Graphical abstract

Keywords: Glycyrrhiza, Species classification, Pharmacology, Transcriptional regulation, Synthetic biology

Highlights

-

•

Glycyrrhiza species mainly offer triterpenoids, flavonoids, and polysaccharides with diverse therapeutic effects.

-

•

The review covers Glycyrrhiza species classification, pharmacology, biosynthesis of active compounds, and synthetic biology advancements.

-

•

Research on population genomics, active compounds biosynthesis, and molecular breeding in Glycyrrhiza is key to its future applications.

-

•

Breeding high-yield Glycyrrhiza plants and optimizing biosynthesis of bioactives support resource conservation and drug development.

-

•

Metabolic engineering and green microbial methods boost production efficiency of natural products in licorice.

Abstract

Background

Licorice is extensively and globally utilized as a medicinal herb and is one of the traditional Chinese herbal medicines with valuable pharmacological effects. Its therapeutic components primarily reside within its roots and rhizomes, classifying it as a tonifying herb. As more active ingredients in licorice are unearthed and characterized, licorice germplasm resources are gaining more and more recognition. However, due to the excessive exploitation of wild licorice resources, the degrading germplasm reserves fail to meet the requirements of chemical extraction and clinical application.

Aim of Review

This article presents a comprehensive review of the classification and phylogenetic relationships of species in genus Glycyrrhiza, types of active components and their pharmacological activities, licorice omics, biosynthetic pathways of active compounds in licorice, and metabolic engineering. It aims to offer a unique and comprehensive perspective on Glycyrrhiza, integrating knowledge from diverse fields to offer a comprehensive understanding of this genus. It will serve as a valuable resource and provide a solid foundation for future research and development in the molecular breeding and synthetic biology fields of Glycyrrhiza.

Key Scientific Concepts of Review

Licorice has an abundance of active constituents, primarily triterpenoids, flavonoids, and polysaccharides. Modern pharmacological research unveiled its multifaceted effects encompassing anti-inflammatory, analgesic, anticancer, antiviral, antioxidant, and hepatoprotective activities. Many resources of Glycyrrhiza species remain largely untapped, and multiomic studies of the Glycyrrhiza lineage are expected to facilitate new discoveries in the fields of medicine and human health. Therefore, strategies for breeding high-yield licorice plants and developing effective biosynthesis methods for bioactive compounds will provide valuable insights into resource conservation and drug development. Metabolic engineering and microorganism-based green production provide alternative strategies to improve the production efficiency of natural products.

Introduction

The members of genus Glycyrrhiza, which belongs to subfamily Papilionoideae of family Leguminosae, are perennial herbaceous plants. They have a global distribution, with main production areas in Asia and Europe and a small number found in the tropical and subtropical regions of America and Africa. China is the central zone of licorice resources and is the world’s largest consumer and exporter of licorice [1]. Glycyrrhiza species are widely used in medicine, with G. uralensis, G. glabra, and G. inflata as the source plants for licorice herbal medicine in Chinese, European, and Korean pharmacopoeias [2], [3]. Licorice is one of the traditional Chinese herbal medicines, and its medicinal parts are its roots and rhizomes. It possesses various medicinal properties, such as tonifying the spleen and replenishing qi, clearing heat and detoxification, resolving phlegm and relieving cough, relieving pain, and harmonizing various medicines [3]. In China, licorice is one of the most commonly used bulk medicinal materials, and countries such as the United States and Japan also refer to licorice as “Fairy Herb” or “Divine Herb” [2], [4], [5].

Glycyrrhiza plants contain a rich variety of active components, with over 400 secondary metabolites identified [6], [7]. Among them, triterpenoids and flavonoids are two crucial classes of chemical compounds that determine the medicinal effects of licorice. Modern pharmacological research found that licorice has multiple effects, including anti-inflammatory, analgesic, anticancer, antiviral, antioxidant, and hepatoprotective properties [8], [9], [10], [11], [12]. In addition to its medicinal uses, licorice is also employed as an additive and flavoring agent in various industries, such as food, tobacco, cosmetics, and animal husbandry [13], [14]. In addition, licorice is a wild sand-fixing plant under national key protection and management. It protects the ecological environment and prevents land desertification [15]. Owing to its wide-ranging applications and high market demand, licorice has been excessively harvested from the wild, leading to remarkable ecological damage to wild licorice populations and the subsequent scarcity of wild licorice resources [16]. Therefore, cultivated licorice has become the primary source to meet market demand [17]. Owing to the influence of environmental factors and licorice genetic factors, the active ingredients significantly differ between cultivated and wild licorice. In particular, the active ingredients in cultivated licorice are generally fewer and do not meet pharmacopoeia standards. Therefore, cultivated licorice is often diverted to nonmedicinal industries, such as food or confectionery, severely constraining the sustainable development of licorice as a medicinal resource [18]. The importance of key traits and quality in licorice breeding must be emphasized. Therefore, strategies for selecting high-yield licorice plants and developing effective in vivo or in vitro biosynthesis methods for bioactive compounds will provide valuable insights into drug development and resource conservation.

This article provides an overview of the classification, phylogenetic relationships, and pharmacology of Glycyrrhiza species. It discusses licorice genomics and the biosynthetic pathways of active compounds. Finally, it explores the prospects for metabolic engineering and breeding of licorice. Furthermore, it presents future prospects for the development and utilization of Glycyrrhiza resources.

Classification and phylogenetic relationships of Glycyrrhiza species

Genera Glycyrrhiza and Glycyrrhizopsis constitute the Glycyrrhizeae tribe within the licorice family. Licorice holds significant and diverse applications, but its intergeneric and intrageneric taxonomy is controversial. This situation has implications for the medicinal, industrial, and scientific utilization of licorice and the collection and breeding of licorice germplasm resources. For instance, nonmedicinal species have been sold as medicinal licorice in the market, and some scientific studies on pharmacology or chemistry have utilized misidentified licorice materials. Hence, precise and specific delineation is crucial for the proper application of licorice.

Genera Meristotropis and Glycyrrhizopsis were initially considered as subsidiaries of the Glycyrrhiza genus. Whether Meristotropis and Glycyrrhizopsis should be included or excluded from the Glycyrrhiza genus has been debated throughout various taxonomic revisions at the intergeneric level. Some argued that both should be part of the Glycyrrhiza genus, and others proposed that they should remain independent genera. Some suggested that Meristotropis and Glycyrrhiza should be merged into a single Glycyrrhiza genus, with Glycyrrhizopsis as a separate genus [19], [20], [21]. Within the Glycyrrhiza genus, taxonomists have classified licorice species using a series of morphological characteristics, including the number of leaflets per leaf, inflorescence/fruit cluster shape, fruit shape, and fruit appendages. However, a significant number of transitional morphological features have blurred the specific boundaries of licorice species. The Glycyrrhiza genus has undergone five major revisions, resulting in varying species counts ranging from 13 to 36 species [22]. Hence, the debate regarding the current species limitations within the Glycyrrhiza genus is still ongoing.

The latest research involved extracting low-copy nuclear genes from shallow genome sequencing data and constructing phylogenetic trees using chloroplast genomes and nuclear ribosomal DNA. Classification and phylogenetic studies combined this approach with morphological characteristics and specimen image recognition [22], [23]. The results revealed that the Central Asian endemic genus Meristotropis should be merged into the Glycyrrhiza genus, resulting in the inclusion of the following 13 species within this genus: G. acanthocarpa, G. astragalina, G. bucharica, G. echinata, G. foetida, G. glabra, G. gontscharovii, G. lepidota, G. macedonica, G. pallidiflora, G. squamulosa, G. triphylla, and G. yunnanensis. This study proposes a broad concept of G. glabra, which now includes the previously classified G. uralensis, G. glabra, G. inflata, and G. aspera representing the medicinal group containing glycyrrhizic acid. The sister genus, Glycyrrhizopsis, is endemic to the Western Anatolia Plateau in Western Asia and comprises only two species: G. asymmetrica and G. flavescens.

Not all species within the Glycyrrhiza genus are considered medicinal plants. Only species with glycyrrhizic acid in their roots have medicinal value, constituting the medicinal group. The ancestors of the Glycyrrhiza genus lack glycyrrhizic acid, and the medicinal groups in Eurasia share a common ancestor. Their descendants have all arisen from two rapid divergence events within the last million years [3], [19]. This phenomenon has also resulted in significant morphological overlap and a high confusion degree among subspecies within this group [22]. As mentioned earlier, the medicinal group is traditionally composed of four widely accepted species: G. uralensis, G. glabra, G. inflata, and G. aspera. However, recent research indicated that the North American species G. lepidota also contains glycyrrhizic acid, albeit in relatively low quantities [19], [24]. According to previous phylogenetic findings, the group containing glycyrrhizic acid is not monophyletic [25]. Although G. aspera contains glycyrrhizic acid, its long and relatively short roots yield a low quantity and it has therefore been considered unsuitable for medicinal or industrial purposes [19]. This circumstance may also explain why the Chinese Pharmacopoeia only includes G. uralensis, G. glabra, and G. inflata as licorice sources [3].

