Abstract

Cachexia is associated with poor prognosis in patients with chronic disease. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNFα) plays a pivotal role in mediating cachexia and has been demonstrated to inhibit skeletal muscle differentiation in vitro. It has been proposed that TNFα-mediated activation of NFκB leads to down regulation of MyoD, however the mechanisms underlying TNFα effects on skeletal muscle remain poorly understood. We report here a novel pathway by which TNFα inhibits muscle differentiation through activation of caspases in the absence of apoptosis. TNFα-mediated caspase activation and block of differentiation are dependent upon the expression of PW1, but occur independently of NFκB activation. PW1 has been implicated previously in p53-mediated cell death and can induce bax translocation to the mitochondria. We show that bax-deficient myoblasts do not activate caspases and differentiate in the presence of TNFα, highlighting a role for bax-dependent caspase activation in mediating TNFα effects. Taken together, our data reveal that TNFα inhibits myogenesis by recruiting components of apoptotic pathways through PW1.

Keywords: bax/cachexia/caspase/Peg3/TNFα

Introduction

Cachexia or muscle wasting is a major component of chronic disease states such as infection, AIDS and cancer. A similar process of muscle atrophy accompanies aging (Kotler, 2000). Tumor necrosis factor-α (TNFα) is a principle cytokine mediating cachexia (Tisdale, 2001); however, the mechanisms by which TNFα causes cachexia are not well understood. One primary response to TNFα is a marked increase in skeletal muscle protein degradation (Tisdale, 2001). It is known that TNFα can elicit apoptosis in a variety of cell types while other studies indicate that TNFα can inhibit skeletal muscle differentiation in vitro (Miller et al., 1988; Szalay et al., 1997; Guttridge et al., 2000). Therefore, cachexia may result from the combined processes of muscle protein reduction, cell death and attenuated muscle regeneration (Tisdale, 2001).

One hallmark of TNFα signaling is the activation of NFκB. NFκB is an ubiquitous transcription factor normally inactive and sequestered in the cytoplasm through association with IκB. A variety of stimuli, including TNFα exposure, leads to the degradation of IκB, allowing NFκB translocation to the nucleus (Israel, 2000). It has been demonstrated that TNFα exposure results in a downregulation of the levels of the myogenic regulatory factors, MyoD and myogenin, in cultured muscle cells (Szalay et al., 1997). A novel mechanism has recently been proposed whereby NFκB mediates the degradation of MyoD transcripts in myogenic cells, which could contribute to the ability of TNFα to block terminal differentiation (Guttridge et al., 2000). The successful differentiation of skeletal muscle requires cell cycle exit concomitant with the upregulation of p21 and myogenin (Andres and Walsh, 1996; Walsh, 1997). In addition, NFκB can inhibit myogenesis by the induction of cyclin D1, which promotes cell proliferation (Guttridge et al., 1999). A failure to properly coordinate cell cycle exit and differentiation has been demonstrated to lead to myoblast cell death in vitro, suggesting that cell death and terminal differentiation are closely linked (Guo and Walsh, 1997; Wang et al., 1997).

Caspases execute cell death in response to cytokines such as TNFα and internal cellular signals such as p53 (Hengartner, 2000). The cytokine- and p53-mediated cell death pathways use distinct members of the caspase family (Natoli et al., 1998; Hengartner, 2000). For example, homozygous deletion of caspase-8 abrogates cytokine-mediated apoptosis (i.e. TNFα, FasL), but not p53-mediated apoptosis (Varfolomeev et al., 1998; Yeh et al., 2000). Conversely, deletion of caspase-9 abrogates p53- and not cytokine-mediated apoptosis (Hakem et al., 1998; Kuida et al., 1998). While p53-mediated cell death requires an early step involving cytochrome c release from the mitochondria, both pathways ultimately engage mitochondrial processes (Desagher and Martinou, 2000). Recently, it has been shown that differentiation of avian, murine and human muscle cells is blocked following disruption of mitochondrial function, indicating that cell death and differentiation share common pathways in muscle cells (Rochard et al., 2000).

We reported previously the identification of a large zinc-finger containing protein, PW1, in a screen for muscle regulatory factors (Relaix et al., 1996, 1998). PW1 is identical to the paternally expressed gene Peg3 (Kuroiwa et al., 1996) (referred to as PW1 in this study). PW1 is expressed at high levels in developing skeletal muscle and muscle cell lines. We subsequently demonstrated that PW1 interacts with TRAF2 and that PW1 participates in the TNFα signal transduction pathway (Relaix et al., 1998). TRAF2 is a member of the TRAF protein family, initially identified as TNFα receptor associated factors, which participate in NFκB activation (Inoue et al., 2000). We found that PW1 is able to activate NFκB whereas an N-terminal truncated portion of PW1 (ΔPW1) can block TNFα-mediated NFκB activation (Relaix et al., 1998). In addition to a role in the TNFα pathway, PW1 was independently identified as a p53-induced gene involved in p53-mediated cell death (Relaix et al., 2000). The co-expression of PW1 and SIAH-1, another p53-inducible gene that physically associates with PW1, results in apoptosis (Relaix et al., 2000). Consistent with a role in the p53 cell death pathway, it has been demonstrated that PW1 expression results in bax translocation to the mitochondria (Deng and Wu, 2000). Both MyoD and p53 mediate cell cycle arrest through the upregulation of p21 (Halevy et al., 1995; Gartel et al., 1996). Like p53, MyoD is also capable of inducing PW1 expression in fibroblasts (this study). MyoD, however, mediates differentiation whereas p53 mediates apoptosis, thus the high expression of PW1 in muscle cells likely reflects a role in mediating myogenesis rather than cell death.

We report here that TNFα inhibits muscle differentiation through the activation of caspases and that the effects of TNFα are dependent upon the presence of PW1 expression. Caspase inhibitors can reverse the block in differentiation elicited by TNFα. Caspase activation by TNFα does not result in apoptosis during the myoblast to myotube transition, revealing that the block in differentiation reflects a specific role for caspases in the myogenic program. Recently, it has been proposed that NFκB plays a pivotal role in the TNFα-response in muscle cells, thus we determined whether NFκB activation and caspase activation pathways interact with each other. We find that the rescue of differentiation by caspase inhibitors in the presence of TNFα does not abrogate NFκB activation and that suppression of NFκB activation does not block TNFα-mediated caspase activation. Robust TNFα-induced NFκB activation occurs in myogenic cells that are resistant to the TNFα-mediated block in differentiation, suggesting that NFκB does not play a major role in mediating the effects of TNFα upon the myogenic program. The ability of TNFα to mediate caspase-dependent inhibition of differentiation is observed only in PW1 expressing cells. We find that PW1 expression is required for caspase activation in response to TNFα and that primary myoblasts, which are deficient for bax, a downstream target of PW1, undergo robust differentiation in the presence of TNFα. Taken together, these results uncover a novel role for components of the cytokine-independent cell death effectors, specifically PW1 and its downstream effector bax, during skeletal myogenesis.

