Abstract

Cancer stem cells (CSCs) are proposed to account for the progression, metastasis, and recurrence of diverse malignancies. However, the disorganized vasculars in tumors hinder the accumulation and penetration of nanomedicines, posing a challenge in eliminating CSCs located distantly from blood vessels. Herein, a pair of twin-like small-sized nanoparticles, sunitinib (St)-loaded ROS responsive micelles (RM@St) and salinomycin (SAL)-loaded GSH responsive micelles (GM@SAL), are developed to normalize disordered tumor vessels and eradicate CSCs. RM@St releases sunitinib in response to the abundant ROS in the tumor extracellular microenvironment for tumor vessel normalization, which improved intratumor accumulation and homogeneous distribution of small-sized GM@SAL. Sequentially, GM@SAL effectively accesses CSCs and achieves reduction-responsive drug release at high GSH concentrations within CSCs. More importantly, RM@St significantly extends the window of vessel normalization and enhances vessel integrity compared to free sunitinib, thus further amplifying the anti-tumor effect of GM@SAL. The combination therapy of RM@St plus GM@SAL produces considerable depression of tumor growth, drastically reducing CSCs fractions to 5.6% and resulting in 78.4% inhibition of lung metastasis. This study offers novel insights into rational nanomedicines designed for superior therapeutic effects by vascular normalization and anti-CSCs therapy.

Key words: Super-small micelles, Twin-nanoparticles, Tumor microenvironment response, Vascular normalization, Tumor accumulation, Tumor penetration, Cancer stem cells, Lung metastasis

Graphical abstract

A pair of twin-like small-sized nanoparticles, sunitinib (St)-loaded ROS response micelles (RM@St) and salinomycin (SAL)-loaded GSH response micelles (GM@SAL), are developed to normalize disordered tumor vessels and eradicate CSCs.

1. Introduction

The efficient delivery of anticancer agents to solid tumors is critical to their success in treatment and diagnosis. In recent years, nanomaterials have been widely used to enhance drug delivery, which preferentially accumulates in tumor tissue through enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect, and their targeting ability relies on the abundance and maturity of blood vessels in tumor tissues1, 2, 3. Unlike blood vessels in normal tissues, tumor angiogenesis proceeds in a dysregulated manner due to the relentless production of proangiogenic growth factors such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGFR)4, 5, 6, 7. Lack of proper pericyte-covered tumor vessels exhibits morphological abnormalities and increased leakage, facilitating the passive targeting of nanomedicines into the tumor tissue during blood circulation8. However, the poor organization and tortuous structure of immature tumor vessels also contribute to elevated interstitial fluid pressure (IFP) and impaired perfusion function, which impairs drug delivery and homogeneous distribution in the tumor, ultimately leading to inadequate antitumor efficacy9, 10, 11.

It has been revealed that treatment with anti-angiogenic drugs can normalize tumor vessels, which repair abnormal structures to reduce leaks and IFP and restore proper perfusion functionalities in tumors9,12. For example, bevacizumab as a VEGF antibody improves the treatment efficacy in combination with chemotherapy in clinical trials by the hypothesis of tumor vascular normalization13,14. While reducing permeability and pore size in the vessel walls during vascular normalization treatments contradicts the entry of nanoparticles into tumor tissue15. Although the nanoparticles have size-based advantages, they still suffer from steric and hydrodynamic hindrances that impede transport during tumor vessel normalization16,17. It is interesting that nanoparticles with a super-small diameter (<12 nm) entered vascular-normalized tumors more efficiently than larger (60, 125 and 250 nm) nanoparticles15. It was reported that vascular normalization with DC101 enhanced the effectiveness of only Abraxane (∼10 nm) but exerted no discernible impact on Doxil (∼100 nm)15. Vascular normalization as a complementary therapeutic paradigm is more suitable to be used in combination with small-sized nanomedicines to promote tumor accumulation and penetration, facilitating the resolution of intricate challenges in tumor treatment.

Furthermore, the clinical overall survival is hampered by treatment resistance, metastasis, and recurrence, in which the cancer stem cells (CSCs) are recognized as the primary culprit to these factors18, 19, 20. Although anti-CSC agents, such as salinomycin (SAL), have shown high potency in killing CSCs, it remains challenging to eradicate CSCs located in the hypoxic regions and distant from the chaotic tumor blood vessels due to inadequate drug concentration and inhomogeneous distribution in tumor tissue21, 22, 23, 24. In this sense, tumor accumulation and deep penetration are highly desired for CSCs targeted therapy to overcome this dilemma. TGF-β inhibitor and collagenase have been explored to regulate hostile tumor microenvironment (TME) for enhanced tumor penetration and CSCs therapy25, 26, 27, 28, 29. However, it is essential to recognize that achieving deep penetration and CSCs accessibility is based on the efficient accumulation of drugs, which is impeded by insufficient tumor vascular perfusion. Vascular normalization, repairing the abnormal structure and function of the tumor vasculature, can improve the intratumor delivery of nanomedicines, especially the accumulation and penetration of small-sized nanomedicines to access CSCs fractions in tumors effectively30, 31, 32, 33. Currently, it is a big challenge to construct these nanoparticles that meet the small size requirement and, meanwhile, precise delivery and on-demand release of multitherapeutic agents for vascular normalization and eradication of CSCs.

Herein, a pair of twin-like zwitterionic micelles with small size was customized for combination therapy of breast cancer and its metastasis via vessel normalization and anti-CSCs (Fig. 1). Specifically, twin-like micelles were comprised based on zwitterionic hyperbranched polycarbonate, with one type modified using oxalate-containing linkers to encapsulate sunitinib (RM@St) and the other type introduced with disulfide bonds to load salinomycin (GM@SAL). RM@St rapidly released sunitinib in the abundant ROS of tumor extracellular microenvironment to reshape tumor vessels, while the GM@SAL would achieve reduction-responsive drug release under high GSH concentration within cancer cells and CSCs. Vessel normalization induced by RM@St improved accumulation and homogeneous distribution of small-sized GM@SAL in tumors, facilitating more effective access to CSCs. More importantly, small-sized RM@St intelligently adjusted the required dosage of antiangiogenic drugs to avoid excessive vascular pruning, extending the window of vessel normalization and enhancing vessel integrity compared to free sunitinib. This further amplified the anti-tumor effect of GM@SAL. The combining tumor vasculature remodeling strategy with nanoparticle size design improved the delivery of small nanoparticles into solid tumors and enhanced outcomes for anti-CSCs therapy.

Figure 1.

(A) Synthesis of small-sized twin-nanoparticles (RM@St and GM@SAL). (B) Schematic illustration of small-sized twin-nanoparticles for tumor vascular normalization to enhance drug accumulation and penetration in tumors for potent eradication of cancer stem-like cells.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials and reagents

Oxalic dichloride (98%), 2-hydroxyethyl acrylate (96%), N,N-bis(acryloyl)cystamine (BAC, 97%), triethylamine (Et3N, 99%), 3,6-dioxa-1,8-octanedithiol, 2-hydroxy-4′-(2-hydroxyethoxy)-2-methylpropiophenone (I2959, 98%) were obtained from Energy Chemical (Shanghai, China). Sunitinib (St, 99%) was obtained from MedChemExpress (Monmouth Junction, NJ, USA). Salinomycin sodium salt (SAL·Na, >98%) was obtained from Macklin (Shanghai, China). CCK-8 was purchased from Keygen Biotech (Nanjing, China). Bouin’s fluid was obtained from Sbjbio Life Sciences Co., Ltd. (Nanjing, China). Zwitterionic hyperbranched polycarbonates (hPCCB and hPCCB-AC) were produced according to our previous work34.

2.2. Synthesis of oxalate-linked zwitterionic hyperbranched polycarbonates (hPCCB-oxa-AC)

The ROS-responsive linker was first synthesized through the one-side acylation reaction of oxalyl dichloride and 2-hydroxyethyl acrylate35. Oxalic dichloride (0.38 g, 3.00 mmol) was dissolved in anhydrous dichloromethane in the ice water bath, followed by the gradual addition of 2-hydroxyethyl acrylate (0.07 g, 0.60 mmol). After stirring for 4 h, the ROS-responsive linker was collected by evaporating excess oxalic dichloride. Subsequently, the linker, when redissolved in anhydrous dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), was introduced into a mixture containing hPCCB (50% zwitterion units) (1.00 g, 1.13 mmol hydroxyl group) and Et3N (0.17 g, 1.70 mmol). Following an overnight reaction, the ROS-responsive linker was grafted onto hPCCB through an acylation reaction, and the reaction solution was dialyzed by deionized water. The hPCCB-oxa-AC was collected as a white solid (0.93 g, 81% yield) after freeze-drying under vacuum.

