 0.91; 95% CI 0.50 to 1.32; I2 = 63%). This was also highlighted in the individual trial results.

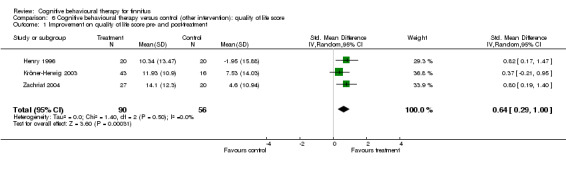

Three studies (146 participants) compared CBT to another intervention (education in Henry 1996, 'minimal contact ‐ education' in Kröner‐Herwig 2003 and education in Zachriat 2004). After pooling these studies we also found a significant difference in favour of the treatment group (cognitive behavioural therapy) versus other intervention control group (SMD 0.64; 95% CI 0.29 to 1.00; I2 = 0%).

Adverse effects

There were no adverse/side effects reported in any trial. Weise 2008 reported results of the adverse effects subscale (M = 1.51; SD = 0.63; range 1 to 6), indicating that "the majority of the patients did not experience negative side effects caused by the treatment".

Sensitivity analysis

As Weise 2008 used biofeedback combined with CBT in the treatment group we carried out a sensitivity analysis.

When comparing CBT versus waiting list the results on the three studied outcomes are:

Subjective tinnitus loudness

Including Weise 2008: effect size SMD 0.24 (95% confidence interval (CI) ‐0.02 to 0.51; I2 (heterogeneity) = 32%). Excluding Weise 2008: effect size 0.09 (95% CI ‐0.17 to 0.34; I2 = 0%).

Depression

Including Weise 2008: effect size SMD 0.37 (CI 0.15 to 0.59; I2 = 0%). Excluding Weise 2008: effect size SMD 0.38 (CI 0.1 to 0.65; I2 = 0%).

Quality of life

Including Weise 2008: effect size SMD 0.91 (CI 0.5 to 1.32; I2 = 63%). Excluding Weise 2008: effect size SMD 0.73 (CI 0.44 to 1.03; I2 = 0%). The effect sizes are therefore similar whether Weise 2008 is included or excluded, however the heterogeneity is much reduced with the study excluded.

Discussion

The objective of this review was to assess whether cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) is effective in the management of patients suffering from tinnitus. As tinnitus itself is usually a subjective experience, our aim throughout the review was to look at subjective improvement in tinnitus and its effect on mood (depression) and overall quality of life.

We chose reduction in tinnitus loudness as our primary outcome as this is the principal goal patients are seeking and it is the eventual aim of many clinical interventions.

A large number of assessment tools (eight to 12) were used in each individual trial, so they generated an even larger list of outcome variables when some subsections of questionnaires or diaries were analysed independently. We used the Tinnitus Questionnaire (TQ; Hallam 1988) and the Tinnitus Handicap Questionnaire (THQ; Kuk 1990) as standardised and validated instruments to measure global tinnitus severity and its effect on quality of life, and the also validated Beck Depression Inventory (BDI; Beck 1961; Beck 1988 and when not available, the validated Centre for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES‐D, German translation ADS, Radloff 1977, the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale ‐ depression (HADS ‐ depression; Zigmond 1983) and the Depression scale ("Depressivitäts Skala", Zerssen 1975), to provide a measure of depression in participants before and after their intervention.

Summary of main results

Tinnitus loudness

This systematic review has found evidence that CBT is unlikely to be effective in improving subjective tinnitus loudness. We feel this is principally because CBT is unlikely to have an effect on any of the postulated pathophysiological causes of tinnitus (e.g. cochlear neurotransmission, central auditory neural pathway). We did not expect to find any effect of behavioural treatment on subjective tinnitus loudness. The aim of behavioural treatment for tinnitus is not to reduce tinnitus loudness but to modify one of three response systems (behaviour, cognition and physiological reactivity) as suggested by the Jastreboff neurophysiological model.

In the absence of a 'cure' for any particular symptom, the role of any health intervention is to improve the patient’s overall condition. In this regard any improvement in quality of life or depression scores in someone who suffers from tinnitus may be considered to be an effective treatment. We found a significant improvement in the scores for both depression and quality of life (decrease of global tinnitus severity) of the participants, suggesting that CBT contributes positively to the management of tinnitus. This effect was observed for comparisons of CBT versus waiting list group (depression) and comparisons of CBT versus waiting list and versus other interventions (quality of life).

Depression

The inclusion of more studies in this updated review has reduced the uncertainty around the estimated effect of CBT on depression associated with tinnitus. The authors of two of the trials (Kröner‐Herwig 2003; Weise 2008) that used depression as study tools found no significant intra‐ and inter‐group changes, with low baseline scores in the depression scales. The authors believe this left little room for improvement and subsequently the treatment had little overall effect. However, the inclusion of additional trials in the update of this review demonstrates that although the overall effect size is maintained (from SMD 0.29 to 0.37), the confidence intervals have considerably narrowed thus causing the effect to become significant.

In our previous review we argued that depression was mainly a significant co‐morbidity in the subgroup of 'severe' tinnitus sufferers and that as these patients are a small proportion of tinnitus sufferers this could explain the failure of these trials to show any overall significant effect of CBT on tinnitus. However, the pooled results in this update now show that there is a clear improvement in the depression scores of tinnitus sufferers in general, supporting the conclusions of other authors who have found CBT to be consistently effective in the treatment of depression (Gelder 2000).

