Abstract

Mesoporous silica nanoparticles (MSNs) have emerged as cornerstone biomaterials for nanomedicine due to their highly tunable physicochemical properties. This review highlights recent breakthroughs in MSN-based platforms for disease theranostics. We systematically outline fundamental synthesis strategies and detail how surface functionalization-imparting properties such as targeting, stimuli-responsiveness, and biomimicry-transforms MSNs from passive carriers into intelligent theranostic agents. The review then summarizes the major contributions of these engineered platforms across key diagnostic (e.g., advanced imaging) and therapeutic (e.g., targeted drug delivery, dynamic therapies) applications, underscoring their potential in tackling complex diseases. Finally, we address the critical challenges hindering clinical translation, including manufacturing scalability and long-term biocompatibility. We conclude by outlining future directions, such as integration with emerging modalities like immunotherapy, aimed at accelerating the bench-to-bedside transition of MSN-based nanomedicines.

Keywords: Mesoporous silica nanoparticles, Synthesis strategies, Surface-functionalized modifications, Theranostic applications, Antibacterial applications, Vaccine applications

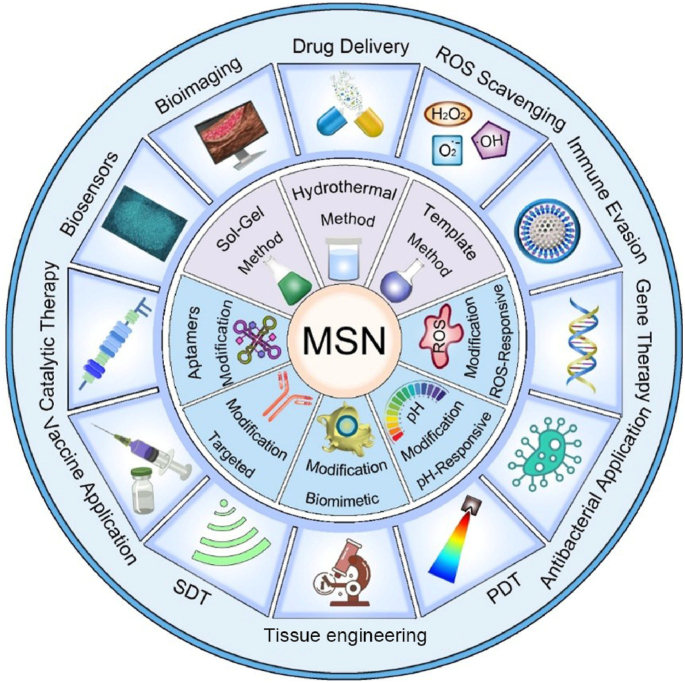

Graphical abstract

Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticle-Based Nanomedicine: Preparation, Functional Modification, and Theranostic Applications comprehensively summarizes the most recent advancements in mesoporous silica nanoparticles (MSNs) for disease theranostics, systematically discussing innovative synthesis approaches, advanced surface functionalization strategies, and their extensive biomedical applications. Furthermore, it critically examines current challenges and provides insightful perspectives on future directions to facilitate clinical translation.

Highlights

-

•

A comprehensive overview of MSN synthesis and surface engineering.

-

•

The Broad-spectrum biomedical applications of MSNs-based nanoplatforms.

-

•

Translational insight and future prospects of MSNs for clinical application.

1. Introduction

With the rapid progress of nanotechnology, nanomaterials featuring excellent physicochemical properties find extensive applications in biomedicine. Considerable efforts have been dedicated to the design of multifunctional nanoformulations with customized capabilities for precise cargo delivery, advanced diagnostics, and targeted therapeutics [[1], [2], [3], [4], [5], [6], [7], [8], [9], [10], [11], [12]]. Nanoformulations present superior pharmaceutical advantages when compared to conventional macroformulations. These benefits include enhanced bioavailability, reduced systemic toxicity - a critical advantage considering the significant hematological and histopathological side effects associated with many conventional drugs like diclofenac sodium [13] - and improved in vivo target selectivity [14]. Nanotherapeutics are typically classified into two main types: organic and inorganic nanoformulations [15]. The clinical translation of organic nanocarriers has been convincingly evidenced by two significant achievements: i) The landmark approval of Doxil® in 1995, which confirmed liposomes as viable clinical delivery systems [16]. ii) The emergency authorization of lipid nanoparticles-based COVID-19 mRNA vaccines (BNT162b2 and mRNA-1273), marking a paradigm shift in vaccinology [17]. Beyond these synthetic organic systems, researchers are also exploring novel biological carriers, such as drug-loaded living organisms, for the targeted treatment of challenging diseases like gastrointestinal cancer [18]. Although the inherent biocompatibility of some inorganic nanoparticles (NPs) can pose greater challenges compared to their organic counterparts, it is crucial to discuss this with nuance. The toxicity concerns associated with MSNs are complex and can be significantly mitigated through strategic functionalization, a point corroborated by recent research. For instance, studies have shown that appropriately modified MSN-based nanoplatforms can serve as highly effective and biocompatible theranostic agents for treating complex inflammatory diseases [19]. The ease and versatility of functionalization have thus become a cornerstone of MSN-based nanomedicine, enabling precise control over their biological interactions and therapeutic outcomes [20]. Consequently, these engineered inorganic platforms often demonstrate greater superiority in stability and drug delivery efficiency. Inorganic NPs have effectively facilitated the development and application of various innovative nanotherapeutic methods owing to their unique optical, ultrasonic, magnetic, and catalytic properties. These methods include photothermal therapy (PTT), photodynamic therapy (PDT), sonodynamic therapy (SDT), chemodynamic therapy (CDT), and nanozyme-based catalytic therapy, which are crucial therapeutic strategies [[21], [22], [23], [24], [25], [26], [27], [28], [29], [30]]. Encouragingly, inorganic NPs have gradually entered the field of clinical medicine, with approximately 25 inorganic nanomedicines currently approved for clinical use [31]. A prominent example is the development of Cornell dots (C′ dots), ultrasmall silica-based fluorescent nanoparticles, which became the first of their kind to be approved by the FDA for clinical trials in cancer imaging [32]. The successful clinical translation of such silica-based platforms provides a strong precedent and valuable insights for the development of more complex mesoporous silica-based systems, which are the focus of this review. This progress is built upon extensive research into a wide array of inorganic nanomaterials. For example, significant efforts are dedicated to the green synthesis of silver nanoparticles for their antibacterial and cytotoxic potential [33], and the development of sophisticated magnetic nanocomposites supported on materials like activated carbon for applications in antimicrobial therapy and environmental remediation [34,35].

Among a variety of inorganic nanocarriers, mesoporous silica nanoparticles (MSNs) have attracted extensive global research interest owing to a unique combination of structural and morphological characteristics that enable them exceptionally suitable as nanomedicine platforms [[36], [37], [38]]. The widespread application of MSNs in the biomedical field is rooted in the following key attributes: 1) High Specific Surface Area and Large Pore Volume: The intrinsic mesoporous network provides MSNs with an exceptionally large surface area (often >700 m2/g) and pore volume [39]. This structural feature is paramount for achieving high loading capacity for a wide range of therapeutic agents, including small-molecule drugs, peptides, and genes, thereby enhancing therapeutic efficacy. 2) Tunable Pore Size: The diameter of the mesopores (typically 2–50 nm) can be precisely engineered by selecting different templates during synthesis [40]. This tunability allows for the tailored encapsulation of guest molecules based on their size and prevents premature leakage, enabling sophisticated control over drug release kinetics. 3) Controllable Particle Size and Morphology: The overall particle size of MSNs (typically 50–200 nm) can be meticulously controlled, which is crucial for modulating their in vivo behavior, such as blood circulation time, biodistribution, and cellular uptake [41]. This control is vital for leveraging passive targeting mechanisms like the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect in tumors. Furthermore, their morphology (e.g., spherical, rod-like) can also be adjusted to influence cellular interactions and therapeutic outcomes [42]. 4) Versatile Surface Chemistry: The surface of MSNs is rich in silanol groups (-Si-OH), which serve as readily available anchor points for functional modification [43]. This chemical versatility facilitates the covalent grafting of targeting ligands (e.g., antibodies, peptides), stimuli-responsive “gatekeepers," and stealth polymers (e.g., PEG), transforming MSNs into intelligent, targeted theranostic agents [44]. Collectively, these distinct structural and physicochemical properties endow MSNs with unparalleled design flexibility, enabling them a cornerstone material in the development of next-generation nanomedicine.

The evolution from simple nanoparticle synthesis to sophisticated in vivo applications represents a valuable paradigm shift in the field. Within the realm of inorganic nanoparticles, a key contemporary focus is on microstructured nanoparticles. Recent advances, for example, have highlighted the power of integrating these inorganic cores with smart polymers to create hybrid systems for stimuli-responsive drug delivery, which have shown significant promise in overcoming formidable biological barriers like the blood-brain barrier [45]. Beyond functional sophistication, the field is also moving towards greater sustainability and translatability. This includes developing protocols for the renewable synthesis of MSNs, standardizing their characterization, and optimizing loading protocols for a diverse range of therapeutics, from small molecules to proteins and nucleic acids like siRNA and mRNA [46]. These trends underscore a maturation of the field, moving towards more robust, reproducible, and clinically viable nanomedicines. It is in this advanced context that MSNs, as a prototypical microstructured nanoparticle, truly shine.

