Abstract

Background

Harm reduction is a public health approach that emphasizes strategies to reduce the negative consequences of drug use. Rising overdose deaths in the United States have prompted integration of harm reduction strategies within criminal-legal systems (CLS), which have historically emphasized deterrence. However, the scope and nature of these strategies across the CLS remain poorly understood.

Methods

We conducted a scoping review, in accordance with PRISMA guidelines, to identify harm reduction strategies targeting illicit drug use that have been implemented within CLS settings in the United States. We searched seven databases for peer-reviewed articles published in the last 10 years. Eligible articles reported on implementation of a harm reduction strategy focused on reaching PWUD in a CLS setting. Using the Sequential Intercept Model as a guiding framework, we mapped strategies to law enforcement, initial detention/court hearings, jails and courts, reentry, and community corrections settings. We used DistillerSR to screen articles and abstract data.

Results

From 455 records, 99 articles met inclusion criteria, representing 51 discrete instances of harm reduction strategy implementation. Implementation was most common in custody settings (e.g., jails and courts) and frequently included initiation of medication for opioid use disorder, naloxone distribution, and CLS referral/diversion. Fewer instances of implementation were documented in early stage or community-based settings. CLS staff were directly involved in delivering over 75% of the harm reduction strategies, and one-third included partnerships with non-CLS government agencies. Nearly one-third of the strategies were implemented as part of research studies.

Conclusions

Harm reduction strategies have increasingly been integrated into CLS, though unevenly and often with a narrow clinical focus. Expanding harm reduction within CLS will require broader definitions, system-level buy-in, and efforts to align practice with public health evidence.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s40352-025-00369-x.

Keywords: Harm reduction, Implementation, Illicit drug use, Criminal-legal system, Evidence-based

Background

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services currently defines harm reduction as a practical and transformative approach that incorporates community-driven public health strategies—including prevention, risk reduction, and health promotion—to empower people who use drugs (PWUD) and their families with the choice to live healthy, self-directed, and purpose-filled lives (Knopf 2021; 2023). This approach centers PWUD, especially those in underserved communities, in these strategies and the practices that flow from them. For example, syringe services programs are rooted in harm reduction and have a strong evidence-base for reducing transmission of infectious diseases among people who inject drugs (Adams 2020; Fernandes et al. 2017; Foreman-Mackey et al. 2022; Jakubowski et al. 2023). Beyond this institutional lens, harm reduction is carried out across grassroots movements emphasizing autonomy, dignity, and social justice (Marlatt 1996). As a broader public health practice, encompassing both clinical and community-led response, harm reduction identifies pragmatic strategies that acknowledge the inevitability of risk-taking behaviors and seek to minimize negative consequences rather than demand abstinence.

In light of the ongoing North American overdose epidemic, which has resulted in more than 1.5 million deaths over the past two decades, harm reduction strategies have emerged as evidence-based overdose prevention practices in the United States (Ciccarone et al. 2019; Monnat 2022; Woolf and Schoomaker 2019). Common strategies in the United States include community-based distribution of naloxone to reverse opioid overdose and paper test strips or other technologies to detect specific drugs (like fentanyl or xylazine). Harm reduction practices are intended to prioritize autonomy and dignity, meet individuals where they are at (even when they are not ready to alter behaviors), and offer noncoercive support, recognizing any positive change as progress (Bhai et al. 2025; Doe-Simkins and Wheeler 2025; Krieger et al. 2018; Moustaqim-Barrette et al. 2021).

Criminal justice practices are often cast as diametrically opposed to harm reduction. For example, criminal-legal systems (CLS) in the United States (e.g., policing, prosecution, courts, and corrections) have historically viewed drugs and drug use as a threat to public safety and rely largely on punishment, deterrence, and surveillance (2012). In spite of this established framing, there have been attempts to integrate harm reduction strategies into CLS in an effort to prevent overdose deaths (Brinkley-Rubinstein et al. 2017, 2018; Rouhani et al. 2024; Inciardi 1996; Johnson et al. 2025; 2024). Thus, just as criminal-legal agencies are enacting policies criminalizing drug use (e.g., paraphernalia laws) (Guilamo-Ramos et al. 2025), further stigmatizing PWUD and increasing risks and barriers to social services and health care, they are also providing them with lifesaving naloxone due to an acceptance that individuals are at risk of continuing or resuming use of illicit drugs (Balter and Howell 2024; Showalter et al. 2021; Wenger et al. 2019; Victor et al. 2024).

Historically, CLS have been significantly constrained in delivering harm reduction services (Carroll et al. 2022; Des Jarlais 2017; Heller et al. 2004), despite serving a population at high risk for overdose. Harm reduction strategies have often originated and been implemented in unsanctioned environments, and it is unclear the extent to which they are available and accessible within CLS. For example, the extant research has documented instances of equipping police with naloxone (Ray et al. 2023; Davis et al. 2014)and providing new inductions of medications for opioid use disorder (MOUD) within jails (Flanagan Balawajder et al. 2025; Hoover et al. 2023), suggesting the need for a broader scoping review (Sucharew 2019).

In this study we aimed to identify harm reduction strategies that have been implemented across CLS in the United States. We used the Sequential Intercept Model (SIM) to extend beyond initial policing encounters and include integration of harm reduction strategies across the spectrum of complex interactions and entanglements with jails, courts, prison, and community supervision (probation/parole) (Munetz and Griffin 2006). Our review was guided by the central research question—what harm reduction strategies to address illicit drug use are being implemented in and across different intercepts of the criminal legal system?—to identify innovation and gaps across the intercepts of these systems.

Methods

The scoping review was conducted using Arksey & O’Malley’s five-step framework: (1) identifying the research question, (2) identifying relevant studies, (3) study selection, (4) charting the data, and (5) collating, summarizing, and reporting the results. Review methodology and reporting is presented in accordance with the PRISMA Scoping Review (PRISMA-ScR) checklist (Tricco et al. 2018). An unregistered protocol exists and can be provided upon request.

Search strategy

The search strategy was developed in consultation with a CLS workgroup funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse. The research team identified key terms to capture implementation of harm reduction strategies in and across relevant intercepts of the CLS, informed by SAMHSA’s Harm Reduction Framework and the SIM.

The literature search combined the selected key terms using Boolean operators to find relevant English-language, peer-reviewed articles published between January 1, 2015, and December 31, 2024. The search was conducted by an information services specialist on February 5, 2025, within the following databases: PubMed, Web of Science, APA PsycInfo, Criminal Justice Database, EBSCO Discovery Services, Google Scholar, and Perplexity.ai (see Supplemental Appendix A for the full electronic search strategy).

Article selection

Articles were reviewed using the DistillerSR platform (2023). This software automates and manages the process of screening and abstraction, including the preservation of a full audit trail of inclusion/exclusion decisions, and adjudication in cases of disagreement. Of note, the Harm Reduction Framework describes meeting PWUD “where they are, engaging with them and providing support,” as fundamental to harm reduction; consequently, strategies may be “inclusive of abstinence as a chosen pathway but not inclusive of abstinence as a coerced pathway.” (2023) For this review, we defined harm reduction as noncoercive strategies aimed at minimizing the negative consequences of illicit drug use, including overdose education, naloxone distribution or administration, MOUD, non–medication-based treatment, drug checking, wound care, and diversion or referral to supportive services.

The SIM was originally developed to identify key points where individuals with behavioral health disorders can be diverted into services instead of progressing deeper into the criminal-legal system (Munetz and Griffin 2006). Of the six intercepts defined by the SIM, the scoping review focused on: (1) law enforcement and policing; (2) initial detention and court hearings; (3) custody in jails and courts; (4) reentry into the community following incarceration; and (5) community corrections, where there is surveillance by corrections agencies like probation (community supervision instead of further jail/prison) or parole (supervised release after prison). We intentionally exclude intercept 0: community services prior to entry into the system, because it does not inherently demonstrate CLS involvement.

Eligible articles included empirical studies, protocols, program and policy evaluations, model overview/description, or case studies (article type) in English (language) reporting on a harm reduction strategy targeting illicit drug use (intervention) for PWUD as a primary or secondary target (population) in a CLS intercept or by a CLS provider in the United States (setting). We developed screening guides for both title and abstract and full-text review phases, including detailed definitions and examples of all inclusion criteria. For example, following a joint review of the screening guide, team of researchers screened the titles and abstracts of the articles identified in the initial search to determine eligibility for full-text review and identify opportunities for further handsearching, where applicable. All abstracts marked for inclusion advanced to full-text review; any exclusions required confirmation by a second reviewer.

In full-text review, inclusion criteria in the screening guide were expanded to include article scope, such that eligible articles documented discrete implementation, or implementations, of a harm reduction strategy rather than presented prevalence of harm reduction strategies more broadly. Articles that reported on multiple instances of implementation were included as long as the eligible harm reduction strategy was being implemented in tandem across sites (e.g., multiple jails within a state implementing the same intervention) or the article documented implementation of each intervention separately. The screening form also included a field for reviewers to flag instances where articles described conditions or prerequisites for participation in or receipt of the harm reduction intervention. The lead author reviewed all flagged articles to exclude any in which interventions included some form of abstinence (e.g., opiate-free/detox) or coercion (e.g., participation as a condition of release) as a requisite of the intervention. This step was carried out as an additional quality assurance measure to ensure consistency in our operationalization of harm reduction, particularly as it pertains to any potentially coercive practices.