Although G. uralensis, G. glabra, and G. inflata are all medicinal species, their contents of active ingredients significantly differ, resulting in substantial variations in their quality and medicinal efficacy [26], [27], [28]. Accurate identification of these three species is essential to ensure the effectiveness and safety of clinical medication. However, these three original licorice species belong to the same genus, and their medicinal parts are their roots. Their microscopic characteristics are highly similar, making it difficult to effectively distinguish them through traditional trait identification and microscopic methods. Specific variable sites in the ITS/ITS2 and psbA-trnH sequences have been utilized for the identification of these three distinct original licorice species [29], [30]. In the ITS2 sequence, three mutation sites are located at positions 16–18 bp, which can be divided into two genotypes: I2-i (TGC), representing the single haplotype of G. uralensis; and I2-ii (CAA), representing the single haplotype of G. glabra and G. inflata. The ITS sequence at positions 187 and 411–413 bp (equivalent to positions 16–18 bp in the ITS2 sequence) can be classified into two genotypes: I-i (CTGC), representing the single haplotype of G. uralensis; and I-ii (TCAA), representing the single haplotype of G. glabra and G. inflata. The psbA-trnH sequence has three variant positions located at 189, 235, and 288 bp, which can be classified into four single haplotypes: PT-i (ACG), PT-ii (ATG), PT-iii (CTG), and PT-iv (ATA). Among them, PT-i and PT-ii are the haplotypes of G. uralensis, PT-iii is the haplotype of G. uralensis and G. glabra, and PT-iv is the haplotype of G. inflata. The combination of specific variable sites in the ITS/ITS2 and psbA-trnH sequences allows for the identification of these three licorice species.

Primary active constituents of Glycyrrhiza plants

Glycyrrhiza species exhibit a diverse array of chemical components. Among the predominantly reported chemical constituents, those primarily found in the three medicinal species include triterpenoids, flavonoids, polysaccharides, coumarins, alkaloids, volatile oils, and trace elements.

Triterpenoids

Triterpenoids are a major class of compounds in licorice. They are also a type of natural sweetener, consisting of polymers based on the unit of six molecules of isoprene. Triterpenoids are characterized by their high content, strong physiological activity, and high medicinal value. Their basic skeletal structure is typically composed of 3β-hydroxyoleanane-type pentacyclic triterpenoids, which can be considered β-amyrin derivatives [1]. The triterpenoid components in G. uralensis include glycyrrhizic acid, glycyrrhetinic acid, uralsaponin, and licoricesaponin, all of which are derivatives of 3β-oleanane-type compounds [31], [32]. The triterpenoid compounds isolated from G. glabra include glycyrrhizic acid, glycyrrhetinic acid, 29-hydroxyl-glycyrrizin, licoricesaponin, and 22β-acetoxyl-glycyrrizin [33], [34]. G. inflata constitutes over 60 % of wild licorice reserves in China [35] and contains triterpenoids such as glycyrrhizic acid, glycyrrhetinic acid, methyl glycyrrhetinate, 11-deoxyglycyrrhetinic acid, glycyrrhetinate acetylates, and 3-oxo-glycyrrhetinic acid [36], [37], [38], [39], [40].

Flavonoids

Flavonoids primarily refer to compounds with a basic nucleus of 2-phenylchromone. To date, over 300 flavonoids have been isolated and identified from Glycyrrhiza species worldwide [41]. The flavonoids in licorice can be categorized into flavones, flavonols, isoflavones, chalcones, dihydroflavones, dihydroisoflavones, and isoflavanes [42]. The types and quantities of flavonoids can vary in different species of licorice or in the same species from different geographical locations [43]. The flavonoids found in G. uralensis include liquiritin, liquiritigenin, licoflavonol, isolicoflavonol, glycyrol, licoricone, and glicoricone [44]; those found in G. glabra include liquiritin, liquiritigenin, glabridin, hispaglabridin, and 4ʹ-O-methylglabridin [45]; and those found in G. inflata include liquiritin, liquiritigenin, licochalcone, 3-OH licochalcone, licoagrochalcone, and 3,4-didehydroglabridin [36], [37], [38], [39], [40].

Polysaccharides

Polysaccharides are one of the active components of licorice. They have complex structures and diverse functions, and current research is mainly focused on their relationship with biological activities. The polysaccharides in G. uralensis are primarily composed of rhamnose monohydrate, dextran, arabinose, and galactose [46], [47]. In G. inflata, the predominant polysaccharide components are acidic polysaccharides, including L-arabinose, L-rhamnose monohydrate, D-glucose, D-galactose, and D-galacturonic acid [48]. Researchers have found variations in the polysaccharide content among different licorice varieties. Although the monosaccharide compositions are the same in the polysaccharides of different licorice varieties, there are differences in the proportions of these monosaccharides [49], [50].

Coumarins

Coumarin-type active ingredients are mainly found in G. uralensis. Their typical characteristic is the presence of a phenyl ring substitution on the carbonyl adjacent position, and their structure conforms to the C6-C3-C6 rule. Some scholars classify coumarins as flavonoid components; a minority of compounds in this group have a fused furan ring between the substituted benzene ring and the nucleus, forming coumestan (II)-type structures [1]. Lu et al. [51] investigated the chemical composition of waste residues from G. uralensis and discovered new coumarin-type compounds, naming them “huai coumarins”. Liu [52] first isolated 7,2ʹ,4ʹ-trihydroxy-5-methoxy-3-coumaranone from Glycyrrhiza plants. The chemical name of coumarin A in G. inflata is 4-(p-hydroxybenzene)-6-isoprenyl-7-hydroxycoumarin [53].

Alkaloids

Considerable research has focused on the analysis of flavonoid and triterpenoid components in licorice. Some studies were conducted on alkaloid components in licorice, but their variety of origin is often disregarded. Zhang et al. [54] found that the alkaloids in G. uralensis, G. inflata, G. glabra, and G. pallidiflora belong to the same category, possibly quinoline derivatives. The content of these alkaloids is relatively high and similar among the four licorice species. G. uralensis contains over six alkaloids with a mass fraction of 0.26 %.

Other components

In addition to the mentioned chemical components, licorice contains volatile oil compounds, amino acids, and trace elements. Ma et al. [55] determined that the major volatile components in G. uralensis roots are alkanes and aromatic hydrocarbons. Amino acids play a crucial role in tissue growth, metabolism, maintenance, and repair. G. uralensis is rich in amino acids, containing all eight essential amino acids required by the human body [56]. The trace elements in licorice roots may play a role in its authenticity and quality. Liang et al. [57] discovered a significant positive correlation among the Zn content, Zn/Cu ratio, and glycyrrhizic acid level in G. uralensis roots.

In summary, research has primarily focused on the components of G. uralensis and G. glabra, followed by G. inflata. All three licorice species contain triterpenoids, flavonoids, polysaccharides, and alkaloids. However, the chemical composition varies among different varieties. Significant differences in the content of flavonoids and triterpenoids are found among different varieties, but confirming which variety of licorice has a high content is difficult due to the influence of sample variations and experimental design differences. The proportions of monosaccharide compositions in polysaccharides also vary among different varieties. Coumarin-type components are prevalent in G. uralensis. Different licorice varieties have components that are unique to their species. Research has reported 27 biomarkers that can be used to differentiate G. uralensis, G. inflata, and G. glabra [58]. The biomarkers for G. uralensis are licoflavonol, isolicoflavonol, glycyrol, glycycoumarin, glycyuralin E, glyasperin D, licoricone, glicoricone, isoangustone A, 7-O-methylluteone, 6,8-diprenylgenistein, and glicophenone. The biomarkers for G. glabra are glabridin, hispaglabridin B, 4ʹ-O-methylglabridin, 3ʹ-hydroxy-4ʹ-O-methylglabridin, hispaglabridin A, parvisoflavones-A, glycybridin C, erybacin B, and 3-hydroxy-glabrol. The biomarkers for G. inflata are licochalcone A, licochalcone C, 3-OH licochalcone A, licochalcone E, licoagrochalcone C, and 3,4-didehydroglabridin. These biomarkers can provide a basis for the identification and quality control of different licorice varieties.

