Abstract

Ca2+-ATPase of sarcoplasmic reticulum is an ATP-powered Ca2+ pump but also a H+ pump in the opposite direction with no demonstrated functional role. Here, we report a 2.4-Å-resolution crystal structure of the Ca2+-ATPase in the absence of Ca2+ stabilized by two inhibitors, dibutyldihydroxybenzene, which bridges two transmembrane helices, and thapsigargin, also bound in the membrane region. Now visualized are water and several phospholipid molecules, one of which occupies a cleft between two transmembrane helices. Atomic models of the Ca2+ binding sites with explicit hydrogens derived by continuum electrostatic calculations show how water and protons fill the space and compensate charge imbalance created by Ca2+-release. They suggest that H+ countertransport is a consequence of a requirement for maintaining structural integrity of the empty Ca2+-binding sites. For this reason, cation countertransport is probably mandatory for all P-type ATPases and possibly accompanies transport of water as well.

Keywords: ion pump, SERCA, protonation, Ca2+-ATPase, continuum electrostatic calculation

Ca2+-ATPase of skeletal muscle sarcoplasmic reticulum (SERCA1a), an integral membrane protein consisting of 994 aa (1), transfers two Ca2+ from the cytoplasm into the lumen of sarcoplasmic reticulum per ATP hydrolyzed and thereby establishes a >104 concentration gradient across the membrane (2). At the same time, Ca2+-ATPase pumps two or three H+ in the opposite direction (3-6) during the reaction cycle. According to the classical E1/E2 theory (7-9), transmembrane ion-binding sites have high affinity for Ca2+ and face the cytoplasm in E1, whereas they have low affinity and face the lumen of sarcoplasmic reticulum in E2. The opposite applies to H+, which binds to the ATPase in E2 and dissociates in E1, presumably in exchange with Ca2+. As Na+K+-ATPase and gastric H+K+-ATPase countertransport K+, instead of H+, countertransport of monovalent cations may be a common feature of the P-type ATPase superfamily (2, 10), of which SERCA1a is the best-studied member (11, 12). However, the sarcoplasmic reticulum membrane is leaky to monovalent cations including H+ (13). As has been pointed out before (14), the membrane potential and pH gradient must be minimized to achieve such a large concentration gradient of Ca2+. Therefore, the physiological role of H+ countertransport has been a puzzle. Although protonation of carboxyls in the Ca2+-binding site has been suggested from biochemical (15, 16) and mutagenesis studies (17, 18), crystal structures of SERCA1a in various states (19-24) did not clarify the role of countertransport or identify protonation sites.

These questions, however, can be addressed computationally by calculating stabilization energy provided by H+ binding (25-27). Protonation probability of a particular residue is related directly to the free energy difference between protonated and unprotonated forms. Such calculations, therefore, should be able to identify residues likely to be protonated in crystal structures and were indeed successful (28) for a Ca2+-bound form [E1·2Ca2+ (19); PDB ID code 1SU4]. As confirmed by all-atom molecular dynamics simulation (28), protonation of Ca2+-coordinating residues has an important structural role even in E1·2Ca2+. Such a computational approach requires accurate atomic models that include crystallographic water at least. The resolution (3.1 Å) of the published model for a Ca2+-unbound form [E2(TG); Protein Data Bank (PDB) ID code 1IWO (20)] was not good enough for this purpose, although the structure was stabilized by thapsigargin (TG), a very potent inhibitor (29). We now overcome this problem by stabilizing the transmembrane region with 2,5-di-tert-butyl-1,4-dihydroxybenzene (BHQ), in addition to TG. BHQ, commonly used as an antioxidant, is a high-affinity inhibitor (Kd = 20 nM) of Ca2+-ATPase and has a binding site distinct from TG (30). We show that BHQ bridges two transmembrane helices and sterically blocks the conformation changes of Glu-309 that works as the cytoplasmic gate of the ion pathway (18, 21, 24, 31), thereby fixing the pump in a H+-occluded state.

In the new 2.4-Å resolution structure, water and portions of several phospholipid molecules are resolved. Hence, electrostatic calculations could be applied reliably to yield atomic models with explicit hydrogens. These models show that phospholipids, water, and protons fill in space and compensate for the charge imbalance created by Ca2+ release. The models thus explain why H+ countertransport is required, although H+-gradient is dissipated by other means, and further suggest that water molecules might be transported together with H+.

Materials and Methods

Crystallization. Affinity-purified enzyme (32, 33) (20 μM) in octaethyleneglycol mono-n-dodecylether (C12E8) and 1 mM Ca2+ was mixed with 30 μM TG, 0.12 mM BHQ, and 3 mM EGTA, then dialyzed against a buffer consisting of 2.75 M glycerol, 4% polyethylene glycol 400, 3 mM MgCl2, 0.04 mM BHQ, 2.5 mM NaN3, 2 μg/ml butylhydroxytoluene, 0.2 mM DTT, 1 mM EGTA, and 20 mM Mes (pH 6.1) for ≈1 month. Crystals were grown to 300 × 300 × 50 μm and were flash-frozen in cold nitrogen gas.

Data Collection. Diffraction data were collected at BL41XU of SPring-8 (Hyogo, Japan) by using an R-Axis V imaging plate detector (Rigaku, Tokyo) and a Q315 charge-coupled device detector (Area Detector Systems Corporation, Poway, CA). Diffraction intensities from two best crystals were merged (Rmerge = 7.5%; I/σ = 29.3; redundancy = 10.6; 27.1%, 4.5, 5.7, respectively, for the highest-resolution bin, 2.5-2.4 Å) by using denzo and scalepack (34). The crystals had a P41 symmetry with the unit cell parameters of a = b = 71.39 Å, and c = 591.02 Å. One asymmetric unit contained two protein molecules.

Modeling. Because the unit cell parameters were identical to those of E2(TG) crystals (20), molecular replacement (35) was performed with the atomic model for the E2(TG) crystals (PDB ID code 1IWO) (20). Then, TG, BHQ, phospholipids modeled as PE, and water molecules were added. Many omit maps were calculated to examine the presence of water and phospholipid molecules. Several errors in the original model (1IWO), in particular the orientations of side chains, were corrected.