All reviewers piloted full-text review on the same 12 articles and resolved disagreements by discussion before proceeding to the rest of the review. During both title and abstract screening and full-text review, DistillerSR’s AI capabilities were used to continually prioritize articles with a high likelihood of meeting our inclusion criteria. We conducted dual independent review for all full-text articles, with any conflicts resolved by the lead author. For the final 20 percent of articles in full-text review, one of two independent reviewers were substituted with DistillerSR’s AI function for screening. In this process, DistillerSR completed the same full-text screening form as the human reviewer for each article. Any disagreements regarding inclusion or exclusion between the AI function and human reviewer were resolved by the lead author. Specifically, in any cases of disagreement (AI-involved or not), the lead author reviewed the full-text article, checked reviewer inputs, and resolved disagreements on the screening form, including the subsequent determination to include or exclude the article.

Data abstraction & synthesis

The study team extracted data about each included study using DistillerSR. The abstraction form included study identifiers and detailed information about the intervention. This included CLS intercept, or intercepts, that the intervention was implemented within; harm reduction strategy, or strategies, used; a description of the target population, including whether PWUD were a primary or secondary target of the intervention; timeframe of the intervention, including whether ongoing, study-limited, or ended; state and urbanicity of implementation area; and level of key stakeholder involvement, including whether the study team participated in implementation and the degree of involvement by the CLS setting and any non-CLS government agencies. All reviewers piloted data abstraction on the same four articles and resolved disagreements by discussion prior to full, independent extraction using the calibrated form. Each data abstraction was reviewed by the lead author for accuracy.

Prior to synthesis, data were reviewed to identify when multiple publications described the same instance of intervention implementation. These were then consolidated, as appropriate, to reflect a single implementation of a harm reduction strategy.

Results

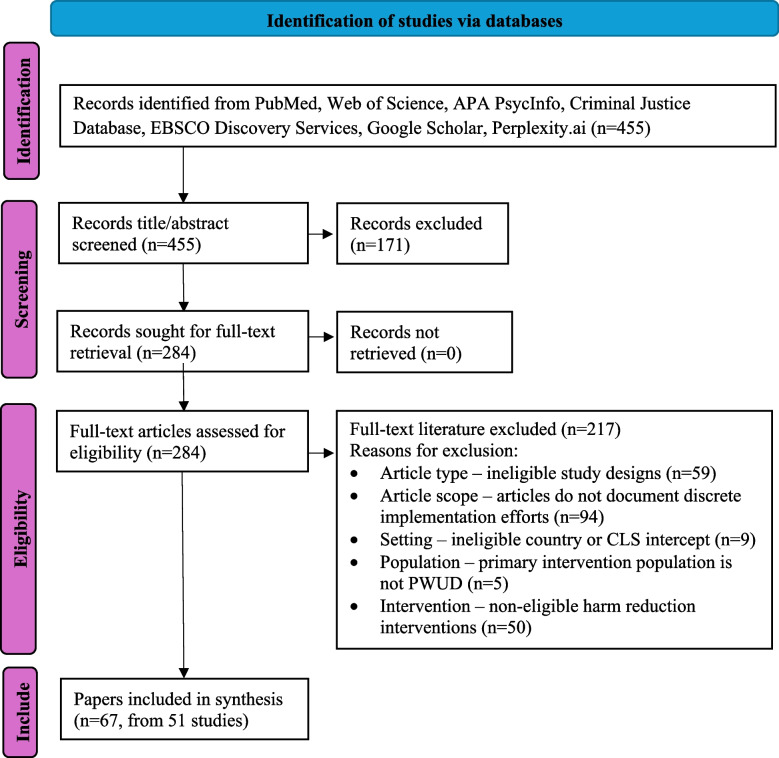

From 455 records identified, we included 67 articles reflecting 51 discrete instances of implementation (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

PRISMA Flow Diagram

For nearly three-quarters (n = 38, 74.5%), people with or at risk of opioid use disorder (OUD) were a primary target of the intervention; these interventions frequently included MOUD and CLS referral/diversion strategies, either separately or together (Table 1). In contrast, the interventions that did not directly engage with OUD populations were more likely to provide overdose education or naloxone distribution, most often to law enforcement officers. Interventions were carried out over a wide range of reported states, with notable concentrations in California (n = 6), Massachusetts (n = 6), Maryland (n = 6), and Rhode Island (n = 5). Of the 40 interventions that reported urbanicity of the implementation area, most were in mixed (n = 20), urban (n = 12), or suburban (n = 6) settings; only two interventions were carried out solely in rural areas.

Table 1.

Overview of included studies

| Article(s) | CLS Intercept | Harm reduction strategies | Population | PWUD Primary or Secondary | Timeframe | State(s) | Urbanicitya | Involvement in Implementation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study Team | CLS Actors | Non-CLS Agency | ||||||||

|

Ryan, (2025) Stopka, (2024) Stopka, (2022) Matsumoto, (2022) |

3, 4 | MOUD, CLS referral/diversion | Incarcerated individuals with OUD | Primary | Ongoing or planned to be ongoing | MA | Mix | No | Led | Consulted |

|

Martin, (2023) Kaplowitz, (2023) Martin, (2022) Martin, (2019) Green, (2018) |

3, 4 | MOUD, CLS referral/diversion | Incarcerated individuals with OUD | Primary | Ongoing or planned to be ongoing | RI | Unspecified | No | Led | None |

|

Mitchell, (2016) Friedman, (2015) |

3, 4, 5 | CLS referral/diversion | Community corrections staff and community health agencies | Secondary | Has or will end (study-limited) | AZ, CA, CT, DE, IL, KY, MD, PA, RI | Unspecified | Yes | Received information | None |

|

Blue, (2019) Vocci, (2015) |

3, 4 | MOUD, Non-medication treatment of illicit drug use | Incarcerated individuals with OUD nearing release | Primary | Has or will end (study-limited) | MD | Unspecified | Yes | None | None |

|

Payne, (2024) Lloyd, (2023) Pourtaher, (2022) |

1 | Overdose education, Naloxone distribution or administration | Law enforcement | Secondary | Ongoing or planned to be ongoing | NY | Mix | Yes | Involved | Collaborated |

|

Gilbert, (2023) Paul, (2018) |

1 | CLS referral/diversion | PWUD who would otherwise be charged with low-level criminal offenses or be at risk for future arrest | Primary | Ongoing or planned to be ongoing | NC | Mix | No | Led | None |

|

Dahlem, (2023a) Dahlem, (2023b) |

1 | Overdose education | Law enforcement officers | Secondary | Has or will end (study-limited) | MI | Urban | Yes | Collaborated | None |

|

Dahlem, (2022) Dahlem, (2017) |

1 | Overdose education, Naloxone distribution or administration | Law enforcement officers | Secondary | Has or will end (study-limited) | MI | Suburban | Yes | Led | None |

|

Molfenter, (2025) Vechinski, (2023) Molfenter, (2021) |

3 | MOUD, Other; implementation training and coaching for MOUD delivery | Jails seeking TA to implement or expand MOUD practices within their site or increase MOUD use post-incarceration | Secondary | Has or will end (study-limited) | 48 providers nationally | Unspecified | Yes | Involved | None |

| Yang, (2019) | 4, 5 | MOUD, Non-medication treatment of illicit drug use | Male offenders (most on probation or parole) who were referred to community based MAT treatment | Primary | Has or will end (study-limited) | Large city in the Midwest | Urban | Yes | None | None |

| Victor, (2024) | 3, 4 | Naloxone distribution or administration, CLS referral/diversion | Jail visitors and those who were recently released from jail; those being released from jail (either those with suspected OUD or by request) | Primary | Ongoing or planned to be ongoing | MI | Mix | No | Led | None |

| Victor, (2023) | 3, 4, 5 | MOUD, Non-medication treatment of illicit drug use, CLS referral/diversion | Individuals in prison with co-occurring OUD and mental health disorders | Primary | Ongoing or planned to be ongoing | Midwestern state | Unspecified | No | Led | None |

| Lee, (2021) | 3, 4 | MOUD, CLS referral/diversion | Adults with OUD incarcerated in jail & nearing release/post-release | Primary | Ongoing or planned to be ongoing | NY | Urban | No | Led | Collaborated |

| Martin, (2025) | 3, 5 | Naloxone distribution or administration, Drug checking test strips, Wound care supplies | Justice-involved individuals being served by the DOC (for those incarcerated, those leaving), as well as the general public | Primary | Ongoing or planned to be ongoing | RI | Unspecified | No | Led | None |

| Tamburello, (2024) | 3 | MOUD | Incarcerated persons with OUD | Primary | Ongoing or planned to be ongoing | NJ | Unspecified | No | Led | None |