Of all the trials included in this review only two (Andersson 2005; Kaldo 2007) made clear the exclusion criteria for patients with a high score on the depression scales (BDI > 22, or score of > 2 for the 'hopelessness' or 'suicidal ideation' question in Andersson 2005; HADS‐Anxiety or Depression subscales score > 18 in Kaldo 2007). This could introduce bias in the selection process so we performed a sensitivity analysis, removing these two studies from the meta‐analysis of the pooled data. The result was the same significant positive effect on depression score when CBT was compared to no treatment (SMD 0.28; 95% CI 0.02 to 0.54, I2 = 0%). These two studies were not involved in the comparison between CBT and other interventions.

Could our findings suggest anything other than an effect of CBT on depression scales in people with tinnitus? This may well be the case, but if patients are subjectively improved by an intervention then the intervention is likely to be in their interest.

Quality of life

For quality of life, the overall effect of CBT compared to waiting list control group is significantly larger. There is a clinically significant improvement in the sensation of well‐being. It must be noted, however, that the inclusion of the Weise 2008 trial, which is larger than the other trials and also uses CBT plus biofeedback together in the treatment group, potentially had an added effect on the overall pooled result. This trial has an impact on the heterogeneity of the results of CBT versus waiting list group on quality of life (I2 = 63%). For this reason there is uncertainty about the size of the overall effect on quality of life, although it appears to be positive. A post‐hoc sensitivity analysis excluding Weise 2008 from the meta‐analysis shows that the overall effect on depression and quality of life remains unaffected: still significant and in the same direction (depression: SMD 0.38 (95% CI 0.1 to 0.65, I2 = 0%); quality of life: SMD 0.73 (95% CI 0.44 to 1.03, I2 = 0%).

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

In this 2010 update of the review we have increased the number of included trials from six to eight, providing us with enough information to fulfil our review objective.

The participants invited to take part in these studies were recruited from the general population through newspaper, internet or other media adverts (Andersson 2005; Kröner‐Herwig 1995; Kröner‐Herwig 2003; Weise 2008; Zachriat 2004), attending the outpatient department (Henry 1996) or a combination of both methods (Kaldo 2007; Rief 2005). These participants were homogeneously distributed between the different groups of the studies and, with respect to age, sex and the various degrees of severity of both tinnitus and depression associated with tinnitus, could be considered to be representative of the typical patient that attends an outpatient clinic.

It was impossible to analyse long‐term follow up in this review as in all trials that use waiting list control groups, the participants in these groups end up receiving the same treatment after the initial waiting period. This prevents us from drawing any conclusions about the long‐term effect of CBT for tinnitus.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

There is no evidence of an effect of CBT in the improvement of the subjective loudness of tinnitus.

Cognitive behavioural therapy is, however, effective for improving depression associated with tinnitus when compared to no intervention, and for improving overall quality of life (or reducing the global severity of tinnitus) compared to no or other intervention (yoga, education, 'minimal contact ‐ education').

Implications for research.

A consensus should be reached on the use of a limited number of validated questionnaires in a more consistent way for future research in this area.

Longer follow up is necessary to assess the long‐term effect of cognitive behavioural therapy, or other interventions, on tinnitus.

Outcome measures should focus mainly on assessing the impact of any treatment based on the neurophysiological pathway of tinnitus.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 6 May 2010 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | New searches resulted in the inclusion of two new studies. Review conclusions changed. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 2, 2005 Review first published: Issue 1, 2007

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 6 October 2009 | Amended | Standard Background section for tinnitus reviews (Cochrane ENT Group) incorporated. |

| 21 October 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the following authors for their contribution to the standard Background section: Baldo 2006; Bennett 2007; Hilton 2004; Hobson 2007; Phillips 2010.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Search strategies

| PubMed | EMBASE (Ovid) | CINAHL (EBSCO) |

| #1 "Tinnitus"[Mesh] #2 tinnit* [tiab] #3 (EAR* [ti] AND (BUZZ* [tiab] OR RING* [tiab] OR ROAR* [tiab] OR CLICK* [tiab] OR PULS* [tiab])) #4 #1 OR #2 OR #3 #5 "Behavior Therapy"[Mesh] #6 COGNIT* [tiab] AND BEHAV* [tiab] #7 ((COGNIT* [tiab] OR BEHAV* [tiab] OR CONDITIONING OR RELAXATION OR DESENSITI* [tiab]) AND (THERAPY OR THERAPIES OR THERAPEUTIC* [tiab] OR PSYCHOTHERAP* [tiab] OR TRAIN* [tiab] OR RETRAIN* [tiab] OR TREATMENT* [tiab] OR MODIFICATION* [tiab])) #8 DESENSITI* [tiab] AND PSYCHOLOG* [tiab] #9 IMPLOSIVE* [tiab] AND THERAP* [tiab] #10 #5 OR #6 OR #7 OR #8 OR #9 #11 #4 AND #10 | 1 Tinnitus/ 2 tinnit*.tw. 3 (EAR* and (BUZZ* or RING* or ROAR* or CLICK* or PULS*)).ti. 4 1 or 3 or 2 5 behavior modification/ or behavior therapy/ or cognitive therapy/ 6 ((cognit* and behav*) or (DESENSITI* and PSYCHOLOG*) or (IMPLOSIVE* and THERAP*)).tw. 7 ((COGNIT* or BEHAV* or CONDITIONING or RELAXATION or DESENSITI*) and (THERAPY or THERAPIES or THERAPEUTIC* or PSYCHOTHERAP* or TRAIN* or RETRAIN* or TREATMENT* or MODIFICATION*)).tw. 8 6 or 7 or 5 9 8 and 4 | S1 (MH "Tinnitus") S2 TX tinnit* S3 TI (EAR* and (BUZZ* or RING* or ROAR* or CLICK* or PULS*)) S4 S1 OR S2 OR S3 S5 (MH "Behavior Therapy+") S6 TX cognit* AND behav* S7 TX ((DESENSITI* and PSYCHOLOG*) or (IMPLOSIVE* and THERAP*)) S8 TX ((COGNIT* or BEHAV* or CONDITIONING or RELAXATION or DESENSITI*) and (THERAPY or THERAPIES or THERAPEUTIC* or PSYCHOTHERAP* or TRAIN* or RETRAIN* or TREATMENT* or MODIFICATION*)) S9 S5 OR S6 OR S7 OR S8 S10 S4 AND S9 |

