Abstract

We have studied the role of individual histone N-termini and the phosphorylation of histone H3 in chromosome condensation. Nucleosomes, reconstituted with histone octamers containing different combinations of recombinant full-length and tailless histones, were used as competitors for chromosome assembly in Xenopus egg extracts. Nucleosomes reconstituted with intact octamers inhibited chromosome condensation as efficiently as the native ones, while tailless nucleosomes were unable to affect this process. Importantly, the addition to the extract of particles containing only intact histone H2B strongly interfered with chromosome formation while such an effect was not observed with particles lacking the N-terminal tail of H2B. This demonstrates that the inhibition effect observed in the presence of competitor nucleosomes is mainly due to the N-terminus of this histone, which, therefore, is essential for chromosome condensation. Nucleosomes in which all histones but H3 were tailless did not impede chromosome formation. In addition, when competitor nucleosome particles were reconstituted with full-length H2A, H2B and H4 and histone H3 mutated at the phosphorylable serine 10 or serine 28, their inhibiting efficiency was identical to that of the native particles. Hence, the tail of H3, whether intact or phosphorylated, is not important for chromosome condensation. A novel hypothesis, termed ‘the ready production label’ was suggested to explain the role of histone H3 phosphorylation during cell division.

Keywords: chromosome/condensation/H3 phosphorylation/histone H2B/histone tails

Introduction

Although mitotic chromosomes were described more than a century ago, their structure and assembly are still poorly understood. However, during the last few years real progress towards the understanding of the complex process of chromosome formation has been made thanks to two complementary approaches: genetics in yeast and biochemical manipulations in extracts isolated from Xenopus eggs (for a recent review see Hirano, 2000). This last approach has been extremely useful since the in vitro condensed chromosomes can be manipulated in their natural conditions allowing a causal relationship between the different events involved in their assembly to be studied. In addition, the structure and properties of these chromosomes are identical to those formed in cells in culture (Houchmandzadeh et al., 1997; Houchmandzadeh and Dimitrov, 1999; Poirier et al., 2000). Therefore, the dissection of the mechanism of chromosome condensation in the Xenopus egg extract is relevant to the study of physiological mechanisms operating in vivo. Indeed, the use of the extracts has allowed the identification and isolation of the condensin complex, which is required for chromosome condensation (Hirano and Mitchison, 1994; Hirano et al., 1997; Hirano, 2000). This complex exists in vertebrate somatic cells and in yeast and is associated with chromatin exclusively during mitosis, as observed in the case of Xenopus egg extracts (Hirano and Mitchison, 1994; Saitoh et al., 1994; Sutani et al., 1999). Moreover, the study of chromosome assembly in these extracts showed that topoisomerase II had an enzymatic but not a structural role in the maintenance of mitotic chromosome organization (Hirano and Mitchison, 1993).

The basic unit of chromatin, the nucleosome, contains an octamer of core histones (two each of H2A, H2B, H3 and H4) around which two superhelical turns of DNA are wrapped. The crystallographic structure of both the histone octamer and the whole nucleosome has been solved. Each histone within the octamer consists of a structured domain (the histone fold) and non-structured N-terminal tails (Arents et al., 1991; Luger et al., 1997). The linker histone interacts mainly with the linker DNA between the nucleosomes.

Since the early seventies it has been assumed that linker histones were main players in chromosome condensation (Bradbury et al., 1973; Bradbury, 1992). However, more recent experiments have shown that their absence affected neither chromosome condensation nor nucleus assembly both in Xenopus egg extract (Ohsumi et al., 1993; Dasso et al., 1994) and in vivo (Shen et al., 1995; Shen and Gorovsky, 1996; Barra et al., 2000). These data argued strongly against the above hypothesis. In contrast, it has recently been reported that the flexible N-termini of core histones play an essential role in chromosome assembly (de la Barre et al., 2000).

The N-terminal tails of histones are subjected to a large number of post-translational modifications, which are believed to have important functions in numerous cellular processes (reviewed in Wolffe and Hayes, 1999; Cheung et al., 2000; Strahl and Allis, 2000; Turner, 2000). During the last few years particular attention has been paid to the phosphorylation of the histone H3 tail at serine 10. In fact, this modification was observed in two different processes: the first is the activation of transcription (Mahadevan et al., 1991; Thomson et al., 1999a,b), which requires substantial chromatin decompaction, and the second is chromosome assembly during mitosis and meiosis (Hendzel et al., 1997; Van Hooser et al., 1998; Wei et al., 1998, 1999; de la Barre et al., 2000; Hsu et al., 2000; Kaszas and Cande, 2000; Adams et al., 2001; Giet and Glover, 2001). The function of histone H3 phosphorylation is not clear. Indeed, during cell division histone H3 phosphorylation was related either to chromosome condensation (Hendzel et al., 1997; Wei et al., 1998, 1999; Hsu et al., 2000) or to chromosome cohesion (Kaszas and Cande, 2000). However, in both cases the evidence was mostly correlative. For example, during mitosis in cultured vertebrate cells, the phosphorylation of histone H3 occurred in a precise spatio-temporal order (Hendzel et al., 1997; Van Hooser et al., 1998; Sauve et al., 1999). Indeed, initially detected in late G2 phase on pericentromeric heterochromatin, it spreads along the chromosome arms as mitosis proceeds. A correlation was observed between the initial chromatin condensation and the phosphorylation of histone H3 (Hendzel et al., 1997; Van Hooser et al., 1998). In plants, however, H3 phosphorylation in both mitosis and meiosis was initiated on already compacted chromosomes, a finding arguing against a role of this H3 modification in chromosome condensation (Kaszas and Cande, 2000). Instead, experiments with wild-type and mutant maize, where chromatid cohesion at metaphase II was absent, strongly suggested an association of histone H3 phosphorylation with chromosome cohesion (Kaszas and Cande, 2000).

The Xenopus sperm nucleus DNA is tightly packaged through interactions with the histones H3 and H4 (present in equimolar amounts in sperm nuclei, for details see Dimitrov and Wolffe, 1995) and protamine-like proteins (Philpott et al., 1991; Dimitrov et al., 1994). Upon incubation in the egg extract, the demembranated sperm nuclei undergo a complete remodeling (Dimitrov and Wolffe, 1995, 1996). During the first 5–10 min, a dramatic decondensation takes place, followed by a series of well defined condensation steps culminating in the formation of compact chromosomes (Lohka and Masui, 1983; Hirano and Mitchison, 1993; de la Barre et al., 1999). The chromosome assembly is accompanied by phosphorylation of histone H3 at serine 10 (de la Barre et al., 2000).

In this work, the role of the N-terminal tails of the different histone species was studied in chromosome condensation by using nucleosome-mediated competitive inhibition of chromosome assembly. Chromosomes were formed in Xenopus egg extracts in the presence of reconstituted chimeric nucleosomes containing different combinations of recombinant full-length and tailless histones. Evidence is presented here that the N-terminus of histone H2B is a main player in the process of chromosome formation. On the contrary, the tail of histone H3, whether intact or phosphorylated, did not interfere with chromosomal condensation.

Results

Inhibition of chromosome assembly by trypsin- and clostripain-digested nucleosomes

Incubation of demembranated sperm nuclei in extracts isolated from Xenopus eggs allowed the assembly of mitotic chromosomes (Lohka and Masui, 1983; Hirano and Mitchison, 1993). Recently, we have demonstrated that adding exogenous native nucleosomes to the assembly reaction resulted in the inhibition of chromosome formation (de la Barre et al., 2000). Importantly, tailless nucleosomes, prepared by trypsin digestion, failed to inhibit the formation of mitotic chromosomes. This suggests that the flexible histone tails are involved in the recruitment of the putative chromosome assembly factor(s) and consequently play an essential role in chromosome assembly (de la Barre et al., 2000). The main objective of this study was to determine which of the tails of the individual histones within the nucleosome is/are required for this inhibition process and, therefore, is/are important for the assembly itself.

