Abstract

Group II introns are well recognized for their remarkable catalytic capabilities, but little is known about their three-dimensional structures. In order to obtain a global view of an active enzyme, hydroxyl radical cleavage was used to define the solvent accessibility along the backbone of a ribozyme derived from group II intron ai5γ. These studies show that a highly homogeneous ribozyme population folds into a catalytically compact structure with an extensively internalized catalytic core. In parallel, a model of the intron core was built based on known tertiary contacts. Although constructed independently of the footprinting data, the model implicates the same elements for involvement in the catalytic core of the intron.

Keywords: catalysis/hydroxyl radical footprinting/molecular modeling/RNA folding/structure

Introduction

Group II self-splicing introns are among the largest known catalytic RNA molecules. They range from 500 to >1000 nucleotides (nt) in length, and are second only to rRNAs in size. There are several lines of structural and mechanistic evidence that suggest a strong evolutionary link between group II introns and the eukaryotic spliceosome (Madhani and Guthrie, 1992; Sun and Manley, 1995; Sontheimer et al., 1999). However, these autocatalytic introns are also complex enzymes capable of performing a variety of reactions, including self-splicing (Perlman et al., 1986; Michel and Ferat, 1995), RNA and DNA hydrolysis (Jacquier and Michel, 1990; Griffin et al., 1995; Podar et al., 1995b) and intron mobility into RNA or DNA substrates (Zimmerly et al., 1995; Cousineau et al., 2000). Owing to their size and catalytic complexity, group II introns provide a rich model for studying RNA structure and function in a complex, yet tractable system. Further progress in characterizing (and potentially exploiting) their complex catalytic repertoire will depend on the development of a framework for describing the architectural organization of group II intron tertiary structure.

Despite a relative lack of sequence conservation among these introns, they all possess a conserved organization of six domains, which contain well-defined secondary structural elements (Michel et al., 1989). The modularity of group II intron domains has facilitated the development of numerous multicomponent systems for studying the functions of specific domains and the kinetics of individual group II intron reactions (Jarrell et al., 1988; Suchy and Schmelzer, 1991; Pyle and Green, 1994; Chin and Pyle, 1995; Costa and Michel, 1995; Michels and Pyle, 1995; Podar et al., 1995a). These systems have led to the characterization of numerous long-range tertiary interactions, particularly between catalytically essential domains 1 and 5 (D1 and D5) (Koch et al., 1992; Michels and Pyle, 1995). The first inter-domain tertiary interaction to be discovered (ζ–ζ′) was identified by phylogenetic and mutational analysis (Costa and Michel, 1995, 1997). Since then, significant progress has been made in uncovering other catalytically relevant tertiary interactions, particularly in the context of intron ai5γ (Michel and Ferat, 1995; Qin and Pyle, 1998). Cross-linking studies have implicated a contact between stem 1 of catalytic domain D5 and the J2/3 region that helps specify the 3′ splice site (Podar et al., 1998). Modification interference and footprinting approaches have mapped sites of interaction between D5 and the rest of the ai5γ intron (Jestin et al., 1997; Konforti et al., 1998b), thereby defining a functional ‘core’ of the active molecule. Finally, ‘chemical genetics’ methods have been used to elucidate and describe two new long-range tertiary interactions (κ–κ′ and λ–λ′) between D5 and regions of D1 that help compose the intron active site (Boudvillain and Pyle, 1998; Boudvillain et al., 2000). These and other catalytically important inter-domain contacts have provided valuable structural constraints. However, a global understanding of intron architecture requires information on the simultaneous spatial arrangement of all intronic residues, and this information cannot be obtained using the sequence- and domain-specific approaches that have been applied previously to study group II introns.

Group II introns such as ai5γ may not seem likely candidates for forming compact, folded enzymes. Their large size, together with a tendency for high salt requirements and an unusually large fraction of A–U base pairs, would seem to indicate that these RNAs might assume extended, dynamic conformations (Costa et al., 1997b). Further complicating structural analysis, the important architectural elements are widely dispersed throughout an extended secondary structure (Qin and Pyle, 1998). This presents a rather different ‘core’ arrangement from that found in other large RNAs such as the group I introns and RNase P (Cech, 1988; Nolan and Pace, 1996), where functionally important elements are both highly conserved and in relatively close proximity. The seemingly scattered organization of group II intron motifs suggests the potential for a more open, loosely packed superstructure.

To address these issues, a homogeneously folded ribozyme derivative of group II intron ai5γ was probed using hydroxyl radical cleavage, which revealed the relative solvent accessibility of each position along the ribozyme backbone. The data indicate that the ribozyme has an extensively internalized core that contains the majority of known catalytically essential tertiary interactions. In parallel, a three-dimensional model of the intron core was built using known long-range tertiary interactions. Although the model was derived independently of the hydroxyl radical footprinting experiments, both studies identify the same structural elements packed in the heart of the group II intron active site.

Results and discussion

A folded construct for exploring the group II intron active site

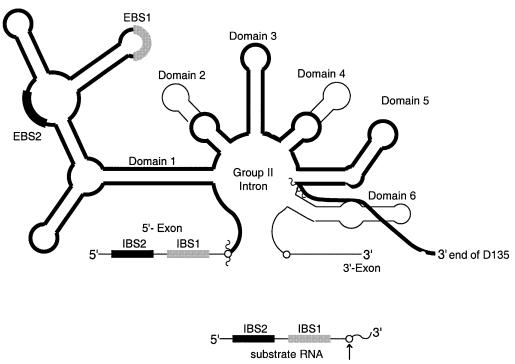

In order to study a single, defined conformation of the active intron, a ribozyme deletion construct was created. This molecule, consisting of domains 1, 3 and 5 and requisite joiner regions (D135; Figure 1), is a highly reactive endonuclease that contains all the components previously shown to contribute to the intron active site (Griffin et al., 1995; Michels and Pyle, 1995; Xiang et al., 1998). The molecule catalyzes only a single reaction rather than multi-step processes such as splicing, which may involve distinct intron conformations at different points along the reaction pathway (Chanfreau and Jacquier, 1996). Specifically, D135 cleaves short oligonucleotides that are complementary to its exon binding sequences (EBS1 and 2).

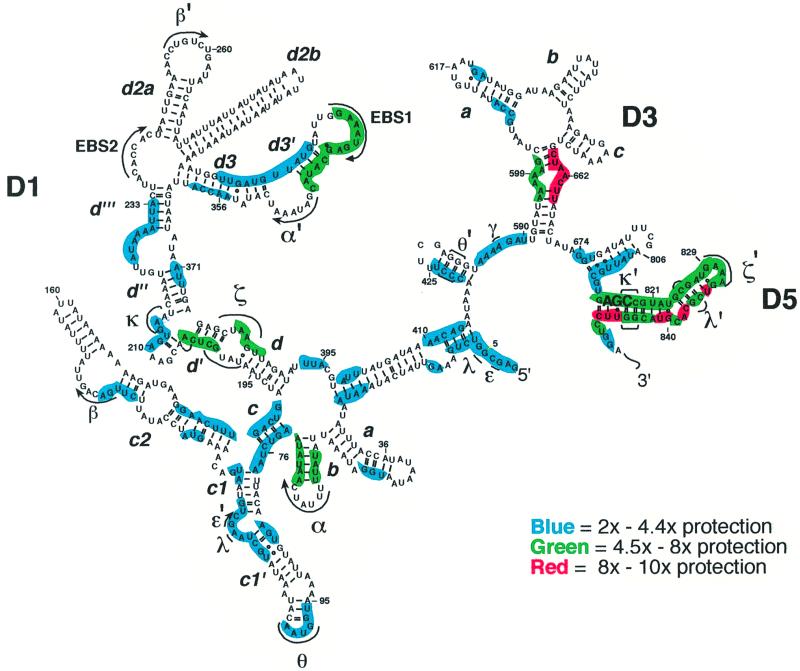

Fig. 1. Schematic secondary structure of the D135 ribozyme. D135 (heavy dark line) is comprised of domains 1, 3 and 5 of group II intron ai5γ; domains 2 and 4 have been replaced by hairpins and linker regions have been maintained. The 24 nt oligonucleotide substrate contains 17 nt of the 5′-exon sequence (including both intron binding sites, IBS1 and 2) and the first 7 nt of the intron.