| Web of Science | BIOSIS Previews/ CAB Abstracts (Ovid) | CENTRAL |

| #1 TS=tinnit* #2 TS=(EAR* and (BUZZ* or RING* or ROAR* or CLICK* or PULS*)) #3 #2 OR #1 #4 TS=(cognit* AND behav*) #5 TS=((DESENSITI* and PSYCHOLOG*) or (IMPLOSIVE* and THERAP*)) #6 TS=((COGNIT* or BEHAV* or CONDITIONING or RELAXATION or DESENSITI*) and (THERAPY or THERAPIES or THERAPEUTIC* or PSYCHOTHERAP* or TRAIN* or RETRAIN* or TREATMENT* or MODIFICATION*)) #7 #6 OR #5 OR #4 #8 #7 AND #3 | 1 tinnit*.tw. 2 (EAR* and (BUZZ* or RING* or ROAR* or CLICK* or PULS*)).ti. 3 1 or 2 4 ((cognit* and behav*) or (DESENSITI* and PSYCHOLOG*) or (IMPLOSIVE* and THERAP*)).tw. 5 ((COGNIT* or BEHAV* or CONDITIONING or RELAXATION or DESENSITI*) and (THERAPY or THERAPIES or THERAPEUTIC* or PSYCHOTHERAP* or TRAIN* or RETRAIN* or TREATMENT* or MODIFICATION*)).tw. 6 4 OR 5 7 3 AND 6 | #1 TINNITUS single term (MeSH) #2 TINNIT* #3 EAR* NEAR (BUZZ* OR RING* OR ROAR* OR CLICK* OR PULS*) #4 #1 OR #2 OR #3 #5 BEHAVIOR THERAPY explode all trees (MeSH) #6 COGNIT* AND BEHAV* #7 (COGNIT* OR BEHAV* OR CONDITIONING OR RELAXATION OR DESENSITI*) AND (THERAP* OR PSYCHOTHERAP* OR TRAIN* OR RETRAIN* OR TREATMENT* OR MODIFICATION*) #8 DESENSITI* NEAR PSYCHOLOG* #9 IMPLOSIVE NEAR THERAP* #10 #5 OR #6 OR #7 OR #8 OR #9 #11 #4 AND #10 |

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Cognitive behavioural therapy versus control (waiting list): subjective loudness score.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Improvement on subjective loudness score pre‐ and post‐treatment | 6 | 354 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.24 [‐0.02, 0.51] |

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Cognitive behavioural therapy versus control (waiting list): subjective loudness score, Outcome 1 Improvement on subjective loudness score pre‐ and post‐treatment.

Comparison 2. Cognitive behavioural therapy versus control (waiting list): depression score.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Improvement on depression score pre‐ and post‐treatment | 6 | 335 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.37 [0.15, 0.59] |

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Cognitive behavioural therapy versus control (waiting list): depression score, Outcome 1 Improvement on depression score pre‐ and post‐treatment.

Comparison 3. Cognitive behavioural therapy versus control (waiting list): quality of life score.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Improvement on quality of life score pre‐ and post‐treatment | 5 | 309 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.91 [0.50, 1.32] |

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Cognitive behavioural therapy versus control (waiting list): quality of life score, Outcome 1 Improvement on quality of life score pre‐ and post‐treatment.

Comparison 4. Cognitive behavioural therapy versus control (other intervention): subjective loudness score.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Improvement on subjective loudness score pre‐ and post‐treatment | 4 | 164 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.10 [‐0.22, 0.42] |

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Cognitive behavioural therapy versus control (other intervention): subjective loudness score, Outcome 1 Improvement on subjective loudness score pre‐ and post‐treatment.

Comparison 5. Cognitive behavioural therapy versus control (other intervention): depression score.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Improvement on depression score pre‐ and post‐treatment | 3 | 117 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.01 [‐0.43, 0.45] |

5.1. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Cognitive behavioural therapy versus control (other intervention): depression score, Outcome 1 Improvement on depression score pre‐ and post‐treatment.