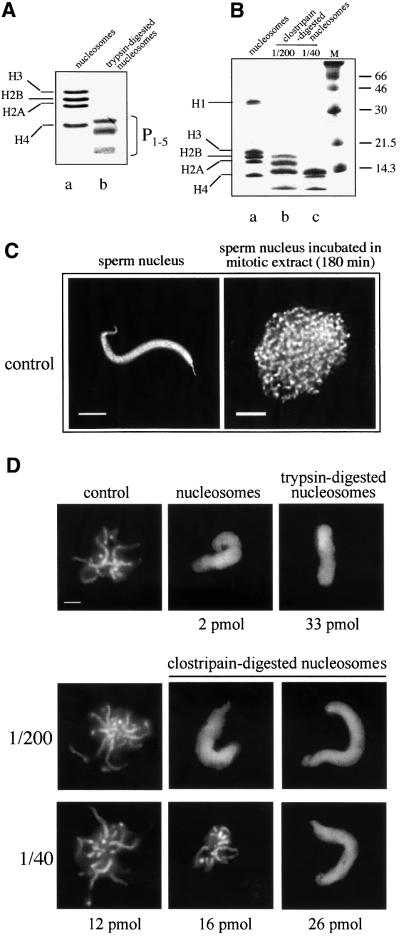

First, we produced ‘partially’ tailless nucleosomes by digestion of native particles with the protease clostripain (Figure 1). Indeed, it was reported that clostripain was able to cleave the N-termini of histones H3 and H4, leaving H2A and H2B essentially intact (Encontre and Parello, 1988). However, we have not been able to completely reproduce these data (Figure 1B, 1/200 and other results not shown). The full elimination of the tails of H3 and H4 was always accompanied by significant digestion of histone H2B (>60%) and some cleavage of H2A with probably the first three amino acids being removed from the N-terminus (Encontre and Parello, 1988; Banéres et al., 1997). Upon digestion with higher amounts of clostripain (enzyme/nucleosomes ratio of 1/40; Figure 1B), the histone tails were completely cleaved (Encontre and Parello, 1988; Banéres et al., 1997). Chromosome formation was inhibited in the presence of 16 pmol of ‘partially’ tailless nucleosomes (compare Figure 1C with Figure 1D, ratio 1/200) while 26 pmol of clostripain-prepared tailless nucleosomes were necessary to observe the same effect (Figure 1D, ratio 1/40). Inhibition of chromosome condensation by tailless nucleosomes prepared by trypsin digestion took place at 33 pmol (Figure 1D and de la Barre et al., 2000). We attributed the slight difference (1.25×) in the inhibitory efficiency of the two types of tailless nucleosomes, respectively obtained by cleavage with each of the two proteases to the fact that trypsin digestion of the histone octamer was less controlled (for details see Encontre and Parello, 1988).

Fig. 1. Effect of native as well as trypsin- and clostripain-digested nucleosomes on chromosome condensation. (A) An 18% SDS–PAGE of histones isolated from native (a) and trypsin-digested (b) nucleosomes. P1–5 designate the trypsin resistant peptides (mainly the histone fold domains, see van Holde, 1988). (B) As (A), but for histones isolated from clostripain-digested nucleosomes at histone: clostripain molar ratio 1:200 (b) and 1:40 (c). On (a) are shown the histones prepared from the control non-digested nucleosomes. (C) Controls. Demembranated sperm nuclei and chromosomes assembled after 180 min of incubation of sperm nuclei in Xenopus egg extract. (D) A high concentration of proteolized nucleosomes is required for inhibition of chromosome condensation. Demembranated sperm nuclei were incubated in the extract in the absence (control) or in the presence of native or trypsin- (upper part of the panel) or clostripain-digested nucleosomes (lower part of the panel) at the indicated amounts. Chromosome assembly was carried out for 180 min, the samples were fixed, stained with Hoechst 33258 and observed by fluorescence microscopy. Bars, 5 µm.

Two conclusions can be drawn from these results: (i) the inhibitory amounts of the two types of tailless nucleosomes are very close and are much higher than that of native nucleosomes (2 pmol, Figure 1D and de la Barre et al., 2000). Thus, regardless of how the tails were removed, the tailless nucleosomes have lost their capacity to inhibit chromosome condensation. These findings confirmed our previous data showing the important function of the histone tails in chromosome condensation (de la Barre et al., 2000). (ii) A removal of the histone N-termini, total for H3 and H4 and in high proportions of H2B, has led to the loss of the inhibiting effect, suggesting that the tail(s) of some of these histones (or the tails of all three) within the nucleosome is/are essential for chromosome assembly.

The N-termini of histones H2A and H2B interfere with chromosome condensation

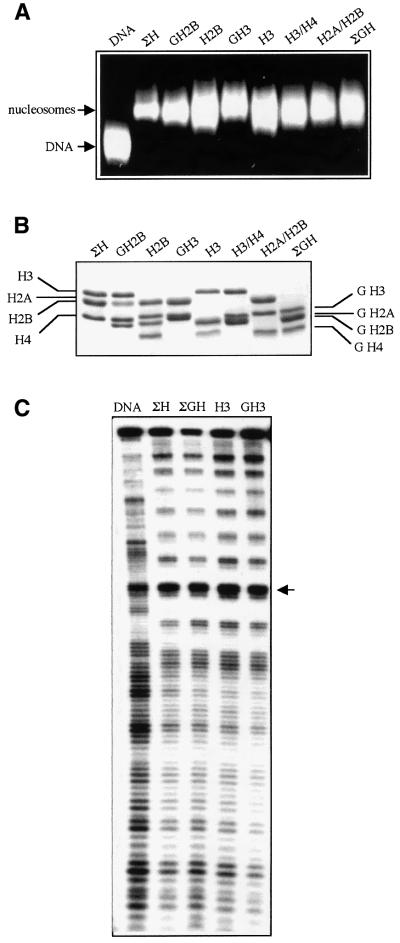

The above results, however, do not discriminate between these different possibilities. In addition, the degree of proteolysis of the histones is experimentally difficult to control, i.e. particles containing histones digested to different extents may be present in the nucleosome preparations. In order to overcome these difficulties, we have then reconstituted ‘chimeric’ nucleosomes by using bulk nucleosomal DNA and different combinations of well defined recombinant full-length and mutant histones (Figure 2). The recombinant proteins were expressed in bacteria and purified to homogeneity (Figure 2B). A trace amount of 32P-end-labeled 152 bp EcoRI–RsaI fragment comprising a Xenopus borealis somatic 5S RNA gene was added to the reconstitution reactions. In this way the efficiency of reconstitution and the structure of the reconstituted particles could be checked (Figure 2A and C). Under the conditions used, all added DNA had formed a complex with the histones: no free DNA was detected by electrophoretic mobility shift analysis (EMSA) (Figure 2A). The DNase I footprinting demonstrated a clear 10 bp nucleosomal repeat (Figure 2C), an evidence for well-structured particles. Therefore, the reconstituted nucleosomes showed an organization which was highly similar to the native ones, a result which was in agreement with the available data (Luger et al., 1999).