The precisely controllable fabrication and straightforward functionalization of MSNs endow these intricate nanosystems with unique physicochemical characteristics. This confers upon them a high degree of adaptability to specific circumstances. For instance, owing to their multifunctional nature and outstanding biocompatibility, MSNs can serve as robust nanoplatforms for biomedical applications within complex biological milieus [[47], [48], [49]]. Consequently, the current research trajectory in the realm of mesoporous materials is gradually transitioning from a primary emphasis on microstructure-controlled synthesis methodologies to a more in-depth exploration of their practical in vivo applications in the medical domain [[50], [51], [52], [53], [54]]. The large specific surface area and pore diameter of MSNs facilitate the efficient delivery of drugs or other therapeutic molecules to the surrounding biological environments, thereby substantially enhancing the treatment efficacy. At present, MSNs have been extensively employed across a wide range of therapeutic areas, encompassing controlled drug release, gene delivery, diagnostic imaging, and tissue engineering applications [[55], [56], [57]]. These versatile nanoplatforms display an extraordinary diversity in terms of size, morphology, architecture, composition, and functionality, enabling a customized design that can be tailored to meet specific biomedical requirements. Such structural flexibility significantly broadens the scope of therapeutic and diagnostic applications in the field of nanomedicine.

A number of review articles have recently reported on the advances of mesoporous silica-based nanoplatforms in nanodynamic therapy and photo-activated tumor treatment [58,59]. Additionally, some publications have explored their applications in tumor theranostics, particularly from the perspective of biodegradability [60]. However, to date, there remains a lack of a comprehensive review that systematically summarizes the preparation strategies, surface functionalization methods, and biomedical theranostic applications of mesoporous silica-based nanoplatforms. Therefore, this review offers a more comprehensive integration of recent breakthroughs from preparation strategies, functionalized modification and theranostic applications. In this review, we systematically summarize the fundamental synthesis methods of MSNs, encompassing the sol-gel method, hydrothermal method, and template method. Subsequently, we elaborate on several functionalized modification strategies for MSNs, such as targeted modification, biomimetic modification, stimulus-responsive modification, and aptamer-based surface modification. Additionally, we present a concentrated overview of the latest advancements in MSN-guided biomedical applications, placing particular emphasis on their diagnostic and therapeutic applications across a diverse range of diseases. Finally, we rigorously assess the current clinical translation status of MSNs and tackle the primary obstacles impeding their full-fledged biomedical implementation. This review provides a systematic overview of strategies to optimize MSN-based nanoplatforms, with the goal of enhancing their clinical utility and translational potential. While we adopt a foundational framework that logically progresses from preparation to application, our primary aim is to provide a distinctive, theranostic-centric perspective. To demonstrate these theranostic applications aesthetically, Fig. 1A depicts the functionalized mechanisms of the MSN platform schematically. The functionalization predominantly comprises: therapeutic cargoes, responsive gates, targeting ligands, tracking markers, and endosomal escape triggers [61]. Although the biomedical applications of silicon dioxides are vast in the recent two decades (Fig. 1B), this review will place particular emphasis on MSNs roles in the theranostics of cancer and inflammatory diseases. This focus is deliberate, as recent scholarship highlights the value of contextualizing nanotechnologies within specific disease landscapes, where MSNs have demonstrated remarkable progress as versatile platforms for both enhancing cancer theranostics [62] and for treating inflammatory disorders [19]. By narrowing our scope to these highly active research fronts, we seek to systematically elucidate the connections between fundamental synthesis methods and their influence on surface modification potential, and further, how these refined modifications empower the advanced theranostic applications at the forefront of modern nanomedicine. This purpose-driven narrative, visually summarized in Scheme 1, is designed to serve as an insightful roadmap for the rational design of next-generation MSN-based theranostics.

Fig. 1.

(A) Schematic mechanism diagram of functional modification of MSN. (B) Schematic illustration showing the published literature on the application of silicon dioxide in biomedical fields, derived from the analysis by Web of Science. (A) Reproduced with permission [61]. Copyright 2025, Whily. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

Scheme 1.

Schematic illustration of the synthesis, functional modification, and theranostic applications of nano-enabled mesoporous silica materials.

2. Preparation strategies

MSNs are regarded as a subset of inorganic nanoparticles. They are characterized by their ordered mesoporous structure, which mainly consists of a silicon dioxide (SiO2) framework. MSNs have attracted significant attention in the domains of drug delivery, biosensing, and disease theranostics [[63], [64], [65]]. Leveraging these properties, MSNs can encapsulate and deliver a wide variety of therapeutic agents, including nucleic acids, drugs, and CRISPR-based gene-editing tools [66]. To enhance drug delivery and theranostic applications, MSNs are expected to possess adjustable shape, particle size, surface charge, and pore structure through various preparation methods [[67], [68], [69], [70], [71]]. This section presents a comprehensive overview of diverse synthesis strategies for mesoporous silica nanoparticles (MSNs), encompassing the sol-gel method, hydrothermal method, and template method. A visual summary of these strategies, highlighting their core mechanisms and respective pros and cons, is provided in Fig. 2. The advantages and disadvantages of these three methods have been systematically summarized in Table 1.

Fig. 2.

Comparative schematic of the primary strategies for the fabrication of Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles (MSNs). The figure illustrates three representative fabrication methods-Sol-Gel, Hydrothermal, and Template-each with its characteristic workflow, advantages, and limitations. The Sol-Gel method features mild reaction conditions and high tunability but suffers from long reaction times and lower structural order. The Hydrothermal method enables high crystallinity and scalability under harsh conditions requiring specialized equipment. The Template method offers precise structural control and versatility but involves intricate procedures and limited scalability. This comparative schematic provides a concise visual summary to guide the selection of appropriate synthesis strategies for specific biomedical applications.

Table 1.

Comparative analysis of primary strategies for the fabrication of mesoporous silica nanoparticles (MSNs).

| Strategy | Sol-Gel Method | Hydrothermal Method | Template Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Key Advantages | The operation is simple, the conditions are mild, and the tunability is high. | Exhibiting high crystallinity, remarkable stability, and a high yield. | Highly ordered mesoporous structure, along with tunable pore size and morphology. |

| Key Disadvantages | A relatively long reaction time, along with the removal of the template agent. | Equipment operating under high temperature and high pressure is subject to relatively stringent reaction conditions. | The removal of the template agent entails intricate procedures. |

| Typical Particle Size (nm) | 50–300 | 100–500 | 50–1000 |

| Typical Pore Size (nm) | 2–15 | 2–10 | 2-50∼ |

| Yield/Scalability | Moderate yield; Good lab-scale scalability | High yield (>90 %); Good potential for industrial scale-up | Variable yield; Generally lower scalability, especially for hard templates |

| Refs. | [[72], [73], [74]] | [[75], [76], [77], [78]] | [[79], [80], [81]] |

2.1. Sol-gel method

The sol-gel technique, a quintessential example of soft-templating in soft chemistry, is widely recognized for the synthesis of MSNs. In this inorganic polymerization process, soluble metal alkoxide precursors-most commonly tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS)-are converted into solid metal oxides with three-dimensional networks through a series of hydrolysis and condensation reactions, typically conducted under mild conditions (room temperature or slightly elevated) [[82], [83], [84], [85], [86], [87]]. The process initiates with the self-assembly of surfactant molecules, such as the cationic surfactant cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB), forming ordered micellar structures (e.g., cylindrical rods) in aqueous solution. Upon introduction of the silica precursor (TEOS), hydrolysis and condensation yield silica species that co-assemble around the surfactant micelles via electrostatic interactions, resulting in a rigid inorganic silica framework that mimics the ordered structure of the template. Additional reagents, such as 3-aminopropyltriethoxysilane (APTES), can be employed to introduce functional groups [[88], [89], [90]]. The final step involves removal of the surfactant template-typically through high-temperature calcination or solvent extraction-producing highly ordered mesoporous silica networks with particle sizes generally ranging from 60 to 100 nm. The aerosol-assisted sol-gel method is an advanced technique in which the precursor solution is atomized into fine droplets and passed through a heated furnace. Each droplet serves as a microreactor, enabling rapid hydrolysis, condensation, and self-assembly. This approach streamlines the synthesis process, allowing for continuous and efficient production of highly spherical and uniform MSNs, often integrating synthesis and template removal into a single step. Whether through the conventional batch process or the continuous aerosol-assisted route, this versatile approach enables precise control over pore size, morphology, and surface properties, establishing it as a foundational and widely adopted strategy for the preparation of MSNs.