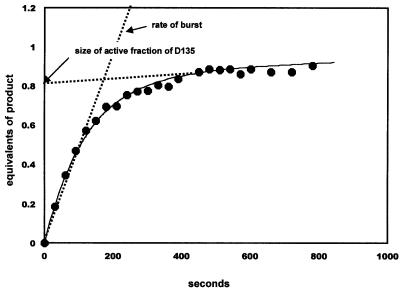

Ribozyme D135 carries out a hydrolytic, rather than a branching reaction, which facilitates multiple turnover experiments that are required for optimizing and determining the fraction of active molecules. These experiments help to establish the existence of a conformationally homogeneous population, which is important for the interpretation of subsequent footprinting studies. A classic test for determining the fraction of active (and thereby folded) enzyme molecules is to conduct active- site titration experiments (Fersht, 1985) (Figure 2). Typically, these experiments are conducted under multiple turnover conditions where product release is rate limiting for the overall reaction and the rate of chemistry is relatively fast. When enzyme is added to an excess of substrate, the first turnover of reaction results in a burst of product formation, which is followed by a slower phase involving product release. The relative fraction of active molecules is determined by measuring the magnitude of the initial catalytic burst. For D135 at 42°C, 83 ± 5% of the population is active under standard conditions (Figure 2; 100 mM MgCl2 and 500 mM KCl pH 7.0, initiated as described in Materials and methods). The burst rate (0.48 ± 0.10 min–1) is equivalent to the single turnover rate for this reaction (L.J.Su, unpublished results), indicating that the burst population represents the most active state of the ribozyme.

Fig. 2. Active-site titration of the D135 ribozyme. Product formation was plotted as a function of time, in order to reveal the relative rates of the burst and steady state. The two phases of reaction were determined from the fit to equation 1 (Materials and methods). The fraction of active ribozyme molecules is determined from the intercept of the second phase with the y-axis. Reaction parameters reflect the average of three independent experiments.

Hydroxyl radical footprinting of a group II intron ribozyme

Having established an appropriate construct and the ionic conditions required for its folding, hydroxyl radical footprinting experiments were initiated. Hydroxyl radicals cleave RNA or DNA by extracting a proton from one of the sugar carbons, preferentially at the C5′ or C4′ positions (Balasubramanian et al., 1998). They provide a probe of solvent accessibility as they are small, highly reactive, and relatively insensitive to primary sequence and secondary structure (Dixon et al., 1991). This technique was first used to establish the ‘inside’ and ‘outside’ of a group I intron ribozyme (Latham and Cech, 1989; Celander and Cech, 1991), and has since proven to be a valuable tool for defining the core architecture of many other RNA constructs (Murphy and Cech, 1993; Pan, 1995; Cate et al., 1996; Shelton et al., 1999).

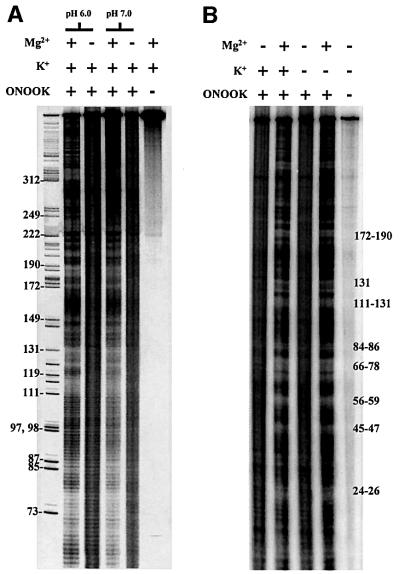

The size of group II intron ribozymes presented the largest obstacle to initial footprinting attempts. Molecules of this length had not previously been directly footprinted with hydroxyl radicals, as large RNAs are exceptionally sensitive to background cleavage. To eliminate background degradation of D135, variables such as pH, handling time and temperature were optimized for the preparation and handling of the end-labeled RNA (Figure 4A; see Materials and methods). Signal-to-noise was further reduced by using peroxynitrous acid as the footprinting reagent (Gotte et al., 1996). Decomposition of the conjugate acid provides a single burst of radical generation that is complete in a matter of seconds (Beckman et al., 1990), therefore requiring only one reagent for initiating and terminating the footprinting reaction (Chaulk and MacMillan, 2000). Identical results were obtained using Fe(EDTA) to generate hydroxyl radicals (data not shown), but experiments were more cumbersome and the noisier data more difficult to quantitate.

Fig. 4. Effect of pH and KCl on footprinting patterns. Hydroxyl radical accessibility of D135 is compared at pH 6 and 7 (A) and in the presence and absence of 0.5 M KCl (B).

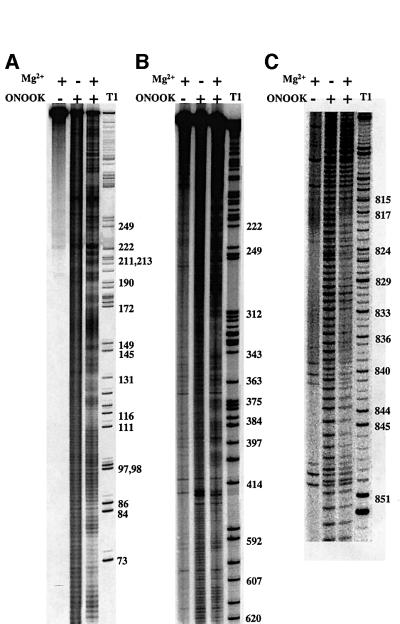

To determine whether a well defined pattern of solvent accessibility could be observed, 5′-end-labeled D135 was folded in the presence of MgCl2 and then subjected to footprinting with peroxynitrous acid. Surprisingly, sharp patches of hydroxyl radical protection were observed throughout the D135 structure, resulting in highly reproducible patterns (Figure 3). Overall, ∼40% of the nucleotides in D135 experience a >2-fold protection upon folding, which is a relatively large magnitude of protection when compared with the solvent accessibility of tRNA (10%) (Latham and Cech, 1989) or the RNA component of either Escherichia coli or Bacillus subtilis RNase P (17 or 34% above 1.5-fold protection, respectively) (Pan, 1995), and comparable to that of the highly internalized Tetrahymena ribozyme derived from a group I intron (40%) (Latham and Cech, 1989). This finding is particularly significant considering the size of the D135 RNA and previous concerns about the stability of ai5γ intron tertiary structure (Costa et al., 1997b).

Fig. 3. Equilibrium footprint of the D135 ribozyme. D135 samples were labeled on the 5′− (A) or 3′-end (B and C) to examine the solvent accessibility of all nucleotides in the ribozyme. In this manner, D1 (A and B), D3 (B) and D5 (C) were all visualized. Samples were incubated in the presence or absence of 100 mM MgCl2, and then footprinted with potassium peroxynitrite (ONOOK; Materials and methods). T1 nuclease, which cleaves at G residues, provides a reference ladder (right-hand lanes).