Fig. 2. Characterization of the reconstituted ‘chimeric’ nucleosomes. Nucleosomes were reconstituted by using bulk DNA isolated from mononucleosomes and different combinations of recombinant histones and their mutants. A tracer amount of 32P-end-labeled 152 bp EcoRI–RsaI fragment containing a Xenopus borealis 5S RNA gene was present in the reconstitution mixture; (ΣH): nucleosomes, reconstituted with intact histones; (ΣGH): particles containing only the globular domains of the four histones; (H2B), (H3): chimeric nucleosomes, containing either intact H2B, or H3 and the globular parts of the three remaining histones; (H3/H4) and (H2A/H2B): particles reconstituted either with intact H3 and H4 or H2A and H2B and the two other histones tailless; (GH3), (GH2B): reconstituted nucleosomes either with the histone fold domain of H3 or that of H2B and the three remaining histones intact. (A) EMSA of the reconstituted nucleosomes in 2% agarose gel. After completion of the electrophoresis the gel was stained with ethidium bromide. (B) SDS–PAGE (18%) of the recombinant histones, isolated from the reconstituted chimeric nucleosomes. (C) DNase I footprinting of the reconstituted samples. The arrow shows the dyad axis of the nucleosomes. For simplicity the biochemical and structural characterization of only some of the used chimeric nucleosomes are shown.

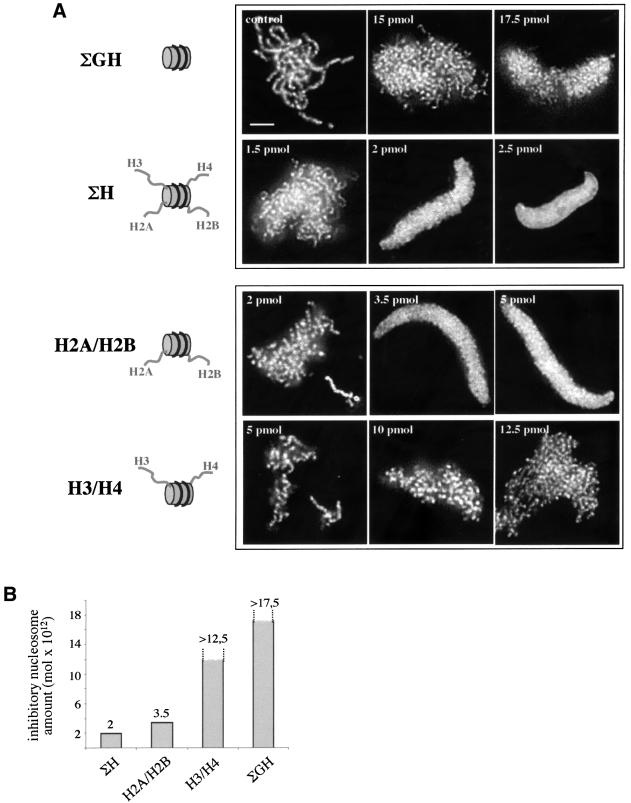

Further on, the reconstituted structures were used in chromosome assembly inhibition experiments. The nucleosomes reconstituted with tailless histones (ΣGH) did not affect chromosome condensation, whereas those assembled with full-length proteins (ΣH) completely inhibited the process (Figure 3). Importantly, the inhibition was observed at 2 pmol, an inhibitory amount equal to that of native nucleosomes. Thus, the reconstituted particles not only showed very close structure to the native ones, but they also behaved functionally like them. This validated the use of nucleosome particles reconstituted with several combinations of full-length and mutant histones to study their inhibition properties. Surprisingly, the particles (H2A/H2B) containing intact histones H2A and H2B and the globular domains GH3 and GH4 of H3 and H4 respectively, demonstrated a very strong inhibitory effect (Figure 3): 3.5 pmol only were sufficient to arrest the chromosome assembly process. Thus, the tails of H2A and H2B are likely to be major players in chromosome assembly.

Fig. 3. (A) The tails of histones H2A and H2B, but not those of H3 and H4 interfere with chromosome condensation. Chromosome assembly was performed as described in Figure 1 in the presence of the different chimeric nucleosomes. After fixation and staining with Hoechst 33258, the structures formed were observed by fluorescence microscopy. The amount of the competitor particles is shown on the left upper corner of each picture. The reconstituted particles are schematically drawn on the left side of the respective panels. The tails of the histones are presented in grey. For simplicity the tail of only one of the two homologous histones is shown. Bar, 5 µm. (B) Quantification of the data presented in (A).

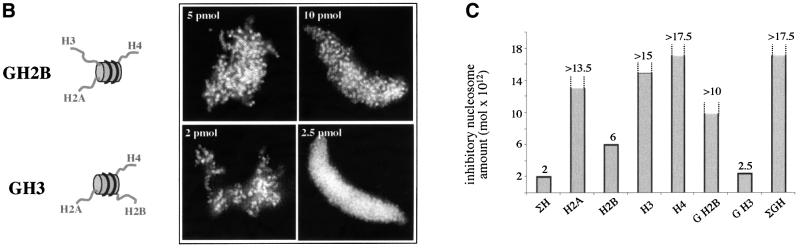

The N-terminus of histone H2B is a main player in chromosome condensation

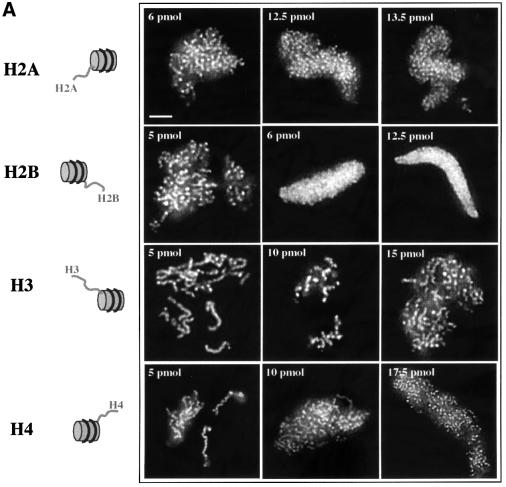

To understand whether the tails of both histones H2A and H2B, or the terminus of only one of these histones are essential for chromosome condensation, nucleosomes were prepared which contained either intact H2A (H2A particles) or intact H2B (H2B particles), the other three histones being tailless. Under these conditions, only the H2B particles were able to inhibit chromosome assembly (Figure 4A), demonstrating that the tail of histone H2B is essential for this process. This conclusion was further confirmed by the experiments with particles reconstituted with tailless H2B (GH2B) and the three other full-length histones (Figure 3B, GH2B particles). Indeed, these reconstitutes were unable to inhibit chromosome assembly.

Fig. 4. The tail of histone H2B is responsible for the nucleosome-induced inhibition of chromosome assembly. (A) The experiments were carried out as described in Figure 1, but in the presence of nucleosomes containing either full-length histone H2A, or H2B, or H3 or H4 and the globular domains of the three remaining histones. The assembled structures were visualized by fluorescence microscopy. (B) Same as (A), but in the presence of reconstituted nucleosomes comprising either the globular domain of histone H2B (GH2B) or that of histone H3 (GH3) and the three other full-length histones. (C) Quantification of the data presented in (A) and (B). For comparison the inhibition effect of (ΣH) and (ΣGH) reconstituted nucleosomes are also shown. Bar, 5 µm.

Interestingly, the H2B nucleosome inhibition was observed at 6 pmol, an amount about two times higher than that of the H2A/H2B particles (see Figure 3) suggesting that the presence of intact H2A terminus, although dispensable, increased the inhibitory properties of the chimeric particles.