| Ray, (2024) | 3 | Overdose education, Naloxone distribution or administration, CLS referral/diversion | PWUD in the court system | Primary | Ongoing or planned to be ongoing | CT, ME, MA | Mix | No | Led | None |

| Pourtaher, (2024) | 3 | Naloxone distribution or administration, MOUD, CLS referral/diversion | Incarcerated individuals with OUD | Primary | Ongoing or planned to be ongoing | NY | Unspecified | No | Led | Involved |

| Purviance, (2017) | 1 | Overdose education | Law enforcement officers who respond to potential opioid overdoses | Secondary | Has or will end (other) | IN | Mix | No | Received information | None |

| Showalter, (2021) | 3 | Overdose education, Naloxone distribution or administration | People exiting jail | Primary | Ongoing or planned to be ongoing | CA | Mix | No | Led | Involved |

| Wenger, (2019) | 3 | Overdose education, Naloxone distribution or administration | Incarcerated adults within 30 days of their release date | Primary | Ongoing or planned to be ongoing | CA | Unspecified | No | Led | Collaborated |

| Sprunger, (2024) | 3, 4 | Overdose education, Naloxone distribution or administration, MOUD, CLS referral/diversion | Incarcerated individuals, including re-entering from incarceration | Primary | Unclear | OH | Mix | No | Led | None |

| Neeki, (2024) | 3, 4 | Overdose education, Naloxone distribution or administration, MOUD, CLS referral/diversion | Youth with OUD in corrections facilities | Primary | Ongoing or planned to be ongoing | CA | Unspecified | No | Collaborated | Collaborated |

| Lim, (2024) | 3, 4 | MOUD, CLS referral/diversion | Adults with OUD who were incarcerated and released to the community | Primary | Ongoing or planned to be ongoing | NY | Urban | No | Led | None |

| Gimbel, (2024) | 3, 4 | MOUD, CLS referral/diversion | Individuals on MOUD during incarceration, subsequently referred to MOUD clinics in the community upon release | Primary | Ongoing or planned to be ongoing | WA | Unspecified | Yes | Led | None |

| Fix, (2024) | 5 | Non-medication treatment of illicit drug use | Youth with SUD in juvenile probation settings | Primary | Unclear | ID, OR, NV | Mix | No | Unclear | None |

| Belcher, (2024) | 3 | MOUD | Incarcerated individuals with diagnosed OUD | Primary | Ongoing or planned to be ongoing | MD | Rural | No | Collaborated | None |

| Bailey, (2024) | 3 | MOUD, CLS referral/diversion | Court-involved individuals with OUD | Primary | Ongoing or planned to be ongoing | MA | Unspecified | Yes | Led | None |

| Klemperer, (2023) | 3 | MOUD | Incarcerated individuals with OUD | Primary | Ongoing or planned to be ongoing | VT | Unspecified | No | Led | |

| Donnelly, (2023) | 1 | CLS referral/diversion | People with SUD seeking help or in lieu of arrest | Primary | Ongoing or planned to be ongoing | DE | Suburban | No | Collaborated | Involved |

| Perrone, (2022) | 1 | CLS referral/diversion | PWUD or sex workers at risk of arrest | Primary | Ongoing or planned to be ongoing | CA | Urban | No | Led | Collaborated |

| Hunt, (2022) | 3 | Overdose education | Female jail inmates | Primary | Ongoing or planned to be ongoing | TN | Rural | Yes | Led | Collaborated |

| Gooley, (2022) | 1 | Overdose education | Law enforcement officers | Secondary | Ongoing or planned to be ongoing | WI | Urban | No | Collaborated | None |

| Evans, (2022) | 3 | MOUD | Incarcerated individuals with OUD | Primary | Ongoing or planned to be ongoing | MA | Mix | No | Led | None |

| Staton, (2021) s | 3, 4 | MOUD, CLS referral/diversion | Women with OUD nearing release from jail | Primary | Has or will end (study-limited) | KY | Unspecified | No | Collaborated | Collaborated |

| Reed, (2021) | 3 | Overdose education | HIV positive, incarcerated adults | Primary | Has or will end (study-limited) | PA | Urban | Yes | Collaborated | None |

| Matusow, (2021) | 2, 3, 5 | CLS referral/diversion | OUD clients under judge supervision | Primary | Unclear | OH | Mix | No | Involved | None |

| Gallagher, (2021) | 2, 3, 4 | MOUD | Justice-involved adults with diagnosed OUD | Primary | Ongoing or planned to be ongoing | IN | Unspecified | No | Led | None |

| Donelan, (2021) | 3, 4 | MOUD, Non-medication treatment of illicit drug use, CLS referral/diversion | Individuals in jail with OUD | Primary | Ongoing or planned to be ongoing | MA | Unspecified | Yes | Led | Involved |

| Adams, (2021) | 1 | Overdose education | Law enforcement officers | Secondary | Has or will end (study-limited) | IN | Unspecified | Yes | Involved | None |

| Winograd, (2020) | 1 | Overdose education | Law enforcement officers | Secondary | Has or will end (study-limited) | MO | Mix | No | Received information | None |

| Waddell, (2020) | 3, 4, 5 | Overdose education, Naloxone distribution or administration, MOUD, Non-medication treatment of illicit drug use, CLS referral/diversion | Women nearing release from prison | Primary | Has or will end (study-limited) | OR | Urban | Yes | Involved | None |

| Nath, (2020) | 1 | Overdose education | Law enforcement officers | Secondary | Has or will end (other) | MD | Suburban | No | Led | None |

| Lowder, (2020) | 1 | Overdose education, Naloxone distribution or administration | Police officers | Secondary | Has or will end (other) | IN | Urban | No | Led | Collaborated |

| Banta-Green, (2020) | 3 | Non-medication treatment of illicit drug use, CLS referral/diversion | Incarcerated adults with potential OUD nearing release from jail | Primary | Ongoing or planned to be ongoing | WA | Unspecified | No | Led | None |

| Rouhani, (2019) | 1 | CLS referral/ | People who use drugs at risk for police interaction/incarceration | Primary | Has or will end (study-limited) | MD | Urban | No | Collaborated | Collaborated |

| Krawczyk, (2019) | 3 | MOUD, CLS referral/diversion | Persons with OUD who are exiting jail or who have been recently incarcerated | Primary | Ongoing or planned to be ongoing | MD | Urban | No | Collaborated | None |

| Gicquelais, (2019) | 3 | CLS referral/diversion | Justice involved adults with history of opioid misuse | Primary | Has or will end (study-limited) | MI | Suburban | No | Involved | None |

| Ferguson, (2019) | 3, 4 | MOUD, CLS referral/diversion | Incarcerated individuals with OUD | Primary | Ongoing or planned to be ongoing | RI, CT, MA | Unspecified | No | Led | Involved |

| Wagner, (2016) | 1 | Overdose education, Naloxone distribution or administration, CLS referral/diversion | Law enforcement officers | Secondary | Has or will end (study-limited) | CA | Mix | Yes | Collaborated | Collaborated |

| Saucier, (2016) | 1 | Overdose education | Law enforcement officers | Secondary | Ongoing or planned to be ongoing | RI | Unspecified | No | Involved | None |

| Kitch, (2016) | 1 | Overdose education, Naloxone distribution or administration | Law enforcement officers | Secondary | Ongoing or planned to be ongoing | NC | Unspecified | No | Collaborated | Collaborated |

CLS criminal-legal systems, PWUD person who uses drugs, MOUD medication for opioid use disorder

aUrbanicity reflects how each article’s authors described the implementation area (e.g., urban, rural, suburban, mixed). If urbanicity was not explicitly stated in the article, it is coded as “unspecified.”

Nearly one-third of interventions (n = 15, 29.4%) involved direct participation in implementation by study-affiliated staff, with roles such as providing MOUD to incarcerated individuals or leading overdose education and naloxone distribution training for law enforcement officers. Notably, these interventions were more frequently time-limited and part of defined research studies (e.g., randomized controlled trials), whereas those without study team involvement were typically non-empirical descriptions of a preexisting program.

Staff at the CLS settings in which the interventions took place were often deeply involved, with roles that ranged from leading (n = 27) or collaborating with the study team or community partners (n = 11) to plan and implement the intervention. In other instances, the staff at CLS settings were not responsible for initiating the intervention but were involved in its delivery (n = 7). In rare cases, CLS setting involvement was limited to receiving the intervention (n = 3) or simply serving as the site of implementation (n = 2).

Non-CLS government agencies, spanning federal, state, or local entities, were engaged in some capacity in one-third of interventions (n= 17). Among these interventions, the degree of involvement varied. For example, the New York State (NYS) Naloxone Distribution program was developed by a partnership of public health and public safety agencies, including the NYS Department of Health, Division of Criminal Justice Services, Albany Medical Center, the Harm Reduction Coalition, and the Office of Addiction Services and Supports (Pourtaher et al. 2022; Payne et al. 2024). In other instances, representatives from these agencies contributed to developing or delivering training. For instance, the Healthy Outcomes Post Release Education (HOPE) program (Hunt et al. 2022), an overdose education intervention for incarcerated women in a rural area of Tennessee (TN), includes a TN Department of Health training course on the use and administration of intranasal naloxone for opioid overdose. A nurse educator from the Department of Health was also involved in program delivery.