There are 32 discrete regions of protection that vary widely in their degree of solvent inaccessibility (Figures 3 and 5; Tables I and II). Although these regions occupy each domain of the D135 construct, there seem to be five main foci of internalization (Figure 5): the five-way helical junction of D1 (approximately nt 26), the three-way junction near nt 200 of D1, the area surrounding the first exon binding site (EBS1), the stem–loop structure at the base of D3, and D5. Strikingly, protected regions contain all of the known tertiary contacts between D1 and D5 (Costa and Michel, 1995; Jestin et al., 1997; Boudvillain and Pyle, 1998; Boudvillain et al., 2000), which are the only domains that are absolutely essential for the ai5γ active site (Koch et al., 1992; Michels and Pyle, 1995). In addition, the major foci for hydroxyl radical protection in D1 are all ‘hotspots’ for the footprinting of D5 onto D1, as determined by dimethyl sulfate (DMS) modification experiments (Konforti et al., 1998b). Taken together, these data suggest that D5 and its binding site in D1 comprise much of the intron core.

Fig. 5. Solvent accessibility map of D135. Regions of D135 that are protected from hydroxyl radical cleavage are mapped onto a secondary structural representation of the ribozyme. The degree of protection for each (Tables I and II) is indicated by the color code. Pairs of Greek letters correspond to known positions of tertiary interaction referred to in the text. Upper case Roman letters indicate domains of the ribozyme. Lower case Roman letters (and primes) indicate substructural helices within individual domains.

Table I. Extent of hydroxyl radical protection in D1–D3.

| Region | Positions | Fold protection |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1–8 | 2.5 ± 0.8 |

| 2 | 13–14 | 2.2 ± 0.4 |

| 3 | 24–26 | 2.1 ± 0.3 |

| 4 | 45–47 | 2.3 ± 0.4 |

| 5 | 56–59 | 5.5 ± 0.8 |

| 6a | 66–71 | 4.8 ± 0.5 |

| 6b | 72–77 | 4.3 ± 0.4 |

| 7 | 84–86 | 3.0 ± 0.4 |

| 8 | 96–101 | 1.8 ± 0.3 |

| 9 | 110–116 | 2.5 ± 0.4 |

| 10 | 121–122 | 3.5 ± 0.5 |

| 11 | 129–131 | 3.1 ± 0.6 |

| 12 | 141–143 | 3.1 ± 0.4 |

| 13 | 178–189 | 2.5 ± 0.5 |

| 14 | 198–203 | 5.0 ± 1.2 |

| 15 | 209–213 | 2.5 ± 0.8 |

| 16 | 224–232 | 2.1 ± 0.8 |

| 17 | 312–324 | 3.5 ± 0.6 |

| 18 | 330–342 | 5.6 ± 1.8 |

| 19 | 355–359 | 2.5 ± 1.2 |

| 20 | 371–373 | 3.9 ± 1.3 |

| 21 | 382–386 | 5.0 ± 0.9 |

| 22 | 393–395 | 2.5 ± 0.7 |

| 23 | 399–401 | 4.4 ± 1.1 |

| 24 | 410–415 | 4.1 ± 0.8 |

| 25 | 421–424 | 3.5 ± 0.7 |

| 26 | 584–590 | 3.7 ± 0.5 |

| 27 | 596–601 | 4.4 ± 0.9 |

| 28 | 607–610 | 3.1 ± 0.7 |

| 29 | 620–621 | 3.3 ± 0.4 |

| 30 | 659–665 | 7.4 ± 1.9 |

| 31 | 674–676 | 3.2 ± 0.6 |

| 32 | 807–852 | see Table II |

The positions and relative degree of protection are indicated at each site of footprinting. The variances shown represent the standard deviation in individual values for degree of protection, as determined from three separate footprinting experiments. The variances show that there is a reproducible hierarchy of cleavage suppression in different regions of D135 upon folding. Although factors such as local changes in backbone conformation (Price and Tullius, 1993), as well as the dynamics of a given region of the molecule, can affect hydroxyl radical accessibility, this initial analysis assumes that the major factor that contributes to relative protection is the degree of internalization within a folded molecule.

Table II. Extent of hydroxyl radical protection in D5.

| Base No. | Fold protection | Base No. | Fold protection |

|---|---|---|---|

| 807 | 1.6 ± 0.3 | 830 | 6.1 ± 0.8 |

| 808 | 2.4 ± 0.5 | 831 | 5.5 ± 0.4 |

| 809 | 2.7 ± 0.5 | 832 | 4.8 ± 0.4 |

| 810 | 2.5 ± 0.4 | 833 | 7.4 ± 0.6 |

| 811 | 2.5 ± 0.5 | 834 | 9.3 ± 2.0 |

| 812 | 2.9 ± 0.7 | 835 | 6.7 ± 0.6 |

| 813 | 3.5 ± 0.6 | 836 | 7.1 ± 1.2 |

| 814 | 4.3 ± 0.5 | 837 | 8.4 ± 1.0 |

| 815 | 5.6 ± 0.8 | 838 | 8.7 ± 0.9 |

| 816 | 7.9 ± 0.8 | 839 | 6.9 ± 1.2 |

| 817 | 6.9 ± 1.2 | 840 | 8.5 ± 0.9 |

| 818 | 7.7 ± 2.0 | 841 | 9.1 ± 1.4 |

| 819 | 7.6 ± 1.8 | 842 | 5.9 ± 0.5 |

| 820 | 6.5 ± 0.9 | 843 | 5.3 ± 0.6 |

| 821 | 5.2 ± 0.7 | 844 | 5.5 ± 0.8 |

| 822 | 4.4 ± 0.5 | 845 | 7.5 ± 1.5 |

| 823 | 4.9 ± 0.4 | 846 | 8.5 ± 1.9 |

| 824 | 4.8 ± 0.5 | 847 | 9.7 ± 2.1 |

| 825 | 6.1 ± 0.6 | 848 | 8.5 ± 1.4 |

| 826 | 6.3 ± 0.9 | 849 | 5.8 ± 0.7 |

| 827 | 8.0 ± 0.9 | 850 | 5.3 ± 0.8 |

| 828 | 6.1 ± 0.5 | 851 | 2.7 ± 0.6 |

| 829 | 6.3 ± 0.8 | 852 | 2.4 ± 0.6 |

The relative degree of protection for each nucleotide within D5 is shown.

The degree of protection was found to vary substantially throughout the D135 ribozyme (Tables I and II). Many internalized regions are cleaved 2- to 4-fold less than the unfolded control samples, although protection can be as much as 10-fold in certain regions (Table II). For example, D5 is highly protected at every position along its length (Figures 3 and 5; Table II), indicating that it is engulfed by the rest of the ribozyme. This provides structural evidence for the longstanding belief that D5 is the effective heart of a group II intron (Chanfreau and Jacquier, 1994; Peebles et al., 1995; Abramovitz et al., 1996; Konforti et al., 1998a). Although most of D3 is exposed to solvent, it contains a single section of markedly strong protection, which is consistent with a specific role for this domain as a catalytic effector in the active site (Podar et al., 1995a; Xiang et al., 1998) (Table I; Figure 5). D1 serves many functions in the group II intron, which include the binding of substrate (Jacquier and Rosbash, 1986; Jacquier and Michel, 1987), the formation of a folding scaffold (Qin and Pyle, 1997) and the contribution of key active-site elements (Chanfreau and Jacquier, 1994; Boudvillain and Pyle, 1998). It is therefore not surprising that the degree of protection in D1 is particularly variable, ranging from 2- to 8-fold (Figure 3; Table I).

Only one large region of D135 stands out as completely accessible in the folded molecule: nt positions 232–312. This is consistent with the role of β–β′ as a peripheral folding domain that is less well conserved than many other tertiary interactions (Michel and Ferat, 1995), as well as the fact that helix d2b can be deleted without effects on the rate of self-splicing of the intron (V.Chu, unpublished results).

