Abstract

Background

Antiretroviral therapy suppresses human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) replication; however, nearly 50% of HIV infected patients suffer from HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders (HAND). Recently, we reported that proteins in plasma circulating extracellular vesicles (EVs) of either simian human immunodeficiency virus (SHIV) infected rhesus macaques (RMs) or HIV-infected patients show a link to neuropathogenesis. In this study, we show that proteins in circulating EVs of SHIV-infected RMs (SHIV-EVs) were associated with dysregulation of the synaptic signaling pathway.

Methods

Plasma circulating EVs were isolated from SHIV-infected (SHIV-EVs) and uninfected (CTL-EVs) RMs and characterized by the ZetaView analyzer (n = 5/group) and transmission electron microscopy. Several EV-associated markers were detected by western blotting. Proteomic analysis of the isolated EVs (n = 3/group) was performed using liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry. Using ingenuity pathway analysis (IPA), the differentially expressed proteins (DEPs) involved in the dysregulation of different synaptic signaling pathways were assessed.

Results

Interestingly, proteins in SHIV-EVs were involved in synaptogenesis signaling deactivation, synaptic long-term potentiation/depression, and glutamate receptor signaling, as well as activation of semaphorin neuronal repulsive signaling pathways. Intriguingly, we observed that several proteins, which are involved in synaptic vesicle (SV) assembly and SV fusion, were abundantly under-expressed in SHIV-EVs compared with EVs of uninfected RMs. Dysregulated proteins in SHIV-EVs show possible deactivation of (a) SV priming, docking, and fusion in presynaptic neurons; and (b) synaptic spine development/density and synapse stabilization in postsynaptic neurons. Conversely, the activation of semaphorin neuronal repulsive signaling pathway in SHIV-EVs showed possible activation of cytoskeleton contraction/rearrangement, microtubule stabilization, and action repulsion, as well as deactivation of microtubule polymerization and action generation/outgrowth in SHIV-infected RMs. Dysregulated synaptic signaling-related proteins in SHIV-EVs were involved in several neuropathology-related disorders/diseases, including early/progressive neurological disorder, cognitive impairment, degenerative dementia, and Alzheimer’s disease.

Conclusions

Our novel findings suggest that plasma circulating EVs can be a useful noninvasive technique to elucidate the mechanisms involved in the development of central nervous system dysfunction and the progression of neurological diseases such as HAND.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12964-025-02464-w.

Keywords: SHIV, Rhesus macaque, Plasma extracellular vesicles, Proteomic analysis, Synaptic vesicles, Synaptic signaling, Neuropathogenesis

Background

Although efficient combined antiretroviral therapy (cART) has significantly decreased HIV-associated deaths, 20–60% (and sometimes up to 90%) of people living with HIV may progress to HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder (HAND) [1]. Increasingly, data from the scientific literature have linked synaptic abnormalities to various neurodegenerative disorders and diseases [2, 3]. In the early stages of Alzheimer’s disease (AD), there is significantly more synaptic than neuronal loss [4, 5]. Using an AD mouse model, studies have reported that synaptic dysfunction appears in the first phase [6] and synaptic connection disruption then leads to neuronal dysfunction, causing cognitive deficits [7]. The pathological causes of HAND are still under investigation. Recent reports suggest that viral protein, glycoprotein 120, induces synaptic damage and synaptodendritic degradation [8] and reduces glutamate receptor density [9]. Similarly, HIV-Tat protein promotes phosphorylation of N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors [10], downregulates synaptic vesicle-associated proteins [11], and impairs synaptic architecture [12].

Recently, much physiology/pathology research has focused on circulating extracellular vesicles (EVs) due to their ability to package and deliver payloads (lipids, proteins, or nucleic acids) and their molecular signaling, which enables cell-to-cell communication and tissue homeostasis [13], or to stimulate pathogenesis in numerous diseases [14]. Recent studies showed that EVs originating from the central nervous system (CNS) can cross the blood–brain barrier (BBB) and carry pathologic proteins into the blood [15]. Therefore, serum/plasma-derived EVs from HIV-infected or uninfected patients with neurological disorders/diseases are being examined for promising biomarkers of neuropathogenesis and clinical progression [16–18].

Proteomics, with advanced bioinformatic analysis, has become an important research tool in profiling differentially expressed proteins (DEPs), detection of post-translational modifications, exploration of protein–protein interactions, understanding disease progression, and biomarker discovery, offering multidimensional insights into dynamic physiological and pathological processes in cells or organs [19]. There are several obstacles to molecular signaling-based studies on the rhesus macaque model due to the limited availability of rhesus-specific reagents. Therefore, we conducted a comprehensive proteomic analysis of DEPs in plasma circulating EVs linked to the dysregulation of synaptic signaling and neuropathogenesis in simian/human immunodeficiency virus (SHIV)-infected rhesus macaques (RMs). Our methods provide a much-needed, noninvasive technique to address the development and progression of neuropathogenesis, especially in AIDS patients. In addition, our findings provide a foundation for future research to provide a global view of CSF/brain circulating EVs in physiology as well as in pathology, which gives context and meaning to “big data” or omics experiments.

Materials and methods

Plasma from SHIV-infected and cART-treated rhesus macaques (RMs)

The SHIV infection, combined antiretroviral drug (cARTs) treatment, and the RMs viral load were discussed in our recent publication [20]. Briefly, animals were housed at the Tulane National Primate Research Center (TNPRC) in compliance with the Animal Welfare Act of the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) and the NIH Office of Laboratory Animal Welfare (OLAW). Animals were infected intravenously with the R5/X4 tropic chimeric SHIV-D (50 ng of SIV p27 Gag) virus. After plasma viral load (PVL) reached the viral set point (~ 6 weeks post-infection), RMs were treated daily with antiretroviral drugs for ~ 12 weeks to bring the PVL to undetectable levels. RMs were followed for 86 weeks, and plasma samples were collected at necropsy. Samples were stored at −80 °C until used. Initially, five SHIV-infected and five uninfected control RMs (both male and female) were included in the study for isolation and characterization of plasma circulating EVs. An equal number of plasma EV samples (n = 3/group) from SHIV-infected (SHIV-EVs) and uninfected (CTL-EVs) RMs were randomly selected for the proteomic analysis.

Isolation of plasma circulating EVs

We isolated plasma circulating EVs using the exoEasy Maxi Kit (QIAGEN, 40724 Hilden, Germany, Cat #76064) as presented in our previous publication [20]. Briefly, 4 mL of plasma samples were differentially centrifuged at 500 × g for 5 min, 2000 × g for 10 min, and 10,000 × g for 30 min to remove cells, cellular debris, and large microvesicles, respectively. Plasma was passed through a 0.8 μm syringe filter (Millipore Millex-AA; Cat #SLAAR33SS) and isolated EVs according to the exoEasy Maxi Kit protocol. The isolated EVs protein concentration was measured by BCA protein assay kit (Pierce, Thermo Scientific, USA), and samples were stored at −80 °C until used.

Plasma EVs characterization by ZetaView analyzer

We previously reported the size (nm) and concentration (particles/mL) of isolated SHIV-EVs and CTL-EVs [20]. In this study, we measured zeta potential (mV) of isolated plasma circulating EVs by ZetaView PMX-430-Z QUATT laser system (Particle Metrix, Mebane, NC, USA). Briefly, EVs were diluted in dH2O in an appropriate ratio to maintain the optimal number of particles (between 150 and 350) in the field of view of the camera position. The instrument was calibrated using 100 nm polystyrene beads. Zeta potential control (70325 C, Applied Microspheres, Leusden, The Netherlands) was used as a standard. All measurements were performed in triplicate (with 11 positions being measured in each replicate) under identical settings (room temperature between 20 and 25 °C, pH 7.0, sensitivity 65, shutter speed 100, max Area 1000, min Area 10, min Brightness 20).

Plasma EVs characterization by transmission electron microscopy (TEM)

To prepare the grids for TEM, we used gadolinium acetate tetrahydrate solution, a non-radioactive uranyl acetate substitute, which produces similar staining results to uranyl acetate [21, 22]. Briefly, formvar/carbon-supported copper grids (Ted Pella #0180 formvar/Carbon 200 mesh copper grids) were soaked in ethanol for a minute before placing over a drop (approximately 25 µL) of each sample on parafilm. After the sample incubation period of 10 min, the grids were stained with 25 µL of 2% gadolinium acetate tetrahydrate (Ted Pella #19485) for a minute and washed with water to remove excess stain. The grids were then allowed to dry at room temperature after blotting any excess liquid from the grid edges and stored in a desiccator until examining the next day using a Tecnai G2 200 kV TEM.