Comparison 6. Cognitive behavioural therapy versus control (other intervention): quality of life score.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Improvement on quality of life score pre‐ and post‐treatment | 3 | 146 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.64 [0.29, 1.00] |

6.1. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Cognitive behavioural therapy versus control (other intervention): quality of life score, Outcome 1 Improvement on quality of life score pre‐ and post‐treatment.

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Andersson 2005.

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial | |

| Participants | 23 (of 37 initially recruited) participants (12 male), mean age 70.1 years (range 65 to 79), allocated to 2 groups: CBT (12 patients) and waiting list control (11 patients) Inclusion criteria were: (1) Patient should have problems with their tinnitus (2) Duration of tinnitus for at least 6 months and (3) Being able to attend the sessions, including walking up the stairs to attend the sessions Exclusion criteria were: (1) Previous psychological treatment for tinnitus (2) Depression score above 22 on BDI (3) A score above 2 on item 2 (hopelessness) and item 9 (suicidal ideation) (4) Had medical reasons for not taking part in the treatment |

|

| Interventions | Two groups: (1) A treatment group of CBT (12 patients) (2) A waiting list control group (11 patients) | |

| Outcomes | Four outcome measures:

(1) The Tinnitus Reaction Questionnaire (TRQ)

(2) The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS)

(3) The Anxiety Severity Index (ASI)

(4) A Visual Analogue Scale for tinnitus annoyance, loudness and quality of sleep Comparisons were made at pre‐ and post‐treatment points. Also at 3 months follow up the outcomes were compared, but at this point the data were non‐experimental, as the waiting list group had also received CBT after the post‐treatment observations. |

|

| Notes | There were no drop‐outs. Outcomes were measured pre‐ and post‐treatment (6 weeks), then the waiting list group received the same treatment, so follow‐up results at 3 months cannot be used. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Henry 1996.

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial | |

| Participants | 60 (of 65 initially recruited) patients (52 male, mean age 64 years) allocated to 3 groups: 20 patients in each group Inclusion criteria were: (1) Chronic tinnitus of more than 6 months duration (2) Tinnitus assessed by both otolaryngologist and audiologist (3) Traditional treatments not recommended or had failed (4) No hearing aid, masker or medication for tinnitus in the previous 6 months (5) At least 17 points on the TRQ (6) English literacy (7) Willingness to participate in a research programme |

|

| Interventions | Three experimental conditions: (1) Combined cognitive educational programme (2) Education alone (both treatments involved a 90‐minute session per week for 6 weeks, given by the same clinical psychologists, in groups of 5 to 7 participants) (3) A waiting‐list control | |

| Outcomes | Self‐report questionnaires administered at pre‐treatment, post‐treatment and 12 months follow up: TRQ, THQ, TEQ, TCQ, TCSQ, TKQ, BDI, LCB and a Self‐Monitoring of Tinnitus record, including: loudness, notice and bother by tinnitus | |

| Notes | The number of patients that were lost to the 12‐month follow up was 13 (4 in the 'cognitive education', 3 in the education alone and 6 in the waiting list group). Total drop‐out at 12‐month follow up = 13/60 = 21.66%. There were no adverse effects reported. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Kaldo 2007.

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial | |

| Participants | 72 (of initially 101 recruited) participants allocated into 2 groups: treatment group (50% female, mean age 45.9 years) and waiting list group (47% female, mean age 48.5 years) Inclusion criteria were: (1) Medical examination by ENT specialist or an audiological physician (2) Tinnitus duration more than 6 months duration (3) Ability to read and understand the self‐help book (4) Must be likely to complete the self‐help process (5) Above 18 years of age (6) At least 10 points on the TRQ (7) Score of 18 or below on both the anxiety and depression subscales of HADS |

|

| Interventions | Two groups: (1) A treatment group of CBT (34 patients). This was administered by a self‐help book and 7 weekly phone calls from a therapist over a period of 6 weeks (2) A waiting list control group (38 patients) | |

| Outcomes | Self‐report questionnaires administered at pre‐treatment, post‐treatment and 12 months follow up: TRQ, THI, HADS, ISI and a daily diary recording of tinnitus on visual analogue scales, including loudness, distress and perceived stress during the day | |

| Notes | Total drop‐out at 12‐month follow up = 12%. There were no adverse effects reported. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | Randomisation by coin tossing |

Kröner‐Herwig 1995.

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial. Randomisation by drawing code numbers from a basket with the total sample. | |

| Participants | 43 (of 52 initially recruited) patients (60.5% male, mean age 48 years) allocated to 4 groups Inclusion criteria were: (1) Duration of tinnitus more than 6 months (2) Impairment due to tinnitus > 4 on a 10‐point rating scale (3) Hearing ability adequate for communication purposes (4) No treatable organic or psychological pathology (5) No current psychotherapy (6) Completed medical examination (7) Willingness to participate in the assessment and at least 8 to 10 treatment sessions |

|

| Interventions | Four experimental groups:

(1) Tinnitus Coping Training 1 (TCT1 = 7 patients)

(2) Tinnitus Coping Training 2 (TCT2 = 8 patients)

(3) Yoga training (9 patients)

(4) A waiting list control (WLC = 19 patients) Each treatment group (TCT1, TCT2, yoga) consisted of 10 2‐hourly sessions; each group was conducted by a different qualified professional |

|

| Outcomes | The outcome measures included:

(1) Audiological: Tinnitus Sensation Level (TSL), Tinnitus Masking Level (TML)

(2) Self‐monitoring tinnitus diary: subjective loudness, tinnitus discomfort, sleep disturbance, interference with activity, control of tinnitus and hours per day of tinnitus ignored

(3) Self‐report questionnaires: TQ, and well‐being variables: depression, mood and symptoms All assessments were completed at pre‐treatment, post‐treatment and 3 months follow up (the latter one except for audiological outcomes) |

|

| Notes | The number of patients that were lost was 9 (3 in TCT1, 2 in TCT2t, 1 in yoga and 3 in the WLC). Total drop‐out = 9/43 = 20.93%. There were no adverse effects reported. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | Randomisation by drawing code numbers from a basket with the total sample |

Kröner‐Herwig 2003.

