Abstract

The lack of quantitative methylation reference datasets (ground truth) and cross-laboratory reproducibility assessment hinders clinical translation of epigenome-wide sequencing technologies. Using certified Quartet DNA reference materials, here we generate 108 epigenome-sequencing datasets across three mainstream protocols (whole-genome bisulfite sequencing, enzymatic methyl-seq, and TET-assisted pyridine borane sequencing) with triplicates per sample across laboratories. We observe strand-specific methylation biases across all protocols and libraries. Cross-laboratory reproducibility analyses reveal high quantitative methylation levels agreement (mean Pearson correlation coefficient (PCC) = 0.96) but low detection concordance (mean Jaccard index = 0.36). Using consensus voting, we construct genome-wide quantitative methylation reference datasets serving as ground truth for proficiency testing. Key technical parameters–including mean CpG depth, coverage, and strand consistency–correlate strongly with reference-dependent quality metrics (recall, PCC, and RMSE). Collectively, these resources establish foundational standards for benchmarking emerging epigenomic technologies and analytical pipelines, enabling robust, standardized quality control in research and clinical applications.

Subject terms: Standards, DNA sequencing, Epigenomics, Methylation analysis

Quality control for epigenomic datasets requires robust ground truths. Here, authors generate genome-wide quantitative methylation reference datasets from the publicly available Quartet DNA reference materials, which could serve as a resource for the standardised benchmarking of emerging technologies.

Introduction

Accurate detection of DNA 5-methylcytosine (5mC) is crucial for deciphering epigenetic regulation, discovering novel biomarkers, and realizing precision medicine1–5. Whole-genome bisulfite sequencing (WGBS) has become a fundamental technique for 5mC detection6,7. Other validated protocols include bisulfite-free approaches such as Enzymatic Methyl-Seq (EMseq)8, oxidative bisulfite alternatives like TET-assisted pyridine borane sequencing (TAPS)9, along with Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT)10 and Pacific Biosciences (PacBio)11, further accelerating the breadth and rate of discovery in genome-wide 5mC studies. However, cross-platform inconsistencies in 5mC profiling arise from divergent experimental protocols7,12,13 and analytical pipelines14–16, introducing technical variability, particularly in low-methylation regions17 and repetitive elements18.

Reference materials, which are sufficiently homogeneous and stable with known characteristics, play an indispensable role in assessing various technical biases and errors in both experimental and analytical processes of whole-genome methylation sequencing19–21. Biological reference materials22 such as NA1287823 have been widely used in epigenomic studies to reflect actual signals and variability of current protocols, providing an impartial reference framework for the comparative evaluation of alternative methodologies. Utilizing such reference materials, projects such as the Epigenomics Quality Control (EpiQC)24, the BLUEPRINT Epigenome Project25, and the ENCODE Consortium26 have shown that both experimental13 and analytical15 factors can significantly influence the accuracy of 5mC quantification.

Previous 5mC data24 generated from these materials cannot serve as validated reference datasets (ground truth) for quantitative genome-wide methylation measurement due to limited scale in dataset types or insufficient sequencing depth. The lack of ground truth of prior studies resulted in suboptimal evaluation strategies, such as converting quantitative methylation levels into binary classifications (e.g., retaining sites with only 0% or 100% methylation) or comparing to a ‘ground truth’ data set that was generated using one of the protocols or tools27. These approaches inherently limit the ability to assess the performance for detecting subtle but critical features28, impeding the verification of the accuracy of specific measurements and the development of new measurement methods. In addition, previous studies have prioritized cross-protocol comparisons, often overlooking critical aspects such as intra-protocol technical reproducibility across labs and strand-specific consistency among technical replicates within individual labs, which are essential to estimating the overall measurement reproducibility.

As part of the ongoing efforts of the Chinese Quartet (中华家系1号) Project29,30 that developed the first suites of multi-omics reference materials with matched reference datasets for genomics31, transcriptomics32, proteomics33, and metabolomics34 (ground truth) from four B-lymphoblastoid cell lines of monozygotic twin family members (father, mother, and twin daughters), here we perform a multi-lab and multi-protocol methylation sequencing study using the Quartet DNA reference materials. Based on the high-quality methylation quantification datasets, we establish quantitative genome-wide methylation reference datasets via consensus voting. The Quartet DNA reference materials and the defined methylation reference datasets provide a ground truth for benchmarking epigenomic profiling technologies and analytical pipelines.

Results

Study design

The Quartet DNA reference materials are composed of genomic DNA (gDNA) extracted from four immortalized lymphoblastoid cell lines derived from a Chinese Quartet family, including father (F7), mother (M8), and monozygotic twin daughters (D5 and D6) (Fig. 1A). These materials have been certified as the First Class of National Reference Materials by China’s State Administration for Market Regulation and are extensively used for proficiency testing and method validation.

Fig. 1. Study design.

A Overview of the study design. Briefly, we generate multi-batches DNA methylation datasets based on DNA reference materials of the Chinese Quartet with father (F7), mother (M8), and monozygotic twin daughters (D5 and D6). We constructed genome-wide CpG methylation reference datasets and evaluated corresponding quality metrics. B Schematic overview of methylome sequencing datasets generation for construct reference datasets. Three replicates for each Quartet DNA reference material were sequenced in nine batches by Whole-Genome Bisulfite Sequencing (WGBS), Enzymatic Methyl-Seq (EMseq), and Ten-eleven translocation-assisted pyridine borane sequencing (TAPS) protocols on three sequencing platforms at five labs, resulting in 108 libraries. Each library used two pipelines to call 5mC quantification, resulting in 216 CpG calling datasets. Created in BioRender. Xi, H. (https://BioRender.com/fbst4bu).

To measure the CpG methylation profiles in an unbiased and quantitative way, we sequenced three replicates for each of the four Quartet DNA reference materials using three commercially available short-read sequencing protocols, including WGBS, EMseq, and TAPS, generating nine data batches (Fig. 1B). Twelve libraries were sequenced with over 30× in each batch, and 108 libraries (9 batches × 12 libraries/batch) were sequenced across all nine batches. Importantly, the library construction and sequencing experiments for each batch were conducted simultaneously to ensure consistency and minimize technical variability.

A total of 216 CpG methylation call sets were generated from the 108 sequencing datasets for each Quartet reference material, using two widely used best-practice pipelines for each protocol, i.e., Bismark and BWA-meth for WGBS and EMseq; BWA-MEME and BWA-MEM2 for TAPS (Supplementary Fig. 1). We used high-quality call sets to construct the reference datasets at single-cytosine levels based on rigorous quality control and consensus voting. The robustness and accuracy of the reference datasets were determined by sensitivity analysis and orthogonal validation by Illumina Infinium Methylation EPIC (850 K) arrays. Moreover, we also developed reference datasets-independent and -dependent quality metrics for performance evaluation of epigenomic sequencing, including quantitative methylation call sets from long-read DNA sequencing. Correlations between the two types of metrics were analyzed to reveal sources of performance variation.

Strand biases existed in each library across all protocols

Strand consistency is a robust metric for assessing intra-replicate reproducibility. Using this metric, we identified a strong dependence on cytosine depth (at CpG context), which influences both qualitative and quantitative concordance between complementary strands. We maintained full sequencing depth (≥ 90 G/library; Supplementary Table 1) and analyzed the methylation consistency between complementary strands across nine independent batches to optimize reproducibility in reference dataset construction.