Across CLS intercepts

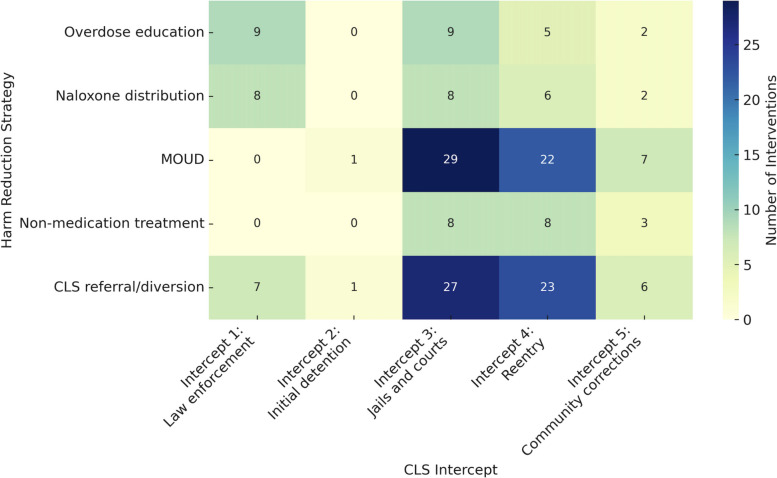

Harm reduction interventions targeting illicit drug use were implemented across all five CLS intercepts, although the frequency and type of intervention ranged widely (Fig. 2). We mapped the distribution of each documented harm reduction strategy against each SIM intercept; notably, these frequencies exceed the number of interventions because most interventions (n = 42, 82.4%) involved multiple harm reduction strategies (e.g., combining MOUD and CLS referral/diversion).

Fig. 2.

Heatmap of Harm Reduction Strategies by CLS Intercept

Intercept 1: law enforcement

Harm reduction strategies implemented in Intercept 1 included overdose education, naloxone distribution or administration, and CLS referral/diversion. Wagner and colleagues described a pilot program in California that included aspects of all three strategies: deputies were trained on overdose recognition, response techniques, and protocols—including a procedure for referring overdose victims to substance use treatment—and were provided with intranasal naloxone kits at the beginning of each shift (Wagner et al. 2016).

Intercept 2: initial detention and court hearings

We only identified two instances of harm reduction strategies (MOUD and CLS referral/diversion) at Intercept 2, each carried out in the context of drug courts. Gallagher and colleagues carried out a focus group analysis of a drug court in Indiana that incorporated MOUD into its programming, offering new inductions of buprenorphine/suboxone, methadone, and naltrexone to justice-involved adults when clinically warranted (Gallagher et al. 2021). The second instance was a pilot test of an intervention designed to increase referrals to MOUD in Ohio drug courts (Kaplowitz et al. 2023).

Intercept 3: custody in jails and courts

Intercept 3 had the highest overall frequency of implemented harm reduction strategies, with MOUD and CLS referral/diversion most commonly reported. However, several interventions in this intercept also incorporated overdose education and naloxone distribution for incarcerated individuals approaching release. For example, Wenger and colleagues reported on the San Francisco County Jail overdose education and naloxone distribution program, which involves showing an overdose education video and providing one-on-one private training for people approaching release from incarceration (Wenger et al. 2019).

Intercept 4: reentry

No interventions in the review were implemented exclusively at Intercept 4; all reentry-focused implementations were part of broader initiatives that typically included Intercept 3. Indeed, nearly one-third of all interventions (n= 16, 31.4%) spanned both Intercepts 3 and 4. For example, multiple articles reported on the Rhode Island Department of Corrections’ comprehensive MOUD program, which includes screening all incarcerated individuals for OUD; continuing or initiating individuals on buprenorphine/suboxone, methadone, or naltrexone while incarcerated; and linking individuals with treatment in the community post-release, typically with the same contracted behavioral health organization that provides MOUD pre-release to ensure continuity of care (Green et al. 2018; Kaplowitz et al. 2023; Martin et al. 2023, 2022, 2019).

Intercept 5: community corrections

Intercept 5 featured fewer interventions than Intercepts 3 and 4 but similarly spanned all harm reduction strategy types. As with Intercept 4 the interventions that took place in community corrections were typically tied to Intercepts 3 or 4. For exampleVictor et al. described a Midwestern reentry program for incarcerated individuals with co-occurring opioid use and mental health disorders, in which participants were assigned a case manager and peer support specialist that facilitated MOUD, dual recovery therapy in the 3 months pre-release through up to 6 months post-release, and referrals to community treatment upon reentry. (Victor et al. 2023)The only identified intervention that was bounded within Intercept 5 was a randomized controlled trial conducted by Fix and colleagues among adolescents with substance use disorder under probation orders in Idaho, Oregon, and Nevada (Fix et al. 2024). The experimental condition comprised substance use contingency management (i.e., a behavioral therapy that uses positive reinforcement for desired behaviors), provided as part of the adolescents’ probation by their juvenile probation officer.

Discussion

This scoping review found that harm reduction strategies are being implemented across nearly every intercept of the CLS in the United States, although frequency and scope of intervention vary substantially. The majority of interventions occurred in Intercept 3 (jails and courts), where strategies most often included MOUD, naloxone distribution, and CLS referral/diversion. Nearly one-third of interventions spanned both Intercepts 3 and 4 (reentry), which reflects efforts to maintain continuity of care during reentry. Intercept 1 (law enforcement) comprised interventions where PWUD were a secondary target of the harm reduction intervention, including overdose education delivered to law enforcement officers. Other common strategies in this setting included naloxone distribution and CLS referral/diversion. In contrast, few interventions were identified as taking place in Intercept 2 (initial detention and court hearings), no intervention was implemented solely within Intercept 4, and just one intercept was bounded within Intercept 5 (community corrections). Most interventions featured multiple harm reduction strategies, and MOUD and CLS referral/diversion were most commonly paired.

The prominence of jail-based interventions in our review may be, in part, a reflection of the definition of harm reduction used in our review. Though medications are generally prescribed as part of standard treatment for OUD, they can be delivered outside of traditional clinical settings as a tool to reduce harm. Screening persons at booking for OUD, initiating medications that reduce painful withdrawal symptoms, and providing naloxone at discharge is reducing harm for PWUD, and thereby falls within the scope of our review. However, it is also important to recognize that access to MOUD in jail is required by federal law, and facilities that do not provide the medications are a violation of disability rights protections under the Americans with Disabilities Act (Macmadu et al. 2020). Not providing these medications not only disrupts essential medical care but can increase risk of withdrawal, relapse, and overdose (Joudrey et al. 2019). As a result, interventions involving MOUD in Intercept 3 may represent both a harm reduction strategy and a legal imperative. Additionally, these interventions largely reflect a clinical focus that prioritizes medication access but does not inherently address risk factors for illicit drug use.

In contrast, there were few examples of harm reduction strategies at Intercept 2 (initial detention and court hearings). One concerned MOUD in a drug court program, which met our criteria and similarly reflects the legal requirements noted above. The other was an example of peer recovery specialists working as navigators in courthouse settings. Despite research on the risk of overdose following incarceration in a prison facility, our review surprisingly found no studies reporting on implementing harm reduction strategies solely within prison settings (Brinkley-Rubinstein et al. 2017; Pizzicato et al. 2018; Binswanger et al. 2011, 2013; Hill et al. 2024; Ray et al. 2023b; Seaman et al. 1998). This gap may reflect reporting limitations or true lack of implementation. Our findings support calls for harm reduction strategies to support PWUD upon reentry (Brinkley-Rubinstein et al. 2017; Curtis et al. 2018).

While our scoping review is descriptive by design, our results depict geographic patterns reflecting where implementation has predominantly occurred and includes clusters in California, Maryland, Massachusetts, and Rhode Island. These areas have long histories of supporting syringe services, naloxone distribution, and substance use treatment, and benefit from collaborations between public agencies and researchers (Bramson et al. 2015). Moreover, state-level efforts (such as Rhode Island Department of Corrections’ comprehensive MOUD screening program) signify larger, incremental shifts within harm reduction expansion. The geographic spread observed in this review prompts questions related to equity of access to harm reduction strategies, particularly in regions with more punitive drug policies or limited public health infrastructure. Similarly, other structural or policy contexts (e.g., funding models, political climate, legal mandates) no doubt play a role in the shifting harm reduction landscape and merit future research.