Results

TNFα inhibits muscle cell differentiation in PW1 expressing myogenic cell lines

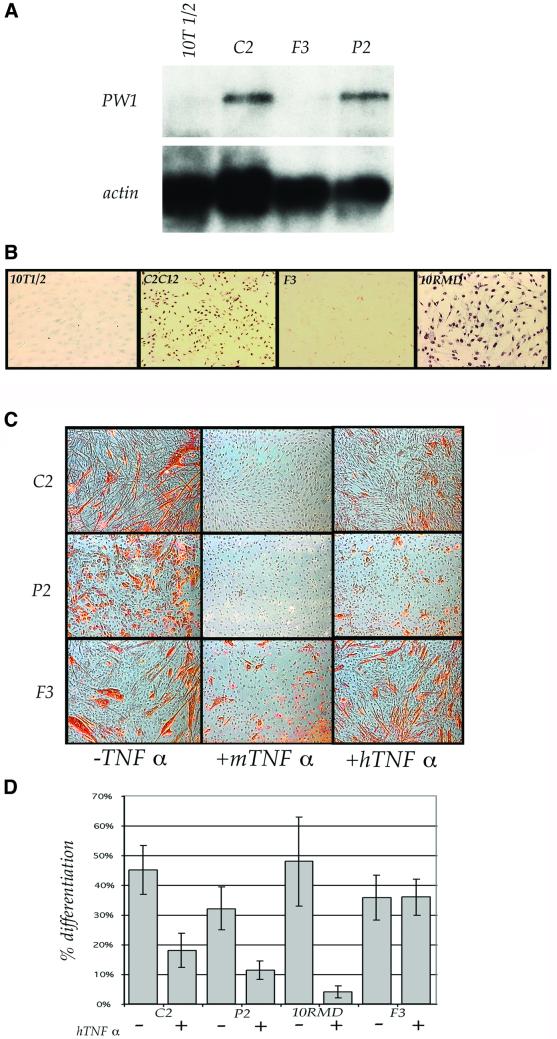

We had tested the effects of TNFα on muscle cells initially due to the observation that PW1 is expressed in most myogenic cells at high levels and participates in the TNFα signaling pathway (Relaix et al., 1996, 1998). We tested P2 and F3 myoblasts, which are derived from 10T1/2 fibroblasts exposed to 5-azacytidine, and the 10RMD line, which is derived from 10T1/2 fibroblasts stably transfected with MyoD under the control of the CMV promoter, as well as the established murine myogenic cell line, C2, derived from perinatal mouse skeletal muscle. PW1 is expressed in C2, P2 and 10RMD cells, whereas we detect PW1 expression in neither 10T1/2 nor in F3 cells (Figure 1A and B). Consistent with previously reported results (Guttridge et al., 1999, 2000), we observe that exposure of C2 cells to TNFα inhibits differentiation (Figure 1C). P2 and 10RMD cells are inhibited by murine TNFα (referred to as TNFα), whereas F3 cells show only a weak inhibition (Figure 1A). In the presence of human TNFα (hTNFα), which signals exclusively through the TNF receptor I (TNFRI) in murine cells, we find that F3 cells are unaffected whereas all other cell lines tested are blocked for differentiation (Figure 1C). Therefore, TNFα-mediated inhibition of muscle differentiation is primarily transduced through TNFRI and may depend upon PW1 expression.

Fig. 1. TNFα selectively inhibits muscle differentiation of PW1 expressing cells. (A) Northern blot analysis of PW1 expression in myogenic cell lines shows that P2 and C2 cells express high levels of PW1, whereas F3 myoblasts and the parental 10T1/2 cells do not express detectable levels of PW1 transcripts. Blots were hybridized simultaneously with actin to verify mRNA integrity and loading. (B) Immunolocalization of PW1 confirms PW1 expression in myogenic cells (C2 and 10RMD) but not in the F3 cells or in 10T1/2 cells. (C) Immunohistochemistry of myosin (red), a marker of myogenic differentiation, in myogenic cells cultured in DM in the presence or absence of TNFα. PW1-expressing C2 and P2 cells differentiate in the absence of TNFα (–TNFα) but do not differentiate if cultured in the presence of either murine (+mTNFα) or human (+hTNFα) TNFα. F3 cells, which do not express PW1, differentiate regardless the presence of TNFα. (D) Quantitative analysis of myogenic differentiation (% differentiation): only F3 cells are resistant to TNFα-mediated inhibition of differentiation.

PW1 expression confers TNFα sensitivity to F3 myoblasts

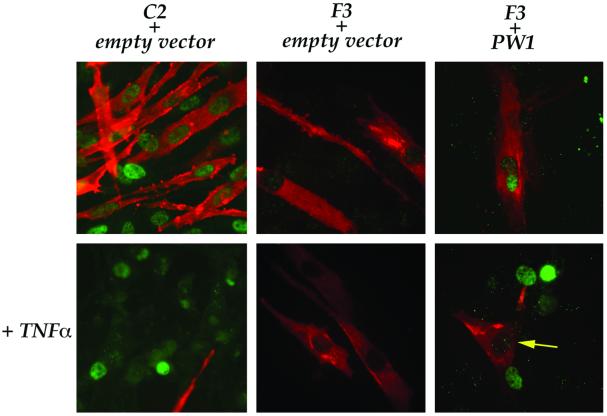

The observation that F3 cells are capable of differentiation in the presence of TNFα raised the possibility that PW1 expression, which is absent in this cell line, confers TNFα sensitivity. Initial attempts at deriving stable cell lines carrying PW1 resulted in cells that shut down ectopic expression (data not shown), which may reflect endogenous cell cycle-dependent expression (Relaix et al., 1996). Thus, we relied upon transient transfection of PW1 followed by TNFα treatment. As seen in Figure 2, C2 cells, which normally express high levels of PW1, respond normally to TNFα following transfection of pcDNA (empty vector), thus the transfection procedures interfere with neither differentiation nor with the ability of TNFα to block differentiation. Since PW1 is induced in response to p53 in a cell death context, it was important to verify that transfection procedures do not activate PW1. Transfection of F3 cells with the empty vector does not alter the behavior of F3 cells in response to TNFα, and neither does transfection alone activate PW1 (Figure 2). In contrast, PW1-transfected F3 cells differentiate normally (Figure 2) but fail to differentiate in response to TNFα (Figure 2). Taken together, these results demonstrate that PW1 expression is sufficient to confer TNFα sensitivity, which results in a block of differentiation.

Fig. 2. PW1 confers TNFα sensitivity to myogenic cells. C2 and F3 cells transfected with either the empty vector or PW1 expression vector (PW1) and induced to differentiate in the presence or absence of TNFα. PW1 (green) and myosin (red) were immuno-detected to assess PW1 expression and differentiation, respectively. In both C2 and F3 cells, transfection with empty vector neither affects the pattern of differentiation in the absence nor in the presence of TNFα (TNFα). Ectopic PW1 expression in F3 cells does not affect differentiation (upper right panel). In contrast, virtually all F3 cells that express PW1 are no longer able to differentiate in the presence of TNFα (lower right panel). Only PW1-negative F3 cells (arrow) are myosin-positive upon TNFα treatment. Microscopic fields representative of duplicate plates are shown.

TNFα-mediated NFκB activation is not sufficient to block myogenic differentiation