The final model included two protomers, virtually identical, each of which contains Ca2+-ATPase, TG, BHQ, Na+, three phospholipids, and 124 water molecules. It was refined against the diffraction data consisting of 113,814 reflections (99.9% completeness) to Rfree of 0.263 and Rcryst of 0.239 at 2.4-Å resolution; rms deviation of the bond length and angle were 0.008 Å and 1.3°, respectively.

Recombinant ATPase Expression and Mutagenesis. The chicken fast muscle SERCA-1 cDNA (36) was subcloned into the SV40-pAdlox vector and transfected into COS-1 cells for overexpression of protein under control of the SV40 promoter. COS-1 cell cultures and transfection methods were described by Sumbilla et al. (37). For site-directed mutagenesis, primers of 20-30 bp in length were synthesized for each individual mutation. These primers were used to hybridize DNA sequences internal to the flanking primers and were used for PCR mutagenesis by the overlap extension method (38). Briefly, two overlapping fragments containing the mismatched bases of the targeted sequence were amplified in separate PCRs. The reaction products were then mixed and amplified by PCR using both flanking primers. The mutant cassette then was exchanged with the corresponding cassette of wild-type cDNA in SV40-pAdlox, which was used for transfection into COS-1 cells and expression of the mutant protein.

Functional Studies. The microsomal fraction of transfected COS-1 cells was obtained by differential centrifugation of homogenized cells (37). Immunodetection of expressed ATPase in the microsomal fraction was obtained by Western blotting. SERCA ATPase activity was assayed in a reaction mixture containing 20 mM Mops (pH 7.0), 80 mM KCl, 3 mM MgCl2, 10 μM free Ca2+, 5 mM sodium azide, 50 nM Ca2+-ATPase, 3 μM ionophore A23187, 3 mM ATP, and 0-10 μM TG. Ca2+-independent ATPase activity was assayed in the presence of 2 mM EGTA without added Ca2+. The reaction was started at 37°C by adding ATP, and samples were taken at serial times for determination of Pi (39). The Ca2+-dependent activity was calculated by subtracting the Ca2+-independent ATPase activity from the total ATPase activity and was corrected to account for the level of expressed protein in each microsomal preparation as revealed by immunoactivity and with reference to microsomes obtained from COS-1 cells transfected with wild-type SERCA1 cDNA.

Continuum Electrostatic Calculation. In continuum electrostatic calculations, protonation probability of a residue is obtained from the difference between ΔGpro and ΔGsol, which are free energy differences (ΔG) between protonated and unprotonated states of the residue in protein and in solution, respectively. ΔG is related to the equilibrium between protonated (AH) and unprotonated (A-) forms of the residue (A) as

|

The mead program suite (40) used here solves a finite-difference Poisson equation, assuming continuum dielectric for the interior and exterior of a protein, to evaluate the protonation probability. The program allows, however, only two regions of different dielectric constants (ε) for a whole system. For the bulk solvent, ε of 80 was used. This assignment leaves only one dielectric constant to be assigned to the rest, including lipid bilayer modeled as a slab of 30-Å thickness. Because the residues of concern are all within the bilayer, ε of 4 appeared most appropriate. However, to examine the robustness, all of the calculations were done also with ε = 20.

At first, the probabilities for all 30 titratable residues around the transmembrane Ca2+-binding sites (Fig. 1) were calculated to find the residues that exhibited large differences between the E1·2Ca2+ and the E2 states. At this stage, atomic charges of the titratable residues were adjusted rather than explicitly adding protons, because positions of protons strongly affected protonation probabilities, and the positions of protons refined by energy minimization were highly dependent on the initial (inevitably incorrect) positions. These calculations identified four such residues (Glu-58, Glu-309, Glu-771, and Asp-800) and Glu-908, protonated in both states, as target residues for more accurate calculations with explicit protons. For this purpose, the residues that could affect the protonation states of the target residues were identified by calculating protonation probabilities by using only the target residues. A significant difference from that obtained with all 30 residues was found only with Glu-58 in E2. Conversely, calculations with nine residues that included four acidic residues surrounding Glu-58 (Glu-55, Asp-59, Asp-254, and Glu-258; see Fig. 1) yielded identical results with those including all 30. Hence, the final calculations were done by using these nine residues with explicit protons added.

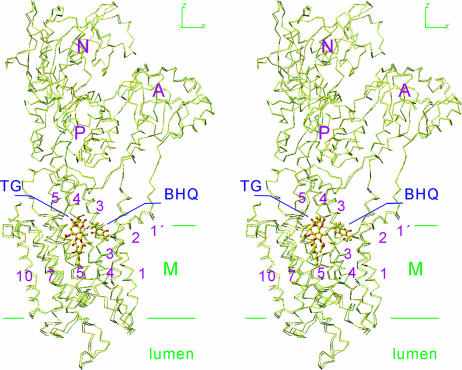

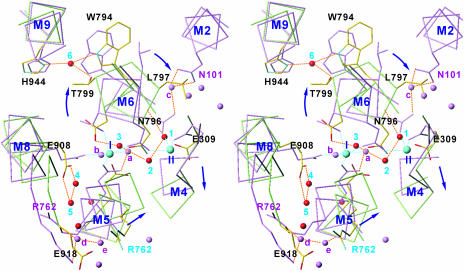

Fig. 1.

Structural model and the locations of 30 titratable residues around the Ca2+-binding sites in E1·2Ca2+ (Left) and E2 (Right), as used in continuum electrostatic calculations. Ca2+-ATPase and the lipid bilayer (modeled as a slab of 30-Å thickness) were treated as a single low dielectric object (ε = 4 or 20; yellow), and the solvent was treated as a high dielectric object (ε = 80; light blue). Two purple spheres show bound Ca2+, and cyan and red dots represent ionizable and protonatable residues, respectively. Nine residues (E55, E58, D59, D254, E258, E309, E771, D800, and E908) examined with explicit protons are circled. Each image is an enlarged view of the boxed area in the Inset, in which the entire model is shown.