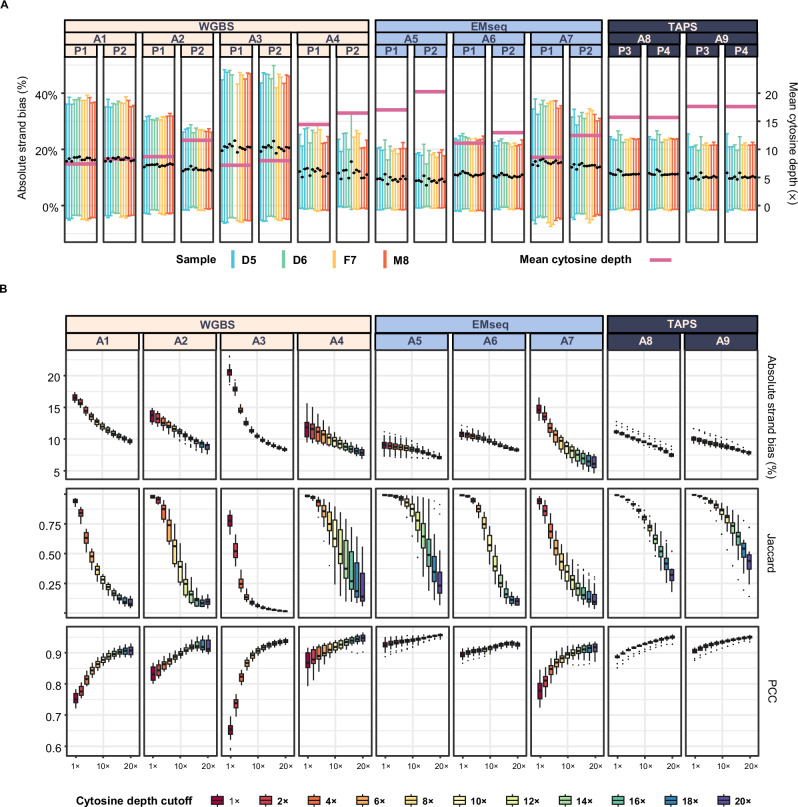

Strand bias analysis at CpG sites demonstrated depth-dependent measurement precision. Batches with higher cytosine sequencing depths exhibited reduced mean methylation deviations, typically within a 10–20% mean absolute deviation range (excluding outlier batch A3; Fig. 2A). Based on previous findings that sequencing depths beyond 10 × gain minimal benefit35, we selected 10× as a detection threshold for cytosines, with extended depth profiling (1−20×) supporting this inflection point (Supplementary Fig. 2). Depth threshold analysis (1−20×) further resolved depth-mediated consistency patterns. We use the Jaccard index to quantify site detection consistency, which is defined as the fraction of sites jointly detected in both the compared datasets. In contrast, the Pearson Correlation Coefficient (PCC) quantifies the agreement of methylation level at shared sites. Increasing the sequencing depth threshold for CpG site detection reduced qualitative concordance (Jaccard index), but it improved quantitative agreement (Pearson Correlation Coefficient (PCC) ≥ 0.9, excluding outlier batch A1 at 10×). This trade-off demonstrates the critical role of cytosine depth thresholds in ensuring methylation measurement reliability (Fig. 2B; Supplementary Fig. 3).

Fig. 2. Strand bias existed in each library across all protocols.

A Absolute methylation deviation between the positive and negative strands of all detected CpG sites across nine different batches. The Y-axis (left) represents the absolute deviation of methylation quantification. Each point or error bar represents one library. Error bars indicate the range of methylation deviation within each library, with colors denoting different sample types. The Y-axis (right) represents the average sequencing depth of cytosines for each batch with pink horizontal lines. The black dots indicate the average deviation within each batch. B Comparison of the qualitative and quantitative consistency between the positive and negative strands at different sequencing depths across nine batches. Each box summarizes 24 call sets within a batch (12 libraries × 2 pipelines); each call set contributes one value. Center line = median; box = interquartile range (Q1–Q3); whiskers extend to the largest and smallest non-outlying values (± 1.5 × IQR); points denote outliers. Technical replicates are libraries (n = 3); biological replicates are samples (n = 4). The box colors indicate the minimum sequencing depth threshold from 1× to 20×. The y-axis panels display (from top to bottom) the absolute strand bias (%), Jaccard index, and Pearson correlation coefficient (PCC) of cytosines methylation levels between strands. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Notably, all replicates exhibited substantial inter-strand methylation differences (absolute delta methylation ≥ 10% at 1×) across protocols (Fig. 2B), indicating that strand bias is a consistent technical variation when quantification is not filtered by detection coverage24. In addition, while all nine batches exhibited characteristic bimodal methylation distributions, WGBS data showed enrichment at extreme methylation values (0% and 100%) compared to enzymatic methods (Supplementary Fig. 4).

High variability among technical replicates across all protocols

Reference-independent metrics reveal quantifiable cross-replicate reproducibility, with variations influenced by technical noise. Signal-to-noise ratio (SNR)29,32, as a reference-independent metric, quantifies the ability to distinguish true biological differences between distinct biological groups (signal) from technical replicates within the same group (noise), with higher values reflecting better reproducibility and discriminability at the batch level. The Quartet multi-sample design enabled a systematic evaluation of biological signal resolution through SNR analysis. Maintaining single-base resolution methylation profiles enhanced sample discrimination, with eight out of nine batches showing clear separation of biological replicates (Supplementary Fig. 5). We noticed that the two LCLs derived from the monozygotic twin daughters (D5 and D6) exhibited consistently large differences in the PC1 space across eight out of nine batches, although one might expect the methylation profiles of identical twins to show the highest similarity among all six pairs of the Quartet sample groups (e.g. F7 vs. D6, M8 vs D6, etc.). This twin-specific separation was already observed in our earlier transcriptomic analyses32, and is now recapitulated in the methylome, indicating that the divergence reflects a genuine biological signal rather than technical noise. The consistency of these observations across both transcriptome and methylome studies further supports the stability and utility of the Quartet reference materials for investigating biological variation across multi-omics layers.

Using an SNR cutoff of 22.4 (mean − s.d. across 9 batches), batch A4 was identified as substandard (SNR = 18.9), with PCA confirming its limited sample discriminability compared with other batches (Fig. 3A). Following strand-discordant site exclusion (absolute strand bias ≤ 20%)36,37, we assessed cross-batch reproducibility using median absolute deviation (MAD)-filtered6 CpG sites (MAD < 5%) at ≥ 20× CpG depth. This stringent filtering retained 75% of high-confidence strand-concordant CpG sites across all nine batches (Fig. 3B). Technical reproducibility assessment revealed distinct patterns between qualitative detection consistency and quantitative measurement precision. Notably, while the Jaccard index quantifies the proportion of CpG sites jointly detected above the 20× cutoff, PCC evaluates methylation concordance specifically at these shared high-coverage (above 20×) CpG sites. While the Jaccard index exhibited substantial variability across batches (Jaccard range: 0.58 – 0.82) at the 20× CpG depth, genome-wide methylation levels showed exceptional quantitative agreement with PCC, consistently averaging 0.96 for within-sample replicates (Fig. 3C, D; and Supplementary Fig. 6). Furthermore, cross-biological replicate reproducibility analyses revealed that qualitative concordance was predominantly affected by batch, whereas quantitative consistency was influenced by biological variation, in line with theoretical expectations (Supplementary Fig. 7). This divergence reveals that while batch effects substantially impact CpG detection completeness, they minimally affect quantitative precision at consistently detected sites. This justifies our reference construction focus on cross-batch consensus sites to ensure measurement reliability in downstream applications.

Fig. 3. Reference-independent metrics reveal inter-replicate reproducibility variations.

A Signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) based on the Quartet multi-sample design (determined as the ratio of the average distance among different samples to the average distance among technical replicates in the PCA plot). Dots represent SNR values calculated by excluding one of the 12 libraries in each batch. The red horizontal dashed line (y = 22.4) represents the mean minus SD of nine SNR values. B The mean absolute deviation (MAD) distribution of methylation quantification for the same sample (three technical replicates analyzed by two pipelines) was examined across nine batches. The concordant CpGs (≥ 20×) were retained, which corresponds to a depth of 10× for cytosine. C Heatmap of the Jaccard index matrix between any two technical replicates of D6 (as an example). D The Pearson correlation coefficient matrix for any two technical replicates of D6 was shown as an example. Only the concordant CpGs (≥ 20×) were retained. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Construction of genome-wide methylation quantification reference datasets

Analysis of CpG coverage across nine batches (A1-A9) justified the selection of six batches (excluding A1/A3/A4 for low Jaccard index or SNR) to build the reference datasets (Supplementary Fig. 8), achieving reduced variability and 70% genome-wide CpG coverage. A multi-tiered consensus workflow integrated 36 datasets per Quartet sample (3 replicates × 2 pipelines × 6 batches), with single-cytosine filtering (≥ 10× coverage), intra-batch consensus (≥ 4/6 replicates, MAD < 10%37), and inter-batch consensus (≥ 4/6 batches) (Fig. 4A).

