Abstract

Background

Tropical water lilies, vital aquatic ornamental plants, face significant challenges in overwintering outdoors in northern subtropical climates, which limits their ornamental and application values. This study investigates the mechanisms underlying the survival and adaptation strategies of tropical water lilies Nymphaea ‘Eldorado’, during cold periods, focusing on physiological, morphological, and ecological responses.

Result

Our research findings reveal that ‘Eldorado’ tubers, regardless of their ecodormancy state, can swiftly resume growth under favorable temperature conditions, indicating that the dormancy pattern of ‘Eldorado’ is characterized by ecodormancy. Investigations using paraffin sectioning of ‘Eldorado’ tubers demonstrate that accelerated cortical cell division and increased starch granule accumulation contribute to tuber enlargement for entering ecodormancy. Low-temperature experiments reveal that mid-ecodormant tubers of tropical water lilies are less cold-tolerant than fully ecodormant ones; after one month underwater at 4 °C, mid-ecodormant tubers showed no sprouting within seven days, while fully ecodormant tubers had an 80% sprouting rate after two months. Transcriptomic analysis of tubers at various ecodormancy stages revealed that differentially expressed genes are enriched in pathways related to secondary metabolite biosynthesis and plant hormone signaling. Combined with hormone content analysis, we propose that ABA, GA, JA, ETH, and BR are key factors inducing ecodormancy in ‘Eldorado’. Shortened photoperiod treatments effectively induced ecodormancy, with treated tubers showing greater enlargement and starch content compared to controls, alongside reduced new leaf count and soluble sugar content, indicating enhanced growth and nutrient accumulation. Furthermore, under a 5-hour light/19-hour dark photoperiod, the application of 100 µM JA significantly promoted tuber enlargement, while 50 µM ABA facilitated moderate enlargement, simultaneously supporting the induction of ecodormancy.

Conclusion

These findings deepen our understanding of plant dormancy and propose strategies to improve the overwinter survival and reproductive success of tropical water lilies in non-native climates, with implications for horticultural practices and biodiversity conservation.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12870-025-07427-4.

Keywords: Ecodormancy, Hormone analysis, Morphological changes, Physiological assessments, Transcriptomic analysis, Water lily

Introduction

Plant dormancy represents a crucial adaptive response to environmental stimuli, allowing plants to effectively endure adverse conditions over extended periods [1]. This biological process reflects the complex regulatory mechanism of plant life activities under environmental stress. Light and temperature are pivotal environmental factors that influence plant growth and development. These elements exert control over the dormancy phase through the regulation of hormone metabolism in the plant system [2–4]. The integration and conveyance of light and low-temperature signals are essential in how plants react to environmental shifts, particularly in adapting to seasonal changes and fluctuations in growth conditions.

In recent years, there has been progress in our understanding of plant dormancy mechanisms. Studies have pinpointed changes in hormonal balance as one of the key in managing both dormancy and awakening processes [5]. Hormones such as abscisic acid (ABA), gibberellins (GA), and ethylene (ETH) help coordinate the ecodormant cycle of different plant ecodormant states, ABA is often associated with maintaining the ecodormant state, while GA is involved in ending dormancy and restarting growth. Moreover, the influence of environmental cues, including light and temperature, on plant hormone metabolism, unveils a sophisticated regulatory network, which encompasses numerous signal transduction pathways and gene expression regulation [6, 7].

The underground stem swelling observed in bulbous plants primarily functions as a storage mechanism [8, 9]. Under favorable conditions, these plants enter a rapid growth phase, during which they accumulate carbohydrates, proteins, and water within their underground stems [10]. This accumulation process is influenced by hormonal regulation, where auxins, salicylic acid, and cytokinins play vital roles in promoting stem swelling [11]. On the flip side, dormancy emerges as a survival strategy for these plants to endure adverse conditions, characterized by a significant reduction in metabolic activity. This state is usually triggered by environmental cues, such as fluctuations in temperature and changes in photoperiod [12]. During the dormancy period, the levels of abscisic acid (ABA) rise, leading to the downregulation of growth-promoting hormones and the activation of mechanisms for stress resistance [13]. Environmental factors play a role in regulating both the processes of swelling and dormancy. Temperature is one of the factor, with lower temperatures often marking the onset of dormancy [14]. Additionally, the photoperiod, soil moisture, and nutrient availability impact these processes. For example, a decrease in photoperiod is linked to the initiation of dormancy in certain plants [15, 16]. During the dormancy process of Norway spruce, short-day conditions induce the formation of bud-shoot barriers that block water transport to winter buds, thereby promoting dormancy establishment [17].

The genus Nymphaea, encompassing a diverse array of species and their variants, based on analyses of genetic differentiation and evolutionary relationships, it is divided into five subgenera, including Nymphaea, Brachyceras, Lotos, Hydrocallis, and Anecphya [18], has adapted to a wide range of ecological environments through gradual evolution under varying environmental conditions [19]. This adaptation process has resulted in the emergence of two distinct ecological types, tropical water lilies (Brachyceras, Lotos, Hydrocallis, and Anecphya) and hardy water lilies (Nymphaea), each exhibiting significant differences in their characteristics. Tropical water lilies cannot overwinter in northern subtropical (24.3°N latitude) or more northern regions, while hardy water lilies inhabit subtropical, temperate, and cold temperate zones north of 25°N latitude, these plants are capable of withstanding lower temperatures and thrive in such conditions [20]. During winter, hardy water lilies enter a state of full ecodormancy and exhibit resistance to cold. Their tubers can safely overwinter beneath ice layers in the mud, enduring temperatures down to −15 °C. Upon the arrival of spring and thawing, as water temperatures reach approximately 10 °C, their underground stems begin to sprout, leading to the flowering stage [21].

Tropical water lilies surpass cold-hardy varieties in ornamental value, showcasing a diverse array of flower shapes and colors, thereby enhancing their horticultural appeal [22]. However, their inability to overwinter in terrestrial conditions significantly limits their application and value in non-tropical regions. Thriving in temperatures ranging from 18 to 35 °C, tropical water lilies lack a natural dormancy period during winter. They can maintain slow growth and continue flowering as long as the air temperature remains above 15 °C and the water temperature stays above 10 °C [20]. In subtropical areas, certain varieties of tropical water lilies can continue to bloom even with the arrival of early frosts in November. Nevertheless, when temperatures drop below 0 °C, they face the risk of freezing to death. While lower temperatures can induce dormancy, they often fail to complete this process before winter begins. Therefore, unlike hardy water lilies, in suitable environment they cannot store nutrients in their increasingly swollen underground stems nor enter dormancy before the onset of harsh winter conditions.

Based on the classification of dormancy triggers, bud dormancy in plants is divided into paradormancy, endodormancy, and ecodormancy. Ecodormancy refers to dormancy induced by unfavorable environmental conditions (e.g., nutrient deficiency, water stress, inappropriate light or temperature) and is also known as environmental dormancy, exogenous dormancy, or altogenic dormancy. This type of dormancy can be readily reversed once favorable environmental conditions are restored [23]. During the growing season, tropical water lilies may encounter various adverse environmental conditions, such as nutrient deficiency, leading to halted growth and the formation of swollen underground stems, entering the state of ecodormancy. This ecodormant tuber exhibits significant environmental adaptability, capable of sprouting new plants under favorable conditions after adversity, it presents new possibilities for cultivating tropical water lilies in non-tropical regions. In this study, we selected the tropical water lily Nymphaea ‘Eldorado’ (Martin E. Randig) as our research subject to systematically investigate its entire growth cycle and ecodormancy characteristics. “Eldorado” is recognized as an outstanding aromatic cultivar, notable for its high ionone content and distinctive sweet fragrance [24]. Additionally, herbal tea produced from freeze-dried ‘Eldorado’ flowers retains valuable nutritional and health-promoting properties [25]. Furthermore, ‘Eldorado’ ranked second in a comprehensive phenotypic diversity analysis of 49 water lily accessions, highlighting its considerable potential for horticultural development and broader cultivation [26]. Building on these attributes, our study aims to elucidate the molecular regulatory mechanisms underlying ecodormant stem formation in ‘Eldorado’ and to develop artificial intervention strategies for inducing ecodormancy. These insights will provide both methodological and theoretical foundations for improving overwintering protection and expanding horticultural applications of tropical water lilies.