Limitations

The definition of harm reduction has notoriously been contested, and a debate continues among government agencies – and especially criminal-legal agencies – who seek to integrate harm reduction approaches without undermining mandates to criminalize drugs and drug use. At the same time, debate also occurs among harm reduction practitioners who are concerned that its radical roots—centered on user autonomy and social justice—can be diluted during integration. Our use of the HHS definition of harm reduction as “a practical and transformative approach that incorporates community-driven public health strategies — including prevention, risk reduction, and health promotion — to empower PWUD and their families with the choice to live healthier, self-directed, and purpose-filled lives” is grounded in current policy. However, it may not fully capture the breadth of non-clinical harm reduction interventions being implemented in grassroots settings. Similarly, we excluded grey literature from our scoping review to ensure necessary information for coding and to limit the introduction of bias from nonstandardized reporting or unpublished results that limit replication. The focus on peer-reviewed literature hampers our ability to identify all harm reduction interventions, particularly in grassroots settings. Conversely, some of the MOUD interventions we identified in this may reflect a simple fulfillment of a legal mandate rather than a true effort to reduce harm for PWUD. Knowing the intentionality behind these efforts is beyond our scope, and so we have elected to include some MOUD efforts as harm reduction rather than exclude all of them. Our review period (January 2015 through December 2024) means that we missed some of the initial onset of studies documenting harm reduction strategies within the CLS. For example, naloxone distribution, most often offered to law enforcement officers and intended for use with PWUD intersecting with CLS, was first pioneered prior to the review period and was therefore not as widely reported as we may have expected (Davis et al. 2014; Green et al. 2013). We also limited our review to the United States and harm reduction focused on illicit drug use, not infectious disease. Finally, it was beyond the scope of our current review, and beyond that of this current literature base, to review the efficacy of the implementation of the harm reduction strategies.

Conclusions

Despite the recent decrease in overdose deaths in the United States, there remains an urgent need to reduce harms associated with illicit drug use, particularly for PWUD with CLS involvement. Our scoping review findings demonstrate a clear need for more innovation and research into the implementation of harm reduction strategies across CLS in the United States. Criminal justice practitioners are slowly integrating a public-health approach to drug use, developing and implementing a number of new and innovative practices (e.g., pilot implementations of jail-based MOUD) but much of the current implementation of harm reduction interventions within the CLS is likely driven by legal mandates, or restrictions, in the United States. For example, syringe distribution is an evidence-based harm reduction strategy that has been implemented in multiple prison systems globally (Dolan et al. 2003), but is not prevalent in the United States because syringe distribution is still criminalized.

Perspectives from CLS and harm reduction stakeholders are needed, particularly as it pertains to harm reduction practices that can be integrated into CLS outside of legal mandates or systematic changes. Additionally, the first funding for harm reduction services research in the United States only occurred 3 years prior to this review period. We anticipate that harm reduction strategies are being implemented in more CLS settings, warranting an update of this scoping review in the future. Indeed, this scoping review lays the groundwork for further research into implementation, including evaluation of barriers and facilitators using a theoretical framework (e.g., the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research) to help guide expansion of harm reduction strategies in the CLS.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the members of the NIDA-funded criminal legal services workgroup for their guidance and feedback on the development of this review.

Authors’ contributions

K.J. and B.R. wrote the main manuscript text and K.J., S.V.P., J.C., and B.R. led development of the screening and data abstraction tools. I.R.B. oversaw DistillerSR programming and prepared Fig. 1. I.R.B., M.C., J.C., M.D., and S.M.P. conducted screening and data abstraction. K.J. reviewed all abstractions for accuracy and led data synthesis, including preparing Table 1 and Fig. 2. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Helping to End Addiction Long-Term (HEAL) Initiative®, through a coordinating center grant (U24DA057611-03S1). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Data availability

The authors declare no competing interests.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Change history

11/13/2025

The original version of this article was revised: the grant number relating to National Institutes of Health (NIH) Helping to End Addiction Long-Term (HEAL) Initiative® in the Funding section was incorrectly given as U24DA057632 and should have been U24DA057611-03S1.

References

- Adams, J. M. (2020). Making the case for syringe services programs. Public Health Reports,135(1_suppl), 10s–12s. 10.1177/0033354920936233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams, N. (2021). Beyond Narcan: Comprehensive opioid training for law enforcement. Journal of Substance Use,26(4), 383–390. 10.1080/14659891.2020.1838639 [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, M. (2012). The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness (Rev. Ed.) New York: New Press

- Bailey, A., & Evans, E. A. (2024). Holyoke early access to recovery and treatment (HEART): A case study of a court-based intervention to reduce opioid overdose. Journal of Ethnicity in Substance Abuse,23(4), 1039–1061. 10.1080/15332640.2023.2172758 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balter, D. R., & Howell, B. A. (2024). Take-home naloxone, release from jail, and opioid overdose-a piece of the puzzle. JAMA Network Open,7(12), Article Article e2448667. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.48667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banta-Green, C. J., Williams, J. R., Sears, J. M., Floyd, A. S., Tsui, J. I., & Hoeft, T. J. (2020). Impact of a jail-based treatment decision-making intervention on post-release initiation of medications for opioid use disorder. Drug and Alcohol Dependence,207, Article 107799. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.107799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belcher, A. M., Kearley, B., Kruis, N., Rowland, N., Spicyn, N., Cole, T. O., Welsh, C., Fitzsimons, H., McLean, K., & Weintraub, E. (2024). Correlates of staff acceptability of a novel telemedicine-delivered medications for opioid use disorder program in a rural detention center. Journal of Correctional Health Care,30(4), 238–244. 10.1089/jchc.23.11.0097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhai, M., McMichael, B. J., & Mitchell, D. T. (2025). Impact of fentanyl test strips as harm reduction for drug-related mortality. Medical Care Research and Review,82(3), 240–251. 10.1177/10775587251316919 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binswanger, I. A., Blatchford, P. J., Lindsay, R. G., & Stern, M. F. (2011). Risk factors for all-cause, overdose and early deaths after release from prison in Washington state. Drug and Alcohol Dependence,117(1), 1–6. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.11.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binswanger, I. A., Blatchford, P. J., Mueller, S. R., & Stern, M. F. (2013). Mortality after prison release: Opioid overdose and other causes of death, risk factors, and time trends from 1999 to 2009. Annals of Internal Medicine,159(9), 592–600. 10.7326/0003-4819-159-9-201311050-00005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blue, T. R., Gordon, M. S., Schwartz, R. P., Couvillion, K., Vocci, F. J., Fitzgerald, T. T., & O’Grady, K. E. (2019). Longitudinal analysis of HIV-risk behaviors of participants in a randomized trial of prison-initiated buprenorphine. Addiction Science & Clinical Practice,14(1), Article 45. 10.1186/s13722-019-0172-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bramson, H., Des Jarlais, D. C., Arasteh, K., Nugent, A., Guardino, V., Feelemyer, J., & Hodel, D. (2015). State laws, syringe exchange, and HIV among persons who inject drugs in the United States: History and effectiveness. Journal of Public Health Policy,36(2), 212–230. 10.1057/jphp.2014.54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinkley-Rubinstein, L., Cloud, D. H., Davis, C., Zaller, N., Delany-Brumsey, A., Pope, L., Martino, S., Bouvier, B., & Rich, J. (2017). Addressing excess risk of overdose among recently incarcerated people in the USA: Harm reduction interventions in correctional settings. International Journal of Prisoner Health,13(1), 25–31. 10.1108/ijph-08-2016-0039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinkley-Rubinstein, L., Zaller, N., Martino, S., Cloud, D. H., McCauley, E., Heise, A., & Seal, D. (2018). Criminal justice continuum for opioid users at risk of overdose. Addictive Behaviors,86, 104–110. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.02.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, J. J., Mackin, S., Schmidt, C., McKenzie, M., & Green, T. C. (2022). The bronze age of drug checking: Barriers and facilitators to implementing advanced drug checking amidst police violence and COVID-19. Harm Reduction Journal,19(1), 9. 10.1186/s12954-022-00590-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciccarone, D., Kilmer, B., MacDonald, D. S., & Singer, J. A. (2019). Harm reduction: Shifting from a war on drugs to a war on drug-related deaths—Panel IV: Medication assisted treatment, including heroin assisted treatment and closing remarks. DC, Hayek Auditorium, Cato Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Curtis, M., Dietze, P., Aitken, C., Kirwan, A., Kinner, S. A., Butler, T., & Stoové, M. (2018). Acceptability of prison-based take-home naloxone programmes among a cohort of incarcerated men with a history of regular injecting drug use. Harm Reduction Journal,15(1), 48. 10.1186/s12954-018-0255-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahlem, C. H., Granner, J., & Boyd, C. J. (2022). Law enforcement perceptions about naloxone training and its effects post-overdose reversal. Journal of Addictions Nursing,33(2), 80–85. 10.1097/jan.0000000000000456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahlem, C. H. G., King, L., Anderson, G., Marr, A., Waddell, J. E., & Scalera, M. (2017). Beyond rescue: Implementation and evaluation of revised naloxone training for law enforcement officers. Public Health Nursing,34(6), 516–521. 10.1111/phn.12365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahlem, C. H., King, L., Marr, A., & Holliday, E. (2023b). Web-based naloxone training for law enforcement officers: A pilot feasibility study. Progress in Community Health Partnerships-Research Education and Action,17(2), 255–264. 10.1353/cpr.2023.a900206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahlem, C. H., Patil, R., Khadr, L., Ploutz-Snyder, R. J., Boyd, C. J., & Shuman, C. J. (2023a). Effectiveness of take ACTION online naloxone training for law enforcement officers. Health & Justice, 11(1), 10, Article 47. 10.1186/s40352-023-00250-9