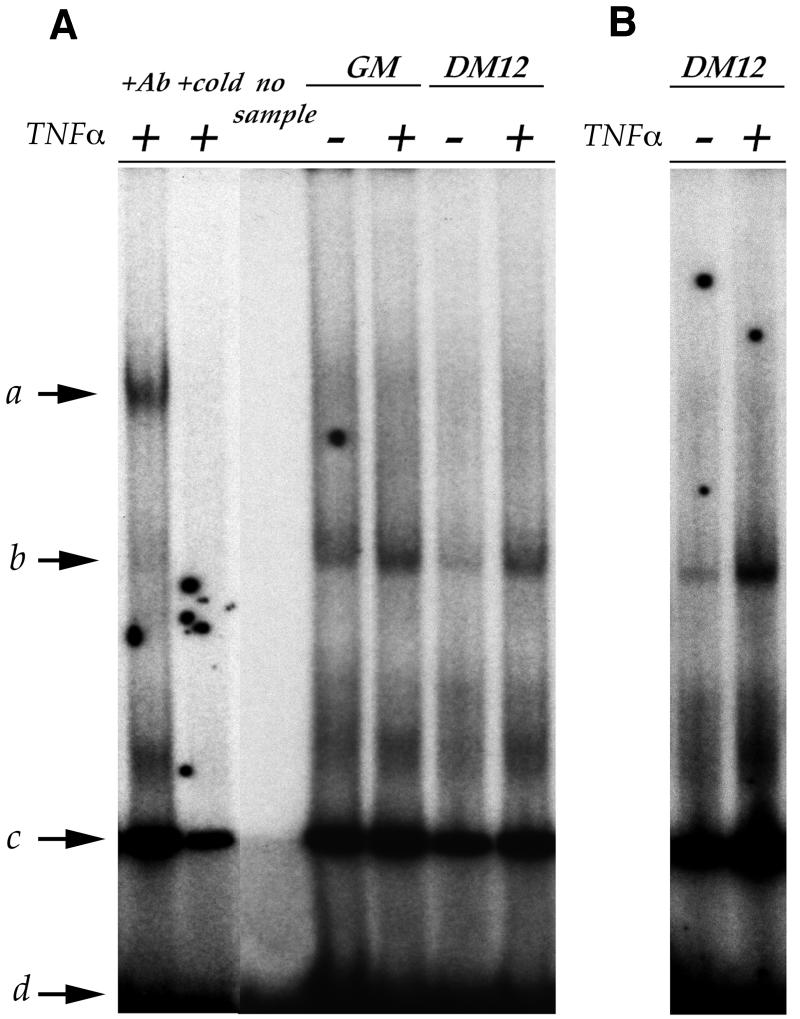

It has been reported previously that the activation of NFκB leads to a block in muscle differentiation (Guttridge et al., 2000; our unpublished results). We therefore monitored NFκB activation in differentiating C2 and F3 cells in the presence or absence of TNFα. We observe that C2 and F3 cells activate NFκB in response to TNFα (Figure 3A and B). Since F3 cells are capable of differentiating even though robust NFκB activation is observed, we conclude that TNFα-mediated NFκB activation is not sufficient to inhibit muscle differentiation. Curiously, pharmacological agents that are able to block NFκB activation such as MG132, PDTC and BAY (Li et al., 1998; Kaliman et al., 1999; Richter et al., 2001) result in massive cell death (data not shown), suggesting that NFκB activation may play a more critical role in governing cell survival.

Fig. 3. Myoblast differentiation can occur in the presence of TNFα-mediated NFκB activation. EMSA performed with a radiolabeled oligonucleotide containing a NFκB binding site on nuclear extracts from: (A) proliferating C2 (GM) and differentiating C2 (DM12) cells with or without TNFα treatment; and (B) differentiating F3 cells with or without TNFα treatment. NFκB binding activity (b) decreases during differentiation and is stimulated upon TNFα treatment in both C2 and F3 cells. The presence of the p65 subunit in NFκB complexes is demonstrated by a super-shift (a), performed by incubating the nuclear extract with an antibody against p65 (+Ab). An aspecific band (c) and the unbound probe (d) are shown. As controls, samples with no nuclear extract (no sample) or reacted in the presence of excess of unlabeled competitor are shown (+cold).

Caspase activation is necessary for the TNFα-mediated block in skeletal muscle differentiation

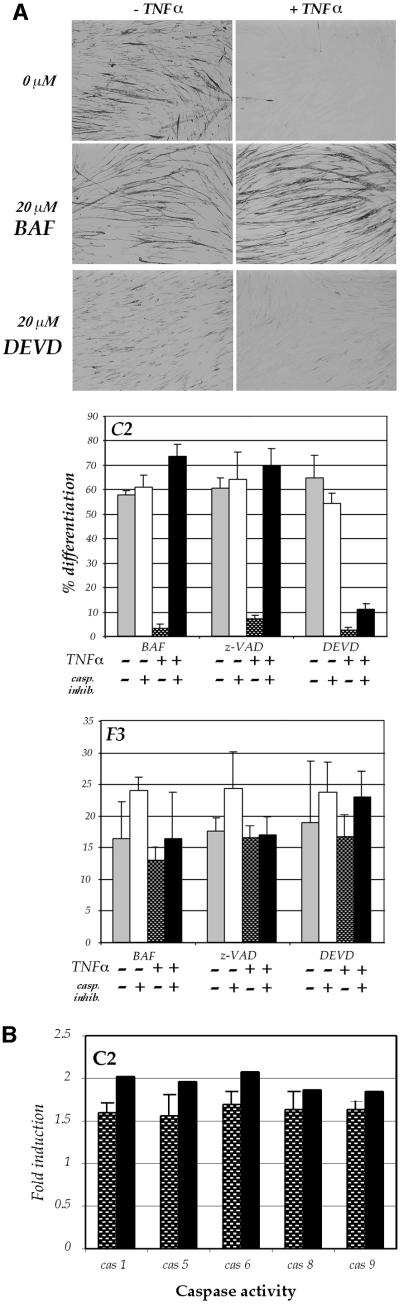

TNFα not only activates NFκB, but is also well documented to activate the cytokine caspase pathway (Natoli et al., 1998; Varfolomeev et al., 1998). In view of the key role caspases play in governing and ultimately executing cell death, combined with the fact that PW1 is a key component in p53-mediated cell death and bax translocation (Deng and Wu, 2000; Relaix et al., 2000), we investigated whether the caspase pathways could underlie the effects of TNFα upon the myogenic program. We utilized caspase inhibitors in order to determine whether caspase activation is necessary for TNFα-mediated inhibition of differentiation. The addition of either of the pan-caspase inhibitors z-VAD or BAF restore the capacity of TNFα-treated cells to differentiate (Figure 4A), indicating that caspase activity is necessary for the TNFα-mediated block of differentiation. In the absence of TNFα, the addition of either pan-caspase inhibitor on C2 myoblasts does not enhance differentiation (Figure 4A), revealing that differentiation-associated cell death does not selectively target populations that would otherwise have differentiated. In order to ascertain which caspases are involved in the TNFα-mediated block in differentiation, we used DEVD, which inhibits primarily caspase-3 activity. We observe that DEVD is unable to rescue the block in differentiation (Figure 4A), although it does promote cell survival as expected (data not shown). These results indicate that TNFα utilizes a caspase upstream of caspase-3 to mediate inhibition of differentiation. In contrast, the use of either pan-caspase inhibitors or the caspase-3 inhibitor on F3 cells does not affect their differentiation, nor their response to TNFα. This observation suggests that PW1-deficient cells do not activate caspases in response to TNFα.

Fig. 4. A specific role for caspases during TNFα-mediated inhibition of myogenic differentiation. (A) C2 cells cultured in DM suplemented with or without TNFα and caspase inhibitors, as indicated. Immunolocalization of myosin was used as a marker of differentiation. Quantitative analysis of myogenic differentiation (% differentiation) was performed as described in Materials and methods. Pan-caspase inhibitors BAF or z-VAD are able to rescue differentiation of C2 cells in the presence of TNFα, while the caspase-3 inhibitor DEVD is ineffective. In F3 cells, which are insensitive to TNFα, all the caspase inhibitors have no major effect upon differentiation. (B) Caspase activity (shaded bars) was measured in TNFα-treated C2 cells and expressed as fold increase versus controls (untreated C2 cells). To rule out cross-reactivity of the substrates with caspase-3, parallel experiments were carried out by incubating the cell cultures with DEVD-FMK before performing the caspase activity assay (solid bars). Only caspase activities that are significantly induced by TNFα (caspase-1, -5, -6, -8 and -9 in C2 cells) are shown. Significance was calculated using a one-sample t-test (p <0.05).

TNFα is believed to signal primarily through the cytokine caspase pathway, which involves caspase-8, whereas p53-mediated cell death signals through a bax-mediated pathway that leads to caspase-9 activation. Both caspases ultimately trigger the activation of caspase-3, which serves as a common nodal point in the cell death pathways (Woo et al., 1998). Since PW1 is involved in both signaling pathways, we wished to determine if one of these two pathways was preferentially activated. Our efforts using specific antibodies to activated forms of these caspases proved unsuccessful due to either lack of sensitivity or poor reactivity with murine caspases. It is also possible that the level of caspase activation triggered by TNFα in muscle cells is significantly lower than the levels that normally lead to cell death. Therefore we performed a biochemical analysis using fluorogenic substrates and assayed changes in the enzymatic rate of caspase activity. These assays reveal a significant increase in the activity of caspase-8 and -9 in C2 cells upon TNFα stimulation (Figure 4B). In contrast, no significant increase in caspase activities is seen in F3 cells in response to TNFα (data not shown). In addition, a variety of other caspases are also activated by TNFα in C2 cells and not in F3 cells, including caspase-1, -5 and -6 (Figure 4B). We focused our attention upon caspase-8 and -9 due to their direct involvement with the TNFα and p53 pathways, respectively.