Pharmacological activities of active components in plants of the Glycyrrhiza genus

Antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory

Modern pharmacological studies suggested that the flavonoids and triterpenoids in licorice may be the main active components responsible for its antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory effects. This type of research could have implications for the development of new drugs targeting drug-resistant bacteria and the study of preservatives with high salt and protease contents as antimicrobial agents in food. However, the safety and efficacy of these compounds still require further investigation. G. uralensis has demonstrated good inhibitory effects against Gram-positive bacteria such as Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus, and Enterococcus [59]. Licochalcone A extract from G. inflate could inhibit the growth of Bacillus subtilis in a concentration-dependent manner [60]. It can also effectively improve the clinical symptoms of acetic acid-induced ulcerative colitis in mice by exerting its antioxidant effects through the inhibition of the nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB) signaling pathway and the promotion of the nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) signaling pathway [61]. Glabridin from G. glabra hinders biofilm formation in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus by modulating cell surface proteins and reducing the abundance of surface-associated adhesins [62]. It can also effectively and dose-dependently inhibit the production of inflammatory mediators leukotrienes and thromboxanes in HL-60 cells, a type of acute promyelocytic leukemic cells [63]. Glabridin inhibits dendritic cell maturation by reducing pro-inflammatory cytokines, enhancing antigen capture, inhibiting migration, and impairing T cell activation, through blocking NF-κB and MAPK signaling pathways [64]. Glycyrrhizic acid has demonstrated potential against various bacterial and viral pathogens, positioning it as a candidate for alternative therapeutic applications. This compound significantly inhibits the growth of Pseudomonas aeruginosa by altering membrane permeability, efflux activity, and biofilm formation [65]. Meanwhile, glycyrrhizic acid has anti-inflammatory and immunoregulatory effects. It inhibits inflammation and apoptosis induced by Mycoplasma gallisepticum in chickens by suppressing the MAPK signaling pathway, indicating its potential as an antibiotic alternative [66]. Glycyrrhizic acid exerts anti-asthmatic effects by modulating Th1/Th2 cytokines and enhancing regulatory T cells (Tregs) in an ovalbumin-sensitized mouse model [67]. Glycyrrhizic acid exhibits remarkable antimicrobial activities against a diverse array of bacterial. Its mechanisms encompass inhibiting bacterial growth and biofilm formation, and modulating immune responses. These discoveries imply that glycyrrhizic acid might serve as a precious alternative to conventional antibiotics drugs, possessing potential applications in the treatment of infections and inflammatory conditions.

Antiviral

Since the 1980 s when Japanese researchers first reported the anti-HIV effects of glycyrrhizic acid, significant research has been conducted on the antiviral properties of licorice. The studies involved various active compounds, such as flavonoids, triterpenoids, coumarins, and polysaccharides, and explored licorice’s potential to combat various viruses, including HIV, atypical pneumonia viruses, hepatitis viruses, human respiratory syncytial virus, and influenza viruses. Adianti et al. [68] discovered that methanol extracts from G. uralensis roots and its chloroform fraction exhibited antiviral activity against hepatitis C virus. Wang et al. [69] found that the antiviral activity of G. uralensis is related to the glycyrrhizic acid content of its extracts. Glycyrrhizic acid also dose-dependently blocks the replication of enterovirus 71 and coxsackievirus A16. Soufy et al. [70] isolated glycyrrhizic acid from G. glabra roots through in vitro and in vivo experiments; when used alone or in combination with duck hepatitis vaccine, glycyrrhizic acid exhibited strong immune stimulation and antiviral effects against duck hepatitis virus infection. Glycyrrhizic acid exerts a direct antiviral effect on HBV by inhibiting the secretion of hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) and improving liver function in patients with chronic hepatitis B, ultimately enhancing immune status [71]. Additionally, glycyrrhizic acid and its derivatives exhibit antiviral activity against a wide range of viruses, including herpes virus [72], SARS-CoV-2 [73], COVID-19 [74], [75], and Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) [76]. Glycyrrhizic acid demonstrates significant antiviral properties against a variety of viruses through mechanisms such as inhibition of viral entry and replication. The development of glycyrrhizic acid derivatives further enhances its antiviral efficacy, making it a promising candidate for alternative antiviral therapies.

Antioxidant

Licorice has antioxidant activity, which may be related to the content, concentration, extraction temperature, and extraction methods of its triterpenoids, polysaccharides and flavonoids [77]. Researchers evaluated the antioxidant activity of licorice using methods such as measuring the hydrogen peroxide system and scavenging 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) radicals and superoxide anion radicals. Xu et al. found that glycyrrhizic acid can activate the expression of myocardial nuclear factor E2-related factor 2/heme oxygenase-1 (Nrf2/HO-1) and inhibit the nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) signaling pathway, thereby improving myocardial ischemic injury and preventing myocardial infarction [78]. Chen et al. [79] obtained a polysaccharide component, glycyrrhiza polysaccharide II, from G. uralensis roots; it showed excellent concentration-dependent hydroxyl radical scavenging activity and significant DPPH radical scavenging ability. G. glabra polysaccharides (GGP) treatment can enhance immune activities and reduce oxidative stress in high-fat mice [80]. Glabridin is an isoflavone obtained from G. glabra root, and in vitro and in vivo experiments have shown that it possesses excellent antioxidant properties [81]. Ojha et al. [82] found that G. glabra extract exhibited protective effects against ischemia–reperfusion injury induced by left anterior descending coronary artery ligation in rats by alleviating oxidative stress and favorably regulating the cardiac function. Cong et al. [83] extracted and found that the polysaccharides in G. inflate have certain scavenging effects on DPPH radicals, hydroxyl radicals, and superoxide anion radicals. Pan et al. [84] identified a polysaccharide called GIBP from G. inflate that has antioxidant and antiaging effects. In vitro experiments confirmed its strong scavenging activity against hydroxyl radicals. Liquiritin can reduce the content of acetaldehyde in the human body, increase the levels of superoxide dismutase and glutathione peroxidase, alleviate aging, and enhance antioxidant capacity [85]. Glycyrrhiza, through its difference extracts, exhibits significant antioxidant properties by enhancing antioxidant enzyme activities, reducing oxidative stress markers, and providing hepatoprotective effects.

Antineoplastic

The flavonoid components of licorice have demonstrated strong anti-tumor activity against various human cancer cells, including cervical cancer, breast cancer, prostate cancer, and liver cancer cells. They effectively inhibit proliferation and induce apoptosis in these cancer cells. Wei et al. [86] discovered that by downregulating the expression levels of cell cycle proteins D1, cell cycle proteins A, and cell cycle proteins cyclin-dependent kinase 4, liquiritin promotes the expression of p53 and p21 genes and inhibit the proliferation and migration of gastric cancer cells, thus inducing apoptosis and autophagy in cancer cells. Ma et al. [87] discovered that licorice flavonoids have a significant inhibitory and apoptotic effect on cervical cancer HeLa cells, breast cancer Bcap-37 cells, gastric cancer MGC-803 cells, and liver cancer Bel-7404 cells. Park et al. [88] evaluated the hexane–ethanol extract of G. uralensis and found that it significantly inhibits the metastasis and invasion capabilities of malignant prostate cancer cells. Various flavonoids in G. inflate can inhibit cell growth and induce apoptosis. The crude and refined extracts of G. inflate can effectively inhibit the proliferation of cervical cancer cells SiHa and HeLa, thus promoting their apoptosis [89]. Licochalcone A from G. inflate can downregulate the expression of specificity protein 1 and regulate downstream proteins to induce apoptosis in human oral squamous cell carcinoma cells HSC4 and HN22, thereby inhibiting the growth of oral squamous cell carcinoma cells in a concentration- and time-dependent manner [90]. Glycyrrhizic acid and glycyrrhiza polysaccharides also have antitumor effects. Glycyrrhetinic acid exhibit anti-cancer effects by modulating enzymes involved in inflammation and oxidative stress, and downregulating pro-inflammatory mediators, which can suppress tumor cell growth. Cai et al. [91] studied the effects of glycyrrhizic acid on liver cancer cells using proteomics and chemical biology and found that glycyrrhizic acid can inhibit the activity and induce apoptosis in liver cancer stem cells. Glycyrrhetinic acid enhances triple-negative breast cancer treatment by sensitizing cells to etoposide, promoting apoptosis, while glycyrrhizic acid offers protection [92]. Meanwhile, Glycyrrhetinic acid is also therapeutically effective against cervical cancer cells [93]. Additionally, the antitumor mechanism of glycyrrhiza polysaccharides was investigated using a colon cancer CT-26 cell-bearing mouse model based on the gut microbiota [94].

Lowering blood sugar, regulating blood lipids, and antiatherosclerosis

Flavonoids in licorice have demonstrated good hypoglycemic, blood lipid-regulating, and antiatherosclerotic effects and exhibit more effective hypoglycemic activity than positive control drugs. Gou et al. [95] isolated seven flavonoids from G. uralensis roots, all of which exhibited more effective α-glucosidase inhibitory activity than the positive control drug, acarbose. Kent et al. [96] found that glabridin, a compound in G. glabra, inhibits cytochrome P4503A4. This action is believed to contribute to its protective effect against low-density lipoprotein oxidation and its subsequent antiatherosclerotic properties. Carmelli et al. [97] administered glabridin from G. glabra and found a 20 % reduction in plasma low-density lipoprotein oxidation in 22 healthy volunteers within 6 months.

Other pharmacological activities

In addition to the mentioned pharmacological effects, licorice also possesses pharmacological activities such as cardioprotective activity [98], antidepressive activity [99], [100], and neuroprotective activity [101]. Rashedinia et al. [102] found that glycyrrhizic acid can protect cells by promoting mitochondrial biogenesis, maintaining mitochondrial function, and enhancing energy metabolism. Han et al. [103] discovered that glycyrrhizic acid can also exert antiallergic effects by regulating immune cells or immunoglobulins associated with allergies. Zhang et al. [104] reported that liquiritin can inhibit the expression of collagen and alpha-smooth muscle actin, thereby playing a cardioprotective role by suppressing the development of myocardial fibrosis induced by high fructose. Wang et al. [105] demonstrated the antidepressant activity of liquiritin and isoliquiritoside through forced swimming and tail suspension tests. Glycyrrhiza polysaccharides can promote the proliferation of human peripheral blood γδ T cells and dose-dependently increase the secretion of interferon-γ and TNF-α [106]. Ayeka et al. [107] demonstrated the immunomodulatory effects of glycyrrhiza polysaccharides by measuring immune organ quality and indices, immune cell numbers, and serum cytokine levels after administration. Other studies reported the hepatoprotective and neuroprotective effects of G. uralensis [108]; neuroprotective effects, tyrosinase inhibition, and estrogen-like effects of G. glabra [109], [110]; and antiangiogenic effects of G. inflata [111] (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Active ingredients and pharmacology of licorice. a. The main active ingredients in licorice and their pharmacological effects. b. Other typical triterpenoids in licorice. c. Other typical flavonoids in licorice.