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial. Randomisation by drawing code numbers from the total sample and the sequential assignment to the treatment conditions until a pre‐set number of subjects was reached. | |

| Participants | 95 (of 116 initially recruited) patients (51.6% female, mean age 46.8 years) allocated to 4 groups Inclusion criteria were: (1) Age between 18 and 65 years (2) Duration of tinnitus more than 6 months (3) Medical diagnosis of 'idiopathic' (unknown) tinnitus (4) Tinnitus being their main health problem, with subjective annoyance rating of > 40 (out 100) on 9 scales assessing disruptive effects of tinnitus Exclusion criteria were: (1) Ménière's disease (2) Hearing loss preventing from participating in communication within groups (3) Current psychotherapeutic treatment |

|

| Interventions | Four experimental groups:

(1) Tinnitus Coping Training (TCT = 43 patients)

(2) 'Minimal contact ‐ education' (MC‐E = 16 patients)

(3) Minimal Contact ‐ Relaxation (MC‐R = 16 patients)

(4) A waiting list control (WLC = 20 patients) TCT comprised 11 sessions of 90 to 120 minutes duration, each group consisted of 6 to 8 patients and was conducted by 2 qualified psychologists MC‐E comprised of 2 group sessions (of education and self‐help strategies for coping with tinnitus) 4 weeks apart while 'self‐help exercises' were undertaken MC‐R consisted of an educational session in relaxation and distraction, followed by a second session were patients received audio cassettes with relaxing music and instructions, then a further 2 sessions to discuss progress. Patients in MC‐E and MC‐R were told they could join in TCT after post‐treatment assessment. All assessments were completed at pre‐treatment, post‐treatment 6 and 12 months follow up |

|

| Outcomes | The outcome measures included: (1) Self‐monitoring tinnitus diary (during 2 weeks period at pre‐, post‐treatment and 6 months follow up): loudness, tinnitus awareness and subjective control of tinnitus (2) Psychometric questionnaires: TQ (only instrument used at 12‐month follow up), TDQ , a German coping inventory (COPE), SCL‐90R and a German depression scale (ADS), a questionnaire of subjective change in tinnitus‐related variables (loudness, disability, awareness, control, ignoring) and general well‐being variables: physical well‐being, activities, mood and stress coping). All assessments were completed at pre‐treatment, post‐treatment and 6 months follow up, Tinnitus Questionnaire was the only assessment used at 12 months follow up (3) Audiological variables (tinnitus masking level, tinnitus sensation level) are only measured in the pre‐treatment period | |

| Notes | The number of patients lost was 21 (13 in the TCT group, 4 in MC‐E and MC‐R each). Total drop‐out = 21/95 = 22.1%. There were no adverse effects reported. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Rief 2005.

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial. Randomisation by a list of random sequence. | |

| Participants | 43 (of 48 initially recruited) patients (46.75% female, mean age 46.75 years) allocated to 2 groups Inclusion criteria were: (1) Duration of tinnitus more than 6 months (2) Participants agreed that the tinnitus was disturbing, with a subjective annoyance rating of > 3 (on a visual analogue scale from 0 to 10) |

|

| Interventions | Two experimental groups:

(1) Psychophysiologically‐oriented intervention (23 patients)

(2) A waiting list control (WLC = 20 patients) The psychophysiologically‐oriented intervention comprised 9 sessions of 60 minutes duration conducted by 5 supervised graduate student psychologists All assessments were completed at pre‐treatment, post‐treatment (8 weeks) and 6 months follow up |

|

| Outcomes | The outcome measures included:

(1) Psychometric questionnaires: TQ, STI, IDCL, SCL‐90R, self‐efficacy

(2) Tinnitus diary (3 times a day, during 1‐week period at pre‐, post‐treatment and 6 months follow up): subjective loudness, tinnitus awareness and subjective control of tinnitus All assessments were completed at pre‐treatment, post‐treatment and 6 months follow up |

|

| Notes | The number of patients that were lost at the post‐treatment point was 1 (in the intervention group) and 1 more drop‐out (in the control group) occurred at the first follow‐up point. Total drop‐out = 2/43 = 4.65%. There were no adverse effects reported. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Weise 2008.