Fig. 4. Construction of genome-wide methylation quantification reference datasets.

A Workflow for constructing Quartet DNA methylation reference datasets. Reference datasets were constructed according to the following steps: (1) identifying concordant and discordant CpG sites between positive and negative strands; (2) identifying intra-batch qualification consistent CpGs; (3) identifying inter-batch quantification consistent CpGs; (4) calculating arithmetic mean methylation levels based on reliable cytosines that were identified consensus; (5) annotating CpG sites by combining cytosine methylation levels and genomic context. Created in BioRender. Xi, H. (https://BioRender.com/fbst4bu) B Distribution of four types of CpG across different samples. The X-axis represents samples, and the Y-axis shows the percentage of each CpG type as a proportion of the total genomic CpG sites. Colors differentiate the four CpG types. C Methylation quantification distributions for concordant CpG sites (per-CpG quantification) and the other three CpG types (per-cytosine quantification). The X-axis indicates methylation quantification values (0% to 100%), and the Y-axis shows the frequency of CpG/cytosine sites at each quantification value. D Genome-wide coverage distribution across genomic contexts. From left to right: (1) chromosomes 1 to 22 and X, (2) genic features, and (3) CGI contexts. Each facet contains a box plot representing the percentage of genome coverage for the reference datasets. Within each facet, the line plot shows the proportion of each feature within the genome. The sum of the features in each facet adds up to 100%, indicating their relative genomic coverage in the respective category. Each box contains four values (D5, D6, F7, M8), and the plotted points correspond to the four samples. Center line = median; box = interquartile range (Q1–Q3). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

We implemented a complementary annotation pipeline to identify strand-concordant CpG sites within the reference datasets. Starting with pre-merged duplex data (absolute strand bias ≤ 20%), we applied an identical consensus framework to define high-confidence strand-concordant CpG sites (Supplementary Fig. 9). On average, 24% of reference CpG sites contained information for both strands and met the concordant criteria. Researchers may optionally use this strand-concordant dataset (10% larger than base reference datasets, r = 0.999 with the base) when prioritizing maximal CpG sites, although it excludes single-strand resolution data critical for asymmetry analysis. Rigorous quality control ensured that more than 90% of CpG sites had measurement uncertainty below 15%, with over 80% achieving credibility scores above 85% (Tables 1, 2).

Table 1.

The credibility of reference datasets

| Credibility | D5 number percentage | D6 number percentage | F7 number percentage | M8 number percentage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 85%- 100% |

15,257,724 76.23% |

18,027,256 81.65% |

17,409,609 86.42% |

16,470,464 83.46% |

| 70% − 85% |

4,752,334 23.74% |

4,046,333 18.33% |

2,734,326 13.57% |

3,260,509 16.52% |

| 65% − 70% |

5329 0.03% |

4706 0.02% |

1302 0.01% |

2844 0.01% |

| Total |

20,015,387 100.00% |

22,078,295 100.00% |

20,145,237 100.00% |

19,733,817 100.00% |

Table 2.

The characterization uncertainty uchar of reference datasets

| Uchar | D5 number percentage | D6 number percentage | F7 number percentage | M8 number percentage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0−15% |

18,412,461 91.99% |

20,575,018 93.19% |

18,856,245 93.60% |

18,378,983 93.13% |

| 15−30% |

1,112,392 5.56% |

955,991 4.33% |

843,105 4.19% |

915,312 4.64% |

| 30−55% |

490,354 2.45% |

547,286 2.48% |

445,887 2.21% |

439,522 2.23% |

| Total |

20,015,387 100.00% |

22,078,295 100.00% |

20,145,237 100.00% |

19,733,817 100.00% |

Following reference construction, we systematically profiled the methylation patterns of four CpG classes: positive strand-only, negative strand-only, concordant, and discordant CpG sites. Concordant CpG sites constituted the predominant class (30% of genome-wide CpG sites), with the remaining categories exhibiting comparable proportions (23–24% across samples; Fig. 4B). The concordant CpG sites exhibited a pronounced bimodal (0% and 100%) methylation distribution, suggesting stable epigenetic regulation (Fig. 4C). On the other hand, strand-specific and discordant CpG sites exhibit more evenly distribution at per-cytosine, suggesting greater dynamic potential in methylation states where strand-specific resolution provides critical biological insights.

Systematic evaluation across genomic contexts revealed distinct coverage patterns in the reference datasets (Fig. 4D). Most strikingly, CpG island (CGI) contexts exhibited both the lowest coverage (30.76% - 56.73% across samples) and the most significant inter-sample variability (IQR:12.90%), contrasting sharply with the high recovery rates and low variability observed in CpG shores (Median: 68.29%, IQR:6.92%), shelves (Median: 72.89%, IQR:5.63%), and open seas (Median: 72.74%, IQR:1.86%). Chromosomal coverage was uniform (Median = 71.50%, IQR = 4.25%), indicating minimal batch-specific biases. Analysis of genic features38 revealed that intron regions exhibited high coverage (Median: 75.10%), promoter and 5’ UTR regions showed reduced representation (Median: 59.07% and 47.47%, respectively), likely due to GC-rich technical challenges. Although genomic context-dependent coverage biases exist, the standardized pipeline ensures uniform quality control and consistent stringency across all regions, enabling context-agnostic accuracy evaluation.

Using the strand-specific, absolute quantitative methylation data we generated, we demonstrated how researchers can derive differential methylation profiles tailored to their study objectives through straightforward data processing. Specifically, we applied a filtering strategy that excludes discordant CpG sites (with strand differences ≥ 20%), merged concordant sites from both strands, and treated strand-only sites as concordant for differential methylation CpG analysis. Setting a threshold of Δ methylation% ≥ 20%, we observed that the number of DMCs was highest between D5 and F7 and lowest between D6 and M8, consistent with the PCA results (Supplementary Fig. 10). Due to differential B cell subtype selection and cell culture effects, the largest differences were not necessarily between parents, nor were the smallest differences always between the monozygotic twins—a pattern also consistent with our previous transcriptomic findings. This example highlights not only the biological consistency of the Quartet reference materials across omics layers but also their value for cross-omics benchmarking and biological studies.

Robustness and reliability of reference datasets by sensitivity analysis and orthogonal validation

To evaluate the sensitivity of the reference datasets, we employed a systematic exclusion approach by iteratively excluding subsets of the input datasets using two distinct strategies: (1) complete batch removal, in which entire batches were excluded across six scenarios, and (2) single library removal per batch, where one library was removed at a time within each batch, resulting in 18 scenarios. In all 24 perturbed reference datasets, CpG site coverage remained comparable to the original reference (Mean = 14.66 million CpG sites vs. the original 13.21 million CpG sites; IQR = 1.68 million), and quantitative agreement with the primary reference was consistently high (Minimum PCC = 0.9996, Mean RMSE = 0.76; Supplementary Table 2). The high Jaccard index (Mean: 0.85) between perturbed and original references indicated substantial overlap in the reference CpG sites. Furthermore, minor coverage variations observed were attributed to context-dependent technical variability rather than systematic biases.

To validate the technical accuracy of the reference datasets, we performed orthogonal verification using 850 K arrays across three experimental batches (four samples, each with three technical replicates; Supplementary Fig. 11A). About 470,830 CpG sites in the reference datasets for each sample were validated by 850 K (Supplementary Fig. 11B) and 82.38% of them were within the ± 3 standard deviations (SD) of the reference beta values. Across all samples, the PCC was no smaller than 0.99 and the RMSE was no greater than 7.34 (Supplementary Table 3).