2.3. Synthesis of disulfide bond-linked zwitterionic hyperbranched polycarbonates (hPCCB-SS-AC)

Under a nitrogen atmosphere, 3,6-dioxa-1,8-octanedithiol (0.38 g, 2.07 mmol) and Et3N (0.07 g, 0.69 mmol) were dissolved in methanol. Subsequently, hPCCB-AC (50% zwitterion units, 15% acrylate units) (2.00 g, 0.69 mmol of AC units) dissolved in a mixture solution of methanol/N,N-dimethylformamide (2/1, v/v) was dropwise added. The mixture was stirred for another 12 h to complete the Michael-type addition reaction of thiol groups and double bonds. The product was purified by precipitating it twice in cold diethyl ether. hPCCB-SH was acquired following vacuum drying (1.85 g, 89% yield).

After that, hPCCB-SH (2.00 g, 0.65 mmol of SH units), when redissolved in a mixture solution of methanol/N,N-dimethylformamide (2/1, v/v), was dropwise added to the mixture of BAC (0.51 g, 1.95 mmol) and Et3N (0.08 g, 0.78 mmol). After an overnight reaction, the product was purified by dialysis in methanol, transferred to deionized water, and freeze-dried. The final product, hPCCB-SS-AC, was obtained as a white solid (1.80 g, 83% yield).

2.4. Preparation of twin-like micelles

To prepare the ROS-responsive micelles (RM) and GSH-responsive micelles (GM), 10 mg of hPCCB-oxa-AC or hPCCB-SS-AC was directly dispersed in 2 mL of PBS under sonication. Subsequently, a UV initiator (I2959, 0.5 mg) was introduced to the micelle suspension, which underwent UV light (20 mW/cm2) for 10 min, forming either RM or GM. As a control, large particle-size GSH-responsive micelles (LGM) were also prepared using the reverse nanoprecipitation method. Under stirring, 2 mg of hPCCB-SS-AC, dispersed in 1 mL water, was rapidly added to 20 mL of acetone containing I2959 (0.2 mg). This mixture underwent cross-linking under UV light, and the acetone was evaporated to obtain LGM. Sulfonate Cy5-NH2 was grafted onto freshly prepared micelles through an amidation reaction to obtain Cy5-labeled micelles for fluorescence imaging. The size distribution and zeta potential of micelles were measured by dynamic light scattering (DLS, Anton Paar Litesizer 500, Austria). Additionally, the morphologies of micelles were also visualized using a transmission electron microscope (TEM, Hitachi, Japan) following staining with 2% phosphotungstate. The colloidal stability of micelles in 10% FBS solution was conducted through turbidimetry, with monitoring of the absorbance at 500 nm using a multimode microplate reader (Molecular Devices spectramax@i3x, USA).

2.5. Investigation of ROS/GSH-responsive behavior

NMR and dilution stability analysis were employed to explore the ROS/GSH responsive behavior of the micelles. To mimic the ROS environments within TME, the hPCCB-oxa-AC (10 mg) was dispersed in PBS with H2O2 (50 μmol/L). Following a 24 h incubation, the solution was dialyzed with deionized water and subsequent vacuum freeze-drying for 1H NMR analysis. Similarly, the hPCCB-SS-AC (10 mg) was dispersed in PBS with GSH (10 mmol/L) to stimulate tumor intracellular environments. After incubation for 24 h, the solution underwent the same treatment for 1H NMR analysis. Dilution stability was conducted under different conditions to reveal the degradation of crosslinking micelles. For RM, the RM solution was incubated for 24 h with or without H2O2 (50 μmol/L) and then monitored for particle size change under dilution. Similarly, the GM solution was incubated for 24 h with or without GSH (10 mmol/L) and evaluated.

2.6. Drug loading and in vitro release

St solution in DMSO was introduced into a freshly prepared RM solution under sonication and vortex. Afterward, the resulting mixture solution was dialyzed against deionized water using a dialysis bag (MWCO 3.5 kDa) to eliminate unentrapped St and DMSO, yielding RM@St. SAL·Na, dissolved in DMSO, underwent acidification using hydrochloric acid to remove sodium salt. The loading procedures described above were then applied to develop either GM@SAL or LGM@SAL. The concentration of the loaded drug was determined by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) spectrometry (C18 reversed-phase column, Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA). Drug loading content (DLC) and drug loading efficiency (DLE) were calculated using the following Eqs. (1), (2):

| DLC (wt %) = (weight of loaded drug / total weight of micelles and loaded drug) × 100 | (1) |

| DLE (%) = (weight of loaded drug / weight of drug in feed) × 100 | (2) |

1.0 mL of RM@St was enclosed within a dialysis bag (MWCO 3.5 kDa) and immersed in 25 mL of buffers, either with or without H2O2, to mimic the extracellular oxidation environments in TME. Subsequently, the setup was incubated at 37 °C with gentle agitation. Similarly, a dialysis bag containing GM@SAL was placed into 25 mL of corresponding buffers, either with or without GSH, to replicate the tumor intracellular reduction environments. At predetermined intervals, 5.0 mL of the release medium was collected, and an equivalent volume of fresh medium was replenished. These experiments were replicated three times within each group. The concentrations of released drugs were determined using HPLC to construct the drug release profile.

2.7. Homolysis assay

The suspension of erythrocytes was prepared based on our previous work. This erythrocyte suspension was individually mixed with RM, LGM, and GM at various concentrations. Triton X-100 solution and saline were served as positive and negative controls. Following a 2 h incubation at 37 °C, the mixed suspensions were centrifuged at 2000 rpm (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA) and photographed. The absorbance of the supernatant at 545 nm was monitored, and the hemolysis percentage was calculated using the following Eq. (3).

| Hemolysis percentage (%) = (Asample - Anegative) / (Apositive - Anegative) × 100 | (3) |

2.8. In vivo pharmacokinetics

All animal studies were conducted following the approved protocol of the China Pharmaceutical University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. The healthy female BALB/c mice received intravenous injections of free Cy5, Cy5-labeled RM, or Cy5-labeled GM. Blood samples were collected at predetermined time points (0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 9, and 12 h) from the orbit sinus. Each blood sample (30 μL) was mixed with 0.6 mL of normal saline and centrifuged at 2000 rpm for 5 min. The fluorescence intensity of the resulting supernatant was measured using a microplate reader (λex = 641 nm, λem = 671 nm, Molecular Devices). Additionally, fluorescence images of ex vivo blood at 2 and 6 h postinjection were acquired by the IVIS system (Lumina II, Caliper, MA).

2.9. Formation and characterization of CSCs-enriched tumorspheres

The 3D CSCs-enriched tumorspheres were developed by culturing metastatic 4T1 cells in 6-well ultralow attachment plates (40000 cells per well) with the CSCs culture medium, which was comprised of DMEM/F-12 culture media (Gibco, Carlsbad, CA, USA), 5 μg/mL of insulin (Beyotime, Shanghai, China), 20 ng/mL of EGF (Peprotech, Rocky Hill, NJ, USA), 20 ng/mL of bFGF (Peprotech, Rocky Hill, NJ, USA), 1 × B27 (Gibco, Carlsbad, USA) and 0.4% (w/v) low endotoxin bovine serum albumin (Beyotime, Shanghai, China). After 7 days of culture, the 3D tumor spheroids were formed for further detection.

The stemness of 3D tumorspheres was characterized by evaluating typical CSCs markers and tumorigenesis assay. Firstly, tumorspheres were digested using accutase at 37 °C for 15 min to generate single cells. Then, the cells were stained with anti-CD44-PE (553134, BD Pharmingen, USA) and anti-CD24-FITC (561777, BD Pharmingen, USA) antibodies for the flow cytometry analysis (Backman CytoFLEX, USA). By contrast, the expressions of CD44 and CD24 in parent 4T1 cells were also determined. For tumorigenesis assay, the CSCs tumorsphere cells or parent 4T1 cells (4000 per mouse) were injected subcutaneously into the right hind flanks of mice, respectively, and the subsequent tumor development was continuously observed.