Results

Growth and ecodormancy characteristics of ‘Eldorado’

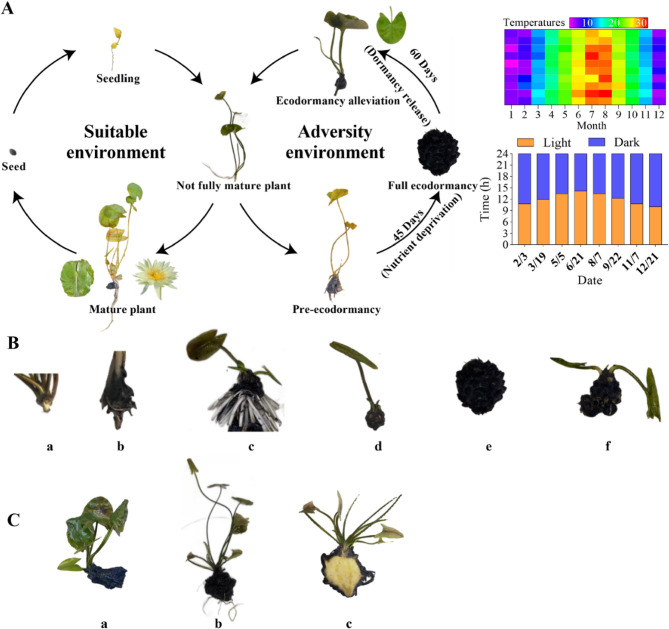

In the distinct four-season subtropical climate of Nanjing, China, we conducted observations on the growth cycle and ecodormancy characteristics of the tropical water lily ‘Eldorado’ within its natural environment. Our findings reveal that ‘Eldorado’ seeds are viable for germination under favorable environmental conditions. As the growth and development process progresses, the increase in both root and leaf count is observed (Fig. 1A). At the seedling stage, both the cotyledons and the first pair of true leaves exhibit a yellow coloration. The first true leaves display smooth margins with a distinct notch and lack any surface spots (Fig. 1A). When plants have 3–5 floating leaves and no flower buds are present, they are considered not fully mature plants (Fig. 1A). When the plants reach a developmental stage characterized by multiple floating leaves and flower buds, they are considered mature plants (Fig. 1A). At this stage, the leaves are larger, with serrated edges, and display red-brown spots on their surfaces, varying in color from grass green to dark green. When cultivated in Hainan, China (tropical region), we observed that ‘Eldorado’ can grow and flower throughout the year without forming underground tubers (Fig. 1A). Following flowering, the plant can produce seeds (Fig. 1A).

In response to suboptimal environmental conditions, non-tuberous plants gradually enter a ecodormant state, as depicted in Fig. 1A. The depth of ecodormancy is contingent upon the duration of environmental stress, if conditions ameliorate to become more favorable, ecodormancy will be halted, and the plant will resume growth (Fig. 1A). During the transition into ecodormancy, the growth of aboveground parts gradually slows, the emergence of new leaves decreases, and flower buds become fewer and poorly developed, ultimately resulting in a failure to flower. Simultaneously, the underground stem starts to swell, and the root system begins to deteriorate progressively. The developmental process of the tropical water lily ‘Eldorado’ under adverse conditions is delineated into distinct phases: pre-ecodormancy, mid-ecodormancy, late-ecodormancy, full ecodormancy, and finally, ecodormancy alleviation. as illustrated in Fig. 1B. Upon encountering adverse environmental stressors, such as nutrient deficiencies observed in this experiment, the underground stem section that connects the petiole to the root system begins to swell and develops a hard, dark brown epidermis (Fig. 1B-a). The initial formation of the tuber indicates the plant’s entry into the stage of pre-ecodormancy. (Fig. 1B-b). With increasing stress, the number of leaf buds on the underground stem diminishes, and its surface becomes covered with black tissue, likely formed from decaying root material. During this phase, despite the plant’s continued ability to produce leaves and flowers, growth rates decelerate, and the formation of black spherical structures is observed (Fig. 1B-c), this indicates the mid-ecodormancy phase. As the leaf count reduces to fewer than five, the plant progresses into the late ecodormancy phase. At this juncture, even emerging flower buds on the tuber cannot penetrate the water surface to bloom, and the growth of new leaves is too sluggish to reach the water’s surface (Fig. 1B-d). Subsequently, leaf production halts entirely, with no formation of new leaf buds, culminating in a tuber entering a state of full ecodormancy (Fig. 1B-e). Occasionally, small tubers resembling the ecodormant tuber in morphology may develop (Fig. 1B-f), these are also capable of sprouting. With the amelioration of external environmental conditions, the dormant tubers awaken from ecodormancy, capable of germinating anew to form new plants (Fig. 1C). Leaf buds sprout from their apices, evolving into floating leaves (Fig. 1C-a). As growth and development advance, roots begin to emerge at the juncture where the tuber top meets the leaves (Fig. 1C-b). At the point of connection with the tuber (Fig. 1C-c), an increase in root density can lead to the complete detachment of the plant from the tuber, marking the end of the ecodormancy period. A single ecodormant tuber can yield 1–5 ‘Eldorado’ tropical water lily seedlings.

This result offers insights into the adaptability and reproductive strategies of the tropical water lily ‘Eldorado’. In contrast to temperate species, ‘Eldorado’ does not form an enlarged underground stem under favorable conditions. This adaptation appears to be a response to the consistently warm climate of its native habitat, where the physiological importance of energy conservation through ecodormancy is diminished. However, in the face of adverse conditions, such as nutrient scarcity, ‘Eldorado’ demonstrates a capacity to enter ecodormancy, as demonstrated by the developmental stages of the underground stem (Fig. 1B). This capability to transition from active growth to ecodormancy highlights the species’ remarkable adaptability and resilience.

Fig. 1.

Phenotypic stages of the tropical water lily ‘Eldorado’ throughout its growth cycle. (A) Developmental progression of the tropical water lily ‘Eldorado’, illustrating the plant’s growth over time. The heatmap on the right represents the stable fluctuations across different months, while the bar chart shows changes in the photoperiod at major climate change time points in Nanjing, China. (B) Ecodormancy was induced in tropical water lilies grown hydroponically by depriving them of nutrients, and observed the characteristics of ecodormancy at different stages. Development stages of the tuber include: (a) pre-ecodormancy, (b) initial tuber enlargement, (c) mid-ecodormancy, (d) late-stage tuber enlargement, (e) full ecodormancy, (f) tubercles develop on the mother tuber. (C) Appearance of tubers during ecodormancy release: (a) represents a tuber post-germination before root emergence; (b) represents a tuber post-germination with roots; (c) represents a longitudinal section of a sprouted tuber with roots

A key differentiation between tubers in a partial ecodormancy state during the adverse ecodormancy period and those in complete ecodormancy is the growth or absence thereof of leaves and buds on the tubers. Additionally, the production of small but viable tubers on the big tubers of ‘Eldorado’ during ecodormancy constitutes an efficient reproductive strategy, facilitating the species’ survival and propagation in unfavorable conditions. This approach is particularly beneficial for tropical species, enabling rapid colonization and recovery when favorable conditions prevail, highlighting the dynamic adaptability of its survival strategy.

The anatomical structure and cold tolerance of dormant tubers

During natural overwintering outdoors in Nanjing, the water lily ‘Eldorado’ may exhibit one of three states. The first involves continued growth without the development of ecodormant tubers, ultimately leading to the plant’s demise in freezing conditions. The second scenario entails the formation of partially ecodormant tubers, identified by pale yellow or white filamentous structures at the tuber’s apex and a significant concavity, with leaf buds emerging (Fig. 2A). The third scenario results in fully ecodormant tubers (Fig. 2B), in which the underground stem becomes a tuber lacking leaves and leaf buds, with no new leaf buds appearing unless conditions become favorable. The observed differential responses to overwintering outdoors in Nanjing elucidate the species’ complex mechanisms to cope with freezing temperatures, which is critical for understanding and predicting the resilience of aquatic plants in changing climates.

Fig. 2.

Changes in tuber status and internal structural characteristics during the natural overwintering process of ‘Eldorado’. (A) Longitudinal section of a mid-ecodormant tuber. (B) Longitudinal section of a fully ecodormant tuber. (C) Anatomical structure of ‘Eldorado’ tubers: (a) represents the cortical and phloem structures in an ecodormant tuber; (b) represents the cortical and phloem structures in a mid-ecodormant tuber; (c) represents the apical bud site in an ecodormant tuber; (d) represents to the apical bud site in a tuber not fully ecodormant; (e) represents the central part of an ecodormant tuber; (f) represents the central part of a mid-ecodormant tuber. Co: cortex; SG: starch grains; Ph: phloem; Ac: protein cells. (D) Variation in starch content in tubers during the early ecodormancy (C1), mid-ecodormancy (C2), and full ecodormancy (C3) stages. Bars with different letters indicate significant differences (P < 0.05) according to Tukey’s multiple comparisons test

During the transition from partial to full ecodormancy, tubers undergo significant internal structural changes. The tuber comprises two principal components: an outer layer formed by black decaying roots and a hard, brown outer epidermis. As ecodormancy deepens, the outer epidermis thickens gradually and can detach from the inner layers, offering protection to the tuber (Figs. 2A, B). Analysis of paraffin-embedded tuber sections stained with Periodic Acid-Schiff (PAS) to visualize starch-protein complexes under a light microscope (Fig. 2C) shows that the beige internal tissue mainly consists of the cortex and vascular bundles. With the progression of ecodormancy, there is an acceleration in cell division, a reduction in cell size, and an increase in the number of cells and starch granules within each cell (Figs. 2C, b), aiding in nutrient accumulation and tuber enlargement. Simultaneously, the quantity of protein cells at the apical bud decreases as growth ceases (Figs. 2C, d), and the tissue structure in the central region becomes denser (Figs. 2C, f). The starch content within the tuber reaches its peak during full ecodormancy and is minimal in the initial stages, with notable differences, suggesting a gradual rise in starch content as ecodormancy advances (Fig. 2D). The internal structural changes occurring during the transition from partial to full ecodormancy, including the thickening of the outer epidermis and the accumulation of starch granules, are indicative of the plant’s physiological adaptations for energy conservation and protection. The hardening of the outer epidermis serves not only as a physical barrier against cold but also potentially reduces metabolic costs by limiting transpiration and other energy-intensive processes.