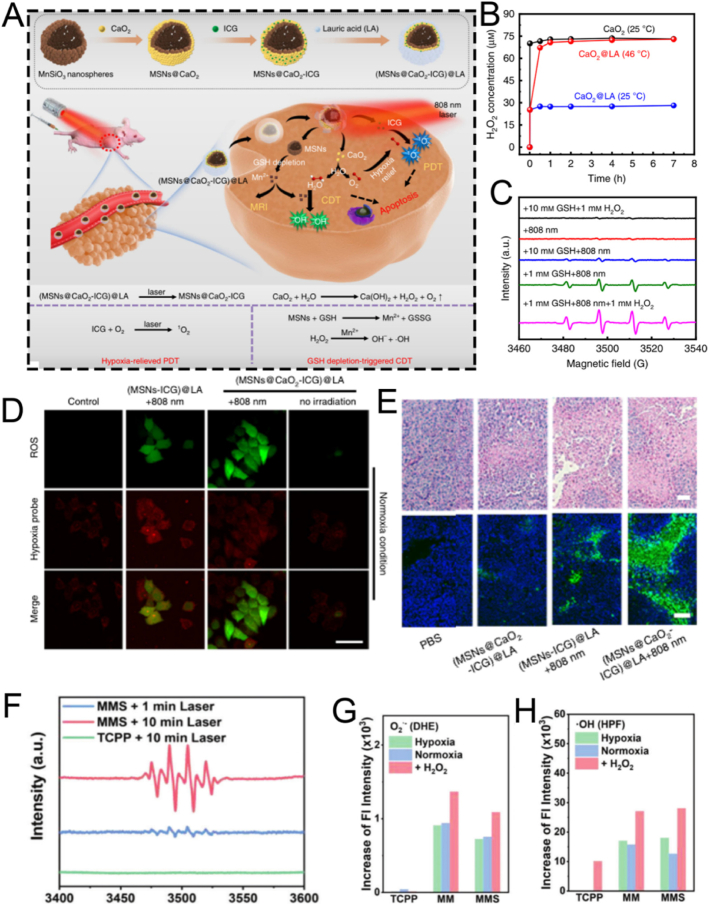

For instance, Xiao et al. employed CTAB as the mesoporous structure-directing agent, TEOS as the silica precursor, and mitochondrial N770 to fabricate calcium peroxide (CaO2)-conjugated mesoporous silica nanoparticles (CaO2-N770@MSNs) via the sol-gel method for photo-immunotherapy against colorectal cancer (Fig. 3A) [72]. Briefly, CTAB, NH3·H2O, ethyl ether, and ethanol were mixed and reacted thoroughly for 0.5 h. Subsequently, TEOS was added and stirred vigorously for an additional 4 h to obtain MSNs. Then, N770 was added to amino group-functionalized MSNs based on electrostatic adsorption to fabricate the final N770@MSNs material. The synthesized N770@MSNs exhibited a branched mesoporous structure with a diameter of 400 nm and a pore size of 4.58 nm, enabling efficient loading of CaO2 (Fig. 3B). The incorporation of CaO2 endowed N770@MSNs with calcium overload characteristics, which could be further enhanced by phototherapy performance, thus facilitating synergistic calcium overload and phototherapy. Although this therapeutic platform (CaO2-N770@MSNs combined with NIR irradiation and αPD-L1) has demonstrated both biosafety and efficacy, its preparation involves multiple steps, which may pose challenges for clinical translation. Therefore, further optimization and simplification of the preparation process are necessary to better meet the requirements of practical clinical applications.

Fig. 3.

(A) Schematic illustration of the fabrication procedure of CaO2-N770@MSNs. (B) Transmission electron microscope (TEM) and Energy dispersive spectrometer (EDS) characterization of CaO2-N770@MSNs. Scale bar: 200 μm. (C) Schematic diagram of ZnPP@MSN-RGDyK(Z@M-R) fabrication. (D) Representative TEM image of Z@M-R. (E) Schematic illustration of the FeMSN@DOX preparation. (F) Representative TEM image of FeMSN@DOX. (G) N2 adsorption-desorption isotherm of FeMSN@DOX. (H) Appropriate pore size distribution of FeMSN@DOX. (A, B) Reproduced with permission [72]. Copyright 2023, Elsevier. (C, D) Reproduced with permission [73]. Copyright 2022, Wiley Online Library. (E–H) Reproduced with permission [74]. Copyright 2022, Elsevier.

Some patients with non-small cell lung cancer spinal metastasis are unresponsive to immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) targeting programmed death 1 (PD 1)/programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1). To tackle this problem, Jiang and colleagues designed a drug delivery nanocarrier, ZnPP@MSN-RGDyK, targeting NSCLC-SM with PD-L1. This nanocarrier consists of zinc protoporphyrin (ZnPP), MSN, and RGDyK and is used for non-small cell lung cancer spinal metastasis PDT and immunotherapy (Fig. 3C) [73]. Among these components, the MSN nanoparticles were prepared via the sol−gel method. Briefly, cetyltrimethylammonium chloride (CTAC), CH3COONa, and double-distilled water were vigorously stirred at 60 °C for 1 h. Then, TEOS was added to the above solution and continuously stirred for 16 h. Subsequently, APTES was added and stirred for an additional 4 h to synthesize MSN. These synthesized MSN nanoparticles exhibited a characteristic spherical mesoporous structure with a diameter of 50 nm and excellent monodispersity of mesoporous nanospheres (Fig. 3D). To boost the synergistic effect of PDT and ICIs by releasing tumor antigens to activate T cells, the integrin β3 inhibitor RGDyK (which promotes PD-L1 ubiquitination) and ZnPP were encapsulated in MSNs. Overall, the ZnPP@MSN-RGDyK ultimately synthesized via the sol-gel method demonstrated excellent PDT efficiency and remarkable immunosuppressive effects.

As well as conventional MSN, mesoporous nanozymes have attracted significant attention for their applications in drug delivery and disease theranostics. These nanozymes not only exhibit enzyme-mimicking catalytic functions but also integrate with other therapeutic modalities to enable efficient disease theranostics. For example, He et al. utilized TEOS as a silica precursor and octadecyl trimethoxysilane (C18TMS) as a mesoporous structure aligner to fabricate iron-doped mesoporous silica nanoparticles (FeMSNs) via a sol-gel method for synergistic CDT and chemotherapy (Fig. 3E) [74]. Briefly, iron ethoxide, C18TMS, and TEOS were homogeneously mixed and allowed to react at 30 °C for 6 h. Subsequently, the resultant product was calcined at 550 °C for 6 h to obtain the final FeMSNs material. The fabricated FeMSNs exhibited a spherical mesoporous morphology with a diameter of 80 nm and a pore size of 3.08 nm, which facilitated the efficient incorporation of the chemotherapeutic drug doxorubicin (Dox) (Fig. 3F–H). The electrostatic interaction between FeMSNs and Dox enabled the assembly of Dox-loaded FeMSNs (FeMSN@Dox). The incorporation of iron endowed FeMSNs with peroxidase-like properties, which could synergize with Dox chemotherapy.

2.2. Hydrothermal method

The hydrothermal technique is an advanced synthetic method for producing MSNs, in which raw materials are dissolved in an aqueous solution and subjected to high-temperature, high-pressure conditions within a Teflon-lined stainless-steel autoclave [[91], [92], [93]]. Typically, the reaction mixture-comprising a silicon precursor and a surfactant template-is heated to 100–180 °C for an extended period. A significant enhancement to this process is the microwave-assisted hydrothermal method, which utilizes microwave irradiation instead of conventional oven heating. This approach dramatically reduces reaction times, often from hours to mere minutes, by providing rapid, uniform, and direct energy to the reaction mixture, thereby improving energy efficiency and synthesis speed. Compared to the conventional sol-gel method, the hydrothermal process accelerates the hydrolysis and condensation of the silica framework, resulting in a higher degree of cross-linking and the formation of thicker, more robust pore walls [[94], [95], [96], [97], [98]]. The elevated temperature and autogenous pressure also facilitate the dissolution and re-deposition of silica species (akin to Ostwald ripening), effectively healing structural defects and yielding MSNs with exceptional crystallinity, improved long-range porous order, and well-defined morphologies. The hydrothermal method is highly versatile, enabling precise control over MSN morphology and porosity by adjusting parameters such as pH, temperature, reaction time, and surfactant type. 1) pH: High pH speeds up silica formation and produces uniform, spherical particles; lower pH creates more complex shapes like rods or sheets. 2) Temperature: Higher temperatures and longer durations yield larger, more stable particles, but excessive heating can cause aggregation. 3) Surfactant: The type and amount of surfactant determine pore size-ationic surfactants produce smaller pores, while non-ionic ones create larger pores suitable for loading bigger molecules. By tuning these factors, researchers are available to customize MSN structures for specific drug delivery and theranostic uses. For instance, larger pore sizes (>10 nm) achieved through specific surfactants are crucial for accommodating bulky therapeutic cargo like proteins and nucleic acids, while precise control over morphology to create hollow structures can dramatically increase the drug loading capacity. This enables hydrothermal synthesis a valuable tool in nanomedicine. Chen et al. synthesized the tumor-targeted and tumor-responsive MSNs-based nanocomposite, Fe3O4/CDs-MSNs-FA, via a straightforward hydrothermal approach for tumor-selective multimodal theranostics (Fig. 4A) [75]. The fabricated Fe3O4/CDs-MSNs-FA functioned as a tumor-targeting agent, facilitating imaging-mediated synergistic chemo-catalytic-photothermal therapy. Specifically, Fe3O4 and carbon dots were introduced in situ through a hydrothermal method by coordinating with Fe2+ and glutathione (GSH), thereby endowing MSNs with multimodal theranostic capabilities (Fig. 4B–D). Fe3O4 acted as both a photothermal agent and a catalyst, while carbon dots were instrumental in fluorescence imaging. After loading paclitaxel (PTX), polyester and folate-conjugated cyclodextrin were utilized as an esterase-sensitive gatekeeper to regulate the release of PTX from the pores of MSNs and as a tumor-specific agent for precise therapy, respectively. As expected, the nanoplatform effectively accumulated in tumor cells, followed by synergistic chemo-catalytic-photothermal therapy, leading to an apoptosis rate in tumor cells that was five times higher than that in healthy cells. In vivo experiments evidenced significant tumor suppression, and the survival rate of mice treated with the nanocomposite increased to over 80 % after five weeks of treatment. Preliminary biosafety of this nanoplatform was verified by monitoring the body weight, major organ weight, and histological staining of mice. However, systematic evaluations of its long-term metabolic behavior in vivo (beyond five weeks), the potential toxicity of degradation products, and immunogenicity remain to be conducted. In conclusion, this hydrothermally fabricated MSN-based nanocomposite presents a promising theranostic strategy for tumor therapy, though further studies are required to comprehensively assess its long-term biosafety and clinical translation potential.

Fig. 4.