The intracellular GSH was determined using a GSH assay kit. CSCs or 4T1 cells were harvested, washed with PBS and counted. The cells were lysed by four rounds of rapid freezing in liquid nitrogen followed by quick thawing at 37 °C. The supernatant was obtained by centrifugation at 7000×g for 10 min and analyzed by the GSH assay kit by measuring the absorbance at 405 nm.

2.10. Cytotoxicity assays

The cytotoxicity of SAL-loaded micelles was assessed using the CCK-8 assay. 4T1 cells and CSCs spheres were enzymatically digested, collected, and subsequently seeded in separate 96-well plates at concentrations of 4000 and 10,000 cells per well. These cells were then incubated overnight under 5% CO2 at 37 °C. Prescribed amounts of free SAL, LGM@SAL and GM@SAL were added to their respective wells. After 48 h, cell viability was analyzed via CCK-8 assay.

2.11. Penetration and destruction in CSCs spheres

To evaluate the impact of particle size on the penetration and elimination ability of CSCs spheres, the uniform CSCs spheres were transferred to a coverglass bottom dish and incubated with Cy5 labeled GM or LGM solution for 6 h. Subsequently, the fluorescence distribution at various depth layers within the CSCs spheres was observed by CLSM. Furthermore, the CSCs spheres were also transferred to 12-well ultralow attachment plates and treated with GM@SAL or LGM@SAL solution (10 μmol/L) for a duration of 6 days. The CSCs spheres were observed daily by optical microscopy (Zeiss LSM 800, Germany). The efficiency of the sphere disruption was quantified as the ratio of the maximum sectional area of spheres at the end of the treatment to the pre-treatment area, with calculations carried out using ImageJ.

2.12. Endothelial cell migration assay

The impact of St formulation on endothelial cell migration was assessed using wound healing, Transwell assay and tubule formation assay. In the wound healing experiments, 200 μL pipette tips were employed to manually generate wounds on the HUVEC monolayer with 90%-100% confluency. The scraped-off cells were washed away, and fresh serum-free medium containing VEGF (30 ng/mL) was replenished. Subsequently, free St or RM@St (St concentration: 4 μmol/L) with or without 50 μmol/L H2O2 pretreatment for 4 h were introduced to each well and further incubated for 48 h. Images of the wounds were captured both before and after drug treatment using an optical microscope.

In the Transwell assay, HUVEC (5 × 104 cells) in 200 μL of serum-free starvation medium with VEGF (30 ng/mL) were seeded into the upper chambers of 24-well inserts (8 μm, Corning, USA) pre-coated with Matrigel (Corning, USA). 500 μL DMEM with 10% FBS was added to the lower chamber. St formulations (St concentration: 4 μmol/L) were introduced into the upper chamber for a 12 h incubation. The insert chambers were subsequently taken out and rinsed with PBS, and any cells on the upper surface of the transwell insert were removed using swabs. The migrated cells on the lower surface of the transwell insert were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, followed by staining with 0.1% crystal violet. Finally, these cells were observed and recorded using a light microscope.

In the tubule formation assay, HUVEC were seeded in 48-well plates pre-plated with matrigel at 6 × 104 cells per well. St formulations (St concentration: 2 μmol/L) were added to each well for an 8 h incubation. The formation of tube-like structures in each group was examined by optical microscopy.

2.13. Vascular normalization therapy

4T1 cells (2.5 × 106 cells) were subcutaneously implanted on the right hind flanks of the mice to establish the 4T1 breast cancer model. When the tumor reached a size of 70 mm3, various dosages of St (5, 15, and 25 mg/kg) were administered intravenously on Days 0, 2 and 4 to determine the optimal dose for tumor vascular normalization. On Day 6 of treatment, tumor slices from St treated mice were subjected to double staining for CD31 (red) and α-SMA (green) to assess vascular morphology (endothelial cells: CD31+, pericyte cells: α-SMA+/CD31+). Additionally, two-photon imaging was used to visualize vascular distribution in mice treated with 15 mg/kg St. Following intravenous injection of 10 mg/kg fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labeled dextran (MedChemExpress), the mice were anesthetized. The skin surrounding the tumor was carefully excised, and the tumor was fixed to prevent tremors caused by heartbeat during observation. Subsequently, tumor vasculature was observed using an Olympus FVMPE-RS microscope with a 20x objective lens. Three-dimensional reconstruction of tumor vasculature was performed and presented.

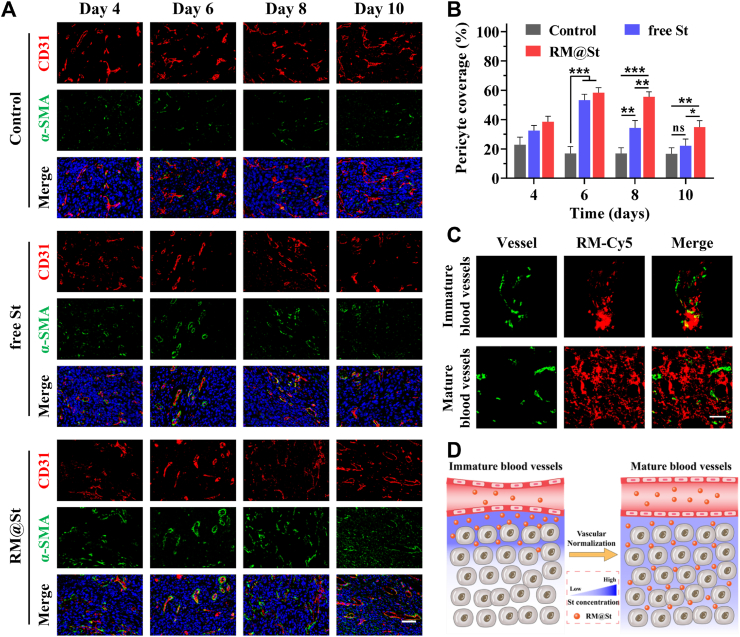

The impact of small-sized RM@St versus free St on vascular normalization therapy was also investigated. Mice were divided into three groups and received intravenously administered PBS, free St and RM@St (St dosage: 15 mg/kg) every other day. On Days 4, 6, 8 and 10 following treatment, corresponding tumor slices were subjected to double staining for CD31 (red) and α-SMA (green) to assess vascular morphology and calculate the pericyte coverage. Furthermore, on Days 0 and 6 of vascular normalization therapy, corresponding to the initiation of treatment and the vascular normalization window period, mice were injected with Cy5-labeled RM@St. Tumor slices were stained with CD31, and the distribution of RM@St around tumor blood vessels was observed.