The study further analyzed the impact of the winter lakebed’s average minimum temperature (4 °C) on the different developmental stages of ‘Eldorado’ (Fig. 3A). Not fully mature ‘Eldorado’ plant with 3–5 floating leaves, when cultured at 4 °C for 24 days, predominantly experienced root and leaf decay, with few floating leaves maintaining its original condition, albeit significantly decayed. Further comparisons assessed the effects of low temperature on fully ecodormant, mid-ecodormant tubers, and those just resuming growth. Given that tropical water lilies can grow year-round in their native habitat, continuously supplying oxygen to underground parts, they may lack the ability to adapt to prolonged hypoxic environments, thus becoming unable to endure the cold winters of subtropical climates for several months [22]. Consequently, treatments for preserving tropical water lily underground tubers in aerated, moist mediums were also designed.

Fig. 3.

Impact of low temperatures on tubers of ‘Eldorado’ at different developmental stages and analysis of their regrowth capabilities. (A) Phenotypic changes in ‘Eldorado’ ecodormant tubers under low temperature treatment, according to different preservation conditions and ecodormant statuses. Treatment groups are defined as SW (regrowing ecodormant tubers), FA (fully ecodormant tubers preserved in an aerated environment), MA (mid-ecodormant tubers preserved in an aerated environment), FW (fully ecodormant tubers preserved underwater), and MW (mid-ecodormant tubers preserved underwater). (B) Re-sprouting rate of ‘Eldorado’ tubers after 7 days in suitable environment following various low-temperature treatments. ND: Nil Data. (C) Bud number in regrowing tubers after different treatments. F, fully ecodormant tubers; FW1, fully ecodormant tubers preserved underwater at low temperature for one month; FW2, fully ecodormant tubers preserved underwater at low temperature for two months. All groups were labeled with a (ANOVA p = 0.964), indicating no statistical difference

Before the low-temperature treatment (0 months), all recovering and mid-ecodormant tubers sprouted leaf buds and could grow normally under suitable conditions. One month after low-temperature treatment, mid-ecodormant tubers in aerated mediums exhibited signs of rot, while fully ecodormant tubers remained largely unchanged, and tubers preserved underwater showed no changes in appearance. However, growth in recovering tubers halted, and leaf edges began to rot. In the regrowth experiment, only tubers preserved underwater were able to sprout and maintain normal growth (Fig. 3A). Two months after low-temperature treatment, mid-ecodormant tubers preserved in aerated mediums displayed a darkening color, softening, and loosening at the base, accompanied by a foul smell. Some fully ecodormant tubers exhibited localized darkening and softening at the edges. Mid-ecodormant tubers preserved underwater also showed signs of decay. Leaves of recovering tubers were almost completely rotted, with only one leaf remaining attached to the tuber. In the regrowth experiment, only tubers preserved underwater could sprout and continue normal growth (Fig. 3A). By the third and fourth months of cold treatment, tubers from all treatments showed signs of decay, detectable by smell. In the regrowth experiment, no treated tubers were able to sprout (Fig. 3A), indicating that tubers preserved in aerated mediums were more susceptible to shrinkage and decay than those preserved underwater, which were more likely to retain their vitality. Fully ecodormant tubers, untreated or treated for one or two months with low temperatures, could sprout within seven days when placed in suitable conditions, suggesting that ecodormant state maintenance is environmentally controlled, and growth rapidly resumes once low-temperature stress is alleviated.

Differences in germination capabilities among the treatments in the regrowth experiment were observed (Fig. 3B). Untreated ecodormant tubers sprouted individual leaves by the seventh day under suitable conditions; however, tubers stressed by low temperature for a month showed no leaf unfurling within the same period. The number of tubers capable of sprouting varied among those preserved underwater (Fig. 3B). Dormant tubers without low-temperature treatment had a germination rate of 100% under suitable conditions; this rate remained 100% after one month of low-temperature treatment but dropped to 80% after two months, indicating that prolonged low-temperature treatment gradually diminishes the viability and germination capability of ecodormant tubers. The analysis of leaf number changes after tuber sprouting under different durations of low temperature aimed to determine if the length of low-temperature exposure affects tuber sprouting (Fig. 3C). No significant differences were found in the number of leaves after sprouting between untreated ecodormant tubers and those subjected to one or two months of low-temperature stress, indicating that low-temperature stress does not significantly affect the number of sprouts in tubers capable of germination. As the duration of low-temperature stress increases, the rate of recovery growth for ecodormant tubers gradually slows. Beyond a certain period, ecodormant tubers lose their vitality and cannot germinate, even under suitable conditions.

Physiological responses of water Lily tubers under different preservation conditions

Initially, cold stress impairs the plant’s cellular membrane system, followed by the destruction of internal structures. The damage to the cellular membrane at lethal temperatures is irreversible [27]. Malondialdehyde (MDA) content and relative electrical conductivity serve as critical indicators to evaluate the extent of cellular membrane damage [28]. Our findings indicate that cold stress inflicts damage on the cellular membrane system of tubers at different stages across various treatments, with both MDA content and relative electrical conductivity exhibiting an increasing trend (Fig. 4A, B). In aerated mediums, fully ecodormant tubers reached their highest MDA content of 4.04 nmol·g−1 FW after one month, while tubers preserved underwater exhibited lower MDA contents, specifically 2.75, 2.58, and 2.31 nmol·g−1FW. This suggests that underwater preservation offered protection against cold stress compared to aerated mediums. The relative electrical conductivity measurements corroborate this finding. As the duration of cold treatment increases, mid-ecodormant tubers in aerated mediums demonstrate the most significant increase in relative electrical conductivity, whereas tubers preserved underwater show the smallest increase. This indicates that underwater preservation more effectively minimizes damage caused by cold temperatures. Given the alterations in MDA content and relative electrical conductivity, underwater preservation improves the cold tolerance of tubers in different states, with fully ecodormant tubers exhibiting stronger cold resistance than mid-ecodormant tubers.

Osmotic regulation system protects cellular structures under cold conditions by accumulating substances like proline and soluble proteins, which scavenge reactive oxygen species and lower the cellular osmotic potential, thus mitigating damage [29]. Our results reveal that under aerated medium preservation conditions, the soluble protein content of tubers decreases with the duration of cold treatment (Fig. 4C). Specifically, the reduction in soluble protein content was 13.84% for mid-ecodormant tubers and merely 1.76% for fully ecodormant tubers. Conversely, under underwater preservation conditions, the soluble protein content displayed an increasing trend. After two months of cold treatment, the soluble protein content in tubers preserved underwater was significantly higher than that in tubers preserved in aerated mediums, indicating that underwater preservation more effectively enhances cold tolerance. The proline content in tubers preserved in both aerated mediums and underwater exhibited a decreasing trend with the duration of cold treatment (Fig. 4D). However, under underwater preservation conditions, the proline content in fully ecodormant and sprouting tubers showed an increasing trend, especially after two months of treatment, suggesting that underwater preservation conditions bolster cold tolerance through the accumulation of proline. These findings suggest that underwater preservation affords better protection under cold conditions, reducing tuber damage and enhancing cold tolerance compared to preservation in aerated mediums.

Fig. 4.