Quantitative proteomic analysis

Samples were prepared for discovery-based quantitative proteomic analysis as described previously [23–25]. Briefly, the tandem mass tag (TMT) approach uses isobaric tags to differentiate multiplexed protein extracts using liquid chromatography mass spectrometry (LC-MS). TMT data acquisition utilized an MS3 approach for data collection, where survey scans (MS1) were performed in the Orbitrap utilizing 120,000 resolution. Data-dependent MS2 scans were performed in the linear ion trap using a 25% collision-induced dissociation. Reporter ions were fragmented using a high-energy 55% collision dissociation and detected in the Orbitrap using a resolution of 30,000 (MS3). The LC-MS acquisition data were searched using the SEQUEST HT node of Proteome Discoverer 2.4™ (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The protein FASTA database was Rhesus macaque, SwissProt tax ID = 9544, version 2021-05-24, containing 44,389 sequences.

Selection of high-scoring peptides for the identified proteins

Generally, the confidence level for the identified protein is determined by the false discovery rate (FDR). In the most common workflows, high confidence is associated with an FDR of 1%, which means that high-confidence hits are 99% accurate. In our TMT-based proteomic analysis, the FDR was less than 1%. Additionally, we considered the number of unique peptide(s) detected per quantified protein that has a strict FDR of < 1%. The traditional “two-peptide rule” recommends detecting at least two unique peptides for each protein to assign high confidence. We previously reported that two or more unique peptides were detected in 85% (4777/5654) of quantified proteins, and in 89% (211/236) of significantly differentially expressed proteins [20].

Antibodies

Antibodies were purchased from the following suppliers: against GM130 (#MA5-35107), from Invitrogen Corporation, Fredrick, MD; against albumin (#4929), calnexin (#2679), GRP94 (#2104), Alix (#92880), and TSG101 (#72312), from Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers MA, USA; against lipoprotein a (#NBP2-37477), Novus Biologicals, Centennial, CO, USA.

Western blotting

We followed our previously described standard laboratory protocol for immunoblots for plasma circulating EVs [20]. In brief, ice-cold NP40 with phosphatase and protease inhibitors (Invitrogen, Frederick, MD, USA) was used to lyse the circulating EVs. Proteins were separated in an SDS-PAGE gradient gel (4–20%) and transferred onto a PVDF membrane. Diluted (1X) blocking buffer (Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA) was used to block the non-specific binding sites and to dilute the primary antibodies. Membranes were incubated overnight with primary antibodies (1:1000 dilution) at 4 °C. The next day, membranes were washed and incubated again with respective secondary antibodies (1:2000 dilution for goat anti-rabbit IgG and 1:5000 dilution for goat anti-mouse IgG) at room temperature for 1 h. Chemiluminescence (LumiGLO, Gaithersburg, MD, USA) and autoradiography were used to visualize the final reaction.

Bioinformatic analysis

The effects of SHIV infection on the proteome were determined by comparing the DEPs in circulating SHIV-EVs vs. CTL-EVs. Proteins identified in these two study groups were uploaded to Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) software. Initially, using IPA, the DEPs involved in the dysregulation of different synaptic signaling pathways were assessed. The differential expression of synaptic vesicle (SV)-associated protein in SHIV-EVs and CTL-EVs was compared. The Protein network analysis by IPA demonstrated the abundance (either activated or deactivated) of DEPs and their involvement in different synaptic signaling pathways. Finally, pathway analysis indicated that DEPs in SHIV-EVs may be involved in different neurological disorders/diseases.

Statistical analysis

As we mentioned before [20], only high-scoring peptides were incorporated for proteomic analysis with an FDR of < 1%. Proteome Discoverer was used to determine quantitative differences between infected and uninfected groups, and quantitative data were collected using a t-test analysis (p < 0.05) on grouped biological replicates and performed pair-wise comparisons for fold-change. In several figures, the statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism version 10.5.0 for Windows, and p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Characterization of plasma circulating EVs of SHIV-infected and uninfected RMs

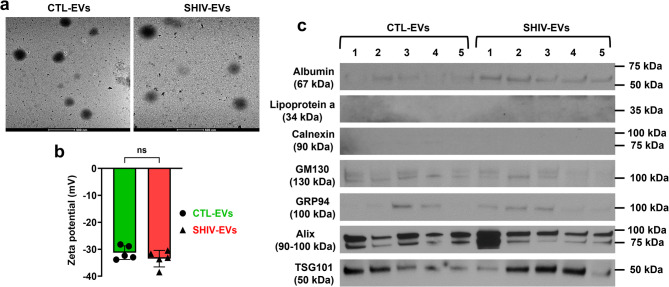

We previously reported that in isolated plasma circulating EVs, the viral load was less than 1.9 Eq. LOG copies in the SHIV-infected samples [20]. By proteomic analysis (n = 3 RMs/group), a total of 5654 DEPs were quantified, of which 2115 (~ 37%) DEPs were higher, and 3456 (~ 61%) DEPs were lower in SHIV-EVs (Fig. 1a). A total of 236 (~ 4%) DEPs were significantly higher in SHIV-EVs compared with CTL-EVs. The volcano plot showed that among the significant proteins, 174 DEPs (~ 74%, 174/236) were lower and 62 DEPs (~ 26%, 62/236) were higher in SHIV-EVs (Fig. 1b). We previously reported [20] that both the size (nm) and concentration (particles/mL) of SHIV-EVs were significantly lower than CTL-EVs (n = 5/group). We further verified the presence of isolated circulating EVs by TEM analysis (Fig. 2a). The size of EVs measured by TEM was slightly higher than the size measured by ZetaView analyzer, both in SHIV-EVs and CTL-EVs, which is possibly due to long-term (more than a year) storage of EVs at − 80 °C. A recent study demonstrated that the size of plasma EVs significantly increased over storage time at − 80 °C [26]. In this study, we measured zeta potential (n = 5/group), which showed no significant differences between SHIV-EVs (average: − 31.25 mV) and CTL-EVs (average: − 33.47 mV) groups (Fig. 2b). Hallmark EV proteins were quantified by proteomic analysis in SHIV-EVs and CTL-EVs. Tetraspanins, cytoskeletal proteins, cytosolic enzymes, proteins associated with multivesicular bodies, and lipid rafts were abundantly expressed in both SHIV-EVs and CTL-EVs [20]. Previously, we validated the expression of CD63, CD81, GAPDH, and flotillin-1 in both SHIV-EVs and CTL-EVs using western blots [20]. In this study, we detected two other hallmark EV biogenesis-related proteins by western blot, Alix and TSG101, in both SHIV-EVs and CTL-EVs. Results indicated that isolated EVs were mostly small EVs because GRP94, a marker for large EVs, had very low abundance in isolated EVs. Negative detection of calnexin signifies the purity of the isolated EVs. A low abundance of the Golgi marker, GM130, indicated low cellular contamination in isolated EVs. Lipoprotein and albumin are the most common contaminants in serum/plasma-derived EVs. In our study, lipoprotein a was not detected; however, albumin was detected by western blots both in SHIV-EVs and CTL-EVs (Fig. 2c).

Fig. 1.

Experimental design and proteomic analysis of plasma circulating EVs in SHIV-infected and uninfected RMs. a The flow chart indicates the in vivo experimental design, time of plasma sample collection, and the use of different downstream applications of isolated circulating EVs from these samples. b Volcano plot indicates significant up- or lower DEPs in SHIV-EVs. A significant number of up-/down-regulated and non-significant proteins were indicated within the parentheses

Fig. 2.