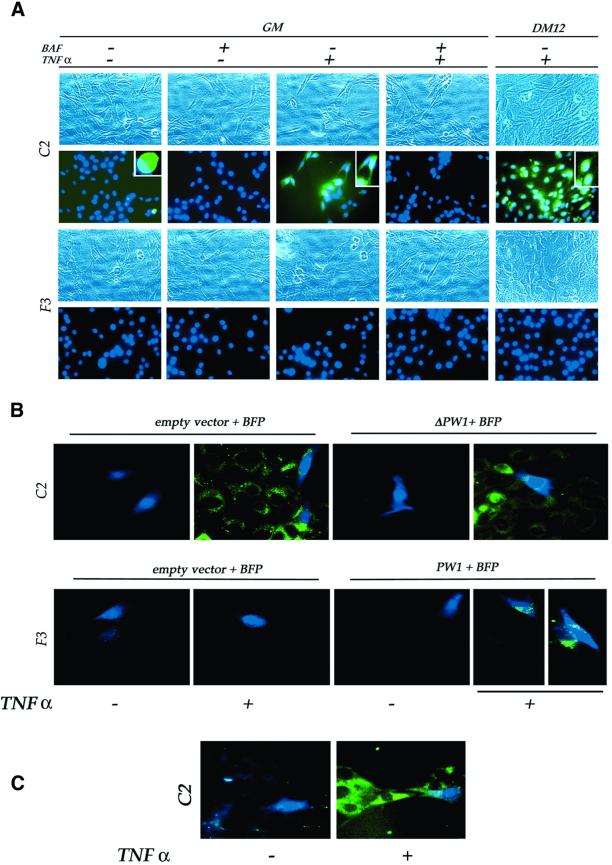

We wished to determine the status of caspase activation during normal differentiation and in response to TNFα in myogenic cells. Utilizing a fluorogenic caspase substrate, we observe little to no detectable caspase activity in either C2 or F3 cells at all stages of differentiation (Figure 5A). TNFα exposure elicits caspase activity in proliferating and differentiating C2 cells (Figure 5A). In contrast, F3 cells show no detectable caspase activity in response to TNFα (Figure 5A). We note that TNFα-induced caspase activity in C2 cells, detected by the fluorogenic substrate, is efficiently competed by pre-incubation of the cells with non-fluorogenic BAF substrate (Figure 5A).These results are consistent with the observation that TNFα blocks differentiation of C2 but not F3 cells, suggesting a role for caspases in the TNFα-mediated block in myogenesis. We note that almost all C2 cells are labeled by the fluorogenic substrate in response to TNFα; however, we do not see obvious signs of massive cell death. These data, combined with our observation that caspase inhibitors abrogate the ability of TNFα to block differentiation, lead to the conclusion that TNFα recruits the caspase pathway to act upon the myogenic program and not to activate cell death. Given the observations that C2 cells, but not F3 cells, activate caspases in response to TNFα, we tested whether F3 cells would become capable of activating caspases following forced expression of PW1. As shown in Figure 5B, C2 and F3 cells show a normal pattern of caspase activation following transfection with empty vector and BFP. Following transfection with PW1, F3 cells show caspase activation only when combined with TNFα. These data demonstrate that PW1 expression is sufficient to confer caspase activation in response to TNFα and provide a mechanistic basis for a role of PW1 in muscle cells. We further note that a truncated form of PW1 (ΔPW1), which has been previously demonstrated to block the ability of TNFα to activate NFκB in non-muscle cells, has no effect upon caspase activation in C2 cells (Figure 5B).

Fig. 5. PW1, but not NFκB, is necessary for TNFα-mediated caspase activation to occur. (A) Proliferating (GM) and differentiating (DM12) cells were subjected to caspase activation analysis (green) and the nuclei stained with Hoechst (blue). Each insert shows an enlarged portion of the corresponding picture. For each microscopic field, the corresponding phase contrast image is also shown. No caspase activity is detected in unstimulated cells (–TNFα), while TNFα (+TNFα) induces caspase activation, both in GM and DM, in C2 cells but not in F3 cells. Successful competition of the non-fluorescent caspase inhibitor (BAF) with the FITC-conjugated caspase substratum demonstrates the specificity of the assay. (B) Caspase activation analysis (green) in cells cotransfected as indicated and identified by the expression of the blue fluorescent protein (BFP, blue). Transfection (empty vector) does not affect caspase activation in C2 cells, both in the absence or presence of TNFα. A dominant-negative form of PW1 (ΔPW1), which inhibits NFκB activation by TNFα, does not affect TNFα-mediated caspase activation. F3 cells are unaffected by transfection procedure alone; however, PW1 expression (PW1) confers the ability to activate caspases when combined with TNFα treatment. (C) C2 cells expressing the NFκB super-repressor IκB show caspase activation upon TNFα treatment, confirming independence of caspase activation from NFκB activation. Data representative of at least two independent experiments are shown.

In order to test whether NFκB activation could affect the activation of caspases in TNFα-responsive cells such as C2, we transfected IκB super-repressor and measured fluorogenic caspase activity in the presence and absence of TNFα. We found that IκB-forced expression is not able to block caspase activity in C2 cells (Figure 5C), suggesting that the caspase activation does not lie downstream of the NFκB pathway in the TNFα response.

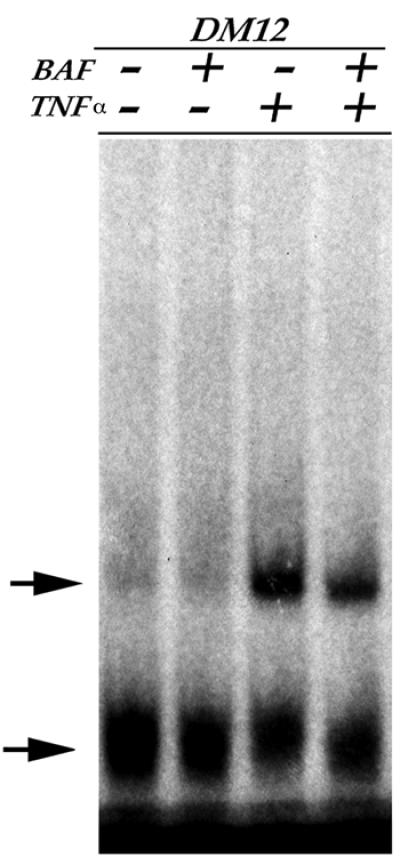

NFκB activation is independent of the caspase pathway

Since caspases can influence NFκB activity (Chaudhary et al., 2000; Hu et al., 2000; Kataoka et al., 2000) and the inhibition of NFκB can decrease TNFα-mediated inhibition of muscle differentiation (Guttridge et al., 2000; our unpublished results), we wished to determine whether caspases regulate the TNFα-mediated myogenic block through the regulation of NFκB or whether they function independently. We therefore examined NFκB activity in TNFα-treated myoblasts cultured in the presence or absence of caspase inhibitors. We find that caspase inhibitors do not abrogate TNFα-mediated NFκB activation even though cells differentiate under these conditions (Figure 6). These results demonstrate that caspase activity does not regulate the NFκB response in C2 cells but instead functions independently of NFκB in order to inhibit muscle differentiation.

Fig. 6. NFκB activation is not dependent on caspase activity. EMSA performed with a radiolabeled oligonucleotide containing a NFκB binding site on nuclear extracts from C2 (DM12) cultured in the presence or absence of a pan-caspase inhibitor (BAF) and/or TNFα. NFκB binding activity (upper arrow) is not dependent upon caspase activity, either in the presence or absence of TNFα. An aspecific band (lower arrow) and the unbound probe are also shown.