Performance assessment based on reference datasets across protocols

We conducted a performance assessment using the reference-dependent metrics across 11 sequencing batches: six batches from reference datasets construction, three independent WGBS batches (A1, A3, and A4), and two long-read batches (ONT and PacBio). Harmonized criteria were applied: strand-concordant CpGs were utilized for short-read data (strand bias ≤20%), while forced duplex concordance was assumed for long-read data (i.e., methylation calls were averaged across both DNA strands). Although ONT enables strand-specific methylation resolution, we standardized duplex assumptions for both ONT and PacBio to ensure cross-platform comparability. Each batch was evaluated using three metrics: Recall (qualitative), PCC, and RMSE (quantitative).

Long-read protocols achieved near-perfect recall (Min = 0.99) by retaining all strand-concordant CpG sites without pre-filtering, whereas short-read protocols showed lower recall (Mean range: 0.76–0.97) due to stringent removal of strand-discordance CpGs during preprocessing (Fig. 5A). However, long-read protocols demonstrated compromised methylation quantification accuracy (PCC, and RMSE) compared to short-reads protocols (Fig. 5B, C). This divergence highlights a critical trade-off: long-read protocols maximize CpG inclusiveness at the cost of potential noise retention, whereas short-read protocols prioritize analytical precision through aggressive discordance filtering. Although all batches exhibited strong high quantitative agreement with reference methylation levels (PCC > 0.95; Fig. 5B), substantial technical variability was observed within methodologies. For example, WGBS batches displayed obvious differences in measurement precision (Mean RMSE range: 5.74–8.92; Fig. 5C) despite using identical protocols, suggesting operator-dependent variability in library preparation or data analysis. These results highlight the need for standardized benchmarking to minimize technical biases.

Fig. 5. Performance assessment based on reference datasets across protocols.

Performance evaluation across 11 batches using reference-dependent metrics: A, Recall; B, Pearson Correlation Coefficient (PCC); and C, Root Mean Square Error (RMSE). W- WGBS, E- EMseq, T- TAPS, O- ONT, P- PacBio. For WGBS (W), EMseq (E), and TAPS (T), each box summarizes 24 values per batch (12 libraries × 2 pipelines); for ONT (O) and PacBio (P), each box summarizes 8 values per batch (4 libraries × 2 pipelines), with one value per call set. Center line = median; box = interquartile range (Q1–Q3). All metrics were assessed at single-CpG resolution, with short-read analyses restricted to strand-concordant sites (inter-strand methylation difference ≤ 20%), while long-read data inherently merged both strands into duplex CpG calls due to the inability of PacBio to resolve strand-specific methylation. Evaluation of three reference-dependent metrics (Recall, PCC, and RMSE) under (D) CGI (CpG islands) vs. non-CGI regions and (E) enhancer vs. promoter regions, with distributions represented as box plots across 11 batches. Center line = median; box = interquartile range (Q1–Q3); whiskers extend to the largest and smallest non-outlying values (± 1.5 × IQR); points denote outliers. Significance between region groups was assessed by Two-sided Wilcoxon tests (ns: p ≥ 0.05; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

When stratifying by CpG island (CGI) versus non-CGI contexts, reference-dependent metrics revealed distinct technical patterns across all 11 batches. Recall and RMSE consistently demonstrated statistically significant differences between regions in every batch (Wilcoxon test, p < 0.05), with CGI regions exhibiting superior detection rates (higher Recall) and enhanced quantitative precision (lower RMSE) (Fig. 5D). In contrast, PCC showed significant batch-dependent variability—displaying non-significant differences in only two batches—attributable to its sensitivity to distributional characteristics of methylation data, wherein CGI and non-CGI regions manifest fundamentally distinct quantitative profiles. This metric-specific inconsistency underscores the recommendation to prioritize Recall and RMSE for robust quality assessment.

Comparative analysis of enhancer versus promoter regions—biologically pivotal regulatory elements—revealed more complex technical behavior (Fig. 5E). Significant Recall differences emerged in 7 of 11 batches, while RMSE variations occurred in 7 different batches. Notably, PCC and RMSE showed concordant directional trends (high PCC with low RMSE) in the majority of batches, demonstrating consistent quantitative reliability across these functionally distinct elements despite underlying biological heterogeneity. Collectively, these context-stratified analyses validate our reference materials’ capacity to detect nuanced, region-specific technical biases—a critical prerequisite for developing precision epigenomic workflows.

Besides, cross-batch performance varied across genomic regions. When stratified by four CpG island (CGI) contexts (e.g., shores, shelves), A5, A6, and A9 maintained top ALL scores (Supplementary Fig. 12A). Notably, high-ranking batches showed consistent performance across regions (ΔALL < 0.1), whereas low-ranking batches exhibited context-specific biases. For example, batch A3 (WGBS) performed well in open seas (ALL = 0.52) but poorly in GC-rich CpG islands (ALL = 0.28), likely due to WGBS limitations in high-GC regions39. Similarly, in eight groups of genic features (e.g., promoters, exons), batches A5, A9, and A6 ranked highest in composite ALL scores (range: 0 to 1), calculated as the mean of normalized Recall, PCC, and inverted RMSE values, with identical rankings for PCC and RMSE (Supplementary Fig. 12B). Long-read batches A10 and A11 outperformed others in recall, as their unfiltered retention of strand-discordant CpGs maximized site recovery—a key advantage over short-read protocols that discarded 20 – 30% of CpGs during preprocessing.

Using reference-dependent metrics, we compared two distinct analysis pipelines across 11 experimental batches. In over half of the batches, both pipelines showed no significant differences (Wilcoxon test) in performance metrics (Supplementary Fig. 13). However, for WGBS and EM-seq data, Pipeline P2 outperformed P1 with higher Recall and PCC alongside lower RMSE (Batch A2 and A7). For TAPS, ONT, and PacBio data, pipelines exhibited minimal differences, potentially due to TAPS pipeline similarity and smaller batch sizes in ONT/PacBio (4 libraries per batch versus 12 in others). This pilot test demonstrates our reference datasets’ utility as ground-truth for evaluating analysis pipelines or library performance, enabling field-wide methodological calibration and improvement.

Correlation analysis between reference-independent and reference-dependent metrics

Performance evaluation metrics can be categorized into reference-independent and reference-dependent types, with the former further divided into three groups assessing library quality, sequencing quality, and reproducibility. Unsupervised clustering of 21 evaluation metrics across nine short-read sequencing batches revealed distinct technical performance patterns (Fig. 6A). Reference-dependent accuracy metrics (e.g., PCC, RMSE) formed a cohesive cluster, indicating their shared capacity to evaluate biological fidelity. Notably, the SNR co-clustered with experimental process indicators (GC%, Q30%, spike-in conversion rates), suggesting its potential utility as a composite reference-independent metric reflecting both technical reproducibility and systematic biases in methylation experiment workflows. The co-clustering of CHH methylation levels with technical reproducibility metrics, such as the Jaccard index and PCC between technical replicates, indicates that stochastic base conversion inefficiencies similarly impact both non-CpG methylation calls and replicate concordance.

Fig. 6. Correlation analysis between reference-independent and reference-dependent quality metrics.

A Clustering heatmap of quality control metrics across nine batches of sequencing data. The clustering method used is Euclidean distance. B Mantel test for correlation between quality control metrics. The plot displays the results of a Mantel test comparing three accuracy metrics—Recall, PCC, and RMSE—across different quality control metrics. The figure shows a lower triangular correlation matrix, where the PCC (r) is represented by a color gradient ranging from red (negative correlation) to blue (positive correlation), with the intensity of the color indicating the strength of the correlation. Statistical significance is indicated by a marker above each correlation, with different levels of significance represented by size and color: p < 0.01 is marked in dark red, 0.01 ≤ p < 0.05 in green, and p ≥ 0.05 in gray. The Mantel’s r value, representing the strength of the correlation, is visualized by the size of the coupling lines between the variables, with more extensive lines corresponding to stronger correlations. The Mantel’s p-values are represented by color, where smaller p values are shown in blue, intermediate p values in green, and non-significant results in gray. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

The clustering analysis revealed that technical variability across labs exerted a stronger influence on data than protocol. This divergence underscores the necessity of providing labs with ground truth, which would empower systematic self-calibration to identify and mitigate systematic technical biases, ultimately enhancing cross-lab reproducibility in methylation profiling workflows.