In all of the calculations, a two-step focusing procedure implemented in mead was used for minimizing calculation costs. First calculations were done on a grid of 341 × 341 × 341 points for evaluating ΔGpro and on a grid of 121 × 121 × 121 points for ΔGsol. In either case, a grid size of 1.0 Å was used. Second calculations for ΔGpro and ΔGsol were done both on a grid of 71 × 71 × 71 points at 0.25-Å interval, which was centered at the target residue. All hydrogen atoms were added by using molx, a utility program in the marble software package (41). Their positions were refined by energy minimization and molecular dynamics simulations with marble (41), keeping protein heavy atoms fixed.

Continuum electrostatic calculations were tried also with mcce (42), which allows multiconformers for titratable residues but treats lipid bilayer as a part of bulk solvent (i.e., ε = 80). Because multiconformer calculations were not essential as demonstrated by molecular dynamics simulations (see below) and because several critical residues are located near the protein-lipid interface, we did not use this program primarily. The results were, however, virtually the same as those obtained with mead and are not described here.

Results

Structure Determination and Phospholipids. In this study, we generated crystals of Ca2+-ATPase in the absence of Ca2+ stabilized with BHQ alone [E2(BHQ)], TG alone [E2(TG)], and BHQ plus TG [E2(TG+BHQ)]. To generate the crystals, affinity-purified Ca2+-ATPase in the presence of Ca2+ was supplemented with exogenous phosphatidylcholine, mixed with EGTA and the inhibitors, and then dialyzed against a crystallization buffer (20). Inclusion of two inhibitors in crystallization improved the resolution to 2.4 Å, with no changes in unit cell parameters from E2(TG). Therefore, the atomic model was built by molecular replacement starting from the model for E2(TG) [PDB ID code 1IWO (20)] and refined to Rfree of 26.3% at 2.4-Å resolution. BHQ alone yielded crystals of the same symmetry but with slightly different unit cell parameters. The resolution of the E2(BHQ) crystals was limited to 3.0 Å, and the structure of the ATPase was virtually the same as those of E2(TG+BHQ) and E2(TG), including the paths of the M3 and M7 helices that constitute the main part of the TG-binding pocket (Fig. 2). Therefore, we describe here the crystal structure of E2(TG+BHQ) only. Although side-chain conformations of some residues were corrected for, paths of the main chain were virtually identical to the published model of E2(TG) (rms deviation = 0.57 Å for Cα atoms). With the E2(TG+BHQ) crystals, temperature factors of the residues in the transmembrane region (average ≈ 55) were even smaller than those (average ≈ 80) in the E2·MgF42- crystals (22) that diffracted to 2.3-Å resolution. The ATPase in the E2·MgF42- crystals is thought to be in a state analogous to E2·Pi, stabilized with MgF42-, a stable phosphate analog, as well as TG. Positions of water molecules observed in the Ca2+-binding sites were very similar to those in E2·MgF42- (PDB ID code 1WPG), but one more water molecule with a large temperature factor was identified around Glu-908.

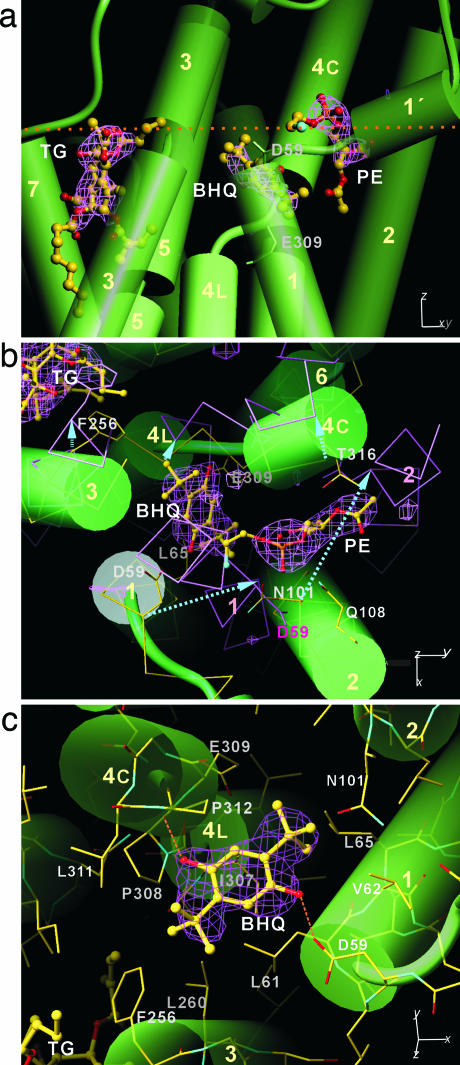

Fig. 2.

Superimposition of two E2 structures viewed in stereo. Yellow, E2(BHQ); light green, E2(TG) (PDB ID code 1IWO). Atomic models of TG and BHQ are shown in ball-and-stick. Transmembrane helices and three cytoplasmic domains are labeled.

A difference Fourier map (Fig. 3) calculated after refining the atomic model without BHQ and phospholipids showed two clear extra densities present near Glu-309. The one closer to the middle of the membrane had a tri-partite structure, exactly matching BHQ (Fig. 3). Slightly above this density, there was another peak with a shape characteristic of the head group of a phospholipid, which was tentatively modeled as phosphatidylethanolamine. Electron density was clear to the carbonyl groups (Fig. 3). Because only phosphatidylcholine was added exogenously, phosphatidylethanolamine probably remained from the native membrane (43). Its location in the V-shaped cavity between the M2 and M4 helices (Figs. 3b and 4d) suggests that it acts as a wedge to keep those helices apart in E2. In fact, although somewhat weaker, clear electron densities were present at the same position in the maps of E2(TG) (Fig. 4b) and E2(BHQ). However, no corresponding electron density was present in the map of E2·MgF42- (Fig. 4c), apparently reflecting a narrower cleft (Fig. 4d). There is no such a cavity in E1·2Ca2+ (Fig. 3b) (19). Thus, this lipid molecule is likely to move into this position during the E2P → E2 transition to stabilize the ground E2 state and move out in E2 → E1·2Ca2+ in the normal reaction cycle. As the acyl chains of this lipid molecule would collide with M2 in E1·2Ca2+ (Fig. 3b), such movements are expected.