Analysis of individual footprinting patterns

Regions that contribute to substrate or 5′-exon recognition. EBS1 and its flanking helix are buried to a larger extent than most of D1, suggesting that this section of the substrate binding site is positioned within the catalytic heart of the molecule. In contrast, the EBS2 element and its immediate flanking regions are completely exposed. These data are consistent with findings suggesting that EBS1 is the more important of the two elements, being involved in all reactions catalyzed by group II introns of any class (Michel et al., 1989; Cousineau et al., 2000). Notably, the protection patterns in EBS1 and EBS2 undergo only minor variations when bound to substrates containing the IBS1- and IBS2-binding sites. This suggests that the EBS regions are already structurally pre-organized for binding incoming substrate (or exon) RNA, in agreement with fluorescence studies on D1 folding (Qin and Pyle, 1997). However, definitive analysis of conformational change upon substrate and exon binding awaits more detailed studies of the EBS1 and EBS2 regions, together with hydroxyl radical protection experiments on intron constructs that contain a 5′-exon in cis.

The α–α′ interaction is a catalytically essential part of D1 (Harris-Kerr et al., 1993) that is highly conserved (Jacquier and Michel, 1987) and is believed to play a role in proper formation of the substrate binding site (Harris-Kerr et al., 1993; Qin and Pyle, 1997). Protection in this region shows a curious pattern that becomes clear only when considering the three-dimensional model of the intron core (see below). Notably, the α–α′ element itself appears to be solvent accessible (Figures 3 and 5). However, the immediate upstream region that flanks the α′ region is among the most highly protected regions in the intron. Likewise, the helical stem leading to the α element is highly protected. These findings suggest that, while the α–α′ element itself is externalized, it orients two flanking helices that are important elements buried in the catalytic core.

Protected regions between D2 and D4. Although most of D2 is functionally dispensable for catalysis, its proximal stem (positions 422–423 of the D135 ribozyme) functions as a receptor for a tetraloop located in the c1′ region (positions 98–101) of D1, forming the Θ–Θ′ interaction (Costa et al., 1997a). Both components of the Θ–Θ′ interaction contain light regions of protection.

A particularly significant region of internalization is the linker element that connects D2 and D3 (positions 584–590; J2/3). These nucleotides are phylogenetically conserved (Michel et al., 1989) and highly sensitive to mutagenesis (Podar et al., 1998). Cross-linking studies have demonstrated that this region lies in close proximity to nucleotides in stem 1 of D5, thereby implicating J2/3 as an important constituent of the active site (Podar et al., 1998). This is consistent with the finding that linker nucleotide A587 is one of the strongest metal ion binding sites within the intron (Sigel et al., 2000). The J2/3 nucleotides are important for the catalytic efficiency of ribozymes derived from the ai5γ group II intron (O.Fedorova, unpublished results), and they play a role in recognition of the 3′-splice site through formation of the γ–γ′ interaction that links position 587 with position 887 at the terminus of the intron (Jacquier and Michel, 1990).

The phylogenetically conserved stem–loop at the base of D3 contains one of the most highly internalized portions of the ribozyme (positions 659–665; Table I). This region is known to be important for intronic function from diethylpyrocarbonate interference (Jestin et al., 1997), DMS interference (A.DeLencastre, unpublished results) and nucleotide analog interference mapping studies (Boudvillain and Pyle, 1998), as well as ribozyme studies indicating that it enhances the rate of the chemical step (Griffin et al., 1995; Xiang et al., 1998). The only other regions that are internalized to this extent are found in D5. These data imply that the stem–loop section of D3 is of primary importance to the function of this domain and that the motif forms particularly intimate contacts with the active site, as suggested by previous studies (Jestin et al., 1997).

Protections involving the interactions of D5. All of the tertiary interactions known to contribute to the formation of the group II intron active site contain nucleotides that are among the most protected in the entire D135 molecule. Components of the ζ–ζ′ interaction between the D5 tetraloop and its cognate receptor in D1 (Costa and Michel, 1995) are protected to very similar extents (Figure 5). Notably, the hydroxyl radical accessibility pattern of this interaction is almost identical to that of the same motif in the group I L-21 ribozyme (Doherty and Doudna, 1997). There are high levels of protection involving nucleotides of the κ–κ′ interaction, which joins a three-way junction in D1 (spanning nt 204–215) with a set of highly conserved tandem G–C pairs in stem 1 of D5 (positions 818,819 and 844,845) (Boudvillain and Pyle, 1998). It is interesting to note that the region of D1 that contains the κ and ζ motifs results in strikingly short regions of alternating protection and accessibility (Figure 4), which seems to indicate a complex arrangement of tertiary structure in this section of the D5–D1 interface.

The third and most recently identified tertiary contact between D1 and D5 is the λ–λ′ interaction (Boudvillain et al., 2000), and once again, these catalytically important residues are highly internalized in the D135 core. This interaction links nt G5 and A115, which are adjacent to the essential ε–ε′ interaction, with a pair of base pairs in stem 2 of D5 (nt 825,826 and 835,836) forming a network of base triple interactions that are among a complex array of RNA structures in the active site involving the D5 bulge (nt 838,839).

The catalytic site of D5 is believed to lie on one face of the domain, spanning a major groove section of stem 1 that includes the almost invariant AGC triad of nt 816–818 (Michel et al., 1989) and the D5 bulge (Konforti et al., 1998a). Nucleotides and even individual atoms along this surface of D5 have been shown to be critical for the chemical step of catalysis (Peebles et al., 1995; Abramovitz et al., 1996; Konforti et al., 1998a). Consistent with this, nucleotides comprising these sections are the most protected of the entire intron. Nucleotides within and downstream of the bulge, in particular, are completely inaccessible, thereby underscoring a potentially direct role for this motif in reaction chemistry.

Although binding of exonic sequences was not observed to alter hydroxyl radical protection patterns in upstream regions of the ribozyme (analyzed using 5′-end-labeled D135 transcripts, see above), it was important to establish whether the binding of exonic sequences would change protection patterns in downstream regions. Footprinting studies conducted on 3′-end-labeled D135 transcripts did not reveal significant (>2-fold) alterations in D5 protection upon formation of the EBS–IBS interactions (data not shown). However, difficulty in detecting additional changes in the D5 protection pattern is not surprising given that D5 is almost completely protected from hydroxyl radicals even in the absence of bound substrate (protection extent of 6–10 times relative to the unfolded control). These findings are interesting in light of a recent report that 5′-exon binding alters the hydroxyl radical/reverse transcription protection patterns on D5 from an intron derived from Pylaiella littoralis (Costa et al., 2000). In that case, however, changes in D5 protection do not appear to exceed 65%, which is below the threshold that is statistically significant in the current study of the ai5γ intron. Although the total extent of D5 protection in that case is not reported, it is possible that D5 is more accessible, and therefore small, but reproducible, changes in hydroxyl radical protection can be observed.

Other sites of internalization. There are a number of protected regions that have not been characterized extensively through other biochemical experiments. The data herein therefore serve to highlight sections of the intron that may have important new functions. For example, the loop between D1 helices d′′ and d′′′ is one of the strongest metal ion binding regions of the intron (Sigel et al., 2000), and it has been shown to interact with both EBS1 and the 3′-splice site in an intron from P.littoralis (Costa et al., 2000). In addition, the five-way junction at the beginning of D1 contains protections that suggest a discreet, well folded architecture. Finally, the bottoms of the D1 and D4 stems are both protected, indicating that there are specific architectural requirements for orienting the individual domains that radiate from the central wheel that typifies group II intron secondary structure.