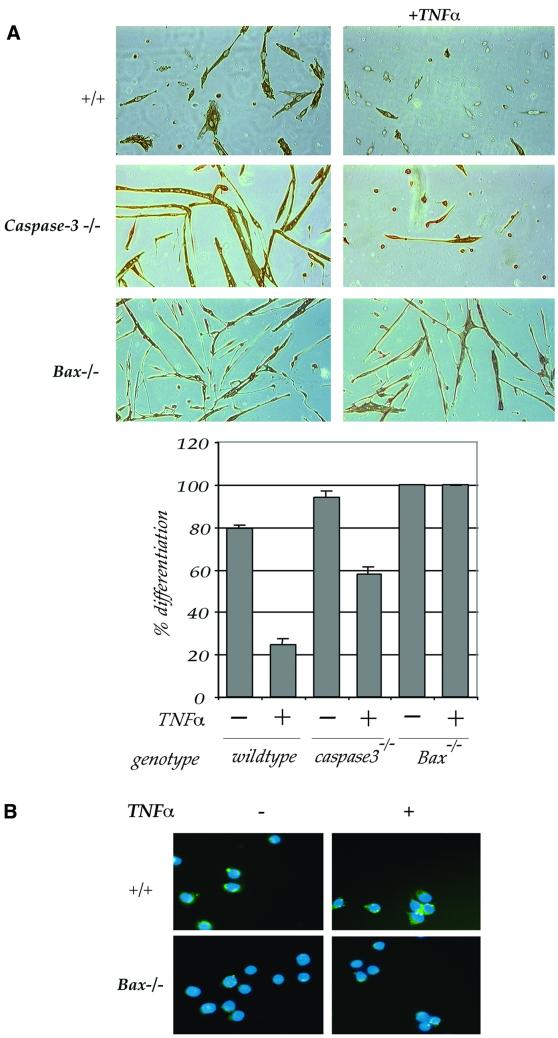

The bax-caspase pathway is required for TNFα-mediated inhibition of skeletal muscle differentiation

It has recently been demonstrated that PW1 can promote bax translocation, consistent with its role during p53-induced apoptosis (Deng and Wu, 2000). Primary myoblasts from bax-deficient mice were derived in order to determine whether TNFα signals through bax to inhibit differentiation. Bax-deficient myoblasts differentiate into myotubes and exposure to TNFα is unable to block differentiation (Figure 7A). In contrast, wild-type primary cells do not differentiate in the presence of TNFα as seen with the C2 myogenic cell line. These data indicate that bax participates in the TNFα signaling pathway in muscle cells and is required for TNFα-mediated inhibition of differentiation. Results obtained from our experiment with the DEVD inhibitor indicate that caspase-3 is not required for TNFα-mediated inhibition of differentiation. To confirm this, caspase-3-deficient myoblasts were derived and tested for their response to TNFα. Caspase-3-deficient myoblasts are unable to differentiate in the presence of TNFα, indicating that caspase-3 is not involved in mediating TNFα-induced inhibition of muscle differentiation (Figure 7A).

Fig. 7. TNFα-mediated caspase activation and inhibition of myoblast differentiation requires bax. (A) Photomicrographs of primary cultures from myogenic cells derived from wild-type (+/+), caspase-3- or Bax-deficient mice, cultured in DM in the absence or continuous presence of TNFα (+TNFα) and immunostained for myosin. Quantitative analysis of myogenic differentiation (% differentiation) reveals that while TNFα potently inhibits myogenic differentiation of both wild-type and caspase-3-deficient cells, it does not affect myogenic differentiation of Bax-deficient cells. (B) Caspase activation analysis (green) in wild-type (+/+) and Bax-deficient primary myoblasts. Nuclei were stained with Hoechst (blue). Bax-deficient cells are not responsive to TNFα in terms of caspase activity.

Our biochemical analyses did not distinguish between the caspase-8 and -9 pathways in the TNFα response in myoblasts. On the other hand, our results with bax-deficient myoblasts strongly point to the involvement of caspase-9, which is well documented to lie downstream of bax (Wei et al., 2001). Analysis of caspase activity in wild-type and bax-deficient myoblasts reveals strong caspase activation in wild-type myoblasts and only weak activity in bax-deficient myoblasts (Figure 7B). Taken together, we conclude that bax is a key component in the TNFα-mediated inhibition of differentiation and reveal that TNFα exposure of myogenic cells results in the recruitment of effectors, which normally act downstream of the p53 apoptotic pathway.

Discussion

An understanding of how TNFα affects skeletal muscle is an important problem in cancer biology. Muscle wasting associated with chronic diseases such as cancer can pose greater risk than the primary causative disease. The mechanisms underlying muscle wasting or cachexia may reflect the finding that myogenic cells are blocked in the differentiation process in the presence of TNFα (Miller et al., 1988; Szalay et al., 1997; Guttridge et al., 2000). A recent paper reported that caspase-1, -3, -6, -8 and -9 are activated in skeletal muscle of cachectic mice (Tisdale, 2001). In addition to activation of the cytokine-dependent caspases following TNFα exposure in vivo and in vitro, another major cellular response involves NFκB activation (Darnay and Aggarwal, 1997; Yeh et al., 1997; Relaix et al., 1998; Pomerantz and Baltimore, 1999), thus either one or both of these responses may be important in the specific case of myogenic cells.

PW1 was initially identified from a screen designed to isolate muscle regulatory factors expressed in undifferentiated myoblasts (Relaix et al., 1996). This screen was carried out using P2 myoblasts, which are derived from 10T1/2 cells following 5-azacytidine treatment. PW1 expression is abundant in all myogenic cell lines tested with the exception of F3 cells, which are also 10T1/2-derived myogenic cells. Yeast two-hybrid analysis revealed that PW1 strongly associates with TRAF2 and led to the observation that PW1 is a potent activator of NFκB (Relaix et al., 1998). A parallel study revealed that PW1 is also induced by p53 during p53-mediated apoptosis (Relaix et al., 2000). PW1 is also capable of inducing bax translocation, which is a critical early step in p53-mediated cell death (Deng and Wu, 2000). The participation of PW1 in these two pathways suggests that PW1 provides a mechanistic link between the cell death and NFκB pathways in response to TNFα. An additional link between these two pathways is provided by the fact that PW1 strongly associates with the Siah proteins, which participate in both p53-mediated growth arrest and cell death (Matsuzawa et al., 1998). Recently, we have demonstrated that the Siah proteins are able to participate in mediating NFκB activation (Polekhina et al., 2002). In this study, we demonstrate that TNFα-mediated inhibition of skeletal muscle differentiation is dependent upon caspase activity and that bax is required to mediate this response. Furthermore, we show that PW1 plays a pivotal role in mediating the TNFα response in muscle cells. F3 myogenic cells, which do not express PW1, do not show a block in differentiation in response to TNFα; however, forced-expression of PW1 is sufficient to confer TNFα sensitivity in these cells.

Recent studies have demonstrated that TNFα inhibits differentiation via activation of NFκB, which in turn downregulates MyoD and upregulates cyclin D1 (Guttridge et al., 1999, 2000). Likewise, we find that activators of NFκB inhibit muscle differentiation whereas NFκB inhibitors enhance differentiation (E.Yang, D.Coletti, G.Marazzi and D.Sassoon, manuscript in preparation). However, several observations suggest that TNFα-mediated inhibition of myogenic differentiation is not solely regulated by NFκB. First, F3 cells strongly activate NFκB but are not inhibited from differentiation in response to TNFα. Since other NFκB activators can inhibit F3 differentiation (E.Yang, D.Coletti, G.Marazzi and D.Sassoon, manuscript in preparation), their inability to respond to TNFα does not result from an intrinsic defect in the NFκB pathway. In fact, we see that while TNFα elicits a robust activation of NFκB in F3 cells, it does not lead to caspase activation. Conversely, in C2 cells, we observe that caspase inhibitors rescue myogenic differentiation, whereas TNFα-mediated NFκB activation is unaffected. Therefore, NFκB activation is not sufficient to inhibit differentiation in C2 cells in response to TNFα. Although we cannot exclude a role for NFκB in TNFα-mediated inhibition of skeletal muscle differentiation, our data suggest that other TNFα-mediated pathways such as caspase activation are critical and limiting. One notable difference between C2 and F3 cells is that F3 cells do not express detectable levels of PW1. Indeed, this difference in PW1 expression prompted us to compare the effects of TNFα in both cell lines.