- Davis, C. S., Southwell, J. K., Niehaus, V. R., Walley, A. Y., & Dailey, M. W. (2014). Emergency medical services naloxone access: A national systematic legal review. Academic Emergency Medicine,21(10), 1173–1177. 10.1111/acem.12485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Des Jarlais, D. C. (2017). Harm reduction in the USA: The research perspective and an archive to David Purchase. Harm Reduction Journal,14(1), 51. 10.1186/s12954-017-0178-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DistillerSR. (2023). DistillerSR. Version 2.35. DistillerSR Inc. Retrieved from https://www.distillersr.com/

- Doe-Simkins, M., & Wheeler, E. J. (2025). Overdose education and naloxone distribution: An evidence-based practice that warrants course correcting. American Journal of Public Health,115(1), 6–8. 10.2105/ajph.2024.307893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolan, K., Rutter, S., & Wodak, A. D. (2003). Prison-based syringe exchange programmes: A review of international research and development. Addiction,98(2), 153–158. 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2003.00309.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donelan, C. J., Hayes, E., Potee, R. A., Schwartz, L., & Evans, E. A. (2021). COVID-19 and treating incarcerated populations for opioid use disorder. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment,124, Article 108216. 10.1016/j.jsat.2020.108216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donnelly, E. A., O’Connell, D. J., Stenger, M., Arnold, J., & Gavnik, A. (2023). Law enforcement-based outreach and treatment referral as a response to opioid misuse: Assessing reductions in overdoses and costs. Police Quarterly,26(4), 441–465. 10.1177/10986111221143784 [Google Scholar]

- Evans, E. A., Pivovarova, E., Stopka, T. J., Santelices, C., Ferguson, W. J., & Friedmann, P. D. (2022). Uncommon and preventable: Perceptions of diversion of medication for opioid use disorder in jail. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment,138, Article 108746. 10.1016/j.jsat.2022.108746 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foreman-Mackey, A., Pauly, B., Ivsins, A., Urbanoski, K., Mansoor, M., & Bardwell, G. (2022). Moving towards a continuum of safer supply options for people who use drugs: A qualitative study exploring national perspectives on safer supply among professional stakeholders in Canada. Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy,17(1), 66. 10.1186/s13011-022-00494-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes, R. M., Cary, M., Duarte, G., Jesus, G., Alarcão, J., Torre, C., Costa, S., Costa, J., & Carneiro, A. V. (2017). Effectiveness of needle and syringe programmes in people who inject drugs – An overview of systematic reviews. BMC Public Health,17(1), 309. 10.1186/s12889-017-4210-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson, W. J., Johnston, J., Clarke, J. G., Koutoujian, P. J., Maurer, K., Gallagher, C., White, J., Nickl, D., & Taxman, F. S. (2019). Advancing the implementation and sustainment of medication assisted treatment for opioid use disorders in prisons and jails. Health Justice,7(1), 19. 10.1186/s40352-019-0100-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flanagan Balawajder, E., Ducharme, L., Taylor, B. G., Lamuda, P. A., Kolak, M., Friedmann, P. D., Pollack, H. A., & Schneider, J. A. (2025). Barriers to universal availability of medications for opioid use disorder in US jails. JAMA Network Open,8(4), e255340. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2025.5340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedmann, P. D., Wilson, D., Knudsen, H. K., Ducharme, L. J., Welsh, W. N., Frisman, L., Knight, K., Lin, H. J., James, A., Albizu-Garcia, C. E., Pankow, J., Hall, E. A., Urbine, T. F., Abdel-Salam, S., Duvall, J. L., & Vocci, F. J. (2015). Effect of an organizational linkage intervention on staff perceptions of medication-assisted treatment and referral intentions in community corrections. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment,50, 50–58. 10.1016/j.jsat.2014.10.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fix, R. L., Walsh, C. S., Sheidow, A. J., McCart, M. R., Chapman, J. E., & Drazdowski, T. K. (2024). Juvenile probation officers delivering an intervention for substance use significantly reduces adolescents’ risky sexual behaviours. Sex Health. 10.1071/sh23181 [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher, J. R., Nordberg, A., Francis, Z., Menon, P., Canada, M., & Minasian, R. M. (2021). A focus group analysis with a drug court team: Opioid use disorders and the role of medication-assisted treatment (MAT) in programming. Journal of Social Work Practice in the Addictions,21(2), 139–148. 10.1080/1533256x.2021.1912964 [Google Scholar]

- Gicquelais, R. E., Mezuk, B., Foxman, B., Thomas, L., & Bohnert, A. S. B. (2019). Justice involvement patterns, overdose experiences, and naloxone knowledge among men and women in criminal justice diversion addiction treatment. Harm Reduction Journal,16(1), 46. 10.1186/s12954-019-0317-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert, A. R., Siegel, R., Easter, M. M., Hofer, M. S., Sivaraman, J. C., Ariturk, D., Swanson, J. W., Swartz, M. S., Wygle, R., & Feng, G. (2023). North Carolina Law Enforcement Assisted Diversion (LEAD): Considerations for optimizing eligilibility and referral. Law and Contemporary Problems,86(1), 73. [Google Scholar]

- Gimbel, S., Basu, A., Callen, E., Flaxman, A. D., Heidari, O., Hood, J. E., Kellogg, A., Kern, E., Tsui, J. I., Turley, E., & Sherr, K. (2024). Systems analysis and improvement to optimize opioid use disorder care quality and continuity for patients exiting jail (SAIA-MOUD). Implementation Science,19(1), 80. 10.1186/s13012-024-01409-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gooley, B., Weston, B., Colella, M. R., & Farkas, A. (2022). Outcomes of law enforcement officer administered naloxone. American Journal of Emergency Medicine,62, 25–29. 10.1016/j.ajem.2022.09.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green, T. C., Clarke, J., Brinkley-Rubinstein, L., Marshall, B. D. L., Alexander-Scott, N., Boss, R., & Rich, J. D. (2018). Postincarceration fatal overdoses after implementing medications for addiction treatment in a statewide correctional system. JAMA Psychiatry,75(4), 405–407. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.4614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green, T. C., Zaller, N., Palacios, W. R., Bowman, S. E., Ray, M., Heimer, R., & Case, P. (2013). Law enforcement attitudes toward overdose prevention and response. Drug and Alcohol Dependence,133(2), 677–684. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.08.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guilamo-Ramos, V., Benzekri, A., Wilson, L., & Abram, M. D. (2025). Avoiding a new US “war on drugs.” BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.),388, Article r225. 10.1136/bmj.r225 [Google Scholar]

- Heller, D., McCoy, K., & Cunningham, C. (2004). An invisible barrier to integrating HIV primary care with harm reduction services: Philosophical clashes between the harm reduction and medical models. Public Health Reports,119(1), 32–39. 10.1177/003335490411900109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill, K., Bodurtha, P. J., Winkelman, T. N. A., & Howell, B. A. (2024). Postrelease risk of overdose and all-cause death among persons released from jail or prison: Minnesota, March 2020-December 2021. American Journal of Public Health,114(9), 913–922. 10.2105/ajph.2024.307723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoover, D. B., Korthuis, P. T., Waddell, E. N., Foot, C., Conway, C., Crane, H. M., Friedmann, P. D., Go, V. F., Nance, R. M., Pho, M. T., Satcher, M. F., Sibley, A., Westergaard, R. P., Young, A. M., & Cook, R. (2023). Recent incarceration, substance use, overdose, and service use among people who use drugs in rural communities. JAMA Network Open,6(11), e2342222. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.42222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt, J. D., Lord, M., Kapu, A. N., & Buckner, E. (2022). Promoting adaptation in female inmates to reduce risk of opioid overdose post-release through HOPE. Nursing Science Quarterly,35(4), 455–463. 10.1177/08943184221115123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inciardi, J. A. (1996). HIV risk reduction and service delivery strategies in criminal justice settings. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment,13(5), 421–428. 10.1016/S0740-5472(96)00117-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakubowski, A., Fowler, S., & Fox, A. D. (2023). Three decades of research in substance use disorder treatment for syringe services program participants: A scoping review of the literature. Addiction Science & Clinical Practice,18(1), 40. 10.1186/s13722-023-00394-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, K. A., Perkins, A. J., Obuya, C., & Wilkes, S. K. (2025). Enhancing HIV prevention efforts in the criminal legal system: A comprehensive review and recommendations. Current HIV/AIDS Reports,22(1), 33. 10.1007/s11904-025-00737-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joudrey, P. J., Khan, M. R., Wang, E. A., Scheidell, J. D., Edelman, E. J., McInnes, D. K., & Fox, A. D. (2019). A conceptual model for understanding post-release opioid-related overdose risk. Addiction Science & Clinical Practice,14(1), 17. 10.1186/s13722-019-0145-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplowitz, E., Truong, A., Macmadu, A., Berk, J., Martin, H., Burke, C., Rich, J. D., & Brinkley-Rubinstein, L. (2023). Anticipated barriers to sustained engagement in treatment with medications for opioid use disorder after release from incarceration. Journal Of Addiction Medicine,17(1), 54–59. 10.1097/adm.0000000000001029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitch, B. B., & Portela, R. C. (2016). Effective use of naloxone by law enforcement in response to multiple opioid overdoses. Prehospital Emergency Care,20(2), 226–229. 10.3109/10903127.2015.1076097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klemperer, E. M., Wreschnig, L., Crocker, A., King-Mohr, J., Ramniceanu, A., Brooklyn, J. R., Peck, K. R., Rawson, R. A., & Evans, E. A. (2023). The impact of the implementation of medication for opioid use disorder and COVID-19 in a statewide correctional system on treatment engagement, postrelease continuation of care, and overdose. Journal of Substance Use & Addiction Treatment,152, Article 209103. 10.1016/j.josat.2023.209103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knopf, A. (2021). White house releases drug priorities: Focus on harm reduction, treatment and inequities. Alcoholism & Drug Abuse Weekly,33(14), 1–3. 10.1002/adaw.33023 [Google Scholar]