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial | |

| Participants | 111 (of 130 initially recruited) patients allocated to 2 groups: treatment group (44.2% female, mean age 49.46 years) and waiting list group (44.1% female, mean age 52.93 years) Inclusion criteria were: (1) Duration of tinnitus greater than 6 months (2) Serious or severe tinnitus annoyance (TQ score = 47 or more) (3) Between 16 and 75 years of age Exclusion criteria were: (1) Mild degree of tinnitus annoyance (2) Tinnitus following Ménière's disease (3) Patients with psychosis or seriously disabling brain damage |

|

| Interventions | Two experimental groups:

(1) Biofeedback‐based behavioural intervention (52 patients)

(2) A waiting list control (59 patients) The biofeedback‐based behavioural intervention consisted of 12 individual therapy sessions of 60 minutes duration conducted by 4 trained therapists. Each session contained biofeedback as well as CBT elements following a structured manual. |

|

| Outcomes | The outcome measures included:

(1) Global tinnitus annoyance measured with TQ

(2) Tinnitus diary (for 1 week at each assessment point) on a Visual Analogue Scale (0 to 10) including: subjective loudness, sleep disturbance, impairment, distress due to tinnitus and feelings of controllability

(3) Psychometric questionnaires: BDI, SCL‐90‐R, GSI, TRSS, TRCS All assessments were completed at pre‐treatment, post‐treatment and 6 months follow up |

|

| Notes | Total drop‐out at post‐treatment measurement = 19/130 = 14.61%. Results for the adverse effects subscale (M = 1.51; SD = 0.63; range 1 to 6) indicated that the majority of the patients did not experience negative side effects caused by the treatment. Results for the satisfaction with therapy subscale (M = 5.16, SD = 0.51; range 1 to 6) indicated that patients were quite content with the treatment. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | Randomisation using a computer‐generated random list |

Zachriat 2004.

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial. Randomisation by throwing dice. | |

| Participants | 77 (of 83 initially recruited) patients (66.6% male, mean age 53.8 years) allocated to 3 groups Inclusion criteria were: (1) Duration of tinnitus more than 3 months (2) Absence of a treatable organic cause of tinnitus (3) Absence of Ménière's disease (4) Hearing capacity for communication within groups (5) Tinnitus disability score > 25 on TQ (6) No ongoing psychotherapy or masker treatment |

|

| Interventions | Three experimental groups:

(1) Tinnitus Coping Training (TCT = 29 patients)

(2) Habituation‐based treatment (HT = 31 patients)

(3) Educational intervention (EDU = 23 patients) TCT comprised 11 sessions of 90 to 120 minutes duration, each group consisted of 6 to 8 patients. There was a 4‐week recess between the first and second session of TCT and HT to assess the effect of education alone, and then TCT and HT continued. HT was conducted in 5 sessions of 90 to 120 minutes (spaced over 6 months) to a group of 6 to 8 patients, where education, noise generator and counselling was conducted. Education consisted in a single session informing about the physiology and psychology of tinnitus. This session was identical to the first session for TCT and very similar to the HT one. Patients in EDU group were also offered a further treatment after 15 weeks should they wish. All groups were conducted by 5 qualified psychologist therapists. Assessments were carried out at 7 measurement periods: at pre‐treatment, post‐treatment, 6, 12 and 18 (21 for TCT) months follow up |

|

| Outcomes | The outcome measures included:

(1) Self‐monitoring tinnitus diary (3 times per day during 1‐week period): loudness, hours of tinnitus awareness and subjective control of tinnitus

(2) Psychometric questionnaires: TQ, Tinnitus Coping Questionnaire, QCC, QDC, JQ, a German questionnaire in changes in well‐being and adaptive behaviour (VEV), SSR, SCL‐90R and Minimal Diagnostic Interview of Psychological Disorders (DSM‐III‐R) Most variables were assessed at pre‐ and post‐treatment periods; the TQ was the only one applied at every time period Objective tinnitus parameters (pitch masking and masking measurements) were excluded from the study |

|

| Notes | The number of patients that were lost before the post‐treatment period was 6 (2 in the TCT group, 1 in HT group and 3 in EDU group). A further 2 drop‐outs (one in TCT and one in HT group) occurred at 18 months follow up (21 months for the TCT group). Total drop‐out = 8/77 = 10.38%. There were no adverse effects reported. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | Randomisation by throwing dice |

ATQ = Automatic Thoughts Questionnaire; BDI = Beck Depression Inventory; DB = double‐blind; IDCL = International Diagnostic Check‐List; ISI = Insomnia Severity Index; JQ = Jastreboff Questionnaire; LCB = Locus of Control of Behavior Scale; QCC = Questionnaire of Catastrophizing Cognitions; QDC = Questionnaire of Dysfunctional Cognitions; QS = quality score; R = randomisation; SCL‐90R = Symptom Checklist; SSR = Questionnaire of Subjective Success; STI = Structured Tinnitus Review; TCQ = Tinnitus Cognitions Questionnaire; TCSQ = Tinnitus Coping Strategies Questionnaire; TDQ = Tinnitus Disability Questionnaire; TEQ = Tinnitus Effect Questionnaire; THI = Tinnitus Handicap Inventory; THQ = Tinnitus Handicap Questionnaire; TKQ = Tinnitus Knowledge Questionnaire; TQ = Tinnitus Questionnaire; TRCS = Tinnitus Related Control Scale; TRQ = Tinnitus Reaction Questionnaire; TRSS = Tinnitus‐related Self‐Statement Scale; W = withdrawals