Effects of different treatment conditions on tuber cell membrane system and antioxidant enzyme activities under cold stress. This figure presents a comprehensive analysis of the impact of cold stress at 4 °C on the cell membrane system and antioxidant enzyme activities of sleeping water lily tubers subjected to one and two months of treatment. The analysis includes measurements of malondialdehyde (MDA) content (A), relative conductivity (B), soluble protein content (C), proline content (D), and the activities of Ascorbate Peroxidase (APX) (E), Catalase (CAT) (F), Superoxide Dismutase (SOD) (G), and Peroxidase (POD) (H). Treatment groups are defined as SW (regrowing ecodormant tubers), FA (fully ecodormant tubers preserved in an aerated environment), MA (mid-ecodormant tubers preserved in an aerated environment), FW (fully ecodormant tubers preserved underwater), and MW (mid-ecodormant tubers preserved underwater). Statistical significance is denoted by bars with different letters, indicating significant differences (P < 0.05) according to Tukey’s multiple comparisons test

Antioxidant enzymes, vital for scavenging excess reactive oxygen species within the plant, serve as widely used indicators for assessing plant resistance [30]. Our study indicates that the activity of ascorbate peroxidase (APX) in tubers under all treatments declines with prolonged cold stress (Fig. 4E), with the dormant state of tubers having a minimal impact on APX activity, while the preservation method significantly affects APX activity within the tubers. The activity of antioxidant enzymes in dormant or partially dormant tubers preserved underwater was markedly higher than in tubers preserved in aerated mediums. APX activity was most responsive to cold in sprouting tubers, significantly exceeding other treatments. This may be attributed to the higher cellular activity in sprouting tubers, which elicit a more robust cold-resistant response, highlighting APX’s crucial role in water lily cold resistance. Similar patterns were observed for catalase (CAT) activity. After one month of cold treatment, CAT activity in sprouting tubers preserved underwater was significantly greater than in other tubers (Fig. 4F). After two months, significant differences in CAT activity emerged under different treatment conditions, with an upward trend in CAT activity in sprouting and dormant tubers preserved underwater, whereas CAT activity in tubers preserved in aerated mediums decreased. As the duration of cold treatment extended, the activity of superoxide dismutase (SOD) in tubers preserved underwater trended upwards (Fig. 4G); SOD activity in dormant tubers preserved in both aerated medium and underwater was highest after one month of cold treatment. After two months, SOD activity in dormant tubers preserved underwater was significantly higher than in other treatments. Peroxidase (POD) activity exhibited different trends. After one month of cold treatment, POD activity in partially dormant tubers was significantly higher than in dormant tubers (Fig. 4H). POD activity was lowest in dormant tubers under both treatments, indicating weaker POD activity in the dormant state. After two months, POD activity in dormant tubers was the highest, showing increased adaptability over time.

The activity of the four antioxidant enzymes displayed different trends under varying treatment conditions, possibly due to their distinct roles and mechanisms within the antioxidant defense system. The growth state of tubers (e.g., partially dormant, dormant, sprouting) significantly influences changes in internal antioxidant enzyme activity. Partially dormant tubers are typically more sensitive to cold stress, whereas dormant and sprouting tubers exhibit stronger antioxidant capabilities. Different preservation methods (e.g., aerated medium and underwater preservation) significantly impact the antioxidant enzyme activity within tubers. For instance, underwater preservation seems to somewhat enhance the antioxidant capability of tubers, particularly in dormant and sprouting tubers. As the duration of cold stress lengthens, the changes in antioxidant enzyme activity display specific patterns, indicating tubers’ physiological adjustments and adaptability under sustained stress.

Through phenotypic observation, physiological indicator measurement, and analysis, it was determined that the tropical water lily ‘Eldorado’ lacks the ability to overwinter, and tubers exhibit poor cold tolerance when not formed. The production of tubers aids their reproductive development, with dormant tubers demonstrating stronger cold resistance than partially dormant tubers. Tubers preserved underwater can withstand two months of low temperatures at 4 °C, still retain vitality, and resume growth under suitable conditions, granting the tropical water lily ‘Eldorado’ the capacity to overwinter outdoors. It is hypothesized that a long-term aerobic environment is more likely to cause tuber rot, while an anaerobic environment is more conducive to maintaining tuber vitality.

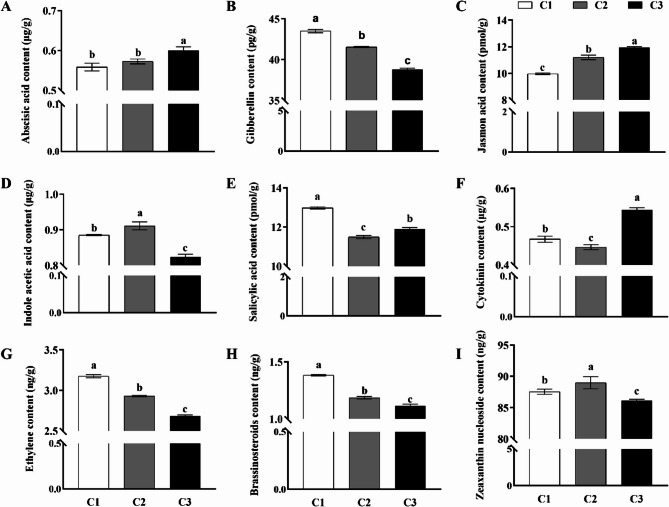

Regulatory roles of endogenous hormones in ecodormancy of tropical water lily tubers

Our differential gene expression analysis underscores the significant role hormonal pathways play in the development of the underground stem. To delve deeper, we analyzed the hormone content at various ecodormancy stages of tubers (Fig. 5). We noted distinct patterns in the accumulation of abscisic acid (ABA), gibberellins (GA), jasmonic acid (JA), indole-3-acetic acid (IAA), salicylic acid (SA), cytokinins (CTK), ethylene (ETH), brassinosteroids (BR), and zeatin riboside (ZR) throughout the ecodormancy phases.

Fig. 5.

Hormonal fluctuations across stages of tuber ecodormancy. This illustration provides a detailed examination of how hormone levels vary through the ecodormancy cycle of tubers, categorized into early ecodormancy (C1), mid-ecodormant (C2), and full ecodormancy (C3). The comprehensive graph delineates the shifts in levels of nine essential hormones: (A) Abscisic Acid (ABA), (B) Gibberellins (GA), (C) Jasmonic Acid (JA), (D) Indole-3-Acetic Acid (IAA), (E) Salicylic Acid (SA), (F) Cytokinins (CTK), (G) Ethylene (ETH), (H) Brassinosteroids (BR), and (I) Zeatin Riboside (ZR). Statistical significance is denoted by bars with different letters, indicating significant differences (P<0.05) according to Tukey’s multiple comparisons test.

The concentration of ABA remained unchanged between the onset and mid-ecodormancy but significantly increased during full ecodormancy (Fig. 5A). This pattern underscores ABA’s crucial role in ecodormancy maintenance. Conversely, GA content was highest at ecodormancy onset, lowest during full ecodormancy, and intermediate at the middle phase, with significant variations across stages (Fig. 5B). These observations are consistent with the ecodormancy-regulating roles of ABA and GA, where ABA promotes ecodormancy, and GA facilitates ecodormancy breakage.

The content of JA progressively increased with ecodormancy deepening, being lowest at the onset and highest during full ecodormancy, indicating its significant role in ecodormancy progression (Fig. 5C). The IAA content initially increased, then decreased, peaking during the mid-ecodormancy, suggesting its involvement in ecodormancy stage regulation (Fig. 5D). SA content was significantly higher at ecodormancy onset than at other stages, decreased in the middle phase, and then increased again during full ecodormancy (Fig. 5E), highlighting its complex role in ecodormancy and potentially in defense mechanisms.

CTK content displayed a decreasing trend from ecodormancy onset to the middle phase, followed by an increase during full ecodormancy (Fig. 5F). ETH content was significantly higher at ecodormancy onset, decreased in the middle stage, and was lowest during full ecodormancy (Fig. 5G). BR content decreased throughout the ecodormancy phases, with the highest at the onset and the lowest during full ecodormancy (Fig. 5H). Similarly, ZR content showed an increase followed by a decrease, with the highest levels observed during the mid-ecodormancy phase (Fig. 5I). These trends suggest a coordinated regulation of hormones during the ecodormancy phases.

Transcriptomic insights into the ecodormancy mechanisms of ‘Eldorado’

The formation of fully dormant tubers is crucial for enhancing the cold tolerance of tropical water lilies and facilitating their survival through winter in open ground conditions. To unravel the regulatory mechanisms underpinning different ecodormancy stages and to explore potential strategies for inducing ecodormancy through human intervention, we employed high-throughput sequencing technology to analyze transcriptomic dynamics across three distinct phases: initiation (Stage I), mid-ecodormancy (Stage II), and full ecodormancy (Stage III) (Fig. 1B). Following stringent quality control, we obtained over four hundred million high-quality clean reads (Table S1), with Q20 and Q30 values exceeding 97.29% and 92.89%, respectively (Table S2). The assembly yielded 68,530 unique genes with an N50 length of 8,544 bp and an average length of 1,256 bp, indicating a comprehensive coverage of the transcriptome.

Applying stringent criteria (FDR < 0.05 and |log2FC| >1), we identified 2,068 DEGs between Stage I and II, and 1,129 DEGs between Stage II and III (Fig. 6A; Table S3). Venn diagram analysis further revealed that 3,248 genes exhibited stage-specific expression patterns across all comparisons, whereas only 76 DEGs were shared among all stages (Fig. 6B), suggesting that these common DEGs may serve as core regulators orchestrating tuber dormancy transitions. To validate the accuracy of transcriptome sequencing, nine DEGs were selected for RT-qPCR analysis to assess the reliability and precision of the sequencing results. The validation results showed that the expression trends of these nine genes in RT-qPCR were highly consistent with the sequencing data (Fig. 6C).