(A) Schematic illustration of the PTX@Fe3O4/CDs-MSNs-FA synthesis. (B) EDS analysis and a TEM image of Fe3O4/CDs-MSNs. (C) A high-power TEM picture and X-ray diffraction image of a local area containing Fe3O4/CDs-MSNs, showing the presence of Fe3O4. (D) TEM images and fluorescence spectra of CDs derived from Fe3O4/CDs-MSNs after destroying the silica matrix and Fe3O4 with sodium hydroxide and hydrochloric acid. (E) Schematic illustration of the preparation and drug release control mechanism of a thermo/pH-responsive drug delivery platform comprising hollow hybrid mesoporous silica nanoparticles. (F) Statistical evaluation of bleeding time for rabbit live body rupture injuries in different groups. (G) Comparison of ammonia levels in plasma among all experimental groups. (A–D) Reproduced with permission [75]. Copyright 2021, The Royal Society of Chemistry. (E) Reproduced with permission [76]. Copyright 2020, Elsevier. (F) Reproduced with permission [77]. Copyright 2020, Elsevier. (G) Reproduced with permission [78]. Copyright 2020, Mashhad University of Medical Sciences.

Developing drug delivery nanoplatforms based on hollow mesoporous silica nanoparticles still poses considerable difficulties. To tackle this issue, He et al. successfully fabricated polyacrylic acid encapsulated hollow hybrid mesoporous silica to specifically deliver Dox for the anticancer therapy through a one-step hydrothermal method (Fig. 4E) [76]. Specifically, the pore-forming template CTAB was dissolved in a mixed solution of ammonia, ethanol, and water, and stirred at 35 °C for 60 min. Subsequently, two silica sources, TEOS and 1,2-Bis(triethoxysilyl)ethane (BTSE), were rapidly added, followed by continuous stirring at 1100 rpm at 35 °C for 24 h. The resulting product was collected by centrifugation and washed three times with ethanol. The obtained hybrid MSNs were then dispersed in water and transferred to a stainless-steel autoclave lined with polytetrafluoroethylene, where the hydrothermal reaction was carried out at 120 °C for 5 h. Owing to the hydrothermal treatment, the MSNs underwent a transformation from a solid to a hollow structure. The innovative hollow hybrid MSN prepared by hydrothermal method demonstrated exceptional biocompatibility and superior drug-loading capacity, highlighting its significant potential for application in cancer therapy. In addition to its exceptional performance in cancer therapy, the hydrothermally optimized MSN-based nanoplatform also demonstrated excellent efficacy in biomedical applications such as antibacterial hemostasis and the alleviation of hyperammonemia (Fig. 4F and G) [77,78]. These results conclusively emphasized its broad potential as a versatile nanotheranostic platform.

2.3. Template method

The template method for synthesizing MSNs commonly employs surfactants (such as CTAB, CTAC, and Pluronic F127) as structure-directing agents. These surfactants self-assemble to form mesoporous frameworks, into which a silicon source is introduced and guided to organize into ordered mesoporous structures [[99], [100], [101], [102]]. After synthesis, the template is removed to yield pure MSNs [103,104]. In recent years, growing attention has been given to novel template agents and green synthesis approaches, which aim to improve sustainability and reduce environmental impact. For example, natural resources such as diatom-derived silica have been explored as bio-templates, offering renewable and environmentally friendly alternatives to conventional surfactants [105,106]. These emerging strategies broaden the scope of MSN synthesis and highlight the potential of green chemistry in this field.

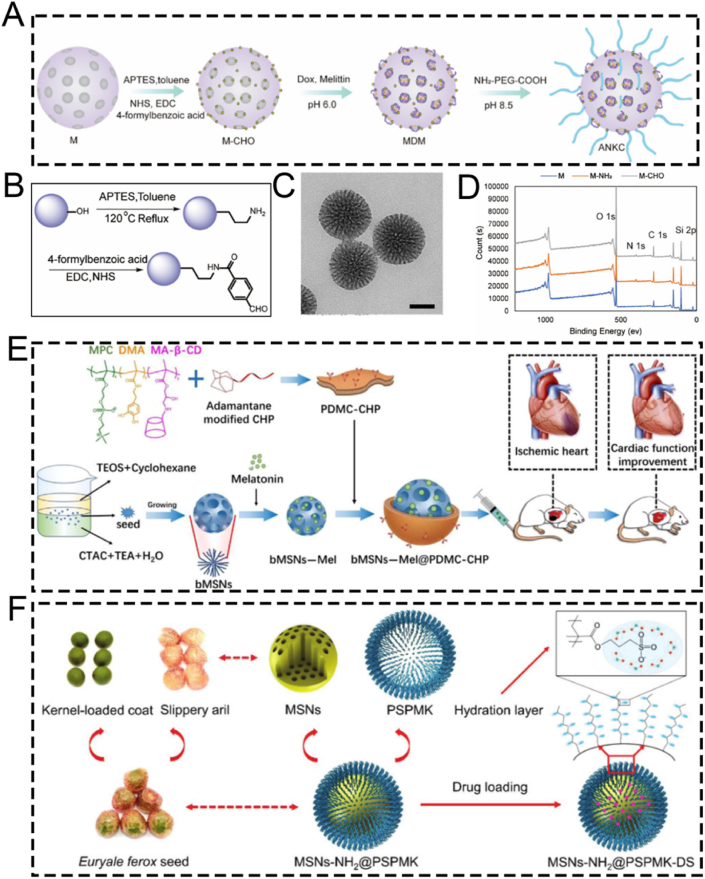

For instance, Mei et al. designed a pH-labile benzaldehyde-functionalized MSN as a scaffold material for artificial natural killer cells (ANKC). They employed CTAC and triethanolamine (TEA) as templates. The antitumor drugs Dox and melittin were loaded into the pores of the MSNs to overcome tumor drug resistance (Fig. 5A) [79]. Subsequently, the MSNs were successively functionalized with amino and aldehyde groups to facilitate drug loading (Fig. 5B). Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) characterization confirmed that the functionalized MSNs had a mesoporous structure (Fig. 5C). X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) elemental analysis verified the successful modification of MSNs with APTES, enabling the attachment of 4-carboxybenzaldehyde to the MSNs via amide bonds (Fig. 5D). Subsequently, Dox and melittin were loaded onto the 4-carboxybenzaldehyde-functionalized MSNs through Schiff base formation under weakly alkaline conditions. The pH-sensitive ANKC released Dox and melittin in the weakly acidic tumor microenvironment. Similar to perforin, melittin forms pores on the plasma membrane and endosomes, ensuring the intracellular transport of Dox. Meanwhile, Dox, similar to granzymes, initiates tumor cell apoptosis. In conclusion, MSNs fabricated using the template method and loaded with melittin and Dox present a promising strategy for treating drug-resistant tumors.

Fig. 5.

(A) Schematic diagram of ANKC construction. (B) Schematic representation of the M-CHO synthesis. (C) TEM image of M-CHO, scale bar: 50 nm. (D) X-ray photoelectron spectra (XPS) of M, M − NH2 and M-CHO. (E) Schematic diagram revealing the fabrication process of bMSNs-Mel@PDMC-CHP and the corresponding therapeutic effect of functionalized nanoparticles via intraventricular injection in mice with acute myocardial infarction. (F) Schematic diagram of the fabrication of ultra-lubricated drug-carrying nanoparticles MSNs-NH2@PSPMK-DS. (A–D) Reproduced with permission [79]. Copyright 2022, Elsevier. (E) Reproduced with permission [80]. Copyright 2024, Wiley. (F) Reproduced with permission [81]. Copyright 2018, Wiley.

Apart from their applications in certain tumor diseases, MSNs fabricated through the template method are also employed in cardiovascular diseases, such as myocardial infarction. For example, Fu et al. prepared a biodegradable MSNs-based nanoplatform, bMSNs-Mel@PDMC-CHP, with excellent macrophage escape, cardiac targeting, and drug release properties via a seed-mediated template method for the precise treatment of myocardial infarction (Fig. 5E) [80]. Briefly, they used CTAC as a mesoporous structure templating agent, TEOS as a silicon source, and TEA as a catalyst to synthesize MSNs. Hydrophobic organic solvents not only enabled the storage of the silicon source but also interacted with CTAC at the interface, assembling into oil/water emulsion micelles that served as mesoscopic templates for generating ordered mesoporous silica structures. Subsequently, a p(DMA-MPC-CD) copolymer with hydration lubrication, self-adhesive, and targeting peptide binding sites was successfully synthesized via free radical copolymerization. Using supramolecular host-guest interactions, adamantane-modified cardiac homing peptide (CHP) was self-assembled onto the surface of melatonin-loaded dendritic mesoporous silica nanoparticles (bMSNs). In vivo experiments demonstrated that bMSNs-Mel@PDMC-CHP, fabricated using CTAC via the template method, effectively alleviated cardiomyocyte apoptosis, improved myocardial interstitial fibrosis, and enhanced cardiac function.

Apart from CTAC, CTAB can also serve as a mesoporous structure-directing agent for MSNs. For example, the superlubricated Poly(potassium 3-sulfopropyl methacrylate)-grafted mesoporous silica nanoparticles (MSNs-NH2@PSPMK) were designed by Zhang et al. utilizing CTAB as a pore-forming template for the precise treatment of osteoarthritis (Fig. 5F) [81]. The grafted PSPMK polymers endowed the nanoparticles with enhanced lubricity due to the establishment of a robust hydration layer around the negative charges, while the ample mesoporous channels of MSNs enable efficient drug loading and release characteristics. When encapsulated with the anti-inflammatory agent diclofenac sodium (DS), the superlubricating nanoparticles exhibited improved lubricity while maintaining the drug release rate through enlarging the thickness of the PSPMK layer, which was briefly accomplished by arranging the precursor monomer concentration during photopolymerization. In vitro and in vivo experimental revealed that the fabricated MSNs-NH2@PSPMK nanoparticles via the template method effectively efficiently preserved the chondrocytes from degeneration, thereby suppressing the progression of osteoarthritis. Although this study proposed a synergistic effect of “hydration lubrication” and “anti-inflammatory drug release,” the underlying molecular mechanisms remain insufficiently explored. For instance, the interaction mechanism between the PSPMK polymer hydration layer and the glycosaminoglycans on the cartilage surface has not been clearly elucidated; the specific regulatory effects on chondrocyte metabolism after drug release have yet to be systematically described; and the potential impact on synovial inflammation in the joint has not been adequately evaluated. Overall, the mechanistic explanations provided are still relatively general and warrant further in-depth investigation.