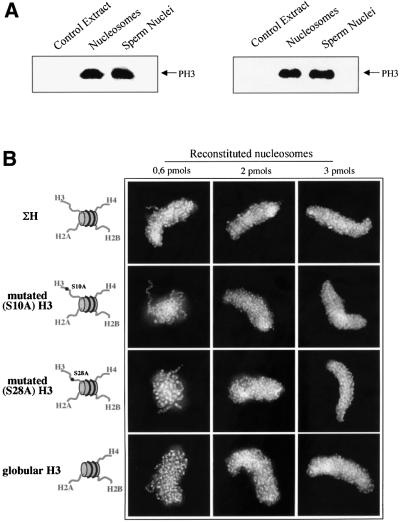

The tail of histone H3, whether intact or phosphorylated, is not essential for chromosome condensation

A widely held hypothesis claimed that the phosphorylation of histone H3 at serine 10 and hence the tail of histone H3 are required for chromosome condensation during mitosis (for recent reviews see Cheung et al., 2000; Hans and Dimitrov, 2001). However, this hypothesis was essentially based on correlative evidence. Our experimental procedure is a unique approach allowing the direct study of a causal relationship between these two events. We have found that chromosome formation was not inhibited by chimeric nucleosomes containing intact H3 and/or intact H4 and the other tailless histones (Figures 3 and 4), which strongly suggested that the tails of these proteins were not important for chromosome assembly. This was further confirmed by the properties of the GH3 and GH4 particles (comprising the globular domain of H3 or of H4 and the three other full-length histones, Figure 4B and C): the lack of the N-terminus of H3 or of H4 had no effect on the inhibitory ability of these reconstituted nucleosomes. Besides, the degree of phosphorylation of histone H3 of the exogenous nucleosomes added to the extract was essentially the same as that of the endogenous nucleosomes of the remodeled sperm nuclei (Figure 5A). Thus, the presence of nucleosomes with a phosphorylated H3 tail exhibited the same inhibition capacity as nucleosome samples devoid of a H3 tail, demonstrating that the tail of histone H3, whether intact or phosphorylated, does not play an important role in chromosome condensation. This was further confirmed by experiments with particles containing the four histones full length but with H3 mutated either at serine 10 or at serine 28 (the two sites of phosphorylation of H3 during cell division): the inhibition with both ΣH(S10A) and ΣH(S28A) reconstitutes was observed with the same amount (2 pmol) as that of phosphorylated native nucleosomes (Figure 5).

Fig. 5. The mutation of the phosphorylable serines of histone H3 tail does not interfere with the nucleosome inhibition effect on chromosome assembly. (A) The degree of phosphorylation of exogenous nucleosomes is the same as that of the nucleosomes of the remodeled sperm nuclei. Identical amounts of bulk nucleosomes and sperm nuclei were added to equal volumes of extract and, after incubation for 30 min at 22°C, the samples were run on an 18% SDS–PAGE gel. The phosphorylation of histone H3 was visualized by western blotting. The results of two independent experiments are shown. (B) Effect on the mutation of the phosphorylable serines of histone H3 on the nucleosome inhibition efficiency. Chromosome assembly was carried out in the presence of nucleosomes reconstituted either with histone H3 mutated at serine 10, ΣH(S10A), or with H3 mutated at serine 28, ΣH(S28A), and the three remaining non-mutated full-length histones. The experiments as well as the visualization of the formed structures were as in Figure 3.

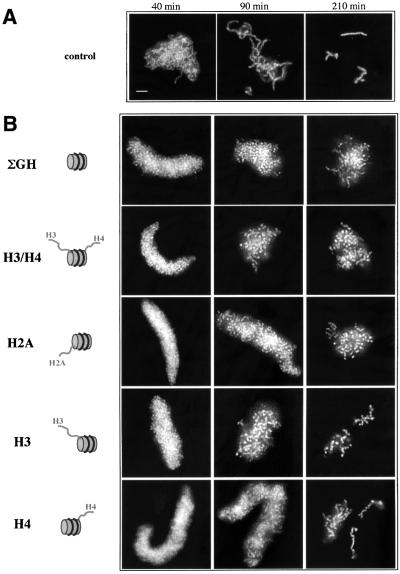

Effect of competitor nucleosomes on the kinetics of chromosome assembly

Above, we have demonstrated that some of the reconstituted nucleosomes did not affect the final compact state of mitotic chromosomes. Nonetheless, a possibility exists that these particles could be able to interfere with the time course of chromosome assembly. To check this hypothesis, the kinetics of chromosome condensation in the presence of such different reconstitutes was followed. As seen in Figure 6, all reconstitutes were able to slightly delay the time course of chromosome formation. It should be pointed out that even the tailless nucleosomes were able to induce the same delay in the kinetics of chromosome condensation.

Fig. 6. Chromosome assembly kinetics is delayed in the presence of competitor nucleosomes. Chomosome assembly was carried out under standard conditions (Figure 3) in the absence (A) or the presence (B) of different types of reconstituted nucleosomes. At the times indicated an aliquot of the reaction was removed, fixed and stained with Hoechst 33258. Bar, 5 µm.

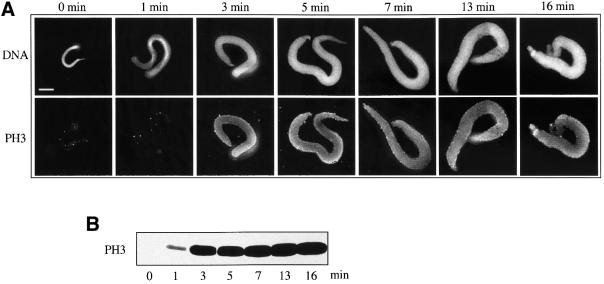

Phosphorylation of histone H3 correlates with the initial stages of sperm nucleus decondensation in Xenopus egg extracts

We have recently shown that the assembly of chromosomes in the Xenopus extract is accompanied by phosphorylation of histone H3 at serine 10 (de la Barre et al., 2000). However, it is not known whether this histone H3 modification correlates with chromosome condensation in the extract. To address this question the kinetics of chromosome assembly was followed and histone H3 phosphorylation was visualized by both immunofluorescence and western blotting (Figure 7). The decondensation of sperm nuclei was accompanied by histone H3 phosphorylation. Importantly, upon completion of the decondensation (at ∼10 min after the initial incubation), a saturation of the histone H3 phosphorylation was recorded (Figure 7B). Therefore, in contrast to cells in culture, a straightforward correlation between sperm decondensation and phosphorylation of histone H3 at serine 10 is observed.

Fig. 7. Decondensation of sperm nuclei in Xenopus egg extract is accompanied by phosphorylation of histone H3 at serine 10. (A) Chromosomes were assembled under standard conditions in mitotic egg extract and aliquots were removed and fixed at the times indicated. Chromosomal DNA was stained with Hoechst 33258. Phosphorylation of histone H3 was visualized by indirect immunofluorescence using an antibody against phosphorylated histone H3 at serine 10. Bar, 5 µm. (B) Immunoblotting analysis of the kinetics of histone H3 phosphorylation during chromosome assembly. Sperm nuclei were incubated in the extract for the times indicated and the chromosome intermediates were pelleted by centrifugation on a bench-top centrifuge. The proteins from the pellet were separated on a 15% SDS–PAGE gel and after transfer the phosphorylated histone H3 was detected using anti-phosphorylated histone H3 antibody.

Discussion

Chromosome assembly in Xenopus egg extracts was used to assess the role of each individual N-terminal histone tail in chromosome condensation. Initially, tailless nucleosome particles were prepared by digestion of native nucleosomes either with trypsin or with clostripain. Both types of tailless nucleosomes lost their ability to inhibit chromosome assembly, confirming that the N-histone termini play an essential role in chromosome condensation (de la Barre et al., 2000).