- Krawczyk, N., Buresh, M., Gordon, M. S., Blue, T. R., Fingerhood, M. I., & Agus, D. (2019). Expanding low-threshold buprenorphine to justice-involved individuals through mobile treatment: Addressing a critical care gap. Journal Of Substance Abuse Treatment,103, 1–8. 10.1016/j.jsat.2019.05.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieger, M. S., Yedinak, J. L., Buxton, J. A., Lysyshyn, M., Bernstein, E., Rich, J. D., Green, T. C., Hadland, S. E., & Marshall, B. D. L. (2018). High willingness to use rapid fentanyl test strips among young adults who use drugs. Harm Reduction Journal,15(1), 7. 10.1186/s12954-018-0213-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J. D., Malone, M., McDonald, R., Cheng, A., Vasudevan, K., Tofighi, B., Garment, A., Porter, B., Goldfeld, K. S., Matteo, M., Mangat, J., Katyal, M., Giftos, J., & MacDonald, R. (2021). Comparison of treatment retention of adults with opioid addiction managed with extended-release buprenorphine vs daily sublingual buprenorphine-naloxone at time of release from jail. Jama Network Open, 4(9), 11, Article e2123032. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.23032

- Lim, S., Cherian, T., Katyal, M., Goldfeld, K. S., McDonald, R., Wiewel, E., Khan, M., Krawczyk, N., Braunstein, S., Murphy, S. M., Jalali, A., Jeng, P. J., Rosner, Z., MacDonald, R., & Lee, J. D. (2024). Jail-based medication for opioid use disorder and patterns of reincarceration and acute care use after release: A sequence analysis. Journal of Substance Use & Addiction Treatment,158, Article 209254. 10.1016/j.josat.2023.209254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd, D., Rowe, K., Leung, S. J., Pourtaher, E., & Gelberg, K. (2023). “It’s just another tool on my toolbelt”: New York state law enforcement officer experiences administering naloxone. Harm Reduction Journal,20(1), 29. 10.1186/s12954-023-00748-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowder, E. M., Lawson, S. G., O’Donnell, D., Sightes, E., & Ray, B. R. (2020). Two-year outcomes following naloxone administration by police officers or emergency medical services personnel. Criminology & Public Policy,19(3), 1019–1040. 10.1111/1745-9133.12509 [Google Scholar]

- Macmadu, A., Goedel, W. C., Adams, J. W., Brinkley-Rubinstein, L., Green, T. C., Clarke, J. G., Martin, R. A., Rich, J. D., & Marshall, B. D. L. (2020). Estimating the impact of wide scale uptake of screening and medications for opioid use disorder in US prisons and jails. Drug and Alcohol Dependence,208, Article 107858. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2020.107858 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marlatt, G. A. (1996). Harm reduction: Come as you are. Addictive Behaviors,21(6), 779–788. 10.1016/0306-4603(96)00042-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin, R. A., Alexander-Scott, N., Berk, J., Carpenter, R. W., Kang, A., Hoadley, A., Kaplowitz, E., Hurley, L., Rich, J. D., & Clarke, J. G. (2023). Post-incarceration outcomes of a comprehensive statewide correctional MOUD program: A retrospective cohort study. The Lancet Regional Health,18, Article Article 100419. 10.1016/j.lana.2022.100419 [Google Scholar]

- Martin, R. A., Berk, J., Rich, J. D., Kang, A., Fritsche, J., & Clarke, J. G. (2022). Use of long-acting injectable buprenorphine in the correctional setting. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment,142, Article 108851. 10.1016/j.jsat.2022.108851 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin, R., DaCunha, A., Bailey, A., Joseph, R., & Kane, K. (2025). Evaluating public health vending machine rollout and utilization in criminal-legal settings. Journal of Substance Use & Addiction Treatment,169, Article 209584. 10.1016/j.josat.2024.209584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin, R. A., Gresko, S. A., Brinkley-Rubinstein, L., Stein, L. A. R., & Clarke, J. G. (2019). Post-release treatment uptake among participants of the Rhode Island Department of Corrections comprehensive medication assisted treatment program. Preventive Medicine,128, Article 105766. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2019.105766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto, A., Santelices, C., Evans, E. A., Pivovarova, E., Stopka, T. J., Ferguson, W. J., & Friedmann, P. D. (2022). Jail-based reentry programming to support continued treatment with medications for opioid use disorder: Qualitative perspectives and experiences among jail staff in Massachusetts. International Journal of Drug Policy,109, Article 103823. 10.1016/j.drugpo.2022.103823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matusow, H., Rosenblum, A., & Fong, C. (2021). Online medication assisted treatment education for court professionals: Need, opportunities and challenges. Substance Use & Misuse,56(10), 1439–1447. 10.1080/10826084.2021.1936045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michaud, L., Emily, v. d. M., & and Guta, A. (2024). Therapeutic alignments: examining police and public health/harm reduction partnerships. Policing and Society, 34(4), 290–304. 10.1080/10439463.2023.2263616

- Mitchell, S. G., Willet, J., Monico, L. B., James, A., Rudes, D. S., Viglione, J., Schwartz, R. P., Gordon, M. S., & Friedmann, P. D. (2016). Community correctional agents’ views of medication-assisted treatment: Examining their influence on treatment referrals and community supervision practices. Substance Abuse,37(1), 127–133. 10.1080/08897077.2015.1129389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molfenter, T., Vechinski, J., Kim, J. S., Zhang, J., Meng, L., Tveit, J., Madden, L., & Taxman, F. S. (2025). Assessing the comparative effectiveness of ECHO and coaching implementation strategies in a jail/provider MOUD implementation trial. Implementation Science,20(1), Article 7. 10.1186/s13012-025-01419-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molfenter, T., Vechinski, J., Taxman, F. S., Breno, A. J., Shaw, C. C., & Perez, H. A. (2021). Fostering MOUD use in justice populations: Assessing the comparative effectiveness of two favored implementation strategies to increase MOUD use. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment,128, Article 108370. 10.1016/j.jsat.2021.108370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monnat, S. M. (2022). Demographic and geographic variation in fatal drug overdoses in the United States, 1999–2020. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science,703(1), 50–78. 10.1177/00027162231154348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moustaqim-Barrette, A., Dhillon, D., Ng, J., Sundvick, K., Ali, F., Elton-Marshall, T., Leece, P., Rittenbach, K., Ferguson, M., & Buxton, J. A. (2021). Take-home naloxone programs for suspected opioid overdose in community settings: A scoping umbrella review. BMC Public Health,21(1), 597. 10.1186/s12889-021-10497-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munetz, M. R., & Griffin, P. A. (2006). Use of the sequential intercept model as an approach to decriminalization of people with serious mental illness. Psychiatric Services,57(4), 544–549. 10.1176/ps.2006.57.4.544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nath, J. M., Scharf, B., Stolbach, A., Tang, N., Jenkins, J. L., Margolis, A., & Levy, M. J. (2020). A longitudinal analysis of a law enforcement intranasal naloxone training program. Cureus,12(11), Article e11312. 10.7759/cureus.11312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neeki, M. M., Dong, F., Issagholian, L., MacDowell, S., Cerda, M., Injijian, N., Minezaki, K., Neeki, C. C., Lay, R., Ngo, T., Peace, C., Haga, J., Parikh, R., Borger, R. W., & Tran, L. (2024). Sustainability of treatment programs utilizing medications for opioid use disorders in incarcerated young adults. Journal of Correctional Health Care,30(6), 374–382. 10.1089/jchc.23.02.0009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul, L. (2018). Meeting opioid users where they are: A service referral approach to law enforcement. North Carolina Medical Journal,79(3), 172–173. 10.18043/ncm.79.3.172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payne, E. R., Stancliff, S., Rowe, K., Christie, J. A., & Dailey, M. W. (2024). Comparison of administration of 8-milligram and 4-milligram intranasal naloxone by law enforcement during response to suspected opioid overdose - New York, March 2022-August 2023. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report,73(5), 110–113. 10.15585/mmwr.mm7305a4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrone, D., Malm, A., & Magaña, E. J. (2022). Harm reduction policing: an evaluation of Law Enforcement Assisted Diversion (LEAD) in San Francisco [Article]. Police Quarterly, 25(1), 7–32, Article 10986111211037585. 10.1177/10986111211037585