Fig. 6.

Analysis of gene expression related to ecodormant phases. (A) Statistical representation of differentially expressed genes identified in direct comparisons among stage Ⅰ, stage Ⅱ, and stage Ⅲ. (B) Venn diagram highlighting the common and unique genes across stage Ⅰ, stage Ⅱ, and stage Ⅲ. (C) Validation of DEGs by RT-qPCR. (D)-(F) KEGG pathway enrichment analyses for stage comparisons (Stage Ⅰ vs. Stage Ⅱ, Stage Ⅱ vs. Stage Ⅲ, and Stage Ⅰ vs. Stage Ⅲ) depicted through bar charts, pinpointing the key biological pathways and processes that are activated or repressed during the transition through ecodormancy stages.

GO enrichment analysis was performed on these differential genes (Table S4). Among the top 20 significantly enriched GO annotations (Figures S1-S3), functional groups common to the three categories were statistically analyzed. This GO annotation result indicates a high involvement of genes in cellular component categories such as cell periphery, plasma membrane, and integral component of the membrane; and in the molecular function category, a significant number of genes involved in transcription factor activity.

KEGG pathway analysis of differentially expressed genes across developmental stages (Figs. 9D–F) showed that early ecodormancy is characterized by the enrichment of genes involved in plant hormone signaling, circadian rhythm, secondary metabolite biosynthesis, energy and carbohydrate metabolism, antioxidant defense, lipid metabolism, and cell wall modification. In contrast, during full ecodormancy, differentially expressed genes are predominantly associated with amino sugar and nucleotide sugar metabolism, sulfur and nitrogen metabolism, as well as vitamin biosynthesis. These findings indicate a functional shift from active growth and environmental adaptation in the early stage—mediated by hormonal regulation, metabolic adjustment, and stress response—toward the maintenance and optimization of metabolic homeostasis during deep dormancy, ensuring long-term survival under adverse conditions.

The progression towards deep dormancy was marked by pronounced shifts in gene expression profiles governing core physiological processes. A progressive suppression of energy metabolism emerged as a hallmark feature: respiratory chain genes were significantly downregulated during the transition from Stage I to III, culminating in near-complete inhibition of key mitochondrial complexes during full dormancy (COI (Cytochrome c oxidase subunit I), COII (Cytochrome c oxidase subunit II), COIII (Cytochrome c oxidase subunit III), ATP6 (ATP synthase F0 subunit 6): log2FC = −9.98 to −13.01). This metabolic downshift was accompanied by repression of glycolytic genes like GAPC (Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase, cytosolic) alongside upregulation of starch hydrolysis genes such as AMY1.1 (Alpha-amylase 1.1) (log2FC = + 6.62), signifying a strategic shift from rapid energy production to energy conservation.

Hormonal signaling networks underwent extensive remodeling throughout dormancy development. The abscisic acid biosynthetic gene NCED3 (9-cis-epoxycarotenoid dioxygenase 3) was consistently upregulated during both mid- and full-dormancy phases (Stage II: log2FC = + 1.55; Stage III: log2FC = + 1.63), while its receptor PYL4 (Pyrabactin resistance-like 4) was downregulated in full dormancy (log2FC = −1.22), establishing a “high hormone–low sensitivity” regulatory balance conducive to growth arrest. Simultaneously, gibberellin deactivation enzyme GA2OX8 (Gibberellin 2-beta-dioxygenase 8) exhibited progressively increased expression from Stage II to III (log2FC = −1.98 to −5.25), resulting in irreversible degradation of active GA species that further reinforced growth inhibition; additionally auxin transport carrier PIN5A (PIN-FORMED 5 A) was markedly suppressed during full dormancy (log2FC = −2.07), effectively blocking cell division signals.

The plant’s defense system displayed a hierarchical activation pattern corresponding with dormancy depth. In Stage II baseline protective mechanisms were initiated through upregulation of heat shock proteins such as HSP17.7 (Heat shock protein 17.7 kDa class I) (log2FC = + 2.72) and catalase CAT1 (Catalase 1) (log2FC = + 3.52). By Stage III defense strategies intensified toward specialized functions—HSP90AB1 (Heat shock protein 90-alpha B1) maintained protein homeostasis at elevated levels (log2FC = + 5.89); CAT2 (Catalase 2) mediated robust reactive oxygen species scavenging activity (log2FC = + 11.79); while transcription factors including WRKY76 (WRKY transcription factor 76) drove secondary metabolite biosynthesis via cytochrome P450 genes such as CYP82C4 (Cytochrome P450 family 82 subfamily C polypeptide 4) (log2FC = + 11.60) along with enhanced phenylpropanoid pathway activity.

Transitions between dormancy stages were marked by distinct molecular signatures. The shift from Stage I to II involved initial inhibition of respiratory chains along with ABA synthesis activation; transition from Stage II to III featured irreversible suppression of GA signaling via GA2OX8 upregulation, activation of starch hydrolysis by AMY1 induction, as well as inhibition of cell wall expansion protein EXPA8 (Expansin A8) (log2FC = −4.67). These coordinated events reflect orchestrated reprogramming involving metabolic adaptation from glycolysis toward starch hydrolysis for energy efficiency; hormonal balance shifts dominated by ABA/GA antagonism; together with enhancement of defense strategies evolving from baseline protection toward robust chemical defenses.

The elucidation of transcriptomic changes during ecodormancy formation in ‘Eldorado’ underscores not only complex regulatory mechanisms but also highlights how successful transition to full dormancy represents an interplay between genetic resilience and sophisticated responses to environmental cues at multiple molecular levels.

Environmental and hormonal regulation of tuber formation and ecodormancy in‘Eldorado’

Our findings highlight the significant impacts of environmental cues, including photoperiod and tissue damage, along with three plant hormones, including ABA, BR, and GA on the formation of dormant tubers in tropical water lilies. This provides a theoretical basis for artificially inducing ecodormancy. We explored the effects of photoperiod treatments, three practical damage treatments (leaf cutting, complete submersion, and salt stress), and various cultivation methods (soil, hydroponic, and sand culture) on tuber formation (Figure S4).

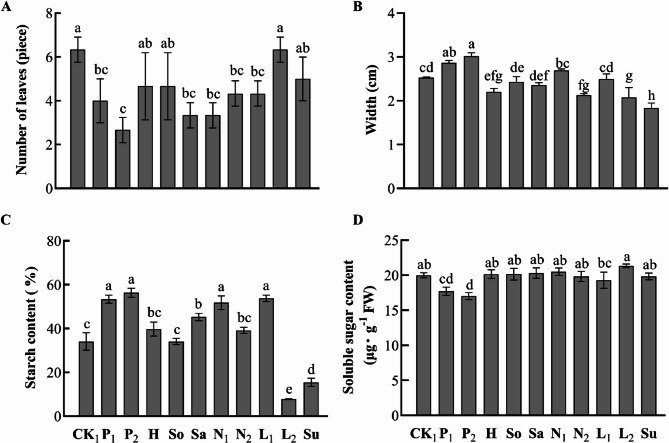

The number of leaves on the tubers of tropical water lilies after treatment indicates the extent of each treatment's impact on tuber development (Figure7A). Plants under control conditions and those subjected to complete leaf cutting showed a significantly higher number of leaves and buds compared to those under salt stress, sand culture, photoperiod treatments, and 50% leaf cutting. Notably, photoperiod treatment (10 h light/14 h dark) led to a significant reduction in leaf count compared to the control. Complete leaf cutting, and submersion treatments, demonstrating a 58% decrease relative to the control and complete leaf cutting conditions.

Fig. 7.

Impact of various treatments on the growth and development of ‘Eldorado’. Two-month-old water lily plants ‘Eldorado’ were subjected to various treatments, including control (CK1), photoperiod (P1: 5h light/19h dark, P2: 10h light/14h dark), hydroponic (H), soil culture (So), sand culture (Sa), salt stress (N1: 50 mmol·L-1, N2: 100 mmol·L-1), leaf pruning (L1: 50%, L2: 100%), and submergence (Su). Then, leaf number (A), tuber width (B), starch content (C) and sugar content (D) of different plants were analyzed. Statistical significance is denoted by bars with different letters, indicating significant differences (P<0.05) according to Tukey’s multiple comparisons test.

Furthermore, we assessed the effect of these treatments on tuber formation (Fig. 7B). Tuber width was similar between the two photoperiod treatments (10 h light/14 h dark and 5 h light/19 h dark), but significantly larger than that in tubers from other treatments. The smallest tuber width was observed in the submersion treatment, significantly smaller than in all other treatments, suggesting that the decrease in leaf number from photoperiod treatment was due to nutrient reallocation to the tuber for growth and development, rather than excessive stress.