An integrative analysis of reference-independent and reference-dependent metrics identified key determinants of methylation profiling performance (Fig. 6B). Coverage breadth (≥ 1× depth) and strand concordance rates were universal predictors of accuracy (Recall, PCC, and RMSE), with sequencing depth further influencing quantitative precision. Notably, technical reproducibility metrics (Jaccard and PCC between technical replicates) correlated more strongly with accuracy than conventional process controls (e.g., spike-in conversion rates), which showed no significant correlations despite their common use as quality indicators. SNR uniquely predicted intra-batch discriminability—a dimension orthogonal to conventional accuracy measures—suggesting its complementary role in detecting systematic technical biases (e.g., batch effects) rather than random measurement errors.

This multidimensional analysis demonstrates that the reference datasets facilitate the simultaneous evaluation of three key aspects: biological accuracy (e.g., reference-dependent metrics), technical precision (e.g., reproducibility), and experimental quality (e.g., library or sequencing quality). The integrated interpretation of these metrics is crucial for identifying multifaceted quality control failures in methylation profiling workflows, such as operator errors or protocol deviations. The Quartet Data Portal40 (QDP) is being upgraded with methylation benchmarking modules to operationalize this framework.

Discussion

The Quartet DNA methylation reference datasets represent a major advancement in epigenomic research, providing a robust benchmark for standardization and evaluation of DNA methylation analyses. By integrating data from three widely used short-read sequencing protocols (WGBS, EMseq, and TAPS), these datasets deliver exceptional coverage and accuracy, addressing the inconsistencies common in current methylation profiling methods. Compared with existing resources such as EpiQC and BLUEPRINT, the Quartet datasets significantly extend the scope by including a broader range of CpG sites and leveraging certified DNA reference materials derived from a monozygotic twin family. This establishes a genome-wide, single-base resolution methylation reference for quantitative benchmarking, enhancing measurement reliability and enabling precise cross-platform comparisons, which are critical for harmonizing heterogeneous methylation data.

Our systematic analyses identified strand consistency and mean CpG depth—not bisulfite conversion rate—as the primary determinants of methylation accuracy. As the detection cutoff for cytosine in CpG context increases, the number of cytosines detected on both strands decreases, and the absolute strand bias at these intersecting sites becomes smaller. We found that a minimum CpG depth of 20× (10× per cytosine) optimally balanced strand-specific qualitative consistency and quantitative precision (Fig. 2B; and Supplementary Fig. 3), outperforming the commonly used conversion rate thresholds (e.g., > 99%; Fig. 6B). These findings challenge conventional benchmarks and advocate for depth-driven accuracy, encouraging labs to prioritize sequencing depth over excessive conversion controls.

We observed substantial intra-protocol variability across labs, with inter-lab discrepancies surpassing those between different protocols. Technical replicates within labs showed low reproducibility (Jaccard index, Supplementary Fig. 4), while inter-lab replicates under the same protocol diverged significantly in both qualitative (Recall, Fig. 5A) and quantitative (PCC and RMSE, Fig. 5B, C) metrics. This highlights lab-specific variability as a major reproducibility barrier in WGBS and underscores the need for standardized workflows across platforms.

By incorporating established SNV reference datasets from the Quartet multi-omics framework, we eliminated methylation false positives caused by underlying genetic variants (Methods), demonstrating the power of orthogonal validation across omics layers. This methylation reference dataset now complements existing genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolomic reference datasets, and supports multi-omics interpretation, such as distinguishing DNA methylation-mediated gene silencing from other regulatory mechanisms, and evaluating multi-omics integration or causal inference analyses.

Despite its strengths, the current reference has limitations. First, the workflow for constructing the reference datasets using consensus voting struggles to balance accuracy and comprehensiveness, resulting in fewer difficult-to-sequence areas being covered. Second, B-lymphoblastoid cell line methylation profiles may not fully reflect tissues with dynamic epigenetic regulation (e.g., cancer or embryo). Third, like most bisulfide-based methods, our datasets do not differentiate 5hmC from 5mC, limiting the ability to resolve dynamic methylation states. Emerging techniques such as oxidative bisulfite sequencing41,42 (oxBS-Seq), or TET-assisted bisulfite sequencing43 (TAB-seq) may help resolve this in future updates.

Future improvement directions include integrating long-read sequencing data to expand CpG coverage in reference datasets, especially in low-methylation and repetitive regions. Long-read techniques enable base-resolution detection of methylation subtypes, such as 5hmC and 5mC44. Moreover, we aim to develop reference datasets from diverse biological sources to enhance generalizability and to expand orthogonal validation to include pyrosequencing and mass spectrometry, both of have shown high concordance with array-based quantification in previous studies25.

Our current framework lays critical infrastructure for harmonizing epigenomic data across platforms and laboratories. To facilitate broad adoption, we will make the Quartet methylation reference datasets and quality control metrics publicly available at (https://docs.chinese-quartet.org). Upon completion, these resources will also be integrated into QDP40 for real-time quality monitoring and cross-platform benchmarking of 5mC workflows. Researchers can leverage these resources to benchmark new sequencing technologies, optimize analytical pipelines, and implement standardized quality metrics. By fostering a standardized approach to data quality assessment, this study could lead to improvements in precision epigenomics, where robust and reproducible results could help to drive fundamental discoveries and translational advancements.

Methods

DNA reference materials

The samples in this study comprise genomic DNA (gDNA) from four EBV-immortalized B-lymphoblastoid cell lines designated as standard materials31 by Fudan University and the National Institute of Metrology (NIM) of China. DNA reference materials were from GBW09900- GBW09903 (2022/08/22). The D5/D6/F7/M8 cell lines were provided by a Chinese monozygotic twins/father/mother quartet. Quartet DNA reference materials can be requested from the Quartet Data Portal (https://chinese-quartet.org/) or through the National Sharing Platform for Reference Materials (https://www.ncrm.org.cn/Web/Home/EnglishIndex) under the Administrative Regulations of the People’s Republic of China on Human Genetic Resources.

Library preparation and whole-genome sequencing

Each batch comprised four Quartet reference materials (D5/D6/F7/M8), with triplicate libraries per sample type (12 libraries total per batch). This design ensures robustness and minimizes batch effects during sequencing.

Whole-genome sequencing data for the Quartet DNA reference materials were generated across six certified labs using five complementary technologies: whole-genome bisulfite sequencing (WGBS), enzymatic methyl-seq (EMseq), TET-assisted pyridine borane sequencing (TAPS), Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT), and PacBio HiFi. All short-read libraries (WGBS, EMseq, and TAPS) were prepared with PCR-based kits and sequenced to ~30× genome-wide coverage on Illumina NovaSeq6000 and MGI platforms (MGISEQ-2000 and T7), while long-read libraries (ONT and PacBio) utilized native DNA without fragmentation.

For WGBS, triplicate libraries per Quartet sample (12 libraries per batch) were sequenced across four labs: MGISEQ-2000 at MGI Tech Co., Ltd. (MGI Lab; batch A4) and NovaSeq 6000 at Annoroad Gene Technology (Beijing) Co., Ltd. (ANO; A1), Novogene Co., Ltd. (NVG; A2), and Burning Rock Biotech Ltd. (BNR; A3). Bisulfite conversion used Zymo EZ Methylation Direct MagPrep Kit for A1–A4; all libraries included unmethylated lambda DNA as the conversion control.

For EM-seq, libraries were prepared and sequenced on MGI T7 at Novogene Co., Ltd. (NVG; A7) using the NEBNext Enzymatic Methyl-seq Kit, and on NovaSeq 6000 at Burning Rock Biotech Ltd. (BNR; A5, A6) using Vazyme EpiArt DNA Enzymatic Methylation Kit. Libraries in A6 and A7 included unmethylated lambda DNA as the conversion control.