- Pizzicato, L. N., Drake, R., Domer-Shank, R., Johnson, C. C., & Viner, K. M. (2018). Beyond the walls: Risk factors for overdose mortality following release from the Philadelphia Department of Prisons. Drug and Alcohol Dependence,189, 108–115. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.04.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pourtaher, E., Gelberg, K. H., Fallico, M., Ellendon, N., & Li, S. (2024). Expanding access to medication for opioid use disorder (MOUD) in jails: A comprehensive program evaluation. Journal of Substance Use & Addiction Treatment,161, Article 209248. 10.1016/j.josat.2023.209248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pourtaher, E., Payne, E. R., Fera, N., Rowe, K., Leung, S. J., Stancliff, S., Hammer, M., Vinehout, J., & Dailey, M. W. (2022). Naloxone administration by law enforcement officers in New York State (2015–2020). Harm Reduction Journal,19(1), 102. 10.1186/s12954-022-00682-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purviance, D., Ray, B., Tracy, A., & Southard, E. (2017). Law enforcement attitudes towards naloxone following opioid overdose training. Substance Abuse,38(2), 177–182. 10.1080/08897077.2016.1219439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray, B., Christian, K., Bailey, T., Alton, M., Proctor, A., Haggerty, J., Lowder, E., & Aalsma, M. C. (2023b). Antecedents of fatal overdose in an adult cohort identified through administrative record linkage in Indiana, 2015–2022. Drug and Alcohol Dependence,247, Article 109891. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2023.109891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray, B., Jensen, S., Desjardins, M., Haggerty, J., & Larson, M. (2024). Court navigators and opportunities for disseminating overdose prevention strategies. Health Promotion Practice, , Article 15248399241275623. 10.1177/15248399241275623 [Google Scholar]

- Ray, B., Richardson, N. J., Attaway, P. R., Smiley-McDonald, H. M., Davidson, P., & Kral, A. H. (2023). A national survey of law enforcement post-overdose response efforts. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse,49(2), 199–205. 10.1080/00952990.2023.2169615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed, M., Siegler, A., Tabb, L. P., Momplaisir, F., Krevitz, D., & Lankenau, S. (2021). Changes in overdose knowledge and attitudes in an incarcerated sample of people living with HIV. International Journal of Prison Health,17(4), 560–573. 10.1108/ijph-01-2021-0004 [Google Scholar]

- Rouhani, S., Gudlavalleti, R., Atzmon, D., Park, J. N., Olson, S. P., & Sherman, S. G. (2019). Police attitudes towards pre-booking diversion in Baltimore, Maryland. International Journal of Drug Policy,65, 78–85. 10.1016/j.drugpo.2018.11.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouhani, S., Winiker, A. K., Zhang, L., Sherman, S. G., & Bandara, S. (2024). “What I should be doing is harm reduction, if I’m doing my job right”: Engagement with harm reduction principles among prosecutors enacting drug policy reform in the United States. International Journal of Drug Policy,131, Article 104541. 10.1016/j.drugpo.2024.104541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, D., Ekanayake, D. L., Evans, E., Hayes, E., Senst, T., Friedmann, P. D., McCollister, K. E., & Murphy, S. M. (2025). Cost analysis of MOUD implementation and sustainability in Massachusetts jails. Health Justice,13(1), 9. 10.1186/s40352-025-00321-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAMHSA. (2023). Harm reduction framework. Center for Substance Abuse Prevention, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. https://www.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/harm-reduction-framework.pdf

- Saucier, C. D., Zaller, N., Macmadu, A., & Green, T. C. (2016). An initial evaluation of law enforcement overdose training in Rhode Island. Drug and Alcohol Dependence,162, 211–218. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.03.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seaman, S. R., Brettle, R. P., & Gore, S. M. (1998). Mortality from overdose among injecting drug users recently released from prison: Database linkage study. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.),316(7129), 426–428. 10.1136/bmj.316.7129.426 [Google Scholar]

- Showalter, D., Wenger, L. D., Lambdin, B. H., Wheeler, E., Binswanger, I., & Kral, A. H. (2021). Bridging institutional logics: Implementing naloxone distribution for people exiting jail in three California counties. Social Science & Medicine,285, Article 114293. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sprunger, J., Brown, J., Rubi, S., Papp, J., Lyons, M., & Winhusen, T. J. (2024). Jail-based interventions to reduce risk for opioid-related overdose deaths: Examples of implementation within Ohio counties participating in the HEALing Communities Study. Health Justice,12(1), 48. 10.1186/s40352-024-00307-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staton, M., Webster, J. M., Leukefeld, C., Tillson, M., Marks, K., Oser, C., Bush, H. M., Fanucchi, L., Fallin-Bennett, A., Garner, B. R., McCollister, K., Johnson, S., & Winston, E. (2021). Kentucky women’s justice community opioid innovation network (JCOIN): A type 1 effectiveness-implementation hybrid trial to increase utilization of medications for opioid use disorder among justice-involved women. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment,128, Article 108284. 10.1016/j.jsat.2021.108284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stopka, T. J., Rottapel, R. E., Ferguson, W. J., Pivovarova, E., Toro-Mejias, L. D., Friedmann, P. D., & Evans, E. A. (2022). Medication for opioid use disorder treatment continuity post-release from jail: A qualitative study with community-based treatment providers. International Journal of Drug Policy,110, Article 103803. 10.1016/j.drugpo.2022.103803 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stopka, T. J., Rottapel, R., Friedmann, P. D., Pivovarova, E., & Evans, E. A. (2024). Perceptions of extended-release buprenorphine among people who received medication for opioid use disorder in jail: A qualitative study. Addiction Science & Clinical Practice,19(1), 68. 10.1186/s13722-024-00486-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sucharew, H., & Macaluso, M. (2019). Methods for research evidence synthesis: the scoping review approach. Journal of Hospital Medicine, 14(7), 416–418. 10.12788/jhm.3248

- Tamburello, A., & Martin, T. L. (2024). Dosing and misuse of buprenorphine in the New Jersey Department of Corrections. Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law,52(4), 441–448. 10.29158/jaapl.240071-24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O’Brien, K. K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., Moher, D., Peters, M. D. J., Horsley, T., Weeks, L., Hempel, S., Akl, E. A., Chang, C., McGowan, J., Stewart, L., Hartling, L., Aldcroft, A., Wilson, M. G., Garritty, C., … Godfrey, C. M. (2018). PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine,169(7), 467–473. 10.7326/m18-0850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vechinski, J., Veeramani, D., Bowers, B., & Molfenter, T. (2023). Development and testing of a digital coach extender platform for MOUD uptake. Federal Probation, 87(3), 36–36,42. https://uscourts-d7-dev.agileana.com/federal-probation-journal/2023/12/development-and-testing-digital-coach-extender-platform-moud

- Victor, G., Hedden-Clayton, B., Lenz, D., Attaway, P. R., & Ray, B. (2024). Naloxone vending machines in county jail. Journal of Substance Use & Addiction Treatment,167, Article 209521. 10.1016/j.josat.2024.209521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Victor, G., Roddy, A., Lenz, D., Willis, T., & Kubiak, S. (2023). Applied machine learning analysis: Factors correlated with injection drug use and post-prison medication for opioid use disorder treatment engagement. Journal of Offender Rehabilitation,62(5), 297–314. 10.1080/10509674.2023.2213693 [Google Scholar]

- Vocci, F. J., Schwartz, R. P., Wilson, M. E., Gordon, M. S., Kinlock, T. W., Fitzgerald, T. T., O’Grady, K. E., & Jaffe, J. H. (2015). Buprenorphine dose induction in non-opioid-tolerant pre-release prisoners. Drug and Alcohol Dependence,156, 133–138. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.09.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waddell, E. N., Baker, R., Hartung, D. M., Hildebran, C. J., Nguyen, T., Collins, D. M., Larsen, J. E., & Stack, E. (2020). Reducing overdose after release from incarceration (ROAR): Study protocol for an intervention to reduce risk of fatal and non-fatal opioid overdose among women after release from prison. Health Justice,8(1), 18. 10.1186/s40352-020-00113-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner, K. D., Bovet, L. J., Haynes, B., Joshua, A., & Davidson, P. J. (2016). Training law enforcement to respond to opioid overdose with naloxone: Impact on knowledge, attitudes, and interactions with community members. Drug and Alcohol Dependence,165, 22–28. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.05.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenger, L. D., Showalter, D., Lambdin, B., Leiva, D., Wheeler, E., Davidson, P. J., Coffin, P. O., Binswanger, I. A., & Kral, A. H. (2019). Overdose education and naloxone distribution in the San Francisco County Jail. Journal of Correctional Health Care,25(4), 394–404. 10.1177/1078345819882771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winograd, R. P., Stringfellow, E. J., Phillips, S. K., & Wood, C. A. (2020). Some law enforcement officers’ negative attitudes toward overdose victims are exacerbated following overdose education training. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse,46(5), 577–588. 10.1080/00952990.2020.1793159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]