Our data reveal that myogenic cells are blocked in differentiation by TNFα through the caspase pathway, which normally mediates cell death. A similar mechanism has been proposed to occur during erythropoiesis where caspase-dependent cleavage of GATA-1 prevents maturation (De Maria et al., 1999). In response to TNFα, C2 but not F3 myoblasts show caspase (i.e. caspase-1, -5, -6, -8 and -9) activation and are inhibited from differentiation. Furthermore, when caspase activity is blocked in C2 cells, TNFα can no longer inhibit skeletal muscle differentiation. We therefore conclude that TNFα-mediated activation of caspases in myoblasts is necessary for TNFα-mediated inhibition of muscle differentiation. This inhibition cannot be explained through a mechanism whereby TNFα selectively kills cell that are fated to differentiate. Indeed, the degree of cell death required to eliminate all differentiated cells would have resulted in a massive decline in cell number, which we do not observe. In addition, TNFα-mediated caspase activation does not inhibit differentiation through activation of NFκB, which still occurs in the presence of caspase inhibitors.

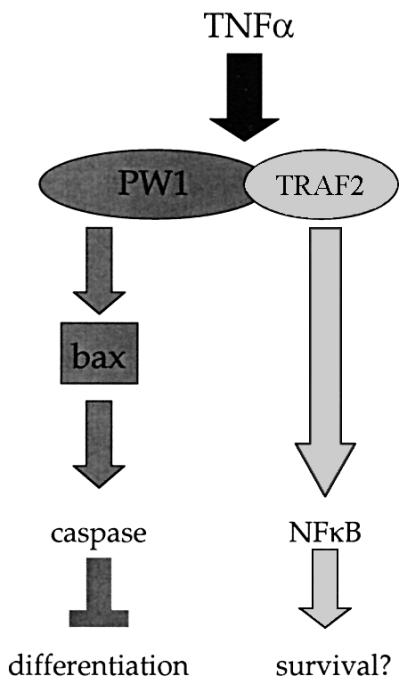

It has been shown that caspase-3 cleaves substrates important for muscle differentiation such as Rb and p21 (Tan and Wang, 1998; Suzuki et al., 2000). However, we find that caspase-3-deficient cells respond to TNFα, demonstrating that other caspases play a key role in inhibiting differentiation. It is unlikely that caspase-8 is involved since the DEVD inhibitor is not able to rescue TNFα-induced inhibition, even at high doses (100 µM; data not shown), which inhibits caspase-8 activity. The requirement of bax and our observation that caspase-3 mutant myoblast differentiation is blocked by TNFα strongly implicates caspase-9 as the key component in the TNFα response leading to a block in differentiation. An alternative model would be that a novel caspase pathway lies downstream of bax. Given the TNFα-mediated activation of caspase-1, -5 and -6 that we observe in C2 cells, we cannot rule out a role for these caspases. In muscle, bax expression is induced in dying as well as regenerating muscle, indicating that it may have a dual function in this tissue (Olive and Ferrer, 1999). Bax is thought to form ion-channels in the mitochondria, which in turn destabilize the outer mitochondrial membrane leading to mitochondrial dysfunction; this has been demonstrated to inhibit differentiation in skeletal muscle (Ichida et al., 1998; Rochard et al., 2000). Although the exact function of PW1 in the context of muscle cells has yet to be fully determined, our data strongly imply that PW1 functions to recruit components of cell death effectors normally associated with p53-induced cell death in response to TNFα. This mechanism may result from the ability of PW1 to induce bax translocation to the mitochondria (Deng and Wu, 2000). Consistent with this model (see Figure 8) is the observation that bax-deficient myoblasts do not respond to TNFα.

Fig. 8. Model for TNFα-mediated inhibition of myogenic differentiation. PW1 is required for caspase activation and associates with TRAF2 to mediate NFκB activation. Both PW1 and Bax are necessary for TNFα-mediated caspase activation and inhibition of differentiation. NFκB activation occurs in TNFα-exposed myogenic cells that do not express PW1 and does not effect myogenic potential, indicating that NFκB activation does not affect differentiation. Rather, our data with NFκB inhibitors suggest a role for NFκB in mediating cell survival.

Taken together, this study provides the first demonstration that TNFα signals through a bax/caspase pathway to influence the differentiation of muscle cells. In general, the bax/caspase pathway is not activated by cytokines such as TNFα, but is instead activated downstream of the p53 cell death pathway. PW1 is induced during p53-mediated cell death in fibroblasts and PW1 interacts with TRAF2. TNFα may engage the p53 cell death effector pathways through PW1 (Figure 8). We find that MyoD expression induces PW1 in 10T1/2 cells, thus MyoD may substitute for p53 in normal myogenic cells by maintaining the expression of PW1. Examination of MyoD-deficient myoblasts reveals almost a complete absence of PW1 expression compared with wild-type controls (M.Rudnicki, personal communication). The high expression levels of PW1 in muscle cells as compared with most other cell types may reflect the preferential sensitivity of skeletal muscle to the cachectic effects of TNFα. These data may have important implications for understanding the cellular and molecular processes underlying cachexia.

Materials and methods

Cells, culture conditions and transfection procedures

All cell lines (C2, 10T1/2, F3, P2 and 10RMD) were grown in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 15% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Hyclone Laboratories, Logan, UT) and 1 µg/ml penicillin/streptomycin (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) (GM). F3, P2 and 10RMD cell lines were provided by Dr A.Lassar (Harvard Medical School). Myogenic cells were differentiated by shifting the medium to DMEM supplemented with 2% horse serum and penicillin/streptomycin (DM). DNA was transfected into cells using FuGene 6 (Roche Molecular Biochemicals–Boehringer Mannheim, Indianapolis, IN) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The IκB, PW1 and ΔPW1 expression constructs have been described elsewhere (Relaix et al., 1998). Transfections were monitored using an expression construct for blue fluorescent protein (BFP; Quantum Biotechnologies, Laval, Canada). One day after transfection cells were replicate plated onto gelatin-coated coverslips, and 2 days after transfection the cells were treated with or without 20 ng/ml TNFα (Roche Molecular Biochemicals–Boehringer Mannheim) for 8 h in GM and/or an additional 12 h in DM. For differentiation experiments, TNFα was supplemented at 20 ng/ml in GM for 8 h before the cells were switched to 20 ng/ml TNFα in DM. Caspase inhibitors [z-VAD.fmk (benzyloxycarbonyl-Val-Ala-Asp fluoromethylketone), BOC-Asp.fmk or z-DEVD.fmk (Enzyme System Products, Livermore, CA)] were added at a concentration of 20 µM suspended in DMSO. DMSO alone was used for control experiments. The medium was changed daily.

Transgenic mice and generation of primary myoblasts

C57BL6 Bax-deficient mice were generously provided by Dr Ruth Slack (Knudson et al., 1995) and are now available from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME). Transgenic mice carrying a caspase-3 null mutation were obtained from Dr David S.Park (Kuida et al., 1996; Woo et al., 1998). Primary myoblasts were isolated from adult hindlimb muscle from 2- to 3-month-old mice as described previously (Megeney et al., 1996), including hepatocyte growth factor (10 ng/ml; Sigma) and heparin (5 ng/ml; Sigma) in GM for the first 48 h of culture; 2.5 ng/ml bFGF was added to GM thereafter. The primary cultures were maintained on collagen-coated dishes in Ham’s F10 (Gibco-BRL) supplemented with 20% FCS, 200 U/ml penicillin, 200 µg/ml streptomycin and 0.002% Fungizone (Invitrogen) (GM). All experiments were performed using cultures passaged less than 10 times. Differentiation medium for primary cultures (DM) consisted of DMEM supplemented with 5% horse serum and antibiotics as described above.