In terms of starch content, tubers treated with 50 mmol·L−1 salt stress, short-day conditions, and 50% leaf cutting had significantly higher levels compared to other treatments, with no significant differences among them (Fig. 7C). This suggests that these treatments promote starch accumulation, facilitating tuber development. Different treatments induced variations in soluble sugar content, with short-day conditions significantly reducing soluble sugar levels compared to other treatments, indicating a transition from soluble sugars to starch conversion and metabolic consumption within the tubers under short-day conditions (Fig. 7D).

To verify the effect of plant hormones on the ecodormancy of tropical water lilies, we applied exogenous ABA, ETH, BR, and JA under short-day conditions to‘Eldorado’ (Figure 8). Compared to untreated controls (CK1) and those under short-day conditions (5 h light/19 h dark, CK2), tubers treated with hormones exhibited variable degrees of swelling, with the most pronounced swelling observed following low concentration ABA (50 μmol·L-1) and high concentration JA (100 μmol·L-1) treatments. Under short-day conditions, ABA-treated tubers had a relatively lower number of leaves, indicating a deeper ecodormancy, with low concentration ABA treatment producing tuber lengths 170% that of CK2. High concentration JA treatment significantly increased the length and mass of tubers compared to other treatments, with tuber length increasing from 147% to 200% of CK2 as the concentration of exogenous JA increased (Table S5). A comprehensive analysis from the perspectives of swelling and ecodormancy under short-day conditions indicates that low concentration ABA treatment is more conducive to inducing ecodormancy in tropical water lilies, whereas high concentration JA treatment is more beneficial for tuber swelling. Tubers treated with ABA had fewer leaves and exhibited deeper ecodormancy, maintaining the basic morphology of the untreated state. These results demonstrate that the combined application of JA (100 μmol·L-1) and ABA (50 μmol·L-1) under short-day conditions (5 h light/19 h dark) effectively promotes ecodormancy in tropical water lilies.

Fig. 8.

Growth characteristics of 'Eldorado' tubers under exogenous hormone treatments.Growth dynamics of underground stems in‘Eldorado’ following exogenous hormone application (ABA, ETH, BR, JA), comparing untreated control (CK1) and photoperiod-treated (CK2: 5h light/19h dark) plants.

Discussion

Tropical water lilies are vibrant jewels in aquatic landscapes, renowned for their colorful blossoms. In suitable environments, these plants can flourish year-round; however, in northern subtropical regions and areas further north, cold temperatures during winter can induce chilling and freezing injuries, potentially leading to the death of the entire plant and preventing successful overwintering in the field [22]. The tropical water lily variety ‘Eldorado’ can produce subterranean rhizomes as a means of enduring adverse conditions. Investigating the complex processes and molecular mechanisms underlying this phenomenon represents a compelling area for future research.

In our study, we utilized cytological observations, physiological assessments, and transcriptomic analyses to examine the multifaceted changes occurring in ‘Eldorado’ during its ecodormancy phase. Our results indicate that the fully dormant tubers of ‘Eldorado’ exhibit significant cold tolerance and growth potential. This enhancement is achieved through the efficient allocation of resources and morphological changes, characterized by an accumulation of starch, osmotic regulators, and antioxidant compounds. Moreover, plant hormone signaling pathways, activated in response to stress conditions such as limited nutrient availability and short photoperiods, play a critical regulatory role in these adaptive processes. The interplay of starch and sucrose metabolism pathways further contributes to the plant’s resilience against environmental stressors.

This study offers valuable insights into the adaptability and reproductive strategies of ‘Eldorado’. Notably, the seeds of ‘Eldorado’ can bloom within the same year of sowing in subtropical regions, indicating a rapid growth cycle, which may represent an evolutionary response to unpredictable environmental conditions. Unlike temperate species, ‘Eldorado’ does not develop tubers under optimal growing conditions. When faced with adversity, such as low temperatures or nutrient scarcity, the tuberless plant gradually enters a state of ecodormancy. The core process of this ecodormancy is marked by the gradual swelling of the subterranean rhizome (Fig. 1B). This ecodormant pattern bears similarities to that of certain tuberous plants [21], emphasizing the species’ adaptability and resilience through the transition from active growth to ecodormancy. Furthermore, the development of small, viable tubers on the dormant rhizome of ‘Eldorado’ represents an effective reproductive strategy, ensuring the species’ survival and propagation under adverse conditions. This strategy is particularly advantageous for tropical species, as it facilitates a rapid return to growth once favorable conditions re-emerge, highlighting the dynamic nature of its survival strategies. However, most tropical water lilies struggle to adapt to the temperature fluctuations characteristic of subtropical regions, entering ecodormancy before the onset of winter and forming swollen underground tubers. Promoting timely ecodormancy is crucial for the successful overwintering of tropical water lilies in outdoor environments within subtropical areas.

We investigated the effects of ecodormancy levels and storage conditions on the cold tolerance of ‘Eldorado’ through phenotypic observations and analyses of cold stress-related physiological parameters. The combined analysis of MDA levels and changes in relative electrical conductivity indicated that underwater storage enhances the cold tolerance of tubers in various states, with dormant tubers exhibiting greater cold resistance compared to those in a partially dormant state. Osmotic substances, such as proline and soluble proteins, accumulate significantly under low-temperature conditions, serving to protect cell structures. This accumulation helps clear ROS and reduces internal osmotic pressure, thereby mitigating damage [29].

Our results reveal that underwater storage, compared to aerated substrate storage, offers superior protection under cold conditions, reducing tuber damage and improving cold tolerance. Antioxidant enzymes are widely recognized as critical indicators of plant resistance due to their capacity to eliminate excessive ROS within the plant. The four antioxidant enzymes demonstrated varying activity trends under different treatment conditions, likely reflecting their distinct roles and mechanisms within the antioxidant defense system. The growth state of the tubers (i.e., partially dormant, dormant, or germinated) significantly influences variations in antioxidant enzyme activity. Partially dormant tubers generally exhibited greater sensitivity to low-temperature stress, while dormant and germinated tubers displayed enhanced antioxidant capacities. Different treatment methods, such as aerated substrate versus underwater storage, significantly affected the activity of antioxidant enzymes within the tubers. For instance, underwater storage appears to enhance antioxidant capabilities to a certain extent, particularly in dormant and germinated tubers. As the duration of cold stress extended, the activity of antioxidant enzymes displayed specific trends, illustrating the physiological adjustments and adaptations of the tubers under prolonged stress. In summary, dormant tubers exhibited superior cold resistance compared to those that were only partially dormant. Tubers stored underwater could withstand two months of low temperatures at 4 °C while still retaining vitality, enabling regrowth under appropriate conditions. This capacity suggests that ‘Eldorado’ possesses the ability to overwinter in the field. It is hypothesized that prolonged aerobic conditions may lead to tuber rot, whereas anaerobic environments are more conducive to maintaining the vitality of the tubers.

Combining anatomical structure analysis with starch content assessments, we discovered that starch metabolism plays a crucial role in the formation of dormant tubers in water lilies. Previous studies have indicated that starch metabolism significantly impacts both seed dormancy and tuber dormancy [31, 32]. Remarkably, as dormancy deepens, starch content tends to increase, aligning with findings from studies conducted on other plant species [33, 34]. Through transcriptomic analysis of tuber dormancy processes, we mapped starch synthesis and degradation pathways during ‘Eldorado’s ecodormancy (Figure S5). Genes associated with starch degradation, including Alpha-amylase 3 (AMY3) and Isoamylase (ISA), were downregulated, whereas key starch synthesis genes—Adenosine diphosphate glucose pyrophosphorylase (AGPase), Starch synthase (SS), and Starch branching enzyme (SBE)—were significantly upregulated. These findings align with previous studies [21, 35]. Additionally, in seeds undergoing dormancy release after GA3 treatment, the expression of Invertase (INV) was found to be upregulated. Conversely, a reduction in sucrose degradation can inhibit seed germination, which helps maintain the dormancy state [36, 37]. Thus, we hypothesize that the intensification of tuber ecodormancy is associated with the downregulation of INV1. Our study indicates a decline in INV1 expression from stage 1 to stage 3, which may correlate with the deepening of tuber ecodormancy. However, the specific relationship between starch synthesis genes and the ecodormancy of tropical water lilies requires further investigation.

The regulation of ecodormancy processes in plants is intricately linked to the functioning of various plant hormones [38]. Our study of the ‘Eldorado’ water lily has provided significant insights into the hormonal mechanisms involved in tuber ecodormancy, supported by transcriptomic analyses and hormone quantification across different ecodormancy stages (Figure S6). The identification of key signaling pathways associated with the hormonal regulation of ecodormancy is essential for understanding the developmental processes in these plants and offers potential strategies for exogenous treatments to optimize tuber formation.