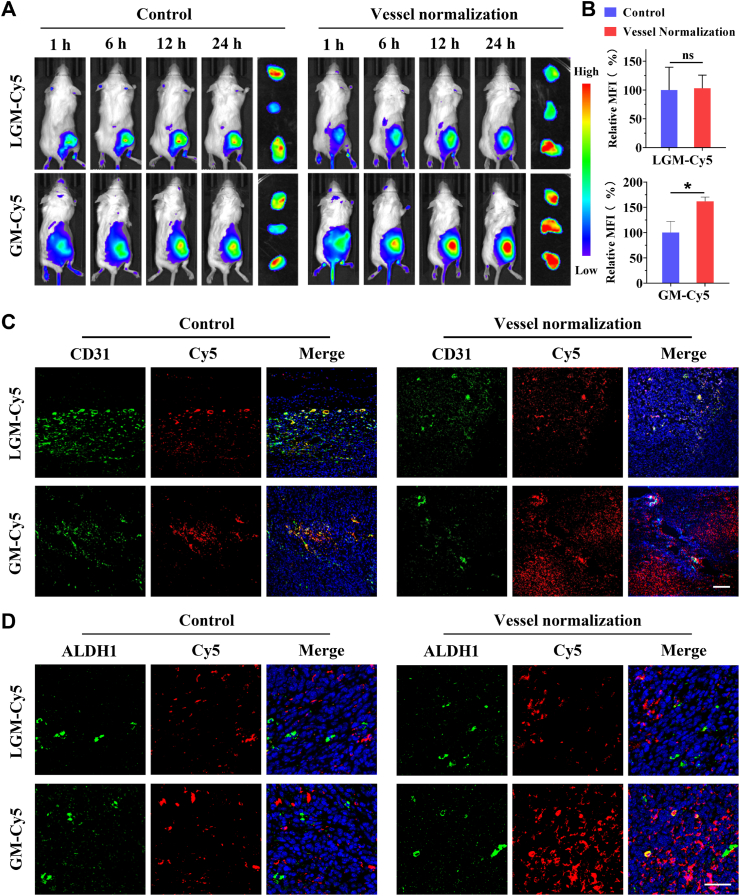

2.14. Impact of vascular normalization on tumor accumulation, penetration and CSCs accessibility of nanoparticles

4T1 tumor-bearing mice respectively received with PBS or RM@St (St dosage: 15 mg/kg) on Days 0, 2 and 4. On Day 6 after treatment, Cy5-labeled GM or LGM was intravenously injected into the mice (Cy5 dosage: 0.25 mg/kg), respectively. At predetermined time points, the mice were imaged by IVIS. Twenty-four hours after injection, the tumors were excised for fluorescence imaging and semi-quantification analysis. Further, immunofluorescence sections of tumor tissue stained with CD31 or ALDH1A1 (a marker for CSCs) were conducted to investigate nanocarrier penetration and CSCs accessibility within the tumors.

2.15. In vivo therapeutic effects

4T1 tumor-bearing mice with the tumor size of 70 mm3 were randomly distributed into eleven groups (n = 6) and subjected to the following treatments: (1) PBS; (2) free St; (3) RM@St; (4) free SAL; (5) LGM@SAL; (6) GM@SAL; (7) free St + free SAL; (8) free St + LGM@SAL; (9) free St + GM@SAL; (10) RM@St + free SAL; (11) RM@St + LGM@SAL; (12) RM@St + GM@SAL. Mice were treated on Days 0, 2, 4, 6, and 8 (St dosage: 15 mg/kg, SAL dosage: 5 mg/kg). The body weight and tumor volume of mice were recorded every 2 days. On Day 24 of treatment, mice were euthanized, and the tumors were collected, photographed and weighed to evaluate the inhibition of tumor growth. Additionally, the lungs were also collected, fixed with Bouin’s buffer, and photographed. Lung metastatic nodules of all sizes were meticulously counted, and those with a diameter greater than 1 mm were defined as large nodules. Lung tissues were further stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) for further observation of metastatic lesions. Serum samples were also collected to assess the biosafety of the treatment.

2.16. Analysis of CSCs fractions within the tumors

Encouraged by the remarkable combined treatment effect of RM@St and GM@SAL, we further measured the elimination of CSCs fractions within the tumors. In this regard, 4T1 tumor-bearing mice underwent the following treatment: (1) PBS; (2) LGM@SAL; (3) GM@SAL; (4) free St + GM@SAL; (5) RM@St + LGM@SAL; (6) RM@St + GM@SAL. Mice were treated on Days 0, 2, 4, 6, and 8 (St dosage: 15 mg/kg and SAL dosage: 5 mg/kg), and the tumors were collected on Day 10 for further analysis. The proportion of CSCs within the tumor was evaluated by quantifying the CD44+/CD24− cell population and the formation of tumor spheres in vitro. The tumors were cut into small pieces and digested with collagenase IV to obtain single-cell suspensions. On the one hand, these cell suspensions were stained with anti-CD44-PE and anti-CD24-FITC antibodies for subsequent flow cytometry analysis. On the other hand, these cells were cultured at 37 °C overnight, allowing the viable cells to adhere. The viable cells were seeded in ultralow attachment plates with the CSCs culture medium to record the tumor spheroid formation assay. Moreover, the tumor tissues were examined by H&E staining, Ki67 and vimentin immunofluorescence staining to investigate the tumor lesions further after treatment.

2.17. Statistical analysis

All data were presented as means ± standard deviations (SD). Statistical differences were assessed using a two-tailed paired Student’s t-test for comparison between two groups. Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 8.0 software and ns: no significance, ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, and ∗∗∗P < 0.001.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Preparation and characterization of RM@St and GM@SAL

First, we synthesized the zwitterionic hyperbranched polycarbonates (hPCCB, 50% zwitterion units) and acryloyl-functionalized zwitterionic hyperbranched polycarbonates (hPCCB-AC, 50% zwitterion units and 15% acrylate units) as amphiphilic polymer backbones through a one-pot sequential Michael-type addition reaction and ring-opening polymerization, following our previously established methodology34. Subsequently, acryloxyethyl oxalyl monochloride as a ROS-sensitive linker and N,N′-bis(acryloyl)cystamine as a GSH-sensitive linker were respectively grafted onto the hyperbranched zwitterionic polycarbonates to obtain the desired products of hPCCB-oxa-AC and hPCCB-SS-AC (Supporting Information Fig. S1). 1H NMR clearly showed 10% oxa-AC units in hPCCB-oxa-AC and 10% SS-AC units in hPCCB-SS-AC (Supporting Information Figs. S2 and S3).

ROS responsive zwitterionic micelles (denoted RM) and GSH responsive zwitterionic micelles (denoted GM) were prepared by directly dispersing hPCCB-oxa-AC or hPCCB-SS-AC polymers in PBS, followed by UV cross-linking. Dynamic light scattering (DLS) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM) results revealed that RM and GM exhibited similar diameters of 9.0 nm and featured negatively charged surfaces (Fig. 2A‒C). To explore the impact of nanomedicine size in vascular normalization combination therapy, large-sized GSH-responsive zwitterionic micelles (denoted LGM) as a reference were prepared via nanoprecipitation, featuring a diameter of 142 nm (Fig. 2A). The turbidity of these micelles in 10% FBS solution remained virtually unchanged within 24 h, indicating good colloidal stability of RM, GM and LGM by UV-crosslinking against protein adsorption (Fig. 2D). Furthermore, RM maintained a similar size distribution upon 100-fold dilution (Fig. 2E), suggesting an excellent ability to resist heavy blood dilution after intravenous injection. Colloidal stability was further conducted using H2O2 (50 μmol/L) and GSH (10 mmol/L) to mimic conditions resembling the extracellular oxidation and intracellular reduction in TME36,37. After exposure to H2O2, RM exhibited a remarkable size reduction from 9.6 nm to 0.8 nm upon dilution (Fig. 2E), attributed to the ROS-triggered degradation of oxalate linkages that destroyed the stable cross-linking structure of RM, inducing the disassembly of the nanoparticles upon dilution (Supporting Information Fig. S4A). Similarly, the GSH-triggered degradation of disulfide linkage was also confirmed by the disappearance of acryloyl signals (Fig. S4B), and the colloidal stability of GM was destabilized upon exposure to GSH, favoring subsequent drug release (Supporting Information Fig. S5).

Figure 2.

Characterization of twin-micelles. (A) Hydrodynamic sizes, (B) TEM image, and (C) Zeta potential of RM, LGM and GM (n = 3). (D) Stability of micelles in 10% FBS solution evaluated by turbidity (n = 3). (E) Size change of RM against 50 μmol/L H2O2 conditions. (F) Schematic illustration of drug release by RM@St and GM@SAL. (G) Release profiles of St from RM@St and (H) SAL from GM@SAL in simulated tumor extracellular matrix oxidative and tumor intracellular reductive environments (n = 3), respectively. (I) Hemolytic potential of RM, LGM and GM samples (n = 3). Triton X-100 solution and normal saline as the positive control and negative control, respectively. (J) Pharmacokinetics profiles of Cy5-labeled RM and GM in healthy mice (n = 3). (K) Fluorescence images of ex vivo blood at 2 and 6 h postinjection. Data are presented as mean ± SD.