Effect of the individual histone tails on chromosome assembly

This question was addressed by using chimeric nucleosomes reconstituted with full-length and tailless histones in different combinations. The (H2B) particle, containing intact H2B and the three other tailless histones, was the only one able to inhibit chromosome condensation, identifying the N-terminus of this histone as a main player in this process. This was further confirmed by an experiment with the G2B nucleosome (reconstituted with the globular domain of H2B and the remaining histones intact), which was unable to interfere with chromosome assembly. Interestingly, the inhibition with H2B reconstitute was observed at 6 pmol, an amount three times higher than the inhibitory amount of native or reconstituted with intact histone ΣH particles. Furthermore, (H2A/H2B) chimeric nucleosomes containing full-length H2A and H2B were found to inhibit chromosome formation at 3.5 pmol. Since the H2A N-terminus alone did not have the ability to interfere with chromosome assembly, these data showed that its presence in the nucleosome containing intact H2B increased the inhibitory capacity of the particle. The nucleosomes GH3 (intact H2A, H2B and H4, and tailless H3) impeded chromosome condensation at 2.5 pmol, i.e. almost as efficiently as the ΣH structures, further demonstrating that histone H4 can also contribute to the inhibitory properties of the particles.

How does the tail of histone H2B fulfill its inhibitory function in these competition assays? Our previous work showed that the exogenous nucleosomes added to the extract recruited some unknown chromosome assembly factors, which were different from the condensin complexes or topoisomerase II (de la Barre et al., 2000). Since the tailless nucleosomes have lost this property, it was concluded that the histone N-termini were responsible for the recruitment of these factors (de la Barre et al., 2000). In the light of the data presented here, one could assume that the tail of histone H2B is a main target for (an) essential and yet unknown chromosomal assembly factor(s).

The effect of histone H3 tail and its phosphorylation on chromosome condensation

During both mitosis and meiosis, chromosome assembly is accompanied by phosphorylation of histone H3 at serine 10 (reviewed in Hans and Dimitrov, 2001). It was claimed that histone H3 phosphorylation is required for chromosome condensation (Hendzel et al., 1997; Van Hooser et al., 1998; Wei et al., 1998, 1999; Hsu et al., 2000). Indeed, in some organisms and cells in culture, chromosome condensation was shown to be accompanied by this histone H3 modification (for recent reviews see Cheung et al., 2000; Hans and Dimitrov, 2001). In addition, depletion of the histone H3 mitotic kinase aurora B in Drosophila (Giet and Glover, 2001) and in Caenorhabditis elegans (Speliotes et al., 2000) resulted in only partial chromosome condensation at mitosis as well as in reduced levels of H3 phosphorylation. This evidence, however, was essentially correlative. Another set of such correlative data suggested that histone H3 phosphorylation was not related to chromosome condensation. For example, during cell division no relationship between chromosome condensation and histone H3 phosphorylation was observed in plants (Kaszas and Cande, 2000). Instead, a correlation between H3 phosphorylation and the maintenance of sister chromatid cohesion was reported (Kaszas and Cande, 2000). In mice meiotic spermatocytes, the initial strong chromosome compaction did not correlate with H3 phosphorylation (Cobb et al., 1999). All the above-described data demonstrate that the role of histone H3 phosphorylation during cell division is still controversial.

We have directly addressed this question by using competition experiments in the Xenopus system for in vitro assembly of mitotic chromosomes. The presence in the Xenopus egg extract of chimeric nucleosomes (H3) containing intact H3 and the other tailless histones did not affect chromosome condensation, suggesting that the tail of H3 played, if any, a minor role in this process. This was further confirmed by the experiments with GH3 particles made of three intact histones and the globular domain of H3: these particles were as efficient as the native ones in inhibiting of chromosome assembly. Besides, the extract kinase activities heavily phosphorylated the tail of histone H3 when the competitor bulk nucleosomes were added to the extracts. Hence, the competitor phosphorylated nucleosomes exhibited identical inhibition efficiency as did the histone H3 tailless nucleosomes. One can, therefore, conclude that neither histone H3 tail nor its phosphorylation is important for chromosome condensation. In addition, the presence of histone H3 mutated at serine 10, and thus, non-phosphorylable, had no effect on the inhibitory properties of the competitor nucleosomes, further confirming the above conclusion.

This finding is in agreement with the genetics data in yeast where it was shown that a strain containing a single mutation within histone H3 at serine 10 exhibited generation times and cell-cycle progression indistinguishable from these of the wild-type strain (Hsu et al., 2000). However, our results do not fit with the conclusions from other sets of genetics data in Tetrahymena thermophila (Wei et al., 1999). A Tetrahymena strain S10A, with a mutant H3 gene at serine 10 as the only H3 gene, was shown to display abnormal mitosis and meiosis (Wei et al., 1999). The absence of H3 phosphorylation in S10A cells was associated with a difficulty for these cells to go through anaphase, with major abnormalities of chromosome segregation. Because some of the S10A chromosomes seemed to be in a more extended form, it was suggested that the abnormal segregation could be preceded by defects in chromatin condensation. However, a recent report clearly demonstrated that the phospho-H3 deficient chromosomes in aurora-B depleted Drosophila exhibited dumpy morphology, but normal compaction (Adams et al., 2001). Since histone H3 phosphorylation is involved not only in cell division but also in transcription (reviewed in Cheung et al., 2000; Strahl and Allis, 2000), it is possible that the somewhat lower degree of condensation and different shape of chromosomes in S10A cells could reflect the outcome of other processes involving H3 phosphorylation and taking place before cell division, rather than the direct effect of this H3 modification on chromosome compaction.

It should be noted that all reconstituted nucleosome particles studied here, which were not able to inhibit chromosome condensation, had the capacity to slightly delay the time course of chromosome formation. This slight decrease in the kinetics of chromosome condensation was even observed with tailless nucleosomes. Such a delay in the time course of chromosome formation was also seen in the presence of naked DNA (de la Barre et al., 2000). Therefore, this weak effect is not related to the histone tails, but rather reflects a temporary perturbation of the chromosome assembly properties of the Xenopus egg extract due to the presence of DNA or protein–DNA complexes. The above effect may reflect a non-specific and transient association of some chromosome assembly factors with the H2B tailless nucleosomes or with DNA.

In the past we have reported that, when used as competitors, the glutathione S-transferase (GST) fusions of the N-termini of core histones were able to inhibit chromosome condensation in Xenopus egg extracts (de la Barre et al., 2000). The GST–H3 tail fusion was found to be twice as efficient as the other fusions. Nonetheless, the inhibitory amount of the fusions was in the range of hundreds of picomols (de la Barre et al., 2000). Importantly, a micromolar amount of the chemically synthesized peptide containing the first 20 amino acids of the N-terminus of histone H3 was necessary to arrest chromosome condensation (A.-E.de la Barre and S.Dimitrov, unpublished results). Thus, the inhibition of chromosome condensation requires amounts of histone tails free in solution several orders of magnitude higher than the tails within nucleosomes. Hence, the individual histone tails within the nucleosomes (the natural substrates for factors involved in chromosome assembly) behaved differently than the free ones. They were not only much better inhibitors but also showed distinct specificity in arresting chromosome formation. In this context, it should be stressed that our previous results on histone H3 tail reflected the inhibition of the mitotic histone H3 kinase(s), and not the effect of H3 phosphorylation by itself on chromosome condensation (de la Barre et al., 2000).