Transcriptomic and genomic study of licorice

Genomics and transcriptomics serve as valuable tools in understanding species evolution and genetic diversity and in deciphering the biosynthesis of bioactive compounds in medicinal plants. Before the genome sequencing of Glycyrrhiza species, the transcriptomes of various tissues and their treatments were extensively used to identify the genes related to the biosynthesis of triterpenoids and flavonoids and those associated with plant development. A total of 814 transcriptome datasets are currently available for various Glycyrrhiza species in NCBI’s SRA database. The majority of these datasets pertain to medicinal species. Among them, G. uralensis has the highest number of datasets with 402, followed by G. inflata with 48 datasets and G. glabra with 15 datasets. These datasets provide insights into gene expression and transcription patterns in the roots, stems, and leaves and gene expression profiles under various treatments or conditions. They offer significant support for further research and analysis on these species, helping deepen our understanding of their molecular biology, responses to different treatments, and potential applications.

With the rapid development of sequencing technologies, the application of molecular genetics to nonmodel species for genomic research has become possible. In this context, we summarize the genomic research on Glycyrrhiza species. Among Glycyrrhiza plants, only G. uralensis has had its genome published, with two versions currently available (Table 1). Mochida et al. [112] first sequenced and assembled the whole genome of G. uralensis, creating a reference genome. Initially, high-quality genomic DNA was extracted from G. uralensis for genome sequencing. Illumina sequencing platform was used to generate 380.53 Gb of raw data from three different insert sizes (190 bp, 3 kb, and 10 kb) of sequencing libraries. After short and low-quality reads were filtered out, 327.53 Gb of high-quality sequences were obtained. Flow cytometry analysis estimated the genome size to be 400.95 Mb (±4 Mb), with a sequencing depth of 817 × . However, second-generation sequencing is constrained in assembling short reads into long sequences. Therefore, a third-generation sequencing technology, PacBio RS II, was further employed to obtain 6.76 Gb of data with a sequencing depth of 16.86 × . The low-quality PacBio data were corrected using high-quality Illumina data, resulting in 4.52 Gb of error-corrected long sequences. Compared with the estimated genome size, the dataset had a coverage depth of 11.27 × . Finally, the assembly results from the three sequencing approaches were combined, yielding a G. uralensis genome sequence of 379 Mb that accounted for approximately 94.5 % of the initially estimated genome size. A total of 34,445 protein-coding genes were predicted. Comparative analysis revealed that the G. uralensis genome exhibited conservation in genome composition and gene loci with other Fabaceae plants such as Medicago truncatula and Cicer arietinum. Three genes involved in isoflavones biosynthesis (CYP93C, HI4OMT, and 7-IOMT) were identified with the G. uralensis genome and formed gene clusters. On the basis of genome annotation, several genes involved in triterpenoid saponin biosynthesis were predicted within the cytochrome P450 (CYP450) and UDP-glucuronosyltransferase (UGT) superfamilies, and their gene expression was characterized using the reference genome sequence.

Table 1.

Comparison of the two versions of G. uralensis genome.

| Rai et al [113] | Mochida et al [112] | |

|---|---|---|

| Number of contigs | 54 | 72,148 |

| Total length (contigs) | 459.19 Mb | — |

| N50 (contigs) | 36.03 Mb | 7.32 kb |

| Number of scaffolds | 89 | 12,528 |

| Total length (scaffolds) | 459.21 Mb | 378.86 Mb |

| N50 (scaffolds) | 60.2 Mb | 109.27 kb |

| GC content (scaffolds) | 37.78 % | 35.34 % |

| Number of chromosomes | 8 | — |

| Total length (chromosomes) | 429.07 Mb | — |

| N50 (chromosomes) | 58.56 Mb | — |

| GC content (chromosomes) | 37.13 % | — |

| Anchored | 93.44 % | — |

| Unplaced scaffolds | 81 | — |

| Total gene number | 32,941 | 34,445 |

| Number of chromosome genes | 32,454 | — |

| BUSCO completeness (chromosomes) | 98.6 % | — |

| BUSCO completeness (annotation) | 96.5 % | — |

Obtaining a high-quality genome assembly is crucial to explore the evolutionary basis for defining chemical-type specific traits and provide essential resources for molecular breeding strategies for enhancing the production of medicinal metabolites. To achieve a high-quality G. uralensis genome, Rai et al. [113] utilized single-molecule high-fidelity (HiFi) sequencing and reported a chromosome-level genome for G. uralensis. Their analysis of heterozygosity using HiFi reads revealed a heterozygosity rate of 1.65 %, estimating a genome size of 391.9 Mb. A total of 15.43 Gb of raw PacBio HiFi reads were obtained, equivalent to approximately 38.9 times the estimated genome size. The final assembled genome consisted of 54 contigs with a total size of approximately 459 Mb and an N50 of 36.02 Mb. After scaffolding, 89 scaffolds with an N50 of 60.2 Mb were acquired, and 93.44 % of these scaffolds were anchored to eight chromosomes, totaling approximately 429 Mb. A total of 32,941 genes were annotated, with 32,454 genes located on the eight chromosomes. Whole-genome duplication (WGD) analysis showed that G. uralensis experienced a gamma (γ) WGD event approximately 59.13 million years ago (MYA), followed by a shared WGD event with other Papilionoideae species around 58 MYA. No additional WGD events were observed in the G. uralensis genome. Furthermore, metabolic gene cluster analysis identified 355 gene clusters, including the entire biosynthetic pathway of glycyrrhizic acid.

Biosynthesis and transcriptional regulation of flavonoids and triterpenoids in licorice

Biosynthesis of glycyrrhizic acid

The biosynthesis pathway of glycyrrhizinic acid mainly relies on the mevalonate (MVA) pathway, which catalyzes the direct production of the precursors of glycyrrhizinic acid, isopentenyl pyrophosphate (IPP) and its isomer dimethylallyl pyrophosphate (DMAPP) [114]. In the MVA pathway, 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase (HMGR) is a key rate-limiting enzyme that catalyzes the irreversible conversion of HMG-CoA into MVA. It is also a key rate-limiting enzyme in the synthesis of glycyrrhizic acid and terpenes, and its expression is significantly positively correlated with the production of glycyrrhizic acid [114]. According to research, the expression level of HMGR in the hairy roots of G. uralensis is significantly positively correlated with the content of glycyrrhizic acid [115].

The catalytic synthesis of glycyrrhizic acid from the precursor IPP involves several key enzymes. In the first stage, IPP is catalyzed sequentially by geranyl diphosphate synthase (GPS), farnesyl diphosphate synthase (FPS), squalene synthase (SQS), and squalene epoxidase (SQE) to produce 2,3-oxidosqualene (2,3-OSC) [114]. 2,3-oxidosqualene is a precursor of triterpenoids and sterols, and its conversion into these compounds is mediated by various oxidosqualene cyclases (OSCs). β-amyrin synthase (β-AS) catalyzes the cyclization of 2,3-oxidosqualene to produce β-amyrin. The expression of β-AS is only observed in the underground parts, which corresponds to the accumulation of glycyrrhizic acid in the roots [114]. CYP450 are key enzymes in the second stage of glycyrrhizic acid biosynthesis. CYP88D6 is a CYP450 monooxygenase that catalyzes a consecutive two-step oxidation at the C-11 position of β-amyrin, leading to the formation of 11-oxo-β-amyrin [116]. The expression pattern of CYP88D6 is consistent with the β-AS gene, as it is exclusively expressed in the underground parts of the plant [116]. G. uralensis has a homologous gene to CYP88D6, known as Uni25647, which shares 97 % amino acid similarity with CYP88D6 and exhibits higher C-11 oxidation enzyme activity than CYP88D6 [117]. Another crucial CYP450 monooxygenase in this pathway is CYP72A154, which is responsible for three consecutive oxidations at the C-30 position of 11-oxo-β-amyrin. This enzymatic process catalyzes the production of glycyrrhizin from 11-oxo-β-amyrin [118]. Cytochrome P450 reductases (CPR) are essential enzymes in the oxidations catalyzed by CYP450 monooxygenases. In the biosynthesis pathway of glycyrrhizic acid, GuCPR1 is also involved in the oxidations at the C-11 and C-30 positions of β-amyrin [117]. Within a yeast synthetic system, GuCPR1 significantly enhances the synthesis efficiency of glycyrrhetinic acid [117].