Characterization of plasma circulating EVs in SHIV-infected and uninfected RMs. a Representative transmission electron microscopy pictures of circulating EVs isolated from SHIV-infected (SHIV-EVs) and uninfected (CTL-EVs) RMs. Scale bar: 500 nm. b Zeta potential (mV) of isolated plasma circulating SHIV-EVs and CTL-EVs was compared by ZetaView PMX-430-Z QUATT laser system (n = 5/group). c Serum/plasma (albumin and lipoprotein a), Golgi (GM130), large EV (GRP94), and small EV (Alix and TSG101) associated proteins were detected by western blots. Negative detection of calnexin signifies the purity of the isolated EVs (n = 5/group represented by the numbers)

Plasma circulating EV proteins evidenced dysregulation of synaptic signaling pathways in SHIV-infected RMs

The IPA indicated that SHIV-EVs proteins were involved in deactivation of synaptogenesis signaling, synaptic long-term potentiation/depression, glutamate receptor signaling, and activation of semaphorin neuronal repulsive signaling pathways (Fig. 3a). In IPA’s database, 315 proteins were associated with synaptogenesis signaling pathways, and 55% (173/315) of those proteins were quantified in our dataset. Interestingly, 61% (106/173) of proteins were lower and 39% (67/173) of proteins were higher in SHIV-EVs compared to CTL-EVs (Fig. 3b and Supplemental Table 1). Similarly, activation of semaphorin neuronal repulsive signaling pathway-associated proteins were quantified, 54% (81/150), of which 59% (48/81) were lower and 41% (33/81) were higher in SHIV-EVs (Fig. 3c and Supplemental Table 2). In this study, 51% (34/66) glutamate receptor signaling-associated proteins were quantified, and most proteins (76%, 26/34) were lower in SHIV-EVs (Fig. 3d and Supplemental Table 3). Likewise, deactivation of synaptic long-term potentiation-related 50% proteins (66/132) were quantified, of which 71% (47/66) were lower and 29% (19/66) were higher in SHIV-EVs (Fig. 3e and Supplemental Table 4). However, only 38% (75/198) of synaptic long-term depression-associated proteins were quantified, of which 67% (50/75) were lower and 33% (25/75) were higher in SHIV-EVs (Fig. 3f and Supplemental Table 5).

Fig. 3.

Plasma circulating EV proteins show evidence of synaptic signaling pathway dysregulation in SHIV-infected RMs. a Activation (positive z-score) and deactivation (negative z-score) of synaptic signaling pathways in SHIV-EVs were detected using the ingenuity pathway analysis (IPA) program. b-f In IPA’s database: number of proteins involved in synaptogenesis, semaphorin neuronal repulsive, glutamate receptor, synaptic long-term potentiation, and synaptic long-term depression pathways: 315, 150, 66, 132, and 198, respectively, indicated in parentheses. In the pie charts: white, brown, green, and red colors indicate the number of DEPs absent, present, lower, and higher, respectively in SHIV-EVs

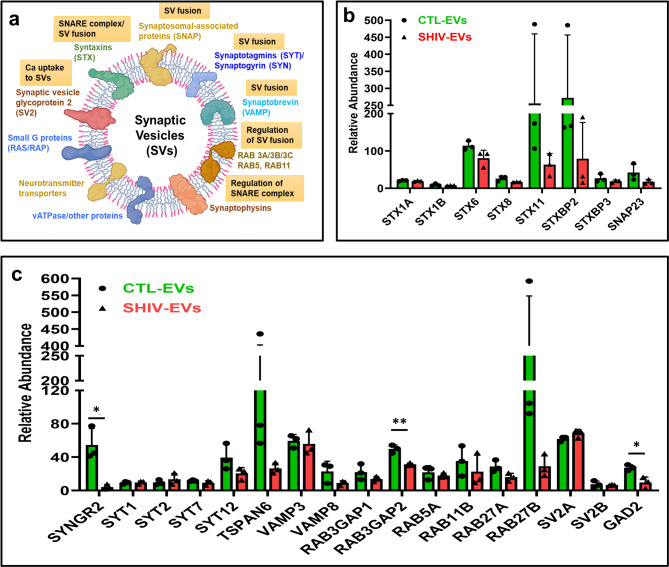

Synaptic vesicle (SV)-associated proteins of SHIV-infected RMs were lower in plasma circulating EVs

In our study, several proteins involved in SV biogenesis, formation/regulation of soluble N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor attachment protein receptor (SNARE) complex, and SV fusion (Fig. 4a) were identified in SHIV/CTL-EVs and some were in low protein abundance. Several syntaxin family proteins (STX1A/B, STX6/8/11, and STXBP2/3) and synaptosomal-associated protein (SNAP23) were less expressed in SHIV-EVs (Fig. 4b). Synaptogyrin 2 (SYNGR2) was significantly less abundant in SHIV-EVs (Fig. 4c). Except SYT2, SV-associated synaptotagmins (SYT1, SYT7, SYT12, and TSPAN6) were relatively less expressed in SHIV-EVs. Several small GTPases that are involved in regulation of SV fusion, such as RAB3, RAB5, RAB11, and RAB27 (A and B) proteins, were also relatively less expressed in SHIV-EVs (Fig. 4c). SV glycoprotein 2 A (SV2A) was highly expressed in both SHIV/CTL-EVs. Interestingly, glutamate decarboxylase 2 (GAD2), which is present in presynaptic terminals for synthesis of GABA for SV release, was significantly less expressed in SHIV-EVs (Fig. 4c).

Fig. 4.

Synaptic vesicle-associated proteins were lower on plasma circulating EV in SHIV-infected RMs. a Shows different groups of proteins present in synaptic vesicles. Figure created in BioRender. Chandra, P. (2025) https://BioRender.com/9x0v1ix.; b-c Relative abundance of synaptic vesicle-associated proteins in SHIV-infected (red: SHIV-EVs) and uninfected (green: CTL-EVs) plasma circulating EV measured by proteomic analysis (n = 3/group). The relative abundance of a biological replicate was calculated by averaging four experimental replicates. The data is presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). For statistical significance, unpaired t-test with Welch correction was performed (Variance assumption: Individual variance for each group; Multiple comparisons: False Discovery Rate (FDR); Method: Two-stage step-up (Benjamini, Krieger, and Yekutieli); Desired FDR (Q): 1.00%) using GraphPad Prism version 10.5.0 for Windows, and p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant

Proteins in SHIV-EVs evidenced deactivation of synaptogenesis signaling in presynaptic neurons

The IPA indicated that loss of neurexin-1 and − 2 was possibly linked to presynaptic terminal differentiation. High expressions of neuroligin-2, −3, and − 4 (Y-linked) and cadherin-1, −2, −5, 6, −11, and − 13 (Supplemental Table 1) were involved in activation of neuron adhesion and puncta adherentia junction formation in the synaptic cleft region (Fig. 5). However, lower expression of SV-associated proteins (Fig. 4b–c), syntaxin-1 A, −1B, and complexin 1 (CPLX1) as well as higher expression of synaptosome associated protein 25 (SNAP25) were involved in deactivation of SV priming, -docking, and -fusion. IPA revealed that lower expression of several proteins such as calmodulin 1 (CALM1), calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CAMK2-alpha, -beta, and -delta), syntaxin binding protein-2, −3, −5 (also known as MUNC18-2 to −5), unc-13 homolog A (UNC13A), heat shock protein family A (Hsp70) member 8 (HSPA8), N-ethylmaleimide sensitive factor, vesicle fusing ATPase (NSF), and NSF attachment protein-alpha (NAPA), -beta (NAPB), and -gamma (NAPG) possibly affected the SNARE complex formation, SV docking, and SV fusion. Except for adenylate cyclase (ADCY)−10, other adenylate cyclases, such as ADCY-2, −4, −5, −6, and − 9 were higher, which possibly lower the expression of several protein kinase A (PKA), or cAMP-dependent protein kinase family of enzymes, and ultimately decreasing the expression of synapsin-1 and − 2. Loss of synapsins possibly affected neurite outgrowth and SV binding. (Fig. 5 and Supplemental Table 1).

Fig. 5.