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Abbott 2009 | ALLOCATION: Randomised PARTICIPANTS: High drop‐out (50%) |

| Andersson 2002 | ALLOCATION: Randomised PARTICIPANTS: High drop‐out (51% in the CBT group) |

| Davies 1995 | ALLOCATION: Randomised PARTICIPANTS: High drop‐out (43.33%) |

| Delb 2002 | ALLOCATION: Not randomised |

| Goebel 2000 | ALLOCATION: Randomised PARTICIPANTS: Patients with tinnitus INTERVENTION: Not CBT |

| Henry 1998 | ALLOCATION: Randomised PARTICIPANTS: Patients with tinnitus INTERVENTION: CBT OUTCOME: No usable data. No primary outcome |

| Hiller 2004 | ALLOCATION: Inadequate randomisation, as patients with severe tinnitus (Tinnitus Questionnaire score > 40) were allocated to CBT and those with lower scores to the Tinnitus Education group. The randomisation was then done for receiving (or not) noise generators. |

| Jakes 1986 | ALLOCATION: Not randomised |

| Jakes 1992 | ALLOCATION: Randomised PARTICIPANTS: High drop‐out (44.8%) |

| Kaldo 2008 | ALLOCATION: Randomised PARTICIPANTS: Patients with tinnitus INTERVENTION: Internet CBT versus CBT. Not an appropriate comparison for this review. |

| Kröner‐Herwig 1999 | ALLOCATION: Randomised PARTICIPANTS: High drop‐out (39.53%) |

| Kröner‐Herwig 2006 | ALLOCATION: Randomised PARTICIPANTS: Patients with tinnitus INTERVENTION: Cognitive behavioural tinnitus coping training (TCT) versus Habituation‐based Training (HT) OUTCOME: This study looks at possible predictor factors in the participants from another already published 3‐arm trial (Zachriat 2004) which was already included in this review. Not an appropriate comparison for this review. |

| Lindberg 1987 | ALLOCATION: Not randomised |

| Lindberg 1988 | ALLOCATION: Not randomised |

| Lindberg 1989 | ALLOCATION: Randomised PARTICIPANTS: Patients with tinnitus INTERVENTIONS: Not CBT |

| Robinson 2008 | ALLOCATION: Randomised PARTICIPANTS: High drop‐out (37%) |

| Sadlier 2008 | ALLOCATION: Not randomised |

| Scott 1985 | ALLOCATION: Randomised PARTICIPANTS: Patients with tinnitus INTERVENTIONS: Not CBT |

| Wise 1998 | ALLOCATION: Randomised PARTICIPANTS: Patients with tinnitus INTERVENTIONS: Not CBT |

Characteristics of ongoing studies [ordered by study ID]

Kendall 2009.

| Trial name or title | Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) for tinnitus |

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial (single‐blind) |

| Participants | All subjects will be veterans currently receiving care at VACHS Inclusion criteria: (1) Moderate to severe tinnitus > 6 months (2) Motivation to complete the study Exclusion criteria: (1) Tinnitus Impact Screening Interview (TISI) < 4 (2) Semi‐Structured Clinical Interview for Tinnitus (3) Indication of psychosis on Structured Clinical Interview for Diagnosis (SCIDa‐I/NP) (4) Tinnitus Handicap Inventory (THI) < 19 (5) Tinnitus Reaction Questionnaire (TRQ) < 16 (6) Subjects undergoing litigation related to auditory disorders (7) Previous psychological treatment for tinnitus (8) Previous traumatic brain injury with loss of consciousness (9) Otherwise treatable tinnitus (10) History of psychotic disorders or dementia (11) Recent history of alcohol or drug abuse (12) Subjects using a hearing aid (13) Sudden or fluctuating hearing loss (14) Tinnitus associated with otological disease (i.e. Ménière's) or co‐occurring vestibular dysfunction |

| Interventions | Two groups: (1) Education (2) CBT + education |

| Outcomes | Primary outcome: Tinnitus Handicap Inventory (THI). Eligibility pre‐treatment, post‐treatment, 8 weeks post‐treatment Secondary outcome: Tinnitus Reaction Questionnaire (TRQ). Eligibility, pre‐treatment, post‐treatment, 8 weeks post‐treatment. |

| Starting date | February 2009 |

| Contact information | Caroline J Kendall, Robert D Kerns. Department of Veterans Affairs. VA Connecticut Health Care System, West Haven, Connecticut, USA E‐mail: Caroline.Kendall@va.gov |

| Notes | — |

Zenner 2010.

| Trial name or title | Randomized controlled clinical trial of efficacy and safety of individual cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) within the setting of the structured therapy programme sTCP (STructured Tinnitus Care Program) in patients with tinnitus aurium |

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial |

| Participants | Inclusion criteria: (1) Tinnitus > 11 weeks (2) Normal examination, eardrum mobility and stapedial reflex (3) Ability to fill out questionnaires (4) Gap between sound pressure level (SPL) in audiometric tinnitus matching and tinnitus loudness Exclusion criteria: (1) Pulsatile, intermittent or non‐persistent tinnitus (2) Tinnitus concomitant to systemic disease (i.e. vestibular schwannoma, Ménière's...) (3) Known retrocochlear hearing defect (4) Conductive hearing loss > 10 dB at 2 or more frequencies (5) Middle ear effusion, total deafness or cranial trauma (6) Previous tinnitus treatment with maskers, psychotherapy, acupuncture or drugs (7) Neurological disease, alcohol abuse, severe ischaemic disorder (8) Non‐availability for visits (9) Insufficient command of German language |