In summary, the three conventional preparation methods-sol-gel, hydrothermal, and template-assisted-each offer distinct advantages and limitations for fabricating the basic MSN structure (Table 2). While these strategies provide the fundamental scaffolds, the resulting nanoparticles are merely passive carriers. To unlock their full theranostic potential by transforming them into intelligent agents that can navigate complex biological environments, precise surface engineering is paramount. Therefore, the following section will shift focus from the synthesis of the core to the functionalization of the surface, exploring the key modification strategies that serve as the fundamental 'building blocks' for advanced nanomedicine design. We will detail the underlying mechanisms for achieving the targeted, responsive, and biomimetic properties required for the advanced biomedical applications discussed later in this review.

Table 2.

Comparison of three preparation strategies for mesoporous silica materials.

| Strategies | Size Control | Morphology Control | Pore Structure Control | Large-scale Production |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sol-gel Method | Moderate | Diverse, relatively good | Generally less ordered | Simple operation, low cost |

| Hydrothermal Method | Precise, uniform | Easily tunable, diverse | Ordered, high crystallinity | Complex process, easy to scale up |

| Template Method | Precise, highly repeatable | Designable, diverse | Highly ordered, customizable | Complex process, high cost, hard to scale up |

3. Surface-functionalized modification of MSNs

The surface characteristics of ordered mesoporous silica can be modified by introducing inorganic species or grafting various organic functional groups. Surface functionalization methods generally involve surface grafting modification and co-condensation of functional silanes on the surface of MSNs [107,108]. Over the past 50 years, the field of silica surface modification has developed significantly. It not only enables the functional modification of ordered mesoporous silica but also allows for the customization of materials for chromatographic applications [[109], [110], [111]]. In this section, we introduce several key functionalization methods for MSNs, including targeted modification, biomimetic modification, stimuli-responsive modification, and aptamer-based surface engineering. It is crucial to recognize that these strategies are not merely a collection of techniques but represent distinct philosophies for interfacing nanoparticles with complex biological systems. To illustrate how these surface engineering strategies translate into practical biomedical applications, we have summarized representative MSN-based delivery systems in Table 3. This table compares their target indications, particle sizes, surface modifications, and observed in vivo outcomes, providing a functional overview of how surface design influences therapeutic performance. To provide a clear and critical comparison that will serve as a roadmap for this section, we have summarized the core attributes of each approach in Table 4. This table juxtaposes their underlying mechanisms, key advantages, inherent limitations, and ideal application scenarios, offering a comprehensive framework for selecting the most appropriate strategy for a given biomedical challenge. The following subsections will delve into the details of each strategy, substantiated with recent groundbreaking examples.

Table 3.

Summary of functional modifications of MSN-Based nanomaterials by Application, size, surface engineering, and in vivo outcome.

| Nanomaterials | Target Application | Size (nm) | Surface Modification | In Vivo Outcome | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SL@M@Arg-MSNs@BA | Acute Pancreatitis | ∼100–150 | DSPE-PEG-SLIGRL (PAC-targeting peptide) | Restored pancreatic function; Improved survival rate | [112] |

| MSN-PEG-Ab-TAT | Breast Cancer (NF-κB) | ∼100 | p65 antibody; TAT peptide | Tumor suppression in 4T1 mice | [113] |

| Mito(T)-pep-Nuc(T) | Liver Metastases | ∼120 | Triphenyl phosphonium; NLS peptide | Synergistic PDT/PTT tumor elimination | [114] |

| DMSN-Au-Fe3O4 | Tumor Catalytic Therapy | ∼80 | PEG; Au/Fe3O4 nanozymes | Tumor necrosis; high biocompatibility | [115] |

| ESC-HCM-B | Diabetic Nephropathy | ∼150–200 | Biomimetic composite membrane | Podocyte targeting; Decreased urinary protein; Improved kidney function | [116] |

| MSNs-NH2@PMPC | Osteoarthritis | ∼100–120 | PMPC polymer grafting | Cartilage protection; Decreased degeneration | [117] |

| DOX@MSN-WS2-HP | Tumor Chemotherapy/PTT | ∼100 | Benzoic-imine bond | Tumor suppression; selective cytotoxicity | [118] |

| MSN@DA | Anti-angiogenesis | ∼100 | Boronic ester bond | Tumor vessel normalization; Improved Dox efficacy | [119] |

| MSNConA | Osteosarcoma | ∼100 | Acetal linker | Enhanced cytotoxicity vs free drug; selective tumor targeting | [120] |

| PMS/PC | Diabetic Osteopathy | ∼120 | Phenyl sulfide group | Improved bone formation; Decreased vascular oxidative stress | [121] |

| MSN@TheraVac | Cancer Immunotherapy | ∼150 | Diselenide bond | Improved T-cell activation; Decreased immunosuppression | [122] |

| Ar-MSNs-TK-PEG | Retinal Diseases | ∼100 | Thioketal (TK); PEG | Retinal targeting; Decreased neovascularization | [123] |

| DNA-MSN (DNAM) | Osteoporosis | ∼100–120 | AptScl56 DNA aptamer | Restored bone mass; Improved mechanical strength | [124] |

| InCasApt | miRNA-responsive PDT | ∼150 | RNA aptamer precursor; CRISPR-Cas13a | Decreased tumor migration; Improved BRG1 expression | [125] |

| MSN-AP | Lung Cancer Exosome Removal | ∼100 | EGFR-targeting aptamer | Efficient exosome elimination via hepatobiliary pathway | [126] |

Table 4.

Comparative analysis of surface modification strategies for MSNs.

| Strategy | Underlying Mechanism | Key Advantages | Key Limitations | Ideal Application Scenarios |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Targeted | Specific ligand-receptor binding | High specificity; enhanced cellular uptake | High cost; potential immunogenicity; steric hindrance | Therapy for diseases with well-defined surface biomarkers (e.g., specific cancers) |

| Biomimetic | Camouflaging with natural cell membranes (e.g., RBC, platelet) | Excellent biocompatibility; prolonged circulation; immune evasion; inherent targeting | Complex fabrication; potential for batch-to-batch variability; reduced drug loading space | Systemic drug delivery requiring long circulation times and avoidance of the RES |

| Stimuli-Responsive | Cleavage of specific chemical bonds in response to microenvironmental cues (pH, ROS, etc.) | "On-demand" drug release; reduced premature leakage; improved therapeutic index | Potential for incomplete response; sensitivity may not perfectly match biological triggers | Tumor therapy (acidic & high-ROS TME); inflammation-targeted therapy |

| Aptamer-Based | 3D structural recognition of targets by nucleic acid aptamers | High specificity & affinity; low immunogenicity; easy synthesis; versatile targets | Susceptibility to nucleases in vivo; smaller size may lead to rapid renal clearance | Targeted drug delivery; biosensing; theranostics combining targeting and diagnostics |

3.1. Targeted modification

Nanoparticles are capable of enhancing bioavailability and decreasing the necessary therapeutic dose at the target site via targeted delivery and controlled or selective drug release. Mechanistically, this is achieved by conjugating specific ligands (e.g., antibodies, aptamers) to the MSN surface. This functionalization converts the nanoparticle's non-specific biodistribution into a highly specific interaction with target cell receptors, resulting in enhanced cellular uptake at the disease site. As a consequence, tumor targeting efficacy is significantly improved, which allows for a higher local drug concentration and a more potent therapeutic outcome with reduced systemic side effects. This effectively overcomes multidrug resistance [127,128]. Among various nanoparticles, MSNs have been intensively investigated in the past two decades, especially for their promising potential in targeted drug delivery [129]. By means of targeted delivery and controlled drug release, MSNs can remarkably improve drug utilization at the target site. Consequently, the required dosage is reduced, demonstrating significant clinical value.

For example, He and colleagues successfully proposed an organically bridged, trypsin-responsive MSN matrix, SL@M@Arg-MSNs@BA, which was functionalized with pancreatic acinar cell (PAC)-targeting peptides SLIGRL. This matrix was designed to specifically target PACs for the precise treatment of acute pancreatitis (AP) (Fig. 6A) [112]. Specifically, the mesenchymal stem cell membrane layer and the surface functionalization with PAC-targeting ligands DSPE-PEG-SLIGRL enabled MSNs to recruit inflammatory cells and accurately target PACs. As a result, there was a peak distribution in the pancreas at 3 h, and the accumulation was 4.7 times higher compared to bare MSNs. After the skeleton of the bioinspired MSNs was degraded by over-activated trypsin, BAPTA-AM was released on demand in damaged PACs. This effectively removed the intracellular calcium overload, restored cellular redox homeostasis, halted the inflammatory cascade, and inhibited cell necrosis by suppressing the CaMK-Ⅱ/p-RIP 3/pMLKL/caspase-8,9 and IκBα/NF-κB α/TNF-α/IL-6 signaling pathways. In vivo experiments showed that SL@M@Arg-MSNs@BA significantly restored pancreatic function, decreased lipase and amylase levels, and increased the survival rate of mice. In conclusion, the specifically targeted SL@M@Arg-MSNs@BA developed in this study represents a potentially promising strategy using PAC-targeting peptides for the clinical application of AP treatment. Nevertheless, this nanoplatform has so far only been validated for loading the calcium chelator BAPTA-AM, and its applicability to other anti-arthritic drugs remains unverified. Considering the significant differences in physicochemical properties (such as molecular weight and hydrophilicity/hydrophobicity) among various drugs, these factors may affect drug loading efficiency, release kinetics, and synergistic therapeutic effects. Therefore, validation with a single drug is insufficient to fully demonstrate the versatility and adaptability of this platform, and further studies are needed to evaluate its broader applicability.