Plasma circulating EV proteins in SHIV-infected RMs show evidence of deactivation of synaptogenesis signaling in presynaptic neurons. IPA predicted DEPs involved in deactivation of synaptogenesis signaling in presynaptic neuron; color brightness is related to DEPs fold change, dark color indicates higher fold change; double outline indicates protein complexes/groups; orange and blue stars show possible activation and inhibition, respectively; presynaptic (blue) and postsynaptic (purple) neurons created in BioRender. Chandra, P. (2025) https://BioRender.com/9x0v1ix. ; DEPs are shown by standard abbreviations

In postsynaptic neurons, synaptogenesis signaling pathway-associated proteins were dysregulated in SHIV-EVs vs. CTL-EVs

Differential expressions of circulating EV proteins showed that synapse stabilization, synaptic spine development, and synaptic spine density likely decreased in post synaptic neurons in SHIV-infected RMs (Fig. 6). IPA indicated that α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA) receptor subunits, such as glutamate ionotropic receptor, AMPA type subunit 2 (GRIA2) and GRIA3 were lower in SHIV-EVs. Similarly, N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor subunits such as glutamate ionotropic receptor, NMDA type subunit 1 (GRIN1) and − 2 A (GRIN2A) were also under expressed in SHIV-EVs. Moreover, except for glutamate metabotropic receptor 5 (GRM5), other metabotropic glutamate receptors (GRM1, GRM2, GRM3, and GRM7), which participate in modulation of synaptic transmission, were lower in SHIV-EVs (Supplemental Table 1). Lower expression of LDL receptor related protein 1 (LRP1) led to upregulation of protein kinase C epsilon (PRKCE), which lower myristoylated alanine rich protein kinase C substrate (MARCKs), and finally, inhibited synaptic spine development (Fig. 6). The loss of CAMK2 could have lowered the expression of cAMP responsive element binding protein 1 (CREB1), causing deactivated synapse stabilization and synaptic spine development (Fig. 6). IPA indicated that loss of neurotrophic receptor tyrosine kinase 2 (NTRK2) led to inhibition of calmodulin. The loss of calmodulin lowers CAMK2 and ADCY, and higher Ras protein-specific, guanine nucleotide releasing factor 1 (RASGRF1). High expression of RASGRF1 led to inhibition of RAS family proteins. However, loss of CAMK2 led to the inhibition of AMPA receptors, CREB, and synaptic Ras GTPase-activating protein 1 (SYNGAP1). The loss of SYNGAP1 is linked to the downregulation of RAS and RAP family proteins (RAP1B, RAB2A, and RAP2B). Upregulation of Rap guanine nucleotide exchange factor 1 (RAPGEF1) and the downregulation of PKAs are also linked to the loss of RAP proteins. The loss of RAS and RAP likely involved deactivation of protein endocytosis (Fig. 6). Moreover, loss of RAP led to inhibition of catenin delta 1 (CTNND1), talin 1 (TLN1), and higher expression of adherens junction formation factor (AFDN), which led to inhibition of neuronal adhesion. The loss of RAP and Rac family small GTPase 1 (RAC1) in SHIV-EVs also inhibited synaptic spin density via downregulation of ERK1/2 signaling pathway. Furthermore, downregulation of RAC1 deactivated actin filament branching as well as synaptic spin development via either PAK1-LIMK1-CFL1 or WASF1-ARP2/3 pathways (Fig. 6 and Supplemental Table 1).

Fig. 6.

Plasma circulating EV proteins in SHIV-infected RMs show evidence of synaptogenesis signaling deactivation in postsynaptic neurons. Pathway analysis by IPA with participating DEPs involved in the deactivation of synaptogenesis signaling in postsynaptic neurons. Red or green color shows higher or lower proteins, respectively, in infected compared with uninfected RMs. Double outline indicates protein complexes/groups. Blue stars indicate possible inhibition. DEPs are denoted by standard abbreviations

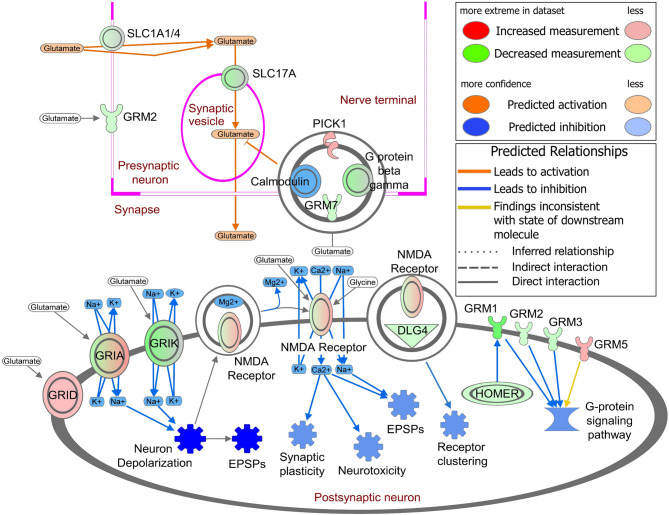

Plasma circulating EV proteins evidenced deactivation of glutamate receptor signaling in SHIV-infected RMs

The solute carrier, 1 A (SLC1A) family, incorporates two major mammalian transporters–glutamate transporters and the alanine, serine, and cysteine (ASC) transporters. High-affinity glutamate transporters, SLC1A1, SLC1A2, and SLC1A3, are primarily expressed in the brain, helping to prevent glutamate excitotoxicity. We observed that SLC1A1 and SLC1A4 (ASC transporter 1) were lower, whereas SLC1A2 and SLC1A3 were higher in SHIV-EVs. Similarly, SLC17A6 and SLC17A7 (also known as vesicular glutamate transporters VGLUT2 and VGLUT1, respectively) were lower in SHIV-EVs. Interestingly, except glutamate metabotropic receptor 5 (GRM5), which was higher, GRM1, GRM2, GRM3, and GRM7 were lower in SHIV-EVs (Fig. 7). Previously, we mentioned (Fig. 6 and Supplemental Table 1) that several AMPA receptor subunits, GRIA1 and glutamate ionotropic receptor delta type subunit 1 (GRID1) were higher, whereas GRIA2 and GRIA3 were lower in SHIV-EVs. Glutamate ionotropic receptor kainate type subunit 2 (GRIK2) and subunit 3 (GRIK3) as well as two NMDA receptor subunits, GRIN1 and GRIN2A, were lower in SHIV-EVs. Guanine nucleotide-binding (G) proteins transmit extracellular signals that activate or inhibit intracellular enzymes and ion channels. We observed that G protein subunit beta 1 (GNB1), beta 2 (GNB2), beta 4 (GNB4), beta 5 (GNB5), and G protein subunit gamma 3 (GNG3), gamma 5 (GNG5), gamma 7 (GNG7), and gamma 11 (GNG11) were all lower in SHIV-EVs. Excitatory postsynaptic potentials (EPSPs) increase the likelihood of a postsynaptic neuron firing an action potential, which was deactivated in SHIV-EVs, possibly due to lower expression of different glutamate receptors in postsynaptic neurons of SHIV-infected RMs. (Fig. 7 and Supplemental Table 3).

Fig. 7.

Plasma circulating EV proteins show evidence of deactivation of glutamate receptor signaling in SHIV-infected RMs. IPA revealed the DEPs involved in the deactivation of glutamate receptor signaling in postsynaptic neurons. Color brightness is related to the DEP fold change; darker color = higher fold change. DEPs are indicated by standard abbreviations. A double circle indicates a protein complex. Double outline indicates complexes/groups of proteins. Blue stars indicate possible inhibition. EPSPs: Excitatory postsynaptic potentials

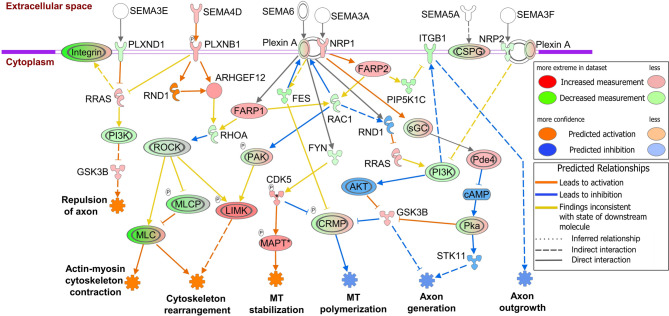

Plasma circulating EV proteins evidenced activation of semaphorin neuronal repulsive signaling in SHIV-infected RMs