Model of the group II active site: consistency with footprinting results

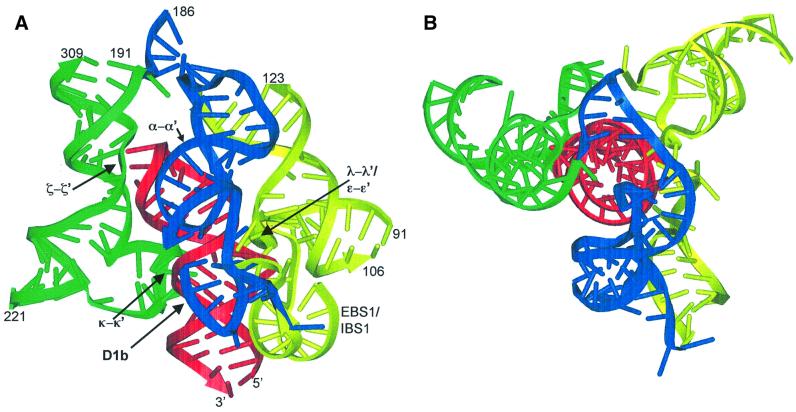

A three-dimensional model of the ai5γ core was constructed from D1 and D5, which are the only substructures required for catalysis by the intron (Koch et al., 1992; Michels and Pyle, 1995). In the first stage of construction, a ‘wire-and-tube’ approach (Brimacombe et al., 1988) was employed to create a model that could be physically manipulated. An ‘in silico’ model of the D1/D5 core was then built in the program ERNA-3D (Mueller and Brimacombe, 1997; Mueller et al., 2000) by incorporating observations from the wire-and-tube approach and satisfying known constraints on ai5γ secondary and tertiary structure. RNA motifs (such as the tetraloop–receptor interactions, kissing hairpins, etc.) were all adapted from the database of RNA crystal structures (see Materials and methods). The resultant model encompasses all of D5 and the following structural elements from D1: helices b, c, d, d′ and d′′, portions of helices d3 and c1, along with the α–α′, ε–ε′ and EBS1–IBS1 long-range interactions. The model also includes the known D1–D5 tertiary interactions λ–λ′, ζ–ζ′ and κ–κ′.

The most notable feature of the model is that D5 (in red) is almost completely surrounded by three major elements of D1 structure (shown in green, blue and yellow), which form a tripod of interactions that enclose D5 (Figure 6). One of these elements (in green) contains the κ–κ′ and ζ–ζ′ interactions (Konforti et al., 1998b; Boudvillain et al., 2000) that are involved in the ground-state binding of D5. On the opposite side of D5, D1 engages a second set of contacts (λ–λ′, ε–ε′ and EBS1–IBS interactions) that participate in reaction chemistry (in yellow) (Abramovitz et al., 1996; Boudvillain and Pyle, 1998; Konforti et al., 1998a; Boudvillain et al., 2000). The placement of these tertiary contacts, and of the 5′-splice site in the catalytic locus of the D5 major groove, constrains the surrounding helices such that the five-way junction at the base of D1 arches over the D5 tetraloop and places the adjacent α–α′ and d3′ helices along a third interface with D5 (blue).

Fig. 6. Three-dimensional model of the minimal ai5γ core. The relative orientation of core D5 and D1 helices is shown. (A) D5 is shown in red, D1 helices that interact with the D5 binding face (including κ–κ′ and ζ–ζ′ interactions) are shown in green, while D1 helices that interact with the D5 chemistry face (including λ–λ′, ε–ε′ and EBS1–IBS1 interactions) are shown in yellow. In blue are helices that bridge these two faces, including α–α′. Greek letters indicate key long-range tertiary interactions. (B) A 90° rotation of the model around the x-axis, looking down from the top of the D5 tetraloop. This figure was generated using WebLab.

Although the model was constructed independently of hydroxyl radical protection studies, there are numerous striking consistencies between the two. In addition to the internalization of D5, the model shows that faces of D1 helices d′, d, c, b, c1, d3′ and EBS1–IBS1 are packed within the inner core. These are regions that all show distinct hydroxyl radical protections. For example, the strongest protections seen in D1 include helix b and the regions surrounding ζ and EBS1. Using the NACCESS program (Hubbard and Thornton, 1993), solvent-inaccessible regions of the model were calculated and compared with the protection data (not shown). Remarkably, there was overlap between almost every inaccessible region in the model and regions identified in the protection studies (within the experimental error of 1–2 nt). There are two exceptions: (i) several nucleotides immediately upstream of EBS1; this is not surprising given that the model, unlike the protection studies, incorporates data where the 5′-exon is in cis; and (ii) a four-nucleotide section of the extended κ region, for which there is otherwise good agreement between calculation and experiment.

It is interesting to compare the model developed here with another recent model of group II intron substructures (Costa et al., 2000). The biochemical and modeling studies described in that work were performed on P.littoralis, rather than ai5γ as reported here. In addition to representing different introns, the P.littoralis and ai5γ models are created from different intron subsections. The P.littoralis model contains the ‘upper half’ of D1, which includes the D1d extension helices and D1b (nt 54–71 and 191–390 in the ai5γ numbering scheme; Figure 5). The model constrains the exon binding sites relative to other intronic substructures in D1 and aligns motifs along the D5 binding face. Conversely, the ai5γ model includes portions of the D1d region, together with the D1c1 and D1b extensions, as well as the first six nucleotides of the intron (approximately nt 1–6, 54–91, 106–125, 186–221, 321–348 and 371–389; Figure 5). This representation allows one to place D5 within a framework of active site and receptor motifs in D1, thereby building a core outward from a central D5 anchor. Another major difference is that the two models reflect different stages in the catalytic process: (i) the P.littoralis model represents a likely conformation after the second step of splicing; and (ii) the ai5γ model is based on constraints that are required either structurally or chemically for the first step of splicing. Given these differences, each model provides unique insight into the architectural organization of group II intron superstructure.

For both introns, D1 helices d, d′ and d′′ can be arranged along the binding face of D5, thereby satisfying the known κ–κ′ and ζ–ζ′ set of long-range interactions. However, it was difficult to arrange other regions of ai5γ in a manner similar to P.littoralis, primarily because of important secondary structural differences between the two introns. One of the most important architectural differences is the length of the D1d3′ helix that connects α′ with EBS1. In the case of P.littoralis, the D1d3′ cognate helix is 9 bp long, which extends the adjacent α–α′ element, and helices D1b and D1c, away from D5. In contrast, the D1d3′ helix in ai5γ contains only 5 bp, resulting in a different length and phasing between EBS1 and the α–α′ helix. This short connection packs helices D1d3′, D1b and α–α′ close to D5, in close proximity to the key active-site nucleotides (including ε and λ; Figure 5) in neighboring D1c1.

A second major structural difference is that the ai5γ model was constructed by including constraints along the ‘chemical face’ of D5, including the λ–λ′ interaction that packs the chemically critical ε–ε′ nucleotides near the D5 bulge (Boudvillain et al., 2000). Furthermore, the 5′-terminus of EBS1 (paired to the cleavage site) is placed against stem 1 of D5, in proximity to the large collection of base and backbone residues that appear to define a catalytic locus in the major groove of D5 stem 1 (Chanfreau and Jacquier, 1994; Peebles et al., 1995; Abramovitz et al., 1996; Boudvillain and Pyle, 1998; Konforti et al., 1998a). In order to satisfy these constraints, particularly given the shortness of the D1d3′ and D1c connecting helices, it was necessary to wrap D1b and α–α′ around a specific side of D5 (blue, Figure 6), creating the tight tripod of interactions that connect tertiary contacts involved in binding (green, Figure 6) and chemistry (yellow, Figure 6). These differences between the P.littoralis and ai5γ models suggest that group II introns may actually have a diversity of architectural form, while pointing the way to directed experiments that will further sharpen our understanding of intron structure.