Fig. 6.

(A) Schematic illustration of the SL@Arg-MSNs@BA preparation. (B) Schematic illustration of the MSN synthesis using a heterobifunctional PEG crosslinker. (C) The MAL terminus of MSN-PEG reacts with the sulfhydryl groups of the antibody and the Cys-TAT peptide. (D) Schematic illustration of the nucleus and mitochondria dual-targeted nanoplatform Mito(T)-pep-Nuc(T). (E) Fluorescence confocal images of mitochondrial targeting and (F) corresponding analysis. (G) Fluorescence confocal images of nuclear targeting and (H) corresponding analysis. (A) Reproduced with permission [112]. Copyright 2024, American Chemical Society. (B, C) Reproduced with permission [113]. Copyright 2020, Elsevier. (D–H) Reproduced with permission [114]. Copyright 2019, Springer Nature.

The transcription factor NF-κB (p65/p50) is recruited to the cytoplasm by its inhibitor IκBα. Once activated, the Rel proteins p65/p50 are released from IκBα and translocated through nuclear pores. This process regulates the expression of numerous genes and makes NF-κB a potential target for cancer therapy. In the study by Mou et al., the NF-κB-targeting nanoparticle/antibody complex MSN-PEG-Ab-TAT, which consists of MSN, the TAT peptide, and a p65-specific antibody, was employed to capture the perinuclear domain Rel protein p65. This disrupted its translocation near the nuclear pore (Fig. 6B and C) [113]. The surface modification of MSNs with TAT peptides promotes non-endocytic cell membrane transduction and facilitates their accumulation in the perinuclear region. In this region, p65-specific antibodies can effectively target and capture active NF-κB p65. Furthermore, the combined treatment of mice with MSNs and Dox demonstrated significant therapeutic efficacy in 4T1 tumor-bearing mice. The novel therapeutic approach using antibody-surface-modified MSNs, which takes advantage of the “nuclear focusing” and “size-exclusion blocking” effects to target transcription factors, is versatile and can be adapted to regulate other transcription factors.

In contrast to targeting a single agent, surface-modified MSNs capable of dual-substance targeting can further boost targeting efficiency, significantly minimizing the side effects of therapeutic agents. For example, Hu and colleagues developed a nanocomplex, Mito(T)-pep-Nuc(T), which contains W18O49 nanoparticles and MSNs. This nanocomplex can simultaneously target the nucleus and mitochondria via triphenyl phosphonium and the nuclear localization sequence, respectively, for eradicating unresectable liver metastases (Fig. 6D) [114]. Briefly, the nuclear-gated tungsten oxide nanoparticles (WONP) were conjugated to mitochondria-specific MSNs containing the photosensitizer Ce6 through cathepsin B-cleavable peptides. Upon laser irradiation, the reactive oxygen species (ROS) generated by hepatocytes were scavenged by WONP, leading to the loss of its photothermal heating ability and protecting hepatocytes from laser-induced thermal damage. In hepatic metastatic cancer, the cleavable peptide linker allowed WONPs and MSNs to separately target the nucleus and mitochondria (Fig. 6E–H), enabling synergistic photodynamic and photothermal therapy for cancer elimination.

In summary, targeted modification strategies, whether employing antibodies, peptides, or other ligands, fundamentally rely on specific ligand-receptor interactions to achieve active targeting. Antibody-based targeting offers unparalleled specificity but is often hindered by high cost, large size, and potential immunogenicity. In contrast, peptide-based targeting provides a smaller, more cost-effective alternative with better tissue penetration, though its binding affinity may be lower. The choice of strategy is therefore highly dependent on the application scenario: for diseases with highly specific and well-characterized biomarkers (e.g., HER2+ cancer), antibodies are superior; for broader applications requiring deep tissue access, peptides may be more pragmatic. A key challenge remains in balancing targeting efficiency with off-target effects and systemic clearance.

3.2. Biomimetic modification

Despite the substantial progress in nanomaterials over the past decade, the biocompatibility of materials remains a key concern for researchers. This is because it determines the materials' capacity to adapt to host responses in vivo [[130], [131], [132]]. Biomaterials used for vascular grafts or stents usually necessitate cytotoxicity evaluation via cell viability assays and hemocompatibility tests. Further to this, biodegradability is of particular importance for special materials like absorbable stents, as these are engineered to offer only temporary functionality [133]. Significantly, the biocompatibility of various nanomaterials can be regulated through biomimetic surface modifications [[134], [135], [136], [137]]. These modifications fundamentally alter the nanoparticle's surface chemistry and zeta potential, which directly governs its interaction with blood opsonins and immune cells. A successful modification can transform a recognizable foreign particle into a “self-like" entity, thereby modulating the immune response, prolonging circulation half-life, and ultimately dictating its biodistribution. The past decade has witnessed the extensive applications of inorganic nanoparticles with outstanding biocompatibility in emerging nanocatalytic tumor therapy [[138], [139], [140], [141], [142], [143]].

For instance, the outstanding biocompatibility of MSN nanocomposites can be achieved through surface modification with PEG. Shi et al. developed a biomimetic PEG-modified MSN-based nanoplatform, DMSN-Au-Fe3O4, which consists of ultrasmall Au and Fe3O4 NPs. This was done to enhance biocompatibility and physiological stability for nanocatalytic tumor therapy (Fig. 7A) [115]. The Au NPs emulated glucose oxidase, while the Fe3O4 NPs mimicked peroxidase. The Au NPs selectively oxidized β-D-glucose into gluconic acid and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2). Subsequently, the Fe3O4 NPs catalyzed this H2O2 to generate ROS, thereby inducing tumor cell death. Importantly, cytotoxicity assays verified the high biocompatibility and biosafety of the nanoplatform (Fig. 7B). In vivo hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) staining assays showed significant tumor cell damage and necrosis in the group treated with the nanoplatform, demonstrating the excellent therapeutic efficacy of the biomimetic PEG-modified nanoplatform (Fig. 7C). Overall, this research presents a rational design for a biomimetic PEG-modified MSN-based nanoplatform, enabling efficient and safe nanocatalytic tumor therapy. Even though, DMSN-Au-Fe3O4 nanoplatform primarily relies on the EPR effect of tumor vasculature to achieve passive targeting, without the incorporation of active targeting ligands. As a result, its targeting efficiency may be relatively limited. Further studies introducing active targeting strategies could potentially improve the tumor accumulation and therapeutic efficacy of such nanoplatforms.

Fig. 7.

(A) Schematic diagram of nanocatalytic oncology therapy with “non-toxic drugs” via biomimetic inorganic nanomedicine-activated cascade catalytic reaction. (B) Relative viability in 4T1 cells after incubation with different concentrations of DMSN-Au-Fe3O4. (C) H&E staining, TUNEL staining to observe pathological alterations and Ki-67 immunohistochemical staining to observe cell proliferation of tumor tissues in each group after 15 days treatment period. Scale bar: 100 μm. (D) Schematic diagram of ESC-HCM-B preparation. (E) Schematic illustration of the design of superlubricated nanospheres. (A–C) Reproduced with permission [115]. Copyright 2019, Wiley. (D) Reproduced with permission [116]. Copyright 2023, American Chemical Society. (E) Reproduced with permission [117]. Copyright 2020, Elsevier.

PEG modification improves the biocompatibility of MSNs, biomimetic composite membrane modification is also an excellent alternative. For example, Zeng et al. reported a multifunctional MSNs-based nanocomposite, ESC-HCM-B, modified with an enhanced biohomogeneous composite membrane. This nanocomposite is designed for the targeted release of ROS inhibitors and mTOR to enhance biocompatibility for the synergistic treatment of diabetic nephropathy (DN) (Fig. 7D) [116]. MSNs endow the ESC-HCM-B nanocomposite with a high drug-loading capacity. Due to the presence of the biomimetic composite membrane, ESC-HCM-B can avoid immune phagocytosis, enable self-valve-controlled drug release, and maintain high stability. In vitro, ESC-HCM-B demonstrates excellent podocyte-targeting efficiency, without significant cytotoxicity or pro-apoptotic effects. In in vivo experiments, ESC-HCM-B can specifically target the glomerular and podocyte regions of the kidney. Additionally, ESC-HCM-B reduces high glucose-induced ROS levels in podocytes and restores mitochondrial energy metabolism. Importantly, ESC-HCM-B significantly reduces urinary protein levels in DN rats and delays glomerulosclerosis. Overall, this biomimetic MSN-based nanocomposite, through surface modification with a biomimetic composite membrane, offers a safe and effective strategy for DN treatment.

Beyond their applications in tumor and DN treatments, surface-modified biomimetic MSNs are also employed in the treatment of osteoarthritis. Inspired by the structure of phosphatidylcholine lipids, a typical constituent of the cartilage matrix, Zhang and colleagues fabricated superlubricating poly(2-methacryloyloxyethyl phosphorylcholine)-modified nanopolymers, namely MSNs-NH2@PMPC, via photopolymerization. This was done to enhance biocompatibility for the efficient treatment of osteoarthritis (Fig. 7E) [117]. The surface-functionalized modification with poly(2-methacryloyloxyethyl phosphorylcholine) imparted excellent lubrication properties to MSNs-NH2@PMPC. MSNs-NH2@PMPC improved lubrication due to the formation of a robust hydration layer around the zwitterionic charges of the nanopolymers. Meanwhile, the use of MSNs enabled the targeted delivery of anti-inflammatory drugs. Experimental findings indicated that the superlubricating drug-loaded nanopolymers impeded the progression of osteoarthritis by increasing cartilage anabolic components and suppressing pain-related genes and catabolic proteases. The fabricated nanopolymers MSNs-NH2@PMPC, featuring excellent lubrication and sustained drug delivery capabilities, show great potential as an effective intra-articular nanomedicine for the treatment of osteoarthritis.