We observed that the semaphorin neuronal repulsive signaling pathway was activated in SHIV-EVs with a z-score of + 2.2 (Fig. 3a). Semaphorin signaling occurs mostly via Plexin receptors and affects changes to the cytoskeletal and adhesive machinery that control cellular morphology. In our study, plexin A1 (PLXNA1) and -B1 (PLXNB1) were higher, and -A2 (PLXNA2) and -D1 (PLXND1) were lower in SHIV-EVs (Supplemental Table 2). Either the loss of PLXND1 (semaphorin 3E, SEMA3E receptor) or the activation of PLXNB1 (SEMA4D receptor) higher RAS-related protein (RRAS), which either activates axon repulsion or deactivates axon generation via PI3K and the glycogen synthase kinase 3 beta (GSK3B) pathway. High expression of SEMA4D and PLXNB1 higher Rho guanine nucleotide exchange factor 12 (ARHGEF12), which lowers Ras homolog family member A (RHOA). The loss of RHOA and RAC1 could have been due to upregulation of FERM, ARH/RhoGEF, and pleckstrin domain protein 1 and − 2 (FARP1 and FARP2) in SHIV-EVs. Rho-associated coiled-coil containing protein kinase 1 and − 2 (ROCK1 and ROCK2) were lower due to loss of RHOA, which higher several myosin light chains (MYL2, −3, −4, −5, −6B, −11, and − 12 A) and lower MYL6, −7, and − 9 proteins. Conversely, loss of ROCK and RAC1 higher LIM domain kinase 1 (LIMK1) and lower MLCs that activated cytoskeleton contraction and rearrangement (Fig. 8). Loss of PLXNA1 (receptor for SEMA6) activated microtubule (MT) stabilization via the FYN proto-oncogene, Src family tyrosine kinase (FYN), cyclin-dependent kinase 5 (CDK5), and the microtubule-associated protein tau (MAPT) pathway. High expression of either CDK5 or GSK3B lowers collapsin response mediator protein, 1 (CRMP1), which likely deactivates MT polymerization. Neuropilins (NRP) are also well-characterized semaphorin receptors, and NRP1 was higher, whereas NRP2 was lower in SHIV-EVs. The activation of cytoskeleton rearrangement may have occurred via the NRP1-FARP2-RAC1-PAK-LIMK1 pathway. However, axon generation was deactivated either via NRP1-sGC-PDE4D-PKA-STK11 or NRP2-PI3K-AKT-GSK3B pathways. Several integrin receptors were dysregulated in SHIV-EVs, and the loss of integrin beta 1 (ITGB1) likely deactivated axon outgrowth (Fig. 8 and Supplemental Table 2).

Fig. 8.

Plasma circulating EV proteins show semaphorin neuronal repulsive signaling activation in SHIV-infected RMs. Schematic diagram of a significantly altered signaling pathway identified by IPA. Relative changes in protein expression are illustrated by gradated shades of color coding: red, up; green, down; white, no change or not applicable. Direct and indirect interactions between molecules are depicted by solid and dotted lines, respectively. Double outline indicates complexes/groups of proteins. Orange and blue stars indicate possible activation and inhibition, respectively. DEPs are indicated by standard abbreviations

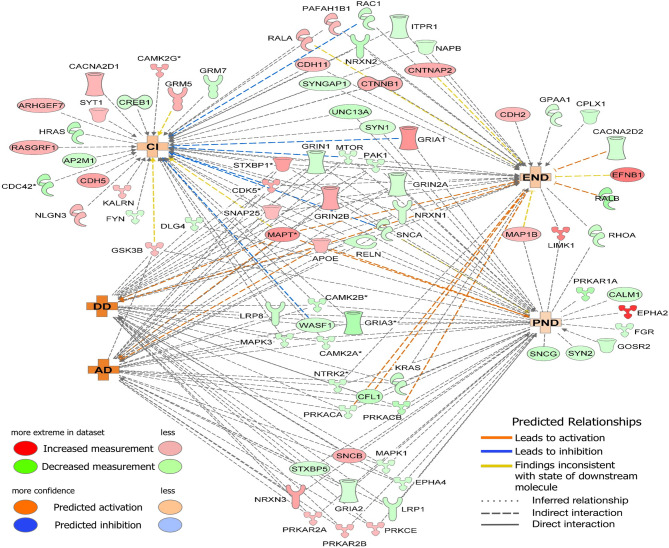

Protein network analysis showed that synaptogenesis signaling-associated DEPs were possibly involved in neuronal disorders/diseases in SHIV-infected RMs

Interestingly, 46% (80/173) of synaptogenesis signaling-associated DEPs (Fig. 9 and Supplementary Table 1) in SHIV-EVs are professed to be linked to cognitive impairment (CI), degenerative dementia (DD), Alzheimer’s disease (AD), early-onset of neurological disorder (END), and progressive neuronal disorder (PND). Among the disorders/diseases-associated DEPs, 40% (32/80) were lower and 60% (48/80) were higher in SHIV-EVs. Most DEPs demonstrated indirect interactions (indicated by black dotted lines) linked to two or more disorders/diseases. However, 15, 6, and 7 unique DEPs were only linked to CI, END, and PND, respectively (Fig. 9).

Fig. 9.

Synaptogenesis signaling-associated DEPs likely involved in neuronal disorders/diseases in SHIV-infected RMs. Using synaptogenesis signaling-associated DEPs as input, IPA predicted the link to activation (Red) of cognitive impairment (CI), degenerative dementia (DD), Alzheimer’s disease (AD), early-onset of neurological disorder (END), and progressive neurological disorder (PND) in SHIV-EVs

Discussion

Dysregulated synaptic signaling is substantially linked to an array of neurological and psychiatric disorders and diseases [27]. Under normal physiology, neurons release small EVs (commonly known as exosomes) to enhance neural circuit activity [28]. Recent studies have revealed the importance of small EVs in modulating synaptic activity, which evokes an interesting issue: whether small EVs function like non-canonical neurotransmitters or extracellular SVs [29]. We [20] and others [30, 31] have characterized brain-derived EVs from blood, which appear to be minimally invasive biomarkers for various neurodegenerative diseases, including HAND [32–34]. Recently, proteomic studies have matured as a promising tool in biological and medical research, interpreting a plethora of information toward decoding the molecular mechanisms of health and diseases. Our proteomics study revealed that proteins in SHIV-EVs are associated with dysfunction of synaptic signaling pathways, possibly due to the deactivation of synaptogenesis signaling, synaptic long-term potentiation/depression, and glutamate receptor signaling, as well as the activation of semaphorin neuronal repulsive signaling pathways. We observed that SV assembly/fusion-associated proteins were under-expressed in SHIV-EVs, which may involve deactivation of (a) SV priming, docking, and fusion in presynaptic neurons; and (b) synaptic spine development/density and synapse stabilization in postsynaptic neurons. Conversely, higher expressions of semaphorin neuronal repulsive signaling-proteins in SHIV-EVs indicated possible activation of cytoskeleton contraction and rearrangement, microtubule stabilization, and action repulsion as well as the deactivation of microtubule polymerization and action generation/outgrowth in SHIV-infected RMs. Moreover, dysregulated synaptic signaling-related DEPs in SHIV-EVs are linked to several neuropathology-related disorders/diseases.

Several recent reports revealed that small EVs are the key modulator of synaptic activities under physiological and pathological conditions [35, 36]. Small EVs exhibit similar morphology to SVs, which are released by their parent cells into extracellular spaces, and research has shown that these small EVs serve as critical mediators and/or regulators of neurotransmission [37]. Goetzl et al. reported that several synaptic proteins (e.g., synaptophysin, synaptopodin, synaptotagmin-2, neurogranin, synapsin 1, neuronal pentraxin 2, neurexin 2a, AMPA4 receptor, and neuroligin 1) were significantly reduced in plasma-isolated neural-derived small EVs of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) patients, and the loss of synaptic proteins were correlated with the extent of cognitive loss [30, 31]. In our study, several SV-associated syntaxins (STX), a SNARE complex component, were lower in SHIV-EVs. The STX11 is an atypical SNARE protein, which facilitates vesicle fusion at the immunological synapses of immune cells, where it interacts with the STX-binding protein 2 (STXBP2) [38], synaptobrevin (VAMP), and synaptosomal-associated protein 23 (SNAP23). Notably, STX11, STXBP2, VAMP3/8, and SNAP23 were lower in SHIV-EVs. Similarly, synaptogyrin 2 (SYNGR2) was also significantly lower, and several SV-associated synaptotagmins (SYT1, SYT7, SYT12, and TSPAN6) were relatively less expressed in SHIV-EVs. Small GTPase proteins, RAB3 and RAB27B participate in SV exocytosis, while RAB27B has an additional role in SV recycling at the presynaptic neuron. However, RAB5 contributes to the biogenesis and retrieval of SV components via clathrin-mediated endocytosis [39]. In our study, RAB3 GTPase-activating protein 1/2, RAB5A, and RAB27b were less expressed in circulating EVs of SHIV-infected RMs. Glutamic acid decarboxylase 2 (GAD2), also known as GAD65, is essential for the conversion of glutamate to gamma aminobutyric acid (GABA) on SVs and is the prime inhibitory neurotransmitter in the central nervous system [40]. GAD2 preserves GABAergic synapse function during neuronal activity, and the downregulation of GAD2 results in spontaneous seizures and premature lethality in rodents [41]. In our study, GAD2 was significantly less abundant in SHIV-EVs, which may suggest that the synaptic signaling was dysregulated in SHIV-infected RMs.