Fig. 3.

Locations of two transmembrane inhibitors and a phospholipid in the crystal structure of Ca2+-ATPase in E2(TG+BHQ). (a) Side view. (b) Top view. (c) Details of BHQ interaction. Violet nets represent an Fo - Fc map, showing extra electron densities that cannot be explained by Ca2+-ATPase. The map was calculated at 2.4-Å resolution and contoured at 4σ in a or 3.5 σ in b and c, before introducing BHQ and lipid into the model. The map of TG is shown for indicating the expected level of electron density. Atomic models of a BHQ and a phospholipid [modeled as phosphatidylethanolamine (PE)] are shown in ball-and-stick; Cα traces of Ca2+-ATPase, together with a few side chains, appear in b as yellow [E2(TG+BHQ)] and violet (E1·2Ca2+) sticks. In c, atomic model of E2(TG+BHQ) (atom color) is shown. Cylinders represent transmembrane helices (numbered). Dotted line in a indicates approximate position of the cytoplasmic boundary of the hydrophobic core of the lipid bilayer. Arrows in b indicate the movements of transmembrane helices in the transition E2(TG+BHQ) → E1·2Ca2+.

Fig. 4.

Fo - Fc maps for three different E2 structures around the cleft between M4 and M1-M2 helices. The maps are calculated at 2.4-Å resolution and contoured at 3.5σ [a and d, E2(TG+BHQ)], 3.1 Å and at 2.5σ [b, E2(TG) (20)], and 2.3 Å and at 2.5σ [c, E2·MgF42- (22)] before introducing phospholipids into the model. Structures are viewed along the membrane plane. Atomic models for BHQ and phosphatidylethanolamine (up to carbonyl groups) at the expected positions are superimposed. In d, models of E2(TG+BHQ) and E2·MgF42- are superimposed and viewed from the right in a; Asn-101 side chain in E2·MgF42- would collide with the phospholipid located at the position found in E2(TG+BHQ) or E2(TG).

Presumably to facilitate such movements, the phosphate moiety of this lipid molecule is not stabilized by any hydrogen bonds; Gln-108 and Thr-316 are the closest polar residues but are >3.5 Å away (Fig. 3b). There are no nearby Arg or Lys residues that could make salt bridges to stabilize the phosphate moiety, as observed with many phospholipids found in crystals of other membrane proteins [e.g., cytochrome bc1 complex (44)]. The electron density map showed hints of phospholipid molecules at other places, but only two more were identified with certainty. They were located between neighboring protein molecules in the crystal lattice and were common to the maps of E2(TG), E2(BHQ), and E2(TG+BHQ).

BHQ Binding Site and Mode of Binding. BHQ binds to the ATPase by bridging the M1 and M4 helices with hydrogen bonds involving the two hydroxyl groups of BHQ, one with the carboxyl of Asp-59 on M1 and the other with the carbonyl of Pro-308 on M4 (Fig. 3c). The positions of M1 in E2(TG+BHQ), E2(BHQ), and E2(TG) are identical (Figs. 2 and 4), showing that BHQ stabilizes an E2 conformation the same as E2(TG). A clear difference from the published model of E2(TG), however, is that the Glu-309 side chain points toward the Ca2+-binding sites (see below). BHQ fixes this side-chain conformation of Glu-309 by occupying the space that would be necessary for the side chain to point outwards (Fig. 3c). Because Glu-309 works as the gating residue for cytoplasmic Ca2+ to reach the binding cavity (18, 21, 24, 31), Ca2+ cannot pass if BHQ is present. Thus, this situation is reminiscent of those in E1·AMPPCP and E1·AlFx·ADP (21, 24), in which Leu-65 on M1 blocks the conformation changes of the Glu-309 side chain to occlude Ca2+. Here BHQ presumably occludes H+ by the same mechanism.

Hydroxyl groups of BHQ thus are expected to have vital roles in the compound's inhibitory action, as demonstrated by a weaker inhibition with the Asp-59 → Ala mutant (Fig. 5; see also Table 1, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). However, its butyl groups appear more critical because our mutation study shows a much stronger effect with the Leu-311 → Ala mutant (Fig. 5). Fig. 3c shows that BHQ makes extensive van der Waals contacts with M1 and M4 helices: the butyl group on the M4 side fits in the space between Pro-308 and Pro-312, and contacts Leu-61 and Leu-311; the other butyl group on the M1 side contacts Leu-61, Val-62, and Leu-65. These results are consistent with a previous study (30) that examined derivatives of BHQ, which showed that hydroxyl groups are important, but the affinity is changed nearly 10,000-fold by replacing the butyl groups with amyl or propyl groups. The binding site of BHQ is thus distinctly different from that of TG, which binds to the groove surrounded by M3, M5, and M7 (20). In fact, Phe-256 on M3 is critical for binding of TG (45, 46) but has only small effects for BHQ (Fig. 5 and Table 1). Nevertheless, the effects of BHQ, such as inhibition of E2P formation by Pi, are very similar to those of TG (30, 47). At present, we do not understand why these two inhibitors have such similar effects.

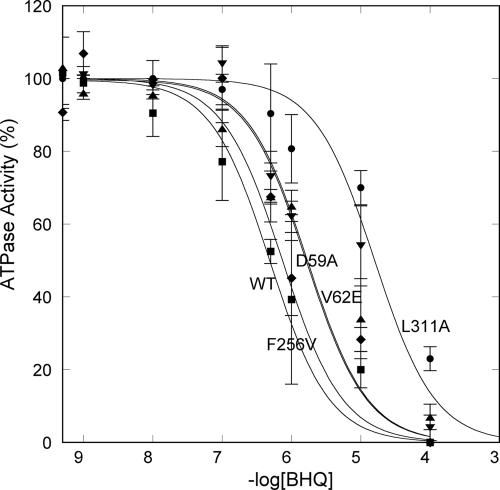

Fig. 5.