Sunitinib (St) and salinomycin (SAL) were separately encapsulated within blank twin-like micelles through hydrophobic interactions at a theoretical DLC of 10 wt %, yielding RM@St or GM@SAL. Both formulations exhibited DLE exceeding 75%. The drug release schematic in the tumor extracellular matrix and the intracellular environment was illustrated (Fig. 2F). The cumulative St release of RM@St was about 68% after being treated with H2O2 for 24 h, while St leakage remained below 30% under physiological conditions without H2O2 (Fig. 2G). Likewise, compared with less than 20% of cumulative SAL release in the absence of GSH, more than 70% of SAL exuded from GM@SAL within 24 h incubation under simulated reducing conditions in tumor intracellular (Fig. 2H). These results suggested that RM@St and GM@SAL have the potential to reduce drug leakage during blood circulation and achieve triggered extracellular St release and intracellular SAL release, which would maximize the activities of those two drugs and avoid their adverse effects. Subsequently, in the hemolysis assay, all micelle samples showed negligible hemolysis (<1%) and had excellent blood compatibility (Fig. 2I). After intravenous injection, RM and GM, with identical sizes and zwitterionic surfaces, displayed similar pharmacokinetic profiles (Fig. 2J), further confirming their twin-like properties. Blood samples from mice injected with RM or GM exhibited significantly stronger fluorescence than free Cy5 (Fig. 2K), which facilitates improved tumor delivery of the drug. The delivery of multiple drugs with distinct sites of action was achieved by a meticulously designed nanosystem (i.e., all-in-one)38, which could be more effectively accomplished by twin-like RM and GM requiring less tedious nanoconstruction39,40.

3.2. In vitro CSCs elimination performance of GM@SAL

The cancer stem cells (CSCs)-enriched 3D tumorspheres were cultivated using highly metastatic 4T1 breast cancer cells in an ultra-low attachment plate with a specialized CSCs medium. This approach yielded 3D tumorspheres displaying smooth surfaces (Fig. 3A). Flow cytometry analysis revealed that the CD44+CD24− cell population in parent 4T1 cells constituted only 7.1%. In contrast, this proportion experienced a substantial increase, reaching 58.2%, in 3D tumorspheres (Fig. 3B). 3D tumorsphere cells exhibited higher intracellular GSH concentration and tumorigenic potential compared to parent 4T1 cells (Supporting Information Figs. S6 and S7). The tumorigenic rate in mice injected with 3D tumorspheres reached 80%, surpassing the tumorigenic rate of 20% observed in mice injected with parental 4T1 cells (Fig. 3C). Therefore, compared to parent 4T1 cells, CSCs were significantly enriched in the 3D tumorsphere model. SAL, an ionophore antibiotic, is reported to inhibit Wingless-related integration site (Wnt) signaling and eliminate CSCs by sequestering iron in lysosomes41,42. The cell proliferation assay revealed dose-dependent cytotoxicity of SAL formulations against both 4T1 cells and CSCs (Fig. 3D). Notely, the IC50 value of free SAL in CSCs (2.44 μmol/L) was obviously lower than that in 4T1 cells (6.04 μmol/L) (Fig. 3E), implying a preference for SAL for eliminating CSCs. GM@SAL and LGM@SAL exhibited slightly higher IC50 values than free SAL in CSCs, 3.74 and 4.60 μmol/L, respectively, attributable to efficient SAL release in the tumor intracellular GSH environment.

Figure 3.

In vitro CSCs elimination performance of GM@SAL. (A) Representative images, (B) the expression level of CD24 and CD44 and (C) the in vivo tumorigenicity of 4T1 cells and CSCs spheres. Scale bar: 200 μm. (D) Cell survival of 4T1 cells and CSCs treated with SAL formulations for 48 h. (E) The IC50 values of SAL formulations in 4T1 cells and CSCs (n = 3). (F) Z-stack CLSM images of CSCs tumorspheres incubated with GM-Cy5 and LGM-Cy5 for 12 h. Scale bar: 100 μm. (G) Fluorescence intensity distribution of CSCs tumorspheres at 65 μm depth along the yellow line. (H) Image of the destructive effect of CSCs tumorspheres at different time points incubated with GM@SAL and LGM@SAL. Scale bar: 200 μm. (I) Quantitative analysis of tumor sphere size in (H). Data are presented as mean ± SD. ∗∗P < 0.01.

The tumor penetration ability of GM and LGM was investigated using compact CSCs spheres as a model in vitro. Confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) results demonstrated a relatively uniform distribution of red fluorescence from GM at a scanning depth of 25-45 μm (Fig. 3F). In contrast, the fluorescence from LGM was predominantly concentrated at the edges. Quantitative fluorescence analysis at a scanning depth of 65 μm displayed significantly higher internal fluorescence intensity for GM than LGM (Fig. 3G). The robust penetration of small-sized GM endowed them with a higher likelihood of accessing more cancer cells, promoting cell internalization and enhancing cell-killing efficacy. As anticipated, GM@SAL demonstrated more effective destruction of CSCs spheres (Fig. 3H). At the end of treatment, the relative area of tumor spheres treated with GM@SAL was only 31%, considerably lower than the 70% observed in LGM@SAL-treated spheres (Fig. 3I).

3.3. Tumor vascular normalization effects of RM@St

Endothelial cell migration plays a pivotal aspect in vascular budding during angiogenesis. In the wound healing assay, migrating endothelial cells occupied 53.6% of the scraped area in the untreated control group 48 h after manually scraping (Fig. 4A). It was found that the St formulation significantly curtailed the migration of endothelial cells toward the center of the scratch. The migration rate was 1.8-fold lower for endothelial cells treated with H2O2-preconditioned RM@St than untreated RM@St (Fig. 4B), indicating that the enhanced inhibition was attributed to H2O2-triggered St release. In the Transwell assay, all St formulations effectively reduced the migration of starved HUVEC to the undersurface of the membrane, and the inhibition effect of RM@St was augmented by pretreatment with H2O2 (Fig. 4C and D). A pivotal precursor for angiogenesis is the capacity of endothelial cells to orchestrate the formation of capillary-like tubule structures. Compared with the well-defined lumen structure in the control group, HUVEC exhibited a scattered state with significantly reduced branch length after St formulation treatment (Fig. 4E and F). RM@St displayed robust anti-angiogenic potential in vitro, further amplified in the ROS-abundant environments of TME.

Figure 4.

In vitro anti-angiogenic ability of RM@St. (A) The wound image of HUVECs treated by RM@St with or without pretreatment by H2O2 for 4 h. Scale bar: 200 μm. (B) Quantitative analysis of wound healing percentage (n = 3). (C) The effect of RM@St on the migration ability of HUVECs. Scale bar: 50 μm. (D) The counts of migration cells per field (n = 5). (E) The inhibition of RM@St on the tube formation ability of HUVECs. Scale bar: 200 μm. (F) Quantitative analysis of total length per field (n = 3). (G) The representative images of CD31 (red) and α-SMA (green) staining for endothelial cells and pericytes in tumors after treatment with free St at different doses. Scale bar: 50 μm. (H) Pericyte coverage on tumor blood vessels (n = 3). Data are presented as mean ± SD. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001.

Appropriate doses of antiangiogenic therapy could prune immature tumor vessels to induce tumor vessel normalization43,44. Intravenous administration of different doses of St (5, 15 and 25 mg/kg) to mice effectively reduced intratumoral vascular density, with the degree of intratumoral angiogenesis inhibition increasing with higher doses (Supporting Information Fig. S8). Furthermore, tumor sections underwent double-staining using tumor endothelial cell marker CD31 (red) and pericyte marker α-SMA (green) to evaluate tumor vessel morphology. The pericyte coverage of tumor vessels in all St-treated mice significantly improved relative to the control group, suggesting that St was able to constitutively remodel the tumor vascular structure (Fig. 4G and H). Two-photon imaging also revealed that tumors in untreated mice displayed numerous small, tortuous, and disorganized blood vessels, whereas after St treatment, the tortuosity of tumor blood vessels decreased and vessel morphology became more normalized (Supporting Information Fig. S9A and B). The medium dose (15 mg/kg) showed excellent effects in reducing microvessel density, recruiting pericytes, and remodeling vascular morphology, which was also chosen as the optimal dose for tumor vessel normalization.