Conclusions and perspective

Whether group II introns have a tightly packed, solvent-inaccessible ‘core’ has long been the subject of speculation. The fact that these ribozymes can carry out catalysis implicates some form of active site, but catalysis per se does not necessarily require a highly packed superstructure. Although extensive biochemical experimentation has implicated many nucleotides in tertiary interactions, it has been unable to address the relative stability and molecular environment of the catalytic apparatus. The hydroxyl radical footprinting data presented here represent the first direct structural demonstration that group II intron ribozymes have a tightly packed, solvent-inaccessible core like that of other large ribozymes. Furthermore, these data demonstrate that the group II intron ribozymes can form a homogeneous population of molecules with a stable, relatively static structure. This core architecture was visualized by building a model based on a new collection of long-range tertiary interactions. The model, in remarkable agreement with the footprinting data, shows that a specific collection of D1 structural elements pack tightly around D5, enveloping it in a complex network of interactions. Although D5 has long been referred to as the ‘heart of a group II intron’, the extreme solvent inaccessibility of D5 demonstrates that this is a physical reality.

Finally, it is notable that the protection data presented here tell us only about the ribozyme conformation at steady state. The same footprinting method can be applied to learn much more about the molecule. For example, by footprinting the ribozyme as it assumes its active structure, one can learn about its folding pathway (Sclavi et al., 1997); by examining the protection patterns as a function of added urea or Mg2+, one can deconvolute the relative stabilities of individual motifs (Celander and Cech, 1991; Fang et al., 1999; Ralston et al., 2000). In this way, one can apply the powerful experiments developed during study of group I introns and RNase P to examine the unique problem of group II intron folding.

Materials and methods

RNA preparation

Ribozyme D135 was transcribed from plasmid pT7D135, which spans the first nucleotide of the intron to the terminus of the D56 linker. The intron sequences are followed by a polylinker that, when cleaved with HindIII, results in a 35 nt tail that is useful for mapping the downstream sections of the D135 construct. Ribozyme D135 was transcribed as described previously (Qin and Pyle, 1997). The oligonucleotide substrate, comprised of the wild-type 5′-exon–intron boundary (having the sequence 5′-CGUGGUGGGACAUUUUCGAGCGGU-3′), was synthesized as described previously (Michels and Pyle, 1995). RNA samples were prepared in 40 mM MOPS pH 6.0 in the presence of 10 mM EDTA and stored in 10 mM MOPS pH 6.0 and 1 mM EDTA, which reduced non-specific cleavage. Preparation times and temperatures were all reduced and samples were stored at –80°C when not in use.

Active-site titration experiments

For experiments designed to measure the fraction of active ribozyme molecules, substrate oligonucleotide was 5′-end labeled with [γ-32P]ATP and its concentration was determined from the specific activity. Concentrations of unlabeled substrate and ribozyme molecules were determined using a Hewlett-Packard HP 845× UV–visible spectrophotometer. During cleavage reactions, 1 µl of ∼10 nM labeled substrate was combined with 99 µl of 202 nM unlabeled substrate, resulting in a total spiked substrate stock of 200 nM.

Multiple turnover substrate cleavage experiments were performed at 42°C in a total reaction volume of 40 µl, which contained 4 nM D135 and 20 nM oligonucleotide substrate, in a buffer of 80 mM MOPS pH 6.0, 500 mM KCl and 100 mM MgCl2. Several other conditions were tested as well: monovalent and divalent ion concentrations, buffer concentration, pH, temperature and ribozyme denaturation time were all varied to determine the best condition for ensuring complete folding of the ribozyme. An important control was to conduct active-site titrations with a variety of substrate concentrations, ranging from 20 nM to 2 µM, using ratios of substrate to ribozyme that varied from 5 to 10. None of these variations resulted in significant alterations of burst size, burst rate or plateau rate. All reactions were carried out as follows: RNA stock solutions (20 µl each), in 40 mM MOPS and 500 mM KCl, were heated to 95°C for 1 min. After placing these samples at 42°C, 100 mM MgCl2 was added, and the RNA was allowed to fold for 15 min. To initiate the oligonucleotide cleavage reaction, folded D135 and substrate samples were mixed, and at 30 s timepoints, 1 µl aliquots were removed and subjected to PAGE as described previously (Xiang et al., 1998). Product formation was plotted as a function of time, and rate constants for the two phases of reaction, together with their respective amplitudes, were determined from the fit to equation 1:

where P = product, A1 = amplitude of first turnover (burst), k1 = rate of first turnover (burst), A2 = amplitude of subsequent turnovers and k2 = observed rate of subsequent turnovers.

Hydroxyl radical footprinting reactions

D135 was labeled either at the 5′-end with [γ-32P]ATP using T4 polynucleotide kinase (NEB) or at the 3′-end (Huang and Szostak, 1996) using a complementary DNA oligonucleotide and DNA polymerase (NEB). Footprinting reactions were carried out at 42°C with 2–4 nM end-labeled D135 in 80 mM MOPS pH 6.0 and 500 mM KCl in the presence or absence of 100 mM MgCl2 and in a final reaction volume of 10 µl. D135 samples were prepared and folded as described above (with the addition of water instead of MgCl2 to the ‘unfolded’ control). Then 3 µl of 100 mM potassium peroxynitrite (stored in 0.1 M KOH), which had been allowed to pre-heat at 42°C, were added to a final concentration of 30 mM. After mixing, the reaction was allowed to proceed for 5 s. The samples were then placed on ice and precipitated with the addition of sodium acetate to 30 mM, followed by 3 vols of ethanol.

Products of the footprinting reactions were resolved on polyacrylamide or long ranger (FMC Bioproducts) gels of varying concentrations [polyacrylamide, 5–20%; long ranger (BMA Scientific Products), 5–7%], cast on custom-made 36 inch plates. Gels were then analyzed and products quantitated using a Molecular Dynamics Storm 840 PhosphorImager. Quantitation of footprinting was performed using ImageQuant software IQ v1.2 (MacAffe) by measuring the intensity of cleavage for a given set of nucleotides, subtracting the background lane from both ‘folded’ and ‘unfolded’ lanes. The ‘degree of protection’ was assessed by dividing the values from ‘unfolded’ lanes by values from the ‘folded’ lanes.

The active-site titration required a higher pH (7.0) in order to ensure that the chemical rate of hydrolysis was significantly faster than the product release rate. However, most of the footprinting experiments were performed at pH 6.0 in order to reduce background RNA decomposition and the amount of radical generated via peroxynitrite decomposition (Beckman et al., 1990). Nonetheless, when hydroxyl radical footprinting was conducted at pH 7.0, the protection pattern was the same as that at pH 6.0 (Figure 4A), indicating that the lower pH did not significantly alter the structure or its homogeneity.

There is no perceptible change in the solvent accessibility profile of D135 in the presence or absence of KCl (Figure 4B), although addition of 500 mM KCl increases both the cleavage rate and active population size by more than an order of magnitude (S.Leuin, L.J.Su and J.Swisher, unpublished results). This suggests that potassium ions have an effect on some specific aspect of active-site architecture that is not apparent (and is probably internalized) during hydroxyl radical footprinting. Nonetheless, KCl was included in this study to ensure that footprinting was conducted under the conditions known to be optimal for ribozyme function.