Inhibition by BHQ of various mutants. Effects of various mutations on the BHQ concentration dependence of ATPase inhibition are shown. Squares, wild type; diamonds, F256V; triangles, V62E; inverted triangles, D59A; circles, L311A. Mutations of Pro-308 and Pro-312 also were tried but interfered with protein expression. See Table 1 for the numbers deduced from this figure.

Conformation of Glu-309. It is now well established that Glu-309, which caps site II Ca2+ (19), works as a cytoplasmic gate by changing the side-chain conformation. With BHQ present, the Glu-309 side chain points inwards and forms hydrogen bonds with the Asn-796 side chain and the Val-304 carbonyl (Fig. 6b). The latter requires protonation of Glu-309 (see below). Asn-796 provides the two protons of the side-chain amide to Glu-771 and Glu-309 (Fig. 6b). Therefore, this Asn is critical and is changed to Asp in Na+K+-ATPase and H+K+-ATPase that countertransport (and coordinate) K+ instead of H+.

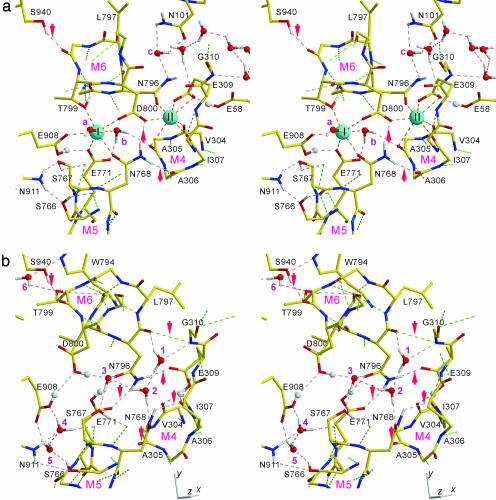

Fig. 6.

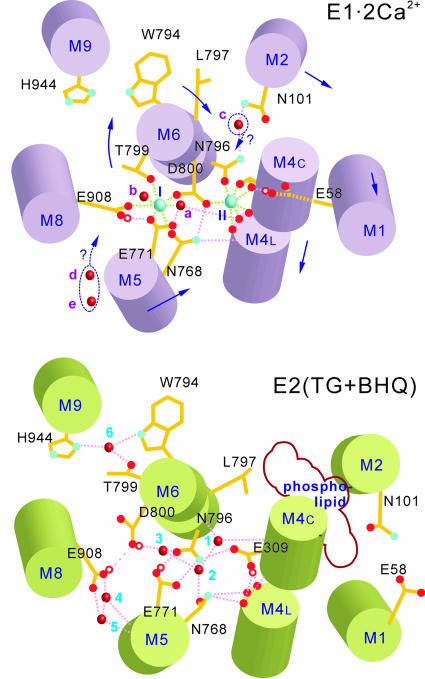

Atomic models of the Ca2+-binding sites with explicit hydrogens viewed approximately perpendicular to the membrane from the cytoplasmic side. Identical region is shown in stereo. (a)E1·2Ca2+ (PDB ID code 1SU4). (b) E2(TG+BHQ). Side chains are shown only for residues that involved in hydrogen bonds or Ca2+-coordination. Hydrogen atoms are shown only for water, Asn, Thr, and protonated carboxyls. Small white spheres represent bound protons, and red ones represent water. Cyan spheres (marked I and II) in a represent bound Ca2+. Broken lines show hydrogen bonds and Ca2+ coordination. Hydrogen bonds between main-chain atoms are in green. Interhelix hydrogen bonds are marked with arrows. The figure was prepared with molscript (50).

At 2.4-Å resolution, the main-chain conformation of Glu-309 is unambiguous. Its peptide bond is flipped (the difference in Ψ angle of Glu-309 is 168°) from that in the E1·2Ca2+ state. In E2(TG+BHQ), Glu-309 takes a helix conformation, whereas in E1·2Ca2+ it is in a β-strand conformation. To allow this conformation change, the carbonyl group of Glu-309 is not fixed by hydrogen bonds with protein atoms in either E1·2Ca2+ or E2(TG+BHQ); only the amide group makes a hydrogen bond with the Ile-307 carbonyl in E2(TG+BHQ) but with nonoptimal geometry (Fig. 6b). However, the Gly-310 amide makes a hydrogen bond with the Asn-796 carbonyl (Fig. 6b), which, in E1·2Ca2+, makes a hydrogen bond with Asp-800 on the same M6 helix (Fig. 6a). As a result, the distance between Pro-308 and Pro-312 is 2.5 Å shorter in E2(TG+BHQ), and the orientation of the luminal half of M4 is changed by ≈15° with respect to the cytoplasmic half. These changes are probably needed to allow the movements of M4 perpendicular to the membrane plane (20) (Fig. 7). Similar changes take place at Asp-703 (G703DG), which binds Mg2+ and undergoes large conformation changes between phosphorylated (or γ-phosphate bound) and unphosphorylated forms (21, 24). This kind of peptide bond flipping is not uncommon (48) and is observed frequently in molecular dynamics simulations [e.g., for Val-76 preceding Gly-77 in a K+-channel (49)].

Fig. 7.

Superimposition of the Cα-traces of E2(TG+BHQ) (green) and E1·2Ca2+ (violet) around the Ca2+-binding sites, viewed in stereo. Water molecules are represented by small spheres in red (E2(TG+BHQ); 1-6) and violet (E1·2Ca2+; a-e). Ca2+ in E1·2Ca2+ appear as cyan spheres (marked I and II). Side chains [atom color for E2(TG+BHQ) and violet for E1·2Ca2+] are shown for some of the residues that may be involved in moving water or binding Ca2+. Arrows shows the movements of the transmembrane helices in the transition E1·2Ca2+ → E2(TG+BHQ). Orange broken lines represent hydrogen bonds, and cyan lines show Ca2+-coordination.