Our findings suggest that the BR signaling pathway is activated during the transition from ecodormancy to sprouting. The initial activation of BR receptors leads to the subsequent engagement of the brassinosteroid signaling positive regulators BZR1 and BZR2. These transcription factors positively regulate downstream target genes, such as cyclin D3 (CYCD3), which is crucial for promoting cell division and growth during the sprouting process [39]. Notably, our data show that the levels of endogenous BR decline as ecodormancy progresses, which may result in diminished expression of brassinosteroid signaling positive regulator family proteins (BZR1/2) and CYCD3, thereby reinforcing ecodormancy. This aligns with previous reports that highlight the reduction of BR associated with tuber maturation and the suppression of BR-related gene expression under low-temperature conditions, emphasizing the hormone’s significant role in dormancy maintenance [40, 41]. In contrast, ABA emerges as a key player in enhancing dormancy across various plant organs. For instance, ABA synthesis is upregulated during the dormancy of grape buds [42], a trend consistent in our observations related to the ‘Eldorado’. The WRKY57 transcription factor’s notable upregulation under low-temperature conditions catalyzes the activation of the key ABA biosynthesis gene 9-cis-epoxycarotenoid dioxygenase 3 (NCED3), leading to increased ABA levels, which promotes tuber swelling while inhibiting GA signaling [43]. This ABA dynamic mirrors patterns observed in yam tubers, where ABA peaks in correlation with tuber swelling [44]. Conversely, GA is required for breaking dormancy, as elevated GA levels are linked to the dormancy release of various plant species [45]. Our investigation reveals a continuous decline in GA levels during the formation of water lily tubers, similar to findings in potato tubers, suggesting that reduced GA concentration is pivotal in tuber formation [46]. The interplay between GA synthesis regulatory genes, such as phytochrome B (PHYB) and the phytochrome-interacting factors (PIFs), under various light conditions further emphasizes the nuanced role of photoperiod in regulating GA levels and subsequently influencing dormancy [47]. Moreover, our study highlights the role of JA in the tuber formation process. Increases in JA synthesis as a response to biotic stress and tissue damage indicate its importance in promoting tuber development [48, 49]. Our data reveal that lipoxygenase (LOX) is significantly upregulated, driving JA production linked to metabolic pathways encompassing unsaturated fatty acids. The relationship between JA and other hormones, particularly in the context of environmental stressors, warrants further exploration to decipher their collective impact on tuber dynamics. Interestingly, the influence of ethylene remains controversial, as our findings indicate a decrease in ACO3 expression, leading to lower ethylene levels during tuber development. This observation suggests that ethylene may exert an inhibitory effect on tuber formation within the context of ‘Eldorado,’ aligning with reports that stress interactions influence hormone dynamics [50, 51].

Through this comprehensive study of ‘Eldorado’, we have elucidated the intricate interplay between environmental factors and intrinsic mechanisms governing growth, ecodormancy, and adaptability under the subtropical climate conditions of Nanjing, China (Fig. 9). The developmental dynamics of ‘Eldorado’, including changes in the structures of leaves, tuber development, and starch accumulation during ecodormancy, are closely associated with environmental cues, such as temperature and light. Timely entry into ecodormancy before winter is essential for the successful overwintering of tropical water lilies. Through high-throughput sequencing, we identified key hormonal pathways, including ABA, GA, JA, and BR, as well as external factors like photoperiod and injury, which play pivotal roles in regulating the ecodormant process. These hormones are crucial for adapting to environmental stresses, managing energy metabolism, and overseeing essential cellular functions. Furthermore, our findings reveal the significant impact of starch and sucrose metabolism on ecodormancy regulation, demonstrating a direct correlation between metabolic activity, gene expression, and the depth of ecodormancy. The feasibility of artificially inducing ecodormancy through various practical interventions, including different photoperiod treatments and induced stresses has been demonstrated. These discoveries not only contribute fundamentally to our understanding of plant ecodormancy but also have practical implications in horticultural practices, especially in enhancing the overwintering survival and reproductive capacity of tropical water lilies in non-native climates.

Fig. 9.

Schematic representation of the ecodormancy mechanisms in tropical water lilies.This figure illustrates the ecodormancy mechanism in tropical water lilies. Non-dormant tropical water lilies can enter ecodormancy under unfavorable environmental conditions, such as suboptimal light and temperature, to maintain the vitality of the plant and await suitable environmental conditions for germination. Environmental signals are sensed by various receptors and ultimately influence phytohormone signaling pathways. Through the action of transcription factors and epigenetic modification factors, plant hormone signals are integrated to regulate the expression of genes related to starch and sucrose metabolism, thereby inducing tuber development.

Materials and methods

Plant material and cultivation methods

This study utilized the tropical water lily cultivar Nymphaea ‘Eldorado’ (Martin E. Randig) as experimental material. Seedlings and seeds were obtained from the Hainan Tropical Herbaceous Flower Germplasm Resource Nursery, Waterlily Division, located in Sanya City, Hainan Province, China. Mature-stage seedlings were introduced in April to the Nanjing Agricultural University Baima Experimental Base in Nanjing, Jiangsu Province, China. Cultivation was conducted in an open-air environment with adequate ventilation, enclosed by perimeter fencing, and without overhead shading. The cultivation substrates included tap water (exposed to sunlight for 3 days), river sand (0.5–1.0 mm particle size), and garden soil (loam type). Prior to transplantation, damaged leaves from transportation were removed. Plants were initially potted in 380 mm-diameter grow bags, which were then placed into larger containers measuring 535 mm in diameter. A dynamic watering strategy was implemented based on transplanting stages: Initial transplant phase (low foliar coverage): Water level maintained 10 cm above bud points to minimize hydraulic resistance during leaf emergence. Growth phase: Gradual water supplementation to achieve full-container capacity (~ 20 cm above bud points), ensuring optimal hydration throughout developmental stages7. Water replenishment and removal of aquatic weeds, algae, and snails were performed every 3 days. All sampling was uniformly conducted between 9:30 to 11:00 AM to mitigate diurnal physiological fluctuations.

Experimental procedures for Germination, Growth, stress Induction, and phenotypic assessment in ‘Eldorado’

Seeds of ‘Eldorado’ were stored in sealed desiccants at 4 °C. In late March, seeds were germinated in 20 °C water [52]. Following germination, seedlings were photographed and transplanted into controlled optimal conditions (n = 50), with watering management mirroring mature plant protocols, implementing a progressive water level strategy from low to high. By June, plants exhibiting 3–5 floating leaves were randomly selected (n = 3) for photographic documentation after removal from containers. Flowering mature plants were similarly documented in July. To simulate adversity conditions, 30 randomly selected June-stage plants were transplanted into nutrient-deprived submerged soil. Biweekly photographic monitoring of randomly chosen specimens was conducted. In August, fully ecodormant tubers from adverse environments were harvested for imaging, then replanted into optimal conditions. Phenotypic recovery was photographically assessed two months post-transplantation.

Cytological observations

For cytological analysis, ecodormant tubers at various developmental stages were collected and immediately fixed in formalin-acetic acid-alcohol (FAA) solution [53]. Softening is performed using a plant softening agent (70% ethanol (v/v) : glycerin = 1:1) [54], and the plant softening agent is replaced every three days. When the scalpel blade can easily cut through the tissue, it indicates that the softening is complete. The dehydration process utilized a graded ethanol series (75%, 85%, 90%, 95%, and twice at 100%) to progressively eliminate water from the tissues. Following dehydration, the samples were infiltrated with 100% xylene and subsequently embedded in paraffin wax, preparing them for sectioning [55, 56]. Sections of 4 μm thickness were prepared using a microtome and mounted on glass slides for analysis. These sections were stained with the Periodic Acid-Schiff (PAS) method. Observations were made using an upright fluorescence microscope, facilitating an examination of cellular structures and the distribution of stained components within the ecodormant tubers.

Assessment of sprouting capacity and survival of Ecodormant tubers

Mid-ecodormant tubers, fully ecodormant tubers and tubers sprouting from ecodormancy were collected, washed to remove surface soil, and air-dried. Plant materials were maintained in darkness under two conditions: aerated environment and underwater. Low-temperature treatments were performed in plant growth chambers set to 4 °C. Sampling was conducted after 1, 2, 3, and 4 months of cold exposure to evaluate tuber status across ecodormancy phases and treatments.

Following sampling, tubers were transferred to suitable environment for sprouting observation, with germination rates recorded on day 7. To avoid cross-interference between sampling timepoints, four independent groups were established per ecodormancy state-treatment combination (12 containers per treatment, 24 total containers). All treatments were maintained at 4 °C (the average minimum winter pond-bottom temperature in Nanjing). Each treatment included five biological replicates, as specified in Table S6.