Collectively, the biomimetic modifications discussed highlight two core design principles: “stealthing" and “camouflaging." PEGylation (e.g., DMSN-Au-Fe3O4) exemplifies the “stealth" approach, creating a hydrophilic layer to passively evade immune surveillance. In contrast, cell membrane coating (e.g., ESC-HCM-B) and matrix-mimicking polymers (e.g., MSNs-NH2@PMPC) represent “camouflage," actively mimicking endogenous structures to achieve superior biocompatibility and, in some cases, homologous targeting. The choice of strategy depends on the desired balance between simplicity (PEGylation) and functional complexity (membrane coating), with the latter offering more sophisticated biological interactions at the cost of a more complex fabrication process.

3.3. Stimuli-responsive strategies for surface modification

The open mesopores of MSNs facilitate the relatively easy loading of therapeutic agents into their pores. However, these agents can freely diffuse out through the same routes, significantly diminishing their efficacy and potentially exacerbating certain side effects. Thus, it is crucial to devise various strategies to close the pore entrances and prevent the unintended release of the cargo. Over the past several years, numerous strategies have been developed for MSN-based smart nanocarriers to seal the pore gates, enabling the on-demand release of therapeutic agents in response to specific stimuli. In this subsection, we elaborate in detail on the fashionable pH-responsive and ROS-responsive strategies for the surface modification of MSNs.

3.3.1. pH-responsive strategies

The pH-stimulated system is a standard stimulus-responsive drug delivery platform, especially suitable for tumor-targeted release. The tumor microenvironment is weakly acidic (pH 5.5–7.0), which can act as a stimulus for the targeted release of drugs from carriers into tumors [144,145].

Zhang et al. engineered a multifunctional nanosystem based on MSNs modified with tungsten disulfide quantum dots (WS2-HP), namely DOX@MSN-WS2-HP. This nanosystem was functionalized via a benzoic-imine bond to achieve pH responsiveness. It functioned as a pH-responsive “cluster bomb” and was conjugated with the tumor-homing/penetrating peptide tLyP-1 for efficient tumor suppression (Fig. 8A) [118]. The pH-responsive benzoic-imine bond connected the “cluster bomb” and the “distributor,” remaining stable under normal physiological conditions. Nevertheless, upon reaching the weakly acidic tumor microenvironment, the nanosystem dissociated into two components in a responsive manner. One component was DOX@MSN-NH2, which enabled effective chemotherapy for tumors. The other component was WS2-HP, which demonstrated excellent tumor-penetrating ability for near-infrared (NIR) light-activated PTT in deep tumor cells (Fig. 8B and C). Experimental results indicated that the pH-responsive DOX@MSN-WS2-HP, achieved through benzoic-imine bonds, exhibited specific cytotoxicity against tumor cells, demonstrating significant antitumor effects and holding promising potential for clinical applications.

Fig. 8.

(A) Schematic illustration of the preparation and application of DOX@MSN-NH2. (B) Cumulative DOX release profiles of DOX@MSN-WS2-HP at different pH conditions. (C) Flow cytometry analysis of cells after various treatments. (D) Representative TEM images of MSN. (E) Representative TEM images of MSN@DA. (F) Schematic illustration of MSN@DA synthesis. (G) Schematic synthesis of pH-responsive MSNATU@DOX nanoplatforms. (A–C) Reproduced with permission [118]. Copyright 2017, American Chemical Society. (D–F) Reproduced with permission [119]. Copyright 2019, Wiley. (G) Reproduced with permission [120]. Copyright 2017, Elsevier.

Borate ester bonds, together with benzoic-imine bonds, act as pH-responsive chemical linkages that are crucial in smart nanomedicine delivery systems, facilitating the specific release of therapeutic agents. To achieve the responsive delivery of the anti-angiogenic drug dopamine, Nie and colleagues synthesized an MSN-based Dox-loaded nanoplatform, MSN@DA, which enables the pH-responsive release of dopamine through the breakage of boronic ester bonds to enhance the anti-tumor effect (Fig. 8D–F) [119]. Specifically, MSNs were functionalized with amine-conjugated phenylboronic acid molecules, allowing dopamine to be loaded via the formation of boronate esters. Under weakly acidic conditions, the boronate ester bonds between dopamine and phenylboronic acid on MSNs undergo hydrolysis, enabling precisely controlled dopamine release. This smart delivery system significantly inhibits the migration and tube formation of vascular endothelial cells. Loading dopamine into functionalized MSNs not only significantly extends the circulation half-life of this small molecule but also induces tumor vessel normalization, thereby enhancing the chemotherapeutic efficacy of Dox. This research indicates that pH-responsive MSNs show great potential for in vivo dopamine delivery. The tumor vessel normalization effect induced by dopamine represents a promising adjuvant strategy for cancer chemotherapy.

Apart from benzoic-imine bonds and borate ester bonds, the acetal linker is frequently utilized as a pH-responsive modification component to further boost the efficiency of diagnostic and therapeutic applications. For example, Vallet-Regí et al. have successfully developed a pH-responsive, acetal linker-modified, versatile MSN-based nanoplatform, MSNConA, for Dox loading for the treatment of osteosarcoma [120]. This nanoplatform consists of two crucial components: a pH-responsive acetal linker for precise drug delivery and a targeting ligand for specific recognition and selective tumor cell targeting (Fig. 8G). When compared with healthy pre-osteoblastic cells (MC3T3-E1), this multifunctional nanoplatform exhibits significantly enhanced internalization efficiency in SA-overexpressing human osteosarcoma cells. Their results indicated that the nanoplatform demonstrated an 8-fold higher cytotoxicity towards tumor cells compared to free drugs, leading to nearly 100 % death of osteosarcoma cells. The synergistic integration of different structural components has enabled the construction of a unique nanoplatform that not only enhances the antitumor efficacy but also reduces the toxicity to normal cells. These findings strongly support the crucial role of pH-responsive MSN-based nanoplatforms in the targeted therapy of osteosarcoma.

3.3.2. ROS-responsive strategies

ROS, encompassing H2O2, singlet oxygen (1O2), hydroxyl radicals (•OH), and superoxide anions (O2•-), typically exhibit lower concentrations in normal tissues when contrasted with the tumor microenvironment (TME), inflamed tissues, or other damaged areas [[146], [147], [148]]. Consequently, researchers have engineered diverse ROS-responsive nanomaterials for the diagnosis and treatment of diseases like tumors and inflammation.

For example, the excessive accumulation of ROS elicits oxidative stress responses in patients with long-term diabetes. This results in bone fragility and an elevated risk of fracture. Oxidative stress is a characteristic trait of diabetes mellitus, playing a pivotal role in disease progression, the development of complications, and the emergence of drug resistance. To enhance the treatment of diabetes, Wang's research team pioneered the fabrication of an innovative ROS-responsive drug delivery nanoplatform, PMS/PC. This nanoplatform utilizes phenyl sulfide mesoporous silica nanoparticle (PMS) as a matrix for encapsulating proanthocyanidin (PC), thereby establishing a potential therapeutic approach for promoting bone formation under diabetic conditions (Fig. 9A) [121]. The synthesized spherical PMS particles exhibited a highly ordered two-dimensional hexagonal mesoporous structure, which significantly augmented their loading capacity for PC molecules. The wettability of the inner surface of the nanopores in PMS could be effectively regulated through surface modification with hydrophobic PhS groups.

Fig. 9.

(A) Schematic diagram of the ROS-responsive PMS/PC delivery system, its function and potential mechanisms. (B) Schematic illustration of MSN@TheraVac synthesis. (C) Representative scanning electron microscope image of MSN. (D) Cumulative release profile of various drugs at different pH conditions. (A) Reproduced with permission [121]. Copyright 2022, Elsevier. (B–D) Reproduced with permission [122]. Copyright 2023, American Chemical Society.

Also, the PhS groups endow PMS/PC with ROS responsiveness. Specifically, under ROS stimulation, the hydrophobic PhS groups can be oxidized into hydrophilic phenyl sulfoxide or phenyl sulfone groups featuring electron-withdrawing properties. This transition in wettability effectively modulates the surface properties of the nanopores, thereby triggering the release of the loaded PC. Subsequently, the intelligent drug release performance of the PMS/PC nanoplatform under ROS stimulation was systematically investigated in experiments. The experimental findings revealed that the responsive release of PC from the ROS-sensitive PMS/PC delivery system, combined with its dual functions of eliminating excessive ROS and regulating ROS levels, effectively maintains intracellular ROS homeostasis. PMS/PC effectively mitigates vascular oxidative stress by suppressing the excessive generation of ROS, promoting the synergistic coupling between angiogenesis and osteogenesis. This significantly enhances osteoblast differentiation in vitro and substantially improves bone formation capacity in vivo. In summary, the ROS-responsive PMS/PC nanoplatform exhibits remarkable therapeutic potential for the treatment of diabetic osteopathy, holding promising application prospects in suppressing oxidative stress induced by excessive ROS.