Water Molecules in the Ca2+-Binding Sites. This higher-resolution structure allows deeper understanding of the E2 structure and E1-E2 transition: movements of water molecules and changes in protonation of carboxyl groups play important roles here. For example, compared with E1·2Ca2+, the part of M6 between Asn-796 and Asp-800 is rotated nearly 90°, so that Asn-796 approaches Glu-771 on M5 (Figs. 7 and 8) (20). At the same time, the Asn-796 carbonyl changes its hydrogen-bonding partner from the Asp-800 amide to that of Gly-310 (on M4) and a water molecule (Fig. 6). The short distance (2.7 Å) between the two juxtaposed oxygen atoms of Asn-796 and Glu-771 side chains clearly requires protonation of the Glu-771 carboxyl, and the formation of a hydrogen bond (Fig. 6b). The rotation of M6, stabilized by the interhelix hydrogen bonds with residues in M4, M5, and M9 (Fig. 6b, arrows), creates a larger space around the Trp-794 side chain near the luminal surface (Fig. 7). Now a water molecule (6 in Figs. 6, 7, 8) occupies that space, forming hydrogen bonds with Trp-794, Thr-799, and His-944 side chains (Figs. 7 and 8). Thus, this water molecule may work as a lock of the rotated configuration of the M6 helix.

Fig. 8.

Schematic representation of the Ca2+-binding sites in E1·2Ca2+ and E2(TG+BHQ). Cyan spheres represent Ca2+; red ones represent water. Bound protons appear as red circles. Arrows indicate the movements of transmembrane helices in the transition E1·2Ca2+ → E2(TG+BHQ). Dotted arrows indicate potential movements of water molecules. Dotted pink lines indicate hydrogen bonds, and those in light green indicate Ca2+ coordination. Labeling of water molecules follows Figs. 6 and 7.

In the E1·2Ca2+ crystal structure (PDB ID code 1SU4), only two water molecules (a-b, in Figs. 6, 7, 8) are present in the Ca2+-binding cavity and coordinate site I Ca2+. In E2(TG+BHQ), five water molecules (1-5 in Figs. 6, 7, 8) are identified, filling the space created by Ca2+ release. Three water molecules (1-3) are located near the positions taken by two Ca2+ (cyan spheres in Figs. 6 and 7) in E1·2Ca2+. They are likely to be hydrogen bonded to one another and to link transmembrane helices. A water molecule (1 in Figs. 6, 7, 8) near Gly-310 amide (M4) is connected with Asn-796 carbonyl (M6) and another water molecule (2) hydrogen bonded to Asn-768 (M5); this latter water, in turn, is linked to another (3) that forms hydrogen bonds with Asn-796, Asp-800 (M6), and Ser-767 (M5) (Fig. 6b). Water molecules 4 and 5 (Figs. 6, 7, 8) are detached from others and located near Glu-908 carboxyl, filling the space between M5 and M8 created by the bending of M5 above Gly-770 during Ca2+ release (20) (Fig. 7). These two are likely to be hydrogen bonded to Glu-908 and Ser-766 (Fig. 6b).

Protonation in the Empty Ca2+-Binding Sites. Ca2+ release creates not only empty space, it also causes severe charge imbalance. The four carboxyl groups clustered in the Ca2+-binding sites are likely to be deleterious to structural integrity if left ionized. If no metal binding is allowed, such imbalance must be compensated for by the formation of hydrogen bonds with other residues following conformation changes, by the introduction of water molecules, or, more directly, by protonation. To understand how Ca2+-ATPase handles this problem, we generated atomic models with explicit hydrogens by applying continuum electrostatic calculations (25). These calculations estimate protonation probability by evaluating free energy difference between protonated and unprotonated forms of selected residues for all possible combinations of protonation states. Of the 30 protonatable/ionizable residues examined (Fig. 1), the calculations show that only 4 transmembrane residues, Glu-771, Asp-800, Glu-309, and Glu-908 will be protonated (in descending order of probability; see Table 2, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site) in E2(TG+BHQ). If we assume ε = 4, for all four of them, protonation probabilities are >99% (gain in free energy by protonation is >11 kcal/mol; see Table 2) for pH 6-8. If we assume ε = 20, the protonation probabilities for three of them do not change much, but that of Glu-908 decreases and is pH-dependent; at pH 8, it is reduced to ≈20% (see Table 3, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site).

In most cases, the requirement for the protonation of these residues can be inferred from the atomic model, because oxygen atoms are juxtaposed within a hydrogen-bond distance (e.g., 2.6 Å between Glu-309Oε2 and Val-305 carbonyl). Such a close distance will be allowed only when a hydrogen bond is formed between them. In fact, the locations of hydrogens and protons shown in Fig. 6 are uniquely determined by this requirement, making multiconformer calculations for titratable residues (e.g., ref. 42) unnecessary. To further examine the stability of the proposed atomic model, molecular dynamics simulations were performed for E2, as was already done for E1·2Ca2+ (28). The system was stable at least for 2.6 nsec with the arrangements of water and hydrogens shown in Fig. 6b.

As listed in Table 4, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site, the 12 protein oxygen atoms used for Ca2+ coordination in E1·2Ca2+ are now involved in 15 hydrogen bonds, 5 with protein amide, 5 with water, and 5 with bound protons (Fig. 6b). As a result, there are more interhelix hydrogen bonds in E2(TG+BHQ) than in E1·2Ca2+ (arrows in Fig. 6). In fact, almost all carboxyl and carbonyl oxygen atoms within the transmembrane region of E2(TG+BHQ) are involved in hydrogen bonds or are protonated. One of the exceptions is the carbonyl of Leu-797, located in the part of M6 that undergoes a large rotation (20) (Fig. 7). The unprotonated carboxyl oxygen of Asp-800 appears to form a weak hydrogen bond with the hydrogen of Val-795 Cβ. Protonation could occur on this oxygen, if water 3 (Fig. 6b) were H3O+, but there is no oxygen atom that could form a hydrogen bond with that proton.