The role of histone H3 phosphorylation during cell division: the ‘ready production label’ model

Why is histone H3 specifically phosphorylated at serine 10 during cell division? No definite answer to this question can be given to date. Our results clearly demonstrate the lack of causal relationship between H3 phosphorylation and chromosome condensation.

Histone H3 phosphorylation is highly ordered in the different organisms studied, shows a distinct pattern and takes place at different phases in both mitosis and meiosis (summarized in Hans and Dimitrov, 2001). As discussed earlier, during mitosis in vertebrate cells in culture this H3 modification accompanied chromatin condensation: it is first detected in G2 on pericentromeric chromatin and then spreads further along the chromosome arms (Hendzel et al., 1997; Van Hooser et al., 1998; Sauve et al., 1999). By contrast, in plants, H3 phosphorylation first occurred at late prophase on already quite compact chromosomes and is restricted to pericentromeric chromatin only (Kaszas and Cande, 2000). However, all the experimental systems described exhibited a common feature: chromosomes were heavily phosphorylated at metaphase and dephosphorylated upon exit of cell division (reviewed in Hans and Dimitrov, 2001). Thus, the cell might use the phosphorylation of H3 to mark the chromosomes when they are ready to progress through anaphase and telophase, i.e. histone H3 phosphorylation could be viewed as some type of ‘ready production label’. This label would have to be ‘attached ‘ to histone H3 once the chromosomes had passed through the various checkpoints and have reached metaphase. It could be used by the cell in processes subsequent to metaphase. In agreement with this, the available data showed that the main defects associated with H3 phosphorylation deficiency occurred after metaphase (Hans and Dimitrov, 2001).

According to the ‘ready production label’ hypothesis, if the chromosomes have reached metaphase they would have to be phosphorylated independently from their state of compaction. Thus, even partially condensed chromosomes should be highly phosphorylated at metaphase. One such example is reported for mammalian chromosomes (Van Hooser et al., 1998). When metaphase mammalian chromosomes were incubated in a hypotonic solution, they strongly decondensed and were dephosphorylated. Upon release in the culture medium, although the chromosomes did not recondense they became again heavily phosphorylated and were able to enter anaphase (Van Hooser et al., 1998).

The kinetics of histone H3 phosphorylation during in vitro chromosome assembly described in this study could be viewed as a second example. Histone H3 within the sperm nuclei was not phosphorylated. Incubation of the sperm nuclei into the Xenopus egg extract resulted in a massive phosphorylation of H3 at serine 10. Importantly, the time course of phosphorylation strictly paralleled sperm nucleus decondensation. This phenomenon is apparently in contradiction with the currently accepted hypothesis that H3 phosphorylation is required for chromosome condensation. How could this observation be explained? The following explanation is suggested. The egg extract is arrested at metaphase where the mitotic H3 kinases are very active (Murnion et al., 2001; Scrittori et al., 2001) and, according to the ‘ready production label’ model, any chromosomal substrate has to be phosphorylated. However, the sperm nuclei are highly condensed and histone H3 is not accessible to the enzymes. During nucleus decondensation in the extract histone H3 becomes accessible and thus, phosphorylated with kinetic identical to that of the decondensation process.

In conclusion, we have used the advantages of extracts isolated from Xenopus eggs to study the function of individual histone N-termini in chromosome condensation. The experiments with competitor chimeric nucleosomes have shown that neither histone H3 tail, nor its phosphorylation was important for this process. A novel hypothesis termed the ‘ready production label’ model, explaining the role of histone H3 phosphorylation during cell division was proposed. In addition, an essential role for histone H2B N-terminus in chromosome condensation was demonstrated. It is suggested that the H2B tail could recruit an unknown chromosome assembly factor(s). The identification of this factor(s) remains a challenge for future studies.

Materials and methods

Mitotic extract preparation

Mitotic extracts from Xenopus eggs were prepared essentially by using the protocol of Losada et al. (2000). After dejellying, the eggs were resuspended in XBE2 buffer (100 mM KCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM CaCl2, 10 mM K–HEPES pH 7.7, 5 mM K–EGTA, 0.05 M sucrose) supplemented with 10 µg/ml leupeptin and apoprotin and 100 µg/ml cytochalasin D and crushed at 16°C by centrifugation for 20 min at 15 000 r.p.m. in an SW41 rotor (Beckman Instruments). The cytoplasmic fraction was collected and kept on ice. Following the addition of leupeptin, apoprotin and cytochalasin D at a final concentration of 10 µg/ml and 1/20 volume of 20 × energy mix (20 mM phosphocreatine, 2 mM ATP, 5 µg/ml creatine kinase, final concentration) the extract was recentrifugated at the same speed as above, but at 4°C. The clarified golden layer was spinned at 52 000 r.p.m. for 2 h at 4°C in a TLS-55 rotor (Beckman Instruments). After removing the top lipid fraction by aspiration under vacuum, the cytoplasmic fraction was centrifuged under the same conditions, but for 30 min only. The supernatant was carefully collected, aliquoted in 20 µl fractions and frozen immediately in liquid nitrogen. The aliquots were stored at –80°C until use.

Isolation of demembranated sperm nuclei

Demembranated sperm nuclei were isolated essentially as described (de la Barre et al., 1999). The demembranated sperm nucleus suspension was brought to about 1 µg/µl DNA, aliquoted in 5 µl fractions and stored at –80°C.

Preparation of native nucleosomes and proteinase digestion

The protocol of Mirzabekov et al. (1990) was used for the isolation of hen erythrocyte nuclei. To prepare nucleosomes, the nuclei were resuspended in 10 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.8, 80 mM NaCl, 2 mM CaCl2, 0.1 mM phenyl methylsulfonyl fluoride and digested for 40–45 min at 37°C with microccocal nuclease (5 U of nuclease/50 µg DNA). The digestion was stopped with 5 mM EDTA pH 8.0 and the solution dialyzed overnight at 4°C against 50 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0, 5 mM EDTA, 0.65 M NaCl. After bench top centrifugation, the supernatant was loaded on 5–25% sucrose gradient, containing 0.65 M NaCl and centrifuged for 20 h at 4°C in an SW41 rotor (Beckman Instruments) at 35 000 r.p.m.. The gradients were fractionated and the linker histone depleted nucleosome fraction dialyzed against the appropriate buffer. The nucleosomes were treated with trypsin as described (Speliotes et al., 2000). Diisopropylfluorophosphate (Sigma) was used to stop the reaction.

Clostripain digestion was carried out as follows. Linker depleted nucleosomes (200 µg) were cleaved with 1 µg (1/200 ratio) or 5 µg (ratio (1/40) clostripain (endoproteinase Arg-C; Boehringer) in a digestion buffer (90 mM Tris–HCl, 8.5 mM CaCl2, 5 mM dithiothreitol, 0.5 mM EDTA pH 7.6) for 1–3 h at 37°C. The reaction was stopped by adding N-α-p-tosyl-lysine chloromethylketone (TLCK; Sigma) at a final concentration of 10 mM. The cleaved histones were visualized on an 18% SDS–PAGE gel.

Preparation of recombinant histones

The procedure of Luger et al. (1999) was used to express and purify full-length Xenopus laevis histones and their globular domains. A standard site-directed mutagenesis was performed to create histone H3 mutated to alanine at serine 10 or at serine 28. The mutation at serine 10 was achieved by using the QuickChangeTM mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) and the oligonucleotides pet3aH3S10A (cagaccgcccgtaaagctacc ggagggaagg) and pet3bH3S10A (ccttccctccggtagcttt acgggcggtctg), while that at serine 28 was performed with pet3aH3S28A (caccaaggcagccaggaaggctgctcctgcta cc) and pet3bH3S28A (ggtagcaggagcagccttcctggctg ccttggtg) oligonucleotides. The expression and purification of the mutant proteins were carried out as for the intact ones. The recombinant histones were dialyzed against 10 mM HCl and stored at –20°C.