Recent studies have shown that small EVs alter presynaptic and/or postsynaptic signaling and control neurotransmitter release [42]. The fusion of SVs to the plasma membrane is a finely controlled process mediated by the SNAREs composed of VAMP2, STX-1, NSF, SNAP-25, Munc18–1, and RAB3 family proteins [43]. It is well-established that Munc18–1, Munc13–1 (also known as UNC13A), CAMK2, and CPLX1 act as a functional template to bind STX-1 and VAMP2, which initiate the SNARE complex assembly upon SNAP-25 entry. Our IPA analysis indicated that, except for SNAP-25, most previously listed proteins were less expressed in SHIV-EVs, which perhaps were involved in deactivation of SV priming, -docking, and -fusion due to dysregulation of synaptogenesis signaling in presynaptic neurons. Schizophrenia is a disorder of connectivity and synaptic signaling [44]. Elevated levels of SNAP-25 in SHIV-EVs may be linked to synaptic signaling deactivation in SHIV-infected RMs because a high level of SNAP-25 was observed in prefrontal lobe Broadman’s area 9 [45] and the cingulate cortex [46] in postmortem brains of schizophrenia patients. Presynaptic small EVs regulate postsynaptic retrograde signaling [36] and neuronal small EVs could be internalized by postsynaptic neurons and neighboring glial cells [42, 47]. In postsynaptic neurons, RAS, RAP1/2, and RAC1 are differentially stimulated by different forms of synaptic activity via the activation of NMDA and/or AMPA receptors-mediated trafficking events [48], which regulates synaptic plasticity, spine/synapse structure [49], and synaptic functions [50]. Our IPA analysis indicated that synapse stabilization, synaptic spine development, and spine density were possibly deactivated in postsynaptic neurons of SHIV-infected RMs due to dysregulation of NMDA/AMPA receptors and their downstream RAS, RAP, and RAC1 signaling pathways.

Abnormal semaphorin expression, or function, may result in altered neuronal connectivity or synaptic function associated with several developmental [51] and degenerative disorders/diseases including AD [52]. Semaphorins and their downstream signaling cascade regulate synaptic physiology including neuronal polarity and excitability, guiding axon growth and synapse formation/function by triggering actin cytoskeleton rearrangement, mainly due to alteration of actin filaments and the microtubule network after binding to specific receptors like plexins and neuropilins [53]. Like other semaphorins, the SEMA4D/PLXNB1 axis may positively or negatively control RHOA, brain activity, and regulate dendritic spine density [54]. In primary hippocampal neurons, exogenous application of SEMA4D caused PLXNB1-dependent activation of the RHOA-ROCK pathway and an increase in spine density [55]. Moreover, RAC1 has been shown to modulate actin cytoskeleton dynamics via the PAK, LIMK1 and the cofilin pathway, which have been directly implicated in regulation of neuronal growth and synaptic plasticity [56]. Interestingly, sera from glioblastoma multiforme patients contain high levels of SEMA3A in the EVs inducing brain vascular permeability [57]. Additionally, small EVs indirectly control neurotransmission by supporting synapses and increasing/decreasing neurite growth, axon regeneration, and neurotransmitter production [47, 58]. In our study, SEMA4D and its receptor, PLXNB1, were higher in SHIV-EVs. However, the downstream signaling proteins, RHOA, ROCK1/2, RAC1, and PAK1/3 were lower in SHIV-EVs, possibly linked to cytoskeleton contraction activation or rearrangement as well as microtubule polymerization deactivation and axon generation in SHIV-infected RMs.

EVs appear to be minimally invasive biomarkers for various neurodegenerative diseases, including HAND [32–34]. Interestingly, in our study, 46% (80/173) of synaptogenesis signaling-associated DEPs in plasma circulating EVs were predicted as linked to various neurological disorders/diseases in SHIV-infected RMs. Among these DEPs, 40% were lower and 60% were higher in SHIV-EVs. It is established that the elevated expression of apolipoprotein E (APOE), microtubule-associated protein tau (MAPT), cyclin-dependent kinase 5 (CDK5) [59], and LIM kinase 1 (LIMK1) [60] is associated with different neurological disorders/diseases. High levels of microtubule-associated protein 1B (MAP1B) impair human and mouse neuronal development and mouse social behaviors [61], and EPHA2 receptors aggravate ischemic brain injury [62]. In our study, all the above-mentioned proteins were higher in SHIV-EVs, indicating the likely activation of different neurological disorders/diseases in SHIV-infected RMs. In contrast, reduced expression of low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 1 (LRP1), regulating Aβ and APOE, is considered a potential contributing factor to neuronal disorders and cognitive decline, including AD [63, 64]. Deposition of Aβ is linked with a decrease of cAMP responsive element binding protein (CREB) phosphorylation in AD brains [65]. Decreased expression of neurexin 1 (NRXN1) and NRXN2 was observed in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of AD patients [66]. Low levels of alpha-synuclein (SNCA) are strongly associated with Parkinson’s disease. Loss of cell division cycle 42 (CDC42) causes defects in cerebellar development [67], in synaptic plasticity, and in remote memory recall [68]. Interestingly, LRP1, CREB1, NRXN1/2, SNCA, and CDC42 proteins, which were under expressed in SHIV-EVs, could be linked to HIV-associated neurological disorders/diseases.

There are some limitations in this study. (1) We focused only on the host proteins that are likely linked to HIV-associated dysregulation of synaptic signaling. However, viral proteins, especially glycoprotein 120, induce synaptic damage and synaptodendritic degradation [8] and reduce the glutamate receptor density [9]. Similarly, HIV-Tat promotes phosphorylation of NMDA receptors [10], downregulates SV-associated proteins [11], and impairs synaptic architecture [12]. (2) Perhaps SHIV-EVs will not have the same effect as HIV-infected patient plasma circulating EVs on HAND. (3) Small differences for some proteins may be due to variations over time; therefore, we need longitudinal studies to confirm that the cross-sectional results observed in this study are replicated at different time points. (4) Small sample size and the use of exoEasy Maxi Kit for EV isolation from plasma could be another limitation for this study.

Collectively, DEPs in plasma circulating EVs offer a new perspective on the dysregulation of synaptic signaling and synaptogenesis, where signaling-associated DEPs in plasma circulating EVs were involved in different neuronal disorders and diseases in SHIV-infected RMs. Our novel findings suggest that plasma EVs could be used in a noninvasive model/method to elucidate mechanisms involved in the development of CNS dysfunction and progression of neurological diseases such as HAND.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

We thank Nancy Busija, MA, CCC-SLP, for editing the manuscript. We thank Dana Liu, Kurtis Willingham, and Barbara Ridereddleman for technical help. We thank Jessie J Guidry and David K. Worthylake, Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center, New Orleans, LA, for proteomic analysis. We also thank the Anatomic Pathology Core (RRID: SCR_024606) and the Molecular Virology and Sequencing Core (RRID: SCR_027144) at the Tulane National Primate Research Center for tissue samples and plasma viral loads.

Authors’ contributions

P.K.C. conceived and designed experiments; S.E.B. provided plasma samples of rhesus macaques; P.K.C. performed experiments and interpreted in vitro experimental results; T.N.Z. characterized EVs and performed TEM analysis; M.K.P.S. performed bioinformatic analysis; P.K.C. and M.K.P.S. analyzed proteomic data; P.K.C. M.K.P.S., and T.N.Z. generated the figures; P.K.C. and D.W.B. drafted the manuscript; P.K.C., M.K.P.S., T.N.Z., I.R.G, S.C.S., S.E.B., J.R., and D.W.B. edited and revised the manuscript and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by NIH grants: R01NS136041 (PKC), R56AG075988 (DWB), R01HL148836 (DWB), R21AG063345 (DWB), R21/R33AI110158 (SEB), and P51OD011104 (TNPRC).