Glycosylation modification is the final stage in the biosynthesis pathway of glycyrrhizic acid and is catalyzed by UGTs, which add a glucuronosyl group to the C-3 position of glycyrrhetinic acid. GuUGAT (also known as GuUGT3) catalyzes the glucuronosylation of glycyrrhetinic acid, directly producing glycyrrhizic acid through two consecutive glucuronosylation steps [119]. Experiments on amino acid residue mutation for GuUGAT suggested that Gln-352 plays a crucial role in the initial step of glucuronosylation, and His-22, Trp-370, Glu-375, and Gln-392 are essential in the subsequent step of glucuronosylation [119]. Expression profile analysis indicated that GuUGAT is expressed in the roots, stems, and leaves, with the highest expression found in the roots. Salt and drought stress significantly induce the expression of this gene [119].

Along with members of the cellulose synthase superfamily GuCSyGT and GuCsl, O-glycosyltransferase GuGT14 also exhibits triterpenoid glycosyltransferase activity, catalyzing the formation of 3-O-monoglucuronosyl glycyrrhetinic acid from glycyrrhetinic acid [120], [121], [122]. GuUGT73P12 is responsible for catalyzing the second step of glucuronic acid conjugation in the glycyrrhizic acid biosynthesis pathway, thereby converting 3-O-monoglucuronosyl glycyrrhetinic acid into glycyrrhizic acid [7] (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Synthesis pathways of glycyrrhizic acid. AACT: Acetyl-CoA C-acetyltransferase, HMGS: Hydroxymethylglutaryl-CoA synthase, HMGR: 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase, MK: Mevalonate kinase, MPK: Mevalonate phosphate kinase, MPD: Mevalonate pyrophosphate decarboxylase, GPS: Geranylgeranyl diphosphate synthase, FPS: Farnesyl pyrophosphate synthase, SQS: Squalene synthase, SQE: Squalene epoxidase, β-AS: β-amyrin synthase.

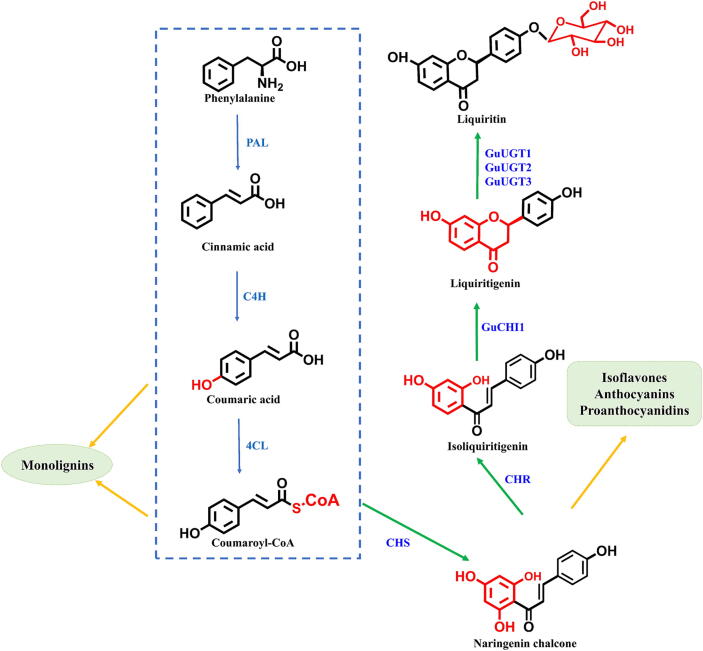

Biosynthesis of liquiritin

The biosynthesis pathway of liquiritin has been successfully elucidated (Fig. 3). Phenylalanine serves as the precursor for liquiritin. The initial three steps of its biosynthesis pathway are identical to those of other flavonoid compounds, collectively known as the common phenylalanine pathway [123]. Sequentially catalyzed by phenylalanine ammonia lyase (PAL), cinnamate 4-hydroxylase (C4H), and 4-coumarate-CoA ligase (4CL), phenylalanine is converted into coumaroyl-CoA. Chalcone synthase (CHS) transforms coumaroyl-CoA into naringenin chalcone, which represents a rate-limiting step in the flavonoid biosynthesis pathway. Chalcone reductase (CHR) then catalyzes the conversion of naringenin chalcone into isoliquiritigenin [123], [124]. Isoliquiritigenin undergoes further catalysis by type II chalcone isomerase GuCHI1 to produce liquiritigenin, which is then subjected to 4ʹ-O-glycosylation modification by GuUGT1, GuUGT2, and GuUGT3 in the final step of liquiritin biosynthesis, resulting in the formation of the end product liquiritin [125].

Fig. 3.

Synthesis pathways of liquiritin. PAL: Phenylalanine ammonla lyase, C4H: Cinnamate 4-hydroxylase, 4CL: 4-coumarate-CoA ligase, CHS: Chalcone synthase, CHR: Chalcone reductase, CHI: Chalcone isomerase.

Transcriptional regulation of triterpenoid and flavonoid biosynthesis in licorice

Transcription factors (TFs) are a class of proteins with unique molecular structures, typically encompassing functional domains such as a DNA-binding domain, transcriptional regulatory domains, oligomerization sites, and nuclear localization signals. These functional domains determine the characteristics and functions of TFs [126]. In plants, TFs recognize and bind to cis-acting elements within the gene promoter regions when stimulated by external factors or during plant growth. This interaction enables them to initiate and regulate gene expression, thereby facilitating the production of gene products [127] (Fig. 4). TFs can also activate or inhibit gene transcription through their interactions with each other and with other related proteins [128], [129]. According to their distinct structure and function, various types of TFs have been categorized in medicinal plant research. Some notable families being studied include MYB, bHLH, WRKY, and bZIP.

Fig. 4.

Transcription factors (TFs) regulating the biosynthesis of triterpenoids and flavonoids in licorice by transmitting signals under abiotic and biotic factors. When licorice is stimulated by external factors, stress signals are transmitted to TFs through signal transmission pathways, such as Ca2+, ROS, and systemic signalling. Then, TFs recognize and bind to cis-acting elements within the gene promoter regions, which enables TFs to initiate and regulate gene expression, thereby facilitating the production of gene products. Some TFs and genes involved in these transcriptional regulation processes have not yet been identified.

The secondary metabolites of plants are the result of the interaction between plants and biotic or abiotic factors during long-term evolution, exhibiting a diverse range of intricate biological functions [130]. The biosynthesis pathway of secondary metabolites in plants is complex and involves multiple enzymes catalysis. However, TFs can activate the coexpression of the multiple synthase genes of secondary metabolites, thereby effectively regulating the secondary metabolic pathway. Hence, the comprehensive analysis of key enzyme genes involved in plant secondary metabolite synthesis and the identification of TFs that regulate their expression have become a prominent research focus in this field.

The plant kingdom harbors a plethora of secondary metabolites with diverse structures; among which, triterpenoids and flavonoids are the predominant constituents in licorice. In this context, we elucidated the current advancements in understanding various types of TFs that govern the biosynthesis of these two classes of secondary metabolites.

Several TFs have been identified in licorice based on genomics and transcriptomics. Li et al. [131] added methyl jasmonate (MeJA) to G. uralensis cell suspension and identified differentially expressed genes through RNA-seq analysis. The results showed that the MYB TFs GuMYB4 and GuMYB88 were significantly responsive to MeJA induction. Subsequent investigation revealed the nuclear localization of GuMYB4 and GuMYB88 proteins, confirming their positive regulatory role in flavonoid synthesis in G. uralensis cells. Tamura et al. [132] identified a licorice bHLH TF called GubHLH3. Its overexpression in transgenic licorice hairy roots resulted in the increased expression of soyasaponin biosynthetic genes β-AS, CYP93E3, and CYP72A566, leading to the elevated levels of soyasapogenol B and sophoradiol. This finding suggested that GubHLH3 can positively regulate the expression of soyasaponin biosynthetic genes. Furthermore, the soyasaponin biosynthetic genes and GubHLH3 were coexpressed in response to MeJA induction. In a transcriptome analysis conducted by Goyal et al. [133], 147 full-length genes encoding WRKY TFs were identified in G. glabra. They performed a comparative structural analysis of these WRKY genes and identified 23 abiotic stress-responsive GgWRKYs and 17 hormone signal-induced GgWRKYs. In our previous work, 69 members of the bZIP TF gene family were identified in G. uralensis based on the whole-genome data [134]. From these genes, five candidates were upregulated in response to ABA stress. Overexpression and RNAi vectors were then constructed for these candidate genes and successfully performed the genetic transformation of G. uralensis hairy roots. The findings demonstrated a positive correlation between the expression levels of certain genes involved in the biosynthesis of active licorice compounds (such as CHI, CHS, HMGS, SQS, UGT, and β-AS) and the expression levels of the candidate GubZIP genes (GubZIP5, GubZIP33, and GubZIP56) in the overexpression lines and their corresponding RNAi counterparts. Furthermore, the overall change trends of the contents of total flavonoids, total triterpenoids, liquiritin, liquiritigenin, and isoliquiritigenin in the transgenic hairy roots were positively correlated with the expression levels of the candidate GubZIP genes.