Northern blot analysis

Total RNA was isolated from cell lines using the RNAzol (TelTest Inc., Friendswood, TX) method. RNA samples (10 µg) were separated by electrophoresis on a denaturing 1.2% agarose/1.2% formaldehyde gel. Uniform loading of the gels was verified by hybridization with a probe to cytoskeletal actin (see below). RNA was transferred to a Nytran membrane (Schlecter & Schuell, Keene, NH) and baked for 2 h at 80°C. A cDNA probe corresponding to the terminal 900 bp for PW1 was used as described previously (Relaix et al., 1996). The probe for cytoskeletal actin was used as described elsewhere (Alonso et al., 1986). Northern blots were exposed for 1 week at –80°C. All labeling and washing conditions were as described previously (Relaix et al., 1996).

Immunohistochemistry and percentage of differentiation

Cells were grown on gelatin-coated glass, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde/PBS for 10 min at room temperature, and permeabilized in 0.1% Triton X-100. Following blocking reaction, the cells were incubated with PW1 antibody (Ab) or MF20 Ab at 4°C, overnight. The primary Ab was detected by biotinylated goat anti-rabbit Ab or biotinylated goat anti-mouse Ab, followed by streptavidine-conjugated horseradish peroxidase (HRP; Jackson Laboratories). Signal was detected using SigmaFast™ 3,3′ Diaminobenzidine (Sigma, St Louis, MO; DAB Peroxidase Substrate) following the manufacturer’s instructions. In other experiments, AlexaFluor568-conjugated anti-mouse Ab and AlexaFluor488-conjugated anti-rabbit Ab were used as secondary antibodies (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). Photomicrographs were obtained using a Zeiss Axiophot microscope fitted with a SPOT RT Slider camera (Diagnostic Instruments, Sterling Heights, MI). Quantitative analysis of differentiation was performed by determining the number of nuclei in MF20-positive cells within total nuclei in a microscopic field (% differentiation). At least 300 cells from a randomly chosen field were counted.

Caspase activity

In situ assay. Caspase activation was measured by CaspACE (FITC.VAD.fmk) in situ marker (Promega, Madison, WI) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, C2 and F3 cells were cultured in GM in the absence or presence of 20 ng/ml TNFα for 8 h and treated with FITC.VAD.fmk (10 µM) for 20 min to allow binding to activated caspases. After one wash with PBS, cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde/PBS for 20 min at room temperature in the dark. Nuclei were stained with 5 µM Hoechst 33258 (Roche Molecular Biochemicals–Boehringer Mannheim). Photomicrographs were obtained using a Zeiss Axiophot microscope fitted with a RT-slider spot camera (Diagnostic Instruments).

Enzymatic assay. Cells cultured in DM in the absence or continuous presence of 20 ng/ml TNFα were collected in lysis buffer as in Moriya et al. (2000). The cytosolic fraction was used to perform the enzymatic assay, while the nuclear pellet was used to measure DNA content as described previously (Labarca and Paigen, 1980). Ac-YVAD, 7-amino-4-trifluoromethyl coumarin (AFC) was used as caspase-1 substrate, Ac-WEHD-AFC as caspase-5 substrate, Ac-VEID-AFC as caspase-6 substrate, Ac-IETD-AFC as caspase-8 substrate, and Ac-LEHD-AFC as caspase-9 substrate (Biovision, Palo Alto, CA), after determining the optimal concentration for each substrate. The enzymatic reaction was performed in 10 mM PIPES pH 7.4, 2 mM EDTA, 0.1 % CHAPS, 5 mM DTT at 37°C, in Falcon 96-well white plates (BD, Pharmingen Franklin Lakes, NJ). Extract from cells cultured in the presence of the non-fluorogenic DEVD-FMK were used to rule out the possibility of non-specific cleavage of the AFC substrates by caspase-3. Fluorometric readings were performed over a 30 min period at a wave-length pair of 400/505 nm excitation/emission, using a Spectramax Gemini XS (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). Kinetic analysis (determination of Vmax) of AFC fluorescence was used to calculate enzymatic activity, which was normalized by DNA content and expressed as fold increase on the basal level (unstimulated cells). Statistical analysis was performed using software by the Statistical Computation Laboratory, University of Michigan (available on the web at http://www.stat.wmich.edu/slab/software).

Electrophoresis mobility shift assay (EMSA)

Nuclear extracts from cells were prepared as described previously (Andrews and Faller, 1991). For each sample, 6 µg of protein was combined with 10 fmoles of NFκB binding DNA probe (5′-AGT TGA GGG GAC TTT CCC AGG-3′; Promega, Madison, WI) labeled with [γ-32P]dATP (10 µCi, 6000 Ci/mmol, Perkin Elmer-NEN, Boston, MA) by use of T4 polynucleotide kinase, and then gel purified. For supershift EMSA, a monoclonal antibody against p65 (Sigma, St Louis, MO) was incubated with the nuclear extract for 30 min prior to the binding reaction. As a competitor, a 100× excess of cold probe was added to the binding buffer just before the radioactive probe. Complexes were resolved on a 5% polyacrylamide gel in 0.25× TBE at 6 mA, for 4 h at 4°C. The gels were dried and exposed on Biomax film with intensifying screen overnight.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Drs D.Park and R.Slack for the mutant mice used in this study, as well as E.Keramaris for genotyping the animals used for primary cultures. They also thank Dr M.Mericskay for critical reading of the manuscript. The work in this study was supported in part by a grant from the Muscular Dystrophy Association and American Heart Association, and NIH grant No. (NCI)-PO1-CA80058-01A1 DS (subproject) to D.S. D.S. is an AHA Established Investigator Award (Kenner Fellow). We also acknowledge support from NIH grant No. T32 HD07478 to E.Y.