For TAPS, libraries were processed on the MGI T7 platform at Geneplus Technology Co., Ltd. (GNP; A8, A9), and the Methylated & Non-Methylated pUC19 DNA Set (Zymo Research, D5017; 20 µL) was used as conversion controls.

This integrated design produced 28 libraries spanning three technical replicates per sample for short-read technologies (12 WGBS, 9 EMseq, and 6 TAPS) and a single replicate for long-read platforms (1 ONT and 1 PacBio).

850 K orthogonal technologies

As described in our previous study29, bisulfite conversion was performed using the Zymo EZ DNA Methylation-Gold Kit (https://www.illumina.com/products/by-type/microarray-kits/infinium-methylation-epic.html) with 500 ng of DNA per sample. The bisulfite-converted DNA was eluted in 15 μL according to the manufacturer’s protocol, evaporated to a volume of < 4 μL, and used for methylation analysis on the 850 K according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Illumina).

Microarray experiments were run at two labs, denoted labs SNT and ENG, to distinguish them from the sequencing labs (lab 1 and lab 2). The resulting dataset contains nine replicates per sample and 36 libraries in total. Three technical replicates were generated for each sample at lab ENG, and six replicates from each sample were generated at lab SNT.

Data analysis

For WGBS and EM-seq, all the raw paired fastq files were processed in parallel through two pipelines. In the first pipeline, the adapters and low-quality reads were trimmed using fastp45 v0.23.4 (https://github.com/OpenGene/fastp), aligned to the human reference genome (build GRCh38p14, (ftp://ftp.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genomes/all/GCA/000/001/405/GCA_000001405.15_GRCh38/seqs_for_alignment_pipelines.ucsc_ids/GCA_000001405.15_GRCh38_no_alt_analysis_set.fna.gz.) with Bismark-Bowtie246 v0.23.0 (https://github.com/FelixKrueger/Bismark), and duplicated reads from aligned bam files were removed with Bismark. In the other pipeline, Trim Galore v0.6.2 (https://github.com/FelixKrueger/TrimGalore), BWA-MEM2 v2.2.1 (https://github.com/bwa-mem2/bwa-mem2), bwa-meth v0.2.7 (https://github.com/brentp/bwa-meth), and GATK4 v 4.5.0.0 (https://broadinstitute.github.io/picard/) were used for trimming, alignment, and deduplication. For TAPS, two pipelines were engaged. In the first pipeline, the Bismark-bowtie2 aligner was replaced with BWA-MEME v1.0.6 (https://github.com/kaist-ina/BWA-MEME), and GATK4 was used for deduplication. After removing duplicated reads from different methods, the per-cytosine methylation information was called by the asTair v3.3.2 (https://bitbucket.org/bsblabludwig/astair/src/master/) with in silico single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) exclusion using Quartet SNP reference datasets, ensuring CpG-specific signal detection before Bismark-mediated pipeline consensus merging. FastQC v0.12.1 (https://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/), Qualimap47 v2.3 (http://qualimap.conesalab.org/), and MultiQC48 v1.10.1 (https://seqera.io/multiqc/) were used as quality control tools without further separate explanations and were all run with default parameters.

The reference of lambda DNA (Enterobacteria phage lambda, NC_001416.1) as negative base conversion control was spiked into the GRCh38p14 human reference genome fasta file (NCBI, GCA_000001405.15). The ALT contigs were removed from the fasta file.

For the ONT platform, Megalodon v2.2.9 (https://nanoporetech.github.io/megalodon) and Tombo v1.5.149 (https://github.com/nanoporetech/tombo) were utilized to call the bases and modifications from the raw fast5 files. DeepSignal250 v0.1.3 and f5c v1.1 (https://github.com/hasindu2008/f5c) were used for downstream methylation calling and correction. The configuration file of the MinION DNA R9.4.1 5mC model was retrieved from the Rerio database.

For PacBio, pbccs v6.4.0 (https://github.com/nlhepler/pbccs) and pbmm2 v1.9.0 (https://github.com/PacificBiosciences/pbmm2) were used for base calling and alignment, respectively. After that, ccsmeth v0.3.2 (https://github.com/PengNi/ccsmeth), Primrose v1.3.0 (https://github.com/mattoslmp/primrose), and pb-cpg-tools v2.2.0 (https://github.com/PacificBiosciences/pb-CpG-tools) were used to call the methylation information.

Integration of reference datasets

Methylation reference datasets construction commenced with raw data processing across six sequencing batches, each containing three technical replicates processed through two independent analytical pipelines. Initial quality filtering retained cytosines with ≥ 10× coverage per strand using custom Python scripts, followed by intra-batch consensus determination requiring detection in ≥ 4/6 replicate-pipeline combinations (3 replicates × 2 pipelines) with median absolute deviation (MAD) < 10%.

Cross-batch integration applied iterative consensus thresholds, mandating CpG detection in ≥ 4/6 batches under identical MAD constraints. Strand-discordant positions (inter-strand methylation difference > 20%) were preserved as single-strand entries, while concordant CpG sites underwent secondary validation via duplex-aware merging before consensus filtering.

Annotation

Dual consensus strategies were employed for strand concordance annotation to maximize biological relevance. Primary strand-aware processing preserved all CpG sites meeting depth ( ≥ 20×) and reproducibility thresholds (MAD < 5% in ≥ 4/6 batches), while secondary duplex-aware processing merged strands before filtering, retaining CpG sites with inter-strand methylation differences ≤ 20%.

Orthogonal validation with 850 K arrays

850 K data across three experimental batches, each processing four Quartet reference materials with three technical replicates. Raw idat files were processed using the R packages ChAMP51 v2.26.0 and minfi52 v1.36.0. The single-sample Noob (ssNoob)53,54 method was used to correct for background fluorescence and dye biases. Next, samples with a proportion of failed probes (probe detection P > 0.01) above 0.1 were discarded. Probes that failed in more than 10% of the remaining samples were removed. Probes with < 3 beads in at least 5% of samples were also removed. All non-CpG probes, SNP-related probes, and multi-hit probes were filtered out. After preprocessing, the methylation dataset contained 733,868 probes. Finally, the corrected methylated and unmethylated signals were used to calculate β values. In this process, the β threshold was set to 0.001.

Overlapping CpG sites between 850 K and the reference datasets underwent methylation level comparison, with validation success determined by array β-values falling within reference mean ± 3 SD intervals. Concordance metrics, including Pearson correlation (PCC), spearman correlation (SCC), coefficient of determination (R²), mean absolute error (MAE, %), and root mean square error (RMSE), were calculated using custom Python scripts.

Sensitivity analysis

The robustness of the reference datasets was evaluated through sensitivity testing in two perturbation modes: 1) exclusion of entire sequencing batches (n = 6 scenarios), and 2) removal of individual libraries per batch (n = 18 scenarios). Each perturbed dataset underwent identical consensus filtering parameters as the primary reference construction, with performance assessed through four metrics: CpG coverage deviation from primary reference, inter-dataset PCC, RMSE of CpG methylation, and Jaccard of included sites.

Accuracy analysis

Performance evaluation of 11 sequencing batches (6 reference-construction + 5 independent batches) was focused on strand-concordant CpGs to ensure cross-protocol comparability. Recall was calculated as the ratio of overlapping CpGs between test datasets and the reference, while PCC and RMSE were computed using β-values ranging from 0 to 100 at shared sites. Long-read datasets (Oxford Nanopore and PacBio) underwent native methylation calling without consensus filtering to assess raw platform performance, whereas standard preprocessing pipelines were applied to short-reads batches.

Multidimensional analysis of quality metrics

For nine reference-construction batches, 21 quality metrics spanning sequencing quality (e.g., Q30%, duplication rate), library preparation (insert size, GC%), reproducibility (Jaccard and PCC), and reference-dependent accuracy (MAE, RMSE, and PCC) were aggregated. Hierarchical clustering with Euclidean distance and complete linkage identified batch-specific performance patterns, while row-wise Z-score normalization enabled cross-metric comparability in heatmap visualization.