Currently, the research on the transcriptional regulation of licorice is limited. Although the enzymes involved in the biosynthesis of triterpenoids and flavonoids in licorice have been studied, the regulatory factors associated with species phenotype formation, development, and bioactive compound synthesis remain unknown. Research on the transcriptional regulation of licorice primarily focuses on the functional validation of TFs and their responses to abiotic stress. Some studies have only examined the effects of biotic or abiotic factors on the content of active compounds, without identifying the specific TFs involved or which genes they regulate (Fig. 4) [135], [136], [137], [138], [139], [140].

In addition to licorice, the TFs regulating terpene and flavonoid biosynthesis in numerous other plants have been identified and extensively studied (Table 2). These studies have a positive impact on guiding the study of transcriptional regulation in licorice. Yu et al. [141] isolated two AP2 TFs, AaERF1 and AaERF2, from Artemisia annua by yeast one-hybrid and confirmed by electrophoretic mobility shift assay that they could bind CBF2 and RAA elements in ADS and CYP71AV1 promoter regions, respectively, which are the key enzymes in artemisinin synthesis pathway. The transient expression of AaERF1 and AaERF2 in Nicotiana tabacum can increase the transcription level of ADS and CYP71AV1 and the production of artemisinin and artemisinin acid. Conversely, the inhibition of AaERF1 and AaERF2 expression by RNAi technology resulted in a decrease in artemisinin and artemisinin acid contents. These findings indicated that AaERF1 and AaERF2 can positively regulate artemisinin synthesis. Zhang et al. [142] first identified six members from 64 highly expressed bZIP TFs in the glandular trichomes of A. annua. Along with ADS and CYP71AVI genes, these six TFs were then introduced into N. tabacum leaves through transformation. Dual-luciferase assay results predicted that AabZIP1 could activate the promoters of these two key enzyme genes. Furthermore, yeast one-hybrid experiments demonstrated that AabZIP1 could directly bind to the ABRE promoter element of ADS and CYP71AV1, thereby activating their expression. The overexpression vector AabZIP1 was then constructed and transformed into A. annua, which significantly increased the content of artemisinin, indicating that the TF AabZIP1 positively regulates artemisinin synthesis. The mechanism of ABA-mediated artemisinin biosynthesis was also elucidated through experiments. The results showed that ABA enhanced the transcriptional activity of AabZIP1 towards the promoters of ADS and CYP71AV1 genes. Moreover, the ABA receptor protein AaPYL9 was isolated from A. annua plants with overexpressed AabZIP1 gene and significantly increased the artemisinin content, suggesting that AabZIP1 plays a key role in ABA-induced artemisinin synthesis. The TFs involved in ABA signal transduction pathway have also been studied in G. uralensis[143], [144], [145], [146]. WRKY (AaWRKY1) [147], [148], bHLH (AabHLH1) [149], NAC (AaNAC1) [150] and MYB (AaMYB1) [151] TFs also regulate artemisinin synthesis. The regulation of terpenoid synthesis by TFs has also been studied in other medicinal plants. The MYB36 and MYB9b of Salvia miltiorrhiza were involved in the regulation of tanshinone synthesis [152], [153]. JAZ is an inhibitor of jasmonic acid signal transduction, and the overexpression of SMJAZ1/2/3/9 significantly promoted the accumulation of tanshinone in the fibrous roots of S. miltiorrhiza [154], [155]. In the glandular trichomes of Mentha spicata, MsMYB directly binds to the cis-acting elements of the large subunit of GPP synthase (MsGPPS.LSU), inhibits gene expression, and negatively regulates terpenoid synthesis [156].

Table 2.

Identified transcription factors involved in the terpenoid and flavonoid biosynthesis of plants.

| Type of compositions | Type of TFs | Transcription factors |

Species | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Terpenoids | AP2/ERF | AaORA | Artemisia annua | [168] |

| TAR1 | Artemisia annua | [169] | ||

| TcAP2 | Taxus cuspidata | [170] | ||

| bHLH | AabHLH1 | Artemisia annua | [171] | |

| AabHLH112 | Artemisia annua | [172] | ||

| AaMYC2 | Artemisia annua | [173] | ||

| GubHLH3 | Glycyrrhiza uralensis | [132] | ||

| GubHLHs | Glycyrrhiza uralensis | [174] | ||

| TcJAMYC | Taxus cuspidata | [175] | ||

| SmMYC2a | Salvia miltiorrhiza | [176] | ||

| SmbHLH10 | Salvia miltiorrhiza | [177] | ||

| SmbHLH148 | Salvia miltiorrhiza | [178] | ||

| SmbHLH3 | Salvia miltiorrhiza | [179] | ||

| BpbHLH9 | Betula platyphylla | [180] | ||

| TSAR1 | Medicago truncatula | [181] | ||

| TSAR2 | Medicago truncatula | [181] | ||

| bZIP | AabZIP1 | Artemisia annua | [142] | |

| AabZIP9 | Artemisia annua | [182] | ||

| GubZIP5 | Glycyrrhiza uralensis | [134] | ||

| GubZIP33 | Glycyrrhiza uralensis | [134] | ||

| GubZIP56 | Glycyrrhiza uralensis | [134] | ||

| EIN3 | AaEIN3 | Artemisia annua | [183] | |

| MYB | GuMYBs | Glycyrrhiza uralensis | [174], [184] | |

| GmMYBZ2 | Glycine max | [185] | ||

| PatSWC4 | Pogostemon cablin | [186] | ||

| SmMYB4 | Salvia miltiorrhiza | [187] | ||

| SmMYB36 | Salvia miltiorrhiza | [152] | ||

| SmMYB52 | Salvia miltiorrhiza | [188] | ||

| SmMYB98 | Salvia miltiorrhiza | [189] | ||

| SmMYB111 | Salvia miltiorrhiza | [190] | ||

| TH | PatGT-1 | Pogostemon cablin | [191] | |

| WRKY | AaWRKY1 | Artemisia annua | [147], [148] | |

| AaWRKY9 | Artemisia annua | [192] | ||

| AaGSW1 | Artemisia annua | [193] | ||

| AaGSW2 | Artemisia annua | [194] | ||

| YABBY | AaYABBY5 | Artemisia annua | [195] | |

| MsYABBY5 | Mentha spicata | [196] | ||

| Flavonoids | AP2/ERF | CitERF32 | Citrus reticulata cv. Suavissima | [197] |

| CitERF33 | Citrus reticulata cv. Suavissima | [197] | ||

| bHLH | GubHLHs | Glycyrrhiza uralensis | [174] | |

| GibHLH7 | Glycyrrhiza inflata | [198] | ||

| AmPerilla | Antirrhinum majus | [199] | ||

| AmDelila | Antirrhinum majus | [200] | ||

| AmbHLH-1 | Antirrhinum majus | [201] | ||

| AmbHLH-2 | Antirrhinum majus | [201] | ||

| GtbHLH1 | Gentiana triflora | [202] | ||

| LmbHLH113 | Lonicera macranthoides | [203] | ||

| bZIP | GubZIP5 | Glycyrrhiza uralensis | [134] | |

| GubZIP33 | Glycyrrhiza uralensis | [134] | ||

| GubZIP56 | Glycyrrhiza uralensis | [134] | ||

| MYB | GlMYB4 | Glycyrrhiza uralensis | [131] | |

| GlMYB88 | Glycyrrhiza uralensis | [131] | ||

| GlMYB84 | Glycyrrhiza uralensis | [174] | ||

| GuMYBs | Glycyrrhiza uralensis | [174] | ||

| LmMYB12 | Lonicera macranthoides | [203] | ||

| LmMYB75 | Lonicera macranthoides | [203] | ||

| SmMYB39 | Salvia miltiorrhiza | [204] | ||

| AmRosea1 | Antirrhinum majus | [200], [205] | ||

| AmRosea2 | Antirrhinum majus | [205] | ||

| GtMYB3 | Gentiana triflora | [202] | ||

| DwMYB9 | Dendrobium hybrid Woo Leng | [206] | ||

| InMYB1 | Ipomoea nil | [207] | ||

| GhMYB1 | Gerbera hybrida | [208] | ||

| WDR | InWDR1 | Ipomoea nil | [207] |

The TFs regulating flavonoid synthesis have been extensively investigated across various plant species. In Epimedium sagittatum, EsMYBF1 can activate the promoters of EsF3H and EsFLS genes. Its overexpression in N. tabacum resulted in a significant upregulation of the key genes involved in flavonol biosynthesis including CHS, CHI, F3H, F3′H, and FLS, leading to a substantial increase in flavonol content [157].