| Interventions | Individual application of structured and tinnitus specific cognitive behavioral therapy intervention procedures in the clinical setting of the structured therapy programme "tinnitus care program (TCP)" Duration of intervention per patient: 1 to 15 treatment sessions plus self‐treatment up to 16 weeks Control intervention: waiting group (16 weeks) |

| Outcomes | Primary outcome: Tinnitus Change Score (8‐point numerical scale) Secondary outcomes: Tinnitus Questionnaire Score (TQS), Tinnitus Loudness Score (TLS) and Tinnitus Annoyance Score (TAS) (6 to 8‐point numerical verbal scales) |

| Starting date | — |

| Contact information | hans‐peter.zenner@med.uni‐tuebingen.de |

| Notes | — |

BDI = Beck Depression Inventory HRSD = Hamilton Rating Scale of Depression ITHQ = Iowa Tinnitus Handicap Questionnaire MSPQ = Modified Somatic Perception Questionnaire PSCS = Private Self Consciousness Scale SCL‐90R = Symptom Check List 90R TEQ = Tinnitus Effect Questionnaire THI = Tinnitus Handicap Inventory TRQ = Tinnitus Reaction Questionnaire

Contributions of authors

All authors contributed to the drafting of the protocol. PMD carried out the search and together with AW and MT selected the included studies. RP and PMD contributed to the statistical methods and the meta‐analysis. All authors contributed to the final text of the review.

Declarations of interest

None known.

Edited (conclusions changed)

References

References to studies included in this review

Andersson 2005 {published data only}

- Andersson G, Porsaeus D, Wiklund M, Kaldo V, Larsen HC. Treatment of tinnitus in the elderly: a controlled trial of cognitive behavior therapy. International Journal of Audiology 2005;44(11):671‐5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Henry 1996 {published data only}

- Henry JL, Wilson PH. The psychological management of tinnitus: comparison of a combined cognitive educational program, education alone and a waiting‐list control. International Tinnitus Journal 1996;2:9‐20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kaldo 2007 {published data only}

- Kaldo V, Cars S, Rahnert M, Larsen HC, Andersson G. Use of a self‐help book with weekly therapist contact to reduce tinnitus distress: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Psychosomatic Research 2007;63:195–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kröner‐Herwig 1995 {published data only}

- Kröner‐Herwig B, Hebing G, Rijn‐Kalkman U, Frenzel A, Schilkowsky G, Esser G. The management of chronic tinnitus ‐ comparison of a cognitive‐behavioural group training with yoga. Journal of Psychosomatic Research 1995;39(2):153‐65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kröner‐Herwig 2003 {published data only}

- Kröner‐Herwig B, Frenzel A, Fritsche G, Schilkowsky G, Esser G. The management of chronic tinnitus: comparison of an outpatient cognitive‐behavioral group training to minimal‐contact interventions. Journal of Pyschosomatic Research 2003;54(4):381‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Rief 2005 {published data only}

- Rief W, Weise C, Kley N, Martin A. Psychophysiologic treatment of chronic tinnitus: a randomized clinical trial. Psychosomatic Medicine 2005;67(5):833‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Weise 2008 {published data only}

- Weise C, Heinecke K, Rief W. Biofeedback‐based behavioral treatment for chronic tinnitus: results of a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 2008;76(6):1046‐57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Zachriat 2004 {published and unpublished data}

- Zachriat C, Kröner‐Herwig B. Treating chronic tinnitus: comparison of cognitive‐behavioural and habituation‐based treatments. Cognitive Behavioural Therapy 2004;33(4):187‐98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to studies excluded from this review

Abbott 2009 {published data only}

- Abbott JA, Kaldo V, Klein B, Austin D, Hamilton C, Piterman L, et al. A cluster randomised trial of an internet‐based intervention program for tinnitus distress in an industrial setting. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy 2009;38(3):162‐73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Andersson 2002 {published data only}

- Andersson G, Stromgren T, Strom L, Lyttkens L. Randomized controlled trial of internet‐based cognitive behavior therapy for distress associated with tinnitus. Psychosomatic Medicine 2002;64:810‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Davies 1995 {published data only}

- Davies S, McKenna L, Hallam RS. Relaxation and cognitive therapy: a controlled trial in chronic tinnitus. Psychology and Health 1995;10:129‐43. [Google Scholar]

Delb 2002 {published data only}

- Delb W, D'Amelio R, Boisten CJM, Plinkert PK. Evaluation of the tinnitus retraining therapy as combined with a cognitive behavioural group therapy. HNO 2002;50(11):997‐1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Goebel 2000 {published data only}

- Goebel G, Rubler D, Hiller W, Heuser J, Fitcher MM. Evaluation of tinnitus retraining therapy in comparison to cognitive therapy and broad‐band noise generator therapy. Laryngo‐Rhino‐Otologie 2000;79 (Suppl 1):S88. [Google Scholar]

Henry 1998 {published data only}

- Henry JL, Wilson PH. An evaluation of two types of cognitive intervention in the management of chronic tinnitus. Scandinavian Journal of Behaviour Therapy 1998;27(4):156‐66. [Google Scholar]

Hiller 2004 {published data only}

- Hiller W, Haerkotter C. Does sound stimulation have additive effects on cognitive‐behavioural treatment of chronic tinnitus?. Behaviour Research and Therapy 2005;43 (5):595‐612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Jakes 1986 {published data only}