Proton Countertransport. From this explicit model of the hydrogen-bonding network for E2(TG+BHQ), we can now address questions on proton countertransport by Ca2+-ATPase. In E1·2Ca2+, as described in ref. 28, only Glu-58 and Glu-908 are expected to be protonated in the transmembrane region (Table 2). Thus, four residues are likely to be protonated in E2, and two are likely to be protonated in E1·2Ca2+. Nevertheless, we cannot derive the number of H+ countertransported during the reaction cycle because it depends on the side (i.e., cytoplasmic or luminal) from which protons are introduced into the binding sites.

Because all of the residues protonated in E2(TG+BHQ) coordinate Ca2+ in E1·2Ca2+, it is most likely that all of them are introduced from the luminal side during Ca2+-release. However, ambiguity remains with Glu-58, which is hydrogen bonded to Glu-309 in E1·2Ca2+ but is located in the cytoplasm in E2. If the proton that appears on Glu-58 in E1·2Ca2+ binds from the cytoplasmic side (model 1), it will not affect the number of protons countertransported, which is three in this case. However, if that proton comes from the luminal side, for example, via Glu-309 by an exchange reaction for H+ on Ca2+ binding (model 2), the protonation state of Glu-58 negatively affects the number of protons countertransported, which will be 2.6 at pH 6.0 and 2.2 at pH 8.0 (Table 2).

As mentioned earlier, we also carried out all of the calculations for ε = 20. In this case, the situation is more complex because the protonation probability of Glu-908 is decreased and pH dependent (Table 3). The expected number of protons countertransported is ≈2.5 for model 1 and 1.7 for model 2. We further examined the case in which the Glu-309 side chain orients to the outside as in the published model of E2(TG) (20). Its protonation probability remains high because many acidic residues surround this residue on the cytoplasmic side (Fig. 1).

Are Water Molecules Countertransported? Because the number of water molecules in the Ca2+-binding sites is two in E1·2Ca2+ and five in E2(TG+BHQ) (Figs. 6, 7, 8), these atomic models will mean that three water molecules are countertransported with protons, if they come from the luminal side and are released into the cytoplasm. However, it is also conceivable that they are introduced from cavities within the protein on Ca2+ release and returned to the same places in Ca2+ binding. In this case, no net flow of water across the membrane results. For the candidates, we can propose two crystallographic water molecules (d and e in Fig. 7) located below the Arg-762 side chain and those just beyond Glu-309 on the opposite side of the Ca2+-binding cavity. Water d and e may be introduced by rearrangements of the long side chains of Glu-759, Arg-762, and Glu-918 (Fig. 7). Those on the Glu-309 side may enter the binding cavity possibly past Gly-310 or, for molecule c (Figs. 6 and 7), by the rotation of Leu-797 in M6. In any event, three water molecules must be excluded from the Ca2+-binding sites when two Ca2+ bind to the ATPase. Whether this exclusion results in the transport of water across the membrane remains to be seen.

Discussion

As described, inclusion of BHQ, in addition to TG, stabilized the transmembrane region of Ca2+-ATPase in the E2 state to a level similar to that in E1·2Ca2+ and resolved several phospholipid and water molecules. This result has allowed us to propose atomic models of the Ca2+-binding sites with explicit hydrogens, and to show how empty spaces and charge imbalance created by Ca2+-release are compensated for by events that could result in countertransport, as summarized in Fig. 8. A phospholipid moves to fill a large lipid-facing space, and water molecules do the same for the protein interior. Charge imbalance is solved predominantly by protonation, which is certainly the most direct means. However, protonation alone is not enough, particularly when both oxygen atoms of a carboxyl group are used for coordination. Conformational changes and incorporation of water molecules are needed (Table 4). Conversely, water alone cannot substitute for metal ions either, because a water molecule is larger (atomic radius: 1.4 Å) than a Ca2+ (ionic radius: 0.99 Å) and can accommodate less oxygen atoms (four vs. six to eight). Ionization of a cluster of carboxyls within the hydrophobic core of the membrane would incur a huge energetic cost (>100 kcal/mol in this case; Table 2). These considerations make the countertransport of either metal ions or H+, and possibly water, mandatory for all P-type ATPases, although for many of them the ions countertransported are unknown as yet. It could be difficult to identify them, because ion gradients generated by countertransport might be dissipated by other means.

In the Ca2+-ATPase, all of the residues protonated are involved in Ca2+-coordination, indicating that Ca2+-binding is, in fact, an exchange reaction with H+. This finding provides at least a partial explanation for the well-known pH dependence of Ca2+-binding affinity (10 times weaker at pH 6.0 than at pH 7.0) (15). The presence of one titratable residue per each Ca2+-binding site (15, 16) agrees with the electrostatic calculation described here, but strong pH dependence of those residues in the neutral range (5, 15, 16) does not. This inconsistency is understandable because substantial conformation changes take place during Ca2+-binding, whereas the electrostatic calculations assume rigid structures.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank M. Kawamoto, H. Sakai, N. Shimizu, and T. Tsuda for data collection at BL41XU of SPring-8 and Y. Ohuchi for computer programs. We thank D. Bashford (St. Jude Children's Research Hospital, Memphis, TN) for providing us with his MEAD program; M. Ikeguchi (Yokohama City University, Yokohama, Japan) for the MARBLE program; and D. B. McIntosh and D. H. MacLennan for their help in improving the manuscript. This work was supported in part by a Creative Science Project Grant from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology; the Japan New Energy and Industry Technology Development Organization; and the Human Frontier Science Program.

This contribution is part of the special series of Inaugural Articles by members of the National Academy of Sciences elected on May 3, 2005.