MSNs have emerged as one of the most promising nanocarriers in drug delivery systems. This is attributed to their outstanding biocompatibility, tunable size characteristics, straightforward synthesis process, and low production costs [149,150]. However, conventional MSNs face significant limitations in peptide or protein delivery due to their restricted pore sizes and insufficient biodegradation kinetics. To address this challenge, Yang et al. engineered a novel type of large-pore MSNs, namely MSN@TheraVac, with ROS-responsive properties. These were specifically designed for the efficient delivery of therapeutic vaccines (TheraVac), a potent therapeutic cancer vaccine. TheraVac consists of HMGN1, R848, and αPD-L1 antibodies and is used for tumor-specific immunity treatment (Fig. 9B) [122]. HMGN1 and R848 were successfully encapsulated within the enlarged mesopores of the MSNs. Meanwhile, αPD-L1 antibodies were conjugated to the nanoparticle surface via diselenide bonds and PEG-based crosslinkers (Fig. 9C). This innovative design facilitated rapid and precise drug release in response to the elevated ROS levels that are characteristic of the TME. This was achieved because the diselenide bonds underwent efficient cleavage under such conditions. Specifically, upon arriving at the tumor site, the αPD-L1 antibodies exhibited ROS-responsive release via the oxidative cleavage of diselenide bonds within the TME (Fig. 9D). This precisely regulated release mechanism enabled effective binding to PD-1-expressing cells, thereby alleviating immunosuppression and preventing the exhaustion of effector T cells. Overall, the ROS-responsive MSN nanoplatform showcases remarkable potential as an advanced cancer vaccine delivery system. It demonstrates potent antitumor efficacy while effectively overcoming the inherent limitations associated with the administration of TheraVac.

Beyond diselenide bonds functioning as ROS-responsive linkers, thioketal (TK) groups have emerged as a widely utilized and well-established class of ROS-cleavable linkages in drug delivery systems. For example, Lee et al. reported an innovative MSN-based TK-conjugated nanoplatform, Ar-MSNs-TK-PEG, which features ROS-triggered surface charge reversal. This enables efficient delivery of the humanin peptide to retinal pigment epithelial cells (ARPE-19) for the effective treatment of neovascular retinal diseases [123]. Specifically, the surface engineering strategy entailed incorporating 20 % acetyl-L-arginine (Ar) to confer partial positive charges, while conjugating 80 % TK-linked methoxy polyethylene glycol (mPEG) as an ROS-responsive shielding layer. This achieved precise control over the nanoparticle's properties. The engineered MSNs leverage their oxidation stress-responsive charge reversal properties to achieve sustained retention within the anionic vitreous network. Conversely, the study did not directly compare the Ar-MSNs-TK-PEG drug delivery system with currently used clinical therapies. Consequently, it remains unclear whether this nanoplatform offers specific advantages over existing treatments with regard to efficacy, safety, therapeutic cost, and patient compliance. This limitation hinders a comprehensive evaluation of its potential for clinical translation.

Additionally, they facilitate targeted diffusion to retinal cells upon exposure to oxidative stress conditions. These MSNs exhibited an exceptional peptide loading capacity while maintaining excellent biocompatibility, as indicated by the undetectable toxicity in both retinal cells and ocular tissues. The protective properties of MSNs functioned as an efficient barrier system. This system effectively minimized premature drug release and guaranteed the stability of the payload until the intended retinal targets were reached. Both in vitro and in vivo experimental findings indicated that this innovative strategy significantly augmented the therapeutic potential of the encapsulated drugs, presenting promising prospects for enhancing clinical treatment outcomes. In conclusion, the developed ROS-responsive nanoplatform, Ar-MSNs-TK-PEG, exhibits remarkable efficacy in alleviating oxidative stress and preventing the formation of retinal neovascularization.

As discussed, stimuli-responsive strategies utilize a variety of chemical linkers to achieve controlled release. A critical comparison reveals distinct advantages and limitations. Benzoic-imine bonds and acetal linkers are both pH-sensitive, but they respond to different pH ranges; imine bonds typically cleave in the mildly acidic tumor microenvironment (pH ∼6.5), making them ideal for extracellular release, whereas acetal linkers often require the lower pH of endo/lysosomes (pH ∼5.0) for efficient cleavage, suiting them for intracellular drug delivery. Boronic ester bonds also offer pH-responsiveness but with the unique ability to bind with diols, enabling a different mode of cargo attachment. For ROS-responsiveness, diselenide bonds are highly sensitive to the redox environment but can be less stable in circulation, while thioketal (TK) linkers are specifically cleaved by higher ROS levels found inside cancer cells, offering better stability and specificity. Therefore, the selection of a specific linker must be carefully matched to the biological barrier it is designed to overcome and the specific subcellular location targeted for drug release.

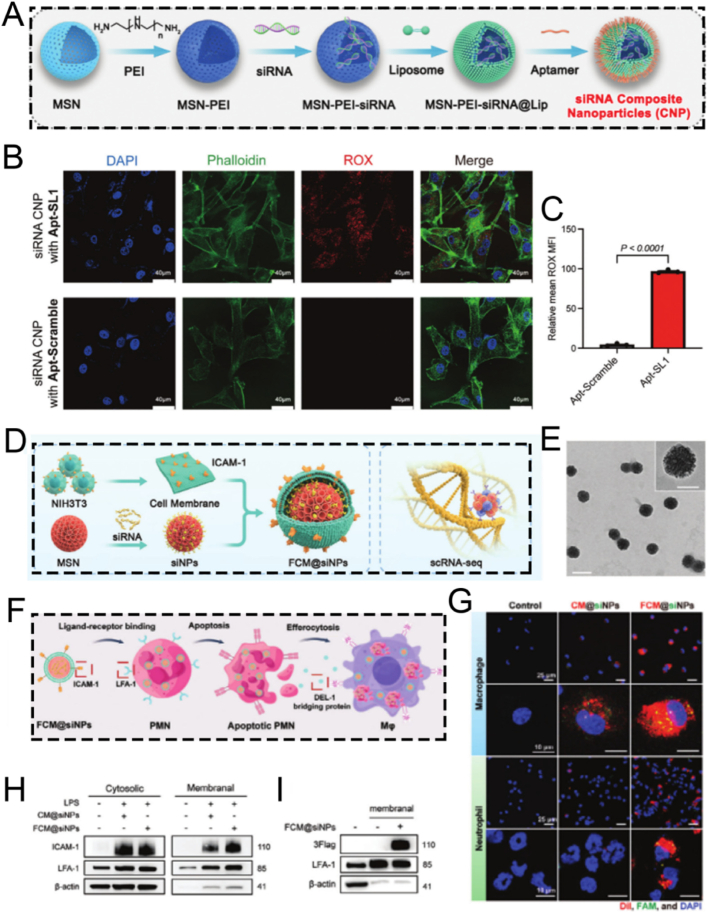

3.4. Strategies for surface modification using aptamers

Aptamers, a class of functional oligonucleotide molecules featuring unique three-dimensional structures, are derived via in vitro screening techniques, such as Systematic Evolution of Ligands by Exponential Enrichment (SELEX) [[151], [152], [153]]. These molecules are celebrated for their high specificity and potent binding affinity in the nanomolar or even picomolar range. This property endows them with the ability to precisely recognize and bind to a diverse array of biological targets, including proteins, peptides, carbohydrates, small molecule compounds, toxins, and even intact living cells [[154], [155], [156]]. In the realm of drug delivery, aptamers function as innovative targeting ligands. By specifically recognizing surface markers on target cells, they can facilitate precise drug delivery [157,158]. This not only significantly enhances the selectivity and efficacy of treatments but also mitigates toxic side effects on non-target tissues. The remarkable targeting capabilities of aptamers underscore their extensive application potential in targeted therapy, molecular diagnostics, and biosensing [[159], [160], [161]]. Sclerostin antibody has the potential to reactivate osteoblasts, augment bone mass and strength, and might serve as a specific targeted agent for the treatment of osteoporosis.

Consequently, Zhou et al. devised a novel and facilely synthesized bone-targeting nanomedicine (DNA-MSN, DNAM), which consists of polyethylene glycol-modified dendritic MSN and a sclerostin-targeting DNA aptamer (AptScl56). This nanomedicine is designed to direct bone attachment and capture sclerostin for the precise treatment of osteoporosis (Fig. 10A) [124]. The mesoporous structure of MSN effectively protects the immobilized AptScl56 from accelerated degradation or renal filtration, thus prolonging it's in vivo half-life. Given the interaction between the bone calcium of hydroxyapatite and the phosphate groups of the DNA aptamer AptScl56, the DNAM-immobilized AptScl56 layer not only directly adheres to the bone tissue of ovariectomized mice but also captures sclerostin in situ with picomolar affinity, thereby exerting a dual therapeutic effect. Significantly, DNAM exhibited a remarkable ability to substantially reverse the elevated serum sclerostin levels, effectively restoring the osteoporosis-induced bone loss to physiological levels. It also enhances the mechanical properties of femoral bone tissue and morphological parameters, normalizes serum bone turnover markers, and shows no systemic toxicity. This study introduces a novel MSN-based nanoplatform characterized by DNA aptamer-mediated surface functionalization, presenting a promising strategy for nanomedicine-based therapeutic interventions in the treatment of osteoporosis. Nonetheless, this study employed only the ovariectomized mouse model to simulate postmenopausal osteoporosis, without incorporating other types of osteoporosis models. Given the substantial differences in pathological mechanisms among various forms of osteoporosis, validation in a single model may not fully capture the therapeutic applicability and universality of this nanoparticle across different etiologies. Therefore, further studies utilizing a broader range of osteoporosis models are warranted to comprehensively evaluate the versatility and translational potential of this nanoplatform.

Fig. 10.

(A) Schematic illustration of the synthesis of DNAM and its application as a bone-targeting ligand. (B) Schematic diagram of aptamer theranostic platform InCasApt. (C) Cartoon on the left and secondary structure on the right of the aptamer DNBApt. (D) Binding of the DNBApt-TS complex capable of conjugating Ce6-DN (upper panel) and the secondary architecture of the DNBApt-TS complex (lower panel). (E) Impermissible Ce6-DN binding for the formation of the DNBApt-miRNA-21 compound (top) and the secondary architecture of the DNBApt-miRNA-21 compound (bottom). (A) Reproduced with permission [124]. Copyright 2022, Elsevier. (B–E) Reproduced with permission [125]. Copyright 2024, American Chemical Society.