References

- Alonso S., Minty,A., Bourlet,Y. and Buckingham,M. (1986) Comparison of three actin-coding sequences in the mouse; evolutionary relationships between the actin genes of warm-blooded vertebrates. J. Mol. Evol., 23, 11–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andres V. and Walsh,K. (1996) Myogenin expression, cell cycle withdrawal and phenotypic differentiation are temporally separable events that precede cell fusion upon myogenesis. J. Cell Biol., 132, 657–666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews N.C. and Faller,D.V. (1991) A rapid micropreparation technique for extraction of DNA-binding proteins from limiting numbers of mammalian cells. Nucleic Acids Res., 19, 2499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhary P.M., Eby,M.T., Jasmin,A., Kumar,A., Liu,L. and Hood,L. (2000) Activation of the NF-κB pathway by caspase 8 and its homologs. Oncogene, 19, 4451–4460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darnay B.G. and Aggarwal,B.B. (1997) Early events in TNF signaling: a story of associations and dissociations. J. Leukoc. Biol., 61, 559–566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Maria R. et al. (1999) Negative regulation of erythropoiesis by caspase-mediated cleavage of GATA-1. Nature, 401, 489–493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng Y. and Wu,X. (2000) Peg3/Pw1 promotes p53-mediated apoptosis by inducing Bax translocation from cytosol to mitochondria. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 97, 12050–12055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desagher S. and Martinou,J.C. (2000) Mitochondria as the central control point of apoptosis. Trends Cell Biol., 10, 369–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gartel A.L., Serfas,M.S. and Tyner,A.L. (1996) p21–negative regulator of the cell cycle. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med., 213, 138–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo K. and Walsh,K. (1997) Inhibition of myogenesis by multiple cyclin–Cdk complexes. Coordinate regulation of myogenesis and cell cycle activity at the level of E2F. J. Biol. Chem., 272, 791–797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guttridge D.C., Albanese,C., Reuther,J.Y., Pestell,R.G. and Baldwin,A.S.,Jr (1999) NF-κB controls cell growth and differentiation through transcriptional regulation of cyclin D1. Mol. Cell. Biol., 19, 5785–5799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guttridge D.C., Mayo,M.W., Madrid,L.V., Wang,C.Y. and Baldwin,A.S.,Jr (2000) NF-κB-induced loss of MyoD messenger RNA: possible role in muscle decay and cachexia. Science, 289, 2363–2366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hakem R. et al. (1998) Differential requirement for caspase 9 in apoptotic pathways in vivo. Cell, 94, 339–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halevy O., Novitch,B.G., Spicer,D.B., Skapek,S.X., Rhee,J., Hannon,G.J., Beach,D. and Lassar,A.B. (1995) Correlation of terminal cell cycle arrest of skeletal muscle with induction of p21 by MyoD. Science, 267, 1018–1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hengartner M.O. (2000) The biochemistry of apoptosis. Nature, 407, 770–776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu W.H., Johnson,H. and Shu,H.B. (2000) Activation of NF-κB by FADD, Casper and caspase-8. J. Biol. Chem., 275, 10838–10844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichida M., Endo,H., Ikeda,U., Matsuda,C., Ueno,E., Shimada,K. and Kagawa,Y. (1998) MyoD is indispensable for muscle-specific alternative splicing in mouse mitochondrial ATP synthase γ-subunit pre-mRNA. J. Biol. Chem., 273, 8492–8501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue J., Ishida,T., Tsukamoto,N., Kobayashi,N., Naito,A., Azuma,S. and Yamamoto,T. (2000) Tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor (TRAF) family: adapter proteins that mediate cytokine signaling. Exp. Cell Res., 254, 14–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Israel A. (2000) The IKK complex: an integrator of all signals that activate NF-κB? Trends Cell Biol., 10, 129–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaliman P., Canicio,J., Testar,X., Palacin,M. and Zorzano,A. (1999) Insulin-like growth factor-II, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase, nuclear factor-κB and inducible nitric-oxide synthase define a common myogenic signaling pathway. J. Biol. Chem., 274, 17437–17444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kataoka T. et al. (2000) The caspase-8 inhibitor FLIP promotes activation of NF-κB and Erk signaling pathways. Curr. Biol., 10, 640–648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knudson C.M., Tung,K.S., Tourtellotte,W.G., Brown,G.A. and Korsmeyer,S.J. (1995) Bax-deficient mice with lymphoid hyperplasia and male germ cell death. Science, 270, 96–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotler D.P. (2000) Cachexia. Ann. Intern. Med., 133, 622–634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuida K., Zheng,T.S., Na,S., Kuan,C., Yang,D., Karasuyama,H., Rakic,P. and Flavell,R.A. (1996) Decreased apoptosis in the brain and premature lethality in CPP32-deficient mice. Nature, 384, 368–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuida K., Haydar,T.F., Kuan,C.Y., Gu,Y., Taya,C., Karasuyama,H., Su,M.S., Rakic,P. and Flavell,R.A. (1998) Reduced apoptosis and cytochrome c-mediated caspase activation in mice lacking caspase 9. Cell, 94, 325–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuroiwa Y. et al. (1996) Peg3 imprinted gene on proximal chromosome 7 encodes for a zinc finger protein. Nature Genet., 12, 186–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labarca C. and Paigen,K. (1980) A simple, rapid and sensitive DNA assay procedure. Anal. Biochem., 102, 344–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y.P., Schwartz,R.J., Waddell,I.D., Holloway,B.R. and Reid,M.B. (1998) Skeletal muscle myocytes undergo protein loss and reactive oxygen-mediated NF-κB activation in response to tumor necrosis factor α. FASEB J., 12, 871–880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuzawa S., Takayama,S., Froesch,B.A., Zapata,J.M. and Reed,J.C. (1998) p53-inducible human homologue of Drosophila seven in absentia (Siah) inhibits cell growth: suppression by BAG-1. EMBO J., 17, 2736–2747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Megeney L.A., Kablar,B., Garrett,K., Anderson,J.E. and Rudnicki,M.A. (1996) MyoD is required for myogenic stem cell function in adult skeletal muscle. Genes Dev., 10, 1173–1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller S.C., Ito,H., Blau,H.M. and Torti,F.M. (1988) Tumor necrosis factor inhibits human myogenesis in vitro. Mol. Cell. Biol., 8, 2295–2301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moriya R., Uehara,T. and Nomura,Y. (2000) Mechanism of nitric oxide-induced apoptosis in human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells. FEBS Lett., 484, 253–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Natoli G., Costanzo,A., Guido,F., Moretti,F. and Levrero,M. (1998) Apoptotic, non-apoptotic and anti-apoptotic pathways of tumor necrosis factor signalling. Biochem. Pharmacol., 56, 915–920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olive M. and Ferrer,I. (1999) Bcl-2 and Bax protein expression in human myopathies. J. Neurol. Sci., 164, 76–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polekhina G., House,C., Traficante,N., Mackay,J., Relaix,F., Sassoon,D.A., Parker,M. and Bowtell,D.D. (2002) Siah ubiquitin ligase is structurally related to TRAF and modulates TNF-α signaling. Nature Struct. Biol., 9, 68–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pomerantz J.L. and Baltimore,D. (1999) NF-κB activation by a signaling complex containing TRAF2, TANK and TBK1, a novel IKK-related kinase. EMBO J., 18, 6694–6704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Relaix F., Weng,X., Marazzi,G., Yang,E., Copeland,N., Jenkins,N., Spence,S.E. and Sassoon,D. (1996) Pw1, a novel zinc finger gene implicated in the myogenic and neuronal lineages. Dev. Biol., 177, 383–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Relaix F., Wei,X.J., Wu,X. and Sassoon,D.A. (1998) Peg3/Pw1 is an imprinted gene involved in the TNF-NFκB signal transduction pathway. Nature Genet., 18, 287–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Relaix F., Wei,X., Li,W., Pan,J., Lin,Y., Bowtell,D.D., Sassoon,D.A. and Wu,X. (2000) Pw1/Peg3 is a potential cell death mediator and cooperates with Siah1a in p53-mediated apoptosis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 97, 2105–2110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter G. et al. (2001) TNF-α regulates the expression of ICOS ligand on CD34+ progenitor cells during differentiation into antigen presenting cells. J. Biol. Chem., 276, 45686–45693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rochard P., Rodier,A., Casas,F., Cassar-Malek,I., Marchal-Victorion,S., Daury,L., Wrutniak,C. and Cabello,G. (2000) Mitochondrial activity is involved in the regulation of myoblast differentiation through myogenin expression and activity of myogenic factors. J. Biol. Chem., 275, 2733–2744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki A., Kawano,H., Hayashida,M., Hayasaki,Y., Tsutomi,Y. and Akahane,K. (2000) Procaspase 3/p21 complex formation to resist fas-mediated cell death is initiated as a result of the phosphorylation of p21 by protein kinase A. Cell Death Differ., 7, 721–728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szalay K., Razga,Z. and Duda,E. (1997) TNF inhibits myogenesis and downregulates the expression of myogenic regulatory factors myoD and myogenin. Eur. J. Cell Biol., 74, 391–398. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan X. and Wang,J.Y. (1998) The caspase-RB connection in cell death. Trends Cell Biol., 8, 116–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tisdale M.J. (2001) Loss of skeletal muscle in cancer: biochemical mechanisms. Front. Biosci., 6, D164–D174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varfolomeev E.E. et al. (1998) Targeted disruption of the mouse Caspase 8 gene ablates cell death induction by the TNF receptors, Fas/Apo1 and DR3 and is lethal prenatally. Immunity, 9, 267–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh K. (1997) Coordinate regulation of cell cycle and apoptosis during myogenesis. Prog. Cell Cycle Res., 3, 53–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J., Guo,K., Wills,K.N. and Walsh,K. (1997) Rb functions to inhibit apoptosis during myocyte differentiation. Cancer Res., 57, 351–354. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei M.C. et al. (2001) Proapoptotic BAX and BAK: a requisite gateway to mitochondrial dysfunction and death. Science, 292, 727–730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woo M. et al. (1998) Essential contribution of caspase 3/CPP32 to apoptosis and its associated nuclear changes. Genes Dev., 12, 806–819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeh W.C. et al. (1997) Early lethality, functional NF-κB activation and increased sensitivity to TNF-induced cell death in TRAF2-deficient mice. Immunity, 7, 715–725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeh W.C. et al. (2000) Requirement for Casper (c-FLIP) in regulation of death receptor-induced apoptosis and embryonic development. Immunity, 12, 633–642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]