The window of vascular normalization is often brief and accompanied by a sustained inhibitory effect of antivascular, leading to a renewed reduction in the number of functional vessels. The highest pericyte coverage during RM@St treatment appeared on Day 6 and gradually decreased on Days 8 and 10, though it remained significantly higher than that of the control and free St groups (Fig. 5A and B). In contrast, the pericyte coverage in the free St group on Day 10 resembled that of the control group, indicating the end of vessel normalization. RM@St effectively promoted the maturation of tumor vessels and prolonged vessel normalization window, possibly owing to the small-sized RM@St responding to tumor interstitial fluid pressure (IFP) to alter its intratumoral distribution. On the Day 0 of vascular normalization treatment, the red fluorescence signal of RM@St was primarily concentrated within 40 μm around tumor blood vessels due to the restricted penetration caused by the high tumor IFP (Fig. 5C and D). This accumulation facilitated the inhibition of angiogenesis and the pruning of immature vessels. By the 6th day of treatment, along with the decrease in IPF during the vascular normalization window, the red fluorescence signal of RM@St was distributed more uniformly within the tumor rather than concentrated near blood vessels, still observable up to 100 μm away from the vessels, resulting in an appropriate concentration of RM@St near the vessels to avoid excessive vascular reduction (Supporting Information Fig. S10). These findings highlighted the potential of ROS-sensitive small-sized RM@St to adjust the required dosage of antiangiogenic drugs intelligently, enhancing vascular normalization and benefiting the effectiveness of combination therapies with vascular normalization.

Figure 5.

In vivo tumor vascular normalization efficacy of RM@St. (A) The representative images of CD31 (red) and α-SMA (green) staining for endothelial cells and pericytes in tumors on Days 4, 6, 8, and 10 after treatment with RM@St or free St. Scale bar: 50 μm. (B) Quantitative analysis of the pericyte coverage on tumor blood vessels (n = 3). (C) The intratumoral distribution of RM@St, wherein the blood vessel was stained with CD31 (green: blood vessel; red: RM@St, Scale bar: 50 μm). (D) Schematic illustration of the intratumoral distribution of RM@St in vascular normalization therapy. Data are presented as mean ± SD. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001, ns: not significance.

3.4. Impact of vascular normalization on intratumor delivery of GM@SAL

Efficient accumulation and deep penetration of chemotherapeutic agents in the tumor are conducive to improving CSCs accessibility as a prerequisite for achieving CSCs killing. Given the promising efficacy of RM@St in normalizing tumor vessels, we assessed the impact of RM@St treatment on tumor accumulation, intratumor penetration and CSCs accessibility of GM@SAL. Tumor-bearing mice were injected intravenously with Cy5 labeled GM or large-sized LGM for fluorescent imaging. In vivo results showed the fluorescence signal of GM and LGM was clearly visible in the tumor region (Fig. 6A). Notably, when tumor-bearing mice were pretreated with RM@St to achieve vascular normalization, the fluorescence intensity of GM in the tumor region markedly increased. However, the fluorescence signal of LGM in the tumor region remained nearly unchanged in the comparison, regardless of whether the tumor mice had received RM@St pretreatment. Ex vivo imaging of tumors and semi-quantitative analysis distinctly revealed a 1.6-fold increase in fluorescence intensity of GM in the RM@St pretreatment group compared to the untreated group (Fig. 6B), demonstrating improved tumor accumulation. The RM@St treatment effectively improved the tumor accumulation of small-sized GM but did not affect large-sized LGM. This difference could be attributed to larger nanoparticles, whose diameter comes close to the size of the average pore of a normalized vessel, experiencing steric and hydrodynamic hindrances that impede transport. However, small nanoparticles can still pass smoothly through the pores of normalization vessels and benefit from the increased blood perfusion and transvascular driving force induced by vascular normalization, thereby enhancing the tumor transport efficiency of small-sized nanoparticles. Subsequently, tumor sections were separately stained with CD31 and ALDH1 (a CSC marker) to investigate tumor penetration and CSCs accessibility of GM and LGM. Without RM@St pretreatment, the fluorescence signal of GM, while detectable outside the vessels, was primarily distributed in the perivascular region (Fig. 6C), possibly due to the high IFP in the tumor. Following vascular normalization induced by RM@St pretreatment, GM considerably permeated the tumor tissues away from the blood vessels with more vigorous fluorescence intensity. Regardless of whether received RM@St pretreatment, the fluorescent signals of LGM were mainly concentrated near blood vessels, with some signals even colocalization with blood vessels, likely due to the small openings of the ECM hindering the diffusion of large nanoparticles. In the accessibility of CSCs, the dense red fluorescence signals of GM in the RM@St pretreatment group were detected in the vicinity of CSCs and partially colocated with the green signals of ALDH1 of CSCs markers (Fig. 6D), showing efficient CSCs accessibility. Generally, vascular normalization through RM@St pretreatment could improve the tumor accumulation and penetration of small-sized GM, leading to higher drug concentrations near CSCs and demonstrating great potential for achieving combined therapeutic effects.

Figure 6.

Impact of vascular normalization on intratumor delivery of GM@SAL. (A) Tumor accumulation of Cy5-labeled GM and LGM in tumor models of vascular normalization induced by RM@St and ex vivo fluorescence imaging of tumors 24 h postinjection. (B) Semi-quantitative fluorescence analysis of excised tumors (n = 3). (C) The penetration of GM or LGM in the tumor tissue, wherein the blood vessel was stained with CD31 (green: blood vessel; red: micelles, scale bar: 100 μm). (D) The in vivo accessibility of GM or LGM to ALDHhigh CSCs in tumor tissue, wherein the CSCs was stained with ALDH1 (green: CSCs; red: micelles, scale bar: 50 μm). Data are presented as mean ± SD. ∗P < 0.05, ns: not significance.

3.5. Suppression efficacy on tumor progression and lung metastasis

Inspired by the remarkable efficacy of RM@St treatment in promoting the tumor accumulation, interstitial permeation and CSCs accessibility of GM, we evaluated the anticancer and antimetastatic effects of RM@St plus GM@SAL combination strategy in 4T1 breast cancer models (Fig. 7A). In the tumor growth profiles, free St and RM@St monotherapies induced only slight tumor growth inhibition, with inhibitory rate of 17.2% and 24.6% compared to the negative control, suggesting their primary role in vascular normalization rather than direct tumor suppression via vessel pruning for starvation therapy (Fig. 7B and Supporting Information Fig. S11A). Similarly, free SAL, LGM@SAL and GM@SAL monotherapies led to a modest inhibition of tumor progression. However, combining RM@St with GM@SAL notably retarded tumor growth, achieving a suppression rate of 66.7%, significantly higher than that of RM@St or GM@SAL monotherapy and even free St combined with GM@SAL. This result was attributed to the more increased and sustained vascular normalization effect induced by RM@St, which effectively enhanced GM@SAL delivery. Although the combination of vascular normalization therapy also improved the tumor suppression effect of free SAL, it was still significantly inferior to RM@St + GM@SAL treatment. Notably, when RM@St or free St was combined with LGM@SAL, tumor suppression was not improved compared to LGM@SAL monotherapy, which was consistent with tumor accumulation and penetration findings. Isolated tumor images and weights further confirm the optimal tumor inhibitory efficacy of the RM@St + GM@SAL treatment (Fig. 7C and D). In addition, a slight upward trend in body weight was observed in all groups, indicating treatment safety (Fig. S11B). There was no difference in the serum levels of liver and kidney function markers (ALT, AST, BUN, and CREA) in the RM@St + GM@SAL group of mice compared to those injected with PBS, suggesting no apparent liver and kidney damage caused by this combination therapy (Supporting Information Fig. S12). H&E staining also revealed no significant pathological changes, including injury or inflammation, in the major organs of mice treated with RM@St + GM@SAL (Supporting Information Fig. S13).

Figure 7.

In vivo antitumor and metastasis inhibition of RM@St and GM@SAL combination therapy. (A) Schematic illustration of treatment schedule in mice bearing 4T1 tumors. (B) The individual tumor growth curves from each group. The black dashed line represented the average tumor volume of mice treated with RM@St + GM@SAL on Day 24. (C) The ex vivo tumor image and (D) the tumor weight of each group on Day 24 post-treatment. (E) Representative images of Bouin’s buffer-treated lungs (metastatic nodules were marked with black arrows). (F) Numbers of the pulmonary metastatic nodules (n = 6). Data are presented as mean ± SD. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001, ns: not significance.