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Nightingale S, Ances B, Cinque P, et al. Cognitive impairment in people living with HIV: consensus recommendations for a new approach. Nat Rev Neurol. 2023;19(7):424–33. 10.1038/s41582-023-00813-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Taoufik E, Kouroupi G, Zygogianni O, Matsas R. Synaptic dysfunction in neurodegenerative and neurodevelopmental diseases: an overview of induced pluripotent stem-cell-based disease models. Open Biol. 2018;8(9):180138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Volk L, Chiu SL, Sharma K, Huganir RL. Glutamate synapses in human cognitive disorders. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2015;38:127–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.DeKosky ST, Scheff SW. Synapse loss in frontal cortex biopsies in Alzheimer’s disease: correlation with cognitive severity. Ann Neurol. 1990;27(5):457–64. 10.1002/ana.410270502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scheff SW, DeKosky ST, Price DA. Quantitative assessment of cortical synaptic density in alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 1990;11(1):29–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buttini M, Masliah E, Barbour R, Grajeda H, Motter R, Johnson-Wood K, Khan K, Seubert P, Freedman S, Schenk D, Games D. Beta-amyloid immunotherapy prevents synaptic degeneration in a mouse model of alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci. 2005;25(40):9096–101. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1697-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Terry RD, Masliah E, Salmon DP, Butters N, DeTeresa R, Hill R, et al. Physical basis of cognitive alterations in Alzheimer’s disease: synapse loss is the major correlate of cognitive impairment. Ann Neurol. 1991;30(4):572–80. 10.1002/ana.410300410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhou Y, Liu J, Xiong H. HIV-1 glycoprotein 120 enhancement of N-methyl-D-aspartate NMDA receptor-mediated excitatory postsynaptic currents: implications for HIV-1-associated neural injury. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2017;12(2):314–26. 10.1007/s11481-016-9719-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Melendez RI, Roman C, Capo-Velez CM, Lasalde-Dominicci JA. Decreased glial and synaptic glutamate uptake in the striatum of HIV-1 gp120 transgenic mice. J Neurovirol. 2016;22(3):358–65. 10.1007/s13365-015-0403-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.King JE, Eugenin EA, Hazleton JE, Morgello S, Berman JW. Mechanisms of HIV-tat-induced phosphorylation of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor subunit 2A in human primary neurons: implications for neuroaids pathogenesis. Am J Pathol. 2010;176(6):2819–30. 10.2353/ajpath.2010.090642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kannan M, Singh S, Chemparathy DT, Oladapo AA, Gawande DY, Dravid SM, et al. HIV-1 Tat induced microglial EVs leads to neuronal synaptodendritic injury: microglia-neuron cross-talk in neurohiv. Extracell Vesicles Circ Nucl Acids. 2022;3(2):133–49. 10.20517/evcna.2022.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hu G, Niu F, Liao K, Periyasamy P, Sil S, Liu J, et al. HIV-1 tat-induced astrocytic extracellular vesicle miR-7 impairs synaptic architecture. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2020;15(3):538–53. 10.1007/s11481-019-09869-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van Niel G, D’Angelo G, Raposo G. Shedding light on the cell biology of extracellular vesicles. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2018;19(4):213–28. 10.1038/nrm.2017.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rezaie J, Aslan C, Ahmadi M, Zolbanin NM, Kashanchi F, Jafari R. The versatile role of exosomes in human retroviral infections: from immunopathogenesis to clinical application. Cell Biosci. 2021;11(1):19. 10.1186/s13578-021-00537-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hornung S, Dutta S, Bitan G. CNS-derived blood exosomes as a promising source of biomarkers: opportunities and challenges. Front Mol Neurosci. 2020;13:38. 10.3389/fnmol.2020.00038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Si X, Tian J, Chen Y, Yan Y, Pu J, Zhang B. Central nervous system-derived exosomal Alpha-Synuclein in serum may be a biomarker in parkinson’s disease. Neuroscience. 2019;413:308–16. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2019.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen PC, Wu D, Hu CJ, Chen HY, Hsieh YC, Huang CC. Exosomal TAR DNA-binding protein-43 and neurofilaments in plasma of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis patients: a longitudinal follow-up study. J Neurol Sci. 2020;418:117070. 10.1016/j.jns.2020.117070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hubert A, Subra C, Jenabian MA, Tremblay Labrecque PF, Tremblay C, Laffont B, et al. Elevated abundance, size, and MicroRNA content of plasma extracellular vesicles in viremic HIV-1 + patients: correlations with known markers of disease progression. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2015;70(3):219–27. 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Larance M, Lamond AI. Multidimensional proteomics for cell biology. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2015;16(5):269–80. 10.1038/nrm3970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chandra PK, Braun SE, Maity S, Castorena-Gonzalez JA, Kim H, Shaffer JG, et al. Circulating plasma exosomal proteins of either SHIV-infected rhesus macaque or HIV-infected patient indicates a link to neuropathogenesis. Viruses. 2023;15(3):794. 10.3390/v15030794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Santhana RL, Paramsavaran S, Koay BT, Izan SA, Siti AN. Modification of the uranyl acetate replacement staining protocol for transmission electron microscopy. Int J Med Nano Res. 2016;3:013. 10.23937/2378-3664/1410013. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Seifert P. Modified Hiraoka TEM grid staining apparatus and technique using 3D printed materials and gadolinium triacetate tetrahydrate, a non-radioactive uranyl acetate substitute. J Histotechnol. 2017;40(4):130–5. 10.1080/01478885.2017.1361117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cikic S, Chandra PK, Harman JC, Rutkai I, Katakam PV, Guidry JJ, Gidday JM, Busija DW. Sexual differences in mitochondrial and related proteins in rat cerebral microvessels: A proteomic approach. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2021;41(2):397–412. 10.1177/0271678X20915127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chandra PK, Cikic S, Baddoo MC, Rutkai I, Guidry JJ, Flemington EK, et al. Transcriptome analysis reveals sexual disparities in gene expression in rat brain microvessels. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2021;41(9):2311–28. 10.1177/0271678X21999553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chandra PK, Cikic S, Rutkai I, Guidry JJ, Katakam PVG, Mostany R, et al. Effects of aging on protein expression in mice brain microvessels: ROS scavengers, mRNA/protein stability, glycolytic enzymes, mitochondrial complexes, and basement membrane components. Geroscience. 2022;44(1):371–88. 10.1007/s11357-021-00468-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gelibter S, Marostica G, Mandelli A, Siciliani S, Podini P, Finardi A, et al. The impact of storage on extracellular vesicles: a systematic study. J Extracell Vesicles. 2022;11(2):e12162. 10.1002/jev2.12162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xu Y, Song X, Wang D, Wang Y, Li P, Li J. Proteomic insights into synaptic signaling in the brain: the past, present and future. Mol Brain. 2021;14(1):37. 10.1186/s13041-021-00750-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee SH, Shin SM, Zhong P, Kim HT, Kim DI, Kim JM, et al. Reciprocal control of excitatory synapse numbers by Wnt and Wnt inhibitor PRR7 secreted on exosomes. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):3434. 10.1038/s41467-018-05858-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xia X, Wang Y, Qin Y, Zhao S, Zheng JC. Exosome: a novel neurotransmission modulator or non-canonical neurotransmitter? Ageing Res Rev. 2022;74:101558. 10.1016/j.arr.2021.101558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goetzl EJ, Kapogiannis D, Schwartz JB, Lobach IV, Goetzl L, Abner EL, et al. Decreased synaptic proteins in neuronal exosomes of frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. FASEB J. 2016;30(12):4141–8. 10.1096/fj.201600816R. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Goetzl EJ, Abner EL, Jicha GA, Kapogiannis D, Schwartz JB. Declining levels of functionally specialized synaptic proteins in plasma neuronal exosomes with progression of alzheimer’s disease. FASEB J. 2018;32(2):888–93. 10.1096/fj.201700731R. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Selmaj I, Mycko MP, Raine CS, Selmaj KW. The role of exosomes in CNS inflammation and their involvement in multiple sclerosis. J Neuroimmunol. 2017;306:1–10. 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2017.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Guha D, Lorenz DR, Misra V, Chettimada S, Morgello S, Gabuzda D. Proteomic analysis of cerebrospinal fluid extracellular vesicles reveals synaptic injury, inflammation, and stress response markers in HIV patients with cognitive impairment. J Neuroinflammation. 2019a;16(1):254. 