Similarly, CsMYBF1 was found to bind and activate Cs4CL, CsCHS and CsFLS promoters in Citrus reticulata. Its inhibition using RNAi technology in C. reticulata significantly reduced flavonol content [158]. However, Xu et al. [159] observed that the overexpression of GbMYBF2 from Ginkgo biloba in Arabidopsis thaliana led to a notable reduction in transcription levels of CHS, F3H, FLS, and ANS genes and the inhibition of anthocyanin and other flavonoid synthesis. This finding suggested that GbMYBF2 plays a negative regulatory role. The GtMYBP3 and GtMYBP4 of Gentiana triflora can activate the expression of genes related to flavonol synthesis, and their overexpression in A. thaliana can significantly increase the flavonol content in seedlings [160]. The color of Rubus idaeus fruit could be red, gold, or black. Anthocyanin, a secondary metabolite of flavonoids, serves as an important factor influencing fruit coloration. bZIP TFs can affect anthocyanin synthesis in red R. idaeus [161]. After the mutation of MTWD40-1 gene in Medicago truncatula, a decrease in isoflavone synthesis within roots was observed, suggesting the potential involvement of MTWD40-1 TF in plant flavonoid biosynthesis [162].

A variety of TFs coregulate the synthesis of metabolic components. Certain plant species have a complex structure known as the MBW complex, which is composed of MYB, bHLH, and WD403 proteins. This complex participates in the regulation of flavonoid biosynthesis. For instance, the MBW complex TT2/TT8/TTG1 in A. thaliana regulates the synthesis of proanthocyanidins in the seed coat [163], [164], [165]. In the leaves of Petunia hybrida, AN1 (bHLH) and AN2 (MYB) proteins coregulate the synthesis of pigments. In anthers, AN1 relies on AN4 (MYB) to activate the structural gene DFR of anthocyanin synthesis pathway [166]. In their study on the regulation of anthocyanin synthesis in Myrica rubra fruits, Liu et al. [167] found that MrbHLH1 could form a transcription complex with MrMYB1 and promote anthocyanin accumulation by selectively activating structural genes.

Synthetic biology of glycyrrhizic acid and liquiritin

Licorice has medicinal value and dietary importance. However, it has low concentrations of specific active ingredients, such as glycyrrhizic acid and liquiritin. The extraction of these natural active components from plants cannot meet the increasing demand. Microbial metabolic engineering has been developed and applied to efficiently produce plant-specific active ingredients. Various strategies have been developed and introduced for the biosynthesis of licorice triterpenoids and flavonoids. One approach is genetic manipulation and fermentation engineering with the use of microbial cell factories for in vitro synthesis.

Fine-tuning the expression ratio of CYP450 enzymes and CPR can optimize the catalytic activity of CYP88D6 oxidation–reduction system. This optimization enables the efficient production of 11-oxo-β-amyrin, the direct precursor of glycyrrhetinic acid, in brewing yeast [209]. Initially, CRISPR-Cas9 technology was employed to knock out the ERG27 and BTS1 genes in brewing yeast, increasing the yield of squalene by 6.91 times. A precursor β-amyrin synthesis pathway was then constructed in this engineered strain, and metabolic engineering strategies were employed to optimize the yield. Finally, a CYP88D6-CPR fusion protein was constructed, and different CPRs from various plant sources were investigated to optimize the CYP88D6 oxidation system, ultimately leading to the improved yield of 11-oxo-β-amyrin.

Sun et al. [209] focused on studying the expression levels of cytochrome CYP88D6 and CPR, and their ratio’s effect on 11-oxo-β-amyrin yield. The results revealed that high CPR expression levels led to growth defects. Moreover, an increased CPR:CYP88D6 expression ratio decreased the concentration of 11-oxo-β-amyrin catalyzed by CYP88D6. Conversely, high CYP88D6:CPR expression ratios improved the efficiency of electron transfer between CYP88D6 and CPR, thereby increasing 11-oxo-β-amyrin yield. With these optimizations, a conversion rate of 91.2 % from β-amyrin to 11-oxo-β-amyrin was achieved in brewing yeast Y321. During fed-batch fermentation, the yield of 11-oxo-β-amyrin was further increased to 810.6 mg/L, laying the foundation for the construction of high-yield glycyrrhetinic acid strains.

Zhu et al. [117] constructed a glycyrrhetinic acid biosynthesis pathway in yeast and demonstrated that CPR can significantly enhance the efficiency of glycyrrhetinic acid synthesis. Previous studies have demonstrated that CYP72A63 is capable of utilizing 11-oxo-β-amyrin as a substrate to generate glycyrrhetinic acid in yeast-engineered strains [117]. However, due to low selectivity, the products consist of a mixture of rare licorice triterpenoids, including glycyrrhetol, glycyrrhetaldehyde, glycyrrhetinic acid, and an isomer of glycyrrhetol, 29-OH-11-oxo-β-amyrin, in a ratio of 45.2:21.4:29.0:4.4. The difficulty in separating and purifying these compounds has limited the production of glycyrrhetinic acid. Sun et al. [210] engineered CYP72A63 mutants to selectively produce each of the four compounds through a combination of homology modeling, molecular docking, and mutagenesis experiments. Model analysis indicated that the typical proton transfer pathway is essential for P450 activity, and that restrictions in proton transfer hinder catalytic performance. By identifying key amino acids involved in proton transfer and conducting further mutagenesis experiments, the catalytic activity of CYP72A63 mutants was improved. Then Sun et al. [211] regulated the genes NHMGR, SIP4, and GPP1 to establish metabolic and microenvironmental compatibility between the licorice triterpenoid biosynthesis pathway and the yeast host, thereby achieving efficient synthesis of licorice triterpenoids in yeast. In a 5L fermenter, the production of licorice triterpenoids reached 4.92 g/L, including 0.96 g/L of 11-oxo-β-amyrin, 2.94 g/L of glycyrrhetaldehyde, and 1.02 g/L of glycyrrhetinic acid. After successfully accomplishing the complete biosynthesis of β-amyrin and glycyrrhetinic acid, the two pivotal precursors of glycyrrhizic acid and 3-O-monoglucuronosyl glycyrrhetinic acid in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Xu et al. [212] pioneered the whole-cell factory synthesis of glycyrrhizic acid and 3-O-monoglucuronosyl glycyrrhetinic acid in yeast. They achieved this goal through the exploration, characterization, and introduction of glycosyltransferases and UGTs from mammals. The yields reached 5.98 and 2.31 mg/L, respectively. This innovative approach offers a new idea to addressing resource scarcity issues in the production of glycyrrhizic acid and other scarce natural products.

Significant advances have also been achieved in the synthetic biology of flavonoids in licorice. One research searched the G. uralensis genome and comparative transcriptome databases, analyzed and selected homologous genes in known flavonoid biosynthesis pathways, and reconstructed the entire liquiritin biosynthesis pathway in yeast [213]. This study used in vitro and in vivo methods to validate the catalytic functions of candidate genes and achieved the de novo synthesis of liquiritigenin in S. cerevisiae for the first time, utilizing endogenous yeast metabolites as precursors and cofactors. GuPAL1 and GuC4H1 were also simultaneously introduced into the yeast strain WAT11, resulting in a recombinant yeast called WM1 that could produce p-coumaric acid under galactose induction. After 36 h of cultivation, the p-coumalic acid content reached 7.59 mmol/L. When the vectors carrying Gu4CL1 and GuCHS1::GuCHR1 were introduced into WM1, a yeast strain named WM2-1 capable of producing small amounts of isoliquiritigenin was obtained. No isoliquiritigenin was detected when GuCHS1 and GuCHR1 were coexpressed with substrates in yeast strain WM1. GuCHI1 and GuUGT1 were subsequently introduced into WM2-1, resulting in the yeast strain WM3-1, which is capable of producing liquiritigenin, and WM4-1, which is capable of producing liquiritin. In WM4-1, a higher proportion of isoliquiritigenin was glycosylated before isomerization, leading to a 4.7-fold higher yield of isoliquiritoside compared with liquiritin.

To enhance the conversion of upstream metabolites toward downstream flavonoid structures along the liquiritin pathway in the described recombinant strains, this study attempted to overexpress the key genes involved in isoliquiritigenin biosynthesis [213]. The results showed that yeast WM2-2, which overexpressed GuCHS1::GuCHR1, significantly increased isoliquiritigenin production. The isoliquiritigenin yield in WM2-2 was 18 times higher than that in WM2-1. GuCHI1 was overexpressed in WM3-1 and WM4-1 to address the issue of significantly lower liquiritin production compared with isoliquiritoside in WM4-1. This process led to a 1.3-fold increase in liquiritigenin and a 2.1-fold increase in liquiritin production. Furthermore, the simultaneous overexpression of GuCHS1::GuCHR1 and GuCHI1 resulted in a 5.3-fold increase in liquiritigenin production and a 6.4-fold increase in liquiritin production.

Yin et al. [213] also found that overexpressing GuCHI1 and GuCHS1::GuCHR1 in the yeast system increased the yield of downstream products and significantly increased the accumulation of upstream precursor compounds such as p-coumaric acid. This phenomenon suggested interactions between different genes in the liquiritin biosynthesis pathway. In addition, the downstream products of the liquiritin biosynthesis pathway might play a role in the positive or negative feedback on the upstream pathway. This type of cross-talk and regulation is common in metabolic pathways, where the production of one compound can influence the synthesis of another at different points in the pathway. Understanding these interactions is crucial for optimizing the production of specific compounds through metabolic engineering.