Lung metastasis is a challenging issue in breast cancer treatment, with poor prognosis despite extensive therapy. After lung tissue fixation with Bouin’s buffer, metastatic nodules, indicated by arrows, were clearly visible in untreated mice (Fig. 7E). Treatment with GM@SAL and LGM@SAL individually moderately inhibited lung metastasis, resulting in inhibitory rates of 33.7% and 29.6% compared to the control (Fig. 7F), respectively. However, when combined with vascular normalization therapy, RM@St + GM@SAL treatment significantly enhanced the inhibition of lung metastasis, achieving an inhibition rate of 78.4% compared to RM@St + free SAL group (44.2%) and RM@St + LGM@SAL group (39.7%). RM@St + GM@SAL treatment also led to fewer metastatic nodules than free St + GM@SAL, which was attributed to RM@St’s better vascular integrity and duration improvement. Additionally, the size of lung nodules is also an indicator of lung metastasis inhibition. Compared to an average of 15 large metastatic nodules (diameter >1 mm) in untreated mice, the number of large nodules significantly decreased after RM@St + GM@SAL treatment, with an average of only 0.7 large metastatic nodules per mouse. The lung sections were stained with H&E to evaluate the efficient suppression of lung metastasis further. Large metastatic foci were visible in the magnified lung tissue images from all groups except for the RM@St + GM@SAL groups (Supporting Information Fig. S14), confirming its superior efficacy in metastasis suppression.

To elucidate the mechanisms underlying the antitumor efficacy and tumor metastasis inhibitory of RM@St + GM@SAL, the proportions of CSCs within tumor masses were examined at the end of the antitumor study (Fig. 8A). The RM@St + GM@SAL treatment exhibited the lowest proportion of CD24−CD44+ CSCs (Fig. 8B and D) and the fewest tumorspheres (Fig. 8C and E). The proportion of CD24−CD44+ CSCs decreased from 18.2% with GM@SAL treatment to 12.9% with free St + GM@SAL treatment and further to 6.8% with RM@St + GM@SAL treatment, which can be attributed to vascular normalization enhancing the tumor accumulation, interstitial penetration and CSCs accessibility of small-sized GM@SAL. CSCs were responsible for recurrence and metastasis and were recognized as the primary cells capable of establishing metastatic tumors in distant organs18. The administration of RM@St + GM@SAL effectively eradicated CSCs, reducing the likelihood of lung metastasis, which aligned with the changes observed in the number of lung metastatic nodules following treatment. However, no significant alteration in CSCs elimination ability was observed in the LGM@SAL and RM@St + LGM@SAL comparisons, underscoring the importance of small-sized nanomedicine in combination with vessel normalization.

Figure 8.

Ability of RM@St and GM@SAL combination therapy to eradicate CSCs. (A) Schematic illustration of treatment in mice. (B) Representative images of flow cytometric analysis on CD24−CD44+ cells in tumors and (C) tumor spheroids formed by tumor cells from orthotopic tumor tissues at day 10 post-treatment. Scale bar: 300 μm. (D) The proportion of CD24−CD44+ cells in tumors (n = 3). (E) The relative percentage of tumor spheroid formation (n = 3). (F) H&E and Ki67 staining of excised tumors on Day 10 post-treatment. Scale bar: 100 μm. (G) Semi-quantitative fluorescence analysis of positive Ki67 cells of tumors. Data are presented as mean ± SD. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001, ns: not significance.

Histological and immunofluorescence analyses were also performed on the excised tumor blocks. These analyses revealed extensive tumor cell death and more vacancies in H&E staining slices in response to RM@St and GM@SAL combination therapy (Fig. 8F). Additionally, minimal Ki67-positive and Vimentin-positive cells were observed in tumor tissue treated with RM@St and GM@SAL (Fig. 8G and Supporting Information Fig. S15), indicating that this combination therapy prominently reduced the proliferation and migration ability of tumor cells, consistent with the tumor growth curves and lung metastasis results.

4. Conclusions

In summary, a pair of twin-like small-sized RM@St with ROS response and GM@SAL with GSH response were successfully synthesized to normalize disordered tumor vessels, improving intratumor delivery and eradication of CSCs. Compared to free drugs, RM@St exhibited significantly superior prolonged circulation time and accelerated drug release under the TME, effectively inhibiting angiogenic and normalizing tumor vasculature while extending the vessel normalization window by supplying antiangiogenic drugs on demand. Furthermore, RM@St-induced vascular normalization notably enhanced tumor accumulation, deep penetration and CSCs accessibility of small-sized GM@SAL. As a result of those effects, the combined therapy of RM@St plus GM@SAL successfully reduced the proportions of CSCs within tumor masses, which in turn inhibited tumor growth and lung metastasis, achieving excellent in vivo antitumor therapeutic outcomes. Overall, our study highlights that combining tumor vasculature remodeling strategy with nanoparticle size design can improve the delivery of small nanoparticles into solid tumors, leading to enhanced eradication of CSCs.

Author contributions

Changshun Zhao: Visualization, Software, Methodology, Funding acquisition, Data curation, Writing – original draft, Validation, Project administration, Investigation, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Wei Wang: Methodology, Software. Zhengchun Huang: Data curation, Software. Yuqing Wan: Software, Conceptualization, Methodology. Rui Xu: Methodology, Visualization, Investigation. Junmei Zhang: Software, Investigation, Methodology. Bingbing Zhao: Supervision, Funding acquisition. Ke Wang: Methodology, Investigation. Suchen Wen: Resources, Software, Methodology. Yinan Zhong: Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition, Supervision. Dechun Huang: Supervision, Funding acquisition. Wei Chen: Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Conceptualization.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC52173294 and 52273162), Demonstration Project of Modern Agricultural Machinery Equipment & Technology in Jiangsu Province (NJ2022-11, China), Jiangsu Funding Program for Excellent Postdoctoral Talent (2023ZB585, China), Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (2632023FY03, China), Postgraduate Research & Practice Innovation Program of Jiangsu Province (KYCX23_0883, China).

Footnotes

Peer review under the responsibility of Chinese Pharmaceutical Association and Institute of Materia Medica, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences.

Supporting information to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsb.2025.08.001.

Contributor Information

Bingbing Zhao, Email: zhaobb@cpu.edu.cn.

Dechun Huang, Email: cpuhdc@cpu.edu.cn.

Wei Chen, Email: w.chen@cpu.edu.cn.

Appendix A. Supporting information

The following is the Supporting Information to this article:

References

- 1.Fang J., Islam W., Maeda H. Exploiting the dynamics of the EPR effect and strategies to improve the therapeutic effects of nanomedicines by using EPR effect enhancers. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2020;157:142–160. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2020.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.De Lázaro I., Mooney D.J. Obstacles and opportunities in a forward vision for cancer nanomedicine. Nat Mater. 2021;20:1469–1479. doi: 10.1038/s41563-021-01047-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ikeda-Imafuku M., Wang L.L., Rodrigues D., Shaha S., Zhao Z., Mitragotri S. Strategies to improve the EPR effect: a mechanistic perspective and clinical translation. J Control Release. 2022;345:512–536. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2022.03.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heath V.L., Bicknell R. Anticancer strategies involving the vasculature. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2009;6:395–404. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2009.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu Z.L., Chen H.H., Zheng L.L., Sun L.P., Shi L. Angiogenic signaling pathways and anti-angiogenic therapy for cancer. Signal Transduct Targeted Ther. 2023;8:198. doi: 10.1038/s41392-023-01460-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hanahan D., Weinberg R.A. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Apte R.S., Chen D.S., Ferrara N. VEGF in signaling and disease: beyond discovery and development. Cell. 2019;176:1248–1264. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Golombek S.K., May J.N., Theek B., Appold L., Drude N., Kiessling F., et al. Tumor targeting via EPR: strategies to enhance patient responses. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2018;130:17–38. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2018.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jain R.K. Normalization of tumor vasculature: an emerging concept in antiangiogenic therapy. Science. 2005;307:58–62. doi: 10.1126/science.1104819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jain R.K., Stylianopoulos T. Delivering nanomedicine to solid tumors. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2010;7:653–664. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2010.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nia H.T., Munn L.L., Jain R.K. Physical traits of cancer. Science. 2020;370 doi: 10.1126/science.aaz0868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Martin J.D., Seano G., Jain R.K. Normalizing function of tumor vessels: progress, opportunities, and challenges. Annu Rev Physiol. 2019;81:505–534. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-020518-114700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pei S.N., Liao C.K., Chen Y.S., Tseng C.H., Hung C.M., Chiu C.C., et al. A novel combination of bevacizumab with chemotherapy improves therapeutic effects for advanced biliary tract cancer: a retrospective, observational study. Cancers. 2021;13:3831. doi: 10.3390/cancers13153831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Avallone A., Piccirillo M.C., Nasti G., Rosati G., Carlomagno C., Di Gennaro E., et al. Effect of bevacizumab in combination with standard oxaliplatin-based regimens in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.18475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chauhan V.P., Stylianopoulos T., Martin J.D., Popović Z., Chen O., Kamoun W.S., et al. Normalization of tumour blood vessels improves the delivery of nanomedicines in a size-dependent manner. Nat Nanotechnol. 2012;7:383–388. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2012.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jiang W., Huang Y., An Y., Kim B.Y. Remodeling tumor vasculature to enhance delivery of intermediate-sized nanoparticles. ACS Nano. 2015;9:8689–8696. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.5b02028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang B., Shi W., Jiang T., Wang L., Mei H., Lu H., et al. Optimization of the tumor microenvironment and nanomedicine properties simultaneously to improve tumor therapy. Oncotarget. 2016;7:62607–62618. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.11546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nassar D., Blanpain C. Cancer stem cells: basic concepts and therapeutic implications. Annu Rev Pathol. 2016;11:47–76. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-012615-044438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lytle N.K., Barber A.G., Reya T. Stem cell fate in cancer growth, progression and therapy resistance. Nat Rev Cancer. 2018;18:669–680. doi: 10.1038/s41568-018-0056-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gu W., Qu R., Meng F., Cornelissen J., Zhong Z. Polymeric nanomedicines targeting hematological malignancies. J Control Release. 2021;337:571–588. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2021.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Han J., Won M., Kim J.H., Jung E., Min K., Jangili P., et al. Cancer stem cell-targeted bio-imaging and chemotherapeutic perspective. Chem Soc Rev. 2020;49:7856–7878. doi: 10.1039/d0cs00379d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yu L.Y., Shueng P.W., Chiu H.C., Yen Y.W., Kuo T.Y., Li C.R., et al. Glucose transporter 1-mediated transcytosis of glucosamine-labeled liposomal ceramide targets hypoxia niches and cancer stem cells to enhance therapeutic efficacy. ACS Nano. 2023;17:13158–13175. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.2c12123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Plaks V., Kong N., Werb Z. The cancer stem cell niche: how essential is the niche in regulating stemness of tumor cells? Cell Stem Cell. 2015;16:225–238. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2015.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kirtane A.R., Kalscheuer S.M., Panyam J. Exploiting nanotechnology to overcome tumor drug resistance: challenges and opportunities. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2013;65:1731–1747. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2013.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zuo Z., Chen K., Yu X., Zhao G., Shen S., Cao Z., et al. Promoting tumor penetration of nanoparticles for cancer stem cell therapy by TGF-β signaling pathway inhibition. Biomaterials. 2016;82:48–59. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2015.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Han H., Hou Y., Chen X., Zhang P., Kang M., Jin Q., et al. Metformin-induced stromal depletion to enhance the penetration of gemcitabine-loaded magnetic nanoparticles for pancreatic cancer targeted therapy. J Am Chem Soc. 2020;142:4944–4954. doi: 10.1021/jacs.0c00650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Relation T., Dominici M., Horwitz E.M. Concise review: an (im)penetrable shield: how the tumor microenvironment protects cancer stem cells. Stem Cell. 2017;35:1123–1130. doi: 10.1002/stem.2596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cao J., Du X., Zhao H., Zhu C., Li C., Zhang X., et al. Sequentially degradable hydrogel-microsphere loaded with doxorubicin and pioglitazone synergistically inhibits cancer stemness of osteosarcoma. Biomed Pharmacother. 2023;165 doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2023.115096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xu F., Huang X., Wang Y., Zhou S. A size-changeable collagenase-modified nanoscavenger for increasing penetration and retention of nanomedicine in deep tumor tissue. Adv Mater. 2020;32 doi: 10.1002/adma.201906745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wu Y., Xie H., Li Y., Bao X., Lu G.L., Wen J., et al. Nitric oxide-loaded bioinspired lipoprotein normalizes tumor vessels to improve intratumor delivery and chemotherapy of albumin-bound paclitaxel nanoparticles. Nano Lett. 2023;23:939–947. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.2c04312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu X., Ye N., Xiao C., Wang X., Li S., Deng Y., et al. Hyperbaric oxygen regulates tumor microenvironment and boosts commercialized nanomedicine delivery for potent eradication of cancer stem-like cells. Nano Today. 2021;40 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang X., Ye N., Xu C., Xiao C., Zhang Z., Deng Q., et al. Hyperbaric oxygen regulates tumor mechanics and augments abraxane and gemcitabine antitumor effects against pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma by inhibiting cancer-associated fibroblasts. Nano Today. 2022;44 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tan T., Wang H., Cao H., Zeng L., Wang Y., Wang Z., et al. Deep tumor-penetrated nanocages improve accessibility to cancer stem cells for photothermal-chemotherapy of breast cancer metastasis. Adv Sci. 2018;5 doi: 10.1002/advs.201801012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhao C., Wen S., Pan J., Wang K., Ji Y., Huang D., et al. Robust construction of supersmall zwitterionic micelles based on hyperbranched polycarbonates mediates high tumor accumulation. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2023;15:2725–2736. doi: 10.1021/acsami.2c20056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shen S., Xu X., Lin S., Zhang Y., Liu H., Zhang C., et al. A nanotherapeutic strategy to overcome chemotherapeutic resistance of cancer stem-like cells. Nat Nanotechnol. 2021;16:104–113. doi: 10.1038/s41565-020-00793-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhong Y., Zhang J., Zhang J., Hou Y., Chen E., Huang D., et al. Tumor microenvironment-activatable nanoenzymes for mechanical remodeling of extracellular matrix and enhanced tumor chemotherapy. Adv Funct Mater. 2021;31 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yan W., Guo B., Wang Z., Yang J., Zhong Z., Meng F. RGD-directed 24 nm micellar docetaxel enables elevated tumor-liver ratio, deep tumor penetration and potent suppression of solid tumors. J Control Release. 2023;360:304–315. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2023.06.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hou B., Zhou L., Wang H., Saeed M., Wang D., Xu Z., et al. Engineering stimuli-activatable boolean logic prodrug nanoparticles for combination cancer immunotherapy. Adv Mater. 2020;32 doi: 10.1002/adma.201907210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xu C., Yang S., Jiang Z., Zhou J., Yao J. Self-propelled gemini-like lmwh-scaffold nanodrugs for overall tumor microenvironment manipulation via macrophage reprogramming and vessel normalization. Nano Lett. 2020;20:372–383. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.9b04024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Deng Y., Jiang Z., Jin Y., Qiao J., Yang S., Xiong H., et al. Reinforcing vascular normalization therapy with a bi-directional nano-system to achieve therapeutic-friendly tumor microenvironment. J Control Release. 2021;340:87–101. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2021.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lu D., Choi M.Y., Yu J., Castro J.E., Kipps T.J., Carson D.A. Salinomycin inhibits wnt signaling and selectively induces apoptosis in chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:13253–13257. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1110431108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mai T.T., Hamaï A., Hienzsch A., Cañeque T., Müller S., Wicinski J., et al. Salinomycin kills cancer stem cells by sequestering iron in lysosomes. Nat Chem. 2017;9:1025–1033. doi: 10.1038/nchem.2778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jiang Z., Xiong H., Yang S., Lu Y., Deng Y., Yao J., et al. Jet-lagged nanoparticles enhanced immunotherapy efficiency through synergistic reconstruction of tumor microenvironment and normalized tumor vasculature. Adv Healthcare Mater. 2020;9 doi: 10.1002/adhm.202000075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Huang Y., Yuan J., Righi E., Kamoun W.S., Ancukiewicz M., Nezivar J., et al. Vascular normalizing doses of antiangiogenic treatment reprogram the immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment and enhance immunotherapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:17561–17566. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1215397109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.