Reconstitution of ‘chimeric’ nucleosomes

The nucleosomes were reconstituted by using ‘bulk’ nucleosomal DNA and recombinant histones. The DNA was prepared from isolated hen erythrocyte nucleosomes. Briefly, a stochiometric amount of recombinant histones in a solution of 10 mM HCl was mixed and dialyzed overnight at 4°C against 2 M NaCl, 50 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.8, 1 mM EDTA (this long dialysis allowed the formation of proper histone octamers). Next morning, the dialysis tubing was opened and a bulk nucleosomal DNA, containing a trace amount of a 32P-end-labeled 152 bp EcoRI–RsaI fragment comprising the Xenopus borealis somatic 5S RNA gene, was added to it. The ratio of the recombinant octamers to the DNA was 1:0.8. The reconstitution was carried out by decreasing the concentration of the NaCl (Mutskov et al., 1998). The integrity and the structure of the reconstituted particles were checked by EMSA and DNase I footprinting.

EMSA and DNase I footprinting

Two percent non-ethidium bromide-containing agarose gels were used for EMSA. The electrophoresis was carried out at room temperature in 0.5× TBE (Tris–Borate–EDTA) buffer. Once the electrophoresis completed, the gels were stained with ethidium bromide and after destaining observed under UV light.

The DNase I footprinting of the reconstituted nucleosomes was performed for two min at room temperature with 10 ng of DNase I per 10 µl of nucleosome solution in 10 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.6, 5 mM MgCl2. The reaction was arrested with stop solution (10 mM EDTA, 0.1% SDS, 50 ng/µl proteinase K) and the samples further incubated for 30 min at 37°C. After phenol extraction and ethanol precipitation, the digested DNA was run on an 8% polyacrylamide sequencing gel containing urea. The gel was dried and exposed on a PhosphorImager screen.

Assembly of mitotic chromosomes in the Xenopus egg extract

A standard protocol (de la Barre et al., 1999) was used for chromosome assembly in the Xenopus egg extract. Demembranated sperm nuclei (105–2 × 105) were incubated at 22–24°C in 20–30 µl of extract. In some cases the extract was supplemented with cyclin BΔ90 (the non-degradable form of cyclin B). For the nucleosome-induced inhibition of chromosome assembly, a selected amount of native or reconstituted particles (expressed as picomols of nucleosomes per miroliter of extract) were added to the extract followed by the addition of the sperm nuclei. To observe the chromosome intermediates, aliquots from the reaction mixture were taken at selected times since the beginning of the assembly and fixed with fix/stain solution (Hoechst 33258 at 1 µg/ml in 200 mM sucrose, 10 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 7.4% formaldehyde, 0.23% DABCO, 0.02% NaN3, 70% glycerol). Chromosome formation was followed by conventional fluorescence microscopy.

Immunoblotting and immunofluorescence

The immunoblotting was carried out according to the protocol described in Mutskov et al. (1998). The serum against phosphorylated H3 was diluted 1:3000. The enhanced chemiluminescence system (ECLl Amersham) was used for the development of the reaction.

For immunofluorescence studies, a dilution of 1:5000 of the anti-phosphorylated histone H3 antiserum was made. A standard procedure (de la Barre et al., 2000) allowed the visualization of the kinetics of histone H3 phosphorylation during chromosome assembly.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Dr T.Richmond for the histone expression vectors and to Dr K.Nightingale for advice for recombinant histone purification. We thank Drs S.Rousseaux, I.Pashev, S.Nonchev and S.Khochbin for helpful discussion and critical input and M.Charra for technical assistance. We appreciate the support of Dr Jean-Jacques Lawrence throughout the course of this work. This study was supported by INSERM, La Ligue Nationale contre le Cancer and l’Association pour la Recherche sur le Cancer (ARC).