Mantel test

Metric-accuracy associations were assessed using Mantel tests implemented in the R package linkET v0.0.7.4 (https://github.com/Hy4m/linkET), using a permutation approach to determine significance to quantify relationships between technical quality metrics and reference-dependent accuracy measures. Three reference-dependent accuracy measures (Recall, PCC, and RMSE) were tested against 13 technical metrics, with significance thresholds set at p < 0.01 (Bonferroni-corrected). Correlation matrices for inter-metric relationships were calculated using Pearson’s method, with significance determined by two-tailed t-tests (α = 0.05).

Reference-dependent metrics

Reference-dependent accuracy was evaluated using three metrics: (1) recall, defined as the ratio of CpG sites overlapping between test datasets and the reference standard; (2) Pearson correlation coefficient (PCC), quantifying linear agreement in methylation percentages at shared CpG sites; (3) Root mean square error (RMSE), measuring absolute deviation from reference methylation levels.

Reference-independent metrics

Reference-independent reproducibility metrics included: (1) Jaccard index, measuring the proportion of overlapping CpG sites detected between two replicates, calculated as |A ∩ B | / | A∪B | ; (2) inter-replicate PCC, assessing methylation percentage correlations across call sets; (3) median absolute deviation (MAD), evaluating per-CpG consistency; and (4) signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), calculated by comparing Euclidean distances between distinct Quartet samples (“signals”) to those between technical replicates of the same sample (“noises”) using the first two principal components (PCs) of PCA.

Statistics & reproducibility

Study design

Four DNA reference materials (D5, D6, F7, M8) were profiled across three protocols (WGBS, EM-seq, TAPS) with three independent technical replicates per donor per batch, enabling within-batch replication and cross-batch/lab assessments.

Statistical analyses

Reproducibility was quantified using Pearson correlation and Jaccard index. All analyses were scripted, version-controlled, and run with fixed parameters.

Sample size

No statistical method was used to predetermine the sample size. Sizes were fixed by the certified Quartet reference set and a factorial design sufficient to estimate variance components and stabilize metrics. We sequenced three replicates of each of the four Quartet DNA reference materials using three commercially available short-read sequencing protocols: WGBS, EMseq, and TAPS, generating nine data batches. Each batch included 12 libraries, resulting in a total of 108 libraries across the nine batches. These sample sizes are sufficient to provide within-batch technical replication, cross-protocol comparisons, and cross-batch/laboratory reproducibility assessment. Details are illustrated explicitly in Fig. 1.

Data exclusion

All data from planed experiments have been included. All attempts at replication were successful.

Randomization

Samples were allocated by a pre-specified, balanced design rather than randomization. Each batch contained 12 libraries—three technical replicates per donor (D5, D6, F7, M8)—loaded in an interleaved order (D5-1, D6-1, F7-1, M8-1, D5-2, D6-2, F7-2, M8-2, D5-3, D6-3, F7-3, M8-3) to minimize run-order effects. Wet-lab personnel were blinded to donor identities and the allocation key. Because groups are defined by donor and protocol (not treatment), covariates were controlled by including all donors in every batch under identical preparation and sequencing conditions.

Blinding

Data collection was blinded. Analysis was not, because donor-specific references (Quartet SNP datasets) and ground-truth comparisons required linking each library to its known identity; analyses were fully scripted with fixed parameters and objective metrics, so blinding was not relevant.

Ethical Statement

The study was approved by the institutional review board (IRB) of the School of Life Sciences, Fudan University (BE2050).

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Source data

Acknowledgements

We thank the Quartet Project team members for their valuable contributions to the design and execution of this project. This work was supported in part by Science & Technology Fundamental Resources Investigation Program (2022FY101203 to Y.Z.), the Basic Research Fund Project of the National Institute of Metrology (AKYZD2202 to L.D.), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (T2425013 to Y.Z., 32370701 to L.S., 32470692 to Y.Z., and 32170657 to L.S.), the Natural Science Foundation of Shanghai (24JS2840100 to Y.Z.), the National Key R&D Project of China (2023YFC3402501 to L.S.), the Shanghai Municipal Science and Technology Major Project (2023SHZDZX02 and 2017SHZDZX01 to L.S.), State Key Laboratory of Genetics and Development of Complex Phenotypes (SKLGE-2117 to L.S.), and the 111 Project (B13016 to L.S.). We acknowledge Computing for the Future at Fudan (CFFF), the Human Phenome Data Center at Fudan University, and the High-Performance Computing Center at Central South University for computational support. Figures 1, 4A, S1, and S11A were created in BioRender. Xi, H. https://BioRender.com/fbst4bu.

Author contributions

Y.Z., L.S., L.D., and R.Z. conceived and supervised the study. X.G., Q.C., Y.F.Z., Y.J.Z., Q.L., S.D., Y.M., B.H., L.R., R.M., W.H., Y.Y., B.L., F.Q., Y.S., Z.Z., W.X., X.F., and J.L. performed data analysis and/or interpretation. P.N. and J.W. performed the upstream analysis of long-read sequencing. X.G. managed the datasets and generated the majority of figures. X.G. and Q.C. wrote the initial draft. R.Z., L.D., Y.Z., and L.S. critically revised the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript. Quartet Project participants generously contributed time and resources essential to the completion and analysis of this study.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Data availability

The raw sequence data used in this paper have been deposited in the Genome Sequence Archive (GSA) under accession HRA011205. The microarray data used in this paper have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) under accession GSE241900. Reference datasets are available at (10.6084/m9.figshare.29481713.v1, 10.6084/m9.figshare.29481713.v1)55; a mirror is provided at the Quartet Data Portal (https://reference-datasets.chinese-quartet.org/index.html?prefix=develop/Methylation/v20250409/) under the Administrative Regulations of the People’s Republic of China on Human Genetic Resources. The raw sequence data, CpG call sets, and microarray IDATs are also available in NODE56 OEP00004817. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

Source code for data analysis and figure generation is available on Code Ocean: (10.24433/CO.1027879.v1)57, under an MIT license.

Competing interests

B.L., F.Q., Y.S. and Z.Z. are employees of Burning Rock Biotech Ltd. All other authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Xiaorou Guo, Qingwang Chen, Yuanfeng Zhang, and Yujing Zhang.

Contributor Information

Leming Shi, Email: lemingshi@fudan.edu.cn.

Rui Zhang, Email: ruizhang@nccl.org.cn.

Yuanting Zheng, Email: zhengyuanting@fudan.edu.cn.

Lianhua Dong, Email: donglh@nim.ac.cn.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at (10.1038/s41467-025-64250-z).