Abbreviations: SERCA, sarco(endo)plasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase; TG, thapsigargin; BHQ, 2,5-di-tert-butyl-1,4-dihydroxybenzene; PDB, Protein Data Bank.

Data deposition: The atomic coordinates for the E2(TG+BHQ) form of Ca2+-ATPase have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, www.pdb.org (PDB ID code 2AGV).

References

- 1.MacLennan, D. H., Brandl, C. J., Korczak, B. & Green, N. M. (1985) Nature 316, 696-700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Møller, J. V., Juul, B. & le Maire, M. (1996) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1286, 1-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levy, D., Seigneuret, M., Bluzat, A. & Rigaud, J. L. (1990) J. Biol. Chem. 265, 19524-19534. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yu, X., Carroll, S., Rigaud, J. L. & Inesi, G. (1993) Biophys. J. 64, 1232-1242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Forge, V., Mintz, E. & Guillain, F. (1993) J. Biol. Chem. 268, 10953-10960. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buoninsegni, F. T., Bartolommei, G., Moncelli, M. R., Inesi, G. & Guidelli, R. (2004) Biophys. J. 86, 3671-3686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Albers, R. W. (1967) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 36, 727-756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Post, R. L., Hegyvary, C. & Kume, S. (1972) J. Biol. Chem. 247, 6530-6540. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Meis, L. & Vianna, A. L. (1979) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 48, 275-292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kühlbrandt, W. (2004) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 5, 282-295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.MacLennan, D. H., Rice, W. J. & Green, N. M. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272, 28815-28818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Toyoshima, C. & Inesi, G. (2004) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 73, 269-292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meissner, G. & Young, R. C. (1980) J. Biol. Chem. 255, 6814-6819. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Peinelt, C. & Apell, H. J. (2002) Biophys. J. 82, 170-181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Watanabe, T., Lewis, D., Nakamoto, R., Kurzmack, M., Fronticelli, C. & Inesi, G. (1981) Biochemistry 20, 6617-6625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Meis, L. & Inesi, G. (1982) J. Biol. Chem. 257, 1289-1294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Andersen, J. P. (1994) FEBS Lett. 354, 93-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vilsen, B. & Andersen, J. P. (1998) Biochemistry 37, 10961-10971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Toyoshima, C., Nakasako, M., Nomura, H. & Ogawa, H. (2000) Nature 405, 647-655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Toyoshima, C. & Nomura, H. (2002) Nature 418, 605-611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Toyoshima, C. & Mizutani, T. (2004) Nature 430, 529-535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Toyoshima, C., Nomura, H. & Tsuda, T. (2004) Nature 432, 361-368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Olesen, C., Sørensen, T. L., Nielsen, R. C., Møller, J. V. & Nissen, P. (2004) Science 306, 2251-2255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sørensen, T. L., Møller, J. V. & Nissen, P. (2004) Science 304, 1672-1675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bashford, D. & Karplus, M. (1990) Biochemistry 29, 10219-10225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang, A. S., Gunner, M. R., Sampogna, R., Sharp, K. & Honig, B. (1993) Proteins 15, 252-265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Berneche, S. & Roux, B. (2002) Biophys. J. 82, 772-780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sugita, Y., Miyashita, N., Ikeguchi, M., Kidera, A. & Toyoshima, C. (2005) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127, 6150-6151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sagara, Y. & Inesi, G. (1991) J. Biol. Chem. 266, 13503-13506. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Khan, Y. M., Wictome, M., East, J. M. & Lee, A. G. (1995) Biochemistry 34, 14385-14393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Inesi, G., Ma, H., Lewis, D. & Xu, C. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 31629-31637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Coll, R. J. & Murphy, A. J. (1984) J. Biol. Chem. 259, 14249-14254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stokes, D. L. & Green, N. M. (1990) Biophys. J. 57, 1-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Otwinowski, Z. & Minor, W. (1997) Methods Enzymol. 276, 307-325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brünger, A. T., Adams, P. D., Clore, G. M., DeLano, W. L., Gros, P., Grosse-Kunstleve, R. W., Jiang, J. S., Kuszewski, J., Nilges, M., Pannu, N. S., et al. (1998) Acta Crystallogr. D. 54, 905-921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Karin, N. J., Kaprielian, Z. & Fambrough, D. M. (1989) Mol. Cell. Biol. 9, 1978-1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sumbilla, C., Lu, L., Lewis, D. E., Inesi, G., Ishii, T., Takeyasu, K., Feng, Y. & Fambrough, D. M. (1993) J. Biol. Chem. 268, 21185-21192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ho, S. N., Hunt, H. D., Horton, R. M., Pullen, J. K. & Pease, L. R. (1989) Gene 77, 51-59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lanzetta, P. A., Alvarez, L. J., Reinach, P. S. & Candia, O. A. (1979) Anal. Biochem. 100, 95-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bashford, D. & Gerwert, K. (1992) J. Mol. Biol. 224, 473-486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ikeguchi, M. (2004) J. Comp. Chem. 25, 529-541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Georgescu, R. E., Alexov, E. G. & Gunner, M. R. (2002) Biophys. J. 83, 1731-1748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bick, R. J., Youker, K. A., Pownall, H. J., Van Winkle, W. B. & Entman, M. L. (1991) Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 286, 346-352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lange, C., Nett, J. H., Trumpower, B. L. & Hunte, C. (2001) EMBO J. 20, 6591-6600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yu, M., Lin, J., Khadeer, M., Yeh, Y., Inesi, G. & Hussain, A. (1999) Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 362, 225-232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Xu, C., Ma, H., Inesi, G., Al Shawi, M. K. & Toyoshima, C. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 17973-17979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wictome, M., Michelangeli, F., Lee, A. G. & East, J. M. (1992) FEBS Lett. 304, 109-113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hayward, S. (2001) Protein Sci. 10, 2219-2227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Berneche, S. & Roux, B. (2000) Biophys. J. 78, 2900-2917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kraulis, P. J. (1991) J. Appl. Crystallogr. 24, 946-950. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.