In addition to liquiritin, synthetic biology research on other flavonoid compounds has also made breakthroughs. Wang et al. [214] identified and functionally characterized the apiosyltransferase GuApiGT in G. uralensis. They reconstructed the de novo synthesis pathway of liquiritin apioside and isoliquiritin apioside in Nicotiana benthamiana by introducing 12 genes. The pathway was divided into three modules. For flavonoid aglycone module, AtPAL, AtC4H, At4CL, AtCHS and GuCHR were used to synthesize isoliquiritigenin. Pgm, GalU, CalS8 and UAXS were used for UDP-donor module to produce UDP-Glc and UDP-Api. For glycosyltransferase module, GuApiGT and GuGT14 were used as glycosyltransferases. This approach successfully achieved the total synthesis of liquiritin apioside (5.46 mg/g) and isoliquiritin apioside (4.73 mg/g) in N. benthamiana, with yields comparable to those found in licorice root. Additionally, by altering the gene combination in the flavonoid module, the authors achieved the total synthesis of eight other apiosides.

Conclusions and future prospects

Glycyrrhiza plants and their active compounds have extensive medicinal prospects. These medicinal plants have a history of thousands of years of use in traditional Chinese medicine and have been cultivated to meet the demands for herbal medicine and chemical extraction. Molecular design approaches for producing improved licorice varieties and efficiently producing triterpenoids and flavonoids have been widely researched. Furthermore, the utilization of resources from other licorice species, in addition to those defined in pharmacopeias, is important for pharmaceutical and healthcare products. A forward-looking strategy based on multiomic approaches has been proposed and involves exploring the genetic resources of the Glycyrrhiza genus and improving the quality, biosynthesis, and regulation of active compounds and the efficiency of in vitro production (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Strategies for the development and utilization of resources of Glycyrrhiza plants. Firstly, the resources of Glycyrrhiza species are collected to obtain their multi-omics information, such as genome, transcriptome and metabolome. Through these genetic information, the unknown biosynthesis pathway of active ingredients in licorice could be analyzed. The target medicinal ingredients are then produced industrially through molecular breeding and synthetic biology. Molecular breeding methods mainly include molecular marker-assisted breeding, genetic engineering breeding, and molecular designing breeding. The synthetic biology of licorice could be improved in terms of biological elements, metabolic pathways, chassis cells and fermentation process. Finally, these medicinal ingredients are used for drug development and clinical treatment of diseases.

Population genomics of Glycyrrhiza

Conducting large-scale comparative analyses of metabolism and genome is an effective strategy for elucidating the mechanisms behind the metabolic diversity of certain compounds within a taxonomic group. Medicinal plants contain a wealth of secondary metabolites closely related to their pharmacological activities. However, the synthesis of these secondary metabolites in plants is a complex process, with significant variation in both the structure and content of these metabolites [215]. Over the past two decades, a considerable number of species genomes have been sequenced, providing comprehensive support for advancements in medicinal plant genomics and establishing a theoretical foundation for revealing the biosynthetic pathways of secondary metabolites [216].

Recent studies have explored the metabolic diversity of the same type of compounds within a taxonomic group by focusing on functional validation, structural analysis, and comparative genomics. For instance, in the genus Papaver, species like P. rhoeas, P. setigerum, and P. somniferum exhibit varying levels of noscapine and morphinan compounds, with P. somniferum containing the highest amounts [217]. Yang et al. [217] constructed high-quality genomes for these three species and analyzed the relationship among copy numbers of key genes in the morphinan synthesis pathway, gene expression, and morphinan content. They found that the CODM, T6ODM, and COR genes are under positive selection in P. somniferum, providing new insights into the evolution of the benzylisoquinoline alkaloid biosynthetic pathway. In the case of abietane-type diterpenes (ATDs), specific to the genus Salvia, Hu et al. [218] demonstrated that the chemical diversity of ATDs is driven by the functional diversification of the cytochrome P450 subfamily CYP76AK, resulting in oxidation differences at the C-20 position of the terpene skeleton. This diversification results in three distinct catalytic features with noticeable phylogenetic divergence, shaping the chemical diversity of ATDs within Salvia plants. An et al. [219] conducted comparative genomic studies on Menispermaceae species, showing that stereoselective differences and functional diversification (C-C linkage differences) among CYP80G members in different species have led to the structural diversity of benzylisoquinoline alkaloids.

Research on Glycyrrhiza species is somewhat limited. Molecular biology and pharmacological studies have predominantly focused on G. uralensis, G. glabra, and G. inflata. Research on other licorice species within this genus has lagged behind, especially in terms of multiomics. Although the genome of G. uralensis has been published, an ongoing research aims to sequence and assemble the genomes of the other two species mentioned in pharmacopeias, namely, G. glabra, and G. inflata. In addition to the species used for medicinal purposes, genomic studies must also be conducted on nonmedicinal species. Such research can explore the evolution of enzyme genes in the glycyrrhizic acid biosynthesis pathway, trace the origins of these genes, and investigate why some species produce glycyrrhizic acid and others do not. This information is of great significance for breeding high-yield licorice varieties that produce glycyrrhizic acid and for the field of synthetic biology related to glycyrrhizic acid biosynthesis.

Biosynthetic pathway elucidation of active compounds in licorice

Licorice contains numerous active compounds that can be used for medicinal purposes, but only the biosynthetic pathways of glycyrrhizic acid and liquiritin have been fully elucidated. Most natural products share common upstream metabolic pathways that have been relatively well-studied, including the mevalonate pathway, methylerythritol phosphate pathway, shikimate pathway, and malonic acid pathway [220]. Therefore, elucidating the biosynthetic pathway of a specific natural product, or a particular class of them, typically refers to uncovering its downstream, specialized branch metabolic pathways. To investigate the unknown biosynthetic pathways of active compounds in licorice, the following strategies can be employed.

Firstly, hypothesize potential biosynthetic pathways based on isolated and identified intermediate compounds, and further confirm these pathways through isotope tracing. Hypothesizing a possible metabolic pathway based on existing knowledge is the first step in elucidating natural product biosynthetic pathways [221]. The principles of chemical reactions and the structures of intermediate compounds can both provide clues for predicting the synthesis pathway. Isotope tracing is commonly used for pathway prediction and validation. Isotope-labeled precursor compounds have the same biological and chemical properties as unlabeled compounds but differ in molecular mass, allowing them to be distinguished through mass spectrometry and nuclear magnetic resonance instruments. Thus, after feeding isotope-labeled precursors, any newly isotope-labeled compounds detected are considered intermediates or end products of the metabolic pathway [222].

Next, use transcriptome analysis to obtain co-expression data of related genes or conduct genome scans to identify gene clusters associated with secondary metabolism, thus narrowing down candidate genes. The rapid development of high-throughput sequencing technology has made it possible to quickly and affordably obtain the genetic information of a species. However, selecting candidate genes potentially involved in the biosynthesis of specific natural products from so many genes remains a highly challenging task. Currently, co-expression analysis based on transcriptome sequencing and gene cluster mining based on genome sequencing are the two main methods for identifying candidate genes [223], [224].

Finally, heterologously express the candidate genes and test enzyme activity to confirm their catalytic functions, and develop a licorice genetic transformation system to study the inhibition or overexpression of relevant enzyme-coding genes in the original species, further verifying enzyme function within the species. By identifying and validating the functions of all enzymes in the pathway, the goal of pathway elucidation can ultimately be achieved. Gene co-expression analysis and gene cluster mining can effectively narrow down the range of candidate genes, reducing the workload for functional validation. Due to the structural diversity of natural products, the enzymes involved in their biosynthetic pathways also exhibit great diversity, meaning that each enzyme’s functional validation requires a unique approach. Functional verification of candidate genes involves a combination of experimental techniques in molecular biology and analytical chemistry, such as heterologous expression and enzyme activity assays, gene suppression, and gene overexpression [225], [226], [227]. This is the most critical and challenging step in elucidating natural product biosynthetic pathways.

The elucidation of the biosynthetic pathways of natural products in licorice will provide a wealth of components for synthetic biology research on active compounds in licorice, advancing the development of this field and offering new sources for the production and research of natural drugs derived from licorice. Additionally, pathway elucidation will provide functional molecular markers for molecular breeding research in licorice, accelerating the selection and cultivation of high-quality varieties and promoting the growth of the licorice industry.

Breeding of licorice

The wild resources of licorice are scarce, and the active compound content in cultivated licorice is generally low, failing to meet pharmacopoeia standards [228]. There is an urgent need to improve important traits and quality in licorice breeding. Licorice breeding has a long history. As early as the 1990 s, researchers reported studies on radiation breeding of licorice [229]. The results showed that plants selected from treatments with 60,000 roentgen of gamma-ray irradiation exhibited excellent medicinal traits, including straight stems, dense texture, rich sweetness, reddish-brown skin, and thicker bark. Additionally, these plants had desirable qualities such as higher dry weight and increased glycyrrhizic acid content. These are the main traits and internal qualities that licorice breeding research aims to acquire and continuously improve. Unfortunately, no new variety was developed from this work. In 2014, the first new licorice variety in China, “Guogan No. 1” was successfully bred. Compared to other licorice sources, the seeds of “Guogan No. 1” have lower values for seed traits such as thousand-seed weight, length, width, and height. However, “Guogan No. 1” exhibits more vigorous above-ground growth and higher levels of key medicinal components [230].