10.1186/s12974-019-1617-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Guha D, Mukerji SS, Chettimada S, Misra V, Lorenz DR, Morgello S, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid extracellular vesicles and neurofilament light protein as biomarkers of central nervous system injury in HIV-infected patients on antiretroviral therapy. AIDS. 2019b;33(4):615–25. 10.1097/QAD.0000000000002121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kawahara H, Hanayama R. The role of exosomes/extracellular vesicles in neural signal transduction. Biol Pharm Bull. 2018;41(8):1119–25. 10.1248/bpb.b18-00167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Korkut C, Li Y, Koles K, Brewer C, Ashley J, Yoshihara M, et al. Regulation of postsynaptic retrograde signaling by presynaptic exosome release. Neuron. 2013;77(6):1039–46. 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ma Y, Li C, Huang Y, Wang Y, Xia X, Zheng JC. Exosomes released from neural progenitor cells and induced neural progenitor cells regulate neurogenesis through miR-21a. Cell Commun Signal. 2019;17(1):96. 10.1186/s12964-019-0418-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Halimani M, Pattu V, Marshall MR, Chang HF, Matti U, Jung M, et al. Syntaxin11 serves as a t-SNARE for the fusion of lytic granules in human cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Eur J Immunol. 2014;44(2):573–84. 10.1002/eji.201344011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Binotti B, Jahn R, Chua JJ. Functions of Rab proteins at presynaptic sites. Cells. 2016;5(1):7. 10.3390/cells5010007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Su F, Pfundstein G, Sah S, Zhang S, Keable R, Hagan DW, Sharpe LJ, Clemens KJ, Begg D, Phelps EA, Brown AJ, Leshchyns’ka I, Sytnyk V. Neuronal growth regulator 1 (NEGR1) promotes the synaptic targeting of glutamic acid decarboxylase 65 (GAD65). J Neurochem. 2025;169(1):e16279. 10.1111/jnc.16279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kakizaki T, Ohshiro T, Itakura M, Konno K, Watanabe M, Mushiake H, et al. Rats deficient in the GAD65 isoform exhibit epilepsy and premature lethality. FASEB J. 2021;35(2):e21224. 10.1096/fj.202001935R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Frühbeis C, Fröhlich D, Kuo WP, Amphornrat J, Thilemann S, Saab AS, et al. Neurotransmitter-triggered transfer of exosomes mediates oligodendrocyte-neuron communication. PLoS Biol. 2013;11(7):e1001604. 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yang X, Wang S, Sheng Y, Zhang M, Zou W, Wu L, et al. Syntaxin opening by the MUN domain underlies the function of Munc13 in synaptic-vesicle priming. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2015;22(7):547–54. 10.1038/nsmb.3038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Harrison PJ, Weinberger DR. Schizophrenia genes, gene expression, and neuropathology: on the matter of their convergence. Mol Psychiatry. 2005;10(1):40–68. 10.1038/sj.mp.4001558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Thompson PM, Sower AC, Perrone-Bizzozero NI. Altered levels of the synaptosomal associated protein SNAP-25 in schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 1998;43:239–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gabriel SM, Haroutunian V, Powchik P, et al. Increased concentrations of presynaptic proteins in the cingulate cortex of subjects with schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1997;54:559–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Men Y, Yelick J, Jin S, Tian Y, Chiang MSR, Higashimori H, et al. Exosome reporter mice reveal the involvement of exosomes in mediating neuron to astroglia communication in the CNS. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):4136. 10.1038/s41467-019-11534-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stornetta RL, Zhu JJ. Ras and Rap signaling in synaptic plasticity and mental disorders. Neuroscientist. 2011;17(1):54–78. 10.1177/1073858410365562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Carlisle HJ, Kennedy MB. Spine architecture and synaptic plasticity. Trends Neurosci. 2005;28:182–7. 10.1016/j.tins.2005.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Oh D, Han S, Seo J, Lee JR, Choi J, Groffen J, Kim K, Cho YS, Choi HS, Shin H, Woo J, Won H, Park SK, Kim SY, Jo J, Whitcomb DJ, Cho K, Kim H, Bae YC, Heisterkamp N, Choi SY, Kim E. Regulation of synaptic Rac1 activity, long-term potentiation maintenance, and learning and memory by BCR and ABR Rac GTPase-activating proteins. J Neurosci. 2010;30(42):14134–44. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1711-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Huber AB, Kania A, Tran TS, Gu C, De Marco Garcia N, LieberamI, Johnson D, Jessell TM, Ginty DD, Kolodkin AL. Distinct roles for secreted semaphorin signaling in spinal motor axon guidance. Neuron. 2005;48:949–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Good PF, Alapat D, Hsu A, Chu C, Perl D, Wen X, et al. A role for semaphorin 3A signaling in the degeneration of hippocampal neurons during Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurochem. 2004;91:716–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Alto LT, Terman JR. Semaphorins and their signaling mechanisms. Methods Mol Biol. 2017;1493:1–25. 10.1007/978-1-4939-6448-2_1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Barberis D, Casazza A, Sordella R, Corso S, Artigiani S, Settleman J, et al. P190 rho–GTPase activating protein associates with plexins and it is required for semaphorin signalling. J Cell Sci. 2005;2005(118):4689–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lin X, Ogiya M, Takahara M, YamaguchiW, Furuyama T, Tanaka H, Tohyama M, Inagaki S. Sema4D-plexin-B1 implicated in regulation of dendritic spine density through RhoA/ROCK pathway. Neurosci Lett. 2007;428:1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Meng Y, Takahashi H, Meng J, Zhang Y, Lu G, Asrar S, Nakamura T, Jia Z. Regulation of ADF/cofilin phosphorylation and synaptic function by LIM-kinase. Neuropharmacology. 2004;47(5):746–54. 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2004.06.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Treps L, Edmond S, Harford-Wright E, Galan-Moya EM, Schmitt A, Azzi S, et al. Extracellular vesicle-transported Semaphorin3A promotes vascular permeability in glioblastoma. Oncogene. 2016;35(20):2615–23. 10.1038/onc.2015.317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Prada I, Gabrielli M, Turola E, Iorio A, D’Arrigo G, Parolisi R, et al. Glia-to-neuron transfer of miRNAs via extracellular vesicles: a new mechanism underlying inflammation-induced synaptic alterations. Acta Neuropathol. 2018;135(4):529–50. 10.1007/s00401-017-1803-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ao C, Li C, Chen J, Tan J, Zeng L. The role of Cdk5 in neurological disorders. Front Cell Neurosci. 2022;16:951202. 10.3389/fncel.2022.951202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cuberos H, Vallée B, Vourc’h P, Tastet J, Andres CR, Bénédetti H. Roles of LIM kinases in central nervous system function and dysfunction. FEBS Lett. 2015;589(24 Pt B):3795 – 806. 10.1016/j.febslet.2015.10.032 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 61.Guo Y, Shen M, Dong Q, Méndez-Albelo NM, Huang SX, Sirois CL, et al. Elevated levels of FMRP-target MAP1B impair human and mouse neuronal development and mouse social behaviors via autophagy pathway. Nat Commun. 2023;14(1):3801. 10.1038/s41467-023-39337-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Thundyil J, Manzanero S, Pavlovski D, Cully TR, Lok KZ, Widiapradja A, et al. Evidence that the EphA2 receptor exacerbates ischemic brain injury. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(1):e53528. 10.1371/journal.pone.0053528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kang DE, Pietrzik CU, Baum L, Chevallier N, Merriam DE, Kounnas MZ, et al. Modulation of amyloid beta-protein clearance and Alzheimer’s disease susceptibility by the LDL receptor-related protein pathway. J Clin Invest. 2000;106(9):1159–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zlokovic BV, Deane R, Sagare AP, Bell RD, Winkler EA. Low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein-1: a serial clearance homeostatic mechanism controlling Alzheimer’s amyloid β-peptide elimination from the brain. J Neurochem. 2010;115(5):1077–89. 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.07002.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Vitolo OV, Sant’Angelo A, Costanzo V, Battaglia F, Arancio O, Shelanski M. Amyloid beta -peptide inhibition of the PKA/CREB pathway and long-term potentiation: reversibility by drugs that enhance cAMP signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99(20):13217-21. 10.1073/pnas.172504199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 66.Lleó A, Núñez-Llaves R, Alcolea D, Chiva C, Balateu-Paños D, Colom-Cadena M, et al. Changes in synaptic proteins precede neurodegeneration markers in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease cerebrospinal fluid. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2019;18(3):546–60. 10.1074/mcp.RA118.001290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Govek EE, Wu Z, Acehan D, Molina H, Rivera K, Zhu X, et al. Cdc42 regulates neuronal polarity during cerebellar axon formation and glial-guided migration. iScience. 2018;1:35–48. 10.1016/j.isci.2018.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kim IH, Wang H, Soderling SH, Yasuda R. Loss of Cdc42 leads to defects in synaptic plasticity and remote memory recall. Elife. 2014;3:e02839. 10.7554/eLife.02839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.