References

- Adams R.R., Maiato,H., Earnshaw,W.C. and Carmena,M. (2001) Essential role of Drosophila inner centromere protein (INCENP) and aurora B in histone H3 phosphorylation, metaphase chromosome alignment, kinetochore disjunction and chromosome segregation. J. Cell Biol., 153, 865–879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arents G., Burlingame,R.W., Wang,B.C., Love,W.E. and Moudrianakis, E.N. (1991) The nucleosomal core histone octamer at 3.1 Å resolution: a tripartite protein assembly and a left-handed superhelix. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 88, 10148–10152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banéres J.-L., Martin,E. and Parello,J. (1997) The N tails of histones H3 and H4 adopt a highly structured conformation in the nucleosome. J. Mol. Biol., 273, 503–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barra J.L., Rhounim,L., Rossignol,J.L. and Faugeron,G. (2000) Histone H1 is dispensable for methylation-associated gene silencing in Ascobolus immersus and essential for long life span. Mol. Cell. Biol., 20, 61–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradbury E.M. (1992) Reversible histone modifications and the chromosome cell cycle. BioEssays, 14, 9–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradbury E.M., Inglis,R.J., Matthews,H.R. and Sarner,N. (1973) Phosphorylation of very-lysine-rich histone in Physarum polycephalum. Correlation with chromosome condensation. Eur. J. Biochem., 33, 131–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung P., Allis,C.D. and Sassone-Corsi,P. (2000) Signaling to chromatin through histone modifications. Cell, 103, 263–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobb J., Miyaike,M., Kikuchi,A. and Handel,M.A. (1999) Meiotic events at the centromeric heterochromatin: histone H3 phosphorylation, topoisomerase IIa localization and chromosome condensation. Chromosoma, 108, 412–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dasso M., Dimitrov,S. and Wolffe,A.P. (1994) Nuclear assembly is independent of linker histones. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 91, 12477–12481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Barre A.-E., Robert-Nicoud,M. and Dimitrov,S. (1999) Assembly of mitotic chromosomes in Xenopus egg extract. Methods Mol. Biol., 119, 219–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Barre A.E., Gerson,V., Gout,S., Creaven,M., Allis,C.D. and Dimitrov,S. (2000) Core histone N-termini play an essential role in mitotic chromosome condensation. EMBO J., 19, 379–391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimitrov S. and Wolffe,A.P. (1995) Chromatin and nuclear assembly: experimental approaches towards the reconstitution of transcriptionally active and silent states. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 1260, 1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimitrov S. and Wolffe,A.P. (1996) Remodeling somatic nuclei in Xenopus laevis egg extracts: molecular mechanisms for the selective release of histones H1 and H1° from chromatin and the acquisition of transcriptional competence. EMBO J., 15, 5897–5906. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimitrov S., Dasso,M.C. and Wolffe,A.P. (1994) Remodeling sperm chromatin in Xenopus laevis egg extracts: the role of core histone phosphorylation and linker histone B4 in chromatin assembly. J. Cell Biol., 126, 591–601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Encontre I. and Parello,J. (1988) A chromatin core particle obtained by selective cleavage of histones H3 and H4 by clostripain. J. Mol. Biol., 202, 673–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giet R. and Glover,D.M. (2001) Drosophila aurora B kinase is required for histone H3 phosphorylation and condensin recruitment during chromosome condensation and to organize the central spindle during cytokinesis. J. Cell Biol., 152, 669–681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hans F. and Dimitrov,S. (2001) Histone H3 phosphorylation and cell division. Oncogene, 20, 3021–3027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendzel M.J., Wei,Y., Mancini,M.A., Van Hooser,A., Ranalli,T., Brinkley,B.R., Bazett-Jones,D.P. and Allis,C.D. (1997) Mitosis-specific phosphorylation of histone H3 initiates primarily within pericentromeric heterochromatin during G2 and spreads in an ordered fashion coincident with mitotic chromosome condensation. Chromosoma, 106, 348–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirano T. (2000) Chromosome cohesion, condensation and separation. Annu. Rev. Biochem., 69, 115–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirano T. and Mitchison,T.J. (1993) Topoisomerase II does not play a scaffolding role in the organization of mitotic chromosomes assembled in Xenopus egg extracts. J. Cell Biol., 120, 601–612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirano T. and Mitchison,T.J. (1994) A heterodimeric coiled-coil protein required for mitotic chromosome condensation in vitro. Cell, 79, 449–458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirano T., Kobayashi,R. and Hirano,M. (1997) Condensins, chromosome condensation protein complexes containing XCAP-C, XCAP-E and a Xenopus homolog of the Drosophila Barren protein. Cell, 89, 511–521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houchmandzadeh B. and Dimitrov,S. (1999) Elasticity measurements show the existence of thin rigid cores inside mitotic chromosomes. J. Cell Biol., 145, 215–223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houchmandzadeh B., Marko,J.F., Chatenay,D. and Libchaber,A. (1997) Elasticity and structure of eukaryote chromosomes studied by micromanipulation and micropipette aspiration. J. Cell Biol., 139, 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu J.Y. et al. (2000) Mitotic phosphorylation of histone H3 is governed by Ipl1/aurora kinase and Glc7/PP1 phosphatase in budding yeast and nematodes. Cell, 102, 279–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaszas E. and Cande,W.Z. (2000) Phosphorylation of histone H3 is correlated with changes in the maintenance of sister chromatid cohesion during meiosis in maize, rather than the condensation of the chromatin. J. Cell Sci., 113, 3217–3226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohka M.J. and Masui,Y. (1983) Formation in vitro of sperm pronuclei and mitotic chromosomes induced by amphibian ooplasmic components. Science, 220, 719–721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Losada A., Yokochi,T., Kobayashi,R. and Hirano,T. (2000) Identification and characterization of SA/Scc3p subunits in the Xenopus and human cohesin complexes. J. Cell Biol., 150, 405–416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luger K., Mader,A.W., Richmond,R.K., Sargent,D.F. and Richmond,T.J. (1997) Crystal structure of the nucleosome core particle at 2.8 Å resolution. Nature, 389, 251–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luger K., Rechsteiner,T.J. and Richmond,T.J. (1999) Expression and purification of recombinant histones and nucleosome reconstitution. Methods Mol. Biol., 119, 1–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahadevan L.C., Willis,A.C. and Barratt,M.J. (1991) Rapid histone H3 phosphorylation in response to growth factors, phorbol esters, okadaic acid and protein synthesis inhibitors. Cell, 65, 775–783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirzabekov A.D., Pruss,D.V. and Ebralidze,K.K. (1990) Chromatin superstructure-dependent crosslinking with DNA of the histone H5 residues Thr1, Hist25 and His62. J. Mol. Biol., 211, 479–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murnion M.E., Adams,R.A., Callister,D.M., Allis,C.D., Earnshaw,W.C. and Swedlow,J.R. (2001) Chromatin-associated protein phosphatase 1 regulates aurora-B and histone H3 phosphorylation. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 26656–26665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mutskov V., Gerber,D., Angelov,D., Ausio,J., Workman,J. and Dimitrov,S. (1998) Persistent interactions of core histone tails with nucleosomal DNA following acetylation and transcription factor binding. Mol. Cell. Biol., 18, 6293–6304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohsumi K., Katagiri,C. and Kishimoto,T. (1993) Chromosome condensation in Xenopus mitotic extracts without histone H1. Science, 262, 2033–2035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philpott A., Leno,G.H. and Laskey,R.A. (1991) Sperm decondensation in Xenopus egg cytoplasm is mediated by nucleoplasmin. Cell, 65, 569–578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poirier M., Eroglu,S., Chatenay,D. and Marko,J.F. (2000) Reversible and irreversible unfolding of mitotic newt chromosomes by applied force. Mol. Biol. Cell, 11, 269–276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saitoh N., Goldberg,I., Wood,E.R. and Earnshaw,W.C. (1994) ScII: an abundant chromosome scaffold protein is a member of a family of putative ATPases with an unusual predicted tertiary structure. J. Cell Biol., 127, 303–318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauve D.M., Anderson,H.J., Ray,J.M., James,W.M. and Roberge,M. (1999) Phosphorylation-induced rearrangement of the histone H3 NH2-terminal domain during mitotic chromosome condensation. J. Cell Biol., 145, 225–235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scrittori L., Hans,F., Angelov,D., Charra,M., Prigent,C. and Dimitrov,S. (2001) pEg2 aurora-A kinase, histone H3 phosphorylation and chromosome assembly in Xenopus egg extract. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 30002–30010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen X. and Gorovsky,M.A. (1996) Linker histone H1 regulates specific gene expression but not global transcription in vivo. Cell, 86, 475–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen X., Yu,L., Weir,J.W. and Gorovsky,M.A. (1995) Linker histones are not essential and affect chromatin condensation in vivo. Cell, 82, 47–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speliotes E.K., Uren,A., Vaux,D. and Horvitz,H.R. (2000) The survivin-like C.elegans BIR-1 protein acts with the Aurora-like kinase AIR-2 to affect chromosomes and the spindle midzone. Mol. Cell, 6, 211–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strahl B.D. and Allis,C.D. (2000) The language of covalent histone modifications. Nature, 403, 41–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutani T., Yuasa,T., Tomonaga,T., Dohmae,N., Takio,K. and Yanagida,M. (1999) Fission yeast condensin complex: essential roles of non-SMC subunits for condensation and Cdc2 phosphorylation of Cut3/SMC4. Genes Dev., 13, 2271–2283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomson S., Clayton,A.L., Hazzalin,C.A., Rose,S., Barratt,M.J. and Mahadevan,L.C. (1999a) The nucleosomal response associated with immediate-early gene induction is mediated via alternative MAP kinase cascades: MSK1 as a potential histone H3/HMG-14 kinase. EMBO J., 18, 4779–4793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomson S., Mahadevan,L.C. and Clayton,A.L. (1999b) MAP kinase-mediated signalling to nucleosomes and immediate-early gene induction. Semin.Cell Dev. Biol., 10, 205–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner B.M. (2000) Histone acetylation and an epigenetic code. BioEssays, 22, 836–845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Holde K. (1988) Chromatin. Springer-Verlag KG, Berlin, Germany.

- Van Hooser A., Goodrich,D.W., Allis,C.D., Brinkley,B.R. and Mancini,M.A. (1998) Histone H3 phosphorylation is required for the initiation, but not maintenance, of mammalian chromosome condensation. J. Cell Sci., 111, 3497–3506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei Y., Mizzen,C.A., Cook,R.G., Gorovsky,M.A. and Allis,C.D. (1998) Phosphorylation of histone H3 at serine 10 is correlated with chromosome condensation during mitosis and meiosis in Tetrahymena. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 95, 7480–7484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei Y., Yu,L., Bowen,J., Gorovsky,M.A. and Allis,C.D. (1999) Phosphorylation of histone H3 is required for proper chromosome condensation and segregation. Cell, 97, 99–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolffe A.P. and Hayes,J.J. (1999) Chromatin disruption and modification. Nucleic Acids Res., 27, 711–720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]