Model building

The ‘wire-and-tube’ model was constructed of plastic cylinders and stiff wire for helical and inter-helical portions of the intron, respectively. Long-range tertiary contacts were maintained with Velcro. The computational model, consisting of D5 and portions of D1, was built using the programs ERNA-3D (Mueller and Brimacombe, 1997; available from F.Mueller) and InsightII (MSI). The conformation of D5 was built as described previously (Konforti et al., 1998a). The geometries of helices D1b and α–α′ were taken directly from a kissing hairpin structure [Protein Data Bank (PDB) file 1kis (Chang and Tinoco, 1994)] while the tetraloop–tetraloop receptor interaction ζ–ζ′ was taken directly from the analogous feature in the group I intron [PDB file 1gid (Cate et al., 1996)]. The arrangements of the κ–κ′ interaction, and the coaxial stacking of helices d′′ and d′′′ were modeled after analogous features in hammerhead ribozyme and tRNA structures, respectively [PDB files 1hmh (Pley et al., 1994) and 1tra (Westhof and Sundaralingam, 1986)]. The geometries of the D1 five-way junction and the adjacent three-way junction were modeled based on junction conformations seen in the high-resolution structure of 23S rRNA [PDB file 1ffk (Ban et al., 2000)] and the satisfaction of constraints provided by secondary and tertiary interactions that project from these regions. All other helices were constrained to satisfy type-A helical geometry, and all other elements of known tertiary interaction were constrained to lie in close proximity to each other. Solvent accessibility was determined using the program NACCESS (Hubbard and Thornton, 1993) and a probe with a 5.0 Å radius.

The three-dimensional model can be viewed and manipulated at http://pylelab.org/models

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr Vernon Anderson for his generous provision of potassium peroxynitrite for these experiments and for thoughtful advice concerning its use in RNA footprinting. We are also very grateful to Drs Michael Brenowitz, Mark Chance, Bianca Sclavi and Corey Ralston for numerous helpful discussions during the course of this work, and to Dr Florian Muller for his assistance and for providing the ERNA-3D software. We would like to thank Francois Michel and Maria Costa for suggesting the coaxial stacking of helices d′ and d′′. L.J.S. is supported by the Training Program in Molecular Biophysics, grant # GM08281, and J.S. by ‘Hormones: Biochemistry and Molecular Biology’, grant # DK07328. A.M.P. is an Assistant Investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

References

- Abramovitz D.L., Friedman,R.A. and Pyle,A.M. (1996) Catalytic role of 2′-hydroxyl groups within a group II intron active site. Science, 271, 1410–1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balasubramanian B., Pogozelski,W.K. and Tullius,T.D. (1998) DNA strand breaking by the hydroxyl radical is governed by the accessible surface areas of the hydrogen atoms of the DNA backbone. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 95, 9738–9743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ban N., Nissen,P., Hansen,J., Moore,P.B. and Steitz,T.A. (2000) The complete atomic structure of the large ribosomal subunit at 2.4 Å resolution. Science, 289, 905–920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckman J.S., Beckman,T.W., Chen,J., Marshall,P.A. and Freeman,B. (1990) Apparent hydroxyl radical production by peroxynitrite: implications for endothelial injury from nitric oxide and superoxide. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 87, 1620–1624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boudvillain M. and Pyle,A.M. (1998) Defining functional groups, core structural features and inter-domain tertiary contacts essential for group II intron self-splicing: a NAIM analysis. EMBO J., 17, 7091–7104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boudvillain M., Delencastre,A. and Pyle,A.M. (2000) A new RNA tertiary interaction that links active-site domains of a group II intron and anchors them at the site of catalysis. Nature, 406, 315–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brimacombe R., Atmadja,J., Stiege,W. and Schuler,D. (1988) A detailed model of the three-dimensional structure of Escherichia coli 16S ribosomal RNA in situ in the 30S subunit. J. Mol. Biol., 199, 115–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cate J.H., Gooding,A.R., Podell,E., Zhou,K., Golden,B.L., Kundrot,C.E., Cech,T.R. and Doudna,J.A. (1996) Crystal structure of a group I ribozyme domain reveals principles of higher order RNA folding. Science, 273, 1678–1685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cech T.R. (1988) Conserved sequences and structure of group I introns: building an active site for RNA catalysis—a review. Gene, 73, 259–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celander D.W. and Cech,T.R. (1991) Visualizing the higher order folding of a catalytic RNA molecule. Science, 251, 401–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chanfreau G. and Jacquier,A. (1994) Catalytic site components common to both splicing steps of a group II intron. Science, 266, 1383–1387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chanfreau G. and Jacquier,A. (1996) An RNA conformational change between the two chemical steps of group II self-splicing. EMBO J., 15, 3466–3476. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang K.-Y. and Tinoco,I. (1994) Characterization of a ‘kissing’ hairpin complex derived from the HIV genome. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 91, 8705–8709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaulk S. and MacMillan,A. (2000) Characterization of the Tetrahymena ribozyme folding pathway using the kinetic footprinting reagent peroxynitrous acid. Biochemistry, 39, 2–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chin K. and Pyle,A.M. (1995) Branch-point attack in group II introns is a highly reversible transesterification, providing a possible proof-reading mechanism for 5′-splice site selection. RNA, 1, 391–406. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa M. and Michel,F. (1995) Frequent use of the same tertiary motif by self-folding RNAs. EMBO J., 14, 1276–1285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa M. and Michel,F. (1997) Rules for RNA recognition of GNRA tetraloops deduced by in vitro selection: comparison with in vivo evolution. EMBO J., 16, 3289–3302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa M., Deme,E., Jacquier,A. and Michel,F. (1997a) Multiple tertiary interactions involving domain II of group II self-splicing introns. J. Mol. Biol., 267, 520–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa M., Fontaine,J.M., Goer,S.L. and Michel,F. (1997b) A group II self-splicing intron from the brown alga Pylaiella littoralis is active at unusually low magnesium concentrations and forms populations of molecules with a uniform conformation. J. Mol. Biol., 274, 353–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa M., Michel,F. and Westhof,E. (2000) A three-dimensional perspective on exon binding by a group II self-splicing intron. EMBO J., 19, 5007–5018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cousineau B., Lawrence,S., Smith,D. and Belfort,M. (2000) Retrotransposition of a bacterial group II intron. Nature, 404, 1018–1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon W.J., Hayes,J.J., Levin,J.R., Weidner,M.F., Dombroski,B.A. and Tullius,T.D. (1991) Hydroxyl radical footprinting. Methods Enzymol., 208, 380–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doherty E.A. and Doudna,J.A. (1997) The P4–P6 domain directs higher order folding of the Tetrahymena ribozyme core. Biochemistry, 36, 3159–3169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang X., Pan,T. and Sosnick,T.R. (1999) A thermodynamic framework and cooperativity in the tertiary folding of a Mg2+-dependent ribozyme. Biochemistry, 38, 16840–16846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fersht A. (1985) Enzyme Structure and Mechanism. W.H.Freeman, New York, NY, pp. 155–158.

- Gotte M., Marquet,R., Isel,C., Anderson,V.E., Keith,G., Gross,H.J., Ehresmann,C., Ehresmann,B. and Heumann,H. (1996) Probing the higher order structure of RNA with peroxynitrous acid. FEBS Lett., 390, 226–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin E.A., Qin,Z.-F., Michels,W.A. and Pyle,A.M. (1995) Group II intron ribozymes that cleave DNA and RNA linkages with similar efficiency and lack contacts with substrate 2′-hydroxyl groups. Chem. Biol., 2, 761–770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris-Kerr C.L., Zhang,M. and Peebles,C.L. (1993) The phylogenetically predicted base-pairing interaction between α and α′ is required for group II splicing in vitro. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 90, 10658–10662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Z. and Szostak,J.W. (1996) A simple method for 3′-labeling of RNA. Nucleic Acids Res., 24, 4360–4361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard S.J. and Thornton,J.M. (1993) NACCESS Computer Program. Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, University College London, London, UK.