Measurement of physiological indices

Tubers collected in Sect. 4.3 were processed for physiological analysis based on our prior protocol [21] with optimizations for high-starch tissue homogenization. The black outer shells of tubers were removed, and the internal cream-colored tissues were excised for physiological index determination. Plant cell membrane permeability was assessed using an electrical conductivity method. The Coomassie Brilliant Blue method was employed to determine the content of soluble proteins. Proline content was measured via the sulfosalicylic acid method, while malondialdehyde (MDA) content was ascertained using the thiobarbituric acid (TBA) method. Superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity was quantified with the nitroblue tetrazolium (NBT) method. Peroxidase (POD) activity was assessed using the guaiacol method, and catalase (CAT) activity was determined through the hydrogen peroxide method. Soluble sugars content was measured using the anthrone colorimetric method. and starch content was determined with a commercial assay kit from Sigma-Aldrich.

Determination of plant hormone levels

Samples for hormone quantification consisted of the apical portions (with black outer shells removed) of water lily tubers at initial ecodormancy (Stage I), mid-ecodormancy (Stage II), and full ecodormancy (Stage III), with three biological replicates per group. The quantification of hormones, including gibberellins (GA), jasmonic acid (JA), abscisic acid (ABA), ethylene (ETH), salicylic acid (SA), indole-3-acetic acid (IAA), cytokinins (CTK), brassinosteroids (BR), and zeatin riboside (ZR), was conducted using assay kits (Yafei Biotechnology) [21].

Transcriptome sequencing and analysis

Tuber apex tissues (with black outer shells removed) at three ecodormancy stages — initial ecodormancy (stage I), mid-ecodormancy (stage II), and full ecodormancy (stage III) — were flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen. Three biological replicates per stage were established, yielding nine total samples. Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol® reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). RNA integrity was verified using an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA, USA), followed by transcriptome sequencing on the Illumina Novaseq6000 platform at Gene Denovo Biotechnology Co. (Guangzhou, China). Raw sequencing reads were processed through the following quality control pipeline using fastp (v0.18.0): Removal of adapter-containing reads, exclusion of reads with >10% unknown nucleotides (N), and elimination of low-quality reads containing >50% bases with Phred scores ≤ 20. Ribosomal RNA (rRNA) depletion was performed by aligning reads to the SILVA rRNA database using Bowtie2 (v2.2.8). Transcriptome assembly was performed de novo using Trinity (v2.2.0) [57]. The pipeline processes short-read sequencing data through its modular workflow, ultimately reconstructing full-length transcript sequences under default parameters.

Expression levels for these unigenes were calculated and normalized as RPKM (Reads Per Kilobase per Million mapped reads). Basic functional annotation involved BLASTx searches (E-value ≤ 1e⁻⁵) against NCBI nr, Swiss-Prot, KEGG, and COG/KOG databases for protein function, pathway, COG/KOG, and GO assignments. Sample relationships were assessed via correlation analysis of replicates and principal component analysis (PCA). Differential expression analysis (FDR < 0.05, |log₂FC| ≥ 1) was conducted using DESeq2 [58] (group comparisons) and edgeR [59] (sample comparisons). Functional enrichment of DEGs for GO terms and KEGG pathways was performed using hypergeometric testing (FDR ≤ 0.05). Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) [60] with MSigDB [61] identified enriched functional categories. Protein-protein interaction networks were constructed using STRING v10 [62] and visualized in Cytoscape v3.7.1 [63] to identify hub genes.

Ecodormancy induction treatments in nymphaea ‘Eldorado’

The experiment was conducted in June 2020 at the Baima Experimental Base of Nanjing Agricultural University, where the monthly average temperature during June in Nanjing approximates 25.4°C. Mature plants of Nymphaea ‘Eldorado’ (see Sect. 4.1 for cultivation details), which were introduced and transplanted in April, were selected for treatment. Plants with comparable growth vigor were subjected to the following ecodormancy induction protocols, with five biological replicates per treatment as detailed in Table S7: (1) Photoperiod Treatment: Plants were subjected to three distinct lighting conditions: a control (CK) with a 12-hour light/12-hour dark cycle, and two photoperiod treatments (10 hours light/14 hours dark and 5 hours light/19 hours dark), utilizing double-layer blackout cloth to enforce short-day conditions. The Short-day 1 treatment lasted from 8:00 to 18:00, while Short-day 2 extended from 8:00 to 13:00. (2) Submergence Treatment: The entire plants were submerged underwater, held down by mesh bags filled with stones. (3) NaCl Stress: The plants experienced two levels of salt stress, achieved by substituting the water in the pots with sodium chloride solutions at concentrations of 50 and 100 mmol·L-1. (4) Leaf Pruning: This involved two levels of pruning, where 50% and 100% of the floating leaves of ‘Eldorado’ water lilies (All floating leaves were removed throughout the experimental period, with newly developing submerged leaves retained) were removed. (5) Nutrient Stress: All plants were accommodated in smaller containers with a 25 cm top diameter. The treatments included growing them in various mediums: water, sand, and soil. In water-based cultivation, large stones secured the plants’ submerged parts to prevent them from floating. This methodical approach to inducing ecodormancy through various environmental stresses was designed to explore their impacts on the ecodormancy phases of the tropical water lily, offering valuable insights into the physiological and molecular mechanisms that govern plant ecodormancy.

Not fully mature ‘Eldorado’ plants with 3–5 expanded floating leaves were selected for exogenous hormone treatments. Individual plants were potted in nutrient pots containing 15 L deionized water, with three biological replicates per treatment. Cultivation was conducted in plant growth chambers under a programmed regime: Phase 1: 5 h light (20,000 lx) at 21 °C, Phase 2: 19 h darkness (0 lx) at 21 °C. The treatments involved abscisic acid (ABA), ethylene (ETH), brassinosteroids (BR), and jasmonic acid (JA), with the plants immersed in solutions at specified concentrations. The hormone concentrations were as follows: ABA at 50 µmol·L-1 and 100 µmol·L-1; ETH at 1.7 mmol·L-1 and 8.3 mmol·L-1; BR at 1.25 µmol·L-1 and 2.5 µmol·L-1; and JA at 50 µmol·L-1 and 100 µmol·L-1. Tuber growth status was examined seven days post-treatment.

Statistical analysis

Inter-group comparisons were performed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), with all data presented as mean ± standard error (SE). Each group included at least three independent biological replicates. When the ANOVA indicated statistical significance (P < 0.05), Tukey’s multiple comparison test was used for pairwise comparisons among groups. All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS 18.0 (IBM Corp.), and graphical representations were generated with GraphPad Prism 9.0 (GraphPad Software). A summary of the ANOVA results for each figure is provided in Table S8.

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Material 1: Figure S1. Gene Ontology enrichment circular plot of differentially expressed genes between Stage I and Stage II. Figure S2. Gene Ontology enrichment circular plot of differentially expressed genes between Stage I and Stage III. Figure S3. Gene Ontology enrichment circular plot of differentially expressed genes between Stage II and Stage III. Figure S4 Impact of varied treatments on growth and development of ‘Eldorado’. Figure S5 Regulation of starch metabolism pathways during the formation of dormant tubers. Figure S6 Plant hormone-regulated signaling pathways in the formation of dormant tubers. Table S1 Data filtering statistics. Table S2 Statistics of reads. Table S3 RNA-Seq Gene Expression Matrix. Table S4 KEGG pathway enrichment analyses of different comparisons. Table S5 Morphological responses of tubers to exogenous hormone treatments. Table S6 Treatment groups of tropical water lily 'Eldorado' tubers. Table S7 Treatment to induce dormancy in tropical water lilies 'Eldorado'. Table S8 One-Way ANOVA summary.

Acknowledgements

We thank all members of our laboratory for their valuable discussions and technical assistance during this study.

Authors’ contributions

C.H. and R.Z. contributed to the overall conception and design of the study, as well as the acquisition and analysis of data. C.Y., C.H. and R.Z. drafted the manuscript and performed initial data analysis. Y.L. provided support in data interpretation, while K.L. contributed to the experimental design and data collection. Y.W. assisted in data processing and analysis, offering critical insights into the results. Y.X. developed and optimized the software used in the research, and Q.J. played a key role in revising the study proposal. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript and have agreed to be accountable for their contributions to the work.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (no. 32471949; U2003113; U1803104); China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2505BSHJJ); A Project Funded by the Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions.

Data availability

The raw sequence data reported in this paper have been deposited in the Genome Sequence Archive in National Genomics Data Center, China National Center for Bioinformation/Beijing Institute of Genomics, Chinese Academy of Sciences (GSA: CRA027664) that are publicly accessible at https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/gsa/browse/CRA027664.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not Applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Chen Huang, Ran Zhang and Chunxiu Ye contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Yamane H, Singh AK, Cooke JE. Plant dormancy research: from environmental control to molecular regulatory networks. Tree Physiol. 2021;41(4):523–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]