References

- 1.Smith, Z. D. & Meissner, A. DNA methylation: roles in mammalian development. Nat. Rev. Genet.14, 204–220 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Laird, P. W. The power and the promise of DNA methylation markers. Nat. Rev. Cancer3, 253–266 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Robertson, K. D. DNA methylation and human disease. Nat. Rev. Genet.6, 597–610 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heyn, H. & Esteller, M. DNA methylation profiling in the clinic: applications and challenges. Nat. Rev. Genet.13, 679–692 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baylin, S. B. & Jones, P. A. A decade of exploring the cancer epigenome—biological and translational implications. Nat. Rev. Cancer11, 726–734 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Laird, P. W. Principles and challenges of genome-wide DNA methylation analysis. Nat. Rev. Genet.11, 191–203 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miura, F., Enomoto, Y., Dairiki, R. & Ito, T. Amplification-free whole-genome bisulfite sequencing by post-bisulfite adaptor tagging. Nucleic Acids Res40, e136 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vaisvila, R. et al. Enzymatic methyl sequencing detects DNA methylation at single-base resolution from picograms of DNA. Genome Res31, 1280–1289 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu, Y. et al. Bisulfite-free direct detection of 5-methylcytosine and 5-hydroxymethylcytosine at base resolution. Nat. Biotechnol.37, 424–429 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang, Y., Zhao, Y., Bollas, A., Wang, Y. & Au, K. F. Nanopore sequencing technology, bioinformatics and applications. Nat. Biotechnol.39, 1348–1365 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ni, P. et al. DNA 5-methylcytosine detection and methylation phasing using PacBio circular consensus sequencing. Nat. Commun.14, 4054 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cao, B. et al. The performance of whole genome bisulfite sequencing on DNBSEQ-Tx platform examined by different library preparation strategies. Heliyon9, e16571 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Olova, N. et al. Comparison of whole-genome bisulfite sequencing library preparation strategies identifies sources of biases affecting DNA methylation data. Genome Biol.19, 33 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tsuji, J. & Weng, Z. Evaluation of preprocessing, mapping and postprocessing algorithms for analyzing whole genome bisulfite sequencing data. Brief. Bioinform.17, 938–952 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bock, C. et al. Quantitative comparison of genome-wide DNA methylation mapping technologies. Nat. Biotechnol.28, 1106–1114 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wu, Q., Yang, M., Yang, Y., Iqbal, A. & Zhou, L. Assessment of bisulfite sequencing alignment tools for whole genome analysis in plants. Int. J. Biol. Macromol.305, 140940 (2025). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Balaramane, D., Spill, Y. G., Weber, M. & Bardet, A. F. MethyLasso: a segmentation approach to analyze DNA methylation patterns and identify differentially methylated regions from whole-genome datasets. Nucleic Acids Res52, e98 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zheng, Y. et al. Prediction of genome-wide DNA methylation in repetitive elements. Nucleic Acids Res45, 8697–8711 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bunk, D. M. Reference materials and reference measurement procedures: an overview from a national metrology institute. Clin. Biochem. Rev.28, 131–137 (2007). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vesper, H. W., Miller, W. G. & Myers, G. L. Reference materials and commutability. Clin. Biochem. Rev.28, 139–147 (2007). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hardwick, S. A., Deveson, I. W. & Mercer, T. R. Reference standards for next-generation sequencing. Nat. Rev. Genet.18, 473–484 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fang, L. T. et al. Establishing community reference samples, data and call sets for benchmarking cancer mutation detection using whole-genome sequencing. Nat. Biotechnol.39, 1151–1160 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zook, J. M. et al. Extensive sequencing of seven human genomes to characterize benchmark reference materials. Sci. Data3, 160025 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Foox, J. et al. The SEQC2 epigenomics quality control (EpiQC) study. Genome Biol.22, 332 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bock, C. et al. Quantitative comparison of DNA methylation assays for biomarker development and clinical applications. Nat. Biotechnol.34, 726–737 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dunham, I. et al. An integrated encyclopedia of DNA elements in the human genome. Nature489, 57–74 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sigurpalsdottir, B. D. et al. A comparison of methods for detecting DNA methylation from long-read sequencing of human genomes. Genome Biol.25, 69 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brooks, T. G., Lahens, N. F., Mrčela, A. & Grant, G. R. Challenges and best practices in omics benchmarking. Nat. Rev. Genet.25, 326–339 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zheng, Y. et al. Multi-omics data integration using ratio-based quantitative profiling with Quartet reference materials. Nat. Biotechnol.42, 1133–1149 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yu, Y. et al. Correcting batch effects in large-scale multiomics studies using a reference-material-based ratio method. Genome Biol.24, 201 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ren, L. et al. Quartet DNA reference materials and datasets for comprehensively evaluating germline variant calling performance. Genome Biol.24, 270 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yu, Y. et al. Quartet RNA reference materials improve the quality of transcriptomic data through ratio-based profiling. Nat. Biotechnol.42, 1118–1132 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tian, S. et al. Quartet protein reference materials and datasets for multi-platform assessment of label-free proteomics. Genome Biol.24, 202 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang, N. et al. Quartet metabolite reference materials for inter-laboratory proficiency test and data integration of metabolomics profiling. Genome Biol.25, 34 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ziller, M. J., Hansen, K. D., Meissner, A. & Aryee, M. J. Coverage recommendations for methylation analysis by whole-genome bisulfite sequencing. Nat. Methods12, 230–232 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Harris, R. A. et al. Comparison of sequencing-based methods to profile DNA methylation and identification of monoallelic epigenetic modifications. Nat. Biotechnol.28, 1097–1105 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Christiansen, C. et al. Enhanced resolution profiling in twins reveals differential methylation signatures of type 2 diabetes with links to its complications. eBioMedicine103, 105096 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tanić, M. et al. Comparison and imputation-aided integration of five commercial platforms for targeted DNA methylome analysis. Nat. Biotechnol.40, 1478–1487 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kurdyukov, S. & Bullock, M. DNA methylation analysis: choosing the right method. Biology5, 3 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yang, J. et al. The quartet data portal: integration of community-wide resources for multiomics quality control. Genome Biol.24, 245 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Booth, M. J. et al. Quantitative Sequencing of 5-Methylcytosine and 5-Hydroxymethylcytosine at Single-Base Resolution. Science336, 934–937 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Booth, M. J. et al. Oxidative bisulfite sequencing of 5-methylcytosine and 5-hydroxymethylcytosine. Nat. Protoc.8, 1841–1851 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yu, M. et al. Base-resolution analysis of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine in the mammalian genome. Cell149, 1368–1380 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liu, T. & Conesa, A. Profiling the epigenome using long-read sequencing. Nat. Genet.57, 27–41 (2025). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chen, S., Zhou, Y., Chen, Y. & Gu, J. fastp: an ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics34, i884–i890 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Krueger, F. & Andrews, S. R. Bismark: a flexible aligner and methylation caller for Bisulfite-Seq applications. Bioinformatics27, 1571–1572 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.García-Alcalde, F. et al. Qualimap: evaluating next-generation sequencing alignment data. Bioinformatics28, 2678–2679 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ewels, P., Magnusson, M., Lundin, S. & Käller, M. MultiQC: summarize analysis results for multiple tools and samples in a single report. Bioinformatics32, 3047–3048 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stoiber, M. et al. De novo Identification of DNA Modifications Enabled by Genome-Guided Nanopore Signal Processing. 094672 Preprint at 10.1101/094672 (2017).

- 50.Ni, P. et al. DeepSignal: detecting DNA methylation state from Nanopore sequencing reads using deep-learning. Bioinformatics35, 4586–4595 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tian, Y. et al. ChAMP: updated methylation analysis pipeline for Illumina BeadChips. Bioinformatics33, 3982–3984 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Aryee, M. J. et al. Minfi: a flexible and comprehensive Bioconductor package for the analysis of Infinium DNA methylation microarrays. Bioinforma. Oxf. Engl.30, 1363–1369 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fortin, J.-P., Triche, T. J. & Hansen, K. D. Preprocessing, normalization and integration of the Illumina HumanMethylationEPIC array with minfi. Bioinforma. Oxf. Engl.33, 558–560 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Triche, T. J., Weisenberger, D. J., Van Den Berg, D., Laird, P. W. & Siegmund, K. D. Low-level processing of Illumina Infinium DNA methylation BeadArrays. Nucleic Acids Res41, e90 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Guo, X. Quantitative methylation reference datasets of Quartet DNA reference materials for benchmarking genome- wide epigenome sequencing. figshare 10.6084/m9.figshare.29481713.v1 (2025). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 56.Ling, Y. et.al. Advances in multi-omics big data sharing platform research. Chin. Bull. Life Sci. 77, 1553–1560 (2023).

- 57.Guo, X. et al. Quantitative methylation reference datasets of Quartet DNA reference materials for benchmarking genome-wide epigenome sequencing. 10.24433/CO.1027879.v1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The raw sequence data used in this paper have been deposited in the Genome Sequence Archive (GSA) under accession HRA011205. The microarray data used in this paper have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) under accession GSE241900. Reference datasets are available at (10.6084/m9.figshare.29481713.v1, 10.6084/m9.figshare.29481713.v1)55; a mirror is provided at the Quartet Data Portal (https://reference-datasets.chinese-quartet.org/index.html?prefix=develop/Methylation/v20250409/) under the Administrative Regulations of the People’s Republic of China on Human Genetic Resources. The raw sequence data, CpG call sets, and microarray IDATs are also available in NODE56 OEP00004817. Source data are provided with this paper.

Source code for data analysis and figure generation is available on Code Ocean: (10.24433/CO.1027879.v1)57, under an MIT license.