- Jacquier A. and Michel,F. (1987) Multiple exon-binding sites in class II self-splicing introns. Cell, 50, 17–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacquier A. and Michel,F. (1990) Base-pairing interactions involving the 5′- and 3′-terminal nucleotides of group II self-splicing introns. J. Mol. Biol., 213, 437–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacquier A. and Rosbash,M. (1986) Efficient trans-splicing of a yeast mitochondrial RNA group II intron implicates a strong 5′-exon–intron interaction. Science, 234, 1099–1104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarrell K.A., Dietrich,R.C. and Perlman,P.S. (1988) Group II intron domain 5 facilitates a trans-splicing reaction. Mol. Cell. Biol., 8, 2361–2366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jestin J.-L., Deme,E. and Jacquier,A. (1997) Identification of structural elements critical for inter-domain interactions in a group II self-splicing intron. EMBO J., 16, 2945–2954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch J.L., Boulanger,S.C., Dib-Hajj,S.D., Hebbar,S.K. and Perlman,P.S. (1992) Group II introns deleted for multiple substructures retain self-splicing activity. Mol. Cell. Biol., 12, 1950–1958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konforti B.B., Abramovitz,D.L., Duarte,C.M., Karpeisky,A., Beigelman,L. and Pyle,A.M. (1998a) Ribozyme catalysis from the major groove of group II intron domain 5. Mol. Cell, 1, 433–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konforti B.B., Liu,Q. and Pyle,A.M. (1998b) A map of the binding site for catalytic domain 5 in the core of a group II intron ribozyme. EMBO J., 17, 7195–7217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latham J.A. and Cech,T.R. (1989) Defining the inside and outside of a catalytic RNA molecule. Science, 245, 276–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madhani H.D. and Guthrie,C. (1992) A novel base-pairing interaction between U2 and U6 snRNAs suggests a mechanism for the catalytic activation of the spliceosome. Cell, 71, 803–817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michel F. and Ferat,J.-L. (1995) Structure and activities of group II introns. Annu. Rev. Biochem., 64, 435–461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michel F., Umesono,K. and Ozeki,H. (1989) Comparative and functional anatomy of group II catalytic introns—a review. Gene, 82, 5–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michels W.J. and Pyle,A.M. (1995) Conversion of a group II intron into a new multiple-turnover ribozyme that selectively cleaves oligonucleotides: elucidation of reaction mechanism and structure/function relationships. Biochemistry, 34, 2965–2977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller F. and Brimacombe,R. (1997) A new model for the three-dimensional folding of Escherichia coli 16S ribosomal RNA. I. Fitting the RNA to a 3D electron microscopic map at 20 Å. J. Mol. Biol., 271, 524–544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller F., Sommer,I., Baranov,P., Matadeen,R., Stoldt,M., Wohnert,J., Gorlach,M., van Heel,M. and Brimacombe,R. (2000) The 3D arrangement of the 23S and 5S ribosomal subunit based on a cryo-electron microscopic reproduction at 7.5 Å resolution. J. Mol. Biol., 298, 35–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy F.L. and Cech,T.R. (1993) An independently folding domain of RNA tertiary structure within the Tetrahymena ribozyme. Biochemistry, 32, 5291–5300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolan J.M. and Pace,N.R. (1996) Structural analysis of the bacterial ribonuclease P RNA. Nucleic Acids Mol. Biol., 10, 109–128. [Google Scholar]

- Pan T. (1995) Higher-order folding and domain analysis of the ribozyme from Bacillus subtilis ribonuclease P. Biochemistry, 34, 902–909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peebles C.L., Zhang,M., Perlman,P.S. and Franzen,J.F. (1995) Identification of a catalytically critical trinucleotide in domain 5 of a group II intron. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 92, 4422–4426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perlman P.S., Jarrell,K.A., Dietrich,R.C., Peebles,C.L., Romiti,S.L. and Benatan,E.J. (1986) Mitochondrial gene expression in yeast: further studies of a self-splicing group II intron. In Wickner,R.B., Hinnebusch,A., Lambowitz,A.M., Gunsalus,I.C. and Hollaender,A. (eds), Extrachromasomal Elements in Lower Eukaryotes. Plenum press, New York, NY, pp. 39–55. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Pley H.W., Flaherty,K.M. and McKay,D.B. (1994) Three-dimensional structure of a hammerhead ribozyme. Nature, 372, 68–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Podar M., Dib-Hajj,S. and Perlman,P.S. (1995a) A UV-induced Mg2+-dependent cross-link traps an active form of domain 3 of a self-splicing group II intron. RNA, 1, 828–840. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Podar M., Perlman,P.S. and Padgett,R.A. (1995b) Stereochemical selectivity of group II intron splicing, reverse-splicing and hydrolysis reactions. Mol. Cell. Biol., 15, 4466–4478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Podar M., Zhou,J., Zhang,M., Franzen,J.S., Perlman,P.S. and Peebles,C.L. (1998) Domain 5 binds near a highly-conserved dinucleotide in the joiner linking domains 2 and 3 of a group II intron. RNA, 4, 151–166. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price M.A. and Tullius,T.D. (1993) How the structure of an adenine tract depends on sequence context: a new model for the structure of TnAn DNA sequences. Biochemistry, 32, 127–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pyle A.M. and Green,J.B. (1994) Building a kinetic framework for group II intron ribozyme activity: quantitation of interdomain binding and reaction rate. Biochemistry, 33, 2716–2725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin P.Z.F. and Pyle,A.M. (1997) Stopped-flow fluorescence spectrocopy reveals that domain 1 of a group II intron is an independent folding unit. Biochemistry, 36, 4718–4730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin P.Z. and Pyle,A.M. (1998) The architectural organization and mechanistic function of group II intron structural elements. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol., 8, 301–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ralston C.Y., He,Q., Brenowitz,M. and Chance,M.R. (2000) Stability and cooperativity of individual tertiary contacts in RNA revealed through chemical denaturation. Nature Struct. Biol., 7, 371–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sclavi B., Woodson,S., Sullivan,M., Chance,M. and Brenowitz,M. (1997) Time-resolved synchrotron X-ray ‘footprinting’, a new approach to the study of nucleic acid structure and function: application to protein–DNA interactions and RNA folding. J. Mol. Biol., 266, 144–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shelton V., Sosnick,T. and Pan,T. (1999) Applicability of urea in the thermodynamic analysis of secondary and tertiary RNA folding. Biochemistry, 38, 16831–16839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigel R.K.O., Vaidya,A. and Pyle,A.M. (2000) Metal ion binding sites in a group II intron core. Nature Struct. Biol., 7, 1111–1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sontheimer E.J., Gordon,P.M. and Piccirilli,J.A. (1999) Metal ion catalysis during group II intron self-splicing: parallels with the spliceosome. Genes Dev., 13, 1729–1741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suchy M. and Schmelzer,C. (1991) Restoration of the self-splicing activity of a defective group II intron by a small trans-acting RNA. J. Mol. Biol., 222, 179–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun J.S. and Manley,J.L. (1995) A novel U2–U6 snRNA structure is necessary for splicing. Genes Dev., 9, 843–854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westhof E. and Sundaralingam,M. (1986) Restrained refinement of the monoclinic form of yeast phenylalanine transfer RNA. Temperature factors and dynamics, coordinated waters and base-pair propeller twist angles. Biochemistry, 25, 4868–4878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiang Q., Qin,P.Z., Michels,W.J., Freeland,K. and Pyle,A.M. (1998) The sequence-specificity of a group II intron ribozyme: multiple mechanisms for promoting unusually high discrimination against mismatched targets. Biochemistry, 37, 3839–3849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerly S., Guo,H., Eskes,R., Yang,J., Perlman,P.S. and Lambowitz,A.M. (1995) A group II intron RNA is a catalytic component of a DNA endonuclease involved in intron mobility. Cell, 83, 529–538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]